Volume 7, Issue 1 (Winter 2019)

PCP 2019, 7(1): 1-10 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tamannaeifar M, Shahmirzaei S. Prediction of Academic Resilience Based on Coping Styles and Personality Traits. PCP 2019; 7 (1) :1-10

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-579-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-579-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Kashan, Kashan, Iran. , tamannai@kashanu.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Kashan, Kashan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Kashan, Kashan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 631 kb]

(5952 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (14078 Views)

Full-Text: (7258 Views)

1. Introduction

University students experience various stressors and encounter many challenges in this new educational setting (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015) such as adjustment to an environment different from high school; management of their expenses (Rahat & Ilhan, 2016); adaptation to a new culture, new communication style and relationships; independence from their parents; preparation for the future (Kim, 2011); and development of new friendships (Salami, 2011). Therefore, they may experience anxiety, depression, extreme emotional states, failure and academic dropout due to excessive stress (Banyard & Cantor, 2004; Bülbül, 2012; Dyson & Renk, 2006; Şimşek, 2013; Thurber & Walton, 2012).

The theory of resilience tries to explain academic achievement in students who encounter negative psychological and environmental situations (Reis, Colbert, & Hébert, 2005). Adaptation and academic success at university require high resilience (Munro & Pooley, 2009), thereby justifying considerable research on factors that protect and foster resilience throughout university life (De la Fuente, Cardelle-Elawar, Martínez-Vicente, Zapata, & Peralta, 2013). Psychologists and educators have paid considerable attention to the construct of resilience (Chen, 2016), which is an original and integrative concept in the social and behavioral sciences (Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). However, ‘resilience’ is still an ambiguous concept and reaching a precise definition for it is difficult (Panter-Brick & Leckman, 2013).

There has been much debate over the nature of resilience; i.e. whether it should be considered as a cause or outcome as well as a trait or a process (Reich, Zautra, & Hall, 2010). In the present study, resilience is defined as a trait and considered as an individual’s capacity and positive attribute that help efficiently cope with environmental stressors and protect from psychopathology in facing challenges (Chen, 2016; Eley et al., 2013).

Resilience is defined as the capacity of maintaining stable functioning and making adjustments in the face of great adversity (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2003; Garcı´a-Secades, Molinero, Salguero, & Ma´rquez, 2014). The presence or experience of adversity and the subsequent positive adaptation are two important aspects of resilience (Secades et al., 2016). Recent research has emphasized the positive contribution of resilience to adjustment in encountering difficult conditions (Theron & Theron, 2013; Werner, 2012; Yates & Grey, 2012). Resilience reduces anxiety and depression (Khadem, Motevalli Haghi, Ranjbari, & Mohammadi, 2017) and individuals with high resilience adjust more successfully to stressors than those with low resilience (Luthar, 2006).

Researchers have discussed different types of resilience, including academic, emotional, and behavioral resilience. Recently, they have paid special attention to academic resilience. According to Wang and Gordon (2012) academic resilience refers to the increasing likelihood of academic success regardless of the adversities and challenges in the environment brought about by new experiences, conditions, and traits (Wang & Gordon, 2012). Many studies have focused on educational resilience and improvements in the education of students at risk of academic dropout and failure (Rojas, 2015).

According to the current theories, resilience is as a multidimensional construction which consists constitutional variables like temperament and personality as well as special skills, such as active problem-solving that help people to cope well with life events (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, 2006). Academic resilience is affected by both external protective factors (e.g. social supports and opportunities available in the family, school, community, and peers) and internal protective factors (e.g. personality traits, skills, attitudes, beliefs, and coping strategies). Focused on internal protective factors, the present study seeks to investigate the role of coping styles and personality traits in the academic resilience.

In stressful situations, individuals use different strategies to cope with their stress (Ahn, 2014). Successful coping is intended to mediate the potentially harmful effects of experiencing unpleasant emotional states. Moreover, even in facing with the same type of stress, individuals use different coping styles that could be due to their inherent preferences rather than the causal differences in individual behaviors (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015).

In line with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) model and Endler and Parker’s (2015) classification, the present study examines problem-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance coping styles. Problem-oriented style aim to cognitively reconstruct the problem or alter the situation with efforts to solve the problem or reduce its effects by taking action. Emotion-oriented style aims to diminish stress via emotional reactions (e.g. self-blaming), self-preoccupation, and or imagining. Avoidance styles are to avoid the stressful conditions through social diverting or distraction of oneself with other conditions or tasks (Endler & Parker’s, 2015).

According to Skodol (2010), resilience and coping have mutual relationship and are interrelated; each of them alone or in combination is likely to make better or worse the effect of unfavorable experiences. Moreover, cognitive reappraisal, positive emotionality, and active coping styles are all considered as psychosocial factors related to resilience and promote efficient coping (Feder, Nestler, Westphal, & Charney, 2010). Students with inefficient coping capability, have poor cognitive flexibility, low self-control, and inability to regulate their emotions. Also, they are unable to pursue their educational goals and environmental demands, have low academic achievement, and suffer from learning problems (Piers, 2004; Haeussler, 2013). A few studies have explored the relationship between resilience and coping styles (Chen, 2016).

Dumont and Provost (1999) found that resilient people scored high on problem-oriented style. The findings of another study indicated significant relationship between emotion-oriented style and low resilience, also there was not a positive association between task-oriented coping style and resilience, but task-oriented coping acted as a mediator to make association between conscientiousness and resilience (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006). Accordingly, resilience is positively associated to task-oriented style and negatively related to emotion-oriented style (Chen, 2016).

Moreover, by understanding the people’s personality traits, it is possible to predict their behavior. Individual’s personality help them cope in unique ways in stressful situations (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015). Much evidence indicates that personality traits impact resilience among the adolescents (Fayombo, 2010). Literature suggests that the big five personality traits, i.e. neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are five empirically-approved dimensions of personality.

It seems that resilience has a negative correlation with neuroticism as it reduces vulnerability to negative emotions and has strong relationship with depression and anxiety (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Bienvenu & Stein, 2003). In contrast, resilience has a positive association with extraversion, because extraverts tend to experience positive emotions, form close relationships to others, and seek social interactions (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Social support and positive emotions have been related to resilience (Luthar et al., 2006; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Bonanno, 2004). Additionally, resilience has a moderate relationship with conscientiousness, as conscientious people have high self-efficacy and use an efficient problem-solving style to cope with stressful situations.

Campbell-Sills et al. (2006) study supports the negative relationship between resilience and neuroticism and positive association between resilience with conscientiousness and extraversion. Also, Nakaya, Oshio, and Kaneko (2006) found negative relationship between resilience and neuroticism as well as positive correlations between resilience with the extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness traits. Similarly, they used big five personality traits to distinguish between well-adjusted and vulnerable personality profiles. Annalakshmi (2007) showed that resilience was positively associated with the well-adjusted personality profile obtained. In addition, resilient individuals are better adjusted and psychologically healthier (Friborg, Barlaug, Martinussen, Rosenvinge, & Hjemdal, 2005). The findings of Fayombo (2010) study indicate the positive relationship between the personality traits (extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and resilience. These personality traits promote resilience in a person. However, neuroticism was found to be negatively associated with psychological resilience and weakens it.

Although the relationship of coping styles and personality traits to resilience has been identified, there is still scanty research on the relationship among personality traits, coping styles and academic resilience. Thus, the present study aims to examine the relationship between personality traits and coping styles, in one hand, and academic resilience, on the other hand. In addition, it seeks to determine contribution of personality traits and coping styles to academic resilience. In fact, this study provides fundamental data to prepare students intervention strategies for enhancing academic resilience through investigating its influencing factors.

2. Methods

This research was a cross-sectional study. The study population include University of Kashan’s graduated students from February to March 2017. The sample consists of 368 (253 females and 115 males, aged: 18 to 22 years) students selected using a random multistage cluster sampling method. In the first step of sampling, four faculties of University of Kashan were randomly selected. Then, some classes were randomly selected as the final cluster, and questionnaires were distributed among the students of the classes. The inclusion criteria were being 18-22 years old (BSc. students) and consent for participation in the study.

The exclusion criterion was incomplete or distorted answers. A total of 390 questionnaires were returned. Of them, 22 were incomplete and distorted questionnaires. Finally, 368 questionnaires were used for data analysis. The study data were collected using academic resilience scale, coping inventory for stressful situation and neo personality traits inventory. Step-by-step regression analysis was used to analyze the data. It is noteworthy that the objectives of the study were fully explained to the participants, and written informed consents were obtained from those who agreed to participate in the study. To maintain anonymity, the participants’ personal information were excluded.

Academic Resilience Scale (ARS), developed by Martin, & Marsh (2003), is a 6-item self-report instrument to measure student’s resilience in dealing with challenges, obstacles, and stressful situations (Martin & Marsh, 2003). Respondents should rate themselves on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cassidy (2016) study findings demonstrated that the scale has good internal reliability and construct validity. The Cronbach α coefficient of this questionnaire has been reported 85% to 88%. The reliability and validity of this scale has been confirmed in the Iranian context by Hashemi (2011). In the present study, the Cronbach α was obtained as 0.84.

Endler and Parker (1990) designed Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation Questionnaire to evaluate individuals’ coping skills. It contains 48 self-report items on Likert-scale format ranging from 1=never to 5=extreme. They have reported the reliability coefficients of 0.90, 0.85, and 0.82 for problem-focused coping style, emotion-focused coping style, and avoidant coping style, respectively. Michaeli Manee (2010) reported its Cronbach α as 0.64 for problem-focused coping style, 0.60 for emotion-focused coping style, and 0.61 for avoidant coping style. In the present study, the reliability coefficients for problem-focused coping style, emotion-focused coping style, and avoidant coping style were calculated as 0.87, 0.82, and 0.79, respectively.

The 60-item Neo Personality Traits Inventory (NEO-FFI) was developed to provide a concise measure of the 5 basic personality traits, namely, neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreement, and conscientiousness (Costa & McCrae, 2004). In this questionnaire, the answer to each item is scored on a 5-point Likert-type format. Several studies have confirmed the reliability and validity of this scale. Costa and McCrae (1992) reported an internal consistency ranges from 0.68 to 0.86. In a study conducted by Sami et al. (2015), the overall reliability of this questionnaire was calculated as 0.83. Valikhani et al. (2017) reported the Cronbach α coefficient for each scale as: 0.82 (neuroticism), 0.79 (extroversion), 0.60 (openness to experience), 0.69 (agreement), and 0.75 (conscientiousness). In the present study, Cronbach α for neuroticism, extraversion, and openness to experience, agreement and conscientiousness were computed 0.81, 0.76, 0.79, 0.74 and 0.79, respectively.

3. Results

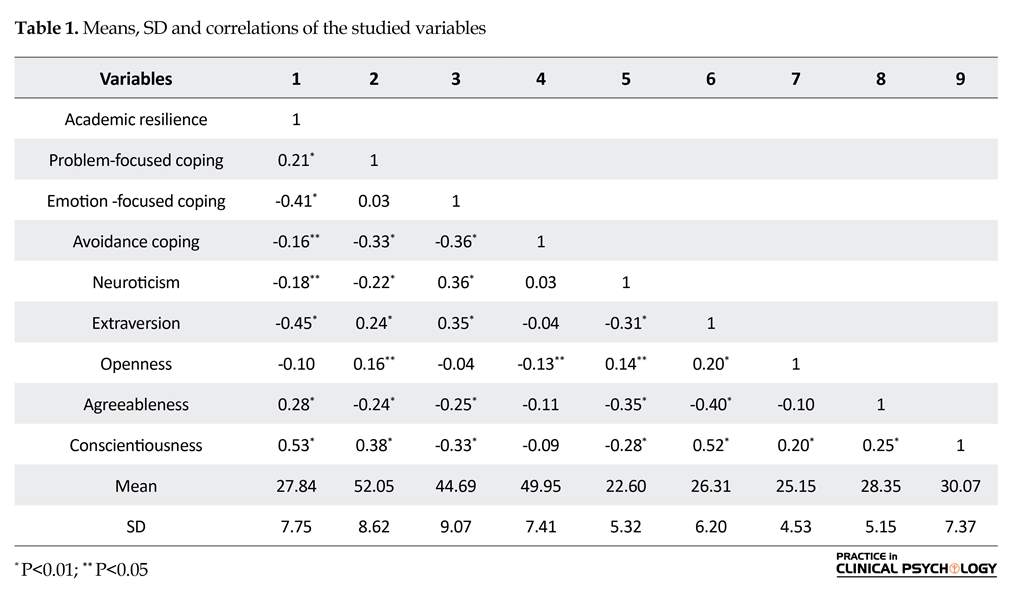

To investigate the relationship between coping styles and personality traits, in one hand, and academic resilience, on the other hand, the Pearson correlation coefficients were computed. In order to determine the contributions of coping styles and personality traits in predicting academic resilience, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out. The predictors in the analysis were coping styles and personality traits and the predicted variable was the academic resilience. The results of the descriptive statistics (Mean and standard deviation) for all variables and correlations are presented in Table 1. There were correlations between the academic resilience and problem-focused coping style (r=-0.21, P<0.01), emotion-focused coping style (r=0.41, P<0.01), and avoidance coping style (r=0.16, P<0.05).

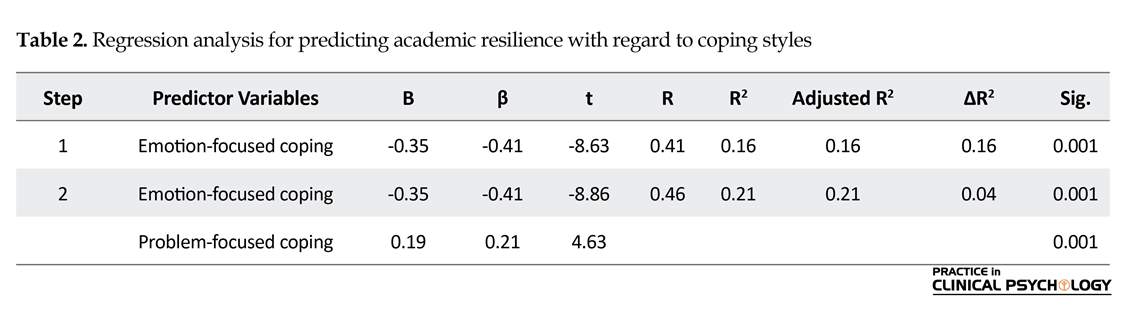

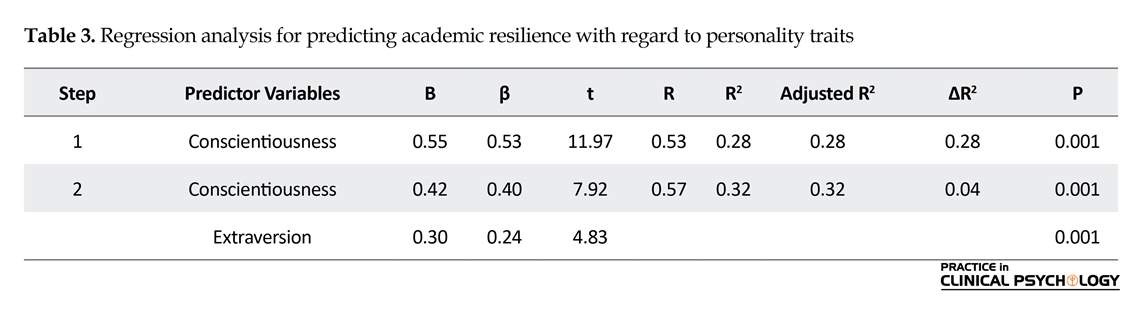

Moreover, results indicate correlation between academic resilience and neuroticism (r=-0.18, P<0.05), extraversion (r=0.45, P<0.01), openness (r=0.10, not specified), agreeableness (r=0.28, P<0.01), and conscientiousness (r=0.53, P<0.01). Based on the regression analysis results (Tables 2 and 3), coping styles (emotion-focused and problem-focused styles) predicted 21% of academic resilience variance, and personality traits (conscientiousness and extraversion) predicted 32% of academic resilience variance.

University students experience various stressors and encounter many challenges in this new educational setting (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015) such as adjustment to an environment different from high school; management of their expenses (Rahat & Ilhan, 2016); adaptation to a new culture, new communication style and relationships; independence from their parents; preparation for the future (Kim, 2011); and development of new friendships (Salami, 2011). Therefore, they may experience anxiety, depression, extreme emotional states, failure and academic dropout due to excessive stress (Banyard & Cantor, 2004; Bülbül, 2012; Dyson & Renk, 2006; Şimşek, 2013; Thurber & Walton, 2012).

The theory of resilience tries to explain academic achievement in students who encounter negative psychological and environmental situations (Reis, Colbert, & Hébert, 2005). Adaptation and academic success at university require high resilience (Munro & Pooley, 2009), thereby justifying considerable research on factors that protect and foster resilience throughout university life (De la Fuente, Cardelle-Elawar, Martínez-Vicente, Zapata, & Peralta, 2013). Psychologists and educators have paid considerable attention to the construct of resilience (Chen, 2016), which is an original and integrative concept in the social and behavioral sciences (Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). However, ‘resilience’ is still an ambiguous concept and reaching a precise definition for it is difficult (Panter-Brick & Leckman, 2013).

There has been much debate over the nature of resilience; i.e. whether it should be considered as a cause or outcome as well as a trait or a process (Reich, Zautra, & Hall, 2010). In the present study, resilience is defined as a trait and considered as an individual’s capacity and positive attribute that help efficiently cope with environmental stressors and protect from psychopathology in facing challenges (Chen, 2016; Eley et al., 2013).

Resilience is defined as the capacity of maintaining stable functioning and making adjustments in the face of great adversity (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2003; Garcı´a-Secades, Molinero, Salguero, & Ma´rquez, 2014). The presence or experience of adversity and the subsequent positive adaptation are two important aspects of resilience (Secades et al., 2016). Recent research has emphasized the positive contribution of resilience to adjustment in encountering difficult conditions (Theron & Theron, 2013; Werner, 2012; Yates & Grey, 2012). Resilience reduces anxiety and depression (Khadem, Motevalli Haghi, Ranjbari, & Mohammadi, 2017) and individuals with high resilience adjust more successfully to stressors than those with low resilience (Luthar, 2006).

Researchers have discussed different types of resilience, including academic, emotional, and behavioral resilience. Recently, they have paid special attention to academic resilience. According to Wang and Gordon (2012) academic resilience refers to the increasing likelihood of academic success regardless of the adversities and challenges in the environment brought about by new experiences, conditions, and traits (Wang & Gordon, 2012). Many studies have focused on educational resilience and improvements in the education of students at risk of academic dropout and failure (Rojas, 2015).

According to the current theories, resilience is as a multidimensional construction which consists constitutional variables like temperament and personality as well as special skills, such as active problem-solving that help people to cope well with life events (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, 2006). Academic resilience is affected by both external protective factors (e.g. social supports and opportunities available in the family, school, community, and peers) and internal protective factors (e.g. personality traits, skills, attitudes, beliefs, and coping strategies). Focused on internal protective factors, the present study seeks to investigate the role of coping styles and personality traits in the academic resilience.

In stressful situations, individuals use different strategies to cope with their stress (Ahn, 2014). Successful coping is intended to mediate the potentially harmful effects of experiencing unpleasant emotional states. Moreover, even in facing with the same type of stress, individuals use different coping styles that could be due to their inherent preferences rather than the causal differences in individual behaviors (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015).

In line with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) model and Endler and Parker’s (2015) classification, the present study examines problem-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance coping styles. Problem-oriented style aim to cognitively reconstruct the problem or alter the situation with efforts to solve the problem or reduce its effects by taking action. Emotion-oriented style aims to diminish stress via emotional reactions (e.g. self-blaming), self-preoccupation, and or imagining. Avoidance styles are to avoid the stressful conditions through social diverting or distraction of oneself with other conditions or tasks (Endler & Parker’s, 2015).

According to Skodol (2010), resilience and coping have mutual relationship and are interrelated; each of them alone or in combination is likely to make better or worse the effect of unfavorable experiences. Moreover, cognitive reappraisal, positive emotionality, and active coping styles are all considered as psychosocial factors related to resilience and promote efficient coping (Feder, Nestler, Westphal, & Charney, 2010). Students with inefficient coping capability, have poor cognitive flexibility, low self-control, and inability to regulate their emotions. Also, they are unable to pursue their educational goals and environmental demands, have low academic achievement, and suffer from learning problems (Piers, 2004; Haeussler, 2013). A few studies have explored the relationship between resilience and coping styles (Chen, 2016).

Dumont and Provost (1999) found that resilient people scored high on problem-oriented style. The findings of another study indicated significant relationship between emotion-oriented style and low resilience, also there was not a positive association between task-oriented coping style and resilience, but task-oriented coping acted as a mediator to make association between conscientiousness and resilience (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006). Accordingly, resilience is positively associated to task-oriented style and negatively related to emotion-oriented style (Chen, 2016).

Moreover, by understanding the people’s personality traits, it is possible to predict their behavior. Individual’s personality help them cope in unique ways in stressful situations (Son, Lee, & Kim, 2015). Much evidence indicates that personality traits impact resilience among the adolescents (Fayombo, 2010). Literature suggests that the big five personality traits, i.e. neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are five empirically-approved dimensions of personality.

It seems that resilience has a negative correlation with neuroticism as it reduces vulnerability to negative emotions and has strong relationship with depression and anxiety (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Bienvenu & Stein, 2003). In contrast, resilience has a positive association with extraversion, because extraverts tend to experience positive emotions, form close relationships to others, and seek social interactions (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Social support and positive emotions have been related to resilience (Luthar et al., 2006; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Bonanno, 2004). Additionally, resilience has a moderate relationship with conscientiousness, as conscientious people have high self-efficacy and use an efficient problem-solving style to cope with stressful situations.

Campbell-Sills et al. (2006) study supports the negative relationship between resilience and neuroticism and positive association between resilience with conscientiousness and extraversion. Also, Nakaya, Oshio, and Kaneko (2006) found negative relationship between resilience and neuroticism as well as positive correlations between resilience with the extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness traits. Similarly, they used big five personality traits to distinguish between well-adjusted and vulnerable personality profiles. Annalakshmi (2007) showed that resilience was positively associated with the well-adjusted personality profile obtained. In addition, resilient individuals are better adjusted and psychologically healthier (Friborg, Barlaug, Martinussen, Rosenvinge, & Hjemdal, 2005). The findings of Fayombo (2010) study indicate the positive relationship between the personality traits (extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and resilience. These personality traits promote resilience in a person. However, neuroticism was found to be negatively associated with psychological resilience and weakens it.

Although the relationship of coping styles and personality traits to resilience has been identified, there is still scanty research on the relationship among personality traits, coping styles and academic resilience. Thus, the present study aims to examine the relationship between personality traits and coping styles, in one hand, and academic resilience, on the other hand. In addition, it seeks to determine contribution of personality traits and coping styles to academic resilience. In fact, this study provides fundamental data to prepare students intervention strategies for enhancing academic resilience through investigating its influencing factors.

2. Methods

This research was a cross-sectional study. The study population include University of Kashan’s graduated students from February to March 2017. The sample consists of 368 (253 females and 115 males, aged: 18 to 22 years) students selected using a random multistage cluster sampling method. In the first step of sampling, four faculties of University of Kashan were randomly selected. Then, some classes were randomly selected as the final cluster, and questionnaires were distributed among the students of the classes. The inclusion criteria were being 18-22 years old (BSc. students) and consent for participation in the study.

The exclusion criterion was incomplete or distorted answers. A total of 390 questionnaires were returned. Of them, 22 were incomplete and distorted questionnaires. Finally, 368 questionnaires were used for data analysis. The study data were collected using academic resilience scale, coping inventory for stressful situation and neo personality traits inventory. Step-by-step regression analysis was used to analyze the data. It is noteworthy that the objectives of the study were fully explained to the participants, and written informed consents were obtained from those who agreed to participate in the study. To maintain anonymity, the participants’ personal information were excluded.

Academic Resilience Scale (ARS), developed by Martin, & Marsh (2003), is a 6-item self-report instrument to measure student’s resilience in dealing with challenges, obstacles, and stressful situations (Martin & Marsh, 2003). Respondents should rate themselves on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cassidy (2016) study findings demonstrated that the scale has good internal reliability and construct validity. The Cronbach α coefficient of this questionnaire has been reported 85% to 88%. The reliability and validity of this scale has been confirmed in the Iranian context by Hashemi (2011). In the present study, the Cronbach α was obtained as 0.84.

Endler and Parker (1990) designed Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation Questionnaire to evaluate individuals’ coping skills. It contains 48 self-report items on Likert-scale format ranging from 1=never to 5=extreme. They have reported the reliability coefficients of 0.90, 0.85, and 0.82 for problem-focused coping style, emotion-focused coping style, and avoidant coping style, respectively. Michaeli Manee (2010) reported its Cronbach α as 0.64 for problem-focused coping style, 0.60 for emotion-focused coping style, and 0.61 for avoidant coping style. In the present study, the reliability coefficients for problem-focused coping style, emotion-focused coping style, and avoidant coping style were calculated as 0.87, 0.82, and 0.79, respectively.

The 60-item Neo Personality Traits Inventory (NEO-FFI) was developed to provide a concise measure of the 5 basic personality traits, namely, neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreement, and conscientiousness (Costa & McCrae, 2004). In this questionnaire, the answer to each item is scored on a 5-point Likert-type format. Several studies have confirmed the reliability and validity of this scale. Costa and McCrae (1992) reported an internal consistency ranges from 0.68 to 0.86. In a study conducted by Sami et al. (2015), the overall reliability of this questionnaire was calculated as 0.83. Valikhani et al. (2017) reported the Cronbach α coefficient for each scale as: 0.82 (neuroticism), 0.79 (extroversion), 0.60 (openness to experience), 0.69 (agreement), and 0.75 (conscientiousness). In the present study, Cronbach α for neuroticism, extraversion, and openness to experience, agreement and conscientiousness were computed 0.81, 0.76, 0.79, 0.74 and 0.79, respectively.

3. Results

To investigate the relationship between coping styles and personality traits, in one hand, and academic resilience, on the other hand, the Pearson correlation coefficients were computed. In order to determine the contributions of coping styles and personality traits in predicting academic resilience, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out. The predictors in the analysis were coping styles and personality traits and the predicted variable was the academic resilience. The results of the descriptive statistics (Mean and standard deviation) for all variables and correlations are presented in Table 1. There were correlations between the academic resilience and problem-focused coping style (r=-0.21, P<0.01), emotion-focused coping style (r=0.41, P<0.01), and avoidance coping style (r=0.16, P<0.05).

Moreover, results indicate correlation between academic resilience and neuroticism (r=-0.18, P<0.05), extraversion (r=0.45, P<0.01), openness (r=0.10, not specified), agreeableness (r=0.28, P<0.01), and conscientiousness (r=0.53, P<0.01). Based on the regression analysis results (Tables 2 and 3), coping styles (emotion-focused and problem-focused styles) predicted 21% of academic resilience variance, and personality traits (conscientiousness and extraversion) predicted 32% of academic resilience variance.

4. Discussion

Resilience could be viewed as a process for adapting to adversity and stress (Eley et al., 2013). Coping styles and personality traits are internal protective factors which affect resilience (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Lazarus & Folkman 1984; Skodol, 2010). Current research shows that at-risk students, such as freshmen and students with disabilities, have higher stress and anxiety levels than their peers (Allison, 2015). Accordingly, some researchers have argued that coping styles play an important role in students’ ability for managing stress (Rahat, & Ilhan, 2016). Research on freshmen (Gardner, Krägeloh, & Henning, 2014) have showed that some coping styles are positively correlated with university adjustment. Baqutayan & Mai (2012) study indicate that students in the experimental group better coped with academic stress than those in the control group.

Also, personality is able to explain resilience (Drybye & Shanafelt, 2012). Resilience is a process that is influenced by one’s construct of personality traits (Eley et al., 2013). According to McMillan and Reed (1994), it is obligatory to understand how resilience could enhance students’ success. They stated that resilient at-risk students have “a set of personality characteristics, dispositions, and beliefs that promote their academic success despite of their backgrounds or current circumstances” (Reis, Colbert, & Hébert, 2005). There are many research studies on the relationship between coping styles and personality traits, in one hand, and resilience, on the other hand. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a paucity of research on the association between personality traits and coping styles with academic resilience. Accordingly, this study aimed to predict students’academic resilience based on their coping styles and personality traits.

The results of the present study indicated that emotion-focused and problem-focused coping styles are predictors of academic resilience. The relationship between resilience and coping styles is consistent with previous findings that resilience is negatively associated with emotion-oriented coping style (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Dumont & Provost, 1999). According to Kawata et al. (2015), high resilient people prefer not to use emotion-focused coping styles (i.e. behavioral disengagement and venting emotion), but use problem-focused coping styles (i.e. effort and active coping) to manage stressful conditions. Indeed, resilient people scored higher on problem-solving coping strategies than those scored higher on emotion-solving coping strategies.

Resilient students are more likely to be competent, self-controlled, tolerant of negative affects, and accept changes with positive attitudes (Chen, 2016). Hence, when dealing adversities, people are more likely to alter the situations and or attempt to solve the problem (problem-oriented style), rather than using self-blaming, self-preoccupation, or fantasizing (emotion-oriented style). Accordingly, resilient people tend to use problem-oriented strategies to face challenges.

Another finding of the present study indicated that conscientiousness and extraversion personality traits are predictors of academic resilience. According to this finding, the students who exhibited conscientiousness personality trait like always being prepared, getting chores done right away and paying attention to details were found to be resilient indicating that probably they are usually calm in stressful situations which strengthens their inherent ability to cope with stress (Fayombo, 2010).

This approves the previous report by Goleman (1997) that many features related with conscientiousness (e.g. organization, being thorough and planning) fall under the category of emotional intelligence which promote resilience. Conscientious people have the hard-working style that may lend itself well to task-oriented coping style, helping them to begin to act beyond stressful circumstances effectively and experience a sense of self-efficacy (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006).

Moreover, the extraverts in the present study, those who are outgoing, feeling comfortable with other individuals, and initiate conversations, also tend to be resilient. This supports the previous findings of studies that extraverts have keen interest in other individuals and external events (Ewen, 1998) and venture with confidence into the unfamiliar zone and socially adjust to circumstances (Zuckerman, 1991). The extraverts are assertive, energetic, talkative, enthusiastic, and venturing forth with confidence into the unknown (Ewen, 1998). These traits are essential for resilience (Fayombo, 2010).

Extraverts have more positive affective style and excitement, intimate interpersonal interactions, seek social activities and supports from around individuals (Tugade, Fredrickson, & Barrett, 2004). The strong association of resilience with extraversion may suggest the advantages of positive emotional style, capacity for interpersonal intimacy, and high levels of social interactions and activities. In particular, positive emotion has been found to allow people rebound subjectively and physiologically from stressful events (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). According to Fredrickson (2001), positive affects contribute to resilience because they broaden the ‘‘thought action repertoires’’ that are available to individuals under stressful circumstance. The flexibility in thinking and expanded behavioral choices as a consequence of positive emotion may increase the personal resources of extraverts under adverse conditions. Moreover, extravert people tend to build strong networks of social protection that may help them avail to this important supportive factor during times of adversity (Rutter, 1985).

McMillan and Reed (1994) discussed the need to understand how resilience promotes success in students. They describe resilient at-risk students as those with a set of personality characteristics, dispositions, and beliefs that promote their academic success regardless of their backgrounds or current circumstances. The present study has several limitations. The sample belongs to a specific group and may not represent the general population. This study is cross-sectional, which prohibits causal conclusions. Additionally, using self-reported tools may introduce bias from the participants. Thus, our findings can be generalized with caution.

With regard to methodological limitations of the current study, we suggest researchers to study students in high school. Also, it is necessary to research on at-risk students (such as freshmen, and students with disabilities). In future studies, other psychological variables influencing the academic resilience can be investigated, too. Results of this study confirm that students’ coping styles have considerable impact on their academic resilience. Furthermore, academic resilient individuals mostly have conscientious and extravert personality traits. Our study results are useful for psychologists, school counselors, and parents to understand students’ behaviors and help them achieve their academic goals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Resilience could be viewed as a process for adapting to adversity and stress (Eley et al., 2013). Coping styles and personality traits are internal protective factors which affect resilience (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Lazarus & Folkman 1984; Skodol, 2010). Current research shows that at-risk students, such as freshmen and students with disabilities, have higher stress and anxiety levels than their peers (Allison, 2015). Accordingly, some researchers have argued that coping styles play an important role in students’ ability for managing stress (Rahat, & Ilhan, 2016). Research on freshmen (Gardner, Krägeloh, & Henning, 2014) have showed that some coping styles are positively correlated with university adjustment. Baqutayan & Mai (2012) study indicate that students in the experimental group better coped with academic stress than those in the control group.

Also, personality is able to explain resilience (Drybye & Shanafelt, 2012). Resilience is a process that is influenced by one’s construct of personality traits (Eley et al., 2013). According to McMillan and Reed (1994), it is obligatory to understand how resilience could enhance students’ success. They stated that resilient at-risk students have “a set of personality characteristics, dispositions, and beliefs that promote their academic success despite of their backgrounds or current circumstances” (Reis, Colbert, & Hébert, 2005). There are many research studies on the relationship between coping styles and personality traits, in one hand, and resilience, on the other hand. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a paucity of research on the association between personality traits and coping styles with academic resilience. Accordingly, this study aimed to predict students’academic resilience based on their coping styles and personality traits.

The results of the present study indicated that emotion-focused and problem-focused coping styles are predictors of academic resilience. The relationship between resilience and coping styles is consistent with previous findings that resilience is negatively associated with emotion-oriented coping style (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Dumont & Provost, 1999). According to Kawata et al. (2015), high resilient people prefer not to use emotion-focused coping styles (i.e. behavioral disengagement and venting emotion), but use problem-focused coping styles (i.e. effort and active coping) to manage stressful conditions. Indeed, resilient people scored higher on problem-solving coping strategies than those scored higher on emotion-solving coping strategies.

Resilient students are more likely to be competent, self-controlled, tolerant of negative affects, and accept changes with positive attitudes (Chen, 2016). Hence, when dealing adversities, people are more likely to alter the situations and or attempt to solve the problem (problem-oriented style), rather than using self-blaming, self-preoccupation, or fantasizing (emotion-oriented style). Accordingly, resilient people tend to use problem-oriented strategies to face challenges.

Another finding of the present study indicated that conscientiousness and extraversion personality traits are predictors of academic resilience. According to this finding, the students who exhibited conscientiousness personality trait like always being prepared, getting chores done right away and paying attention to details were found to be resilient indicating that probably they are usually calm in stressful situations which strengthens their inherent ability to cope with stress (Fayombo, 2010).

This approves the previous report by Goleman (1997) that many features related with conscientiousness (e.g. organization, being thorough and planning) fall under the category of emotional intelligence which promote resilience. Conscientious people have the hard-working style that may lend itself well to task-oriented coping style, helping them to begin to act beyond stressful circumstances effectively and experience a sense of self-efficacy (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006).

Moreover, the extraverts in the present study, those who are outgoing, feeling comfortable with other individuals, and initiate conversations, also tend to be resilient. This supports the previous findings of studies that extraverts have keen interest in other individuals and external events (Ewen, 1998) and venture with confidence into the unfamiliar zone and socially adjust to circumstances (Zuckerman, 1991). The extraverts are assertive, energetic, talkative, enthusiastic, and venturing forth with confidence into the unknown (Ewen, 1998). These traits are essential for resilience (Fayombo, 2010).

Extraverts have more positive affective style and excitement, intimate interpersonal interactions, seek social activities and supports from around individuals (Tugade, Fredrickson, & Barrett, 2004). The strong association of resilience with extraversion may suggest the advantages of positive emotional style, capacity for interpersonal intimacy, and high levels of social interactions and activities. In particular, positive emotion has been found to allow people rebound subjectively and physiologically from stressful events (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). According to Fredrickson (2001), positive affects contribute to resilience because they broaden the ‘‘thought action repertoires’’ that are available to individuals under stressful circumstance. The flexibility in thinking and expanded behavioral choices as a consequence of positive emotion may increase the personal resources of extraverts under adverse conditions. Moreover, extravert people tend to build strong networks of social protection that may help them avail to this important supportive factor during times of adversity (Rutter, 1985).

McMillan and Reed (1994) discussed the need to understand how resilience promotes success in students. They describe resilient at-risk students as those with a set of personality characteristics, dispositions, and beliefs that promote their academic success regardless of their backgrounds or current circumstances. The present study has several limitations. The sample belongs to a specific group and may not represent the general population. This study is cross-sectional, which prohibits causal conclusions. Additionally, using self-reported tools may introduce bias from the participants. Thus, our findings can be generalized with caution.

With regard to methodological limitations of the current study, we suggest researchers to study students in high school. Also, it is necessary to research on at-risk students (such as freshmen, and students with disabilities). In future studies, other psychological variables influencing the academic resilience can be investigated, too. Results of this study confirm that students’ coping styles have considerable impact on their academic resilience. Furthermore, academic resilient individuals mostly have conscientious and extravert personality traits. Our study results are useful for psychologists, school counselors, and parents to understand students’ behaviors and help them achieve their academic goals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allison, K. D. (2015). Stress, anxiety symptomology, and the need for student support services for university freshmen of first-generation status, low-SES backgrounds, and those registered with disabilities [MSc. thesis]. Louisiana: Louisiana State University.

- Annalakshmi, N. (2007). [Resilience in relation to extraversion-introversion, psychoticism and neuroticism (Persian)]. Indian Journal of Psychometry & Education, 38(1), 51-5.

- Ahn, J. H. (2014). The relationship between academic stress of grade school gifted student and regular student, and academic burnout on coping with their stress [MSc. thesis]. Gyeonggi: Ajou University, Gyeongi-do.

- Banyard, V. L., & Cantor, E. N. (2004). Adjustment to college among trauma survivors: An exploratory study of resilience. Journal of College Student Development, 45(2), 207-21. [DOI:10.1353/csd.2004.0017]

- Baqutayan, S. M. S., & Mai, M. M. (2012). Stress, strain and coping mechanisms: an experimental study of fresh college students. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 16(1), 19-30.

- Bienvenu, O. J., & Stein, M. B. (2003). Personality and anxiety disorders: A review. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 139-51. [DOI:10.1521/pedi.17.2.139.23991] [PMID]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience. American Psychologist, 59(1), 20-8. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20] [PMID]

- Brown, T. A., Chorpita, D. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(2), 179-92. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179] [PMID]

- Bülbül, T. (2012). Dropout in higher education: Reasons and solutions. Education and Science, 37(166), 219-35.

- Campbell Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585-99. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001]

- Cassidy, S. (2016 ). The academic resilience scale (ARS-30): A new multidimensional construct measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1787. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01787]

- Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(3), 377-87. [DOI:10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5]

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory and NEO five factor inventory professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- De la Fuente, J., Cardelle-Elawar, M., Martínez-Vicente, J. M., Zapata, L., & Peralta, F. J. (2013). Gender as a determining factor in the coping strategies and resilience of university students. In R. Haumann & G. Zimmer (Eds.), Handbook of Academic Performance (pp. 205-17). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Drybye, L., & Shanafelt, T.(2012). Nurturing resiliency in medical trainees. Medical Education. 46(4), 343–8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04206.x] [PMID]

- Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343-63. [DOI:10.1023/A:1021637011732]

- Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(10), 1231-44. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20295] [PMID]

- Eley, D. S., Cloninger, C. R., Walters, L., Laurence, C., Synnott, R. & Wilkinson, D. (2013). The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: Implications for enhancing well being. PeerJ, 1, e216. [DOI:10.7717/peerj.216] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. (1990). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 844-54. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844]

- Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. A. (2015). CISS: Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations. Retrieved from https://www.mhs.com/MHS-Assessment?prodname=ciss

- Ewen, R. B. (1998). Personality: A topical approach: Theories, research, major controversies, and emerging findings. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Fayombo, G. (2010). The Relationship between personality traits and psychological resilience among the Caribbean adolescents. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 2(2), 105-16. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v2n2p105]

- Feder, A., Nestler, E. J., Westphal, M., & Charney, D. S. (2010). Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience to stress. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of Adult Resilience (pp. 35–54). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2003). A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12-23. [DOI:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124]

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745-74. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-26. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218] [PMID]

- Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 14(1), 29-42. [DOI:10.1002/mpr.15]

- García-Secades, X., Molinero, O., Ruiz, R., Salguero, A., De La Vega, R., & Márquez, S. (2014). Resilience in sport: Theoretical foundations, instruments and literature review. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 14(3):83-98. [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056]

- Gardner, T. M., Krägeloh, C. U., & Henning, M. A. (2014). Religious coping,stress, and quality of life of Muslim university students in New Zealand. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(4), 327–38. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2013.804044]

- Goleman, D. (1997). “Beyond IQ: Developing the leadership competencies of emotional intelligence”. Paper presented at: The 2nd International Competency Conference, London, England, 12 October 1997.

- González-Torres1, M. C., & Artuch-Gard, R. (2014). Resilience and coping strategy profiles at university: Contextual and demographic variables. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(3), 621-48.

- Haeussler, S. (2013). Emotional regulation and resilience in educational organisations: A case of German school teachers [PhD. dissertation]. Newcastle: Northumbria University

- Hashemi, Z. (2012). Explanative model of academic and emotional resilience [MSc. thesis]. Shiraz: Shiraz University.

- Kawata, Y., Kamimura, A., Yamada, K., Izutsu, S., Wakui, S., Mizuno, M., et al. (2015). Relationship between resilience and stress coping among Japanese university athletes. Paper presented at Proceedings 19th Triennial Congress of the IEA, Melbourne, Australia, 9-14 August 2015.

- Khadem , H., Motevalli Haghi, S. A., Ranjbari ,T., & Mohammadi, A. (2017). The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and anxiety and depression symptoms among firefighters. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology,5(2), 133-40. [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271]

- Kim, N. Y. (2011). Study on relationships among stress, social support, and life satisfaction of university students [MSc. thesis]. Seoul: Konkuk University.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

- Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In: D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 740-95). Hoboken: Wiley.

- Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. (2006). Academic resilien ce and its psychological and educational correlates: A construct validity approach. Psychology in the Schools, 43(3),267-81. [DOI:10.1002/pits.20149]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO five-factor inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 587-96. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1989). Rotation to maximize the construct validity of factors in the NEO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(1), 107-24. [DOI:10.1207/s15327906mbr2401_7] [PMID]

- McMillan, J. H., & Reed, D. F. (1994). At-risk students and resiliency: Factors contributing to academic success. The Clearing House, 67(3), 137-40.

- Michaeli Manee, F. (2010). The role of coping with stress styles between irrational beliefs and social adjustment relationship among Urmia university students. Research in Psychology Health, 3(4), 45-54.

- Munro, B. & Pooley, J. A. (2009). Differences in resilience and university adjustment between school leavers and mature entry university studentes. The Australian Community Psychologist, 21(1), 50-61.

- Nakaya, M., Oshio, A., & Kaneko, H. (2006). Correlations for Adolescent Resilience Scale with big five personality traits. Psychological Reports, 98(3), 927-30. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.98.3.927-930] [PMID]

- Panter-Brick, C., & Leckman, J. F. (2013). Editorial commentary: Resilience in child development-interconnected pathways to wellbeing. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 333-6. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12057]

- Piers, D. (2004). The effects of a cognitive behavioral and emotional resilience program on the emotional resilience, social competence and school adjustment of elementary students. Long Beach, California: California State University Long Beach.

- Reis, S. R., Colbert, R. B., & Hébert, T. P. (2005). Understanding resilience in diverse, talented students in an urban high school. Roeper Review, 27(2), 110-20. [DOI:10.1080/02783190509554299]

- Rahat, E., & Ilhan, T. (2016). Coping styles, social support, relational self- construal, and resilience in predicting students’ adjustment to university life. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(1), 187-208. [DOI:10.12738/estp.2016.1.0058]

- Reich, J. W., Zautra, A. J., & Hall, J. S. (2010). Preface. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. xi–xv). New York: Guilford Press. [DOI:10.1177/1089253210388422]

- Rojas, L. F. (2015). Factors affecting academic resilience in middle school students: A case study. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 11, 63-78.

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 598-611. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598] [PMID]

- Salami, S. O. (2011). Psychosocial predictors of adjustment among first year college of education students. US-China Education Review, 8(2), 239-48.

- Sami, A., Mohammad Nazary, A., Mohsenzadeh, F., & Taheri, M. (2015). [Explanation structural equation modeling of marital infidelity based, personality dimensions, marital satisfaction and attachment styles (Persian)]. Journal of Research Behavior Science, 13(3), 376-87.

- Secades, X. G., , Molinero, O., Salguero, A., Barquín, R. R., de la Vega, C., & Márquez, S. (2016). Relationship between resilience and coping strategies in competitive sport. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 122(1), 336-49. [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056] [PMID]

- Şimşek, H. (2013). University students' tendencies toward and reasons behind dropout. Journal of Theoretical Educational Science, 6(2), 242-71.

- Skodol, A. E. (2010). The resilient personality. In J. W. Reich, A.J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of Adult Resilience (pp.112–125). New York: Guilford Press.

- Son, H. J., Lee, K. E., & Kim, N. S. (2015). Affecting factors on academic resilience of nursing students. International Journal of u- and e-Service, Science and Technology, 8(11), 231-40. [DOI:10.14257/ijunesst.2015.8.11.23]

- Theron, L. C., & Theron, A. (2013). Positive adjustment to poverty: How family communities encourage resilience in traditional African contexts. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 391-413. [DOI:10.1177/1354067X13489318]

- Thurber, C. A., & Walton, E. A. (2012). Homesickness and adjustment in university students. Journal of American College Health, 60(5), 415-19. [DOI: 10.1080/07448481.2012.673520] [PMID]

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320-33. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Barrett, L. F. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6),1161-90. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Valikhani, A., Aflakseir, A., Hashemi, R., Fathi, M., Momeni, H., & Abbasi, Z. (2017). The relationship between personality characteristics and early maladaptive schema with suicide ideation in Iranian late adolescents. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 5(4), 271-80. [DOI: 10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271]

- Wang, M. C., Gordon, E. W. (2012). Educational resilience in innercity America: Challenges and prospects. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [DOI:10.4324/9780203052723]

- Werner, E. E. (2012). Children and war: risk, resilience, and recovery. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 553-8. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000156]

- Yates, T. M., & Grey, I. K. (2012). Adapting to aging out: profiles of risk and resilience among emancipated foster youth. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 475-92. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000107] [PMID]

- Zolkoski, S. M., & Bullock, L. M. (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2295-303. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009]

- Zuckerman, M. (1991). Psychobiology of personality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.545]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2018/07/10 | Accepted: 2018/11/25 | Published: 2019/01/1

Received: 2018/07/10 | Accepted: 2018/11/25 | Published: 2019/01/1

References

1. Allison, K. D. (2015). Stress, anxiety symptomology, and the need for student support services for university freshmen of first-generation status, low-SES backgrounds, and those registered with disabilities [MSc. thesis]. Louisiana: Louisiana State University.

2. Annalakshmi, N. (2007). [Resilience in relation to extraversion-introversion, psychoticism and neuroticism (Persian)]. Indian Journal of Psychometry & Education, 38(1), 51-5.

3. Ahn, J. H. (2014). The relationship between academic stress of grade school gifted student and regular student, and academic burnout on coping with their stress [MSc. thesis]. Gyeonggi: Ajou University, Gyeongi-do.

4. Banyard, V. L., & Cantor, E. N. (2004). Adjustment to college among trauma survivors: An exploratory study of resilience. Journal of College Student Development, 45(2), 207-21. [DOI:10.1353/csd.2004.0017] [DOI:10.1353/csd.2004.0017]

5. Baqutayan, S. M. S., & Mai, M. M. (2012). Stress, strain and coping mechanisms: an experimental study of fresh college students. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 16(1), 19-30.

6. Bienvenu, O. J., & Stein, M. B. (2003). Personality and anxiety disorders: A review. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 139-51. [DOI:10.1521/pedi.17.2.139.23991] [PMID] [DOI:10.1521/pedi.17.2.139.23991]

7. Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience. American Psychologist, 59(1), 20-8. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20]

8. Brown, T. A., Chorpita, D. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(2), 179-92. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179]

9. Bülbül, T. (2012). Dropout in higher education: Reasons and solutions. Education and Science, 37(166), 219-35.

10. Campbell Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585-99. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001]

11. Cassidy, S. (2016 ). The academic resilience scale (ARS-30): A new multidimensional construct measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1787. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01787] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01787]

12. Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(3), 377-87. [DOI:10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5] [DOI:10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5]

13. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory and NEO five factor inventory professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

14. De la Fuente, J., Cardelle-Elawar, M., Martínez-Vicente, J. M., Zapata, L., & Peralta, F. J. (2013). Gender as a determining factor in the coping strategies and resilience of university students. In R. Haumann & G. Zimmer (Eds.), Handbook of Academic Performance (pp. 205-17). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

15. Drybye, L., & Shanafelt, T.(2012). Nurturing resiliency in medical trainees. Medical Education. 46(4), 343–8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04206.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04206.x]

16. Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343-63. [DOI:10.1023/A:1021637011732] [DOI:10.1023/A:1021637011732]

17. Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(10), 1231-44. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20295] [PMID] [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20295]

18. Eley, D. S., Cloninger, C. R., Walters, L., Laurence, C., Synnott, R. & Wilkinson, D. (2013). The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: Implications for enhancing well being. PeerJ, 1, e216. [DOI:10.7717/peerj.216] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.7717/peerj.216]

19. Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. (1990). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 844-54. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844]

20. Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. A. (2015). CISS: Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations. Retrieved from https://www.mhs.com/MHS-Assessment?prodname=ciss

21. Ewen, R. B. (1998). Personality: A topical approach: Theories, research, major controversies, and emerging findings. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

22. Fayombo, G. (2010). The Relationship between personality traits and psychological resilience among the Caribbean adolescents. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 2(2), 105-16. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v2n2p105] [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v2n2p105]

23. Feder, A., Nestler, E. J., Westphal, M., & Charney, D. S. (2010). Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience to stress. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of Adult Resilience (pp. 35–54). New York: Guilford Press.

24. Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2003). A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12-23. [DOI:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124] [DOI:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124]

25. Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745-74. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456] [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456]

26. Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-26. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218]

27. Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 14(1), 29-42. [DOI:10.1002/mpr.15] [DOI:10.1002/mpr.15]

28. García-Secades, X., Molinero, O., Ruiz, R., Salguero, A., De La Vega, R., & Márquez, S. (2014). Resilience in sport: Theoretical foundations, instruments and literature review. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 14(3):83-98. [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056] [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056]

29. Gardner, T. M., Krägeloh, C. U., & Henning, M. A. (2014). Religious coping,stress, and quality of life of Muslim university students in New Zealand. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(4), 327–38. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2013.804044] [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2013.804044]

30. Goleman, D. (1997). "Beyond IQ: Developing the leadership competencies of emotional intelligence". Paper presented at: The 2nd International Competency Conference, London, England, 12 October 1997. [DOI:10.29173/iq719]

31. González-Torres1, M. C., & Artuch-Gard, R. (2014). Resilience and coping strategy profiles at university: Contextual and demographic variables. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(3), 621-48.

32. Haeussler, S. (2013). Emotional regulation and resilience in educational organisations: A case of German school teachers [PhD. dissertation]. Newcastle: Northumbria University

33. Hashemi, Z. (2012). Explanative model of academic and emotional resilience [MSc. thesis]. Shiraz: Shiraz University.

34. Kawata, Y., Kamimura, A., Yamada, K., Izutsu, S., Wakui, S., Mizuno, M., et al. (2015). Relationship between resilience and stress coping among Japanese university athletes. Paper presented at Proceedings 19th Triennial Congress of the IEA, Melbourne, Australia, 9-14 August 2015.

35. Khadem , H., Motevalli Haghi, S. A., Ranjbari ,T., & Mohammadi, A. (2017). The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and anxiety and depression symptoms among firefighters. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology,5(2), 133-40. [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271] [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271]

36. Kim, N. Y. (2011). Study on relationships among stress, social support, and life satisfaction of university students [MSc. thesis]. Seoul: Konkuk University.

37. Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

38. Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In: D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 740-95). Hoboken: Wiley.

39. Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. (2006). Academic resilien ce and its psychological and educational correlates: A construct validity approach. Psychology in the Schools, 43(3),267-81. [DOI:10.1002/pits.20149] [DOI:10.1002/pits.20149]

40. McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO five-factor inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 587-96. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1] [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1]

41. McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1989). Rotation to maximize the construct validity of factors in the NEO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(1), 107-24. [DOI:10.1207/s15327906mbr2401_7] [PMID] [DOI:10.1207/s15327906mbr2401_7]

42. McMillan, J. H., & Reed, D. F. (1994). At-risk students and resiliency: Factors contributing to academic success. The Clearing House, 67(3), 137-40. [DOI:10.1080/00098655.1994.9956043]

43. Michaeli Manee, F. (2010). The role of coping with stress styles between irrational beliefs and social adjustment relationship among Urmia university students. Research in Psychology Health, 3(4), 45-54.

44. Munro, B. & Pooley, J. A. (2009). Differences in resilience and university adjustment between school leavers and mature entry university studentes. The Australian Community Psychologist, 21(1), 50-61.

45. Nakaya, M., Oshio, A., & Kaneko, H. (2006). Correlations for Adolescent Resilience Scale with big five personality traits. Psychological Reports, 98(3), 927-30. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.98.3.927-930] [PMID] [DOI:10.2466/pr0.98.3.927-930]

46. Panter-Brick, C., & Leckman, J. F. (2013). Editorial commentary: Resilience in child development-interconnected pathways to wellbeing. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 333-6. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12057] [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12057]

47. Piers, D. (2004). The effects of a cognitive behavioral and emotional resilience program on the emotional resilience, social competence and school adjustment of elementary students. Long Beach, California: California State University Long Beach.

48. Reis, S. R., Colbert, R. B., & Hébert, T. P. (2005). Understanding resilience in diverse, talented students in an urban high school. Roeper Review, 27(2), 110-20. [DOI:10.1080/02783190509554299] [DOI:10.1080/02783190509554299]

49. Rahat, E., & Ilhan, T. (2016). Coping styles, social support, relational self- construal, and resilience in predicting students' adjustment to university life. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(1), 187-208. [DOI:10.12738/estp.2016.1.0058] [DOI:10.12738/estp.2016.1.0058]

50. Reich, J. W., Zautra, A. J., & Hall, J. S. (2010). Preface. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. xi–xv). New York: Guilford Press. [DOI:10.1177/1089253210388422] [DOI:10.1177/1089253210388422]

51. Rojas, L. F. (2015). Factors affecting academic resilience in middle school students: A case study. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 11, 63-78. [DOI:10.26817/16925777.286]

52. Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 598-611. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598] [PMID] [DOI:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598]

53. Salami, S. O. (2011). Psychosocial predictors of adjustment among first year college of education students. US-China Education Review, 8(2), 239-48.

54. Sami, A., Mohammad Nazary, A., Mohsenzadeh, F., & Taheri, M. (2015). [Explanation structural equation modeling of marital infidelity based, personality dimensions, marital satisfaction and attachment styles (Persian)]. Journal of Research Behavior Science, 13(3), 376-87.

55. Secades, X. G., , Molinero, O., Salguero, A., Barquín, R. R., de la Vega, C., & Márquez, S. (2016). Relationship between resilience and coping strategies in competitive sport. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 122(1), 336-49. [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/0031512516631056]

56. Şimşek, H. (2013). University students' tendencies toward and reasons behind dropout. Journal of Theoretical Educational Science, 6(2), 242-71.

57. Skodol, A. E. (2010). The resilient personality. In J. W. Reich, A.J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of Adult Resilience (pp.112–125). New York: Guilford Press.

58. Son, H. J., Lee, K. E., & Kim, N. S. (2015). Affecting factors on academic resilience of nursing students. International Journal of u- and e-Service, Science and Technology, 8(11), 231-40. [DOI:10.14257/ijunesst.2015.8.11.23] [DOI:10.14257/ijunesst.2015.8.11.23]

59. Theron, L. C., & Theron, A. (2013). Positive adjustment to poverty: How family communities encourage resilience in traditional African contexts. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 391-413. [DOI:10.1177/1354067X13489318] [DOI:10.1177/1354067X13489318]

60. Thurber, C. A., & Walton, E. A. (2012). Homesickness and adjustment in university students. Journal of American College Health, 60(5), 415-19. [DOI: 10.1080/07448481.2012.673520] [PMID] [DOI:10.1080/07448481.2012.673520]

61. Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320-33. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320]

62. Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Barrett, L. F. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6),1161-90. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x]

63. Valikhani, A., Aflakseir, A., Hashemi, R., Fathi, M., Momeni, H., & Abbasi, Z. (2017). The relationship between personality characteristics and early maladaptive schema with suicide ideation in Iranian late adolescents. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 5(4), 271-80. [DOI: 10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271] [DOI:10.29252/nirp.jpcp.5.4.271]

64. Wang, M. C., Gordon, E. W. (2012). Educational resilience in innercity America: Challenges and prospects. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [DOI:10.4324/9780203052723] [DOI:10.4324/9780203052723]

65. Werner, E. E. (2012). Children and war: risk, resilience, and recovery. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 553-8. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000156] [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000156]

66. Yates, T. M., & Grey, I. K. (2012). Adapting to aging out: profiles of risk and resilience among emancipated foster youth. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 475-92. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000107] [PMID] [DOI:10.1017/S0954579412000107]

67. Zolkoski, S. M., & Bullock, L. M. (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2295-303. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009] [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009]

68. Zuckerman, M. (1991). Psychobiology of personality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.545] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.545]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |