Volume 8, Issue 3 (Summer 2020)

PCP 2020, 8(3): 217-232 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Chizari H, Shooshtari S, Duncan K, Menec V. Examining the Effects of Participation in Leisure and Social Activities on General Health and Life Satisfaction of Older Canadian Adults With Disability. PCP 2020; 8 (3) :217-232

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-714-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-714-en.html

1- Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. , h_chizzari1988@yahoo.ca

2- Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

2- Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Keywords: Aging, Disabled persons, Social participation, Health, Personal satisfaction, National center for health statistics

Full-Text [PDF 755 kb]

(1695 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4080 Views)

Full-Text: (1882 Views)

1. Introduction

The population of older adults is the fastest-growing segment of the Canadian population. In 2010, nearly 5 million Canadians aged 65 years and older; this segment of the population is expected to reach as high as 10.9 million by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2009). The results from the 2016 Canadian census showed that the population of those aged 65 years and older climbed to 16.9% of Canada’s population (Statistics Canada, 2017). As the prevalence of disability increases with age, the population of older Canadians with disabilities is also on the rise (Statistics Canada, 2009; Heikkinen, 2003). In 2012, nearly 3.8 million or 13.7% of the Canadian population, aged 15 years and older, reported limitations in their daily activities due to some types of disability (Statistics Canada, 2009; Statistics Canada, 2012). To have a better understanding of types of disabilities in Canada, it is worthwhile mentioning that according to the statistics Canada, more than 11% of Canadian adults faced one of the three most prevalent types of disability, including pain, mobility, or flexibility. Among those who were identified to have at least one of the mentioned types of disability in 2012, over 40% experienced all three types simultaneously. The next commonly reported types of disability were mental/psychological, 3.9%; dexterity, 3.5%; hearing, 3.2%; seeing, 2.7%; followed by memory and learning disabilities, 2.3% each. Also, developmental disability was reported for less than 1% of Canadian adults (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Social participation is a significant factor associated with overall health, life satisfaction, and quality of life of older adults (Gilmour, 2012; Menec & Nowicki, 2014; Ponce, Rosas & Lorca, 2014; Riddick, 1985; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994). Compared with younger adults, the effect of social participation on overall health in older adults is significantly higher (Lee, Jang, Lee, Cho & Park, 2008). For older adults, social participation is associated with reduced risk of mortality (Wilkins, 2003), disability (Escobar-Bravo, Puga-Gonzàlez & Martín-Baranera, 2012; Mendes de Leon, Glass & Berkman, 2003), and poor self-rated health (Fiori, Antonucci & Cortina, 2006; Glass, Mendes de Leon, Bassuk & Berkman, 2006), and improved cognitive functioning (Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Wilson, Bienias & Evans, 2004; Wang, Karp,Winblad & Fratiglioni, 2002) and health-related behaviors and lifestyle (Adams, Leibrandt & Moon, 2011).

Also, the importance of social participation in regard to the quality of life for older persons with physical disabilities living in the community is supported by Levasseure, Desrosiers & Noreau (2004). Philips (1967) used data from a survey of 600 adults in Chicago, and reported a direct relationship between volunteer work and life satisfaction and announced it as a strong predictor of well-being and happiness. Meier & Strutzer (2008) investigated the effects of different types of social activities on individuals’ life satisfaction in Germany among approximately 22,000 individuals with or without a disability. They found people with intrinsic voluntary social activities – those where volunteers received an internal reward as a direct result of their activity – with higher levels of life satisfaction than those with extrinsic activities when people may also receive utility from helping others in life. Yoon, Lee, Kim & Moon (2020) studied the effects of leisure participation and activities outside the home on the life satisfaction of older South Korean adults.

They indicated that productive participation in religious activity, social gatherings, and volunteering could significantly increase the quality of life in older Korean adults. Also, they showed that frequent participation in travel and cultural activities outside the home were positively related to life satisfaction. (2020). In a study by Bertelli-Costa & Neri on a large group of Brazilian older adults, there was a positive association between global life satisfaction and social activity participation. They discussed that the specific domain, in which activity was performed interfered with the perception of the adult about his or her life (Bertelli-Costa & Neri, 2019).

However, none of these studies examined the effect of social participation by type or severity of disability, or sex. Although health, well-being, and quality of life and their underlying determinants have been explored in the general population of older Canadian adults (Gilmour, 2012; Lee et al., 2008), less is known about the factors that influence health, life satisfaction, or the perception of healthy/active aging in older Canadian adults with disabilities. In particular, very little is known about participation in leisure and social activities of older Canadian adults with disabilities and its influence on health and well-being. The limited relevant information, however, has shown that persons with disabilities have a lower level of social participation (Seeman, 2000) and poorer perception of their overall health and well-being compared with those with no disabilities (Freedman, Stafford, Schwarz, Conrad & Cornman, 2012). Thus, disabilities can be seen as a major barrier to social participation (Kaye, 1998).

Although the association between participation in leisure and social activities among older adults has been investigated in general, (Rainer, 2014) to the best of our knowledge, studies that have examined the effects of participation in leisure and social activities on the general health and life satisfaction of older Canadian adults with a disability have not yet been conducted. Thus, the primary goal of the present study was to determine if participation in leisure and social activities has a statistically significant effect on the overall health and life satisfaction of older Canadian adults with disability, controlling for the effects of all the other potential contributing factors, such as type or severity of a disability. The knowledge gained can be utilized by those involved in the planning and provision of health and social support services to older adults with various types of disabilities to promote health and increase life satisfaction.

2. Methods

Study design and data source

The present study involved the secondary analysis of cross-sectional data obtained from Canadian adults (aged 15+ years) who participated in the Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS) 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2010), a post-census survey (Statistics Canada, 2006) that used the 2006 Canadian census as a sample frame to identify the population. The PALS 2006 consisted of questions designed to collect information on the prevalence of disability, social situations of people with disability, employment status, and participation in social activities (Statistics Canada, 2006). Those living on First Nations reserves, in institutions, and on military bases were excluded from the survey (Statistics Canada, 2006). The PALS 2006 data were accessed at Manitoba Research Data Center, Winnipeg, Canada.

The population of older adults is the fastest-growing segment of the Canadian population. In 2010, nearly 5 million Canadians aged 65 years and older; this segment of the population is expected to reach as high as 10.9 million by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2009). The results from the 2016 Canadian census showed that the population of those aged 65 years and older climbed to 16.9% of Canada’s population (Statistics Canada, 2017). As the prevalence of disability increases with age, the population of older Canadians with disabilities is also on the rise (Statistics Canada, 2009; Heikkinen, 2003). In 2012, nearly 3.8 million or 13.7% of the Canadian population, aged 15 years and older, reported limitations in their daily activities due to some types of disability (Statistics Canada, 2009; Statistics Canada, 2012). To have a better understanding of types of disabilities in Canada, it is worthwhile mentioning that according to the statistics Canada, more than 11% of Canadian adults faced one of the three most prevalent types of disability, including pain, mobility, or flexibility. Among those who were identified to have at least one of the mentioned types of disability in 2012, over 40% experienced all three types simultaneously. The next commonly reported types of disability were mental/psychological, 3.9%; dexterity, 3.5%; hearing, 3.2%; seeing, 2.7%; followed by memory and learning disabilities, 2.3% each. Also, developmental disability was reported for less than 1% of Canadian adults (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Social participation is a significant factor associated with overall health, life satisfaction, and quality of life of older adults (Gilmour, 2012; Menec & Nowicki, 2014; Ponce, Rosas & Lorca, 2014; Riddick, 1985; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994). Compared with younger adults, the effect of social participation on overall health in older adults is significantly higher (Lee, Jang, Lee, Cho & Park, 2008). For older adults, social participation is associated with reduced risk of mortality (Wilkins, 2003), disability (Escobar-Bravo, Puga-Gonzàlez & Martín-Baranera, 2012; Mendes de Leon, Glass & Berkman, 2003), and poor self-rated health (Fiori, Antonucci & Cortina, 2006; Glass, Mendes de Leon, Bassuk & Berkman, 2006), and improved cognitive functioning (Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Wilson, Bienias & Evans, 2004; Wang, Karp,Winblad & Fratiglioni, 2002) and health-related behaviors and lifestyle (Adams, Leibrandt & Moon, 2011).

Also, the importance of social participation in regard to the quality of life for older persons with physical disabilities living in the community is supported by Levasseure, Desrosiers & Noreau (2004). Philips (1967) used data from a survey of 600 adults in Chicago, and reported a direct relationship between volunteer work and life satisfaction and announced it as a strong predictor of well-being and happiness. Meier & Strutzer (2008) investigated the effects of different types of social activities on individuals’ life satisfaction in Germany among approximately 22,000 individuals with or without a disability. They found people with intrinsic voluntary social activities – those where volunteers received an internal reward as a direct result of their activity – with higher levels of life satisfaction than those with extrinsic activities when people may also receive utility from helping others in life. Yoon, Lee, Kim & Moon (2020) studied the effects of leisure participation and activities outside the home on the life satisfaction of older South Korean adults.

They indicated that productive participation in religious activity, social gatherings, and volunteering could significantly increase the quality of life in older Korean adults. Also, they showed that frequent participation in travel and cultural activities outside the home were positively related to life satisfaction. (2020). In a study by Bertelli-Costa & Neri on a large group of Brazilian older adults, there was a positive association between global life satisfaction and social activity participation. They discussed that the specific domain, in which activity was performed interfered with the perception of the adult about his or her life (Bertelli-Costa & Neri, 2019).

However, none of these studies examined the effect of social participation by type or severity of disability, or sex. Although health, well-being, and quality of life and their underlying determinants have been explored in the general population of older Canadian adults (Gilmour, 2012; Lee et al., 2008), less is known about the factors that influence health, life satisfaction, or the perception of healthy/active aging in older Canadian adults with disabilities. In particular, very little is known about participation in leisure and social activities of older Canadian adults with disabilities and its influence on health and well-being. The limited relevant information, however, has shown that persons with disabilities have a lower level of social participation (Seeman, 2000) and poorer perception of their overall health and well-being compared with those with no disabilities (Freedman, Stafford, Schwarz, Conrad & Cornman, 2012). Thus, disabilities can be seen as a major barrier to social participation (Kaye, 1998).

Although the association between participation in leisure and social activities among older adults has been investigated in general, (Rainer, 2014) to the best of our knowledge, studies that have examined the effects of participation in leisure and social activities on the general health and life satisfaction of older Canadian adults with a disability have not yet been conducted. Thus, the primary goal of the present study was to determine if participation in leisure and social activities has a statistically significant effect on the overall health and life satisfaction of older Canadian adults with disability, controlling for the effects of all the other potential contributing factors, such as type or severity of a disability. The knowledge gained can be utilized by those involved in the planning and provision of health and social support services to older adults with various types of disabilities to promote health and increase life satisfaction.

2. Methods

Study design and data source

The present study involved the secondary analysis of cross-sectional data obtained from Canadian adults (aged 15+ years) who participated in the Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS) 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2010), a post-census survey (Statistics Canada, 2006) that used the 2006 Canadian census as a sample frame to identify the population. The PALS 2006 consisted of questions designed to collect information on the prevalence of disability, social situations of people with disability, employment status, and participation in social activities (Statistics Canada, 2006). Those living on First Nations reserves, in institutions, and on military bases were excluded from the survey (Statistics Canada, 2006). The PALS 2006 data were accessed at Manitoba Research Data Center, Winnipeg, Canada.

Study samples

Data from respondents who reported disability and were at least 65 years of age at the time of the PALS 2006 were analyzed (n=7,500, representing 1,755,870 older Canadians) by representative sample, which meant that the sample matches characteristic feature of the population being targeted within the research variables (Glen, 2019).

Socio-demographic variables

The study samples was classified by age group: 1. 65-74 years (young-old); 2. 75-84 years (old-old); and 3. 85 years or older (oldest-old). Self-reported biological sex was defined as a dichotomous variable and coded as “0” for males and “1” for females.

Annual income. A categorical variable was defined to classify the respondents by individual annual income: 1. Low income – income of less than $14,520; 2. Lower middle income - income of $14,521-19,278; 3. Middle income - income of $19,279-30,670; and 4. High income - income of at least $30,671.

Living arrangements. Respondents were classified by the type of living arrangement: 1. Living with a spouse; 2. Living with a common-law partner; 3. Lone parents; 4. Living with their children; and 5. Living alone. We further defined living arrangement as a dichotomous variable: 1. Living alone was coded as “1”; and 2. Living with others (i.e., living with a spouse, common-law partner, lone parents, and children) was coded as “2”.

Social network. Respondents reported the number of close friends (not including relatives) with whom they felt they could speak to with ease about what was on their mind or call for help. A categorical variable was defined and used to classify the respondents by the size of their social network: 1. “none”; 2. “1 to 2”; 3. “3 to 5”; 4. “6 to 10”; 5. “11 to 20”, 6. “more than 21”, and 7. missing including those who “refused” to answer or reported “don’t know”, “not stated” or “not asked”.

Data from respondents who reported disability and were at least 65 years of age at the time of the PALS 2006 were analyzed (n=7,500, representing 1,755,870 older Canadians) by representative sample, which meant that the sample matches characteristic feature of the population being targeted within the research variables (Glen, 2019).

Socio-demographic variables

The study samples was classified by age group: 1. 65-74 years (young-old); 2. 75-84 years (old-old); and 3. 85 years or older (oldest-old). Self-reported biological sex was defined as a dichotomous variable and coded as “0” for males and “1” for females.

Annual income. A categorical variable was defined to classify the respondents by individual annual income: 1. Low income – income of less than $14,520; 2. Lower middle income - income of $14,521-19,278; 3. Middle income - income of $19,279-30,670; and 4. High income - income of at least $30,671.

Living arrangements. Respondents were classified by the type of living arrangement: 1. Living with a spouse; 2. Living with a common-law partner; 3. Lone parents; 4. Living with their children; and 5. Living alone. We further defined living arrangement as a dichotomous variable: 1. Living alone was coded as “1”; and 2. Living with others (i.e., living with a spouse, common-law partner, lone parents, and children) was coded as “2”.

Social network. Respondents reported the number of close friends (not including relatives) with whom they felt they could speak to with ease about what was on their mind or call for help. A categorical variable was defined and used to classify the respondents by the size of their social network: 1. “none”; 2. “1 to 2”; 3. “3 to 5”; 4. “6 to 10”; 5. “11 to 20”, 6. “more than 21”, and 7. missing including those who “refused” to answer or reported “don’t know”, “not stated” or “not asked”.

Disability-related variables

Type of disability. Respondents were asked about 10 different types of disability, including agility, development, hearing, learning, memory, mobility, pain, psychological, seeing, speaking, and unknown. We defined a new categorical variable to classify the respondents into three groups: 1. Movement - mobility or agility disabilities; 2. Sensory - seeing or hearing disability; and 3. Less visible - emotional, developmental, memory, learning, communication, or pain disabilities. Less than 5% of the sample reported their disability type as “unknown”. Those whose type of disability was not unknown were excluded from the analyses.

Degree of disability severity. A categorical variable was used to classify respondents by the severity of their disability: 1. No disability was coded as “0”; 2. Mild disability was coded as “1”; 3. Moderate disability was coded as “2”; 4. Severe disability was coded as “3”; and 5. Very severe disability was coded as “4”.

Health-related characteristics

Unmet needs for participation in leisure and social activities. Respondents were asked the yes/no question, “Would you like to do more activities during your spare time?” Responses were classified into one of two groups: 1. “Yes” responses implied that needs for participation were unmet and were coded as “1”; and 2. “No” responses were coded as “0”.

Type of disability. Respondents were asked about 10 different types of disability, including agility, development, hearing, learning, memory, mobility, pain, psychological, seeing, speaking, and unknown. We defined a new categorical variable to classify the respondents into three groups: 1. Movement - mobility or agility disabilities; 2. Sensory - seeing or hearing disability; and 3. Less visible - emotional, developmental, memory, learning, communication, or pain disabilities. Less than 5% of the sample reported their disability type as “unknown”. Those whose type of disability was not unknown were excluded from the analyses.

Degree of disability severity. A categorical variable was used to classify respondents by the severity of their disability: 1. No disability was coded as “0”; 2. Mild disability was coded as “1”; 3. Moderate disability was coded as “2”; 4. Severe disability was coded as “3”; and 5. Very severe disability was coded as “4”.

Health-related characteristics

Unmet needs for participation in leisure and social activities. Respondents were asked the yes/no question, “Would you like to do more activities during your spare time?” Responses were classified into one of two groups: 1. “Yes” responses implied that needs for participation were unmet and were coded as “1”; and 2. “No” responses were coded as “0”.

Participation in leisure and social activities. Because disability affects participation in leisure and social activities outside the home more than activities inside the home (Raymond, Grenier & Hanley, 2014), we used data from the following questions tapping activities outside the home: “In the past 12 months, did you participate in any of the following activities outside your home? A. Visiting family or friends; B. Doing physical activities, such as exercise, walking or playing sports; C. Attending sporting or cultural events, such as plays or movies; D. Visiting museums, libraries or national or provincial parks”. A “yes” response to each question implied participation in social and leisure activities. Subsequently, these respondents were asked to report the frequency of their participation in each activity. Responses were coded as: 4: “Everyday”; 3: “At least once a week”; 2: “At least once a month”; 1: “Less than once a month”; and 9: “Never”. Response refusals or “Don’t know” were coded as missing and were excluded from the analyses. The average score on all four items was 6.0 (Md=6.0); this score was used as the cut-off score to classify respondents into two groups based on their average scores: 1. 1-6: “Low participation in leisure and social activities”; and 2. 7-16:“High participation in leisure and social activities”. A third category was defined as “No participation in leisure and social activities” that included those with “No” responses to all of the four questions.

Barriers to participation in leisure and social activity. The PALS 2006 asked respondents to specify obstacles preventing them from active participation in the society: “What prevents you from doing more leisure activities?” Responses were categorized as follows: 1. “Condition”; 2. “Need for special aids/equipment”; 3. “Need for someone’s assistance”; 4. “Inadequacy of transportation services”; 5. “No facilities or programs”; 6. “Inaccessibility of facilities, or equipment”; and 7. “Expense”. Less than 5% of the sample had missing data and were excluded from the analyses.

Dependent Variables

General health. Respondents were asked a single question to assess their own general health on a five-point scale (1. “Excellent”; 2. “Very good”; 3. “Good”; 4. “Fair”; and 5. “Poor”). Those who answered “do not know” or “refused” were excluded from the analyses. Due to the low number of people who reported “poor” general health status, self-rated health response categories were combined and we classified the respondents into two groups: 1. Excellent, very good, or good responses were coded as (1: “Overall health was positive”); and 2. Fair or poor responses were coded as (0: “Overall health as negative”).

Life satisfaction. Life satisfaction was measured using five questions: a. “Are you satisfied with your relationships with family members?”; b. “Are you satisfied with your relationships with friends?”; c. “Are you satisfied with your health?”; d. “Are you satisfied with your job or main activity?”; e. “Are you satisfied with the way you spend your time?” Respondents rated their feelings on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1: “very dissatisfied”; and 10: “very satisfied”. The average score of general life satisfaction on all five items was 7.7 (Md=8.0). Respondents were classified into two categories based on their average score: 1. Average scores between 1 and 7 were classified as “unsatisfied with life”; and 2. average scores between 8 and 10 were classified as “satisfied with life”.

Barriers to participation in leisure and social activity. The PALS 2006 asked respondents to specify obstacles preventing them from active participation in the society: “What prevents you from doing more leisure activities?” Responses were categorized as follows: 1. “Condition”; 2. “Need for special aids/equipment”; 3. “Need for someone’s assistance”; 4. “Inadequacy of transportation services”; 5. “No facilities or programs”; 6. “Inaccessibility of facilities, or equipment”; and 7. “Expense”. Less than 5% of the sample had missing data and were excluded from the analyses.

Dependent Variables

General health. Respondents were asked a single question to assess their own general health on a five-point scale (1. “Excellent”; 2. “Very good”; 3. “Good”; 4. “Fair”; and 5. “Poor”). Those who answered “do not know” or “refused” were excluded from the analyses. Due to the low number of people who reported “poor” general health status, self-rated health response categories were combined and we classified the respondents into two groups: 1. Excellent, very good, or good responses were coded as (1: “Overall health was positive”); and 2. Fair or poor responses were coded as (0: “Overall health as negative”).

Life satisfaction. Life satisfaction was measured using five questions: a. “Are you satisfied with your relationships with family members?”; b. “Are you satisfied with your relationships with friends?”; c. “Are you satisfied with your health?”; d. “Are you satisfied with your job or main activity?”; e. “Are you satisfied with the way you spend your time?” Respondents rated their feelings on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1: “very dissatisfied”; and 10: “very satisfied”. The average score of general life satisfaction on all five items was 7.7 (Md=8.0). Respondents were classified into two categories based on their average score: 1. Average scores between 1 and 7 were classified as “unsatisfied with life”; and 2. average scores between 8 and 10 were classified as “satisfied with life”.

Analytical Approach

Weighted frequencies were used to describe the study population, their socio-demographic, disability-related, and health characteristics, and their level of participation in leisure and social activities. Weighted data were used to estimate the proportion of older Canadians with a disability who reported unmet needs in terms of participation in leisure and social activities and determined the most commonly reported barriers for participation. Next, we used cross-tabulations to describe the sociodemographic, disability-related, and health-related characteristics of the target population, their level of participation in leisure and social activities, general health, and life satisfaction. A Chi-square test was used to assess the association between participation in social and leisure activities, and all other potential independent variables and their association with the two study outcomes of interest. The study factors that were significantly associated with the two study outcomes of interest were considered for inclusion in the multivariate analyses.

Two sets of multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted. In the first set, three models (one based on the total sample, and one for each sex) were developed to examine the independent effect of participation in leisure and social activities on general health, controlling for the effects of other potential contributing factors. In the second set, three models (one based on the total sample, and one for each sex) were developed to examine the independent effect of participation in leisure and social activities on life satisfaction, controlling for the effects of other potential contributing factors. Because the two outcome variables of interest were binary variables, logistic regression was used to determine the variables that were significantly associated with the probability of the outcome. We used the odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals to determine factors that were significantly associated with the study outcomes of interest. Results at the 0.05 level were considered to be significant. Due to the complex design of the PALS 2006, bootstrap weights were applied to the data when conducting statistical testing to provide more accurate estimates of variance and confidence intervals (Wehrens, Putter & Buydens, 2000). The data were analyzed by SPSS version 14 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and STATA version 8 software packages (Stata Corp, 2003).

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Statistics Canada to access the micro-level confidential master data file at the Research Data Center (RDC) at the University of Manitoba and by the Health Research Ethics Board (HREB) at the University of Manitoba.

3. Results

Sociodemographic and disability-related characteristics

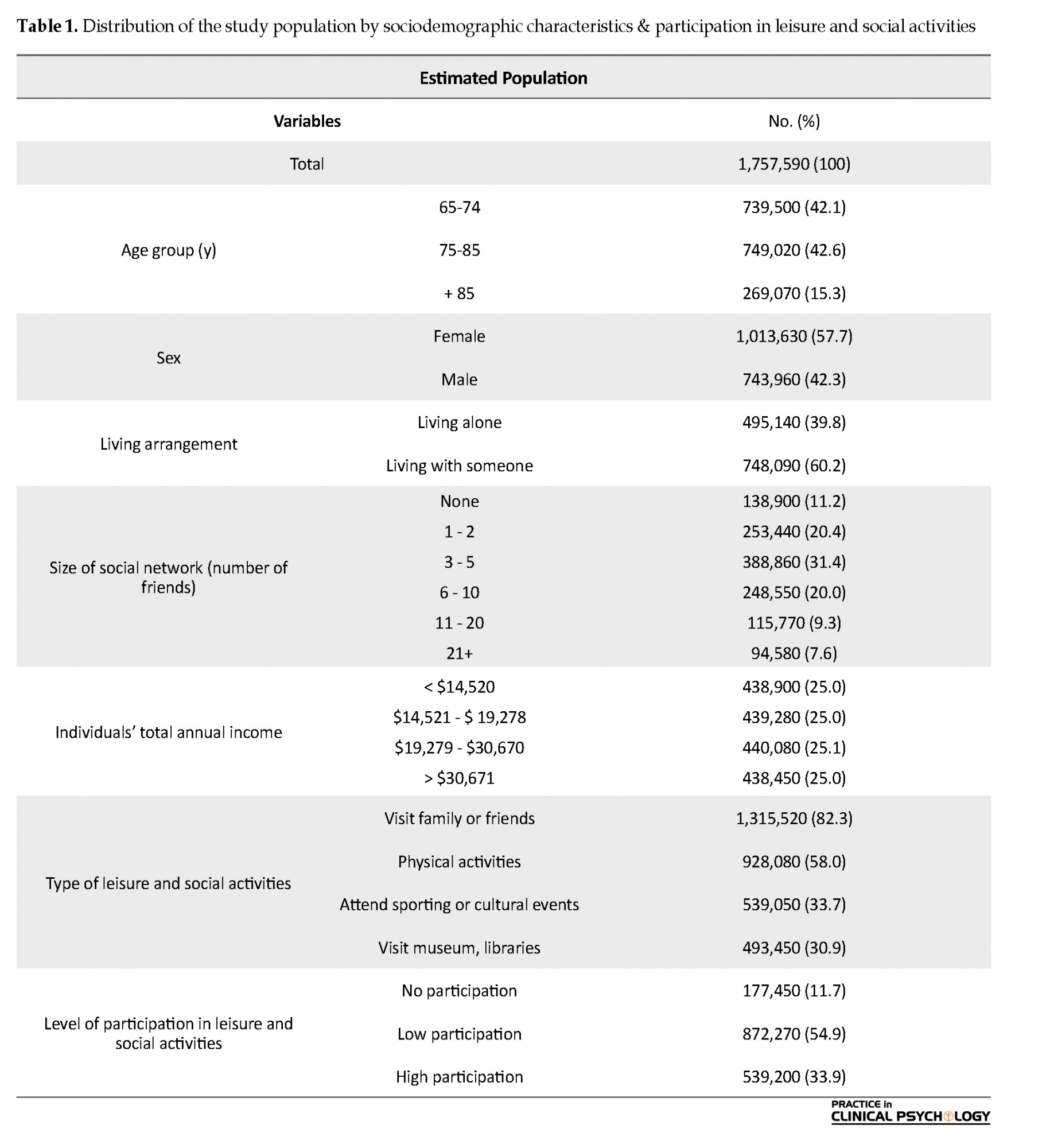

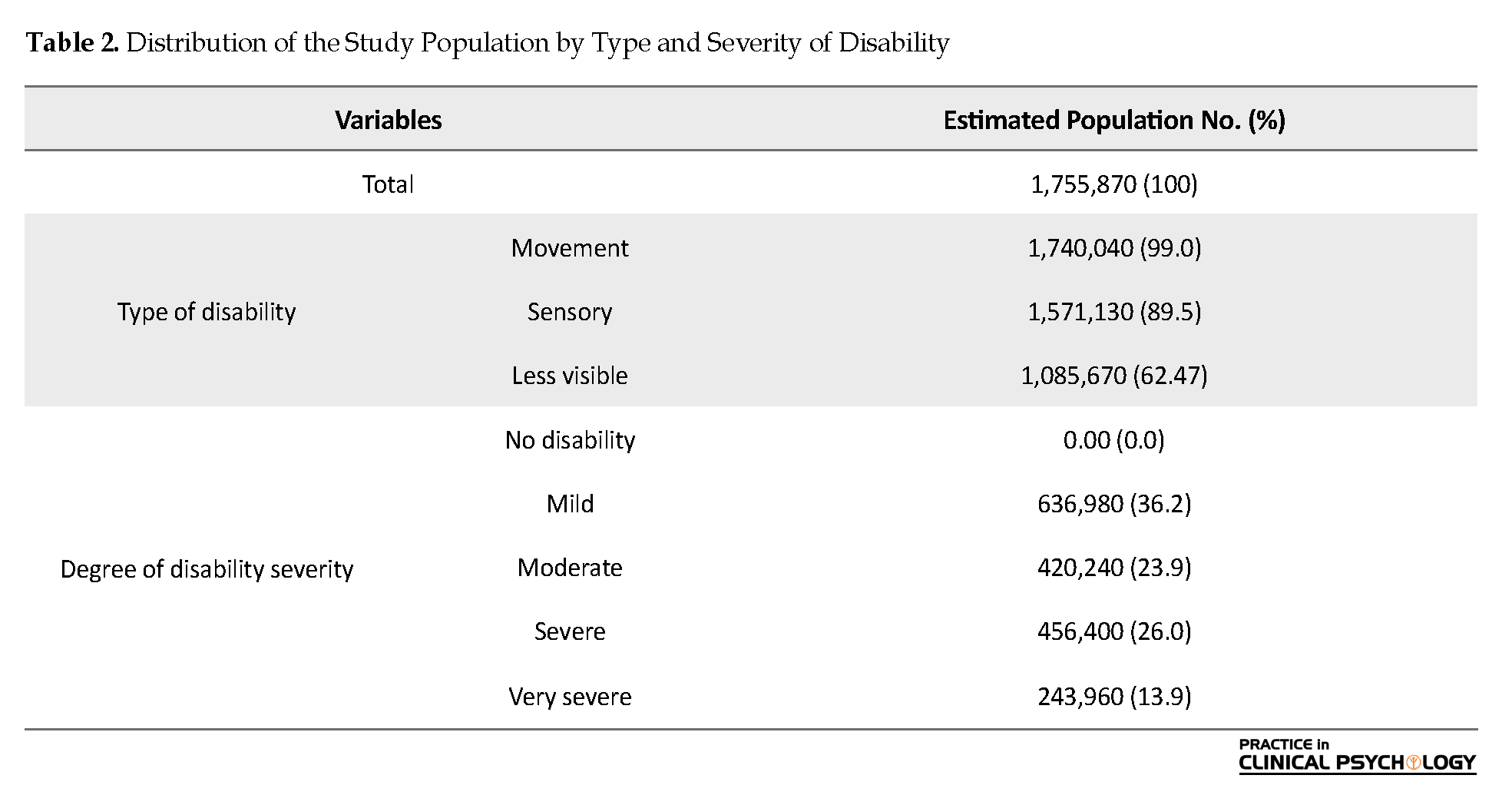

According to PALS 2006, an estimated 1,757,590 Canadians aged 65 years and older reported some type of disability (Statistics Canada, 2010). Table 1 presents the distribution of the study population by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. As can be seen in Table 2, over one-third of the study population (36.2%) reported a mild disability, and only 13.9% reported very severe disability (Statistics Canada, 2010).

Participation in leisure and social activities and effects on health and well-being more than half of the study population reported low levels of participation in leisure and social activities (54.9%; n=872,270). Approximately 82.3% of the study population reported that they had visited their family or friends in the past 12 months and 30.9% reported that they visited museums or libraries. A large percentage of the target population (~42%) reported no physical activity. A large proportion of the study population (36.7%) reported unmet needs for leisure and social activities. As can be seen in Table 3, over two-thirds of the study population that reported unmet needs for participation in leisure and social activities indicated that their condition was a barrier to participation in leisure and social activities. The next most commonly reported barrier was the “need for someone’s assistance” (16.6%), followed by “inadequate transportation services” (12.9%).

Weighted frequencies were used to describe the study population, their socio-demographic, disability-related, and health characteristics, and their level of participation in leisure and social activities. Weighted data were used to estimate the proportion of older Canadians with a disability who reported unmet needs in terms of participation in leisure and social activities and determined the most commonly reported barriers for participation. Next, we used cross-tabulations to describe the sociodemographic, disability-related, and health-related characteristics of the target population, their level of participation in leisure and social activities, general health, and life satisfaction. A Chi-square test was used to assess the association between participation in social and leisure activities, and all other potential independent variables and their association with the two study outcomes of interest. The study factors that were significantly associated with the two study outcomes of interest were considered for inclusion in the multivariate analyses.

Two sets of multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted. In the first set, three models (one based on the total sample, and one for each sex) were developed to examine the independent effect of participation in leisure and social activities on general health, controlling for the effects of other potential contributing factors. In the second set, three models (one based on the total sample, and one for each sex) were developed to examine the independent effect of participation in leisure and social activities on life satisfaction, controlling for the effects of other potential contributing factors. Because the two outcome variables of interest were binary variables, logistic regression was used to determine the variables that were significantly associated with the probability of the outcome. We used the odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals to determine factors that were significantly associated with the study outcomes of interest. Results at the 0.05 level were considered to be significant. Due to the complex design of the PALS 2006, bootstrap weights were applied to the data when conducting statistical testing to provide more accurate estimates of variance and confidence intervals (Wehrens, Putter & Buydens, 2000). The data were analyzed by SPSS version 14 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and STATA version 8 software packages (Stata Corp, 2003).

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Statistics Canada to access the micro-level confidential master data file at the Research Data Center (RDC) at the University of Manitoba and by the Health Research Ethics Board (HREB) at the University of Manitoba.

3. Results

Sociodemographic and disability-related characteristics

According to PALS 2006, an estimated 1,757,590 Canadians aged 65 years and older reported some type of disability (Statistics Canada, 2010). Table 1 presents the distribution of the study population by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. As can be seen in Table 2, over one-third of the study population (36.2%) reported a mild disability, and only 13.9% reported very severe disability (Statistics Canada, 2010).

Participation in leisure and social activities and effects on health and well-being more than half of the study population reported low levels of participation in leisure and social activities (54.9%; n=872,270). Approximately 82.3% of the study population reported that they had visited their family or friends in the past 12 months and 30.9% reported that they visited museums or libraries. A large percentage of the target population (~42%) reported no physical activity. A large proportion of the study population (36.7%) reported unmet needs for leisure and social activities. As can be seen in Table 3, over two-thirds of the study population that reported unmet needs for participation in leisure and social activities indicated that their condition was a barrier to participation in leisure and social activities. The next most commonly reported barrier was the “need for someone’s assistance” (16.6%), followed by “inadequate transportation services” (12.9%).

Significant associations were found between age, sex, living arrangement, social network, individual annual income, sensory disability, less visible disability, movement disability, the severity of a disability, and level of participation in leisure and social activities. Reported unmet needs were also associated with participation in leisure and social activities. Those with a less visible disability had higher levels of no participation compared to those who did not have a less visible disability (13.9% vs. 7.6%). Moreover, the degree of severity of disability was inversely associated with participation in leisure and social activities.

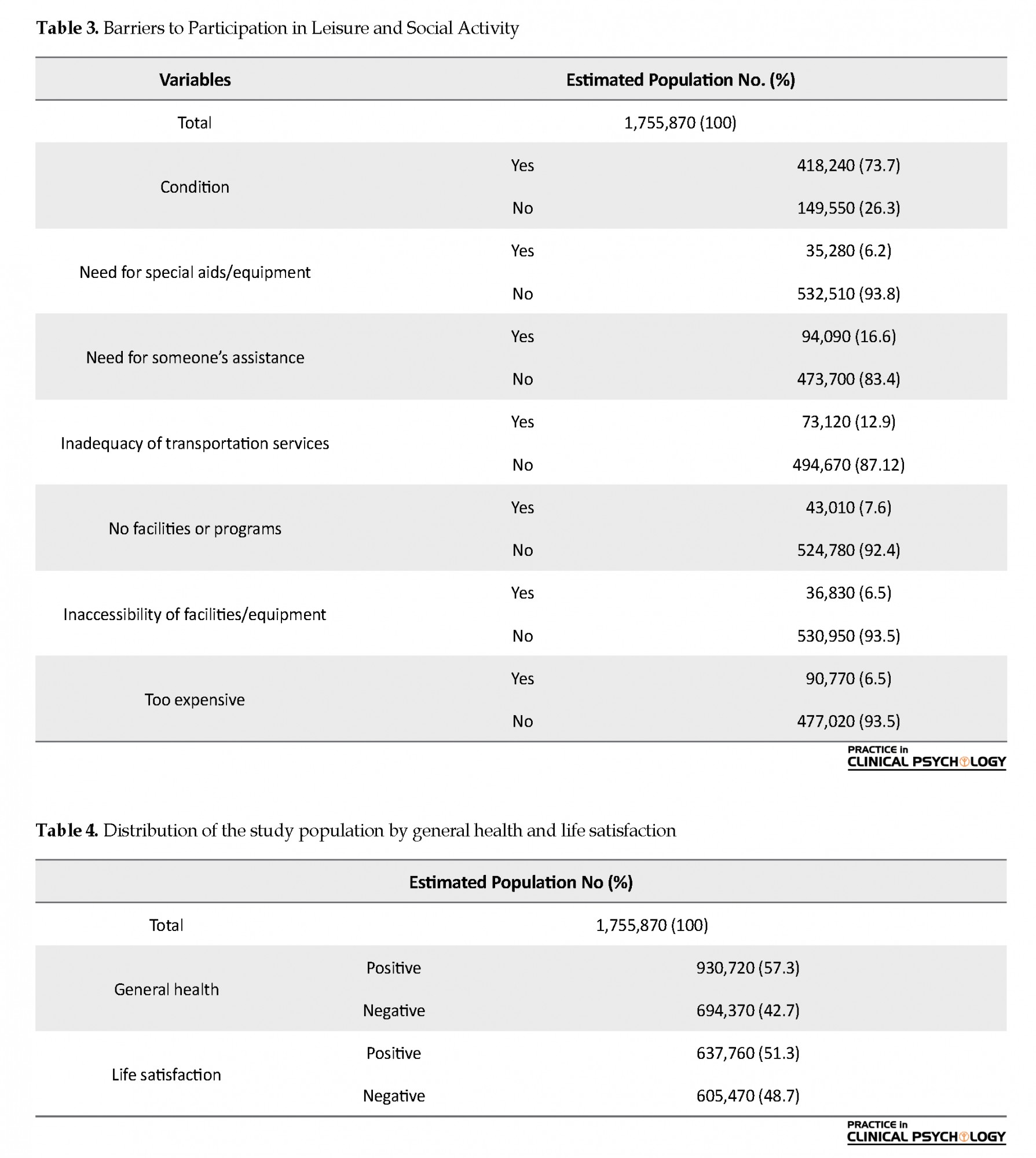

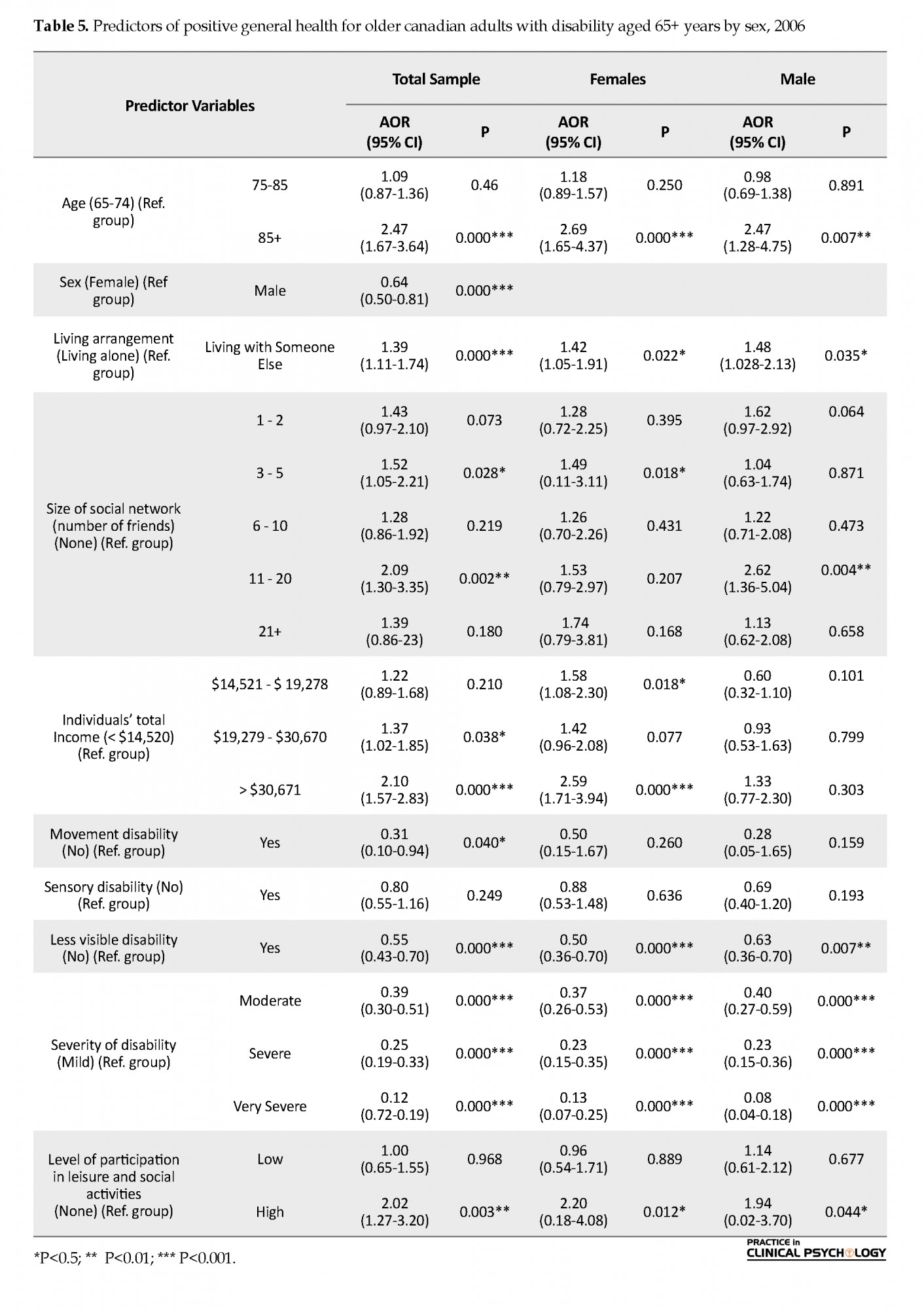

General health. Examination of the general health revealed that the majority of older Canadians with disability (57.3%) reported their positive general health and slightly more than half (51.3%) reported positive life satisfaction (Table 4). Results of the multivariate analyses showed significant independent effects of all the study factors on the odds of reporting positive general health, except for sensory disability (Table 5). Of particular note is that respondents who reported a high level of participation in leisure and social activities, had a twice greater odds of reporting positive general health compared with those who did not report participation in any of the leisure or social activities asked on the survey (AOR=2.02 (95%CI=1.27, 3.20)). The odds of reporting positive general health were also significantly reduced by the increased severity of a disability. Our analysis also revealed an important sex difference in one of the predictors of positive general health: Level of income was a significant predictor of general health among women, but not among men.

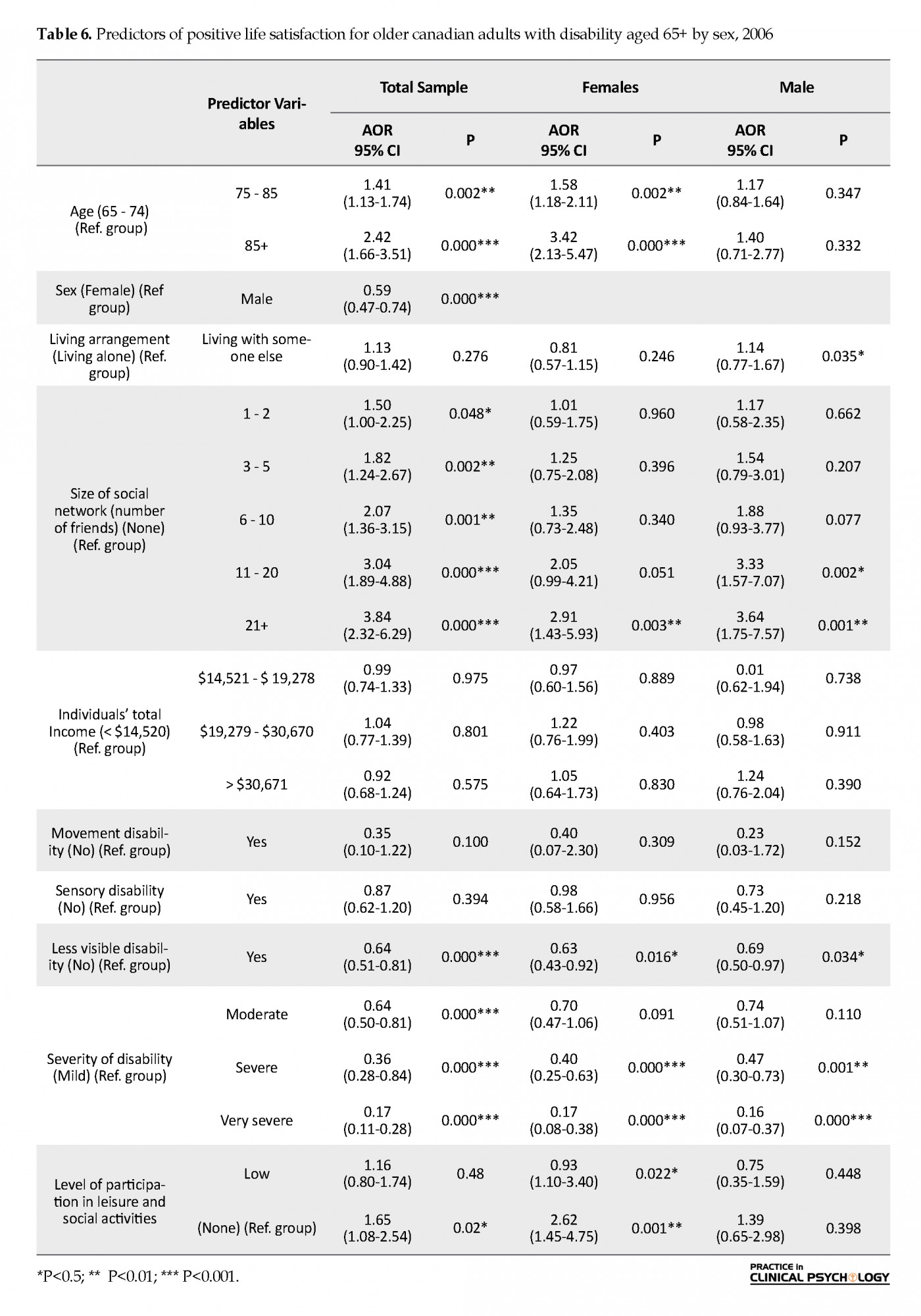

Life Satisfaction. As shown in Table 6, there were significant associations between life satisfaction and age and sex. Those who were the oldest old (aged 85 years or older) had almost 2.5 times higher odds of reporting being satisfied with their life than those in the younger age group older (AOR=2.47 (95%CI=1.67, 3.64)). Controlling for the effects of all the other factors, men had significantly lower odds of reporting being satisfied with their life (AOR=0.64 (95%CI=0.50, 0.81)). A significant association was also found between life satisfaction and social network, with those having a higher number of friends having increased odds of being satisfied with their life. Moreover, life satisfaction was significantly associated with having a less visible disability, and severity of a disability, such that less visible and more severe disabilities had reduced odds of reporting life satisfaction compared with those with no visible or less severe disabilities. Importantly, a high level of participation in leisure and social activities was found to be significantly associated with increased odds of reporting being satisfied with life among women (AOR=2.62 (95%CI=1.45, 4.75)), but not men (AOR=1.39 (95%CI=0.65, 2.98)).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study was the first study based on a nationally representative sample of older Canadians with disabilities to examine the effects of participation in leisure and social activities on general health and life satisfaction. Although previous research has examined the relationships between social participation and general health or life satisfaction in older populations (Gilmour, 2012; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994) less is known, specifically about the relationships between these factors in older Canadian adults with disabilities. Overall, our findings fill these gaps in knowledge.

Participation in leisure and social activities

We found that 11.7% of older Canadians with disabilities did not participate in any leisure or social activities, and, consistent with previous research (Lee et al., 2008), participation in leisure and social activities also decreased with age. These observed age differences in participation in leisure and social activities may be due to the normal aging or pathological factors. Canadian men also had a slightly higher level of participation in leisure and social activities than did women. This difference might be due to the gendered division of labor within the family. Women’s participation in leisure and social activities may be limited because they take responsibility for more household work than do men. In Canada, this gender gap in household work has been closing, but it is larger for older than younger generations (Mäntyselkä, Turunen, Ahonen & Kumpusalo, 2003).

In the present study, older Canadians with disabilities who lived with others reported higher levels of participation in leisure and social activities compared with those living alone, and as the number of friends increased, participation in leisure and social activities also increased. Previous research has shown a significant relationship between the size of social networks and the level of social participation (Chang, Weay & Lin, 2014). Living with another person may provide a sense of social support and purpose and control over one’s life, which can be particularly crucial for the well-being of people with disabilities (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003; Diehl, 1998; Peat, Thomas, Handy & Croft, 2004). Strong support systems (e.g. having good peer relationships) are especially important for those with disabilities because it may help them cope with their disability, and encourages participation in social activities (Goldberg, Higgins, Raskind & Herman, 2003).

Consistent with previous reports (Conference Board of Canada, 2016), higher income level was significantly associated with higher levels of participation in leisure and social activities among the target population. Persons with disabilities from higher household incomes might be more likely to overcome some of the barriers for participation in leisure and social activities, including those related to transportation expenses, medical and pharmacological expenses, or access to specialized equipment for participation (Shooshtari, Naghipur & Zhang, 2012).

We found significant associations between the level of participation in leisure and social activities with less visible types of disability and the severity of the disability. This is consistent with other research showing that people with aphasia (a language impairment) often report having fewer friends and smaller social networks (Davidson, Howe, Worrall, Hickson & Togher, 2008). The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain (Lethem, Slade, Troup & Bentley, 1983) may help to partly explain these findings. According to this model, fear of embarrassment, discomfort, or pain may result in avoidance of leisure and social activities, and less activity may lead to increased depressive symptoms, which may (in turn) lead to further decreases in participation in activities. In order to promote participation in leisure and social activities, and prevent social isolation (an important risk factor for premature death and other health outcomes in older people (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris & Stephenson, 2015), the specific needs around leisure and social activities of this population must be met. Interestingly, we found that sensory disability was not associated with participation in leisure and social activities.

This may be because many individuals with hearing impairments consider themselves to be a part of the deaf community, which provides a sense of belonging to a large social network (Padden & Humphries, 2005). Thus, even when older adults with vision and hearing impairments report comorbidities, sensory impaired adults were more likely to sustain valued social participation roles compared with their peers without sensory impairments (Cambell, Crews, Moriarty, Zack & Blackman, 1999).

Participation in leisure and social activities and effects on health and well-being

In the present study, satisfaction with life increased with increasing age; a similar positive association was found between general health and age. Previous studies have reported parallel findings (Steel, 2016), even those studies involving older adults with chronic pain (Mäntyselkä et al., 2003; Cleeland & Ryan, 1994; Hunfeld, 2001). Some studies have suggested that when individuals age, their attitudes towards pain (or their general health) change because they consider increased pain (or decreasing general health) to be a natural part of the aging process and may not report problems when surveyed (Jakobsson, Klevsgård, Westergren & Hallberg, 2003). Contrary to other research, we did not find a significant sex difference in the assessment of overall health. Cott, Gignac & Badley (1999) and Zunzunegui et al. (2004) noted that women had a more positive perception of their health and were more satisfied with their life compared with men, even when they suffered from chronic diseases, such as osteoarthritis or chronic pain. These findings indicate that women may have better mechanisms to cope with pain or other health problems.

Living arrangement and size of the social support network were significant factors associated with the study participants’ self-report of general health and life satisfaction. By increasing the number of friends, the likelihood of reported negative health and life satisfaction decreased; however, a plateau effect was observed when examining general health, such that having more than 3-5 friends did not result in increased ratings of positive general health. In a study on self-rated health and social network conducted on two French-speaking communities in Quebec, older Canadians with disabilities who had fewer friends also had higher odds of reporting poor self-rated health (Zunzunegui et al., 2004). Thus, receiving support from friends and family and having a life mate have important positive effects on leisure-time physical activity (Booth, Owen, Bauman, Clavisi & Leslie, 2000; Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2002; Krahn, Fujiura, Drum, Cardinal & Nosek, 2009) and general health (Zunzunegui et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005).

Consistent with other studies (Cott et al., 1999), we found a significant association between the annual income and general health among older Canadians with disabilities. Financial problems can cause stress and anxiety and may reduce access to medical care or social services, both may negatively influence general health and well-being (Williams & Collins, 1995).

Participation in leisure and social activities was found to be an independent determinant of both general health and life satisfaction among older Canadians with disabilities. Those who reported high participation in leisure and social activities had significantly increased odds of reporting positive general health and being satisfied with their life compared with those who did not participate. These results are similar to those reported in previous studies examining general health and satisfaction with life in the general population of seniors (Gilmour, 2012; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994).

Several limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. First, our analysis was based on cross-sectional data obtained from the PALS 2006; thus, it was not possible to measure changes in the variables of interest for the study population over time or to establish the temporal relationship between variables. Therefore, no causal inferences could be made based on the results. Another limitation relates to the measure of disability itself. Participants were those who self-reported having an activity limitation, which was the basis for classifying individuals with a “disability’. Persons with cognitive or intellectual disabilities might not have a complete understanding of their activity limitations (Statistics Canada, 2006). In contrast, the number of Canadians who reported having mild to severe disability has increased over time (Statistics Canada, 2006), suggesting that Canadians are more accepting of disabilities, this may, in turn, lead to individuals being more comfortable disclosing their disability.

Proxy responding is another source of bias that potentially affected the results of this study. Statistics Canada reported the overall proxy rate for PALS 2006 adult survey at 12.1%26. PALS allowed those who were absent during the time of the survey, could not speak English or French, or could not participate due to mental or physical problems to participate in the survey by proxy responding (Statistics Canada, 2006). The proxy respondent must have had enough knowledge of the individual’s disability and their limitations. Proxy responding is common among adults aged 75 years and older (Statistics Canada, 2006). The PALS master data file did not contain specific information on proxy responding; therefore, it was not possible to investigate the impact of proxy responding to the results of the present study. The PALS data also did not indicate if participants’ responses were made in the presence of another person.

5. Conclusion

There is a great need for more studies based on longitudinal data to monitor the general health and life satisfaction of adults with disabilities as they age. Important data are being collected in this regard. The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), (Zunzunegui et al., 2004) a national-level survey of longitudinal nature, will follow approximately 50,000 men and women between ages of 45 and 85 years for at least 20 years, for providing information on changing biological, medical, psychological, social lifestyle, and economic aspects of older Canadian’s lives. Using the CLSA data, future studies can examine transitions in participation in leisure and social activities in relation to changes in health and life satisfaction over time to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that impede or promote social participation and therefore health and well-being of older Canadians.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed of the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This paper is based on the MSc. thesis of the first author for partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master's degree in Family Social Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari, Karen Duncan, Verena Menec; Methodology: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari; Investigation: Hanieh Chizari; Writing – original draft: Hanieh Chizari; Writing – review & editing: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari, Karen Duncan, Verena Menec; Resources: Shahin Shooshtari; Supervision: Shahin Shooshtari.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Shahin Shooshtari, for her support and guidance throughout the process of this research. I would also like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Karen Duncan and Dr. Verena Menec who provided guidance and supported me with my thesis research project. I also thank Dr. Ian Clara at Manitoba Research Data Centre for his guidance regarding the survey data used and the methods of analysis.

References

Adams, K. B., Leibrandt, S., & Moon, H. (2011). A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing & Society, 31(4), 683-712. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X10001091]

Barnes, L. L., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Wilson, R. S., Bienias, J. L., & Evans, D. A. (2004). Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology, 63(12), 2322-6. [DOI:10.1212/01.WNL.0000147473.04043.B3] [PMID]

Bertelli-Costa, T., & Neri, A. L. (2019). Life satisfaction and participation among community-dwelling older adults: Data from the FIBRA study. Journal of Health Psychology. [DOI:10.1177/1359105319893020] [PMID]

Booth, M. L., Owen, N., Bauman, A., Clavisi, O., & Leslie, E. (2000). Social-cognitive and perceived environment influences associated with physical activity in older Australians. Preventive Medicine, 31(1), 15-22. [DOI:10.1006/pmed.2000.0661] [PMID]

Campbell, V. A., Crews, J. E., Moriarty, D. G., Zack, M. M., & Blackman, D. K. (1999). Surveillance for sensory impairment, activity limitation, and health-related quality of life among older adults -- United States, 1993-1997. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48(SS08), 131-56. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss4808a6.htm

Chang, P. J., Weay, L., & Lin, Y. (2014). Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults. Health Psychology, 33(6), 516-23. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000051] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cleeland, C. S., & Ryan, K. M. (1994). Pain assessment: Global use of the brief pain inventory. Annual of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23(2), 129-38. [PMID]

Conference Board of Canada. (2016). Compensation planning outlook-increases by region: Planned average salary Increases, by region, 2016. Retrieved from: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/topics/humanresource/compensation-outlook-image.aspx

Cott, C. A., Gignac, M. A., & Badley, E. M. (1999). Determinates of self rated health for Canadians with chronic disease and disability. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 53(11), 731-6. [DOI:10.1136/jech.53.11.731] [PMID] [PMCID]

Davidson, B., Howe, T., Worrall, L., Hickson, L., & Togher, L. (2008). Social participation for older people with aphasia: The impact of communication disability on friendships. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 15(4), 325-40. [DOI:10.1310/tsr1504-325] [PMID]

Diehl, M. (1998). Everyday competence in later life: Current status and future directions. The Gerontologist, 38(4), 422-33. [DOI:10.1093/geront/38.4.422] [PMID]

Escobar-Bravo, M. Á., Puga-Gonzàlez, D., & Martín-Baranera, M. (2012). Protective effects of social networks on disability among older adults in Spain. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 54(1), 109-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.008] [PMID]

Fiori, K. L., Antonucci, T. C., & Cortina, K. S. (2006). Social network typologies and mental health among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 61(1), P25-32. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/61.1.P25] [PMID]

Freedman, V. A., Stafford, F., Schwarz, N., Conrad, F., & Cornman, J. C. (2012). Disability, participation, and subjective wellbeing among older couples. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 588-96. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.018] [PMID] [PMCID]

Glen, S. (2019). Representative sample: Simple definition, examples. Retrieved from https://www.statisticshowto.com/representative-sample/

Giles-Corti, B., & Donovan, R. J. (2002). The relative influence of individual, social, and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 54(12), 1793-812.[DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00150-2]

Gilmour, H. (2012). Social participation and the health and well-being of Canadian seniors. Health Reports, 23(4), 23-32. [PMID]

Glass, T. A., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Bassuk, S. S., & Berkman, L. F. (2006). Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Aging and Health, 18(4), 604-28. [DOI:10.1177/0898264306291017] [PMID]

Goldberg, R. J., Higgins, E. L., Raskind, M. H., & Herman, K. L. (2003). Predictors of success in individuals with learning disabilities: A qualitative analysis of a 20-year longitudinal study. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18(4), 222-36. [DOI:10.1111/1540-5826.00077]

Heikkinen, E. (2003). What are the main risk factors for disability in old age and how can disability be prevented? Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/document/E82970.pdf

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives Psychooical Sciences, 10(2), 227-37. [DOI:10.1177/1745691614568352] [PMID]

Hunfeld, J. A., Perquim, C. W., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Hazebroek-Kampschreur, A. A., Passchier, J., & van Suijlekom-Smit, L. W., et al. (2001). Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26(3), 145-53. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.145] [PMID]

Jakobsson, U., Klevsgård, R., Westergren, A., & Hallberg, I. R. (2003). Old people in pain: A comparative study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 26(1), 625-36. [DOI:10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00145-3]

Kaye, H. S. (1998). Is the status of people with disabilities improving? Disability Statistics Abstract, (21), 1-4. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED421824

Krahn, G. L., Fujiura, G., Drum, C. E., Cardinal, B. J., Nosek, M. A., & RRTC Expert Panel on Health Measurement. (2009). The dilemma of measuring perceived health status in the context of disability. Disability and Health Journal, 2(2), 49-56. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S193665740900003X

Lee, H. Y., Jang, S. N., Lee, S., Cho, S. I., & Park, E. O. (2008). The relationship between social participation and self-rated health by sex and age: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(7), 1042-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.05.007] [PMID]

Lethem, J., Slade, P. D., Troup, J. D. G., & Bentley, G. (1983). Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception--I. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(4), 401-8. [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8]

Levasseur, M., Desrosiers, J., & Noreau, L. (2004). Is social participation associated with quality of life of older adults with physical disabilities? Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(20), 1206-13. [DOI:10.1080/09638280412331270371] [PMID]

Mäntyselkä, P. T., Turunen, J. H. O., Ahonen, R. S., & Kumpusalo, E. A. (2003). Chronic pain and poor self-rated health. JAMA, 290(18), 2435-42. [DOI:10.1001/jama.290.18.2435] [PMID]

Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2008). Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica, 75(297), 39-59. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00597.x]

Mendes de Leon, C. F., Glass, T. A., & Berkman, L. F. (2003). Social engagement and disability in a community population of older adults: The new haven EPESE. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(7), 633-42. [DOI:10.1093/aje/kwg028] [PMID]

Menec, V. H., & Nowicki, S. (2014). Examining the relationship between communities’ “age- friendliness” and life satisfaction and self-perceived health in rural Manitoba, Canada. Rural and Remote Health, 14, 2594. [PMID]

Padden, C., & Humphries, T. (2005). Inside deaf culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=2B4XWIFPgowC&dq

Peat, G., Thomas, E., Handy, J., & Croft, P. (2004). Social networks and pain interference with daily activities in middle and old age. Pain, 112(3), 379-405. [DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.029] [PMID]

Phillips, D. L. (1967). Social participation and happiness. American Journal of Sociology, 72(5), 479-88. [DOI:10.1086/224378] [PMID]

Ponce, M. S. H., Rosas, R. P. E., & Lorca, M. B. F. (2014). Social capital, social participation and life satisfaction among Chilean older adults. Revista de Saúde Pública, 48(5), 739-49. [DOI:10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004759] [PMID] [PMCID]

Rainer, S. (2014). Social participation and social engagement of elderly people. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 780-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.297]

Raymond, É., Grenier, A., & Hanley, J. (2014). Community participation of older adults with disabilities. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 24(1), 50-62. [DOI:10.1002/casp.2173]

Riddick, C. C. (1985). Health, aquariums, and the non-institutionalized elderly. Marriage & Family Review, 8(3-4), 163-73. [DOI:10.1300/J002v08n03_12]

Riddick, C. C., & Daniel, S. N. (1984). The relative contribution of leisure activities and other factors to the mental health of older women. Journal of Leisure Research, 16(2), 136-48. [DOI:10.1080/00222216.1984.11969581]

Riddick, C. C., & Stewart, D. G. (1994). An examination of the life satisfaction and importance of leisure in the lives of older female retirees: A comparison of blacks to whites. Journal of Leisure Research, 26(1), 75-87. [DOI:10.1080/00222216.1994.11969945]

Seeman, T. E. (2000). Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes of older adults. American Journal of Health Promotion, 14(6), 362-70. [DOI:10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362] [PMID]

Shooshtari, Sh., Naghipur, S., & Zhang, J. (2012). Unmet healthcare and social services needs of older Canadian adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 81-91. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-1130.2012.00346.x]

Statistics Canada. (2012). A profile of persons with disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years or older. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2015001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2010). “The 2006 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey: Analytical report”, Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division, Catalogue no. 89-628-XIE-No.002. Ottawa, Ontario, December 2014. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-628-x/89-628-x2007002-eng.pdf?st=AYnQGsHY

Statistics Canada. (2009). Seniors. Retrieved April 3, 2011, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2006). A brief history. Retrieved June 12, 2014 from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/ref/dict/overview-apercu/pop1-eng.cfm

StataCorp. 2003. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Statistics Canada, (2017). Age and sex, and type of dwelling data: Key results from the 2016 Census, Retrived from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170503/dq170503a-eng.htm

Steel, M. (2016). Measuring national well-being: At what age is personal well-being the highest? Estimates of personal well-being, with analysis by country, region and local areas and individual characteristics such as age about personal quality of life. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/measuringnationalwellbeing/atwhatageispersonalwellbeingthehighest

Wang, H. X., Karp, A., Winblad, B., & Fratiglioni, L. (2002). Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: A longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155(12), 1081-7. [DOI:10.1093/aje/155.12.1081] [PMID]

Wang, N., Iwasaki, M., Otain, T., Hayashi, R., Miyazaki, H., & Xiao, L., et al. (2005). Perceived health as related to income, socio-economic status, lifestyle, and social support factors in middle aged Japanese. Journal of Epidemiology, 15(5), 155-62. [DOI:10.2188/jea.15.155] [PMID]

Wehrens, R., Putter, H., & Buydens, L. M. C. (2000). The bootstrap: A tutorial. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 54(1), 35-52. [DOI:10.1016/S0169-7439(00)00102-7]

Wilkins, K. (2003). Social support and mortality in seniors. Health Reports , 14(3), 21-34. [PMID]

Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (1995). US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: Patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 349-86. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.so.21.080195.002025]

Yoon, H., Lee, W. S., Kim, K. B., & Moon, J. (2020). Effects of leisure participation on life satisfaction in older Korean adults: A panel analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4402. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124402] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zunzunegui, M. V., Koné, A., Johri, M., Béland, F., Wolfson, C., & Bergman, H. (2004). Social networks and self-rated health in two French-speaking Canadian community dwelling populations over 65. Social Science & Medicine, 58(10), 2069-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.005] [PMID]

General health. Examination of the general health revealed that the majority of older Canadians with disability (57.3%) reported their positive general health and slightly more than half (51.3%) reported positive life satisfaction (Table 4). Results of the multivariate analyses showed significant independent effects of all the study factors on the odds of reporting positive general health, except for sensory disability (Table 5). Of particular note is that respondents who reported a high level of participation in leisure and social activities, had a twice greater odds of reporting positive general health compared with those who did not report participation in any of the leisure or social activities asked on the survey (AOR=2.02 (95%CI=1.27, 3.20)). The odds of reporting positive general health were also significantly reduced by the increased severity of a disability. Our analysis also revealed an important sex difference in one of the predictors of positive general health: Level of income was a significant predictor of general health among women, but not among men.

Life Satisfaction. As shown in Table 6, there were significant associations between life satisfaction and age and sex. Those who were the oldest old (aged 85 years or older) had almost 2.5 times higher odds of reporting being satisfied with their life than those in the younger age group older (AOR=2.47 (95%CI=1.67, 3.64)). Controlling for the effects of all the other factors, men had significantly lower odds of reporting being satisfied with their life (AOR=0.64 (95%CI=0.50, 0.81)). A significant association was also found between life satisfaction and social network, with those having a higher number of friends having increased odds of being satisfied with their life. Moreover, life satisfaction was significantly associated with having a less visible disability, and severity of a disability, such that less visible and more severe disabilities had reduced odds of reporting life satisfaction compared with those with no visible or less severe disabilities. Importantly, a high level of participation in leisure and social activities was found to be significantly associated with increased odds of reporting being satisfied with life among women (AOR=2.62 (95%CI=1.45, 4.75)), but not men (AOR=1.39 (95%CI=0.65, 2.98)).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study was the first study based on a nationally representative sample of older Canadians with disabilities to examine the effects of participation in leisure and social activities on general health and life satisfaction. Although previous research has examined the relationships between social participation and general health or life satisfaction in older populations (Gilmour, 2012; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994) less is known, specifically about the relationships between these factors in older Canadian adults with disabilities. Overall, our findings fill these gaps in knowledge.

Participation in leisure and social activities

We found that 11.7% of older Canadians with disabilities did not participate in any leisure or social activities, and, consistent with previous research (Lee et al., 2008), participation in leisure and social activities also decreased with age. These observed age differences in participation in leisure and social activities may be due to the normal aging or pathological factors. Canadian men also had a slightly higher level of participation in leisure and social activities than did women. This difference might be due to the gendered division of labor within the family. Women’s participation in leisure and social activities may be limited because they take responsibility for more household work than do men. In Canada, this gender gap in household work has been closing, but it is larger for older than younger generations (Mäntyselkä, Turunen, Ahonen & Kumpusalo, 2003).

In the present study, older Canadians with disabilities who lived with others reported higher levels of participation in leisure and social activities compared with those living alone, and as the number of friends increased, participation in leisure and social activities also increased. Previous research has shown a significant relationship between the size of social networks and the level of social participation (Chang, Weay & Lin, 2014). Living with another person may provide a sense of social support and purpose and control over one’s life, which can be particularly crucial for the well-being of people with disabilities (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003; Diehl, 1998; Peat, Thomas, Handy & Croft, 2004). Strong support systems (e.g. having good peer relationships) are especially important for those with disabilities because it may help them cope with their disability, and encourages participation in social activities (Goldberg, Higgins, Raskind & Herman, 2003).

Consistent with previous reports (Conference Board of Canada, 2016), higher income level was significantly associated with higher levels of participation in leisure and social activities among the target population. Persons with disabilities from higher household incomes might be more likely to overcome some of the barriers for participation in leisure and social activities, including those related to transportation expenses, medical and pharmacological expenses, or access to specialized equipment for participation (Shooshtari, Naghipur & Zhang, 2012).

We found significant associations between the level of participation in leisure and social activities with less visible types of disability and the severity of the disability. This is consistent with other research showing that people with aphasia (a language impairment) often report having fewer friends and smaller social networks (Davidson, Howe, Worrall, Hickson & Togher, 2008). The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain (Lethem, Slade, Troup & Bentley, 1983) may help to partly explain these findings. According to this model, fear of embarrassment, discomfort, or pain may result in avoidance of leisure and social activities, and less activity may lead to increased depressive symptoms, which may (in turn) lead to further decreases in participation in activities. In order to promote participation in leisure and social activities, and prevent social isolation (an important risk factor for premature death and other health outcomes in older people (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris & Stephenson, 2015), the specific needs around leisure and social activities of this population must be met. Interestingly, we found that sensory disability was not associated with participation in leisure and social activities.

This may be because many individuals with hearing impairments consider themselves to be a part of the deaf community, which provides a sense of belonging to a large social network (Padden & Humphries, 2005). Thus, even when older adults with vision and hearing impairments report comorbidities, sensory impaired adults were more likely to sustain valued social participation roles compared with their peers without sensory impairments (Cambell, Crews, Moriarty, Zack & Blackman, 1999).

Participation in leisure and social activities and effects on health and well-being

In the present study, satisfaction with life increased with increasing age; a similar positive association was found between general health and age. Previous studies have reported parallel findings (Steel, 2016), even those studies involving older adults with chronic pain (Mäntyselkä et al., 2003; Cleeland & Ryan, 1994; Hunfeld, 2001). Some studies have suggested that when individuals age, their attitudes towards pain (or their general health) change because they consider increased pain (or decreasing general health) to be a natural part of the aging process and may not report problems when surveyed (Jakobsson, Klevsgård, Westergren & Hallberg, 2003). Contrary to other research, we did not find a significant sex difference in the assessment of overall health. Cott, Gignac & Badley (1999) and Zunzunegui et al. (2004) noted that women had a more positive perception of their health and were more satisfied with their life compared with men, even when they suffered from chronic diseases, such as osteoarthritis or chronic pain. These findings indicate that women may have better mechanisms to cope with pain or other health problems.

Living arrangement and size of the social support network were significant factors associated with the study participants’ self-report of general health and life satisfaction. By increasing the number of friends, the likelihood of reported negative health and life satisfaction decreased; however, a plateau effect was observed when examining general health, such that having more than 3-5 friends did not result in increased ratings of positive general health. In a study on self-rated health and social network conducted on two French-speaking communities in Quebec, older Canadians with disabilities who had fewer friends also had higher odds of reporting poor self-rated health (Zunzunegui et al., 2004). Thus, receiving support from friends and family and having a life mate have important positive effects on leisure-time physical activity (Booth, Owen, Bauman, Clavisi & Leslie, 2000; Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2002; Krahn, Fujiura, Drum, Cardinal & Nosek, 2009) and general health (Zunzunegui et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005).

Consistent with other studies (Cott et al., 1999), we found a significant association between the annual income and general health among older Canadians with disabilities. Financial problems can cause stress and anxiety and may reduce access to medical care or social services, both may negatively influence general health and well-being (Williams & Collins, 1995).

Participation in leisure and social activities was found to be an independent determinant of both general health and life satisfaction among older Canadians with disabilities. Those who reported high participation in leisure and social activities had significantly increased odds of reporting positive general health and being satisfied with their life compared with those who did not participate. These results are similar to those reported in previous studies examining general health and satisfaction with life in the general population of seniors (Gilmour, 2012; Riddick & Daniel, 1984; Riddick & Stewart, 1994).

Several limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. First, our analysis was based on cross-sectional data obtained from the PALS 2006; thus, it was not possible to measure changes in the variables of interest for the study population over time or to establish the temporal relationship between variables. Therefore, no causal inferences could be made based on the results. Another limitation relates to the measure of disability itself. Participants were those who self-reported having an activity limitation, which was the basis for classifying individuals with a “disability’. Persons with cognitive or intellectual disabilities might not have a complete understanding of their activity limitations (Statistics Canada, 2006). In contrast, the number of Canadians who reported having mild to severe disability has increased over time (Statistics Canada, 2006), suggesting that Canadians are more accepting of disabilities, this may, in turn, lead to individuals being more comfortable disclosing their disability.

Proxy responding is another source of bias that potentially affected the results of this study. Statistics Canada reported the overall proxy rate for PALS 2006 adult survey at 12.1%26. PALS allowed those who were absent during the time of the survey, could not speak English or French, or could not participate due to mental or physical problems to participate in the survey by proxy responding (Statistics Canada, 2006). The proxy respondent must have had enough knowledge of the individual’s disability and their limitations. Proxy responding is common among adults aged 75 years and older (Statistics Canada, 2006). The PALS master data file did not contain specific information on proxy responding; therefore, it was not possible to investigate the impact of proxy responding to the results of the present study. The PALS data also did not indicate if participants’ responses were made in the presence of another person.

5. Conclusion

There is a great need for more studies based on longitudinal data to monitor the general health and life satisfaction of adults with disabilities as they age. Important data are being collected in this regard. The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), (Zunzunegui et al., 2004) a national-level survey of longitudinal nature, will follow approximately 50,000 men and women between ages of 45 and 85 years for at least 20 years, for providing information on changing biological, medical, psychological, social lifestyle, and economic aspects of older Canadian’s lives. Using the CLSA data, future studies can examine transitions in participation in leisure and social activities in relation to changes in health and life satisfaction over time to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that impede or promote social participation and therefore health and well-being of older Canadians.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed of the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This paper is based on the MSc. thesis of the first author for partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master's degree in Family Social Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari, Karen Duncan, Verena Menec; Methodology: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari; Investigation: Hanieh Chizari; Writing – original draft: Hanieh Chizari; Writing – review & editing: Hanieh Chizari, Shahin Shooshtari, Karen Duncan, Verena Menec; Resources: Shahin Shooshtari; Supervision: Shahin Shooshtari.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Shahin Shooshtari, for her support and guidance throughout the process of this research. I would also like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Karen Duncan and Dr. Verena Menec who provided guidance and supported me with my thesis research project. I also thank Dr. Ian Clara at Manitoba Research Data Centre for his guidance regarding the survey data used and the methods of analysis.

References

Adams, K. B., Leibrandt, S., & Moon, H. (2011). A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing & Society, 31(4), 683-712. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X10001091]

Barnes, L. L., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Wilson, R. S., Bienias, J. L., & Evans, D. A. (2004). Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology, 63(12), 2322-6. [DOI:10.1212/01.WNL.0000147473.04043.B3] [PMID]