Volume 13, Issue 2 (Spring 2025)

PCP 2025, 13(2): 143-158 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abdi M R, Zabihzadeh A, Rahmani M A. Parental Grief After Child Homicide in Iran: Challenges and Integrated Intervention Development. PCP 2025; 13 (2) :143-158

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-968-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-968-en.html

1- Department of Counseling and Psychology, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling and Psychology, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran. & Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. ,zabihzadeh.a@gmail.com

2- Department of Counseling and Psychology, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran. & Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 573 kb]

(645 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1937 Views)

Full-Text: (553 Views)

Introduction

Grief resulting from the loss of loved ones is one of the most challenging human experiences, leaving profound and sometimes lasting effects on the lives of survivors. Typically, it is expected that children will outlive their parents. The death of a child and the disruption of this natural order of life can completely shatter parents’ hopes and aspirations (Atwood et al., 2023). Amidst this, when a human factor such as homicide plays a role in a child’s death, the parents’ grieving experience becomes significantly more complex and challenging (Boelen et al., 2015). The circumstances of death can lead to psychological issues such as depression, anger, anxiety, and complicated grief in survivors (Mansoori et al., 2020). Studies have shown that sudden and violent deaths, such as homicides, impose significant psychological and emotional challenges on survivors. These reactions, which manifest in different ways for each individual, include anger and a strong desire for revenge (Gollwitzer & Denzler, 2009; Choi & Cho, 2020), feelings of guilt and social stigma (Frei-Landau et al., 2023), entanglement in a lengthy and complex legal process accompanied by significant psychological pressure (Alves-Costa et al., 2023; Kashka & Beard, 1999), feelings of fear and insecurity regarding personal safety and that of loved ones (Eagle, 2020), the breakdown of value systems and beliefs (Varga et al., 2020), the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Choi & Cho, 2020), withdrawal, isolation, and decreased social interactions (Berrozpe et al., 2024), feelings of injustice (Champion & Kilcullen, 2023; Hava, 2024; Huggins & Hinkson, 2022), disruption of communication and family patterns (Costa et al., 2017), and the loss of privacy (Armour, 2007).

Although complicated grief is recognized as a disorder in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), it remains an emerging topic that requires further research in psychology. A review of the literature on homicide-related grief reveals that studies explicitly focusing on the lived experience of parents grieving the murder of their child are limited. Furthermore, among the few studies conducted, no research has been carried out in Iran on this issue. In addition, the model of complicated grief is deeply culture-dependent, and it may differ for each country based on its unique cultural characteristics (Silverman et al., 2021). Moreover, previous research indicates that grief resulting from homicide is not only dependent on an individual’s internal factors but also influenced by the judicial system and criminal justice practices in the societies where the grief occurs (Kashka & Beard, 1999). In addition, the absence of a standardized intervention for homicide survivors has led many therapists to rely on conventional therapeutic approaches, such as interventions designed explicitly for anxiety, depression, PTSD, and psychosomatic symptoms, which were initially developed for other psychological conditions (Feigelman et al., 2011). Although the effectiveness of some specialized interventions, such as restorative recounting, teaching coping strategies, sharing emotions, addressing PTSD symptoms, and anger management (Salloum et al., 2001), has been examined in previous studies, it seems that developing an integrated intervention that considers the specific needs of this group of survivors while taking into account the social and judicial context of Iranian society, could have a significant impact on the more effective implementation of therapeutic interventions. This factor would play a crucial role in facilitating their psychological and emotional recovery process. Considering these points and taking into account the social and judicial differences between Iranian society and other global communities, which may lead to a distinct experience and perception of homicide grief among Iranian bereaved parents, the importance of this study becomes even more evident. This research could enhance our understanding of this type of loss and provide a foundation for developing an effective intervention to assist this group of survivors.

Furthermore, considering the high prevalence of violent crimes, such as homicide in Iran, and their long-term effects on survivors, a thorough understanding of homicide-related grief is crucial. This understanding can help us better address the needs and challenges of this group of survivors and design more specialized and effective therapeutic interventions for them. Additionally, the findings of this study could be valuable for counselors and psychologists working with this group in judicial environments, assisting them in providing better support. The present study will be conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the researcher aims to understand the nature of grief experienced by parents who have lost their children due to homicide and to identify the specific issues and challenges these parents face during the grieving process. The question is: What are the emotions, issues, and specific problems experienced by parents who have lost their child to homicide about this loss?

In the second phase, based on the qualitative analysis of the findings from the first phase and integrating them with the results of previous studies in this area, a specialized intervention for homicide-related grief will be designed and proposed. This intervention, developed using an integrated approach, will address the crucial key themes when working with these parents. Finally, the content validity of this intervention will be assessed by a group of psychologists with clinical experience in grief counseling. Therefore, two questions will be addressed in the second phase:

What factors should be considered when designing an integrated intervention for homicide-related grief for parents who have lost their child due to homicide?

Does this integrated intervention possess the necessary content validity for grieving parents who have lost their child to homicide?

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study was conducted using a phenomenological approach and a qualitative methodology, with its epistemological foundation rooted in the philosophical assumptions of Edmund Husserl. By emphasizing an impartial understanding of participants’ unique perspectives regarding their experiences, descriptive phenomenology facilitates an authentic comprehension of phenomena by suspending the researcher’s preconceptions and prior beliefs (Abraham & Padmakumari, 2024). This bracketing of preconceptions enables the researcher to analyze individuals’ experiences in a pure form, untainted by presuppositions, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the phenomena under investigation (Chan et al., 2013). In line with this principle, the present study refrained from imposing the researcher’s biases onto the participants’ grief narratives to achieve a more genuine insight into their experiences. As a result, the research paradigm of this study is based on descriptive phenomenology, as the nature of the research questions requires a thorough exploration of the lived experiences of parents who have lost their children to homicide. Participants were asked to articulate their abstract descriptions of grief resulting from homicide by drawing upon concrete and tangible examples derived from their personal experiences following such a loss.

Statistical population

The study population consisted of all bereaved parents who had lost a child due to intentional homicide.

Sample and sampling

The sample comprised 13 mothers and fathers who had lost a child to intentional homicide between 2017 and 2022 and had either been previously involved in related judicial processes or remained engaged in such processes at the time of this research. Participants were selected through purposive sampling from judicial courts in Gilan Province, Iran. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: Possessing a minimum level of cognitive literacy to participate in interviews, at least one year has elapsed since the death of the deceased, willingness to share personal experiences, meeting the diagnostic criteria for prolonged grief disorder as outlined in the DSM-5, and scoring above 25 on the inventory of complicated grief by Prigerson et al. (1995). The exclusion criteria included withdrawal from participation, the emergence of psychological or physical issues during the study, inability to engage in interviews, and significant life changes that prevented participation. The criterion of data saturation was employed to determine the sample size. Theoretical saturation in this study was achieved after the ninth interview; however, to ensure robustness, the interview process continued until the thirteenth participant, when data saturation was confirmed.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, which commenced with open-ended questions and progressively focused on the participants’ experiences of grief following the homicide of their child. Each interview began with an open-ended question: “Please tell me about yourself, your family, and your deceased child?” Subsequently, probing questions like, “Could you elaborate further on this?” were employed to gain deeper insight into the participants’ lived experiences. To gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences, clarifying questions like “Can you give an example of that?” or “What did you mean when you said…?” were asked. The article’s first author conducted all the interviews, each lasting between 60 and 90 minutes. To ensure confidentiality, the interviews took place in a private setting. With the participants’ consent, all conversations were audio-recorded and transcribed word for word. Participants were assigned a unique code to protect their privacy and maintain anonymity.

Study procedure

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch, on February 12, 2024. All necessary legal permits were secured to carry out the research, and coordination was established with the Social Crime Prevention Department of the Gilan Judiciary. A list of homicide cases from 2016 to 2022 in Gilan Province courts was compiled, and after reviewing the key details, 36 cases that met the initial criteria were selected. Following discussions with the judges and an explanation of the research goals, the researcher contacted the victims’ families, inviting those willing to provide their initial consent. In certain instances, the defense attorneys of the grieving families were contacted to inform them of the study’s objectives and invite interested parties to contact the researcher. Ultimately, 23 parents expressed their willingness to participate. After obtaining written informed consent, the data collection process, which included interviews, was initiated.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Colaizzi’s seven-step method. This method closely aligns with Husserl’s perspective and descriptive phenomenology (Wirihana et al., 2018). In this approach, the researchers actively work to set aside their assumptions, focusing on the participants’ experiences as they indeed are, without adding personal interpretations or biases. This deed reflects Husserl’s idea of bracketing, where the researcher puts aside their judgments to understand the phenomenon better. Two techniques were employed to enhance the credibility of the interview findings and reduce potential biases from the researcher: Peer review and member checking. In this context, after analyzing the interviews, the results were shared with two experienced professors in the field of qualitative research to review and refine the data coding process.

Additionally, after the main themes were extracted, some participants were invited again to share the findings with them and obtain their feedback. In cases where participants’ feedback contradicted the analysis results, necessary revisions were made, and the themes were revised accordingly. Furthermore, throughout the interview process, the interviewer ensured the accuracy of data interpretation by asking clarifying questions and providing continuous feedback to the participants regarding their interpretations.

Results

Phase one of the study

Demographic characteristics

In this study, twelve mothers and one father who had lost their children to homicide participated, with a Mean±SD age of 55.7±8.2 years. Demographic analysis of the participants showed that most were married, and 3 had also lost their spouses. Two participants had no other children aside from the 1 who passed away, while the others had between 1 and 3 living children. Additionally, three of the participants, both men and women, had lost their spouses after the tragic event. Of the participants, only t3 were employed, while the remaining 10 were homemakers or retirees. The analysis of the victims’ demographic characteristics revealed that 69% were male (Mean±SD age: 26.5±5.4 years), and 31% were female (Mean±SD age: 24.8±7.2 years). According to the parents of the deceased individuals, 9 were single at the time of the murder, 3 were married, and 1 had been separated from their spouse.

Only one of the homicides examined in this study was classified as intrafamilial. By the time this research was conducted, the penalty of qisas-e nafs (execution) had been carried out for 3 of the perpetrators involved in the murders. Additionally, the sentence of qisas-e nafs had been issued for 3 other perpetrators; however, it was revoked due to the forgiveness granted by the victims’ next of kin. The legal proceedings for 7 participants in this study remained ongoing at the time of this research, as their cases were still under judicial review. In five of the cases, the offense involved a crime against a corpse. The term “crime against a corpse” refers to any act causing material or immaterial harm to a deceased body, encompassing actions such as mutilation of the corpse, incineration, concealment, or unlawful burial, as well as theft of property belonging to the deceased. All such acts are recognized as instances of desecration of the dead and have been criminalized under the law. Notably, in all the cases examined, the perpetrator or perpetrators of the homicide had been identified and apprehended.

Qualitative results

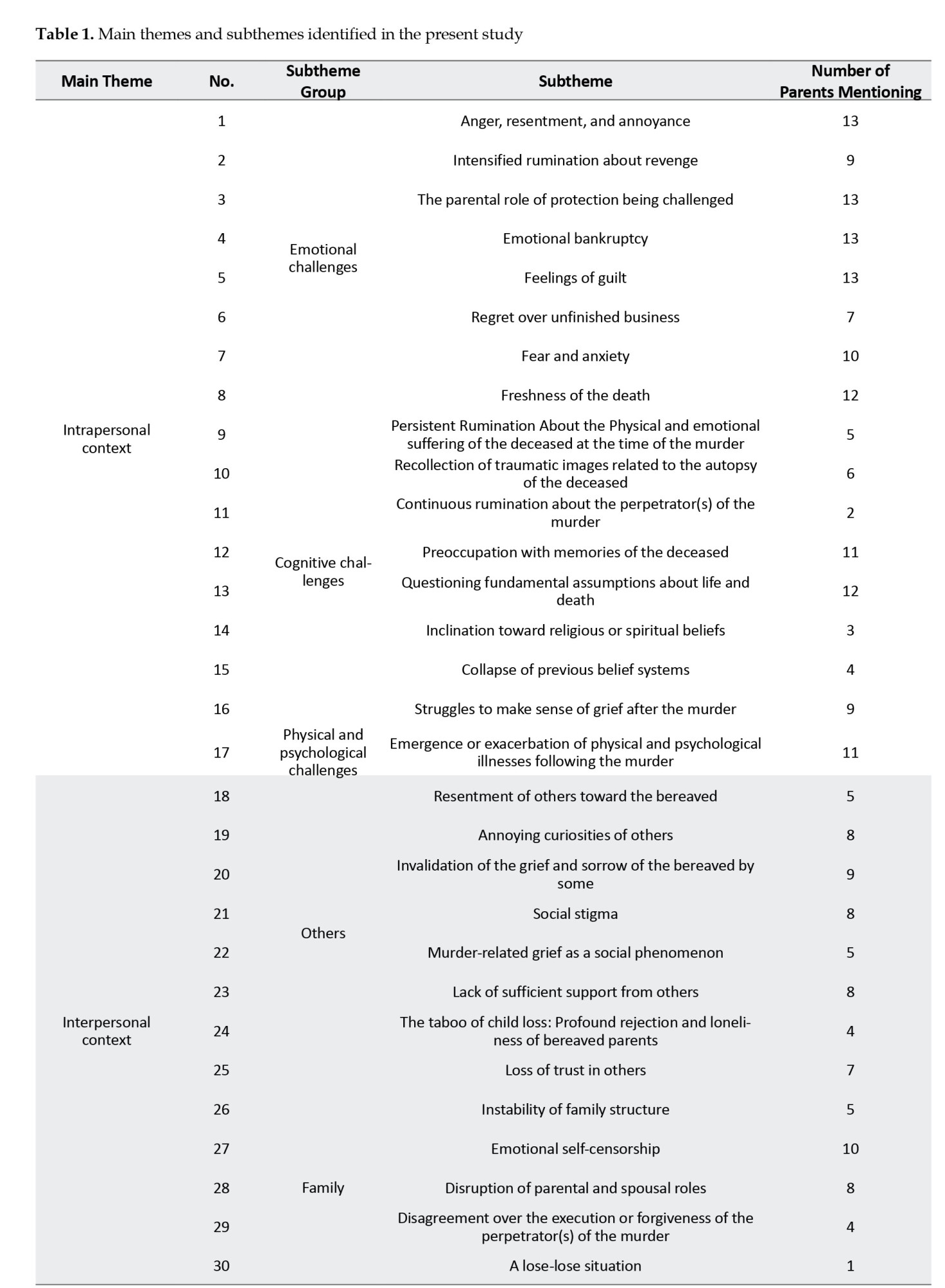

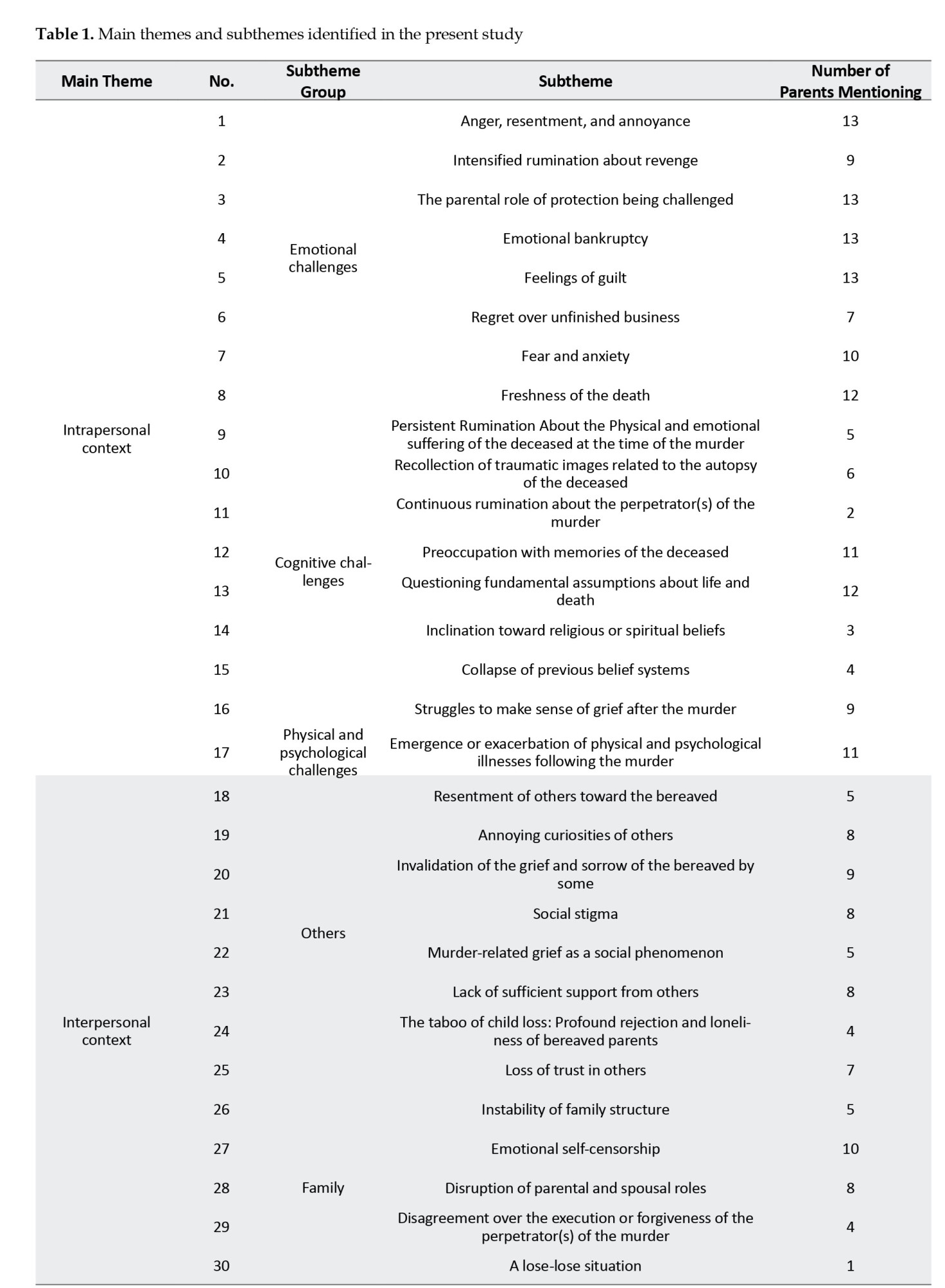

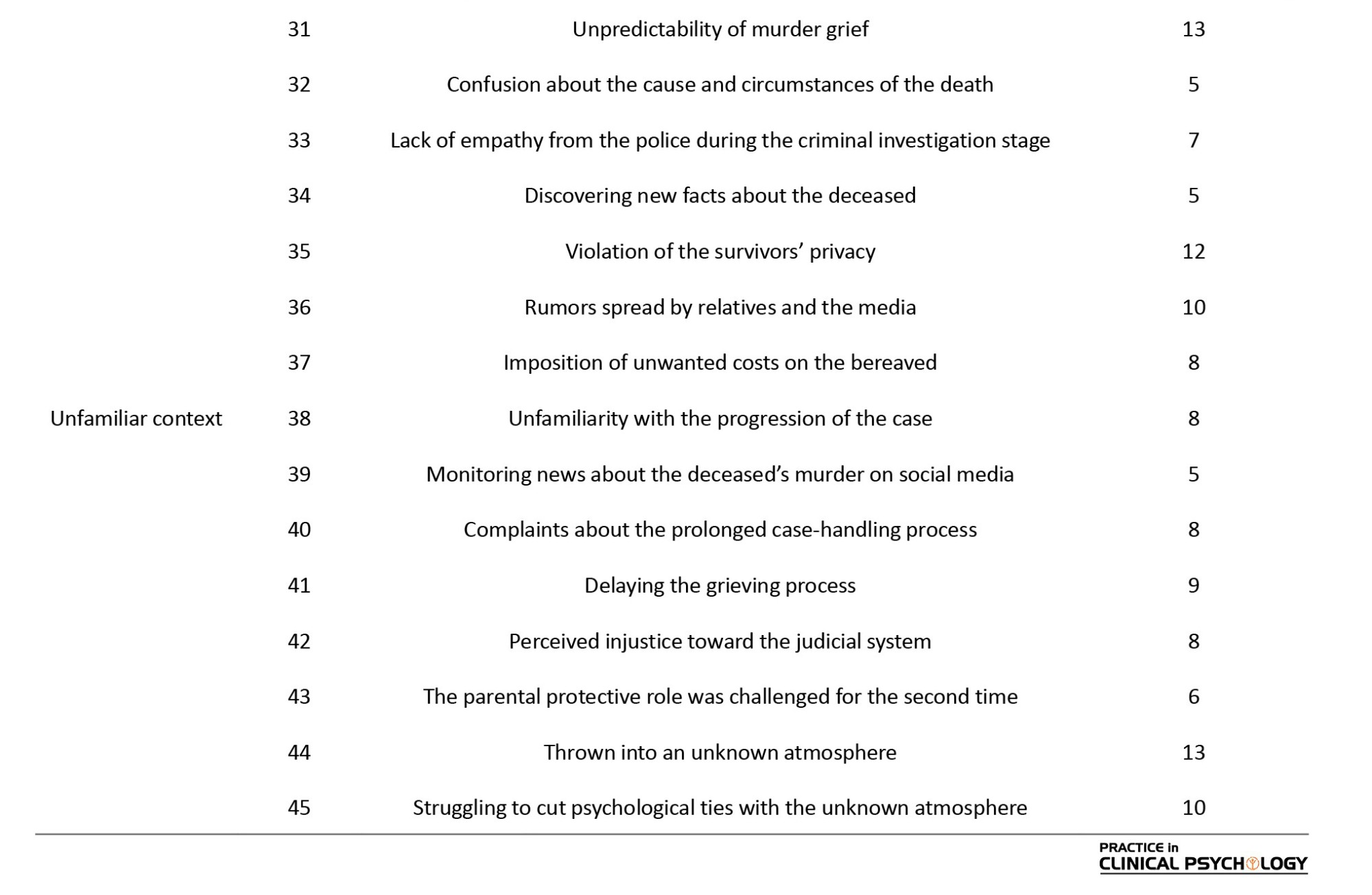

In addressing the question of the first phase of the research, based on the results obtained from the qualitative analysis of the interviews conducted in this study, a total of three primary themes—namely, the intrapersonal context, the interpersonal context, and the unfamiliar context—alongside 45 subthemes were identified. Within the intrapersonal context, 17 subthemes emerged, encompassing 8 subthemes related to emotional challenges, 8 subthemes associated with cognitive challenges, and 1 subtheme concerning physical and psychological challenges. In the interpersonal context, 13 subthemes were delineated, including 8 connected to interactions with surrounding individuals and 5 tied to family relationships. Similarly, within the unfamiliar context, 15 subthemes were recognized (Table 1).

Intrapersonal context

Emotional challenges

1) Through the qualitative analysis of the interviews, it became clear that the anger of grieving parents was directed at several different sources. They expressed frustration not only towards the perpetrators but also towards family members, their partners, the deceased, those around them, and even the law enforcement and judicial systems: ‘’Once walking down the street, I saw his father from a distance. He didn’t notice me, but I was filled with an intense urge to tear him apart’’(P7).

2) Most participants found themselves constantly consumed by thoughts of revenge toward the perpetrator(s) or their families, which hindered their grieving process. One participant expressed it this way: ‘’I kept thinking that I had to hurt them. I couldn’t just sit back and let it go. I kept telling myself their family didn’t deserve a normal life’’(P2).

3) The parents in this study often blamed themselves for their child’s murder, feeling that their parenting was somehow inadequate and played a role in the tragedy. One participant shared: ‘’I keep kicking myself, asking why I didn’t have control over him’’(P9).

4) Bereaved parents, particularly those with only one child, expressed a deep sense of loss, feeling as though they had lost something irreplaceable. One participant shared, “My motherhood toward my child remained incomplete” (P6).

5) Some participants expressed guilt for neglecting mourning rituals, such as visiting their child’s grave: “I missed visiting his grave and feel guilty, thinking he was waiting while others came” (P10).

6) Some parents experienced deep regret and a sense of unfinished business for having treated their child poorly or spoken harshly to them while they were still alive: “Every time I talk to him in my heart, I tell him that I was overwhelmed that day and didn’t mean what I said” (P1).

7) Bereaved parents voiced fears for the safety of their loved ones and the uncertainty surrounding legal proceedings: “I feared for my other kids’ safety after my son’s killer was executed in 2021” (P2).

8) Participants shared that the pain of losing their child, especially in such a tragic manner, still felt incredibly fresh, as if the event had just happened: “I can’t believe it’s been 6 years since it happened. That night still plays in my head like it was yesterday” (P5).

Cognitive challenges

9) Several participants frequently pondered whether their children had experienced physical or emotional trauma, such as assault, imprisonment, or torture, before the murder: “The coroner told us that when his killers were burning his body, he was already dead. But who knows” (P6)!

10) Many participants experienced profound distress upon seeing their children’s lifeless and disfigured bodies after the autopsy: “When we got the body back from the coroner, I was horrified. They’d cut it up in so many places and sewed it back together so sloppily” (P11).

11) Some parents, in addition to constantly wondering what kind of person their child’s killer was, had, in certain cases, searched through the perpetrator’s private life via social media platforms like Instagram. This behavior left them feeling confused and unable to understand their actions fully: “I remember I used to check his Instagram for a while. I don’t know why! Maybe I just wanted to see what kind of person he was” (P7).

12) Almost all participants experienced intense cognitive preoccupation with memories of the deceased: “When he was little, he used to get sick a lot... all those memories are hitting me now” (P6).

13) Some participating parents’ beliefs about the natural course of life and death were profoundly shaken: “I used to be a religious person, but now when someone says, ‘May God give you patience,’ I tell them, ‘Don’t say that to me!’ I hate hearing that. Just say, ‘May God take me instead’” (P13)!

14) Several participants mentioned that before this tragic event, they had held no specific religious or spiritual beliefs, but afterward, they began to embrace such beliefs: “My husband says I’ve turned into someone who’s always thinking about praying and that kind of stuff” (P2).

15) Some parents who had previously held strong religious beliefs reported that the intensity of their beliefs had decreased after the event: “My husband tells me, ‘Don’t say blasphemous stuff. You never missed your Salah’” (P11).

16) They struggled with the notion of why their loved one had to die in such a tragic manner rather than from a natural death. One participant shared an example of the harsh words they heard: ‘One time someone told me, “Look, you must’ve done something for God to punish you like this so your sins can be forgiven”’(P12).

Physical and psychological challenges

17) Parents reported experiencing physical health problems following the death of their children. One parent reflected: “I never used to get headaches—not even once—but they started last year, and now they’ve gotten even worse” (P3).

Interpersonal context

Others

18) This subtheme was reported by parents whose children had gone missing, which led them to develop suspicions about certain individuals. One parent recalled, “We started suspecting someone we knew. The police told us to report it, so we did, and that stirred up a lot of tension” (P11).

19) Survivors expressed distress over intrusive and unnecessary questions from others about the incident’s details. One survivor noted, “All those constant questions—’What happened?’ ‘How did it happen?’—they just made our pain so much worse” (P9).

20) Some people around them, whether intentionally or unintentionally, caused deep pain and distress to the grieving parents by using inappropriate words and phrases. One parent expressed their frustration, saying, “What do they mean by saying, ‘Go thank God, at least your other kid is fine and you have them’?” (P12)

21) This subtheme was particularly prominent among parents who had experienced intrafamilial homicides or murders accompanied by sexual assault against the deceased. One parent shared, “The neighbors kept saying she’d been messing around with married men, and that’s why this happened” (P12).

22) Some parents believed that although they wanted to cope with the pain of losing their child in their way, they faced difficulties due to the unintended or intentional interventions of some people around them. “My brothers say he should pay for it, that we shouldn’t forgive. But the fact that they keep bringing it up gives me so much stress”(P12).

23) Several participants reported not receiving adequate support during their mourning process, even from close family members. “They were around at first, but as time went on, they just faded away” (P3).

24) One of the main complaints reported by the parents was that some people distanced themselves from them due to superstitious beliefs. One recounted, “They didn’t invite us to the wedding—said our loss might bring bad luck” (P2).

25) Following this incident, participants developed a profound mistrust toward those around them. One participant expressed, “Whenever my daughter goes out, I get so anxious—everything just feels too messed up now” (P9).

Family members

26) Certain parents reported that their family dynamics had undergone significant disruption following this incident. One parent articulated this shift vividly: “My husband is constantly absent, and my daughters are growing increasingly distant” (P2).

27) Some parents indicated they could not openly express their painful emotions to avoid upsetting other family members. One parent (P2) elaborated on this experience: “There were many moments when I felt an overwhelming urge to cry, but with the children present, I suppressed it”(P2).

28) Several participants disclosed that, following this event, their interpersonal conflicts had intensified markedly. One participant stated, “Last year, I glimpsed a message on his unlocked phone and discovered he’d been secretly communicating with another woman”(P2).

29) Following the issuance of the court’s final verdict, certain participants experienced significant intrafamily tension due to differing opinions on whether the perpetrator should face execution or retribution. “I couldn’t stomach the idea of more bloodshed, but a thirst for revenge consumed my children, and now they’ve stopped speaking to me altogether”(P8).

30) This subtheme focused on parents who had endured the trauma of domestic homicide within their family. Beyond the overwhelming grief and sorrow of losing their child, they also grappled with an intricate array of emotions toward the family member who committed the act. “We don’t know which one we should cry and mourn for”(P10).

Unfamiliar context

31) For the majority of parents, the loss of their children—particularly through such a tragic and violent circumstance—was an unthinkable prospect before the event. One parent stated, “I never imagined a day would come when we’d lose our child in a way like this” (P11).

32) Certain parents remained deeply perplexed about the circumstances surrounding their child’s murder, even after a prolonged period had elapsed. One parent articulated this lingering uncertainty, stating, “We never learned what happened, how she lost her life, or why she was even in that place”(P12).

33) Certain parents expressed frustration over the lack of satisfactory responses from police or judicial authorities following their child’s murder. “They haven’t been in our position, so they can’t truly understand how we feel”(P1).

34) Some parents believed that discovering new facts about their deceased child led them to experience conflicting emotions toward them: ‘’Once, the police gave us two names and said our daughter was involved with one. I just couldn’t believe it’’(P12).

35) The media violated the privacy of some parents, criminal investigators, or even the family members and acquaintances of the perpetrator(s) as they sought to gain the consent of the victim’s family. “They took some of her belongings and asked a series of questions. Each time, I had to relive those painful moments all over again”(P9).

36) Participants expressed their distress over the spread of false information regarding the cause of the deceased’s death and even details of their private life. “Although they’ve known me for years and are fully aware of what kind of person I am, they still came back and said I must be avoiding retribution to claim blood money instead”(P3).

37) Participant 1 stated, “We spent 95 million on the first lawyer, but he did nothing. In the end, we had to borrow money from my brother.”

38) Some parents reported experiencing significant stress as they had to wait weeks for updates on their cases: “Every time we received a message, there was nothing that followed. We were all so anxious”(P11).

39) Some parents, while following updates on social media platforms like Instagram about their children’s murder, sometimes came across disturbing comments beneath the news posts. “I saw a post on Instagram once... I couldn’t even figure out who it was from. The comment said, ‘Why are you blaming yourselves so much? It was their fault for going there. When I read that, I felt physically sick”(P9).

40) Participant 2 shared, “Given our circumstances, they should have responded more quickly, but they didn’t.”

41) Some parents shared that their grief was put on hold until the final court verdict was reached: “I told everyone back then that I wouldn’t find peace until I saw my child’s killer hanging from the gallows with my own eyes” (P2).

42) Some parents were deeply angered by the sentences handed down to the other perpetrators of the murder. They believed the court had not paid enough attention to the details of their case. “The other two were also deserving of punishment, but they managed to escape it. We were deeply wronged in this situation” (P3).

43) During the investigation into their child’s case, some parents had to endure distressing remarks from the defendant or defendants, their lawyer, or even the family members of their child’s killer. These comments caused them significant pain and suffering. “They fabricated stories, claiming that she was the one carrying the knife and that she was always causing trouble”(P2).

44) The parents believed that, in addition to the lack of prior understanding and awareness, they had no control over the situation. “I would often pass by the courthouse because the path to our store was right there... I had never even considered that one day our situation might lead us to such a place” (P1).

45) Participant 9 shared, “I just want everything to end and the messages to stop. Right now, I need to focus on my pain.”

Phase two of the study

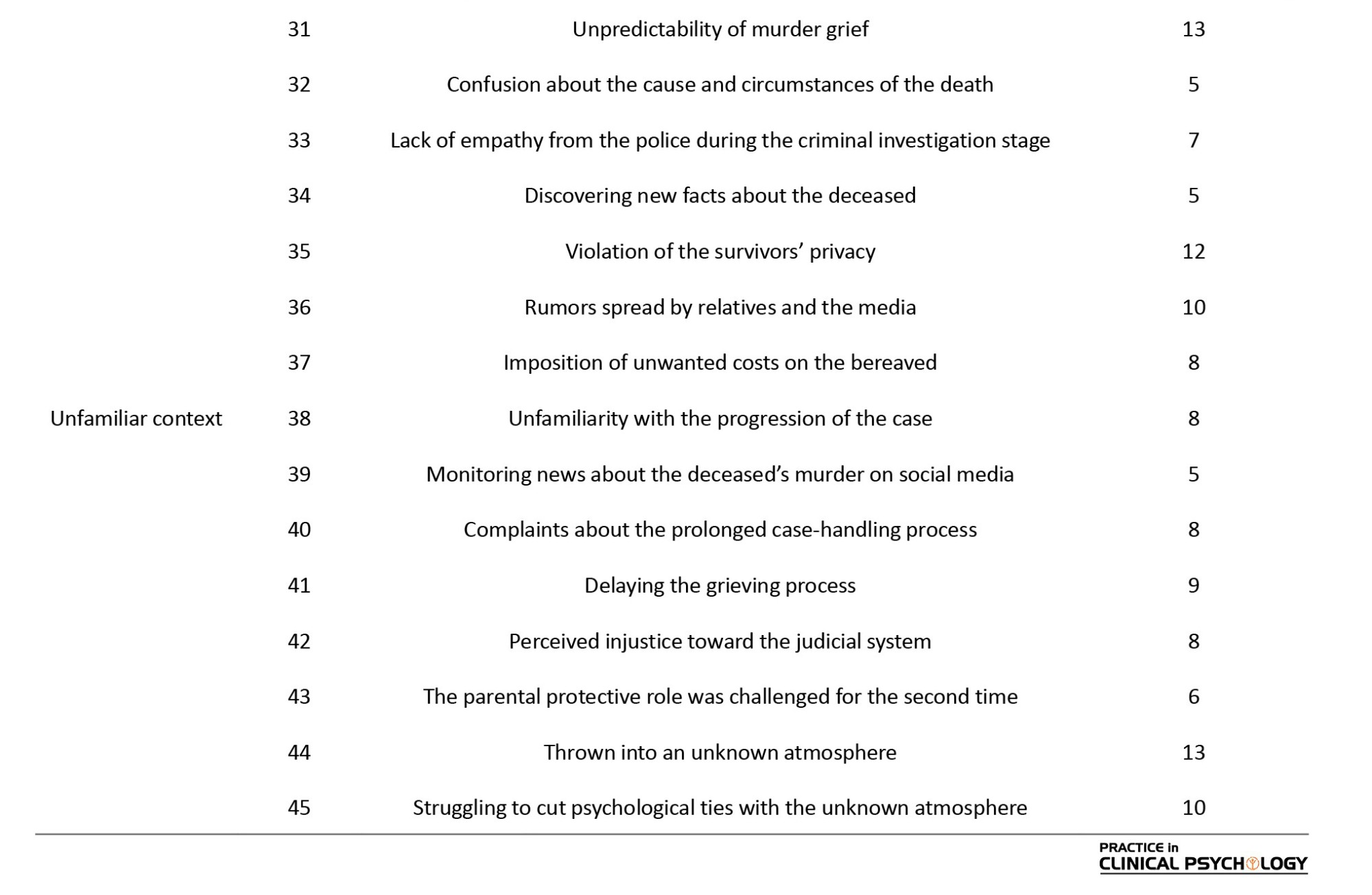

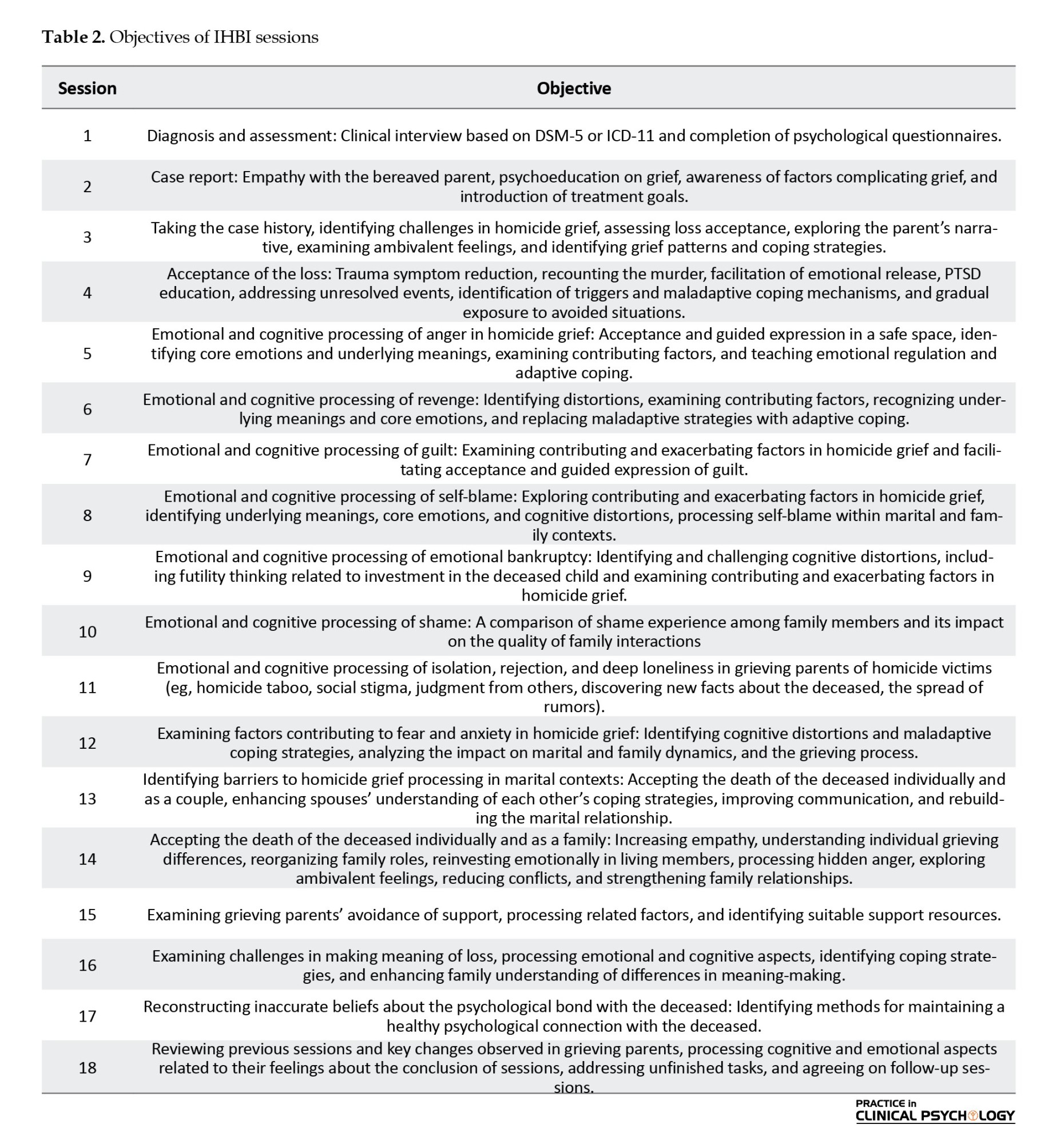

To answer the first research question in the second phase, an integrative homicide bereavement intervention (IHBI) was developed based on the analysis of the findings from the study’s first phase and their integration with previous research in the field (Table 2). This intervention was designed according to an integrative perspective and consists of three stages, with the goals of each stage outlined as follows:

Stage one (sessions 1 to 3): Clarifying the nature of complicated grief, emphasizing the necessity of addressing it, and identifying the challenges related to intrapersonal, interpersonal, and unknown aspects of homicide grief.

Stage two (sessions 4 to 15): Reducing symptoms of homicide grief trauma and processing emotional-cognitive challenges related to intrapersonal, interpersonal, and unknown aspects of homicide grief.

Stage three (sessions 16 to 18): Reconstructing meaning, repairing, and maintaining the emotional bond with the deceased child while keeping their memory alive.

After drafting the initial version of the intervention, to assess the validity of the proposed protocol, the content of the sessions, along with a questionnaire and an explanation about the study’s objectives and the operational definitions of the research variables, was sent to 15 specialists with expertise in grief and clinical experience. They were asked to evaluate the relevance of each item in the protocol to the research objectives and to provide feedback on the necessity of each item. Additionally, they were invited to offer suggestions for removing, merging, renaming, or modifying the content of any item. Their feedback was then collected and quantitatively analyzed using two content validity indicators: The content validity index (CVI) and the content validity ratio (CVR), as proposed by Waltz and Bausell (1981) and Lawshe (1975), respectively. The CVI and CVR values were calculated to be 0.98 and 0.84, indicating satisfactory content validity of the intervention. Guba and Lincoln’s (1985) criteria for trustworthiness—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—were applied to assess the quality and reliability of the findings from this phase of the study.

Discussion

The current study was undertaken to elucidate the nature of complicated grief in parents who have lost a child to intentional homicide and to develop an integrated intervention based on the findings of this research alongside insights from prior studies. The initial phase aimed to explore the essence of grief and how these parents experience it. To achieve this, eligible participants were identified by reviewing relevant case files in the judicial courts of Gilan Province, Iran. After providing informed consent, these parents participated in semi-structured interviews.

The findings reveal that bereaved parents grappling with homicide-related grief encounter not only intrapersonal and interpersonal challenges but also unique difficulties stemming from the unfamiliar context of this type of loss, setting it apart from other forms of grief. They enter this experience without prior preparation or understanding, thrust into an exhausting ordeal. For them, the only path to relief seems to lie in relentless struggle and pursuit of justice until a final verdict is reached. It is as though only after this point can they truly begin to mourn their lost loved one. The challenges they face along this journey disrupt the healthy processing of grief-related emotions, rendering the natural mourning process profoundly difficult. The findings indicate that survivors of homicide grief are, in most instances, victimized twice: First through the murder of their loved one and then again by the judicial system, law enforcement, and media. This phenomenon, which Wolfelt (2021) refers to as “secondary victimization,” stands out as a critical characteristic of homicide-related grief (Englebrecht et al., 2014; Reed & Caraballo, 2022; Mohamed Hussin et al., 2024). It emerges when survivors face compounded pressure from media scrutiny, the criminal justice system, public judgment, and even their immediate social circles, resulting in further psychological harm.

Homicide grief, due to its unique and unexpected challenges, exacerbates intrapersonal and interpersonal issues for survivors, imposing what can be described as “psychological overload” (Asaro, 2001). This type of grief is influenced not only by the loss of the deceased but also by the circumstances and nature of their death. In other words, survivors dealing with this type of grief are not only faced with the challenge of coming to terms with the death itself but are also preoccupied with the details of how their loved one died. This ruminative focus on the death’s circumstances intensifies their grief symptoms (Wolfelt, 2021).

The findings of this study also reveal that parents who have lost a child to homicide experience this loss not only on a personal level but also within the broader context of their interpersonal relationships and social interactions. This condition results in numerous challenges, from outside and inside the family, transforming this grief into a complex and multi-layered experience. Family members may blame each other for insufficient care or oversight regarding the behavior and decisions of the deceased child. Such dynamics can disrupt parental and marital roles. Consequently, when designing specialized interventions for this group of survivors, it seems essential to incorporate couple and family therapy approaches. The parents who participated in this study were deeply upset and angry, feeling that their protective role had been questioned. They expressed this anger through blaming their partners, being aggressive toward other family members, and even ruminating obsessively about seeking revenge on the murderer or those connected to him. This persistent rumination about vengeance caused significant concern among other family members, further disrupting their collective grieving process. Frederickson (2013) argued that anger served as a defensive reaction that bereaved individuals employed to shield themselves from the pain of grief. In essence, when someone mourning a loss seeks to avoid confronting its raw sting, they may lean on anger as a protective mechanism. This anger can offer a fleeting sense of reclaiming the control that grief has stripped away while keeping deeper emotions—such as fear and sadness—tucked out of sight. However, when a person becomes trapped in constant rumination over painful thoughts, it can make processing and coming to terms with the loss far more challenging, ultimately prolonging and intensifying grief symptoms (Milman et al., 2019).

The findings of this study indicate that bereaved parents who have lost a child to homicide may face significant financial and psychological challenges in the unfamiliar and complex context of homicide grief. Additionally, inappropriate police handling during criminal investigations (Reed et al., 2020) and exposure to new information about the deceased individual can further immerse them in sorrow. In cases where the homicide garners media attention, families encounter further challenges, such as the spread of inaccurate reports by media outlets and those around them. Under these circumstances, they may feel compelled to constantly monitor news related to the murder on social media platforms. The media coverage of the homicide not only violates their privacy (DeYoung & Buzzi, 2003) but also intensifies their psychological suffering.

Another obstacle for parents navigating the unfamiliar realm of homicide grief arises from their interactions with the law enforcement and judicial systems. For instance, attending court hearings stood out as a significant challenge for the bereaved parents in this study. While the defense attorney’s role is strictly to safeguard their client’s legal rights, they might—intentionally or not—make remarks during the trial aimed at exonerating their client that end up causing distress and heartache for the victim’s family. These statements can be excruciating to hear, leaving parents with a piercing sense that they failed to protect their lost loved one and reinforcing the feeling that they’ve been victimized all over again. The prolonged timeline of legal proceedings is equally daunting, another key challenge in this uncharted grieving process. This drawn-out ordeal does not only fuel intense stress and restlessness in these grieving parents (Johnson, 2021) but also plunges them into a state of psychological limbo and emotional uncertainty. As a result, many parents mourning a murdered child put their grieving on hold until the court delivers its final verdict. This delay not only hampers their ability to engage in a natural mourning process but also deepens the complexity of their grief. The situation becomes even more dire when the judicial system lacks the transparency and empathy to ease their burden, amplifying an overwhelming emotional strain.

At the end of this tumultuous journey, just when it seems that the hardships and struggles might finally be drawing to a close, the issuance of the court’s final verdict regarding the perpetrators and their accomplices can upend everything, thrusting bereaved parents into a fresh wave of unfamiliar and daunting challenges. Upon hearing the rulings, they may feel that justice has not been fully served (Hava, 2024; Huggins & Hinkson, 2022), reigniting a sense of secondary victimization (Englebrecht et al., 2014). In some cases, the verdict may align with the survivors’ hopes. Yet, they then face another profound dilemma: A rift over whether to pursue execution or grant forgiveness to the offenders. This tension often fractures family unity, creating divisions among relatives, extended kin, and spouses. At times, husbands and wives are at odds over this life-or-death decision, driving an emotional wedge between them. Interventions from well-meaning relatives or friends about the issue of retribution can deepen these rifts, adding to the anguish and sorrow of grieving parents. As Whittmire (2016) rightly observed, homicide grief transcends the realm of personal experience, emerging instead as a profoundly social phenomenon. In a society like Iran, with its unique cultural and social fabric, this type of grief is shaped not just by individual and psychological factors but by a complex web of social, cultural, and judicial influences that render it a collective ordeal. For instance, in Iran’s more traditional regions, where retribution is often prized as a moral value, some survivors find themselves caught in a wrenching bind between seeking vengeance or offering mercy. Compounding this, media outlets and social networks, through their extensive coverage of murder cases and emotionally charged narratives, can sway survivors’ feelings and even steer their decision-making in unexpected directions.

In the second phase of this study, based on the main subthemes derived from the first phase and previous studies in this field, an intervention for grief caused by homicide (specifically for grieving parents) was developed using an integrative approach. A group of counseling and psychology specialists assessed the content validity of this intervention. Given that the integrative approach adopts a flexible attitude towards various therapeutic models and can encompass techniques from different approaches, with the treatment modality chosen based on the individual’s characteristics, specific needs, and cultural context, various techniques from different therapeutic models were employed in crafting this intervention. The three-phase intervention developed aims to heal the wounds within the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and unfamiliar context of homicide grief, incorporating several individual, couple, and family therapy sessions. The results indicated that the intervention had acceptable content validity and could serve as a specialized intervention to meet the needs of families who have lost a child to homicide. This intervention seeks to mitigate the symptoms of complicated grief by enhancing grieving parents’ general and legal knowledge while boosting their cognitive and emotional capacities to cope with the challenging circumstances ahead. Emphasizing a blend of cognitive, emotional, and educational techniques alongside efforts to foster resilience encourages parents to come to terms with the reality that they cannot control or alter every aspect of their situation. Far from being a weakness, this acceptance is framed as a skill. Key objectives include facilitating the healthy processing of emotions tied to homicide grief—such as shame, guilt, self-blame, anger, and vengeful impulses—while identifying underlying meanings of core emotions and challenging cognitive distortions and errors in the bereaved parents’ thinking.

Additionally, given that the violent death of a family member can trigger trauma responses in other family members, each may respond to the loss in their own unique way. Therefore, another objective of the intervention is strengthening the grieving survivors’ marital and family support systems, reinforcing their parenting and spousal roles. Based on the findings of the current study, survivors of homicide grief face specific challenges in the unfamiliar context of this form of loss, many of which are beyond their control. The sudden and violent nature of such a death places survivors in a position where, beyond grappling with the absence of their loved one, they must also manage the intricate psychological, social, and legal repercussions of the event. Factors such as privacy breaches, the spread of misinformation by media or those close to them, prolonged legal proceedings, the questioning of their protective role during court sessions, and a lack of empathy from law enforcement and judicial personnel can all heighten their stress and psychological wounds. These circumstances significantly erode survivors’ resilience, potentially leading to a loss of emotional regulation. Consequently, beyond deploying specialized interventions, a cornerstone of working with this group is fostering resilience to aid their adjustment, reduce psychological harm, and enhance their capacity to face this crisis. This priority is thoughtfully woven into the proposed intervention, reflecting a commitment to supporting these parents through their profound and multifaceted grief.

Given that the primary focus of this study was on a specific sample and context of grief, namely, the loss of a family member due to intentional homicide, caution is warranted when generalizing its findings to other samples or contexts. Another limitation of this research was the greater access to bereaved mothers compared to bereaved fathers. Considering the well-documented gender differences in grief responses, this imbalance could naturally have shaped the study’s outcomes. Furthermore, the criminal justice system of the Islamic Republic of Iran differs markedly from those of many other countries in its approach to specific offenses like intentional homicide. This distinction highlights the need for comparative studies in this field, as the precise nature and extent of this system’s impact on survivors’ grieving processes remain largely unexplored.

Conclusion

This study set out to explore the experience of grief following a homicide among Iranian parents who had lost their children to murder. Drawing on the findings, an integrated intervention was developed, weaving together insights from this research with those from previous studies. The results revealed that bereaved parents of homicide victims face unique challenges tied to this type of loss, challenges that, alongside intrapersonal and interpersonal struggles, make healthy grief processing more challenging and add layers of complexity to their mourning journey. The study also demonstrated that the tailored intervention designed for this group of survivors holds promising validity. As a result, counselors and psychologists working in judicial settings can turn to this intervention to provide meaningful support to grieving parents.

Research limitations

Given that the primary focus of this study was on a specific sample and context of grief, precisely, the loss of a family member due to intentional homicide, caution should be exercised when attempting to generalize its findings to other populations or situations. Another limitation of this research was the greater accessibility to bereaved mothers compared to bereaved fathers. Considering the well-established gender differences in grief responses, this imbalance may have naturally influenced the study’s outcomes.

Future research

Given the distinct nature of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s criminal justice system compared to many countries worldwide in addressing specific crimes like intentional homicide, there is a clear call for comparative studies in this area. We still do not fully understand the scope or depth of this system’s influence on the grieving process of survivors, making such research all the more essential.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.TON.REC.1403.006).

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mohammad Reza Abdi, approved by the Department of Counseling and Psychology, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran. This research received no funding or support from public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Abbas Zabihzadeh; Data collection and investigation: Mohammad Reza Abdi; Data analysis: Mohammad Reza Abdi and Abbas Zabihzadeh; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank all the bereaved parents who participated in this study despite the immense pain and sorrow caused by their heartbreaking loss.

Reference

Grief resulting from the loss of loved ones is one of the most challenging human experiences, leaving profound and sometimes lasting effects on the lives of survivors. Typically, it is expected that children will outlive their parents. The death of a child and the disruption of this natural order of life can completely shatter parents’ hopes and aspirations (Atwood et al., 2023). Amidst this, when a human factor such as homicide plays a role in a child’s death, the parents’ grieving experience becomes significantly more complex and challenging (Boelen et al., 2015). The circumstances of death can lead to psychological issues such as depression, anger, anxiety, and complicated grief in survivors (Mansoori et al., 2020). Studies have shown that sudden and violent deaths, such as homicides, impose significant psychological and emotional challenges on survivors. These reactions, which manifest in different ways for each individual, include anger and a strong desire for revenge (Gollwitzer & Denzler, 2009; Choi & Cho, 2020), feelings of guilt and social stigma (Frei-Landau et al., 2023), entanglement in a lengthy and complex legal process accompanied by significant psychological pressure (Alves-Costa et al., 2023; Kashka & Beard, 1999), feelings of fear and insecurity regarding personal safety and that of loved ones (Eagle, 2020), the breakdown of value systems and beliefs (Varga et al., 2020), the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Choi & Cho, 2020), withdrawal, isolation, and decreased social interactions (Berrozpe et al., 2024), feelings of injustice (Champion & Kilcullen, 2023; Hava, 2024; Huggins & Hinkson, 2022), disruption of communication and family patterns (Costa et al., 2017), and the loss of privacy (Armour, 2007).

Although complicated grief is recognized as a disorder in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), it remains an emerging topic that requires further research in psychology. A review of the literature on homicide-related grief reveals that studies explicitly focusing on the lived experience of parents grieving the murder of their child are limited. Furthermore, among the few studies conducted, no research has been carried out in Iran on this issue. In addition, the model of complicated grief is deeply culture-dependent, and it may differ for each country based on its unique cultural characteristics (Silverman et al., 2021). Moreover, previous research indicates that grief resulting from homicide is not only dependent on an individual’s internal factors but also influenced by the judicial system and criminal justice practices in the societies where the grief occurs (Kashka & Beard, 1999). In addition, the absence of a standardized intervention for homicide survivors has led many therapists to rely on conventional therapeutic approaches, such as interventions designed explicitly for anxiety, depression, PTSD, and psychosomatic symptoms, which were initially developed for other psychological conditions (Feigelman et al., 2011). Although the effectiveness of some specialized interventions, such as restorative recounting, teaching coping strategies, sharing emotions, addressing PTSD symptoms, and anger management (Salloum et al., 2001), has been examined in previous studies, it seems that developing an integrated intervention that considers the specific needs of this group of survivors while taking into account the social and judicial context of Iranian society, could have a significant impact on the more effective implementation of therapeutic interventions. This factor would play a crucial role in facilitating their psychological and emotional recovery process. Considering these points and taking into account the social and judicial differences between Iranian society and other global communities, which may lead to a distinct experience and perception of homicide grief among Iranian bereaved parents, the importance of this study becomes even more evident. This research could enhance our understanding of this type of loss and provide a foundation for developing an effective intervention to assist this group of survivors.

Furthermore, considering the high prevalence of violent crimes, such as homicide in Iran, and their long-term effects on survivors, a thorough understanding of homicide-related grief is crucial. This understanding can help us better address the needs and challenges of this group of survivors and design more specialized and effective therapeutic interventions for them. Additionally, the findings of this study could be valuable for counselors and psychologists working with this group in judicial environments, assisting them in providing better support. The present study will be conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the researcher aims to understand the nature of grief experienced by parents who have lost their children due to homicide and to identify the specific issues and challenges these parents face during the grieving process. The question is: What are the emotions, issues, and specific problems experienced by parents who have lost their child to homicide about this loss?

In the second phase, based on the qualitative analysis of the findings from the first phase and integrating them with the results of previous studies in this area, a specialized intervention for homicide-related grief will be designed and proposed. This intervention, developed using an integrated approach, will address the crucial key themes when working with these parents. Finally, the content validity of this intervention will be assessed by a group of psychologists with clinical experience in grief counseling. Therefore, two questions will be addressed in the second phase:

What factors should be considered when designing an integrated intervention for homicide-related grief for parents who have lost their child due to homicide?

Does this integrated intervention possess the necessary content validity for grieving parents who have lost their child to homicide?

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study was conducted using a phenomenological approach and a qualitative methodology, with its epistemological foundation rooted in the philosophical assumptions of Edmund Husserl. By emphasizing an impartial understanding of participants’ unique perspectives regarding their experiences, descriptive phenomenology facilitates an authentic comprehension of phenomena by suspending the researcher’s preconceptions and prior beliefs (Abraham & Padmakumari, 2024). This bracketing of preconceptions enables the researcher to analyze individuals’ experiences in a pure form, untainted by presuppositions, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the phenomena under investigation (Chan et al., 2013). In line with this principle, the present study refrained from imposing the researcher’s biases onto the participants’ grief narratives to achieve a more genuine insight into their experiences. As a result, the research paradigm of this study is based on descriptive phenomenology, as the nature of the research questions requires a thorough exploration of the lived experiences of parents who have lost their children to homicide. Participants were asked to articulate their abstract descriptions of grief resulting from homicide by drawing upon concrete and tangible examples derived from their personal experiences following such a loss.

Statistical population

The study population consisted of all bereaved parents who had lost a child due to intentional homicide.

Sample and sampling

The sample comprised 13 mothers and fathers who had lost a child to intentional homicide between 2017 and 2022 and had either been previously involved in related judicial processes or remained engaged in such processes at the time of this research. Participants were selected through purposive sampling from judicial courts in Gilan Province, Iran. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: Possessing a minimum level of cognitive literacy to participate in interviews, at least one year has elapsed since the death of the deceased, willingness to share personal experiences, meeting the diagnostic criteria for prolonged grief disorder as outlined in the DSM-5, and scoring above 25 on the inventory of complicated grief by Prigerson et al. (1995). The exclusion criteria included withdrawal from participation, the emergence of psychological or physical issues during the study, inability to engage in interviews, and significant life changes that prevented participation. The criterion of data saturation was employed to determine the sample size. Theoretical saturation in this study was achieved after the ninth interview; however, to ensure robustness, the interview process continued until the thirteenth participant, when data saturation was confirmed.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, which commenced with open-ended questions and progressively focused on the participants’ experiences of grief following the homicide of their child. Each interview began with an open-ended question: “Please tell me about yourself, your family, and your deceased child?” Subsequently, probing questions like, “Could you elaborate further on this?” were employed to gain deeper insight into the participants’ lived experiences. To gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences, clarifying questions like “Can you give an example of that?” or “What did you mean when you said…?” were asked. The article’s first author conducted all the interviews, each lasting between 60 and 90 minutes. To ensure confidentiality, the interviews took place in a private setting. With the participants’ consent, all conversations were audio-recorded and transcribed word for word. Participants were assigned a unique code to protect their privacy and maintain anonymity.

Study procedure

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch, on February 12, 2024. All necessary legal permits were secured to carry out the research, and coordination was established with the Social Crime Prevention Department of the Gilan Judiciary. A list of homicide cases from 2016 to 2022 in Gilan Province courts was compiled, and after reviewing the key details, 36 cases that met the initial criteria were selected. Following discussions with the judges and an explanation of the research goals, the researcher contacted the victims’ families, inviting those willing to provide their initial consent. In certain instances, the defense attorneys of the grieving families were contacted to inform them of the study’s objectives and invite interested parties to contact the researcher. Ultimately, 23 parents expressed their willingness to participate. After obtaining written informed consent, the data collection process, which included interviews, was initiated.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Colaizzi’s seven-step method. This method closely aligns with Husserl’s perspective and descriptive phenomenology (Wirihana et al., 2018). In this approach, the researchers actively work to set aside their assumptions, focusing on the participants’ experiences as they indeed are, without adding personal interpretations or biases. This deed reflects Husserl’s idea of bracketing, where the researcher puts aside their judgments to understand the phenomenon better. Two techniques were employed to enhance the credibility of the interview findings and reduce potential biases from the researcher: Peer review and member checking. In this context, after analyzing the interviews, the results were shared with two experienced professors in the field of qualitative research to review and refine the data coding process.

Additionally, after the main themes were extracted, some participants were invited again to share the findings with them and obtain their feedback. In cases where participants’ feedback contradicted the analysis results, necessary revisions were made, and the themes were revised accordingly. Furthermore, throughout the interview process, the interviewer ensured the accuracy of data interpretation by asking clarifying questions and providing continuous feedback to the participants regarding their interpretations.

Results

Phase one of the study

Demographic characteristics

In this study, twelve mothers and one father who had lost their children to homicide participated, with a Mean±SD age of 55.7±8.2 years. Demographic analysis of the participants showed that most were married, and 3 had also lost their spouses. Two participants had no other children aside from the 1 who passed away, while the others had between 1 and 3 living children. Additionally, three of the participants, both men and women, had lost their spouses after the tragic event. Of the participants, only t3 were employed, while the remaining 10 were homemakers or retirees. The analysis of the victims’ demographic characteristics revealed that 69% were male (Mean±SD age: 26.5±5.4 years), and 31% were female (Mean±SD age: 24.8±7.2 years). According to the parents of the deceased individuals, 9 were single at the time of the murder, 3 were married, and 1 had been separated from their spouse.

Only one of the homicides examined in this study was classified as intrafamilial. By the time this research was conducted, the penalty of qisas-e nafs (execution) had been carried out for 3 of the perpetrators involved in the murders. Additionally, the sentence of qisas-e nafs had been issued for 3 other perpetrators; however, it was revoked due to the forgiveness granted by the victims’ next of kin. The legal proceedings for 7 participants in this study remained ongoing at the time of this research, as their cases were still under judicial review. In five of the cases, the offense involved a crime against a corpse. The term “crime against a corpse” refers to any act causing material or immaterial harm to a deceased body, encompassing actions such as mutilation of the corpse, incineration, concealment, or unlawful burial, as well as theft of property belonging to the deceased. All such acts are recognized as instances of desecration of the dead and have been criminalized under the law. Notably, in all the cases examined, the perpetrator or perpetrators of the homicide had been identified and apprehended.

Qualitative results

In addressing the question of the first phase of the research, based on the results obtained from the qualitative analysis of the interviews conducted in this study, a total of three primary themes—namely, the intrapersonal context, the interpersonal context, and the unfamiliar context—alongside 45 subthemes were identified. Within the intrapersonal context, 17 subthemes emerged, encompassing 8 subthemes related to emotional challenges, 8 subthemes associated with cognitive challenges, and 1 subtheme concerning physical and psychological challenges. In the interpersonal context, 13 subthemes were delineated, including 8 connected to interactions with surrounding individuals and 5 tied to family relationships. Similarly, within the unfamiliar context, 15 subthemes were recognized (Table 1).

Intrapersonal context

Emotional challenges

1) Through the qualitative analysis of the interviews, it became clear that the anger of grieving parents was directed at several different sources. They expressed frustration not only towards the perpetrators but also towards family members, their partners, the deceased, those around them, and even the law enforcement and judicial systems: ‘’Once walking down the street, I saw his father from a distance. He didn’t notice me, but I was filled with an intense urge to tear him apart’’(P7).

2) Most participants found themselves constantly consumed by thoughts of revenge toward the perpetrator(s) or their families, which hindered their grieving process. One participant expressed it this way: ‘’I kept thinking that I had to hurt them. I couldn’t just sit back and let it go. I kept telling myself their family didn’t deserve a normal life’’(P2).

3) The parents in this study often blamed themselves for their child’s murder, feeling that their parenting was somehow inadequate and played a role in the tragedy. One participant shared: ‘’I keep kicking myself, asking why I didn’t have control over him’’(P9).

4) Bereaved parents, particularly those with only one child, expressed a deep sense of loss, feeling as though they had lost something irreplaceable. One participant shared, “My motherhood toward my child remained incomplete” (P6).

5) Some participants expressed guilt for neglecting mourning rituals, such as visiting their child’s grave: “I missed visiting his grave and feel guilty, thinking he was waiting while others came” (P10).

6) Some parents experienced deep regret and a sense of unfinished business for having treated their child poorly or spoken harshly to them while they were still alive: “Every time I talk to him in my heart, I tell him that I was overwhelmed that day and didn’t mean what I said” (P1).

7) Bereaved parents voiced fears for the safety of their loved ones and the uncertainty surrounding legal proceedings: “I feared for my other kids’ safety after my son’s killer was executed in 2021” (P2).

8) Participants shared that the pain of losing their child, especially in such a tragic manner, still felt incredibly fresh, as if the event had just happened: “I can’t believe it’s been 6 years since it happened. That night still plays in my head like it was yesterday” (P5).

Cognitive challenges

9) Several participants frequently pondered whether their children had experienced physical or emotional trauma, such as assault, imprisonment, or torture, before the murder: “The coroner told us that when his killers were burning his body, he was already dead. But who knows” (P6)!

10) Many participants experienced profound distress upon seeing their children’s lifeless and disfigured bodies after the autopsy: “When we got the body back from the coroner, I was horrified. They’d cut it up in so many places and sewed it back together so sloppily” (P11).

11) Some parents, in addition to constantly wondering what kind of person their child’s killer was, had, in certain cases, searched through the perpetrator’s private life via social media platforms like Instagram. This behavior left them feeling confused and unable to understand their actions fully: “I remember I used to check his Instagram for a while. I don’t know why! Maybe I just wanted to see what kind of person he was” (P7).

12) Almost all participants experienced intense cognitive preoccupation with memories of the deceased: “When he was little, he used to get sick a lot... all those memories are hitting me now” (P6).

13) Some participating parents’ beliefs about the natural course of life and death were profoundly shaken: “I used to be a religious person, but now when someone says, ‘May God give you patience,’ I tell them, ‘Don’t say that to me!’ I hate hearing that. Just say, ‘May God take me instead’” (P13)!

14) Several participants mentioned that before this tragic event, they had held no specific religious or spiritual beliefs, but afterward, they began to embrace such beliefs: “My husband says I’ve turned into someone who’s always thinking about praying and that kind of stuff” (P2).

15) Some parents who had previously held strong religious beliefs reported that the intensity of their beliefs had decreased after the event: “My husband tells me, ‘Don’t say blasphemous stuff. You never missed your Salah’” (P11).

16) They struggled with the notion of why their loved one had to die in such a tragic manner rather than from a natural death. One participant shared an example of the harsh words they heard: ‘One time someone told me, “Look, you must’ve done something for God to punish you like this so your sins can be forgiven”’(P12).

Physical and psychological challenges

17) Parents reported experiencing physical health problems following the death of their children. One parent reflected: “I never used to get headaches—not even once—but they started last year, and now they’ve gotten even worse” (P3).

Interpersonal context

Others

18) This subtheme was reported by parents whose children had gone missing, which led them to develop suspicions about certain individuals. One parent recalled, “We started suspecting someone we knew. The police told us to report it, so we did, and that stirred up a lot of tension” (P11).

19) Survivors expressed distress over intrusive and unnecessary questions from others about the incident’s details. One survivor noted, “All those constant questions—’What happened?’ ‘How did it happen?’—they just made our pain so much worse” (P9).

20) Some people around them, whether intentionally or unintentionally, caused deep pain and distress to the grieving parents by using inappropriate words and phrases. One parent expressed their frustration, saying, “What do they mean by saying, ‘Go thank God, at least your other kid is fine and you have them’?” (P12)

21) This subtheme was particularly prominent among parents who had experienced intrafamilial homicides or murders accompanied by sexual assault against the deceased. One parent shared, “The neighbors kept saying she’d been messing around with married men, and that’s why this happened” (P12).

22) Some parents believed that although they wanted to cope with the pain of losing their child in their way, they faced difficulties due to the unintended or intentional interventions of some people around them. “My brothers say he should pay for it, that we shouldn’t forgive. But the fact that they keep bringing it up gives me so much stress”(P12).

23) Several participants reported not receiving adequate support during their mourning process, even from close family members. “They were around at first, but as time went on, they just faded away” (P3).

24) One of the main complaints reported by the parents was that some people distanced themselves from them due to superstitious beliefs. One recounted, “They didn’t invite us to the wedding—said our loss might bring bad luck” (P2).

25) Following this incident, participants developed a profound mistrust toward those around them. One participant expressed, “Whenever my daughter goes out, I get so anxious—everything just feels too messed up now” (P9).

Family members

26) Certain parents reported that their family dynamics had undergone significant disruption following this incident. One parent articulated this shift vividly: “My husband is constantly absent, and my daughters are growing increasingly distant” (P2).

27) Some parents indicated they could not openly express their painful emotions to avoid upsetting other family members. One parent (P2) elaborated on this experience: “There were many moments when I felt an overwhelming urge to cry, but with the children present, I suppressed it”(P2).

28) Several participants disclosed that, following this event, their interpersonal conflicts had intensified markedly. One participant stated, “Last year, I glimpsed a message on his unlocked phone and discovered he’d been secretly communicating with another woman”(P2).

29) Following the issuance of the court’s final verdict, certain participants experienced significant intrafamily tension due to differing opinions on whether the perpetrator should face execution or retribution. “I couldn’t stomach the idea of more bloodshed, but a thirst for revenge consumed my children, and now they’ve stopped speaking to me altogether”(P8).

30) This subtheme focused on parents who had endured the trauma of domestic homicide within their family. Beyond the overwhelming grief and sorrow of losing their child, they also grappled with an intricate array of emotions toward the family member who committed the act. “We don’t know which one we should cry and mourn for”(P10).

Unfamiliar context

31) For the majority of parents, the loss of their children—particularly through such a tragic and violent circumstance—was an unthinkable prospect before the event. One parent stated, “I never imagined a day would come when we’d lose our child in a way like this” (P11).

32) Certain parents remained deeply perplexed about the circumstances surrounding their child’s murder, even after a prolonged period had elapsed. One parent articulated this lingering uncertainty, stating, “We never learned what happened, how she lost her life, or why she was even in that place”(P12).

33) Certain parents expressed frustration over the lack of satisfactory responses from police or judicial authorities following their child’s murder. “They haven’t been in our position, so they can’t truly understand how we feel”(P1).

34) Some parents believed that discovering new facts about their deceased child led them to experience conflicting emotions toward them: ‘’Once, the police gave us two names and said our daughter was involved with one. I just couldn’t believe it’’(P12).

35) The media violated the privacy of some parents, criminal investigators, or even the family members and acquaintances of the perpetrator(s) as they sought to gain the consent of the victim’s family. “They took some of her belongings and asked a series of questions. Each time, I had to relive those painful moments all over again”(P9).

36) Participants expressed their distress over the spread of false information regarding the cause of the deceased’s death and even details of their private life. “Although they’ve known me for years and are fully aware of what kind of person I am, they still came back and said I must be avoiding retribution to claim blood money instead”(P3).

37) Participant 1 stated, “We spent 95 million on the first lawyer, but he did nothing. In the end, we had to borrow money from my brother.”

38) Some parents reported experiencing significant stress as they had to wait weeks for updates on their cases: “Every time we received a message, there was nothing that followed. We were all so anxious”(P11).

39) Some parents, while following updates on social media platforms like Instagram about their children’s murder, sometimes came across disturbing comments beneath the news posts. “I saw a post on Instagram once... I couldn’t even figure out who it was from. The comment said, ‘Why are you blaming yourselves so much? It was their fault for going there. When I read that, I felt physically sick”(P9).

40) Participant 2 shared, “Given our circumstances, they should have responded more quickly, but they didn’t.”

41) Some parents shared that their grief was put on hold until the final court verdict was reached: “I told everyone back then that I wouldn’t find peace until I saw my child’s killer hanging from the gallows with my own eyes” (P2).

42) Some parents were deeply angered by the sentences handed down to the other perpetrators of the murder. They believed the court had not paid enough attention to the details of their case. “The other two were also deserving of punishment, but they managed to escape it. We were deeply wronged in this situation” (P3).

43) During the investigation into their child’s case, some parents had to endure distressing remarks from the defendant or defendants, their lawyer, or even the family members of their child’s killer. These comments caused them significant pain and suffering. “They fabricated stories, claiming that she was the one carrying the knife and that she was always causing trouble”(P2).

44) The parents believed that, in addition to the lack of prior understanding and awareness, they had no control over the situation. “I would often pass by the courthouse because the path to our store was right there... I had never even considered that one day our situation might lead us to such a place” (P1).

45) Participant 9 shared, “I just want everything to end and the messages to stop. Right now, I need to focus on my pain.”

Phase two of the study

To answer the first research question in the second phase, an integrative homicide bereavement intervention (IHBI) was developed based on the analysis of the findings from the study’s first phase and their integration with previous research in the field (Table 2). This intervention was designed according to an integrative perspective and consists of three stages, with the goals of each stage outlined as follows:

Stage one (sessions 1 to 3): Clarifying the nature of complicated grief, emphasizing the necessity of addressing it, and identifying the challenges related to intrapersonal, interpersonal, and unknown aspects of homicide grief.

Stage two (sessions 4 to 15): Reducing symptoms of homicide grief trauma and processing emotional-cognitive challenges related to intrapersonal, interpersonal, and unknown aspects of homicide grief.

Stage three (sessions 16 to 18): Reconstructing meaning, repairing, and maintaining the emotional bond with the deceased child while keeping their memory alive.

After drafting the initial version of the intervention, to assess the validity of the proposed protocol, the content of the sessions, along with a questionnaire and an explanation about the study’s objectives and the operational definitions of the research variables, was sent to 15 specialists with expertise in grief and clinical experience. They were asked to evaluate the relevance of each item in the protocol to the research objectives and to provide feedback on the necessity of each item. Additionally, they were invited to offer suggestions for removing, merging, renaming, or modifying the content of any item. Their feedback was then collected and quantitatively analyzed using two content validity indicators: The content validity index (CVI) and the content validity ratio (CVR), as proposed by Waltz and Bausell (1981) and Lawshe (1975), respectively. The CVI and CVR values were calculated to be 0.98 and 0.84, indicating satisfactory content validity of the intervention. Guba and Lincoln’s (1985) criteria for trustworthiness—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—were applied to assess the quality and reliability of the findings from this phase of the study.

Discussion

The current study was undertaken to elucidate the nature of complicated grief in parents who have lost a child to intentional homicide and to develop an integrated intervention based on the findings of this research alongside insights from prior studies. The initial phase aimed to explore the essence of grief and how these parents experience it. To achieve this, eligible participants were identified by reviewing relevant case files in the judicial courts of Gilan Province, Iran. After providing informed consent, these parents participated in semi-structured interviews.