Volume 9, Issue 3 (Summer 2021)

PCP 2021, 9(3): 165-178 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohammadi M, Ahmadi S M, Naji Mydani F, Jafari M, Reisi S. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale in A Non-clinical Population. PCP 2021; 9 (3) :165-178

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-737-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-737-en.html

Mohammad Mohammadi1

, Seyed Mojtaba Ahmadi2

, Seyed Mojtaba Ahmadi2

, Fatemeh Naji Mydani1

, Fatemeh Naji Mydani1

, Mahdi Jafari *3

, Mahdi Jafari *3

, Sajjad Reisi2

, Sajjad Reisi2

, Seyed Mojtaba Ahmadi2

, Seyed Mojtaba Ahmadi2

, Fatemeh Naji Mydani1

, Fatemeh Naji Mydani1

, Mahdi Jafari *3

, Mahdi Jafari *3

, Sajjad Reisi2

, Sajjad Reisi2

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,drmjafari@sbmu.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS), Obsessive-Compulsive Dsorder (OCD), Psychometric, Validity

Full-Text [PDF 2987 kb]

(1553 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5617 Views)

Full-Text: (2055 Views)

1. Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by unwanted thoughts, images, urges (obsessions), and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions), which may offer some relief for the anxiety caused by obsessive thoughts.

Obsessive-compulsive acts can be time-consuming and significantly disrupt everyday life activities, job performance, routine social activities, and personal relationships. Although these acts may alleviate the anxiety associated with OCD, they do not always reduce stress, and there is a possibility that anxiety remains unchanged or even exacerbates after the act. Anxiety also increases when the person resists obsessive-compulsive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to studies, the 12-month prevalence of the OCD in Iran is 5.1% (Hajebi et al., 2018).

Several tools have been developed to measure the severity of OCD symptoms, such as the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) (Foa et al., 2002), the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS ) (Rosario-Campos et al., 2006), and the Vancouver Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (VOCI) (Thordarson et al., 2004).

Despite the wide range of obsessive-compulsive assessment scales, these scales are time-consuming and do not accurately assess the severity of the obsessive-compulsive disorder. In addition, many existing scales (such as VOCI) focus only on the severity of the symptoms and do not consider the extent of the symptoms. Another weakness mentioned in the existing scales is the separation of obsession from compulsion in these scales, while the structural analysis results show that OCD pathology is not regularly divided into obsession and compulsion. Another limitation that can be noted in the scales (such as OCI-R, Y-BOCS) is the lack of assessment of OCD, which may underestimate the severity of symptoms in this disorder. Finally, “hoarding” is also evaluated on many existing scales that are inconsistent with most up-to-date structural framework of OCD symptoms (Abramowitz et al., 2010).

The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS) is a 20-item self-report scale, which lacks the mentioned limitations. This questionnaire was developed by Abramowitz et al. (2010) to measure various dimensions of OCD in clinical and non-clinical samples. This scale assesses four OCD symptom dimensions: 1) contamination; 2) responsibility for harm/injury 3) unacceptable thoughts; and 4) symmetry, completeness, and accuracy. DOCS shows high validity and reliability with the Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.90 to 0.93 in clinical and non-clinical samples, respectively. Also, its dimensions have been determined through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (Abramowitz et al., 2010). Psychometric properties of this instrument were calculated in different countries such as Sweden (Enander et al., 2012), Iceland (Ólafsson et al., 2013), Spain (López-Solà et al., 2014), and Mexico (Treviño-de la Garza, Berman, Fisak, Ruvalcaba-Romero, & Gallegos-Guajardo, 2019). These studies confirmed the appropriate validity and reliability of this instrument.

Jesper Enander et al. (2012) investigated the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of DOCS (which was implemented online) and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients for its dimensions: contamination, 0.96; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.93; unwanted thoughts, 0.96; and symmetry, 0.94. Also, the Cronbach α for the total score was reported to be 0.87. The 4-factor structure was supported by confirmatory factor analysis, and DOCS also showed good convergent and discriminant validities.

Lafsson et al. in 2013 investigated psychometric properties of the Icelandic version of DOCS on university students and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients for each dimension: contamination, 0.75; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.84; unacceptable thoughts, 0.86; symmetry, 0.86 and total score, 0.91. The 4-factor structure was supported by confirmatory factor analysis. Moderate to strong correlations of DOCS with the OCI-R and the Y-BOCS-self report version indicated convergent validities.

In 2014, Clara López-Solà investigated the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of DOCS non-clinical sample and in adult patients with OCD and reported the Cronbach α values of 0.80, 0.86, 0.87, and 0.88 for contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively. Also, the Cronbach α for the total score was reported to be 0.93, and the DOCS showed good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity in both samples.

de la Garza in 2019 investigated the psychometric properties of the DOCS on the Mexican population (the majority of whom were college students). Confirmatory factor analysis supported the 4-factor structure. The subscale and total scores showed good internal consistency. Significant positive correlations with the obsessive beliefs questionnaire short version and the interpretations of intrusions inventory indicated convergent validity.

Given the above and the fact that many people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms are not hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals and clinical centers, many patients may not be aware of the symptoms of their diseases for a long time. Therefore, to monitor non-clinical population with symptoms of obsessive-compulsive who refer to mental health-related centers, we should use a valid and reliable scale to diagnose them. The present study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of DOCS in non-clinical Iranian samples. We intended to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants and procedures

In this study, 252 individuals from different Tehran districts, Iran, were selected via cluster sampling method. First, Tehran districts were divided into nine regions (north, northeast, northwest, western central, east, south, southeast, and southwest). Then the health centers were randomly selected from each region. The samples were selected among the patients’ companions via convenient sampling method. After explaining the study's design and obtaining consent from the samples, DOCS, Y-BOCS, and OCI-R were completed for the samples.

Translation

For translation and cultural adaptation of the questionnaire, the minimal translation criteria were used (Trust, 1997). First, the original questionnaire was translated into Persian by two Persian-speaking translators (PhD in clinical psychology) fluent in English. The two versions of the questionnaire were compared by an assessor (PhD in clinical psychology). After revisions, a PhD student of clinical psychology, who was fluent in Persian and English, was asked to back-translate the Persian translation into English. Finally, the back-translated version was compared with the original questionnaire, and no problem was found in the back-translated version.

Study measurements

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R)

OCI-R is the short-form of the original OCI, developed by Foa et al. in 1998 and revised as a short form in 2002. It is an 18-item tool, which assesses six dimensions of OCD symptoms (washing, obsessive thinking, hoarding, ordering, checking, and neutralizing) (Foa et al., 2002). This test has high internal consistency. As reported by Foa et al., its Cronbach α for clinical and non-clinical samples ranges between 0.81 and 0.93; similar coefficients have also been reported by other researchers (Abramowitz & Deacon, 2006). Also, OCI-R shows good construct validity. The study by Foa et al., as well as subsequent validation studies, supports the six dimensions of the scale according to exploratory factor analysis in samples of patients with OCD, general phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Huppert et al., 2007). This questionnaire was validated by Qasemzadeh et al. (2011) in Iran (the Cronbach α, 0.85). Since this questionnaire’s validity has been confirmed in Iran, it can be used as a measure to determine DOCS validity.

Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS)

In 2010, Abramowitz et al. developed this questionnaire to measure various dimensions of OCD in clinical and non-clinical samples. This scale assesses four OCD symptom dimensions: a) contamination (contamination and disinfection obsessions and cleaning compulsions); b) responsibility for harm/injury or bad luck (obsessions about causing harm in different ways, checking compulsions, and related compulsions); c) unacceptable thoughts (obsessions about sex, violence, and religion and compulsions for neutralizing); and d) symmetry, completeness, and accuracy (obsessions about things that are not in the ‘right place’ and compulsions, including ordering and repetition). DOCS also measures the severity of OCD symptoms with a multidimensional approach, based on five major criteria for each dimension: 1) time occupied by obsessions and compulsions, 2) avoidance behavior, 3) distress, 4) functional interference, and 5) difficulty ignoring obsessive and compulsive thoughts.

Abramowitz et al. (2010) reported excellent internal consistency in previous validation studies on large samples of patients with OCD, patients with other anxiety disorders, and students. The Cronbach α values for the total scale and subscales in clinical and non-clinical samples ranged from 0.83 to 0.96. Besides, Abramowitz et al. (2010) confirmed the scale dimensions and common patterns of OCD based on exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on independent clinical and non-clinical samples.

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

In 1989, Goodman et al. developed the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale. Y-BOCS is one of the most widely used tools in measuring the intensity of OCD. This questionnaire assesses the severity of obsession with 10 questions: 5 are related to obsession and 5 to compulsion. In questions related to obsession and compulsion, items such as time, interference, distress, resistance, and control are evaluated. The total score of this questionnaire ranges from 0 to 40, and each question is graded on a 5-point Likert scale. The results of studies show that this scale has acceptable validity and reliability (Eilertsen et al., 2017).

Statistical analysis

SPSS-21 and LISREL statistical software were used for data analysis. To evaluate the internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha method and to evaluate the Convergent validity among DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R, Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used. Also, in order to evaluate the structural validity, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis methods were used.

Ethical considerations

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1397.595). Individuals with OCD or symptoms of OCD in the clinical interview were referred to a center affiliated to the University of Medical Sciences after coordination with the Psychiatry or Psychology Department of Shahid Beheshti Hospital.

3. Results

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 27.34±11.89 years. The age distribution of the participants showed that 39.70% were between 20 and 25 years, 30.60% between 26 and 30 years, 13.10% between 31 and 35 years, and 16.60% above 36 years. Overall, 55.55% of the samples were female, 15.51% had a high school diploma or lower, 11.49% had higher than high school diploma, 29.80% had a bachelor’s degree, and 43.20% had a Master’s or Doctorate. Twenty (7.93%) cases were diagnosed with OCD.

Reliability and item analysis

Based on the Cronbach α, the internal consistency of DOCS was 0.916, and the correlation between the total score and score of each item ranged from 0.54 to 0.73 (P<0.001). Also, the results of Cronbach α showed that the removal of each item would decrease the Cronbach α coefficient. Based on the Cronbach α calculations, the internal consistency values were 0.82, 0.83, 0.82, and 0.87 for the contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively.

Validity

The correlations of DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R were 0.57 and 0.55, respectively (P<0.001). The correlations of these questionnaires with the total score and subscales of DOCS were also evaluated in this study (Table 1).

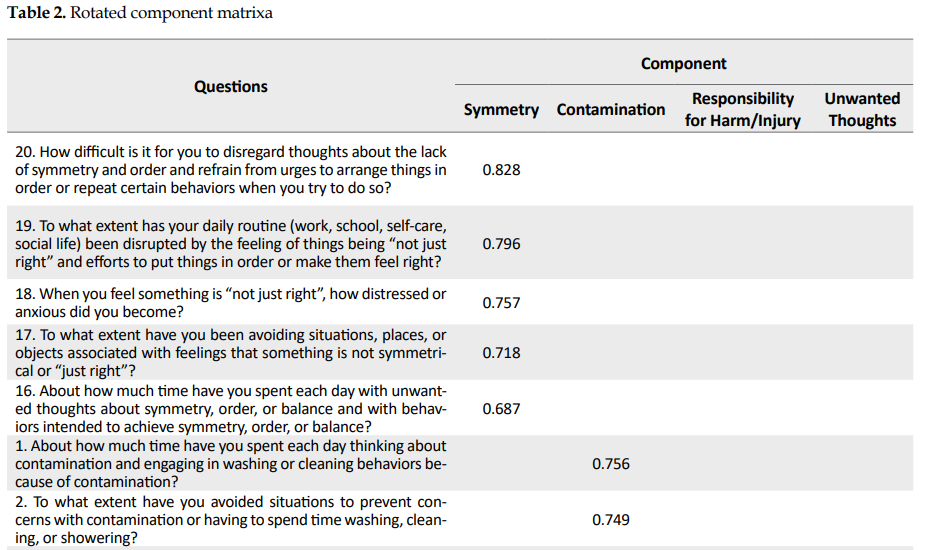

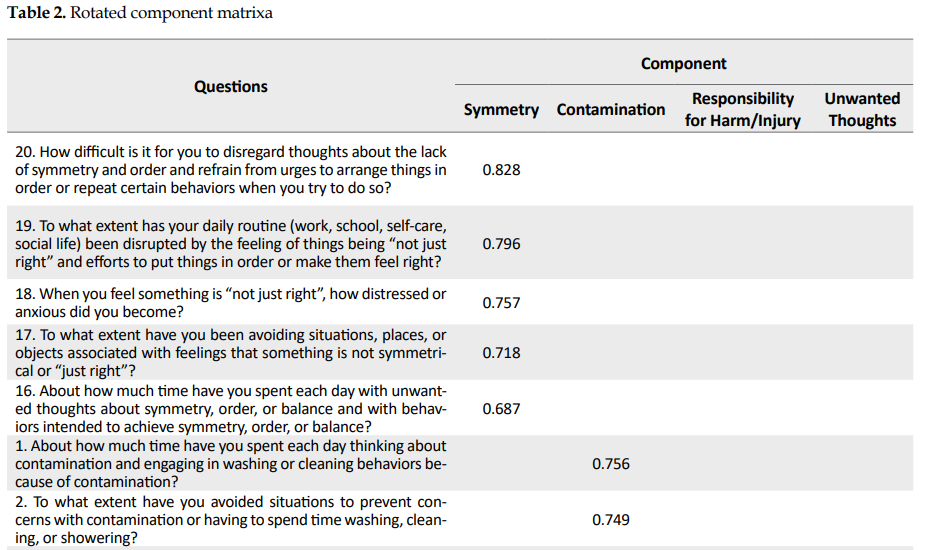

Construct validity (factor analysis)

Exploratory factor analysis was used to evaluate the construct validity of the questionnaire. The Kaplan-Meier-Olkin test result was 0.88. Also, the result of Bartlett’s test was significant (P<0.001), indicating the suitability of data for factor analysis. The factor analysis showed 4 factors with eigenvalues of 7.84 (symmetry), 1.93 (contamination), 1.48 (responsibility for harm/injury), and 1.13 (unwanted thoughts), which explained 61.99% of the total variance. The factor loadings ranged from 0.57 to 0.82. (Table 2).

.PNG)

.PNG)

Confirmatory factor analysis

LISREL was used for confirmatory factor analysis of the structural model. The results of exploratory factor analysis in the previous step and the results of factor analysis in previous studies were investigated. Since a single, 4-factor structure, and higher-order factor model were introduced in previous research, we investigated these structures (López-Solà et al., 2014; Ólafsson et al., 2013). The results showed that the higher-order factor model and the 4-factor model have a better fit than the single factor model (Table 3) (Figure1 and Figure 2).

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population. The results showed the acceptable validity and reliability of this scale. Based on Cronbach’s alpha, the internal consistency of DOCS was 0.916, and Cronbach’s alpha for the contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, Unacceptable Thoughts, and Symmetry was 0.82, 0.83, 0.82, and 0.87, respectively.

The present findings are consistent with the results reported by Clara López-Solà (2014) from Spain. They reported the Cronbach α values of 0.80, 0.86, 0.87, and 0.88 for contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively. Also, the Cronbach α value for the total score was reported 0.93. Ólafsson et al. (2013) investigated psychometric properties of the Icelandic version with the following Cronbach α coefficients for each dimension: contamination, 0.75; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.84; unacceptable thoughts, 0.86; symmetry, 0.86 and total score, 0.91.

Consistent with the present study, Jesper Enander et al. (2012) investigated the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of DOCS (implemented online) and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients: contamination, 0.96; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.93; unwanted thoughts, 0.96; and symmetry, 0.94. Also, the Cronbach α value for the total score was reported 0.87. According to Nanali and Bernstein, the Cronbach α above 0.70 is acceptable (Pompili et al., 2020). The correlations of DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R were 0.57 and 0.55, respectively, demonstrating the validity of this questionnaire; this finding is in line with the study by Ólafsson et al. (2013).

Moreover, in the present study, four factors were extracted using exploratory factor analysis, and the good fit of the model was confirmed in the confirmatory factor analysis. Ólafsson et al. (2013) and Clara López-Solà et al. (2014) extracted four factors in their studies. The factors reported in our study are consistent with those of previous studies; in other words, our categorization is similar to previous studies. These similar factors are contamination, responsibility for harm, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry. Also, we found that the higher-order factor model had a more appropriate fit. Moreover, this finding was in line with Ólafsson et al. (2013) and Abramowitz et al. (2010).

To explain the present study’s findings, it can be said that people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms tend to hide their symptoms and do not seek appropriate and timely interventions and treatments. Besides, the long time that people have obsessive-compulsive symptoms and overlooking the treatment are the most important and severe factors in mental disorders (Altamura, Buoli, Albano, & Dell’Osso, 2010). Also, most adults with obsessive-compulsive symptoms seek effective psychological services about 10 years after the first symptoms appear (García-Soriano, Rufer, Delsignore, & Weidt, 2014). Based on previous research, obsessive-compulsive symptoms are crucial factors that require timely diagnosis and treatment intervention (Belloch, Del Valle, Morillo, Carrió, & Cabedo, 2009). Our results show that DOCS could be effective in the early detection of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the non-clinical population in Iran.

Some limitations of the present study are as follows:

First, the study sample included the general population of Tehran, so care should be taken in generalizing the results to other populations.

Second, divergence validity and cut-off point were not examined. we suggested that these factors be examined in future studies.

Third, in most previous studies, the clinical samples were also examined. So it is suggested that in future studies, the psychometric properties of this questionnaire be examined in a clinical sample in Iran.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population. The results show that DOCS has appropriate and acceptable validity and reliability in the non-clinical population of Iran. Therefore, it is suggested that this scale be used to screen people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in non-clinical centers related to mental health assessment.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1397.595).

Funding

This research was supported by the research project (No. 13968), Funded by the University of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for their sincere cooperation.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., & Deacon, B. J. (2006). Psychometric properties and construct validity of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised: Replication and extension with a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(8), 1016-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.001] [PMID]

Abramowitz, J. S., Deacon, B. J., Olatunji, B. O., Wheaton, M. G., Berman, N. C., Losardo, D., et al. (2010). Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: Development and evaluation of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychological Assessment, 22(1), 180-98. [DOI:10.1037/a0018260] [PMID]

Altamura, A. C., Buoli, M., Albano, A., & Dell’Osso, B. (2010). Age at onset and latency to treatment (duration of untreated illness) in patients with mood and anxiety disorders: A naturalistic study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(3), 172-9. [DOI:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283384c74] [PMID]

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Pub. https://books.google.com/books?id=-JivBAAAQBAJ&dq

Belloch, A., Del Valle, G., Morillo, C., Carrió, C., & Cabedo, E. (2009). To seek advice or not to seek advice about the problem: The help-seeking dilemma for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(4), 257-64. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-008-0423-0] [PMID]

Eilertsen, T., Hansen, B., Kvale, G., Abramowitz, J. S., Holm, S. E. H., & Solem, S. (2017). The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Form (DOCS-SF). Frontiers in Psychology, 8, p. 1503. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01503] [PMID] [PMCID]

Enander, J., Andersson, E., Kaldo, V., Lindefors, N., Andersson, G., & Rück, C. (2012). Internet administration of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale: A psychometric evaluation. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 1(4), 325-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2012.07.008]

Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Leiberg, S., Langner, R., Kichic, R., Hajcak, G., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14(4), 485-96. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485] [PMID]

García-Soriano, G., Rufer, M., Delsignore, A., & Weidt, S. (2014). Factors associated with non-treatment or delayed treatment seeking in OCD sufferers: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 1-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.009] [PMID]

Ghassemzadeh, H., Shams, G., Abedi, J., Karamghadiri, N., Ebrahimkhani, N., & Rajabloo, M. (2011). Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the obsessive-compulsive inventory-revised: OCI-R-Persian. Psychology, 2(3), 210-5. [DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.23032]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., et al. (1989). The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-11. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007] [PMID]

Hajebi, A., Motevalian, S. A., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., Sharifi, V., Amin-Esmaeili, M., & Radgoodarzi, R., et al. (2018). Major anxiety disorders in Iran: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and service utilization. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 261. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1828-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

Huppert, J. D., Walther, M. R., Hajcak, G., Yadin, E., Foa, E. B., & Simpson, H. B., et al. (2007). The OCI-R: Validation of the subscales in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(3), 394-406. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.05.006] [PMID]

López-Solà, C., Gutiérrez, F., Alonso, P., Rosado, S., Taberner, J., Segalàs, C., et al. (2014). Spanish version of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS): Psychometric properties and relation to obsessive beliefs. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(1), 206-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.015] [PMID]

Ólafsson, R. P., Arngrímsson, J. B., Árnason, P., Kolbeinsson, Þ., Emmelkamp, P. M., & Kristjánsson, Á., et al. (2013). The Icelandic version of the Dimensional Obsessive Compulsive Scale (DOCS) and its relationship with obsessive beliefs. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 2(2), 149-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.02.001]

Pompili, C., Holch, P., Rogers, Z., Absolom, K., Clayton, B., Franks, K., et al. (2020). Patients’ confidence in treatment decisions for early stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). [DOI:10.21203/rs.2.21587/v1]

Rosario-Campos, M., Miguel, E., Quatrano, S., Chacon, P., Ferrao, Y., & Findley, D., et al. (2006). The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS ): An instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry, 11(5), 495-504. [DOI:10.1038/sj.mp.4001798] [PMID]

Thordarson, D. S., Radomsky, A. S., Rachman, S., Shafran, R., Sawchuk, C. N., & Hakstian, A. R. (2004). The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(11), 1289-314. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.007] [PMID]

Treviño-de la Garza, B., Berman, N., Fisak, B., Ruvalcaba-Romero, N., & Gallegos-Guajardo, J. (2019). Validation of The Dimensional Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale for Mexican population. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 21, 13-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2018.11.006]

Trust, M. (1997). Trust introduces new translation criteria. Medical Outcomes Trust Bulletin, 5(4), 3-4. http://www.outcomes-trust.org/bulletin/0797blltn.htm

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by unwanted thoughts, images, urges (obsessions), and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions), which may offer some relief for the anxiety caused by obsessive thoughts.

Obsessive-compulsive acts can be time-consuming and significantly disrupt everyday life activities, job performance, routine social activities, and personal relationships. Although these acts may alleviate the anxiety associated with OCD, they do not always reduce stress, and there is a possibility that anxiety remains unchanged or even exacerbates after the act. Anxiety also increases when the person resists obsessive-compulsive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to studies, the 12-month prevalence of the OCD in Iran is 5.1% (Hajebi et al., 2018).

Several tools have been developed to measure the severity of OCD symptoms, such as the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) (Foa et al., 2002), the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS ) (Rosario-Campos et al., 2006), and the Vancouver Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (VOCI) (Thordarson et al., 2004).

Despite the wide range of obsessive-compulsive assessment scales, these scales are time-consuming and do not accurately assess the severity of the obsessive-compulsive disorder. In addition, many existing scales (such as VOCI) focus only on the severity of the symptoms and do not consider the extent of the symptoms. Another weakness mentioned in the existing scales is the separation of obsession from compulsion in these scales, while the structural analysis results show that OCD pathology is not regularly divided into obsession and compulsion. Another limitation that can be noted in the scales (such as OCI-R, Y-BOCS) is the lack of assessment of OCD, which may underestimate the severity of symptoms in this disorder. Finally, “hoarding” is also evaluated on many existing scales that are inconsistent with most up-to-date structural framework of OCD symptoms (Abramowitz et al., 2010).

The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS) is a 20-item self-report scale, which lacks the mentioned limitations. This questionnaire was developed by Abramowitz et al. (2010) to measure various dimensions of OCD in clinical and non-clinical samples. This scale assesses four OCD symptom dimensions: 1) contamination; 2) responsibility for harm/injury 3) unacceptable thoughts; and 4) symmetry, completeness, and accuracy. DOCS shows high validity and reliability with the Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.90 to 0.93 in clinical and non-clinical samples, respectively. Also, its dimensions have been determined through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (Abramowitz et al., 2010). Psychometric properties of this instrument were calculated in different countries such as Sweden (Enander et al., 2012), Iceland (Ólafsson et al., 2013), Spain (López-Solà et al., 2014), and Mexico (Treviño-de la Garza, Berman, Fisak, Ruvalcaba-Romero, & Gallegos-Guajardo, 2019). These studies confirmed the appropriate validity and reliability of this instrument.

Jesper Enander et al. (2012) investigated the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of DOCS (which was implemented online) and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients for its dimensions: contamination, 0.96; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.93; unwanted thoughts, 0.96; and symmetry, 0.94. Also, the Cronbach α for the total score was reported to be 0.87. The 4-factor structure was supported by confirmatory factor analysis, and DOCS also showed good convergent and discriminant validities.

Lafsson et al. in 2013 investigated psychometric properties of the Icelandic version of DOCS on university students and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients for each dimension: contamination, 0.75; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.84; unacceptable thoughts, 0.86; symmetry, 0.86 and total score, 0.91. The 4-factor structure was supported by confirmatory factor analysis. Moderate to strong correlations of DOCS with the OCI-R and the Y-BOCS-self report version indicated convergent validities.

In 2014, Clara López-Solà investigated the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of DOCS non-clinical sample and in adult patients with OCD and reported the Cronbach α values of 0.80, 0.86, 0.87, and 0.88 for contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively. Also, the Cronbach α for the total score was reported to be 0.93, and the DOCS showed good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity in both samples.

de la Garza in 2019 investigated the psychometric properties of the DOCS on the Mexican population (the majority of whom were college students). Confirmatory factor analysis supported the 4-factor structure. The subscale and total scores showed good internal consistency. Significant positive correlations with the obsessive beliefs questionnaire short version and the interpretations of intrusions inventory indicated convergent validity.

Given the above and the fact that many people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms are not hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals and clinical centers, many patients may not be aware of the symptoms of their diseases for a long time. Therefore, to monitor non-clinical population with symptoms of obsessive-compulsive who refer to mental health-related centers, we should use a valid and reliable scale to diagnose them. The present study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of DOCS in non-clinical Iranian samples. We intended to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants and procedures

In this study, 252 individuals from different Tehran districts, Iran, were selected via cluster sampling method. First, Tehran districts were divided into nine regions (north, northeast, northwest, western central, east, south, southeast, and southwest). Then the health centers were randomly selected from each region. The samples were selected among the patients’ companions via convenient sampling method. After explaining the study's design and obtaining consent from the samples, DOCS, Y-BOCS, and OCI-R were completed for the samples.

Translation

For translation and cultural adaptation of the questionnaire, the minimal translation criteria were used (Trust, 1997). First, the original questionnaire was translated into Persian by two Persian-speaking translators (PhD in clinical psychology) fluent in English. The two versions of the questionnaire were compared by an assessor (PhD in clinical psychology). After revisions, a PhD student of clinical psychology, who was fluent in Persian and English, was asked to back-translate the Persian translation into English. Finally, the back-translated version was compared with the original questionnaire, and no problem was found in the back-translated version.

Study measurements

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R)

OCI-R is the short-form of the original OCI, developed by Foa et al. in 1998 and revised as a short form in 2002. It is an 18-item tool, which assesses six dimensions of OCD symptoms (washing, obsessive thinking, hoarding, ordering, checking, and neutralizing) (Foa et al., 2002). This test has high internal consistency. As reported by Foa et al., its Cronbach α for clinical and non-clinical samples ranges between 0.81 and 0.93; similar coefficients have also been reported by other researchers (Abramowitz & Deacon, 2006). Also, OCI-R shows good construct validity. The study by Foa et al., as well as subsequent validation studies, supports the six dimensions of the scale according to exploratory factor analysis in samples of patients with OCD, general phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Huppert et al., 2007). This questionnaire was validated by Qasemzadeh et al. (2011) in Iran (the Cronbach α, 0.85). Since this questionnaire’s validity has been confirmed in Iran, it can be used as a measure to determine DOCS validity.

Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS)

In 2010, Abramowitz et al. developed this questionnaire to measure various dimensions of OCD in clinical and non-clinical samples. This scale assesses four OCD symptom dimensions: a) contamination (contamination and disinfection obsessions and cleaning compulsions); b) responsibility for harm/injury or bad luck (obsessions about causing harm in different ways, checking compulsions, and related compulsions); c) unacceptable thoughts (obsessions about sex, violence, and religion and compulsions for neutralizing); and d) symmetry, completeness, and accuracy (obsessions about things that are not in the ‘right place’ and compulsions, including ordering and repetition). DOCS also measures the severity of OCD symptoms with a multidimensional approach, based on five major criteria for each dimension: 1) time occupied by obsessions and compulsions, 2) avoidance behavior, 3) distress, 4) functional interference, and 5) difficulty ignoring obsessive and compulsive thoughts.

Abramowitz et al. (2010) reported excellent internal consistency in previous validation studies on large samples of patients with OCD, patients with other anxiety disorders, and students. The Cronbach α values for the total scale and subscales in clinical and non-clinical samples ranged from 0.83 to 0.96. Besides, Abramowitz et al. (2010) confirmed the scale dimensions and common patterns of OCD based on exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on independent clinical and non-clinical samples.

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

In 1989, Goodman et al. developed the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale. Y-BOCS is one of the most widely used tools in measuring the intensity of OCD. This questionnaire assesses the severity of obsession with 10 questions: 5 are related to obsession and 5 to compulsion. In questions related to obsession and compulsion, items such as time, interference, distress, resistance, and control are evaluated. The total score of this questionnaire ranges from 0 to 40, and each question is graded on a 5-point Likert scale. The results of studies show that this scale has acceptable validity and reliability (Eilertsen et al., 2017).

Statistical analysis

SPSS-21 and LISREL statistical software were used for data analysis. To evaluate the internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha method and to evaluate the Convergent validity among DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R, Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used. Also, in order to evaluate the structural validity, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis methods were used.

Ethical considerations

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1397.595). Individuals with OCD or symptoms of OCD in the clinical interview were referred to a center affiliated to the University of Medical Sciences after coordination with the Psychiatry or Psychology Department of Shahid Beheshti Hospital.

3. Results

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 27.34±11.89 years. The age distribution of the participants showed that 39.70% were between 20 and 25 years, 30.60% between 26 and 30 years, 13.10% between 31 and 35 years, and 16.60% above 36 years. Overall, 55.55% of the samples were female, 15.51% had a high school diploma or lower, 11.49% had higher than high school diploma, 29.80% had a bachelor’s degree, and 43.20% had a Master’s or Doctorate. Twenty (7.93%) cases were diagnosed with OCD.

Reliability and item analysis

Based on the Cronbach α, the internal consistency of DOCS was 0.916, and the correlation between the total score and score of each item ranged from 0.54 to 0.73 (P<0.001). Also, the results of Cronbach α showed that the removal of each item would decrease the Cronbach α coefficient. Based on the Cronbach α calculations, the internal consistency values were 0.82, 0.83, 0.82, and 0.87 for the contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively.

Validity

The correlations of DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R were 0.57 and 0.55, respectively (P<0.001). The correlations of these questionnaires with the total score and subscales of DOCS were also evaluated in this study (Table 1).

Construct validity (factor analysis)

Exploratory factor analysis was used to evaluate the construct validity of the questionnaire. The Kaplan-Meier-Olkin test result was 0.88. Also, the result of Bartlett’s test was significant (P<0.001), indicating the suitability of data for factor analysis. The factor analysis showed 4 factors with eigenvalues of 7.84 (symmetry), 1.93 (contamination), 1.48 (responsibility for harm/injury), and 1.13 (unwanted thoughts), which explained 61.99% of the total variance. The factor loadings ranged from 0.57 to 0.82. (Table 2).

.PNG)

.PNG)

Confirmatory factor analysis

LISREL was used for confirmatory factor analysis of the structural model. The results of exploratory factor analysis in the previous step and the results of factor analysis in previous studies were investigated. Since a single, 4-factor structure, and higher-order factor model were introduced in previous research, we investigated these structures (López-Solà et al., 2014; Ólafsson et al., 2013). The results showed that the higher-order factor model and the 4-factor model have a better fit than the single factor model (Table 3) (Figure1 and Figure 2).

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population. The results showed the acceptable validity and reliability of this scale. Based on Cronbach’s alpha, the internal consistency of DOCS was 0.916, and Cronbach’s alpha for the contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, Unacceptable Thoughts, and Symmetry was 0.82, 0.83, 0.82, and 0.87, respectively.

The present findings are consistent with the results reported by Clara López-Solà (2014) from Spain. They reported the Cronbach α values of 0.80, 0.86, 0.87, and 0.88 for contamination, responsibility for harm/injury, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry, respectively. Also, the Cronbach α value for the total score was reported 0.93. Ólafsson et al. (2013) investigated psychometric properties of the Icelandic version with the following Cronbach α coefficients for each dimension: contamination, 0.75; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.84; unacceptable thoughts, 0.86; symmetry, 0.86 and total score, 0.91.

Consistent with the present study, Jesper Enander et al. (2012) investigated the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of DOCS (implemented online) and reported the following Cronbach α coefficients: contamination, 0.96; responsibility for harm/injury, 0.93; unwanted thoughts, 0.96; and symmetry, 0.94. Also, the Cronbach α value for the total score was reported 0.87. According to Nanali and Bernstein, the Cronbach α above 0.70 is acceptable (Pompili et al., 2020). The correlations of DOCS with Y-BOCS and OCI-R were 0.57 and 0.55, respectively, demonstrating the validity of this questionnaire; this finding is in line with the study by Ólafsson et al. (2013).

Moreover, in the present study, four factors were extracted using exploratory factor analysis, and the good fit of the model was confirmed in the confirmatory factor analysis. Ólafsson et al. (2013) and Clara López-Solà et al. (2014) extracted four factors in their studies. The factors reported in our study are consistent with those of previous studies; in other words, our categorization is similar to previous studies. These similar factors are contamination, responsibility for harm, unwanted thoughts, and symmetry. Also, we found that the higher-order factor model had a more appropriate fit. Moreover, this finding was in line with Ólafsson et al. (2013) and Abramowitz et al. (2010).

To explain the present study’s findings, it can be said that people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms tend to hide their symptoms and do not seek appropriate and timely interventions and treatments. Besides, the long time that people have obsessive-compulsive symptoms and overlooking the treatment are the most important and severe factors in mental disorders (Altamura, Buoli, Albano, & Dell’Osso, 2010). Also, most adults with obsessive-compulsive symptoms seek effective psychological services about 10 years after the first symptoms appear (García-Soriano, Rufer, Delsignore, & Weidt, 2014). Based on previous research, obsessive-compulsive symptoms are crucial factors that require timely diagnosis and treatment intervention (Belloch, Del Valle, Morillo, Carrió, & Cabedo, 2009). Our results show that DOCS could be effective in the early detection of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the non-clinical population in Iran.

Some limitations of the present study are as follows:

First, the study sample included the general population of Tehran, so care should be taken in generalizing the results to other populations.

Second, divergence validity and cut-off point were not examined. we suggested that these factors be examined in future studies.

Third, in most previous studies, the clinical samples were also examined. So it is suggested that in future studies, the psychometric properties of this questionnaire be examined in a clinical sample in Iran.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale in a non-clinical population. The results show that DOCS has appropriate and acceptable validity and reliability in the non-clinical population of Iran. Therefore, it is suggested that this scale be used to screen people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in non-clinical centers related to mental health assessment.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1397.595).

Funding

This research was supported by the research project (No. 13968), Funded by the University of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for their sincere cooperation.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., & Deacon, B. J. (2006). Psychometric properties and construct validity of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised: Replication and extension with a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(8), 1016-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.001] [PMID]

Abramowitz, J. S., Deacon, B. J., Olatunji, B. O., Wheaton, M. G., Berman, N. C., Losardo, D., et al. (2010). Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: Development and evaluation of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychological Assessment, 22(1), 180-98. [DOI:10.1037/a0018260] [PMID]

Altamura, A. C., Buoli, M., Albano, A., & Dell’Osso, B. (2010). Age at onset and latency to treatment (duration of untreated illness) in patients with mood and anxiety disorders: A naturalistic study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(3), 172-9. [DOI:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283384c74] [PMID]

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Pub. https://books.google.com/books?id=-JivBAAAQBAJ&dq

Belloch, A., Del Valle, G., Morillo, C., Carrió, C., & Cabedo, E. (2009). To seek advice or not to seek advice about the problem: The help-seeking dilemma for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(4), 257-64. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-008-0423-0] [PMID]

Eilertsen, T., Hansen, B., Kvale, G., Abramowitz, J. S., Holm, S. E. H., & Solem, S. (2017). The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Form (DOCS-SF). Frontiers in Psychology, 8, p. 1503. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01503] [PMID] [PMCID]

Enander, J., Andersson, E., Kaldo, V., Lindefors, N., Andersson, G., & Rück, C. (2012). Internet administration of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale: A psychometric evaluation. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 1(4), 325-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2012.07.008]

Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Leiberg, S., Langner, R., Kichic, R., Hajcak, G., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14(4), 485-96. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485] [PMID]

García-Soriano, G., Rufer, M., Delsignore, A., & Weidt, S. (2014). Factors associated with non-treatment or delayed treatment seeking in OCD sufferers: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 1-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.009] [PMID]

Ghassemzadeh, H., Shams, G., Abedi, J., Karamghadiri, N., Ebrahimkhani, N., & Rajabloo, M. (2011). Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the obsessive-compulsive inventory-revised: OCI-R-Persian. Psychology, 2(3), 210-5. [DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.23032]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., et al. (1989). The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-11. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007] [PMID]

Hajebi, A., Motevalian, S. A., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., Sharifi, V., Amin-Esmaeili, M., & Radgoodarzi, R., et al. (2018). Major anxiety disorders in Iran: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and service utilization. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 261. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1828-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

Huppert, J. D., Walther, M. R., Hajcak, G., Yadin, E., Foa, E. B., & Simpson, H. B., et al. (2007). The OCI-R: Validation of the subscales in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(3), 394-406. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.05.006] [PMID]

López-Solà, C., Gutiérrez, F., Alonso, P., Rosado, S., Taberner, J., Segalàs, C., et al. (2014). Spanish version of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS): Psychometric properties and relation to obsessive beliefs. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(1), 206-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.015] [PMID]

Ólafsson, R. P., Arngrímsson, J. B., Árnason, P., Kolbeinsson, Þ., Emmelkamp, P. M., & Kristjánsson, Á., et al. (2013). The Icelandic version of the Dimensional Obsessive Compulsive Scale (DOCS) and its relationship with obsessive beliefs. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 2(2), 149-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.02.001]

Pompili, C., Holch, P., Rogers, Z., Absolom, K., Clayton, B., Franks, K., et al. (2020). Patients’ confidence in treatment decisions for early stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). [DOI:10.21203/rs.2.21587/v1]

Rosario-Campos, M., Miguel, E., Quatrano, S., Chacon, P., Ferrao, Y., & Findley, D., et al. (2006). The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS ): An instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry, 11(5), 495-504. [DOI:10.1038/sj.mp.4001798] [PMID]

Thordarson, D. S., Radomsky, A. S., Rachman, S., Shafran, R., Sawchuk, C. N., & Hakstian, A. R. (2004). The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(11), 1289-314. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.007] [PMID]

Treviño-de la Garza, B., Berman, N., Fisak, B., Ruvalcaba-Romero, N., & Gallegos-Guajardo, J. (2019). Validation of The Dimensional Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale for Mexican population. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 21, 13-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2018.11.006]

Trust, M. (1997). Trust introduces new translation criteria. Medical Outcomes Trust Bulletin, 5(4), 3-4. http://www.outcomes-trust.org/bulletin/0797blltn.htm

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Psychometric

Received: 2021/01/8 | Accepted: 2021/08/7 | Published: 2021/07/19

Received: 2021/01/8 | Accepted: 2021/08/7 | Published: 2021/07/19

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |