Volume 11, Issue 4 (Autumn 2023)

PCP 2023, 11(4): 349-358 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Arzpeyma M, Hamzehpoor Haghighi T. Comparison of Object Relations, Personality Organization, and Personal and Relational Meaning of Life in Psychology Graduates vs Other Students in Lahijan Azad University. PCP 2023; 11 (4) :349-358

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-890-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-890-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Lahijan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Lahijan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Lahijan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Lahijan, Iran. ,Psy.hamzehpoor@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Lahijan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Lahijan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 567 kb]

(1406 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2967 Views)

Full-Text: (1321 Views)

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have shown that personal and psychological characteristics of therapists, such as gender, type of education, and selected approach, directly impact psychotherapy outcomes (Stadter, 2009). One of the vital characteristics is the therapist’s personality traits (Delgadillo et al., 2020). The therapist’s approach, the quality of the therapeutic alliance established during treatment, and the therapeutic outcomes are all directly influenced by the therapist’s personality traits (Topolinski & Hertel, 2007). Research has shown that three main personal characteristics determine the effectiveness of a psychotherapist’s work, the ability to create positive therapeutic alliances with a wide range of clients, which is a significant predictor of treatment outcomes, the development of extensive facilitative interpersonal skills that enable therapists to work with challenging and complex patients, and finally, the improvement of psychotherapeutic skills through extensive practice that addresses therapeutic shortcomings (Delgadillo et al., 2020). The personality characteristics of a psychotherapist is one of the most critical factors determining the psychotherapist’s selected approach (Tremblay et al., 1986) and according to Topolinski and Hertel’s research, play a crucial role in the therapeutic orientations and job satisfaction of psychologists (Topolinski & Hertel, 2007). One of the crucial personal characteristics of any human being is the level of object relations.

As all humans are born in an underdeveloped and dependent state, relying on others for their physiological and psychological survival, the need for relationships with others is considered one of the most fundamental human needs from infancy, and this forms the cornerstone of attachment theories or object relations (Stadter, 2009). Object relations have become one of the fundamental topics in psychology in recent decades (Diguer et al., 2004). From around 1950, profound changes in psychotherapeutic theories began, and the influence of interpersonal relationships and the underlying patterns of thinking and emotions on mental disorders were taken more seriously (Jamil et al., 2015). From the perspective of psychoanalytic theories, object relations are one of the factors that guarantee mental health and play a significant role in the occurrence of diseases and the formation of individuals’ personalities (Mesgarian et al., 2017). Despite the acceptance of many classic psychoanalytic concepts, object relations theorists consider the creation of ineffective intra-psychic structures of self and others and difficult relationships with parents in early childhood as the main factor in the occurrence of a wide range of mental disorders in adulthood (Fonagy et al., 2006).

Object relations are representations of self and others, accompanied by emotions, which indicate an individual’s capacity for interpersonal communication and the quality of these relationships (Kelly, 2014). The term object or object relation, first introduced by Freud in psychology, refers to something that fulfills a need and, in a deeper sense, refers to a crucial person or thing to which an individual’s emotions and motivations are directed (St Clair, 1996). An object can be used both for a real person in the external world and for a mental and internal image. It can reflect an individual’s current relationship as well as a reflection of their past relationship experiences (Van et al., 2008). Based on the object relations theory, primary communication conflicts with the object, and the predominant emotion and affect in that relationship are repeated after internalization in new relationships (Stadter, 2009).

A broad spectrum of object relations theory exists, and one of these theories is Kernberg’s theory of personality organization. Personality organization is a relatively stable structure of internalized object relations (Irani, 2018). Based on the core assumptions of object relations theories, an individual’s personality organization is formed through early interactions with significant others (Arbab et al., 2021). According to Kernberg, object relations theory studies interpersonal relationships and examines how internal structures develop based on previous internal relationships with others from a psychoanalytic perspective (St Clair, 1996).

Based on St Clair in Object Relations and Self Psychology: An Introduction, Krenberg presented the personality organization (PO) model in 1976, which divides levels of personality organization into three levels, psychotic, borderline, and neurotic. These three levels are different in terms of three dimensions of reality testing (i.e. the person’s ability to distinguish self from non-self, internal stimuli from external stimuli, and to maintain coherence between social reality standards), identity diffusion (i.e. stable sense of self and others that serves as a template for regulating interpersonal relationships), and primitive defenses (i.e. automatic psychological responses to internal and external pressures and emotional conflicts) (St Clair, 1996).

The neurotic level, or the healthiest level of personality, is characterized by cohesive identity, high-level defense mechanisms, and flawless reality testing (Caligor et al., 2007). The borderline level, between neurotic and psychotic levels, is primarily marked by extraordinary emotional instability, mood swings, and impulsive behavior (Ahmadi Marvili et al., 2019). The psychotic level of personality organization, the most pathological level, is characterized by symptoms, such as confusion between self and others and self and the environment, as well as aggressive behavior, and the individual experiences a disintegrated identity (Lenzenweger et al., 2001).

Another variable considered a suitable criterion for assessing an individual’s mental health is the meaning of life. In the face of inevitable suffering, humans seek to discover a purpose for living and why life is worth living (Rostami, 2018). Frankl, an Austrian psychoanalyst and the founder of logotherapy, considered the lack of meaning and purpose in life as the core and cause of all psychological disorders and individual neuroses (Frankl, 1985).

The meaning of life can be defined as “the amount of value that individuals feel in their lives” (Yu & Chang, 2021a). Yalom defines the meaning of life as a belief in a purposeful world with a pattern (Yalom, 1980). The meaning of life refers to a sense of existential unity that follows the pursuit of answers to questions about what life is and its purpose (Das, 1998). The meaning of life is rooted in our most fundamental beliefs about the world, ourselves, and our relationship with the world; it differs from one individual to another and from one situation to another; the term “unique meaning” is suggested to describe this diversity of meanings (Das, 1998).

Sipowicz et al., who studied logotherapy, mentioned that Frankl believed that the lack of meaning in life is the primary cause of psychological disorders, and he viewed the discovery of meaning as a fundamental human need and proposed three methods to discover or create meaning, performing a valuable and creative task, intimate relationships with others, and responsibly accepting unavoidable suffering (Sipowicz et al., 2021). One of the ways to discover or create meaning is through relationships with others. Relational meaning in life can be defined as “the scope in which an individual defines the meaning of their life based on their relationship with others” (Yu & Chang, 2021a).

The present study was conducted to compare the variables of object relations, personality organization, meaning in life, and relational meaning in life among psychology students at the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch, Lahijan City with other students of this university, considering the importance of personal characteristics and mental health of therapists in psychotherapy and their direct impact on treatment outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

The population of this study included students from the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch. The research sample included 200 students, 100 students from the psychology group, 40 students from the engineering group, 30 students from the art group, and 30 students from the nursing and laboratory sciences group. These individuals were selected using the convenience sampling method. All participants responded to four questionnaires, the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI), Kernberg’s inventory of personality organization (IPO), Steger’s meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ), and relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ).

Measures

The BORRTI, Kernberg’s IPO, Steger’s MLQ, and RMLQ were used in this study.

Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI)

This scale consists of 45 true/false items, formed from the subscales of insecure attachment, alienation, social incompetence, and egocentricity. The reliability coefficients of its subscales for a four-week re-test were reported to be between 0.58-0.90, and their internal consistency was 0.78-0.90 (Bell, 2007).

In Iran, Mesgarian et al investigated the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI) in 2017. The reliability of its factors was obtained using Cronbach’s α coefficient (0.66-0.77), split-half reliability (0.60-0.77), and the total ordinal correlation of the scale was 0.86. Significant correlations between the dimensions of the BORRTI and levels of defense mechanisms also confirmed the convergent and discriminant validity of the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (Mesgarian et al., 2017).

Inventory of personality organization (IPO)

Inventory of personality organization (IPO) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 155 items, which were answered on a 5-point Likert scale; of these, 75 items measured the three dimensions primitive defense mechanisms, identity diffusion, and reality testing, while the remaining questions pertained to interpersonal functioning (Lenzenweger et al., 2001); a study conducted by Lenzenweger et al. in 2001 reported internal consistencies of 0.88, 0.88, and 0.81 for the factors of identity confusion, reality testing, and primary defense mechanisms, respectively, using a 57-item version of the instrument, and test re-test reliabilities of 0.83, 0.80, and 0.81, respectively (Lenzenweger et al., 2001).

In Iran, Allebehbahani & Mohammadi in 2007 examined the factorial structure, validity, and reliability of a 57-item questionnaire. Based on the results, the Persian version of the instrument was reduced to 37 items. The 37-item version of the Kernberg personality organization inventory (KPOI-37) was utilized in this study and demonstrated a three-factor structure consisting of reality testing, primary defense mechanisms, and identity confusion. The reliability coefficients for the overall scale and the factors of primary defense mechanisms, identity confusion, and reality testing were 0.90, 0.82, 0.68, and 0.91, respectively (Allebehbahani & Mohammadi, 2007).

Meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

The meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ) (Steger, 2010) measures meaning in life in two dimensions, the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. Research has shown that the questionnaire has good reliability and stability of scores, as well as convergent and divergent validity. For example, good internal consistency (alpha coefficient between 0.82 and 0.87) has been reported for both dimensions, and adequate test re-test reliability (0.70 for the presence subscale and 0.73 for the search subscale) has been obtained over one month. This scale consists of 10 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (7) (Majdabadi, 2017).

In 2013, Mesrabadi et al. examined the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in 250 Iranian students. They found a significant correlation of 0.62 between the two main factors of the questionnaire. The fit indices of the model-data fit, goodness of fit index (GFA), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI), were obtained as 0.92, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively. The values of specific indices, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike information criterion (AIC), were also obtained as 0.09 and 27.178, respectively, indicating an acceptable fit of the model and demonstrating this questionnaire’s construct and diagnostic validity (Mesrabadi et al., 2013).

Relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ)

In 2021, Yu and Chang examined the factorial structure and reliability of the relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ) using a test re-test design. A factor analysis among 278 undergraduate students supported a 2-factor model, and the results were replicated in a second study with 260 undergraduate students. A future study with 103 adults over 5-6 weeks demonstrated that the RMLQ subscales were reliable. This study confirmed the reliability and validity of the RMLQ. The scale consisted of 10 items based on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (7) (Yu & Chang, 2021b).

In the present research, the validity of this questionnaire was confirmed, and its internal consistency was assessed via the Cronbach α method at 0.80.

Procedure

The present research method was based on a comparative descriptive design. The sample groups included psychology students and students from other fields, such as nursing and laboratory sciences, engineering, and art, who were selected through convenience sampling. The procedure involved brief interviews with the students of each group after selecting the target population and obtaining their consent to participate in the research by explaining the research objectives and the confidentiality of the information. After collecting the data, chi-square, t-test, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were used to analyze data by applying SPSS software, version 24.

3. Results

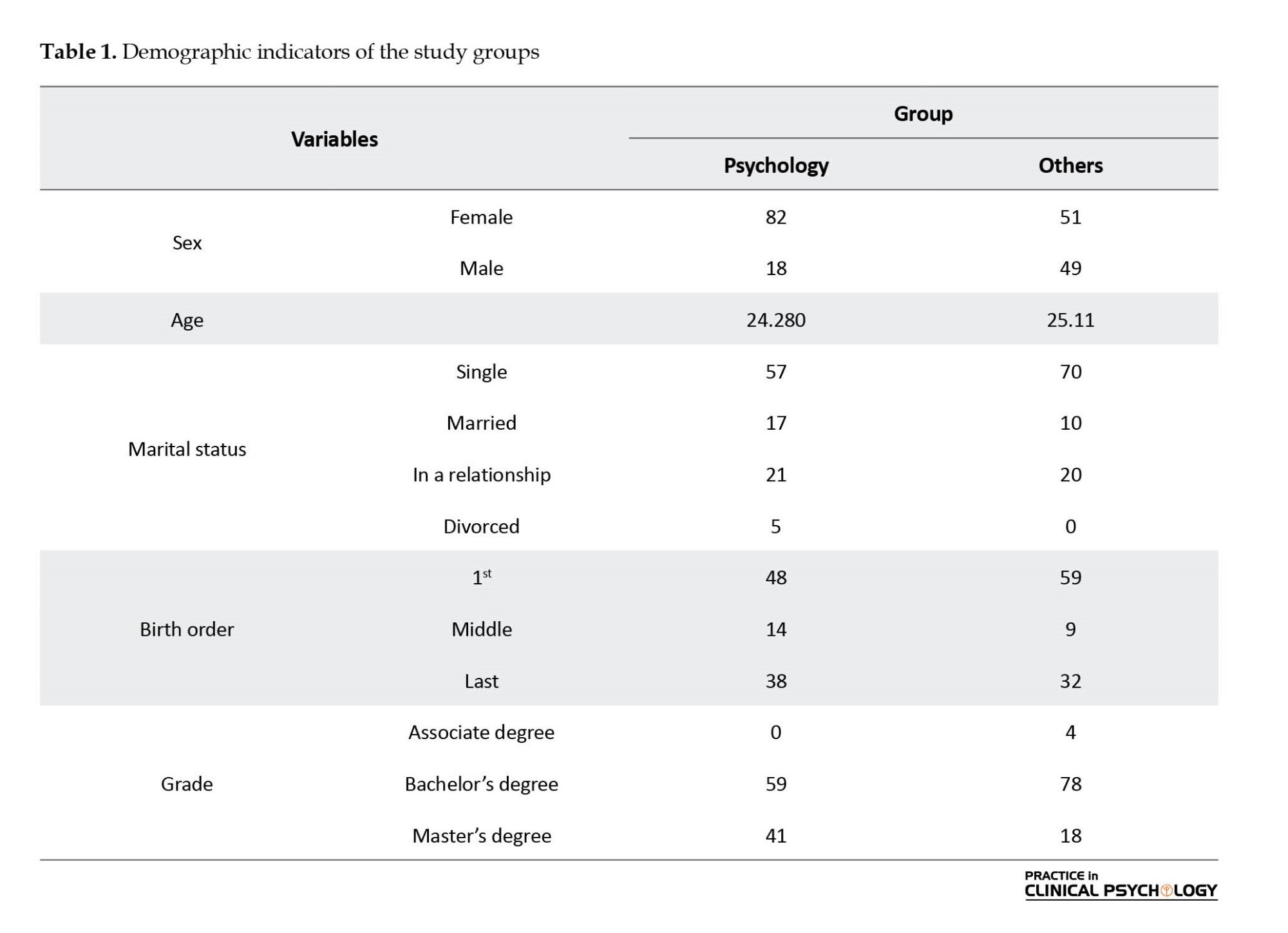

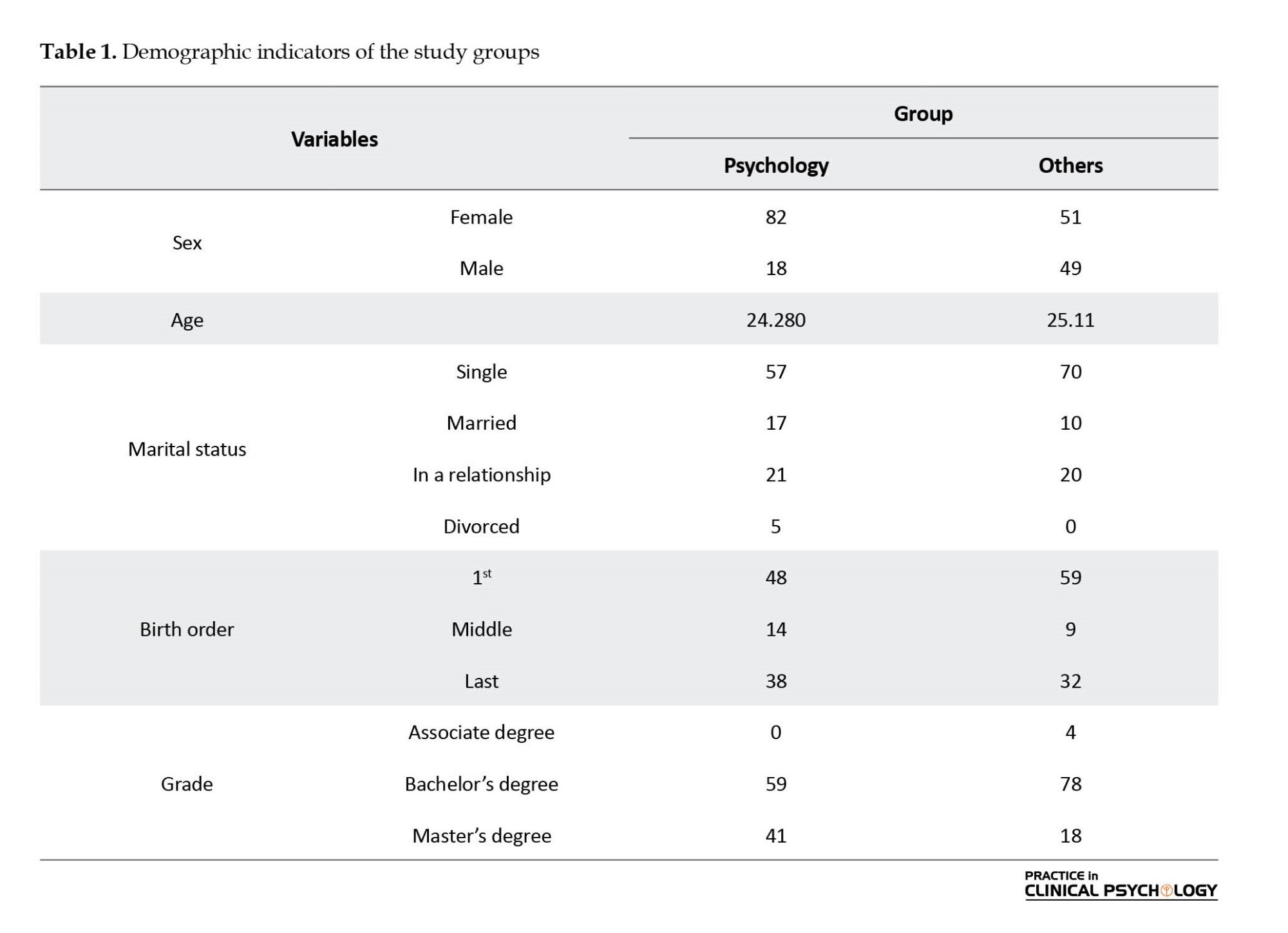

Table 1 presents that the two study groups each consist of 100 individuals. The psychological group includes 82 girls and 18 boys, while the other group includes 51 girls and 49 boys. The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant difference between the two groups regarding gender frequency (P=0.775). The two groups were also compared regarding the demographic variable of age. The mean age of the psychological group was 24.280, while the mean age of the other group was 25.11. The results of the independent samples t-test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant difference between the different groups regarding age (P=0.421, F=125.0).

In the psychology group, 57 people were single, 21 people were in a relationship, 17 people were married, and five were divorced or widowed individuals. In addition, in the other group, 70 people were single, 20 were in a relationship, 10 were married, and no divorced individuals. The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant difference between the two groups in terms of marital status (P=0.51).

The psychology group had 48 first-born children, 14 middle-born children, and 38 last-born children. In the other groups, 59 were first-born, 9 were middle-born, and 32 were last-born. Regarding educational level, 59 individuals in the psychology group were studying for a bachelor’s degree in psychology, and 41 individuals were studying for a master’s degree in psychology. In the other groups, four individuals were studying for an associate’s degree in another field, 78 were studying for a bachelor’s degree in another field, and 18 were studying for a master’s degree in another field.

Before using the parametric MANOVA, Box’s test and Levene’s test were used to meet its assumptions. Box’s test was insignificant for any of the variables; therefore the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices was met (F=0.011, P=2.297). Additionally, the results of Levene’s test showed that the error variances of the variables were equal. Levene’s test was insignificant for any variables, indicating that the assumption of equal variances across groups was met. Also, considering the non-significance of the Shapiro-Wilk test, the distribution of research variable scores was normal. These results indicated a significant difference in at least one of the dependent variables among the study groups (P=0.01 F=1.902). Therefore, a MANOVA was performed based on meeting the assumptions.

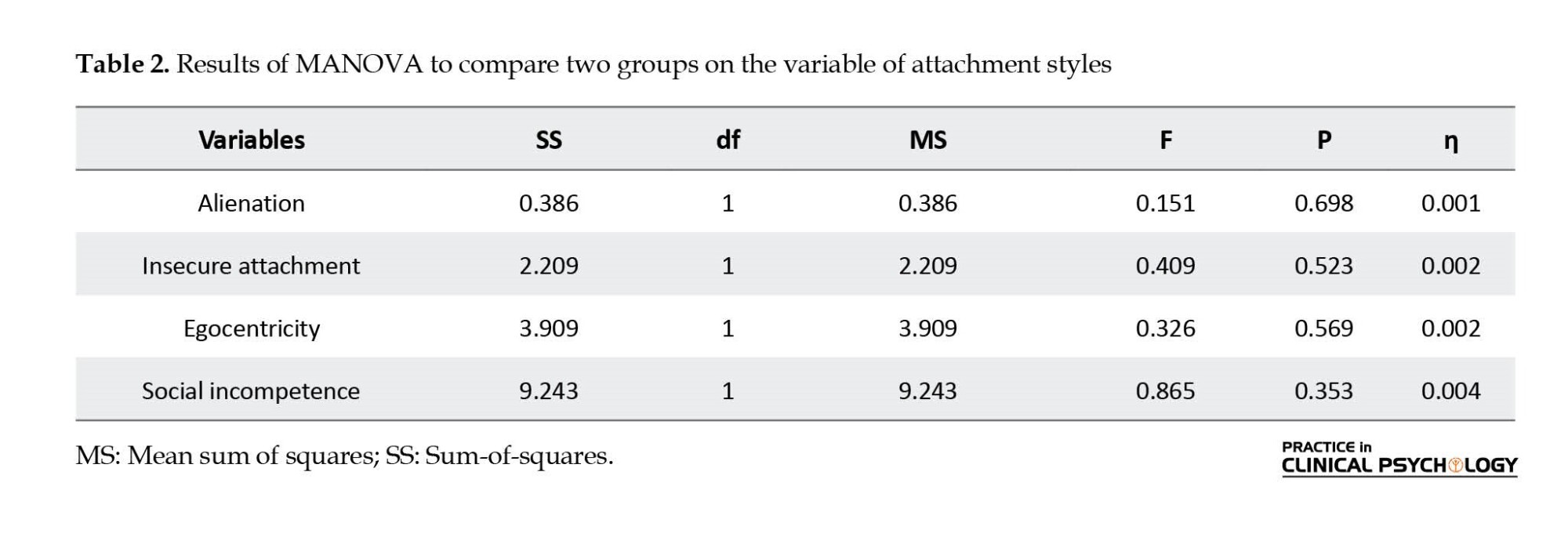

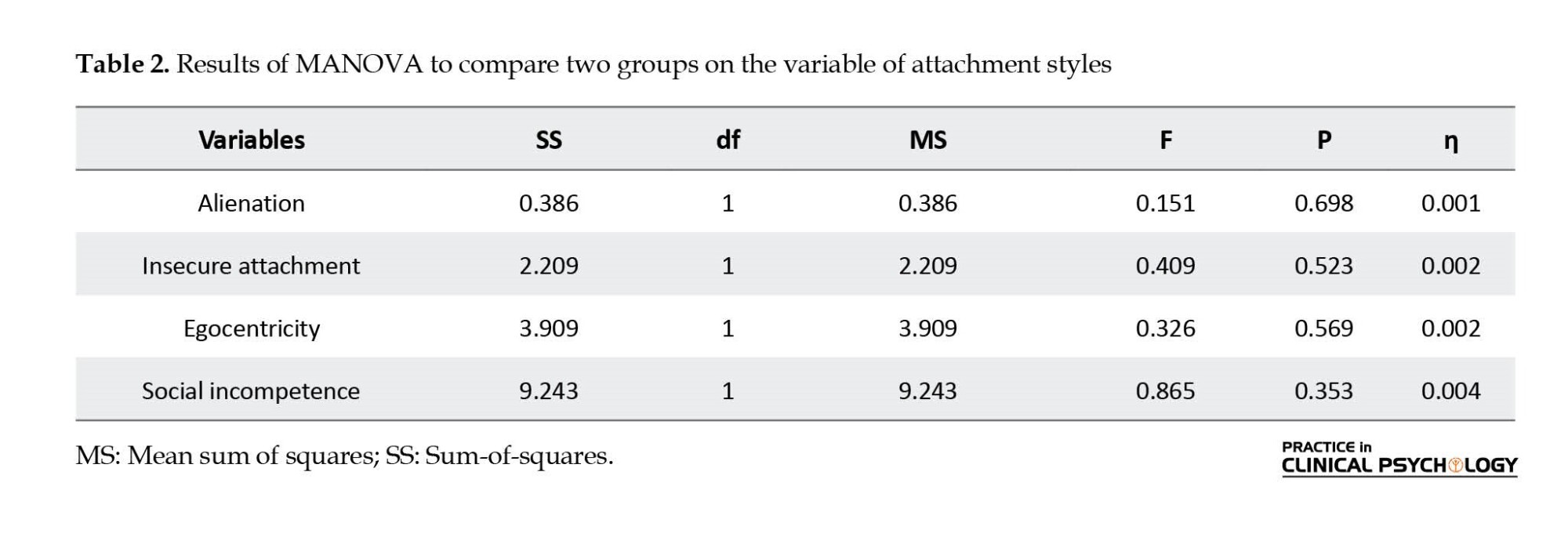

Table 2 presents no significant difference between students of different psychology and non-psychology groups in the variables and components of object relations. This means that students in both groups do not differ significantly in terms of variables, such as alienation (P=0.698), insecure attachment (P=0.523), egocentricity (P=0.326), and social incompetence (P=0.865). Furthermore, their scores on the BORRTI and its subgroups are almost similar.

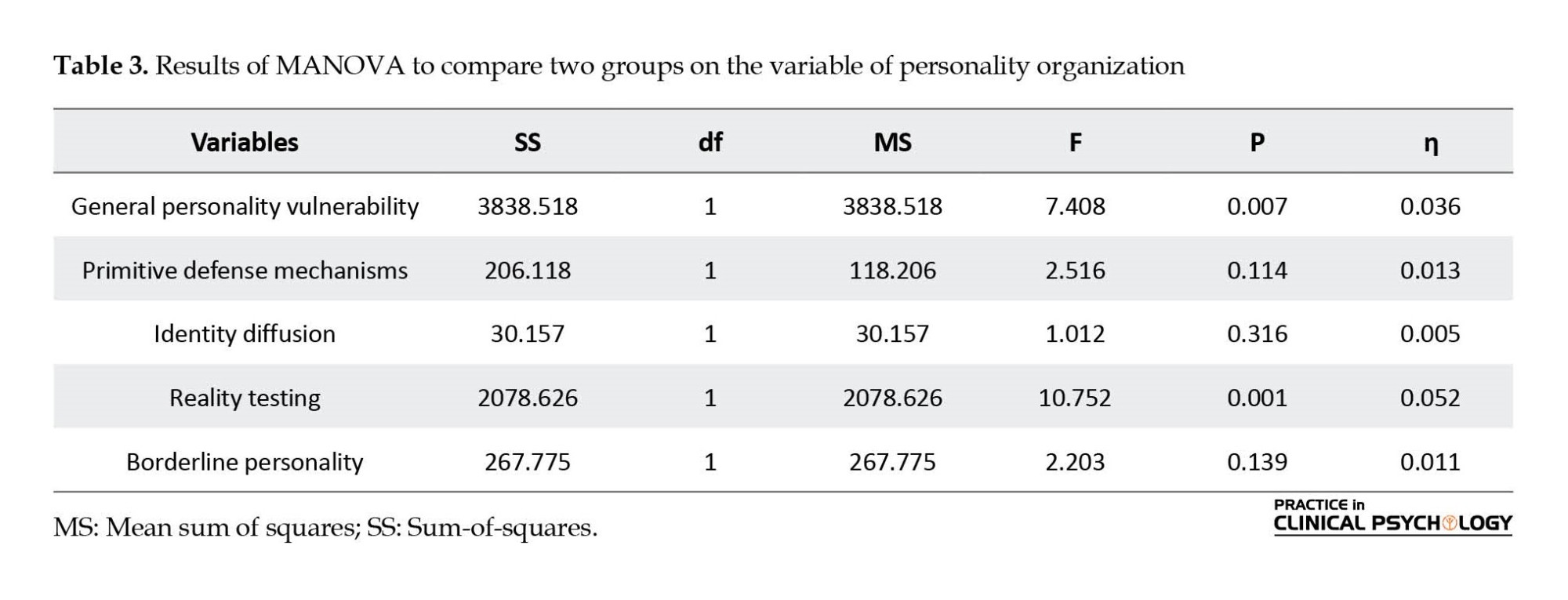

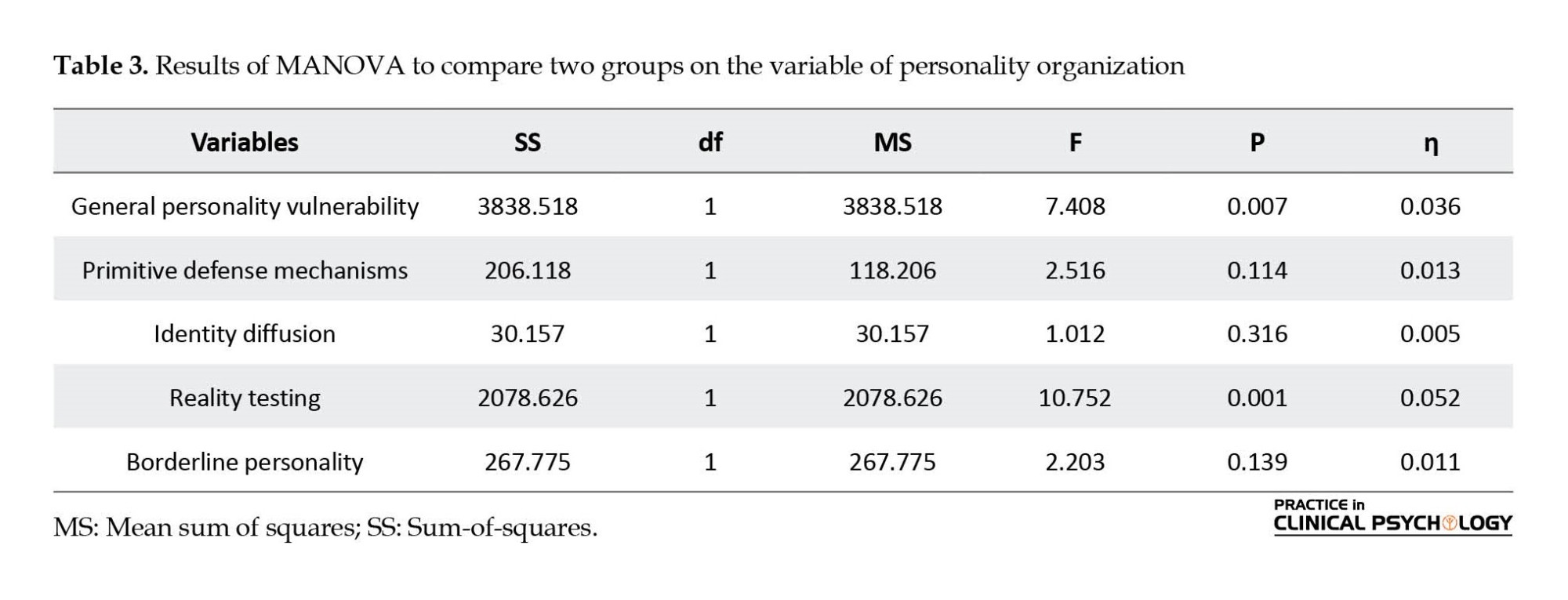

Table 3 presents significant differences between students in different groups (psychology and other majors) in the personality organization variable and its components. The results indicated that the two groups differ significantly regarding general personality vulnerability (P=0.007). Based on the analysis, general personality vulnerability is lower in psychology students, and students in other majors are more vulnerable. Additionally, no significant differences were observed in the primitive defense mechanisms scale (P=0.114) and identity diffusion (P=0.316). The two groups showed significant differences in the reality testing variable (P=0.001). Based on the analysis, reality testing is higher in psychology students, and they perform better. Also, no significant difference was observed in the borderline personality variable (P=0.139).

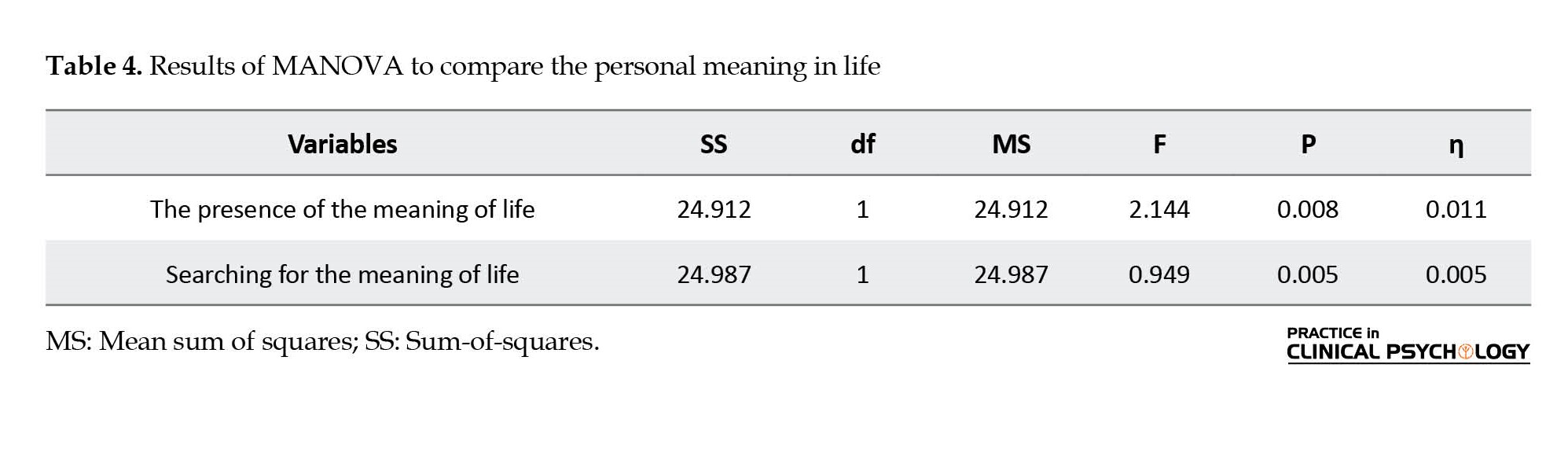

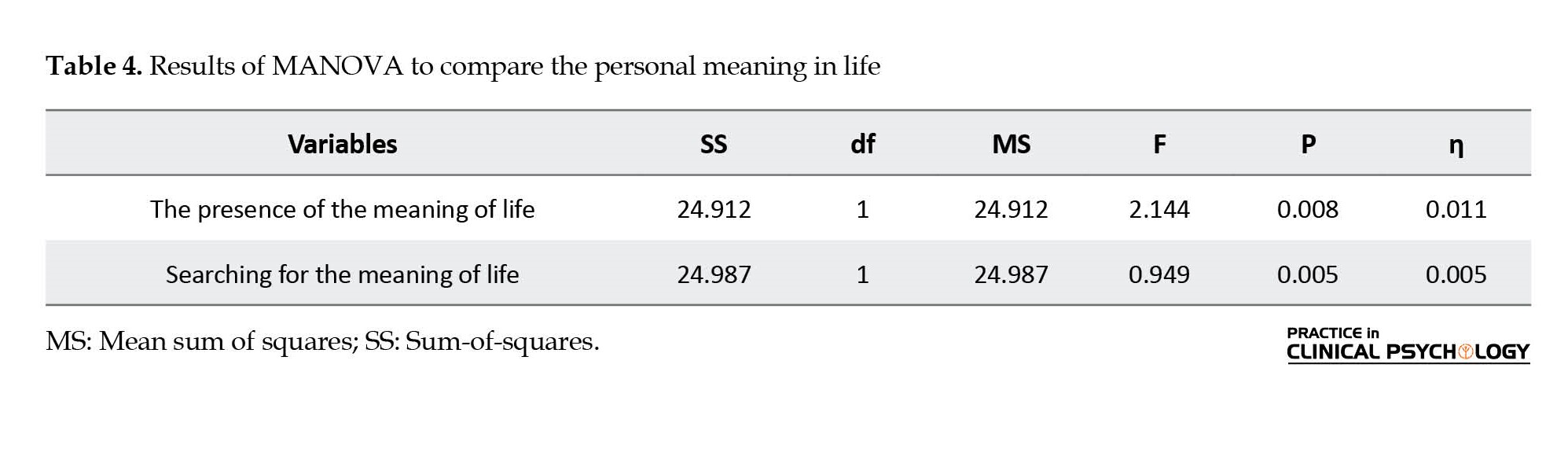

Table 4 presents the results of the MANOVA to compare the personal meaning of life variable among different groups of psychology students and other groups. As the table shows, a significant difference is observed in the personal meaning of life variable and its components among the different groups. Psychology students experience a significant difference in the presence of meaning in life (P=0.008) and the search for meaning in life (P=0.005) variables. The results indicated that psychology students perform better in this area.

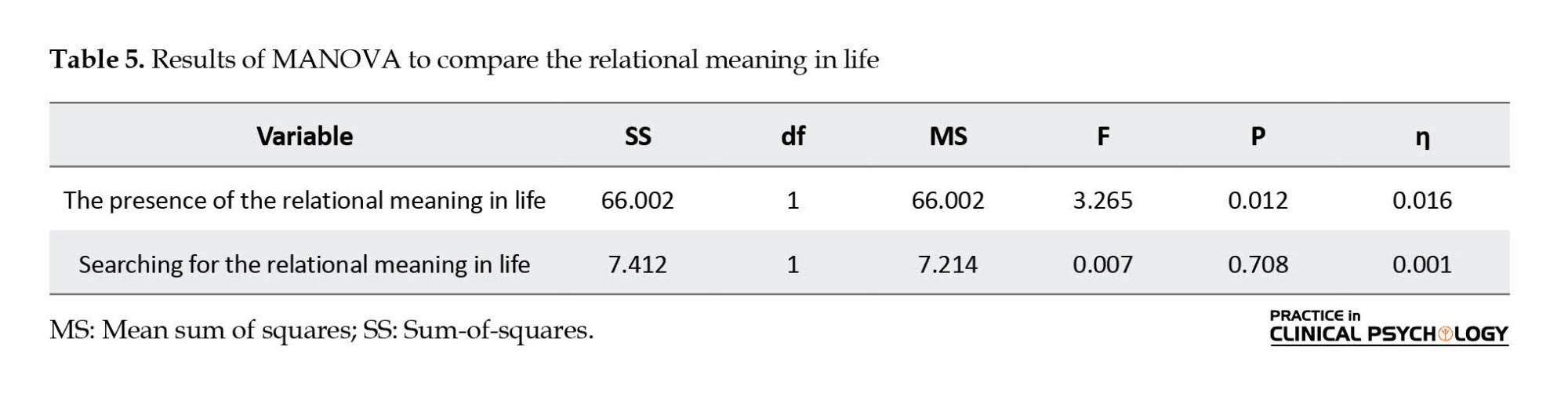

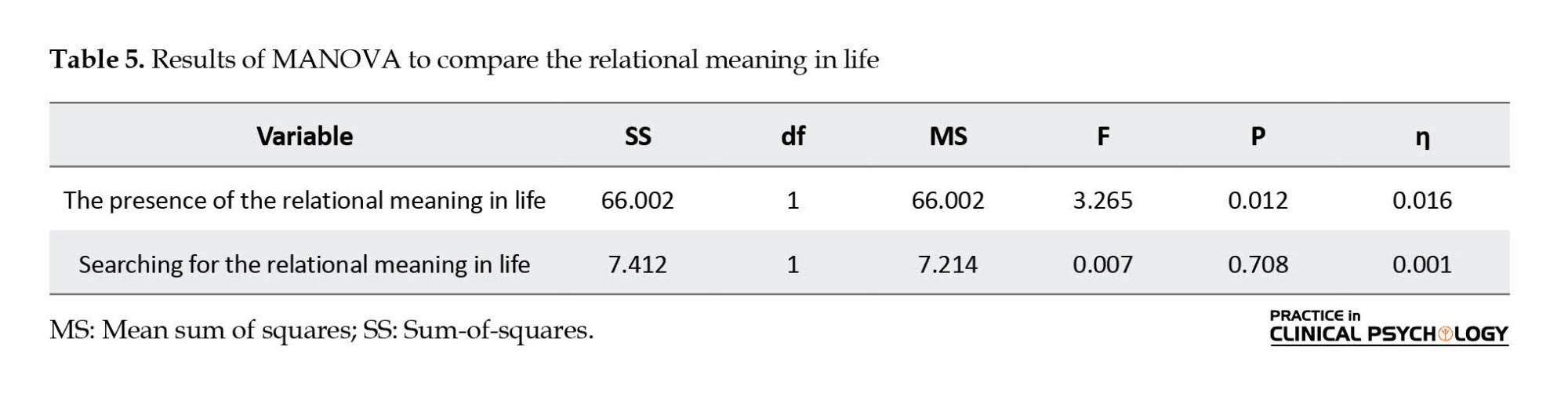

Table 5 presents a significant difference between different groups of students in the variables of relational meaning in life and its components. Based on the analysis results, psychology students experience a significant difference in the presence of Relational meaning in life (P=0.012) and the variable of the search for relational meaning in life (P=0.007). The results indicated that psychology students perform better in this area.

4. Discussion

The therapist’s personality traits are among the most critical factors in determining treatment outcomes (Delgadillo et al., 2020).

These characteristics influence treatment outcomes by affecting the therapeutic approach and creating the therapeutic alliance (Anderson et al., 2009). Research has shown that the ability to establish a therapeutic alliance is one of the most significant predictors of treatment outcomes (Delgadillo et al., 2020). In this study, the quality of object relations, personality organization, personal meaning of life, and relational meaning in life were considered as examples of personality traits and standards for mental health.

Object relations, reflecting an individual’s capacity for interpersonal communication and the quality of these relationships, are defined as representations of the self and others accompanied by emotions associated with these representations (Stadter, 2009). Based on these theories, it is possible to observe the repetition of conflicts in primary interpersonal relationships with attachment and dominant emotions in new relationships, which are rooted in the internalization of these conflicts (Diguer et al., 2004). The therapeutic relationship is also one of the types of relationships that individual experiences throughout their life, and the quality of the therapist-patient interpersonal relationships impact the events that occur in the therapy room (Jamil et al., 2015).

One of these theories of object relations is Kernberg’s personality organization theory (Mesgarian et al., 2017). From the perspective of this theory, personality organization is a relatively stable structure of internalized interpersonal relationships (Fonagy et al., 2006), which takes shape through early interactions with crucial individuals in life (Kelly, 2014).

Kernberg’s model of personality organization (OP) was introduced in 1976, which divided the levels of personality organization into three levels, psychotic, borderline, and neurotic (St Clair, 1996).

The neurotic level represents the healthiest level of personality (Van et al., 2008); the borderline level, with the main characteristic of emotional and behavioral instability, is placed between the healthy and psychotic levels (St Clair, 1996). Finally, the psychotic level indicates the sickest level of personality, with symptoms, such as confusion about oneself and others and the environment, aggressive behavior, and lack of identity coherence (Irani, 2018).

The meaning in life is another variable that can be a measure of an individual’s psychological health. The meaning in life is defined as “the amount of value that individuals feel in their lives” (Arbab et al., 2021). Discovering or creating meaning, engaging in a useful and creative task, having an intimate relationship with others, and accepting unavoidable suffering responsibly (Caligor et al., 2007). One of the ways to discover or create meaning is to find the meaning of life through relationships with others, which is also called the relational meaning in life. Relational meaning in life is introduced as “the extent to which individuals define the meaning of their lives based on their relationship with others” (Arbab et al., 2021).

In this study, the quality of object relations, personality organization, personal meaning of life, and relational meaning in life were compared between psychology students of Lahijan Azad University and other groups of this university. Initially, to collect samples, the students completed the BORRTI, Kernberg’s IPO, Steger’s MLQ, and RMLQ. Then, the data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods, and the main hypotheses were tested through hypothesis testing.

This study hypothesized that psychology students would have higher quality object relations, higher levels of personality organization, and experience more meaningful lives compared to other university students. However, the results showed that the status of psychology students at the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch, in terms of the quality of object relations is not significantly different from students of other groups of the university, and both groups obtained similar scores, rejecting the research hypothesis.

However, in the personality organization variable, psychology students obtained better grades than other students, although this difference was mainly related to the reality testing subscale. Little difference was observed between psychology students and other students in the two other subscales of kernberg’s personality inventory. One possible reason for this improvement in grades can be found in the knowledge of psychology students who did not honestly answer the questions related to the reality testing subscale and presented a better self-image. On the other hand, given that a large part of the psychological sample consisted of master’s students, the likelihood of obtaining lower scores in the reality testing subscale decreases.

In the end, in the two variables of meaning in life and relational meaning in life, the performance of psychology students was better than other students. According to the results of this study, psychology students experience more meaningful lives than other students at the Islamic Azad University of Lahijan City. The root of this grade improvement can be found in the psychology profession. A field whose primary goal is to help other humans and whose borders are vast can provide a wealthy source of meaning in life. On the other hand, the relationship-centered nature of this field, which inevitably expands the communication skills of its graduates, can be a great source of relational meaning in life (Ahmadi Marvili et al., 2019).

Conclusion

The present study compares the relationship between object relations, personality organization, personal meaning in life, and relational meaning in the life of psychology students with other students of the Islamic Azad University Lahijan campus. No significant difference is observed between the quality of object relations of psychology students and students of other fields; a significant difference is observed in the level of personality organization between psychology students and students of other fields; a significant difference is observed in the personal meaning of life between psychology students and students of other fields; and also a significant difference is observed in the relational meaning in life between psychology students and students of other fields.

Limitations and suggestions

Considering the difficulty of controlling extraneous variables in behavioral studies, controlling such variables, including parenting style, sources of support, academic level of psychology students, history of receiving psychotherapy, etc. was also challenging in this study, and it is recommended to control for these variables in future studies.

In addition, one of the main limitations of using questionnaires is the honesty of participants and the ability of the questionnaire to measure a psychological variable; therefore, it is recommended that future research use clinical interviews to determine the personality organization, meaning of life, and object relations of individuals in the study.

Future researchers should use self-reported questionnaires and clinical interviews to collect more accurate information. It is also suggested that research be repeated in larger samples and universities with stricter academic standards and entry criteria so that the samples of each group are more representative of their respective groups.

On the other hand, to ensure that the sample of psychology students is more representative of the psychology community than ever before, it is recommended to limit the study to master’s and PhD students so that the impact of studying psychology on research variables is more pronounced. It is also recommended that some intervention variables, such as parenting style, having or not having children, history of receiving psychotherapy, and the approach that an individual learns in psychology students be examined and controlled in future research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current research was confirmed in the Research Ethics Committees of the Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch (Code: IR.IAU.TON.REC.1401.068). Participants were asked to read the participant information and to consent before entering the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master's thesis of Mahyar Arzpeyma, approved by Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their deep appreciation for the invaluable assistance provided by Amirsam Kianimoghadam, and Sirvan Asmaeemajd.

References

Ahmadi Marvili, N., Mirzahoseini, H., & Monirpoor, N. (2019). [The prediction model of self- harm behaviors and tendency to suicide in adolescence based on attachment styles and personality organization: Mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychological Research, 10(3), 101-117. [DOI:10.22059/JAPR.2019.274866.643162]

Allebehbahani, M., & Mohammadi, N. (2007). [Examination of psychometric properties of Kernberg’s personality organization inventory ( Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 185-197. [Link]

Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: Facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 755-768. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20583] [PMID]

Arbab, H., Mirzahoseini, H., & Monirpour, N. (2021). [Predicting pathological substance use relapse based on object-relations and personality organization in male addicts treated with methadone (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal(RRJ), 10(5), 173-184. [Link]

Bell, M. D. (2007). Bell object relations and reality testing inventory: BORRTI. Western Psychological Services. [Link]

Caligor, E., Kernberg, O. F., & Clarkin, J. F. (2007). Handbook of dynamic psychotherapy for higher level personality pathology. Washington: American Psychiatric Pub. [Link]

Das, A. K. (1998). Frankl and the realm of meaning. The Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 36(4), 199-211. [DOI:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1998.tb00392.x]

Delgadillo, J., Branson, A., Kellett, S., Myles-Hooton, P., Hardy, G. E., & Shafran, R. (2020). Therapist personality traits as predictors of psychological treatment outcomes. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 857-870. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2020.1731927] [PMID]

Diguer, L., Pelletier, S., Hébert, É., Descôteaux, J., Rousseau, J. P., & Daoust, J. P. (2004). Personality organizations, psychiatric severity, and self and object representations. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21(2), 259-275. [DOI:10.1037/0736-9735.21.2.259]

Fonagy, P., Target, M., & Gergely, G. (2006). Psychoanalytic perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (pp. 701–749). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Link]

Frankl, N. (1985) Man's search for meaning [A. Kheirabadi, Persian. Tehran: Tehran University Publications. [Link]

Irani, Z., & Bakhtiari, S. (2018). [The role of personality organization and psychological basic psychological needs in predicting malformed body-seem attempters admitted to cosmetic surgery (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Surgery, 25(4), 66-74. [Link]

Jamil, L., Atef Vahid, M., Dehghani, M., & Habibi, M. (2015). [The mental health through psychodynamic perspective: The relationship between the ego strength, the defense styles, and the object relations to mental health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 21(2), 144-154. [Link]

Kelly, F. D. (2014).The assessment of object relations phenomena in adolescents: Tat and rorschach measu. New York: Routledge.[DOI:10.4324/9781315805931]

Lenzenweger, M. F., Clarkin, J. F., Kernberg, O. F., & Foelsch, P. A. (2001). The inventory of personality organization: psychometric properties, factorial composition, and criterion relations with affect, aggressive dyscontrol, psychosis proneness, and self-domains in a nonclinical sample. Psychological Assessment, 13(4), 577-591. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.13.4.577] [PMID]

Majdabadi, Z. (2017). Meaning in life questionnaire (Persian)]. Developmental Psychology (Journal of Iranian Psychologists) 13(51), 331-333. [Link]

Mesgarian, F., Azad Fallah, P., Farahani, H., & Ghorbani, N. (2017). [Object relations and defense mechanisms in social anxiety (Persian)]. Journal of Developmnetal Psychology, 14(53), 3-14. [Link]

Mesrabadi, J., Jafariyan, S., & Ostovar, N. (2013). Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 83-90. [Link]

Mohammad Nia, S., & Mashhadi, A. (2018). [The effect of meaning of life on the relationship between attitude toward substance abuse and depression (Persian)]. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam, 6(3), 43-51. [DOI:10.29252/shefa.6.3.43]

Rostami Y. (2018). [Schopenhauer on the meaning of life: An evaluation (Persian)]. Philosophy of Religion Research (Namah-I Hikmat). 16(1), 109-126. [DOI: 10.30497/PRR.2018.2351]

Sipowicz, K., Podlecka, M., & Pietras, T. (2021). Logotherapy-an attempt to establish a new dialogue with one’s own life. Kwartalnik Naukowy Fides et Ratio, 46(2), 261-269.[DOI:10.34766/fetr.v46i2.811]

St Clair M. (2007). Object relations and self psychology: An introduction [A.Tahmasb, & H. Aliaghaei, Persian trans.). Tehran: Ney. [Link]

Stadter M. (2009). Object relations brief therapy: The therapeutic relationship in short-term work: Jason Aronson; 2009. [Link]

Steger, M. F. (2010). MLQ description scoring and feedback packet [Internet]. Retrieved from [Link]

Topolinski, S., & Hertel, G. (2007). The role of personality in psychotherapists’ careers: Relationships between personality traits, therapeutic schools, and job satisfaction. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 365-375. [DOI:10.1080/10503300600830736]

Tremblay, J. M., Herron, W. G., & Schultz, C. L. (1986). Relation between therapeutic orientation and personality in psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 17(2), 106–110. [DOI:10.1037/0735-7028.17.2.106]

Van, H. L., Hendriksen, M., Schoevers, R. A., Peen, J., Abraham, R. A., & Dekker, J. (2008). Predictive value of object relations for therapeutic alliance and outcome in psychotherapy for depression: An exploratory study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(9), 655-662. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318183f8c2] [PMID]

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books. [Link]

Yu, E. A., & Chang, E. C. (2021). Relational meaning in life as a predictor of interpersonal well-being: A prospective analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110377. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110377]

Yu, E. A., & Chang, E. C. (2021). Construction of the relational meaning in life questionnaire: An exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic study of relational meaning. Current Psychology, 40, 1746-1751. [Link]

Numerous studies have shown that personal and psychological characteristics of therapists, such as gender, type of education, and selected approach, directly impact psychotherapy outcomes (Stadter, 2009). One of the vital characteristics is the therapist’s personality traits (Delgadillo et al., 2020). The therapist’s approach, the quality of the therapeutic alliance established during treatment, and the therapeutic outcomes are all directly influenced by the therapist’s personality traits (Topolinski & Hertel, 2007). Research has shown that three main personal characteristics determine the effectiveness of a psychotherapist’s work, the ability to create positive therapeutic alliances with a wide range of clients, which is a significant predictor of treatment outcomes, the development of extensive facilitative interpersonal skills that enable therapists to work with challenging and complex patients, and finally, the improvement of psychotherapeutic skills through extensive practice that addresses therapeutic shortcomings (Delgadillo et al., 2020). The personality characteristics of a psychotherapist is one of the most critical factors determining the psychotherapist’s selected approach (Tremblay et al., 1986) and according to Topolinski and Hertel’s research, play a crucial role in the therapeutic orientations and job satisfaction of psychologists (Topolinski & Hertel, 2007). One of the crucial personal characteristics of any human being is the level of object relations.

As all humans are born in an underdeveloped and dependent state, relying on others for their physiological and psychological survival, the need for relationships with others is considered one of the most fundamental human needs from infancy, and this forms the cornerstone of attachment theories or object relations (Stadter, 2009). Object relations have become one of the fundamental topics in psychology in recent decades (Diguer et al., 2004). From around 1950, profound changes in psychotherapeutic theories began, and the influence of interpersonal relationships and the underlying patterns of thinking and emotions on mental disorders were taken more seriously (Jamil et al., 2015). From the perspective of psychoanalytic theories, object relations are one of the factors that guarantee mental health and play a significant role in the occurrence of diseases and the formation of individuals’ personalities (Mesgarian et al., 2017). Despite the acceptance of many classic psychoanalytic concepts, object relations theorists consider the creation of ineffective intra-psychic structures of self and others and difficult relationships with parents in early childhood as the main factor in the occurrence of a wide range of mental disorders in adulthood (Fonagy et al., 2006).

Object relations are representations of self and others, accompanied by emotions, which indicate an individual’s capacity for interpersonal communication and the quality of these relationships (Kelly, 2014). The term object or object relation, first introduced by Freud in psychology, refers to something that fulfills a need and, in a deeper sense, refers to a crucial person or thing to which an individual’s emotions and motivations are directed (St Clair, 1996). An object can be used both for a real person in the external world and for a mental and internal image. It can reflect an individual’s current relationship as well as a reflection of their past relationship experiences (Van et al., 2008). Based on the object relations theory, primary communication conflicts with the object, and the predominant emotion and affect in that relationship are repeated after internalization in new relationships (Stadter, 2009).

A broad spectrum of object relations theory exists, and one of these theories is Kernberg’s theory of personality organization. Personality organization is a relatively stable structure of internalized object relations (Irani, 2018). Based on the core assumptions of object relations theories, an individual’s personality organization is formed through early interactions with significant others (Arbab et al., 2021). According to Kernberg, object relations theory studies interpersonal relationships and examines how internal structures develop based on previous internal relationships with others from a psychoanalytic perspective (St Clair, 1996).

Based on St Clair in Object Relations and Self Psychology: An Introduction, Krenberg presented the personality organization (PO) model in 1976, which divides levels of personality organization into three levels, psychotic, borderline, and neurotic. These three levels are different in terms of three dimensions of reality testing (i.e. the person’s ability to distinguish self from non-self, internal stimuli from external stimuli, and to maintain coherence between social reality standards), identity diffusion (i.e. stable sense of self and others that serves as a template for regulating interpersonal relationships), and primitive defenses (i.e. automatic psychological responses to internal and external pressures and emotional conflicts) (St Clair, 1996).

The neurotic level, or the healthiest level of personality, is characterized by cohesive identity, high-level defense mechanisms, and flawless reality testing (Caligor et al., 2007). The borderline level, between neurotic and psychotic levels, is primarily marked by extraordinary emotional instability, mood swings, and impulsive behavior (Ahmadi Marvili et al., 2019). The psychotic level of personality organization, the most pathological level, is characterized by symptoms, such as confusion between self and others and self and the environment, as well as aggressive behavior, and the individual experiences a disintegrated identity (Lenzenweger et al., 2001).

Another variable considered a suitable criterion for assessing an individual’s mental health is the meaning of life. In the face of inevitable suffering, humans seek to discover a purpose for living and why life is worth living (Rostami, 2018). Frankl, an Austrian psychoanalyst and the founder of logotherapy, considered the lack of meaning and purpose in life as the core and cause of all psychological disorders and individual neuroses (Frankl, 1985).

The meaning of life can be defined as “the amount of value that individuals feel in their lives” (Yu & Chang, 2021a). Yalom defines the meaning of life as a belief in a purposeful world with a pattern (Yalom, 1980). The meaning of life refers to a sense of existential unity that follows the pursuit of answers to questions about what life is and its purpose (Das, 1998). The meaning of life is rooted in our most fundamental beliefs about the world, ourselves, and our relationship with the world; it differs from one individual to another and from one situation to another; the term “unique meaning” is suggested to describe this diversity of meanings (Das, 1998).

Sipowicz et al., who studied logotherapy, mentioned that Frankl believed that the lack of meaning in life is the primary cause of psychological disorders, and he viewed the discovery of meaning as a fundamental human need and proposed three methods to discover or create meaning, performing a valuable and creative task, intimate relationships with others, and responsibly accepting unavoidable suffering (Sipowicz et al., 2021). One of the ways to discover or create meaning is through relationships with others. Relational meaning in life can be defined as “the scope in which an individual defines the meaning of their life based on their relationship with others” (Yu & Chang, 2021a).

The present study was conducted to compare the variables of object relations, personality organization, meaning in life, and relational meaning in life among psychology students at the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch, Lahijan City with other students of this university, considering the importance of personal characteristics and mental health of therapists in psychotherapy and their direct impact on treatment outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

The population of this study included students from the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch. The research sample included 200 students, 100 students from the psychology group, 40 students from the engineering group, 30 students from the art group, and 30 students from the nursing and laboratory sciences group. These individuals were selected using the convenience sampling method. All participants responded to four questionnaires, the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI), Kernberg’s inventory of personality organization (IPO), Steger’s meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ), and relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ).

Measures

The BORRTI, Kernberg’s IPO, Steger’s MLQ, and RMLQ were used in this study.

Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI)

This scale consists of 45 true/false items, formed from the subscales of insecure attachment, alienation, social incompetence, and egocentricity. The reliability coefficients of its subscales for a four-week re-test were reported to be between 0.58-0.90, and their internal consistency was 0.78-0.90 (Bell, 2007).

In Iran, Mesgarian et al investigated the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (BORRTI) in 2017. The reliability of its factors was obtained using Cronbach’s α coefficient (0.66-0.77), split-half reliability (0.60-0.77), and the total ordinal correlation of the scale was 0.86. Significant correlations between the dimensions of the BORRTI and levels of defense mechanisms also confirmed the convergent and discriminant validity of the Bell object relations and reality testing inventory (Mesgarian et al., 2017).

Inventory of personality organization (IPO)

Inventory of personality organization (IPO) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 155 items, which were answered on a 5-point Likert scale; of these, 75 items measured the three dimensions primitive defense mechanisms, identity diffusion, and reality testing, while the remaining questions pertained to interpersonal functioning (Lenzenweger et al., 2001); a study conducted by Lenzenweger et al. in 2001 reported internal consistencies of 0.88, 0.88, and 0.81 for the factors of identity confusion, reality testing, and primary defense mechanisms, respectively, using a 57-item version of the instrument, and test re-test reliabilities of 0.83, 0.80, and 0.81, respectively (Lenzenweger et al., 2001).

In Iran, Allebehbahani & Mohammadi in 2007 examined the factorial structure, validity, and reliability of a 57-item questionnaire. Based on the results, the Persian version of the instrument was reduced to 37 items. The 37-item version of the Kernberg personality organization inventory (KPOI-37) was utilized in this study and demonstrated a three-factor structure consisting of reality testing, primary defense mechanisms, and identity confusion. The reliability coefficients for the overall scale and the factors of primary defense mechanisms, identity confusion, and reality testing were 0.90, 0.82, 0.68, and 0.91, respectively (Allebehbahani & Mohammadi, 2007).

Meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

The meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ) (Steger, 2010) measures meaning in life in two dimensions, the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. Research has shown that the questionnaire has good reliability and stability of scores, as well as convergent and divergent validity. For example, good internal consistency (alpha coefficient between 0.82 and 0.87) has been reported for both dimensions, and adequate test re-test reliability (0.70 for the presence subscale and 0.73 for the search subscale) has been obtained over one month. This scale consists of 10 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (7) (Majdabadi, 2017).

In 2013, Mesrabadi et al. examined the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in 250 Iranian students. They found a significant correlation of 0.62 between the two main factors of the questionnaire. The fit indices of the model-data fit, goodness of fit index (GFA), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI), were obtained as 0.92, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively. The values of specific indices, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike information criterion (AIC), were also obtained as 0.09 and 27.178, respectively, indicating an acceptable fit of the model and demonstrating this questionnaire’s construct and diagnostic validity (Mesrabadi et al., 2013).

Relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ)

In 2021, Yu and Chang examined the factorial structure and reliability of the relational meaning in life questionnaire (RMLQ) using a test re-test design. A factor analysis among 278 undergraduate students supported a 2-factor model, and the results were replicated in a second study with 260 undergraduate students. A future study with 103 adults over 5-6 weeks demonstrated that the RMLQ subscales were reliable. This study confirmed the reliability and validity of the RMLQ. The scale consisted of 10 items based on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (7) (Yu & Chang, 2021b).

In the present research, the validity of this questionnaire was confirmed, and its internal consistency was assessed via the Cronbach α method at 0.80.

Procedure

The present research method was based on a comparative descriptive design. The sample groups included psychology students and students from other fields, such as nursing and laboratory sciences, engineering, and art, who were selected through convenience sampling. The procedure involved brief interviews with the students of each group after selecting the target population and obtaining their consent to participate in the research by explaining the research objectives and the confidentiality of the information. After collecting the data, chi-square, t-test, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were used to analyze data by applying SPSS software, version 24.

3. Results

Table 1 presents that the two study groups each consist of 100 individuals. The psychological group includes 82 girls and 18 boys, while the other group includes 51 girls and 49 boys. The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant difference between the two groups regarding gender frequency (P=0.775). The two groups were also compared regarding the demographic variable of age. The mean age of the psychological group was 24.280, while the mean age of the other group was 25.11. The results of the independent samples t-test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant difference between the different groups regarding age (P=0.421, F=125.0).

In the psychology group, 57 people were single, 21 people were in a relationship, 17 people were married, and five were divorced or widowed individuals. In addition, in the other group, 70 people were single, 20 were in a relationship, 10 were married, and no divorced individuals. The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant difference between the two groups in terms of marital status (P=0.51).

The psychology group had 48 first-born children, 14 middle-born children, and 38 last-born children. In the other groups, 59 were first-born, 9 were middle-born, and 32 were last-born. Regarding educational level, 59 individuals in the psychology group were studying for a bachelor’s degree in psychology, and 41 individuals were studying for a master’s degree in psychology. In the other groups, four individuals were studying for an associate’s degree in another field, 78 were studying for a bachelor’s degree in another field, and 18 were studying for a master’s degree in another field.

Before using the parametric MANOVA, Box’s test and Levene’s test were used to meet its assumptions. Box’s test was insignificant for any of the variables; therefore the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices was met (F=0.011, P=2.297). Additionally, the results of Levene’s test showed that the error variances of the variables were equal. Levene’s test was insignificant for any variables, indicating that the assumption of equal variances across groups was met. Also, considering the non-significance of the Shapiro-Wilk test, the distribution of research variable scores was normal. These results indicated a significant difference in at least one of the dependent variables among the study groups (P=0.01 F=1.902). Therefore, a MANOVA was performed based on meeting the assumptions.

Table 2 presents no significant difference between students of different psychology and non-psychology groups in the variables and components of object relations. This means that students in both groups do not differ significantly in terms of variables, such as alienation (P=0.698), insecure attachment (P=0.523), egocentricity (P=0.326), and social incompetence (P=0.865). Furthermore, their scores on the BORRTI and its subgroups are almost similar.

Table 3 presents significant differences between students in different groups (psychology and other majors) in the personality organization variable and its components. The results indicated that the two groups differ significantly regarding general personality vulnerability (P=0.007). Based on the analysis, general personality vulnerability is lower in psychology students, and students in other majors are more vulnerable. Additionally, no significant differences were observed in the primitive defense mechanisms scale (P=0.114) and identity diffusion (P=0.316). The two groups showed significant differences in the reality testing variable (P=0.001). Based on the analysis, reality testing is higher in psychology students, and they perform better. Also, no significant difference was observed in the borderline personality variable (P=0.139).

Table 4 presents the results of the MANOVA to compare the personal meaning of life variable among different groups of psychology students and other groups. As the table shows, a significant difference is observed in the personal meaning of life variable and its components among the different groups. Psychology students experience a significant difference in the presence of meaning in life (P=0.008) and the search for meaning in life (P=0.005) variables. The results indicated that psychology students perform better in this area.

Table 5 presents a significant difference between different groups of students in the variables of relational meaning in life and its components. Based on the analysis results, psychology students experience a significant difference in the presence of Relational meaning in life (P=0.012) and the variable of the search for relational meaning in life (P=0.007). The results indicated that psychology students perform better in this area.

4. Discussion

The therapist’s personality traits are among the most critical factors in determining treatment outcomes (Delgadillo et al., 2020).

These characteristics influence treatment outcomes by affecting the therapeutic approach and creating the therapeutic alliance (Anderson et al., 2009). Research has shown that the ability to establish a therapeutic alliance is one of the most significant predictors of treatment outcomes (Delgadillo et al., 2020). In this study, the quality of object relations, personality organization, personal meaning of life, and relational meaning in life were considered as examples of personality traits and standards for mental health.

Object relations, reflecting an individual’s capacity for interpersonal communication and the quality of these relationships, are defined as representations of the self and others accompanied by emotions associated with these representations (Stadter, 2009). Based on these theories, it is possible to observe the repetition of conflicts in primary interpersonal relationships with attachment and dominant emotions in new relationships, which are rooted in the internalization of these conflicts (Diguer et al., 2004). The therapeutic relationship is also one of the types of relationships that individual experiences throughout their life, and the quality of the therapist-patient interpersonal relationships impact the events that occur in the therapy room (Jamil et al., 2015).

One of these theories of object relations is Kernberg’s personality organization theory (Mesgarian et al., 2017). From the perspective of this theory, personality organization is a relatively stable structure of internalized interpersonal relationships (Fonagy et al., 2006), which takes shape through early interactions with crucial individuals in life (Kelly, 2014).

Kernberg’s model of personality organization (OP) was introduced in 1976, which divided the levels of personality organization into three levels, psychotic, borderline, and neurotic (St Clair, 1996).

The neurotic level represents the healthiest level of personality (Van et al., 2008); the borderline level, with the main characteristic of emotional and behavioral instability, is placed between the healthy and psychotic levels (St Clair, 1996). Finally, the psychotic level indicates the sickest level of personality, with symptoms, such as confusion about oneself and others and the environment, aggressive behavior, and lack of identity coherence (Irani, 2018).

The meaning in life is another variable that can be a measure of an individual’s psychological health. The meaning in life is defined as “the amount of value that individuals feel in their lives” (Arbab et al., 2021). Discovering or creating meaning, engaging in a useful and creative task, having an intimate relationship with others, and accepting unavoidable suffering responsibly (Caligor et al., 2007). One of the ways to discover or create meaning is to find the meaning of life through relationships with others, which is also called the relational meaning in life. Relational meaning in life is introduced as “the extent to which individuals define the meaning of their lives based on their relationship with others” (Arbab et al., 2021).

In this study, the quality of object relations, personality organization, personal meaning of life, and relational meaning in life were compared between psychology students of Lahijan Azad University and other groups of this university. Initially, to collect samples, the students completed the BORRTI, Kernberg’s IPO, Steger’s MLQ, and RMLQ. Then, the data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods, and the main hypotheses were tested through hypothesis testing.

This study hypothesized that psychology students would have higher quality object relations, higher levels of personality organization, and experience more meaningful lives compared to other university students. However, the results showed that the status of psychology students at the Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch, in terms of the quality of object relations is not significantly different from students of other groups of the university, and both groups obtained similar scores, rejecting the research hypothesis.

However, in the personality organization variable, psychology students obtained better grades than other students, although this difference was mainly related to the reality testing subscale. Little difference was observed between psychology students and other students in the two other subscales of kernberg’s personality inventory. One possible reason for this improvement in grades can be found in the knowledge of psychology students who did not honestly answer the questions related to the reality testing subscale and presented a better self-image. On the other hand, given that a large part of the psychological sample consisted of master’s students, the likelihood of obtaining lower scores in the reality testing subscale decreases.

In the end, in the two variables of meaning in life and relational meaning in life, the performance of psychology students was better than other students. According to the results of this study, psychology students experience more meaningful lives than other students at the Islamic Azad University of Lahijan City. The root of this grade improvement can be found in the psychology profession. A field whose primary goal is to help other humans and whose borders are vast can provide a wealthy source of meaning in life. On the other hand, the relationship-centered nature of this field, which inevitably expands the communication skills of its graduates, can be a great source of relational meaning in life (Ahmadi Marvili et al., 2019).

Conclusion

The present study compares the relationship between object relations, personality organization, personal meaning in life, and relational meaning in the life of psychology students with other students of the Islamic Azad University Lahijan campus. No significant difference is observed between the quality of object relations of psychology students and students of other fields; a significant difference is observed in the level of personality organization between psychology students and students of other fields; a significant difference is observed in the personal meaning of life between psychology students and students of other fields; and also a significant difference is observed in the relational meaning in life between psychology students and students of other fields.

Limitations and suggestions

Considering the difficulty of controlling extraneous variables in behavioral studies, controlling such variables, including parenting style, sources of support, academic level of psychology students, history of receiving psychotherapy, etc. was also challenging in this study, and it is recommended to control for these variables in future studies.

In addition, one of the main limitations of using questionnaires is the honesty of participants and the ability of the questionnaire to measure a psychological variable; therefore, it is recommended that future research use clinical interviews to determine the personality organization, meaning of life, and object relations of individuals in the study.

Future researchers should use self-reported questionnaires and clinical interviews to collect more accurate information. It is also suggested that research be repeated in larger samples and universities with stricter academic standards and entry criteria so that the samples of each group are more representative of their respective groups.

On the other hand, to ensure that the sample of psychology students is more representative of the psychology community than ever before, it is recommended to limit the study to master’s and PhD students so that the impact of studying psychology on research variables is more pronounced. It is also recommended that some intervention variables, such as parenting style, having or not having children, history of receiving psychotherapy, and the approach that an individual learns in psychology students be examined and controlled in future research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current research was confirmed in the Research Ethics Committees of the Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch (Code: IR.IAU.TON.REC.1401.068). Participants were asked to read the participant information and to consent before entering the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master's thesis of Mahyar Arzpeyma, approved by Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Lahijan Branch.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their deep appreciation for the invaluable assistance provided by Amirsam Kianimoghadam, and Sirvan Asmaeemajd.

References

Ahmadi Marvili, N., Mirzahoseini, H., & Monirpoor, N. (2019). [The prediction model of self- harm behaviors and tendency to suicide in adolescence based on attachment styles and personality organization: Mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychological Research, 10(3), 101-117. [DOI:10.22059/JAPR.2019.274866.643162]

Allebehbahani, M., & Mohammadi, N. (2007). [Examination of psychometric properties of Kernberg’s personality organization inventory ( Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 185-197. [Link]

Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: Facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 755-768. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20583] [PMID]

Arbab, H., Mirzahoseini, H., & Monirpour, N. (2021). [Predicting pathological substance use relapse based on object-relations and personality organization in male addicts treated with methadone (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal(RRJ), 10(5), 173-184. [Link]

Bell, M. D. (2007). Bell object relations and reality testing inventory: BORRTI. Western Psychological Services. [Link]

Caligor, E., Kernberg, O. F., & Clarkin, J. F. (2007). Handbook of dynamic psychotherapy for higher level personality pathology. Washington: American Psychiatric Pub. [Link]

Das, A. K. (1998). Frankl and the realm of meaning. The Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 36(4), 199-211. [DOI:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1998.tb00392.x]

Delgadillo, J., Branson, A., Kellett, S., Myles-Hooton, P., Hardy, G. E., & Shafran, R. (2020). Therapist personality traits as predictors of psychological treatment outcomes. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 857-870. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2020.1731927] [PMID]

Diguer, L., Pelletier, S., Hébert, É., Descôteaux, J., Rousseau, J. P., & Daoust, J. P. (2004). Personality organizations, psychiatric severity, and self and object representations. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21(2), 259-275. [DOI:10.1037/0736-9735.21.2.259]

Fonagy, P., Target, M., & Gergely, G. (2006). Psychoanalytic perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (pp. 701–749). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Link]

Frankl, N. (1985) Man's search for meaning [A. Kheirabadi, Persian. Tehran: Tehran University Publications. [Link]

Irani, Z., & Bakhtiari, S. (2018). [The role of personality organization and psychological basic psychological needs in predicting malformed body-seem attempters admitted to cosmetic surgery (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Surgery, 25(4), 66-74. [Link]

Jamil, L., Atef Vahid, M., Dehghani, M., & Habibi, M. (2015). [The mental health through psychodynamic perspective: The relationship between the ego strength, the defense styles, and the object relations to mental health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 21(2), 144-154. [Link]

Kelly, F. D. (2014).The assessment of object relations phenomena in adolescents: Tat and rorschach measu. New York: Routledge.[DOI:10.4324/9781315805931]

Lenzenweger, M. F., Clarkin, J. F., Kernberg, O. F., & Foelsch, P. A. (2001). The inventory of personality organization: psychometric properties, factorial composition, and criterion relations with affect, aggressive dyscontrol, psychosis proneness, and self-domains in a nonclinical sample. Psychological Assessment, 13(4), 577-591. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.13.4.577] [PMID]

Majdabadi, Z. (2017). Meaning in life questionnaire (Persian)]. Developmental Psychology (Journal of Iranian Psychologists) 13(51), 331-333. [Link]

Mesgarian, F., Azad Fallah, P., Farahani, H., & Ghorbani, N. (2017). [Object relations and defense mechanisms in social anxiety (Persian)]. Journal of Developmnetal Psychology, 14(53), 3-14. [Link]

Mesrabadi, J., Jafariyan, S., & Ostovar, N. (2013). Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 83-90. [Link]

Mohammad Nia, S., & Mashhadi, A. (2018). [The effect of meaning of life on the relationship between attitude toward substance abuse and depression (Persian)]. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam, 6(3), 43-51. [DOI:10.29252/shefa.6.3.43]

Rostami Y. (2018). [Schopenhauer on the meaning of life: An evaluation (Persian)]. Philosophy of Religion Research (Namah-I Hikmat). 16(1), 109-126. [DOI: 10.30497/PRR.2018.2351]

Sipowicz, K., Podlecka, M., & Pietras, T. (2021). Logotherapy-an attempt to establish a new dialogue with one’s own life. Kwartalnik Naukowy Fides et Ratio, 46(2), 261-269.[DOI:10.34766/fetr.v46i2.811]

St Clair M. (2007). Object relations and self psychology: An introduction [A.Tahmasb, & H. Aliaghaei, Persian trans.). Tehran: Ney. [Link]

Stadter M. (2009). Object relations brief therapy: The therapeutic relationship in short-term work: Jason Aronson; 2009. [Link]

Steger, M. F. (2010). MLQ description scoring and feedback packet [Internet]. Retrieved from [Link]

Topolinski, S., & Hertel, G. (2007). The role of personality in psychotherapists’ careers: Relationships between personality traits, therapeutic schools, and job satisfaction. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 365-375. [DOI:10.1080/10503300600830736]

Tremblay, J. M., Herron, W. G., & Schultz, C. L. (1986). Relation between therapeutic orientation and personality in psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 17(2), 106–110. [DOI:10.1037/0735-7028.17.2.106]

Van, H. L., Hendriksen, M., Schoevers, R. A., Peen, J., Abraham, R. A., & Dekker, J. (2008). Predictive value of object relations for therapeutic alliance and outcome in psychotherapy for depression: An exploratory study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(9), 655-662. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318183f8c2] [PMID]

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books. [Link]

Yu, E. A., & Chang, E. C. (2021). Relational meaning in life as a predictor of interpersonal well-being: A prospective analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110377. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110377]

Yu, E. A., & Chang, E. C. (2021). Construction of the relational meaning in life questionnaire: An exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic study of relational meaning. Current Psychology, 40, 1746-1751. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Analytical approach

Received: 2023/05/8 | Accepted: 2023/06/13 | Published: 2023/10/28

Received: 2023/05/8 | Accepted: 2023/06/13 | Published: 2023/10/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |