Volume 11, Issue 4 (Autumn 2023)

PCP 2023, 11(4): 307-318 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kamjou S, Goodarzi M A, Aflakseir A. Predicting College Students’ Mental Health Based on Religious Faith Mediated by Happiness, Ambivalent Attachment Style, and Locus of Control. PCP 2023; 11 (4) :307-318

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-872-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-872-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. , sarakamjou@gmail.com

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 699 kb]

(1417 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3525 Views)

Full-Text: (935 Views)

1. Introduction

Mental health, which is essential to pay attention to its role in guaranteeing and improving the individual and social life, has been much discussed and focused on by psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors in recent years (Totunchi et al., 2012). The mental health concept is an aspect of the concept of health. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Health is a multidimensional concept that includes the feeling of happiness and well-being in addition to not being sick (Poursardar et al., 2012). According to previous theories and studies, a wide range of factors can be involved in mental health or disorder, some of the vital of which will be discussed in this study based on the presented model.

Psychologists have paid special attention to the role of religion in providing mental health and treating mental illnesses. The WHO has examined health from four basic aspects, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual, among which spirituality is considered an influential variable (Park et al., 2021; You et al., 2019; Klundt et al., 2021; Karin et al., 2021). Despite the importance of the relationship between religion and mental health, only a few studies have been globally conducted in this field. However, the amount of study in the field of spirituality and mental health is slightly more. Thus, it is necessary to conduct more comprehensive studies in the field of examining the relationship between religion and mental health to be used, especially in the field of clinical psychology and health.

Happiness is another factor affecting mental health. Happiness is not the opposite of depression, but the absence of depression is a necessary condition for happiness. According to Argyle believes if happiness is the absolute opposite of depression, it is not required to measure and investigate it, because depression is well known (Hills & Argyle, 2002). As the importance of happiness in mental health and well-being, as well as its effect in strengthening the mental strength of mankind is becoming increasingly known, the attention of researchers, scientists, and even the common people is changing towards it. Based on the studies, a statistically significant relationship has been observed between the levels of happiness and psychological symptoms (Natvig et al., 2003). In addition, it seems that religion and, especially the internal religious orientation plays the role of a defensive shield for individuals, and creates a wide range of positive psychological effects (Sediqi Arfai, 2012). However, despite all the studies, happiness is still in its infancy (Schimmel, 2009). Despite the importance of mental health and the role of happiness, it seems that happiness is the missing factor of mental health in our society and needs more comprehensive studies. Additionally, several studies have pointed out the role of religiosity in happiness (Sahraian et al., 2013, and Abdel khakak, 2014); therefore, investigating the relationship between faith and happiness leads to a better understanding of this pattern.

Another influential factor in fulfilling people’s mental health is the type of attachment formed in people (Dobson et al., 2022; Nottage et al., 2022). Attachment is the deep emotional connection that we have with special people in our lives. Three styles of secure attachment, insecure-avoidant attachment, and insecure-ambivalent attachment are recognized. Secure, avoidant, and ambivalent people use completely different strategies to regulate emotions and process emotional information, the use of which will have a different effect on the person, leading to mental health or disorder (Shaver et al., 2005). Also, Rowatt and Kirkpatrick believe that religion can be conceptualized as an attach- ment process in which religious behaviors and beliefs act as an extensive attachment system in humans (Rowatt & Kirkpatrick, 2002). Kirkpatrick believes that the idea of God can be a substitute for the initial failures of secure attachment transformation (Khavaninzade et al., 2005); therefore, by understanding the relationship between mental health and attachment style, and faith and attachment style, we can improve mental health.

The last variable affecting mental health in this study is the locus of control. The locus of control refers to people’s beliefs about how to control the environment, which is divided into two internal and external categories. Introverts believe that skill, effort, and responsible behavior lead to positive outcomes and vice versa. Extrinsic people believe that events are determined by chance, the power of others, and unknown and uncontrollable factors (Ratter, 1966). The association between mental illnesses and locus of control was central to many scholarly studies (Lloyd & Hastings, 2009). A belief with which person has enough ability to achieve desired outcome when he or she becomes ill mentally or physically is called internal health locus of control. This belief is a major determinant in people’s reaction to mental and physical illnesses. Comparing with external locus of control, it has been found that in both physical and mental illnesses having internal locus of control is a positive predictors in coping with diseases (Shelley & Pakenham, 2004). However, the relationship between religion and locus of control is contradictory, and little study has been conducted in this field. Followers of religions solve their problems with God’s control and mediation, and on the surface, it seems that these people have external control, but some studies (for example, Rastegar & Heidari, 2013) indicate more internal control among religious people, for the enlightenment of which this study will be conducted. It is possible to prevent mental disorders and reduce their prevalence by studying the causes and variables involved in mental health. Mental health is not only essential in prevention but also in improving the condition and functioning of people suffering from any disorder.

Many studies have examined factors affecting mental health, but no study has examined these factors together in a structured or modeled manner to gain a deeper understanding. Besides producing and transferring knowledge, universities must also address college students’ behavioral and psychological problems. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that health problems are prevalent in the entire world, especially among college students (Azad & Azadi, 2012). Therefore, this study focused on this group. This study was conducted to investigate some crucial mental health anticipants among college students. These anticipants include religious faith, happiness, attachment styles, and locus of control, which are selected according to the effective factors in mental health and studying the theoretical and study topics implemented in the proposed model based on literature reviews. The precedence of faith over other factors is due to its strong background which has been proven in mental health studies; also, its effect on other variables is the reason for choosing faith as the predictive variable. Since all study variables lead to mental health or lack of mental health, this variable is dependent and therefore considered as the criterion variable. The order of the first and last variables influencing mental health and influenced by religious faith as happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control have been selected based on the study background. This study was conducted to predict college students’ mental health based on religious faith, with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study was descriptive correlational. In this study, to evaluate the measured variables, multiple regression, path analysis methods, and structural equation modeling were used. The study population included all the college students of Shiraz University who were studying in 2013-2014. A number of 240 college students were selected from the study population using a convenience sampling method to conduct this study. The number of members in the study sample was determined based on Stevens’ suggestion (Hooman, 2013) that there should be at least 15 members in the study sample for each direct route.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included age from 18 to 40 years and a willingness to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria included having a psychotic illness, substance abuse (as reported by the individual), and failing to complete the questionnaire.

General health questionnaire (GHQ-28)

The general health questionnaire (GHQ) by Goldberg and Hillier (1979) was used in this study, the main form of which has 60 items, and short sheets have been prepared with 12 to 28 items. In Iran, the 28-item form is standardized and used. In this questionnaire, the range of scores is between 0 to 84. The reliability of the said questionnaire was checked by three methods, test re-test, split-half, and Cronbach’s α, its reliability coefficients were measured as 0.70, 0.93, and 0.90, respectively. To check validity, concurrent validity of this questionnaire was performed through simultaneous implementation with the Middlesex hospital questionnaire (MHQ) and the resulting correlation coefficient was 0.55 (Taqavi, 2001).

Religious faith scale (RFS)

This 25-item Religious faith scale (RFS) by Goudarzi (2014) was created to measure the objective and behavioral aspects of religious faith. The internal consistency coefficients of the religious faith questionnaire and its subscales range from 0.67 to 0.86. Cronbach’s α for 25 items was reported as 0.81. In the divergent validity of the religious faith scale, it is mentioned that this scale has a correlation of 0.49 with the Beck depression inventory and -0.53 with the Beck hopelessness inventory. In the discussion of convergent validity, this questionnaire has shown a correlation coefficient of 0.92 with the “beliefs and rituals” component of the religious orientation test based on Islam. In this questionnaire, the score range is between 0 to 100. (Goudarzi, 2014).

Oxford happiness inventory (OHI)

The 29-item Oxford happiness inventory (OHI) was created by Michael Argyle in 1989 to measure individual happiness (Hills & Argyle, 2002). They have reported the reliability of the Oxford questionnaire using Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.91. The inter-item correlations for the OHI ranged from 0.03 to 0.58, mean 0.28, and the corresponding values for the OHQ were 0.04 to 0.65, mean 0.28. The concurrent validity of this questionnaire was calculated at 0.43 using the evaluation of subjects’ friends about them (Hills & Argyle, 2002). Alipour and Aghah Harris (2007) showed that all 29 items of this scale had a high correlation with the total score to assess the validity and reliability of the Oxford happiness scale. Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was equal to 0.91. In this questionnaire, the range of scores is between 0 to 87.

Collins and Read revised adult attachment scale (RAAS)

This revised adult attachment scale (RAAS) includes a self-assessment of relationship-building skills and self-description of the way of forming attachment relationships with close attachment figures and is measured using a 5-point Likert scale of 1 to 5, and consists of 18 items. The scale used in this study consists of three subscales, dependence, closeness, and anxiety. Each subscale has six items and the total score of each subscale is 24. For this research, just the anxiety subscale is used. Hazen and Shaver (1987) found the total re-test validity of this scale to be 0.81 and the Cronbach’s α of the scale to be 0.78. The internal validity of this tool in the study of Rahimian Boger et al., (2008) for the whole test, anxious, avoidant, and secure styles were respectively, 0.75, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.77, which means a good validity (Safaei et al., 2011).

Rotter’s locus of control scale (RLCS)

This 29-item Rotter’s locus of control scale was developed by Ratter (1966) and can be utilized to understand the internal or external locus of control. The 29-item version contains six filler items to make the purpose of the test ambiguous. Items representing external choices are summed, yielding a range from 0 to 23. Higher scores indicate greater levels of external locus of control. The initial reliability coefficient of the locus of control scale is 0.65 using the split-half method, 0.73 using the Kuder–Richardson method, and 0.72 when using the re-test method with a time interval of one month. In Iran, the test re-test reliability coefficient is 0.75 and its α coefficient is reported as 0.70. Cronbach’s α coefficient is equal to 0.84 and the concurrent validity coefficient of this scale with Coopersmith’s self-esteem scale and Piers-Harris self-concept scale has been obtained as 0.61 and 0.72, respectively (Fadaei et al., 2011).

Study procedure

To comply with the ethical principles of the study, before the implementation of the study plan, explanations were given to the participants about the objectives of the study and its necessity. Voluntary participation is also mentioned. The confidentiality of the information with the researcher was also explained to the participants. They were also asked to write their E-mails in the questionnaire if they wanted to have the results of the questionnaires.

3. Results

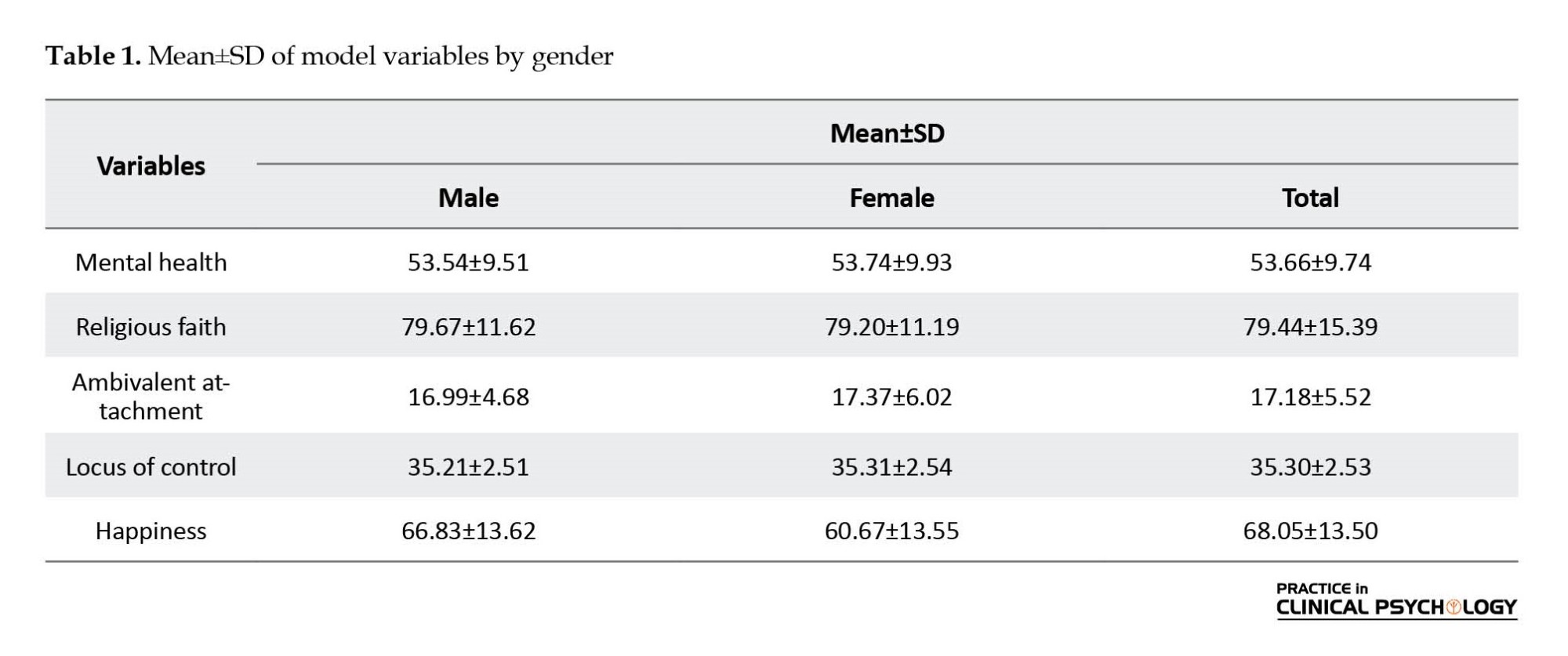

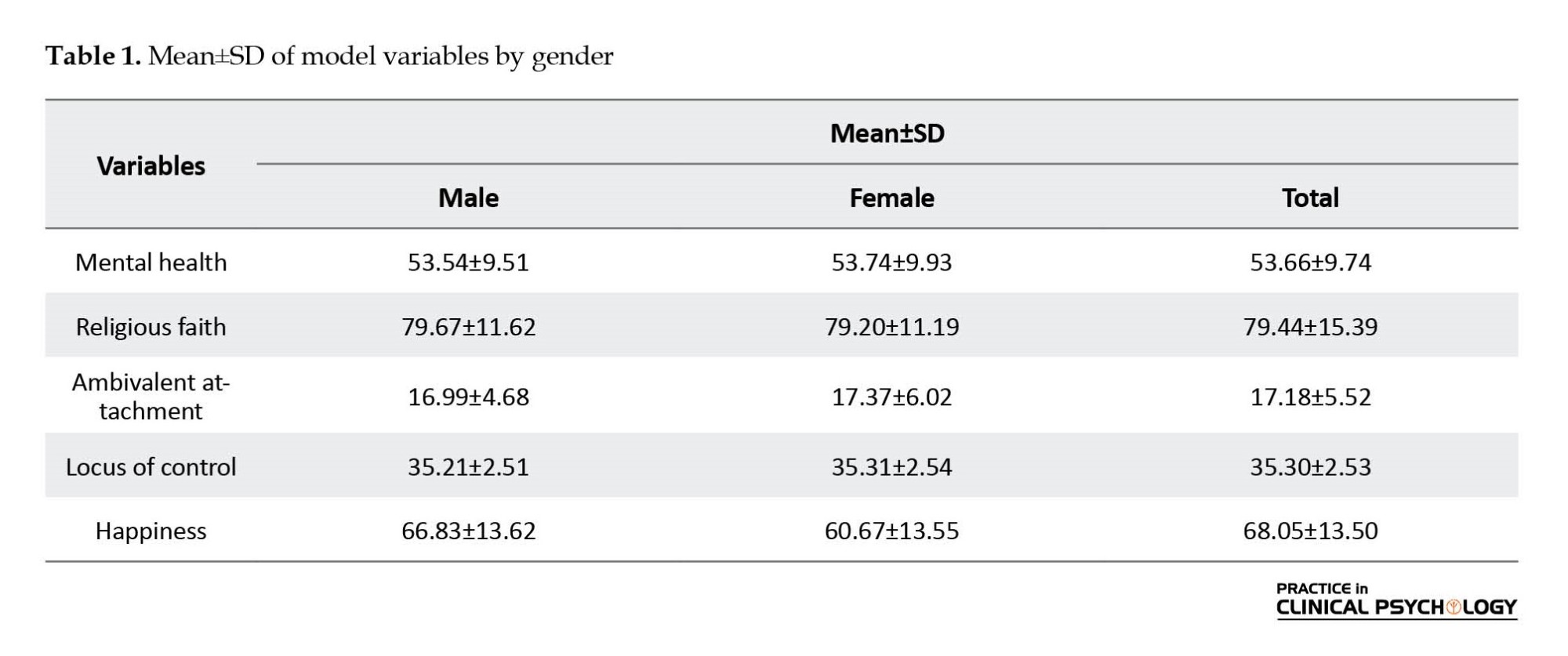

To familiarize with the descriptive information of this study, Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of the study variables.

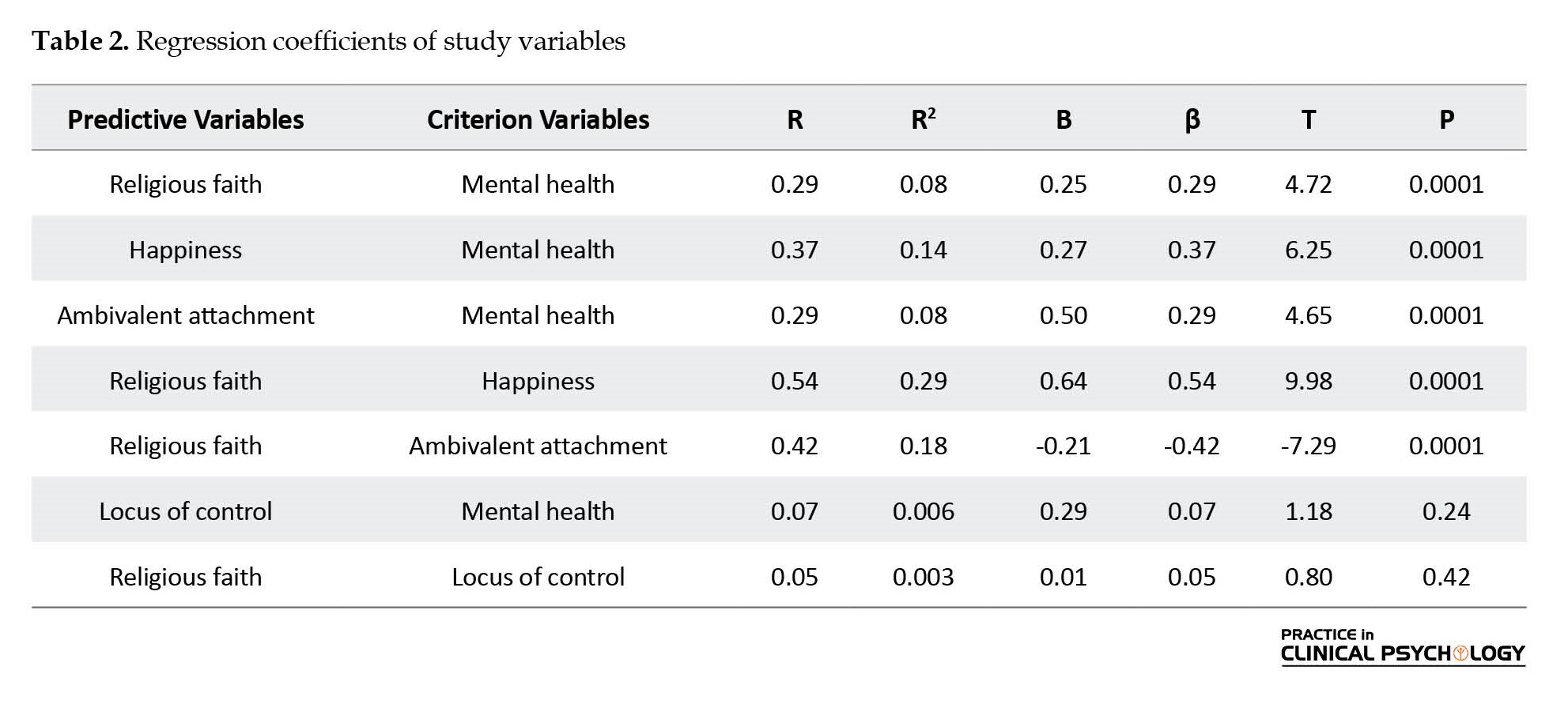

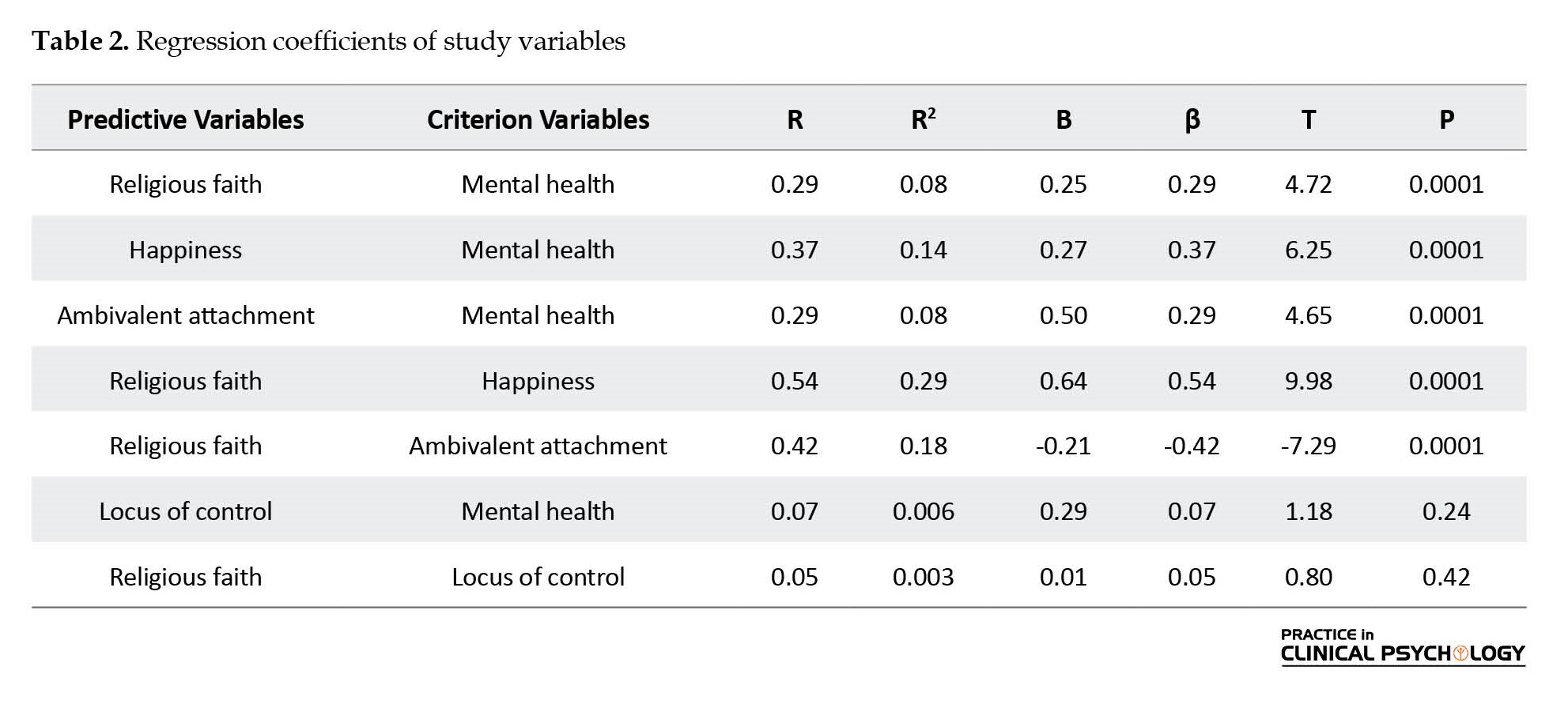

To assess the proposed model, first, the regression coefficients of the study variables were checked, the results of which are reported in Table 2.

The results of the study showed that the variables of religious faith (P=0.0001, β=0.29), happiness variable (P=0.0001, β=0.37) and ambivalent attachment (P=0.0001, β=0.29) can positively and significantly predict mental health. Likewise, religious faith positively and significantly predicted happiness (P=0.0001, β=0.54) and negatively and significantly predicted ambivalent attachment (P=0.0001, β=-0.21). The locus of control could not predict religious faith and the religious faith could not predict the locus of control.

Next, the structural equation modeling method was established to investigate the effect of religious faith on mental health with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and happiness. First, the whole model was examined using the general fit indices, and in the second step, the regression weights of the direct, indirect, and total effects measurement models were calculated, in which the mediating role of ambivalent attachment style and locus of control was not confirmed.

First, a 9-index model was considered for the overall fit of the model. Then, some modifications were made to achieve a better fit for the model, so that the fit indices after the modification showed the desired fit as reported in Table 3. Using the modified model, the goodness of fit for the model was good, so that the hypothesis concerning religious faith and mental health is confirmed through happiness as a mediator.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to predict college students’ mental health based on religious faith, with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control.

The results showed that the intensity of religious faith positively predicts mental health in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Meisenhelder et al. (2013), Rippentrop et al. (2005), Johnstone et al. (2012), Janssen et al. (2005), Arefi and Mohsenzadeh (2011), Solati et al., (2011), Janbozorgi (2007), Park et al., (2021), You et al., (2019), Klundt et al. (2021), Karin et al. (2021) and inconsistent with the study results of O’Connor et al. (2003). To explain this result, it can be said that based on the cognitive model, religion, religious, and spiritual beliefs, and attitudes affect people’s cognitive components, including the interpretation of events, optimism or pessimism, and their type of thinking, and these components also affect the body and mental health of human through the nervous and mental immune system. Another explanation can be given based on the relationship between the search for meaning and the purposefulness of life, as the foundation and main pillar of spirituality, and mental health. In other words, the main factor of spirituality and faith is the feeling of purposefulness and meaningfulness of life, and since a positive relationship is observed between purposefulness and meaningfulness of life and mental health, it can be concluded that the activation of concepts of meaningfulness and purposefulness of life through faith can lead to improved mental health.

Also, the intensity of happiness positively predicted mental health in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Parnegar et al., (2004), Yiengprugsawan et al. (2012), Rafiei et al., (2011), Khoshkonesh, and Keshavarz Afshar (2008), Abdel-khalek (2007) and Abdel-khalek (2014), and Golzari (2010). To explain the effect of happiness on mental health, it can be said that usually people seek happiness, and happiness is especially crucial in people’s lives (King & Napa, 1998; Skevington et al., 2011), while experiencing stress, significantly reduces the happiness. The more stress people experience, the less happiness they have and the more their mental health is threatened (King et al., 2014).

As another result of the study, the ambivalent attachment style negatively predicted mental health in college students. These results are consistent with the study results of Neria et al. (2001), Raque-Bogdan et al. (2011), Chen (2009), Rahimian Boger et al. (2008), Flannelly and Galek (2010), Ghobari Bonab and Hadadi (2011), Dabson et al., (2022), and Nottage et al., (2022). To justify this relationship, Roberts et al., (1996) believe that the psychological consequence of insecure attachment styles in stressful situations is anxiety and depression, and the psychological consequence of secure attachment style is mental peace. Cassidy (1999) believes that people with ambivalent attachment styles have negative and relatively inflexible inter-psychological models that make the person weak in various functions and as a re- sult, the person uses ineffective and unrealistic strategies to process their thoughts, feelings, and self-evaluations, which can stop a person’s flexibility when problems arise and provide the basis for the creation and continu- ation of psychological vulnerabilities.

The intensity of religious faith also positively predicts happiness in college students. This is consistent with the studies conducted by Snoep (2008), Mookerjee and Beron (2005), Rosmarin et al. (2009), Sahraian et al. (2013) Rouhani and Manavipour (2008), Abdel-khalek (2007), Abdel-khalek (2014), and Golzari (2010). To explain this result, it can be stated that believing in a God who controls the situations and watches over his servants, reduces anxiety to a great extent, in such a way that most religious people believe that uncontrollable situations can be controlled somehow by relying on and appealing to God. It seems that religious orientation can lead to a feeling of happiness. (Koivumaa-Hankanen et al., 2001).

Furthermore, the intensity of religious faith negatively predicted the ambivalent attachment style in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1992), Granqvist and Hagekull (2000), ZarinKelk and Tabatabai (2012), Khavaninzadeh et al. (2005), Flannelly and Galek (2010), Ghobari Bonab and Haddadi Kohsar (2011). To explain the effect of ambivalent attachment style on religious faith, it can be said that according to attachment theory, ambivalence and avoidance (insecure attachments) are types of strategies that are used to moderate attachment-related anxiety, but since these strategies are not considered a beneficial solution, the individuals cannot experience true intimacy with their loved ones. On the same page, people with insecure attachment to the religious field are considered atheists or consider God inaccessible (Kirkpatrick and Shaver, 1992).

As another result of the study, the intensity of religious faith proved to fail in predicting the locus of control in college students. These results are inconsistent with the studies conducted by Coursey and Kenworthy (2013), Cirhinlioglu and Ozdikmenli-Demir (2012), Asghari et al., (2013), Koushki and Khalilifar (2009), Ryan and Francis (2012) and Salehi et al., (2007) and consistent to that of Mirhashemian (1999). This inconsistency may be due to a subtle point in the concept of trust in God. It means that although faithful people personally try to solve their problems (internal control), they leave the final arrangement of affairs in the hands of God (external control). Moreover, sociological causes can also be involved in this matter. As an example, the item “I envy people who have fixers to solve their problems,” which indicates less faith, is not necessarily related to people with external control, and due to the prevailing conditions in society, people with both internal and external control can confirm this issue.

Religious faith affects mental health through happiness. It can be said that believing that there is a God who controls situations and watches over his servants reduces anxiety to a great extent (reducing anxiety is one of the main components of mental health), so that most religious people describe their relationship with God as a very close friend, and believe that uncontrollable situations can be somehow controlled by relying on God. It seems that religious orientation can lead to happiness. A personal relationship with a supreme being causes a positive outlook in life (Koivumaa-Hankanen et al., 2001). Faith can be considered as a shield against difficulties and a factor in happiness. A religion can give meaning and purpose to a person’s life (Myers & Diener, 1995) and as seen in the present study, happiness can be a mediating variable between mental health and faith. It can be concluded that not necessarily any type of religion and faith but a type of faith that is associated with happiness can lead to mental health.

Religious faith also did not predict mental health through ambivalent attachment style. In the explanation of this lack of effect, it can be suggested that although ambivalent attachment style has an inverse correlation with religious faith, the direct effect of faith on mental health, as well as the inverse effect of ambivalent attachment style on mental health were insufficient; this path had no statistically significant result.

Religious faith affects mental health through locus of control. Since none of the direct paths from the locus of control to mental health and from religious faith to the locus of control were significant and these two hypotheses were rejected, it is sensible that the hypothesis related to the effect of religious faith on mental health through the locus of control be removed and not confirmed.

To explain this result, the points mentioned in explaining why the intensity of religious belief did not predict the locus of control can be used.

5. Conclusion

The modified model confirmed the mediating role of happiness between religious faith and mental health. Therefore, those components of faith that lead to happiness may be a protective marker for mental health. Since our society is religious, and improving individuals’ mental health is one of the vital goals of psychology, identifying the factors and variables between these two, including happiness, will be an effective step in improving the lives of people in society, especially in therapy sessions. Besides, this information helps psychologists formulate therapeutic and preventive plans.

Suggestions and study limitations

Considering future studies, similar studies should be conducted on other groups of people to be able to generalize the results. Moreover, other variables in this model may also play a mediation role. Therefore, future studies may consider it. Considering the limitations of this study, it should be mentioned that the method of the current study was correlational. Therefore, the causal relationship should not be obtained. Besides, the sampling method was not random. Therefore, it is essential to be cautious when generalizing.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and could volunteer to collaborate to fill the questionnaires, and if desired, the study results would be available to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the Master's thesis of Sara Kamjou, approved by Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University.

Authors' contributions

Sara Kamjou and Mohammad Ali Goudarzi equally contributed to preparing this article and Abdul Aziz Aflakseir did the editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2014). Happiness, health and religiosity: Significant associations among Lebanese adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(1), 30-38. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2012.742047]

Abdel-Khalek, M. (2007). Religiosity, happiness, health, and psychopathology in a probability sample of Muslim adolescents. Mental Healthh, Religion & Culture, 10(6), 571-583. [DOI:10.1080/13674670601034547]

Arefi, M., Mohsenzadeh, F. (2011). [Relationship between religious orientation, mental health and gender (Persian)]. Women’s Journal: Rights and Development (Women’s Research), 5(3), 126-141. [Link]

Asghari, F., Kurdmirza, E., & Ahmadi, L. (2013). [The relationship between religious attitudes, locus of control and tendency to substace abuse in university students (Persian)]. Addiction Research Journal, 7(25), 103-112. [Link]

Azadi, S., & Azad, H. (2012). [The correlation of social support, tolerance and mental health in children of martyrs and war-disabled in universities of Ilam (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health, 12(3), 48-58. [Link]

Cassidy, J. (1999). The Nature of the childs Ties. Handbook of attachment, theory and research and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Chen, X. l. (2009). Relationship among achievement goal, academic self-efficacy and academic cheating of college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(2), 243–245. [Link]

Cirhinlioglu, F. G., & Ozdikmenli-Demir, G. (2012). Religious orientation and its relation to locus of control and depression. Archive for the Psychology of Religions, 34(3), 341-362. [DOI:10.1163/15736121-12341245]

Coursey L. E., Kenworthy, J. B., Jones, J. R. (2013). A meta-analysis of the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and locus of control. Archive for the Psychology of Religions, 35(3), 347-368. [DOI:10.1163/15736121-12341268]

Dobson, O., Price, E. L., & DiTommaso, E. (2022). Recollected caregiver sensitivity and adult attachment interact to predict mental health and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 187, 111398. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111398]

Fadaei, Z., Ashuri, A., Houshiari, Z., & Izanlou, B. (2011). [The path analysis of locus of control, depressive symptoms and academic achievement on suicidal ideation: The moderating role of gender (Persian)]. Journal of Principles of Mental Health, 13(2), 148-159. [Link]

Flannelly, J. K., & Galek, K. (2010). Religion, evolution, and mental health: Attachment theory and ETAS Theory. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(3), 337–350. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-009-9247-9] [PMID]

GhobariBonab, B., & HaddadiKohsar, A. A. (2011). [The relationship between mental health and the mental image of God and the quality of attachment in delinquent teenagers (Persian)]. Journal of Mentality and Behaviour, 6(21), 7-16. [Link]

Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139-145. [PMID]

Golzari, M. (2010). [The effect of Umrah on students’ mental health, happiness and adherence to religious beliefs. Two-quarterly scientific-specialist (Persian)]. Journals of Islamic Studies and Psychology, 4(7), 111-126. [Link]

Goudarzi, M. A. (2023). [Construction and preliminary validation of religious faith scale among students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. [Unpublished].

Granqvist, P., & Hagekull, B. (2000). Religiosity, adult attachment, and why “singles” are more religious.The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10(2), 111-123. [DOI:10.1207/S15327582IJPR1002_04]

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511] [PMID]

Hooman, H. (2014). [Understanding the scientific method in behavioral sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: SAMT Publishing. [Link]

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2002). The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(7), 1073-1082. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00213-6]

Janbozorgi, M. (2007). [Religious orientation and mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Medicine, 31( 4), 350-345. [Link]

Janssen, F., Banziger, S., Denzutter, J., & Hutsebaut, D. (2005). Religion and mental health: Aspects of the relation between religious measures and positive and negative mental health. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 27(1), 19-44. [DOI:10.1163/008467206774355402]

Johnstone, B., Yoon, D. P., Cohen, D., Schopp, L. H., McCormack, G., & Campbell, J., et al. (2012). Relationships among spirituality, religious practices, personality factors, and health for five different faith traditions. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4), 1017-1041. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-012-9615-8] [PMID]

Khavaninzadeh, M., Ejei, J., & Mazaheri, M. A. (2005). [Comparison of attachment style of students with internal and external religious orientations (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 9(3), 228-247. [Link]

Khoshkonesh, A., & KeshavarzAfshar, H. (2008). [Relationship between happiness and mental health of students (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 2(7), 41-52. [Link]

King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Merianous, A., & Singh, M. (2014). A study of stress, social support, and perceived happiness among college students. Journal of Happiness Well-being, 2(2), 132-144. [Link]

King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 156-165. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.156] [PMID]

Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1992). An attachment-theoritical aproach to romantic love and religious belief. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 266-275. [DOI:10.1177/0146167292183002]

Klundt, J. S., Erekson, D. M., Lynn, A. M., Brown, H. E. (2021). Sexual minorities, mental health, and religiosity at a religiously conservative university. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110475. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110475]

Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Honkanen, R., Viinamäki, H., Heikkilä, K., Kaprio, J., & Koskenvuo, M. (2001). Life satisfaction and suicide: A 20 year follow up study. National Library of Medicine, 158(3), 433-439. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.433] [PMID]

Koushki, Sh., & Khalilifar, M. (2009). [Religious attitude and locus of control (Persian)]. Thought and Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 4(15), 33-40. [Link]

Lloyd, T., & Hastings, R, P. (2009). Parental locus of control and psychological well-being in mothers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(2), 104-115. [PMID]

Meisenhelder, J. B., Schaeffer, N. J., Younger, J., & Lauria, M. (2013). Faith and mental health in an oncology population. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 505-513. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-011-9497-1] [PMID]

Mirhashemian, H. (1999). [Religious beliefs in formation of the locus of control and psychological profile of Tehran university students (Persian)]. Journal of Epistemological Studies in Islamic University, 2(4), 69-80. [Link]

Mookerjee, R., & Beron, K. (2005). Gender, religion and happiness. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 34(5), 674-685. [DOI:10.1016/j.socec.2005.07.012]

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6(1), 10-19. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00298.x]

Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstrøm, U. (2003). Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. International Journal of Nusrsing Practice, 9 (3), 166-175. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00419.x] [PMID]

Neria, Y., Guttmann-Steinmetz, S., Koenen, K., Levinovsky, L., Zakin, G., & Dekel, R. (2001). Do attachment and hardiness relate to each other and to mental health in real life stress? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(6), 844-858. [DOI:10.1177/0265407501186006]

Nottage, M. K., Oei, N. Y. L., Wolters, N., Klein, A., Heijde, C. M. V., & Vonk, P., et al. (2022). Loneliness mediates the association between insecure attachment and mental health among university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111233. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111233]

O’Connor, D. B., Cobb, J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2003) Religiosity, stress and psychological distress: No evidence for an association among undergraduate students. Personality & Individual Differences, 34(2), 211-217. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00035-1]

Park, C. L., Sacco, S. J., Kraus, S. W., Mazure, C. M., & Hoff, R. A. (2021). Influences of religiousness/spirituality on mental and physical health in OEF/OIF/OND military veterans varies by sex and race/ethnicity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 138, 15-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.034] [PMID]

Pernegar, T. V., Hudelson, P. M., & Bovier, P. A. (2004). [Health and happiness in young Swiss adults. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 13(1), 171-178. [DOI:10.1023/B:QURE.0000015314.97546.60] [PMID]

Poursardar, N., Poursardar, F., Panahande, A., Sangari, A. A., & Zarrin, S. (2013). [The effect of optimism (positive thinking) on mental health and life satisfaction: A psychological model of well-being (Persian)]. Hakim Research Journal, 16(1), 42-49. [Link]

Rafiei, M., Mousavipour, S., & Aghajani, M. (2012). [Happiness, mental health, and their relationship among the students at Arak University of Medical Sciences in 2010. (Persian)]. Journal of Arak University of Medical Sciences, 15(3), 13-25. [Link]

Rahimian Boger, E., AsgharnejadFarid, A. A., & RahimiNejad, A. (2008). [Relationship between attachment style and mental health in adult survivors of the Bam earthquake (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Research, 11(1-2), 27-40. [Link]

Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Ericson, S. K., Jackson, J., Martin, H. M., & Bryan, N. A. (2011). Attachment and mental and physical health: Self-compassion and mattering as mediators. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 272–278. [DOI:10.1037/a0023041] [PMID]

Rastegar, M., & Heidari, N. (2013). The relationship between locus of control, test anxiety, and religious orientation among Iranian EFL Students. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 3(1), 73-78. [DOI:10.4236/ojml.2013.31009]

Ratter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1-28. [DOI:10.1037/h0092976]

Rippentrop, E. A., Altmaier, E. M., Chen, J. J., Found, E. M., & Keffala, V. J. (2005). The relationship between religion/spirituality and physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain, 116(3), 311–321. [DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.008] [PMID]

Roberts, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 310–320. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.310] [PMID]

Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2009). The role of religiousness in anxiety, depression, and happiness in a Jewish community sample: A preliminary investigation. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 12(2), 97-113. [DOI:10.1080/13674670802321933]

Rouhani, A., & Manavipour, D. (2008). [The relationship between practicing religious beliefs and happiness and marital satisfaction in Islamic Azad University, Mobarakeh branch (Persian)]. Journal of Science and Research in Psychology, 35-36, 189-206. [Link]

Rowatt, W., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2002). Two dimensions of attachment to god and their relation to affect, religiosity, and personality constructs. Journal for the Scientific of Religion, 41(4), 637-651. [DOI:10.1111/1468-5906.00143]

Ryan, E. M., & Francis, J. A. (2012). Locus of control beliefs mediate the relationship between religious functioning and psychological health. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 774–785. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-010-9386-z] [PMID]

Safaei, S., Bigdali, I., Talepasand, S. (2011). [The relationship between mother’s self-concept and attachment style and child’s self-concept (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Research Journal, 1(2), 39-52. [Link]

Sahraian, A., Gholami, A., Javadpour, A., & Omidvar, B. (2013). Association between religiosity and happiness among a group of Muslim undergraduate students. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 450-453. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-011-9484-6] [PMID]

Salehi, L., Soleimanizadeh, L., BagheriYazdi, S. A., & Abbaszadeh, A. (2007). [The relationship between religious beliefs and locus of control, and mental health in college students (Persian)]. Qazvin Journal of Medical Sciences, 11(1), 50-55. [Link]

Schimmel, J. (2009). Development as happiness: The subjective perception of happiness and UNDP’s analysis of poverty, wealth and development. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 93-111. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-007-9063-4]

SediqiArfai, F., Tamanaeifar, M. R., AbedinAbadi, A. (2012). [The relationship between religious orientation, coping styles and happiness in college students (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology and Religion, 5(3), 135-165. [Link]

Shaver, P. R., Schachner, D. A., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 343-359. [DOI:10.1177/0146167204271709] [PMID]

Shelley, M., & Pakenham, K. I. (2004). External health locus of control and general self-efficacy: Moderators of emotional distress among university students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 56(3), 191-199. [Link]

Skevington, S. M., Mac Arthur, P., & Somerset, M. (2011). Developing items for the WHOQOL: An investigation of contemporary beliefs about quality of life related to health in Britain. Health Psychology, 2(1), 55-72. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8287.1997.tb00523.x]

Snoep, L. (2008). Religiousness and happiness in three nations: A research note. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 207-211. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-007-9045-6]

Solati, S. K., Rabiei, M., Shariati, M. (2011). [The relationship between religious orientation and mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Qom University of Medical Sciences, 5(3). [Link]

Taqavi, M. (2001). [Validity and reliability of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in college students of Shiraz Universi1y (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 5(4), 381-398. [Link]

Thomas, K., Lyndes, K., & Jackson, K. (2021). The perception of religious coping and health related quality of life in the case of an ALS caregiver during covid-19. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 102(10), e16-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.07.438]

Totunchi, M., Samani, S., ZandiQashqaei, K. (2012). [The mediating role of self-concept for perfectionism and mental health in Shiraz adolescents (Persian)]. Journal of Fasa University of Medical Sciences, 2, 210-217.

Yiengprugsawan, V., Somboonsook, B., Seubsman, S. A., & Sleigh, A. C. (2012). Happiness, mental health and socio-demographic associations among a national cohort of thai adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1019–1029.[DOI:10.1007/s10902-011-9304-4] [PMID]

You, S., You, J. E., & Koh, Y. (2019). Religious practices and mental health outcomes among Korean adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 142, 7-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.026]

ZarinKelk, H. R., & TabatabaiBarzouki, S. (2012). [The relationship between attachment style and perceived parenting methods and spiritual experiences and religious practices (Persian)]. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 31(8), 305-313. [Link]

Mental health, which is essential to pay attention to its role in guaranteeing and improving the individual and social life, has been much discussed and focused on by psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors in recent years (Totunchi et al., 2012). The mental health concept is an aspect of the concept of health. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Health is a multidimensional concept that includes the feeling of happiness and well-being in addition to not being sick (Poursardar et al., 2012). According to previous theories and studies, a wide range of factors can be involved in mental health or disorder, some of the vital of which will be discussed in this study based on the presented model.

Psychologists have paid special attention to the role of religion in providing mental health and treating mental illnesses. The WHO has examined health from four basic aspects, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual, among which spirituality is considered an influential variable (Park et al., 2021; You et al., 2019; Klundt et al., 2021; Karin et al., 2021). Despite the importance of the relationship between religion and mental health, only a few studies have been globally conducted in this field. However, the amount of study in the field of spirituality and mental health is slightly more. Thus, it is necessary to conduct more comprehensive studies in the field of examining the relationship between religion and mental health to be used, especially in the field of clinical psychology and health.

Happiness is another factor affecting mental health. Happiness is not the opposite of depression, but the absence of depression is a necessary condition for happiness. According to Argyle believes if happiness is the absolute opposite of depression, it is not required to measure and investigate it, because depression is well known (Hills & Argyle, 2002). As the importance of happiness in mental health and well-being, as well as its effect in strengthening the mental strength of mankind is becoming increasingly known, the attention of researchers, scientists, and even the common people is changing towards it. Based on the studies, a statistically significant relationship has been observed between the levels of happiness and psychological symptoms (Natvig et al., 2003). In addition, it seems that religion and, especially the internal religious orientation plays the role of a defensive shield for individuals, and creates a wide range of positive psychological effects (Sediqi Arfai, 2012). However, despite all the studies, happiness is still in its infancy (Schimmel, 2009). Despite the importance of mental health and the role of happiness, it seems that happiness is the missing factor of mental health in our society and needs more comprehensive studies. Additionally, several studies have pointed out the role of religiosity in happiness (Sahraian et al., 2013, and Abdel khakak, 2014); therefore, investigating the relationship between faith and happiness leads to a better understanding of this pattern.

Another influential factor in fulfilling people’s mental health is the type of attachment formed in people (Dobson et al., 2022; Nottage et al., 2022). Attachment is the deep emotional connection that we have with special people in our lives. Three styles of secure attachment, insecure-avoidant attachment, and insecure-ambivalent attachment are recognized. Secure, avoidant, and ambivalent people use completely different strategies to regulate emotions and process emotional information, the use of which will have a different effect on the person, leading to mental health or disorder (Shaver et al., 2005). Also, Rowatt and Kirkpatrick believe that religion can be conceptualized as an attach- ment process in which religious behaviors and beliefs act as an extensive attachment system in humans (Rowatt & Kirkpatrick, 2002). Kirkpatrick believes that the idea of God can be a substitute for the initial failures of secure attachment transformation (Khavaninzade et al., 2005); therefore, by understanding the relationship between mental health and attachment style, and faith and attachment style, we can improve mental health.

The last variable affecting mental health in this study is the locus of control. The locus of control refers to people’s beliefs about how to control the environment, which is divided into two internal and external categories. Introverts believe that skill, effort, and responsible behavior lead to positive outcomes and vice versa. Extrinsic people believe that events are determined by chance, the power of others, and unknown and uncontrollable factors (Ratter, 1966). The association between mental illnesses and locus of control was central to many scholarly studies (Lloyd & Hastings, 2009). A belief with which person has enough ability to achieve desired outcome when he or she becomes ill mentally or physically is called internal health locus of control. This belief is a major determinant in people’s reaction to mental and physical illnesses. Comparing with external locus of control, it has been found that in both physical and mental illnesses having internal locus of control is a positive predictors in coping with diseases (Shelley & Pakenham, 2004). However, the relationship between religion and locus of control is contradictory, and little study has been conducted in this field. Followers of religions solve their problems with God’s control and mediation, and on the surface, it seems that these people have external control, but some studies (for example, Rastegar & Heidari, 2013) indicate more internal control among religious people, for the enlightenment of which this study will be conducted. It is possible to prevent mental disorders and reduce their prevalence by studying the causes and variables involved in mental health. Mental health is not only essential in prevention but also in improving the condition and functioning of people suffering from any disorder.

Many studies have examined factors affecting mental health, but no study has examined these factors together in a structured or modeled manner to gain a deeper understanding. Besides producing and transferring knowledge, universities must also address college students’ behavioral and psychological problems. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that health problems are prevalent in the entire world, especially among college students (Azad & Azadi, 2012). Therefore, this study focused on this group. This study was conducted to investigate some crucial mental health anticipants among college students. These anticipants include religious faith, happiness, attachment styles, and locus of control, which are selected according to the effective factors in mental health and studying the theoretical and study topics implemented in the proposed model based on literature reviews. The precedence of faith over other factors is due to its strong background which has been proven in mental health studies; also, its effect on other variables is the reason for choosing faith as the predictive variable. Since all study variables lead to mental health or lack of mental health, this variable is dependent and therefore considered as the criterion variable. The order of the first and last variables influencing mental health and influenced by religious faith as happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control have been selected based on the study background. This study was conducted to predict college students’ mental health based on religious faith, with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study was descriptive correlational. In this study, to evaluate the measured variables, multiple regression, path analysis methods, and structural equation modeling were used. The study population included all the college students of Shiraz University who were studying in 2013-2014. A number of 240 college students were selected from the study population using a convenience sampling method to conduct this study. The number of members in the study sample was determined based on Stevens’ suggestion (Hooman, 2013) that there should be at least 15 members in the study sample for each direct route.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included age from 18 to 40 years and a willingness to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria included having a psychotic illness, substance abuse (as reported by the individual), and failing to complete the questionnaire.

General health questionnaire (GHQ-28)

The general health questionnaire (GHQ) by Goldberg and Hillier (1979) was used in this study, the main form of which has 60 items, and short sheets have been prepared with 12 to 28 items. In Iran, the 28-item form is standardized and used. In this questionnaire, the range of scores is between 0 to 84. The reliability of the said questionnaire was checked by three methods, test re-test, split-half, and Cronbach’s α, its reliability coefficients were measured as 0.70, 0.93, and 0.90, respectively. To check validity, concurrent validity of this questionnaire was performed through simultaneous implementation with the Middlesex hospital questionnaire (MHQ) and the resulting correlation coefficient was 0.55 (Taqavi, 2001).

Religious faith scale (RFS)

This 25-item Religious faith scale (RFS) by Goudarzi (2014) was created to measure the objective and behavioral aspects of religious faith. The internal consistency coefficients of the religious faith questionnaire and its subscales range from 0.67 to 0.86. Cronbach’s α for 25 items was reported as 0.81. In the divergent validity of the religious faith scale, it is mentioned that this scale has a correlation of 0.49 with the Beck depression inventory and -0.53 with the Beck hopelessness inventory. In the discussion of convergent validity, this questionnaire has shown a correlation coefficient of 0.92 with the “beliefs and rituals” component of the religious orientation test based on Islam. In this questionnaire, the score range is between 0 to 100. (Goudarzi, 2014).

Oxford happiness inventory (OHI)

The 29-item Oxford happiness inventory (OHI) was created by Michael Argyle in 1989 to measure individual happiness (Hills & Argyle, 2002). They have reported the reliability of the Oxford questionnaire using Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.91. The inter-item correlations for the OHI ranged from 0.03 to 0.58, mean 0.28, and the corresponding values for the OHQ were 0.04 to 0.65, mean 0.28. The concurrent validity of this questionnaire was calculated at 0.43 using the evaluation of subjects’ friends about them (Hills & Argyle, 2002). Alipour and Aghah Harris (2007) showed that all 29 items of this scale had a high correlation with the total score to assess the validity and reliability of the Oxford happiness scale. Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was equal to 0.91. In this questionnaire, the range of scores is between 0 to 87.

Collins and Read revised adult attachment scale (RAAS)

This revised adult attachment scale (RAAS) includes a self-assessment of relationship-building skills and self-description of the way of forming attachment relationships with close attachment figures and is measured using a 5-point Likert scale of 1 to 5, and consists of 18 items. The scale used in this study consists of three subscales, dependence, closeness, and anxiety. Each subscale has six items and the total score of each subscale is 24. For this research, just the anxiety subscale is used. Hazen and Shaver (1987) found the total re-test validity of this scale to be 0.81 and the Cronbach’s α of the scale to be 0.78. The internal validity of this tool in the study of Rahimian Boger et al., (2008) for the whole test, anxious, avoidant, and secure styles were respectively, 0.75, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.77, which means a good validity (Safaei et al., 2011).

Rotter’s locus of control scale (RLCS)

This 29-item Rotter’s locus of control scale was developed by Ratter (1966) and can be utilized to understand the internal or external locus of control. The 29-item version contains six filler items to make the purpose of the test ambiguous. Items representing external choices are summed, yielding a range from 0 to 23. Higher scores indicate greater levels of external locus of control. The initial reliability coefficient of the locus of control scale is 0.65 using the split-half method, 0.73 using the Kuder–Richardson method, and 0.72 when using the re-test method with a time interval of one month. In Iran, the test re-test reliability coefficient is 0.75 and its α coefficient is reported as 0.70. Cronbach’s α coefficient is equal to 0.84 and the concurrent validity coefficient of this scale with Coopersmith’s self-esteem scale and Piers-Harris self-concept scale has been obtained as 0.61 and 0.72, respectively (Fadaei et al., 2011).

Study procedure

To comply with the ethical principles of the study, before the implementation of the study plan, explanations were given to the participants about the objectives of the study and its necessity. Voluntary participation is also mentioned. The confidentiality of the information with the researcher was also explained to the participants. They were also asked to write their E-mails in the questionnaire if they wanted to have the results of the questionnaires.

3. Results

To familiarize with the descriptive information of this study, Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of the study variables.

To assess the proposed model, first, the regression coefficients of the study variables were checked, the results of which are reported in Table 2.

The results of the study showed that the variables of religious faith (P=0.0001, β=0.29), happiness variable (P=0.0001, β=0.37) and ambivalent attachment (P=0.0001, β=0.29) can positively and significantly predict mental health. Likewise, religious faith positively and significantly predicted happiness (P=0.0001, β=0.54) and negatively and significantly predicted ambivalent attachment (P=0.0001, β=-0.21). The locus of control could not predict religious faith and the religious faith could not predict the locus of control.

Next, the structural equation modeling method was established to investigate the effect of religious faith on mental health with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and happiness. First, the whole model was examined using the general fit indices, and in the second step, the regression weights of the direct, indirect, and total effects measurement models were calculated, in which the mediating role of ambivalent attachment style and locus of control was not confirmed.

First, a 9-index model was considered for the overall fit of the model. Then, some modifications were made to achieve a better fit for the model, so that the fit indices after the modification showed the desired fit as reported in Table 3. Using the modified model, the goodness of fit for the model was good, so that the hypothesis concerning religious faith and mental health is confirmed through happiness as a mediator.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to predict college students’ mental health based on religious faith, with the mediation of happiness, ambivalent attachment style, and locus of control.

The results showed that the intensity of religious faith positively predicts mental health in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Meisenhelder et al. (2013), Rippentrop et al. (2005), Johnstone et al. (2012), Janssen et al. (2005), Arefi and Mohsenzadeh (2011), Solati et al., (2011), Janbozorgi (2007), Park et al., (2021), You et al., (2019), Klundt et al. (2021), Karin et al. (2021) and inconsistent with the study results of O’Connor et al. (2003). To explain this result, it can be said that based on the cognitive model, religion, religious, and spiritual beliefs, and attitudes affect people’s cognitive components, including the interpretation of events, optimism or pessimism, and their type of thinking, and these components also affect the body and mental health of human through the nervous and mental immune system. Another explanation can be given based on the relationship between the search for meaning and the purposefulness of life, as the foundation and main pillar of spirituality, and mental health. In other words, the main factor of spirituality and faith is the feeling of purposefulness and meaningfulness of life, and since a positive relationship is observed between purposefulness and meaningfulness of life and mental health, it can be concluded that the activation of concepts of meaningfulness and purposefulness of life through faith can lead to improved mental health.

Also, the intensity of happiness positively predicted mental health in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Parnegar et al., (2004), Yiengprugsawan et al. (2012), Rafiei et al., (2011), Khoshkonesh, and Keshavarz Afshar (2008), Abdel-khalek (2007) and Abdel-khalek (2014), and Golzari (2010). To explain the effect of happiness on mental health, it can be said that usually people seek happiness, and happiness is especially crucial in people’s lives (King & Napa, 1998; Skevington et al., 2011), while experiencing stress, significantly reduces the happiness. The more stress people experience, the less happiness they have and the more their mental health is threatened (King et al., 2014).

As another result of the study, the ambivalent attachment style negatively predicted mental health in college students. These results are consistent with the study results of Neria et al. (2001), Raque-Bogdan et al. (2011), Chen (2009), Rahimian Boger et al. (2008), Flannelly and Galek (2010), Ghobari Bonab and Hadadi (2011), Dabson et al., (2022), and Nottage et al., (2022). To justify this relationship, Roberts et al., (1996) believe that the psychological consequence of insecure attachment styles in stressful situations is anxiety and depression, and the psychological consequence of secure attachment style is mental peace. Cassidy (1999) believes that people with ambivalent attachment styles have negative and relatively inflexible inter-psychological models that make the person weak in various functions and as a re- sult, the person uses ineffective and unrealistic strategies to process their thoughts, feelings, and self-evaluations, which can stop a person’s flexibility when problems arise and provide the basis for the creation and continu- ation of psychological vulnerabilities.

The intensity of religious faith also positively predicts happiness in college students. This is consistent with the studies conducted by Snoep (2008), Mookerjee and Beron (2005), Rosmarin et al. (2009), Sahraian et al. (2013) Rouhani and Manavipour (2008), Abdel-khalek (2007), Abdel-khalek (2014), and Golzari (2010). To explain this result, it can be stated that believing in a God who controls the situations and watches over his servants, reduces anxiety to a great extent, in such a way that most religious people believe that uncontrollable situations can be controlled somehow by relying on and appealing to God. It seems that religious orientation can lead to a feeling of happiness. (Koivumaa-Hankanen et al., 2001).

Furthermore, the intensity of religious faith negatively predicted the ambivalent attachment style in college students. This result is consistent with the study results of Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1992), Granqvist and Hagekull (2000), ZarinKelk and Tabatabai (2012), Khavaninzadeh et al. (2005), Flannelly and Galek (2010), Ghobari Bonab and Haddadi Kohsar (2011). To explain the effect of ambivalent attachment style on religious faith, it can be said that according to attachment theory, ambivalence and avoidance (insecure attachments) are types of strategies that are used to moderate attachment-related anxiety, but since these strategies are not considered a beneficial solution, the individuals cannot experience true intimacy with their loved ones. On the same page, people with insecure attachment to the religious field are considered atheists or consider God inaccessible (Kirkpatrick and Shaver, 1992).

As another result of the study, the intensity of religious faith proved to fail in predicting the locus of control in college students. These results are inconsistent with the studies conducted by Coursey and Kenworthy (2013), Cirhinlioglu and Ozdikmenli-Demir (2012), Asghari et al., (2013), Koushki and Khalilifar (2009), Ryan and Francis (2012) and Salehi et al., (2007) and consistent to that of Mirhashemian (1999). This inconsistency may be due to a subtle point in the concept of trust in God. It means that although faithful people personally try to solve their problems (internal control), they leave the final arrangement of affairs in the hands of God (external control). Moreover, sociological causes can also be involved in this matter. As an example, the item “I envy people who have fixers to solve their problems,” which indicates less faith, is not necessarily related to people with external control, and due to the prevailing conditions in society, people with both internal and external control can confirm this issue.

Religious faith affects mental health through happiness. It can be said that believing that there is a God who controls situations and watches over his servants reduces anxiety to a great extent (reducing anxiety is one of the main components of mental health), so that most religious people describe their relationship with God as a very close friend, and believe that uncontrollable situations can be somehow controlled by relying on God. It seems that religious orientation can lead to happiness. A personal relationship with a supreme being causes a positive outlook in life (Koivumaa-Hankanen et al., 2001). Faith can be considered as a shield against difficulties and a factor in happiness. A religion can give meaning and purpose to a person’s life (Myers & Diener, 1995) and as seen in the present study, happiness can be a mediating variable between mental health and faith. It can be concluded that not necessarily any type of religion and faith but a type of faith that is associated with happiness can lead to mental health.

Religious faith also did not predict mental health through ambivalent attachment style. In the explanation of this lack of effect, it can be suggested that although ambivalent attachment style has an inverse correlation with religious faith, the direct effect of faith on mental health, as well as the inverse effect of ambivalent attachment style on mental health were insufficient; this path had no statistically significant result.

Religious faith affects mental health through locus of control. Since none of the direct paths from the locus of control to mental health and from religious faith to the locus of control were significant and these two hypotheses were rejected, it is sensible that the hypothesis related to the effect of religious faith on mental health through the locus of control be removed and not confirmed.

To explain this result, the points mentioned in explaining why the intensity of religious belief did not predict the locus of control can be used.

5. Conclusion

The modified model confirmed the mediating role of happiness between religious faith and mental health. Therefore, those components of faith that lead to happiness may be a protective marker for mental health. Since our society is religious, and improving individuals’ mental health is one of the vital goals of psychology, identifying the factors and variables between these two, including happiness, will be an effective step in improving the lives of people in society, especially in therapy sessions. Besides, this information helps psychologists formulate therapeutic and preventive plans.

Suggestions and study limitations

Considering future studies, similar studies should be conducted on other groups of people to be able to generalize the results. Moreover, other variables in this model may also play a mediation role. Therefore, future studies may consider it. Considering the limitations of this study, it should be mentioned that the method of the current study was correlational. Therefore, the causal relationship should not be obtained. Besides, the sampling method was not random. Therefore, it is essential to be cautious when generalizing.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and could volunteer to collaborate to fill the questionnaires, and if desired, the study results would be available to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the Master's thesis of Sara Kamjou, approved by Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University.

Authors' contributions

Sara Kamjou and Mohammad Ali Goudarzi equally contributed to preparing this article and Abdul Aziz Aflakseir did the editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2014). Happiness, health and religiosity: Significant associations among Lebanese adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(1), 30-38. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2012.742047]

Abdel-Khalek, M. (2007). Religiosity, happiness, health, and psychopathology in a probability sample of Muslim adolescents. Mental Healthh, Religion & Culture, 10(6), 571-583. [DOI:10.1080/13674670601034547]

Arefi, M., Mohsenzadeh, F. (2011). [Relationship between religious orientation, mental health and gender (Persian)]. Women’s Journal: Rights and Development (Women’s Research), 5(3), 126-141. [Link]

Asghari, F., Kurdmirza, E., & Ahmadi, L. (2013). [The relationship between religious attitudes, locus of control and tendency to substace abuse in university students (Persian)]. Addiction Research Journal, 7(25), 103-112. [Link]

Azadi, S., & Azad, H. (2012). [The correlation of social support, tolerance and mental health in children of martyrs and war-disabled in universities of Ilam (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health, 12(3), 48-58. [Link]

Cassidy, J. (1999). The Nature of the childs Ties. Handbook of attachment, theory and research and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Chen, X. l. (2009). Relationship among achievement goal, academic self-efficacy and academic cheating of college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(2), 243–245. [Link]

Cirhinlioglu, F. G., & Ozdikmenli-Demir, G. (2012). Religious orientation and its relation to locus of control and depression. Archive for the Psychology of Religions, 34(3), 341-362. [DOI:10.1163/15736121-12341245]

Coursey L. E., Kenworthy, J. B., Jones, J. R. (2013). A meta-analysis of the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and locus of control. Archive for the Psychology of Religions, 35(3), 347-368. [DOI:10.1163/15736121-12341268]

Dobson, O., Price, E. L., & DiTommaso, E. (2022). Recollected caregiver sensitivity and adult attachment interact to predict mental health and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 187, 111398. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111398]

Fadaei, Z., Ashuri, A., Houshiari, Z., & Izanlou, B. (2011). [The path analysis of locus of control, depressive symptoms and academic achievement on suicidal ideation: The moderating role of gender (Persian)]. Journal of Principles of Mental Health, 13(2), 148-159. [Link]

Flannelly, J. K., & Galek, K. (2010). Religion, evolution, and mental health: Attachment theory and ETAS Theory. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(3), 337–350. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-009-9247-9] [PMID]

GhobariBonab, B., & HaddadiKohsar, A. A. (2011). [The relationship between mental health and the mental image of God and the quality of attachment in delinquent teenagers (Persian)]. Journal of Mentality and Behaviour, 6(21), 7-16. [Link]

Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139-145. [PMID]

Golzari, M. (2010). [The effect of Umrah on students’ mental health, happiness and adherence to religious beliefs. Two-quarterly scientific-specialist (Persian)]. Journals of Islamic Studies and Psychology, 4(7), 111-126. [Link]

Goudarzi, M. A. (2023). [Construction and preliminary validation of religious faith scale among students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. [Unpublished].

Granqvist, P., & Hagekull, B. (2000). Religiosity, adult attachment, and why “singles” are more religious.The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10(2), 111-123. [DOI:10.1207/S15327582IJPR1002_04]

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511] [PMID]

Hooman, H. (2014). [Understanding the scientific method in behavioral sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: SAMT Publishing. [Link]

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2002). The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(7), 1073-1082. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00213-6]

Janbozorgi, M. (2007). [Religious orientation and mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Medicine, 31( 4), 350-345. [Link]

Janssen, F., Banziger, S., Denzutter, J., & Hutsebaut, D. (2005). Religion and mental health: Aspects of the relation between religious measures and positive and negative mental health. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 27(1), 19-44. [DOI:10.1163/008467206774355402]

Johnstone, B., Yoon, D. P., Cohen, D., Schopp, L. H., McCormack, G., & Campbell, J., et al. (2012). Relationships among spirituality, religious practices, personality factors, and health for five different faith traditions. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4), 1017-1041. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-012-9615-8] [PMID]

Khavaninzadeh, M., Ejei, J., & Mazaheri, M. A. (2005). [Comparison of attachment style of students with internal and external religious orientations (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 9(3), 228-247. [Link]

Khoshkonesh, A., & KeshavarzAfshar, H. (2008). [Relationship between happiness and mental health of students (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 2(7), 41-52. [Link]

King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Merianous, A., & Singh, M. (2014). A study of stress, social support, and perceived happiness among college students. Journal of Happiness Well-being, 2(2), 132-144. [Link]

King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 156-165. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.156] [PMID]

Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1992). An attachment-theoritical aproach to romantic love and religious belief. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 266-275. [DOI:10.1177/0146167292183002]

Klundt, J. S., Erekson, D. M., Lynn, A. M., Brown, H. E. (2021). Sexual minorities, mental health, and religiosity at a religiously conservative university. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110475. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110475]

Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Honkanen, R., Viinamäki, H., Heikkilä, K., Kaprio, J., & Koskenvuo, M. (2001). Life satisfaction and suicide: A 20 year follow up study. National Library of Medicine, 158(3), 433-439. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.433] [PMID]

Koushki, Sh., & Khalilifar, M. (2009). [Religious attitude and locus of control (Persian)]. Thought and Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 4(15), 33-40. [Link]

Lloyd, T., & Hastings, R, P. (2009). Parental locus of control and psychological well-being in mothers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(2), 104-115. [PMID]

Meisenhelder, J. B., Schaeffer, N. J., Younger, J., & Lauria, M. (2013). Faith and mental health in an oncology population. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 505-513. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-011-9497-1] [PMID]

Mirhashemian, H. (1999). [Religious beliefs in formation of the locus of control and psychological profile of Tehran university students (Persian)]. Journal of Epistemological Studies in Islamic University, 2(4), 69-80. [Link]

Mookerjee, R., & Beron, K. (2005). Gender, religion and happiness. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 34(5), 674-685. [DOI:10.1016/j.socec.2005.07.012]

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6(1), 10-19. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00298.x]

Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstrøm, U. (2003). Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. International Journal of Nusrsing Practice, 9 (3), 166-175. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00419.x] [PMID]

Neria, Y., Guttmann-Steinmetz, S., Koenen, K., Levinovsky, L., Zakin, G., & Dekel, R. (2001). Do attachment and hardiness relate to each other and to mental health in real life stress? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(6), 844-858. [DOI:10.1177/0265407501186006]

Nottage, M. K., Oei, N. Y. L., Wolters, N., Klein, A., Heijde, C. M. V., & Vonk, P., et al. (2022). Loneliness mediates the association between insecure attachment and mental health among university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111233. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111233]

O’Connor, D. B., Cobb, J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2003) Religiosity, stress and psychological distress: No evidence for an association among undergraduate students. Personality & Individual Differences, 34(2), 211-217. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00035-1]

Park, C. L., Sacco, S. J., Kraus, S. W., Mazure, C. M., & Hoff, R. A. (2021). Influences of religiousness/spirituality on mental and physical health in OEF/OIF/OND military veterans varies by sex and race/ethnicity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 138, 15-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.034] [PMID]

Pernegar, T. V., Hudelson, P. M., & Bovier, P. A. (2004). [Health and happiness in young Swiss adults. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 13(1), 171-178. [DOI:10.1023/B:QURE.0000015314.97546.60] [PMID]

Poursardar, N., Poursardar, F., Panahande, A., Sangari, A. A., & Zarrin, S. (2013). [The effect of optimism (positive thinking) on mental health and life satisfaction: A psychological model of well-being (Persian)]. Hakim Research Journal, 16(1), 42-49. [Link]

Rafiei, M., Mousavipour, S., & Aghajani, M. (2012). [Happiness, mental health, and their relationship among the students at Arak University of Medical Sciences in 2010. (Persian)]. Journal of Arak University of Medical Sciences, 15(3), 13-25. [Link]

Rahimian Boger, E., AsgharnejadFarid, A. A., & RahimiNejad, A. (2008). [Relationship between attachment style and mental health in adult survivors of the Bam earthquake (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Research, 11(1-2), 27-40. [Link]

Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Ericson, S. K., Jackson, J., Martin, H. M., & Bryan, N. A. (2011). Attachment and mental and physical health: Self-compassion and mattering as mediators. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 272–278. [DOI:10.1037/a0023041] [PMID]

Rastegar, M., & Heidari, N. (2013). The relationship between locus of control, test anxiety, and religious orientation among Iranian EFL Students. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 3(1), 73-78. [DOI:10.4236/ojml.2013.31009]

Ratter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1-28. [DOI:10.1037/h0092976]

Rippentrop, E. A., Altmaier, E. M., Chen, J. J., Found, E. M., & Keffala, V. J. (2005). The relationship between religion/spirituality and physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain, 116(3), 311–321. [DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.008] [PMID]

Roberts, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 310–320. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.310] [PMID]