Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 21-34 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Pourabbas Z, Amani M, Ebrahimi A M. The Fear of Missing Out and Smartphone Addiction Mediate Interpersonal Sensitivity, Family Environment on Academic Procrastination. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :21-34

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1039-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1039-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,malahat_amani@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,

Keywords: Academic procrastination, Smartphone addiction, Fear of missing out (FoMO), Interpersonal sensitivity, Family environment

Full-Text [PDF 755 kb]

(596 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (877 Views)

Full-Text: (256 Views)

Introduction

Academic procrastination is a prevalent issue among students, impacting approximately 40% to 95% of educational settings (Ozer et al., 2009). Academic procrastination takes many forms, including being late to class or being disorganized, postponing academic tasks, and avoiding tasks (González-Brignardello et al., 2023). Given the widespread use of the internet among young people and adolescents (Aznar-Dı´az et al., 2020), researchers have recently focused on the impact of using smartphones, social networks, and online games on academic performance and academic procrastination (Türel & Dokumaci, 2022).

Excessive internet use can cause psychological and physical problems, impairing academic, occupational, and social functioning (Jia et al., 2017; Evren et al., 2019). Internet addiction is a pathological condition that disrupts behavior and cognitive functioning (Sadock, 2015). Prolonged online activity, including social media and video consumption, often leads to neglect of responsibilities, promoting procrastination (Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020). Research across various countries consistently links excessive internet use with increased academic procrastination (Geng et al., 2018; Rozgonjuk & Kattago, 2018; Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020; Imani & Zakeri, 2023).

Social media effectively satisfies individuals’ need for social connection and curiosity by offering continuous access to information, services, and interpersonal interactions. Features such as notifications, likes, and friend requests serve as social rewards that activate the brain’s reward system, fostering habitual, often unconscious, engagement (Meshi et al., 2015; Shapka, 2019). The tendency to present idealized self-images online encourages social comparison, contributing to increased anxiety, loneliness, depression, fear of rejection, academic difficulties, and diminished well-being (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). Exposure to peers’ curated content frequently triggers fear of missing out (FoMO), further reinforcing these negative effects (Milyavskaya et al., 2018). FoMO is a pervasive fear that others may have valuable experiences in one’s absence” (Gupta et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013). FoMO is a pervasive feeling associated with mental and emotional stress. Such stresses arise from the compulsive worry that one will miss out on a beneficial social experience, which is often observed on social media networks (Alabri, 2022). It is a common cross-cultural phenomenon, experienced by 60% of people (Zhang et al., 2021). FoMO and social comparison are significant predictors of social media addiction among youth (Parveiz et al., 2023). According to the compensatory internet use theory, individuals may turn to social media to cope with negative emotions such as FoMO. Yet, this behavior can create a self-reinforcing cycle in which FoMO both drives and is intensified by social media use (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Among students, the need for belonging has been identified as the strongest predictor of FoMO, both directly and indirectly through increased social media engagement, with women exhibiting higher levels of both (Alabri, 2022). FoMO has also been found to correlate positively with academic procrastination and internet addiction (Manap et al., 2023).

The school, family, peers, and social environment can influence adolescents’ use of the internet (Chaudhury & Tripathy, 2018). In particular, many studies point to the essential role of the family in smartphone addiction (Lam, 2020). Research evidence shows a relationship between family functioning and smartphone addiction (Zhong et al., 2011; Bleakley et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2017). The present study hypothesizes that family relationships influence smartphone addiction and FoMO. Family environment patterns provide information about each person’s perception of their family, including the perception of the socio-family atmosphere resulting from relationships, personal growth, organization, and control of the family system (Vianna et al., 2007). It includes the components of family cohesion (the emotional connection and bond of family members towards each other), emotional expressiveness (the emotional atmosphere and emotional expressive behaviors of family members), and conflict (the degree of free expression of anger, aggression, and conflict between family members) (Moos & Moos, 1994). Poor family functioning may lead to feelings of loneliness, increase the search for emotional support online, and ultimately lead to smartphone addiction (Shi et al., 2017; Lian et al., 2021; Pooragha Roodbarde et al., 2022). In a study of Taiwanese adolescents, Chen et al. (2020) found that male adolescents who had high financial support and a poor family atmosphere, and whose parents did not impose restrictions on internet use, were more susceptible to internet addiction. Studies indicate that a strong parent-adolescent relationship serves as a crucial protective factor, leading to fewer negative behaviors in adolescents. (Pace et al., 2014). In another study, Tsitsika et al. (2011) compared adolescents with internet addiction with normal adolescents. They found that a group of adolescents with internet addiction had significantly more dysfunctional family relationships and parental divorce. They also had poorer academic performance and the highest number of unexcused absences from school. In their systematic review, Kilinc and Yildiz (2019) identified that poor family relationships during adolescence play a significant role in the development of internet addiction. Conversely, the family environment is crucial for fostering self-esteem. Studies suggest that well-functioning families can boost self-esteem and lower the risk of smartphone addiction (Su et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). Hawi and Samaha (2017) observed that students addicted to smartphones tended to experience higher anxiety levels, and those with elevated anxiety often faced serious family relationship issues. Moreover, path analysis indicated that anxiety mediates the positive association between smartphone addiction and problematic family dynamics.

Regarding the relationship between family environment and FoMO, Chen and Chen (2022) found that family functioning directly affects FoMO and indirectly through addiction to social media and self-control. Residing in a dysfunctional family environment can lead individuals to feel isolated and excluded, prompting them to seek attention and approval from others while becoming more attuned to others’ feelings and situations (Chen & Chen, 2022). Research has also demonstrated that positive parent-child communication is linked to lower levels of FoMO (Alt & Boniel-Nissim, 2018). An adolescent’s family background is associated with the level of FoMO (Bloeman & De Coninck, 2020). Regarding the direct effect of family relationships on academic procrastination, Uzun et al. (2022), Heidariezadeh et al. (2022), and Hamidipour and Ezadian (2023) found that the emotional climate of the family was related to academic procrastination of students. In another study, Erzen and Çikrıkci (2018) found a significant relationship between academic procrastination and the level of social support perceived from family. In a warm and supportive family environment, positive interactions are established, and in such circumstances, children feel secure and, as a result, show greater commitment to their academic duties (Uzun et al., 2022).

Personality variables can also play a role in smartphone addiction and FoMO. Interpersonal sensitivity is a personality trait characterized by an extreme awareness of others’ behavior and feelings. In other words, interpersonal sensitivity refers to the degree to which individuals pay attention to the feelings, thoughts, and behavior of others about themselves. Individuals with these traits have been described as being excessively preoccupied with interpersonal relationships, vigilance, and sensitivity to aspects of interpersonal interactions. Individuals with interpersonal sensitivity tend to change their behavior to the expectations of others to minimize the risk of criticism and rejection (Boyce & Parker, 1989). The results of studies showed that internet addiction is positively correlated with interpersonal sensitivity (Basharpoor et al., 2010; Tahmasebi et al., 2021; Suzuki et al., 2023). Dai et al. (2023), You et al. (2019), and Jadidi and Sharifi (2018) found that adolescents with high internet and smartphone addiction had high scores in interpersonal sensitivity. Yılmaz and Bekaroğlu (2020) found in a study that by controlling for the effects of anxiety, depression, phobia, and obsession, the interpersonal sensitivity variable predicted smartphone addiction. The results of other studies show that maladjustment, isolation, alienation, and lack of communication skills, along with rejection, are associated with using social networks in adolescence (Rudolph et al., 2016; Prinstein & Giletta, 2020; Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Feelings of loneliness and the gain of a sense of belonging through group acceptance in adolescents (Oosterhoff et al., 2020) and the need for intimacy with peers may cause them to turn to smartphones (Yao & Zhong, 2014). To temporarily find a sense of belonging, intimacy, and participation through communication on social networks. Lin et al.’s (2021) study shows that interpersonal sensitivity is related positively to FoMO and smartphone addiction. Also, FoMO mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and mobile phone addiction. Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity may avoid situations where they are exposed to judgment from others, such as completing and submitting assignments, due to fear of negative evaluation. As a result, these individuals may procrastinate on homework or avoid starting academic activities to escape this anxiety (Shi et al., 2024).

Although academic procrastination has been widely studied across different student groups, limited research has explored how family environment and interpersonal sensitivity influence procrastination. Moreover, no prior study has investigated the mediating effects of FoMO and smartphone addiction on these relationships. To address this gap, the current study aims to examine the associations between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination, focusing on the mediating roles of FoMO and smartphone addiction among adolescent females.

Materials and Methods

The method of the present study is descriptive-correlational, of the structural equation (SEM) type. The statistical population comprised female students in the 10th to 12th grade living in Mashhad City, a northeastern province of Iran. According to the Cochran formula for populations over 3000 people, the sample size is estimated to be 386 people. To increase the power of the test, 400 people were considered as the sample. Participants were selected by a multi-stage cluster method. For this purpose, the city of Mashhad was clustered according to the number of education districts (7 districts). In the next stage, 5 high schools were randomly selected from each district, and one class was chosen from each school in each grade (10th, 11th, and 12th). After removing incomplete questionnaires, the sample size reached 384. Participants were distributed as follows: 10th grade, 33.85% (130 people); 11th grade, 38.28% (147 people); and 12th grade, 27.87% (107 people).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were having a smartphone, using it, and being willing to complete the questionnaires. The exclusion criteria were the participant’s questionnaire being corrupted and the participant’s absence from class during data collection.

Study instruments

Short form of family environment scale: Moos and Moos (1994) developed the long form of this scale with 27 items, and later a 16-item version was created. It includes subscales of cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict. The overall internal reliability was reported to be 0.88, and the subscales ranged from 0.65 to 0.83. The Cronbach α of the Persian version for the entire questionnaire was 0.81, and the subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.78. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good fit (0.96) (Kiani Chelmardi et al., 2018).

Interpersonal sensitivity measure (IPSM): Boyce and Parker (1989) generated a 36-item IPSM to measure traits of interpersonal sensitivity such as interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and fragile inner self. Answering the questions is based on a 4-point Likert scale. The Cronbach α for the entire scale was 0.86, and the subscales ranged from 0.55 to 0.76, and the test re-test reliability was 0.7. Also, the correlation between clinical judgment on interpersonal sensitivity and the score of the interpersonal sensitivity questionnaire was reported to be 0.72 (Boyce & Parker, 1989). In Iran, it was reported that Cronbach α for the subscales was in the range of 0.7 to 0.51, and the total scale was reported to be 0.86 (Mohammadian et al., 2017).

Academic procrastination questionnaire: Sevari (2011) designed this self-report questionnaire for the Persian language to measure academic procrastination. This questionnaire has 12 items and 3 components, including deliberate procrastination, procrastination due to physical and mental fatigue, and procrastination due to lack of planning. It was reported that the reliability of Cronbach α for the entire questionnaire was 0.85, deliberate procrastination was 0.77, procrastination due to physical and mental fatigue was 0.6, and procrastination due to lack of planning was 0.7. The correlation of this questionnaire with the Tuckman procrastination scale (1991) was 0.35.

Mobile phone addiction questionnaire: Sevari (2014) developed this scale to measure Iranian students’ dependence on mobile phones. This questionnaire has 13 items and subscales of de-creativity, tendency, and loneliness. The questions are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The Cronbach α of the questionnaire was reported to be 0.85, and the results of confirmatory factor analysis indicate a good fit (Sevari, 2014).

Persian version of the FoMO scale: The original version of the FoMO scale was designed by Przybylski et al. (2013) with 10 items that were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The designers of the questionnaire reported that the internal consistency was between 0.87 and 0.9. This questionnaire has been redeveloped and standardized for adolescents in Iran. The Persian version consists of 18 items and subscales of loss, compulsion, and comparison. Its reliability was reported to be 0.95, and its goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis was reported to be 0.62 (Asadi & Sharifi, 2022).

Results

Demographic findings showed that the age range of the participants was 15 to 19 years, with a mean of 16.86 and a standard deviation of 0.85.

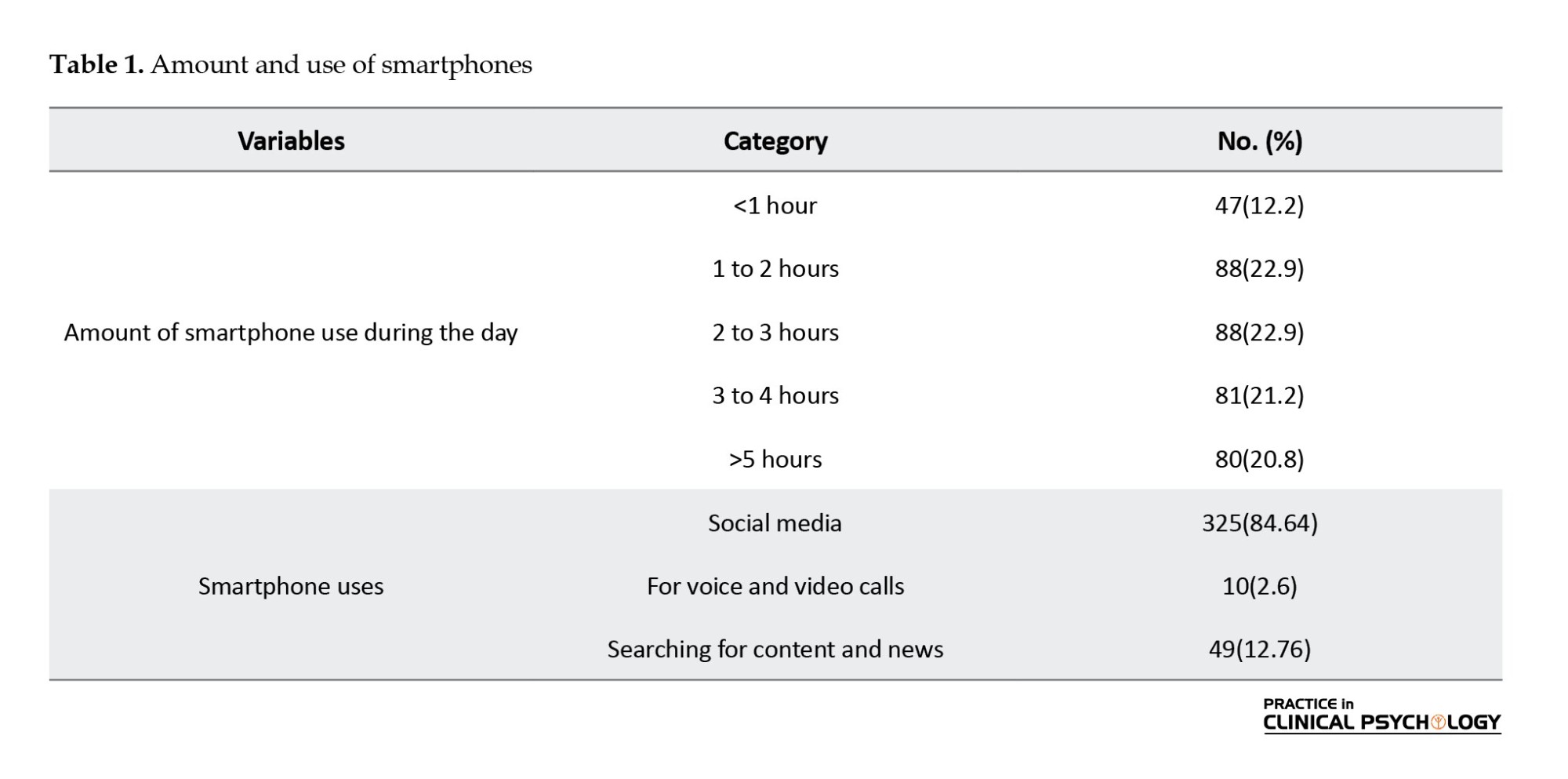

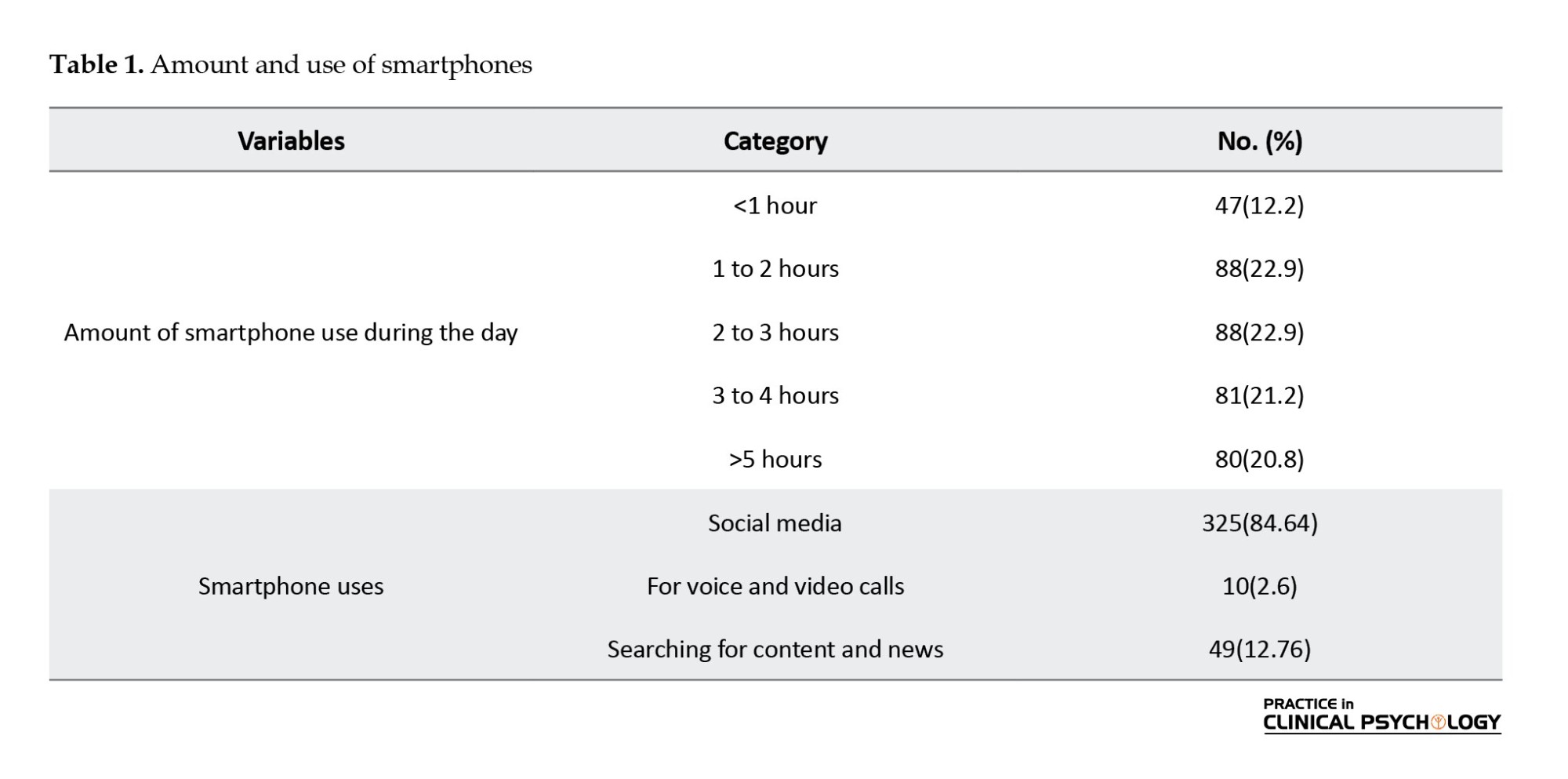

Table 1 shows the amount and types of smartphone usage, with most participants using their smartphones for one to three hours a day, primarily for social media.

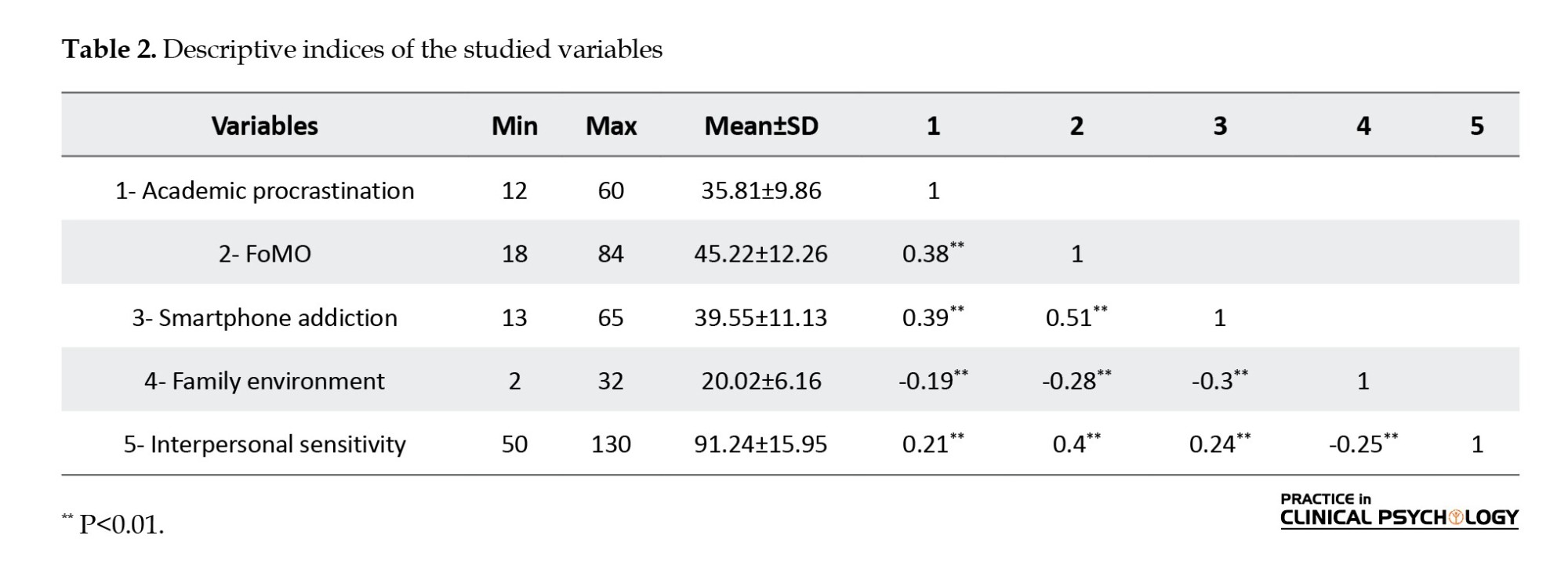

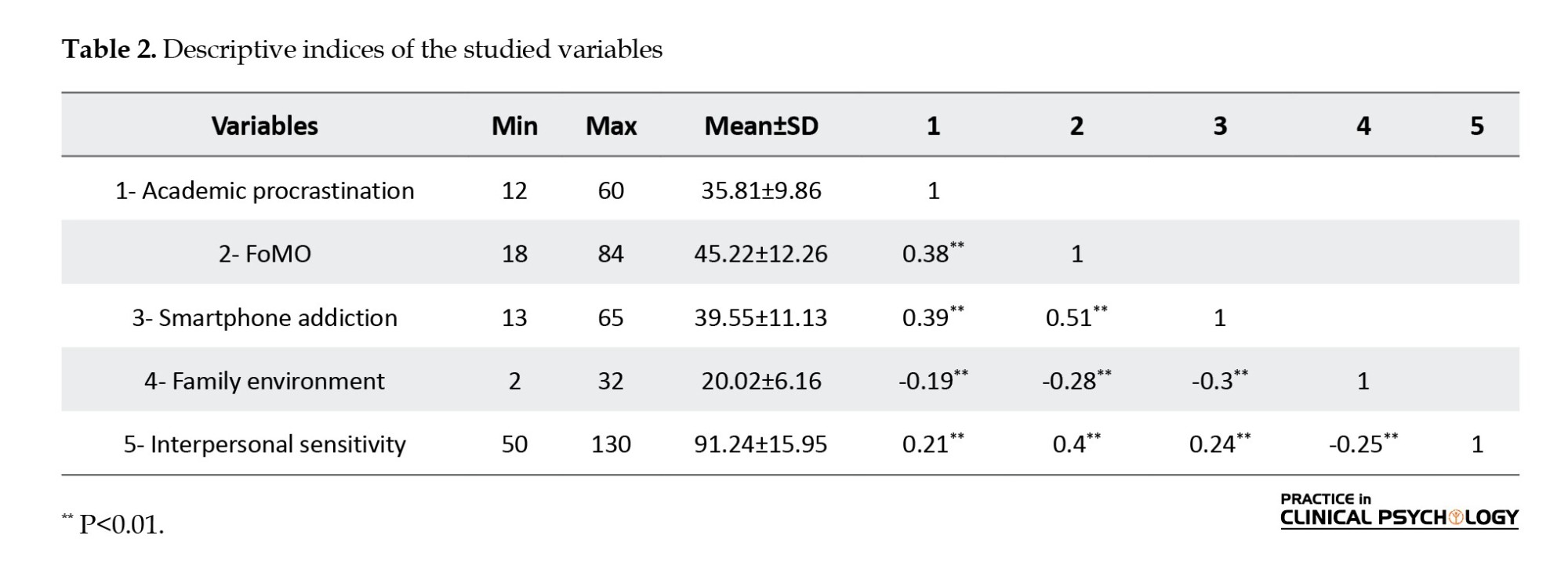

Table 2 presents the minimum and maximum values, Mean±SD, and correlations among the variables. Findings indicate that overall family environment scores are significantly negatively correlated with academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. Additionally, significant positive correlations were found among academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. Structural equation modeling was employed to examine the mediating effects of smartphone addiction and FoMO on the relationships between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination.

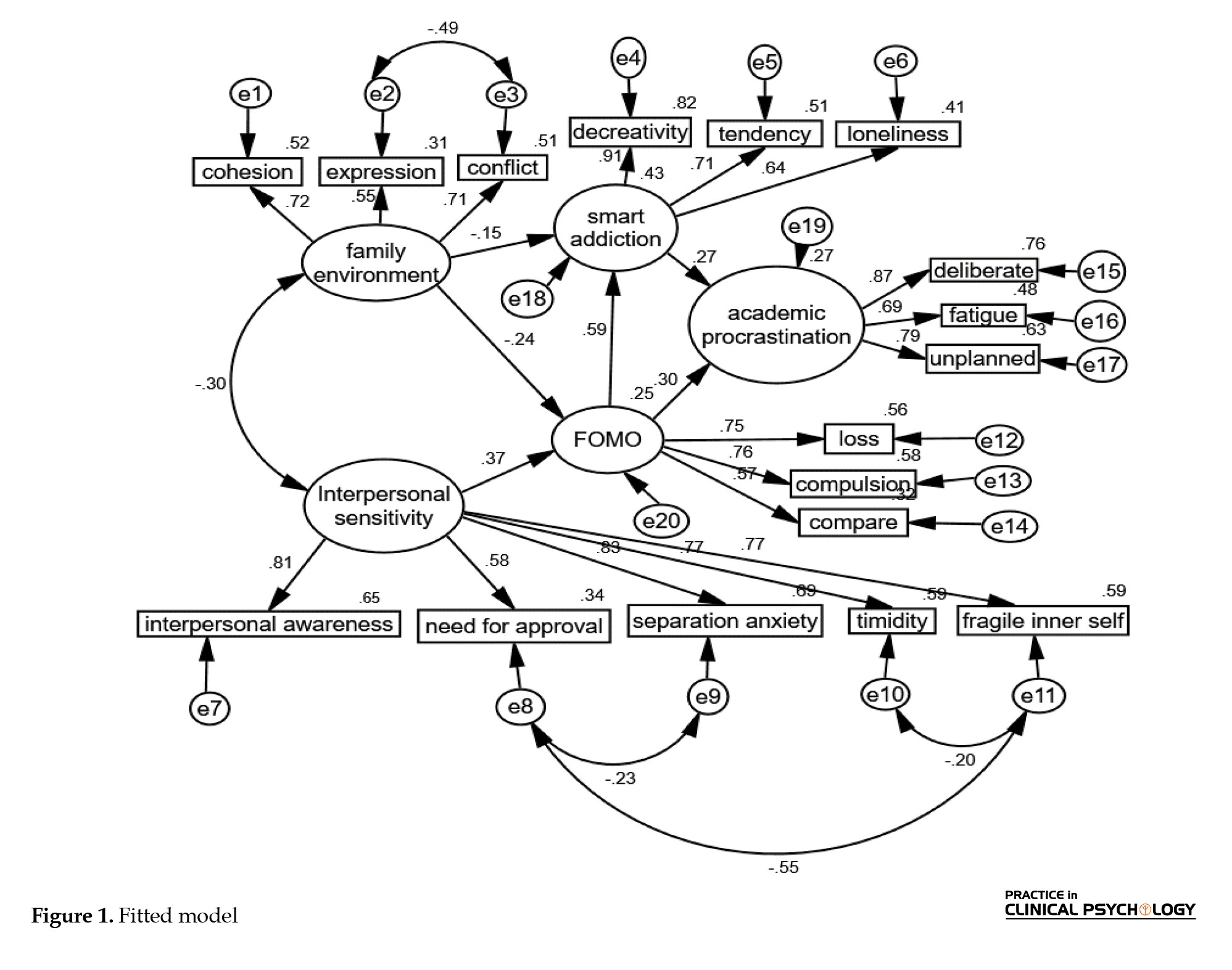

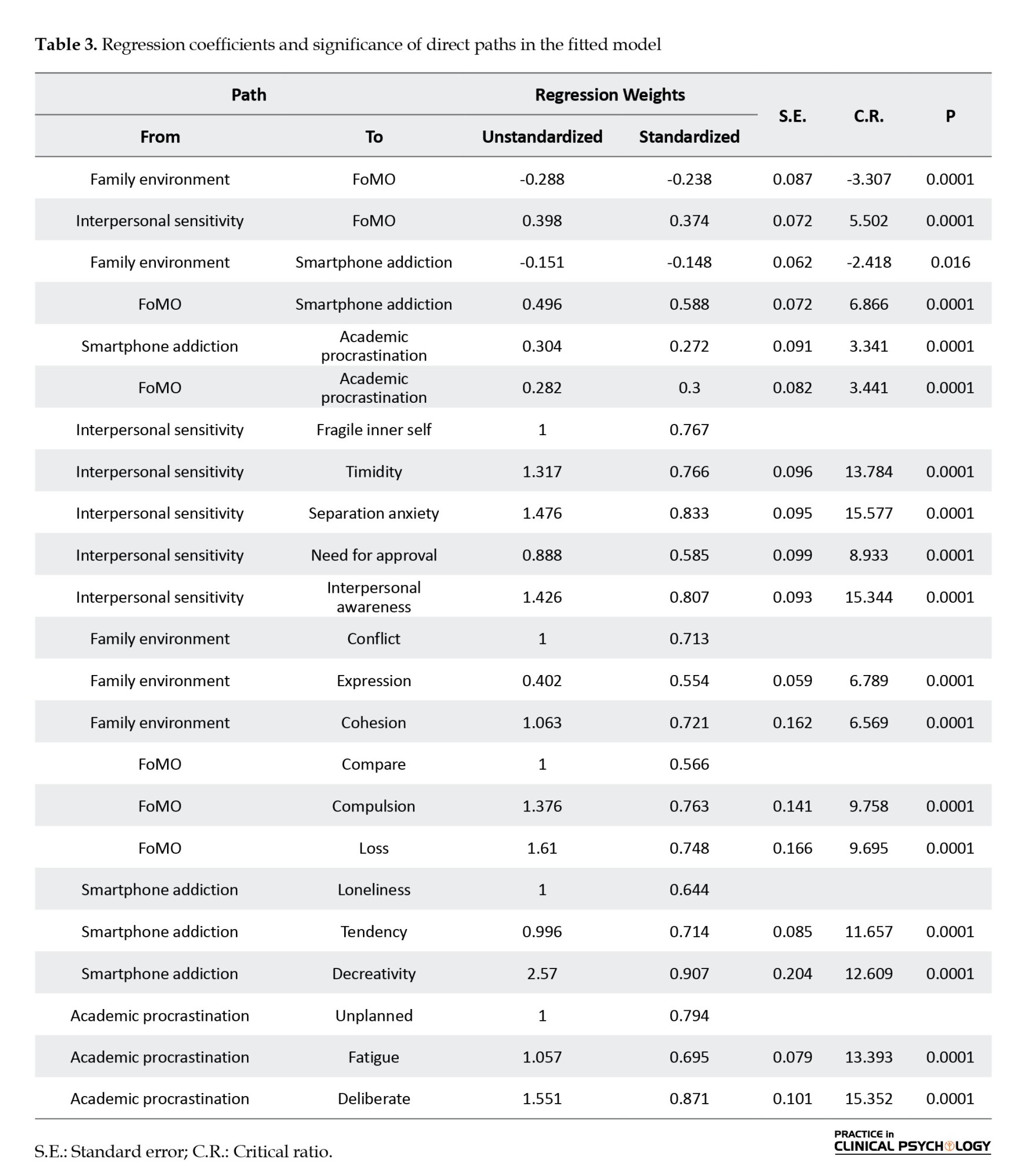

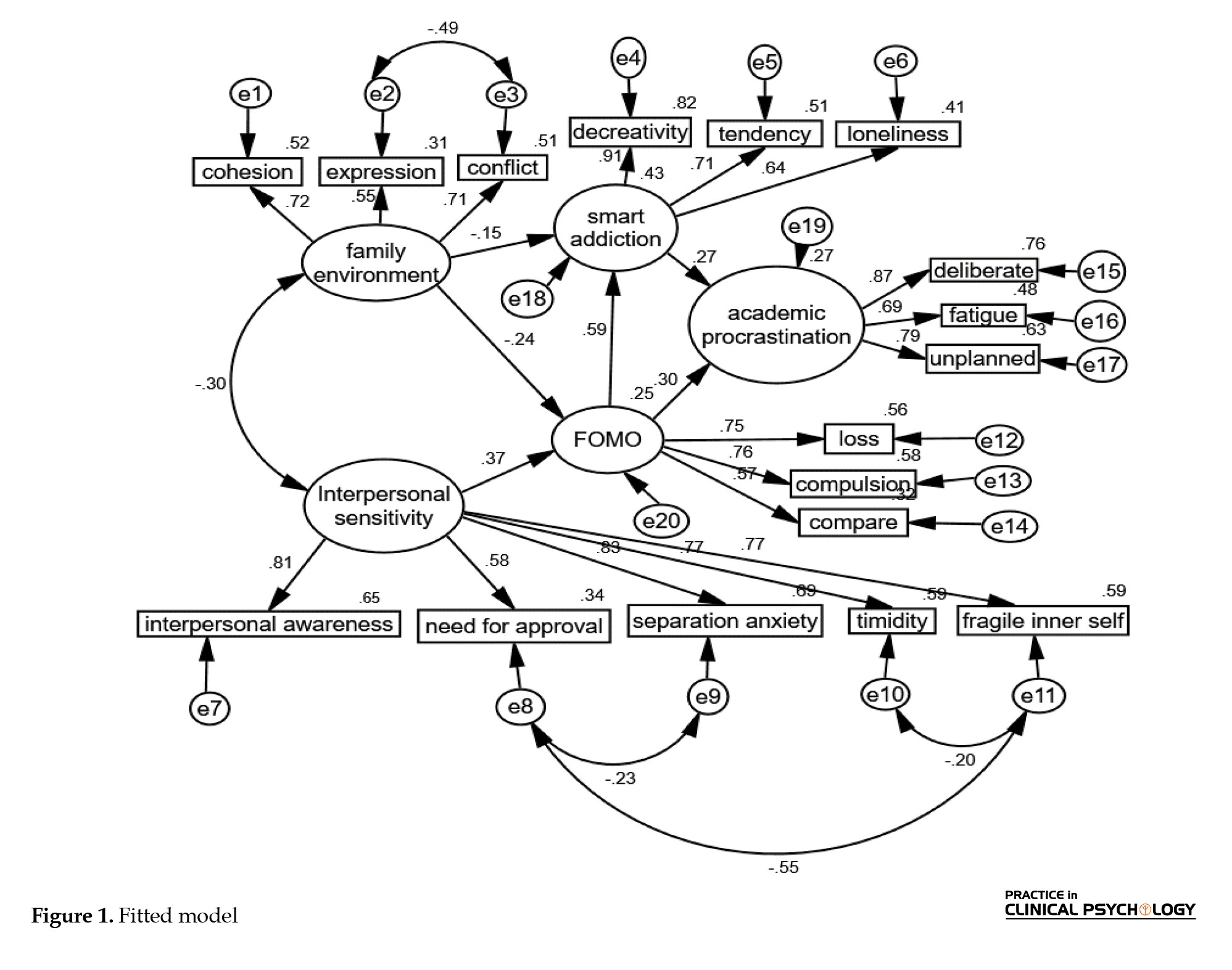

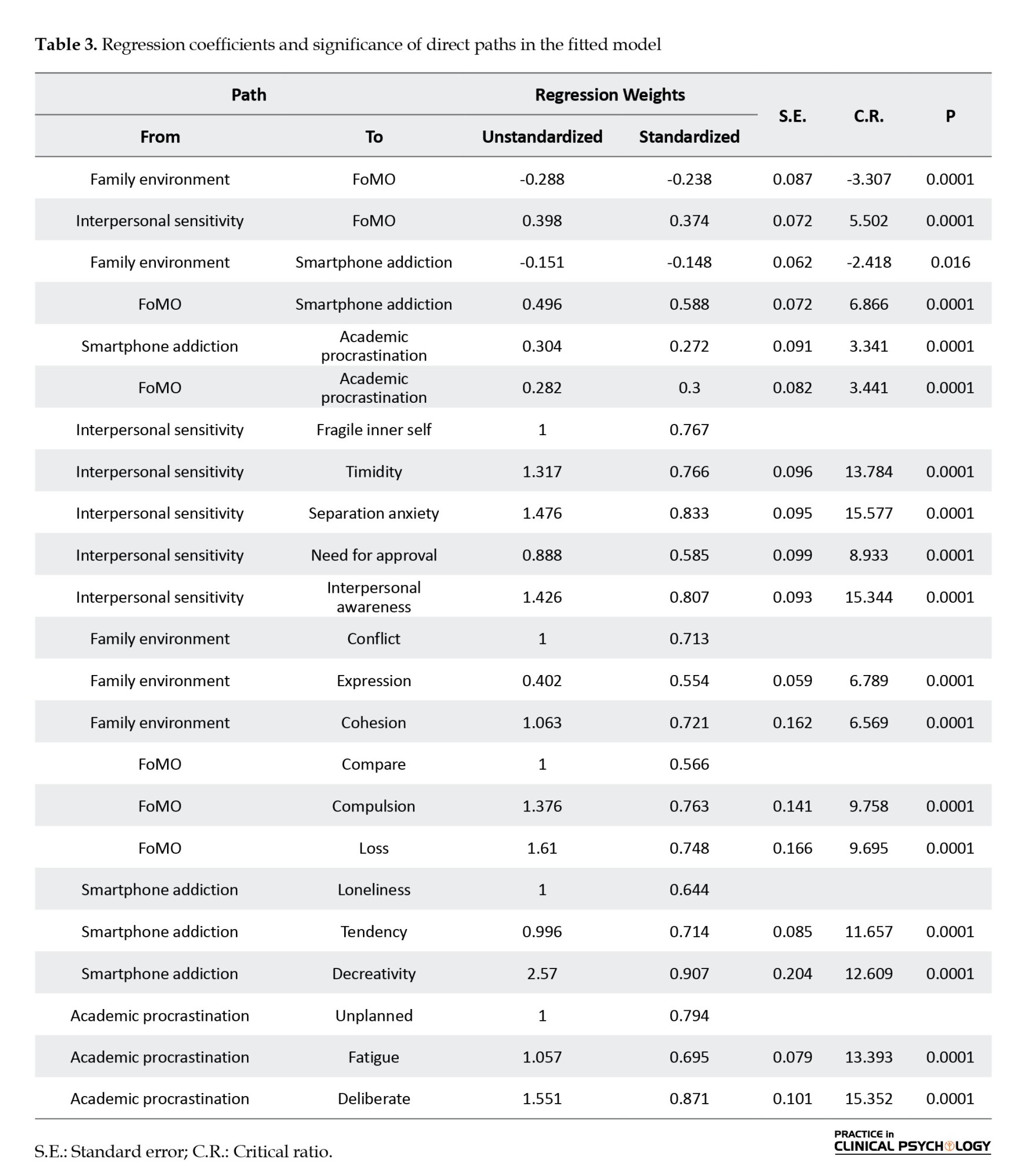

In the initial model, direct paths were drawn from interpersonal sensitivity and family environment to academic procrastination, which were removed in the revised model due to their non-significance. Also, the direct path from interpersonal sensitivity to smartphone addiction was removed due to the non-significance of the effect. The proposed model was fitted as shown in Figure 1, and the results of the direct paths are given in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the effects of the paths of family environment to FoMO (-0.288), family environment to smartphone addiction (-0.151), interpersonal sensitivity to FoMO (0.398), smartphone addiction to academic procrastination (0.304), FoMO to smartphone addiction (0.496), and FoMO to academic procrastination (0.282) are statistically significant. The results also show that the amount of explained variance (r2) for the smartphone addiction variable is 0.429, FoMO is 0.251, and academic procrastination is 0.269.

Model fit was acceptable, chi-square to the degrees of freedom (χ²/df )=2.02, goodness-of-fit index (GFI)=0.94, incremental goodness-of-fit index (IFI)=0.96, normalized fit index (NFI)=0.92, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.96, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)=0.94, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.052, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)=0.057 all meeting conventional thresholds for good fit (e.g. χ²/df <3, GFI/CFI/IFI/TLI ≥0.9, RMSEA ≤0.08, and SRMR ≤0.08) (Kline, 2016).

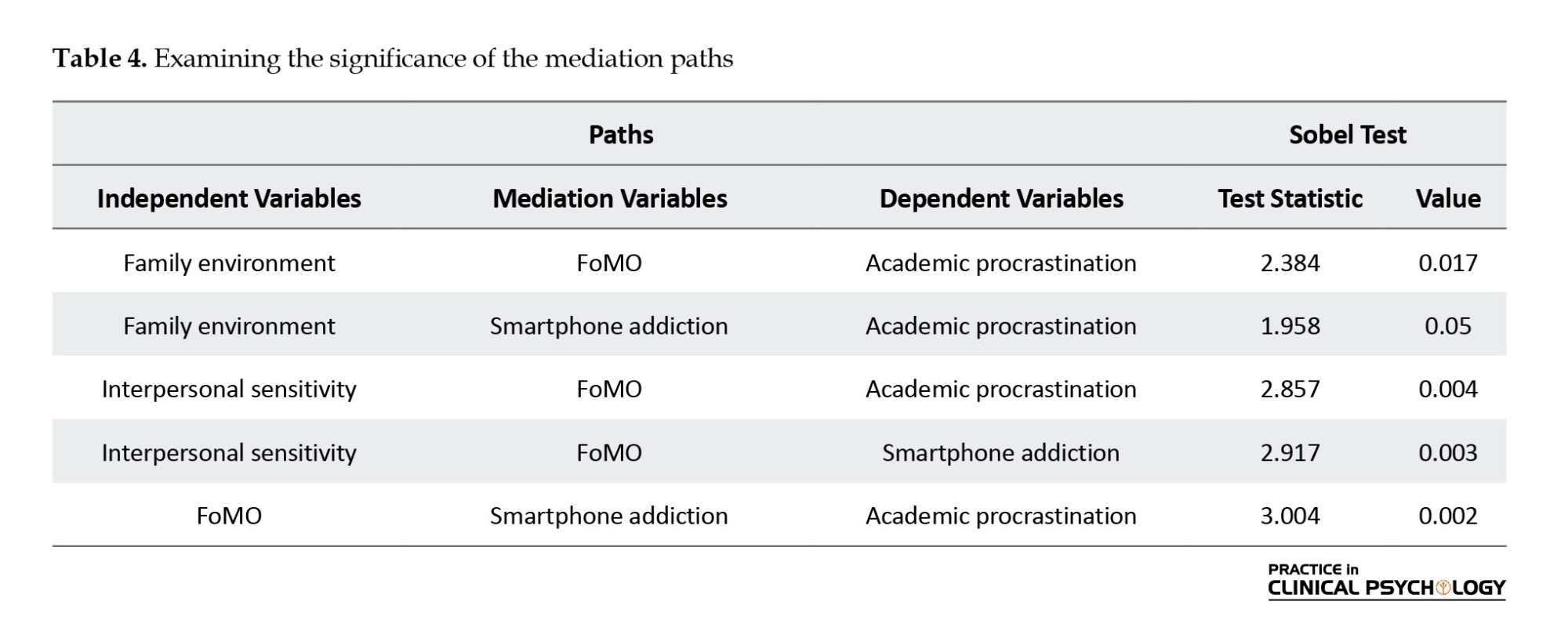

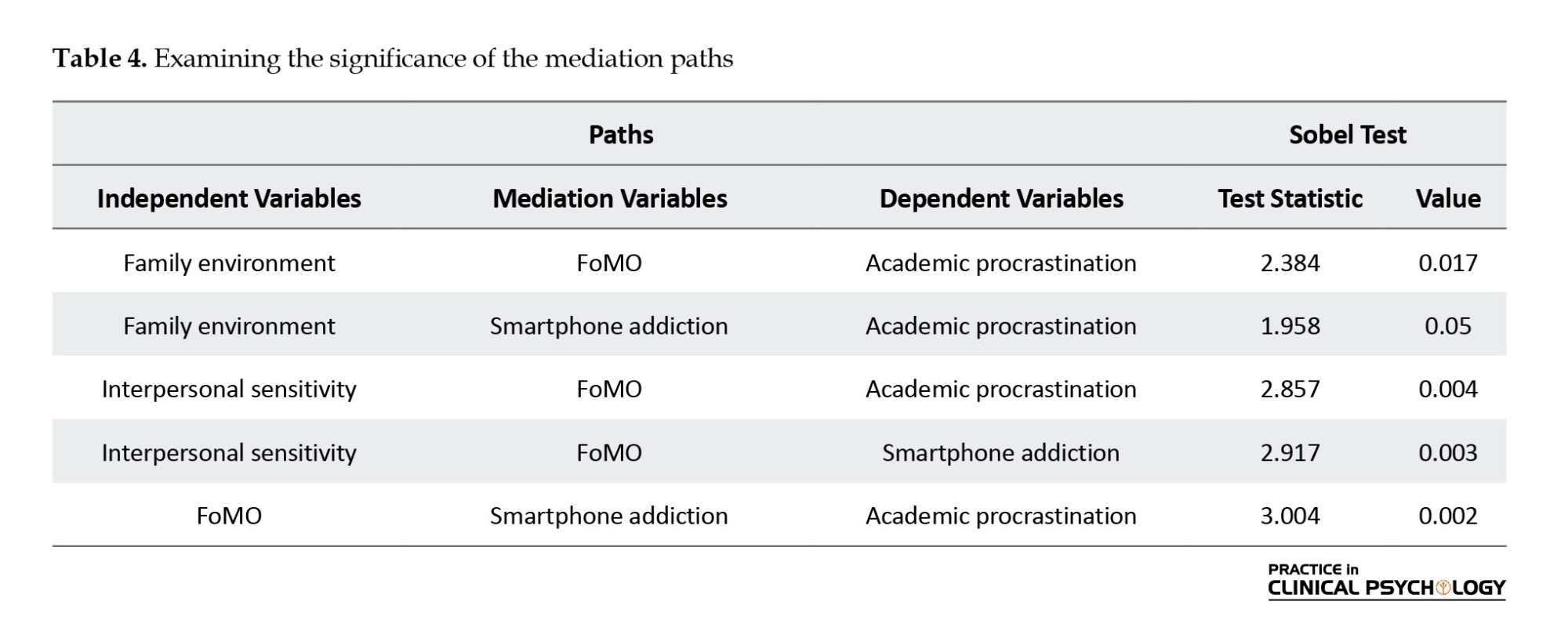

The results of the Sobel test in Table 4 show that FoMO significantly mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and academic procrastination. FoMO also significantly mediates the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. According to the results of Table 4 and the Sobel test, it can be stated that interpersonal sensitivity affects smartphone addiction and academic procrastination through FoMO. In addition, the results show that smartphone addiction significantly mediates the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. As Figure 1 shows, the variables of family environment and interpersonal sensitivity do not directly affect academic procrastination. The total effect size of the path of family environment on academic procrastination is -0.15, and the effect of interpersonal sensitivity on academic procrastination is 0.172.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationships between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination among adolescent girls. The findings revealed significant positive correlations among academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. In contrast, family environment demonstrated significant negative correlations with academic procrastination, FoMO, and smartphone addiction. The observed association between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination is consistent with prior studies (Geng et al., 2018; Rozgonjuk & Kattago, 2018; Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020; Imani & Zakeri, 2023). Social media platforms satisfy the innate human need for social connection and provide continuous social rewards that activate the brain’s reward system (Meshi et al., 2015). Checking smartphones for notifications often becomes an automatic, impulsive behavior performed without conscious awareness (Shapka, 2019). Excessive time spent browsing the internet and engaging with social media can result in neglect of academic responsibilities, thereby fostering procrastination (Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020).

With respect to FoMO and academic procrastination, the findings align with those of Manap et al. (2023). Exposure to continuous streams of social media content—such as peers’ posts, photos, and videos—can evoke pervasive feelings of FoMO (Milyavskaya et al., 2018). On these platforms, individuals often share idealized versions of their experiences, which, due to adolescents’ cognitive immaturity, are not recognized as selective or distorted portrayals. As a result, upward social comparisons on social networks may impair both academic performance and psychological well-being (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). FoMO often arises from social pressures, concerns about falling behind peers, and the inability to meet high academic or familial expectations. Such fears can heighten anxiety and stress, which in turn contribute to procrastinatory behaviors (Wu et al., 2025). Moreover, students may worry that being offline will prevent them from keeping up with others’ experiences, thereby missing out on potentially valuable social opportunities (Gupta et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013). This preoccupation may lead them to postpone academic tasks as a way to avoid anxiety and distress. Consequently, FoMO—particularly under conditions of social and academic pressure—may provoke maladaptive responses to school-related responsibilities, ultimately resulting in greater academic procrastination (Aslam & Malik, 2024).

In this study, although interpersonal sensitivity was correlated with academic procrastination, it did not exert a significant direct effect on the model fit and was therefore excluded. This result is consistent with the findings of Shi et al. (2024), Sapmaz (2023), and Küçükal and Sahranç (2022). Interpersonal sensitivity—characterized by excessive concern about others’ opinions and fear of negative evaluation—can heighten anxiety and lead individuals to avoid situations in which they may be judged, including homework and academic activities that require performance. Consequently, such students may delay or prevent academic tasks as a way of escaping this anxiety (Shi et al., 2024). Furthermore, students with high interpersonal sensitivity often experience fear of failure when facing academic assignments and may procrastinate due to concerns about not achieving the desired outcome. From this perspective, procrastination can function as a defense mechanism, temporarily shielding individuals from anxiety but ultimately impairing academic performance and increasing stress (Sapmaz et al., 2023). In addition, students with high interpersonal sensitivity tend to feel more helpless, are overly preoccupied with others’ reactions, and may develop perfectionistic tendencies. Since achieving unrealistically high standards is often unattainable, they may avoid or postpone academic tasks altogether (Küçükal & Sahranç, 2022).

The study also revealed that although the family environment was negatively correlated with academic procrastination, it did not have a significant direct effect on the model fit. Prior research has similarly shown that positive family relationships and supportive family climates are negatively associated with procrastination (Uzun et al., 2022; Heidariezadeh et al., 2022; Hamidipour & Izadi, 2023). High-quality family interactions and a positive emotional atmosphere can indirectly reduce procrastination by fostering psychological resources such as a positive self-image. For example, Erzen and Çikrıkci (2018) demonstrated that receiving social support from family helps decrease academic procrastination. When family members provide warm, supportive, and constructive interactions, adolescents feel psychologically secure and show greater commitment to academic responsibilities (Uzun et al., 2022). Conversely, unfavorable family dynamics may heighten stress, impair concentration, and diminish motivation, all of which increase the likelihood of procrastination. Attachment theory further suggests that weak or conflictual family bonds and maladaptive communication patterns may create emotional insecurity in children, reducing academic motivation and increasing procrastinatory behavior (Huang et al., 2022). Positive family relationships act as protective factors by fostering effective coping, time management, and responsibility in adolescents, whereas unsupportive family environments increase vulnerability to disorganization, avoidance, and procrastination.

The present findings on the relationship between family environment and smartphone addiction are consistent with previous research (Zhong et al., 2011; Bleakley et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2017). In families lacking emotional bonds, opportunities for expressing emotions are limited, and high levels of conflict may drive members to seek refuge in environments that meet their psychological needs. Studies indicate that unmet emotional and communication needs within the family can lead to feelings of loneliness, increased online emotional support-seeking, and ultimately smartphone addiction (Shi et al., 2017; Lian et al., 2021; Pooragha Roodbarde et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2020; Tsitsika et al., 2011). Conversely, adolescents who feel valued in their families exhibit lower levels of smartphone addiction (Su et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). Problematic family relationships can also generate tension and anxiety, which may be managed through excessive smartphone use (Hawi & Samaha, 2017).

Similarly, the relationship between family environment, FoMO, and smartphone addiction aligns with prior studies (Chen & Chen, 2022; Alt & Boniel-Nissim, 2018; Bloemen & De Coninck, 2020). Adolescents who do not experience security, intimacy, or understanding at home may turn to smartphones and social networks to fulfill emotional needs, engage socially, and gain approval, potentially fostering strong dependence on digital devices and weakening real-life family connections (Gao et al., 2022). Warm and supportive parental interactions can model healthier technology use. In contrast, limited engagement or strict, authoritarian parenting may increase the risk of smartphone addiction, as adolescents use devices to escape family tension and gain autonomy (Gong et al., 2022). Moreover, a positive family environment reduces the likelihood of FoMO by fulfilling adolescents’ need for belonging and minimizing the pressure to monitor peers’ social activities. In contrast, poor or tense family interactions may prompt adolescents to seek social approval externally, heightening FoMO, emotional instability, and anxiety (Topino et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2024).

Although this study found that interpersonal sensitivity was significantly associated with smartphone addiction, it did not exert a direct effect in the proposed model. These findings align with previous research (Lin et al., 2021; Yılmaz & Bekaroğlu, 2022; Kuss et al., 2012; Basharpoor et al., 2020; Tahmasebi et al., 2021; Suzuki et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2023; You et al., 2019; Jadidi & Sharifi, 2018). Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity experience greater challenges in relationships due to their need for approval, shame, and sensitivity to criticism (Boyce & Parker, 1989). Such adolescents are more likely to use the internet to form relationships and seek emotional support (Kuss et al., 2012), as research shows that greater interpersonal difficulties are associated with increased social network use during adolescence (Rudolph et al., 2016; Prinstein & Giletta, 2020; Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Online environments reduce barriers to social interaction, allowing these adolescents to relieve feelings of loneliness and satisfy their need for belonging, which can increase the risk of excessive smartphone use and addiction (Oosterhoff et al., 2020).

Regarding interpersonal sensitivity and FoMO, the findings are consistent with Lin et al. (2021) and Yılmaz and Bekaroğlu (2022). Adolescents with high interpersonal sensitivity have a heightened need for approval and acceptance, prompting them to monitor peers’ activities on social networks closely. The need for belonging has been identified as a key predictor of FoMO (Alabri, 2022). These adolescents often have lower self-esteem and depend heavily on social validation; FoMO on social interactions or group events can generate anxiety, leading to frequent checking of social networks and emotional instability (Pourshahriar et al., 2024).

The study also found a positive correlation between smartphone addiction and FoMO among female students, consistent with prior research (Zhang et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2021; Li & Ye, 2022; Liu et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2023). Students addicted to smartphones and social networks often worry about missing social or cultural updates. FoMO, amplified by the perception of falling behind peers in social information, drives adolescents to spend excessive time on smartphones to stay informed and socially connected (Li & Ye, 2022). This effect is particularly pronounced during adolescence, a critical period for identity formation and social development, when keeping up with peers is central to their sense of belonging and self-worth (Liu et al., 2024).

The results of the structural equation model also indicated that FoMO significantly mediated the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination. To our knowledge, this specific mediation has not been reported in previous research in either Persian or English. This finding aligns with Lin et al. (2021), who showed that FoMO mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and smartphone addiction. Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity—characterized by dependence on others, low self-esteem, and limited self-worth—often struggle to form healthy social relationships (Boyce & Parker, 1989). In cyberspace, they may excessively monitor friends’ activities, experiencing anxiety and tension about missing out on social interactions. This constant engagement with social networks can consume time and interfere with academic responsibilities. Similarly, adolescents from conflictual or cold family environments may seek refuge online, prioritizing interactions with peers over family communication. Such patterns increase opportunities for social comparison, reduce psychological well-being, heighten susceptibility to social rejection, and ultimately contribute to poorer academic performance (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019).

The results of the structural equation model indicated that smartphone addiction mediated the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. This finding, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported in either Persian or English studies. It can be argued that a lack of quality family relationships fails to meet adolescents’ needs for acceptance, approval, and belonging. Moreover, family conflicts may create a sense of insecurity, prompting adolescents to seek refuge in social networks. Meeting these unmet needs through cyberspace reinforces excessive smartphone use, which in turn fosters smartphone addiction. Therefore, weak family relationships can be considered a risk factor for both smartphone addiction and FoMO, ultimately contributing to academic procrastination among adolescents. The study further revealed that FoMO mediated the relationship between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination. This result is consistent with the findings of Parveiz et al. (2023) and Manap et al. (2023). As highlighted, constant presence in cyberspace and persistent monitoring of others’ activities can intensify smartphone addiction and hinder individuals from fulfilling their academic responsibilities.

Despite these contributions, the study has certain limitations. First, the data collection relied on self-report questionnaires, which may be influenced by social desirability bias. Second, the sample consisted exclusively of female high school students in Mashhad, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Third, the research employed a correlational design, which precludes causal inferences regarding the observed relationships. Future research is encouraged to examine family relationship patterns separately—specifically, adolescents’ relationships with mothers and fathers—and their role in the studied variables. It would also be valuable to investigate the influence of specific social networks in fostering FoMO and smartphone addiction. Moreover, exploring the role of media literacy as a protective factor against FoMO and smartphone addiction is recommended. From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that interventions targeting academic procrastination should pay particular attention to cyberspace dependence, FoMO, family environment, and social skills deficits.

Conclusion

The results of the structural equation model indicated that interpersonal sensitivity and family environment influenced academic procrastination indirectly through smartphone addiction and FoMO. Adolescents who lack satisfying communication within the family and exhibit higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity are more vulnerable to FoMO and excessive smartphone use. In turn, FoMO exacerbates smartphone addiction, which ultimately contributes to greater academic procrastination. Strengthening family relationships and addressing interpersonal sensitivities through counseling and media literacy training can help reduce FoMO and smartphone addiction, thereby positively influencing adolescents’ academic outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran (Code: IR.UB.REC.1403.034). Additionally, informed consent was secured from all participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Malahat Amani and Ali Mohammadzadeh Ebrahimi; Methodology: Ali Mohammadzadeh Ebrahimi; Data collection and investigation: Zahra Pourabbas; Supervision, data analysis, and writing: Malahat Amani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students who participated in the study.

References

Academic procrastination is a prevalent issue among students, impacting approximately 40% to 95% of educational settings (Ozer et al., 2009). Academic procrastination takes many forms, including being late to class or being disorganized, postponing academic tasks, and avoiding tasks (González-Brignardello et al., 2023). Given the widespread use of the internet among young people and adolescents (Aznar-Dı´az et al., 2020), researchers have recently focused on the impact of using smartphones, social networks, and online games on academic performance and academic procrastination (Türel & Dokumaci, 2022).

Excessive internet use can cause psychological and physical problems, impairing academic, occupational, and social functioning (Jia et al., 2017; Evren et al., 2019). Internet addiction is a pathological condition that disrupts behavior and cognitive functioning (Sadock, 2015). Prolonged online activity, including social media and video consumption, often leads to neglect of responsibilities, promoting procrastination (Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020). Research across various countries consistently links excessive internet use with increased academic procrastination (Geng et al., 2018; Rozgonjuk & Kattago, 2018; Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020; Imani & Zakeri, 2023).

Social media effectively satisfies individuals’ need for social connection and curiosity by offering continuous access to information, services, and interpersonal interactions. Features such as notifications, likes, and friend requests serve as social rewards that activate the brain’s reward system, fostering habitual, often unconscious, engagement (Meshi et al., 2015; Shapka, 2019). The tendency to present idealized self-images online encourages social comparison, contributing to increased anxiety, loneliness, depression, fear of rejection, academic difficulties, and diminished well-being (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). Exposure to peers’ curated content frequently triggers fear of missing out (FoMO), further reinforcing these negative effects (Milyavskaya et al., 2018). FoMO is a pervasive fear that others may have valuable experiences in one’s absence” (Gupta et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013). FoMO is a pervasive feeling associated with mental and emotional stress. Such stresses arise from the compulsive worry that one will miss out on a beneficial social experience, which is often observed on social media networks (Alabri, 2022). It is a common cross-cultural phenomenon, experienced by 60% of people (Zhang et al., 2021). FoMO and social comparison are significant predictors of social media addiction among youth (Parveiz et al., 2023). According to the compensatory internet use theory, individuals may turn to social media to cope with negative emotions such as FoMO. Yet, this behavior can create a self-reinforcing cycle in which FoMO both drives and is intensified by social media use (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Among students, the need for belonging has been identified as the strongest predictor of FoMO, both directly and indirectly through increased social media engagement, with women exhibiting higher levels of both (Alabri, 2022). FoMO has also been found to correlate positively with academic procrastination and internet addiction (Manap et al., 2023).

The school, family, peers, and social environment can influence adolescents’ use of the internet (Chaudhury & Tripathy, 2018). In particular, many studies point to the essential role of the family in smartphone addiction (Lam, 2020). Research evidence shows a relationship between family functioning and smartphone addiction (Zhong et al., 2011; Bleakley et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2017). The present study hypothesizes that family relationships influence smartphone addiction and FoMO. Family environment patterns provide information about each person’s perception of their family, including the perception of the socio-family atmosphere resulting from relationships, personal growth, organization, and control of the family system (Vianna et al., 2007). It includes the components of family cohesion (the emotional connection and bond of family members towards each other), emotional expressiveness (the emotional atmosphere and emotional expressive behaviors of family members), and conflict (the degree of free expression of anger, aggression, and conflict between family members) (Moos & Moos, 1994). Poor family functioning may lead to feelings of loneliness, increase the search for emotional support online, and ultimately lead to smartphone addiction (Shi et al., 2017; Lian et al., 2021; Pooragha Roodbarde et al., 2022). In a study of Taiwanese adolescents, Chen et al. (2020) found that male adolescents who had high financial support and a poor family atmosphere, and whose parents did not impose restrictions on internet use, were more susceptible to internet addiction. Studies indicate that a strong parent-adolescent relationship serves as a crucial protective factor, leading to fewer negative behaviors in adolescents. (Pace et al., 2014). In another study, Tsitsika et al. (2011) compared adolescents with internet addiction with normal adolescents. They found that a group of adolescents with internet addiction had significantly more dysfunctional family relationships and parental divorce. They also had poorer academic performance and the highest number of unexcused absences from school. In their systematic review, Kilinc and Yildiz (2019) identified that poor family relationships during adolescence play a significant role in the development of internet addiction. Conversely, the family environment is crucial for fostering self-esteem. Studies suggest that well-functioning families can boost self-esteem and lower the risk of smartphone addiction (Su et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). Hawi and Samaha (2017) observed that students addicted to smartphones tended to experience higher anxiety levels, and those with elevated anxiety often faced serious family relationship issues. Moreover, path analysis indicated that anxiety mediates the positive association between smartphone addiction and problematic family dynamics.

Regarding the relationship between family environment and FoMO, Chen and Chen (2022) found that family functioning directly affects FoMO and indirectly through addiction to social media and self-control. Residing in a dysfunctional family environment can lead individuals to feel isolated and excluded, prompting them to seek attention and approval from others while becoming more attuned to others’ feelings and situations (Chen & Chen, 2022). Research has also demonstrated that positive parent-child communication is linked to lower levels of FoMO (Alt & Boniel-Nissim, 2018). An adolescent’s family background is associated with the level of FoMO (Bloeman & De Coninck, 2020). Regarding the direct effect of family relationships on academic procrastination, Uzun et al. (2022), Heidariezadeh et al. (2022), and Hamidipour and Ezadian (2023) found that the emotional climate of the family was related to academic procrastination of students. In another study, Erzen and Çikrıkci (2018) found a significant relationship between academic procrastination and the level of social support perceived from family. In a warm and supportive family environment, positive interactions are established, and in such circumstances, children feel secure and, as a result, show greater commitment to their academic duties (Uzun et al., 2022).

Personality variables can also play a role in smartphone addiction and FoMO. Interpersonal sensitivity is a personality trait characterized by an extreme awareness of others’ behavior and feelings. In other words, interpersonal sensitivity refers to the degree to which individuals pay attention to the feelings, thoughts, and behavior of others about themselves. Individuals with these traits have been described as being excessively preoccupied with interpersonal relationships, vigilance, and sensitivity to aspects of interpersonal interactions. Individuals with interpersonal sensitivity tend to change their behavior to the expectations of others to minimize the risk of criticism and rejection (Boyce & Parker, 1989). The results of studies showed that internet addiction is positively correlated with interpersonal sensitivity (Basharpoor et al., 2010; Tahmasebi et al., 2021; Suzuki et al., 2023). Dai et al. (2023), You et al. (2019), and Jadidi and Sharifi (2018) found that adolescents with high internet and smartphone addiction had high scores in interpersonal sensitivity. Yılmaz and Bekaroğlu (2020) found in a study that by controlling for the effects of anxiety, depression, phobia, and obsession, the interpersonal sensitivity variable predicted smartphone addiction. The results of other studies show that maladjustment, isolation, alienation, and lack of communication skills, along with rejection, are associated with using social networks in adolescence (Rudolph et al., 2016; Prinstein & Giletta, 2020; Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Feelings of loneliness and the gain of a sense of belonging through group acceptance in adolescents (Oosterhoff et al., 2020) and the need for intimacy with peers may cause them to turn to smartphones (Yao & Zhong, 2014). To temporarily find a sense of belonging, intimacy, and participation through communication on social networks. Lin et al.’s (2021) study shows that interpersonal sensitivity is related positively to FoMO and smartphone addiction. Also, FoMO mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and mobile phone addiction. Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity may avoid situations where they are exposed to judgment from others, such as completing and submitting assignments, due to fear of negative evaluation. As a result, these individuals may procrastinate on homework or avoid starting academic activities to escape this anxiety (Shi et al., 2024).

Although academic procrastination has been widely studied across different student groups, limited research has explored how family environment and interpersonal sensitivity influence procrastination. Moreover, no prior study has investigated the mediating effects of FoMO and smartphone addiction on these relationships. To address this gap, the current study aims to examine the associations between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination, focusing on the mediating roles of FoMO and smartphone addiction among adolescent females.

Materials and Methods

The method of the present study is descriptive-correlational, of the structural equation (SEM) type. The statistical population comprised female students in the 10th to 12th grade living in Mashhad City, a northeastern province of Iran. According to the Cochran formula for populations over 3000 people, the sample size is estimated to be 386 people. To increase the power of the test, 400 people were considered as the sample. Participants were selected by a multi-stage cluster method. For this purpose, the city of Mashhad was clustered according to the number of education districts (7 districts). In the next stage, 5 high schools were randomly selected from each district, and one class was chosen from each school in each grade (10th, 11th, and 12th). After removing incomplete questionnaires, the sample size reached 384. Participants were distributed as follows: 10th grade, 33.85% (130 people); 11th grade, 38.28% (147 people); and 12th grade, 27.87% (107 people).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were having a smartphone, using it, and being willing to complete the questionnaires. The exclusion criteria were the participant’s questionnaire being corrupted and the participant’s absence from class during data collection.

Study instruments

Short form of family environment scale: Moos and Moos (1994) developed the long form of this scale with 27 items, and later a 16-item version was created. It includes subscales of cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict. The overall internal reliability was reported to be 0.88, and the subscales ranged from 0.65 to 0.83. The Cronbach α of the Persian version for the entire questionnaire was 0.81, and the subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.78. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good fit (0.96) (Kiani Chelmardi et al., 2018).

Interpersonal sensitivity measure (IPSM): Boyce and Parker (1989) generated a 36-item IPSM to measure traits of interpersonal sensitivity such as interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and fragile inner self. Answering the questions is based on a 4-point Likert scale. The Cronbach α for the entire scale was 0.86, and the subscales ranged from 0.55 to 0.76, and the test re-test reliability was 0.7. Also, the correlation between clinical judgment on interpersonal sensitivity and the score of the interpersonal sensitivity questionnaire was reported to be 0.72 (Boyce & Parker, 1989). In Iran, it was reported that Cronbach α for the subscales was in the range of 0.7 to 0.51, and the total scale was reported to be 0.86 (Mohammadian et al., 2017).

Academic procrastination questionnaire: Sevari (2011) designed this self-report questionnaire for the Persian language to measure academic procrastination. This questionnaire has 12 items and 3 components, including deliberate procrastination, procrastination due to physical and mental fatigue, and procrastination due to lack of planning. It was reported that the reliability of Cronbach α for the entire questionnaire was 0.85, deliberate procrastination was 0.77, procrastination due to physical and mental fatigue was 0.6, and procrastination due to lack of planning was 0.7. The correlation of this questionnaire with the Tuckman procrastination scale (1991) was 0.35.

Mobile phone addiction questionnaire: Sevari (2014) developed this scale to measure Iranian students’ dependence on mobile phones. This questionnaire has 13 items and subscales of de-creativity, tendency, and loneliness. The questions are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The Cronbach α of the questionnaire was reported to be 0.85, and the results of confirmatory factor analysis indicate a good fit (Sevari, 2014).

Persian version of the FoMO scale: The original version of the FoMO scale was designed by Przybylski et al. (2013) with 10 items that were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The designers of the questionnaire reported that the internal consistency was between 0.87 and 0.9. This questionnaire has been redeveloped and standardized for adolescents in Iran. The Persian version consists of 18 items and subscales of loss, compulsion, and comparison. Its reliability was reported to be 0.95, and its goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis was reported to be 0.62 (Asadi & Sharifi, 2022).

Results

Demographic findings showed that the age range of the participants was 15 to 19 years, with a mean of 16.86 and a standard deviation of 0.85.

Table 1 shows the amount and types of smartphone usage, with most participants using their smartphones for one to three hours a day, primarily for social media.

Table 2 presents the minimum and maximum values, Mean±SD, and correlations among the variables. Findings indicate that overall family environment scores are significantly negatively correlated with academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. Additionally, significant positive correlations were found among academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. Structural equation modeling was employed to examine the mediating effects of smartphone addiction and FoMO on the relationships between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination.

In the initial model, direct paths were drawn from interpersonal sensitivity and family environment to academic procrastination, which were removed in the revised model due to their non-significance. Also, the direct path from interpersonal sensitivity to smartphone addiction was removed due to the non-significance of the effect. The proposed model was fitted as shown in Figure 1, and the results of the direct paths are given in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the effects of the paths of family environment to FoMO (-0.288), family environment to smartphone addiction (-0.151), interpersonal sensitivity to FoMO (0.398), smartphone addiction to academic procrastination (0.304), FoMO to smartphone addiction (0.496), and FoMO to academic procrastination (0.282) are statistically significant. The results also show that the amount of explained variance (r2) for the smartphone addiction variable is 0.429, FoMO is 0.251, and academic procrastination is 0.269.

Model fit was acceptable, chi-square to the degrees of freedom (χ²/df )=2.02, goodness-of-fit index (GFI)=0.94, incremental goodness-of-fit index (IFI)=0.96, normalized fit index (NFI)=0.92, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.96, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)=0.94, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.052, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)=0.057 all meeting conventional thresholds for good fit (e.g. χ²/df <3, GFI/CFI/IFI/TLI ≥0.9, RMSEA ≤0.08, and SRMR ≤0.08) (Kline, 2016).

The results of the Sobel test in Table 4 show that FoMO significantly mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and academic procrastination. FoMO also significantly mediates the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. According to the results of Table 4 and the Sobel test, it can be stated that interpersonal sensitivity affects smartphone addiction and academic procrastination through FoMO. In addition, the results show that smartphone addiction significantly mediates the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. As Figure 1 shows, the variables of family environment and interpersonal sensitivity do not directly affect academic procrastination. The total effect size of the path of family environment on academic procrastination is -0.15, and the effect of interpersonal sensitivity on academic procrastination is 0.172.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationships between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination among adolescent girls. The findings revealed significant positive correlations among academic procrastination, FoMO, smartphone addiction, and interpersonal sensitivity. In contrast, family environment demonstrated significant negative correlations with academic procrastination, FoMO, and smartphone addiction. The observed association between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination is consistent with prior studies (Geng et al., 2018; Rozgonjuk & Kattago, 2018; Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020; Imani & Zakeri, 2023). Social media platforms satisfy the innate human need for social connection and provide continuous social rewards that activate the brain’s reward system (Meshi et al., 2015). Checking smartphones for notifications often becomes an automatic, impulsive behavior performed without conscious awareness (Shapka, 2019). Excessive time spent browsing the internet and engaging with social media can result in neglect of academic responsibilities, thereby fostering procrastination (Aznar-Díaz et al., 2020).

With respect to FoMO and academic procrastination, the findings align with those of Manap et al. (2023). Exposure to continuous streams of social media content—such as peers’ posts, photos, and videos—can evoke pervasive feelings of FoMO (Milyavskaya et al., 2018). On these platforms, individuals often share idealized versions of their experiences, which, due to adolescents’ cognitive immaturity, are not recognized as selective or distorted portrayals. As a result, upward social comparisons on social networks may impair both academic performance and psychological well-being (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). FoMO often arises from social pressures, concerns about falling behind peers, and the inability to meet high academic or familial expectations. Such fears can heighten anxiety and stress, which in turn contribute to procrastinatory behaviors (Wu et al., 2025). Moreover, students may worry that being offline will prevent them from keeping up with others’ experiences, thereby missing out on potentially valuable social opportunities (Gupta et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013). This preoccupation may lead them to postpone academic tasks as a way to avoid anxiety and distress. Consequently, FoMO—particularly under conditions of social and academic pressure—may provoke maladaptive responses to school-related responsibilities, ultimately resulting in greater academic procrastination (Aslam & Malik, 2024).

In this study, although interpersonal sensitivity was correlated with academic procrastination, it did not exert a significant direct effect on the model fit and was therefore excluded. This result is consistent with the findings of Shi et al. (2024), Sapmaz (2023), and Küçükal and Sahranç (2022). Interpersonal sensitivity—characterized by excessive concern about others’ opinions and fear of negative evaluation—can heighten anxiety and lead individuals to avoid situations in which they may be judged, including homework and academic activities that require performance. Consequently, such students may delay or prevent academic tasks as a way of escaping this anxiety (Shi et al., 2024). Furthermore, students with high interpersonal sensitivity often experience fear of failure when facing academic assignments and may procrastinate due to concerns about not achieving the desired outcome. From this perspective, procrastination can function as a defense mechanism, temporarily shielding individuals from anxiety but ultimately impairing academic performance and increasing stress (Sapmaz et al., 2023). In addition, students with high interpersonal sensitivity tend to feel more helpless, are overly preoccupied with others’ reactions, and may develop perfectionistic tendencies. Since achieving unrealistically high standards is often unattainable, they may avoid or postpone academic tasks altogether (Küçükal & Sahranç, 2022).

The study also revealed that although the family environment was negatively correlated with academic procrastination, it did not have a significant direct effect on the model fit. Prior research has similarly shown that positive family relationships and supportive family climates are negatively associated with procrastination (Uzun et al., 2022; Heidariezadeh et al., 2022; Hamidipour & Izadi, 2023). High-quality family interactions and a positive emotional atmosphere can indirectly reduce procrastination by fostering psychological resources such as a positive self-image. For example, Erzen and Çikrıkci (2018) demonstrated that receiving social support from family helps decrease academic procrastination. When family members provide warm, supportive, and constructive interactions, adolescents feel psychologically secure and show greater commitment to academic responsibilities (Uzun et al., 2022). Conversely, unfavorable family dynamics may heighten stress, impair concentration, and diminish motivation, all of which increase the likelihood of procrastination. Attachment theory further suggests that weak or conflictual family bonds and maladaptive communication patterns may create emotional insecurity in children, reducing academic motivation and increasing procrastinatory behavior (Huang et al., 2022). Positive family relationships act as protective factors by fostering effective coping, time management, and responsibility in adolescents, whereas unsupportive family environments increase vulnerability to disorganization, avoidance, and procrastination.

The present findings on the relationship between family environment and smartphone addiction are consistent with previous research (Zhong et al., 2011; Bleakley et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2017). In families lacking emotional bonds, opportunities for expressing emotions are limited, and high levels of conflict may drive members to seek refuge in environments that meet their psychological needs. Studies indicate that unmet emotional and communication needs within the family can lead to feelings of loneliness, increased online emotional support-seeking, and ultimately smartphone addiction (Shi et al., 2017; Lian et al., 2021; Pooragha Roodbarde et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2020; Tsitsika et al., 2011). Conversely, adolescents who feel valued in their families exhibit lower levels of smartphone addiction (Su et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). Problematic family relationships can also generate tension and anxiety, which may be managed through excessive smartphone use (Hawi & Samaha, 2017).

Similarly, the relationship between family environment, FoMO, and smartphone addiction aligns with prior studies (Chen & Chen, 2022; Alt & Boniel-Nissim, 2018; Bloemen & De Coninck, 2020). Adolescents who do not experience security, intimacy, or understanding at home may turn to smartphones and social networks to fulfill emotional needs, engage socially, and gain approval, potentially fostering strong dependence on digital devices and weakening real-life family connections (Gao et al., 2022). Warm and supportive parental interactions can model healthier technology use. In contrast, limited engagement or strict, authoritarian parenting may increase the risk of smartphone addiction, as adolescents use devices to escape family tension and gain autonomy (Gong et al., 2022). Moreover, a positive family environment reduces the likelihood of FoMO by fulfilling adolescents’ need for belonging and minimizing the pressure to monitor peers’ social activities. In contrast, poor or tense family interactions may prompt adolescents to seek social approval externally, heightening FoMO, emotional instability, and anxiety (Topino et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2024).

Although this study found that interpersonal sensitivity was significantly associated with smartphone addiction, it did not exert a direct effect in the proposed model. These findings align with previous research (Lin et al., 2021; Yılmaz & Bekaroğlu, 2022; Kuss et al., 2012; Basharpoor et al., 2020; Tahmasebi et al., 2021; Suzuki et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2023; You et al., 2019; Jadidi & Sharifi, 2018). Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity experience greater challenges in relationships due to their need for approval, shame, and sensitivity to criticism (Boyce & Parker, 1989). Such adolescents are more likely to use the internet to form relationships and seek emotional support (Kuss et al., 2012), as research shows that greater interpersonal difficulties are associated with increased social network use during adolescence (Rudolph et al., 2016; Prinstein & Giletta, 2020; Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Online environments reduce barriers to social interaction, allowing these adolescents to relieve feelings of loneliness and satisfy their need for belonging, which can increase the risk of excessive smartphone use and addiction (Oosterhoff et al., 2020).

Regarding interpersonal sensitivity and FoMO, the findings are consistent with Lin et al. (2021) and Yılmaz and Bekaroğlu (2022). Adolescents with high interpersonal sensitivity have a heightened need for approval and acceptance, prompting them to monitor peers’ activities on social networks closely. The need for belonging has been identified as a key predictor of FoMO (Alabri, 2022). These adolescents often have lower self-esteem and depend heavily on social validation; FoMO on social interactions or group events can generate anxiety, leading to frequent checking of social networks and emotional instability (Pourshahriar et al., 2024).

The study also found a positive correlation between smartphone addiction and FoMO among female students, consistent with prior research (Zhang et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2021; Li & Ye, 2022; Liu et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2023). Students addicted to smartphones and social networks often worry about missing social or cultural updates. FoMO, amplified by the perception of falling behind peers in social information, drives adolescents to spend excessive time on smartphones to stay informed and socially connected (Li & Ye, 2022). This effect is particularly pronounced during adolescence, a critical period for identity formation and social development, when keeping up with peers is central to their sense of belonging and self-worth (Liu et al., 2024).

The results of the structural equation model also indicated that FoMO significantly mediated the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity, family environment, and academic procrastination. To our knowledge, this specific mediation has not been reported in previous research in either Persian or English. This finding aligns with Lin et al. (2021), who showed that FoMO mediates the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and smartphone addiction. Individuals with high interpersonal sensitivity—characterized by dependence on others, low self-esteem, and limited self-worth—often struggle to form healthy social relationships (Boyce & Parker, 1989). In cyberspace, they may excessively monitor friends’ activities, experiencing anxiety and tension about missing out on social interactions. This constant engagement with social networks can consume time and interfere with academic responsibilities. Similarly, adolescents from conflictual or cold family environments may seek refuge online, prioritizing interactions with peers over family communication. Such patterns increase opportunities for social comparison, reduce psychological well-being, heighten susceptibility to social rejection, and ultimately contribute to poorer academic performance (Abel et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019).

The results of the structural equation model indicated that smartphone addiction mediated the relationship between family environment and academic procrastination. This finding, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported in either Persian or English studies. It can be argued that a lack of quality family relationships fails to meet adolescents’ needs for acceptance, approval, and belonging. Moreover, family conflicts may create a sense of insecurity, prompting adolescents to seek refuge in social networks. Meeting these unmet needs through cyberspace reinforces excessive smartphone use, which in turn fosters smartphone addiction. Therefore, weak family relationships can be considered a risk factor for both smartphone addiction and FoMO, ultimately contributing to academic procrastination among adolescents. The study further revealed that FoMO mediated the relationship between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination. This result is consistent with the findings of Parveiz et al. (2023) and Manap et al. (2023). As highlighted, constant presence in cyberspace and persistent monitoring of others’ activities can intensify smartphone addiction and hinder individuals from fulfilling their academic responsibilities.

Despite these contributions, the study has certain limitations. First, the data collection relied on self-report questionnaires, which may be influenced by social desirability bias. Second, the sample consisted exclusively of female high school students in Mashhad, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Third, the research employed a correlational design, which precludes causal inferences regarding the observed relationships. Future research is encouraged to examine family relationship patterns separately—specifically, adolescents’ relationships with mothers and fathers—and their role in the studied variables. It would also be valuable to investigate the influence of specific social networks in fostering FoMO and smartphone addiction. Moreover, exploring the role of media literacy as a protective factor against FoMO and smartphone addiction is recommended. From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that interventions targeting academic procrastination should pay particular attention to cyberspace dependence, FoMO, family environment, and social skills deficits.

Conclusion

The results of the structural equation model indicated that interpersonal sensitivity and family environment influenced academic procrastination indirectly through smartphone addiction and FoMO. Adolescents who lack satisfying communication within the family and exhibit higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity are more vulnerable to FoMO and excessive smartphone use. In turn, FoMO exacerbates smartphone addiction, which ultimately contributes to greater academic procrastination. Strengthening family relationships and addressing interpersonal sensitivities through counseling and media literacy training can help reduce FoMO and smartphone addiction, thereby positively influencing adolescents’ academic outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran (Code: IR.UB.REC.1403.034). Additionally, informed consent was secured from all participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Malahat Amani and Ali Mohammadzadeh Ebrahimi; Methodology: Ali Mohammadzadeh Ebrahimi; Data collection and investigation: Zahra Pourabbas; Supervision, data analysis, and writing: Malahat Amani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students who participated in the study.

References

Abel, J. P., Buff, C. L., & Burr, S. A. (2016). Social media and the fear of missing out: Scale development and assessment. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 14(1), 1-12. [DOI:10.19030/jber.v14i1.9554]

Alabri, A. (2022). Fear of missing out (FoMO): The effects of the need to belong, perceived centrality, and fear of social exclusion. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2022, 1-12. [DOI:10.1155/2022/4824256]

Alt, D., & Boniel-Nissim, M. (2018). Parent-adolescent communication and problematic Internet use: The mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO). Journal of Family Issues, 39(13), 3391-3409. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X18783493]

Aznar-Díaz, I., Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., García-González, A., & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2020). Mexican and Spanish university students’ Internet addiction and academic procrastination: Correlation and potential factors. Plos One, 15(5), e0233655. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0233655] [PMID]

Asadi, H. & Sharifi, F. (2022). [Compilation and validation of the fear of missing scale in Iranian society (Persian)]. Applied Research in Consulting, 5(2), 147-169. [Link]

Aslam, I., & Malik, J. A. (2024). Fear of missing out and procrastination among university students: Investigating the mediating role of screen time. CARC Research in Social Sciences, 3(2), 206-213. [DOI:10.58329/criss.v3i2.122]

Basharpoor, S., Ahmadi, S., &Heidari, F. (2021). [Modeling internet addiction based on interpersonal sensitivity and parents’ marital conflict with the mediating role of effortful control in students of Ardabil City in the 2020 academic year: A descriptive study (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, 19(10), 1053-1070. [DOI:10.29252/jrums.19.10.1053]

Bleakley, A., Ellithorpe, M., & Romer, D. (2016). The role of parents in problematic internet use among US adolescents. Media and Communication, 4(3), 24-34. [DOI:10.17645/mac.v4i3.523]

Bloemen, N., & De Coninck, D. (2020). Social media and fear of missing out in adolescents: The role of family characteristics. Social Media+Society, 6(4). [DOI:10.1177/2056305120965517]

Boyce, P., & Parker, G. (1989). development of a scale to measure interpersonal sensitivity. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 23(3), 341-351. [DOI:10.1177/000486748902300320]

Chaudhury, P., & Tripathy, H. K. (2018). A study on impact of smartphone addiction on academic performance. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(2.6), 50-53. [DOI:10.14419/ijet.v7i2.6.10066]

Chen Q., & Chen, Y. (2022). The relationship between family function and fear of missing out: A serial mediation model. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Big Data and Education. New York, USA; 2022 February 28. [DOI:10.1145/3524383.3524437]

Chen, H. C., Wang, J. Y., Lin, Y. L., & Yang, S. Y. (2020). Association of internet addiction with family functionality, depression, self-efficacy and self-esteem among early adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8820. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17238820] [PMID]

Dai, W., Wei, X., Li, Q., & Yang, Z. (2023). Interpersonal sensitivity, smartphone addiction, connectedness to nature and life satisfaction among college students: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(6), 548-555. [DOI:10.1080/14330237.2023.2279374]

Ding, Q., Li, D., Zhou, Y., Dong, H., & Luo, J. (2017). Perceived parental monitoring and adolescent internet addiction: A moderated mediation model. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 48-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.033] [PMID]

Erzen, E., & Çikrıkci, Ö. (2018). The role of school attachment and parental social support in academic procrastination. Turkish Journal of Teacher Education, 7(1), 17-27. [Link]

Evren, C., Evren, B., Dalbudak, E., Topcu, M., & Kutlu, N. (2019). Relationships of Internet addiction and Internet gaming disorder symptom severities with probable attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, aggression and negative affect among university students. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(4), 413-421. [DOI:10.1007/s12402-019-00305-8] [PMID]

Gao, Q., Zheng, H., Sun, R., & Lu, S. (2022). Parent-adolescent relationships, peer relationships, and adolescent mobile phone addiction: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Addictive Behaviors, 129, 107260. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107260] [PMID]

Geng, J., Han, L., Gao, F., Jou, M., & Huang, C. C. (2018). Internet addiction and procrastination among Chinese young adults: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 320-333. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.013]

Gong, J., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Liang, Z., Hao, J., & Su, L., et al. (2022). How parental smartphone addiction affects adolescent smartphone addiction: The effect of the parent-child relationship and parental bonding. Journal of Affective Disorders, 307, 271-277. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.014] [PMID]

González-Brignardello, M. P., Sánchez-Elvira Paniagua, A., & López-González, M. Á. (2023). Academic procrastination in children and adolescents: A scoping review. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 10(6), 1016. [DOI:10.3390/children10061016] [PMID]

Gupta, M., & Sharma, A. (2021). Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(19), 4881-4889. [DOI:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.4881] [PMID]

Hamidipour, R. and Ezadian, E. (2023). [Prediction of academic procrastination based on bullying, victimization and family emotional behaviors in adolescents (Persian)]. Journal of Pouyesh in Education and Consultation (JPEC), 18(18), 262-283. [Link]

Heidariezadeh, B., Pakdaman, S. & Estabraghi, M. (2022). [The relationship between family emotional atmosphere and academic procrastination in students: the mediating role of cognitive inflexibility (experiential avoidance) (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research, 18(2), 371-386. [Link]

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). Relationships among smartphone addiction, anxiety, and family relations. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(10), 1046-1052. [DOI:10.1080/0144929X.2017.1336254]

Huang, H., Ding, Y., Liang, Y., Zhang, Y., Peng, Q., & Wan, X., et al. (2022). The mediating effects of coping style and resilience on the relationship between parenting style and academic procrastination among Chinese undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 351. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-022-01140-5] [PMID]

Imani, S., & Zakeri, M. (2023). [Comparing responsibility, procrastination, Academic vitality in students with and without Web addiction (Persian)]. Journal of School Psychology, 12(2), 18-6. [DOI:10.22098/jsp.2023.2366]

Jadidi, M., & Sharifi, M. (2018).comparison of impulsivity and interpersonal sensitivity in adolescents with internet addiction and normal adolescents. Journal of Psychology New Ideas, 2(6),1-15. [Link]

Jia, J., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., & Sun, W. (2017). Psychological security and deviant peer affiliation as mediators between teacher-student relationship and adolescent Internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 345-352. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.063]

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351-354. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059]

Kiani Chelmardi, A., Honarmand Ghojebeigloo, P., Khakdal, S & Zardi Geigloo, B. (2018). [Investigating psychometric characteristics of the brief family relationship scale and its correlation with suicide on high school students (Persian)]. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 8(1), 147-164. [DOI:10.22034/fcp.2018.60862]

Kilinc, G., Harmanci, P., Yildiz, E., & Cetin, N. (2019). Relationship between internet addiction in adolescents and family relationships: A systematic review. Journal of International Social Research 12(67), 609-618. [Link]

Kim, Y., Dhammasaccakarn, W., Laeheem, K., & Rinthaisong, I. (2024). Exploring associative relationships: Family functions, anxiety, and fear of missing out as predictors of smartphone addiction among Thai adolescents. Acta Psychologica, 250, 104570. [DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104570] [PMID]

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Küçükal, M., & Sahranç, Ü. (2022). Examining the relationships among internet addiction procrastination social support and anxiety sensitivity. Education Quarterly Reviews, 5(1), 26-37. [DOI:10.31014/aior.1993.05.01.443]

Kuss, D. J., Louws, J., & Wiers, R. W. (2012). Online gaming addiction? Motives predict addictive play behavior in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(9), 480-485. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2012.0034] [PMID]

Lam L. T. (2020). The roles of parent-and-child mental health and parental internet addiction in adolescent internet addiction: Does a parent-and-child gender match matter?. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 142. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00142] [PMID]

Lesnick, J., & Mendle, J. (2021). Rejection sensitivity and negative urgency: A proposed framework of intersecting risk for peer stress. Developmental Review, 62, 100998. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2021.100998]

Li, X., & Ye, Y. (2022). Fear of missing out and irrational procrastination in the mobile social media environment: A moderated mediation analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(1), 59-65. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2021.0052] [PMID]

Lian, S. L., Sun, X. J., Niu, G. F., Yang, X. J., Zhou, Z. K., & Yang, C. (2021). Mobile phone addiction and psychological distress among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of rumination and moderating role of the capacity to be alone. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 701-710. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.005] [PMID]

Lin, L., Wang, X., Li, Q., Xia, B., Chen, P., & Wang, W. (2021). The influence of interpersonal sensitivity on smartphone addiction: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 670223. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670223] [PMID]

Liu, N., Zhu, S., Zhang, W., Sun, Y., & Zhang, X. (2024). The relationship between fear of missing out and mobile phone addiction among college students: The mediating role of depression and the moderating role of loneliness. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1374522. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1374522] [PMID]