Volume 7, Issue 3 (Summer 2019)

PCP 2019, 7(3): 215-224 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saeidi S, Mohamadzadeh Ebrahimi A, Soleimanian A. The Direct and Indirect Effects of Gratitude and Optimism on the Marital Satisfaction. PCP 2019; 7 (3) :215-224

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-602-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-602-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord,Iran. ,Alimohamadzade98@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord,Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 763 kb]

(2234 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6104 Views)

2. Methods

The current cross-sectional study using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted on all female married teachers in Sabzevar city, Iran (N=2400). The cluster sampling method was used to select the sample. In order to determine the sample size, in structural equation modeling, 5 to 10 subjects were considered for each observed variable (Bentler & Chou, 1987; Kline, 2011). However, 250 questionnaires were distributed among the participants due to the possibility of loss and the existence of outliers. Finally, after deletion of incomplete questionnaires and removing the univariate and multivariate outliers by z-values and Mahalanobis distance, 241 questionnaires were included in the final analysis. The inclusion criteria were providing informed consent for participation in the research, passing at least two years of married life, having no addiction or drug abuse, lacking any serious illness or a chronic mental disorder or family acute crisis. The exclusion criteria comprised returning incomplete or distorted answers. Three questionnaires were used to collect the research data as follows:

ENRICH Marital Satisfaction (EMS) scale: the ENRICH (evaluation and nurturing relationship issues, communication, and happiness) developed by Olson, Fournier, and Druckman (Olson, Fournier, & Druckman, 1987) is used for evaluating potential areas of problem and recognizing areas of power and enrichment of marital relationships. Olson et al., (1987) confirmed the psychometric properties of this scale (α=0.92). A short version of this scale, whose psychometric properties were confirmed in the Iranian population (Soleimanian, 1994), was used in the current study (α=0.84). The scale consists of 47 items and nine sub-scales: personality issues, communication, resolution conflict, financial management, leisure activities, sexual relationship, children and parenting, family and friends, and religious orientation. Response range is on a Likert-type scale from 1 (entirely agree) to 5 (entirely disagree).

Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6): GQ-6 is a 6-item measure developed by McCullough et al., (2002) to evaluate experiences and expressions of gratefulness and appreciation in daily life, as well as feelings about receiving them from others. Responses were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two items were reversely coded. A higher score indicated a greater level of grateful disposition in individuals. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire are reported well, in many studies and in different cultural settings; Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the six-item totals range from .76 to .84. Scores on the GQ-6 correlate substantially with other measures hypothesized to assess the extent to which people experience gratitude in daily life (McCullough et al., 2002; Neto, 2007; Wei, Wu, Kong, & Wang, 2011). This six-item measure has good psychometric properties in Iranian population (Aghababai, Farahani, & Fazeli Mehr Abādi, 2010).

Life Orientation Test- revised (LOT-R): The LOT-R is a 10-item self-report measure that assesses optimism versus pessimism developed by Scheier, Carver, & Bridges. (1994). Three items measure optimism, three items measure pessimism, and there are four filler items. Response range is on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The overall score was computed by adding the raw scores of the optimism subscale with the inverted pessimism raw scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the entire 6 items of the scale was 0.78, suggesting that the scale had an accepTable level of internal consistency. The test-retest correlations were 0.68, 0.60, 0.56 and 0.79, suggesting that the scale was sTable across time (Scheier et al., 1994; Schou, Ekeberg, Ruland, Sandvik, & Kåresen et al., 2004; Segerstrom, Evans, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2011). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72, and test-retest correlations were 0.87 in the Persian version of this questionnaire (Kajbf, Oraizi, & Khodbakhshi, 2006).

After selecting the sample, questionnaires were distributed among married female teachers in the selected schools and high schools. In the beginning of the questionnaire, the study objectives, its importance, and the need for honesty in responses were explained to the participants. The informed consent was obtained from the subjects. The sample provided and signed a written consent form before administering the questionnaires. The hypothesized model was tested using AMOS 24, with maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was measured based on six indicators including the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Incremental Fit Index (IFI). Indirect effects were tested by bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals in Preacher and Hayes’ Macro program (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

3. Results

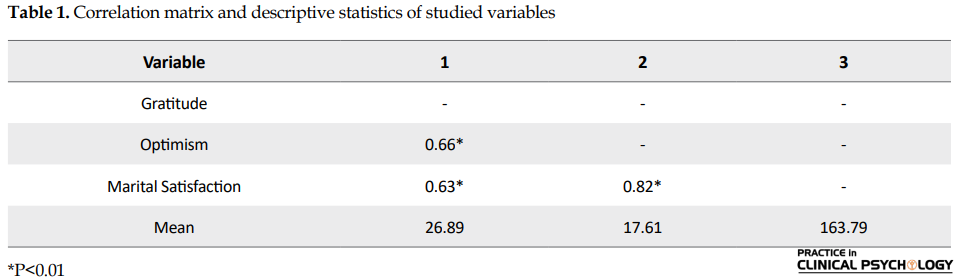

The participants aged 26-50 years (M=40.32, SD=5.18) with duration of marriage of 2-18 years (M=6.68, SD=0.85) and 0-5 children (M=2.16, SD=1.06). The correlation matrix means and standard deviations of variables are presented in Table 1.

According to Table 1, the Mean±SD scores of the gratitude, optimism, and marital satisfaction were 26.89±4.06, 17.61±3.88, and 163.79±20.38, respectively. The gratitude was positively correlated with optimism and marital satisfaction (p<0.01). Also, there was a significant positive relationship between optimism and marital satisfaction (p<0.01). The result of model fit, using SEM is shown in Table 2.

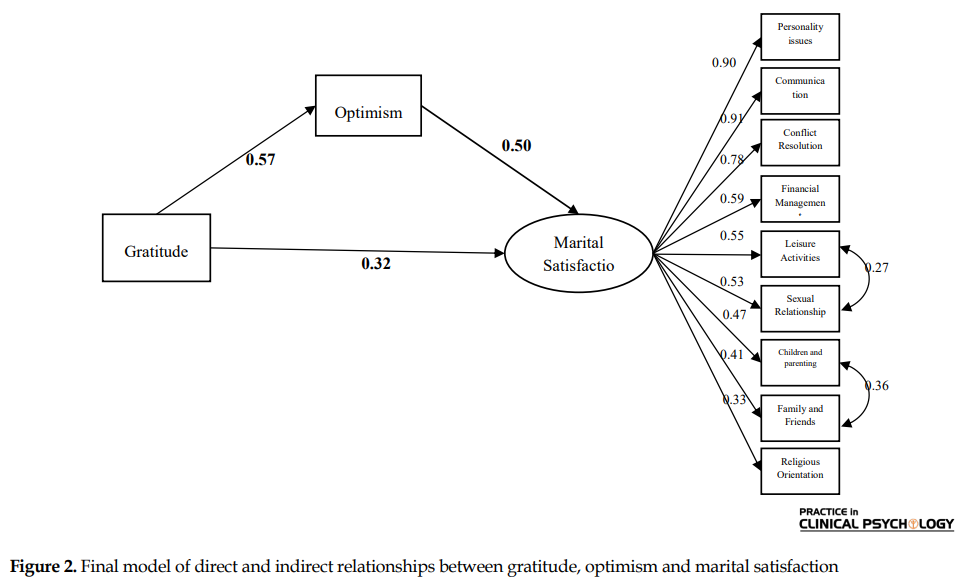

According to Table 2, some of the fit indices (AGFI, RMSEA) had good fit with the data in the hypothesized model, and indicated the needs to be modified. Therefore, in order to fit better among the modification indices proposed by AMOS-24, two of these modifications were made; the two paths errors of marital satisfaction (“Children and parenting” to “Family and Friends” and “Leisure and Activities” to “sexual and relationship”) were correlated. The result of the recent modifications was the second model or the final modified model. As shown in Table 2, fit indices indicated that the best fit to the data was obtained in the final model. Figure 2 shows the final model and path coefficients (β) between variables.

The final model represents a positive direct effect of the gratitude on marital satisfaction (β=0.32, p<0.05), optimism (β=0.57, p<0.05), and a positive direct effect of optimism on marital satisfaction (β=0.50, p<0.05) (Figure 2). The results of indirect effects using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals in Preacher and Hayes’ Macro program showed in Table 3.

Table 3 showed that the lower and upper confidence intervals were 0.85 and 1.74, respectively. Therefore, this confidence interval does not include zero, hence, there is a significant indirect effect. In other words, the results of Table 3 show a positive indirect effect of the gratitude on the marital satisfaction with mediating of the optimism.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed investigating the direct and indirect effects of gratitude and optimism on marital satisfaction using a structural equation modeling approach. The final model showed that the values of indices were desirable and the model had a good fit with the data. The results indicated that gratitude was positively associated with marital satisfaction. These results were consistent with several previous findings (Algoe et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2011; Schramm et al., 2005). Also, other studies demonstrated that gratitude is associated with improvement of relationship, intimacy, and sense of security in the relationship (Gordon, Impett, Kogan, Oveis, & Keltner, 2012). Another study found that gratitude is associated with a belief to find more chance to achieve the important goals of life in the marital relationship (Feeney, 2004). A possible explanation for these findings might be that gratitude assists couples to create positive resources; therefore, when couples encounter negative events in their relationships, they can concentrate on the positive manners already interacted and thus prevent the negative interactions that may occur in their relationship (Fredrickson, 2004).

Furthermore, the ability to draw previous positive experiences within the relationship when couples face negative events may enable them to see the good in the relationship and present higher levels of marital satisfaction. Gratitude can provide the relationship with a positive environment where couples are more conscious of and thankful for the good things that exist in the marriage. This consciousness allows couples to tend to the positive traits each possess, the positive manners in which they create the marriage work, the positive manners in which they care for one another, and the positive benefits they get. Therefore, higher levels of positivity between couples may associate with increases in marital satisfaction. Also, gratitude can increase marital satisfaction by increasing levels of happiness (Seligman et al., 2005), life satisfaction (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004), and positive effect (Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003).

The final model showed a positive indirect effect of the gratitude on the marital satisfaction with mediating the optimism. That means, the gratitude, through increased optimism, indirectly improves the marital satisfaction. There was no study investigating the indirect relationship between these variables. However, some studies examined the binary relationships of these variables. Positive direct effect of the gratitude on the optimism is consistent with the findings of previously conducted studies (Froh et al., 2008; Kirgiz, 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). The use of gratitude helps people adapt to the lack of positive and satisfactory life situations and learn to recognize the benefits and positive situations of the past as well as their present lives (Emmons & Mishra, 2011). Based on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2001), the gratitude has a role in the generation of positive emotions such as hope, forgiveness and optimism.

As gratitude is expressed, perceptual set is publishing the idea that others share in our welfare, which creates hope and optimism about having a benevolent world and the presence of helping people in life. Also, optimism had a positive direct effect on the marital satisfaction. This finding was in agreement with those of several previous studies (Gordon & Baucom, 2009; Imani, Kazemi Rezaie, Pirzadeh, Valikhani, & Kazemi Rezaie, 2015; Kim, Chopik, & Smith, 2014). other studies demonstrated that optimism is associated with increased positive interactions (Vollmann, Antoniw, Hartung, & Renner, 2011), reduced loneliness (Rius-Ottenheim et al., 2012), improved relationship quality (Assad, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007) in couples, and thereby increasing marital satisfaction.

A possible explanation for this might be that positive emotions broaden couples’ thoughts and prepare them for more flexible responses to future challenges, and in the long run, make satisfactory relationships. Optimist people have broader and more flexible behavioral responses such as accepting their current status, when confronted with the negative life events (Parise, Donato, Pagani, & Schoebi, 2017). Also, optimism acts as a protective factor in the relationship between couples and by reducing the attention to the behaviors and negative attitudes of the spouse, despite being aware of them, prevents the spouses from leaving the relationship and creates positive interactions and promotes intimacy between the couples (Winczewski, Bowen, & Collins, 2016).

The present study has several limitations; the use of self-report questionnaires that may be influenced by response bias and incorrect answers. Moreover, the results of the current study are limited to the married female teachers; they are not necessarily applicable to males or females of other statistical populations. Thus, future studies should take into account more diverse samples of different populations. The current study was cross-sectional. A longitudinal study can more certainly confirm the indirect relationships of gratitude, optimism, and marital satisfaction. Finally, the present study was conducted on females with normal marital relationships.

Therefore, due to the lack of studies, it is suggested that future researches should consider the role of gratitude in marital relationships associated with incompatibility and conflict. The current study showed a step into a further understanding of positive processes that can protect couples against marital dissatisfaction, and that can assist counselors to help couples in attaining and keeping the marital satisfaction. In pre-marriage counseling, the level of gratitude, as one of the criteria for choosing a spouse, can be considered by counselors. Also, it is suggested that in communication skills training and enrichment of couple’s relationships, gratitude should be considered as a communication skill, and through training and enhancement of gratitude in marital life, the optimism and marital satisfaction of the couples can be helped and increased.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this research. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information. Moreover, they were allowed to discontinue study participation as desired. Some of the obtained results are available to them upon request.

Funding

The present research is a part of first author’s Master Thesis, Sakineh Saeidi, Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (2766 Views)

1. Introduction

Marital satisfaction is a positive and pleasurable attitude that couples have about the diverse facet of marital relationship such as communication, personality issues, conflict resolution, financial issues, sexual relations, and children (Taniguchi, Freeman, Taylor, & Malcarne, 2006). Marital satisfaction is one of the main indications of success in marriage (Fredman et al., 2016). Satisfaction with marriage is influenced by multiple, often interacting variables, with roots in premarital cognitions and behaviors (Johnson & Anderson, 2013).The major focus of research on the factors affecting marital satisfaction is about the processes that weaken it in couples.

In contrast, positive factors that may contribute to the prosperity of couples’ relationships are less widely considered (Gordon & Baucom, 2009). Recently, with the rapid growth of the positive psychology movement, there is a growing interest in the positive facets of communicative function (Fincham, Beach, & Review, 2010; Gottman & Notarius, 2002; Segrin, 2006). Gratitude is one of the structures that some studies look at it as a basis for understanding the positive processes that occur in couples relationships (Lambert, Clark, Durtschi, Fincham, & Graham, 2010).

Gratitude is conceptualized as a subjective feeling of thankfulness and appreciation for life (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). As a psychological disposition, gratitude is described as a proneness to react with grateful emotions to other people’s generosity and the ways in which others supply positive experiences and outcomes in one’s life (McCullough, Emmons & Tsang, 2002). More precisely, gratitude is defined as “as a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (McCullough et al., 2002). Persons who are highly grateful often say the following: “I could not get what I have today without the help of others” or “I often think that because of the efforts of others, life has become much easier” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Research show that gratitude has important implications including higher level of prosocial behavior (McCullough et al., 2001), sense of coherence (Lambert, Graham, Fincham, Stillman, 2009), helping behavior (Li & Chow, 2015), mental health (Watkins, Grimm, & Kolts, 2004), life satisfaction (Robustelli & Whisman, 2018; Lambert, Fincham, Stillman, & Dean, 2009), and positive changes in negative situations (Lambert, Graham, Fincham, & Stillman, 2009), as well as lower level of perceived stress (Lee et al., 2018) and depression (Sirois & Wood, 2017; Lambert, Fincham, Stillman, 2012; Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008).

The focus of most definitions of gratitude is on the conception that a person is given positive things from a benevolent and benefactor with positive intention (McCullough et al., 2001). This definition addresses gratitude as a concept that specifically includes considerations in the relationship between couples. In fact, it is believed that gratitude is a stimulant or moral motive that helps people form close interpersonal relationships (Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008; McCullough, Kimeldorf, & Cohen, 2008). Studies consider the gratitude to be especially important in the establishment of social relationships, as well as vital to continuity and maintain close interpersonal relationships such as romantic relationships (Algoe, Gable, & Maisel, 2010; Gordon, Arnette, Smith, & Differences, 2011; Kubacka, Finkenauer, Rusbult, Keijsers, 2011).

Emmons and McCullough (Emmons & McCullough, 2003) state that gratitude is a form of love, and has an accelerating role in shaping emotional relationships among people. Similarly, other studies also found that gratitude is associated with stability in the relationship (Gable, Gonzaga, & Strachman, 2006), marital satisfaction, and the regulation of relationships (Schramm, Marshall, Harris, & Lee, 2005). Despite the potential benefits of gratitude for couples and marital satisfaction, little attention is paid to this field in Iran. The results of a study showed the effectiveness of gratitude intervention on life hope and happiness of couples (azargoon, kajbaf, & ghamarani, 2018). Therefore, due to the lack of studies, especially in Iran, the current study attempted to investigate the indirect effect of gratitude on the marital satisfaction.

Although some studies confirm the role of gratitude in marital satisfaction and other positive communicative outcomes; the mechanisms that link gratitude to marital satisfaction remains unclear and are not systematically addressed. A variable that links gratitude to marital satisfaction is optimism. Optimism, as well as gratitude, is one of the main concepts of the positive psychology. Optimism is a general expectancy of the occurrence of pleasant events in the future (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Optimism represents the tendency to believe that, in general, a person in life will experience positive outcomes in comparison with negative outcomes, and this belief refers to a sTable personality trait. Research shows that optimism is associated with a high level of commitment in interpersonal relationships (Carver & Segerstrom, 2010) and marital satisfaction (McNulty & Karney, 2004).

Marital satisfaction is a positive and pleasurable attitude that couples have about the diverse facet of marital relationship such as communication, personality issues, conflict resolution, financial issues, sexual relations, and children (Taniguchi, Freeman, Taylor, & Malcarne, 2006). Marital satisfaction is one of the main indications of success in marriage (Fredman et al., 2016). Satisfaction with marriage is influenced by multiple, often interacting variables, with roots in premarital cognitions and behaviors (Johnson & Anderson, 2013).The major focus of research on the factors affecting marital satisfaction is about the processes that weaken it in couples.

In contrast, positive factors that may contribute to the prosperity of couples’ relationships are less widely considered (Gordon & Baucom, 2009). Recently, with the rapid growth of the positive psychology movement, there is a growing interest in the positive facets of communicative function (Fincham, Beach, & Review, 2010; Gottman & Notarius, 2002; Segrin, 2006). Gratitude is one of the structures that some studies look at it as a basis for understanding the positive processes that occur in couples relationships (Lambert, Clark, Durtschi, Fincham, & Graham, 2010).

Gratitude is conceptualized as a subjective feeling of thankfulness and appreciation for life (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). As a psychological disposition, gratitude is described as a proneness to react with grateful emotions to other people’s generosity and the ways in which others supply positive experiences and outcomes in one’s life (McCullough, Emmons & Tsang, 2002). More precisely, gratitude is defined as “as a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (McCullough et al., 2002). Persons who are highly grateful often say the following: “I could not get what I have today without the help of others” or “I often think that because of the efforts of others, life has become much easier” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Research show that gratitude has important implications including higher level of prosocial behavior (McCullough et al., 2001), sense of coherence (Lambert, Graham, Fincham, Stillman, 2009), helping behavior (Li & Chow, 2015), mental health (Watkins, Grimm, & Kolts, 2004), life satisfaction (Robustelli & Whisman, 2018; Lambert, Fincham, Stillman, & Dean, 2009), and positive changes in negative situations (Lambert, Graham, Fincham, & Stillman, 2009), as well as lower level of perceived stress (Lee et al., 2018) and depression (Sirois & Wood, 2017; Lambert, Fincham, Stillman, 2012; Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008).

The focus of most definitions of gratitude is on the conception that a person is given positive things from a benevolent and benefactor with positive intention (McCullough et al., 2001). This definition addresses gratitude as a concept that specifically includes considerations in the relationship between couples. In fact, it is believed that gratitude is a stimulant or moral motive that helps people form close interpersonal relationships (Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008; McCullough, Kimeldorf, & Cohen, 2008). Studies consider the gratitude to be especially important in the establishment of social relationships, as well as vital to continuity and maintain close interpersonal relationships such as romantic relationships (Algoe, Gable, & Maisel, 2010; Gordon, Arnette, Smith, & Differences, 2011; Kubacka, Finkenauer, Rusbult, Keijsers, 2011).

Emmons and McCullough (Emmons & McCullough, 2003) state that gratitude is a form of love, and has an accelerating role in shaping emotional relationships among people. Similarly, other studies also found that gratitude is associated with stability in the relationship (Gable, Gonzaga, & Strachman, 2006), marital satisfaction, and the regulation of relationships (Schramm, Marshall, Harris, & Lee, 2005). Despite the potential benefits of gratitude for couples and marital satisfaction, little attention is paid to this field in Iran. The results of a study showed the effectiveness of gratitude intervention on life hope and happiness of couples (azargoon, kajbaf, & ghamarani, 2018). Therefore, due to the lack of studies, especially in Iran, the current study attempted to investigate the indirect effect of gratitude on the marital satisfaction.

Although some studies confirm the role of gratitude in marital satisfaction and other positive communicative outcomes; the mechanisms that link gratitude to marital satisfaction remains unclear and are not systematically addressed. A variable that links gratitude to marital satisfaction is optimism. Optimism, as well as gratitude, is one of the main concepts of the positive psychology. Optimism is a general expectancy of the occurrence of pleasant events in the future (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Optimism represents the tendency to believe that, in general, a person in life will experience positive outcomes in comparison with negative outcomes, and this belief refers to a sTable personality trait. Research shows that optimism is associated with a high level of commitment in interpersonal relationships (Carver & Segerstrom, 2010) and marital satisfaction (McNulty & Karney, 2004).

Couples with a pessimistic view are heavily exposed to emotional conquest; (73.5%) of such couples have disruptive relationships, (70.4%) have low responsibility, and (62.2%) are unable to resolve marital conflicts (Henry, Berg, Smith, & Florsheim, 2007). Gratitude can affect optimism. As gratitude is expressed, perceptual set is publishing the idea that others share in our welfare, which creates hope and optimism about having a benevolent world and the presence of helping people in life (Fredrickson, 2001). Also, gratitude predicts hope and happiness (Witvliet, Richie, Root Luna & Van Tongeren, 2019) and gratitude interventions show an increase in happiness (Dickerhoof, 2007; Kirgiz, 2007; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005) and optimism (Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, 2008) in subjects. Finally, the results of another study showed that gratitude strategies increase optimism in Iranian university students (Lashani, Shaeiri, Asghari-Moghadam, & Golzari, 2012).

With regard to the above, it is expected that gratitude through increased optimism has a positive indirect effect on marital satisfaction. No research examined this issue. Overall, considering the literature and the above, the current study aimed to investigate the direct effect of gratitude on the marital satisfaction in married female teachers. In addition, the present study intended to evaluate the indirect effect of gratitude on marital satisfaction through optimism. For this purpose, a hypothesized model was developed, which is shown in Figure 1.

With regard to the above, it is expected that gratitude through increased optimism has a positive indirect effect on marital satisfaction. No research examined this issue. Overall, considering the literature and the above, the current study aimed to investigate the direct effect of gratitude on the marital satisfaction in married female teachers. In addition, the present study intended to evaluate the indirect effect of gratitude on marital satisfaction through optimism. For this purpose, a hypothesized model was developed, which is shown in Figure 1.

2. Methods

The current cross-sectional study using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted on all female married teachers in Sabzevar city, Iran (N=2400). The cluster sampling method was used to select the sample. In order to determine the sample size, in structural equation modeling, 5 to 10 subjects were considered for each observed variable (Bentler & Chou, 1987; Kline, 2011). However, 250 questionnaires were distributed among the participants due to the possibility of loss and the existence of outliers. Finally, after deletion of incomplete questionnaires and removing the univariate and multivariate outliers by z-values and Mahalanobis distance, 241 questionnaires were included in the final analysis. The inclusion criteria were providing informed consent for participation in the research, passing at least two years of married life, having no addiction or drug abuse, lacking any serious illness or a chronic mental disorder or family acute crisis. The exclusion criteria comprised returning incomplete or distorted answers. Three questionnaires were used to collect the research data as follows:

ENRICH Marital Satisfaction (EMS) scale: the ENRICH (evaluation and nurturing relationship issues, communication, and happiness) developed by Olson, Fournier, and Druckman (Olson, Fournier, & Druckman, 1987) is used for evaluating potential areas of problem and recognizing areas of power and enrichment of marital relationships. Olson et al., (1987) confirmed the psychometric properties of this scale (α=0.92). A short version of this scale, whose psychometric properties were confirmed in the Iranian population (Soleimanian, 1994), was used in the current study (α=0.84). The scale consists of 47 items and nine sub-scales: personality issues, communication, resolution conflict, financial management, leisure activities, sexual relationship, children and parenting, family and friends, and religious orientation. Response range is on a Likert-type scale from 1 (entirely agree) to 5 (entirely disagree).

Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6): GQ-6 is a 6-item measure developed by McCullough et al., (2002) to evaluate experiences and expressions of gratefulness and appreciation in daily life, as well as feelings about receiving them from others. Responses were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two items were reversely coded. A higher score indicated a greater level of grateful disposition in individuals. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire are reported well, in many studies and in different cultural settings; Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the six-item totals range from .76 to .84. Scores on the GQ-6 correlate substantially with other measures hypothesized to assess the extent to which people experience gratitude in daily life (McCullough et al., 2002; Neto, 2007; Wei, Wu, Kong, & Wang, 2011). This six-item measure has good psychometric properties in Iranian population (Aghababai, Farahani, & Fazeli Mehr Abādi, 2010).

Life Orientation Test- revised (LOT-R): The LOT-R is a 10-item self-report measure that assesses optimism versus pessimism developed by Scheier, Carver, & Bridges. (1994). Three items measure optimism, three items measure pessimism, and there are four filler items. Response range is on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The overall score was computed by adding the raw scores of the optimism subscale with the inverted pessimism raw scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the entire 6 items of the scale was 0.78, suggesting that the scale had an accepTable level of internal consistency. The test-retest correlations were 0.68, 0.60, 0.56 and 0.79, suggesting that the scale was sTable across time (Scheier et al., 1994; Schou, Ekeberg, Ruland, Sandvik, & Kåresen et al., 2004; Segerstrom, Evans, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2011). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72, and test-retest correlations were 0.87 in the Persian version of this questionnaire (Kajbf, Oraizi, & Khodbakhshi, 2006).

After selecting the sample, questionnaires were distributed among married female teachers in the selected schools and high schools. In the beginning of the questionnaire, the study objectives, its importance, and the need for honesty in responses were explained to the participants. The informed consent was obtained from the subjects. The sample provided and signed a written consent form before administering the questionnaires. The hypothesized model was tested using AMOS 24, with maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was measured based on six indicators including the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Incremental Fit Index (IFI). Indirect effects were tested by bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals in Preacher and Hayes’ Macro program (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

3. Results

The participants aged 26-50 years (M=40.32, SD=5.18) with duration of marriage of 2-18 years (M=6.68, SD=0.85) and 0-5 children (M=2.16, SD=1.06). The correlation matrix means and standard deviations of variables are presented in Table 1.

According to Table 1, the Mean±SD scores of the gratitude, optimism, and marital satisfaction were 26.89±4.06, 17.61±3.88, and 163.79±20.38, respectively. The gratitude was positively correlated with optimism and marital satisfaction (p<0.01). Also, there was a significant positive relationship between optimism and marital satisfaction (p<0.01). The result of model fit, using SEM is shown in Table 2.

According to Table 2, some of the fit indices (AGFI, RMSEA) had good fit with the data in the hypothesized model, and indicated the needs to be modified. Therefore, in order to fit better among the modification indices proposed by AMOS-24, two of these modifications were made; the two paths errors of marital satisfaction (“Children and parenting” to “Family and Friends” and “Leisure and Activities” to “sexual and relationship”) were correlated. The result of the recent modifications was the second model or the final modified model. As shown in Table 2, fit indices indicated that the best fit to the data was obtained in the final model. Figure 2 shows the final model and path coefficients (β) between variables.

The final model represents a positive direct effect of the gratitude on marital satisfaction (β=0.32, p<0.05), optimism (β=0.57, p<0.05), and a positive direct effect of optimism on marital satisfaction (β=0.50, p<0.05) (Figure 2). The results of indirect effects using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals in Preacher and Hayes’ Macro program showed in Table 3.

Table 3 showed that the lower and upper confidence intervals were 0.85 and 1.74, respectively. Therefore, this confidence interval does not include zero, hence, there is a significant indirect effect. In other words, the results of Table 3 show a positive indirect effect of the gratitude on the marital satisfaction with mediating of the optimism.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed investigating the direct and indirect effects of gratitude and optimism on marital satisfaction using a structural equation modeling approach. The final model showed that the values of indices were desirable and the model had a good fit with the data. The results indicated that gratitude was positively associated with marital satisfaction. These results were consistent with several previous findings (Algoe et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2011; Schramm et al., 2005). Also, other studies demonstrated that gratitude is associated with improvement of relationship, intimacy, and sense of security in the relationship (Gordon, Impett, Kogan, Oveis, & Keltner, 2012). Another study found that gratitude is associated with a belief to find more chance to achieve the important goals of life in the marital relationship (Feeney, 2004). A possible explanation for these findings might be that gratitude assists couples to create positive resources; therefore, when couples encounter negative events in their relationships, they can concentrate on the positive manners already interacted and thus prevent the negative interactions that may occur in their relationship (Fredrickson, 2004).

Furthermore, the ability to draw previous positive experiences within the relationship when couples face negative events may enable them to see the good in the relationship and present higher levels of marital satisfaction. Gratitude can provide the relationship with a positive environment where couples are more conscious of and thankful for the good things that exist in the marriage. This consciousness allows couples to tend to the positive traits each possess, the positive manners in which they create the marriage work, the positive manners in which they care for one another, and the positive benefits they get. Therefore, higher levels of positivity between couples may associate with increases in marital satisfaction. Also, gratitude can increase marital satisfaction by increasing levels of happiness (Seligman et al., 2005), life satisfaction (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004), and positive effect (Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003).

The final model showed a positive indirect effect of the gratitude on the marital satisfaction with mediating the optimism. That means, the gratitude, through increased optimism, indirectly improves the marital satisfaction. There was no study investigating the indirect relationship between these variables. However, some studies examined the binary relationships of these variables. Positive direct effect of the gratitude on the optimism is consistent with the findings of previously conducted studies (Froh et al., 2008; Kirgiz, 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). The use of gratitude helps people adapt to the lack of positive and satisfactory life situations and learn to recognize the benefits and positive situations of the past as well as their present lives (Emmons & Mishra, 2011). Based on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2001), the gratitude has a role in the generation of positive emotions such as hope, forgiveness and optimism.

As gratitude is expressed, perceptual set is publishing the idea that others share in our welfare, which creates hope and optimism about having a benevolent world and the presence of helping people in life. Also, optimism had a positive direct effect on the marital satisfaction. This finding was in agreement with those of several previous studies (Gordon & Baucom, 2009; Imani, Kazemi Rezaie, Pirzadeh, Valikhani, & Kazemi Rezaie, 2015; Kim, Chopik, & Smith, 2014). other studies demonstrated that optimism is associated with increased positive interactions (Vollmann, Antoniw, Hartung, & Renner, 2011), reduced loneliness (Rius-Ottenheim et al., 2012), improved relationship quality (Assad, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007) in couples, and thereby increasing marital satisfaction.

A possible explanation for this might be that positive emotions broaden couples’ thoughts and prepare them for more flexible responses to future challenges, and in the long run, make satisfactory relationships. Optimist people have broader and more flexible behavioral responses such as accepting their current status, when confronted with the negative life events (Parise, Donato, Pagani, & Schoebi, 2017). Also, optimism acts as a protective factor in the relationship between couples and by reducing the attention to the behaviors and negative attitudes of the spouse, despite being aware of them, prevents the spouses from leaving the relationship and creates positive interactions and promotes intimacy between the couples (Winczewski, Bowen, & Collins, 2016).

The present study has several limitations; the use of self-report questionnaires that may be influenced by response bias and incorrect answers. Moreover, the results of the current study are limited to the married female teachers; they are not necessarily applicable to males or females of other statistical populations. Thus, future studies should take into account more diverse samples of different populations. The current study was cross-sectional. A longitudinal study can more certainly confirm the indirect relationships of gratitude, optimism, and marital satisfaction. Finally, the present study was conducted on females with normal marital relationships.

Therefore, due to the lack of studies, it is suggested that future researches should consider the role of gratitude in marital relationships associated with incompatibility and conflict. The current study showed a step into a further understanding of positive processes that can protect couples against marital dissatisfaction, and that can assist counselors to help couples in attaining and keeping the marital satisfaction. In pre-marriage counseling, the level of gratitude, as one of the criteria for choosing a spouse, can be considered by counselors. Also, it is suggested that in communication skills training and enrichment of couple’s relationships, gratitude should be considered as a communication skill, and through training and enhancement of gratitude in marital life, the optimism and marital satisfaction of the couples can be helped and increased.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this research. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information. Moreover, they were allowed to discontinue study participation as desired. Some of the obtained results are available to them upon request.

Funding

The present research is a part of first author’s Master Thesis, Sakineh Saeidi, Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Aghababai, N., Babai Farahani, H., & Fazeli Mehr Abadi, A. (2010). [Measuring gratitude among university and religious students: An enquiry hnti the psychometric features of the gratitude questionnaire (Persian)]. Journal of Studies in Islam and Psychology, 4(6), 75-88.

- Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217-33. [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x]

- Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8(3), 425-9. [DOI:10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Assad, K. K., Donnellan, M. B., & Conger, R. D. (2007). Optimism: An enduring resource for romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(2), 285-97. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285] [PMID]

- Azargoon, H., Kajbaf, M., & Ghamarani, A. (2018). [The effectiveness of emmons gratitude training on life hope and happiness young couples in Neishabour city (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research, 14(1), 23-37.

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78-117. [DOI:10.1177/0049124187016001004]

- Carver CS, S. M., Segerstrom SC. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879-89. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

- D Dickerhoof, R. M. (2007). Expressing optimism and gratitude: A longitudinal investigation of cognitive strategies to increase well-being. California: University of California.

- Emmons, R. A., & Mishra, A. (2011). Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. In k. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, M. F. Steger, (Eds.), Designing Positive Psychology: Taking Stock and Moving Forward (pp. 248-62). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195373585.003.0016]

- Feeney, B. C. (2004). A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 631-48. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631] [PMID]

- Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. (2010). Of memes and marriage: Toward a positive relationship science. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(1), 4-24. [DOI:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00033.x]

- Fredman, S. J., Pukay-Martin, N. D., Macdonald, A., Wagner, A. C., Vorstenbosch, V., & Monson, C. M. (2016). Partner accommodation moderates treatment outcomes for couple therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(1), 79-87. [DOI:10.1037/ccp0000061] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fredrickson, B. J. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online. [DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0008]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-26. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218]

- Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 46(2), 213-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005] [PMID]

- Gable, S. L., Gonzaga, G. C., & Strachman, A. (2006). Will you be there for me when things go right? Supportive responses to positive event disclosures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 904-17. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.904] [PMID]

- Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2012). To have and to hold: Gratitude promotes relationship maintenance in intimate bonds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(2), 257-74. [DOI:10.1037/a0028723] [PMID]

- Gordon, C. L., & Baucom, D. H. (2009). Examining the individual within marriage: Personal strengths and relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 16(3), 421-35. [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01231.x]

- Gordon, C. L., Arnette, R. A., Smith, R. E. J. P., & Differences, I. (2011). Have you thanked your spouse today? Felt and Expressed Gratitude Among Married Couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 339-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.012]

- Gottman, J. M., & Notarius, C. I. (2002). Marital research in the 20th century and a research agenda for the 21st century. Family Process, 41(2), 159-97. [DOI:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41203.x]

- Henry, N. J., Berg, C. A., Smith, T. W., & Florsheim, P. (2007). Positive and negative characteristics of marital interaction and their association with marital satisfaction in middle-aged and older couples. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 428-41. [DOI:10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.428] [PMID]

- Imani, M., Kazemi Rezaie, S. A., Pirzadeh, H., Valikhani, A., & Kazemi Rezaie, S. V. (2015). [The mediating role of self-efficacy and optimism in the relation between marital satisfaction and life satisfaction among female teachers in Nahavand (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 5(3), 50-71.

- Johnson, M. D., & Anderson, J. R. (2013). The longitudinal association of marital confidence, time spent together, and marital satisfaction. Family Process, 52(2), 244-56. [DOI:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01417.x] [PMID]

- Kajbf, M., Oraizi, H., & Khodbakhshi, M. (2006). Standardization, reliability, and validity of optimism scale in esfahan and a survey of relationship between optimism, selfmastery, and depression. Psychological Studies, 2(1-2), 51-68.

- Kim, E. S., Chopik, W. J., & Smith, J. (2014). Are people healthier if their partners are more optimistic? The dyadic effect of optimism on health among older adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(6), 447-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.104] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kirgiz, O. G. (2007). Effects of gratitude on subjective well-being, self-construal, and memory. Washington: American University.

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In M. Williams, W. P. Vogt (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods (pp. 246-54). Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446268261.n31]

- Kubacka, K. E., Finkenauer, C., Rusbult, C. E., & Keijsers, L. (2011). Maintaining close relationships: Gratitude as a motivator and a detector of maintenance behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1362-75. [DOI:10.1177/0146167211412196] [PMID]

- Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D., & Graham, S. M. (2010). Benefits of expressing gratitude: Expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychological Science, 21(4), 574-80. [DOI:10.1177/0956797610364003] [PMID]

- Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2012). Gratitude and depressive symptoms: The role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 26(4), 615-33. [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2011.595393] [PMID]

- Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 32-42. [DOI:10.1080/17439760802216311]

- Lambert, N. M., Graham, S. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2009). A changed perspective: How gratitude can affect sense of coherence through positive reframing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 461-70. [DOI:10.1080/17439760903157182]

- Lashani, Z., Shaeiri, M. R., Asghari-Moghadam, M. A., & Golzari, M. (2012). [Effect of gratitude strategies on positive affectivity, happiness and optimism (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 157-66.

- Lee, J. Y., Kim, S. Y., Bae, K. Y., Kim, J. M., Shin, I. S., Yoon, J. S., et al., (2018). The association of gratitude with perceived stress and burnout among male firefighters in Korea. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 205-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.010]

- Li, K. K., & Chow, W. Y. (2015). Religiosity/spirituality and prosocial behaviors among Chinese Christian adolescents: The mediating role of values and gratitude. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(2), 150-61. [DOI:10.1037/a0038294]

- McCullough, M. E., & Emmons, R. A. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377-89. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377]

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112-27. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112]

- McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. J. P. b. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249-66. [DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.127.2.249] [PMID]

- McCullough, M. E., Kimeldorf, M. B., & Cohen, A. D. (2008). An adaptation for altruism: The social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 281-5. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00590.x]

- McNulty, J. K., & Karney, B. R. (2004). Positive expectations in the early years of marriage: Should couples expect the best or brace for the worst? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 729. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.729] [PMID]

- Neto, F. (2007). Forgiveness, personality and gratitude. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(8), 2313-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.010]

- Olson, D. H., Fournier, D. G., & Druckman, J. M. (1987). Counselor’s manual for Prepare/Enrich (Rev. ed). Minneapolis: Prepare/Enrich.

- Parise, M., Donato, S., Pagani, A. F., & Schoebi, D. (2017). Keeping calm when riding the rapids: Optimism and perceived partner withdrawal. Personal Relationships, 24(1), 131-45. [DOI:10.1111/pere.12172]

- Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-19. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods, 40(3), 879-91. [DOI:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879]

- Rius-Ottenheim, N., Kromhout, D., van der Mast, R. C., Zitman, F. G., Geleijnse, J. M., & Giltay, E. J. (2012). Dispositional optimism and loneliness in older men. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(2), 151-9. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2701] [PMID]

- Robustelli, B. L., & Whisman, M. A. (2018). Gratitude and life satisfaction in the United States and Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 41-55. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-016-9802-5]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219-47. [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219] [PMID]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063-78. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063]

- Schou, I., Ekeberg, Ø., Ruland, C. M., Sandvik, L., & Kåresen, R. (2004). Pessimism as a predictor of emotional morbidity one year following breast cancer surgery. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 13(5), 309-20. [DOI:10.1002/pon.747] [PMID]

- Schramm, D. G., Marshall, J. P., Harris, V. W., & Lee, T. R. (2005). After “I do”: The newlywed transition. Marriage & Family Review, 38(1), 45-67. [DOI:10.1300/J002v38n01_05]

- Segerstrom, S. C., Evans, D. R., & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A. (2011). Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the Life Orientation Test-Revised: Method and meaning. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(1), 126-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.007]

- Segrin, C. (2006). Invited article: Family interactions and well-being: Integrative perspectives. The Journal of Family Communication, 6(1), 3-21. [DOI:10.1207/s15327698jfc0601_2]

- Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410-21. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410] [PMID]

- Sirois, F. M., & Wood, A. M. (2017). Gratitude uniquely predicts lower depression in chronic illness populations: A longitudinal study of inflammatory bowel disease and arthritis. Health Psychology, 36(2), 122-32. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000436] [PMID]

- Soleimanian, AA. (1994). [The study of irrational thinking based on cognitive approach to marital dissatisfaction (Persian)] [MA. thesis). Tehran: Tarbiat Moalem University.

- Taniguchi, S. T., Freeman, P. A., Taylor, S., & Malcarne, B. (2006). A study of married couples’ perceptions of marital satisfaction in outdoor recreation. Journal of Experiential Education, 28(3), 253-6. [DOI:10.1177/105382590602800309]

- Vollmann, M., Antoniw, K., Hartung, F. M., & Renner, B. (2011). Social support as mediator of the stress buffering effect of optimism: The importance of differentiating the recipients’ and providers’ perspective. European Journal of Personality, 25(2), 146-54. [DOI:10.1002/per.803]

- Watkins, P. C., Grimm, D. L., & Kolts, R. (2004). Counting your blessings: Positive memories among grateful persons. Current Psychology, 23(1), 52-67. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-004-1008-z]

- Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431-51. [DOI:10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.431]

- Wei, C., Wu, H. T., Kong, X. N., & Wang, H. (2011). Revision of Gratitude Questionnaire-6 in Chinese adolescent and its validity and reliability. Chinese Journal of School Health, 32(10), 1201-2.

- Winczewski, L. A., Bowen, J. D., & Collins, N. L. J. P. s. (2016). Is empathic accuracy enough to facilitate responsive behavior in dyadic interaction? Distinguishing ability from motivation. 27(3), 394-404. [DOI:10.1177/0956797615624491] [PMID]

- Witvliet, C. V., Richie, F. J., Root Luna, L. M., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2019). Gratitude predicts hope and happiness: A two-study assessment of traits and states. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(3), 271-82. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2018.1424924]

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. J. J. o. R. i. P. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 854-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2018/09/15 | Accepted: 2019/09/3 | Published: 2019/09/3

Received: 2018/09/15 | Accepted: 2019/09/3 | Published: 2019/09/3

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |