Volume 12, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

PCP 2024, 12(4): 307-322 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yousefi R N, Davari R, Jafari Roshan M. Causal Relationship of Social Health and Meaning in Life With Suicidal Thoughts in Iranian Adolescents Mediated by Perceived Social Support. PCP 2024; 12 (4) :307-322

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-957-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-957-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Social Sciences, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Social Sciences, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran. ,dr.davari-rahim@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Social Sciences, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 859 kb]

(734 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1909 Views)

Full-Text: (525 Views)

Introduction

Adolescents are one of the crucial social groups that experience many difficulties and damages due to the current social characteristics and the characteristics of adolescence. The way of life and habits of adolescence sometimes lasts until the end of life, and therefore the problems caused by it affect a lifetime rather than returning to just one period. Knowing the social factors affecting the health of adolescents helps to understand adolescence in the context of society (Ibrahimpour et al., 2019). Adolescence is a period in which a fifth of the world’s population is located, and 85% of this population of 1.2 billion live in developing countries. Every year, one million teenagers die due to accidents, suicide, violence, and complications related to preventable and treatable diseases.

According to the estimate of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017), the cause of 70% of deaths are behaviors that were created in adolescence and can be corrected. Every year, four million teenagers commit suicide, and one hundred thousand of them lead to death (Parvizi et al., 2004).

Suicide is one of the most complex human behaviors in which a person intentionally ends his life. According to WHO, more than 800 thousand people kill themselves every year (Rezaeian & Behzad, 2017). Research on suicide examines two crucial phenomena, which include suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Mortier et al., 2018). Since suicide is a major public health problem in adolescents and also in the older age of the world’s population, not only deaths due to suicide but also suicidal thoughts and attempted suicide are many events in adolescence and youth (Rezaeian & Behzad, 2017). Therefore, the importance of paying attention and dealing with this critical issue (suicide) doubles. Suicide is a multi-step process, including suicidal thoughts, suicide planning, suicide attempts, and action to end life (Hayes et al., 2020). Suicidal thoughts include preoccupation with nothingness and the desire to die (Falcone et al., 2018). Therefore, suicidal thoughts are the first step to end life and one of the predictors of suicide (Wang et al., 2019).

Social health is a function of various social and cultural factors that play a crucial role in ensuring the dynamism and efficiency of any society. Also, a critical condition for the growth and prosperity of any society is the existence of knowledgeable, efficient, and creative people (Shouichi et al., 2014). Today, the concept of social health, according to its various definitions and dimensions, is the coordination between values, interests, and attitudes in the field of action of people in society, and as a result, realistic and purposeful planning for life (Chaichi Tabrizi & Ragha Baf Shali, 2014). Social health is a concept that refers to the relationship between the two concepts of health and society. Considering that the community itself is a valid concept and its external truth depends on every person who formed it; therefore, in examining the community, above all, the people of the society should be studied. Another predictor of suicidal thoughts is finding meaning in life, which is highlighted during adolescence and the emergence of adulthood (Steger, 2012).

Understanding social support is more crucial than receiving it. In other words, a person’s understanding and attitude towards the received support is more crucial than the amount of support provided to him (Abdolazimi & Niknam, 2018). Also, in the classification of dimensions and people related to perceived social support (PSS), it is stated that PSS includes the help and support of family (PSS-Fa), friends (PSS-Fr), and other crucial people in life, which a person understands according to his/her social and personal conditions (Sadri et al., 2018).

The theorists of this field believe that social support relationships are considered by a person as an available and appropriate resource to meet her needs (Clara et al., 2003). Social support is studied in two forms, received (objective) social support (RSS) and perceived (subjective) social support (PSS) (Shang et al., 2022). In PSS, the individual’s evaluations of the availability of support when necessary and needed are examined (Gulachet, 2010). In other words, PSS is a person’s perception or experience of being loved, cared for, respected, and valued and made part of a social network with assistance and commitments to count (Taylor et al., 2004). Understanding the PSS is more crucial than receiving it. In other words, a person’s pain and attitude towards the support received is more crucial than the amount of support provided to the person. One of the psychological features that are vital in adolescence is social support. Social support refers to a mental feeling of belonging, being accepted, and being loved. Support is a relationship for every person and creates a sense of intimacy and closeness. Social support is a two-way help that creates a positive image of the individual, self-acceptance, and a feeling of love and worth. All these features give a person the opportunity for self-actualization and growth (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018).

Based on what has been said, the present study aims to answer this question, does the gender factor moderate the relationship between social health and finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts in adolescents covered by State Welfare Organization (SWO), considering the mediating role of PSS?

Materials and Methods

The current research is applied and the research method is descriptive correlational design. The research design in this study is the structural equation modeling (SEM) design. The statistical population of this research included all the boys and girls living in day care and night care centers for the SWO in 2023, Tehran, Iran. Due to the large size of the statistical population and the impossibility of accessing and obtaining permission to enter all quasi-family centers (juvenile detention centers), a multistage random sampling technique was used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included 15 to 18 years old, not being unsupervised or poorly supervised, and living in SWO centers. The exclusion criteria included suffering from mental illnesses and receiving drug therapy and psychotherapy interventions.

Procedures

Ask suicide-screening questions (ASQ)

The ASQ is a 15-item self-report suicide risk–screening measure and was designed by Olson (1984). Its main purpose is to evaluate the tendency or probability of suicide in teenagers. Each question has two options. The yes option gets a score of one and the no option gets a score of zero. Of course, this scoring method will be reversed for questions 1, 5, and 11. In adolescents who have a strong desire to commit suicide, the answers will be as follows:

1. No, 2. Yes, 3. Yes, 4. Yes, 5. No, 6. Yes, 7. Yes, 8. Yes, 9. Yes, 10. Yes, 11. No, 12. Yes, 13. Yes.

Noori (2010) found the validity of the questionnaire to be 0.65. Also, the reliability of the ASQ in teenagers was calculated using Cronbach’s α method equal to 0.69, which indicates the acceptable reliability of this questionnaire (Gatezadeh & Zhmadi, 2019)

Keyes’s social well-being questionnaire (KSWBQ)

To KSWBQ was implemented. The Keyes questionnaire. (1998) questionnaire has 20 questions and its purpose is to investigate the level of social health from different dimensions (social health, social prosperity, social cohesion, social acceptance, and social participation). The response range is of the Likert type, and the score for each option is (1. I completely disagree, 2. I disagree, 3. I have no opinion, 4. I agree, 5. I completely agree). Of course, this marking method is reversed for questions number 3, 5, 6, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and is as follows: (5. I completely disagree, 4. I disagree, 3. I have no opinion, 2. I agree, 1. I completely agree). The social health questionnaire has five dimensions, questions 1-4 are related to the dimension of social prosperity, questions 5-7 are related to social solidarity, questions 8-10 are related to social cohesion, questions 11-15 are related to social acceptance, and questions 16-20 are related to social participation. Joshenlou et al. have standardized the validity and reliability of the Keyes health questionnaire, including social health, mental and emotional health, using exploratory factor analysis, correlation analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The value of Cronbach’s α under the scales of social health was 0.59 to 0.76, and the value of Cronbach’s α for sub-scales of emotional health was between 0.43 and 0.6 (Joshanloo et al., 2006). The validity of this questionnaire has been obtained by its creators above 0.70 (keyes & Shapiro, 2004).

The meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

Steger et al. (2006) created the MLQ. It has 10 items, which include two subscales, the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. They consist of five items each. The presence of meaning subscale measures how fully respondents feel their lives are of meaning. The subscale of the presence of meaning includes these items, I understand the meaning of my life, I have found a satisfying purpose for my life, my life has a clear sense of purpose, I am looking for something that makes my life meaningful, I am looking for a purpose and ideal for my life. The search for meaning subscale measures how engaged and motivated respondents are in efforts to find meaning or deepen their understanding of meaning in their lives. The search for meaning subscale includes the following items, in my life I have a clear sense of purpose, I have a good feeling that something gives meaning to my life, I have always been looking for a purpose for my life, I have always been looking for something that gives meaning to my feeling of life, I am looking to find a purpose for my life. The MLQ assesses two dimensions of meaning in life using 10 items rated on a seven-point scale from “absolutely true” to “absolutely untrue.” The total scores of questions 2, 3, 7, 8, and 10 determine the level of a person’s effort to find meaning and the total scores of questions 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9 (question 9 with reverse coding) determine the level of meaningfulness of a person’s life. The MLQ has good reliability, test re-test stability, stable factor structure, and convergence among informants. According to Steger et al. (2006) internal consistency was good for the presence (0.86) and search (0.87) subscales. Also, the reliability was good for the presence (0.7) and search (0.73) subscales. The test and re-test reliability of MLQ in Iran was 0.84 for the presence subscale and 0.74 for the search subscale (Ostad, 2008).

Multidimensional scale of PSS (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988)

The multidimensional scale of PSS (MSPSS) is a 12-item instrument and measures social support from three sources, family, community, and friends on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum and maximum scores of the individual on the whole scale are 12 and 84, respectively, and in each of the family, social, and friend support subscales, 4 and 28 respectively. A higher score indicates greater PSS. The psychometric properties of the MSPSS have been confirmed in worldwide research. In a preliminary study, the psychometric properties of this scale in 742 samples of Iranian students and general population, 311 students, 431 general populations, Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated for the whole scale and the items of the three subscales of family (PSS-Fa), friends (PSS-Fr), and other crucial people in life, were 0.91, 0.87, 0.83 and 0.89. These coefficients confirmed the internal consistency of the multidimensional scale of PSS (Beshart, 2019).

Results

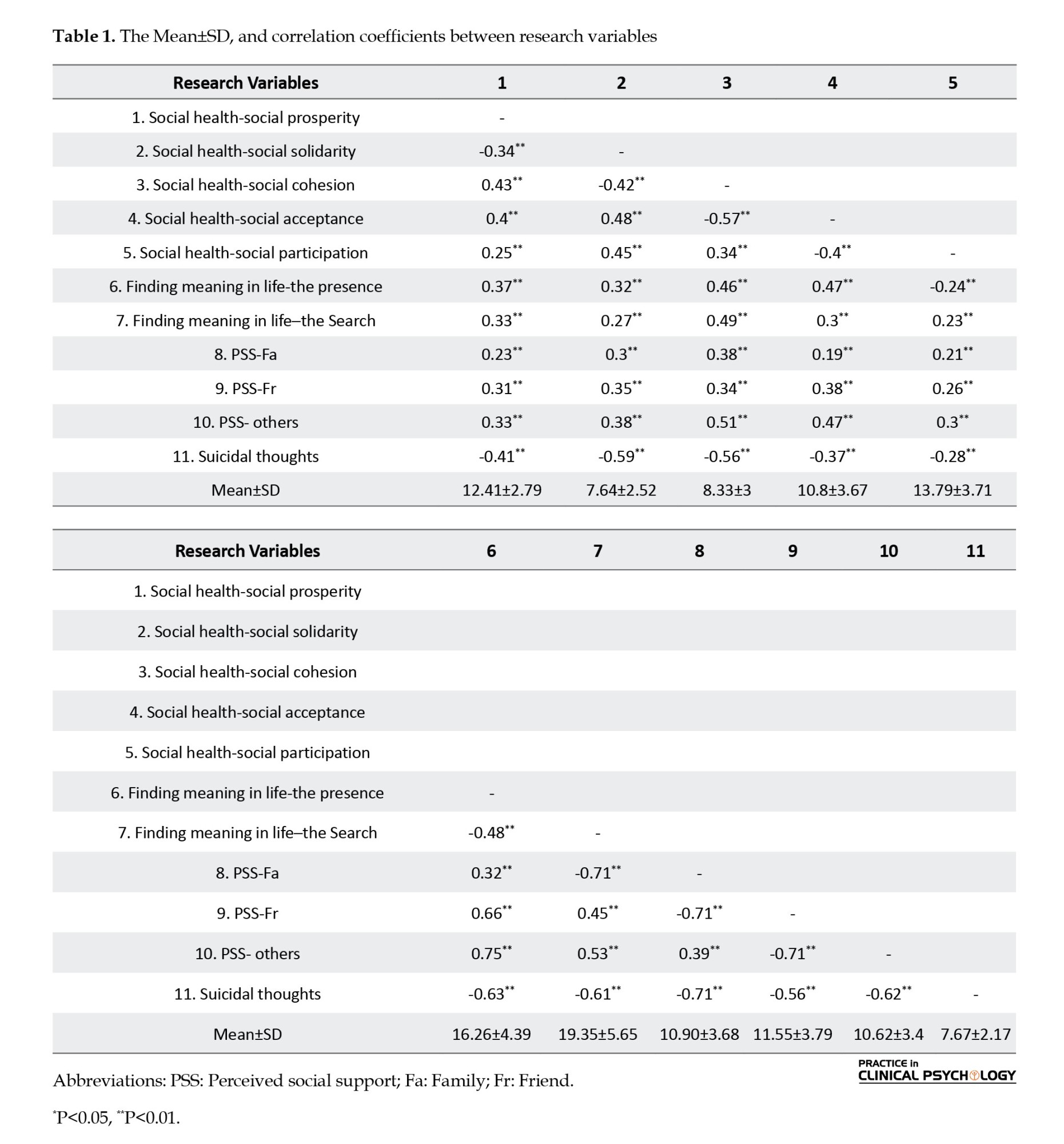

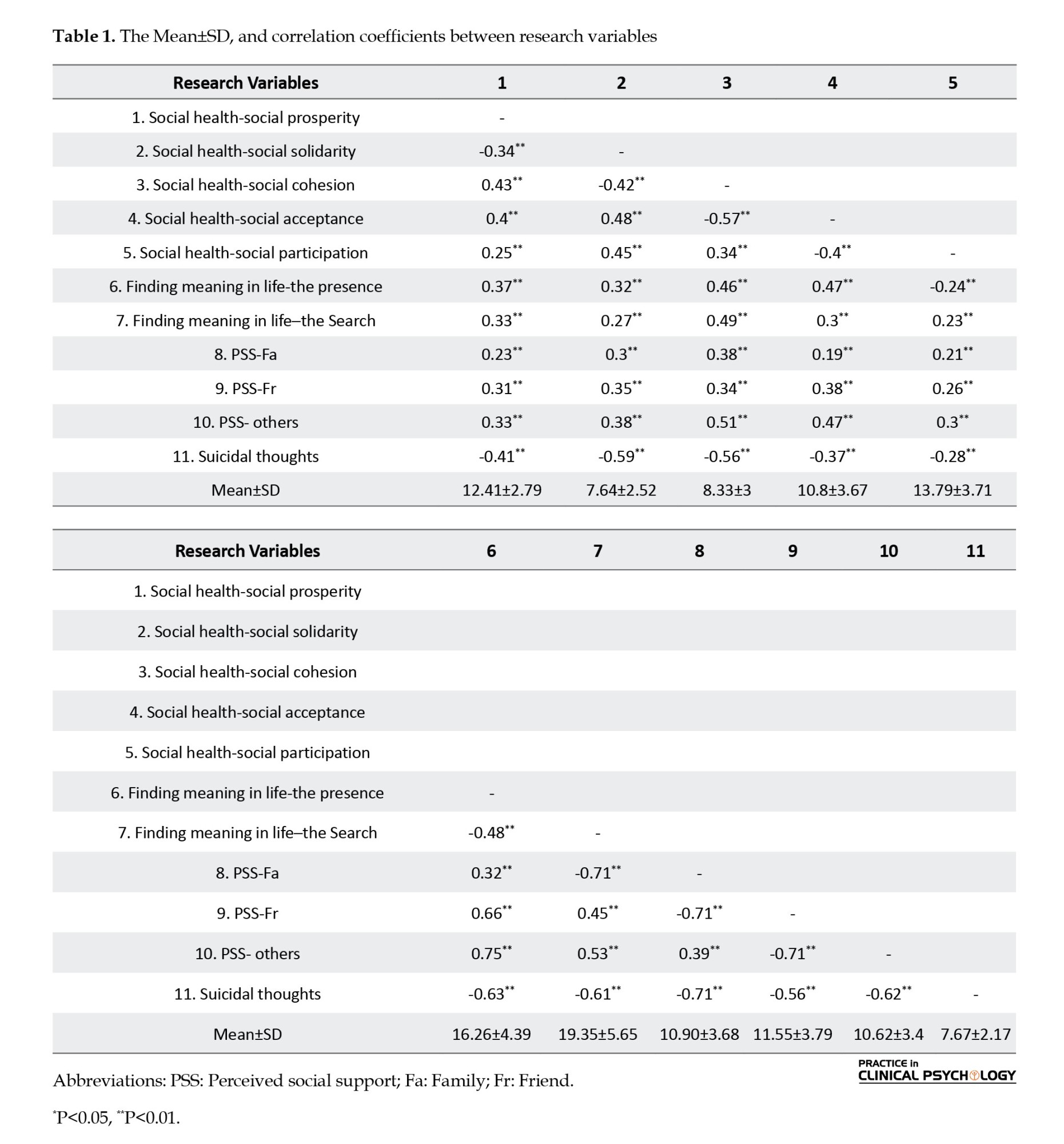

In the present study, 320 teenagers living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO (155 girls and 165 boys) participated with the Mean±SD of the age group for girls and boys equal to 15.70 and 1.35 years, respectively. Table 1 presents the Mean±SD, and correlation coefficients between the variables of finding meaning in life, social health, PSS, and suicidal thoughts. As shown in Table 1, the correlation between the variables was in the expected direction and consistent with the theories of the research field.

Univariate normal distribution

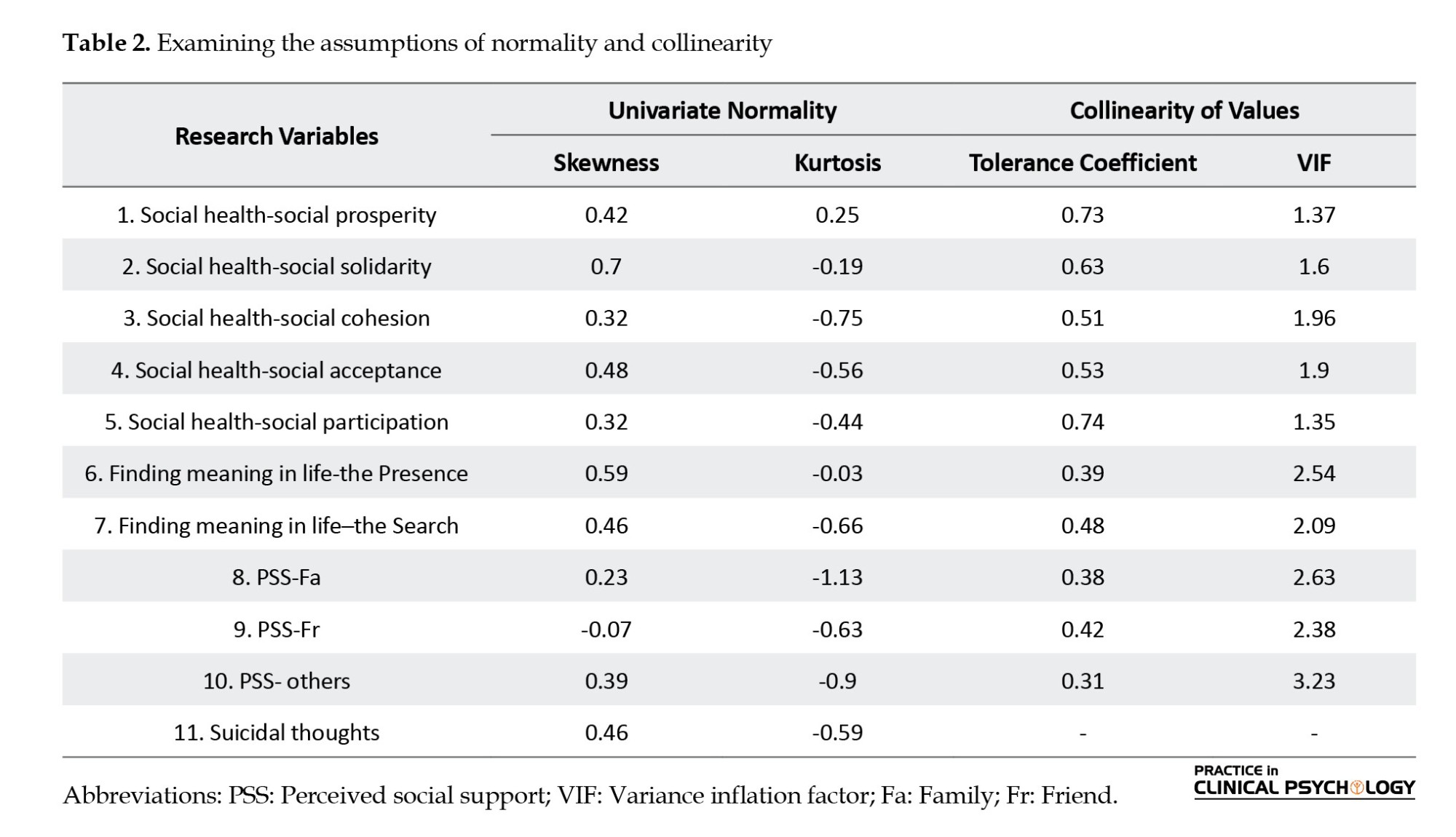

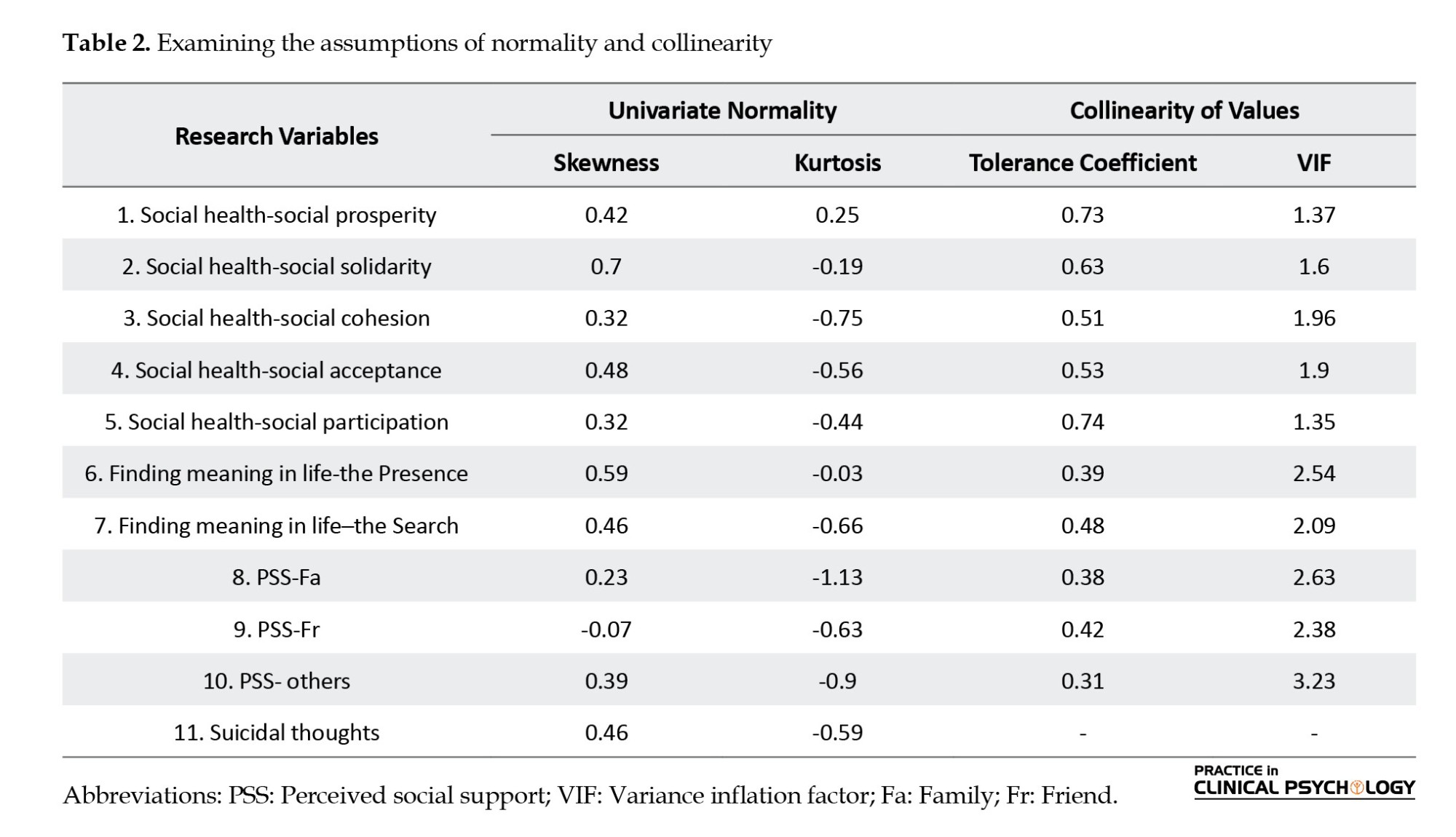

In this research, to evaluate the assumption of univariate normal distribution, Kurtosis, and skewness of the variables and to evaluate the assumption of collinearity of values, variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient were investigated (Table 2).

As shown in Table 2, the Kurtosis and Skewness values of all components are in the range of ±2. This indicates that the assumption of univariate normal distribution among the data is valid (Kline, 2023). Also, as shown in Table 2, the assumption of collinearity was valid among the data of the current research. Because the tolerance coefficient values of predictor variables were larger than 0.1 and the VIF values of each of them were smaller than 10. According to Myers et al. (2006), the tolerance coefficient is less than 0.1 and the value of the VIF is higher than 10, indicating that the assumption of collinearity is not established.

Multivariate normal distribution (MND)

In this research, to evaluate the establishment or non-establishment of the assumption of MND, the information analysis related to “the Mahalanobis distance” was used. The values of skewness and Kurtosis were obtained as 1.03 and 0.94, respectively. Therefore, the value of both indices was in the range of ±2, confirming the assumption of MND among the data. Finally, to evaluate the homogeneity of variances, the scatter diagram of the standardized residuals of the errors was examined and the evaluations showed that the assumption is also valid among the data.

Model analysis

Model specification

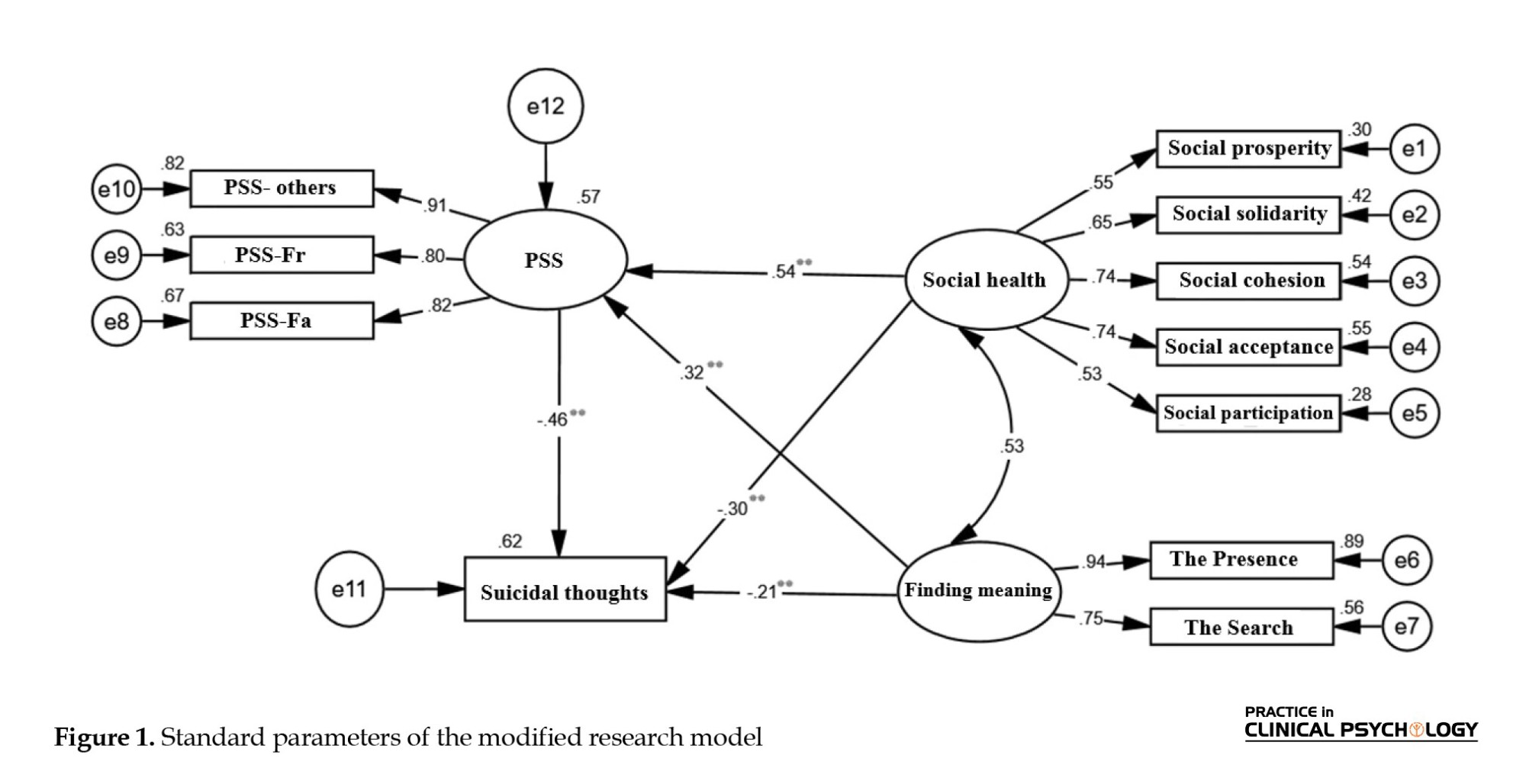

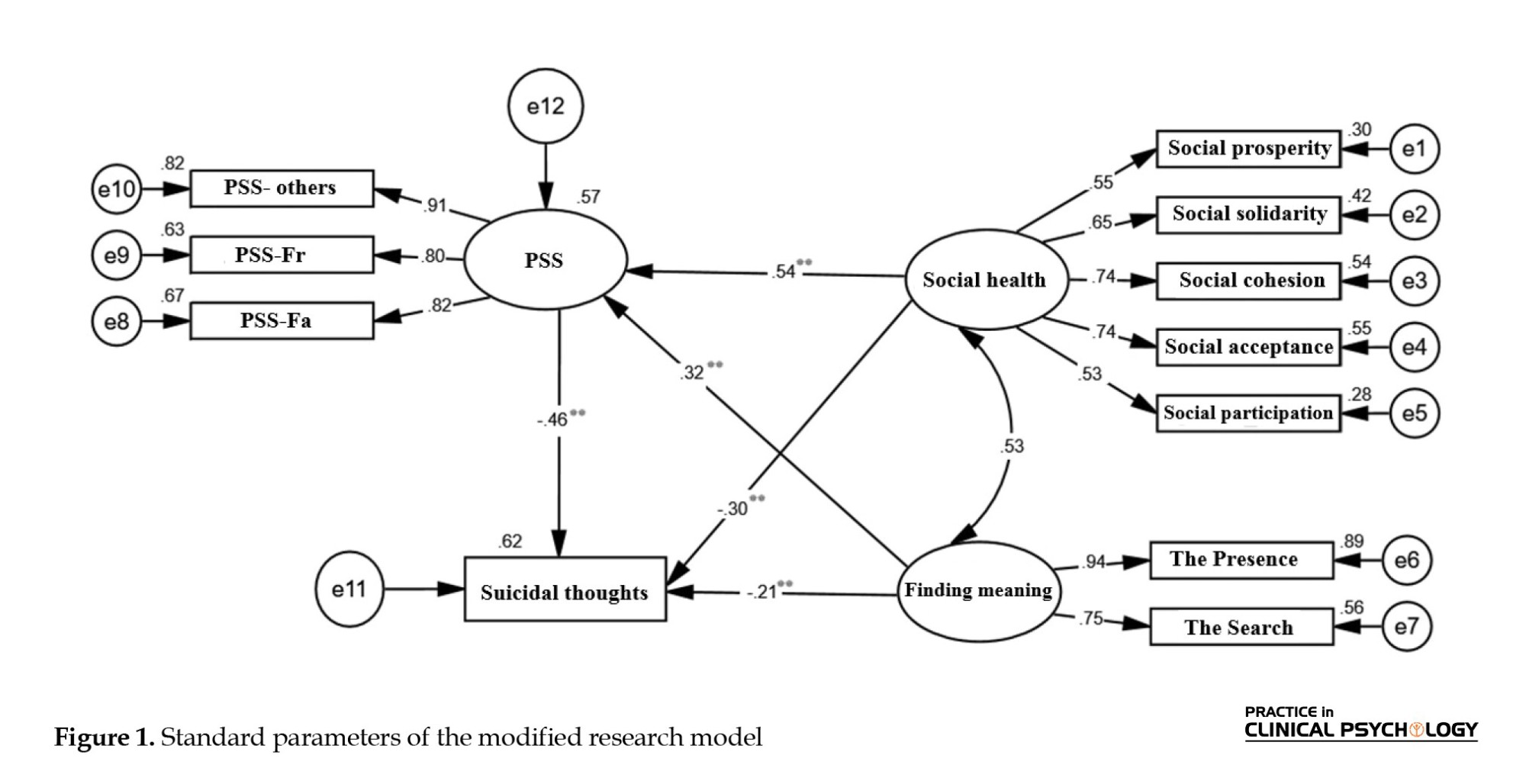

In the research measurement model, 10 indicators were considered to reflect 3 existing structures. According to Figure 1, it is assumed that indicators of social prosperity, social solidarity, social cohesion, social acceptance, and social participation measure the latent variable of social health. On the other hand, the indicators of the presence of meaning and the search for meaning measure the latent variable of finding meaning in life.

Also, indicators of PSS-Fa, PSS-Fr, and PSS-others measure the latent variable of PSS. The measurement model fit was assessed using CFA, AMOS software, version 24, and maximum likelihood estimation. Table 3 shows the fit indices of measurement and structural models.

Table 3 shows that all fit indices obtained from CFA support the acceptable measurement model fit with the collected data. In the measurement model fit, the largest factor load belonged to the presence of the meaning indicator (β=0.952) and the smallest factor load belonged to the social participation indicator (β=0.516). Thus, considering that the factor loadings of all indicators were greater than 0.32, it can be said that all of them had the necessary power to measure the current research variables.

Structural model

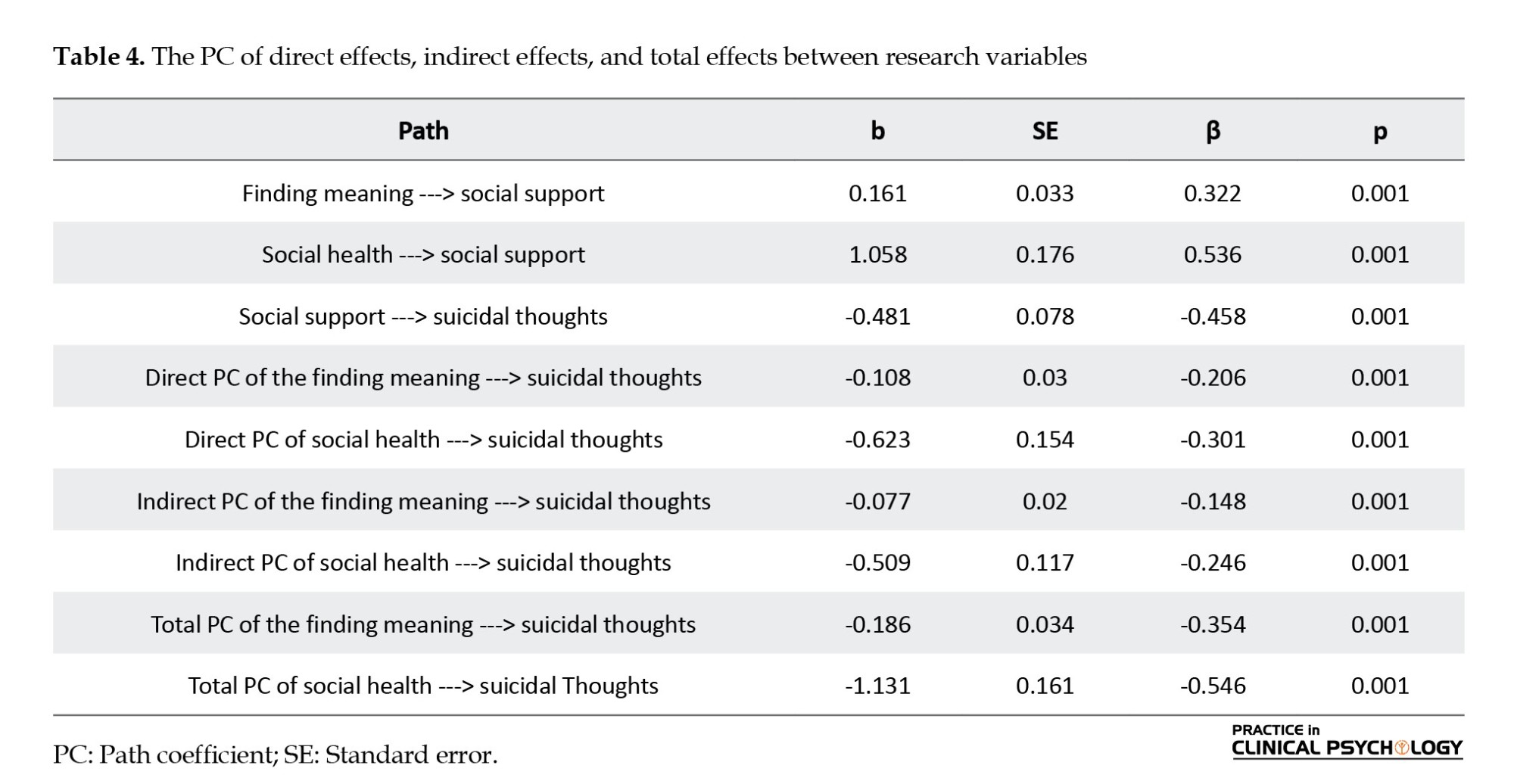

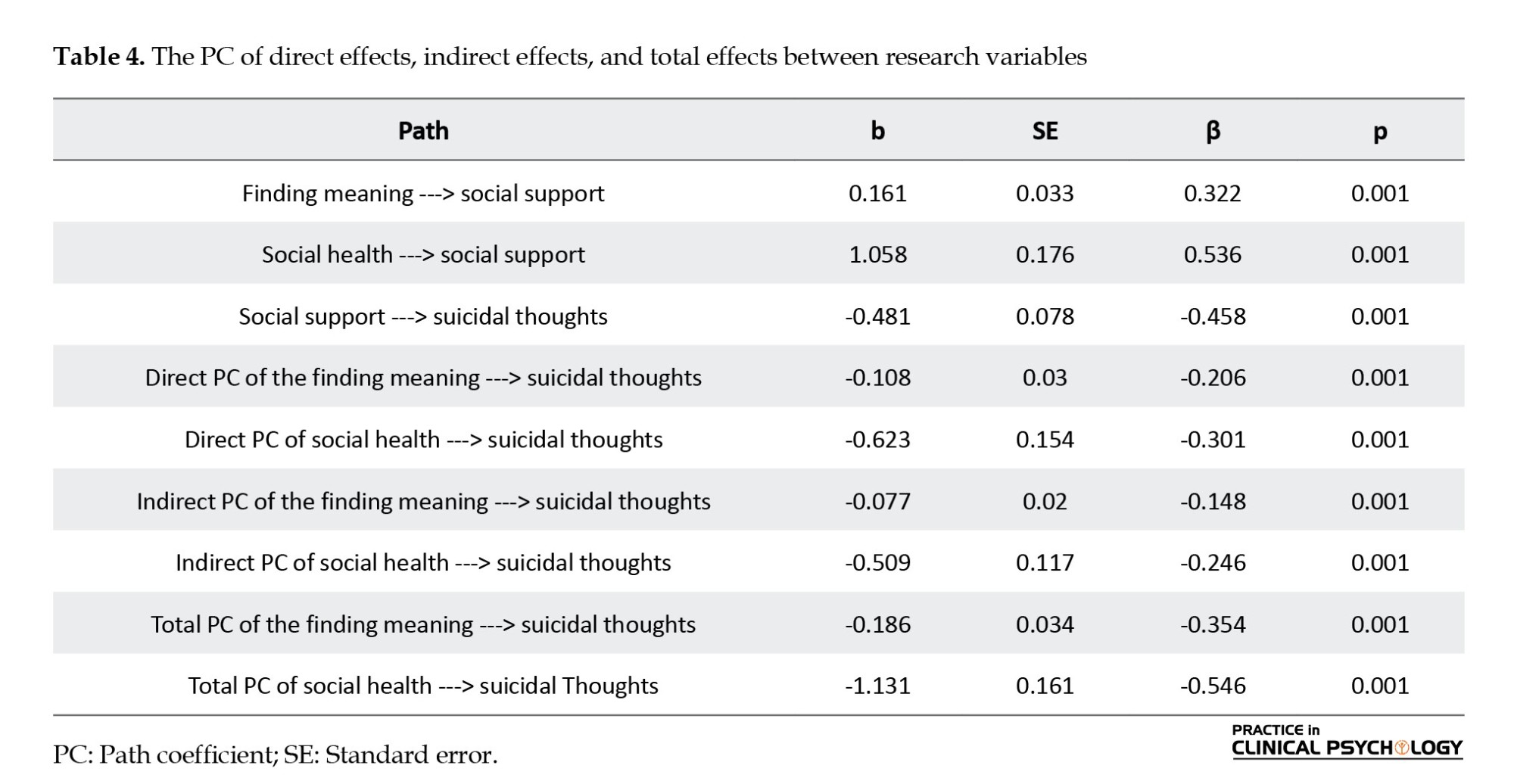

Following the evaluation of the measurement model fit, in the second stage, the fit indices of SEM were estimated and evaluated. In the SEM, it was assumed that finding meaning in life and social health are related to the mediation of PSS with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO. Table 3 presents that the fit indices obtained from the analysis support the range of acceptable values of SEM with the collected data. Table 4 presents the path coefficients (PCs) in the SEM.

Table 4 shows that the PC (direct and indirect PC) between finding meaning in life (β=-0.354, P=0.001) and social health (β=-0.546, P=0.001) was negative and significant with suicidal thoughts. Also, The PC between PSS and suicidal thoughts was negative and significant (P=0.001, β=0.458). The indirect PC between finding meaning in life (β=-0.148, P=0.001) and social health (β=-0.246, P=0.001) with suicidal thoughts were negative and significant. This result shows that in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO, the PSS mediates the relationship between finding meaning in life and social health with suicidal thoughts in a negative and significant way. Figure 1 shows the standard parameters in the SEM of the research.

Figure 1 shows the standard parameters in the research model. As shown, the sum of squared multiple correlation (R2) for suicidal thoughts was equal to 0.62. This shows that the suicidal thoughts factors of finding meaning in life, social health, and PSS explain 62% of the variance of suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO.

Discussion

First hypothesis: Social health is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO

The results showed that the PC between social health and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that social health has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO. So far, many researchers have not investigated the relationship between social health and suicidal thoughts. However, few studies have examined the components of social health (such as social solidarity and social participation) with suicidal thoughts. These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Gill et al., 2023; Nakhaei et al., 2023; Erlangen et al., 2023; Lutzman et al., 2021; Fukai et al., 2020; Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017).

Research results show that greater social solidarity reduces the possibility of suicidal thoughts (Gill et al., 2023; Nakhaei et al., 2023).

Erlangsen et al. (2023) by investigating the relationship between mental, physical, and social health measures with death caused by suicide and self-harm, showed that the existence of an active social network reduces the rate of suicide and self-harm. Also, increasing the risk of deciding and attempting suicide is more related to decreasing mental, physical, and social health, and increasing dependent personality disorder and psychological distress. Lutzman et al., (2021) found that older single men who experience physical pain may experience more loneliness and less social cohesion, factors that may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts. Goss et al. (2022) showed that social participation acts as a predictor of pathological thoughts and suicidal thoughts among the elderly population. Being in the environment and social events and relationships with colleagues and friends have protective effects against sick and suicidal thoughts. Social health status has a significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in men (but not women) and negative social health can predict the development of suicidal thoughts in men (Fukai et al., 2020). A negative and significant relationship is observed between social health and students’ suicidal thoughts; therefore with increasing social health, students’ suicidal thoughts decrease (Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017).

According to the integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018), the development of suicidal thoughts depends on motivational moderators that can enhance or weaken suicidal intent, including a sense of belonging, a sense of connection with others, a sense of heaviness, and belief in being a shouldering the burden of society. The weakness and intensity of these moderators may lead the individual to consider suicidal thoughts as the most possible solution (Gill et al., 2023). Concepts, such as feelings of social disconnection, a sense of loss of belonging, and perceived burdensomeness are central components in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (Joyner, 2009), suggesting that both interpersonal relationships and psychological characteristics, in interaction with the feeling of hopelessness, help the formation and development of suicidal thoughts (Heapy et al., 2024). It is possible that a person while having a deep sense of connection with other people, at the same time considers himself shouldering the burden of others. Therefore, several aspects of social connections, including perceived strength and quality of interpersonal relationships, and frequency of interaction with others, highlight the importance of the role of social relationships and social health in general as a known protective factor against suicidal thoughts. In particular, suicidal thoughts can be considered as a crucial predictor for transition to suicide attempt and mortality.

The results support the decrease in the frequency and quality of social communication in people with suicidal thoughts (Heapy et al., 2024). Perceptions of social isolation, being alone, and the expectation of being alone exacerbate suicidal thoughts (Gill et al., 2023). People who experience high suicidal thoughts, whether these thoughts are caused by their living environment or their inner concerns, experience a higher feeling of unhappiness, ineffectiveness, and dissatisfaction. They often feel insecure, incompetent, and alone, and find themselves powerless to solve their problems. People with suicidal thoughts believe that they will never achieve relative peace and comfort (Nakhaei et al., 2023). Improving social health through receiving and improving support networks, family support, participating in social and group activities, stress management, and learning to ask for help from others when needed is known to be useful in preventing suicidal thoughts (Fukai et al., 2020). Therefore, in line with the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (Joyner, 2009; Heapy et al., 2024), it is possible that increasing the sense of belonging and decreasing the perception of being a shouldering the burden of others is a crucial intervention strategy to weaken the link between distress and suicidal thoughts.

Social health is one of the influencing factors in the occurrence of high-risk behaviors in teenagers (Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017). In explaining this result, it can be said that high social health in teenagers increases their general health and psychological well-being. As a result, it helps to improve the feeling of satisfaction with life and reduces the tendency to nurture and strengthen suicidal thoughts. Adolescence is a period of liberation from dependence on parents and independence in various aspects of life. The future success of young people largely depends on the support of adults and institutions, such as family, schools, and community structures. Therefore, any disconnection between individuals and society can create conditions that strengthen harmful behaviors, such as suicidal thoughts. Extreme individualism, where personal desires override social ties, can contribute to this disconnect. It is essential for people to feel participation and acceptance in social structures; an experience that can prevent possible social deviations, such as suicidal thoughts in them. Social health can help reduce suicidal thoughts and improve mental health by creating a supportive environment and fostering positive relationships. This is crucial for teenagers who are forced to live in SWO centers and are deprived of the experience of living with their parents. Living in such an environment, which is associated with lack of PSS-Fa, lack of receiving affection, disorder in the formation of attachment, poor mental health, depression, low self-efficacy, social adjustment, and lower self-esteem, plays a crucial role in the tendency to high-risk behaviors, such as suicidal thoughts and actions in teenagers. This group of people in society is probably deprived of the existence of support and social networks that help to reduce the feeling of loneliness and the possibility of receiving emotional and practical support in difficult times. In addition, the lack of parental support may endanger equipping them with adapting coping strategies in facing life challenges and deprive them of communication and social skills. As a result, the lack of access to the social network and a sense of belonging may lead them to risky thoughts, such as suicidal thoughts in the face of obstacles in life.

Second hypothesis: Finding meaning in life is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO

The results showed that the PC between finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that finding meaning in life has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO.

These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Cetın et al., 2024; Gu et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2022; Marco et al., 2015; Garvier et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Costanza et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2018; Sadri Damirchi et al., 2019; Borji et al., 2018).

Cetın et al., (2024) showed that low levels of meaning in life, hope, and social support have a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts and increase the probability of using psychiatric drugs to attempt suicide in nursing students. According to Gu et al. (2023), finding meaning in life and positive and negative emotions show distinct and complex links with the three dimensions of suicidal thoughts (pessimism, sleep, and despair). Finding meaning in life and positive emotions act as a protective shield against suicidal thoughts. Sun et al., 2022, showed that although finding meaning in life does not have a direct and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts, finding meaning in life through depression has the strongest relationship with suicidal thoughts. Finding meaning in life moderates the relationship between suicidal thoughts, hopelessness, and borderline symptoms in individuals with eating disorders (Marco et al., 2015). Finding meaning in life by increasing positive emotions can reduce suicidal thoughts (Garvier et al., 2020). (Liu et al., 2021) showed that finding meaning in life has a significant and negative relationship with suicidal thoughts and behavior in students. In a systematic review, Costanza et al., (2019) found that finding meaning in life is a protective factor against suicidal thoughts and behavior. Tan et al., (2018) also found that finding meaning in life partially mediates the relationship between mental health status and the severity of suicidal thoughts. Specifically, students who experience poorer mental health status may be more likely to report having a poorer sense of meaning in life, which in turn increases suicidal thoughts. Yarian and Ameri (2020) showed a negative and significant relationship between finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts in the elderly. The presence of meaning in life leads to an increase in suicidal thoughts in students by reducing the initially incompatible schemas. Therefore, finding meaning in life is a protective factor against the risk of suicide in students (Borji et al., 2018). Sadri Demirchi et al. (2020) also showed that finding meaning in life and coping strategies can explain and predict suicidal thoughts in the elderly.

Finding meaning in life includes one’s values, experiences, goals, and beliefs, and has an inverse relationship with depression, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts (Sun et al., 2022). Finding meaning in life is considered a strong resilience factor (Costanza et al., 2019). People who feel confused about the meaning of life are prone to despair and suicidal thoughts. Individuals who reported having suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months were more likely to attempt suicide in the next 12 months (Gu et al., 2023). Among the two dimensions of finding meaning in life, the search and the presence of meaning in life, and the presence of meaning in life may be the main and key factor to prevent suicide, while the search for the meaning of life may predict suicidal thoughts (Liu et al., 2021). Otto et al. (2016) found that having meaningful moments in life can reduce frustration. Thus, meaning in life may act as a barrier against various factors that fuel suicidal thoughts, such as bullying victimization, psychological stress, hopelessness, and loss of sense of belonging.

Gu et al. (2023) showed the existence of a complex interaction between emotion, the meaning of life, and suicidal thoughts. Their results showed that negative affect is related to despair, low sleep quality, and pessimism dimensions in suicidal thoughts. Consistent with the results of Guo et al., the close relationship between finding meaning in life and emotions shows that emotions can indirectly affect suicidal thoughts and emphasizes their importance as common factors affecting suicidal thoughts. The presence of meaning in life, by helping to strengthen and improve hope, promotes mental well-being and reduces the feeling of hopelessness. The existence of ideals and values can give meaning to a difficult life and increase the sense of duty and responsibility. Finding meaning in life can help people choose a set of appropriate goals, experience a sense of agency, and accept themselves. Probably, even in the face of failure, such a person can consider more suitable paths and move forward with more hope. The destructive effect of a sense of meaninglessness can leave people feeling what Frankel called existential existential vacuum or existential frustration (Frankel, 1969).

Finding meaning in the lives of teenagers who live in care centers can have a great impact on their mental health. Therefore, in the absence of this meaning, the possibility of suicidal thoughts increases. The presence of meaning in the lives of those who feel less belonging to others may be a factor for the emergence of suicidal thoughts and even suicide attempts with frequent traumatic experiences, feelings of aimlessness, loneliness, isolation, lack of hope for the future, and feelings of worthlessness. Therefore, providing opportunities to create meaning and purpose in the lives of this group of teenagers can help reduce the risk of suicidal thoughts and improve their mental health.

Third hypothesis: PSS is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO

The results showed that the PC between PSS and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that PSS has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO.

These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Hussein & Yousef, 2024; Hofmeier et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2024; Du et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022; Arab et al. (2024); Maleki et al., 2022).

Hoffmeier et al. (2017) showed that PSS provides greater protection against suicidal thoughts for people with lower levels of mental health symptoms. Huang et al., (2024) showed that negative judgments can devalue healthcare trainees’ work, thereby creating a psychological burden that is associated with emotional exhaustion, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts. Du et al., (2021) by examining 818 studies found a negative and significant relationship between social support and suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. They also emphasized the key role of social support in preventing suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. Zhao et al., (2022) showed that PSS-Fa, and PSS-Fr, but not teachers, were inversely related to suicidal ideation in rural Chinese children experiencing rejection by others. Arab et al. (2024) showed a significant negative relationship between PSS and suicidal thoughts in high school students. Maleki et al., (2022) also support the existence of a significant negative correlation between the components of social support and life satisfaction with suicidal thoughts in students.

About half of patients who attempt or die by suicide do not disclose suicidal ideation (Rainbow et al., 2023). Thus, higher levels of psychological distress can lead to increased isolation and social withdrawal as a way to express distress. Reduced interaction with others can cause feelings of loneliness (Hofmeier et al., 2017). Consistent with these results, it seems that the risk of suicide is lower when a person has more social connections, and this emphasizes the importance of social support. However, Gill et al., (2023) believe that people experiencing distress and suicidal thoughts may hesitate to seek help for fear of not being understood by their loved ones. According to these results, for teenagers who are deprived of the possibility of receiving PSS-Fa and siblings due to their living conditions, having a strong relationship with a group can help increase the sense of belonging in people and promote the feeling of personal worth. Also, the existence of efficient social relations provides access to wider sources of social support. In such an environment, people can monitor each other’s behavior and have positive effects on each other’s psychological well-being.

Those with lifetime suicidal thoughts reported significantly less support from their family and felt more dissatisfied with this level of support (Hussein & Yousef, 2024). It seems that the ability to share thoughts and the knowledge that someone is available when needed reduces people’s feelings of loneliness. Talking about suicidal thoughts and the reactions and judgments of others can be difficult, daunting, and scary. Because people may be afraid of others’ evaluation of themselves. People around them may also think that asking more about suicidal thoughts will lead teenagers to commit suicide more. However, Huang et al., (2024) believe that asking people about suicidal thoughts helps to better understand what is happening and make a more informed decision. According to Zhao et al., (2022), talking about suicidal thoughts with a child or teenager does not lead to the development of suicidal ideas and does not increase the risk of committing suicide.

Social support increases resilience. Resilience is considered as one of the protective factors against suicidal thoughts and actions. Scher suggests that promoting resilience may reduce the risk of suicide in the general population, among those with suicidal ideation, and in high-risk groups for suicide attempts (Scher, 2023). McLean et al. (2017), also believe that most teenagers have the necessary flexibility to reduce suicidal thoughts. However, it is not definitively known which factors protect against the deleterious effect of stress against the emergence of suicidal symptoms following a stressor. Consistent with these results, it seems that the existence of a strong support system can help people use more mature coping and problem-solving strategies in stressful and critical situations, show more flexibility, cope with challenges and crises better, and finally show more resilience.

Social support can play a vital role in the mental health of adolescents who are deprived of living with their families due to living in SWO centers and help them avoid suicidal thoughts. The presence of supportive people (PSS-FA, PSS-Fr, and PSS-others) as an emotional resource can help teenagers cope better with their emotional challenges and problems and manage their negative emotions better. Social support can help this group of teenagers build positive and stable relationships by strengthening their communication and social skills. Social support can help reduce stress and psychological pressure, which can lead to a reduction in negative and suicidal thoughts.

Fourth hypothesis: PSS mediates the relationship between social health and suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO

The results showed that PSS negatively and significantly mediates the relationship between social health and suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO. No research investigated the mediating role of PSS in the relationship between SH and suicidal thoughts. But since SH and social support are related structures and close to each other, we can refer to other research that is closely related to these concepts. Tadic (2024), with a systematic review of the research, found that a large part of the articles confirms the causal relationship between social isolation and suicide, and vice versa, the protective effect of social support against suicide. In addition, the relationship between suicide and social isolation depends on age, gender, psychopathology, and specific conditions. Nakhaei et al. (2023) showed that social support has the greatest effect on suicidal thoughts and overshadows the effect of social belonging. This study reinforces Durkheim’s theory of suicide and emphasizes the importance of social interaction in preventing suicidal tendencies, which is consistent with previous research on mental health. Goss et al. (2022) showed that social participation acts as a predictor of PSS, pathological thoughts, and suicidal thoughts among the elderly population. Based on the results of Kamalipour et al. (2019), PSS-Fa through neutral belongingness and perceived burdensomeness directly and indirectly, and PSS-Fr indirectly through neutral belongingness predict suicidal thoughts. However, the relationship between PSS-others and suicidal ideation was not confirmed. Also, the results indicated a relatively different role of family and friends in creating suicidal thoughts. However, increased social support from PSS-Fa and PSS-Fr can prevent suicidal thoughts. Kim et al. (2023) also found that increased PSS and a sense of social cohesion may be critical in preventing suicide among adolescents.

It seems that different dimensions of social health, including social cohesion, social belonging, etc. interact with social support as protective factors for suicide. According to the psychosocial theory of Albox 1930 (Kleiman & Liu, 2013) of suicide, the act of suicide should be considered from two different angles, individual causes and social causes. Social communication is a key element in the suicide process. Simultaneously thwarted belongingness, i.e. the feeling of not belonging to a group, and the perceived burdensomeness, i.e. the feeling of being a burden to others, are at the root of the emergence of suicidal thoughts. The simultaneous presence of the cognitive factors of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness leads to the emergence of the desire to commit suicide. Suicidal desire may develop into attempted suicide by acquiring the ability to commit suicide, often through repeated suicide attempts. Several studies investigated and confirmed these theoretical models. The results of the current research also confirm these theoretical models. According to the results of the present study, teenagers living in SWO centers may feel social isolation. They may feel that they are not part of the community and do not share themselves with others who make up social reality. Social isolation also means the failure of personal and social support relationships; therefore, teenagers who have lower social health (low social cohesion, high social alienation, and isolation), have lower PSS, do not feel close to their community, and do not consider their social group a source of comfort. These characteristics increase their vulnerability to psychological pressures and life challenges. With the increase in the experience of mental pressure, mood problems, etc. the risk of suicidal thoughts increases in turn.

It also seems that the feeling of not belonging or not having social solidarity and cohesion can lead to negative feelings, despair, depression, and even suicidal thoughts. A psychological interpersonal perspective suggests that suicidality stems from two main risk factors, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness. Thwarted belongingness includes feelings of loneliness, lack of mutual care, and separation from others. On the other hand, the perceived burdensomeness is characterized by self-hatred and the feeling that one is a burden to family, friends, and society. Adolescents living in SWO centers may have higher scores in each of these constructs. This group of population may feel isolated from other social groups, and considered a burden to the family or society, thus increasing the risk of suicidal thoughts by increasing negative emotions and depression. In addition to thwarted belongingness and lack of social solidarity, living in SWO centers may deprive teenagers of establishing a satisfactory level of social interaction (one of the important dimensions of social health). According to Goss et al. (2022), the inability to maintain a satisfactory level of social interaction can affect a person’s perception of social support, undermine core life values, and lead to emotional dysregulation, which in turn increases the risk of suicidal thoughts. As a result, living in SWO centers reduces PSS in adolescents by reducing SH and social interaction; decreased PSS is also associated with increased suicidal thoughts. Research has shown a strong relationship between social support and suicide (Hussein & Yousef, 2024), social isolation and suicide, as well as a relationship between perceived burden and suicidal behavior (Ahmadboukani et al., 2022). Therefore, it seems that a combination of low SH, low PSS, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness, along with feelings of hopelessness, can lead to active suicidal tendencies. Passive suicidal thoughts may come from thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, but it is the added desperation and despair that can drive a person to action. When these factors come together, they can turn suicidal thoughts into actual behavior. Therefore, it is the combination of these factors that ultimately leads to suicidal acts, not just the presence of one factor alone.

Conclusion

Based on the results, it can be concluded that there the is negative and significant relationship between social health and suicidal thoughts, between finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts, and between perceived social support and suicidal thoughts in adolescents covered by the SWO in Iran. Therefore, the presence of meaning in life, social health, and perceived social support can reduce the suicidal thoughts in these vulnerable age groups and can act as protective factors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Science, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Rezvaneh Namazi Yousefi, approved by the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.CTB.REC.1402.167).

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the State Welfare Organization of Iran officials for their permission to enter the care centers and collect data, and the personnel of these centers and all teenagers who participated in this study for their cooperation.

References

Adolescents are one of the crucial social groups that experience many difficulties and damages due to the current social characteristics and the characteristics of adolescence. The way of life and habits of adolescence sometimes lasts until the end of life, and therefore the problems caused by it affect a lifetime rather than returning to just one period. Knowing the social factors affecting the health of adolescents helps to understand adolescence in the context of society (Ibrahimpour et al., 2019). Adolescence is a period in which a fifth of the world’s population is located, and 85% of this population of 1.2 billion live in developing countries. Every year, one million teenagers die due to accidents, suicide, violence, and complications related to preventable and treatable diseases.

According to the estimate of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017), the cause of 70% of deaths are behaviors that were created in adolescence and can be corrected. Every year, four million teenagers commit suicide, and one hundred thousand of them lead to death (Parvizi et al., 2004).

Suicide is one of the most complex human behaviors in which a person intentionally ends his life. According to WHO, more than 800 thousand people kill themselves every year (Rezaeian & Behzad, 2017). Research on suicide examines two crucial phenomena, which include suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Mortier et al., 2018). Since suicide is a major public health problem in adolescents and also in the older age of the world’s population, not only deaths due to suicide but also suicidal thoughts and attempted suicide are many events in adolescence and youth (Rezaeian & Behzad, 2017). Therefore, the importance of paying attention and dealing with this critical issue (suicide) doubles. Suicide is a multi-step process, including suicidal thoughts, suicide planning, suicide attempts, and action to end life (Hayes et al., 2020). Suicidal thoughts include preoccupation with nothingness and the desire to die (Falcone et al., 2018). Therefore, suicidal thoughts are the first step to end life and one of the predictors of suicide (Wang et al., 2019).

Social health is a function of various social and cultural factors that play a crucial role in ensuring the dynamism and efficiency of any society. Also, a critical condition for the growth and prosperity of any society is the existence of knowledgeable, efficient, and creative people (Shouichi et al., 2014). Today, the concept of social health, according to its various definitions and dimensions, is the coordination between values, interests, and attitudes in the field of action of people in society, and as a result, realistic and purposeful planning for life (Chaichi Tabrizi & Ragha Baf Shali, 2014). Social health is a concept that refers to the relationship between the two concepts of health and society. Considering that the community itself is a valid concept and its external truth depends on every person who formed it; therefore, in examining the community, above all, the people of the society should be studied. Another predictor of suicidal thoughts is finding meaning in life, which is highlighted during adolescence and the emergence of adulthood (Steger, 2012).

Understanding social support is more crucial than receiving it. In other words, a person’s understanding and attitude towards the received support is more crucial than the amount of support provided to him (Abdolazimi & Niknam, 2018). Also, in the classification of dimensions and people related to perceived social support (PSS), it is stated that PSS includes the help and support of family (PSS-Fa), friends (PSS-Fr), and other crucial people in life, which a person understands according to his/her social and personal conditions (Sadri et al., 2018).

The theorists of this field believe that social support relationships are considered by a person as an available and appropriate resource to meet her needs (Clara et al., 2003). Social support is studied in two forms, received (objective) social support (RSS) and perceived (subjective) social support (PSS) (Shang et al., 2022). In PSS, the individual’s evaluations of the availability of support when necessary and needed are examined (Gulachet, 2010). In other words, PSS is a person’s perception or experience of being loved, cared for, respected, and valued and made part of a social network with assistance and commitments to count (Taylor et al., 2004). Understanding the PSS is more crucial than receiving it. In other words, a person’s pain and attitude towards the support received is more crucial than the amount of support provided to the person. One of the psychological features that are vital in adolescence is social support. Social support refers to a mental feeling of belonging, being accepted, and being loved. Support is a relationship for every person and creates a sense of intimacy and closeness. Social support is a two-way help that creates a positive image of the individual, self-acceptance, and a feeling of love and worth. All these features give a person the opportunity for self-actualization and growth (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018).

Based on what has been said, the present study aims to answer this question, does the gender factor moderate the relationship between social health and finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts in adolescents covered by State Welfare Organization (SWO), considering the mediating role of PSS?

Materials and Methods

The current research is applied and the research method is descriptive correlational design. The research design in this study is the structural equation modeling (SEM) design. The statistical population of this research included all the boys and girls living in day care and night care centers for the SWO in 2023, Tehran, Iran. Due to the large size of the statistical population and the impossibility of accessing and obtaining permission to enter all quasi-family centers (juvenile detention centers), a multistage random sampling technique was used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included 15 to 18 years old, not being unsupervised or poorly supervised, and living in SWO centers. The exclusion criteria included suffering from mental illnesses and receiving drug therapy and psychotherapy interventions.

Procedures

Ask suicide-screening questions (ASQ)

The ASQ is a 15-item self-report suicide risk–screening measure and was designed by Olson (1984). Its main purpose is to evaluate the tendency or probability of suicide in teenagers. Each question has two options. The yes option gets a score of one and the no option gets a score of zero. Of course, this scoring method will be reversed for questions 1, 5, and 11. In adolescents who have a strong desire to commit suicide, the answers will be as follows:

1. No, 2. Yes, 3. Yes, 4. Yes, 5. No, 6. Yes, 7. Yes, 8. Yes, 9. Yes, 10. Yes, 11. No, 12. Yes, 13. Yes.

Noori (2010) found the validity of the questionnaire to be 0.65. Also, the reliability of the ASQ in teenagers was calculated using Cronbach’s α method equal to 0.69, which indicates the acceptable reliability of this questionnaire (Gatezadeh & Zhmadi, 2019)

Keyes’s social well-being questionnaire (KSWBQ)

To KSWBQ was implemented. The Keyes questionnaire. (1998) questionnaire has 20 questions and its purpose is to investigate the level of social health from different dimensions (social health, social prosperity, social cohesion, social acceptance, and social participation). The response range is of the Likert type, and the score for each option is (1. I completely disagree, 2. I disagree, 3. I have no opinion, 4. I agree, 5. I completely agree). Of course, this marking method is reversed for questions number 3, 5, 6, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and is as follows: (5. I completely disagree, 4. I disagree, 3. I have no opinion, 2. I agree, 1. I completely agree). The social health questionnaire has five dimensions, questions 1-4 are related to the dimension of social prosperity, questions 5-7 are related to social solidarity, questions 8-10 are related to social cohesion, questions 11-15 are related to social acceptance, and questions 16-20 are related to social participation. Joshenlou et al. have standardized the validity and reliability of the Keyes health questionnaire, including social health, mental and emotional health, using exploratory factor analysis, correlation analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The value of Cronbach’s α under the scales of social health was 0.59 to 0.76, and the value of Cronbach’s α for sub-scales of emotional health was between 0.43 and 0.6 (Joshanloo et al., 2006). The validity of this questionnaire has been obtained by its creators above 0.70 (keyes & Shapiro, 2004).

The meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

Steger et al. (2006) created the MLQ. It has 10 items, which include two subscales, the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. They consist of five items each. The presence of meaning subscale measures how fully respondents feel their lives are of meaning. The subscale of the presence of meaning includes these items, I understand the meaning of my life, I have found a satisfying purpose for my life, my life has a clear sense of purpose, I am looking for something that makes my life meaningful, I am looking for a purpose and ideal for my life. The search for meaning subscale measures how engaged and motivated respondents are in efforts to find meaning or deepen their understanding of meaning in their lives. The search for meaning subscale includes the following items, in my life I have a clear sense of purpose, I have a good feeling that something gives meaning to my life, I have always been looking for a purpose for my life, I have always been looking for something that gives meaning to my feeling of life, I am looking to find a purpose for my life. The MLQ assesses two dimensions of meaning in life using 10 items rated on a seven-point scale from “absolutely true” to “absolutely untrue.” The total scores of questions 2, 3, 7, 8, and 10 determine the level of a person’s effort to find meaning and the total scores of questions 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9 (question 9 with reverse coding) determine the level of meaningfulness of a person’s life. The MLQ has good reliability, test re-test stability, stable factor structure, and convergence among informants. According to Steger et al. (2006) internal consistency was good for the presence (0.86) and search (0.87) subscales. Also, the reliability was good for the presence (0.7) and search (0.73) subscales. The test and re-test reliability of MLQ in Iran was 0.84 for the presence subscale and 0.74 for the search subscale (Ostad, 2008).

Multidimensional scale of PSS (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988)

The multidimensional scale of PSS (MSPSS) is a 12-item instrument and measures social support from three sources, family, community, and friends on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum and maximum scores of the individual on the whole scale are 12 and 84, respectively, and in each of the family, social, and friend support subscales, 4 and 28 respectively. A higher score indicates greater PSS. The psychometric properties of the MSPSS have been confirmed in worldwide research. In a preliminary study, the psychometric properties of this scale in 742 samples of Iranian students and general population, 311 students, 431 general populations, Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated for the whole scale and the items of the three subscales of family (PSS-Fa), friends (PSS-Fr), and other crucial people in life, were 0.91, 0.87, 0.83 and 0.89. These coefficients confirmed the internal consistency of the multidimensional scale of PSS (Beshart, 2019).

Results

In the present study, 320 teenagers living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO (155 girls and 165 boys) participated with the Mean±SD of the age group for girls and boys equal to 15.70 and 1.35 years, respectively. Table 1 presents the Mean±SD, and correlation coefficients between the variables of finding meaning in life, social health, PSS, and suicidal thoughts. As shown in Table 1, the correlation between the variables was in the expected direction and consistent with the theories of the research field.

Univariate normal distribution

In this research, to evaluate the assumption of univariate normal distribution, Kurtosis, and skewness of the variables and to evaluate the assumption of collinearity of values, variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient were investigated (Table 2).

As shown in Table 2, the Kurtosis and Skewness values of all components are in the range of ±2. This indicates that the assumption of univariate normal distribution among the data is valid (Kline, 2023). Also, as shown in Table 2, the assumption of collinearity was valid among the data of the current research. Because the tolerance coefficient values of predictor variables were larger than 0.1 and the VIF values of each of them were smaller than 10. According to Myers et al. (2006), the tolerance coefficient is less than 0.1 and the value of the VIF is higher than 10, indicating that the assumption of collinearity is not established.

Multivariate normal distribution (MND)

In this research, to evaluate the establishment or non-establishment of the assumption of MND, the information analysis related to “the Mahalanobis distance” was used. The values of skewness and Kurtosis were obtained as 1.03 and 0.94, respectively. Therefore, the value of both indices was in the range of ±2, confirming the assumption of MND among the data. Finally, to evaluate the homogeneity of variances, the scatter diagram of the standardized residuals of the errors was examined and the evaluations showed that the assumption is also valid among the data.

Model analysis

Model specification

In the research measurement model, 10 indicators were considered to reflect 3 existing structures. According to Figure 1, it is assumed that indicators of social prosperity, social solidarity, social cohesion, social acceptance, and social participation measure the latent variable of social health. On the other hand, the indicators of the presence of meaning and the search for meaning measure the latent variable of finding meaning in life.

Also, indicators of PSS-Fa, PSS-Fr, and PSS-others measure the latent variable of PSS. The measurement model fit was assessed using CFA, AMOS software, version 24, and maximum likelihood estimation. Table 3 shows the fit indices of measurement and structural models.

Table 3 shows that all fit indices obtained from CFA support the acceptable measurement model fit with the collected data. In the measurement model fit, the largest factor load belonged to the presence of the meaning indicator (β=0.952) and the smallest factor load belonged to the social participation indicator (β=0.516). Thus, considering that the factor loadings of all indicators were greater than 0.32, it can be said that all of them had the necessary power to measure the current research variables.

Structural model

Following the evaluation of the measurement model fit, in the second stage, the fit indices of SEM were estimated and evaluated. In the SEM, it was assumed that finding meaning in life and social health are related to the mediation of PSS with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO. Table 3 presents that the fit indices obtained from the analysis support the range of acceptable values of SEM with the collected data. Table 4 presents the path coefficients (PCs) in the SEM.

Table 4 shows that the PC (direct and indirect PC) between finding meaning in life (β=-0.354, P=0.001) and social health (β=-0.546, P=0.001) was negative and significant with suicidal thoughts. Also, The PC between PSS and suicidal thoughts was negative and significant (P=0.001, β=0.458). The indirect PC between finding meaning in life (β=-0.148, P=0.001) and social health (β=-0.246, P=0.001) with suicidal thoughts were negative and significant. This result shows that in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO, the PSS mediates the relationship between finding meaning in life and social health with suicidal thoughts in a negative and significant way. Figure 1 shows the standard parameters in the SEM of the research.

Figure 1 shows the standard parameters in the research model. As shown, the sum of squared multiple correlation (R2) for suicidal thoughts was equal to 0.62. This shows that the suicidal thoughts factors of finding meaning in life, social health, and PSS explain 62% of the variance of suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO.

Discussion

First hypothesis: Social health is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in living in centers covered by Tehran’s SWO

The results showed that the PC between social health and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that social health has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO. So far, many researchers have not investigated the relationship between social health and suicidal thoughts. However, few studies have examined the components of social health (such as social solidarity and social participation) with suicidal thoughts. These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Gill et al., 2023; Nakhaei et al., 2023; Erlangen et al., 2023; Lutzman et al., 2021; Fukai et al., 2020; Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017).

Research results show that greater social solidarity reduces the possibility of suicidal thoughts (Gill et al., 2023; Nakhaei et al., 2023).

Erlangsen et al. (2023) by investigating the relationship between mental, physical, and social health measures with death caused by suicide and self-harm, showed that the existence of an active social network reduces the rate of suicide and self-harm. Also, increasing the risk of deciding and attempting suicide is more related to decreasing mental, physical, and social health, and increasing dependent personality disorder and psychological distress. Lutzman et al., (2021) found that older single men who experience physical pain may experience more loneliness and less social cohesion, factors that may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts. Goss et al. (2022) showed that social participation acts as a predictor of pathological thoughts and suicidal thoughts among the elderly population. Being in the environment and social events and relationships with colleagues and friends have protective effects against sick and suicidal thoughts. Social health status has a significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in men (but not women) and negative social health can predict the development of suicidal thoughts in men (Fukai et al., 2020). A negative and significant relationship is observed between social health and students’ suicidal thoughts; therefore with increasing social health, students’ suicidal thoughts decrease (Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017).

According to the integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018), the development of suicidal thoughts depends on motivational moderators that can enhance or weaken suicidal intent, including a sense of belonging, a sense of connection with others, a sense of heaviness, and belief in being a shouldering the burden of society. The weakness and intensity of these moderators may lead the individual to consider suicidal thoughts as the most possible solution (Gill et al., 2023). Concepts, such as feelings of social disconnection, a sense of loss of belonging, and perceived burdensomeness are central components in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (Joyner, 2009), suggesting that both interpersonal relationships and psychological characteristics, in interaction with the feeling of hopelessness, help the formation and development of suicidal thoughts (Heapy et al., 2024). It is possible that a person while having a deep sense of connection with other people, at the same time considers himself shouldering the burden of others. Therefore, several aspects of social connections, including perceived strength and quality of interpersonal relationships, and frequency of interaction with others, highlight the importance of the role of social relationships and social health in general as a known protective factor against suicidal thoughts. In particular, suicidal thoughts can be considered as a crucial predictor for transition to suicide attempt and mortality.

The results support the decrease in the frequency and quality of social communication in people with suicidal thoughts (Heapy et al., 2024). Perceptions of social isolation, being alone, and the expectation of being alone exacerbate suicidal thoughts (Gill et al., 2023). People who experience high suicidal thoughts, whether these thoughts are caused by their living environment or their inner concerns, experience a higher feeling of unhappiness, ineffectiveness, and dissatisfaction. They often feel insecure, incompetent, and alone, and find themselves powerless to solve their problems. People with suicidal thoughts believe that they will never achieve relative peace and comfort (Nakhaei et al., 2023). Improving social health through receiving and improving support networks, family support, participating in social and group activities, stress management, and learning to ask for help from others when needed is known to be useful in preventing suicidal thoughts (Fukai et al., 2020). Therefore, in line with the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (Joyner, 2009; Heapy et al., 2024), it is possible that increasing the sense of belonging and decreasing the perception of being a shouldering the burden of others is a crucial intervention strategy to weaken the link between distress and suicidal thoughts.

Social health is one of the influencing factors in the occurrence of high-risk behaviors in teenagers (Basharpoor & Samadifard, 2017). In explaining this result, it can be said that high social health in teenagers increases their general health and psychological well-being. As a result, it helps to improve the feeling of satisfaction with life and reduces the tendency to nurture and strengthen suicidal thoughts. Adolescence is a period of liberation from dependence on parents and independence in various aspects of life. The future success of young people largely depends on the support of adults and institutions, such as family, schools, and community structures. Therefore, any disconnection between individuals and society can create conditions that strengthen harmful behaviors, such as suicidal thoughts. Extreme individualism, where personal desires override social ties, can contribute to this disconnect. It is essential for people to feel participation and acceptance in social structures; an experience that can prevent possible social deviations, such as suicidal thoughts in them. Social health can help reduce suicidal thoughts and improve mental health by creating a supportive environment and fostering positive relationships. This is crucial for teenagers who are forced to live in SWO centers and are deprived of the experience of living with their parents. Living in such an environment, which is associated with lack of PSS-Fa, lack of receiving affection, disorder in the formation of attachment, poor mental health, depression, low self-efficacy, social adjustment, and lower self-esteem, plays a crucial role in the tendency to high-risk behaviors, such as suicidal thoughts and actions in teenagers. This group of people in society is probably deprived of the existence of support and social networks that help to reduce the feeling of loneliness and the possibility of receiving emotional and practical support in difficult times. In addition, the lack of parental support may endanger equipping them with adapting coping strategies in facing life challenges and deprive them of communication and social skills. As a result, the lack of access to the social network and a sense of belonging may lead them to risky thoughts, such as suicidal thoughts in the face of obstacles in life.

Second hypothesis: Finding meaning in life is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO

The results showed that the PC between finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that finding meaning in life has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO.

These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Cetın et al., 2024; Gu et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2022; Marco et al., 2015; Garvier et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Costanza et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2018; Sadri Damirchi et al., 2019; Borji et al., 2018).

Cetın et al., (2024) showed that low levels of meaning in life, hope, and social support have a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts and increase the probability of using psychiatric drugs to attempt suicide in nursing students. According to Gu et al. (2023), finding meaning in life and positive and negative emotions show distinct and complex links with the three dimensions of suicidal thoughts (pessimism, sleep, and despair). Finding meaning in life and positive emotions act as a protective shield against suicidal thoughts. Sun et al., 2022, showed that although finding meaning in life does not have a direct and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts, finding meaning in life through depression has the strongest relationship with suicidal thoughts. Finding meaning in life moderates the relationship between suicidal thoughts, hopelessness, and borderline symptoms in individuals with eating disorders (Marco et al., 2015). Finding meaning in life by increasing positive emotions can reduce suicidal thoughts (Garvier et al., 2020). (Liu et al., 2021) showed that finding meaning in life has a significant and negative relationship with suicidal thoughts and behavior in students. In a systematic review, Costanza et al., (2019) found that finding meaning in life is a protective factor against suicidal thoughts and behavior. Tan et al., (2018) also found that finding meaning in life partially mediates the relationship between mental health status and the severity of suicidal thoughts. Specifically, students who experience poorer mental health status may be more likely to report having a poorer sense of meaning in life, which in turn increases suicidal thoughts. Yarian and Ameri (2020) showed a negative and significant relationship between finding meaning in life and suicidal thoughts in the elderly. The presence of meaning in life leads to an increase in suicidal thoughts in students by reducing the initially incompatible schemas. Therefore, finding meaning in life is a protective factor against the risk of suicide in students (Borji et al., 2018). Sadri Demirchi et al. (2020) also showed that finding meaning in life and coping strategies can explain and predict suicidal thoughts in the elderly.

Finding meaning in life includes one’s values, experiences, goals, and beliefs, and has an inverse relationship with depression, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts (Sun et al., 2022). Finding meaning in life is considered a strong resilience factor (Costanza et al., 2019). People who feel confused about the meaning of life are prone to despair and suicidal thoughts. Individuals who reported having suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months were more likely to attempt suicide in the next 12 months (Gu et al., 2023). Among the two dimensions of finding meaning in life, the search and the presence of meaning in life, and the presence of meaning in life may be the main and key factor to prevent suicide, while the search for the meaning of life may predict suicidal thoughts (Liu et al., 2021). Otto et al. (2016) found that having meaningful moments in life can reduce frustration. Thus, meaning in life may act as a barrier against various factors that fuel suicidal thoughts, such as bullying victimization, psychological stress, hopelessness, and loss of sense of belonging.

Gu et al. (2023) showed the existence of a complex interaction between emotion, the meaning of life, and suicidal thoughts. Their results showed that negative affect is related to despair, low sleep quality, and pessimism dimensions in suicidal thoughts. Consistent with the results of Guo et al., the close relationship between finding meaning in life and emotions shows that emotions can indirectly affect suicidal thoughts and emphasizes their importance as common factors affecting suicidal thoughts. The presence of meaning in life, by helping to strengthen and improve hope, promotes mental well-being and reduces the feeling of hopelessness. The existence of ideals and values can give meaning to a difficult life and increase the sense of duty and responsibility. Finding meaning in life can help people choose a set of appropriate goals, experience a sense of agency, and accept themselves. Probably, even in the face of failure, such a person can consider more suitable paths and move forward with more hope. The destructive effect of a sense of meaninglessness can leave people feeling what Frankel called existential existential vacuum or existential frustration (Frankel, 1969).

Finding meaning in the lives of teenagers who live in care centers can have a great impact on their mental health. Therefore, in the absence of this meaning, the possibility of suicidal thoughts increases. The presence of meaning in the lives of those who feel less belonging to others may be a factor for the emergence of suicidal thoughts and even suicide attempts with frequent traumatic experiences, feelings of aimlessness, loneliness, isolation, lack of hope for the future, and feelings of worthlessness. Therefore, providing opportunities to create meaning and purpose in the lives of this group of teenagers can help reduce the risk of suicidal thoughts and improve their mental health.

Third hypothesis: PSS is related to suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO

The results showed that the PC between PSS and suicidal thoughts is negative and significant. Therefore, in the test of the first hypothesis, it was concluded that PSS has a negative and significant relationship with suicidal thoughts in adolescents living in centers covered by SWO.

These results are consistent with the results of other researchers (Hussein & Yousef, 2024; Hofmeier et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2024; Du et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022; Arab et al. (2024); Maleki et al., 2022).

Hoffmeier et al. (2017) showed that PSS provides greater protection against suicidal thoughts for people with lower levels of mental health symptoms. Huang et al., (2024) showed that negative judgments can devalue healthcare trainees’ work, thereby creating a psychological burden that is associated with emotional exhaustion, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts. Du et al., (2021) by examining 818 studies found a negative and significant relationship between social support and suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. They also emphasized the key role of social support in preventing suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. Zhao et al., (2022) showed that PSS-Fa, and PSS-Fr, but not teachers, were inversely related to suicidal ideation in rural Chinese children experiencing rejection by others. Arab et al. (2024) showed a significant negative relationship between PSS and suicidal thoughts in high school students. Maleki et al., (2022) also support the existence of a significant negative correlation between the components of social support and life satisfaction with suicidal thoughts in students.

About half of patients who attempt or die by suicide do not disclose suicidal ideation (Rainbow et al., 2023). Thus, higher levels of psychological distress can lead to increased isolation and social withdrawal as a way to express distress. Reduced interaction with others can cause feelings of loneliness (Hofmeier et al., 2017). Consistent with these results, it seems that the risk of suicide is lower when a person has more social connections, and this emphasizes the importance of social support. However, Gill et al., (2023) believe that people experiencing distress and suicidal thoughts may hesitate to seek help for fear of not being understood by their loved ones. According to these results, for teenagers who are deprived of the possibility of receiving PSS-Fa and siblings due to their living conditions, having a strong relationship with a group can help increase the sense of belonging in people and promote the feeling of personal worth. Also, the existence of efficient social relations provides access to wider sources of social support. In such an environment, people can monitor each other’s behavior and have positive effects on each other’s psychological well-being.

Those with lifetime suicidal thoughts reported significantly less support from their family and felt more dissatisfied with this level of support (Hussein & Yousef, 2024). It seems that the ability to share thoughts and the knowledge that someone is available when needed reduces people’s feelings of loneliness. Talking about suicidal thoughts and the reactions and judgments of others can be difficult, daunting, and scary. Because people may be afraid of others’ evaluation of themselves. People around them may also think that asking more about suicidal thoughts will lead teenagers to commit suicide more. However, Huang et al., (2024) believe that asking people about suicidal thoughts helps to better understand what is happening and make a more informed decision. According to Zhao et al., (2022), talking about suicidal thoughts with a child or teenager does not lead to the development of suicidal ideas and does not increase the risk of committing suicide.