Volume 6, Issue 3 (Summer 2018)

PCP 2018, 6(3): 191-196 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ahadi B, Lotfi M, Moradi F. Relationship Between Positive and Negative Affect and Depression: The Mediating Role of Rumination. PCP 2018; 6 (3) :191-196

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-557-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-557-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences & Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran. , b.ahadi@alzahra.ac.ir

2- Assistant Professor, Departmen of Mental Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry) Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences & Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Departmen of Mental Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry) Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences & Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 622 kb]

(3920 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8660 Views)

Full-Text: (3842 Views)

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most common health issues, currently affecting students. This disorder harms an individual’s public, and professional performance (Ibrahim, Kelly, Adams, & Glazebrook, 2013). Depression is often a continuing and repetitive pattern that seriously impairs the quality of life of the patients and even their families, and causes high levels of practical defect (Nutt et al., 2007).

The essential features of depressive disorders are a persistent low mood and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities (Allan et al., 2018). Rumination lengthens the pessimistic attitude by increasing the severity and ratio of remembering negative events. Rumination by focusing on the ideals that the self has not accomplished may lead to negative affect. Focusing on positive achievements is not related to negative affect states, such as depressive disorders (Broderick & Korteland, 2004). Depressive rumination is frequent attention to negative attitude about one’s self and is strongly associated to depressive disorders. A considerable number of researches have shown that rumination preserves negative affect, anticipates depressive periods and eventuates the chronic depressive periods (Vergara-Lopez, Lopez-Vergara & Roberts, 2016).

Depression has long been characterized by high negative affect and low positive affect, with persistent sad mood and decreased experiences of pleasure being key characteristics of the disorder (Cohen, et al., 2017). Patients with major depression, commonly show symptoms of depression associated with ‘decreased positive affect’ (Clark & Watson, 1991). Reduction in the ability to experience positive affect (i.e., lack of energy, loss of interest) is a hallmark of depression. Positive affect and negative affect are two contrary aspects; high negative affect is characterized by personal grief and distasteful occupations while positive affect displays subjective enjoyable occupations. Depressed individuals generally exhibit symptoms of apathy, and lack of impetus, which are the fundamental symptoms of depressive disorders related with ‘reduced positive affect.’ These symptoms are constantly related with depressive disorder (Crawford & Henry, 2004).

One outstanding model in depression is the Response Styles Theory presented by Nolen Hoeksema and Morrow (1991), which proposes that how individuals answer to their negative affect, impresses the period and intensity of depression. According to this model, rumination is a self-focused behavior and thought about depressive symptoms without any effort to reduce the negative affect or the basic troubles. Rumination on negative affect triggers and continues the cognitive patterns of depression. In other words, in situations of sorrow, individuals who brainstorm about the related content and sources have more continuous negative affects and exhibit negative cognition about themselves and their lives (Johnson, McKenzie, & McMurrich, 2008).

The strategies people use to respond to negative state of mood contributes to the onset and maintenance of depressive rumination (behaviors and thoughts that focus one’s attention on their depressive symptoms and on the implications of those symptoms). Rumination in response to pessimistic thoughts has been shown to anticipate the continuation of depressive symptoms. Depression is related to both an increase in negative affect and a decrease in positive affect. Various researches have shown that depression is accompanied by a tendency to not favor positive motives. Depressed people have a tendency to ignore positive affect and issues (Feldman, Joormann & Johnson, 2008).

Depression characterized by abnormalities in cognitive processes such as negative cognitive biases, increases negative cognition, and creates difficulties in emotion regulation. Previous studies have shown that the correlation between depression symptoms and diminished positive affect supports depression-specific effect. Also, studies have shown that lack of positivity and negative cognitions are specifically found in patients diagnosed with depression and are associated with rumination (Blanco & Joormann, 2017). Vesal & Nazarinya (2016) found that rumination significantly predicted the quality of sleep and depressive symptoms. Moulds et al. (2007) in their study showed that there is a positive relationship between rumination and depression.

Prior investigations had focused on the direct relationship between positive and negative affect with depression, and also on the direct relationship between rumination and depression, but the mediating role of rumination in the relationship between positive and negative affect and depression has been ignored. By recognizing the mediating role of rumination in the relation between positive and negative affect and depression, it is possible to determine how positive and negative affect influence depression, so that therapeutic interventions can reduce rumination and help in treating depression.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to understand the mediating role of rumination between positive and negative affect and depression among students by examining several hypotheses between the variables and depression. First, a negative relationship can be observed between positive affect and depression. Second, there is a positive relationship between negative affect and depression. Third, there is a positive relationship between rumination and depression. Finally, it was concluded that rumination mediates the relationship between positive and negative affect and depression among students.

2. Methods

The current research was a cross-sectional study. The study population comprised all students of Alzahra University in Tehran, in the 2017-2018 educational year, selected by convenience sampling method. The researcher was referred to the classes before the beginning of the lectures, distributed the questionnaires to the students and provided the necessary explanations. The students were assured that their responses would remain confidential. Questionnaires were distributed among those who were willing to participate in the study; thus, the students participated with informed consent. The inclusion criteria required the participants to be above 18 years of age and that they should not be under any psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. The exclusion criteria were as follows: consumption of specific drugs and presenting invalid, incomplete information. 263 students completed the questionnaires, and 249 questionnaires were found to be valid. This research encompassed students with bachelor (210) and master degrees (39).

Follwoing measures were used in this study: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II); which has 21 items assessing the cognitive, affective, and somatic symptoms of depression. The items are answered on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0=never to 3=always). Higher scores indicate greater depression levels. Considerable evidences attest to the internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Allan et al., 2018). A large body of research supports the notion that the BDI-II is a psychometrically sound instrument with internal consistency rate of 0.9 and the retest reliability ranging from 0.73 to 0.96 (Wang & Gorensteein, 2013). The Persian version of BDI-II has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.87) and acceptable test-retest reliability (r=0.74) (Ghassemzadeh, Mojtabai, Karamghadiri & Ebrahimkhani, 2005). The current sample also demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.90).

Second measure is Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).This scale contains 20 items and assesses the trait rates of positive and negative affect. It measures 10 positive and 10 negative emotion dispositions. Individuals rated their positive and negative affect on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1=can not describe me 5=to exactly can describe me. Watson, Clark, & Tellegen (1988) demonstrated that positive and negative affect components have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.85), and also powerful convergent validity (Cohen et al., 2017). Research on the psychometric properties of the Persian version of this scale (Bakhshipour & Dezhkam, 2006) provides same evidence with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.85). This scale in the current sample was also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.75).

The third instrument was the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS); (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). This questionnaire has 22 statements and rates rumination on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (infrequently) to 4 (frequently). Respondents reveal the amount of ruminative thoughts in negative situations. A good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.89) has been reported for this scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) (Vergara-Lopez, Lopez-Vergara & Roberts 2016). The Persian version has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.90) (Aghayosefi, Kharbu., Hatami, 2015). This scale, in the current sample, also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.93).

The completion of questionnaires was followed by data collection and correlation, followed by mediation analysis to analyze the data. The normal theory method was employed for testing the mediation, and R 3.4.2 software was used for bootstrapping using the mediation package and the Sobel test using the multilevel package.

3. Results

The data collected from the questionnaires were analyzed. The sample size constituted 249 students: 84.34% were undergraduate students, 15.66% postgraduate students; 59.44% dormitory students, 40.56% non-dormitory students. An inspection of skewness and kurtosis and histogram showed that all the variables were normal. Additionally, the Tolerance Index was lower than 1 (ranging from 0.63 to 0.86), and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was neither higher than 10 nor lower than 1 (ranging from 1.45 to 1.61), supporting the absence of multicollinearity between the variables. The Durbin-Watson test showed the absence of auto-correlation. The values of Durbin-Watson test were as follows- positive affect (1.99), negative affect (2.03), and rumination (2.19). The homoscedasticity and normality of residuals were confirmed using an inspection of residual Q-Q plots. Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of each variable including depression, positive affect, negative affect and rumination.

Depression is one of the most common health issues, currently affecting students. This disorder harms an individual’s public, and professional performance (Ibrahim, Kelly, Adams, & Glazebrook, 2013). Depression is often a continuing and repetitive pattern that seriously impairs the quality of life of the patients and even their families, and causes high levels of practical defect (Nutt et al., 2007).

The essential features of depressive disorders are a persistent low mood and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities (Allan et al., 2018). Rumination lengthens the pessimistic attitude by increasing the severity and ratio of remembering negative events. Rumination by focusing on the ideals that the self has not accomplished may lead to negative affect. Focusing on positive achievements is not related to negative affect states, such as depressive disorders (Broderick & Korteland, 2004). Depressive rumination is frequent attention to negative attitude about one’s self and is strongly associated to depressive disorders. A considerable number of researches have shown that rumination preserves negative affect, anticipates depressive periods and eventuates the chronic depressive periods (Vergara-Lopez, Lopez-Vergara & Roberts, 2016).

Depression has long been characterized by high negative affect and low positive affect, with persistent sad mood and decreased experiences of pleasure being key characteristics of the disorder (Cohen, et al., 2017). Patients with major depression, commonly show symptoms of depression associated with ‘decreased positive affect’ (Clark & Watson, 1991). Reduction in the ability to experience positive affect (i.e., lack of energy, loss of interest) is a hallmark of depression. Positive affect and negative affect are two contrary aspects; high negative affect is characterized by personal grief and distasteful occupations while positive affect displays subjective enjoyable occupations. Depressed individuals generally exhibit symptoms of apathy, and lack of impetus, which are the fundamental symptoms of depressive disorders related with ‘reduced positive affect.’ These symptoms are constantly related with depressive disorder (Crawford & Henry, 2004).

One outstanding model in depression is the Response Styles Theory presented by Nolen Hoeksema and Morrow (1991), which proposes that how individuals answer to their negative affect, impresses the period and intensity of depression. According to this model, rumination is a self-focused behavior and thought about depressive symptoms without any effort to reduce the negative affect or the basic troubles. Rumination on negative affect triggers and continues the cognitive patterns of depression. In other words, in situations of sorrow, individuals who brainstorm about the related content and sources have more continuous negative affects and exhibit negative cognition about themselves and their lives (Johnson, McKenzie, & McMurrich, 2008).

The strategies people use to respond to negative state of mood contributes to the onset and maintenance of depressive rumination (behaviors and thoughts that focus one’s attention on their depressive symptoms and on the implications of those symptoms). Rumination in response to pessimistic thoughts has been shown to anticipate the continuation of depressive symptoms. Depression is related to both an increase in negative affect and a decrease in positive affect. Various researches have shown that depression is accompanied by a tendency to not favor positive motives. Depressed people have a tendency to ignore positive affect and issues (Feldman, Joormann & Johnson, 2008).

Depression characterized by abnormalities in cognitive processes such as negative cognitive biases, increases negative cognition, and creates difficulties in emotion regulation. Previous studies have shown that the correlation between depression symptoms and diminished positive affect supports depression-specific effect. Also, studies have shown that lack of positivity and negative cognitions are specifically found in patients diagnosed with depression and are associated with rumination (Blanco & Joormann, 2017). Vesal & Nazarinya (2016) found that rumination significantly predicted the quality of sleep and depressive symptoms. Moulds et al. (2007) in their study showed that there is a positive relationship between rumination and depression.

Prior investigations had focused on the direct relationship between positive and negative affect with depression, and also on the direct relationship between rumination and depression, but the mediating role of rumination in the relationship between positive and negative affect and depression has been ignored. By recognizing the mediating role of rumination in the relation between positive and negative affect and depression, it is possible to determine how positive and negative affect influence depression, so that therapeutic interventions can reduce rumination and help in treating depression.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to understand the mediating role of rumination between positive and negative affect and depression among students by examining several hypotheses between the variables and depression. First, a negative relationship can be observed between positive affect and depression. Second, there is a positive relationship between negative affect and depression. Third, there is a positive relationship between rumination and depression. Finally, it was concluded that rumination mediates the relationship between positive and negative affect and depression among students.

2. Methods

The current research was a cross-sectional study. The study population comprised all students of Alzahra University in Tehran, in the 2017-2018 educational year, selected by convenience sampling method. The researcher was referred to the classes before the beginning of the lectures, distributed the questionnaires to the students and provided the necessary explanations. The students were assured that their responses would remain confidential. Questionnaires were distributed among those who were willing to participate in the study; thus, the students participated with informed consent. The inclusion criteria required the participants to be above 18 years of age and that they should not be under any psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. The exclusion criteria were as follows: consumption of specific drugs and presenting invalid, incomplete information. 263 students completed the questionnaires, and 249 questionnaires were found to be valid. This research encompassed students with bachelor (210) and master degrees (39).

Follwoing measures were used in this study: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II); which has 21 items assessing the cognitive, affective, and somatic symptoms of depression. The items are answered on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0=never to 3=always). Higher scores indicate greater depression levels. Considerable evidences attest to the internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Allan et al., 2018). A large body of research supports the notion that the BDI-II is a psychometrically sound instrument with internal consistency rate of 0.9 and the retest reliability ranging from 0.73 to 0.96 (Wang & Gorensteein, 2013). The Persian version of BDI-II has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.87) and acceptable test-retest reliability (r=0.74) (Ghassemzadeh, Mojtabai, Karamghadiri & Ebrahimkhani, 2005). The current sample also demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.90).

Second measure is Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).This scale contains 20 items and assesses the trait rates of positive and negative affect. It measures 10 positive and 10 negative emotion dispositions. Individuals rated their positive and negative affect on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1=can not describe me 5=to exactly can describe me. Watson, Clark, & Tellegen (1988) demonstrated that positive and negative affect components have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.85), and also powerful convergent validity (Cohen et al., 2017). Research on the psychometric properties of the Persian version of this scale (Bakhshipour & Dezhkam, 2006) provides same evidence with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.85). This scale in the current sample was also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.75).

The third instrument was the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS); (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). This questionnaire has 22 statements and rates rumination on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (infrequently) to 4 (frequently). Respondents reveal the amount of ruminative thoughts in negative situations. A good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.89) has been reported for this scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) (Vergara-Lopez, Lopez-Vergara & Roberts 2016). The Persian version has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.90) (Aghayosefi, Kharbu., Hatami, 2015). This scale, in the current sample, also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.93).

The completion of questionnaires was followed by data collection and correlation, followed by mediation analysis to analyze the data. The normal theory method was employed for testing the mediation, and R 3.4.2 software was used for bootstrapping using the mediation package and the Sobel test using the multilevel package.

3. Results

The data collected from the questionnaires were analyzed. The sample size constituted 249 students: 84.34% were undergraduate students, 15.66% postgraduate students; 59.44% dormitory students, 40.56% non-dormitory students. An inspection of skewness and kurtosis and histogram showed that all the variables were normal. Additionally, the Tolerance Index was lower than 1 (ranging from 0.63 to 0.86), and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was neither higher than 10 nor lower than 1 (ranging from 1.45 to 1.61), supporting the absence of multicollinearity between the variables. The Durbin-Watson test showed the absence of auto-correlation. The values of Durbin-Watson test were as follows- positive affect (1.99), negative affect (2.03), and rumination (2.19). The homoscedasticity and normality of residuals were confirmed using an inspection of residual Q-Q plots. Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of each variable including depression, positive affect, negative affect and rumination.

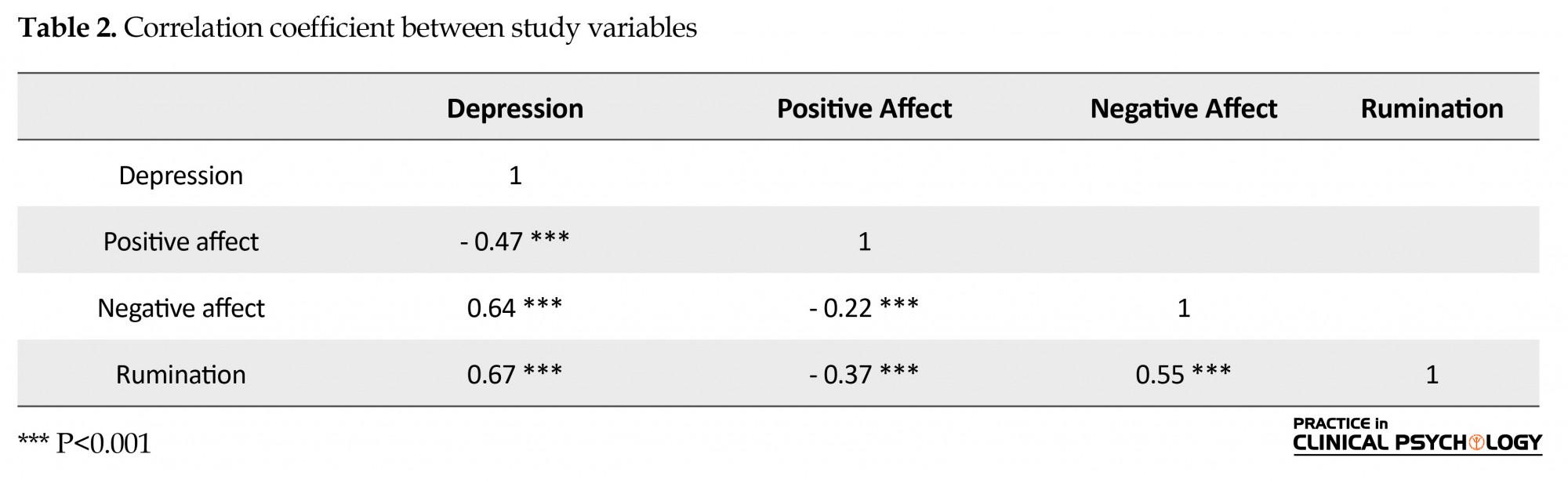

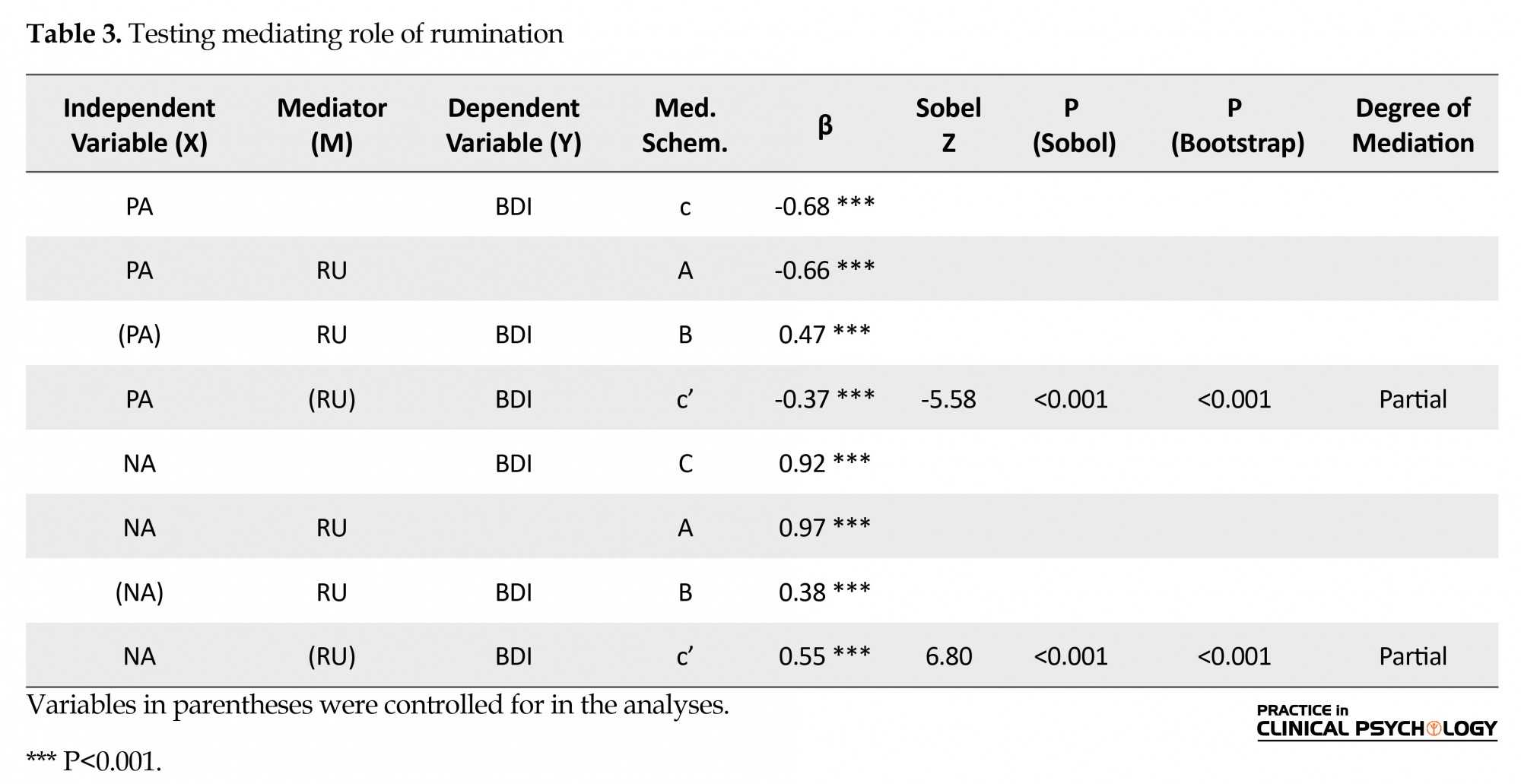

The aim of this study was to study the relation between positive and negative affect, rumination and depression. Table 2 shows the matrix of the correlation between the variables. As revealed, positive affect has a meaningful and negative relationship with rumination and depression. The result also showed that in negative affect, rumination and depression have a meaningful and positive relation with one another. Another aim was to study the mediating role of rumination in the relation between positive and negative affect and depression. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to determine the portion of positive and negative affect in explaining the variance of depression and the mediating role of rumination. Sobel test and bootstrapping method were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the mediation effect. Results are summarized in Table 3.

The results of the analysis confirm the hypothesis that rumination mediates the relationship between positive and negative affect and depression among students. According to Table 3, ‘c’ coefficient is significant, and the effect of predictor variable is less than ‘c’ coefficient; therefore, rumination is a partial mediator in the relationship between positive affect and depression. Similarly, the effect of negative affect decreased in the presence of rumination but not eliminated. So rumination is a partial mediator in the relationship between negative affect and depression.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that positive and negative affect and rumination are significantly correlated with depression. The empirical findings indicated that rumination plays a mediating role between positive and negative affect and depression. In other words, positive and negative affect influenced depression through rumination. The results showed that positive and negative affect predict depression both directly and indirectly, in accordance with the findings of Blanco and Joormann (2017) who showed positive and negative affect are related to depression. By finding a relation between rumination and depression, our result has confirmed the results of previous studies (Vesal & Nazarinya, 2016; Rood et al., 2009; Rajabi, Gashtil, & Amanallahi, 2016) where a direct relation between rumination and depression were shown.

In recent years, new theories have emphasized that the previous mood influences the thoughts, beliefs and attitudes. In these approaches, negative mood led to rumination (Yousefi, Bahrami & Mehrabi, 2008). Our results are consistent with Beck’s cognitive theory of depression and response styled theory’s extension of Beck’s theory of rumination in response to negative events (Nolen Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). Two proposed mechanisms of transmission of affective vulnerabilities to depression are the cognitive responses of brooding and rumination. Trait affective vulnerabilities have been shown to predict depressive symptoms through ruminative cognitive responses to positive and negative life events. Trait negative affect predicts higher levels of rumination on negative context and greater depressive symptoms.

The affective vulnerability of high negative affect may predict depressive symptoms by exacerbating the impact of stressors on subsequent negative mood through cognitive responses such as ruminating in response to stressful events, which, over time can lead to depressive symptoms (Harding, 2016).The conclusion can be interpreted in this way: when people experience positive affect, probably they don’t engage in negative emotions and thoughts. Hence they are less likely to experience negative psychological outcomes such as depression.

When individuals experience negative affect in response to problems, they engage in rumination and think repetitively and passively about the negative affect. Also, when individuals engage in rumination, they might have experienced depression. Rumination is related to negative thoughts that may lead to depression. Indeed, cognitive process of rumination is a centralized emotional aspect of events and encompasses negative aspect of the past and present. Rumination, probably evokes negative affect and thoughts, leading to depression.

In fact, those individuals who have more negative affect and less positive affect are most at risk of thinking about negative events and experiencing rumination. These individuals probably experience depression. However, the study has several limitations, requiring future research. Our study is limited by the reliance on self-report questionnaires. Further studies should utilize clinical interviews. Also, all participants in the study were female. So, further research is needed to investigate the mediating role of rumination in the relation between positive and negative affect and depression in male.

In overall results of this study showed that positive affect could decrease the detrimental influence of rumination in the development of depression among students. Also, results showed that negative affect could increase the depression by provoking rumination. In other words, high negative affect and low positive affect through rumination could act as a buffering factor and promote predictive validity when it is used to study depression. Since this research is a correlational study, any conclusion about causality cannot be inferred from the findings, so it is necessary to examine the effect of independent on dependent variable in an experimental study. Future studies by using therapeutic interventions could explore the effect of positive affect and negative affect by the mediating role of rumination in decreasing depression. Since the individuals in this study include Iranian university students, this might prevent generalization of present findings to other cultures and countries. In order to generalize the findings of this study, conducting of same research in other countries is recommended.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants gave written consents.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to all the study participants and those who helped in conducting this research.

References

In this study, we have demonstrated that positive and negative affect and rumination are significantly correlated with depression. The empirical findings indicated that rumination plays a mediating role between positive and negative affect and depression. In other words, positive and negative affect influenced depression through rumination. The results showed that positive and negative affect predict depression both directly and indirectly, in accordance with the findings of Blanco and Joormann (2017) who showed positive and negative affect are related to depression. By finding a relation between rumination and depression, our result has confirmed the results of previous studies (Vesal & Nazarinya, 2016; Rood et al., 2009; Rajabi, Gashtil, & Amanallahi, 2016) where a direct relation between rumination and depression were shown.

In recent years, new theories have emphasized that the previous mood influences the thoughts, beliefs and attitudes. In these approaches, negative mood led to rumination (Yousefi, Bahrami & Mehrabi, 2008). Our results are consistent with Beck’s cognitive theory of depression and response styled theory’s extension of Beck’s theory of rumination in response to negative events (Nolen Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). Two proposed mechanisms of transmission of affective vulnerabilities to depression are the cognitive responses of brooding and rumination. Trait affective vulnerabilities have been shown to predict depressive symptoms through ruminative cognitive responses to positive and negative life events. Trait negative affect predicts higher levels of rumination on negative context and greater depressive symptoms.

The affective vulnerability of high negative affect may predict depressive symptoms by exacerbating the impact of stressors on subsequent negative mood through cognitive responses such as ruminating in response to stressful events, which, over time can lead to depressive symptoms (Harding, 2016).The conclusion can be interpreted in this way: when people experience positive affect, probably they don’t engage in negative emotions and thoughts. Hence they are less likely to experience negative psychological outcomes such as depression.

When individuals experience negative affect in response to problems, they engage in rumination and think repetitively and passively about the negative affect. Also, when individuals engage in rumination, they might have experienced depression. Rumination is related to negative thoughts that may lead to depression. Indeed, cognitive process of rumination is a centralized emotional aspect of events and encompasses negative aspect of the past and present. Rumination, probably evokes negative affect and thoughts, leading to depression.

In fact, those individuals who have more negative affect and less positive affect are most at risk of thinking about negative events and experiencing rumination. These individuals probably experience depression. However, the study has several limitations, requiring future research. Our study is limited by the reliance on self-report questionnaires. Further studies should utilize clinical interviews. Also, all participants in the study were female. So, further research is needed to investigate the mediating role of rumination in the relation between positive and negative affect and depression in male.

In overall results of this study showed that positive affect could decrease the detrimental influence of rumination in the development of depression among students. Also, results showed that negative affect could increase the depression by provoking rumination. In other words, high negative affect and low positive affect through rumination could act as a buffering factor and promote predictive validity when it is used to study depression. Since this research is a correlational study, any conclusion about causality cannot be inferred from the findings, so it is necessary to examine the effect of independent on dependent variable in an experimental study. Future studies by using therapeutic interventions could explore the effect of positive affect and negative affect by the mediating role of rumination in decreasing depression. Since the individuals in this study include Iranian university students, this might prevent generalization of present findings to other cultures and countries. In order to generalize the findings of this study, conducting of same research in other countries is recommended.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants gave written consents.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to all the study participants and those who helped in conducting this research.

References

- Aghayosefi, A., Kharbu, A., & Hatami, H. R. (2015). The role of rumination on psychological well-being and anxiety the spouses’ cancer patients. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(14), 79-97.

- Allan, N. P., Cooper, D., Oglesby, M. E., Short, N. A., Saulnier, K. G., & Schmidt, N. B. (2018). Lower-order anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty dimensions operate as specific vulnerabilities for social anxiety and depression within a hierarchical model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 53, 91-99. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.002] [PMID]

- Ataie, S., Fata, L., & Abhari, A. A. (2014). [Rumination and cognitive behavioral avoidance in unipolar mood disorder and social anxiety disorder: Comparison between dimensional and categorical approaches (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 283-95.

- Bakhshipour, R., & Dezhkam, M. (2006). A confirmatory factor analysis of the positive affect and negative affect scales (PANAS). Journal of Psychology, 9(36):351-65.

- Blanco, I., & Joormann, J. (2017). Examining facets of depression and social anxiety: the relation among lack of positive affect, negative cognitions, and emotion dysregulation. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20, e51. [DOI:10.1017/sjp.2017.43]

- Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2004). A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(3), 383-94. [DOI:10.1177/1359104504043920]

- Clark L A, Watson D. (1991). Tripartate model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–36. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316] [PMID]

- Cohen, J. N., Dryman, M. T., Morrison, A. S., Gilbert, K. E., Heimberg, R. G., & Gruber, J. (2017). Positive and negative affect as links between social anxiety and depression: Predicting concurrent and prospective mood symptoms in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 820-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.003] [PMID]

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 245-65. [DOI:10.1348/0144665031752934] [PMID]

- Feldman G. C., Joormann J. & Johnson S. L., (2008). Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy Researches, 32(4), 507-25. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ghassemzadeh, H., Mojtabai, R., Karamghadiri, N., & Ebrahimkhani, N. (2005). Psychometric properties of a Persianlanguage version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-I-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety, 21(4), 185-92. [DOI:10.1002/da.20070] [PMID]

- Harding, K. (2016). Integrating cognitive mechanisms in the relationship between trait affect and depressive symptoms: The role of affect amplification (PhD dissertation). Seattle, Washington: Seattle Pacific University.

- Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391-400. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015] [PMID]

- Johnson S. L., McKenzie G., McMurrich S. (2008). Among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy Researches, 32(5), 702-713. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moulds M. L., Kandris, E., Starr, S., & Wong, A. C. (2007). The relationship between rumination, avoidance and depression in a non-clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 251-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.003] [PMID]

- Nolen Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115-21. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115] [PMID]

- Nutt, D., Demyttenaere, K., Janka, Z., Aarre, T., Bourin, M., Canonico, P. L., et al. (2007). The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: The role of catecholamines in causation and cure. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 21(5), 461–71. [DOI:10.1177/0269881106069938] [PMID]

- Rajabi, G., Gashtil, K., & Amanallahi, A. (2016). The relationship between self-compassion and depression with mediating's thought rumination and worry in female nurses. Iran Journal of Nursing, 29(99), 10-21.

- Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., Nolen Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001] [PMID]

- Vergara-Lopez, C., Lopez-Vergara, H. I., & Roberts, J. E. (2016). Testing a “content meets process” model of depression vulnerability and rumination: Exploring the moderating role of set-shifting deficits. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 50, 201-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.08.002] [PMID]

- Vesal, M., Nazarinya, M. A. (2016). [Prediction of depression and sleep quality based on thought rumination and its components (inhibition and reflection) in patients with Rheumatoid arthritis (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 9(41), 47-56.

- Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A Comprehensive Review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35(4), 416–31. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048] [PMID]

- Yousefi, Z., Bahrami, F., & Mehrabi, H. A. (2008). Rumination: beginning and continuous of depression. Journal of Behavorial Sciences, 2(1), 67-73.

- Zarei, M. (2017). [Mediating role of cognitive flexibility, shame, emotion dysregulation in the relationship between neurotism and depression in students in Tehran City (Persian) (Master thesis)]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation sciences.

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2018/02/26 | Accepted: 2018/05/21 | Published: 2018/07/1

Received: 2018/02/26 | Accepted: 2018/05/21 | Published: 2018/07/1

References

1. Aghayosefi, A., Kharbu, A., & Hatami, H. R. (2015). The role of rumination on psychological well-being and anxiety the spouses' cancer patients. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(14), 79-97.

2. Allan, N. P., Cooper, D., Oglesby, M. E., Short, N. A., Saulnier, K. G., & Schmidt, N. B. (2018). Lower-order anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty dimensions operate as specific vulnerabilities for social anxiety and depression within a hierarchical model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 53, 91-99. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.002] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.002]

3. Ataie, S., Fata, L., & Abhari, A. A. (2014). [Rumination and cognitive behavioral avoidance in unipolar mood disorder and social anxiety disorder: Comparison between dimensional and categorical approaches (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 283-95.

4. Bakhshipour, R., & Dezhkam, M. (2006). A confirmatory factor analysis of the positive affect and negative affect scales (PANAS). Journal of Psychology, 9(36):351-65.

5. Blanco, I., & Joormann, J. (2017). Examining facets of depression and social anxiety: the relation among lack of positive affect, negative cognitions, and emotion dysregulation. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20, e51. [DOI:10.1017/sjp.2017.43] [DOI:10.1017/sjp.2017.43]

6. Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2004). A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(3), 383-94. [DOI:10.1177/1359104504043920] [DOI:10.1177/1359104504043920]

7. Clark L A, Watson D. (1991). Tripartate model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–36. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316]

8. Cohen, J. N., Dryman, M. T., Morrison, A. S., Gilbert, K. E., Heimberg, R. G., & Gruber, J. (2017). Positive and negative affect as links between social anxiety and depression: Predicting concurrent and prospective mood symptoms in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 820-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.003] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.003]

9. Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 245-65. [DOI:10.1348/0144665031752934] [PMID] [DOI:10.1348/0144665031752934]

10. Feldman G. C., Joormann J. & Johnson S. L., (2008). Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy Researches, 32(4), 507-25. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0]

11. Ghassemzadeh, H., Mojtabai, R., Karamghadiri, N., & Ebrahimkhani, N. (2005). Psychometric properties of a Persianlanguage version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-I-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety, 21(4), 185-92. [DOI:10.1002/da.20070] [PMID] [DOI:10.1002/da.20070]

12. Harding, K. (2016). Integrating cognitive mechanisms in the relationship between trait affect and depressive symptoms: The role of affect amplification (PhD dissertation). Seattle, Washington: Seattle Pacific University.

13. Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391-400. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015]

14. Johnson S. L., McKenzie G., McMurrich S. (2008). Among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy Researches, 32(5), 702-713. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6]

15. Moulds M. L., Kandris, E., Starr, S., & Wong, A. C. (2007). The relationship between rumination, avoidance and depression in a non-clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 251-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.003] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.003]

16. Nolen Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115-21. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115]

17. Nutt, D., Demyttenaere, K., Janka, Z., Aarre, T., Bourin, M., Canonico, P. L., et al. (2007). The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: The role of catecholamines in causation and cure. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 21(5), 461–71. [DOI:10.1177/0269881106069938] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/0269881106069938]

18. Rajabi, G., Gashtil, K., & Amanallahi, A. (2016). The relationship between self-compassion and depression with mediating's thought rumination and worry in female nurses. Iran Journal of Nursing, 29(99), 10-21. [DOI:10.29252/ijn.29.99.100.10]

19. Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., Nolen Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001]

20. Vergara-Lopez, C., Lopez-Vergara, H. I., & Roberts, J. E. (2016). Testing a "content meets process" model of depression vulnerability and rumination: Exploring the moderating role of set-shifting deficits. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 50, 201-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.08.002] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.08.002]

21. Vesal, M., Nazarinya, M. A. (2016). [Prediction of depression and sleep quality based on thought rumination and its components (inhibition and reflection) in patients with Rheumatoid arthritis (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 9(41), 47-56.

22. Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A Comprehensive Review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35(4), 416–31. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048] [PMID] [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048]

23. Yousefi, Z., Bahrami, F., & Mehrabi, H. A. (2008). Rumination: beginning and continuous of depression. Journal of Behavorial Sciences, 2(1), 67-73.

24. Zarei, M. (2017). [Mediating role of cognitive flexibility, shame, emotion dysregulation in the relationship between neurotism and depression in students in Tehran City (Persian) (Master thesis)]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation sciences.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |