Volume 8, Issue 4 (Autumn 2020)

PCP 2020, 8(4): 287-296 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khaleghian A, Sajjadian I, Fatehizade M, Manshaei G. The Mediating Role of Impulsivity and Experiential Avoidance in the Relationship between Emotion Regulation and Pornography Viewing in Married Men. PCP 2020; 8 (4) :287-296

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-646-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-646-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Isfahan, Iran. ,i.sajjadian@khuisf.ac.ir

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Isfahan, Iran. ,

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Isfahan, Iran.

Keywords: Internet pornography viewing, Difficulty, Emotion regulation, Impulsivity, Experiential avoidance

Full-Text [PDF 705 kb]

(1916 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5909 Views)

Full-Text: (1254 Views)

1. Introduction

Internet Pornography Viewing (IPV) has become increasingly prevalent worldwide (Fernandez & Griffiths, 2019); therefore, it has been the subject of numerous scientific studies, especially in the area of marital effects of IPV (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020). Pornography generally refers to any sexually explicit media (videos, websites, magazines, books, etc.) intended to sexually arouse the viewer (Whitehead & Perry, 2018). Findings suggested that using the internet to access pornography was highly correlated with using other forms of pornography, like pornographic magazines or viewing videotapes (Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2001). Excessive IPV is associated with psychological distress, poor social and vocational performance, and family-related and marital dysfunctions (Bothe et al., 2018; Wéry & Billieux, 2017). Some studies have also suggested that pornography use by male partners (especially married ones) provides destructive effects on marital wellbeing by undermining marital relations, decreasing sexual satisfaction and intimacy, and increasing the odds of infidelity and divorce (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Perry, 2017).

The adverse effects of IPV are relatively well documented (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Bothe et al., 2018; Wéry & Billieux, 2017); however, little scholarly attention has been paid to empirically examine the factors affecting the tendency to IPV. In some studies, Emotion Regulation (ER) has been proposed as an intrapersonal characteristic influencing pornography use (Darvish Molla, Shirazi & Nikmanesh, 2018; Laier & brand, 2016; Paul, 2009; Cooper, Delmonico, Griffin Shelley & Mathy, 2004). Previous studies have also indicated that difficulty in ER (e.g. diminishing or inhibiting) is a common factor in problematic sexual behaviors, such as hypersexuality (Reid, Li, Gilliland, Stein & Fong, 2011; Reid & Woolley, 2006) and sexual compulsion (Carvalho, Guerro, Neves & Nobre, 2015). It seems that problematic sexual behaviors (e.g. pornography viewing) present a coping function concerning stressful situations (Laier & Brand, 2014; Reid, et al., 2011; Cooper, et al., 2004). Thus, dysfunctional ER could be considered as a psychological factor influencing the tendency to IPV when experiencing emotional distress. However, there is no clear understanding of the possible underlying mechanisms by which difficulties in ER may influence IPV.

A variable that may link emotion dysregulation and IPV is impulsivity (Bothe et al., 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018). Impulsivity, as a stable personality trait, refers to the tendency to act prematurely and without foresight, regardless of its outcomes (Dalley, Everitt & Robbins, 2011). Impulsivity also conceptualizes as an action toward engaging in pleasurable activities with limited forethought (Grant, Mancebo, Pinto, Eisen, & Rasmussen, 2006). Some researchers described impulsivity as a mode of regulating negative thoughts, feelings, or tendencies through impulsive behaviors (Wetterneck, Burgess, Short, Smith & Cervantes, 2012; Schreiber, Grant, Odlaug, 2012). Impulsivity is among the most frequent personality factors studied concerning problematic sexual behaviors (Walton, Cantor & Lykins, 2017; Raymond, Coleman & Miner, 2003). Some scholars have conceptualized problematic sexual behaviors as impulsivity-related behaviors (e.g. Walton et al., 2017). Impulsivity is also recognized as a predisposing factor for internet-related disorders, such as internet addiction (Zsila, Király & Griffiths, 2017) and the problematic IPV (Bothe et al., 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018; Beyens, Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2015; Wetterneck et al., 2012). Studies revealed that frequent users of internet pornography often describe their consumption as impulsive behavior (Wetterneck et al., 2012). Therefore, it can be expected that impulsivity plays a mediating role between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV.

Experiential avoidance is another variable that has been recognized as associated with IPV (Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin, Lillis & Hayes, 2012). Experiential avoidance is an unwillingness to remain in touch with aversive experiences, like painful thoughts and emotions (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda & Lillis, 2006). Studies reported that experiential avoidance is negatively associated with the ability to regulate emotions and can mediate the effects of ER strategies on mood and distress (Lee, Witte, Weathers & Davis, 2015). Experimental avoidance is also correlated with less adaptive ER strategies, such as avoidance coping, the suppression of thought, low-stress tolerance, and anxiety sensitivity (Wolgast, Lundh, & Viborg, 2013). Some studies reported confirmatory evidence for the link between the use of avoidance-coping strategies and online behavioral addictions, such as the compulsive desire to Facebook use and problematic IPV (Hormes, Kearns & Timko, 2014; Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2012). Moreover, it is suggested that some individuals with hypersexual behaviors use pornography as an emotional avoidance activity (Reid & Woolley, 2006). Therefore, it can be expected that experiential avoidance provides a mediating role in the relationship between the difficulties of ER and the tendency to IPV.

As mentioned above, IPV generates a wide range of adverse outcomes, especially on marital quality (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Perry, 2017); thus, it is necessary to identify the factors that may contribute to it to develop appropriate preventive and treatment strategies in this area. Despite the necessity, limited research has been conducted in this respect, especially in Iran. The literature indicates that most published investigations have been conducted on clinical populations, like individuals with sex and pornography addiction (Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2012); thus, data on the characteristics influencing IPV in the general population are scarce. Moreover, previous studies primarily focused on measuring the frequency of daily or weekly pornography use (Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, & Pargament, 2018); however, craving for pornography as a “transient but intense urge or desire that waxes and wanes over time and as a relatively stable preoccupation or inclination to use pornography” can be considered as a suitable indicator for “a combination of emotional, cognitive, overt behavioral, and physiological elements” concerning pornography use (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). The research findings provide preliminary evidence for possible links between ER and pornography use (Darvish Molla et al., 2018; Paul, 2009; Cooper et al., 2004). However, the psychological constructs mediating the relations between these variables remain unexplored; thus, there is a lack of any model or a network of relations in this regard.

Therefore, the current study aimed to formulate and test the structural model of difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV with the mediating role of impulsivity and experiential avoidance in married men. The reason why the current study focused on married men was because of the devastating effects of IPV on marriage.

2. Methods

To run this research, in September and October 2018, the study participants were invited via several mediums to complete the survey. These mediums comprised advertising banners posted on the 4 most popular social networking applications used in Iran, including Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Soroush. Since IPV might differ between socio-cultural groups (Cooper, Putnam, Planchon, & Boies, 1999), we limited the sampling to participants living in Isfahan City, Iran. The inclusion criteria of this study included being males in the age range of 20-65 years, being married, and living in Isfahan City at the time of the study. No incentives were provided for participation. In the mentioned website, the informed consent form was first obtained from the study subjects. The study participants who failed to respond to all of the questionnaire’s items were excluded from the final data set. The interested participants completed the project questionnaire via the internet (Http://www.cafepardazesh.ir). The initial sample of the online survey consisted of 140 married men. Seventeen participants’ responses with extreme missing data were excluded from the data analysis, resulting in a final sample of 123 research participants. The Mean±SD age of the study participants was 40±10.49 years. The Mean±SD marriage duration of the sample equaled 11.78±10.56 years. In terms of educational level, 35% of the sample reported high school diploma level, 37% Bachelor’s degree, 24% Master’s degree, and 4% PhD.

The Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) is a self-report measure that assesses the current tendency to pornography use (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). It has 12 items rated based on a 7-point Likert-type scale (from completely agree to completely disagree); higher scores indicate greater current craving for pornography use. This questionnaire has good test-retest reliability (r=0.82) and could significantly predict the number of times that male students use pornography during the next week. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for its internal consistency was obtained as 0.91 (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). For this study, we first translated this questionnaire into Persian. Then, it was back-translated into English by the third author and then re-translated into Persian. The questionnaire was completed by 50 students of the University of Isfahan (35 males & 15 females). The relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.93, indicating the desired internal consistency of the questionnaire. For verifying its concurrent validity, we used the Persian version of the Problematic Pornography Use Scale (Darvish Molla & Nikmanesh, 2017). The correlation between these two scales was significantly high (r=0.82). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire in the current study was obtained as 0.95.

The short-form version of the Difficulties in the Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-SF) is a validated tool with extensive use in assessing deficits in ER among adolescents and adults (Kaufman, Xia, Fosco, Yaptangco, Skidmore & Crowell, 2015). Kaufman et al. (2015) indicated correlations between the DERS-SF and the original version (DERS-36) ranging from .90 to .97 and reflecting 81%-96% of shared variance. The related Cronbach’s alpha coefficients have been reported to range from 0.79 to 0.91 (Kaufman, et al., 2015). The scale has 15 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from almost never to almost always); higher scores indicate further difficulties in ER. For this study, we first translated this questionnaire into Persian. Then, it was back-translated into English by the third author, and subsequently, re-translated into Persian. The questionnaire was completed by 60 students of the University of Isfahan (30 males & 30 females). The obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for it was reported as 0.90, reflecting the favorable internal consistency of the questionnaire. For verifying its concurrent validity, we used the Persian version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Besharat & Bazzazian, 2014). Correlations between DERS-SF and maladaptive and adaptive cognitive ER strategies were significantly high (r=0.87 & r=-0.85, respectively). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire in the current study was calculated as 0.94.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) was used for measuring experiential avoidance (Bond et al., 2011). The AAQ-II has 10 items rated based on a 7-point Likert-type scale (from never true to always true); higher scores reflect greater tendencies to experiential avoidance and less psychological flexibility. This scale has demonstrated appropriate construct and discriminant validity, and an internal consistency of α=0.83, and test-retest reliability over three months of r=0.80 (Bond et al., 2011). The Persian version of this scale illustrated significant correlations with the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The related Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.71 to 0.89 (Abbasi, Fata, Molavi, zarabi, 2012). In the current study, the relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was obtained to be 0.91.

The short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15) is among the most commonly used inventories to measure impulsive behaviors in healthy and neuropsychiatric populations (Spinella, 2007). Spinella (2007) reported that BIS-15 has good reliability and validity in a community sample (n=700) with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79. In Spinella (2007)’s study, there were strong relationships between the scores of BIS-15 and the complete version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-II). The questionnaire was completed by 45 students of the University of Isfahan (30 males & 15 females). The obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.91, highlighting the desirable internal consistency of the questionnaire. The correlation between BIS-15 and the Persian versions of BIS-II (Ekhtiari et al., 2008) was measured as 0.89. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed to be 0.93.

Given the small sample size, we used the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique. According to Wong (2013), PLS-SEM is useful for SEM, especially when there are limited participants and the data distribution is skewed. Based on the guidelines suggested by Marcoulides and Saunders (2006), the minimum sample size required for the hypothesized model in the current study was equal to 65. Prior research also suggested that a sample size of 100 to 200 is usually an appropriate starting point in performing path modeling by PLS-SEM (Hoyle, 1995).

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS by descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) and correlation tests. For analyzing the study model, the PLS-SEM technique was performed in WarpPLS.

3. Results

The correlation matrix of the Mean±SD scores of the investigated variables is presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

According to Table 1, the Mean±SD scores of the tendency to IPV, impulsivity, experiential avoidance, and difficulties in ER were 56.32±22.85, 39.36±7.45, 45.17±13.70, and 62.34±13.98, respectively.

Difficulties in ER was positively correlated with impulsivity and experiential avoidance (P<0.01). Additionally, there were significant positive relationships between the tendency to IPV and difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance (P<0.01). In Table 2, the fit indicators are presented.

.jpg)

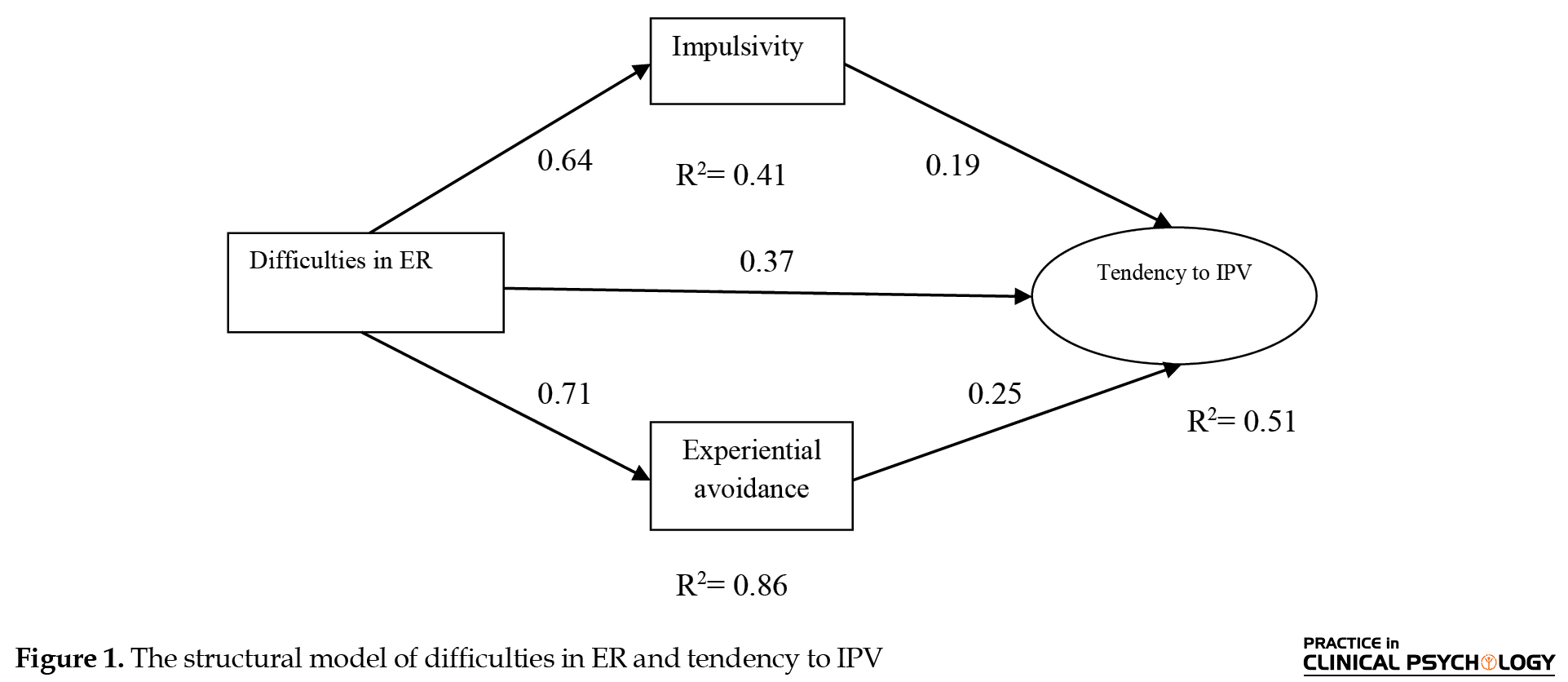

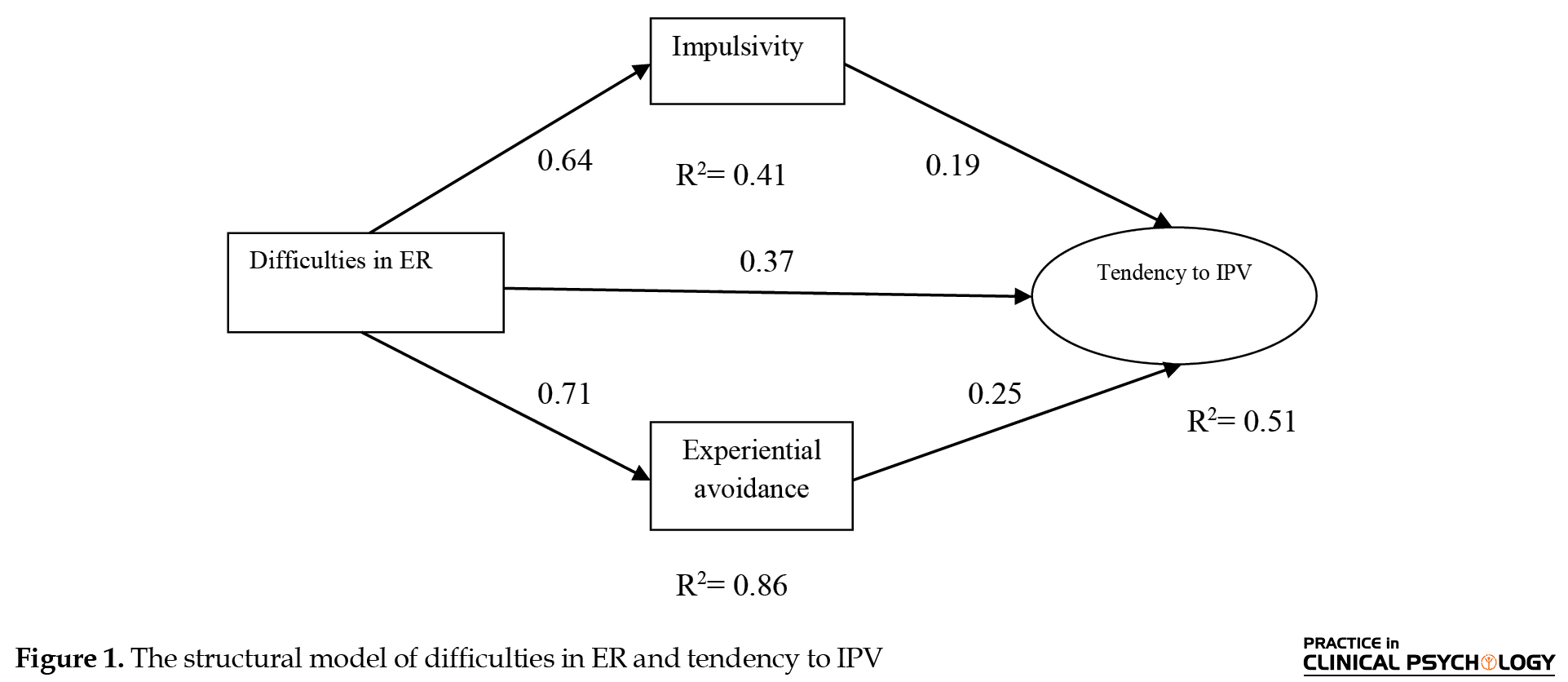

The relevant results suggested that all of the fit indices had a good fit with the data in the hypothesized model. Figure 1 shows the model and path coefficients (β) between the explored variables. The model represents a positive direct effect of the difficulties in ER on the tendency to IPV (β=0.37, P<0.01), impulsivity (β=0.64, P<0.01), and experiential avoidance (β=0.71, P<0.01).

Moreover, there were positive direct effects of impulsivity (β=0.19, P<0.01) and experiential avoidance (β=0.25, P<0.01) on the tendency to IPV (Figure 1). The direct, indirect, and total effect coefficients of difficulties in ER, experiential avoidance, and impulsivity on the tendency to IPV are presented in Table 3.

.jpg)

According to Table 3, the difficulties in bother presented positive direct and indirect effects on the tendency to IPV with the mediating role of impulsivity and experiential avoidance.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the direct and indirect effects of difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance on the tendency to IPV, as an SEM approach. The final model indicated that the values of indices were desirable and the model had a good fit with the collected data. The achieved results indicated that difficulties in the ER were positively associated with the tendency to IPV. These results were consistent with those of the previous studies (Darvish Molla et al., 2018; Laier & brand, 2016; Laier & Brand, 2014; Paul, 2009; Cooper et al., 2004). Other studies also demonstrated that difficulties in ER play an essential role in problematic sexual behaviors, such as hypersexuality and sexual compulsion (Carvalho et al; 2015; Reid et al; 2011; Reid & Woolley, 2006). Some problematic sexual behaviors seem to pursue two main functions, including generating pleasure and reducing inner emotional distress. In other words, some individuals use these sexual behaviors as a means of escaping from anxiety, exhaustion, and other psychological distress, or as a form of self-soothing. Thus, it is plausible that maladaptive emotional responses, as well as, the lack of ER skills during experiencing uncomfortable emotions, play considerable roles in craving for pornography use. In the case of IPV, the characteristics of the media, such as anonymity and accessibility (Cooper et al., 2004), and the expectancy that using internet applications is beneficial to cope with distress or abnormal mood (Laier & brand, 2016) are essential factors in choosing a certain internet application, like internet pornography for coping with aversive feelings.

The current research results revealed that impulsivity plays a direct effect on the tendency to IPV as well as a mediating role between difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV. Accordingly, with the increase in impulsivity, a tendency to IPV also increases. Other studies have also found that motivations for using pornography are positively related to impulsivity (Bothe et al, 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018; Beyens et al., 2015; Wetterneck et al., 2012; Reid et al., 2011). Given that the previous studies mainly investigated how impulsivity relates to problematic pornography use, the present study findings demonstrated that high impulsivity is also related to a high craving for IPV in non-clinical populations. A possible explanation for this finding might be that when individuals with high impulsivity are exposed to opportunities for sexual gratification, IPV-induced impulsively provides them with immediate pleasure. Thus, IPV may initially begin with an impulsive use for achieving an instant pleasure or seeking novel and varied sexual sensations. With regard to ER, impulsive behaviors may apply for distracting and diverting the individual’s attention from experiencing anxiety, boredom, or stress. Evidence suggests that in distressing situations, individuals with difficulty in ER tend to focus on short-term outcomes and follow whatever impulsively for a better feeling at that moment (Tice, Bratslavsky & Baumeister, 2001).

The current research results indicated that experiential avoidance presents a direct effect on the tendency to IPV as well as a mediating role between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV. Accordingly, with increases of experiential avoidance, a tendency to IPV also increases. Other studies have also revealed that the most common reasons for individuals to engage in problematic IPV are related to experiential avoidance (Levin et al., 2012; Wetterneck et al., 2012), and avoiding unpleasant states might be a significant motivation for IPV (Reid, et al; 2011). It seems that some individuals with deficits in the ER may use IPV as an emotional avoidance activity. In other words, the mood-altering experience provided by IPV can offer an escape from stressful experiences (Paul, 2009). Furthermore, excessive use of avoidance for coping with unpleasant experiences may paradoxically increase negative emotions over time and cause greater suffering. Using IPV to avoid aversive emotions acts as a negative reinforcement and this process can remain constant (Levin et al; 2012). The reasons why one chooses IPV instead of other avoidance behaviors (e.g. smoking, using drugs and alcohol, or engaging in other sexual activities) require further investigations.

In sum, the present research findings, in line with previous studies, provided further supports for the influential role of ER mechanisms in the tendency to IPV. These results have significant preventive and therapeutic implications. Based on the obtained data, clinicians must assess ER repertoires of clients engaging in IPV to examine whether they foster maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as impulsive behavior or avoidance strategies in coping with aversive affective states (Schreiber et al., 2012). From a prevention perspective, early identification of difficulties in ER and instructing these groups about healthy coping skills for managing adverse situations can effectively reduce the incidence and prevalence of numerous psychological problems, like excessive IPV. Moreover, the therapeutic interventions that target ER strategies (e.g. acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based interventions) may help clients adopt effective and functional strategies for managing difficult emotions while maintaining their emotional wellbeing (Fraumeni-McBride, 2019). Future research could investigate the effectiveness of such interventions on the reduction of tendency to IPV.

The present research variables were measured by self-report questionnaires, which can increase the odds of bias. It is recommended that qualitative studies be conducted for a deeper investigation of the intra- and inter-personal dynamics of pornography users. Such measures could help to achieve a more clear understanding of underlying mechanisms that influence the tendency to IPV. Considering that this research was conducted on a small sample of married men living in Isfahan City, the generalization of the obtained findings has some limitations. The current study only addressed IPV; therefore, the collected data may be not generalizable to other forms of pornography use. It is also suggested that future research investigate the mediating role of other factors, such as personality traits (e.g. extraversion, openness to experience, neuroticism, etc.), sexual sensation seeking, and attachment security in exploring the relationship between difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV.

5. Conclusion

The current study data indicated that difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance play important roles in the tendency to IPV in married men. Impulsivity and experiential avoidance, as two styles of ER, can mediate the relationship between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV. Studying these variables are effective methods in understanding the underlying factors associated with IPV, and developing clinical guidelines in working with individuals involved in pornography use.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed of the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

The current study is a part of the PhD. dissertation of the first author at Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Abbasi, I., Fata, L., Molavi, R., & Zarabi, H. (2012). [Psychometric properties of the Acceptance & Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Methods and Models, 2(10), 65-80. Link Not Found.

Antons, S., Brand, M. (2018). Trait and state impulsivity in males with tendency towards Internet -pornography-use disorder. Addictive Behavior, 79, 171-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.029] [PMID]

Besharat, M. A., Bazzazian, S. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in a sample of Iranian population. Advanced in Nursing & Midwifery, 24(84), 61-70. [DOI:10.1080/02699930701369035]

Beyens, I., Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Early adolescent boys’ exposure to Internet pornography relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35, 1045-68. [DOI:10.1177/0272431614548069]

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., & Orcutt, H. K., et al. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676-88. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007] [PMID]

Bothe, B., Bartók, R., Tóth-Király, I., Reid, R. C., Griiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z., et al. (2018). Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2265-76. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z] [PMID]

Bothe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Zsila, Á., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). The development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS). Journal of Sex Research, 55, 395-406. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1291798] [PMID]

Carvalho, J., Guerra, L., Neves, S., & Nobre, P. J. (2015). Psychopathological predictors characterizing sexual compulsivity in a nonclinical sample of women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41, 467-80. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2014.920755] [PMID]

Collins, R. L., Strasburger, V. C., Brown, J. D., Donnerstein, E., Lenhart, A., & Ward, L. M. (2017). Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement 2), S162-S166. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-1758X] [PMID]

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., Griffin Shelley, E., & Mathy, R. M. (2004). Online sexual activity: An examination of potentially problematic behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(3), 129-43. [DOI:10.1080/10720160490882642]

Cooper, A., Putnam, D. E., Planchon, L. A., & Boies, S. C. (1999) Online sexual compulsivity: Getting tangled in the net, Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 6(2), 79-104, [DOI:10.1080/10720169908400182]

Dalley, J. W., Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron, 69(4), 680-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.020] [PMID]

Darvish Molla, M., Nikmanesh, Z. (2017). [Psychometric properties of the Persian version of problematic pornography use scale (pornography addiction) (Persian)]. Psychological Models and Methods, 8(27), 49-63. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=542385

Darvish Molla, M., Shirazi, M., & Nikmanesh, Z. (2018). [The role of difficulties in emotion regulation and thought control strategies on pornography use (Persian)]. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology, 6(2), 119-28. [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.6.2.119]

Egan, V., & Parmar, R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(5), 394-409. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2012.710182] [PMID]

Ekhtiari, H., Safaei, H., Esmaeeli Djavid, GH., Atefvahid, M. K., Edalati, H., & Mokri, A. (2008). [Reliability and validity of persian versions of eysenck, barratt, dickman and zuckerman questionnaires in assessing risky and impulsive behaviors (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 14(3), 326-36. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-575-en.html

Fernandez, D. P., Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: A systematic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 1-17. [DOI:10.1177/0163278719861688] [PMID]

Fraumeni-McBride, J. (2019). Addiction and mindfulness; pornography addiction and mindfulness-based therapy ACT. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(1-2), 42-53. [DOI:10.1080/10720162.2019.1576560]

García-oliva, C., & Piqueras, J. (2016). Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 293-303. [DOI:10.1556/2006.5.2016.041] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2001). Searching for sexually explicit material on the Internet: An exploratory study of college students’ behavior and attitudes. Archives of sexual Behavior, 30(2), 101-17. [DOI:10.1023/A:1002724116437] [PMID]

Grant, J. E., Mancebo, M. C., Pinto, A., Eisen, J. L., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2006). Impulse control disorders in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(6), 494-501.[DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.11.005] [PMID]

Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I. (2018). Predicting pornography use over time: Does self-reported "addiction" matter? Addictive Behaviors, 82, 57-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.028] [PMID]

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1-25. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006] [PMID]

Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109(12), 2079-2088. [DOI:10.1111/add.12713] [PMID]

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kaufman, E. A., Skidmore, C. R., Xia, M., Fosco, G., Crowell, S. E. (2015). The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF): Validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 38(3), 443-55. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3]

Kraus, S., & Rosenberg, H. (2014).The pornography craving questionnaire: Psychometric properties. Archive Sex Behaviours, 43(3), 451-462. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3] [PMID]

Laier, C., & Brand, M. (2014). Empirical evidence and theoretical considerations on factors contributing to cybersex addiction from a cognitive-behavioral view. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21(4), 305-21. [DOI:10.1080/10720162.2014.970722]

Laier, C., & Brand, M. (2016). Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 5, 9-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.abrep.2016.11.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

Lee, D. J., Witte, T. K., Weathers, F. W., & Davis, M. T. (2015). Emotion regulation strategy use and posttraumatic stress disorder: associations between multiple strategies and specific symptom clusters. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 37(3), 533-44. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-014-9477-3]

Leonhardt, N. D., & Willoughby, B. J. (2019). Pornography, provocative sexual media, and their differing associations with multiple aspects of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(2), 618-41. [DOI:10.1177/0265407517739162]

Levin, M. E., Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2012). When is online pornography viewing problematic among college males? Examining the moderating role of experiential avoidance. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19(3), 168-80. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10720162.2012.657150

Marcoulides, G. A., & Saunders, C. (2006). Editor’s Comments - PLS: A silver bullet? MIS Quarterly, 30(2), iii-ix. [DOI:10.2307/25148727]

McKee, A. (2010). Does pornography harm young people? Australian Journal of Communication, 37(1), 17-36. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/41858/

Paul, B. (2009). Predicting Internet pornography use and arousal: The role of individual difference variables. Journal of Sex Research, 46(4), 344-57. [DOI:10.1080/00224490902754152] [PMID]

Perry, S. (2017). Does viewing pornography reduce marital quality overtime? Evidence from longitudinal data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 549-59. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-016-0770-y] [PMID]

Perry, S. L. (2020). Is the link between pornography use and relational happiness really more about masturbation? Results from two national surveys. Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), 64-76. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2018.1556772] [PMID]

Raymond, N. C., Coleman, E., & Miner, M. H. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(5), 370–80. [DOI:10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X] [PMID]

Reid, R. C., Li, D. S., Gilliland, R., Stein, J. A., & Fong, T. (2011). Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the pornography consumption inventory in a sample of hypersexual men. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37, 359-85. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2011.607047] [PMID]

Reid, R. C., & Woolley, S. R. (2006). Using emotionally focused therapy for couples to resolve attachment ruptures created by hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13(2-3), 219-39. [DOI:10.1080/10720160600870786]

Schreiber, L. R. N., Grant, J. E., & Odlaug, B. L. (2012). Emotion regulation and impulsivity in young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 651-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

Spinella, M. (2007). Normative data and a short form of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117, 359-68. [DOI:10.1080/00207450600588881] [PMID]

Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it!. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53-67. [DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.53] [PMID]

Walton, M. T., Cantor, J. M., & Lykins, A. D. (2017). An online assessment of personality, psychological, and sexuality trait variables associated with self-reported hypersexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 721-33. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-015-0606-1] [PMID]

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2017). Problematic cybersex: conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 238-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.007] [PMID]

Wetterneck, C. T., Burgess, A. J., Short, M. B., Smith, A. H., & Cervantes, M. E. (2012). The role of sexual compulsivity, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance in Internet pornography use. Psychological Record, 62, 3-18. [DOI:10.1007/BF03395783]

Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S.L. (2018). Unbuckling the Bible belt: a state-level analysis of religious factors and Google searches for porn. Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 273-83. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1278736] [PMID]

Wolgast, M., Lundh, L. G., & Viborg, G. (2013). Experiential avoidance as an emotion regulatory function: an empirical analysis of experiential avoidance in relation to behavioral avoidance, cognitive reappraisal, and response suppression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 2(3), 224-32. [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2013.773059] [PMID]

Wong, K. K. K. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1), 1-32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268449353_

Zsila, A., Orosz, G., Bothe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Király, O., & Griffiths, M., et al. (2017). An empirical study on the motivations underlying augmented reality games: The case of Pokémon go during and after Pokémon fever. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 56-66. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.024]

Internet Pornography Viewing (IPV) has become increasingly prevalent worldwide (Fernandez & Griffiths, 2019); therefore, it has been the subject of numerous scientific studies, especially in the area of marital effects of IPV (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020). Pornography generally refers to any sexually explicit media (videos, websites, magazines, books, etc.) intended to sexually arouse the viewer (Whitehead & Perry, 2018). Findings suggested that using the internet to access pornography was highly correlated with using other forms of pornography, like pornographic magazines or viewing videotapes (Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2001). Excessive IPV is associated with psychological distress, poor social and vocational performance, and family-related and marital dysfunctions (Bothe et al., 2018; Wéry & Billieux, 2017). Some studies have also suggested that pornography use by male partners (especially married ones) provides destructive effects on marital wellbeing by undermining marital relations, decreasing sexual satisfaction and intimacy, and increasing the odds of infidelity and divorce (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Perry, 2017).

The adverse effects of IPV are relatively well documented (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Bothe et al., 2018; Wéry & Billieux, 2017); however, little scholarly attention has been paid to empirically examine the factors affecting the tendency to IPV. In some studies, Emotion Regulation (ER) has been proposed as an intrapersonal characteristic influencing pornography use (Darvish Molla, Shirazi & Nikmanesh, 2018; Laier & brand, 2016; Paul, 2009; Cooper, Delmonico, Griffin Shelley & Mathy, 2004). Previous studies have also indicated that difficulty in ER (e.g. diminishing or inhibiting) is a common factor in problematic sexual behaviors, such as hypersexuality (Reid, Li, Gilliland, Stein & Fong, 2011; Reid & Woolley, 2006) and sexual compulsion (Carvalho, Guerro, Neves & Nobre, 2015). It seems that problematic sexual behaviors (e.g. pornography viewing) present a coping function concerning stressful situations (Laier & Brand, 2014; Reid, et al., 2011; Cooper, et al., 2004). Thus, dysfunctional ER could be considered as a psychological factor influencing the tendency to IPV when experiencing emotional distress. However, there is no clear understanding of the possible underlying mechanisms by which difficulties in ER may influence IPV.

A variable that may link emotion dysregulation and IPV is impulsivity (Bothe et al., 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018). Impulsivity, as a stable personality trait, refers to the tendency to act prematurely and without foresight, regardless of its outcomes (Dalley, Everitt & Robbins, 2011). Impulsivity also conceptualizes as an action toward engaging in pleasurable activities with limited forethought (Grant, Mancebo, Pinto, Eisen, & Rasmussen, 2006). Some researchers described impulsivity as a mode of regulating negative thoughts, feelings, or tendencies through impulsive behaviors (Wetterneck, Burgess, Short, Smith & Cervantes, 2012; Schreiber, Grant, Odlaug, 2012). Impulsivity is among the most frequent personality factors studied concerning problematic sexual behaviors (Walton, Cantor & Lykins, 2017; Raymond, Coleman & Miner, 2003). Some scholars have conceptualized problematic sexual behaviors as impulsivity-related behaviors (e.g. Walton et al., 2017). Impulsivity is also recognized as a predisposing factor for internet-related disorders, such as internet addiction (Zsila, Király & Griffiths, 2017) and the problematic IPV (Bothe et al., 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018; Beyens, Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2015; Wetterneck et al., 2012). Studies revealed that frequent users of internet pornography often describe their consumption as impulsive behavior (Wetterneck et al., 2012). Therefore, it can be expected that impulsivity plays a mediating role between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV.

Experiential avoidance is another variable that has been recognized as associated with IPV (Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin, Lillis & Hayes, 2012). Experiential avoidance is an unwillingness to remain in touch with aversive experiences, like painful thoughts and emotions (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda & Lillis, 2006). Studies reported that experiential avoidance is negatively associated with the ability to regulate emotions and can mediate the effects of ER strategies on mood and distress (Lee, Witte, Weathers & Davis, 2015). Experimental avoidance is also correlated with less adaptive ER strategies, such as avoidance coping, the suppression of thought, low-stress tolerance, and anxiety sensitivity (Wolgast, Lundh, & Viborg, 2013). Some studies reported confirmatory evidence for the link between the use of avoidance-coping strategies and online behavioral addictions, such as the compulsive desire to Facebook use and problematic IPV (Hormes, Kearns & Timko, 2014; Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2012). Moreover, it is suggested that some individuals with hypersexual behaviors use pornography as an emotional avoidance activity (Reid & Woolley, 2006). Therefore, it can be expected that experiential avoidance provides a mediating role in the relationship between the difficulties of ER and the tendency to IPV.

As mentioned above, IPV generates a wide range of adverse outcomes, especially on marital quality (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019; Perry, 2020; Perry, 2017); thus, it is necessary to identify the factors that may contribute to it to develop appropriate preventive and treatment strategies in this area. Despite the necessity, limited research has been conducted in this respect, especially in Iran. The literature indicates that most published investigations have been conducted on clinical populations, like individuals with sex and pornography addiction (Wetterneck et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2012); thus, data on the characteristics influencing IPV in the general population are scarce. Moreover, previous studies primarily focused on measuring the frequency of daily or weekly pornography use (Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, & Pargament, 2018); however, craving for pornography as a “transient but intense urge or desire that waxes and wanes over time and as a relatively stable preoccupation or inclination to use pornography” can be considered as a suitable indicator for “a combination of emotional, cognitive, overt behavioral, and physiological elements” concerning pornography use (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). The research findings provide preliminary evidence for possible links between ER and pornography use (Darvish Molla et al., 2018; Paul, 2009; Cooper et al., 2004). However, the psychological constructs mediating the relations between these variables remain unexplored; thus, there is a lack of any model or a network of relations in this regard.

Therefore, the current study aimed to formulate and test the structural model of difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV with the mediating role of impulsivity and experiential avoidance in married men. The reason why the current study focused on married men was because of the devastating effects of IPV on marriage.

2. Methods

To run this research, in September and October 2018, the study participants were invited via several mediums to complete the survey. These mediums comprised advertising banners posted on the 4 most popular social networking applications used in Iran, including Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Soroush. Since IPV might differ between socio-cultural groups (Cooper, Putnam, Planchon, & Boies, 1999), we limited the sampling to participants living in Isfahan City, Iran. The inclusion criteria of this study included being males in the age range of 20-65 years, being married, and living in Isfahan City at the time of the study. No incentives were provided for participation. In the mentioned website, the informed consent form was first obtained from the study subjects. The study participants who failed to respond to all of the questionnaire’s items were excluded from the final data set. The interested participants completed the project questionnaire via the internet (Http://www.cafepardazesh.ir). The initial sample of the online survey consisted of 140 married men. Seventeen participants’ responses with extreme missing data were excluded from the data analysis, resulting in a final sample of 123 research participants. The Mean±SD age of the study participants was 40±10.49 years. The Mean±SD marriage duration of the sample equaled 11.78±10.56 years. In terms of educational level, 35% of the sample reported high school diploma level, 37% Bachelor’s degree, 24% Master’s degree, and 4% PhD.

The Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) is a self-report measure that assesses the current tendency to pornography use (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). It has 12 items rated based on a 7-point Likert-type scale (from completely agree to completely disagree); higher scores indicate greater current craving for pornography use. This questionnaire has good test-retest reliability (r=0.82) and could significantly predict the number of times that male students use pornography during the next week. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for its internal consistency was obtained as 0.91 (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). For this study, we first translated this questionnaire into Persian. Then, it was back-translated into English by the third author and then re-translated into Persian. The questionnaire was completed by 50 students of the University of Isfahan (35 males & 15 females). The relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.93, indicating the desired internal consistency of the questionnaire. For verifying its concurrent validity, we used the Persian version of the Problematic Pornography Use Scale (Darvish Molla & Nikmanesh, 2017). The correlation between these two scales was significantly high (r=0.82). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire in the current study was obtained as 0.95.

The short-form version of the Difficulties in the Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-SF) is a validated tool with extensive use in assessing deficits in ER among adolescents and adults (Kaufman, Xia, Fosco, Yaptangco, Skidmore & Crowell, 2015). Kaufman et al. (2015) indicated correlations between the DERS-SF and the original version (DERS-36) ranging from .90 to .97 and reflecting 81%-96% of shared variance. The related Cronbach’s alpha coefficients have been reported to range from 0.79 to 0.91 (Kaufman, et al., 2015). The scale has 15 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from almost never to almost always); higher scores indicate further difficulties in ER. For this study, we first translated this questionnaire into Persian. Then, it was back-translated into English by the third author, and subsequently, re-translated into Persian. The questionnaire was completed by 60 students of the University of Isfahan (30 males & 30 females). The obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for it was reported as 0.90, reflecting the favorable internal consistency of the questionnaire. For verifying its concurrent validity, we used the Persian version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Besharat & Bazzazian, 2014). Correlations between DERS-SF and maladaptive and adaptive cognitive ER strategies were significantly high (r=0.87 & r=-0.85, respectively). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire in the current study was calculated as 0.94.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) was used for measuring experiential avoidance (Bond et al., 2011). The AAQ-II has 10 items rated based on a 7-point Likert-type scale (from never true to always true); higher scores reflect greater tendencies to experiential avoidance and less psychological flexibility. This scale has demonstrated appropriate construct and discriminant validity, and an internal consistency of α=0.83, and test-retest reliability over three months of r=0.80 (Bond et al., 2011). The Persian version of this scale illustrated significant correlations with the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The related Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.71 to 0.89 (Abbasi, Fata, Molavi, zarabi, 2012). In the current study, the relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was obtained to be 0.91.

The short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15) is among the most commonly used inventories to measure impulsive behaviors in healthy and neuropsychiatric populations (Spinella, 2007). Spinella (2007) reported that BIS-15 has good reliability and validity in a community sample (n=700) with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79. In Spinella (2007)’s study, there were strong relationships between the scores of BIS-15 and the complete version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-II). The questionnaire was completed by 45 students of the University of Isfahan (30 males & 15 females). The obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.91, highlighting the desirable internal consistency of the questionnaire. The correlation between BIS-15 and the Persian versions of BIS-II (Ekhtiari et al., 2008) was measured as 0.89. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed to be 0.93.

Given the small sample size, we used the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique. According to Wong (2013), PLS-SEM is useful for SEM, especially when there are limited participants and the data distribution is skewed. Based on the guidelines suggested by Marcoulides and Saunders (2006), the minimum sample size required for the hypothesized model in the current study was equal to 65. Prior research also suggested that a sample size of 100 to 200 is usually an appropriate starting point in performing path modeling by PLS-SEM (Hoyle, 1995).

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS by descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) and correlation tests. For analyzing the study model, the PLS-SEM technique was performed in WarpPLS.

3. Results

The correlation matrix of the Mean±SD scores of the investigated variables is presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

According to Table 1, the Mean±SD scores of the tendency to IPV, impulsivity, experiential avoidance, and difficulties in ER were 56.32±22.85, 39.36±7.45, 45.17±13.70, and 62.34±13.98, respectively.

Difficulties in ER was positively correlated with impulsivity and experiential avoidance (P<0.01). Additionally, there were significant positive relationships between the tendency to IPV and difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance (P<0.01). In Table 2, the fit indicators are presented.

.jpg)

The relevant results suggested that all of the fit indices had a good fit with the data in the hypothesized model. Figure 1 shows the model and path coefficients (β) between the explored variables. The model represents a positive direct effect of the difficulties in ER on the tendency to IPV (β=0.37, P<0.01), impulsivity (β=0.64, P<0.01), and experiential avoidance (β=0.71, P<0.01).

Moreover, there were positive direct effects of impulsivity (β=0.19, P<0.01) and experiential avoidance (β=0.25, P<0.01) on the tendency to IPV (Figure 1). The direct, indirect, and total effect coefficients of difficulties in ER, experiential avoidance, and impulsivity on the tendency to IPV are presented in Table 3.

.jpg)

According to Table 3, the difficulties in bother presented positive direct and indirect effects on the tendency to IPV with the mediating role of impulsivity and experiential avoidance.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the direct and indirect effects of difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance on the tendency to IPV, as an SEM approach. The final model indicated that the values of indices were desirable and the model had a good fit with the collected data. The achieved results indicated that difficulties in the ER were positively associated with the tendency to IPV. These results were consistent with those of the previous studies (Darvish Molla et al., 2018; Laier & brand, 2016; Laier & Brand, 2014; Paul, 2009; Cooper et al., 2004). Other studies also demonstrated that difficulties in ER play an essential role in problematic sexual behaviors, such as hypersexuality and sexual compulsion (Carvalho et al; 2015; Reid et al; 2011; Reid & Woolley, 2006). Some problematic sexual behaviors seem to pursue two main functions, including generating pleasure and reducing inner emotional distress. In other words, some individuals use these sexual behaviors as a means of escaping from anxiety, exhaustion, and other psychological distress, or as a form of self-soothing. Thus, it is plausible that maladaptive emotional responses, as well as, the lack of ER skills during experiencing uncomfortable emotions, play considerable roles in craving for pornography use. In the case of IPV, the characteristics of the media, such as anonymity and accessibility (Cooper et al., 2004), and the expectancy that using internet applications is beneficial to cope with distress or abnormal mood (Laier & brand, 2016) are essential factors in choosing a certain internet application, like internet pornography for coping with aversive feelings.

The current research results revealed that impulsivity plays a direct effect on the tendency to IPV as well as a mediating role between difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV. Accordingly, with the increase in impulsivity, a tendency to IPV also increases. Other studies have also found that motivations for using pornography are positively related to impulsivity (Bothe et al, 2018; Antons & Brand, 2018; Beyens et al., 2015; Wetterneck et al., 2012; Reid et al., 2011). Given that the previous studies mainly investigated how impulsivity relates to problematic pornography use, the present study findings demonstrated that high impulsivity is also related to a high craving for IPV in non-clinical populations. A possible explanation for this finding might be that when individuals with high impulsivity are exposed to opportunities for sexual gratification, IPV-induced impulsively provides them with immediate pleasure. Thus, IPV may initially begin with an impulsive use for achieving an instant pleasure or seeking novel and varied sexual sensations. With regard to ER, impulsive behaviors may apply for distracting and diverting the individual’s attention from experiencing anxiety, boredom, or stress. Evidence suggests that in distressing situations, individuals with difficulty in ER tend to focus on short-term outcomes and follow whatever impulsively for a better feeling at that moment (Tice, Bratslavsky & Baumeister, 2001).

The current research results indicated that experiential avoidance presents a direct effect on the tendency to IPV as well as a mediating role between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV. Accordingly, with increases of experiential avoidance, a tendency to IPV also increases. Other studies have also revealed that the most common reasons for individuals to engage in problematic IPV are related to experiential avoidance (Levin et al., 2012; Wetterneck et al., 2012), and avoiding unpleasant states might be a significant motivation for IPV (Reid, et al; 2011). It seems that some individuals with deficits in the ER may use IPV as an emotional avoidance activity. In other words, the mood-altering experience provided by IPV can offer an escape from stressful experiences (Paul, 2009). Furthermore, excessive use of avoidance for coping with unpleasant experiences may paradoxically increase negative emotions over time and cause greater suffering. Using IPV to avoid aversive emotions acts as a negative reinforcement and this process can remain constant (Levin et al; 2012). The reasons why one chooses IPV instead of other avoidance behaviors (e.g. smoking, using drugs and alcohol, or engaging in other sexual activities) require further investigations.

In sum, the present research findings, in line with previous studies, provided further supports for the influential role of ER mechanisms in the tendency to IPV. These results have significant preventive and therapeutic implications. Based on the obtained data, clinicians must assess ER repertoires of clients engaging in IPV to examine whether they foster maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as impulsive behavior or avoidance strategies in coping with aversive affective states (Schreiber et al., 2012). From a prevention perspective, early identification of difficulties in ER and instructing these groups about healthy coping skills for managing adverse situations can effectively reduce the incidence and prevalence of numerous psychological problems, like excessive IPV. Moreover, the therapeutic interventions that target ER strategies (e.g. acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based interventions) may help clients adopt effective and functional strategies for managing difficult emotions while maintaining their emotional wellbeing (Fraumeni-McBride, 2019). Future research could investigate the effectiveness of such interventions on the reduction of tendency to IPV.

The present research variables were measured by self-report questionnaires, which can increase the odds of bias. It is recommended that qualitative studies be conducted for a deeper investigation of the intra- and inter-personal dynamics of pornography users. Such measures could help to achieve a more clear understanding of underlying mechanisms that influence the tendency to IPV. Considering that this research was conducted on a small sample of married men living in Isfahan City, the generalization of the obtained findings has some limitations. The current study only addressed IPV; therefore, the collected data may be not generalizable to other forms of pornography use. It is also suggested that future research investigate the mediating role of other factors, such as personality traits (e.g. extraversion, openness to experience, neuroticism, etc.), sexual sensation seeking, and attachment security in exploring the relationship between difficulties in ER and tendency to IPV.

5. Conclusion

The current study data indicated that difficulties in ER, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance play important roles in the tendency to IPV in married men. Impulsivity and experiential avoidance, as two styles of ER, can mediate the relationship between difficulties in ER and the tendency to IPV. Studying these variables are effective methods in understanding the underlying factors associated with IPV, and developing clinical guidelines in working with individuals involved in pornography use.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed of the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

The current study is a part of the PhD. dissertation of the first author at Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Abbasi, I., Fata, L., Molavi, R., & Zarabi, H. (2012). [Psychometric properties of the Acceptance & Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Methods and Models, 2(10), 65-80. Link Not Found.

Antons, S., Brand, M. (2018). Trait and state impulsivity in males with tendency towards Internet -pornography-use disorder. Addictive Behavior, 79, 171-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.029] [PMID]

Besharat, M. A., Bazzazian, S. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in a sample of Iranian population. Advanced in Nursing & Midwifery, 24(84), 61-70. [DOI:10.1080/02699930701369035]

Beyens, I., Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Early adolescent boys’ exposure to Internet pornography relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35, 1045-68. [DOI:10.1177/0272431614548069]

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., & Orcutt, H. K., et al. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676-88. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007] [PMID]

Bothe, B., Bartók, R., Tóth-Király, I., Reid, R. C., Griiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z., et al. (2018). Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2265-76. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z] [PMID]

Bothe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Zsila, Á., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). The development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS). Journal of Sex Research, 55, 395-406. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1291798] [PMID]

Carvalho, J., Guerra, L., Neves, S., & Nobre, P. J. (2015). Psychopathological predictors characterizing sexual compulsivity in a nonclinical sample of women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41, 467-80. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2014.920755] [PMID]

Collins, R. L., Strasburger, V. C., Brown, J. D., Donnerstein, E., Lenhart, A., & Ward, L. M. (2017). Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement 2), S162-S166. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-1758X] [PMID]

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., Griffin Shelley, E., & Mathy, R. M. (2004). Online sexual activity: An examination of potentially problematic behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(3), 129-43. [DOI:10.1080/10720160490882642]

Cooper, A., Putnam, D. E., Planchon, L. A., & Boies, S. C. (1999) Online sexual compulsivity: Getting tangled in the net, Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 6(2), 79-104, [DOI:10.1080/10720169908400182]

Dalley, J. W., Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron, 69(4), 680-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.020] [PMID]

Darvish Molla, M., Nikmanesh, Z. (2017). [Psychometric properties of the Persian version of problematic pornography use scale (pornography addiction) (Persian)]. Psychological Models and Methods, 8(27), 49-63. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=542385

Darvish Molla, M., Shirazi, M., & Nikmanesh, Z. (2018). [The role of difficulties in emotion regulation and thought control strategies on pornography use (Persian)]. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology, 6(2), 119-28. [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.6.2.119]

Egan, V., & Parmar, R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(5), 394-409. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2012.710182] [PMID]

Ekhtiari, H., Safaei, H., Esmaeeli Djavid, GH., Atefvahid, M. K., Edalati, H., & Mokri, A. (2008). [Reliability and validity of persian versions of eysenck, barratt, dickman and zuckerman questionnaires in assessing risky and impulsive behaviors (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 14(3), 326-36. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-575-en.html

Fernandez, D. P., Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: A systematic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 1-17. [DOI:10.1177/0163278719861688] [PMID]

Fraumeni-McBride, J. (2019). Addiction and mindfulness; pornography addiction and mindfulness-based therapy ACT. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(1-2), 42-53. [DOI:10.1080/10720162.2019.1576560]

García-oliva, C., & Piqueras, J. (2016). Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 293-303. [DOI:10.1556/2006.5.2016.041] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2001). Searching for sexually explicit material on the Internet: An exploratory study of college students’ behavior and attitudes. Archives of sexual Behavior, 30(2), 101-17. [DOI:10.1023/A:1002724116437] [PMID]

Grant, J. E., Mancebo, M. C., Pinto, A., Eisen, J. L., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2006). Impulse control disorders in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(6), 494-501.[DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.11.005] [PMID]

Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I. (2018). Predicting pornography use over time: Does self-reported "addiction" matter? Addictive Behaviors, 82, 57-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.028] [PMID]

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1-25. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006] [PMID]

Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109(12), 2079-2088. [DOI:10.1111/add.12713] [PMID]

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kaufman, E. A., Skidmore, C. R., Xia, M., Fosco, G., Crowell, S. E. (2015). The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF): Validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 38(3), 443-55. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3]

Kraus, S., & Rosenberg, H. (2014).The pornography craving questionnaire: Psychometric properties. Archive Sex Behaviours, 43(3), 451-462. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3] [PMID]

Laier, C., & Brand, M. (2014). Empirical evidence and theoretical considerations on factors contributing to cybersex addiction from a cognitive-behavioral view. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21(4), 305-21. [DOI:10.1080/10720162.2014.970722]

Laier, C., & Brand, M. (2016). Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 5, 9-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.abrep.2016.11.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

Lee, D. J., Witte, T. K., Weathers, F. W., & Davis, M. T. (2015). Emotion regulation strategy use and posttraumatic stress disorder: associations between multiple strategies and specific symptom clusters. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 37(3), 533-44. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-014-9477-3]

Leonhardt, N. D., & Willoughby, B. J. (2019). Pornography, provocative sexual media, and their differing associations with multiple aspects of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(2), 618-41. [DOI:10.1177/0265407517739162]

Levin, M. E., Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2012). When is online pornography viewing problematic among college males? Examining the moderating role of experiential avoidance. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19(3), 168-80. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10720162.2012.657150

Marcoulides, G. A., & Saunders, C. (2006). Editor’s Comments - PLS: A silver bullet? MIS Quarterly, 30(2), iii-ix. [DOI:10.2307/25148727]

McKee, A. (2010). Does pornography harm young people? Australian Journal of Communication, 37(1), 17-36. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/41858/

Paul, B. (2009). Predicting Internet pornography use and arousal: The role of individual difference variables. Journal of Sex Research, 46(4), 344-57. [DOI:10.1080/00224490902754152] [PMID]

Perry, S. (2017). Does viewing pornography reduce marital quality overtime? Evidence from longitudinal data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 549-59. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-016-0770-y] [PMID]

Perry, S. L. (2020). Is the link between pornography use and relational happiness really more about masturbation? Results from two national surveys. Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), 64-76. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2018.1556772] [PMID]

Raymond, N. C., Coleman, E., & Miner, M. H. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(5), 370–80. [DOI:10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X] [PMID]

Reid, R. C., Li, D. S., Gilliland, R., Stein, J. A., & Fong, T. (2011). Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the pornography consumption inventory in a sample of hypersexual men. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37, 359-85. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2011.607047] [PMID]

Reid, R. C., & Woolley, S. R. (2006). Using emotionally focused therapy for couples to resolve attachment ruptures created by hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13(2-3), 219-39. [DOI:10.1080/10720160600870786]

Schreiber, L. R. N., Grant, J. E., & Odlaug, B. L. (2012). Emotion regulation and impulsivity in young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 651-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

Spinella, M. (2007). Normative data and a short form of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117, 359-68. [DOI:10.1080/00207450600588881] [PMID]

Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it!. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53-67. [DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.53] [PMID]

Walton, M. T., Cantor, J. M., & Lykins, A. D. (2017). An online assessment of personality, psychological, and sexuality trait variables associated with self-reported hypersexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 721-33. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-015-0606-1] [PMID]

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2017). Problematic cybersex: conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 238-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.007] [PMID]

Wetterneck, C. T., Burgess, A. J., Short, M. B., Smith, A. H., & Cervantes, M. E. (2012). The role of sexual compulsivity, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance in Internet pornography use. Psychological Record, 62, 3-18. [DOI:10.1007/BF03395783]

Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S.L. (2018). Unbuckling the Bible belt: a state-level analysis of religious factors and Google searches for porn. Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 273-83. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2017.1278736] [PMID]

Wolgast, M., Lundh, L. G., & Viborg, G. (2013). Experiential avoidance as an emotion regulatory function: an empirical analysis of experiential avoidance in relation to behavioral avoidance, cognitive reappraisal, and response suppression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 2(3), 224-32. [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2013.773059] [PMID]

Wong, K. K. K. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1), 1-32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268449353_

Zsila, A., Orosz, G., Bothe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Király, O., & Griffiths, M., et al. (2017). An empirical study on the motivations underlying augmented reality games: The case of Pokémon go during and after Pokémon fever. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 56-66. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.024]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2019/03/24 | Accepted: 2020/07/9 | Published: 2020/10/1

Received: 2019/03/24 | Accepted: 2020/07/9 | Published: 2020/10/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |