Volume 13, Issue 2 (Spring 2025)

PCP 2025, 13(2): 159-170 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fallah Tafti A, Hajiha Z, Momeni F, Dehghan M. Childhood Trauma and Identity Disturbance in Male Adolescents: Emotion Regulation and Executive Function as Mediators. PCP 2025; 13 (2) :159-170

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-997-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-997-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, School of behavioral sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,zo.hajiha@uswr.ac.ir

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Psychosis Research Centre, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Health Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, School of behavioral sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Psychosis Research Centre, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Health Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Executive function, Emotional regulation, Identity disturbance, Adverse childhood experiences, Adolescent

Full-Text [PDF 735 kb]

(1453 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2411 Views)

Full-Text: (544 Views)

Introduction

The essential task of adolescence and the most crucial aspect of human psychosocial development is establishing a stable and cohesive identity (Erikson, 1968). Identity disturbance, the pathological aspect of identity development, refers to a persistent and marked instability in an individual’s self-concept. It is characterized by a diminished capacity to define oneself, commit to values, goals, or relationships, and a distressing sense of incoherence (Lowe, 2017). Identity is associated with a wide range of psychosocial adaptations, and identity disturbance can serve as a transdiagnostic marker for psychopathology (Kaufman et al., 2014; Neacsiu et al., 2015; Hatano et al., 2018; Meeus et al., 2018). Given identity’s significance during adolescence and its maladaptive development’s negative consequences, identifying the factors influencing identity formation is essential.

One of the factors that can affect the development of identity and contribute to identity disturbance is childhood trauma (Dereboy et al., 2018). The term “childhood trauma” is defined as a broad, inclusive concept encompassing a range of adverse experiences occurring before the age of 18, including emotional and physical abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse (Back et al., 2021). Maltreatment is considered a significant public health concern. A review study reported the prevalence of physical abuse up to 58.2%, emotional abuse up to 91.6%, and neglect up to 85.3% among Iranian children, highlighting a critical situation that demands urgent attention (Salehian & Maleki- Saghooni, 2021). Although various studies have generally suggested a link between childhood trauma and identity development (Dereboy et al., 2018; Penner et al., 2019), the underlying mechanisms of this relationship have not been extensively explored. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms is essential for realizing the full potential of identity research in informing clinical practice, therapeutic interventions, and prevention strategies. Researchers in this field argue that one of the main reasons for this gap is a disconnection between developmental and clinical literature (Kaufman et al., 2014; Pasupathi, 2014; Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene et al., 2020).

According to the ecological-transactional model (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), from a developmental perspective, the formation of developmental milestones at each stage is built upon the healthy progression of previous stages. Childhood trauma can disrupt this trajectory, diverting individuals from a healthy developmental path at all critical milestones. Identity formation is fundamentally a cognitive and emotional process (Hatano et al., 2022). Given the temporal precedence of cognitive and emotional development over identity formation in the developmental process, childhood trauma can contribute to pathological identity development in adolescence by impairing cognitive and emotional processes.

One of the key cognitive variables is executive functions. Executive functions are neurocognitive skills supporting top-down, conscious control of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. They are essential for reasoning, goal-directed actions, emotion regulation, and complex social functioning. Additionally, they enable self-regulation learning and adaptation to changing circumstances (Diamond, 2013; Zelazo, 2015). Studies have shown that childhood trauma can have a detrimental impact on the development of executive functions, which is crucial for effective cognitive processing and self-regulation (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011). There is limited empirical evidence regarding the relationship between executive function deficits and identity disturbance. Nevertheless, it has been generally suggested that individuals with executive function impairments are more likely to experience identity disturbance. Furthermore, research indicates that developing executive functions is a prerequisite for identity formation (Shallala et al., 2020; Welsh & Schmitt-Wilson, 2013).

Emotion regulation is one of the processes that influence identity development and can be affected by childhood trauma. Emotion regulation consists of determining when and how emotions are experienced, how they change over time, and ultimately how they are expressed (Gross, 2013). Children who have experienced maltreatment exhibit significant difficulties in emotion regulation, emotional expression, and emotional recognition. Childhood maltreatment is considered a “critical threat” to the optimal development of emotional processing abilities (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). Moreover, substantial research has shown that challenges in emotion regulation predict identity disturbances in both clinical and non-clinical populations, as well as across a wide range of psychological disorders (Gratz et al., 2015; Neacsiu et al., 2014; Stepp et al., 2014).

Overall, previous studies have indicated associations among the variables examined in the present study. To the best of our knowledge, no research has investigated the combined impact of these variables. Given the necessity of further understanding the mechanisms and factors influencing identity development and their application in preventive and therapeutic interventions, the present study adopted a developmental-clinical perspective to examine the impact of childhood trauma on identity disturbance in adolescents, mediated by emotion regulation difficulties and executive function deficits.

Materials and Methods

The present study used a descriptive-cross-sectional design and structural equation modeling methodology. The study population consisted of 16- to 18-year-old adolescent boys. Of whom the target sample was selected through convenience and purposive sampling from students in various districts of Yazd City, Iran. Ultimately, data from 311 participants were included in the analysis. The inclusion criteria comprised male gender, being within the age range of 16 to 18 years, and willingness to participate voluntarily in the study. Participants with cognitive or neurodevelopmental disorders that impair cognitive abilities (CAs), severe psychiatric disorders, or substance use disorders were excluded from the study. This exclusion was initially based on self-report and subsequently confirmed through a clinical interview following diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) criteria. The exclusion criteria also included failure to respond to the questionnaire and desire to withdraw from the study.

Study instruments

Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ)

The CTQ is a self-report questionnaire developed by Bernstein et al. (Bernstein et al., 2003) to assess childhood adversity and trauma. Five subscales of CTQ evaluate these dimensions of childhood traumas: Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, emotional, and physical neglect. It consists of 28 items. Twenty-five items measure the core components of maltreatment, and three items can identify individuals who may be underestimating or denying their childhood traumas. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with scores for each subscale ranging from 5 to 25 and the total questionnaire score ranging from 25 to 125. Higher scores indicate a greater level of childhood trauma. Bernstein et al., (2003) reported that Cronbach α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.78 to 0.95. In Iran, reliability coefficients for the five subscales have been reported between 0.81 and 0.98 (Ebrahimi et al., 2014).

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale-short form (DERS-16)

Bjureberg et al. developed DERS-16 questionnaire (Bjureberg et al., 2016). The DERS-16 is a 16-item self-report tool that assesses five key aspects of difficulties in emotion regulation difficulties. It represents several challenges related to emotional regulation, including lack of emotional clarity, difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behavior, trouble controlling impulsive behaviors, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and a tendency not to accept emotional responses. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 16 to 96. Individuals who have greater difficulties in regulating emotions will get higher scores. Yigit and Yigit (2019) reported the Cronbach α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.78 to 0.92. In Iran, reliability coefficients have been reported to range from 0.68 to 0.77 (Fallahi et al., 2021).

Cognitive abilities (CA) questionnaire

Nejati developed CA, a 30-item self-report questionnaire (Nejati, 2013), to assess cognitive abilities. The questionnaire evaluates various cognitive functions, including memory, inhibitory control and selective attention, decision-making, planning, sustained attention, social cognition, and cognitive flexibility. Scoring is based on a Likert scale; the total score ranges from 30 to 150. Higher scores indicate greater deficits in cognitive abilities. The Cronbach α coefficient, as reported by its developer, is 0.83.

Assessment of identity development in adolescence (AIDA)

Goth et al. (2012) developed this self-report AIDA to assess identity development in terms of psychopathology in personality functioning among adolescents aged 12 to 18. The AIDA consists of 58 items and includes a total score indicating identity integration vs identity diffusion, two main dimensions (continuity vs discontinuity and coherence vs incoherence), and six subscales. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 0 to 232. The total score reflects identity diffusion; higher scores indicate greater identity impairment and an increased risk of personality disorders. Goth et al. (2012) reported the Cronbach α reliability coefficient as 0.94 for the overall scale, 0.87 and 0.92 for the two dimensions, and between 0.69 and 0.84 for the subscales. In Iran, the Cronbach α was reported as 0.95 for the overall scale, 0.89 and 0.92 for the two dimensions, and between 0.70 and 0.84 for the subscales.

Study procedure

After obtaining official approval and an execution permit from the Yazd Provincial Department of Education and securing an ethical code, the researchers visited three schools in Yazd selected by the Department of Education. Informed consent forms for participation in the study were distributed among students to be signed by their guardians. The questionnaires were distributed individually in a paper-and-pencil format among participants who met the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 400 questionnaires were collected. After excluding those that met the invalidity criteria in the CTQ and AIDA questionnaires, as well as incomplete or distorted responses, data from 311 participants were selected for analysis using SPSS software, version 27 and AMOS software, version 24.

Results

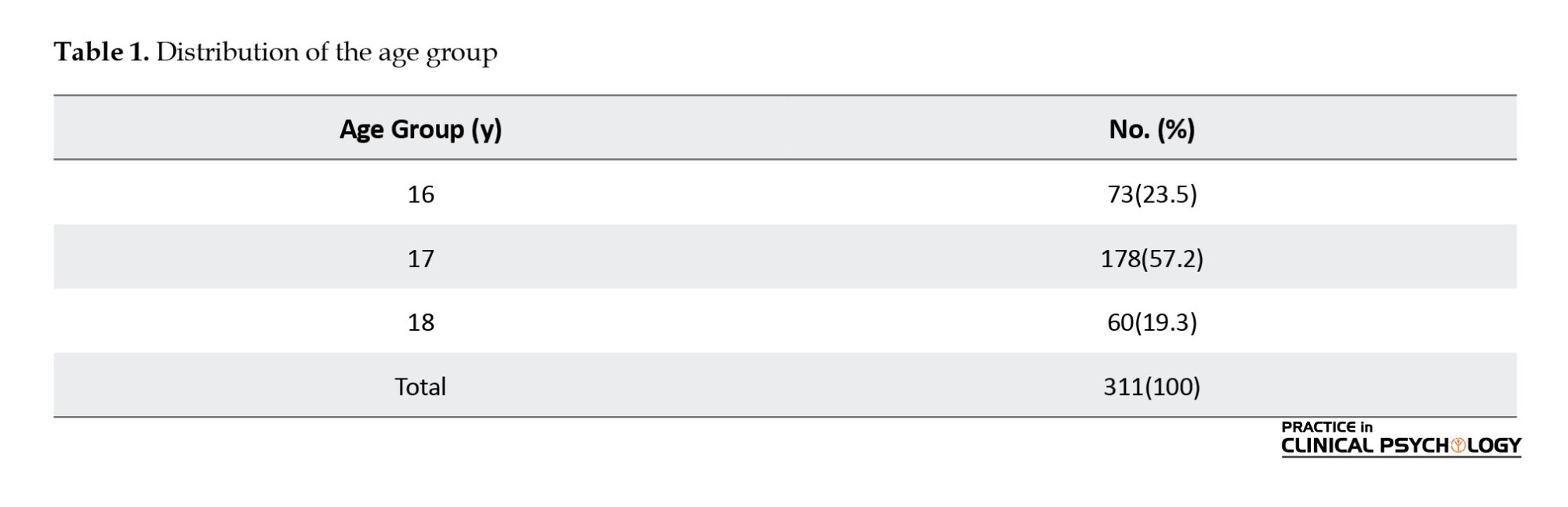

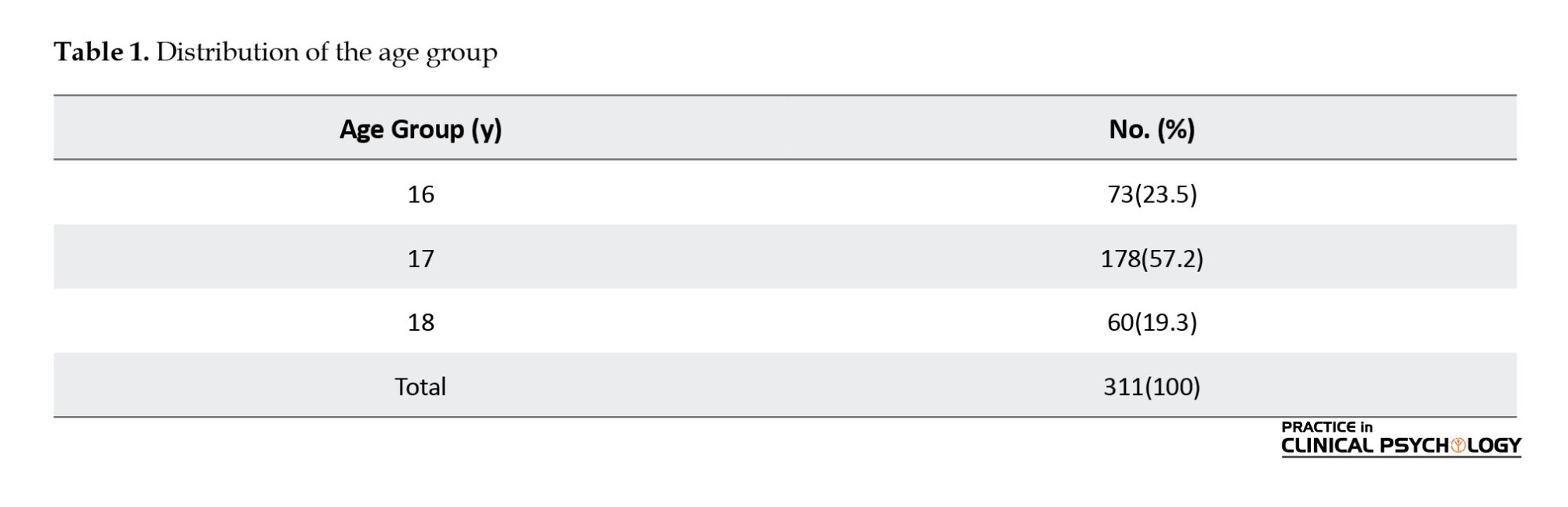

The age distribution of the participants in the study is presented in Table 1.

The majority of participants in the study belonged to the 17-year-old age group, with the mean age of participants being 16.95 years.

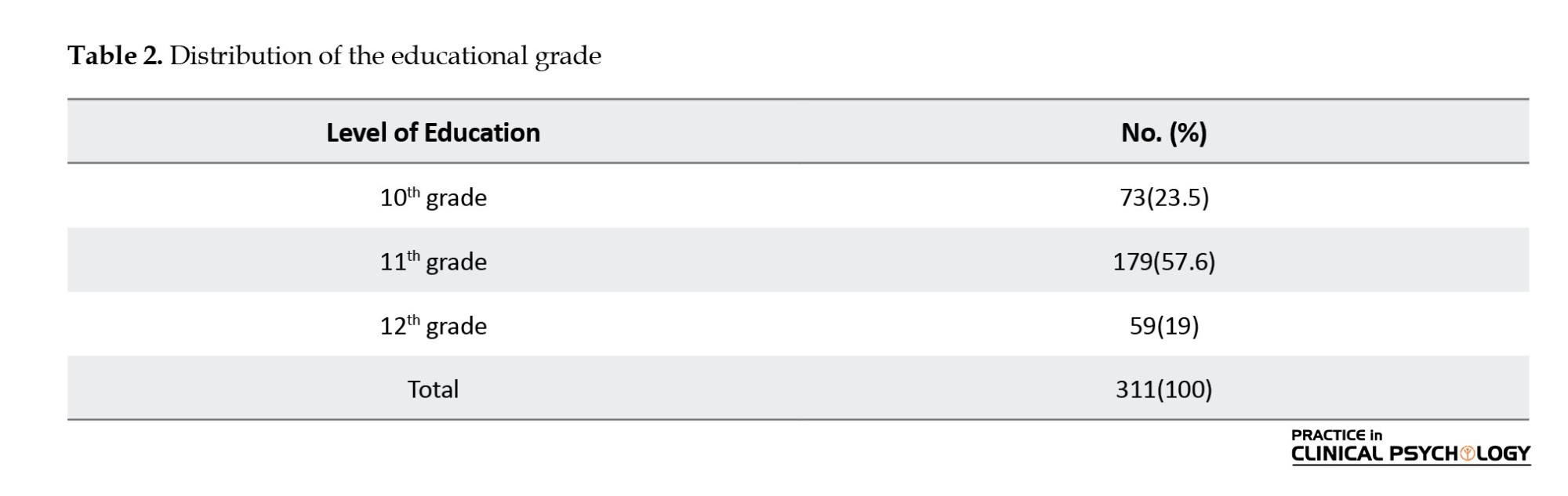

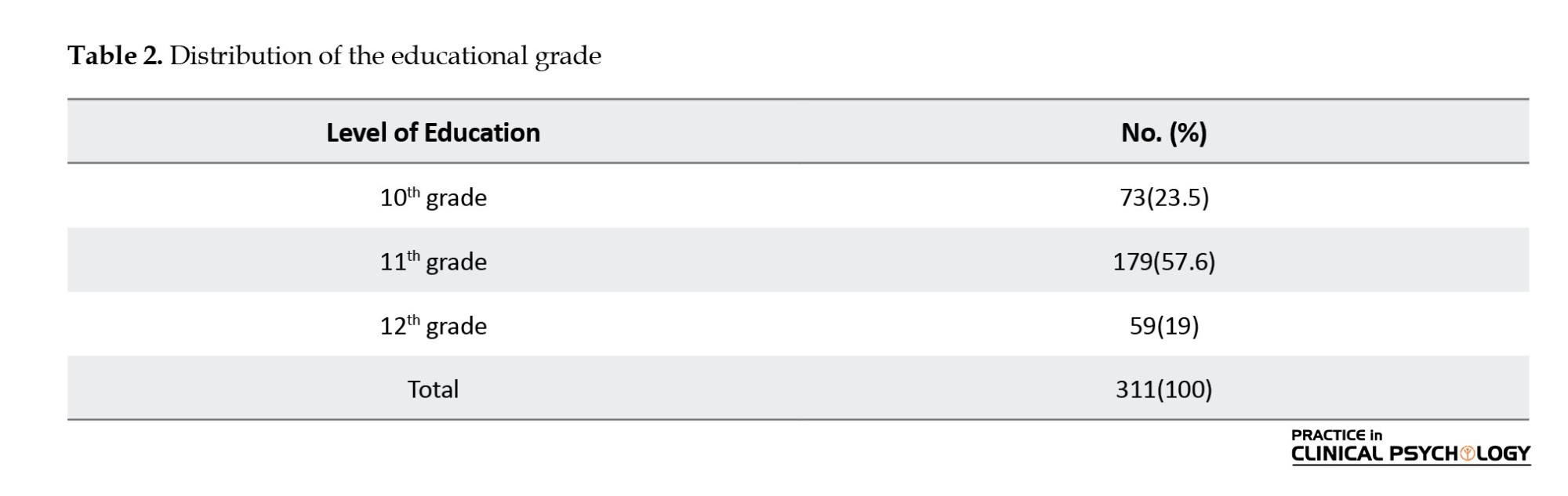

Table 2 presents the distribution of participants based on their grade level.

According to the results of the Table 2, most participants were studying in the 11th, 10th, and 12th grades, in that order.

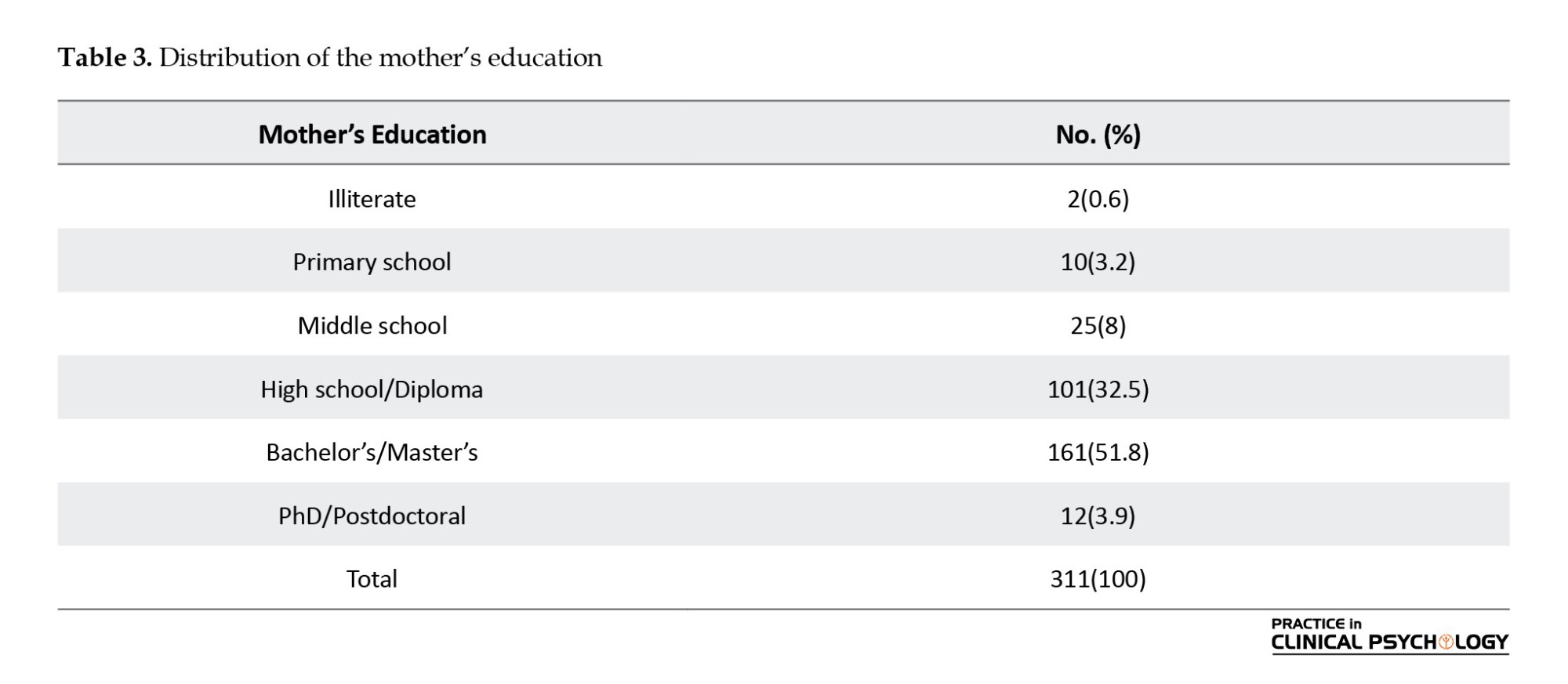

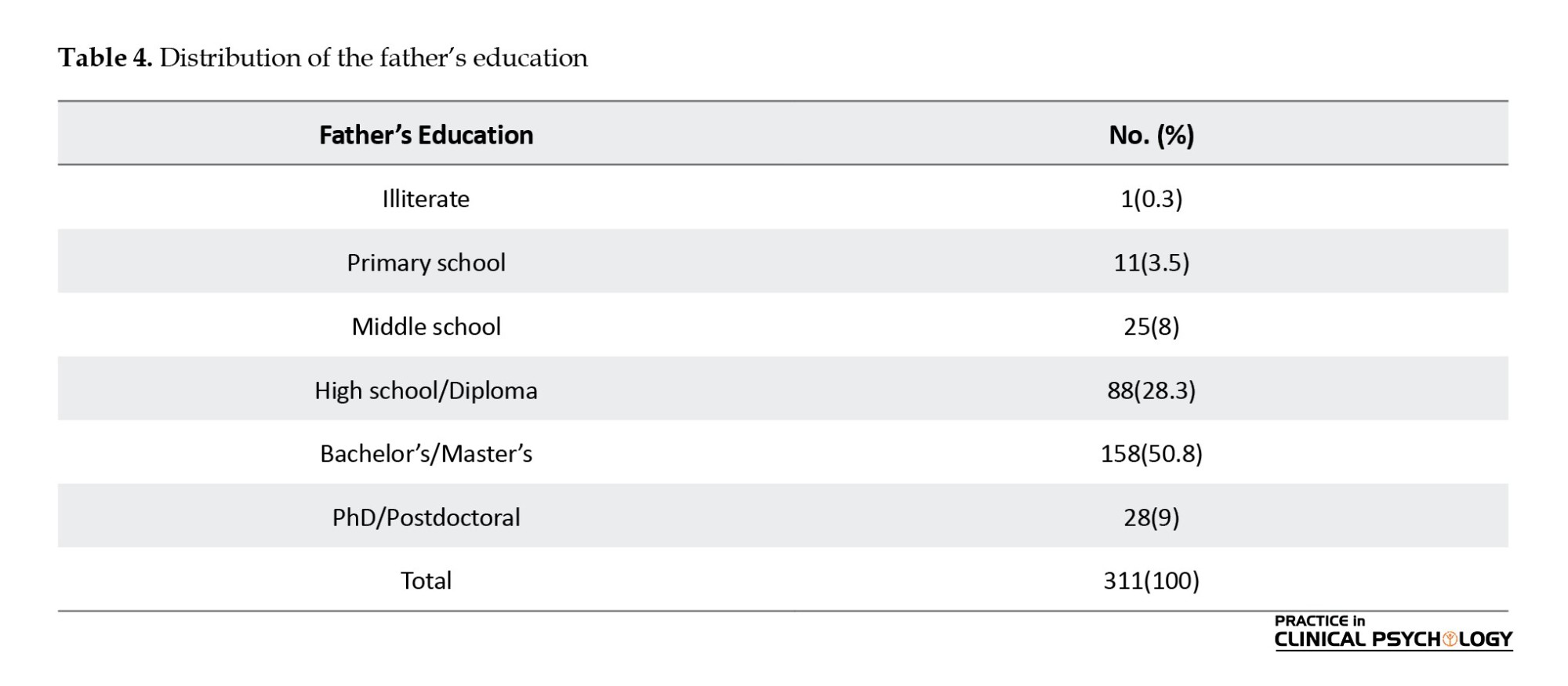

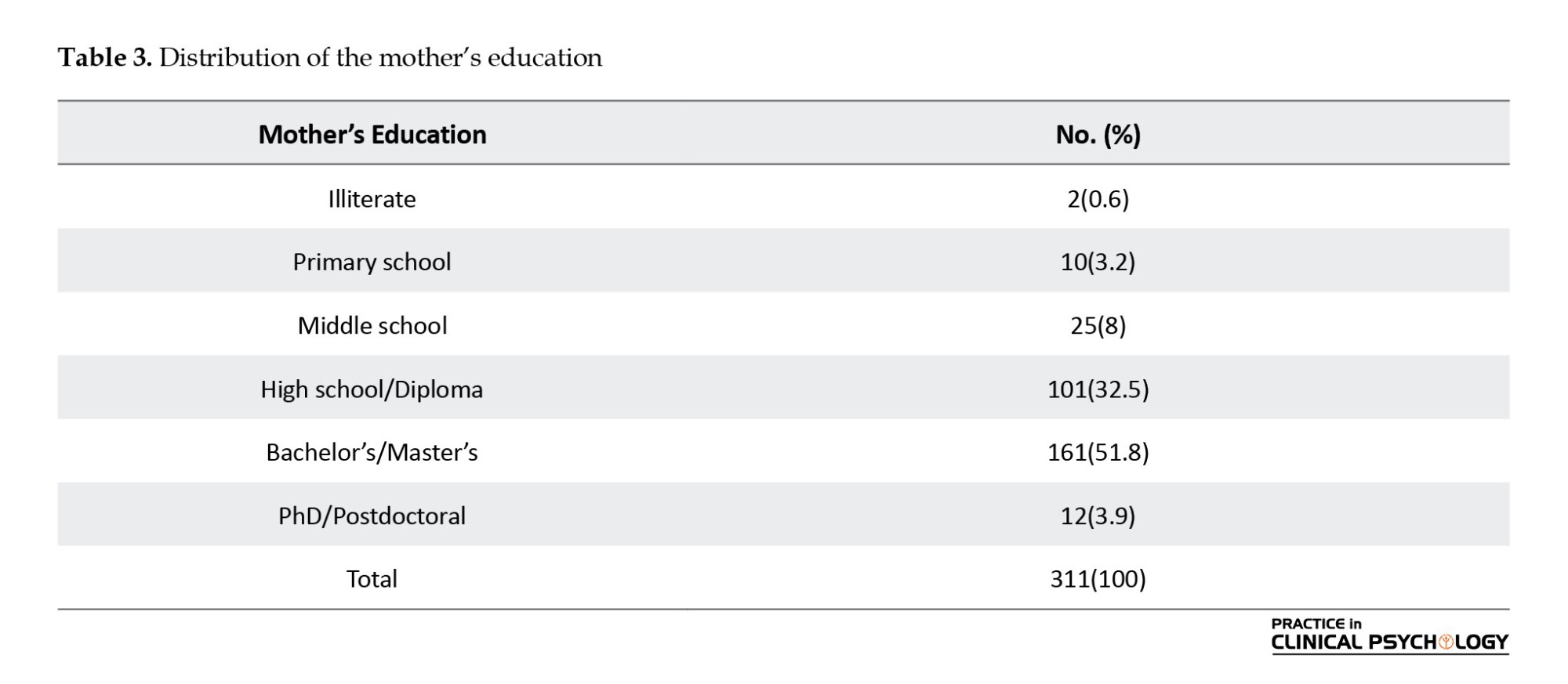

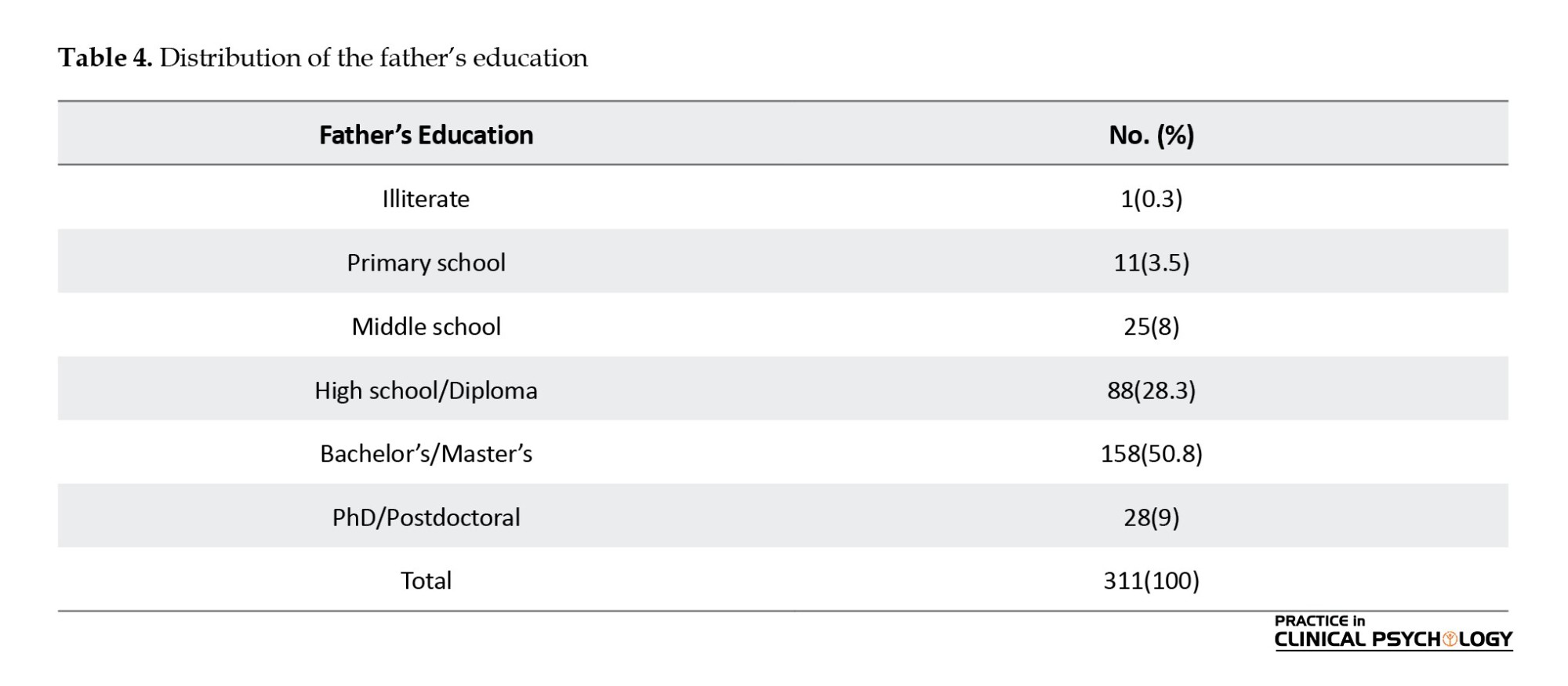

Tables 3 and 4 provide information on the educational background of participants’ parents.

Tables 3 and 4 show that over 80% of parents had higher education than a high school diploma. This finding was considered an indicator of the families’ sociocultural status.

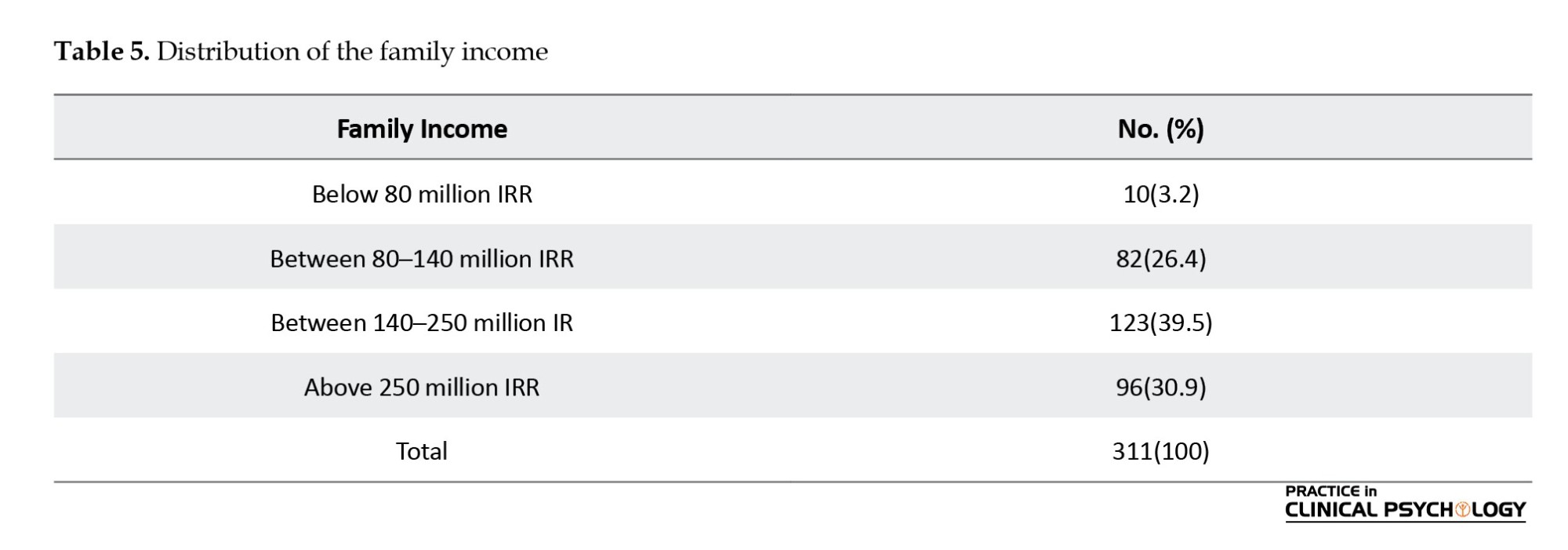

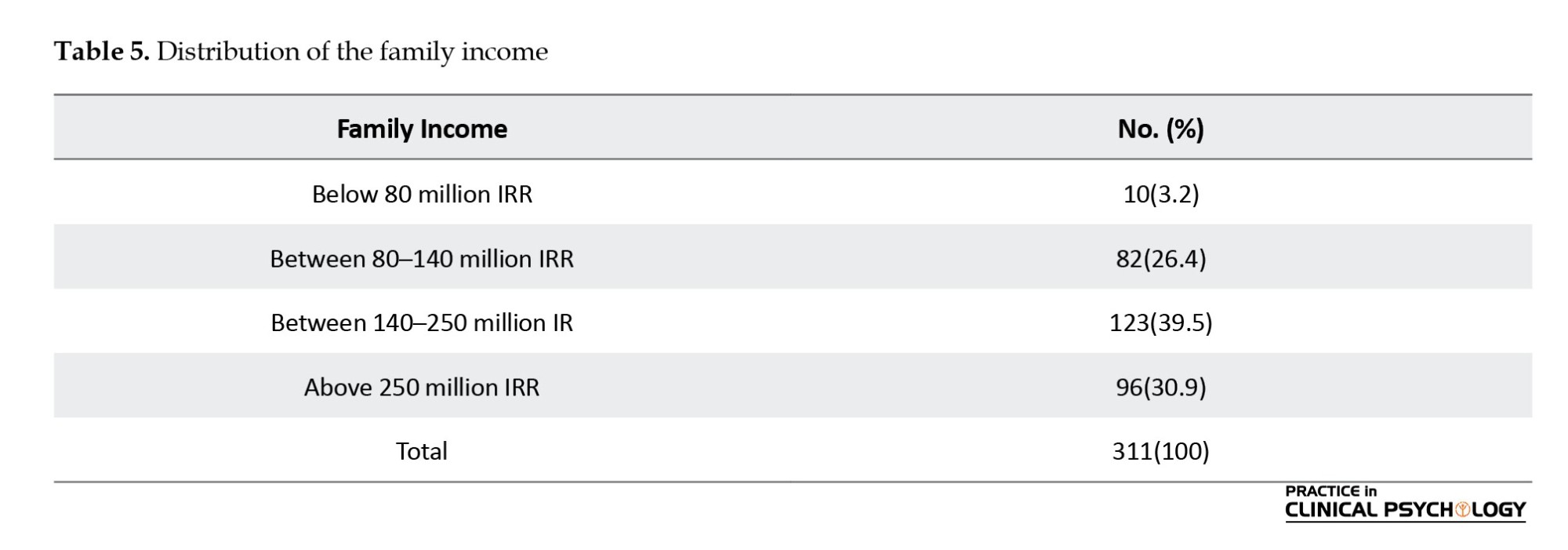

Table 5 presents the family’s monthly income status.

In terms of economic status, the majority of families reported a monthly income exceeding 140 million IRR.

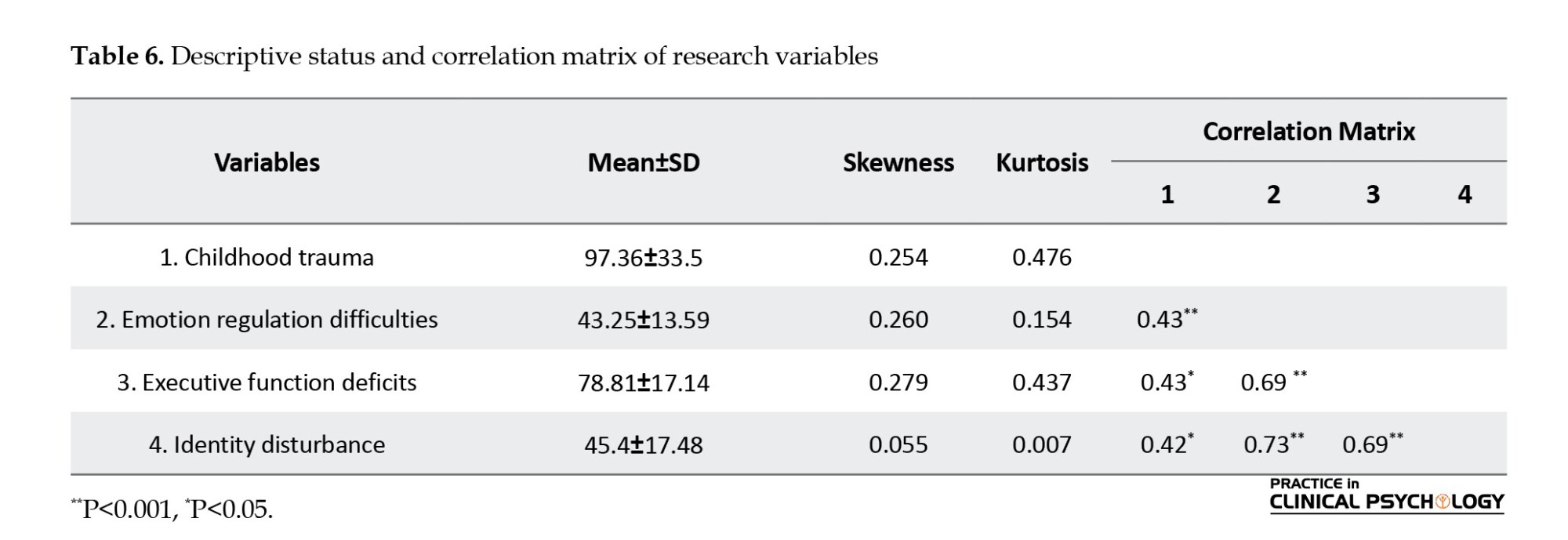

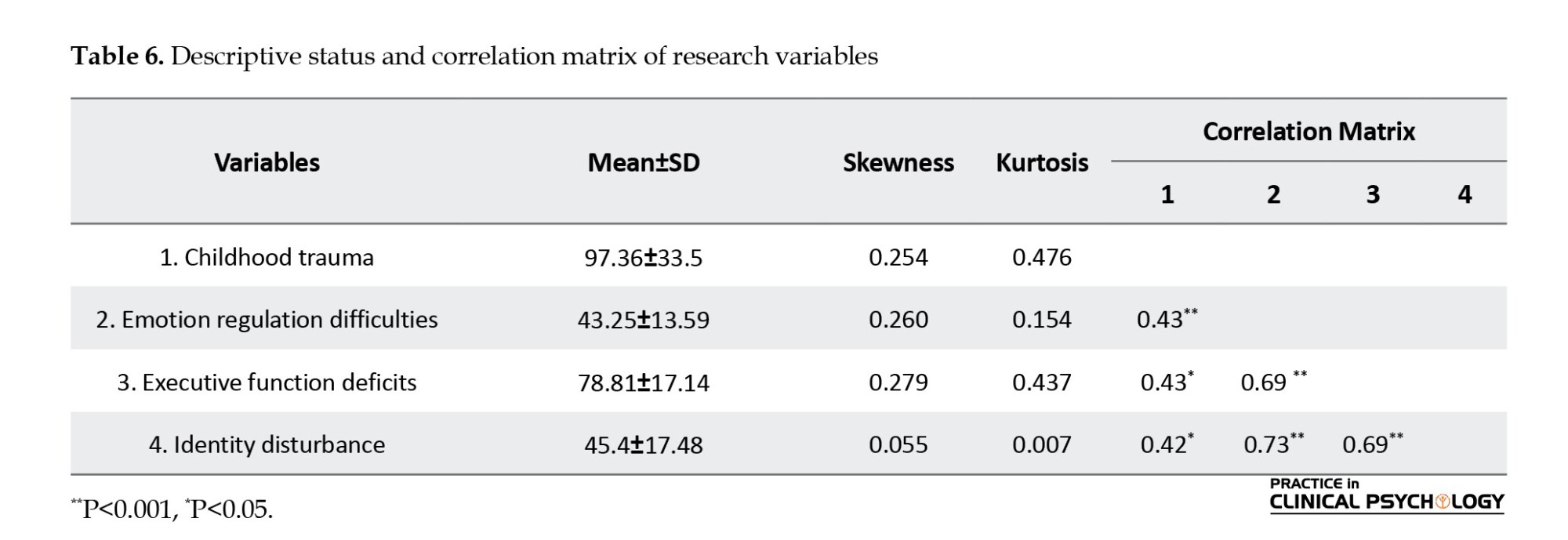

Table 6 presents the descriptive status of the research variables and the correlation matrix between them.

The findings indicate that the assumption of univariate normality for the study variables is met. Examining the correlation matrix for the observed variables (0.413 < r <0.732) in the study model confirmed the absence of multicollinearity. A correlation value higher than 0.85 indicates the presence of multicollinearity issues between variables (Kline, 2023). significant pairwise correlation was observed between all research variables.

The results of Mardia’s test indicated that the assumption of multivariate normality was met in the present study (Mardia’s coefficient=1.26, P>0.05). Outlier detection was conducted at the univariate level and for observed variables using frequency tables and boxplots. Additionally, the Mahalanobis distance was employed to identify multivariate outliers. Based on the results, data from 15 participants were excluded from structural equation modeling.

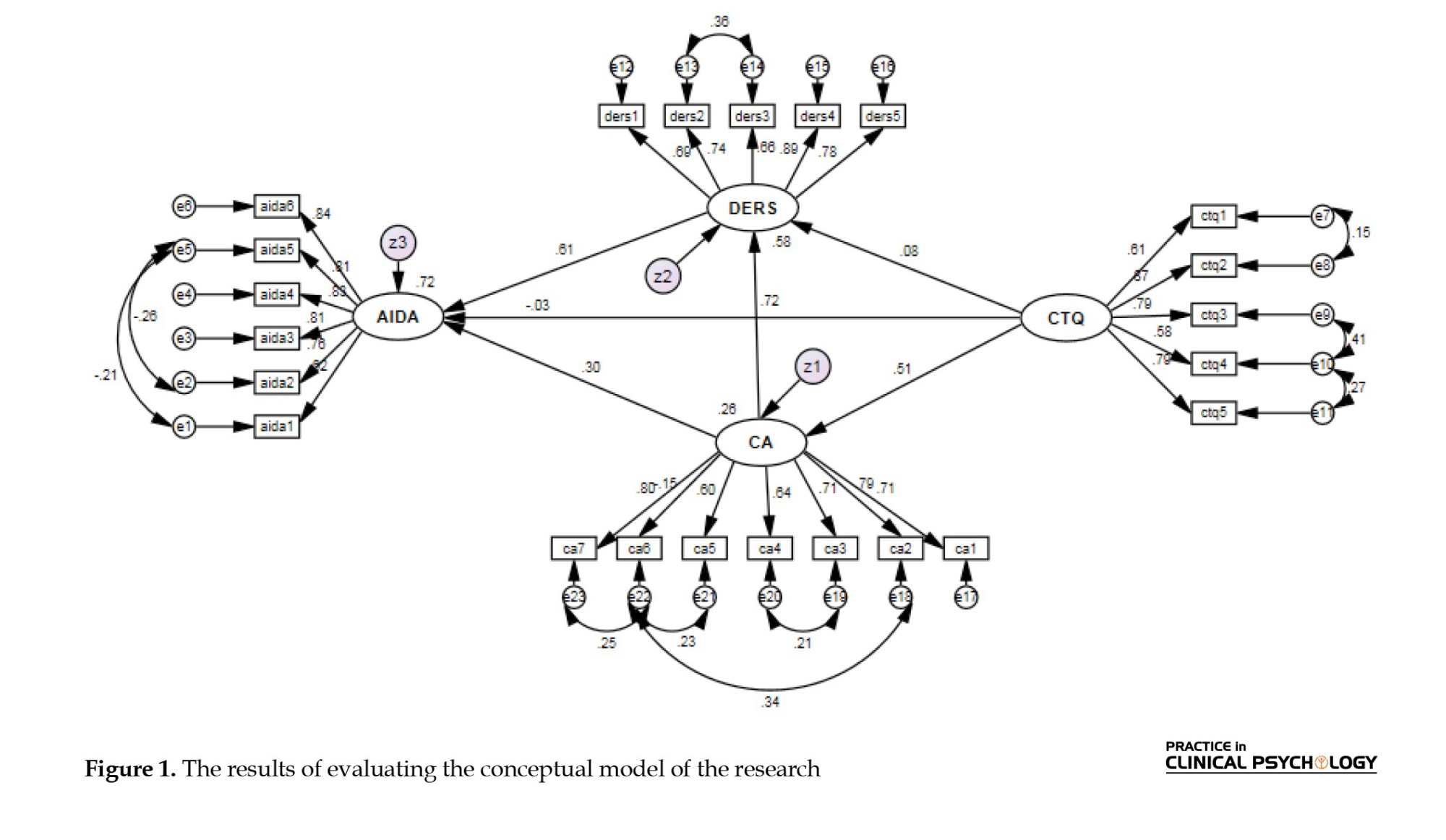

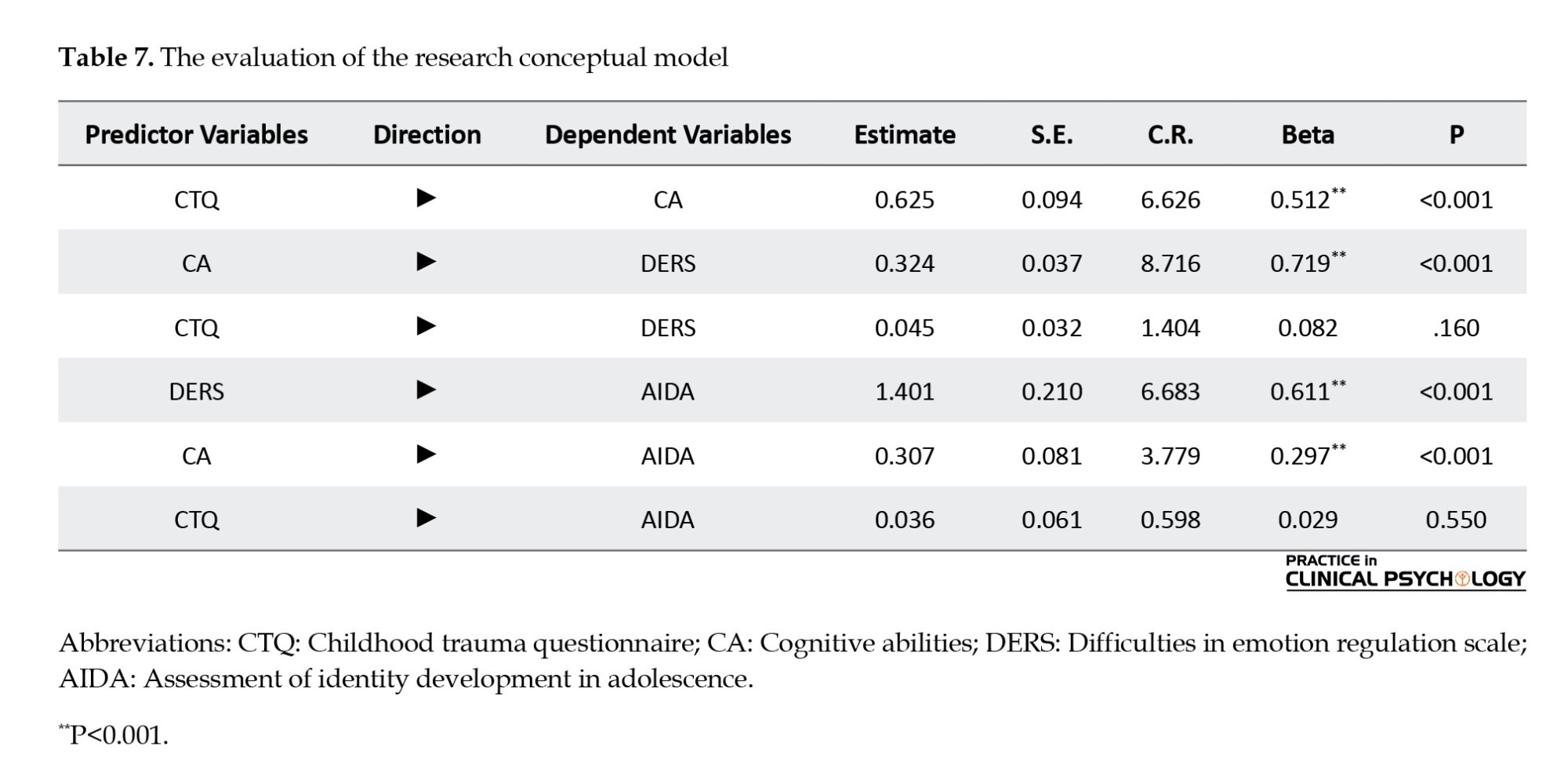

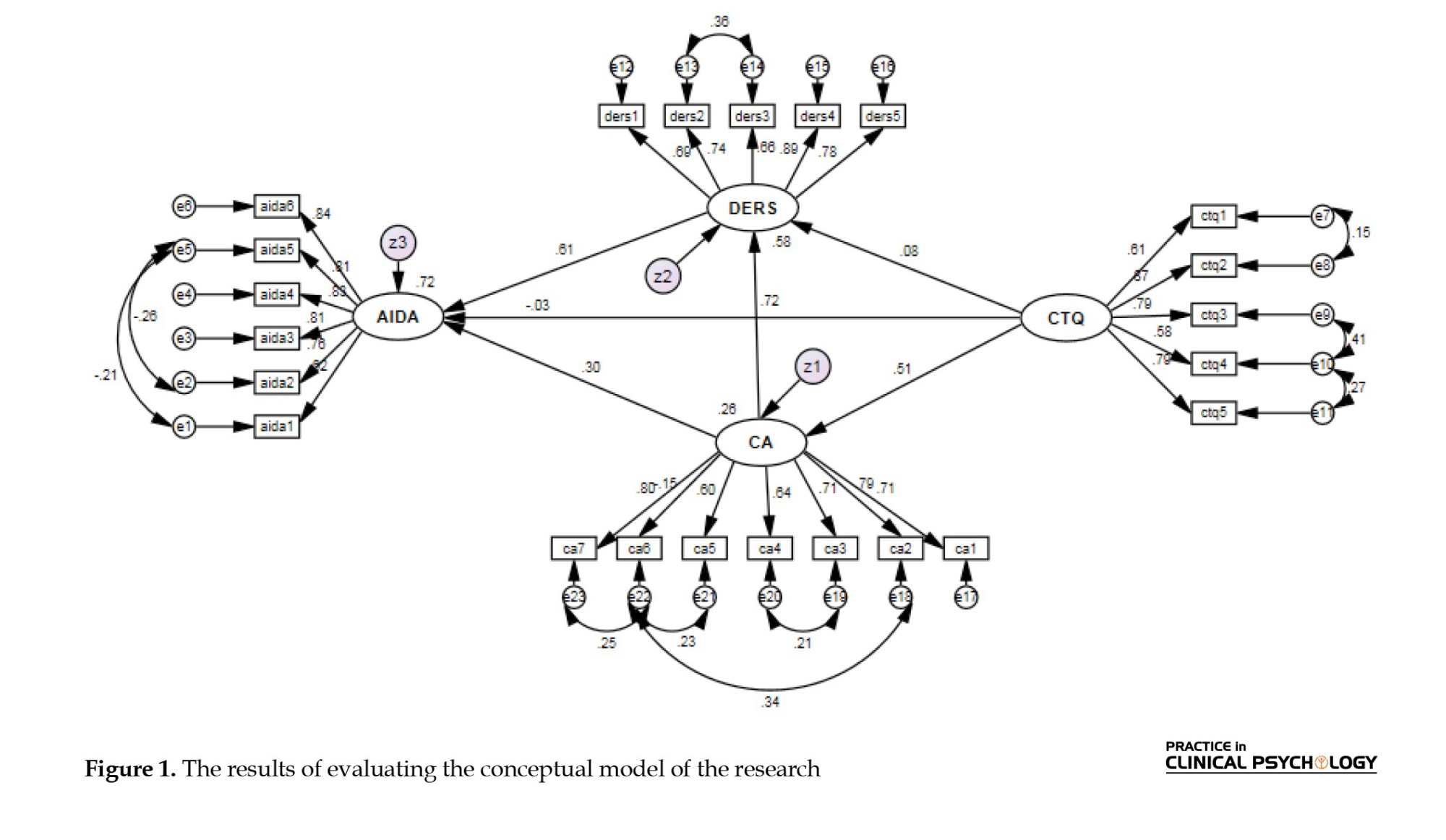

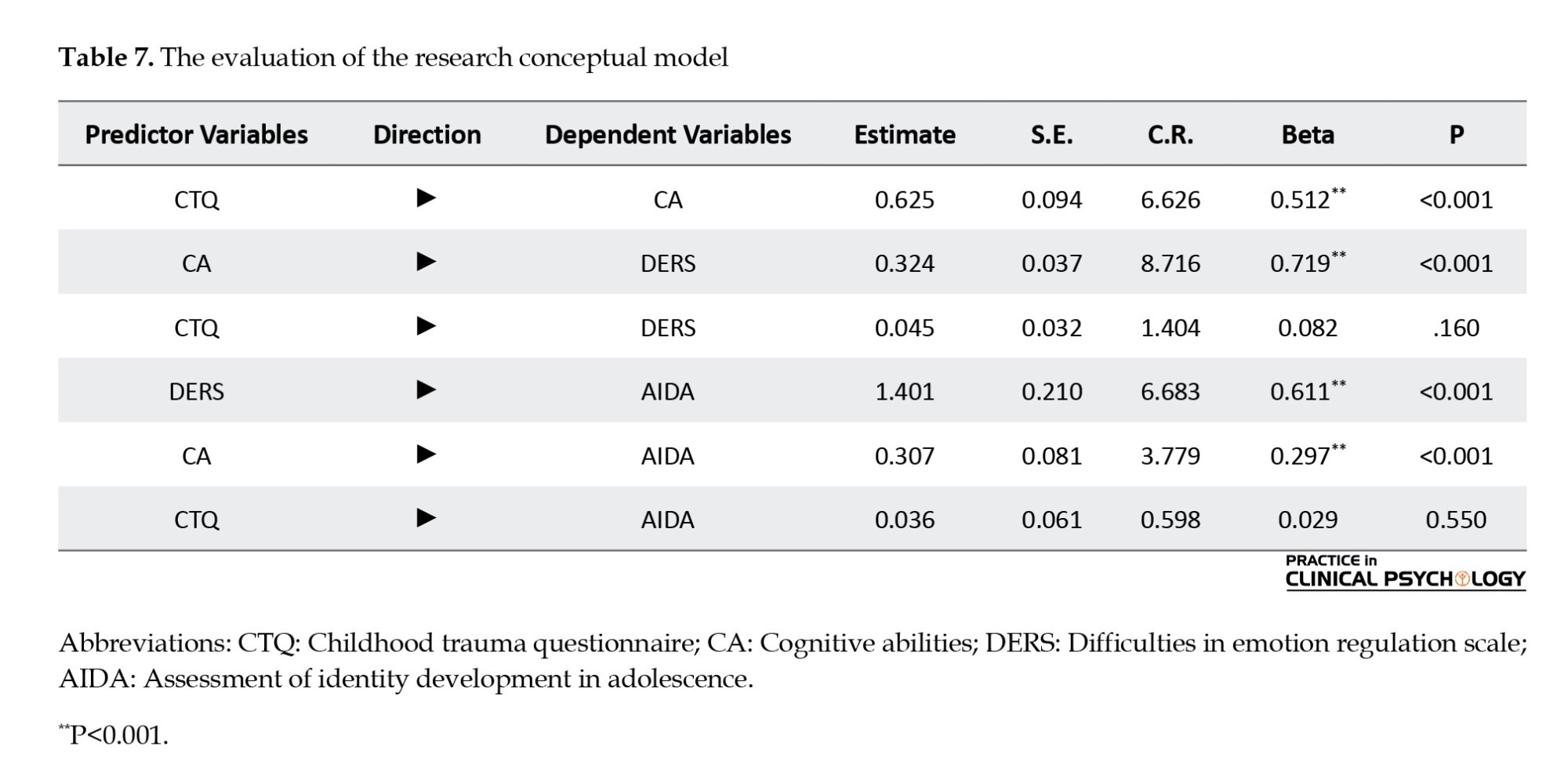

The model evaluation results are presented in Figure 1 and Table 7, meeting the assumptions of structural equation modeling.

Table 7 indicates significant relationships between childhood trauma (CTQ) and executive function deficits (CA), between executive function deficits and both emotion regulation difficulties (DERS) and identity disturbance (AIDA) and between emotion regulation difficulties and identity disturbance. However, no significant direct relationship was found between childhood trauma and either identity disturbance or emotion regulation difficulties.

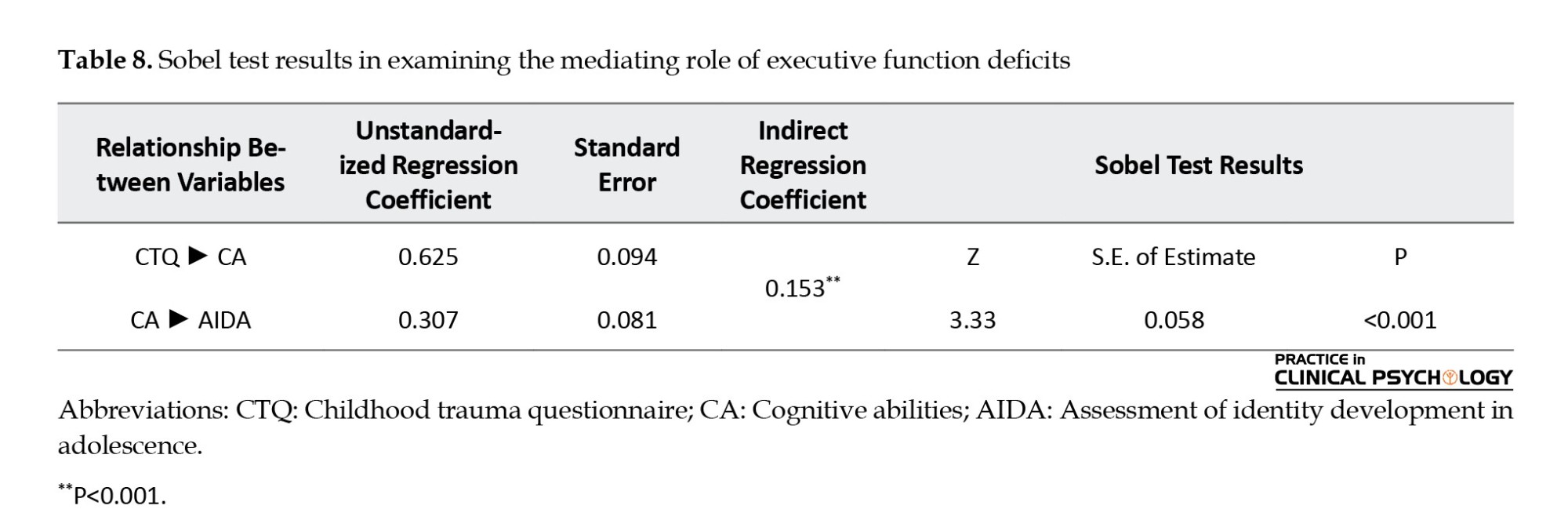

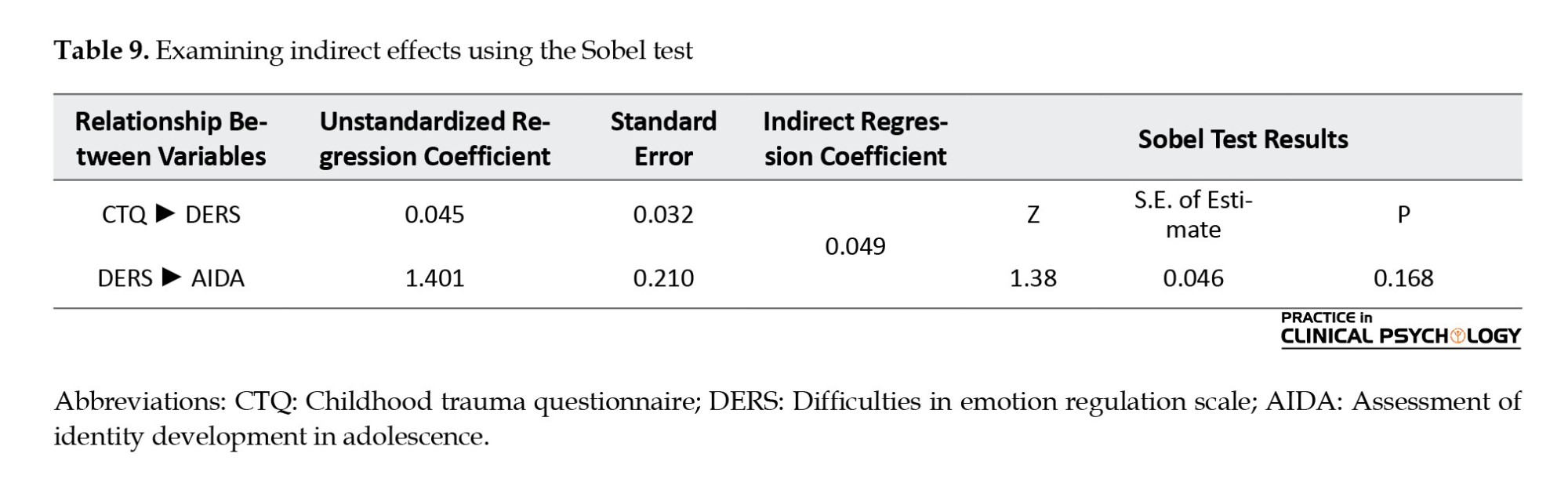

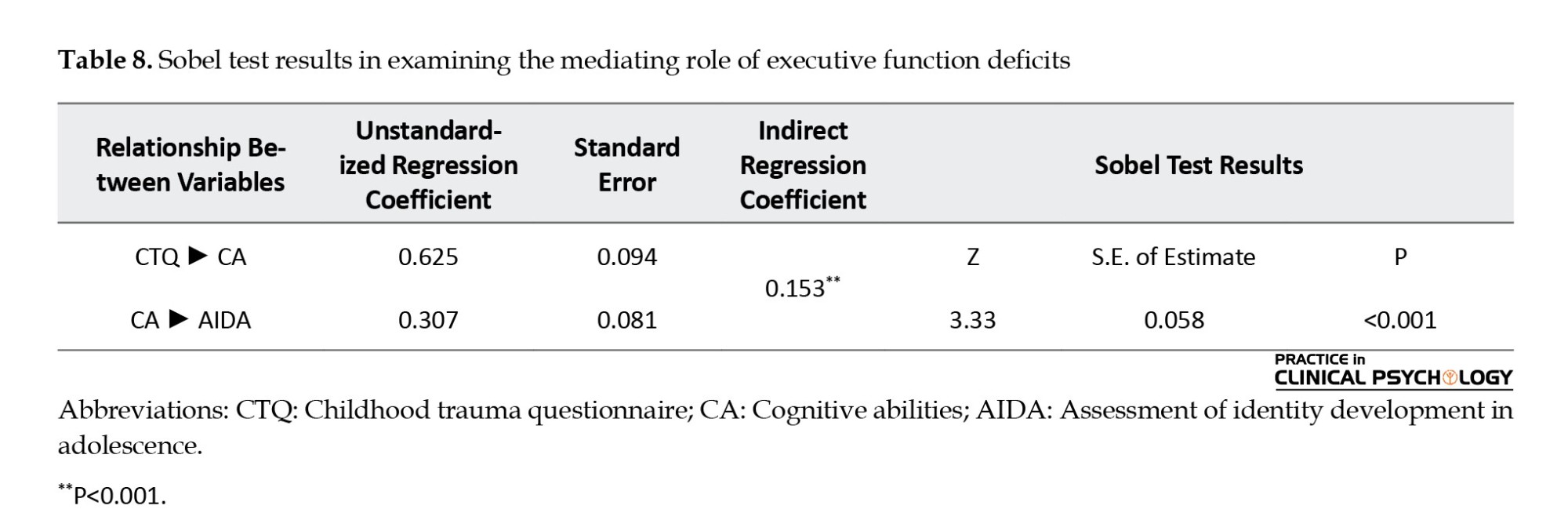

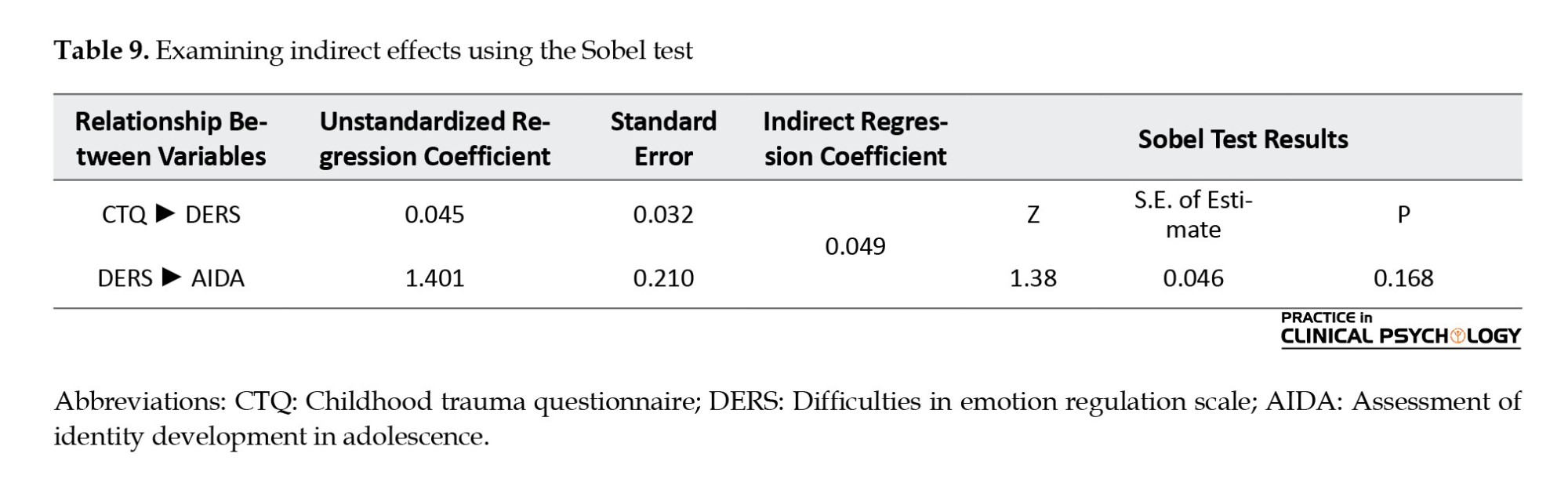

The mediating roles of emotion regulation difficulties and executive function deficits were tested using the Sobel test. The results are presented in Tables 8 and 9.

The findings support the role of executive function deficits in the relation between childhood traumas and identity disturbance.

According to the findings presented in Table 9, the mediating role of difficulty in emotion regulation in the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance was not confirmed.

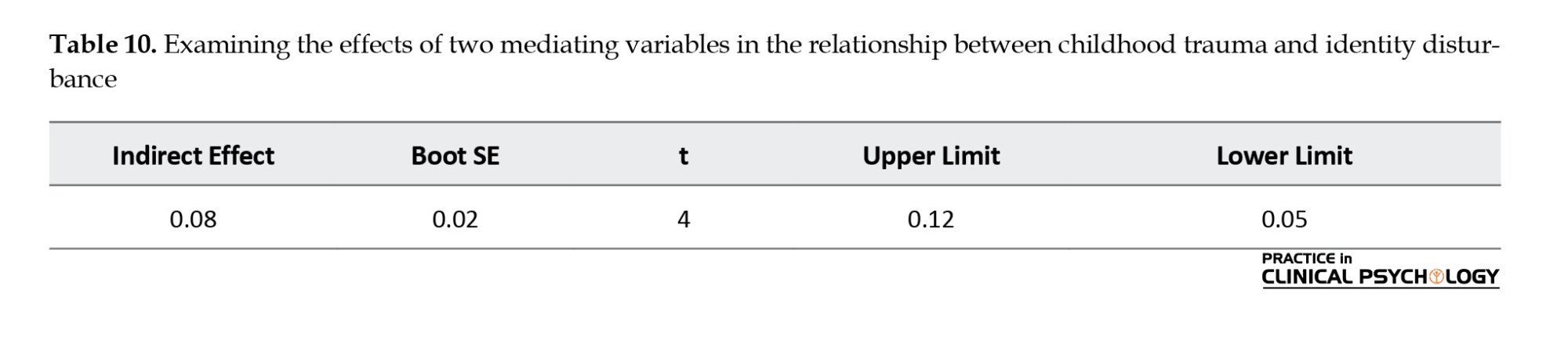

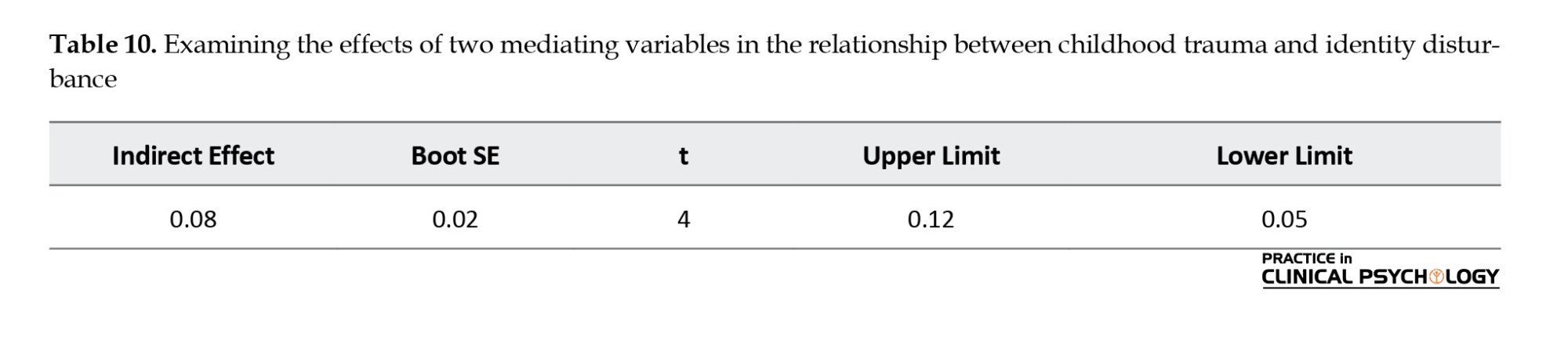

The PROCESS macro (version 4) in SPSS software was utilized to examine the simultaneous effects of two mediating variables in the pathway between childhood trauma and identity disturbance (CTQ → CA → DERS → AIDA). The result of this analysis is presented in Table 10.

Based on the results of Tables 9 and 10, the role of difficulty in emotion regulation as a first-order mediator was not confirmed. Still, its role as a second-order mediator was validated. Considering the non-significance of the relationship between childhood trauma and difficulties in emotion regulation, childhood trauma can impact difficulties in emotion regulation just by influencing deficits in executive function. Consequently, these difficulties in emotion regulation act as a mediator between childhood trauma and identity disturbance.

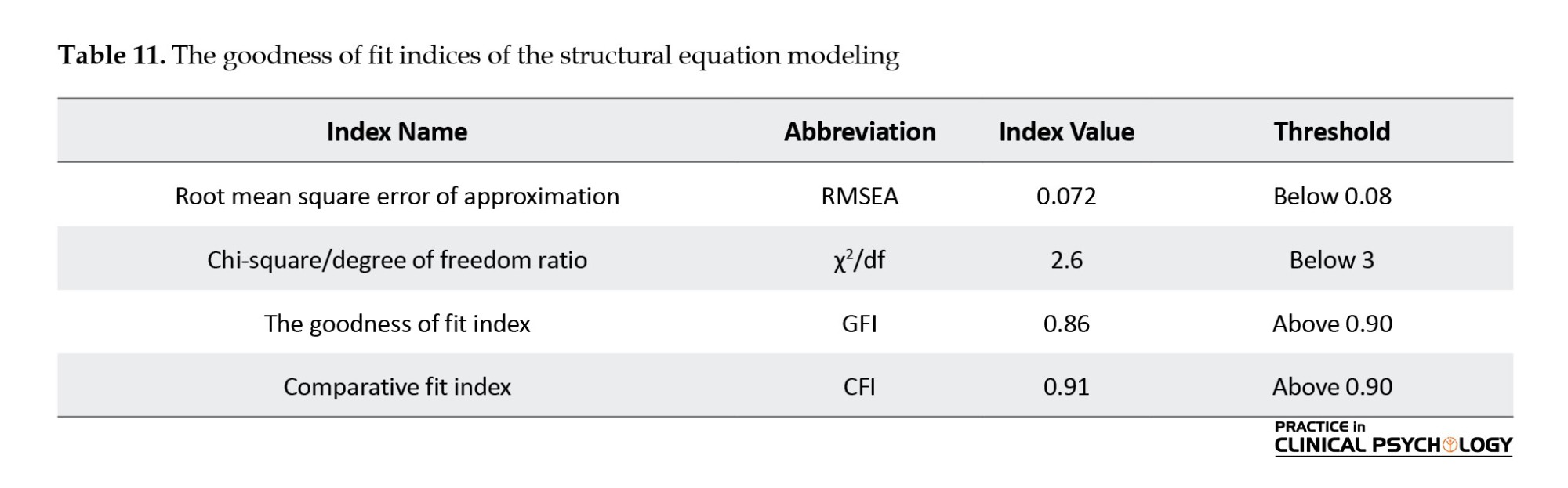

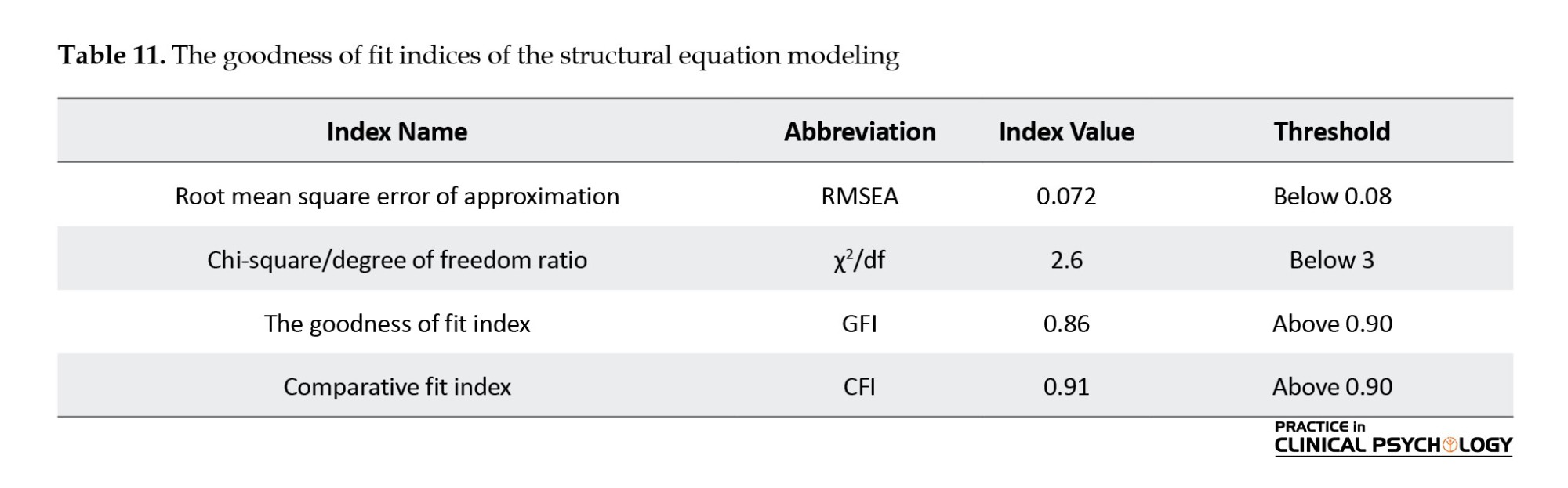

The fit indices of the structural model of the study are presented in Table 11.

The results of the above table indicate that the structural model of this study demonstrates goodness of fit.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the mediating role of difficulty in emotion regulation and executive function deficits in the relation between childhood trauma and identity disturbance in adolescent boys. Regarding the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance, although a significant correlation was found between these two variables consistent with the findings of Dereboy et al., (2018) and Penner et al., (2019), childhood trauma was not a predictor of identity disturbance in adolescence in the final model. This result aligns with the findings of Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene et al., (2020), who highlighted that the severity of experienced trauma and the type of traumatic events could influence the significance of this relationship. Some variables may also moderate this relationship. In the present study, the overall severity of traumatic experiences and the predominant type of these experiences in the sample may have influenced the direct relationship between the two variables. However, consistent with the model proposed by Cicchetti and Lynch (1993), considering the precedence of emotional and cognitive processes over identity formation in the developmental trajectory, the mediation of these processes in the effect of childhood traumatic events on identity disturbance in adolescence, as confirmed in the present model, is justifiable.

Based on the present model, executive function deficits mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance in adolescents. This finding aligns with the results of studies by Pichtel and Pizzagalli (2011), Tottenham et al. (2010), Welsh & Schmitt-Wilson, (2013), and Shalala et al. (2020), which stated that deficits in cognitive functioning often accompany childhood trauma, and these deficits can influence identity disturbance. By affecting the maturation of brain regions involved in executive functions, childhood trauma can account for deficits in these functions. Deficits in executive functions, through failures in tasks and acquiring competencies, lead to a diminished sense of agency, the development of negative feelings and self-judgments, and negative feedback from others, all of which contribute to difficulties in forming a clear understanding of self. Reducing abilities such as critical thinking, self-regulation, and thorough evaluation of options increases reliance on external sources. This status, coupled with a diminished sense of efficacy and personal agency and limited exploration of multiple identity options, disrupts the development of a clear sense of self.

Childhood trauma can impact difficulties in emotion regulation by influencing deficits in executive function. Consequently, these difficulties in emotion regulation act as a mediator between childhood trauma and identity disturbance. These findings align with the results of research conducted by Shalala et al. (2020), Nasiu et al. (2015 ), Derboy et al. (2018), and Paki et al. (2023). Emotion regulation is a form of self-regulatory process, with components of executive functions, such as the executive attention network and working memory, contributing to learning and self-regulatory efforts. Difficulties with emotion regulation lead to an insufficient understanding of oneself, emotions, preferences, and personal experiences. They also create a pattern of excessive dependence on others to resolve emotional crises, obstructing the development of a clear identity (Linehan, 1993). The employment of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies can also significantly impact identity disturbance. For example, a tendency to suppress emotions can result in feelings of numbness, emptiness, and inadequacy, which may contribute to identity disturbance (Linehan, 1993; Kernberg, 1975). Kernberg and Caligor (2005) contended that the prevalence of intense negative emotions and an inability to regulate them effectively might heighten the need to externalize them. Consequently, this leads to an increased reliance on primitive defenses such as projection and splitting, which ultimately disrupts the development of an integrated and coherent representation of oneself and others.

Conclusion

The findings of this research underscore the vital role of executive functions in emotion regulation and identity formation. Based on this, training in emotion regulation skills and activities aimed at enhancing executive functions in children, especially those with traumatic experiences, in schools and educational settings can be effective in preventing and reducing future identity disturbances. Clinicians’ attention to executive functions and emotion regulation when dealing with clients experiencing identity disturbances, especially adolescents with traumatic experiences, can be highly beneficial.

Study limitations

The current research limitations include using a convenience sampling method, the unavailability of the short form of the adolescent identity development assessment questionnaire, and the large number of questions, which led to fatigue and decreased response accuracy. Furthermore, the assessment of cognitive abilities and childhood trauma was conducted using self-report tools, which may have influenced the reliability of the information. It is suggested that, due to the absence of empirical evidence concerning the relations between dimensions of executive functions and identity disturbance, as well as the effects of various dimensions and severity levels of childhood trauma on identity disturbance, these pathways should be explored using alternative tools. This study was conducted on a general population, so this model should be tested within clinical populations. Furthermore, due to the limitations in generalizing the findings to other age and gender groups, examining this model in those groups is also recommended. It is advisable to explore the clinical effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation and emotion regulation training in preventing and alleviating identity disturbance among adolescents in both the general population and those with traumatic experiences.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1403.032).

Funding

This research was derived from the master’s thesis of Alireza Fallah Tafti, approved by the Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to the Department of Education of Yazd City and all the parents and adolescents who assisted us in collecting the data for this research.

References

The essential task of adolescence and the most crucial aspect of human psychosocial development is establishing a stable and cohesive identity (Erikson, 1968). Identity disturbance, the pathological aspect of identity development, refers to a persistent and marked instability in an individual’s self-concept. It is characterized by a diminished capacity to define oneself, commit to values, goals, or relationships, and a distressing sense of incoherence (Lowe, 2017). Identity is associated with a wide range of psychosocial adaptations, and identity disturbance can serve as a transdiagnostic marker for psychopathology (Kaufman et al., 2014; Neacsiu et al., 2015; Hatano et al., 2018; Meeus et al., 2018). Given identity’s significance during adolescence and its maladaptive development’s negative consequences, identifying the factors influencing identity formation is essential.

One of the factors that can affect the development of identity and contribute to identity disturbance is childhood trauma (Dereboy et al., 2018). The term “childhood trauma” is defined as a broad, inclusive concept encompassing a range of adverse experiences occurring before the age of 18, including emotional and physical abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse (Back et al., 2021). Maltreatment is considered a significant public health concern. A review study reported the prevalence of physical abuse up to 58.2%, emotional abuse up to 91.6%, and neglect up to 85.3% among Iranian children, highlighting a critical situation that demands urgent attention (Salehian & Maleki- Saghooni, 2021). Although various studies have generally suggested a link between childhood trauma and identity development (Dereboy et al., 2018; Penner et al., 2019), the underlying mechanisms of this relationship have not been extensively explored. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms is essential for realizing the full potential of identity research in informing clinical practice, therapeutic interventions, and prevention strategies. Researchers in this field argue that one of the main reasons for this gap is a disconnection between developmental and clinical literature (Kaufman et al., 2014; Pasupathi, 2014; Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene et al., 2020).

According to the ecological-transactional model (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), from a developmental perspective, the formation of developmental milestones at each stage is built upon the healthy progression of previous stages. Childhood trauma can disrupt this trajectory, diverting individuals from a healthy developmental path at all critical milestones. Identity formation is fundamentally a cognitive and emotional process (Hatano et al., 2022). Given the temporal precedence of cognitive and emotional development over identity formation in the developmental process, childhood trauma can contribute to pathological identity development in adolescence by impairing cognitive and emotional processes.

One of the key cognitive variables is executive functions. Executive functions are neurocognitive skills supporting top-down, conscious control of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. They are essential for reasoning, goal-directed actions, emotion regulation, and complex social functioning. Additionally, they enable self-regulation learning and adaptation to changing circumstances (Diamond, 2013; Zelazo, 2015). Studies have shown that childhood trauma can have a detrimental impact on the development of executive functions, which is crucial for effective cognitive processing and self-regulation (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011). There is limited empirical evidence regarding the relationship between executive function deficits and identity disturbance. Nevertheless, it has been generally suggested that individuals with executive function impairments are more likely to experience identity disturbance. Furthermore, research indicates that developing executive functions is a prerequisite for identity formation (Shallala et al., 2020; Welsh & Schmitt-Wilson, 2013).

Emotion regulation is one of the processes that influence identity development and can be affected by childhood trauma. Emotion regulation consists of determining when and how emotions are experienced, how they change over time, and ultimately how they are expressed (Gross, 2013). Children who have experienced maltreatment exhibit significant difficulties in emotion regulation, emotional expression, and emotional recognition. Childhood maltreatment is considered a “critical threat” to the optimal development of emotional processing abilities (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). Moreover, substantial research has shown that challenges in emotion regulation predict identity disturbances in both clinical and non-clinical populations, as well as across a wide range of psychological disorders (Gratz et al., 2015; Neacsiu et al., 2014; Stepp et al., 2014).

Overall, previous studies have indicated associations among the variables examined in the present study. To the best of our knowledge, no research has investigated the combined impact of these variables. Given the necessity of further understanding the mechanisms and factors influencing identity development and their application in preventive and therapeutic interventions, the present study adopted a developmental-clinical perspective to examine the impact of childhood trauma on identity disturbance in adolescents, mediated by emotion regulation difficulties and executive function deficits.

Materials and Methods

The present study used a descriptive-cross-sectional design and structural equation modeling methodology. The study population consisted of 16- to 18-year-old adolescent boys. Of whom the target sample was selected through convenience and purposive sampling from students in various districts of Yazd City, Iran. Ultimately, data from 311 participants were included in the analysis. The inclusion criteria comprised male gender, being within the age range of 16 to 18 years, and willingness to participate voluntarily in the study. Participants with cognitive or neurodevelopmental disorders that impair cognitive abilities (CAs), severe psychiatric disorders, or substance use disorders were excluded from the study. This exclusion was initially based on self-report and subsequently confirmed through a clinical interview following diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) criteria. The exclusion criteria also included failure to respond to the questionnaire and desire to withdraw from the study.

Study instruments

Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ)

The CTQ is a self-report questionnaire developed by Bernstein et al. (Bernstein et al., 2003) to assess childhood adversity and trauma. Five subscales of CTQ evaluate these dimensions of childhood traumas: Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, emotional, and physical neglect. It consists of 28 items. Twenty-five items measure the core components of maltreatment, and three items can identify individuals who may be underestimating or denying their childhood traumas. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with scores for each subscale ranging from 5 to 25 and the total questionnaire score ranging from 25 to 125. Higher scores indicate a greater level of childhood trauma. Bernstein et al., (2003) reported that Cronbach α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.78 to 0.95. In Iran, reliability coefficients for the five subscales have been reported between 0.81 and 0.98 (Ebrahimi et al., 2014).

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale-short form (DERS-16)

Bjureberg et al. developed DERS-16 questionnaire (Bjureberg et al., 2016). The DERS-16 is a 16-item self-report tool that assesses five key aspects of difficulties in emotion regulation difficulties. It represents several challenges related to emotional regulation, including lack of emotional clarity, difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behavior, trouble controlling impulsive behaviors, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and a tendency not to accept emotional responses. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 16 to 96. Individuals who have greater difficulties in regulating emotions will get higher scores. Yigit and Yigit (2019) reported the Cronbach α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.78 to 0.92. In Iran, reliability coefficients have been reported to range from 0.68 to 0.77 (Fallahi et al., 2021).

Cognitive abilities (CA) questionnaire

Nejati developed CA, a 30-item self-report questionnaire (Nejati, 2013), to assess cognitive abilities. The questionnaire evaluates various cognitive functions, including memory, inhibitory control and selective attention, decision-making, planning, sustained attention, social cognition, and cognitive flexibility. Scoring is based on a Likert scale; the total score ranges from 30 to 150. Higher scores indicate greater deficits in cognitive abilities. The Cronbach α coefficient, as reported by its developer, is 0.83.

Assessment of identity development in adolescence (AIDA)

Goth et al. (2012) developed this self-report AIDA to assess identity development in terms of psychopathology in personality functioning among adolescents aged 12 to 18. The AIDA consists of 58 items and includes a total score indicating identity integration vs identity diffusion, two main dimensions (continuity vs discontinuity and coherence vs incoherence), and six subscales. Scoring is based on a Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 0 to 232. The total score reflects identity diffusion; higher scores indicate greater identity impairment and an increased risk of personality disorders. Goth et al. (2012) reported the Cronbach α reliability coefficient as 0.94 for the overall scale, 0.87 and 0.92 for the two dimensions, and between 0.69 and 0.84 for the subscales. In Iran, the Cronbach α was reported as 0.95 for the overall scale, 0.89 and 0.92 for the two dimensions, and between 0.70 and 0.84 for the subscales.

Study procedure

After obtaining official approval and an execution permit from the Yazd Provincial Department of Education and securing an ethical code, the researchers visited three schools in Yazd selected by the Department of Education. Informed consent forms for participation in the study were distributed among students to be signed by their guardians. The questionnaires were distributed individually in a paper-and-pencil format among participants who met the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 400 questionnaires were collected. After excluding those that met the invalidity criteria in the CTQ and AIDA questionnaires, as well as incomplete or distorted responses, data from 311 participants were selected for analysis using SPSS software, version 27 and AMOS software, version 24.

Results

The age distribution of the participants in the study is presented in Table 1.

The majority of participants in the study belonged to the 17-year-old age group, with the mean age of participants being 16.95 years.

Table 2 presents the distribution of participants based on their grade level.

According to the results of the Table 2, most participants were studying in the 11th, 10th, and 12th grades, in that order.

Tables 3 and 4 provide information on the educational background of participants’ parents.

Tables 3 and 4 show that over 80% of parents had higher education than a high school diploma. This finding was considered an indicator of the families’ sociocultural status.

Table 5 presents the family’s monthly income status.

In terms of economic status, the majority of families reported a monthly income exceeding 140 million IRR.

Table 6 presents the descriptive status of the research variables and the correlation matrix between them.

The findings indicate that the assumption of univariate normality for the study variables is met. Examining the correlation matrix for the observed variables (0.413 < r <0.732) in the study model confirmed the absence of multicollinearity. A correlation value higher than 0.85 indicates the presence of multicollinearity issues between variables (Kline, 2023). significant pairwise correlation was observed between all research variables.

The results of Mardia’s test indicated that the assumption of multivariate normality was met in the present study (Mardia’s coefficient=1.26, P>0.05). Outlier detection was conducted at the univariate level and for observed variables using frequency tables and boxplots. Additionally, the Mahalanobis distance was employed to identify multivariate outliers. Based on the results, data from 15 participants were excluded from structural equation modeling.

The model evaluation results are presented in Figure 1 and Table 7, meeting the assumptions of structural equation modeling.

Table 7 indicates significant relationships between childhood trauma (CTQ) and executive function deficits (CA), between executive function deficits and both emotion regulation difficulties (DERS) and identity disturbance (AIDA) and between emotion regulation difficulties and identity disturbance. However, no significant direct relationship was found between childhood trauma and either identity disturbance or emotion regulation difficulties.

The mediating roles of emotion regulation difficulties and executive function deficits were tested using the Sobel test. The results are presented in Tables 8 and 9.

The findings support the role of executive function deficits in the relation between childhood traumas and identity disturbance.

According to the findings presented in Table 9, the mediating role of difficulty in emotion regulation in the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance was not confirmed.

The PROCESS macro (version 4) in SPSS software was utilized to examine the simultaneous effects of two mediating variables in the pathway between childhood trauma and identity disturbance (CTQ → CA → DERS → AIDA). The result of this analysis is presented in Table 10.

Based on the results of Tables 9 and 10, the role of difficulty in emotion regulation as a first-order mediator was not confirmed. Still, its role as a second-order mediator was validated. Considering the non-significance of the relationship between childhood trauma and difficulties in emotion regulation, childhood trauma can impact difficulties in emotion regulation just by influencing deficits in executive function. Consequently, these difficulties in emotion regulation act as a mediator between childhood trauma and identity disturbance.

The fit indices of the structural model of the study are presented in Table 11.

The results of the above table indicate that the structural model of this study demonstrates goodness of fit.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the mediating role of difficulty in emotion regulation and executive function deficits in the relation between childhood trauma and identity disturbance in adolescent boys. Regarding the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance, although a significant correlation was found between these two variables consistent with the findings of Dereboy et al., (2018) and Penner et al., (2019), childhood trauma was not a predictor of identity disturbance in adolescence in the final model. This result aligns with the findings of Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene et al., (2020), who highlighted that the severity of experienced trauma and the type of traumatic events could influence the significance of this relationship. Some variables may also moderate this relationship. In the present study, the overall severity of traumatic experiences and the predominant type of these experiences in the sample may have influenced the direct relationship between the two variables. However, consistent with the model proposed by Cicchetti and Lynch (1993), considering the precedence of emotional and cognitive processes over identity formation in the developmental trajectory, the mediation of these processes in the effect of childhood traumatic events on identity disturbance in adolescence, as confirmed in the present model, is justifiable.

Based on the present model, executive function deficits mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and identity disturbance in adolescents. This finding aligns with the results of studies by Pichtel and Pizzagalli (2011), Tottenham et al. (2010), Welsh & Schmitt-Wilson, (2013), and Shalala et al. (2020), which stated that deficits in cognitive functioning often accompany childhood trauma, and these deficits can influence identity disturbance. By affecting the maturation of brain regions involved in executive functions, childhood trauma can account for deficits in these functions. Deficits in executive functions, through failures in tasks and acquiring competencies, lead to a diminished sense of agency, the development of negative feelings and self-judgments, and negative feedback from others, all of which contribute to difficulties in forming a clear understanding of self. Reducing abilities such as critical thinking, self-regulation, and thorough evaluation of options increases reliance on external sources. This status, coupled with a diminished sense of efficacy and personal agency and limited exploration of multiple identity options, disrupts the development of a clear sense of self.

Childhood trauma can impact difficulties in emotion regulation by influencing deficits in executive function. Consequently, these difficulties in emotion regulation act as a mediator between childhood trauma and identity disturbance. These findings align with the results of research conducted by Shalala et al. (2020), Nasiu et al. (2015 ), Derboy et al. (2018), and Paki et al. (2023). Emotion regulation is a form of self-regulatory process, with components of executive functions, such as the executive attention network and working memory, contributing to learning and self-regulatory efforts. Difficulties with emotion regulation lead to an insufficient understanding of oneself, emotions, preferences, and personal experiences. They also create a pattern of excessive dependence on others to resolve emotional crises, obstructing the development of a clear identity (Linehan, 1993). The employment of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies can also significantly impact identity disturbance. For example, a tendency to suppress emotions can result in feelings of numbness, emptiness, and inadequacy, which may contribute to identity disturbance (Linehan, 1993; Kernberg, 1975). Kernberg and Caligor (2005) contended that the prevalence of intense negative emotions and an inability to regulate them effectively might heighten the need to externalize them. Consequently, this leads to an increased reliance on primitive defenses such as projection and splitting, which ultimately disrupts the development of an integrated and coherent representation of oneself and others.

Conclusion

The findings of this research underscore the vital role of executive functions in emotion regulation and identity formation. Based on this, training in emotion regulation skills and activities aimed at enhancing executive functions in children, especially those with traumatic experiences, in schools and educational settings can be effective in preventing and reducing future identity disturbances. Clinicians’ attention to executive functions and emotion regulation when dealing with clients experiencing identity disturbances, especially adolescents with traumatic experiences, can be highly beneficial.

Study limitations

The current research limitations include using a convenience sampling method, the unavailability of the short form of the adolescent identity development assessment questionnaire, and the large number of questions, which led to fatigue and decreased response accuracy. Furthermore, the assessment of cognitive abilities and childhood trauma was conducted using self-report tools, which may have influenced the reliability of the information. It is suggested that, due to the absence of empirical evidence concerning the relations between dimensions of executive functions and identity disturbance, as well as the effects of various dimensions and severity levels of childhood trauma on identity disturbance, these pathways should be explored using alternative tools. This study was conducted on a general population, so this model should be tested within clinical populations. Furthermore, due to the limitations in generalizing the findings to other age and gender groups, examining this model in those groups is also recommended. It is advisable to explore the clinical effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation and emotion regulation training in preventing and alleviating identity disturbance among adolescents in both the general population and those with traumatic experiences.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1403.032).

Funding

This research was derived from the master’s thesis of Alireza Fallah Tafti, approved by the Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to the Department of Education of Yazd City and all the parents and adolescents who assisted us in collecting the data for this research.

References

Back, S. N., Flechsenhar, A., Bertsch, K., & Zettl, M. (2021). Childhood traumatic experiences and dimensional models of personality disorder in DSM-5 and ICD-11: Opportunities and challenges. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(9), 60. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-021-01265-5] [PMID]

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., & Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169-190. [DOI:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0] [PMID]

Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., & Lundh, L. G., et al. (2016). Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284-296. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x] [PMID]

Cicchetti, D., & Lynch, M. (1993). Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry, 56(1), 96-118. [DOI:10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624] [PMID]

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2005). Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 409-438. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029] [PMID]

Dereboy, Ç., Şahin Demirkapı, E., Şakiroğlu, M., & Şafak Öztürk, C. (2018). [The relationship between childhood traumas, identity development, difficulties in emotion regulation, and psychopathology (Turkish)]. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 29(4), 269-278. [DOI:10.5080/u20463] [PMID]

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750] [PMID]

Ebrahimi, H., Dejkam, M., & Saqa-al-Islam, T. (2014). Childhood trauma and suicide attempts in adulthood. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 275-282. [Link]

Fallahi, V., Narimani, M., & Atadokht, A. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Brief Form (DERS-16) in a group of Iranian adolescents. Journal of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, 29(5), 3721-3735. [DOI:10.18502/ssu.v29i5.6772]

Goth, K., Foelsch, P., Schlüter-Müller, S., Birkhölzer, M., Jung, E., & Pick, O., et al. (2012). Assessment of identity development and identity diffusion in adolescence-Theoretical basis and psychometric properties of the self-report questionnaire AIDA. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(1), 27. [DOI:10.1186/1753-2000-6-27] [PMID]

Gratz, K. L., Bardeen, J. R., Levy, R., Dixon-Gordon, K. L., & Tull, M. T. (2015). Mechanisms of change in an emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 65, 29-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.005] [PMID]

Gross, J. J. (2013). Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward. Emotion, 13(3), 359-365. [DOI:10.1037/a0032135] [PMID]

Hatano, K., Luyckx, K., Hihara, S., Sugimura, K., & Becht, A. I. (2022). Daily identity processes and emotions in young adulthood: A five-day daily-diary method. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(9), 1815-1828. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-022-01629-x] [PMID]

Hatano, K., Sugimura, K., & Schwartz, S. J. (2018). Longitudinal links between identity consolidation and psychosocial problems in adolescence: Using bi-factor latent change and cross-lagged effect models. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(4), 717-730. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-017-0785-2] [PMID]

Kaufman, E. A., Montgomery, M. J., & Crowell, S. E. (2014). Identity-related dysfunction: Integrating clinical and developmental perspectives. Identity, 14(4), 297-311. [DOI:10.1080/15283488.2014.944699]

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Lanham: Jason Aronson. [Link]

Kernberg, O. F., & Caligor, E. (2005). A psychoanalytic theory of personality disorders. In M. F. Lenzenweger & J. F. Clarkin (Eds.), Major theories of personality disorder ( pp. 114-156). The New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Lowe, D. (2017). Early childhood and development of a difficult sense of self: Can it hinder good relationships with others? Journal of Social & Psychological Sciences, 10(1), 47. [Link]

Meeus, W., van de Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S. J., & Branje, S. (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescence. Child Development, 81(5), 1565–1581. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01492.x] [PMID]

Neacsiu, A. D., Eberle, J. W., Kramer, R., Wiesmann, T., & Linehan, M. M. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy skills for transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Behavior Research and Therapy, 59(12), 40-51. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.005] [PMID]

Neacsiu, A. D., Herr, N. R., Fang, C. M., Rodriguez, M. A., & Rosenthal, M. Z. (2015). Identity disturbance and problems with emotion regulation are related constructs across diagnoses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 346-361. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22141] [PMID]

Nejati, V. (2013). Cognitive Abilities Questionnaire: Development and evaluation of psychometric properties. Advances in Cognitive Sciences, 15(2), 11-19. [Link]

Paki, F., Yousefi, Z., & Golparvar, M. (2023). The effectiveness of emotion regulation training on strengthening adolescent identity base and family relationships in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies, 4(4), 93-104. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jayps.4.4.10]

Pasupathi, M. (2014). Identity: Commentary: Identity development: Dialogue between normative and pathological developmental approaches. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(1), 113-120. [DOI:10.1521/pedi.2014.28.1.113] [PMID]

Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55-70. [DOI:10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2] [PMID]

Penner, F., Gambin, M., & Sharp, C. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and identity diffusion among inpatient adolescents: The role of reflective function. Journal of Adolescence, 76(1), 65-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.002] [PMID]

Salehian, M., Maleki-Saghooni, N., & karimi, F. Z. (2021). Prevalence of child abuse and its related factors in Iran: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Medicine, 8(2), 69-78. [Link]

Shallala, N., Tan, J., & Biberdzic, M. (2020). The mediating role of identity disturbance in the relationship between emotion dysregulation, executive function deficits, and maladaptive personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 162(1), 110004. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110004]

Stepp, S. D., Scott, L. N., Morse, J. Q., Nolf, K. A., Hallquist, M. N., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2014). Emotion dysregulation as a maintenance factor of borderline personality disorder features. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 657-666. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.11.006] [PMID]

Tottenham, N., Hare, T. A., Quinn, B. T., McCarry, T. W., Nurse, M., & Gilhooly, T., et al. (2010). Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Developmental Science, 13(1), 46-61. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x] [PMID]

Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, I., Brailovskaia, J., Kamite, Y., Petrauskaite, G., Margraf, J., & Kazlauskas, E. (2020). Does trauma shape identity? Exploring the links between lifetime trauma exposure and identity status in emerging adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 570644. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570644] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2025/01/30 | Accepted: 2025/03/1 | Published: 2025/04/1

Received: 2025/01/30 | Accepted: 2025/03/1 | Published: 2025/04/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |