Volume 9, Issue 2 (Spring 2021)

PCP 2021, 9(2): 81-92 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Seyed Karimi S, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Falsafinejad M R. Psychological Challenges of Transition to Parenthood in First-time Parents. PCP 2021; 9 (2) :81-92

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-745-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-745-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Education Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Assessment and Measurement, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran. ,falsafinejad@atu.ac.ir

2- Department of Assessment and Measurement, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 747 kb]

(5687 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8167 Views)

Full-Text: (8126 Views)

1. Introduction

Family, like an individual, encounters developmental stages. Furthermore, the relationships between family members and their roles significantly alter over time (Stella-Haddox, 2002). A developmental stage of the family is the transition to parenthood that may affect marital satisfaction. Besides, men and women differently experience the transition to parenthood, i.e., partly because they play different roles as parents (Davoudi, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee & Falsafinejad, 2018). Major characteristics affect the quality of first-time parents’ relationships, including material, physical, and emotional resources (Pacey, 2004). With the birth of the first child, spouses experience a parental subsystem and assume a parenthood role; subsequently, transforming the child’s life and acting as caregivers, educators, planners, and managers of the child throughout life (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, 2019). No event in human life, such as the birth of a child, requires a rapid change in lifestyle, plans, and functions of the parents and family. Parents who are unable to adjust to the new situation may encounter anxiety, i.e., because of the developed challenges (Lawrence, Nylen & Cobb, 2007). Most first-time parents experience marital dissatisfaction during such transition (Kohn et al., 2012). A longitudinal meta-analysis of studies on parenthood signified that marital satisfaction significantly decreases in the first two years after childbirth (Mitnick, Heyman & Smith Slep 2009).

Declined marital satisfaction occurs much faster and greater in this population, compared to the couples without children (Lawrence et al., 2007). The average decrease in marital satisfaction in first-time parents is probably due to changes in parents’ roles. The birth of a child initially imposes about 40 hours of extra work on the family (Lévesque, Bisson, Charton & Fernet 2020). Such alternations are to some extent gender-oriented; familial roles are at odds with prenatal expectations and prior balance; thus, such a new arrangement can generate negative emotions (Twenge, Keith Campbell & Foster, 2003). Sleep deprivation in first-time parents is also almost a global challenge (Medina, Lederhos & Lillis, 2009). Besides, parents have less time for enjoyable activities, such as meeting friends and exercising. Caring for the baby takes the couples’ time; consequently, intimacy decreases between the spouses (Claxton & Perry-Jenkins, 2008). Other studies also indicated that partner support decreases 5 months postpartum. Additionally, a loss of libido and decreased sexual desire are common in this period (Hipp, Low & van Anders, 2012). Another reason for decreased marital satisfaction can be disagreement about raising a child; another source of conflict can be the division of tasks and work at home (Davoudi et al., 2018).

Children do not impose negative and destructive effects on the couples’ relationships; however, they impose increased socioeconomic pressures and reduce the time of spouses being together. Parents who experience higher levels of socioeconomic complications are more prone to develop greater stress and tension. Employed women who reported lower levels of social support also stated declined marital adjustment (Deave, Johnson, & Ingram, 2008). Empirical studies suggested that educating and informing partners about tasks and developments in the family life can change marital satisfaction (Falsafinejad, Mazinani & Etemadi, 2011; Brown & Davies, 2014). In the transition to parenthood, couples report the highest divorce rates and marital problems (McGoldrick & Shibusawa, 2012). Besides, divorce statistics at this life stage indicate marital and sexual problems (Pacey, 2004; Khodabakhshi Koolaee, 2019). Parenting is a tense and challenging stage for spouses. The findings of studies conducted in other countries cannot be generalized to Iranian society due to cultural differences. Therefore, surveying couples’ psychological challenges associated with the transition to parenthood is of theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, exploring couples’ challenges concerning the transition to parenthood can contribute to developing relevant knowledge and information and facilitate future studies on such transition. Practically, family and marriage experts and counselors, midwives, and nurses could gain deep insights from the experiences of families in the transition to parenthood. This, in turn, can motivate future research. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the psychological challenges of the transition to parenthood in first-time parents.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study employed a qualitative method based on a content analysis approach to explore the psychological challenges of the transition to parenthood in first-time parents. This study’s purpose was not to test predetermined theories and hypotheses; we rather explored the research participants’ experiences to provide a comprehensive understanding of their psychological challenges in the transition to parenthood. Besides, we determined their underlying and intervening factors, strategies, and consequences, in this respect. To explore the challenges of the transition to parenthood in more detail, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the research participants. Interviews, as a data collection technique, focus on the research problem; they are flexible enough to allow the respondents to address the critical aspects of the problem from their viewpoints (Creswell & Báez, 2020; Karimzadeh, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Davoodi, & Heidari, 2020).

The research participants were selected by a purposive sampling method based on the theoretical saturation criterion. Given the restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some issues with sample selection. To eliminate these problems, the researchers invited couples via social media to participate in this study. The interviews continued until the data were theoretically saturated. Before conducting the interviews, some explanations were provided about the research procedure to all study participants. Additionally, they were allowed to discontinue cooperation with the study at any stage. The research participants were also ensured that their data would remain confidential. The reason for recording the study participants’ voices during the interviews was explained to them. The interviews were initiated after obtaining permission from the study participants. The inclusion criteria of the study were having the first child under the age of 4 years, living in Tehran City, Iran, no history of drug abuse, no acute biopsychological conditions, and not being divorced, or filing for divorce. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria were the diagnosis of acute biopsychological illnesses in the couples that could directly affect the study results, the lack of co-operation during the interviews, the unwillingness of either party to continue the interview.

The interview questions were developed beforehand to address all aspects of the psychological challenges of the spouses in the transition to parenthood. The questions were not necessarily asked in sequence; they were rather probed as the interview session progressed per the study participants’ responses. At the beginning of the session, the interview initiated with questions to collect the study participants’ demographic data, such as age, educational level, occupational status, marriage duration, the birth order of each individual, the child’s age and gender, and a history of abortion or infertility. The research participants were also asked about the time and the reason(s) they decided to have children. Furthermore, questions were probed to thoroughly examine the challenges encountered by the study participants in their marital relationships; relationships with extended families; their worries and concerns; their readiness to accept the responsibility of parenthood and readjust with the family structures. Examples of the questions asked were as follows: What was your attitude towards the role of parenthood before your child was born? After the birth of your child, how did your attitude towards the parenthood role change? In some cases, probing questions (e.g. Can you explain more?) were administrated. Other questions asked in the interviews were as follows: What changes were made in your duties as a parent after the birth of the child? To what extent can your families (grandparents) help you to perform your parenting roles?

The questions were asked in a manner to prevent inducing a sense of survey in the interviewee. Besides, the researcher (counselor) established rapport with the study participants and gained their trust; subsequently, they attempted to identify all aspects of the challenges experienced by the study participants in the transition to parenthood. The interviews with each couple lasted 45-80 minutes (mean= 62 minutes), depending on the extent of their cooperativeness. The interviews were conducted face to face in two counseling centers, one in the west of Tehran and the other in the center of Tehran. Due to the restrictions concerning attending public centers, 19 face-to-face interviews were conducted with 9 couples. Additionally, the 8 other couples were interviewed via video calls. The researcher tried to eliminate any difference between face-to-face interviews and video calls respecting the time and quality of the interview. The interviews were transcribed word by word. Besides, to ensure the accuracy of the transcribed files, the recorded audio files of the interviewed were re-checked. The reactions and moods of the interviewees that could not be recorded in the audio files were observed, recorded, and analyzed through note-taking. Finally, a paradigmatic model of contextual conditions, intervening factors, strategies, and consequences of the challenges of the transition to parenthood was developed.

The collected data were analyzed using a qualitative method based on a content analysis approach. The qualitative approach discovers theories, concepts, hypotheses, and theorems via a regular process directly from the data, instead of inferring them from previous assumptions and the existing theoretical frameworks (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The content analysis process requires applying several stages of data collection, revision, and examination of the relationships between information categories. In qualitative studies, especially those conducted based on the content analysis approach, data are collected using exploratory interviews; accordingly, data collection and analysis are simultaneously performed to assist the discovery of the theory underlying the data. The obtained data were coded and categorized using a content analysis method in MAXQDA.

The collected data were simultaneously analyzed with the sampling procedure using a five-step qualitative content analysis method, as follows: the researchers transcribed the recorded interviews; the transcripts were reviewed to reach a general understanding of the content; significant units and primary codes were identified; the primary codes were classified into broader categories, and the latent concepts were specified (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004).

Finally, the 4 criteria proposed by Guba & Lincoln (1994) were used to validate the obtained results. According to Guba & Lincoln’s (1994) credibility criterion, the researcher described the study steps and outlined the evidence to address the main issue and other related issues. Moreover, the significant statements by the study participants were quoted and the extracted themes were described. The confirmability criterion was used to ensure that the findings were not based on predictions but were extracted from the interview data. Additionally, concerning dependability criteria, the researcher tried to establish a favorable relationship with the study participants and gain their trust; as a result, that they could openly and freely discuss their issues. The researcher avoided guessing the study participants’ problems. The researchers also attempted to extract the themes and related categories using the data provided by the study participants. Moreover, to increase the validity of the research findings, several subject-matter experts in the fields of biostatistics, psychiatric nursing, counseling, and psychology were requested to check all study procedures and provide comments for possible revisions. For the transferability of data, the researchers referred to the participants for approved clarifications. Furthermore, to enrich the data, it was tried to select the participants from different populations with maximum variation in demographic characteristics. A written informed consent form was obtained from the study participants for conducting and recording the interviews; voluntary participation in and withdrawal from the study; the confidentiality of the participants’ information, including their names, phone numbers, and addresses. Besides, the recorded interviews were transcribed by the researchers.

3. Results

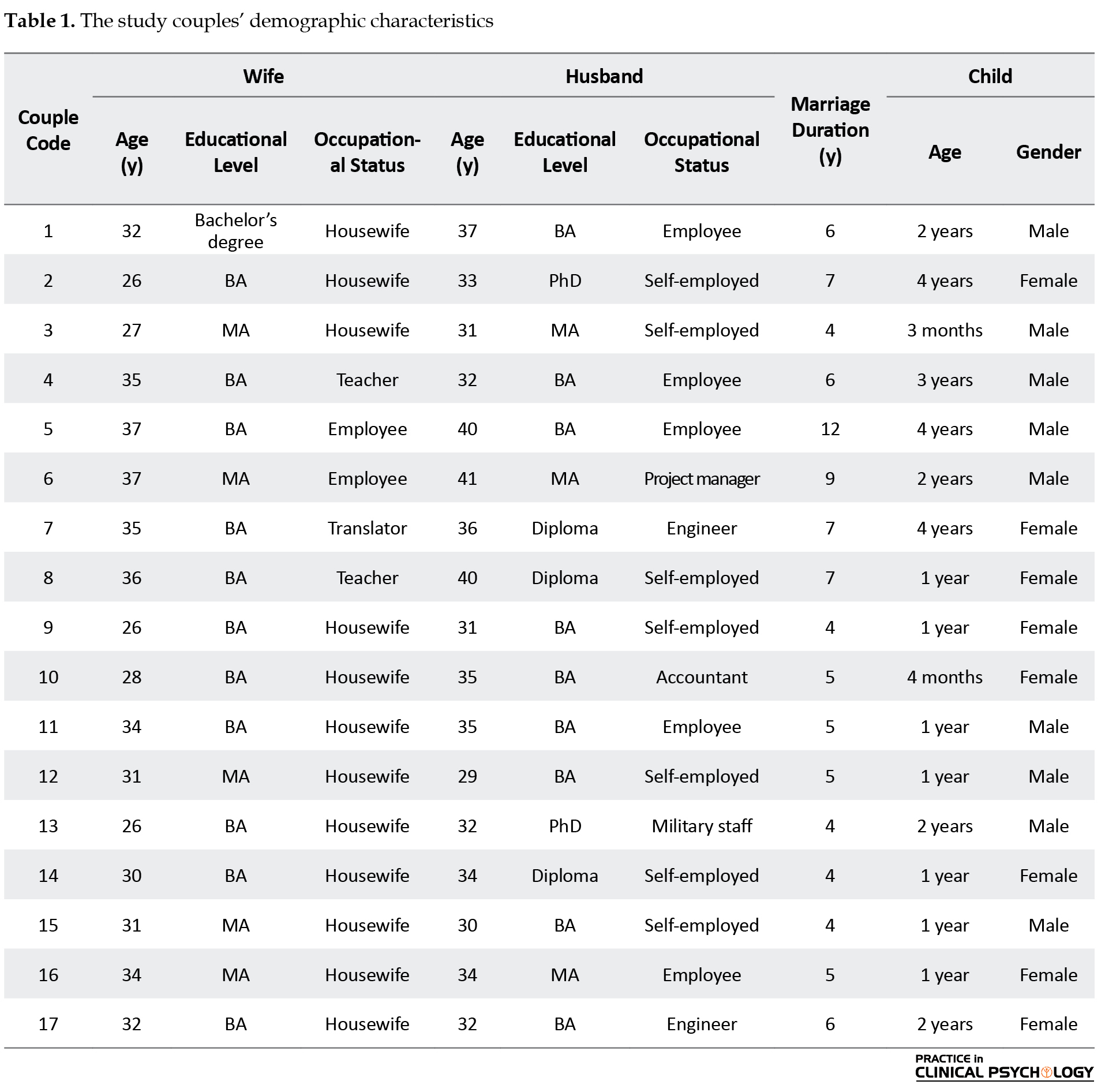

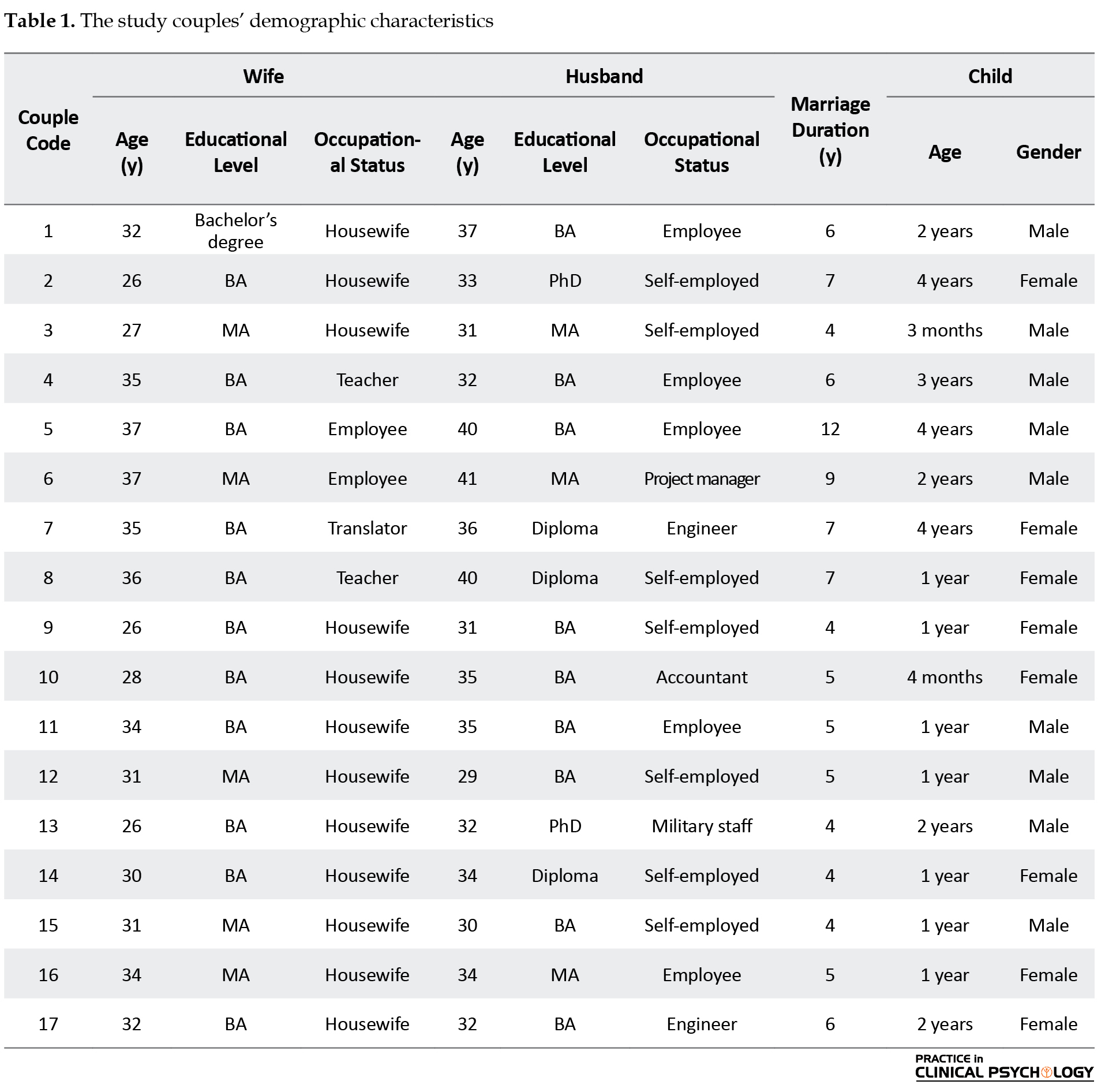

The study participants consisted of 17 couples. The female participants were aged 26 to 37 years and the male participants were aged 29 to 41 years. All explored couples had one child aged 3 months to 4 years. Besides, the research participants’ marriage duration varied from 4 to 12 years. The female participants’ educational level varied from a bachelor’s to a master’s degree; the male subjects’ educational level ranged from a high school diploma to a PhD degree. The study participants’ demographic data are presented in Table 1.

The data analysis revealed 67 initial codes; from which, 8 main categories were extracted, then the core theme was presented. Table 2 illustrates the extracted initial, core categories, and core theme.

According to the present research findings, that the explored couples addressed the following reasons for childbearing, including the possibility of infertility in the future, husband’s interest in childbearing, a sense of monotony in married life, and interest in developing a family. Transition to parenthood can be a difficult and unpaid responsibility; however, it is the most exciting and satisfying experience for spouses. The data analysis suggested the following extracted themes:

Ambiguity and changes in the spousal role

This extracted subtheme was classified into primary themes, including increased conflicts and disputes between the spouses; fights and conflicts over the assignment of household chores; less frequently appreciating the spouse; coordination and planning problems; hypersensitivity to actions and behavior as a parenting style; great responsibilities and difficulties, and prioritizing the parenthood role over the spousal role. Changes in the role must be made in both spouses to adapt well to the new circumstances; otherwise, they will face problems. “I knew that the mother’s responsibility is higher, but I did not expect so much responsibility. My husband does not help much at home, and most of the housework and childcare are on me, and this issue has affected the quality of our relationship” (Couple #11). “My child is a higher priority than my spouse” (Couple #4).

Duality and conflict in the motherhood role

This subtheme covered some primary themes, including the feeling that the spouse has changed enormously; feeling depressed and confused after childbirth; confusion with the motherhood role; the desire to be an ideal parent for the child; excessive perfectionism in the motherhood role; feeling bored when performing household chores, such as tidying the house, cooking, and caring for the child; the perception that becoming a mother is a heavy burden; feeling the need to read more to meet the daily needs of the child; suggesting that being a mother is a priority over everything, and the parents’ over-responsibility and additional burden. In the transition to parenthood, a parent may initially feel depressed and anxious due to the loss of the previous role as well as the exhausting fatigue caused by the new role. “The changes were so great that I was shocked and depressed by the time my son was 4 months old” (Participant #6). “I thought the motherhood role was much easier, but I found it is too heavy and I feel the need to study more because the older my child gets, the more different her/his needs become, and I have no experience” (Participant #10). “My wife’s attention is too much on her motherhood role and the child is her priority, and I do not have a good feeling when seeing her focus is all on the child” (Participant #5).

Feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals

This fourth subtheme addressed primary themes, including failure to handle personal affairs; failure to pursue hobbies and hobbies, such as sports, walking, and reading books; resigning due to having children; not devoting time to personal goals, like continuing education; failure to socialize with friends and relatives due to parenting; not allocating time to handle personal affairs, and having less time for rest and entertainment. The study participants stated that it was no longer possible to take care of their personal affairs, interests, and hobbies that used to be part of their plans. “I cannot perform my previous activities, such as walking, studying, and exercising, and I used to work, but now I cannot go to work. We cannot have leisure activities, such as going to the cinema and parks because we are always tired of working and taking care of the child” (Participant #1). “I used work as a journalist in a newspaper, but after my child was born, I decided to spend all my time on taking care of the child” (Participant #15).

Psychological and emotional support from the family and the husband

This subtheme was subdivided into primary themes, such as considerable psychological support of both families; the lack of support from the husband; the lack of support from the husband’s family; the wife’s failure to attend and express affection to her husband, and spiritual and psychological support of families, i.e., important than the material support. The support from the original families of the spouses can help the couples to better overcome this challenging period. “We had difficult times. We were both employed and my wife’s family helped a lot to maintain our status” (Participant #5). “We did not have the support of our family and I did half of the housework and childcare so that my wife would not suffer too much pressure” (Participant #4). “I was living at my mother’s house for two months after my childbirth, but afterward, we did not get help from any of the families” (Participant #12).

Parenting disagreements

This subtheme consisted of such primary themes as, fighting over parenting styles; fighting over physical and verbal punishment of the child, e.g. for not using a diaper; severe criticism of the spouse for the child’s misbehavior; constantly criticizing and accusing each other of improperly raising the child; disagreement over the division of tasks in the home; disputes that adversely affect the parent-child relationship, as well as concerns and disagreement about not controlling the child’s misbehavior in the future. Sometimes, the parents disagreed on how to raise the child, leading to parenting problems. Sometimes, the spouses had disagreements and conflicts with their families. “Our biggest disagreement is over how to raise the child. My husband says I am spoiling the child and I think my husband is too strict” [The wife]. “We even disagree on when to stop using diapers and pacifiers and matters like this” [The husband] (Participant #2). “If there is the smallest problem in raising the child, my husband blames me” [the wife]. “If I frown at my child in the presence of my wife’s parents, I will be quarreled immediately” [the husband] (Participant #5).

Changes in sexual relationships

This subtheme accounted for changes in sexual relations. These alternations were explained by primary themes, such as having inadequate time to have sexual relations; the couple feels very tired due to child care; a decline in the frequency of sexual relations; a decline in sexual relations due to the lack of husband demand; psychological stress induced by the lack of or limited sexual relations; the fading of passion between the spouses; decreased libido and arousal in the couples after childbirth; the child sleeps with the parents and the mother constantly takes care of him/her at night; separating the husband’s bed from his wife’s because of the child; no private time for the couples; feeling very distrustful; cold sexual relations; decreased sexual relations due to waking up at night and caring for the child; insufficient rest, and the husband’s sexual dysfunction due to not having regular sexual intercourse. These changes were highlighted in almost all the interviews by the study participants. “We do not have sexual relations as frequently as before, and this bothers and stresses me. This is because we do not know when the baby goes to sleep and we get tired” (Participant #3). “Our sexual relations were good before and we were satisfied, but now we rarely have such relations; I do not have the sexual desire at all” [the wife]. “It was not a mental problem, but not having sexual intercourse created physical problems for me. This is an essential challenge for me” [the husband] (Participant #6).

Fear of the failure to financially support the child: This subtheme was extended into primary themes, including the lack of financial readiness to have children; decreased income after the child was born; decreased income as the wife had to resign after pregnancy; the uncertainty of the socioeconomic conditions of the country; an uncertain economic future; fear of raising a child in poverty, like their parents; worrying about uncertain national conditions; working more and having multiple jobs due to the financial burden of raising the child; worrying about social conditions of the community, and the desire for migration and raising the child in a more economically stable country. The child’s financial support was also among the major issues highlighted by numerous study participants; it was a crucial concern of families from all walks of life. “After the birth of my child, I became more economically active and my socioeconomic worries make me stressful” (Participant #11). “I think most of our issues are due to financial problems, and if our economic situation was more stable we would be better parents” [the husband] (Participant #7).

Dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes

The last subtheme found in this study was the mothers’ dissatisfaction with their appearance and weight changes. The study subjects complained about excessive obesity after childbirth; feeling bad due to not having physical fitness; changes in body fitness and size after pregnancy, and feelings of physical deformity and unattractiveness. Weight gain and physical changes after childbirth were essential issues for some female participants. “I have gained about 25 kg of weight and I had changed a lot in appearance. I even felt my face was swollen and I did not leave the house for a long time and that made me a little bit depressed” (Participant #2). Figure 1 shows a paradigmatic model of the explored couple’s challenges in the transition to parenthood.

4. Discussion

The present study results suggested that the most serious challenges faced by couples in the transition to parenthood included the following: ambiguity and changes in the spousal role; duality and conflict in the motherhood role; feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals; psychological and emotional support from the family and husband; parenting disagreements; changes in sexual relations; fear of the failure to financially support the child; dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes, and differences in parenting styles. The core theme was the transition to parenthood; from couples to parents.

These findings were in line with those of previous studies. For instance, Twenge et al. (2003) found that fighting over the allocation of household chores and

responsibilities was a major challenge for parents. The female participants in this study were dissatisfied with the gender-based assignment of household chores; they stated that their husbands were less cooperative in household chores. Gender differences at the time of transition to parenthood are considered a crisis. Furthermore, they cause gender-biased perceptions of motherhood and fatherhood that affect the behavior of each parent. Subsequently, they lead to the wife’s fatigue and dissatisfaction. Husbands’ unawareness and unwillingness to participate in childbirth preparation and subsequent programs are among the problems of couples. Therefore, educating couples, providing information and training before childbirth on breastfeeding, child care, and raising awareness on the potential changes in marital relationships are essential (Deave, Johnson & Ingram, 2008; Deave & Johnson, 2008; Baldwin, Malone, Sandall & Bick, 2019). Men experience extensive stress after having a child, including fatigue, poor concentration, and irritability (Darwin et al., 2017). The transition to parenthood represents a significant life event that increases vulnerability to psychological disorders. Postpartum depression and parental anxiety are among the most frequent psychological disorders. Depression, anxiety, and stress after childbirth can be dangerous to a child’s biopsychological health (Epifanio, Genna, De Luca, Roccella & La Grutta, 2015; Pinquart & Teubert, 2010).

Philpott, Savage, Leahy-Warren & FitzGearld (2020) suggested that depression is prevalent in the perinatal period in couples. Factors, such as the father’s age, lower education, unplanned pregnancy, and maternal depression impact the father’s depression (Philpott et al., 2020). Dualities and conflicts of motherhood roles were found as other challenges in this study. Dave et al. (2008) argued that unawareness about parenthood changes in child care as well as relationships with the spouse cause conflicts.

Parenting disagreements were sometimes developed between the husband and wife, and each parent considers it from their perspective. Sometimes, these disagreements occurred between the parents and the grandparents of the child, and most of the time, the couples were too much dependent on their families; there was no restructuring and readjustment with the original families. Numerous couples with this problem stated that they had excessively unplanned and unrestricted relations with the families of origin due to the wife’s employment or proximity of their place of residence to the family of origin (Zartler, Schmidt, Schadler, Rieder & Richter, 2021).

One of the most serious challenges for couples in the transition to parenthood was changes in their sexual relationships. The presence of a child who requires 100% parental support for survival and enduring the day-to-day care of the child often forces the parents to allocate some time to rest. They feel tired due to the tedious work of caring for the baby. Accordingly, the sexual relations of the couples undergo some changes. In addition to fatigue, some male and female participants reported a sharp decrease in sexual desire. A decline in sexual desires in some women was due to childbirth and its complications. Besides, some women attributed this problem to additional responsibility, the burden of child care, and the lack of husband support. In some cases, this problem was due to the feeling of distrust and being suspicious of the husband’s engagement in extramarital affairs. Some male participants stated that they refused to ask for sexual intercourse when they considered their wife’s conditions. Furthermore, some study subjects mentioned that sometimes, they did not even think about having sexual intercourse at all due to their busy schedule. Studies revealed that the transition to parenthood affects couples’ romantic relationships (Alves et al., 2019). However, Doss & Rhoades (2017) found that having children is associated with moments of joy and sorrow. Accordingly, the romantic relationship of spouses goes back to before having children; if they have loved each other before having children, their love would continue after childbearing. Furthermore, couples who experienced higher levels of anxiety encounter further problems (Doss & Rhoades, 2017).

Rosen, Bailey & Muise (2018) also reported that numerous first-time parents are concerned about their level of interest in sexual relationships. The difference in the intensity of sexual desire in couples is crucial. When one party experiences a stronger sexual desire than the other, the couple’s conflicts became much greater. If both spouses had lower desires or similar levels of sexual desire, they reported greater marital satisfaction (Rosen et al., 2018). Tavares, Schlagintweit, Nobre & Rosen (2019) documented that parents’ sexual satisfaction was associated with less stress in their marital life. They also found that positive sexual experiences are associated with a lower perception of stress. Couples’ sexual wellbeing may be important for coping with post-child stress (Tavares et al., 2019).

Lévesque et al. addressed parental outcomes. In a qualitative study and post-content analysis, they identified 3 major challenges during the transition to parenthood, as follows: the loss of meaning of individuality and matrimony, given the original identity as parents; the equality of parental responsibilities and division of labor for child care, and the impact of social norms and beliefs on the development of the concept of parenthood. They stated that challenges, including fatigue and sleep deprivation, social isolation, loneliness, and employment were also accompanied by barriers to adapting to the parenting role (Lévesque et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

The present study data indicated that parenthood can be a positive and a negative experience. The main challenges for couples in the transition to parenthood included ambiguity and changes in the spousal role; duality and conflict in the motherhood role; feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals; psychological and emotional support from the family and husband; parenting disagreements; changes in sexual relationships; fear of the failure to financially support the child; dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes, and differences in parenting styles. Moreover, factors underlying these challenges were the family’s economic conditions; family conditions; the main family’s support; individual characteristics, and the quality of the couple’s previous adjustment; these variables affected the severity and quality of coping with the challenges. The strategies adopted by the couples to manage these challenges were to respond sensibly to this transition; interact and participate in solving the challenges; use family resources, and attempting to improve financial conditions. The consequences of the transition to parenthood fluctuated depending on the characteristics and conditions of the couple from conflict, incompatibility, and dissatisfaction to high satisfaction. Thus, transition to parenthood requires educating and informing spouses; improving marital functioning; balancing individual circumstances; family support, and socioeconomic stability.

This study was conducted with some limitations. First, qualitative research is based on the life experiences and psychological reactions of individuals who have grown up in a specific sociocultural context (Iranian society in this study). Second, this study was conducted in Tehran; thus, its findings, in general, do not reflect the parenthood challenges of the entire population of couples in Iran.

Providing education; holding parenting training courses during pregnancy; fathers participating in courses, and preparing couples for the transition to parenthood are essential measures; these measures can be taken by health professionals, including psychologists and family counselors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was registered at Khatam University (Code: IR.KHATAM.REC.1399.16).

Funding

This research received no grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Alves, S., Milek, A., Bodenmann, G., Fonseca, A., Canavarro, M. C., & Pereira, M. (2019). Romantic attachment, dyadic coping, and parental adjustment across the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships, 26(2), 286-309. [DOI:10.1111/pere.12278]

Baldwin, Sh., Malone, M., Sandall, J., & Bick, D. (2019). A qualitative exploratory study of UK first-time fathers’ experiences, mental health, and wellbeing needs during their transition to fatherhood. BMJ Open, 9(9), e030792. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030792] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brown, A., & Davies, R. (2014). Fathers’ experiences of supporting breastfeeding: Challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10(4), 510-26. [DOI:10.1111/mcn.12129] [PMID] [PMCID]

Claxton, A., & Perry‐Jenkins, M. (2008). No fun anymore: Leisure and marital quality across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 28-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00459.x] [PMID]

Creswell, J. W., & Báez, J. C. (2020). 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com/books?id=AvNRzQEACAAJ&dq

Darwin, Z., Galdas, P., Hinchliff, S., Littlewood, E., McMillan, D., & McGowan, L., et al. (2017). Fathers’ views and experiences of their own mental health during pregnancy and the first postnatal year: A qualitative interview study of men participating in the UK Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 45. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-017-1229-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Davoudi, Z., Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, A., & Falsafinejad, M. R. (2018). [The effectiveness of training of self-help program toward the parenthood on worry in pregnancy period among the nulliparous women (Persian)]. Journal of Health Literacy, 3(1), 61-71. [DOI:10.22038/JHL.2018.10932]

Deave, T., Johnson, D., & Ingram, J. (2008). Transition to parenthood: The needs of parents in pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 8, 30. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-8-30] [PMID]

Deave, T., & Johnson, D. (2008). The transition to parenthood: What does it mean for fathers? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(6), 626-33. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04748.x] [PMID]

Doss, B. D., & Rhoades, G. K. (2017). The transition to parenthood: Impact on couples’ romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 25-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.003] [PMID]

Epifanio, M. S., Genna, V., De Luca, C., Roccella, M., & La Grutta, S. (2015). Paternal and maternal transition to parenthood: The risk of postpartum depression and parenting stress. Pediatric Reports, 7(2), 5872. [DOI:10.4081/pr.2015.5872] [PMID] [PMCID]

Falsafinejad, M. R., Mazinani, H., & Etemadi, A. (2011). [Effects of awareness from developmental family life cycle tasks on student’s marital satisfaction (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Sciences, 9(36), 452-69. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1081053

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-98625-005

Hipp, L. E., Low, L. K., & van Anders, S. M. (2012). Exploring women’s postpartum sexuality: Social, psychological, relational, and birth‐related contextual factors. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(9), 2330-41. [DOI:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02804.x] [PMID]

Karimzadeh, M., Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Davoodi, H., & Heidari, H. (2020). Experiences and worries in mothers with children suffering from ADHD: A Grounded Theory Study. Caspian Journal of Pediatrics, 6(1), 390-8. http://caspianjp.ir/article-1-115-en.html

Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A. (2019). [Family therapy and parent training program & models (Persian)]. Tehran: Jangal Publication. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/1925039

Kohn, J. L., Rholes, S. W., Simpson, J. A., McLeish Martin III, A., Tran, S., & Wilson, C. L. (2012). Changes in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: The role of adult attachment orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(11), 1506-22. [DOI:10.1177/0146167212454548] [PMID]

Lawrence, E., Nylen, K., & Cobb, R. J. (2007). Prenatal expectations and marital satisfaction over the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 155-64. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.155] [PMID]

Lévesque, S., Bisson, V., Charton, L., & Fernet, M. (2020). Parenting and relational well-being during the transition to parenthood: Challenges for first-time parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1938-56. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-020-01727-z]

McGoldrick, M., & Shibusawa, T. (2012). The family life cycle. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (pp. 375–398). New York: The Guilford Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=3C15kY3XnMUC&dq

Medina, A. M., Lederhos, C. L., & Lillis, T. A. (2009). Sleep disruption and decline in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. Families, Systems, & Health, 27(2), 153-60. [DOI:10.1037/a0015762] [PMID]

Mitnick, D. M., Heyman, R. E., & Smith Slep, A. M. (2009). Changes in relationship satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(6), 848-52. [DOI:10.1037/a0017004] [PMID] [PMCID]

Pacey, S. (2004). Couples and the first baby: Responding to new parents' sexual and relationship problems. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 19(3), 223-46. [DOI:10.1080/14681990410001715391]

Philpott, L. F., Savage, E., Leahy-Warren, P., & FitzGearld, S. (2020). Paternal perinatal depression: A narrative review. International Journal of Men’s Social and Community Health, 3(1), e1-15. [DOI:10.22374/ijmsch.v3i1.22]

Pinquart, M., & Teubert, D. (2010). A meta‐analytic study of couple interventions during the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 59(3), 221-31. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00597.x]

Rosen, N. O., Bailey, K., & Muise, A. (2018). Degree and direction of sexual desire discrepancy are linked to sexual and marital satisfaction in couples transitioning to parenthood. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(2), 214-25. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1321732] [PMID]

Stella-Haddox, F. M. (2002). Marital satisfaction and expectations in the first and last stages of the family life cycle [PhD dissertation]. San Diego: United States International University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/3193e59155c0dc08d78cd34de111dbee/1

Tavares, I. M., Schlagintweit, H. E., Nobre, P. J., & Rosen, N. O. (2019). Sexual well-being and perceived stress in couples transitioning to parenthood: A dyadic analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 19(3), 198-208. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.07.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

Twenge, J. M., Keith Campbell, W., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574-83. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00574.x]

Zartler, U., Schmidt, E. M., Schadler, C., Rieder, I., & Richter, R. (2021). “A Blessing and a Curse” couples dealing with ambivalence concerning grandparental involvement during the transition to parenthood-a longitudinal study. Journal of Family Issues, 42(5), 958-83. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X20950786]

Family, like an individual, encounters developmental stages. Furthermore, the relationships between family members and their roles significantly alter over time (Stella-Haddox, 2002). A developmental stage of the family is the transition to parenthood that may affect marital satisfaction. Besides, men and women differently experience the transition to parenthood, i.e., partly because they play different roles as parents (Davoudi, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee & Falsafinejad, 2018). Major characteristics affect the quality of first-time parents’ relationships, including material, physical, and emotional resources (Pacey, 2004). With the birth of the first child, spouses experience a parental subsystem and assume a parenthood role; subsequently, transforming the child’s life and acting as caregivers, educators, planners, and managers of the child throughout life (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, 2019). No event in human life, such as the birth of a child, requires a rapid change in lifestyle, plans, and functions of the parents and family. Parents who are unable to adjust to the new situation may encounter anxiety, i.e., because of the developed challenges (Lawrence, Nylen & Cobb, 2007). Most first-time parents experience marital dissatisfaction during such transition (Kohn et al., 2012). A longitudinal meta-analysis of studies on parenthood signified that marital satisfaction significantly decreases in the first two years after childbirth (Mitnick, Heyman & Smith Slep 2009).

Declined marital satisfaction occurs much faster and greater in this population, compared to the couples without children (Lawrence et al., 2007). The average decrease in marital satisfaction in first-time parents is probably due to changes in parents’ roles. The birth of a child initially imposes about 40 hours of extra work on the family (Lévesque, Bisson, Charton & Fernet 2020). Such alternations are to some extent gender-oriented; familial roles are at odds with prenatal expectations and prior balance; thus, such a new arrangement can generate negative emotions (Twenge, Keith Campbell & Foster, 2003). Sleep deprivation in first-time parents is also almost a global challenge (Medina, Lederhos & Lillis, 2009). Besides, parents have less time for enjoyable activities, such as meeting friends and exercising. Caring for the baby takes the couples’ time; consequently, intimacy decreases between the spouses (Claxton & Perry-Jenkins, 2008). Other studies also indicated that partner support decreases 5 months postpartum. Additionally, a loss of libido and decreased sexual desire are common in this period (Hipp, Low & van Anders, 2012). Another reason for decreased marital satisfaction can be disagreement about raising a child; another source of conflict can be the division of tasks and work at home (Davoudi et al., 2018).

Children do not impose negative and destructive effects on the couples’ relationships; however, they impose increased socioeconomic pressures and reduce the time of spouses being together. Parents who experience higher levels of socioeconomic complications are more prone to develop greater stress and tension. Employed women who reported lower levels of social support also stated declined marital adjustment (Deave, Johnson, & Ingram, 2008). Empirical studies suggested that educating and informing partners about tasks and developments in the family life can change marital satisfaction (Falsafinejad, Mazinani & Etemadi, 2011; Brown & Davies, 2014). In the transition to parenthood, couples report the highest divorce rates and marital problems (McGoldrick & Shibusawa, 2012). Besides, divorce statistics at this life stage indicate marital and sexual problems (Pacey, 2004; Khodabakhshi Koolaee, 2019). Parenting is a tense and challenging stage for spouses. The findings of studies conducted in other countries cannot be generalized to Iranian society due to cultural differences. Therefore, surveying couples’ psychological challenges associated with the transition to parenthood is of theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, exploring couples’ challenges concerning the transition to parenthood can contribute to developing relevant knowledge and information and facilitate future studies on such transition. Practically, family and marriage experts and counselors, midwives, and nurses could gain deep insights from the experiences of families in the transition to parenthood. This, in turn, can motivate future research. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the psychological challenges of the transition to parenthood in first-time parents.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study employed a qualitative method based on a content analysis approach to explore the psychological challenges of the transition to parenthood in first-time parents. This study’s purpose was not to test predetermined theories and hypotheses; we rather explored the research participants’ experiences to provide a comprehensive understanding of their psychological challenges in the transition to parenthood. Besides, we determined their underlying and intervening factors, strategies, and consequences, in this respect. To explore the challenges of the transition to parenthood in more detail, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the research participants. Interviews, as a data collection technique, focus on the research problem; they are flexible enough to allow the respondents to address the critical aspects of the problem from their viewpoints (Creswell & Báez, 2020; Karimzadeh, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Davoodi, & Heidari, 2020).

The research participants were selected by a purposive sampling method based on the theoretical saturation criterion. Given the restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some issues with sample selection. To eliminate these problems, the researchers invited couples via social media to participate in this study. The interviews continued until the data were theoretically saturated. Before conducting the interviews, some explanations were provided about the research procedure to all study participants. Additionally, they were allowed to discontinue cooperation with the study at any stage. The research participants were also ensured that their data would remain confidential. The reason for recording the study participants’ voices during the interviews was explained to them. The interviews were initiated after obtaining permission from the study participants. The inclusion criteria of the study were having the first child under the age of 4 years, living in Tehran City, Iran, no history of drug abuse, no acute biopsychological conditions, and not being divorced, or filing for divorce. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria were the diagnosis of acute biopsychological illnesses in the couples that could directly affect the study results, the lack of co-operation during the interviews, the unwillingness of either party to continue the interview.

The interview questions were developed beforehand to address all aspects of the psychological challenges of the spouses in the transition to parenthood. The questions were not necessarily asked in sequence; they were rather probed as the interview session progressed per the study participants’ responses. At the beginning of the session, the interview initiated with questions to collect the study participants’ demographic data, such as age, educational level, occupational status, marriage duration, the birth order of each individual, the child’s age and gender, and a history of abortion or infertility. The research participants were also asked about the time and the reason(s) they decided to have children. Furthermore, questions were probed to thoroughly examine the challenges encountered by the study participants in their marital relationships; relationships with extended families; their worries and concerns; their readiness to accept the responsibility of parenthood and readjust with the family structures. Examples of the questions asked were as follows: What was your attitude towards the role of parenthood before your child was born? After the birth of your child, how did your attitude towards the parenthood role change? In some cases, probing questions (e.g. Can you explain more?) were administrated. Other questions asked in the interviews were as follows: What changes were made in your duties as a parent after the birth of the child? To what extent can your families (grandparents) help you to perform your parenting roles?

The questions were asked in a manner to prevent inducing a sense of survey in the interviewee. Besides, the researcher (counselor) established rapport with the study participants and gained their trust; subsequently, they attempted to identify all aspects of the challenges experienced by the study participants in the transition to parenthood. The interviews with each couple lasted 45-80 minutes (mean= 62 minutes), depending on the extent of their cooperativeness. The interviews were conducted face to face in two counseling centers, one in the west of Tehran and the other in the center of Tehran. Due to the restrictions concerning attending public centers, 19 face-to-face interviews were conducted with 9 couples. Additionally, the 8 other couples were interviewed via video calls. The researcher tried to eliminate any difference between face-to-face interviews and video calls respecting the time and quality of the interview. The interviews were transcribed word by word. Besides, to ensure the accuracy of the transcribed files, the recorded audio files of the interviewed were re-checked. The reactions and moods of the interviewees that could not be recorded in the audio files were observed, recorded, and analyzed through note-taking. Finally, a paradigmatic model of contextual conditions, intervening factors, strategies, and consequences of the challenges of the transition to parenthood was developed.

The collected data were analyzed using a qualitative method based on a content analysis approach. The qualitative approach discovers theories, concepts, hypotheses, and theorems via a regular process directly from the data, instead of inferring them from previous assumptions and the existing theoretical frameworks (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The content analysis process requires applying several stages of data collection, revision, and examination of the relationships between information categories. In qualitative studies, especially those conducted based on the content analysis approach, data are collected using exploratory interviews; accordingly, data collection and analysis are simultaneously performed to assist the discovery of the theory underlying the data. The obtained data were coded and categorized using a content analysis method in MAXQDA.

The collected data were simultaneously analyzed with the sampling procedure using a five-step qualitative content analysis method, as follows: the researchers transcribed the recorded interviews; the transcripts were reviewed to reach a general understanding of the content; significant units and primary codes were identified; the primary codes were classified into broader categories, and the latent concepts were specified (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004).

Finally, the 4 criteria proposed by Guba & Lincoln (1994) were used to validate the obtained results. According to Guba & Lincoln’s (1994) credibility criterion, the researcher described the study steps and outlined the evidence to address the main issue and other related issues. Moreover, the significant statements by the study participants were quoted and the extracted themes were described. The confirmability criterion was used to ensure that the findings were not based on predictions but were extracted from the interview data. Additionally, concerning dependability criteria, the researcher tried to establish a favorable relationship with the study participants and gain their trust; as a result, that they could openly and freely discuss their issues. The researcher avoided guessing the study participants’ problems. The researchers also attempted to extract the themes and related categories using the data provided by the study participants. Moreover, to increase the validity of the research findings, several subject-matter experts in the fields of biostatistics, psychiatric nursing, counseling, and psychology were requested to check all study procedures and provide comments for possible revisions. For the transferability of data, the researchers referred to the participants for approved clarifications. Furthermore, to enrich the data, it was tried to select the participants from different populations with maximum variation in demographic characteristics. A written informed consent form was obtained from the study participants for conducting and recording the interviews; voluntary participation in and withdrawal from the study; the confidentiality of the participants’ information, including their names, phone numbers, and addresses. Besides, the recorded interviews were transcribed by the researchers.

3. Results

The study participants consisted of 17 couples. The female participants were aged 26 to 37 years and the male participants were aged 29 to 41 years. All explored couples had one child aged 3 months to 4 years. Besides, the research participants’ marriage duration varied from 4 to 12 years. The female participants’ educational level varied from a bachelor’s to a master’s degree; the male subjects’ educational level ranged from a high school diploma to a PhD degree. The study participants’ demographic data are presented in Table 1.

The data analysis revealed 67 initial codes; from which, 8 main categories were extracted, then the core theme was presented. Table 2 illustrates the extracted initial, core categories, and core theme.

According to the present research findings, that the explored couples addressed the following reasons for childbearing, including the possibility of infertility in the future, husband’s interest in childbearing, a sense of monotony in married life, and interest in developing a family. Transition to parenthood can be a difficult and unpaid responsibility; however, it is the most exciting and satisfying experience for spouses. The data analysis suggested the following extracted themes:

Ambiguity and changes in the spousal role

This extracted subtheme was classified into primary themes, including increased conflicts and disputes between the spouses; fights and conflicts over the assignment of household chores; less frequently appreciating the spouse; coordination and planning problems; hypersensitivity to actions and behavior as a parenting style; great responsibilities and difficulties, and prioritizing the parenthood role over the spousal role. Changes in the role must be made in both spouses to adapt well to the new circumstances; otherwise, they will face problems. “I knew that the mother’s responsibility is higher, but I did not expect so much responsibility. My husband does not help much at home, and most of the housework and childcare are on me, and this issue has affected the quality of our relationship” (Couple #11). “My child is a higher priority than my spouse” (Couple #4).

Duality and conflict in the motherhood role

This subtheme covered some primary themes, including the feeling that the spouse has changed enormously; feeling depressed and confused after childbirth; confusion with the motherhood role; the desire to be an ideal parent for the child; excessive perfectionism in the motherhood role; feeling bored when performing household chores, such as tidying the house, cooking, and caring for the child; the perception that becoming a mother is a heavy burden; feeling the need to read more to meet the daily needs of the child; suggesting that being a mother is a priority over everything, and the parents’ over-responsibility and additional burden. In the transition to parenthood, a parent may initially feel depressed and anxious due to the loss of the previous role as well as the exhausting fatigue caused by the new role. “The changes were so great that I was shocked and depressed by the time my son was 4 months old” (Participant #6). “I thought the motherhood role was much easier, but I found it is too heavy and I feel the need to study more because the older my child gets, the more different her/his needs become, and I have no experience” (Participant #10). “My wife’s attention is too much on her motherhood role and the child is her priority, and I do not have a good feeling when seeing her focus is all on the child” (Participant #5).

Feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals

This fourth subtheme addressed primary themes, including failure to handle personal affairs; failure to pursue hobbies and hobbies, such as sports, walking, and reading books; resigning due to having children; not devoting time to personal goals, like continuing education; failure to socialize with friends and relatives due to parenting; not allocating time to handle personal affairs, and having less time for rest and entertainment. The study participants stated that it was no longer possible to take care of their personal affairs, interests, and hobbies that used to be part of their plans. “I cannot perform my previous activities, such as walking, studying, and exercising, and I used to work, but now I cannot go to work. We cannot have leisure activities, such as going to the cinema and parks because we are always tired of working and taking care of the child” (Participant #1). “I used work as a journalist in a newspaper, but after my child was born, I decided to spend all my time on taking care of the child” (Participant #15).

Psychological and emotional support from the family and the husband

This subtheme was subdivided into primary themes, such as considerable psychological support of both families; the lack of support from the husband; the lack of support from the husband’s family; the wife’s failure to attend and express affection to her husband, and spiritual and psychological support of families, i.e., important than the material support. The support from the original families of the spouses can help the couples to better overcome this challenging period. “We had difficult times. We were both employed and my wife’s family helped a lot to maintain our status” (Participant #5). “We did not have the support of our family and I did half of the housework and childcare so that my wife would not suffer too much pressure” (Participant #4). “I was living at my mother’s house for two months after my childbirth, but afterward, we did not get help from any of the families” (Participant #12).

Parenting disagreements

This subtheme consisted of such primary themes as, fighting over parenting styles; fighting over physical and verbal punishment of the child, e.g. for not using a diaper; severe criticism of the spouse for the child’s misbehavior; constantly criticizing and accusing each other of improperly raising the child; disagreement over the division of tasks in the home; disputes that adversely affect the parent-child relationship, as well as concerns and disagreement about not controlling the child’s misbehavior in the future. Sometimes, the parents disagreed on how to raise the child, leading to parenting problems. Sometimes, the spouses had disagreements and conflicts with their families. “Our biggest disagreement is over how to raise the child. My husband says I am spoiling the child and I think my husband is too strict” [The wife]. “We even disagree on when to stop using diapers and pacifiers and matters like this” [The husband] (Participant #2). “If there is the smallest problem in raising the child, my husband blames me” [the wife]. “If I frown at my child in the presence of my wife’s parents, I will be quarreled immediately” [the husband] (Participant #5).

Changes in sexual relationships

This subtheme accounted for changes in sexual relations. These alternations were explained by primary themes, such as having inadequate time to have sexual relations; the couple feels very tired due to child care; a decline in the frequency of sexual relations; a decline in sexual relations due to the lack of husband demand; psychological stress induced by the lack of or limited sexual relations; the fading of passion between the spouses; decreased libido and arousal in the couples after childbirth; the child sleeps with the parents and the mother constantly takes care of him/her at night; separating the husband’s bed from his wife’s because of the child; no private time for the couples; feeling very distrustful; cold sexual relations; decreased sexual relations due to waking up at night and caring for the child; insufficient rest, and the husband’s sexual dysfunction due to not having regular sexual intercourse. These changes were highlighted in almost all the interviews by the study participants. “We do not have sexual relations as frequently as before, and this bothers and stresses me. This is because we do not know when the baby goes to sleep and we get tired” (Participant #3). “Our sexual relations were good before and we were satisfied, but now we rarely have such relations; I do not have the sexual desire at all” [the wife]. “It was not a mental problem, but not having sexual intercourse created physical problems for me. This is an essential challenge for me” [the husband] (Participant #6).

Fear of the failure to financially support the child: This subtheme was extended into primary themes, including the lack of financial readiness to have children; decreased income after the child was born; decreased income as the wife had to resign after pregnancy; the uncertainty of the socioeconomic conditions of the country; an uncertain economic future; fear of raising a child in poverty, like their parents; worrying about uncertain national conditions; working more and having multiple jobs due to the financial burden of raising the child; worrying about social conditions of the community, and the desire for migration and raising the child in a more economically stable country. The child’s financial support was also among the major issues highlighted by numerous study participants; it was a crucial concern of families from all walks of life. “After the birth of my child, I became more economically active and my socioeconomic worries make me stressful” (Participant #11). “I think most of our issues are due to financial problems, and if our economic situation was more stable we would be better parents” [the husband] (Participant #7).

Dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes

The last subtheme found in this study was the mothers’ dissatisfaction with their appearance and weight changes. The study subjects complained about excessive obesity after childbirth; feeling bad due to not having physical fitness; changes in body fitness and size after pregnancy, and feelings of physical deformity and unattractiveness. Weight gain and physical changes after childbirth were essential issues for some female participants. “I have gained about 25 kg of weight and I had changed a lot in appearance. I even felt my face was swollen and I did not leave the house for a long time and that made me a little bit depressed” (Participant #2). Figure 1 shows a paradigmatic model of the explored couple’s challenges in the transition to parenthood.

4. Discussion

The present study results suggested that the most serious challenges faced by couples in the transition to parenthood included the following: ambiguity and changes in the spousal role; duality and conflict in the motherhood role; feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals; psychological and emotional support from the family and husband; parenting disagreements; changes in sexual relations; fear of the failure to financially support the child; dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes, and differences in parenting styles. The core theme was the transition to parenthood; from couples to parents.

These findings were in line with those of previous studies. For instance, Twenge et al. (2003) found that fighting over the allocation of household chores and

responsibilities was a major challenge for parents. The female participants in this study were dissatisfied with the gender-based assignment of household chores; they stated that their husbands were less cooperative in household chores. Gender differences at the time of transition to parenthood are considered a crisis. Furthermore, they cause gender-biased perceptions of motherhood and fatherhood that affect the behavior of each parent. Subsequently, they lead to the wife’s fatigue and dissatisfaction. Husbands’ unawareness and unwillingness to participate in childbirth preparation and subsequent programs are among the problems of couples. Therefore, educating couples, providing information and training before childbirth on breastfeeding, child care, and raising awareness on the potential changes in marital relationships are essential (Deave, Johnson & Ingram, 2008; Deave & Johnson, 2008; Baldwin, Malone, Sandall & Bick, 2019). Men experience extensive stress after having a child, including fatigue, poor concentration, and irritability (Darwin et al., 2017). The transition to parenthood represents a significant life event that increases vulnerability to psychological disorders. Postpartum depression and parental anxiety are among the most frequent psychological disorders. Depression, anxiety, and stress after childbirth can be dangerous to a child’s biopsychological health (Epifanio, Genna, De Luca, Roccella & La Grutta, 2015; Pinquart & Teubert, 2010).

Philpott, Savage, Leahy-Warren & FitzGearld (2020) suggested that depression is prevalent in the perinatal period in couples. Factors, such as the father’s age, lower education, unplanned pregnancy, and maternal depression impact the father’s depression (Philpott et al., 2020). Dualities and conflicts of motherhood roles were found as other challenges in this study. Dave et al. (2008) argued that unawareness about parenthood changes in child care as well as relationships with the spouse cause conflicts.

Parenting disagreements were sometimes developed between the husband and wife, and each parent considers it from their perspective. Sometimes, these disagreements occurred between the parents and the grandparents of the child, and most of the time, the couples were too much dependent on their families; there was no restructuring and readjustment with the original families. Numerous couples with this problem stated that they had excessively unplanned and unrestricted relations with the families of origin due to the wife’s employment or proximity of their place of residence to the family of origin (Zartler, Schmidt, Schadler, Rieder & Richter, 2021).

One of the most serious challenges for couples in the transition to parenthood was changes in their sexual relationships. The presence of a child who requires 100% parental support for survival and enduring the day-to-day care of the child often forces the parents to allocate some time to rest. They feel tired due to the tedious work of caring for the baby. Accordingly, the sexual relations of the couples undergo some changes. In addition to fatigue, some male and female participants reported a sharp decrease in sexual desire. A decline in sexual desires in some women was due to childbirth and its complications. Besides, some women attributed this problem to additional responsibility, the burden of child care, and the lack of husband support. In some cases, this problem was due to the feeling of distrust and being suspicious of the husband’s engagement in extramarital affairs. Some male participants stated that they refused to ask for sexual intercourse when they considered their wife’s conditions. Furthermore, some study subjects mentioned that sometimes, they did not even think about having sexual intercourse at all due to their busy schedule. Studies revealed that the transition to parenthood affects couples’ romantic relationships (Alves et al., 2019). However, Doss & Rhoades (2017) found that having children is associated with moments of joy and sorrow. Accordingly, the romantic relationship of spouses goes back to before having children; if they have loved each other before having children, their love would continue after childbearing. Furthermore, couples who experienced higher levels of anxiety encounter further problems (Doss & Rhoades, 2017).

Rosen, Bailey & Muise (2018) also reported that numerous first-time parents are concerned about their level of interest in sexual relationships. The difference in the intensity of sexual desire in couples is crucial. When one party experiences a stronger sexual desire than the other, the couple’s conflicts became much greater. If both spouses had lower desires or similar levels of sexual desire, they reported greater marital satisfaction (Rosen et al., 2018). Tavares, Schlagintweit, Nobre & Rosen (2019) documented that parents’ sexual satisfaction was associated with less stress in their marital life. They also found that positive sexual experiences are associated with a lower perception of stress. Couples’ sexual wellbeing may be important for coping with post-child stress (Tavares et al., 2019).

Lévesque et al. addressed parental outcomes. In a qualitative study and post-content analysis, they identified 3 major challenges during the transition to parenthood, as follows: the loss of meaning of individuality and matrimony, given the original identity as parents; the equality of parental responsibilities and division of labor for child care, and the impact of social norms and beliefs on the development of the concept of parenthood. They stated that challenges, including fatigue and sleep deprivation, social isolation, loneliness, and employment were also accompanied by barriers to adapting to the parenting role (Lévesque et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

The present study data indicated that parenthood can be a positive and a negative experience. The main challenges for couples in the transition to parenthood included ambiguity and changes in the spousal role; duality and conflict in the motherhood role; feeling restricted and prevented from pursuing personal goals; psychological and emotional support from the family and husband; parenting disagreements; changes in sexual relationships; fear of the failure to financially support the child; dissatisfaction with the appearance and weight changes, and differences in parenting styles. Moreover, factors underlying these challenges were the family’s economic conditions; family conditions; the main family’s support; individual characteristics, and the quality of the couple’s previous adjustment; these variables affected the severity and quality of coping with the challenges. The strategies adopted by the couples to manage these challenges were to respond sensibly to this transition; interact and participate in solving the challenges; use family resources, and attempting to improve financial conditions. The consequences of the transition to parenthood fluctuated depending on the characteristics and conditions of the couple from conflict, incompatibility, and dissatisfaction to high satisfaction. Thus, transition to parenthood requires educating and informing spouses; improving marital functioning; balancing individual circumstances; family support, and socioeconomic stability.

This study was conducted with some limitations. First, qualitative research is based on the life experiences and psychological reactions of individuals who have grown up in a specific sociocultural context (Iranian society in this study). Second, this study was conducted in Tehran; thus, its findings, in general, do not reflect the parenthood challenges of the entire population of couples in Iran.

Providing education; holding parenting training courses during pregnancy; fathers participating in courses, and preparing couples for the transition to parenthood are essential measures; these measures can be taken by health professionals, including psychologists and family counselors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was registered at Khatam University (Code: IR.KHATAM.REC.1399.16).

Funding

This research received no grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Alves, S., Milek, A., Bodenmann, G., Fonseca, A., Canavarro, M. C., & Pereira, M. (2019). Romantic attachment, dyadic coping, and parental adjustment across the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships, 26(2), 286-309. [DOI:10.1111/pere.12278]

Baldwin, Sh., Malone, M., Sandall, J., & Bick, D. (2019). A qualitative exploratory study of UK first-time fathers’ experiences, mental health, and wellbeing needs during their transition to fatherhood. BMJ Open, 9(9), e030792. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030792] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brown, A., & Davies, R. (2014). Fathers’ experiences of supporting breastfeeding: Challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10(4), 510-26. [DOI:10.1111/mcn.12129] [PMID] [PMCID]

Claxton, A., & Perry‐Jenkins, M. (2008). No fun anymore: Leisure and marital quality across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 28-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00459.x] [PMID]

Creswell, J. W., & Báez, J. C. (2020). 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com/books?id=AvNRzQEACAAJ&dq

Darwin, Z., Galdas, P., Hinchliff, S., Littlewood, E., McMillan, D., & McGowan, L., et al. (2017). Fathers’ views and experiences of their own mental health during pregnancy and the first postnatal year: A qualitative interview study of men participating in the UK Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 45. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-017-1229-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Davoudi, Z., Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, A., & Falsafinejad, M. R. (2018). [The effectiveness of training of self-help program toward the parenthood on worry in pregnancy period among the nulliparous women (Persian)]. Journal of Health Literacy, 3(1), 61-71. [DOI:10.22038/JHL.2018.10932]

Deave, T., Johnson, D., & Ingram, J. (2008). Transition to parenthood: The needs of parents in pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 8, 30. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-8-30] [PMID]

Deave, T., & Johnson, D. (2008). The transition to parenthood: What does it mean for fathers? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(6), 626-33. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04748.x] [PMID]

Doss, B. D., & Rhoades, G. K. (2017). The transition to parenthood: Impact on couples’ romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 25-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.003] [PMID]

Epifanio, M. S., Genna, V., De Luca, C., Roccella, M., & La Grutta, S. (2015). Paternal and maternal transition to parenthood: The risk of postpartum depression and parenting stress. Pediatric Reports, 7(2), 5872. [DOI:10.4081/pr.2015.5872] [PMID] [PMCID]

Falsafinejad, M. R., Mazinani, H., & Etemadi, A. (2011). [Effects of awareness from developmental family life cycle tasks on student’s marital satisfaction (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Sciences, 9(36), 452-69. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1081053

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-98625-005

Hipp, L. E., Low, L. K., & van Anders, S. M. (2012). Exploring women’s postpartum sexuality: Social, psychological, relational, and birth‐related contextual factors. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(9), 2330-41. [DOI:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02804.x] [PMID]

Karimzadeh, M., Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Davoodi, H., & Heidari, H. (2020). Experiences and worries in mothers with children suffering from ADHD: A Grounded Theory Study. Caspian Journal of Pediatrics, 6(1), 390-8. http://caspianjp.ir/article-1-115-en.html

Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A. (2019). [Family therapy and parent training program & models (Persian)]. Tehran: Jangal Publication. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/1925039

Kohn, J. L., Rholes, S. W., Simpson, J. A., McLeish Martin III, A., Tran, S., & Wilson, C. L. (2012). Changes in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: The role of adult attachment orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(11), 1506-22. [DOI:10.1177/0146167212454548] [PMID]

Lawrence, E., Nylen, K., & Cobb, R. J. (2007). Prenatal expectations and marital satisfaction over the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 155-64. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.155] [PMID]

Lévesque, S., Bisson, V., Charton, L., & Fernet, M. (2020). Parenting and relational well-being during the transition to parenthood: Challenges for first-time parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1938-56. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-020-01727-z]

McGoldrick, M., & Shibusawa, T. (2012). The family life cycle. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (pp. 375–398). New York: The Guilford Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=3C15kY3XnMUC&dq