Volume 12, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

PCP 2024, 12(4): 297-306 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khanipour H, Yarahmadi F. Countertransference Conceptualization From Freud to Era of Evidence-based Psychotherapies: A Conceptual Review. PCP 2024; 12 (4) :297-306

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-947-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-947-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Institute for Educational, Psychological and Social Research, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. , h.khanipour@khu.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 636 kb]

(4872 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2983 Views)

Full-Text: (3587 Views)

Introduction

The primary goal of psychotherapy is to aid individuals in dealing with intrapersonal and interpersonal difficulties and reaching higher levels of self-understanding and self-actualization. The therapist should be someone who is not burdened by these challenges or has effectively addressed them. Nevertheless, the occurrence of emotional responses within therapy is a prevalent and defining aspect of this particular relationship. Countertransference is a phenomenon that often manifests in therapeutic relationships, influencing treatment outcomes (Gelso et al., 2002) and the mental health of psychotherapists (Hoshanghi et al., 2023). Several studies have indicated a significant relationship between unmanaged countertransference reactions and unfavorable treatment results (Rocco et al., 2022; Tishby et al., 2022; Gelso & Kline, 2022). Conversely, effective management of countertransference has been linked to positive treatment outcomes, facilitating improvements in mental health processes, such as self-awareness, self-integration, empathy, and anxiety control (Hayes et al., 2018). Studies indicate that over 80% of psychotherapists assessed by their colleagues have reported experiencing countertransference (Hayes et al., 1998). Throughout the history of psychotherapy, countertransference has been conceptualized in various ways. This article was conducted to examine the conceptualization of countertransference from different viewpoints, including its causes and predictors, consequences, measurement tools, and management.

Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted using a conceptual review approach, focusing on psychotherapeutic theories concerning countertransference. Data for this review was sourced from research literature, spanning from classic psychoanalytic works of the early 20th century to more recent theories and works in the field from 1960 to 2023. The search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. The inclusion criteria included research articles with these conditions, the article should not be a review one, the research ought to be conducted with a group of psychotherapists as the sample, and the study should employ specific quantitative or qualitative methods to assess countertransference. The selection of theoretical research sources was informed by the writings of Freud and modern psychoanalysts who have contributed to the literature on countertransference. The keywords used for article selection were “countertransference”, “psychotherapy”, and “psychoanalysis”. Two researchers conducted the data collection process. A total of 14 studies met the research criteria outlined in the predictors section, while 15 articles were examined in the countertransference tools section, and 12 articles were analyzed in the countertransference management methods section. Conceptual review studies typically aim to achieve four primary goals, analyzing the extent and key concerns within a specific research field, elucidating the rationale behind conducting the study, synthesizing previous research and organizing it into categories, and pinpointing the constraints of prior studies and offering recommendations to fill research voids in that domain (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

Results

Classical psychoanalysis perspective

Countertransference is defined in various ways. Initially, Freud introduced the classic definition, which involves the therapist’s unconscious and psychopathological reactions to the patient’s transference, stemming from the therapist’s unresolved conflicts (Freud, 1958). Essentially, patient transference triggers the analyst’s unresolved childhood conflicts, hinders the analyst’s comprehension of the patient, and leads to behaviors that cater to the therapist’s needs rather than the patient’s needs. Traditionally, the classic view on countertransference was negative, viewing it as a barrier to effective therapy and a factor that hampers the therapist’s unbiased understanding of the patient (Gabbard, 2001). According to Freud, the analysts’ vulnerabilities and resistances can impede their success; thus, it is crucial to prevent countertransference from occurring (Gabbard, 2001).

A holistic approach to countertransference

After Freud, a group of scholars, including Heimann, Fromm, and Kiesler directed their attention towards positive transference and regarded the therapist’s emotional reactions as a means to comprehend the patient’s internal dynamics (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). They put forth a broader concept known as “total countertransference,” encompassing all interactions between therapist and patient, whether conscious or unconscious, conflict-driven or reality-based, and in response to transference or other stimuli. The total countertransference definition reduced the significance of the therapist’s internal conflicts and placed greater importance on the patient’s transference issues (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002). Scholars, such as Kiesler, Sandler, and Ogden have proposed concepts similar to countertransference, such as projection identification, and role-responsiveness, in which patients inadvertently ensnare the therapist (Kiesler, 1979; Sandler, 1976; Ogden, 1992). Projection identification, initially proposed by Klein, is a defense mechanism linked to the countertransference process (Klein, 1946). During projection identification, the patient projects undesirable aspects of the self onto the therapist, leading the therapist to behave based on those projections, and then the patient identifies with the therapist and internalizes these characteristics (Summers, 2014; Ogden, 1992). Projection identification can also appear as an idealization countertransference, expressed as positive feedback toward the therapist (Ogden, 1992). Patients idealize their desirable aspects onto others to protect these parts from destruction by their pathological parts (Ogden, 1992). The concept of role responsiveness means that at times during therapy, the therapist’s responses are derived from a role that the patient has assigned to them. In this process, the patient places the therapist in a complementary role in addition to the primary role they play themselves during therapy, based on their defenses. Therefore, the unusual responses observed by the analyst may stem from being placed in a role that the patient has prepared for them (Summers, 2014).

Process-oriented approach toward countertransference

The overemphasis on the patient’s involvement in the holistic approach to countertransference has been criticized, as it can lead to placing blame on patients (Gabbard, 2001). A new definition of countertransference, known as the unified model or process model, was introduced in response to these criticisms. This model represents a middle ground between classic and holistic definitions (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). Regarding these criticisms, a new definition of countertransference was put forward, referred to as the unified model or process-oriented model of countertransference. This new definition represents a middle ground between classic and holistic definitions (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). According to this new definition, countertransference encompasses all the therapist’s reactions toward the clients based on unresolved internal conflicts. This definition seems more comprehensive because it recognizes that countertransference can be conscious or unconscious, and can be in response to the transference or any other phenomenon in the relationship between therapist and patients (Hayes & Gelso, 2001).

According to this definition, countertransference can be divided into objective and subjective (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). Objective countertransference involves consistent and universal reactions, while subjective countertransference entails specific reactions that are influenced by the therapists’ psychological dynamics (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). It essentially triggers certain aspects of the patient’s behavior, and the therapist’s unresolved issues, and elicits particular patterns of behavior and emotions. Therefore, based on this definition, countertransference is a shared outcome of the patient and therapist. In this perspective, countertransference is expressed as thoughts and behaviors, which can be both conscious and unconscious and have dual positive and negative effects on the treatment process (Faut, 2006).

The process approach categorizes countertransference into five parts, origins, triggers, manifestations, effects, and management (Hayes, 1995). Origins involve unresolved therapeutic issues and conflicts that lead to countertransference responses (Hayes, 1995). Triggers refer to events that affect the therapist’s internal wounds during treatment, such as patient issues and complaints (Hayes, 1995). Origins and triggers are considered as the cause of the countertransference. Manifestations include the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses that the therapist experiences when provoking her unsolved problems (Hayes, 1995). Effects relate to the outcome of therapist countertransference responses in the treatment process and outcome (Hayes, 1995). Management refers to the therapist’s ability to be aware of and interact with these responses in a way that minimizes their negative impact on the treatment (Hayes, 1995). This structural framework for classifying processes related to countertransference is the vital experimental framework that countertransference studies have used in various psychotherapy approaches (Hayes et al., 2018; Colli, et al., 2022; Hayes et al., 2015; Tishby et al., 2022; Abargil &Tishby, 2022).

Measurement and types of countertransference

The abstract nature of countertransference has posed challenges in terms of operational measurement and definition (Hofsess & Tracey, 2010). Despite this, researchers have made significant efforts to develop tools and methods to address this issue. Early experimental studies explored countertransference using simulated therapy session scenarios involving a therapist and a client (Yulis & Kieser, 1968; Faut, 2006). These studies presented two different types of responses, avoiding the topic brought up by the therapist, and addressing and focusing on the topic (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). The first response was considered a form of defensive behavior and a potential countertransference experience (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). Therapists were asked to choose between two responses when presented with audio tapes of patients: “Are you feeling angry?” or “Are you mad at me?” (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). Also, Albert Bandura was among the first behavior therapists who tried to explain countertransference using behavioral concepts. He categorized the therapist’s management of countertransference into two groups, inductive behaviors (such as affirmation, exploration, stimulation, reflection, and labeling) and reactive behaviors (such as non-affirmation, changing the subject, remaining silent, and ignoring) (Bandura et al., 1960). In another definition, countertransference has been conceptualized as the therapist’s distorted perception of the patient (McClure & Hodge, 1987). Another method, although time-consuming, views countertransference as avoidance behavior that can be identified by professional evaluators (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002).

In addition to focused observation methods, self-reporting tools, and questionnaires are also available to assess countertransference. These include the countertransference behavior index, the avoidance index questionnaire, the therapist response questionnaire, the countertransference management scale, the countertransference behavior chart, the countertransference predictor, the hostility deterrence scale, the 58-question list of emotional words, the countertransference measurement scale, the message effectiveness chart, the countertransference index, the referent-therapist emotional attitudes rating scale, and the countertransference -related factors scale (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002; Zittle Conklin & Weston, 2003; Tanzley et al., 2016; Parth et al., 2017; Tanzilli et al., 2017; Hofsess & Tracey, 2010; Macado et al., 2014).

The therapeutic response questionnaire (Tanzilli et al., 2016) is a commonly utilized tool in this area, encompassing various aspects of countertransference. It defines countertransference as the therapist’s uncontrollable reactions that disrupt the treatment process, leading to negative emotional responses and the therapist’s withdrawal (Tanzilli et al., 2016). The 9 dimensions of countertransference are grounded on the following 9 dimensions, helpless/inadequate, overwhelmed/disorganized, positive/happy transference, hostility/anger, criticized/mistreated, special/overinvolved, parental/protective, sexualized, and disengaged and emotional apathy (Tanzilli et al., 2016). Research conducted by Tanzilli et al. has shown a significant relationship between the reporting of certain aspects of countertransference in a questionnaire and the diagnosis of specific personality disorders. For example, cluster A personality disorders were associated with the criticized/mistreated dimension, cluster B personality disorders were associated with the overwhelmed/disorganized dimension, and cluster C personality disorders were associated with the parental/protective dimension.

Predictors of countertransference

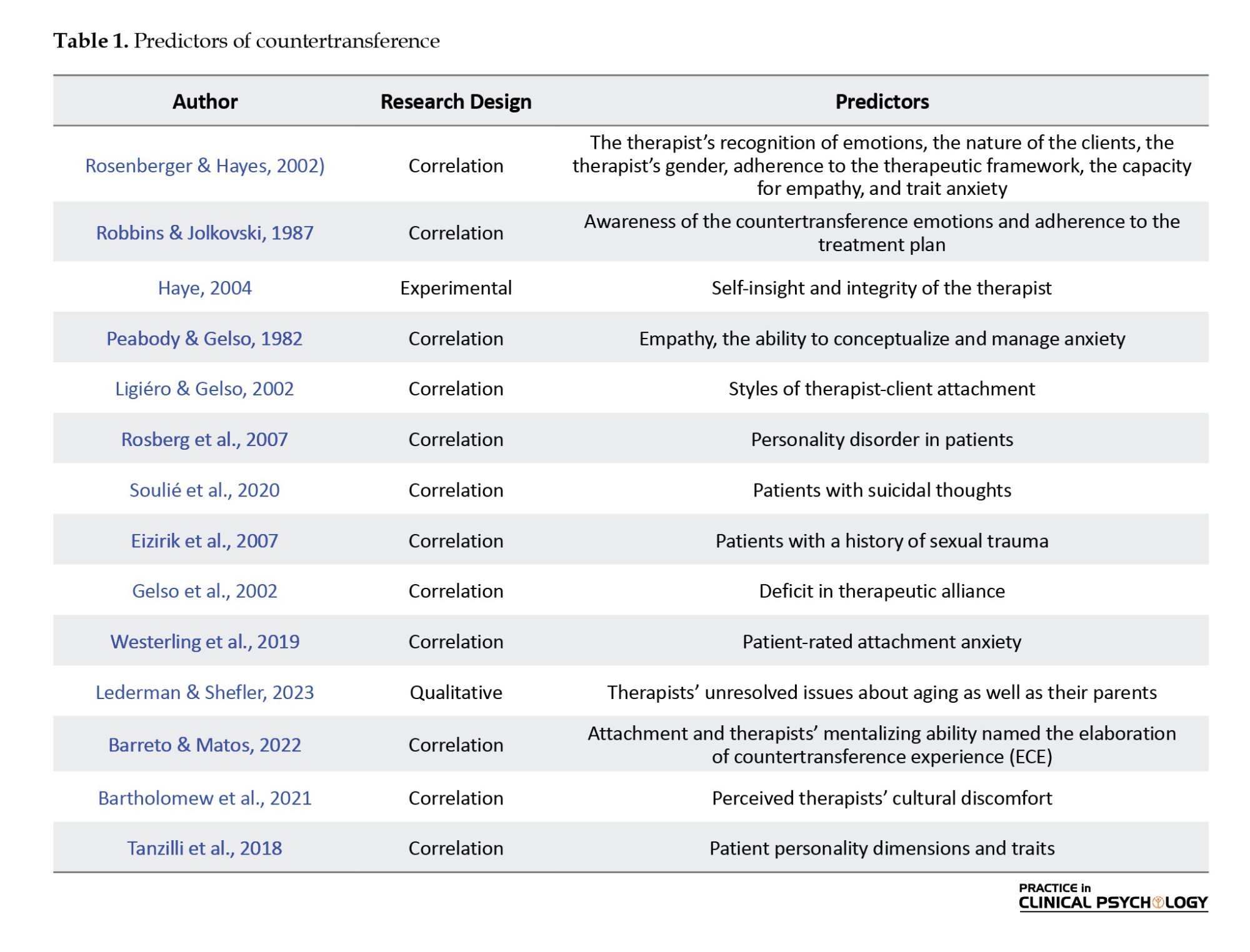

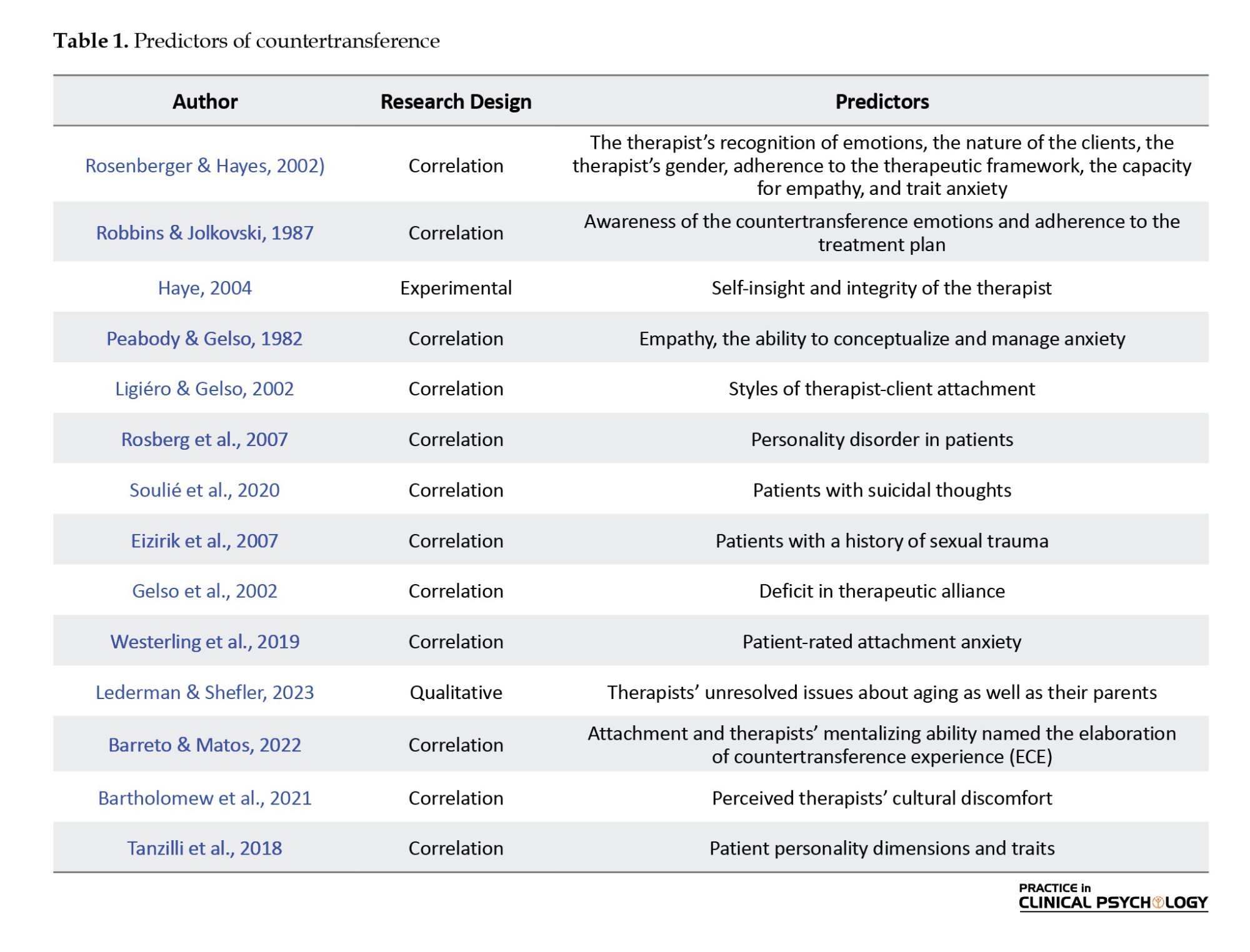

The analysis of research studies concerning predictors of countertransference revealed a set of factors, detailed in Table 1. These factors can be organized into three main categories, those associated with the therapist, including aspects, such as training level, mentalizing capacity, and self-awareness, patient-specific characteristics, such as attachment styles and diagnostic categories, and cultural elements, which encompass the cultural alignment between the therapist and the patient. Studies that have rep licated treatment sessions by broadcasting scenarios of therapist-client interactions have revealed several factors that serve as precursors to countertransference feelings and behaviors. These factors encompass the therapist’s recognition of emotions, the clients’ nature (seductive or aggressive versus neutral clients), the therapist’s gender, adherence to the therapeutic framework, the capacity for empathy, and trait anxiety (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). A two-step model for predicting countertransference has been proposed based on the study of predicting countertransference patterns (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). This model suggests that countertransference behaviors are contingent on the interplay between awareness of the countertransference emotions and adherence to the treatment plan (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). In other words, if the therapist strictly adheres to the therapeutic framework but is unaware of the countertransference emotions, the likelihood of a countertransference-based behavioral response is high (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). An alternative approach to forecasting the consequences of countertransference involves examining the impact of self-insight and integrity on the therapist (Hayes, 2004). By defining self-awareness as the therapist’s awareness of their internal conflicts and integrity as the resolution of these conflicts, four possible combinations emerge, high self-insight/high integrity, high self-insight/low integrity, low self-insight/high integrity, low self-insight/low integrity (Hayes, 2004). The most favorable outcome is the first combination, leading to positive treatment outcomes, while the least favorable is the last combination, which may result in acting out behaviors. Therefore, predicting countertransference rates for therapists relies on their level of self-awareness regarding internal conflicts and the resolution of these conflicts (Hayes, 2004).

A review of the research literature on predicting countertransference has identified several factors, summarized as follows: Empathy, the ability to conceptualize and manage anxiety (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987; Peabody & Gelso, 1982); styles of therapist-client attachment (Ligiéro & Gelso, 2002); the distinctive effect of personality patterns of clusters A and B in patients (Rosberg et al., 2007). Also according to the process model of countertransference (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002), the origins of countertransference were family issues, needs and values, and cultural differences. In addition, triggers of countertransference include the content of client issues, comparison of client status with others by the therapist, changes in the structure and treatment plan, and assessment of progress by the therapist (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002; Hayes et al., 1998); patients with suicidal thoughts (Soulié et al., 2020); patients with a history of sexual trauma (Eizirik et al., 2007); patients with substance use disorders (Najavits et al., 1995) and deficit in therapeutic alliance (Gelso et al., 2002). Although these studies have examined the predictors of countertransference separately, there appears to be an interaction between the sources of the predictors of countertransference, and a combination of the therapist’s demographic and personality characteristics, the way the treatment is structured, and the personality and diagnostic characteristics of the clients, can predict the occurrence of countertransference in the therapist and ultimately the actions and behaviors towards countertransference feelings.

Management of countertransference

All of the psychotherapy approaches advocate managing countertransference. Two distinct approaches have been recognized in the realm of managing countertransference. The initial approach focuses on diminishing the chances of countertransference reactions, while the second approach concentrates on preventing and lessening the adverse effects of countertransference reactions on the treatment process (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). The competencies that prove effective in both approaches for managing countertransference reactions are the same competencies outlined in the tools to evaluate countertransference reactions. Two particular crucial competencies have been identified one being self-awareness and the other being the ability to apply treatment theory into clinical practice. Only when an individual excels in both areas can they effectively handle countertransference reactions (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). As for the second approach, which involves mitigating the impact of countertransference in treatment post-occurrence, insufficient empirical evidence is observed in this domain to elucidate how addressing these issues in treatment can enhance the treatment process for which patients and under what circumstances. However, certain specific results suggest that addressing such issues can strengthen the therapeutic bond, diminish power differentials between the therapist and the patient, and foster a shared understanding of psychological issues for the patient (Hayes & Gelso, 2001).

Utilizing self-report questionnaires and behavioral checklists has been a common approach to managing countertransference. Various assessment tools, such as the countertransference factors inventory (Van Wagoner et al., 1991) and the management strategies list (Fauth & Williams, 2005), have been utilized in research studies. The countertransference factors inventory (Van Wagoner et al., 1991) consists of five dimensions, including self-integration, self-insight, conceptual ability, anxiety management ability, and empathy. However, a drawback of this tool is that therapists often do not report the actions taken during sessions that they believe are crucial for management. As a result, alternative tools like the management strategies list (Fauth & Williams, 2005) have been developed to identify the strategies employed by therapists in managing countertransference through open-ended inquiries.

Countertransference issues have been investigated in cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), with different expressions noted, including heightened positive and negative emotions towards clients, overly supportive therapist behavior, admiration, aggressive and hostile actions towards clients, competitive mindsets, distrustful conduct, erotic or lustful behaviors, and arrogant and belittling interactions (Leahy, 2003; Prasko et al., 2022). In CBT, countertransference is understood as cognitive schemas that therapists must be conscious of, along with specific emotions that therapists should investigate to better understand patients’ unique maladaptive beliefs (Prasko et al., 2022). Cognitive behavior therapists are encouraged to allocate time outside of sessions to reflect on their emotional reactions to patients, reasons for welcoming or rejecting patients, and issues they are reluctant to discuss (Leahy, 2003). Additionally, strategies, such as clinical supervision, guided discovery, role-playing, and addressing cognitive interpretations underlying countertransference feelings have been proposed to manage countertransference in CBT (Prasko et al., 2010).

An alternative formal approach to managing countertransference is through the clinical supervision process (Ladany et al., 2000). However, research has indicated that countertransference can impact the clinical supervision process, even affecting the supervisor during high-stress sessions with the therapist and patient, as well as the therapist’s relationship with the supervisor and the relationships between supervisors (Ladany et al., 2000). A study on countertransference in clinical supervision situations (Falender & Shafranske, 2014) has highlighted the differentiation between objective countertransference (arising from the patient’s behavioral, cognitive, and emotional patterns) and subjective countertransference (resulting from the therapist’s traits). The most comprehensive approach to manage countertransference in clinical supervision involves identifying the components of the countertransference creation process and dividing it into four stages, identifying indicators of countertransference-related events, focusing on elements involved in the countertransference experience, normalization of the experience, focusing on creating collaboration, and resolution (Ponton & Sauerheber, 2014). Insight-based methods, creating coherence in the therapist, conceptualization, and framing of the countertransference experience are suggested for each stage (Ponton & Sauerheber, 2014).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the conceptualization of countertransference, exploring ways to measure countertransference, identifying predictors of countertransference, and describe general methods of managing countertransference. Three approaches, including classical, holistic, and process-oriented, were distinguished in defining countertransference. The process-oriented approach has allocated the most empirical research in this area, and studies related to the measurement methods of countertransference have also been mostly based on this theoretical pattern. In contrast, the classical approach attributes countertransference entirely to the therapist’s unresolved conflicts. However, in the holistic approach, the primary source of countertransference stems from the patient, particularly through the process of projective identification. On the other hand, the process-oriented approach categorizes the origins of countertransference into two main types, objective and subjective issues. Here, countertransference is viewed as a result of the dynamic interaction between the patient and the therapist. Additionally, the definition of countertransference within the process-oriented framework is more detached from any single theoretical perspective, adopting a trans-theoretical viewpoint.

Processes related to countertransference can be categorized into five categories, including origins, triggers, emotional, cognitive and behavioral manifestations, consequences, and management of countertransference reactions. Two models for measuring countertransference are simulation studies of therapy sessions and self-report tools. Most articles with countertransference as a key world lead to self-report questionnaires that have been made and validated among different languages. The vital predictors of countertransference are classified into three categories, therapist personality factors, patient-related factors, and process-related cultural or contextual factors. Regarding the methods of managing countertransference reactions, some factor has critical role, including self-insight, integrity, the ability to transform theory into practice, emotional awareness, and clinical supervision.

The results of this study indicate that countertransference serves as a significant diagnostic indicator as well as a potential barrier to effective treatment. The outcome of this dynamic is contingent upon the clinical expertise of the therapist and their awareness of personal conflicts and vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the results highlight that the notion of countertransference has been integrated into the behavioral assessment of psychotherapy, with relevant measurement tools developed in recent years.

This study points out several limitations in this field. Firstly, the cultural differences in the interpretation of feelings and behaviors related to countertransference have not been extensively studied. Secondly, participants’ responses may be biased by cultural or personal issues in studies that only used self-report questionnaires to assess countertransference. Lastly, the lack of exploration into countertransference experiences among therapists at different stages of their careers highlights the need for theories to explain how novice and professional psychotherapists manage countertransference. To address these limitations, this study suggests focusing on countertransference issues in psychotherapy education in Iran, examining the impact of cultural, gender, and socioeconomic factors on countertransference, and conducting field studies based on the process-oriented model of countertransference.

Conclusion

The therapists initially responded to countertransference by denial and had skeptical attitudes. However, there was a notable evolution in this perspective, leading to a broader acknowledgment and becoming a common aspect of study in all psychotherapy tests. This shift facilitated its substantial integration into differential diagnoses and the development of therapeutic strategies. In contrast, neglecting countertransference, which can present in cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and physiological forms, can significantly impair the effectiveness of therapeutic methods. The relational theory model posits a holistic view of countertransference, representing projective identification and role-responsiveness as its primary concepts. The therapy process-oriented model further suggests that significant predictors of countertransference include the therapist's family issues, personal values and needs, as well as cultural differences between therapist and client. Moreover, various factors can trigger countertransference during therapy sessions, including what the client talked about, comparing the client with others, changes in the therapy procedures, and any disruptions in the therapeutic alliance between therapist and client that may arise during the session.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a conceptual review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Hamid Khanipour; Methodology: Hamid Khanipour; Data collection, investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Reference

The primary goal of psychotherapy is to aid individuals in dealing with intrapersonal and interpersonal difficulties and reaching higher levels of self-understanding and self-actualization. The therapist should be someone who is not burdened by these challenges or has effectively addressed them. Nevertheless, the occurrence of emotional responses within therapy is a prevalent and defining aspect of this particular relationship. Countertransference is a phenomenon that often manifests in therapeutic relationships, influencing treatment outcomes (Gelso et al., 2002) and the mental health of psychotherapists (Hoshanghi et al., 2023). Several studies have indicated a significant relationship between unmanaged countertransference reactions and unfavorable treatment results (Rocco et al., 2022; Tishby et al., 2022; Gelso & Kline, 2022). Conversely, effective management of countertransference has been linked to positive treatment outcomes, facilitating improvements in mental health processes, such as self-awareness, self-integration, empathy, and anxiety control (Hayes et al., 2018). Studies indicate that over 80% of psychotherapists assessed by their colleagues have reported experiencing countertransference (Hayes et al., 1998). Throughout the history of psychotherapy, countertransference has been conceptualized in various ways. This article was conducted to examine the conceptualization of countertransference from different viewpoints, including its causes and predictors, consequences, measurement tools, and management.

Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted using a conceptual review approach, focusing on psychotherapeutic theories concerning countertransference. Data for this review was sourced from research literature, spanning from classic psychoanalytic works of the early 20th century to more recent theories and works in the field from 1960 to 2023. The search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. The inclusion criteria included research articles with these conditions, the article should not be a review one, the research ought to be conducted with a group of psychotherapists as the sample, and the study should employ specific quantitative or qualitative methods to assess countertransference. The selection of theoretical research sources was informed by the writings of Freud and modern psychoanalysts who have contributed to the literature on countertransference. The keywords used for article selection were “countertransference”, “psychotherapy”, and “psychoanalysis”. Two researchers conducted the data collection process. A total of 14 studies met the research criteria outlined in the predictors section, while 15 articles were examined in the countertransference tools section, and 12 articles were analyzed in the countertransference management methods section. Conceptual review studies typically aim to achieve four primary goals, analyzing the extent and key concerns within a specific research field, elucidating the rationale behind conducting the study, synthesizing previous research and organizing it into categories, and pinpointing the constraints of prior studies and offering recommendations to fill research voids in that domain (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

Results

Classical psychoanalysis perspective

Countertransference is defined in various ways. Initially, Freud introduced the classic definition, which involves the therapist’s unconscious and psychopathological reactions to the patient’s transference, stemming from the therapist’s unresolved conflicts (Freud, 1958). Essentially, patient transference triggers the analyst’s unresolved childhood conflicts, hinders the analyst’s comprehension of the patient, and leads to behaviors that cater to the therapist’s needs rather than the patient’s needs. Traditionally, the classic view on countertransference was negative, viewing it as a barrier to effective therapy and a factor that hampers the therapist’s unbiased understanding of the patient (Gabbard, 2001). According to Freud, the analysts’ vulnerabilities and resistances can impede their success; thus, it is crucial to prevent countertransference from occurring (Gabbard, 2001).

A holistic approach to countertransference

After Freud, a group of scholars, including Heimann, Fromm, and Kiesler directed their attention towards positive transference and regarded the therapist’s emotional reactions as a means to comprehend the patient’s internal dynamics (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). They put forth a broader concept known as “total countertransference,” encompassing all interactions between therapist and patient, whether conscious or unconscious, conflict-driven or reality-based, and in response to transference or other stimuli. The total countertransference definition reduced the significance of the therapist’s internal conflicts and placed greater importance on the patient’s transference issues (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002). Scholars, such as Kiesler, Sandler, and Ogden have proposed concepts similar to countertransference, such as projection identification, and role-responsiveness, in which patients inadvertently ensnare the therapist (Kiesler, 1979; Sandler, 1976; Ogden, 1992). Projection identification, initially proposed by Klein, is a defense mechanism linked to the countertransference process (Klein, 1946). During projection identification, the patient projects undesirable aspects of the self onto the therapist, leading the therapist to behave based on those projections, and then the patient identifies with the therapist and internalizes these characteristics (Summers, 2014; Ogden, 1992). Projection identification can also appear as an idealization countertransference, expressed as positive feedback toward the therapist (Ogden, 1992). Patients idealize their desirable aspects onto others to protect these parts from destruction by their pathological parts (Ogden, 1992). The concept of role responsiveness means that at times during therapy, the therapist’s responses are derived from a role that the patient has assigned to them. In this process, the patient places the therapist in a complementary role in addition to the primary role they play themselves during therapy, based on their defenses. Therefore, the unusual responses observed by the analyst may stem from being placed in a role that the patient has prepared for them (Summers, 2014).

Process-oriented approach toward countertransference

The overemphasis on the patient’s involvement in the holistic approach to countertransference has been criticized, as it can lead to placing blame on patients (Gabbard, 2001). A new definition of countertransference, known as the unified model or process model, was introduced in response to these criticisms. This model represents a middle ground between classic and holistic definitions (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). Regarding these criticisms, a new definition of countertransference was put forward, referred to as the unified model or process-oriented model of countertransference. This new definition represents a middle ground between classic and holistic definitions (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). According to this new definition, countertransference encompasses all the therapist’s reactions toward the clients based on unresolved internal conflicts. This definition seems more comprehensive because it recognizes that countertransference can be conscious or unconscious, and can be in response to the transference or any other phenomenon in the relationship between therapist and patients (Hayes & Gelso, 2001).

According to this definition, countertransference can be divided into objective and subjective (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). Objective countertransference involves consistent and universal reactions, while subjective countertransference entails specific reactions that are influenced by the therapists’ psychological dynamics (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). It essentially triggers certain aspects of the patient’s behavior, and the therapist’s unresolved issues, and elicits particular patterns of behavior and emotions. Therefore, based on this definition, countertransference is a shared outcome of the patient and therapist. In this perspective, countertransference is expressed as thoughts and behaviors, which can be both conscious and unconscious and have dual positive and negative effects on the treatment process (Faut, 2006).

The process approach categorizes countertransference into five parts, origins, triggers, manifestations, effects, and management (Hayes, 1995). Origins involve unresolved therapeutic issues and conflicts that lead to countertransference responses (Hayes, 1995). Triggers refer to events that affect the therapist’s internal wounds during treatment, such as patient issues and complaints (Hayes, 1995). Origins and triggers are considered as the cause of the countertransference. Manifestations include the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses that the therapist experiences when provoking her unsolved problems (Hayes, 1995). Effects relate to the outcome of therapist countertransference responses in the treatment process and outcome (Hayes, 1995). Management refers to the therapist’s ability to be aware of and interact with these responses in a way that minimizes their negative impact on the treatment (Hayes, 1995). This structural framework for classifying processes related to countertransference is the vital experimental framework that countertransference studies have used in various psychotherapy approaches (Hayes et al., 2018; Colli, et al., 2022; Hayes et al., 2015; Tishby et al., 2022; Abargil &Tishby, 2022).

Measurement and types of countertransference

The abstract nature of countertransference has posed challenges in terms of operational measurement and definition (Hofsess & Tracey, 2010). Despite this, researchers have made significant efforts to develop tools and methods to address this issue. Early experimental studies explored countertransference using simulated therapy session scenarios involving a therapist and a client (Yulis & Kieser, 1968; Faut, 2006). These studies presented two different types of responses, avoiding the topic brought up by the therapist, and addressing and focusing on the topic (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). The first response was considered a form of defensive behavior and a potential countertransference experience (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). Therapists were asked to choose between two responses when presented with audio tapes of patients: “Are you feeling angry?” or “Are you mad at me?” (Yulis & Kieser, 1968). Also, Albert Bandura was among the first behavior therapists who tried to explain countertransference using behavioral concepts. He categorized the therapist’s management of countertransference into two groups, inductive behaviors (such as affirmation, exploration, stimulation, reflection, and labeling) and reactive behaviors (such as non-affirmation, changing the subject, remaining silent, and ignoring) (Bandura et al., 1960). In another definition, countertransference has been conceptualized as the therapist’s distorted perception of the patient (McClure & Hodge, 1987). Another method, although time-consuming, views countertransference as avoidance behavior that can be identified by professional evaluators (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002).

In addition to focused observation methods, self-reporting tools, and questionnaires are also available to assess countertransference. These include the countertransference behavior index, the avoidance index questionnaire, the therapist response questionnaire, the countertransference management scale, the countertransference behavior chart, the countertransference predictor, the hostility deterrence scale, the 58-question list of emotional words, the countertransference measurement scale, the message effectiveness chart, the countertransference index, the referent-therapist emotional attitudes rating scale, and the countertransference -related factors scale (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002; Zittle Conklin & Weston, 2003; Tanzley et al., 2016; Parth et al., 2017; Tanzilli et al., 2017; Hofsess & Tracey, 2010; Macado et al., 2014).

The therapeutic response questionnaire (Tanzilli et al., 2016) is a commonly utilized tool in this area, encompassing various aspects of countertransference. It defines countertransference as the therapist’s uncontrollable reactions that disrupt the treatment process, leading to negative emotional responses and the therapist’s withdrawal (Tanzilli et al., 2016). The 9 dimensions of countertransference are grounded on the following 9 dimensions, helpless/inadequate, overwhelmed/disorganized, positive/happy transference, hostility/anger, criticized/mistreated, special/overinvolved, parental/protective, sexualized, and disengaged and emotional apathy (Tanzilli et al., 2016). Research conducted by Tanzilli et al. has shown a significant relationship between the reporting of certain aspects of countertransference in a questionnaire and the diagnosis of specific personality disorders. For example, cluster A personality disorders were associated with the criticized/mistreated dimension, cluster B personality disorders were associated with the overwhelmed/disorganized dimension, and cluster C personality disorders were associated with the parental/protective dimension.

Predictors of countertransference

The analysis of research studies concerning predictors of countertransference revealed a set of factors, detailed in Table 1. These factors can be organized into three main categories, those associated with the therapist, including aspects, such as training level, mentalizing capacity, and self-awareness, patient-specific characteristics, such as attachment styles and diagnostic categories, and cultural elements, which encompass the cultural alignment between the therapist and the patient. Studies that have rep licated treatment sessions by broadcasting scenarios of therapist-client interactions have revealed several factors that serve as precursors to countertransference feelings and behaviors. These factors encompass the therapist’s recognition of emotions, the clients’ nature (seductive or aggressive versus neutral clients), the therapist’s gender, adherence to the therapeutic framework, the capacity for empathy, and trait anxiety (Rosenberger & Hayes, 2002). A two-step model for predicting countertransference has been proposed based on the study of predicting countertransference patterns (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). This model suggests that countertransference behaviors are contingent on the interplay between awareness of the countertransference emotions and adherence to the treatment plan (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). In other words, if the therapist strictly adheres to the therapeutic framework but is unaware of the countertransference emotions, the likelihood of a countertransference-based behavioral response is high (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987). An alternative approach to forecasting the consequences of countertransference involves examining the impact of self-insight and integrity on the therapist (Hayes, 2004). By defining self-awareness as the therapist’s awareness of their internal conflicts and integrity as the resolution of these conflicts, four possible combinations emerge, high self-insight/high integrity, high self-insight/low integrity, low self-insight/high integrity, low self-insight/low integrity (Hayes, 2004). The most favorable outcome is the first combination, leading to positive treatment outcomes, while the least favorable is the last combination, which may result in acting out behaviors. Therefore, predicting countertransference rates for therapists relies on their level of self-awareness regarding internal conflicts and the resolution of these conflicts (Hayes, 2004).

A review of the research literature on predicting countertransference has identified several factors, summarized as follows: Empathy, the ability to conceptualize and manage anxiety (Robbins & Jolkovski, 1987; Peabody & Gelso, 1982); styles of therapist-client attachment (Ligiéro & Gelso, 2002); the distinctive effect of personality patterns of clusters A and B in patients (Rosberg et al., 2007). Also according to the process model of countertransference (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002), the origins of countertransference were family issues, needs and values, and cultural differences. In addition, triggers of countertransference include the content of client issues, comparison of client status with others by the therapist, changes in the structure and treatment plan, and assessment of progress by the therapist (Rosenberg & Hayes, 2002; Hayes et al., 1998); patients with suicidal thoughts (Soulié et al., 2020); patients with a history of sexual trauma (Eizirik et al., 2007); patients with substance use disorders (Najavits et al., 1995) and deficit in therapeutic alliance (Gelso et al., 2002). Although these studies have examined the predictors of countertransference separately, there appears to be an interaction between the sources of the predictors of countertransference, and a combination of the therapist’s demographic and personality characteristics, the way the treatment is structured, and the personality and diagnostic characteristics of the clients, can predict the occurrence of countertransference in the therapist and ultimately the actions and behaviors towards countertransference feelings.

Management of countertransference

All of the psychotherapy approaches advocate managing countertransference. Two distinct approaches have been recognized in the realm of managing countertransference. The initial approach focuses on diminishing the chances of countertransference reactions, while the second approach concentrates on preventing and lessening the adverse effects of countertransference reactions on the treatment process (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). The competencies that prove effective in both approaches for managing countertransference reactions are the same competencies outlined in the tools to evaluate countertransference reactions. Two particular crucial competencies have been identified one being self-awareness and the other being the ability to apply treatment theory into clinical practice. Only when an individual excels in both areas can they effectively handle countertransference reactions (Hayes & Gelso, 2001). As for the second approach, which involves mitigating the impact of countertransference in treatment post-occurrence, insufficient empirical evidence is observed in this domain to elucidate how addressing these issues in treatment can enhance the treatment process for which patients and under what circumstances. However, certain specific results suggest that addressing such issues can strengthen the therapeutic bond, diminish power differentials between the therapist and the patient, and foster a shared understanding of psychological issues for the patient (Hayes & Gelso, 2001).

Utilizing self-report questionnaires and behavioral checklists has been a common approach to managing countertransference. Various assessment tools, such as the countertransference factors inventory (Van Wagoner et al., 1991) and the management strategies list (Fauth & Williams, 2005), have been utilized in research studies. The countertransference factors inventory (Van Wagoner et al., 1991) consists of five dimensions, including self-integration, self-insight, conceptual ability, anxiety management ability, and empathy. However, a drawback of this tool is that therapists often do not report the actions taken during sessions that they believe are crucial for management. As a result, alternative tools like the management strategies list (Fauth & Williams, 2005) have been developed to identify the strategies employed by therapists in managing countertransference through open-ended inquiries.

Countertransference issues have been investigated in cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), with different expressions noted, including heightened positive and negative emotions towards clients, overly supportive therapist behavior, admiration, aggressive and hostile actions towards clients, competitive mindsets, distrustful conduct, erotic or lustful behaviors, and arrogant and belittling interactions (Leahy, 2003; Prasko et al., 2022). In CBT, countertransference is understood as cognitive schemas that therapists must be conscious of, along with specific emotions that therapists should investigate to better understand patients’ unique maladaptive beliefs (Prasko et al., 2022). Cognitive behavior therapists are encouraged to allocate time outside of sessions to reflect on their emotional reactions to patients, reasons for welcoming or rejecting patients, and issues they are reluctant to discuss (Leahy, 2003). Additionally, strategies, such as clinical supervision, guided discovery, role-playing, and addressing cognitive interpretations underlying countertransference feelings have been proposed to manage countertransference in CBT (Prasko et al., 2010).

An alternative formal approach to managing countertransference is through the clinical supervision process (Ladany et al., 2000). However, research has indicated that countertransference can impact the clinical supervision process, even affecting the supervisor during high-stress sessions with the therapist and patient, as well as the therapist’s relationship with the supervisor and the relationships between supervisors (Ladany et al., 2000). A study on countertransference in clinical supervision situations (Falender & Shafranske, 2014) has highlighted the differentiation between objective countertransference (arising from the patient’s behavioral, cognitive, and emotional patterns) and subjective countertransference (resulting from the therapist’s traits). The most comprehensive approach to manage countertransference in clinical supervision involves identifying the components of the countertransference creation process and dividing it into four stages, identifying indicators of countertransference-related events, focusing on elements involved in the countertransference experience, normalization of the experience, focusing on creating collaboration, and resolution (Ponton & Sauerheber, 2014). Insight-based methods, creating coherence in the therapist, conceptualization, and framing of the countertransference experience are suggested for each stage (Ponton & Sauerheber, 2014).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the conceptualization of countertransference, exploring ways to measure countertransference, identifying predictors of countertransference, and describe general methods of managing countertransference. Three approaches, including classical, holistic, and process-oriented, were distinguished in defining countertransference. The process-oriented approach has allocated the most empirical research in this area, and studies related to the measurement methods of countertransference have also been mostly based on this theoretical pattern. In contrast, the classical approach attributes countertransference entirely to the therapist’s unresolved conflicts. However, in the holistic approach, the primary source of countertransference stems from the patient, particularly through the process of projective identification. On the other hand, the process-oriented approach categorizes the origins of countertransference into two main types, objective and subjective issues. Here, countertransference is viewed as a result of the dynamic interaction between the patient and the therapist. Additionally, the definition of countertransference within the process-oriented framework is more detached from any single theoretical perspective, adopting a trans-theoretical viewpoint.

Processes related to countertransference can be categorized into five categories, including origins, triggers, emotional, cognitive and behavioral manifestations, consequences, and management of countertransference reactions. Two models for measuring countertransference are simulation studies of therapy sessions and self-report tools. Most articles with countertransference as a key world lead to self-report questionnaires that have been made and validated among different languages. The vital predictors of countertransference are classified into three categories, therapist personality factors, patient-related factors, and process-related cultural or contextual factors. Regarding the methods of managing countertransference reactions, some factor has critical role, including self-insight, integrity, the ability to transform theory into practice, emotional awareness, and clinical supervision.

The results of this study indicate that countertransference serves as a significant diagnostic indicator as well as a potential barrier to effective treatment. The outcome of this dynamic is contingent upon the clinical expertise of the therapist and their awareness of personal conflicts and vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the results highlight that the notion of countertransference has been integrated into the behavioral assessment of psychotherapy, with relevant measurement tools developed in recent years.

This study points out several limitations in this field. Firstly, the cultural differences in the interpretation of feelings and behaviors related to countertransference have not been extensively studied. Secondly, participants’ responses may be biased by cultural or personal issues in studies that only used self-report questionnaires to assess countertransference. Lastly, the lack of exploration into countertransference experiences among therapists at different stages of their careers highlights the need for theories to explain how novice and professional psychotherapists manage countertransference. To address these limitations, this study suggests focusing on countertransference issues in psychotherapy education in Iran, examining the impact of cultural, gender, and socioeconomic factors on countertransference, and conducting field studies based on the process-oriented model of countertransference.

Conclusion

The therapists initially responded to countertransference by denial and had skeptical attitudes. However, there was a notable evolution in this perspective, leading to a broader acknowledgment and becoming a common aspect of study in all psychotherapy tests. This shift facilitated its substantial integration into differential diagnoses and the development of therapeutic strategies. In contrast, neglecting countertransference, which can present in cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and physiological forms, can significantly impair the effectiveness of therapeutic methods. The relational theory model posits a holistic view of countertransference, representing projective identification and role-responsiveness as its primary concepts. The therapy process-oriented model further suggests that significant predictors of countertransference include the therapist's family issues, personal values and needs, as well as cultural differences between therapist and client. Moreover, various factors can trigger countertransference during therapy sessions, including what the client talked about, comparing the client with others, changes in the therapy procedures, and any disruptions in the therapeutic alliance between therapist and client that may arise during the session.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a conceptual review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Hamid Khanipour; Methodology: Hamid Khanipour; Data collection, investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Reference

Abargil, M., & Tishby, O. (2022). Countertransference awareness and treatment outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(5), 667-677. [DOI:10.1037/cou0000620] [PMID]

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. [DOI:10.1080/1364557032000119616]

Bandura, A., Lipsher, D. H., & Miller, P. E. (1960). Psychotherapists approach-avoidance reactions to patients’ expressions of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(1), 1-8. [DOI:10.1037/h0043403]

Barreto, J. F., & Matos, P. M. (2022). Attachment mismatches and alliance: Through the pitfalls of mentalizing countertransference. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 39(3), 276-279. [DOI:10.1037/pap0000410]

Bartholomew, T. T., Pérez-Rojas, A. E., Lockard, A. J., Joy, E. E., Robbins, K. A., & Kang, E., et al. (2021). Therapists’ cultural comfort and clients’ distress: An initial exploration. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 275-281. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000331] [PMID]

Colli, A., Gagliardini, G., & Gullo, S. (2022). Countertransference responses mediate the relationship between patients’ overall defense functioning and therapists’ interventions. Psychotherapy Research, 32(1), 32(1), 45–58. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2021.1884768] [PMID]

Lederman, S., & Shefler, G. (2023). You can’t treat older people without “getting old” yourself: A grounded theory analysis of countertransference in psychotherapy with older adults. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 54(5), 352-360. [DOI:10.1037/pro0000523]

Eizirik, M., Polanczyk, G., Schestatsky, S., Jaeger, M. A., & Ceitlin, L. H. F. (2007). Countertransference in the initial care of victims of sexual and urban violence: A qualitative-quantitative research. Revista de Psiquiatria do Rio Grande do Sul, 29(2), 197-204. [DOI:10.1590/S0101-81082007000200011]

Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2014). Clinical supervision: The state of the art. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(11), 1030-1041. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22124] [PMID]

Fauth, J. (2006). Toward more (and better) countertransference research. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 43(1), 16–31. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.43.1.16] [PMID]

Fauth, J., & Williams, E. N. (2005). The in-session self-awareness of therapist-trainees: Hindering or helpful? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 443-447. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.443]

Freud, S. (1958). [The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. In: S. Freud (Eds). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, (pp. 139-152). London: Hogarth Press. [Link]

Gabbard, G. O. (2001). A contemporary psychoanalytic model of countertransference. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(8), 983-991. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.1065] [PMID]

Gelso, C. J., Latts, M. G., Gomez, M. J., & Fassinger, R. E. (2002). Countertransference management and therapy outcome: An initial evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(7), 861-867. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.2010] [PMID]

Gelso, C. J., & Kline, K. V. (2022). Some directions for research and theory on countertransference. Psychotherapy Research, 32(1), 59–64. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2021.1968529] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A. (1995). Countertransference in group psychotherapy: Waking a sleeping dog. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 45(4), 521-535. [DOI:10.1080/00207284.1995.11491301] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A. (2004). The inner world of the psychotherapist: A program of research on countertransference. Psychotherapy Research, 14(1), 21-36. [DOI:10.1093/ptr/kph002] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A., & Gelso, C. J. (2001). Clinical implications of research on countertransference: Science informing practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(8), 1041-1051. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.1072] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A., Nelson, D. L. B., & Fauth, J. (2015). Countertransference in successful and unsuccessful cases of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 52(1), 127-133. [DOI:10.1037/a0038827] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A., Gelso, C. J., Goldberg, S., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2018). Countertransference management and effective psychotherapy: Meta-analytic findings. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 496-507. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000189] [PMID]

Hayes, J. A., McCracken, J. E., McClanahan, M. K., Hill, C. E., Harp, J. S., & Carozzoni, P. (1998). Therapist perspectives on countertransference: Qualitative data in search of a theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(4), 468-482. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.45.4.468]

Hofsess, C. D., & Tracey, T. J. G. (2010). Countertransference as a prototype: The development of a measure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 52-67. [DOI:10.1037/a0018111] [PMID]

Houshangi, H., Khanipour, H., & Farahani, M. N. (2023). Therapist attitudes and countertransference as predictors of professional quality of life and burnout among psychotherapists. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 23(2), 461-468. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12523]

Kiesler, D.J. (1979). An interpersonal communication analysis of relationship in psychotherapy. Psychiatry, 42, 299-311. [DOI:10.1080/00332747.1979.11024034]

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 27, 99–110. [PMID]

Ladany, N., Constantine, M. G., Miller, K., Erickson, C. D., & Muse-Burke, J. L. (2000). Supervisor countertransference: A qualitative investigation into its identification and description. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 102-115. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.102]

Leahy, R. L. (2003). Overcoming resistance in cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Publications. [Link]

Ligiéro, D. P., & Gelso, C. J. (2002). Countertransference, attachment, and the working alliance: The therapist’s contribution. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 39(1), 3-11. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.39.1.3]

Machado, D. D. B., Coelho, F. M. D. C., Giacomelli, A. D., Donassolo, M. A. L., Abitante, M. S., & Dall'Agnol, T., et al. (2014). Systematic review of studies about countertransference in adult psychotherapy. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 36(4), 173-185. [DOI:10.1590/2237-6089-2014-1004]

McClure, B. A., & Hodge, R. W. (1987). Measuring countertransference and attitude in therapeutic relationships. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 24(3), 325–335. [DOI:10.1037/h0085723]

Najavits, L. M., Griffin, M. L., Luborsky, L., Frank, A., Weiss, R. D., & Liese, B. S., et al. (1995). Therapists’ emotional reactions to substance abusers: A new questionnaire and initial findings. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 32(4), 669-677. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.32.4.669]

Ogden, T. H. (1992). Comments on transference and countertransference in the initial analytic meeting. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 12(2), 225-247. [DOI:10.1080/07351699209533894]

Parth, K., Datz, F., Seidman, C., & Löffler-Stastka, H. (2017). Transference and countertransference: A review. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 81(2), 167-211. [DOI:10.1521/bumc.2017.81.2.167] [PMID]

Peabody, S. A., & Gelso, C. J. (1982). Countertransference and empathy: The complex relationship between two divergent concepts in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29(3), 240-245. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.29.3.240]

Ponton, R. F., & Sauerheber, J. D. (2014). Supervisee countertransference: A holistic supervision approach. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53(4), 254-266. [DOI:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00061.x]

Prasko, J., Diveky, T., Grambal, A., Kamaradova, D., Mozny, P., & Sigmundova, Z., et al. (2010). Transference and countertransference in cognitive behavioral therapy. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, 154(3), 189–197. [DOI:10.5507/bp.2010.029] [PMID]

Prasko, J., Ociskova, M., Vanek, J., Burkauskas, J., Slepecky, M., & Bite, I., et al. (2022). Managing transference and countertransference in cognitive behavioral supervision: Theoretical framework and clinical application. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 2129–2155. [DOI:10.2147/PRBM.S369294] [PMID]

Robbins, S. B., & Jolkovski, M. P. (1987). Managing countertransference feelings: An interactional model using awareness of feeling and theoretical framework. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34(3), 276-282. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.34.3.276]

Rocco, D., De Bei, F., Negri, A., & Filipponi, L. (2021). The relationship between self-observed and other-observed countertransference and session outcome. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 301-309. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000356] [PMID]

Rosenberger, E. W., & Hayes, J. A. (2002). Therapist as subject: A review of the empirical countertransference literature. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(3), 264-270. [DOI:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00190.x]

Rossberg, J. I., Karterud, S., Pedersen, G., & Friis, S. (2007). An empirical study of countertransference reactions toward patients with personality disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(3), 225-230. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.02.002] [PMID]

Sandler, J. (1976). Countertransference and role-responsiveness. International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 3(1), 43-47. [Link]

Soulié, T., Bell, E., Jenkin, G., Sim, D., & Collings, S. (2020). Systematic exploration of countertransference phenomena in the treatment of patients at risk for suicide. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 24(1), 96–118. [DOI:10.1080/13811118.2018.1506844] [PMID]

Summers, F. (2014). Object relations theories and psychopathology: A comprehensive text. New York: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9781315803395]

Tanzilli, A., Colli, A., Del Corno, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2016). Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Therapist Response Questionnaire. Personality Disorders, 7(2), 147–158. [DOI:10.1037/per0000146] [PMID]

Tanzilli, A., Lingiardi, V., & Hilsenroth, M. (2018). Patient SWAP-200 personality dimensions and FFM traits: Do they predict therapist responses? Personality Disorders, 9(3), 250–262. [DOI:10.1037/per0000260] [PMID]

Tanzilli, A., Muzi, L., Ronningstam, E., & Lingiardi, V. (2017). Countertransference when working with narcissistic personality disorder: An empirical investigation. Psychotherapy, 54(2), 184-194. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000111]

Tishby, O., & Wiseman, H. (2022). Countertransference types and their relation to rupture and repair in the alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 32(1), 29-44. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2020.1862934] [PMID]

Van Wagoner, S. L., Gelso, C. J., Hayes, J. A., & Diemer, R. A. (1991). Countertransference and the reputedly excellent therapist. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 28(3), 411-421. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.28.3.411]

Westerling, T. W. III, Drinkwater, R., Laws, H., Stevens, H., Ortega, S., & Goodman, D., et al. (2019). Patient attachment and therapist countertransference in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36(1), 73-81. [DOI:10.1037/pap0000215]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Analytical approach

Received: 2024/07/20 | Accepted: 2024/09/23 | Published: 2024/10/1

Received: 2024/07/20 | Accepted: 2024/09/23 | Published: 2024/10/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |