Volume 6, Issue 4 (Autumn 2018)

PCP 2018, 6(4): 207-214 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Besharat R, Soltani Azemat E, Mohammadian A. A Comparative Study of Rumination, Healthy Locus of Control, and Emotion Regulation in Children of Divorce and Normal Children. PCP 2018; 6 (4) :207-214

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-612-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-612-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Educational Sciences, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,abolfazl796@gmail.com

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 631 kb]

(4079 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8455 Views)

Full-Text: (3633 Views)

1. Introduction

Divorce is a powerful stressor that heavily influences children (Sutherland, Altenhofen, & Biringen, 2012). Divorce requires readjustment for all family members. Children are more prone to experience stress during divorce of their parents, and may subsequently show emotional, academic, and behavioral problems; these problems are more common among adolescents and girls (Sigal, Wolchik, Tein, & Sandler, 2012). Children of divorce are vulnerable to different psychological conditions, including isolation, anxiety, depression, social problems, violence, and difficulties with attention and thinking. They show lower levels of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and social support, and tend to use maladaptive problem-solving strategies (Kurtz, 1994).

Longitudinal studies have reported anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems in children of divorce compared to controls (Potter, 2010). Many studies have found lower levels of self-esteem (Bynum & Durm, 1996), and higher conduct disorder, mood disorders and substance abuse during adolescence (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1994). Some studies have also pointed out the stronger impact of divorce on girls compared to boys (Crawford, Cohen, Midlarsky, & Brook, 2001). Størksen, Røysamb, Holmen and Tambs (2006) also reported the stronger impact of divorce, as mood and anxiety disorders, on girls compared to boys.

Rumination is a symptom related to emotional problems like anxiety. It has been shown that rumination scores on the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) are directly related to the level of anxiety and mixed anxiety and depression symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Rumination has been defined as a response to life events that involves passive and repetitive focusing on an event and trying to seek its causes and outcomes (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008).

Processing past experiences and events in the form of rumination, when performing social activities, can lead to negative expectations about performance, thereby leading to the perpetuation and exacerbation of the disorder (Wong & Moulds, 2010). Rumination is known as the main core of depression (Roley et al., 2015) and social anxiety disorder (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008). Many studies indicate a close relationship between rumination and different kinds of emotional disorders (Kong, He, Auerbach, McWhinnie, & Xiao, 2015).

Problems with emotion regulation are also observed in children of divorce (Veinberg, 2015). literature review reveals that emotion regulation is an important factor in mental health and successful performance during social interactions, and defective emotion regulation is related to internalizing and externalizing disorders (Abasi, Pourshahbaz, Mohammadkhani, & Dolatshahi, 2017). Emotional responses provide important information about one’s experience in relation with others. Using this information, people learn how to behave when experiencing certain emotions, how to express emotional experiences verbally, what strategies to use to regulate emotions, and how to treat other people when having certain emotions (Bosse, Pontier, & Treur, 2010).

Research indicates that the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies is associated with problems in interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (Mohammadkhani, Abasi, Pourshahbaz, Mohammadi, & Fatehi, 2016). According to John and Gross’ theory on emotion regulation, reappraisal is an adaptive strategy that is negatively related to psychiatric disorders. Reappraisal is a form of cognitive change that involves interpretation of a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional effects. Suppression is a kind of response modulation involving inhibition of the current behavioral expression of emotion (Gross & John, 2003).

Another psychological factor regarded as a causative and perpetuating factor in psychological problems is “health locus of control” or “health control beliefs”, i.e. people consider an external locus of control for behaviors and events, and shift the responsibility to chance, fate, accidents, and environmental factors; or on the contrary, see themselves as an important factor in their behaviors and the outcome of their behavior, so that their beliefs could result in negative or positive outcomes (Culpin, Stapinski, Miles, Araya, & Joinson, 2015).

Locus of control as a mediating factor, forms part of the path between personal condition, social status, and health (Poortinga, Dunstan, & Fone, 2008). Believing in an internal locus of control is related to psychological well-being (Richardson, Field, Newton, & Bendell, 2012). This variable has been found to be a powerful predictor of depression (Lobel et al., 2008). All previous studies on this topic have indicated negative effects of divorce on the mental health of children of divorce (Reiter, Hjörleifsson, Breidablik, & Meland, 2013). So far, few studies have conducted on the children of divorce in Iran. Given the important role of aforementioned factors in psychological well-being, the present study aimed to examine rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation in children of divorce and compare them with normal children (girls).

2. Methods

The present study has a cross-sectional design. The statistical population included all students in the first grade of high school, in Tabriz City, Iran in the first semester of 2016-2017 academic year. With the help of school consultants, 45 female children of divorce and 45 female students were selected as the control group using a convenience sampling method. They were included in the study after giving their informed consents. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information. The study data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, including the Multiple Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). The following instruments were used to gather data:

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) was developed by Gross and John (2003). It has 10 items and 2 subscales; reappraisal (6 items) and suppression (4 items). The items are scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The Cronbach alpha values of 0.79 and 0.73 have been reported for reappraisal and suppression, respectively. Also a three-month test-retest reliability of 0.69 has been obtained for the total scale (Gross & John, 2003). In addition, among the state employees and the catholic students of the University of Milan, the Cronbach alpha values of this questionnaire ranged from 0.48 to 0.69 and from 0.42 to 0.63 for reappraisal and suppression, respectively. The Persian version of the ERQ has been validated in an Iranian population by Ghasempoor, Ilbeigi and Hassanzadeh (2012). In the present study, the internal consistency of the ERQ was found to be good (Cronbach alpha values ranged from 0.60 to 0.81).

The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scale was developed by Wallston, Strudler Wallston and DeVellis. (1978) to assess health locus of control. It has three forms: A, B, and C; forms A and B were developed in 1978, and form C in 1994 that could be used with certain conditions. The MHLC is completed in 10-14 minutes. Using the Kuder-Richardson formula 20 (KR-20), the internal consistency of the three subscales of MHLC, namely internal locus of control, chance locus of control, and powerful others locus of control, have been reported to be 0.50, 0.61, and 0.77, respectively. Moshki (2006) examined the reliability of the scale with 496 students and evaluated the validity of Form B using three methods: testretest, Cronbach alpha, and equivalent forms. Good content, concurrent, and construct validities of the form B of the MHLC have been also reported.

The Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) was developed by Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) to assess rumination. It has 22 items that are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to (4) (almost always). In Iran, Mahmoud Alilou, Bakhshipour Roodsari, Mansouri, Farnam and Fakhari (2012) reported good validity for the RRS. Experts confirmed the evidence of good content validity for the scale. The Cronbach alpha values ranging from 0.88 to 0.92 indicate high internal consistency of the scale. Also a high Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC=0.75) was found (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2004).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the Mean±SD age for each group. The results of the Independent samples t test indicate no significant difference between the two groups, in other words, the two groups were matched for this variable. In order to compare rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation across the two groups, the multivariate analysis of variance was used. First, the MANOVA assumptions were examined; the results of the Levene’s test for homogeneity of and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality of distributions respectively indicated the internal consistency and normality of distribution for the variables.

The results of the Box’s M test (F21, 28482.419=0.904; P>0.05) showed the equality of covariance matrices for independent variables in the groups. Therefore, MANOVA test can be used. Table 2 presents the results of the Wilks’ lambda test. The multivariate Wilks’ lambda test is significant, indicating a significant difference between children of divorce and normal children with regard to rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation. In order to determine the differences, MANOVA was performed.

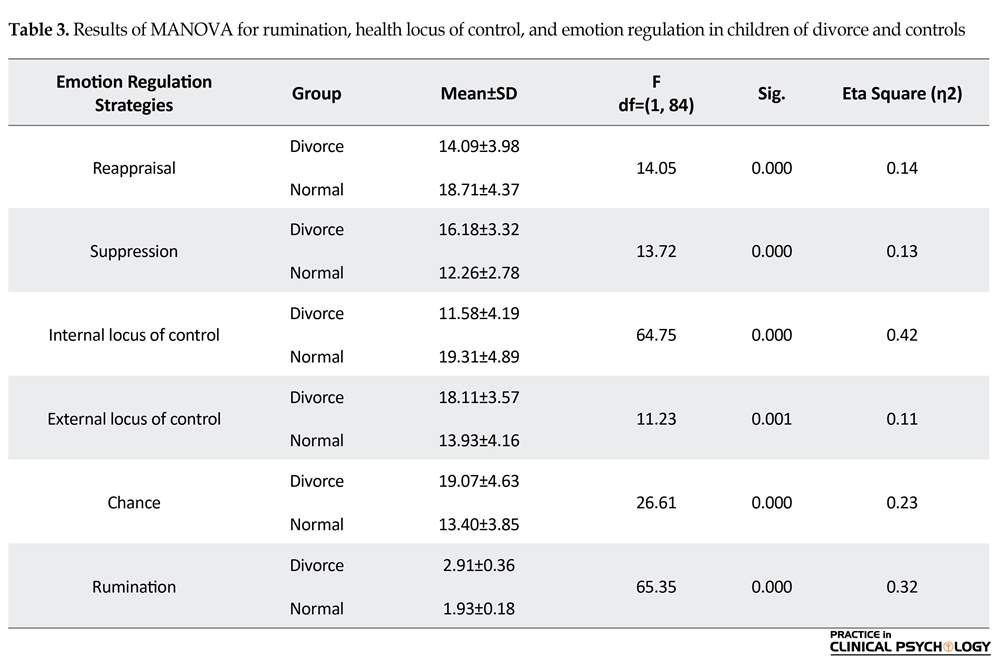

Table 3 presents the results of MANOVA, means, and standard deviations for rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation for the two groups. The findings presented in Table 3 indicate a significant difference between the two groups in reappraisal. In other words, children of divorce had significantly lower scores on this variable than normal children. In addition, there was a significant difference between the two groups in health control beliefs. Compared to controls, children of divorce had a significantly lower mean score on internal locus of control, but a significantly higher mean score on external and chance locus of control. Furthermore, in relation to rumination, children of divorce had significantly higher mean score on this variable than controls.

4. Discussion

The study results indicate that children of divorce, compared to normal children, have significantly higher rumination, suppression emotion regulation, and chance and powerful others locus of control, but significantly lower reappraisal emotion regulation and internal locus of control. These results are in line with the findings of some researchers (Hashemi, Yazdi, & Karkeshi, 2016; Kalter, Alpern, Spence, & Plunkett, 1984; Khayyer & Alborzi, 2002; Lee & Bax, 2000; Weyer & Sandler, 1998).

Divorce of parents is one of the most important challenges that children may experience. Divorce is rapidly increasing in today societies and has negative effects on the economic, social, and psychological domains, especially the mental health of parents and children. During the past 40 years, divorce of parents has been blamed for number of enduring and serious emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Divorced families have been portrayed as seriously impaired families by mental health professionals (Kelly & Emery, 2003).

Reappraisal is one of the most important emotion regulation strategies, but depressed patients rarely use this strategy that leads to negative thoughts and emotions (Abasi, Fata, Sadeghi, Banihashemi, & Mohammadee, 2013; Joormann & Gotlib, 2010). Reappraisal is accompanied by reduced rumination, and may also contribute to aware

Divorce is a powerful stressor that heavily influences children (Sutherland, Altenhofen, & Biringen, 2012). Divorce requires readjustment for all family members. Children are more prone to experience stress during divorce of their parents, and may subsequently show emotional, academic, and behavioral problems; these problems are more common among adolescents and girls (Sigal, Wolchik, Tein, & Sandler, 2012). Children of divorce are vulnerable to different psychological conditions, including isolation, anxiety, depression, social problems, violence, and difficulties with attention and thinking. They show lower levels of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and social support, and tend to use maladaptive problem-solving strategies (Kurtz, 1994).

Longitudinal studies have reported anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems in children of divorce compared to controls (Potter, 2010). Many studies have found lower levels of self-esteem (Bynum & Durm, 1996), and higher conduct disorder, mood disorders and substance abuse during adolescence (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1994). Some studies have also pointed out the stronger impact of divorce on girls compared to boys (Crawford, Cohen, Midlarsky, & Brook, 2001). Størksen, Røysamb, Holmen and Tambs (2006) also reported the stronger impact of divorce, as mood and anxiety disorders, on girls compared to boys.

Rumination is a symptom related to emotional problems like anxiety. It has been shown that rumination scores on the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) are directly related to the level of anxiety and mixed anxiety and depression symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Rumination has been defined as a response to life events that involves passive and repetitive focusing on an event and trying to seek its causes and outcomes (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008).

Processing past experiences and events in the form of rumination, when performing social activities, can lead to negative expectations about performance, thereby leading to the perpetuation and exacerbation of the disorder (Wong & Moulds, 2010). Rumination is known as the main core of depression (Roley et al., 2015) and social anxiety disorder (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008). Many studies indicate a close relationship between rumination and different kinds of emotional disorders (Kong, He, Auerbach, McWhinnie, & Xiao, 2015).

Problems with emotion regulation are also observed in children of divorce (Veinberg, 2015). literature review reveals that emotion regulation is an important factor in mental health and successful performance during social interactions, and defective emotion regulation is related to internalizing and externalizing disorders (Abasi, Pourshahbaz, Mohammadkhani, & Dolatshahi, 2017). Emotional responses provide important information about one’s experience in relation with others. Using this information, people learn how to behave when experiencing certain emotions, how to express emotional experiences verbally, what strategies to use to regulate emotions, and how to treat other people when having certain emotions (Bosse, Pontier, & Treur, 2010).

Research indicates that the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies is associated with problems in interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (Mohammadkhani, Abasi, Pourshahbaz, Mohammadi, & Fatehi, 2016). According to John and Gross’ theory on emotion regulation, reappraisal is an adaptive strategy that is negatively related to psychiatric disorders. Reappraisal is a form of cognitive change that involves interpretation of a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional effects. Suppression is a kind of response modulation involving inhibition of the current behavioral expression of emotion (Gross & John, 2003).

Another psychological factor regarded as a causative and perpetuating factor in psychological problems is “health locus of control” or “health control beliefs”, i.e. people consider an external locus of control for behaviors and events, and shift the responsibility to chance, fate, accidents, and environmental factors; or on the contrary, see themselves as an important factor in their behaviors and the outcome of their behavior, so that their beliefs could result in negative or positive outcomes (Culpin, Stapinski, Miles, Araya, & Joinson, 2015).

Locus of control as a mediating factor, forms part of the path between personal condition, social status, and health (Poortinga, Dunstan, & Fone, 2008). Believing in an internal locus of control is related to psychological well-being (Richardson, Field, Newton, & Bendell, 2012). This variable has been found to be a powerful predictor of depression (Lobel et al., 2008). All previous studies on this topic have indicated negative effects of divorce on the mental health of children of divorce (Reiter, Hjörleifsson, Breidablik, & Meland, 2013). So far, few studies have conducted on the children of divorce in Iran. Given the important role of aforementioned factors in psychological well-being, the present study aimed to examine rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation in children of divorce and compare them with normal children (girls).

2. Methods

The present study has a cross-sectional design. The statistical population included all students in the first grade of high school, in Tabriz City, Iran in the first semester of 2016-2017 academic year. With the help of school consultants, 45 female children of divorce and 45 female students were selected as the control group using a convenience sampling method. They were included in the study after giving their informed consents. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information. The study data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, including the Multiple Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). The following instruments were used to gather data:

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) was developed by Gross and John (2003). It has 10 items and 2 subscales; reappraisal (6 items) and suppression (4 items). The items are scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The Cronbach alpha values of 0.79 and 0.73 have been reported for reappraisal and suppression, respectively. Also a three-month test-retest reliability of 0.69 has been obtained for the total scale (Gross & John, 2003). In addition, among the state employees and the catholic students of the University of Milan, the Cronbach alpha values of this questionnaire ranged from 0.48 to 0.69 and from 0.42 to 0.63 for reappraisal and suppression, respectively. The Persian version of the ERQ has been validated in an Iranian population by Ghasempoor, Ilbeigi and Hassanzadeh (2012). In the present study, the internal consistency of the ERQ was found to be good (Cronbach alpha values ranged from 0.60 to 0.81).

The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scale was developed by Wallston, Strudler Wallston and DeVellis. (1978) to assess health locus of control. It has three forms: A, B, and C; forms A and B were developed in 1978, and form C in 1994 that could be used with certain conditions. The MHLC is completed in 10-14 minutes. Using the Kuder-Richardson formula 20 (KR-20), the internal consistency of the three subscales of MHLC, namely internal locus of control, chance locus of control, and powerful others locus of control, have been reported to be 0.50, 0.61, and 0.77, respectively. Moshki (2006) examined the reliability of the scale with 496 students and evaluated the validity of Form B using three methods: testretest, Cronbach alpha, and equivalent forms. Good content, concurrent, and construct validities of the form B of the MHLC have been also reported.

The Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) was developed by Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) to assess rumination. It has 22 items that are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to (4) (almost always). In Iran, Mahmoud Alilou, Bakhshipour Roodsari, Mansouri, Farnam and Fakhari (2012) reported good validity for the RRS. Experts confirmed the evidence of good content validity for the scale. The Cronbach alpha values ranging from 0.88 to 0.92 indicate high internal consistency of the scale. Also a high Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC=0.75) was found (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2004).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the Mean±SD age for each group. The results of the Independent samples t test indicate no significant difference between the two groups, in other words, the two groups were matched for this variable. In order to compare rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation across the two groups, the multivariate analysis of variance was used. First, the MANOVA assumptions were examined; the results of the Levene’s test for homogeneity of and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality of distributions respectively indicated the internal consistency and normality of distribution for the variables.

The results of the Box’s M test (F21, 28482.419=0.904; P>0.05) showed the equality of covariance matrices for independent variables in the groups. Therefore, MANOVA test can be used. Table 2 presents the results of the Wilks’ lambda test. The multivariate Wilks’ lambda test is significant, indicating a significant difference between children of divorce and normal children with regard to rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation. In order to determine the differences, MANOVA was performed.

Table 3 presents the results of MANOVA, means, and standard deviations for rumination, health locus of control, and emotion regulation for the two groups. The findings presented in Table 3 indicate a significant difference between the two groups in reappraisal. In other words, children of divorce had significantly lower scores on this variable than normal children. In addition, there was a significant difference between the two groups in health control beliefs. Compared to controls, children of divorce had a significantly lower mean score on internal locus of control, but a significantly higher mean score on external and chance locus of control. Furthermore, in relation to rumination, children of divorce had significantly higher mean score on this variable than controls.

4. Discussion

The study results indicate that children of divorce, compared to normal children, have significantly higher rumination, suppression emotion regulation, and chance and powerful others locus of control, but significantly lower reappraisal emotion regulation and internal locus of control. These results are in line with the findings of some researchers (Hashemi, Yazdi, & Karkeshi, 2016; Kalter, Alpern, Spence, & Plunkett, 1984; Khayyer & Alborzi, 2002; Lee & Bax, 2000; Weyer & Sandler, 1998).

Divorce of parents is one of the most important challenges that children may experience. Divorce is rapidly increasing in today societies and has negative effects on the economic, social, and psychological domains, especially the mental health of parents and children. During the past 40 years, divorce of parents has been blamed for number of enduring and serious emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Divorced families have been portrayed as seriously impaired families by mental health professionals (Kelly & Emery, 2003).

Reappraisal is one of the most important emotion regulation strategies, but depressed patients rarely use this strategy that leads to negative thoughts and emotions (Abasi, Fata, Sadeghi, Banihashemi, & Mohammadee, 2013; Joormann & Gotlib, 2010). Reappraisal is accompanied by reduced rumination, and may also contribute to aware

ness of useful and appropriate solutions; this strategy could help the disturbed mind to reorganize problematic conditions (Smoski, LaBar, & Steffens, 2014).

Suppression is a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that is accompanied by psychological and physiological symptoms. This strategy is the opposite of accepting emotions, and people with emotional problems tend to suppress their emotions. Suppression is a strategy commonly used by depressed individuals (Feldman et al., 2009). Depressed patients not only suppress their negative emotions, but also suppress positive emotions, and get less pleasure from usual life experiences, compared to non-depressed individuals (Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008).

We can use the learned helplessness model to explain heath locus of control. This model refers to individuals’ expectations and beliefs regarding the outcomes of their behaviors and actions. Those with learned helplessness do not believe that they can influence the outcomes, and regard external factors as influencing ones. Because of experiencing stress and depression and such emotions as shame and guilt, children of divorce are vulnerable to psychological distress that may cause them adopt an external locus of control orientation–that may lead to depression (Richardson et al., 2012).

Health locus of control is one of the important factors in successful recovery and mental and physical health and internal locus of control has always been known as a predictor of recovery from a broad range of disorders. However, external locus of control is known as a negative factor in recovery form many disorders (Thakral, Bhatia, Gettig, Nimgaonkar, & Deshpande, 2014). Internal locus of control is in fact a protective factor against many psychiatric disorders, including depression, and is positively associated with coping strategies, adaptive emotion regulation strategies, and stress tolerance that are all protective factors against depression (Karstoft, Armour, Elklit, & Solomon, 2015).

Rumination is a cognitive component of depression that makes people excessively contemplate on the causes and outcomes of their problems (Wells, 2010). Rumination is one of the underlying factors in depression (Roelofs, Huibers, Peeters, & Arntz, 2008). It is an exacerbating factor in anxiety and depression that is accompanied by lower adjustment and higher stress. Whilst, rumination initially seems to be a way of focusing on goal attainment, it in fact leads to aggravation of problems and negative emotions (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins, 2008). Through its negative effects on information processing, rumination shifts the focus of the person from here and now to the past events, which in turn leads to exacerbation of mood and anxiety disorders.

In social anxiety, due to negative evaluation of the self and focusing on personal frustrations and failures in the past, the person tends to have excessively negative evaluations of their performance in the future, and develop a high tendency to expect failure (Wong & Moulds, 2010). It seems that rumination in children of divorce is a cause of depression that makes them excessively think about the reason of their parents’ divorce.

According to the study results, we suggested that future studies be focus on locus of control, rumination, and emotion regulation as impaired psychological domains in children of divorce, and that intervention and training programs based on these variables should be provided for this population. Among the limitations of the present study were only females in the study sample and using self-report instruments that are inherently subject to bias. Future studies are suggested to overcome these limitations. Children of divorce are vulnerable to pathological processes as rumination, suppression, reappraisal, and chance and external locus of control, thus paying attention to mental health of the children of divorce is crucially important.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, ethical issues such as confidentiality of participants' information, written consent of participants and non-intervention were observed.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Suppression is a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that is accompanied by psychological and physiological symptoms. This strategy is the opposite of accepting emotions, and people with emotional problems tend to suppress their emotions. Suppression is a strategy commonly used by depressed individuals (Feldman et al., 2009). Depressed patients not only suppress their negative emotions, but also suppress positive emotions, and get less pleasure from usual life experiences, compared to non-depressed individuals (Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008).

We can use the learned helplessness model to explain heath locus of control. This model refers to individuals’ expectations and beliefs regarding the outcomes of their behaviors and actions. Those with learned helplessness do not believe that they can influence the outcomes, and regard external factors as influencing ones. Because of experiencing stress and depression and such emotions as shame and guilt, children of divorce are vulnerable to psychological distress that may cause them adopt an external locus of control orientation–that may lead to depression (Richardson et al., 2012).

Health locus of control is one of the important factors in successful recovery and mental and physical health and internal locus of control has always been known as a predictor of recovery from a broad range of disorders. However, external locus of control is known as a negative factor in recovery form many disorders (Thakral, Bhatia, Gettig, Nimgaonkar, & Deshpande, 2014). Internal locus of control is in fact a protective factor against many psychiatric disorders, including depression, and is positively associated with coping strategies, adaptive emotion regulation strategies, and stress tolerance that are all protective factors against depression (Karstoft, Armour, Elklit, & Solomon, 2015).

Rumination is a cognitive component of depression that makes people excessively contemplate on the causes and outcomes of their problems (Wells, 2010). Rumination is one of the underlying factors in depression (Roelofs, Huibers, Peeters, & Arntz, 2008). It is an exacerbating factor in anxiety and depression that is accompanied by lower adjustment and higher stress. Whilst, rumination initially seems to be a way of focusing on goal attainment, it in fact leads to aggravation of problems and negative emotions (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins, 2008). Through its negative effects on information processing, rumination shifts the focus of the person from here and now to the past events, which in turn leads to exacerbation of mood and anxiety disorders.

In social anxiety, due to negative evaluation of the self and focusing on personal frustrations and failures in the past, the person tends to have excessively negative evaluations of their performance in the future, and develop a high tendency to expect failure (Wong & Moulds, 2010). It seems that rumination in children of divorce is a cause of depression that makes them excessively think about the reason of their parents’ divorce.

According to the study results, we suggested that future studies be focus on locus of control, rumination, and emotion regulation as impaired psychological domains in children of divorce, and that intervention and training programs based on these variables should be provided for this population. Among the limitations of the present study were only females in the study sample and using self-report instruments that are inherently subject to bias. Future studies are suggested to overcome these limitations. Children of divorce are vulnerable to pathological processes as rumination, suppression, reappraisal, and chance and external locus of control, thus paying attention to mental health of the children of divorce is crucially important.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, ethical issues such as confidentiality of participants' information, written consent of participants and non-intervention were observed.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abasi, I., Fata, L., Sadeghi, M., Banihashemi, S., & Mohammadee, A. (2013). A comparison of transdiagnostic components in generalized anxiety disorder, unipolar mood disorder and nonclinical population. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Medical, Health, Biomedical, Bioengineering and Pharmaceutical Engineering, 7(12), 803-11.

- Abasi, I., Pourshahbaz, A., Mohammadkhani, P., & Dolatshahi, B. (2017). Mediation role of emotion regulation strategies on the relationship between emotional intensity, safety and reward motivations with social anxiety symptoms, rumination and worry: A structural equation modeling. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 11(3), e9640. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.9640]

- Bosse, T., Pontier, M., & Treur, J. (2010). A computational model based on Gross’ emotion regulation theory. Cognitive Systems Research, 11(3), 211-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.cogsys.2009.10.001]

- Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 891-903. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002] [PMID]

- Bynum, M. K., & Durm, M. W. (1996). Children of divorce and its effect on their self-esteem. Psychological Reports, 79(2), 447-50. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.2.447] [PMID]

- Crawford, T. N., Cohen, P., Midlarsky, E., & Brook, J. S. (2001). Internalizing symptoms in adolescents: Gender differences in vulnerability to parental distress and discord. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 95-118. [DOI:10.1111/1532-7795.00005]

- Culpin, I., Stapinski, L., Miles, Ö. B., Araya, R., & Joinson, C. (2015). Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: The mediating role of locus of control. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 269-278. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.030] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Feldman, R., Granat, A., Pariente, C., Kanety, H., Kuint, J., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2009). Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 919-27. [DOI:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651] [PMID]

- Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (1994). Parental separation, adolescent psychopathology, and problem behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(8), 1122-33. [DOI:10.1097/00004583-199410000-00008] [PMID]

- Ghasempour, A., Ilbeigi, R., & Hasanzadeh, S. (2012). [Psychometric properties of the Gross and John’s Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in an Iranian sample (Persian)]. Paper Presented at The 6th Conference on Students’ Mental Health, Gilan, Iran, 16-17 May 2012.

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-62. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348] [PMID]

- Hashemi, F., Yazdi, A., & Karkeshi, H. (2016). [The role of theory of mind and empathy in prediction of behavioral-emotional problems in students from typical and single parent (The case of divorce) families. Research in Clinical Psychology and Counseling, 6(1), 24-43. [DOI:10.22067/ijap.v6i1.35494]

- Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition and Emotion, 24(2), 281-98. [DOI:10.1080/02699930903407948] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kalter, N., Alpern, D., Spence, R., & Plunkett, J. W. (1984). Locus of control in children of divorce. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(4), 410-4. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4804_14] [PMID]

- Karstoft, K. I., Armour, C., Elklit, A., & Solomon, Z. (2015). The role of locus of control and coping style in predicting longitudinal PTSD-trajectories after combat exposure. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 32, 89-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.007] [PMID]

- Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations, 52(4), 352-62. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x]

- Khayyer, M., & Alborzi, S. (2002). Locus of control of children experiencing separation and divorce in their families in Iran. Psychological Reports, 90(1), 239-42. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.239] [PMID]

- Kong, T., He, Y., Auerbach, R. P., McWhinnie, C. M., & Xiao, J. (2015). Rumination and depression in Chinese university students: The mediating role of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 221-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.035] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kurtz, L. (1994). Psychosocial coping resources in elementary school-age children of divorce. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64(4), 554-63. [DOI:10.1037/h0079561] [PMID]

- Lee, C. M., & Bax, K. A. (2000). Children’s reactions to parental separation and divorce. Paediatrics & Child Health, 5(4), 217-8. [DOI:10.1093/pch/5.4.217]

- Lobel, M., Cannella, D. L., Graham, J. E., DeVincent, C., Schneider, J., & Meyer, B. A. (2008). Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology, 27(5), 604-15. [DOI:10.1037/a0013242] [PMID]

- Mahmoud Alilou, M., Bakhshipour Roodsari. A., Mansouri, A., Farnam, A., & Fakhari, A. (2012). [The comparison of worry, obsession and rumination in individual with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression disorder and normal individual (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(4), 55-74. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2011.1535]

- Mohammadkhani, P., Abasi, I., Pourshahbaz, A., Mohammadi, A., & Fatehi, M. (2016). The role of neuroticism and experiential avoidance in predicting anxiety and depression symptoms: Mediating effect of emotion regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(3), e5047. [DOI:10.17795/ijpbs-5047] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moshki, M. (2006). [Examination of the application of the PRECEDE–PROCEED model in combination with the locus of control theory in improving the mental health of students (Persian)] [PhD Dissertation]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modarres University.

- Nezlek, J. B., & Kuppens, P. (2008). Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. Journal of Personality, 76(4), 561-80. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x] [PMID]

- Nolen Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569-82. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569] [PMID]

- Nolen Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504-11. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504] [PMID]

- Nolen Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400-24. [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x] [PMID]

- Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2004). Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Poortinga, W., Dunstan, F. D., & Fone, D. L. (2008). Health locus of control beliefs and socio-economic differences in self-rated health. Preventive Medicine, 46(4), 374-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.015] [PMID]

- Potter, D. (2010). Psychosocial well‐being and the relationship between divorce and children’s academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(4), 933-46. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00740.x]

- Reiter, S. F., Hjörleifsson, S., Breidablik, H. J., & Meland, E. (2013). Impact of divorce and loss of parental contact on health complaints among adolescents. Journal of Public Health, 35(2), 278-85. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fds101] [PMID]

- Richardson, A., Field, T., Newton, R., & Bendell, D. (2012). Locus of control and prenatal depression. Infant Behavior and Development, 35(4), 662-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Roelofs, J., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., & Arntz, A. (2008). Effects of neuroticism on depression and anxiety: Rumination as a possible mediator. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 576-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.019]

- Roley, M. E., Claycomb, M. A., Contractor, A. A., Dranger, P., Armour, C., & Elhai, J. D. (2015). The relationship between rumination, PTSD, and depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 116-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.006] [PMID]

- Sigal, A. B., Wolchik, S. A., Tein, J. Y., & Sandler, I. N. (2012). Enhancing youth outcomes following parental divorce: A longitudinal study of the effects of the New Beginnings Program on educational and occupational goals. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 150-65. [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2012.651992] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Smoski, M. J., LaBar, K. S., & Steffens, D. C. (2014). Relative effectiveness of reappraisal and distraction in regulating emotion in late-life depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(9), 898-907. [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.070] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Størksen, I., Røysamb, E., Holmen, T. L., & Tambs, K. (2006). Adolescent adjustment and well‐being: Effects of parental divorce and distress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(1), 75-84. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00494.x] [PMID]

- Sutherland, K. E., Altenhofen, S., & Biringen, Z. (2012). Emotional availability during mother–child interactions in divorcing and intact married families. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(2), 126-41. [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2011.651974]

- Thakral, S., Bhatia, T., Gettig, E. A., Nimgaonkar, V., & Deshpande, S. N. (2014). A comparative study of health locus of control in patients with schizophrenia and their first degree relatives. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 34-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Veinberg, I. (2015). Emotional awareness: The key to dealing appropriately with children of divorced families in schools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 514-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.281]

- Wallston, K. A., Strudler Wallston, B., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Education Monographs, 6(1), 160-70. [DOI:10.1177/109019817800600107] [PMID]

- Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163-206. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wells, A. (2010). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Press.

- Weyer, M., & Sandler, I. N. (1998). Stress and coping as predictors of children’s divorce-related ruminations. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(1), 78-86. [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_9] [PMID]

- Wong, Q. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2010). Do socially anxious individuals hold positive metacognitive beliefs about rumination? Behaviour Change, 27(2), 69-83. [DOI:10.1375/bech.27.2.69]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Psychiatry

Received: 2018/01/20 | Accepted: 2018/05/27 | Published: 2018/10/1

Received: 2018/01/20 | Accepted: 2018/05/27 | Published: 2018/10/1

References

1. Abasi, I., Fata, L., Sadeghi, M., Banihashemi, S., & Mohammadee, A. (2013). A comparison of transdiagnostic components in generalized anxiety disorder, unipolar mood disorder and nonclinical population. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Medical, Health, Biomedical, Bioengineering and Pharmaceutical Engineering, 7(12), 803-11.

2. Abasi, I., Pourshahbaz, A., Mohammadkhani, P., & Dolatshahi, B. (2017). Mediation role of emotion regulation strategies on the relationship between emotional intensity, safety and reward motivations with social anxiety symptoms, rumination and worry: A structural equation modeling. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 11(3), e9640. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.9640] [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.9640]

3. Bosse, T., Pontier, M., & Treur, J. (2010). A computational model based on Gross' emotion regulation theory. Cognitive Systems Research, 11(3), 211-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.cogsys.2009.10.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.cogsys.2009.10.001]

4. Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 891-903. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002]

5. Bynum, M. K., & Durm, M. W. (1996). Children of divorce and its effect on their self-esteem. Psychological Reports, 79(2), 447-50. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.2.447] [PMID] [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.2.447]

6. Crawford, T. N., Cohen, P., Midlarsky, E., & Brook, J. S. (2001). Internalizing symptoms in adolescents: Gender differences in vulnerability to parental distress and discord. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 95-118. [DOI:10.1111/1532-7795.00005] [DOI:10.1111/1532-7795.00005]

7. Culpin, I., Stapinski, L., Miles, Ö. B., Araya, R., & Joinson, C. (2015). Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: The mediating role of locus of control. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 269-278. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.030] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.030]

8. Feldman, R., Granat, A., Pariente, C., Kanety, H., Kuint, J., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2009). Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 919-27. [DOI:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651]

9. Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (1994). Parental separation, adolescent psychopathology, and problem behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(8), 1122-33. [DOI:10.1097/00004583-199410000-00008] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/00004583-199410000-00008]

10. Ghasempour, A., Ilbeigi, R., & Hasanzadeh, S. (2012). [Psychometric properties of the Gross and John's Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in an Iranian sample (Persian)]. Paper Presented at The 6th Conference on Students' Mental Health, Gilan, Iran, 16-17 May 2012.

11. Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-62. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348]

12. Hashemi, F., Yazdi, A., & Karkeshi, H. (2016). [The role of theory of mind and empathy in prediction of behavioral-emotional problems in students from typical and single parent (The case of divorce) families. Research in Clinical Psychology and Counseling, 6(1), 24-43. [DOI:10.22067/ijap.v6i1.35494]

13. Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition and Emotion, 24(2), 281-98. [DOI:10.1080/02699930903407948] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1080/02699930903407948]

14. Kalter, N., Alpern, D., Spence, R., & Plunkett, J. W. (1984). Locus of control in children of divorce. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(4), 410-4. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4804_14] [PMID] [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4804_14]

15. Karstoft, K. I., Armour, C., Elklit, A., & Solomon, Z. (2015). The role of locus of control and coping style in predicting longitudinal PTSD-trajectories after combat exposure. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 32, 89-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.007] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.007]

16. Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children's adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations, 52(4), 352-62. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x]

17. Khayyer, M., & Alborzi, S. (2002). Locus of control of children experiencing separation and divorce in their families in Iran. Psychological Reports, 90(1), 239-42. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.239] [PMID] [DOI:10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.239]

18. Kong, T., He, Y., Auerbach, R. P., McWhinnie, C. M., & Xiao, J. (2015). Rumination and depression in Chinese university students: The mediating role of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 221-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.035] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.035]

19. Kurtz, L. (1994). Psychosocial coping resources in elementary school-age children of divorce. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64(4), 554-63. [DOI:10.1037/h0079561] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/h0079561]

20. Lee, C. M., & Bax, K. A. (2000). Children's reactions to parental separation and divorce. Paediatrics & Child Health, 5(4), 217-8. [DOI:10.1093/pch/5.4.217] [DOI:10.1093/pch/5.4.217]

21. Lobel, M., Cannella, D. L., Graham, J. E., DeVincent, C., Schneider, J., & Meyer, B. A. (2008). Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology, 27(5), 604-15. [DOI:10.1037/a0013242] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/a0013242]

22. Mahmoud Alilou, M., Bakhshipour Roodsari. A., Mansouri, A., Farnam, A., & Fakhari, A. (2012). [The comparison of worry, obsession and rumination in individual with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression disorder and normal individual (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(4), 55-74. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2011.1535]

23. Mohammadkhani, P., Abasi, I., Pourshahbaz, A., Mohammadi, A., & Fatehi, M. (2016). The role of neuroticism and experiential avoidance in predicting anxiety and depression symptoms: Mediating effect of emotion regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(3), e5047. [DOI:10.17795/ijpbs-5047] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.17795/ijpbs-5047]

24. Moshki, M. (2006). [Examination of the application of the PRECEDE–PROCEED model in combination with the locus of control theory in improving the mental health of students (Persian)] [PhD Dissertation]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modarres University.

25. Nezlek, J. B., & Kuppens, P. (2008). Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. Journal of Personality, 76(4), 561-80. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x]

26. Nolen Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569-82. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569]

27. Nolen Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504-11. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504]

28. Nolen Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400-24. [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x]

29. Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2004). Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

30. Poortinga, W., Dunstan, F. D., & Fone, D. L. (2008). Health locus of control beliefs and socio-economic differences in self-rated health. Preventive Medicine, 46(4), 374-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.015] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.015]

31. Potter, D. (2010). Psychosocial well‐being and the relationship between divorce and children's academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(4), 933-46. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00740.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00740.x]

32. Reiter, S. F., Hjörleifsson, S., Breidablik, H. J., & Meland, E. (2013). Impact of divorce and loss of parental contact on health complaints among adolescents. Journal of Public Health, 35(2), 278-85. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fds101] [PMID] [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fds101]

33. Richardson, A., Field, T., Newton, R., & Bendell, D. (2012). Locus of control and prenatal depression. Infant Behavior and Development, 35(4), 662-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.006] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.006]

34. Roelofs, J., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., & Arntz, A. (2008). Effects of neuroticism on depression and anxiety: Rumination as a possible mediator. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 576-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.019] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.019]

35. Roley, M. E., Claycomb, M. A., Contractor, A. A., Dranger, P., Armour, C., & Elhai, J. D. (2015). The relationship between rumination, PTSD, and depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 116-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.006] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.006]

36. Sigal, A. B., Wolchik, S. A., Tein, J. Y., & Sandler, I. N. (2012). Enhancing youth outcomes following parental divorce: A longitudinal study of the effects of the New Beginnings Program on educational and occupational goals. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 150-65. [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2012.651992] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2012.651992]

37. Smoski, M. J., LaBar, K. S., & Steffens, D. C. (2014). Relative effectiveness of reappraisal and distraction in regulating emotion in late-life depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(9), 898-907. [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.070] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.070]

38. Størksen, I., Røysamb, E., Holmen, T. L., & Tambs, K. (2006). Adolescent adjustment and well‐being: Effects of parental divorce and distress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(1), 75-84. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00494.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00494.x]

39. Sutherland, K. E., Altenhofen, S., & Biringen, Z. (2012). Emotional availability during mother–child interactions in divorcing and intact married families. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(2), 126-41. [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2011.651974] [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2011.651974]

40. Thakral, S., Bhatia, T., Gettig, E. A., Nimgaonkar, V., & Deshpande, S. N. (2014). A comparative study of health locus of control in patients with schizophrenia and their first degree relatives. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 34-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.004] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.004]

41. Veinberg, I. (2015). Emotional awareness: The key to dealing appropriately with children of divorced families in schools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 514-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.281] [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.281]

42. Wallston, K. A., Strudler Wallston, B., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Education Monographs, 6(1), 160-70. [DOI:10.1177/109019817800600107] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/109019817800600107]

43. Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163-206. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163]

44. Wells, A. (2010). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Press.

45. Weyer, M., & Sandler, I. N. (1998). Stress and coping as predictors of children's divorce-related ruminations. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(1), 78-86. [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_9] [PMID] [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_9]

46. Wong, Q. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2010). Do socially anxious individuals hold positive metacognitive beliefs about rumination? Behaviour Change, 27(2), 69-83. [DOI:10.1375/bech.27.2.69] [DOI:10.1375/bech.27.2.69]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |