Volume 11, Issue 2 (Spring 2023)

PCP 2023, 11(2): 117-130 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghaderi F, Akrami N, Namdari K, Abedi A. Investigating the Effectiveness of Transdiagnostic Treatment on Maladaptive Personality Traits and Mentalized Affectivity of Patients With Generalized Anxiety Disorder Comorbid With Depression: A Case Study. PCP 2023; 11 (2) :117-130

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-848-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-848-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. , ghaderi68@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

Keywords: Transdiagnostic treatment, Generalized anxiety disorder, Depression, Comorbidity, Personality traits, Mentalized affectivity

Full-Text [PDF 1180 kb]

(1360 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3349 Views)

Full-Text: (1500 Views)

1. Introduction

People with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are constantly worried about the possible occurrence of a wide range of negative events (APA, 2020). They expect unfortunate events to occur and become irritable while experiencing a lot of muscle contractions and may have trouble sleeping and concentrating. Their psychosocial function is likely to be severely impaired as well (Koenigsberg, 2021). GAD is associated with increased disability, cognitive impairment, life dissatisfaction, and low productivity in patients (Bower et al., 2016). The mean 12-month prevalence for the disorder is 1.3% worldwide, with a range of 0.2% to 4.3% (APA, 2022). A recent study in Iran reported a 2.6% lifetime prevalence of GAD (Mohammadiet al., 2020).

A total of 90% of people with GAD experience at least one form of psychological disorder (Blanco et al., 2014). This disorder has high comorbidity with other anxiety disorders and depression (Sadock et al., 2015; Shihata et al., 2017). Leahy et al. (2011) reported a 42% comorbidity rate of GAD and depression. Recent meta-analytic findings regarding the comorbidity between anxiety disorders and depression show that regardless of changes in the type of diagnosis, study timeframe, and chronological order of occurrence, mood disorders, and anxiety are strongly comorbid (Saha et al., 2021). Comorbidity reduces the accurate diagnosis, thereby reducing the effectiveness of treatment methods. It also increases treatment costs (Sharpley et al., 2010). As a result, therapists should pay attention to the quick identification and treatment of this common type of comorbid disorder (Saha et al., 2021). Regardless that which of the two disorders occurs first, the risk of subsequently developing the other disorder increases (Saha et al., 2021). This reciprocal relationship in comorbid disorders shows that these disorders may be due to common risk factors (Levey et al., 2020; Purves et al., 2020, Saha et al., 2021).

Emotion regulation has been suggested as a common factor in the psychopathology of GAD comorbid with depression (Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). Emotion regulation is a wide-ranging term that describes explicit and implicit processes which involve monitoring, evaluating, altering, and modulating emotions. The process of emotion regulation involves being aware, understanding, and identifying one’s thoughts and feelings (i.e.mentalization), before, during, and after refining and modulating the emotion (Greenberg et al., 2017). People with GAD experience intense emotions, tend to catastrophize, may not be able to correctly recognize and understand their emotions, and have problems suppressing their negative emotions (Mennin & Fresco, 2010; Tryon, 2014).

Jurist (2018) proposed a novel perspective on emotion regulation, called the theory of mentalized affectivity, which considers mentalization in the regulatory process. This theory argues that effectively regulating (managing, altering, or changing) an emotion relies on the capacity for mentalization. It argues that emotions are not just adjusted in a regulatory process, but they are also revalued in meaning. This more sophisticated aspect of emotion regulation requires the ability to reflect on one’s thoughts and feelings and to mentalize the factors that may influence the emotion, such as childhood experiences or the present situation, or the context in which a person is. This in turn helps to inform a person’s understanding of their emotions and how to anticipate future situations. Mentalized affectivity, as one of the new models and new assessment of emotion regulation, divides emotional regulation into 3 components: identifying emotions (the ability to identify emotions and to reflect on the factors that influence them); processing emotions (the ability to modulate and distinguish complex emotions); and expressing emotions (the tendency to express emotions outwardly or inwardly) (Greenberg et al., 2017). According to the mental affectivity model, emotional regulation is influenced by personality style, values, culture, personal history, and most importantly, mentalities (Jurist, 2018). According to the research results of Greenberg et al. (2017), individuals with anxiety, mood, and personality disorders show a profile of high identifying and low processing when compared to the control group.

Also, personality structures, such as neuroticism, negative affectivity, behavioral inhibition, positive affect, and extroversion are inherited traits that have a significant relationship with anxiety and related disorders. Maladaptive personality traits, especially neuroticism and negative affectivity are risk factors for divorce, unemployment, and disability-related retirement. They are influential in the prevalence, course, and occurrence of mental disorders. They cause functional impairment, act as an obstacle to improving symptoms and improvement in common mental disorders, and cause resistance to treatment, lack of response to treatment, and poor treatment outcomes (Hergatner, 2015). The clinical importance of the relationship between anxiety disorders and personality disorders can be assessed through its effects on the severity of anxiety disorders, the risk of suicide, and the process of anxiety disorders, as well as treatment outcomes (Latas & Milovanovic, 2014). Studies have shown that the lowest level of personality functioning among anxiety patients is related to patients with GAD (Doering, 2018). A significant part of the factor structure of the diagnostic classification of mental disorders is negative affectivity. This factor overlaps considerably with the main components of GAD. High levels of negative affectivity and low levels of positive affectivity are the basis for both anxiety disorders and depression (Farzaneh et al., 2014). Various traits, such as nervousness, depression, low tolerance for disappointment, and the feeling of being held back increase the likelihood of having GAD (Bienvenu & Brandes, 2005). For instance, the results of studies show that neuroticism is an important and fundamental factor in anxiety, depression (Capello & Markus, 2014; Michikyan et al., 2014), and their comorbidity (Barnhofer & Chittka, 2010). ACcorindgly, the evaluation of personality function should be the central part of a comprehensive diagnostic process in patients with anxiety disorders (Gruber et al., 2020). This is clinically important because the response rate to treatment in these patients is low (Doering, 2018); for instance, this rate is 48% in GAD (Hunot, 2007).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the first psychotherapy option for GAD and its effectiveness is supported by several meta-analytic studies (Carpenter et al., 2018). Although CBT has demonstrated its effectiveness as the treatment of choice for GAD, the results of some studies show that only 50% of people with GAD achieve positive results from this method of treatment (Robichaud, 2013) while 50% of people have high symptoms and recurrence rate at the end of the treatment process (Rapgay et al., 2011) and fail to achieve the optimal results (Fresco et al., 2013). CBT is less effective in the improvement of people with GAD compared to other anxiety disorders (Hoyer et al., 2009). Research conducted in Iran also confirms this finding (Edrissi et al., 2015). On the other hand, the very high comorbidity of this disorder with other disorders, especially depression, has faced specific CBT with serious problems, at the economic, practical, and clinical levels. Specific CBT interventions are typically effective in treating 40% of such cases (Norton & Barrera, 2013) and the other 60% remain anxious, depressed, or demonstrate related diagnoses despite receiving a full course of evidence-based CBT. (Norton, 2017). Therefore, the use of specific cognitive-behavioral protocols is not cost-effective, considering the challenges arising from the problem of comorbidity from various dimensions (Akbari et al., 2014).

Since CBT is a flexible approach and subject to scientific data in the field of psychotherapy, it has always started to change and adapt when faced with defects and limitations. The transdiagnostic approach in the field of CBT has been the pioneer solution (Clark & Taylor, 2009; Dozois et al., 2009). Among the transdiagnostic approaches, the transdiagnostic treatment designed by Barlow (2011) is one of the interventions that has recently been used in the field of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders to solve the problems caused by specific treatments for comorbid problems. Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment is an emotion-focused CBT that can be used for a wide range of emotional disorders by using emotion regulation skills (Farchione et al., 2012).

Recent meta-analytic studies have shown the effectiveness of transdiagnostic CBT among patients with anxiety and depression disorders with moderate to large effect sizes (Osma et al., 2021; Dalgleish et al., 2020; Sakiris, Berle, 2019; Pearl & Norton, 2017; Anderson et al., 2016). Also, research results indicate the effectiveness of Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment (2011) in treating GAD comorbid with emotional disorders (Ghaderi et al., 2021; Riccardi et al., 2017; Dear et al., 2015; Norton and Brara, 2013). When Barlow’s integrated transdiagnostic protocol was compared with disorder-specific protocols for the treatment of GAD, it was found that transdiagnostic treatment was effective as specific treatments for this disorder and those with GAD were less likely to drop out of treatment, compared to specific treatments (Barlow et al., 2017; Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). In addition, the higher effectiveness of Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment compared to standard CBT for GAD has been shown in some studies (Newby et al., 2017). Accordingly, the present study aims to investigate the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on maladaptive personality traits and mentalized affectivity of people with GAD comorbid with depression.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a single-case quasi-experimental study. The study population consists of all people with GAD comorbid with depression who were referred to counseling centers in Isfahan City, Iran in 2019-2020. From this population, 5 subjects were selected using the purposive sampling method.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: a) having a minimum of middle school education and being in the age range of 20 to 55 years; b) being diagnosed with GAD based on a diagnostic interview and generalized anxiety questionnaire; c) having sub-symptoms of depression based on a diagnostic interview and the Beck depression inventory; d) not having a psychiatric diagnosis other than GAD and depression; d) not receiving any intervention or medication other than the research interventions; e) participation in treatment sessions and completing questionnaires.

The exclusion criterion was absence from more than 2 treatment sessions. Table 1 shows the clinical history of the research subjects.

.jpg)

Subsequently, the questionnaires were distributed among the participants at the baseline. Then, the interventions were performed individually. The transdiagnostic treatment was based on the Barlow protocol presented weekly in 1-h sessions. The subjects were re-evaluated at the third, fourth, eighth, and tenth session (end of treatment), and 1 month after the treatment using PID-5-BF and mentalized affectivity scale (MAS).

The mentalized affectivity scale

MAS is a new tool that measures the emotional domain and is developed by Greenberg et al. in 2017. This scale includes 60 questions and 3 subscales: identifying, processing, and expressing emotions. The creators of this scale reported high reliability and validity and suggest that it can be used for clinical and non-clinical populations and in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and neuroscience. The Persian version of this questionnaire has been standardized in Iran by Sayarfard et al. (2021). The Cronbach α coefficient for the whole scale was obtained at 0.93. The composite reliability of the factors was in the range of 0.82 to 0.89, and the coefficient θ of the scale was reported at 0.98.

The personality inventory for DSM-5 brief form

The short form of the adult version of the personality questionnaire is developed by Krueger et al. (2012) and includes 25 items regarding self-assessment for measuring abnormal personality traits in subjects with 18 years of age or higher (Krueger et al., 2012). The scale measures 5 personality traits, including negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism. Items are rated based on a 4-point Likert scale (0= very false or often false to 3=very true or often true). High scores in each subscale indicate the significant areas and the source of harm in the individual. Krueger et al. (2012) examined its psychometric properties in the sample of the general population and patients and reported the internal consistency of its scales ranging from moderate to high (0.73 to 0.95) with a mean of 0.86. Abdi and Chalabianlou (2017) reported the reliability of this questionnaire via the Cronbach α internal consistency method in the range of 0.83 to 0.89 and the retest coefficient of 0.77 to 0.87 for the subscales.

Program description

To report the data and evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, visual analysis or graphic diagram analysis methods, reliable change index, clinical significance, improvement percentage, and the effect size were used. The reliable change index was used to evaluate the statistical significance. In this index, the post-test score is subtracted from the pre-test score and the result are divided by the standard error of the difference between the two scores. For the reliable change index to be statistically significant, the absolute value of the result must be equal to or greater than 1.96, which indicates that the results are more because of active factors and manipulation of the experimenter than measurement error. The percentage of recovery formula was used to objectify the rate of improvement in therapeutic targets as well as clinical significance. In this formula, the pre-test score is subtracted from the post-test score and the result is divided by the pre-test score. Then, the result is multiplied by 100 (Hamidpour et al., 2011).

3. Results

Table 2 shows the structure and content of transdiagnostic treatment.

.jpg)

Scores of repeated measures of maladaptive personality traits of research subjects during baseline, intervention, and follow-up sessions and improvement percentage indices are provided in Table 3.

.jpg)

According to the results and based on the values of the reliable change index (RCI≥1.96), the transdiagnostic treatment intervention for the negative affectivity component was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up stages. In addition, the percentage of improvement after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 was equal to 38%, 46%, 37%, 35%, and 40%, respectively. The overall improvement percentage for the subjects is also 39.2%. In the follow-up stage, This rate reached 38%, 30%, 43%, 40%, and 33%, respectively, with a total improvement percentage of 36.8% for the subjects.

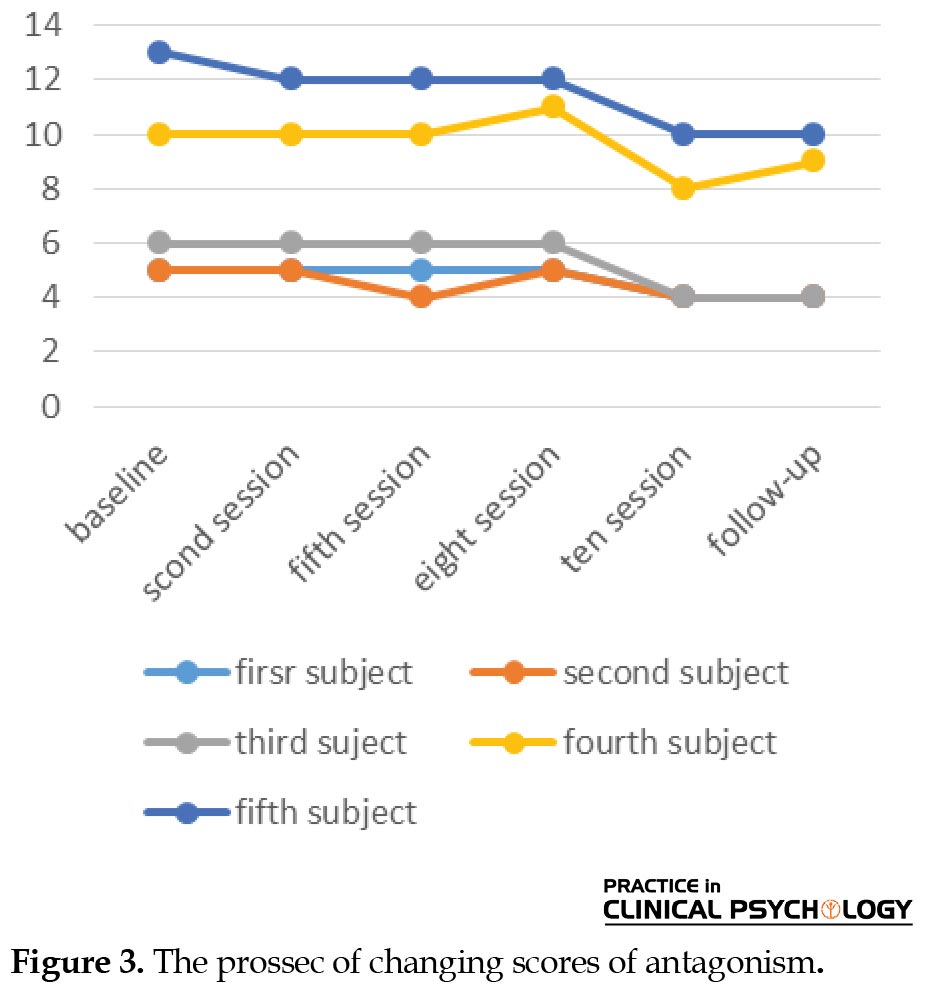

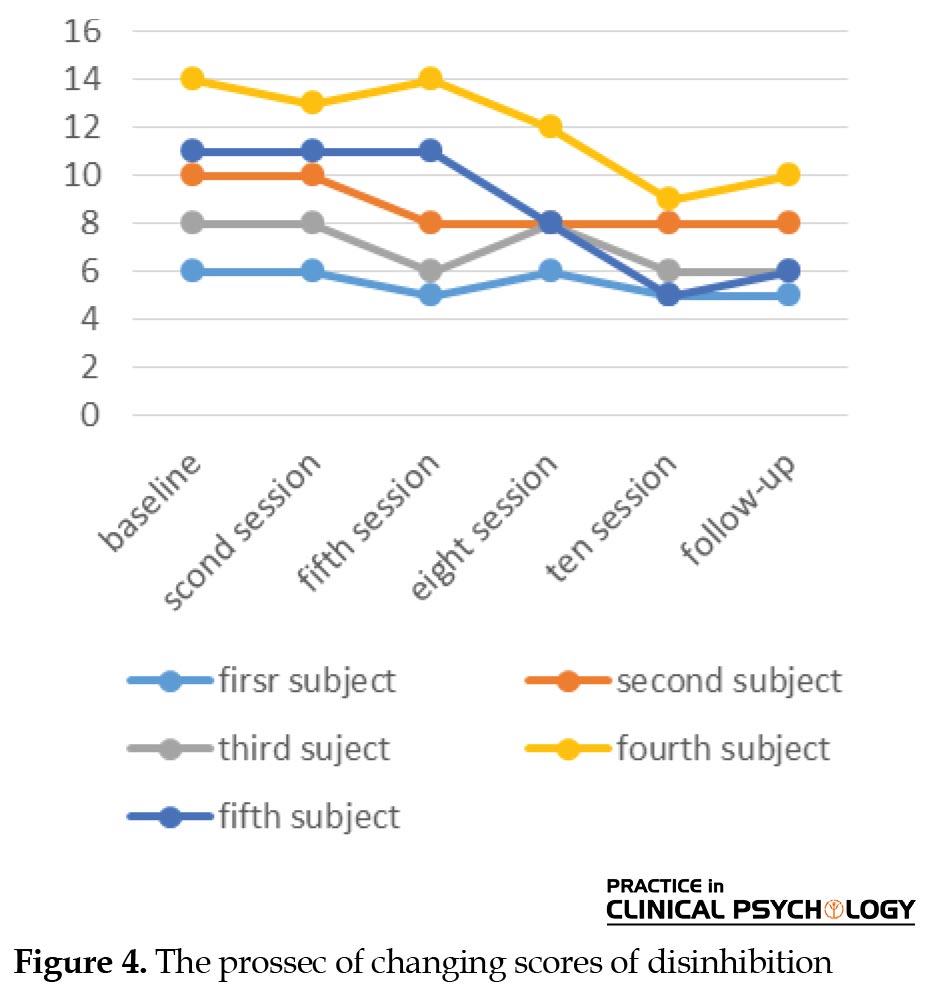

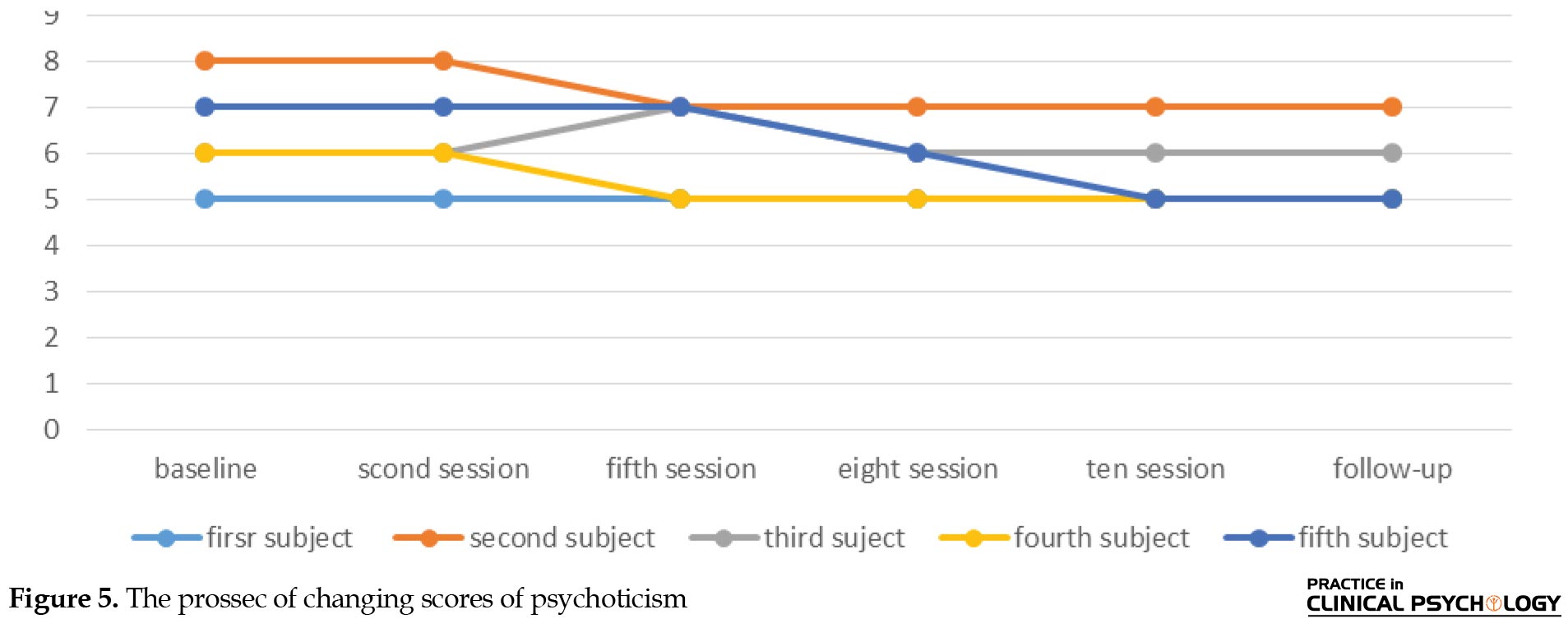

In the detachment component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was statistically significant for subjects 3, 4, and 5 in the intervention phase and all 5 subjects in the follow-up phase (RCI≥1.96). According to the results, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was significant for subjects 4 and 5 in the intervention stage (RCI≥1.96), while it was not significant for the other subjects (RCI≤1.96). In the follow-up phase, the intervention was statistically significant only for subject 5. In the antagonism component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was significant for subjects 4 and 5 in the intervention stage (RCI≥1.96) and not significant for other subjects (RCI≤1.96). In the follow-up phase, the intervention was statistically significant only for the fifth subject. In the component of disinhibition and psychoticism, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was not statistically and clinically significant for any of the subjects in the intervention and follow-up phase (RCI≤1.96). The graphs below show the change in scores of maladaptive personality traits in different stages of treatment.

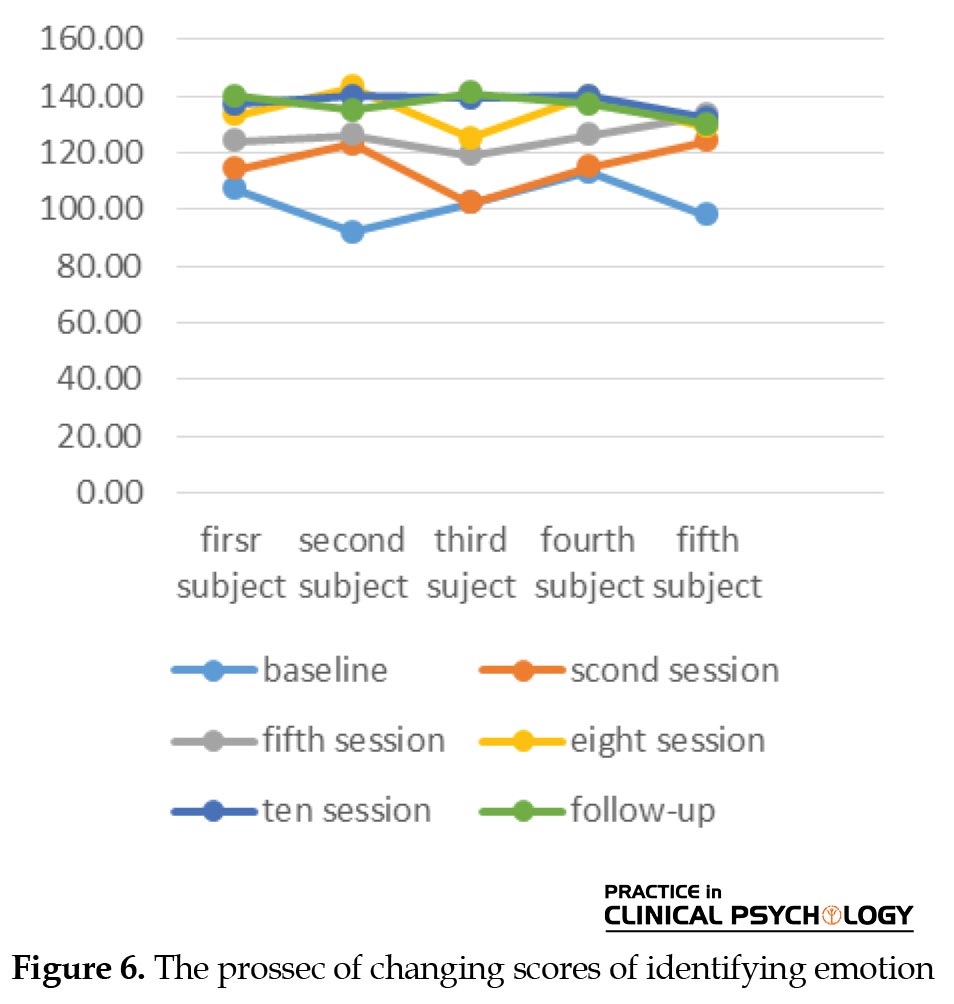

According to the results, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment for the component of identifying emotion for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up phases was statistically significant (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of improvement after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 were equal to 28%, 52%, 36%, 23%, and 40%, respectively, in the post-treatment phase and 30%, 46%, 38%, 21%, and 22%, respectively, in the follow-up phase. The overall improvement percentage for the subjects was 35% in the post-treatment phase, which reached up to 33% in the follow-up phase. In addition, because of the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention for the second subject was also clinically significant.

Regarding the processing emotions component, the transdiagnostic treatment intervention was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up phase (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of changes after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 in the processing emotion component was equal to 17%, 50%, 47%, 32%, and 40% respectively, with an overall improvement percentage of 37%. In the follow-up phase, this rate was 11%, 46%, 39%, 39%, and 44%, respectively, for the subjects, with an overall improvement percentage of 35%. Also, because of the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention for the second subject was clinically significant (Table 4).

.jpg)

In terms of the expressing emotions component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up stages (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of changes after the treatment for subjects 1 to 5 in the expressing emotions component was equal to 28%, 57%, 51%, 38%, and 50%, respectively, with an overall improvement percentage of 44%. In the follow-up phase, these rates were 24%, 5%, 46%, 27%, and 45%, respectively for the subjects, with an overall improvement percentage of 39%. Also, considering the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention in the expressing emotions component was clinically significant for the second, third, and fifth subjects. The Figures 1-8 show the trend of changes in the scores of subjective mentalized affectivity dimensions.

People with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are constantly worried about the possible occurrence of a wide range of negative events (APA, 2020). They expect unfortunate events to occur and become irritable while experiencing a lot of muscle contractions and may have trouble sleeping and concentrating. Their psychosocial function is likely to be severely impaired as well (Koenigsberg, 2021). GAD is associated with increased disability, cognitive impairment, life dissatisfaction, and low productivity in patients (Bower et al., 2016). The mean 12-month prevalence for the disorder is 1.3% worldwide, with a range of 0.2% to 4.3% (APA, 2022). A recent study in Iran reported a 2.6% lifetime prevalence of GAD (Mohammadiet al., 2020).

A total of 90% of people with GAD experience at least one form of psychological disorder (Blanco et al., 2014). This disorder has high comorbidity with other anxiety disorders and depression (Sadock et al., 2015; Shihata et al., 2017). Leahy et al. (2011) reported a 42% comorbidity rate of GAD and depression. Recent meta-analytic findings regarding the comorbidity between anxiety disorders and depression show that regardless of changes in the type of diagnosis, study timeframe, and chronological order of occurrence, mood disorders, and anxiety are strongly comorbid (Saha et al., 2021). Comorbidity reduces the accurate diagnosis, thereby reducing the effectiveness of treatment methods. It also increases treatment costs (Sharpley et al., 2010). As a result, therapists should pay attention to the quick identification and treatment of this common type of comorbid disorder (Saha et al., 2021). Regardless that which of the two disorders occurs first, the risk of subsequently developing the other disorder increases (Saha et al., 2021). This reciprocal relationship in comorbid disorders shows that these disorders may be due to common risk factors (Levey et al., 2020; Purves et al., 2020, Saha et al., 2021).

Emotion regulation has been suggested as a common factor in the psychopathology of GAD comorbid with depression (Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). Emotion regulation is a wide-ranging term that describes explicit and implicit processes which involve monitoring, evaluating, altering, and modulating emotions. The process of emotion regulation involves being aware, understanding, and identifying one’s thoughts and feelings (i.e.mentalization), before, during, and after refining and modulating the emotion (Greenberg et al., 2017). People with GAD experience intense emotions, tend to catastrophize, may not be able to correctly recognize and understand their emotions, and have problems suppressing their negative emotions (Mennin & Fresco, 2010; Tryon, 2014).

Jurist (2018) proposed a novel perspective on emotion regulation, called the theory of mentalized affectivity, which considers mentalization in the regulatory process. This theory argues that effectively regulating (managing, altering, or changing) an emotion relies on the capacity for mentalization. It argues that emotions are not just adjusted in a regulatory process, but they are also revalued in meaning. This more sophisticated aspect of emotion regulation requires the ability to reflect on one’s thoughts and feelings and to mentalize the factors that may influence the emotion, such as childhood experiences or the present situation, or the context in which a person is. This in turn helps to inform a person’s understanding of their emotions and how to anticipate future situations. Mentalized affectivity, as one of the new models and new assessment of emotion regulation, divides emotional regulation into 3 components: identifying emotions (the ability to identify emotions and to reflect on the factors that influence them); processing emotions (the ability to modulate and distinguish complex emotions); and expressing emotions (the tendency to express emotions outwardly or inwardly) (Greenberg et al., 2017). According to the mental affectivity model, emotional regulation is influenced by personality style, values, culture, personal history, and most importantly, mentalities (Jurist, 2018). According to the research results of Greenberg et al. (2017), individuals with anxiety, mood, and personality disorders show a profile of high identifying and low processing when compared to the control group.

Also, personality structures, such as neuroticism, negative affectivity, behavioral inhibition, positive affect, and extroversion are inherited traits that have a significant relationship with anxiety and related disorders. Maladaptive personality traits, especially neuroticism and negative affectivity are risk factors for divorce, unemployment, and disability-related retirement. They are influential in the prevalence, course, and occurrence of mental disorders. They cause functional impairment, act as an obstacle to improving symptoms and improvement in common mental disorders, and cause resistance to treatment, lack of response to treatment, and poor treatment outcomes (Hergatner, 2015). The clinical importance of the relationship between anxiety disorders and personality disorders can be assessed through its effects on the severity of anxiety disorders, the risk of suicide, and the process of anxiety disorders, as well as treatment outcomes (Latas & Milovanovic, 2014). Studies have shown that the lowest level of personality functioning among anxiety patients is related to patients with GAD (Doering, 2018). A significant part of the factor structure of the diagnostic classification of mental disorders is negative affectivity. This factor overlaps considerably with the main components of GAD. High levels of negative affectivity and low levels of positive affectivity are the basis for both anxiety disorders and depression (Farzaneh et al., 2014). Various traits, such as nervousness, depression, low tolerance for disappointment, and the feeling of being held back increase the likelihood of having GAD (Bienvenu & Brandes, 2005). For instance, the results of studies show that neuroticism is an important and fundamental factor in anxiety, depression (Capello & Markus, 2014; Michikyan et al., 2014), and their comorbidity (Barnhofer & Chittka, 2010). ACcorindgly, the evaluation of personality function should be the central part of a comprehensive diagnostic process in patients with anxiety disorders (Gruber et al., 2020). This is clinically important because the response rate to treatment in these patients is low (Doering, 2018); for instance, this rate is 48% in GAD (Hunot, 2007).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the first psychotherapy option for GAD and its effectiveness is supported by several meta-analytic studies (Carpenter et al., 2018). Although CBT has demonstrated its effectiveness as the treatment of choice for GAD, the results of some studies show that only 50% of people with GAD achieve positive results from this method of treatment (Robichaud, 2013) while 50% of people have high symptoms and recurrence rate at the end of the treatment process (Rapgay et al., 2011) and fail to achieve the optimal results (Fresco et al., 2013). CBT is less effective in the improvement of people with GAD compared to other anxiety disorders (Hoyer et al., 2009). Research conducted in Iran also confirms this finding (Edrissi et al., 2015). On the other hand, the very high comorbidity of this disorder with other disorders, especially depression, has faced specific CBT with serious problems, at the economic, practical, and clinical levels. Specific CBT interventions are typically effective in treating 40% of such cases (Norton & Barrera, 2013) and the other 60% remain anxious, depressed, or demonstrate related diagnoses despite receiving a full course of evidence-based CBT. (Norton, 2017). Therefore, the use of specific cognitive-behavioral protocols is not cost-effective, considering the challenges arising from the problem of comorbidity from various dimensions (Akbari et al., 2014).

Since CBT is a flexible approach and subject to scientific data in the field of psychotherapy, it has always started to change and adapt when faced with defects and limitations. The transdiagnostic approach in the field of CBT has been the pioneer solution (Clark & Taylor, 2009; Dozois et al., 2009). Among the transdiagnostic approaches, the transdiagnostic treatment designed by Barlow (2011) is one of the interventions that has recently been used in the field of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders to solve the problems caused by specific treatments for comorbid problems. Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment is an emotion-focused CBT that can be used for a wide range of emotional disorders by using emotion regulation skills (Farchione et al., 2012).

Recent meta-analytic studies have shown the effectiveness of transdiagnostic CBT among patients with anxiety and depression disorders with moderate to large effect sizes (Osma et al., 2021; Dalgleish et al., 2020; Sakiris, Berle, 2019; Pearl & Norton, 2017; Anderson et al., 2016). Also, research results indicate the effectiveness of Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment (2011) in treating GAD comorbid with emotional disorders (Ghaderi et al., 2021; Riccardi et al., 2017; Dear et al., 2015; Norton and Brara, 2013). When Barlow’s integrated transdiagnostic protocol was compared with disorder-specific protocols for the treatment of GAD, it was found that transdiagnostic treatment was effective as specific treatments for this disorder and those with GAD were less likely to drop out of treatment, compared to specific treatments (Barlow et al., 2017; Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). In addition, the higher effectiveness of Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment compared to standard CBT for GAD has been shown in some studies (Newby et al., 2017). Accordingly, the present study aims to investigate the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on maladaptive personality traits and mentalized affectivity of people with GAD comorbid with depression.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a single-case quasi-experimental study. The study population consists of all people with GAD comorbid with depression who were referred to counseling centers in Isfahan City, Iran in 2019-2020. From this population, 5 subjects were selected using the purposive sampling method.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: a) having a minimum of middle school education and being in the age range of 20 to 55 years; b) being diagnosed with GAD based on a diagnostic interview and generalized anxiety questionnaire; c) having sub-symptoms of depression based on a diagnostic interview and the Beck depression inventory; d) not having a psychiatric diagnosis other than GAD and depression; d) not receiving any intervention or medication other than the research interventions; e) participation in treatment sessions and completing questionnaires.

The exclusion criterion was absence from more than 2 treatment sessions. Table 1 shows the clinical history of the research subjects.

.jpg)

Subsequently, the questionnaires were distributed among the participants at the baseline. Then, the interventions were performed individually. The transdiagnostic treatment was based on the Barlow protocol presented weekly in 1-h sessions. The subjects were re-evaluated at the third, fourth, eighth, and tenth session (end of treatment), and 1 month after the treatment using PID-5-BF and mentalized affectivity scale (MAS).

The mentalized affectivity scale

MAS is a new tool that measures the emotional domain and is developed by Greenberg et al. in 2017. This scale includes 60 questions and 3 subscales: identifying, processing, and expressing emotions. The creators of this scale reported high reliability and validity and suggest that it can be used for clinical and non-clinical populations and in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and neuroscience. The Persian version of this questionnaire has been standardized in Iran by Sayarfard et al. (2021). The Cronbach α coefficient for the whole scale was obtained at 0.93. The composite reliability of the factors was in the range of 0.82 to 0.89, and the coefficient θ of the scale was reported at 0.98.

The personality inventory for DSM-5 brief form

The short form of the adult version of the personality questionnaire is developed by Krueger et al. (2012) and includes 25 items regarding self-assessment for measuring abnormal personality traits in subjects with 18 years of age or higher (Krueger et al., 2012). The scale measures 5 personality traits, including negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism. Items are rated based on a 4-point Likert scale (0= very false or often false to 3=very true or often true). High scores in each subscale indicate the significant areas and the source of harm in the individual. Krueger et al. (2012) examined its psychometric properties in the sample of the general population and patients and reported the internal consistency of its scales ranging from moderate to high (0.73 to 0.95) with a mean of 0.86. Abdi and Chalabianlou (2017) reported the reliability of this questionnaire via the Cronbach α internal consistency method in the range of 0.83 to 0.89 and the retest coefficient of 0.77 to 0.87 for the subscales.

Program description

To report the data and evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, visual analysis or graphic diagram analysis methods, reliable change index, clinical significance, improvement percentage, and the effect size were used. The reliable change index was used to evaluate the statistical significance. In this index, the post-test score is subtracted from the pre-test score and the result are divided by the standard error of the difference between the two scores. For the reliable change index to be statistically significant, the absolute value of the result must be equal to or greater than 1.96, which indicates that the results are more because of active factors and manipulation of the experimenter than measurement error. The percentage of recovery formula was used to objectify the rate of improvement in therapeutic targets as well as clinical significance. In this formula, the pre-test score is subtracted from the post-test score and the result is divided by the pre-test score. Then, the result is multiplied by 100 (Hamidpour et al., 2011).

3. Results

Table 2 shows the structure and content of transdiagnostic treatment.

.jpg)

Scores of repeated measures of maladaptive personality traits of research subjects during baseline, intervention, and follow-up sessions and improvement percentage indices are provided in Table 3.

.jpg)

According to the results and based on the values of the reliable change index (RCI≥1.96), the transdiagnostic treatment intervention for the negative affectivity component was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up stages. In addition, the percentage of improvement after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 was equal to 38%, 46%, 37%, 35%, and 40%, respectively. The overall improvement percentage for the subjects is also 39.2%. In the follow-up stage, This rate reached 38%, 30%, 43%, 40%, and 33%, respectively, with a total improvement percentage of 36.8% for the subjects.

In the detachment component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was statistically significant for subjects 3, 4, and 5 in the intervention phase and all 5 subjects in the follow-up phase (RCI≥1.96). According to the results, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was significant for subjects 4 and 5 in the intervention stage (RCI≥1.96), while it was not significant for the other subjects (RCI≤1.96). In the follow-up phase, the intervention was statistically significant only for subject 5. In the antagonism component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was significant for subjects 4 and 5 in the intervention stage (RCI≥1.96) and not significant for other subjects (RCI≤1.96). In the follow-up phase, the intervention was statistically significant only for the fifth subject. In the component of disinhibition and psychoticism, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was not statistically and clinically significant for any of the subjects in the intervention and follow-up phase (RCI≤1.96). The graphs below show the change in scores of maladaptive personality traits in different stages of treatment.

According to the results, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment for the component of identifying emotion for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up phases was statistically significant (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of improvement after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 were equal to 28%, 52%, 36%, 23%, and 40%, respectively, in the post-treatment phase and 30%, 46%, 38%, 21%, and 22%, respectively, in the follow-up phase. The overall improvement percentage for the subjects was 35% in the post-treatment phase, which reached up to 33% in the follow-up phase. In addition, because of the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention for the second subject was also clinically significant.

Regarding the processing emotions component, the transdiagnostic treatment intervention was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up phase (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of changes after treatment for subjects 1 to 5 in the processing emotion component was equal to 17%, 50%, 47%, 32%, and 40% respectively, with an overall improvement percentage of 37%. In the follow-up phase, this rate was 11%, 46%, 39%, 39%, and 44%, respectively, for the subjects, with an overall improvement percentage of 35%. Also, because of the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention for the second subject was clinically significant (Table 4).

.jpg)

In terms of the expressing emotions component, the intervention of transdiagnostic treatment was statistically significant for all 5 subjects in the intervention and follow-up stages (RCI≥1.96). The percentage of changes after the treatment for subjects 1 to 5 in the expressing emotions component was equal to 28%, 57%, 51%, 38%, and 50%, respectively, with an overall improvement percentage of 44%. In the follow-up phase, these rates were 24%, 5%, 46%, 27%, and 45%, respectively for the subjects, with an overall improvement percentage of 39%. Also, considering the improvement percentage of over 50%, the intervention in the expressing emotions component was clinically significant for the second, third, and fifth subjects. The Figures 1-8 show the trend of changes in the scores of subjective mentalized affectivity dimensions.

Discussion

The results showed that transdiagnostic treatment is effective in all three dimensions of mentalized affectivity (identifying, processing, and expressing emotion), negative affectivity, and detachment. These findings are indirectly consistent with the results of the studies by Ellard et al. (2010), Farchione et al. (2012), and Corpas et al. (2022). They have shown the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment in reducing the symptoms of GAD.

The findings of the present study showed that transdiagnostic therapy is effective in modulating identifying, processing, and expressing emotion components. One of the possible causes and explanations of the effect of transdiagnostic treatment on psychological variables in the present study is the attention of the transdiagnostic approach to the basic and common factors underlying emotional disorders. According to Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment, mental disorders are more similar than different, and their main commonality is the negative response or reaction of people to intense and disturbing emotional experiences (Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). This protocol focuses on emotion and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and targets the common causative mechanisms of emotional disorders. In addition, treatment with Barlow’s transdiagnostic protocol emphasizes the adaptive and functional nature of emotions, increasing the patient’s awareness of the role of cognitions and emotions, physical sensations, and behaviors (Farchione et al., 2012).

Being aware of emotions, facing emotions, accepting emotions, and not suppressing them are among the effective strategies in emotion regulation that are frequently used in the transdiagnostic approach. One of the important parts of transdiagnostic treatment is understanding the adaptive nature of emotions and increasing emotional awareness. Therapy sessions teach clients that all emotions, both positive and negative, are important and necessary and the goal is not to eliminate but to identify, tolerate, and cope with negative emotions (Barlow, 2011). As a result of this awareness and the mentioned emotional skills training, the improvement of the emotional skills of clients is not far from expected.

Considering the change in mentalized affectivity scores as well as patients’ negative affectivity as a result of providing transdiagnostic intervention, this factor is always one of the main goals of transdiagnostic treatment. Barlow’s transdiagnostic protocol aims to achieve improvement with some techniques and skills and efforts to reduce the severity of this factor by modulating the intensity of the patient’s negative reaction to negative emotions. The reduction of negative emotion scores as one of the central and transdiagnostic factors is not because of the direct targeting of these emotions; however, this treatment method, in addition to acknowledging negative emotional experiences and not seeing the need to reduce them, values them. It is adaptive and functional and emphasizes reducing emotional reactions to these negative emotions rather than reducing negative emotions. Accordingly, the changes in negative emotions are mostly because of the reduction of avoidance and negative reaction to these emotions, not intending to reduce or increase the emotions. This method helps the patient to reduce the intensity and occurrence of negative emotional habits, reduce the amount of damage, and increase individual and interpersonal functions by adjusting emotional regulation habits (Abdi, Bakhshi & Mahmoud., 2013).

Psychoeducational strategies, self-control of thoughts, exposure, prevention, and response management have shown good results in previous studies and are part of the techniques used in the treatment. These techniques facilitate the identification of thoughts that influence emotions and behaviors that cause anxiety and depression. Such knowledge gives patients the necessary security to face the situations and decisions needed in life (Post, 2014). Improving emotional regulation and management skills and the strategies that people use to regulate their emotions can improve their health in various biological, psychological, social, and moral dimensions. As a result, by improving emotional regulation skills as a basic and central factor in personality, people experience fewer personality and interpersonal problems and thus have a higher quality of life. Also, knowing the nature of thoughts and emotions and identifying and practicing the right ways to manage these dimensions will help to adjust the maladaptive personality traits in people. Transdiagnostic treatments have several advantages. A transdiagnostic approach may reduce the length and overall cost of treatment, increase clinical capability and simplify clinical training, shorten the gap between research and practice, facilitate the dissemination of evidence-based treatments, and help therapists broaden their perspectives (Barlow et al., 2016; Leichsenring & Steinert, 2018). Transdiagnostic treatments may also offer benefits beyond efficacy. Their increasing popularity reflects the general need for clarity, simplicity, and an emphasis on commonality (Schaeuffele et al., 2021).

Study limitations

The generalizability of the present findings is limited by considering the limitations of single-case designs, such as the small sample size. Given the limitations, further research is needed to confirm the efficacy and applicability of these intervention methods in people with GAD comorbid with depression in the form of randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes.

5.Conclusion

Considering the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on mentalized affectivity, dimensions of negative affect, and detachment, transdiagnostic treatment can be used by therapists, according to the conditions and needs of patients, along with other treatment models for people with GAD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was apprived by Department of Psychology, University of Isfahan (Code: REC.1398.013), and was registered with the following code in the Iranian clinical trial site: IRCT20200918048749N1. Ethical principles included full awareness of the participants about the research process and the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was taken from Farzad Ghaderi’s PhD dissertation at the Department of Psychology, University of Isfahan.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who contributed to this research.

References

Abdi, R., Bakhshi, A., & Mahmoud, A. M. (2013). [Efficacy of unified transdiagnostic treatment on reduction of transdiagnostic factors and symptoms severity in emotional disorders. (Persian)]. Psychological Methods and Models, 4(13), 1-27. [Link]

Abdi, R., Chalabianlou, G. (2017). [Adaptation and psychometric characteristic of personality inventory for DSM-5-Brief form (PID-5-BF) (Persian)]. Journal of Modern Psychological Researches, 12(45), 131-154. [Link]

Akbari, M., Roshan, R., Shabani, A., Fata, L., Shairi, M. R., & Zarghami, F. (2015). [The comparison of the efficacy of transdiagnostic therapy based on repetitive negative thoughts with unified transdiagnostic therapy in treatment of patients with co-occurrence anxiety and depressive disorders: A randomized clinical trial (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 21(2), 88-107. [Link]

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787]

Anderson, J. L., Sellbom, M., & Salekin, R. T. (2016). Utility of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5-Brief Form (PID-5BF) in the measurement of maladaptive personality and psychopathology. Assessment, 25(5), 596–607. [DOI:10.1177/1073191116676889] [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Allen, L. B., & Choate, M. L. (2016). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders- republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 838-853. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005] [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Farchione, T. J., Boisseau, C. L., & Allen, L. B., et al. (2011). Unifed protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Workbook. Oxford: Oxford Academic Press. [DOI:10.1093/med:psych/9780199772674.001.0001]

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Bullis, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., Murray-Latin, H., & Sauer-Zavala, S., et al. (2017). The unifed protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specifc protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875-884. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164] [PMID] [PMCID]

Barnhofer, T., & Chittka, T. (2010). Cognitive reactivity mediates the relationship between neuroticism and depression. Behavior Research and Therapy, 48(4), 275-281. [PMID] [PMCID]

Bienvenu O. J., & Brandes, M. (2005). The interface of personality traits and anxiety disorders. Primary Psychiatry, 12(3), 35–39. [Link]

Blanco, C., Rubio, J. M., Wall, M., Secades-Villa, R., Beesdo-Baum, K., & Wang, S. (2014). The latent structure and comorbidity patterns of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder: A national study. Depression and Anxiety, 31(3), 214-222. [DOI:10.1002/da.22139] [PMID] [PMCID]

Bower, E., Wetherell, J. L., Mon, T., & Lenze, E. J. (2015). Treating anxiety disorders in older adults: Current treatments and future directions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(5), 329-342. [DOI:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000064] [PMID]

Capello, A. E., & Markus, C. R. (2014). Differential influence of the 5-HTTLPR genotype, neuroticism and real-life acute stress exposure on appetite and energy intake. Appetite, 77, 83-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.002] [PMID]

Carpenter, J. K., Andrews, L. A., Witcraft, S. M., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 35(6), 502-514. [PMID] [PMCID]

Clark D. A., & Taylor, S. (2009). The transdiagnostic perspective on cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: New wine for old wineskins? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(1), 60-66. [DOI:10.1891/0889-8391.23.1.60]

Corpas, J., Moriana, J. A., Venceslá, J. F., & Gálvez-Lara, M. (2022). Effectiveness of brief group transdiagnostic therapy for emotional disorders in primary care: A randomized controlled trial identifying predictors of outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 32(4), 456-469. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2021.1952331] [PMID]

Dalgleish, T., Black, M., Johnston, D., & Bevan, A. (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 179–195. [PMID] [PMCID]

Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Karin, E., Zou, J., & Johnston, L., et al. (2015). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 36, 63-77. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.003] [PMID]

Doering, S., Blüml, V., Parth, K., Feichtinger, K., Gruber, M., & Aigner, M., et al. (2018). Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 294. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1870-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dozois, D. A., Seeds, P. M., & Collins, K. A. (2009). Transdiagnostic approaches to the prevention of depression and anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(1), 44-59. [DOI:10.1891/0889-8391.23.1.44]

Edrissi, F., khanzadeh, M., Bahrainian, A. (2015). [Structural model of emotional regulation and symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in students (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 5(20), 203-226. [Link]

Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Boisseau, C. L., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2010). Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(1), 88-101. [PMID] [PMCID]

Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Thompson- Hollands, J., & Carl, J. R., et al. (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 666-678. [PMID] [PMCID]

Farzaneh, H., Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., Zargar, Y., & Davodi, I. (2015). [The effectiveness of transdiagnostic therapy on anxiety, depression, cognitive strategies of emotional regulation, and general performance in women with comorbid anxiety and depression (Persian). Journal of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, 5(4), 551-563. [Link]

Fresco, D. M., Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., & Ritter, M. (2013). Emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 282-300. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.02.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ghaderi, F., Akrami, N., Namdari, K., & Abedi, A. (2022). [Comparing the effects of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy and transdiagnostic treatment on symptoms of patients with generalized anxiety disorder comorbid with depression (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 27(4), 440-457. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.4.3067.3]

Greenberg, D. M., Kolasi, J., Hegsted, C. P., Berkowitz, Y., & Jurist, E. L. (2017). Mentalized affectivity: A new model and assessment of emotion regulation. PloS One, 12(10), e0185264. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0185264] [PMID] [PMCID]

Gruber, M., Doering, S., & Blüml, V. (2020). Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(1), 62-69. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000556] [PMID]

Hamidpour, H., Dolatshai, B., Pour Shahbaz, A., & Dadkhah, A. (2011). The efficacy of schema therapy in treating women’s generalized anxiety disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 16 (4), 420-431. [Link]

Hengartner, M. P. (2015). The detrimental impact of maladaptive personality on public mental health: A challenge for psychiatric practice. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 87. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hoyer, J., Beesdo, K., Gloster, A. T., Runge, J., Höfler, M., & Becker, E. S. (2009). Worry exposure versus applied relaxation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(2), 106-115. [DOI:10.1159/000201936] [PMID]

Hunot, V., Churchill, R., Silva de Lima, M., & Teixeira, V. (2007). Psychological therapies for generalised anxiety disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2007(1), CD001848. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001848.pub4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jurist, E. (2018). Minding emotions: Cultivating mentalization in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Publications. [Link]

Kennedy, K. A., & Barlow, D. (2018). The unifed treatment for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: An introduction. In D. H. Barlow, & T. Farchione (Eds.), Applications of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders (pp.1-16). Oxford: Oxford Academic. [DOI:10.1093/med-psych/9780190255541.003.0001]

Koenigsberg, J. Z. (2021). Anxiety disorders: Integrated psychotherapy approaches. New York: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780429023637]

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and invento-ry for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1879-1890. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291711002674] [PMID] [PMCID]

Latas, M., & Milovanovic, S. (2014). Personality disorders and anxiety disorders: What is the relationship? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(1), 57-61. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000025] [PMID]

Leahy, R. L., Holland, S. J., & McGinn, L. K. (2011). Treatment plans and interventions for depression and anxiety disorders. New York: Guilford press. [Link]

Leichsenring, F., & Steinert, C. (2018). Towards an evidence-based unifed psychodynamic protocol for emotional disorders. Journal of Affective Disor-ders, 232, 400-416. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.036] [PMID]

Levey, D. F., Gelernter, J., Polimanti, R., Zhou, H., Cheng, Z., & Aslan, M., et al. (2020). Reproducible genetic risk loci for anxiety: Results from -200,000 participants in the Million Veteran Program. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(3), 223-232. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030256] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mennin, D. S., & Fresco, D. M. (2010). Emotion regulation as an integrative framework for understanding and treating psychopathology. In A. M. Kring & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 356-379). New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Dennis, J. (2014). Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 179-183. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.010]

Mohammadi, M. R., Pourdehghan, P., Mostafavi, S. A., Hooshyari, Z., Ahmadi, N., & Khaleghi, A. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, predictors, and comorbidity in children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102234. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102234] [PMID]

Newby, J. M., Mewton, L., & Andrews, G. (2017). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 25-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.002] [PMID]

Norton, P. J., & Barrera, T. L. (2012). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specefic CBT for anxiety disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled nonin-feriority trial. Depression and Anxiety, 29(10), 874-882. [DOI:10.1002/da.21974] [PMID] [PMCID]

Norton, P. (2017). Transdiagnostic approaches to the understanding and treatment of anxiety and related disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 1-3 [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.02.004] [PMID]

Osma, J., Martínez-García, L., Quilez-Orden, A., & Peris-Baquero, Ó. (2021). Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in medical conditions: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5077. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18105077] [PMID] [PMCID]

Pearl, S. B., & Norton, P. J. (2017). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis specific cognitive behavioural therapies for anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 11-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.004] [PMID]

Post, L. M. (2014). Emotion regulation processes and negative mood regulation expectations in the relationship between negative affect and co-occurring PTSD and MDD [PhD Dissertation]. Ohio: Case Western Reserve University. [Link]

Purves, K. L., Coleman, J. R. I., Meier, S. M., Rayner, C., Davis, K. A. S., & Cheesman, R., et al. (2020). A major role in common genetic variation in anxie-ty disorders. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(12), 3292-3303. [DOI:10.1038/s41380-019-0559-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

Rapgay, L., Bystritsky, A., Dafter, R. E., & Spearman, M. (2011). New strategies for combining mindfulness with integrative cognitive behavioral thera-py for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 29(2), 92-119. [DOI:10.1007/s10942-009-0095-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

Riccardi, C. J., Korte, K. J., & Schmidt, N. B. (2017). False safety behavior elimination therapy: A randomized study of a brief individual transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 35-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.003] [PMID]

Robichaud, M. (2013).Cognitive behavior therapy targeting intolerance of uncertainty: Application to a clinical case of generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 251-263. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.09.001]

Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., Ruiz, P. (2015). Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. New York: Wolter Kluwer. [Link]

Saha, S., Lim, C. C. W., Cannon, D. L., Burton, L., Bremner, M., & Cosgrove, P., et al. (2021). Co-morbidity between mood and anxiety disorders: A sys-tematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 38(3), 286-306. [DOI:10.1002/da.23113] [PMID] [PMCID]

Sakiris, N., & Berle, D. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the unified protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based interven-tion. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101751 [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101751] [PMID]

Sayarfard, Z., Azadfallah, P., & Farahani, H. (2021). [Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Persian version of Mentalized Affectivity Scale (Persian)]. Journal of Birjand University Medicl Sciences, 28(4), 385-401. [DOI:10.32592/JBirjandUnivMedSci.2021.28.4.107]

Schaeuffele, C., Schulz, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Renneberg, B., & Boettcher, J. (2021). CBT at the crossroads: The rise of transdiagnostic treatments. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 14, 86-113. [DOI:10.1007/s41811-020-00095-2]

Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., & Christie, D. R. H. (2010). Incidence and nature of anxiety-depression comorbidity in prostate cancer patients. Journal of Men’s Health, 7(2), 125-134. [DOI:10.1016/j.jomh.2010.03.003]

Shihata, S., McEvoy, P. M., & Mullan, B. A. (2017). Pathways from uncertainty to anxiety: An evaluation of a hierarchical model of trait and disorder-specific intolerance of uncertainty on anxiety disorder symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorder, 45, 72-79. [PMID]

Tryon, W. W. (2014). Cognitive neuroscience and psychotherapy: Network principles for a unifed theory. Cambridge: Cambridge Academic Press. [Link]

The results showed that transdiagnostic treatment is effective in all three dimensions of mentalized affectivity (identifying, processing, and expressing emotion), negative affectivity, and detachment. These findings are indirectly consistent with the results of the studies by Ellard et al. (2010), Farchione et al. (2012), and Corpas et al. (2022). They have shown the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment in reducing the symptoms of GAD.

The findings of the present study showed that transdiagnostic therapy is effective in modulating identifying, processing, and expressing emotion components. One of the possible causes and explanations of the effect of transdiagnostic treatment on psychological variables in the present study is the attention of the transdiagnostic approach to the basic and common factors underlying emotional disorders. According to Barlow’s transdiagnostic treatment, mental disorders are more similar than different, and their main commonality is the negative response or reaction of people to intense and disturbing emotional experiences (Kennedy & Barlow, 2018). This protocol focuses on emotion and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and targets the common causative mechanisms of emotional disorders. In addition, treatment with Barlow’s transdiagnostic protocol emphasizes the adaptive and functional nature of emotions, increasing the patient’s awareness of the role of cognitions and emotions, physical sensations, and behaviors (Farchione et al., 2012).

Being aware of emotions, facing emotions, accepting emotions, and not suppressing them are among the effective strategies in emotion regulation that are frequently used in the transdiagnostic approach. One of the important parts of transdiagnostic treatment is understanding the adaptive nature of emotions and increasing emotional awareness. Therapy sessions teach clients that all emotions, both positive and negative, are important and necessary and the goal is not to eliminate but to identify, tolerate, and cope with negative emotions (Barlow, 2011). As a result of this awareness and the mentioned emotional skills training, the improvement of the emotional skills of clients is not far from expected.

Considering the change in mentalized affectivity scores as well as patients’ negative affectivity as a result of providing transdiagnostic intervention, this factor is always one of the main goals of transdiagnostic treatment. Barlow’s transdiagnostic protocol aims to achieve improvement with some techniques and skills and efforts to reduce the severity of this factor by modulating the intensity of the patient’s negative reaction to negative emotions. The reduction of negative emotion scores as one of the central and transdiagnostic factors is not because of the direct targeting of these emotions; however, this treatment method, in addition to acknowledging negative emotional experiences and not seeing the need to reduce them, values them. It is adaptive and functional and emphasizes reducing emotional reactions to these negative emotions rather than reducing negative emotions. Accordingly, the changes in negative emotions are mostly because of the reduction of avoidance and negative reaction to these emotions, not intending to reduce or increase the emotions. This method helps the patient to reduce the intensity and occurrence of negative emotional habits, reduce the amount of damage, and increase individual and interpersonal functions by adjusting emotional regulation habits (Abdi, Bakhshi & Mahmoud., 2013).

Psychoeducational strategies, self-control of thoughts, exposure, prevention, and response management have shown good results in previous studies and are part of the techniques used in the treatment. These techniques facilitate the identification of thoughts that influence emotions and behaviors that cause anxiety and depression. Such knowledge gives patients the necessary security to face the situations and decisions needed in life (Post, 2014). Improving emotional regulation and management skills and the strategies that people use to regulate their emotions can improve their health in various biological, psychological, social, and moral dimensions. As a result, by improving emotional regulation skills as a basic and central factor in personality, people experience fewer personality and interpersonal problems and thus have a higher quality of life. Also, knowing the nature of thoughts and emotions and identifying and practicing the right ways to manage these dimensions will help to adjust the maladaptive personality traits in people. Transdiagnostic treatments have several advantages. A transdiagnostic approach may reduce the length and overall cost of treatment, increase clinical capability and simplify clinical training, shorten the gap between research and practice, facilitate the dissemination of evidence-based treatments, and help therapists broaden their perspectives (Barlow et al., 2016; Leichsenring & Steinert, 2018). Transdiagnostic treatments may also offer benefits beyond efficacy. Their increasing popularity reflects the general need for clarity, simplicity, and an emphasis on commonality (Schaeuffele et al., 2021).

Study limitations

The generalizability of the present findings is limited by considering the limitations of single-case designs, such as the small sample size. Given the limitations, further research is needed to confirm the efficacy and applicability of these intervention methods in people with GAD comorbid with depression in the form of randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes.

5.Conclusion

Considering the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on mentalized affectivity, dimensions of negative affect, and detachment, transdiagnostic treatment can be used by therapists, according to the conditions and needs of patients, along with other treatment models for people with GAD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was apprived by Department of Psychology, University of Isfahan (Code: REC.1398.013), and was registered with the following code in the Iranian clinical trial site: IRCT20200918048749N1. Ethical principles included full awareness of the participants about the research process and the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was taken from Farzad Ghaderi’s PhD dissertation at the Department of Psychology, University of Isfahan.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who contributed to this research.

References

Abdi, R., Bakhshi, A., & Mahmoud, A. M. (2013). [Efficacy of unified transdiagnostic treatment on reduction of transdiagnostic factors and symptoms severity in emotional disorders. (Persian)]. Psychological Methods and Models, 4(13), 1-27. [Link]

Abdi, R., Chalabianlou, G. (2017). [Adaptation and psychometric characteristic of personality inventory for DSM-5-Brief form (PID-5-BF) (Persian)]. Journal of Modern Psychological Researches, 12(45), 131-154. [Link]

Akbari, M., Roshan, R., Shabani, A., Fata, L., Shairi, M. R., & Zarghami, F. (2015). [The comparison of the efficacy of transdiagnostic therapy based on repetitive negative thoughts with unified transdiagnostic therapy in treatment of patients with co-occurrence anxiety and depressive disorders: A randomized clinical trial (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 21(2), 88-107. [Link]

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787]

Anderson, J. L., Sellbom, M., & Salekin, R. T. (2016). Utility of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5-Brief Form (PID-5BF) in the measurement of maladaptive personality and psychopathology. Assessment, 25(5), 596–607. [DOI:10.1177/1073191116676889] [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Allen, L. B., & Choate, M. L. (2016). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders- republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 838-853. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005] [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Farchione, T. J., Boisseau, C. L., & Allen, L. B., et al. (2011). Unifed protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Workbook. Oxford: Oxford Academic Press. [DOI:10.1093/med:psych/9780199772674.001.0001]

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Bullis, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., Murray-Latin, H., & Sauer-Zavala, S., et al. (2017). The unifed protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specifc protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875-884. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164] [PMID] [PMCID]

Barnhofer, T., & Chittka, T. (2010). Cognitive reactivity mediates the relationship between neuroticism and depression. Behavior Research and Therapy, 48(4), 275-281. [PMID] [PMCID]

Bienvenu O. J., & Brandes, M. (2005). The interface of personality traits and anxiety disorders. Primary Psychiatry, 12(3), 35–39. [Link]

Blanco, C., Rubio, J. M., Wall, M., Secades-Villa, R., Beesdo-Baum, K., & Wang, S. (2014). The latent structure and comorbidity patterns of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder: A national study. Depression and Anxiety, 31(3), 214-222. [DOI:10.1002/da.22139] [PMID] [PMCID]

Bower, E., Wetherell, J. L., Mon, T., & Lenze, E. J. (2015). Treating anxiety disorders in older adults: Current treatments and future directions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(5), 329-342. [DOI:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000064] [PMID]

Capello, A. E., & Markus, C. R. (2014). Differential influence of the 5-HTTLPR genotype, neuroticism and real-life acute stress exposure on appetite and energy intake. Appetite, 77, 83-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.002] [PMID]

Carpenter, J. K., Andrews, L. A., Witcraft, S. M., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 35(6), 502-514. [PMID] [PMCID]

Clark D. A., & Taylor, S. (2009). The transdiagnostic perspective on cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: New wine for old wineskins? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(1), 60-66. [DOI:10.1891/0889-8391.23.1.60]

Corpas, J., Moriana, J. A., Venceslá, J. F., & Gálvez-Lara, M. (2022). Effectiveness of brief group transdiagnostic therapy for emotional disorders in primary care: A randomized controlled trial identifying predictors of outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 32(4), 456-469. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2021.1952331] [PMID]

Dalgleish, T., Black, M., Johnston, D., & Bevan, A. (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 179–195. [PMID] [PMCID]

Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Karin, E., Zou, J., & Johnston, L., et al. (2015). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 36, 63-77. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.003] [PMID]

Doering, S., Blüml, V., Parth, K., Feichtinger, K., Gruber, M., & Aigner, M., et al. (2018). Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 294. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1870-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dozois, D. A., Seeds, P. M., & Collins, K. A. (2009). Transdiagnostic approaches to the prevention of depression and anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(1), 44-59. [DOI:10.1891/0889-8391.23.1.44]

Edrissi, F., khanzadeh, M., Bahrainian, A. (2015). [Structural model of emotional regulation and symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in students (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 5(20), 203-226. [Link]

Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Boisseau, C. L., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2010). Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(1), 88-101. [PMID] [PMCID]

Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Thompson- Hollands, J., & Carl, J. R., et al. (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 666-678. [PMID] [PMCID]

Farzaneh, H., Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., Zargar, Y., & Davodi, I. (2015). [The effectiveness of transdiagnostic therapy on anxiety, depression, cognitive strategies of emotional regulation, and general performance in women with comorbid anxiety and depression (Persian). Journal of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, 5(4), 551-563. [Link]

Fresco, D. M., Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., & Ritter, M. (2013). Emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 282-300. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.02.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ghaderi, F., Akrami, N., Namdari, K., & Abedi, A. (2022). [Comparing the effects of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy and transdiagnostic treatment on symptoms of patients with generalized anxiety disorder comorbid with depression (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 27(4), 440-457. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.4.3067.3]

Greenberg, D. M., Kolasi, J., Hegsted, C. P., Berkowitz, Y., & Jurist, E. L. (2017). Mentalized affectivity: A new model and assessment of emotion regulation. PloS One, 12(10), e0185264. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0185264] [PMID] [PMCID]

Gruber, M., Doering, S., & Blüml, V. (2020). Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(1), 62-69. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000556] [PMID]

Hamidpour, H., Dolatshai, B., Pour Shahbaz, A., & Dadkhah, A. (2011). The efficacy of schema therapy in treating women’s generalized anxiety disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 16 (4), 420-431. [Link]

Hengartner, M. P. (2015). The detrimental impact of maladaptive personality on public mental health: A challenge for psychiatric practice. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 87. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hoyer, J., Beesdo, K., Gloster, A. T., Runge, J., Höfler, M., & Becker, E. S. (2009). Worry exposure versus applied relaxation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(2), 106-115. [DOI:10.1159/000201936] [PMID]

Hunot, V., Churchill, R., Silva de Lima, M., & Teixeira, V. (2007). Psychological therapies for generalised anxiety disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2007(1), CD001848. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001848.pub4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jurist, E. (2018). Minding emotions: Cultivating mentalization in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Publications. [Link]

Kennedy, K. A., & Barlow, D. (2018). The unifed treatment for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: An introduction. In D. H. Barlow, & T. Farchione (Eds.), Applications of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders (pp.1-16). Oxford: Oxford Academic. [DOI:10.1093/med-psych/9780190255541.003.0001]

Koenigsberg, J. Z. (2021). Anxiety disorders: Integrated psychotherapy approaches. New York: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780429023637]

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and invento-ry for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1879-1890. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291711002674] [PMID] [PMCID]

Latas, M., & Milovanovic, S. (2014). Personality disorders and anxiety disorders: What is the relationship? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(1), 57-61. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000025] [PMID]

Leahy, R. L., Holland, S. J., & McGinn, L. K. (2011). Treatment plans and interventions for depression and anxiety disorders. New York: Guilford press. [Link]

Leichsenring, F., & Steinert, C. (2018). Towards an evidence-based unifed psychodynamic protocol for emotional disorders. Journal of Affective Disor-ders, 232, 400-416. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.036] [PMID]

Levey, D. F., Gelernter, J., Polimanti, R., Zhou, H., Cheng, Z., & Aslan, M., et al. (2020). Reproducible genetic risk loci for anxiety: Results from -200,000 participants in the Million Veteran Program. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(3), 223-232. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030256] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mennin, D. S., & Fresco, D. M. (2010). Emotion regulation as an integrative framework for understanding and treating psychopathology. In A. M. Kring & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 356-379). New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Dennis, J. (2014). Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 179-183. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.010]

Mohammadi, M. R., Pourdehghan, P., Mostafavi, S. A., Hooshyari, Z., Ahmadi, N., & Khaleghi, A. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, predictors, and comorbidity in children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102234. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102234] [PMID]

Newby, J. M., Mewton, L., & Andrews, G. (2017). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 25-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.002] [PMID]

Norton, P. J., & Barrera, T. L. (2012). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specefic CBT for anxiety disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled nonin-feriority trial. Depression and Anxiety, 29(10), 874-882. [DOI:10.1002/da.21974] [PMID] [PMCID]

Norton, P. (2017). Transdiagnostic approaches to the understanding and treatment of anxiety and related disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 1-3 [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.02.004] [PMID]

Osma, J., Martínez-García, L., Quilez-Orden, A., & Peris-Baquero, Ó. (2021). Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in medical conditions: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5077. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18105077] [PMID] [PMCID]