Volume 8, Issue 3 (Summer 2020)

PCP 2020, 8(3): 175-182 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nikoy Kouhpas E, Karimi Z, Rahmani B, Shoaee F. The Relationship Between Existential Anxiety and Demoralization Syndrome in Predicting Psychological Well-Being of Patient With Cancer. PCP 2020; 8 (3) :175-182

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-517-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-517-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran. ,shoaeef@yahoo.com

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 623 kb]

(1885 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3374 Views)

Full-Text: (1843 Views)

1. Introduction

Cancer as a chronic disease is considered as a stressful life event that its negative effects will have a great impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. According to the World Health Organization (2012), about 7.6 million people worldwide have lost their lives due to cancer in 2008 (Naghiyaee et al., 2014). Chronic diseases, such as cancer are associated with stress and These patients are more susceptible to stress; thus, the negative psychological and physiological effects will be more in them, which causes reduced immune system functions and they will have difficulty to cope effectively with their illness (Ross, Boesen, Dalton & Johansen, 2002; Kahrazei, Danesh & Hyaderzadegan, 2012).

Due to the complications of cancer and its treatment, conventional treatment methods mainly focus on the quantity of life for patients. In recent years, the quality of life of these patients has been widely considered. The quality of life as opposed to quantity of life is the number of years of life associated with satisfaction, happiness, and pleasure (Ghasemi, Kajbaf & Rabiei, 2011). Psychological well-being is one of the important concepts regarding the quality of life and positive psychology approach. This perspective emphasizes the individual's abilities to improve the lives of the individual and awaken their potential latent talents (Souri, Hejazi & Ejei, 2013). In the past decade, Ryff (1989) proposed the pattern of positive mental health or psychological well-being.

The Ryff 's psychological well-being pattern includes 6 factors as follows: 1. Self-acceptance (a positive attitude to yourself and accept your good and bad aspects and positive feelings about the past); 2. A positive relationship with others (having a sense of intimacy in relationships with others and understand the importance of this connection); 3. Autonomy (sense of independence and ability to withstand the social pressure); 4. Environmental mastery (feelings of environmental mastery and controlling exterior activities and taking advantage of opportunities around); 5. Having a purpose in life (having a purpose in life and believe that there is meaning in the past and in their lives); 6. Personal growth (feelings of continuous growth and achieving new experiences (Refahi, Bahmani, Nayeri & Nayeri, 2015).

On the other hand, existential concerns along with awareness about the possible death and the potential threatening danger can be a significant source of neuroticism in people who are struggling with life-threatening diseases (Henoch & Danielson, 2009; Leung & Esplan, 2010). In the meantime, people who suffer from a type of anxiety called "existential anxiety" face disappointment, alienation, emptiness, and meaninglessness (Leung & Esplan, 2010). Pain and irritation in the face of life-threatening diseases are one of the debilitating and cumbersome conditions (Boston, Bruce & Schreiber, 2011). Existential anxiety is higher in patients who are near the end of their lives (Lichtenthal et al., 2009). On the other hand, people with chronic diseases, such as cancer at a time point in their lives may face demoralization syndrome.

The concept of demoralization syndrome was expressed by Frank and he described it via indicators, such as impotence, isolation, and despair (Vehling et al., 2012). This concept provided an essential and profound basis for evaluating the existential distress in cancer patients who are not treated by standard diagnostic approaches (de Figueiredo, 1993). Mental incompetence has been suggested as the clinical characteristic of demoralization syndrome. It also covers the symptoms of depression, such as sadness, anxiety, anger, or a combination of them (Vehling, Oechsle, Koch & Mehnert, 2013). It seems like a situation, in which the person is faced with constant penetrating physical problems that can be the onset of demoralization syndrome (de Figueiredo, 1993). In this regard, Robinson et al. in their research entitled “A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: a decade of research” stated that demoralization syndrome is common (13%-18%) in patients with progressive diseases or cancer and clinically significant (Robinson, Kissane, Brooker & Burney, 2015).

Because of the high prevalence of cancer in recent years, the importance of psychological issues that can affect treatment of the disease of these patients during and after treatment, and also due to the lack of considerable and sufficient studies in this context to indicate the factors that can improve the psychological well-being of their people and acceptance of the disease the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between existential anxiety and demoralization syndrome in predicting psychological well-being of patients with cancer.

2. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional correlational study was done on patients aged 20-40 years with malignant cancer (skin, stomach, and breast cancer) diagnosed from the beginning of 2013 to the end of 2014 referring to the central hospitals of Ardabil for treatment. Three hospitals and 62 subjects were selected based on purposive sampling and 57 cases were willing to cooperate. Finally, after explaining the research (voluntary participation in the study, the confidentiality of the results of the questionnaires) those eligible were asked to respond to the questionnaires.

Cancer as a chronic disease is considered as a stressful life event that its negative effects will have a great impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. According to the World Health Organization (2012), about 7.6 million people worldwide have lost their lives due to cancer in 2008 (Naghiyaee et al., 2014). Chronic diseases, such as cancer are associated with stress and These patients are more susceptible to stress; thus, the negative psychological and physiological effects will be more in them, which causes reduced immune system functions and they will have difficulty to cope effectively with their illness (Ross, Boesen, Dalton & Johansen, 2002; Kahrazei, Danesh & Hyaderzadegan, 2012).

Due to the complications of cancer and its treatment, conventional treatment methods mainly focus on the quantity of life for patients. In recent years, the quality of life of these patients has been widely considered. The quality of life as opposed to quantity of life is the number of years of life associated with satisfaction, happiness, and pleasure (Ghasemi, Kajbaf & Rabiei, 2011). Psychological well-being is one of the important concepts regarding the quality of life and positive psychology approach. This perspective emphasizes the individual's abilities to improve the lives of the individual and awaken their potential latent talents (Souri, Hejazi & Ejei, 2013). In the past decade, Ryff (1989) proposed the pattern of positive mental health or psychological well-being.

The Ryff 's psychological well-being pattern includes 6 factors as follows: 1. Self-acceptance (a positive attitude to yourself and accept your good and bad aspects and positive feelings about the past); 2. A positive relationship with others (having a sense of intimacy in relationships with others and understand the importance of this connection); 3. Autonomy (sense of independence and ability to withstand the social pressure); 4. Environmental mastery (feelings of environmental mastery and controlling exterior activities and taking advantage of opportunities around); 5. Having a purpose in life (having a purpose in life and believe that there is meaning in the past and in their lives); 6. Personal growth (feelings of continuous growth and achieving new experiences (Refahi, Bahmani, Nayeri & Nayeri, 2015).

On the other hand, existential concerns along with awareness about the possible death and the potential threatening danger can be a significant source of neuroticism in people who are struggling with life-threatening diseases (Henoch & Danielson, 2009; Leung & Esplan, 2010). In the meantime, people who suffer from a type of anxiety called "existential anxiety" face disappointment, alienation, emptiness, and meaninglessness (Leung & Esplan, 2010). Pain and irritation in the face of life-threatening diseases are one of the debilitating and cumbersome conditions (Boston, Bruce & Schreiber, 2011). Existential anxiety is higher in patients who are near the end of their lives (Lichtenthal et al., 2009). On the other hand, people with chronic diseases, such as cancer at a time point in their lives may face demoralization syndrome.

The concept of demoralization syndrome was expressed by Frank and he described it via indicators, such as impotence, isolation, and despair (Vehling et al., 2012). This concept provided an essential and profound basis for evaluating the existential distress in cancer patients who are not treated by standard diagnostic approaches (de Figueiredo, 1993). Mental incompetence has been suggested as the clinical characteristic of demoralization syndrome. It also covers the symptoms of depression, such as sadness, anxiety, anger, or a combination of them (Vehling, Oechsle, Koch & Mehnert, 2013). It seems like a situation, in which the person is faced with constant penetrating physical problems that can be the onset of demoralization syndrome (de Figueiredo, 1993). In this regard, Robinson et al. in their research entitled “A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: a decade of research” stated that demoralization syndrome is common (13%-18%) in patients with progressive diseases or cancer and clinically significant (Robinson, Kissane, Brooker & Burney, 2015).

Because of the high prevalence of cancer in recent years, the importance of psychological issues that can affect treatment of the disease of these patients during and after treatment, and also due to the lack of considerable and sufficient studies in this context to indicate the factors that can improve the psychological well-being of their people and acceptance of the disease the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between existential anxiety and demoralization syndrome in predicting psychological well-being of patients with cancer.

2. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional correlational study was done on patients aged 20-40 years with malignant cancer (skin, stomach, and breast cancer) diagnosed from the beginning of 2013 to the end of 2014 referring to the central hospitals of Ardabil for treatment. Three hospitals and 62 subjects were selected based on purposive sampling and 57 cases were willing to cooperate. Finally, after explaining the research (voluntary participation in the study, the confidentiality of the results of the questionnaires) those eligible were asked to respond to the questionnaires.

Research Tools

Demoralization Syndrome scale

In this study, the Demoralization Syndrome with 24 questions to assess demoralization syndrome was used. This tool has five subscales of lack of means (5), boredom (5 questions), disappointment (6 questions), helplessness (4 questions), and feelings of failure (4 questions). Kissane et al. reported reliability of 94% for this scale. Also, the reliability of 0.86 has been reported for the Persian version of this tool by Naghiay et al. using Cronbach's alpha test) (Naghiay, Bahmani, Alimohammadi & Dehkhoda, 2013).

Demoralization Syndrome scale

In this study, the Demoralization Syndrome with 24 questions to assess demoralization syndrome was used. This tool has five subscales of lack of means (5), boredom (5 questions), disappointment (6 questions), helplessness (4 questions), and feelings of failure (4 questions). Kissane et al. reported reliability of 94% for this scale. Also, the reliability of 0.86 has been reported for the Persian version of this tool by Naghiay et al. using Cronbach's alpha test) (Naghiay, Bahmani, Alimohammadi & Dehkhoda, 2013).

The General Well-being Schedule

The General Well-being Schedule (GWB) focuses on one's subjective feelings of psychological well-being and distress. GWB includes positive and negative questions. Each item has a time frame (during the last month). The first 14 questions are scored on a six-point scale representing the intensity or frequency, whereas four remaining questions use a 0-10 rating scale defined by adjectives at each end. Items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, and 4 are scored reversely so that the lower score indicates a higher level of distress.

The test-retest reliability coefficients (after three months) of 0.68 and 0.85 have been reported for the two different groups. Internal consistency coefficients have been reported for the three subscales in the range of 0.72 to 0.88. Three studies have reported the internal consistency coefficients of over 0.9 for GWB (van Dierendonck, 2004).

Existential anxiety questionnaire

The Existential Anxiety Questionnaire (EAQ) is designed to measure existential anxiety and has 29 items and four subscales: 1. Death anxiety; 2. Responsibility; 3. Loneliness, and 4. Meaning. EAQ is scored on a 4-point scale and the score can vary between 29 and 116. Low scores indicate ignoring the existential anxiety and high scores indicate a high level of existential anxiety (Good & Good, 1974).

Statistical analysis

To analyze the collected data, descriptive statistics, like mean and standard deviation, and to evaluate the hypotheses, Pearson correlation test and multiple regression analysis were used.

3. Results

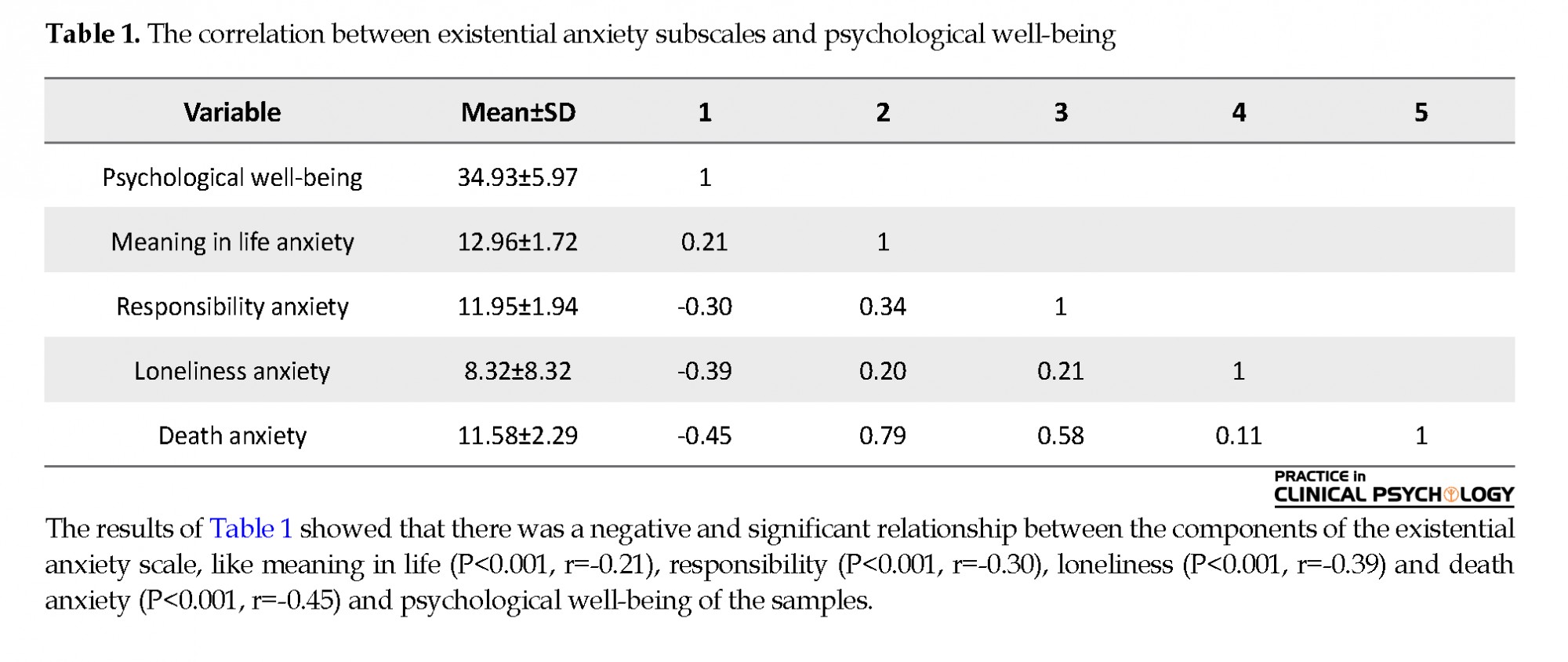

The results of Table 1 showed that there was a negative and significant relationship between the components of the existential anxiety scale, like meaning in life (P<0.001, r=-0.21), responsibility (P<0.001, r=-0.30), loneliness (P<0.001, r=-0.39) and death anxiety (P<0.001, r=- 0.45) and psychological well-being of the samples.

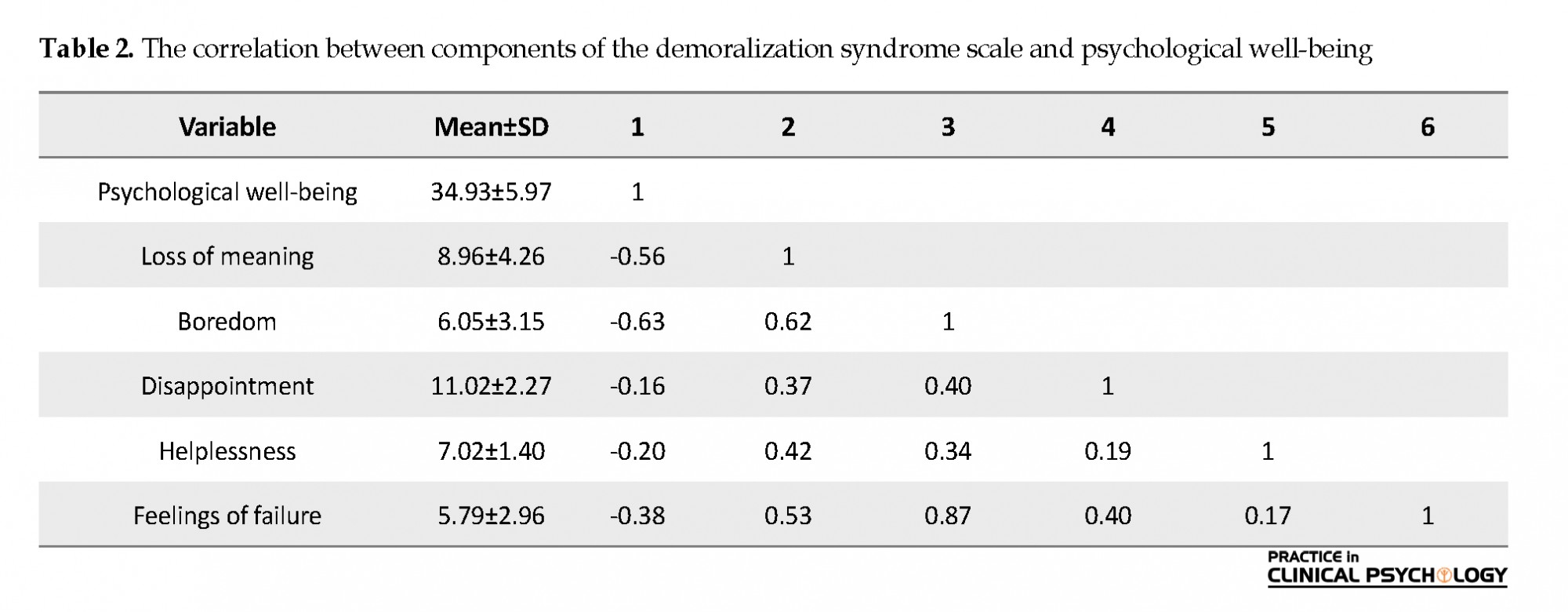

According to the results of Table 2, there was a negative and significant relationship between the components of the demoralization syndrome scale, such as loss of meaning (P<0.001, r=-0.56), boredom (P<0.001, r=-0.63), disappointment (P<0.001, r=-0.16) helplessness (P<0.001, r=-0.20) and feelings of failure (P<0.001, r=-0.45) and psychological well-being of the samples. We also used Stepwise regression to determine the factors that can affect the psychological well-being of patients with cancer. Thus, existential anxiety demoralization syndrome and the spirit of public welfare, as the criterion variable, were the predictors of psychological well-being, respectively.

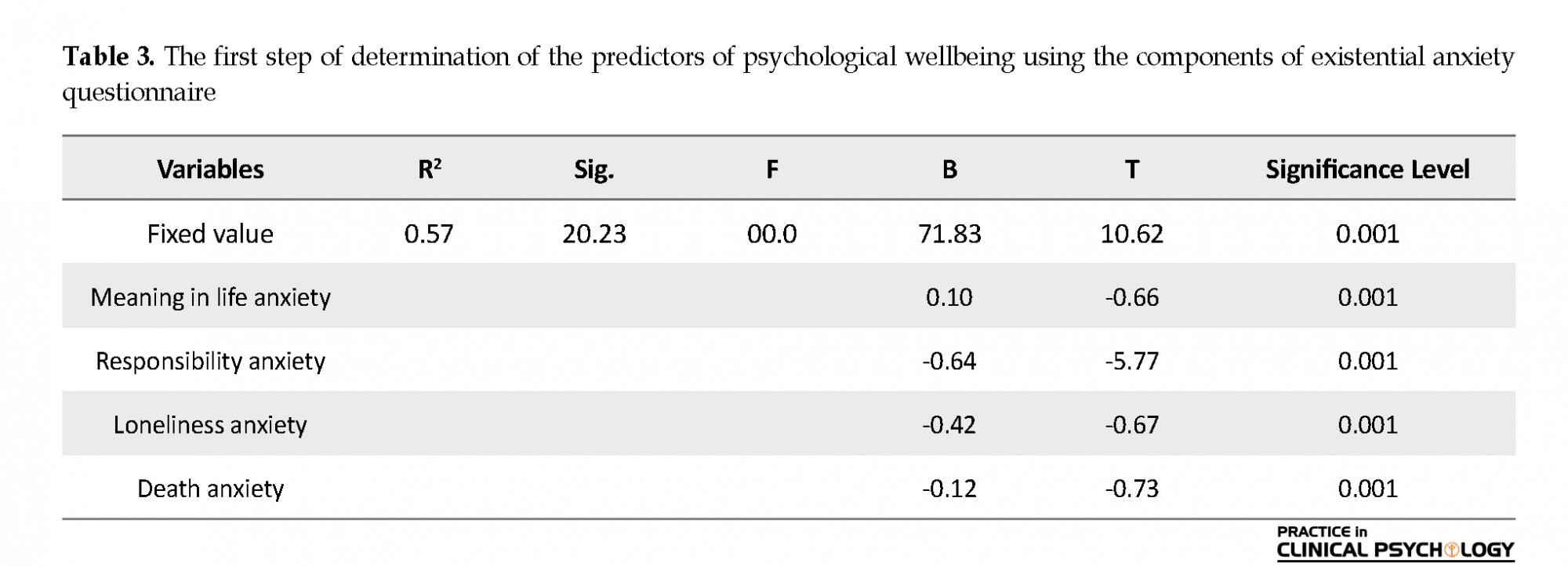

Table 3 shows that about 57% of the total variance of psychological well-being in cancer patients can be explained by existential anxiety. The ANOVA results showed that the regression model was significant (P<0.001, F=23.20) . The results of the regression analysis also showed that the components of existential anxiety, the meaning of life anxiety, responsibility, loneliness anxiety, and death anxiety could predict psychological well-being negatively.

The General Well-being Schedule (GWB) focuses on one's subjective feelings of psychological well-being and distress. GWB includes positive and negative questions. Each item has a time frame (during the last month). The first 14 questions are scored on a six-point scale representing the intensity or frequency, whereas four remaining questions use a 0-10 rating scale defined by adjectives at each end. Items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, and 4 are scored reversely so that the lower score indicates a higher level of distress.

The test-retest reliability coefficients (after three months) of 0.68 and 0.85 have been reported for the two different groups. Internal consistency coefficients have been reported for the three subscales in the range of 0.72 to 0.88. Three studies have reported the internal consistency coefficients of over 0.9 for GWB (van Dierendonck, 2004).

Existential anxiety questionnaire

The Existential Anxiety Questionnaire (EAQ) is designed to measure existential anxiety and has 29 items and four subscales: 1. Death anxiety; 2. Responsibility; 3. Loneliness, and 4. Meaning. EAQ is scored on a 4-point scale and the score can vary between 29 and 116. Low scores indicate ignoring the existential anxiety and high scores indicate a high level of existential anxiety (Good & Good, 1974).

Statistical analysis

To analyze the collected data, descriptive statistics, like mean and standard deviation, and to evaluate the hypotheses, Pearson correlation test and multiple regression analysis were used.

3. Results

The results of Table 1 showed that there was a negative and significant relationship between the components of the existential anxiety scale, like meaning in life (P<0.001, r=-0.21), responsibility (P<0.001, r=-0.30), loneliness (P<0.001, r=-0.39) and death anxiety (P<0.001, r=- 0.45) and psychological well-being of the samples.

According to the results of Table 2, there was a negative and significant relationship between the components of the demoralization syndrome scale, such as loss of meaning (P<0.001, r=-0.56), boredom (P<0.001, r=-0.63), disappointment (P<0.001, r=-0.16) helplessness (P<0.001, r=-0.20) and feelings of failure (P<0.001, r=-0.45) and psychological well-being of the samples. We also used Stepwise regression to determine the factors that can affect the psychological well-being of patients with cancer. Thus, existential anxiety demoralization syndrome and the spirit of public welfare, as the criterion variable, were the predictors of psychological well-being, respectively.

Table 3 shows that about 57% of the total variance of psychological well-being in cancer patients can be explained by existential anxiety. The ANOVA results showed that the regression model was significant (P<0.001, F=23.20) . The results of the regression analysis also showed that the components of existential anxiety, the meaning of life anxiety, responsibility, loneliness anxiety, and death anxiety could predict psychological well-being negatively.

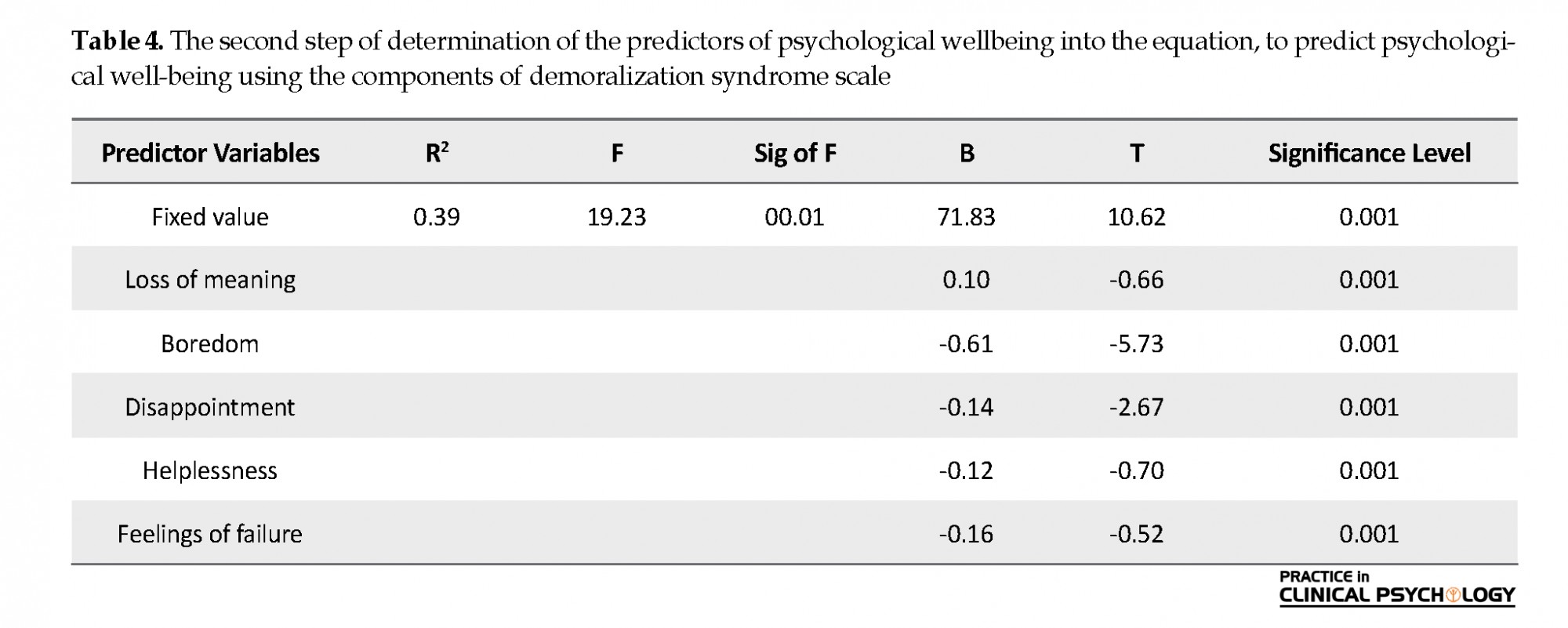

Table 4 indicates that approximately 39% of the variance of the psychological well-being of cancer patients can be explained by the components of demoralization syndrome. The ANOVA results showed that the regression model was statistically significant (P<0.001, r=23.19) . The results of regression analysis also showed that the components of demoralization syndrome, such as loss of meaning, boredom, disappointment, frustration, and feelings of failure could negatively predict psychological well-being.

4. Discussion

This study was done to investigate the relationship between existential anxiety and demoralization syndrome in predicting the psychological well-being of patients with cancer. For this purpose, the research hypotheses were tested using appropriate statistical tests. According to the findings of Table 1, the first hypothesis that there is a significant negative correlation between existential anxiety and psychological well-being among people with cancer was approved. Consistent with our results, Henoch and Danielson (2009) suggested that when people face their own death, suffering, and loss, existential concerns are increased leading to anxiety. Resources of psycho-existential stress in such situations, including the meaning of life, unfair life, a sense of uncertainty over the future can retain the fear of death (Kayser & Scott, 2008).

People who are suffering from chronic diseases, such as cancer may experience loss of their previous responsibilities and roles, as well as the loss of meaning in life. In general, these factors can intensify factors that reduce their health and psychological well-being. People suffering from chronic diseases may no longer be able to do the same responsibilities that they used to do and may even need others' help to do their daily activities. Our results in this area are consistent with previous results (Henoch & Danielson, 2009; Strang, 1997; Mullane, Dooley, Tiernan & Bates, 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Vehling et al., 2012; Lichtenthal et al., 2009; Breitbart, Gibson, Poppito & Berg, 2004; Clarke & Kissane, 2002; Chochinov, 2006).

According to the findings of Table 2, the second research hypothesis stating that there is a negative relationship between the demoralization syndrome and the psychological well-being of patients with cancer was confirmed. This finding is consistent with other reports (Bahmani, Farmani Shahreza, Amin Esmaeili, Naghiay & Ghaedniay Jahromi, 2015; Clarke, Kissane, Trauer & Smith, 2005; Mullane et al., 2009). It has been reported that patients with AIDS, advanced cancers, and chronic diseases had a demoralization syndrome. According to a study by Clarke and Kissane (2002), people who cannot do their daily activities may face disappointment, loss of self-efficacy, and inefficiency in the management and control of the problems.

Furthermore, when assistance is impossible, social withdrawal occurs that is accompanied by a sense of shame and defeat. Those with demoralization syndrome have negative thoughts and are pessimistic about everything and they see everything in black and white. They always humiliate themselves because of their low self-esteem. Although these people are still able to react to their environment, they have no enthusiasm and will lose their motivation or ambition (Sahoo & Mohapatra, 2009). Kissane, Clarke & Street (2001) used the term “existential distress” to describe the people who experience mental distress and are faced with imminent death. They suggested that such an irritation state often is associated with feelings of regret, weakness, absurdity, and feelings about the meaninglessness of life.

They also considered existential themes, such as concern about death, loss of meaning, sadness, loneliness, freedom, and value as the key existential challenges faced by people with life-threatening diseases. They also stated that patients who experience the emotions associated with these themes suffer from demoralization syndrome, as well. In this regard, Bahmani et al. (2015) studied a population of patients with cancer and stated that effective coping psychologically with cancer is a result of cope with the following five factors: 1. Dealing with uncertainty about the future; 2. Finding meaning to what has happened; 3. Facing with a sense of uncontrollability of the future; 4. Openness to disease-related events; and 5. Acceptance of the need for more social and medical support (Bahmani, Motamed Najjar, Sayyah, Shafi-Abadi & Haddad Kashani, 2016). These people cannot easily accomplish these five factors, which highlights the need for more mental health interventions by experts.

5. Conclusion

When a person is diagnosed with cancer, he faces personal and family crises resulting from the disease. He may not be able to maintain sufficient self-efficacy to improve this condition and he may need others to do his many routine tasks. Cancer patients need psychological interventions because of the chronic pain that can cause psychological problems. For cancer patients, caregivers and families are responsible to make a welcoming environment, in which they are able to accept their disease and increase the recovery process.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References:

Bahmani, B., Farmani Shahreza, Sh., Amin Esmaeili, M., Naghiay, M., & Ghaedniay Jahromi, A. (2015). [Demoralization syndrome in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (Persion)]. Journal of Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, 3(1), 19-27. http://journal.nums.ac.ir/article-1-108-en.html

Bahmani, B., Motamed Najjar, M., Sayyah, M., Shafi-Abadi, A., & Haddad Kashani, H. (2016). The effectiveness of cognitive-existential group therapy on increasing hope and decreasing depression in women-treated with haemodialysis. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(6), 219-25. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p219] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boston, P., Bruce, A., & Schreiber, R. (2011). Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 604-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010] [PMID]

Breitbart, W., Gibson, C., Poppito, S. R., & Berg, A. (2004). Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: A focus on meaning and spirituality. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(6), 366-72. [DOI:10.1177/070674370404900605] [PMID]

Chochinov, H. M. (2006). Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 56(2), 84-103. [DOI:10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84] [PMID]

Clarke, D. M., & Kissane, D. W. (2002). Demoralization: Its phenomenology and importance. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 733-42. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01086.x] [PMID]

Clarke, D. M., Kissane, D. W., Trauer, T., & Smith, G. C. (2005). Demoralization, anhedonia and grief in patients with severe physical illness. World Psychiatry, 4(2), 96-105. [PMID] [PMCID]

de Figueiredo, J. M. (1993). Depression and demoralization: Phenomenologic differences and research perspectives. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34(5), 308-11. [DOI:10.1016/0010-440X(93)90016-W]

Ghasemi, N., Kajbaf, M. B., & Rabiei, M. (2011). [The effectiveness of Quality of Life Therapy (QOLT) on Subjective Well-Being (SWB) and mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 3(2), 23-34. [DOI:10.22075/JCP.2017.2051]

Good, L. R., & Good, K. C. (1974). A preliminary measure of existential anxiety. Psychological Reports, 34(1), 72-4. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1974.34.1.72] [PMID]

Henoch, I., & Danielson, E. (2009). Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: An integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology, 18(3), 225-36. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1424] [PMID]

Kahrazei, F., Danesh, E., & Hydarzadegan, A. R. (2012). [The effect of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) on reduction of psychological symptoms among patients with cancer (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 14(2), e93602. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/zjrms/articles/93602.html

Kayser, K., & Scott, J. L. (2008). Helping couples cope with women’s cancers: An evidence-based approach for practitioners. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. https://books.google.com/books?id=1J8o7pQZsN4C&dq

Kissane, D. W., Clarke, D. M., & Street, A. F. (2001). Demoralization syndrome--a relevant psychiatric diagnosis for palliative care. Journal of Palliative Care, 17(1), 12-21. [DOI:10.1177/082585970101700103] [PMID]

Lee, C. Y., Fang, C. K., Yang, Y. C., Liu, C. L., Leu, Y. S., & Wang, T. E., et al. (2012). Demoralization syndrome among cancer outpatients in Taiwan. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(10), 2259-67. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1332-4] [PMID]

Leung, D., & Esplen, M. J. (2010). Alleviating existential distress of cancer patients: Can relational ethics guide clinicians? European Journal of Cancer Care, 19(1), 30-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00969.x] [PMID]

Lichtenthal, W. G., Nilsson, M., Zhang, B., Trice, E. D., Kissane, D. W., & Breitbart, W., et al. (2009). Do rates of mental disorders and existential distress among advanced stage cancer patients increase as death approaches? Psycho-Oncology, 18(1), 50-61. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1371] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mullane, M., Dooley, B., Tiernan, E., & Bates, U. (2009). Validation of the Demoralization Scale in an Irish advanced cancer sample. Palliative & Supportive Care, 7(3), 323-30. [DOI:10.1017/S1478951509990253] [PMID]

Naghiay, M., Bahmani, B., Alimohammadi, F., Dehkhoda, A. (2013). Demoralization in women with breast cancer: A comparative study. Proceedings of the Third National Congress of Psy-chology; 2013 March 18-20; Shiraz: Marvdasht.

Naghiyaee, M., Bahmani, B., Ghanbari Motlagh, A., Khorasani, B., Dehkhoda, A., & Alimohamadi, F. (2014).The effect of rehabilitation method based on existential approach and olson’s model on marital satisfaction. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 12(3), 12-7. http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-362-en.html

Refahi, Z., Bahmani, B., Nayeri, A., & Nayeri, R. (2015). The relationship between attachment to God and identity styles with psychological well-being in married teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1922-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.856]

Robinson, S., Kissane, D. W., Brooker, J., & Burney, S. (2015). A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: A decade of research. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(3), 595-610. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.008] [PMID]

Ross, L., Boesen, E. H., Dalton, S. O., & Johansen, C. (2002). Mind and cancer: Does psychosocial intervention improve survival and psychological well-being? European Journal of Cancer, 38(11), 1447-57. [DOI:10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00126-0]

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35-55. [DOI:10.1177/016502548901200102]

Sahoo, S,. & Mohapatra, P. K. (2009). Demoralization syndrome: A conceptulization. Orissa Journal of Psychiatry, 16(1), 18-20. https://journals.indexcopernicus.com/api/file/viewByFileId/420498.pdf

Souri, H., Hejazi, E., & Ejei, J. (2013). [The correlation of resiliency and optimism with psychological well-being (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7(3), 271-7. http://www.behavsci.ir/article_67839.html

Strang, P. (1997). Existential consequences of unrelieved cancer pain. Palliative Medicine, 11(4), 299-305. [DOI:10.1177/026921639701100406] [PMID]

van Dierendonck, D. (2004). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of psychological well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 629-43. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00122-3]

Vehling, S., Lehmann, C., Oechsle, K., Bokemeyer, C., Krüll, A., & Koch, U., et al. (2012). Is advanced cancer associated with demoralization and lower global meaning? The role of tumor stage and physical problems in explaining existential distress in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 21(1), 54-63. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1866] [PMID]

Vehling, S., Oechsle, K., Koch, U., & Mehnert, A. (2013). Receiving palliative treatment moderates the effect of age and gender on demoralization in patients with cancer. PloS One, 8(3), e59417. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059417] [PMID] [PMCID]

This study was done to investigate the relationship between existential anxiety and demoralization syndrome in predicting the psychological well-being of patients with cancer. For this purpose, the research hypotheses were tested using appropriate statistical tests. According to the findings of Table 1, the first hypothesis that there is a significant negative correlation between existential anxiety and psychological well-being among people with cancer was approved. Consistent with our results, Henoch and Danielson (2009) suggested that when people face their own death, suffering, and loss, existential concerns are increased leading to anxiety. Resources of psycho-existential stress in such situations, including the meaning of life, unfair life, a sense of uncertainty over the future can retain the fear of death (Kayser & Scott, 2008).

People who are suffering from chronic diseases, such as cancer may experience loss of their previous responsibilities and roles, as well as the loss of meaning in life. In general, these factors can intensify factors that reduce their health and psychological well-being. People suffering from chronic diseases may no longer be able to do the same responsibilities that they used to do and may even need others' help to do their daily activities. Our results in this area are consistent with previous results (Henoch & Danielson, 2009; Strang, 1997; Mullane, Dooley, Tiernan & Bates, 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Vehling et al., 2012; Lichtenthal et al., 2009; Breitbart, Gibson, Poppito & Berg, 2004; Clarke & Kissane, 2002; Chochinov, 2006).

According to the findings of Table 2, the second research hypothesis stating that there is a negative relationship between the demoralization syndrome and the psychological well-being of patients with cancer was confirmed. This finding is consistent with other reports (Bahmani, Farmani Shahreza, Amin Esmaeili, Naghiay & Ghaedniay Jahromi, 2015; Clarke, Kissane, Trauer & Smith, 2005; Mullane et al., 2009). It has been reported that patients with AIDS, advanced cancers, and chronic diseases had a demoralization syndrome. According to a study by Clarke and Kissane (2002), people who cannot do their daily activities may face disappointment, loss of self-efficacy, and inefficiency in the management and control of the problems.

Furthermore, when assistance is impossible, social withdrawal occurs that is accompanied by a sense of shame and defeat. Those with demoralization syndrome have negative thoughts and are pessimistic about everything and they see everything in black and white. They always humiliate themselves because of their low self-esteem. Although these people are still able to react to their environment, they have no enthusiasm and will lose their motivation or ambition (Sahoo & Mohapatra, 2009). Kissane, Clarke & Street (2001) used the term “existential distress” to describe the people who experience mental distress and are faced with imminent death. They suggested that such an irritation state often is associated with feelings of regret, weakness, absurdity, and feelings about the meaninglessness of life.

They also considered existential themes, such as concern about death, loss of meaning, sadness, loneliness, freedom, and value as the key existential challenges faced by people with life-threatening diseases. They also stated that patients who experience the emotions associated with these themes suffer from demoralization syndrome, as well. In this regard, Bahmani et al. (2015) studied a population of patients with cancer and stated that effective coping psychologically with cancer is a result of cope with the following five factors: 1. Dealing with uncertainty about the future; 2. Finding meaning to what has happened; 3. Facing with a sense of uncontrollability of the future; 4. Openness to disease-related events; and 5. Acceptance of the need for more social and medical support (Bahmani, Motamed Najjar, Sayyah, Shafi-Abadi & Haddad Kashani, 2016). These people cannot easily accomplish these five factors, which highlights the need for more mental health interventions by experts.

5. Conclusion

When a person is diagnosed with cancer, he faces personal and family crises resulting from the disease. He may not be able to maintain sufficient self-efficacy to improve this condition and he may need others to do his many routine tasks. Cancer patients need psychological interventions because of the chronic pain that can cause psychological problems. For cancer patients, caregivers and families are responsible to make a welcoming environment, in which they are able to accept their disease and increase the recovery process.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References:

Bahmani, B., Farmani Shahreza, Sh., Amin Esmaeili, M., Naghiay, M., & Ghaedniay Jahromi, A. (2015). [Demoralization syndrome in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (Persion)]. Journal of Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, 3(1), 19-27. http://journal.nums.ac.ir/article-1-108-en.html

Bahmani, B., Motamed Najjar, M., Sayyah, M., Shafi-Abadi, A., & Haddad Kashani, H. (2016). The effectiveness of cognitive-existential group therapy on increasing hope and decreasing depression in women-treated with haemodialysis. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(6), 219-25. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p219] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boston, P., Bruce, A., & Schreiber, R. (2011). Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 604-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010] [PMID]

Breitbart, W., Gibson, C., Poppito, S. R., & Berg, A. (2004). Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: A focus on meaning and spirituality. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(6), 366-72. [DOI:10.1177/070674370404900605] [PMID]

Chochinov, H. M. (2006). Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 56(2), 84-103. [DOI:10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84] [PMID]

Clarke, D. M., & Kissane, D. W. (2002). Demoralization: Its phenomenology and importance. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 733-42. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01086.x] [PMID]

Clarke, D. M., Kissane, D. W., Trauer, T., & Smith, G. C. (2005). Demoralization, anhedonia and grief in patients with severe physical illness. World Psychiatry, 4(2), 96-105. [PMID] [PMCID]

de Figueiredo, J. M. (1993). Depression and demoralization: Phenomenologic differences and research perspectives. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34(5), 308-11. [DOI:10.1016/0010-440X(93)90016-W]

Ghasemi, N., Kajbaf, M. B., & Rabiei, M. (2011). [The effectiveness of Quality of Life Therapy (QOLT) on Subjective Well-Being (SWB) and mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 3(2), 23-34. [DOI:10.22075/JCP.2017.2051]

Good, L. R., & Good, K. C. (1974). A preliminary measure of existential anxiety. Psychological Reports, 34(1), 72-4. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1974.34.1.72] [PMID]

Henoch, I., & Danielson, E. (2009). Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: An integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology, 18(3), 225-36. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1424] [PMID]

Kahrazei, F., Danesh, E., & Hydarzadegan, A. R. (2012). [The effect of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) on reduction of psychological symptoms among patients with cancer (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 14(2), e93602. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/zjrms/articles/93602.html

Kayser, K., & Scott, J. L. (2008). Helping couples cope with women’s cancers: An evidence-based approach for practitioners. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. https://books.google.com/books?id=1J8o7pQZsN4C&dq

Kissane, D. W., Clarke, D. M., & Street, A. F. (2001). Demoralization syndrome--a relevant psychiatric diagnosis for palliative care. Journal of Palliative Care, 17(1), 12-21. [DOI:10.1177/082585970101700103] [PMID]

Lee, C. Y., Fang, C. K., Yang, Y. C., Liu, C. L., Leu, Y. S., & Wang, T. E., et al. (2012). Demoralization syndrome among cancer outpatients in Taiwan. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(10), 2259-67. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1332-4] [PMID]

Leung, D., & Esplen, M. J. (2010). Alleviating existential distress of cancer patients: Can relational ethics guide clinicians? European Journal of Cancer Care, 19(1), 30-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00969.x] [PMID]

Lichtenthal, W. G., Nilsson, M., Zhang, B., Trice, E. D., Kissane, D. W., & Breitbart, W., et al. (2009). Do rates of mental disorders and existential distress among advanced stage cancer patients increase as death approaches? Psycho-Oncology, 18(1), 50-61. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1371] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mullane, M., Dooley, B., Tiernan, E., & Bates, U. (2009). Validation of the Demoralization Scale in an Irish advanced cancer sample. Palliative & Supportive Care, 7(3), 323-30. [DOI:10.1017/S1478951509990253] [PMID]

Naghiay, M., Bahmani, B., Alimohammadi, F., Dehkhoda, A. (2013). Demoralization in women with breast cancer: A comparative study. Proceedings of the Third National Congress of Psy-chology; 2013 March 18-20; Shiraz: Marvdasht.

Naghiyaee, M., Bahmani, B., Ghanbari Motlagh, A., Khorasani, B., Dehkhoda, A., & Alimohamadi, F. (2014).The effect of rehabilitation method based on existential approach and olson’s model on marital satisfaction. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 12(3), 12-7. http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-362-en.html

Refahi, Z., Bahmani, B., Nayeri, A., & Nayeri, R. (2015). The relationship between attachment to God and identity styles with psychological well-being in married teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1922-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.856]

Robinson, S., Kissane, D. W., Brooker, J., & Burney, S. (2015). A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: A decade of research. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(3), 595-610. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.008] [PMID]

Ross, L., Boesen, E. H., Dalton, S. O., & Johansen, C. (2002). Mind and cancer: Does psychosocial intervention improve survival and psychological well-being? European Journal of Cancer, 38(11), 1447-57. [DOI:10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00126-0]

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35-55. [DOI:10.1177/016502548901200102]

Sahoo, S,. & Mohapatra, P. K. (2009). Demoralization syndrome: A conceptulization. Orissa Journal of Psychiatry, 16(1), 18-20. https://journals.indexcopernicus.com/api/file/viewByFileId/420498.pdf

Souri, H., Hejazi, E., & Ejei, J. (2013). [The correlation of resiliency and optimism with psychological well-being (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7(3), 271-7. http://www.behavsci.ir/article_67839.html

Strang, P. (1997). Existential consequences of unrelieved cancer pain. Palliative Medicine, 11(4), 299-305. [DOI:10.1177/026921639701100406] [PMID]

van Dierendonck, D. (2004). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of psychological well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 629-43. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00122-3]

Vehling, S., Lehmann, C., Oechsle, K., Bokemeyer, C., Krüll, A., & Koch, U., et al. (2012). Is advanced cancer associated with demoralization and lower global meaning? The role of tumor stage and physical problems in explaining existential distress in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 21(1), 54-63. [DOI:10.1002/pon.1866] [PMID]

Vehling, S., Oechsle, K., Koch, U., & Mehnert, A. (2013). Receiving palliative treatment moderates the effect of age and gender on demoralization in patients with cancer. PloS One, 8(3), e59417. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059417] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Rehabilitation

Received: 2020/01/10 | Accepted: 2020/03/12 | Published: 2020/07/1

Received: 2020/01/10 | Accepted: 2020/03/12 | Published: 2020/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |