Volume 7, Issue 2 (Spring 2019)

PCP 2019, 7(2): 87-94 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rostami R, Dasht Bozorgi Z. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Resiliency and Alexithymia of Somatic Symptoms. PCP 2019; 7 (2) :87-94

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-555-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-555-en.html

Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Resiliency and Alexithymia of Somatic Symptoms

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 673 kb]

(3010 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5726 Views)

Full-Text: (3838 Views)

1. Introduction

Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) is a chronic disorder and an increasing major health problem in developing countries (Shirkavand, Gholami Heydari, Arab Salari, Ashoori, 2015). SSD is characterized by the exaggerated symptoms and signs (distressing somatic symptoms and abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to these symptoms) rather than the medical explanation for somatic symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). SSD is defined as having physical symptoms with an unknown organic cause and or a maladaptive reaction to natural physical symptoms for at least 3 months that causes patients’ loss of function (Riem, Doedée, Broekhuizen-Dijksman, & Beijer, 2018). SSD is one of the most common chronic disorders that disrupts the normal pace of life and has important psychological consequences for the patients and their families (Batais, Schantter, 2016).

The risk factors for this disorder include female gender, childhood adversity, prior infections, low education, low socioeconomic status, recent threatening life events, anxiety and depressive disorders, neuroticism, general medical disorders, and various somatic symptoms (DSM V. 2013). The rate of SSD has increased dramatically during the past two decades and exceeded 285 million people worldwide in 2010, and it is estimated that this number will exceed 438 million people by 2030 (Creed, Tomenson, Chew-Graham, Macfarlane, & McBeth, 2018; Shaw, Sicree, & Zimmet, 2010).

The World Health Organization declared that the prevalence of SSD is 9.8% in men and 11.1% in women in Iran (Grover, Sahoo, Chakrabarti, & Avasthi, 2019). This disorder is the most common cause of amputations, blindness, chronic renal failure, and one of the risk factors for heart disorders (Chang, 2010). Somatic symptoms, regardless of psychiatric characteristics, physical ailments, and lifestyles can be a predictive factor that affects the prognosis of this disorder. Somatic symptoms also have negative consequences on the course of alexithymia (Zhao et al., 2018).

The patients with SSD are sensitive to negative emotions such as stress, fear, anger, and so on. They have difficulty in regulating their emotions and have much experience with ad emotions (Ghiasvand, & Ghorbani, 2015). Emotions have been of great interest to experts of psychology due to evolutionary, social, and communicative reasons and their impact on decision-making and health (Grezellschak, Lincolversen, & Westermann, 2015). Resiliency has received much attention as an essential process in the research and treatment of psychopathology and some physical pathological states. Resiliency refers to individuals’ competency to encounter events which are catastrophic (Yousefi, Asghari, & Toghyani, 2016).

The Resiliency Model is one of the most famous models for excitation control performed by the help of cognitive strategies and processes. Cognitive processes help people regulate their emotions (Zlomke & Hahn, 2010). Valrer (2010) defined resilience as people’s positive adaptation with adverse and unfavorable conditions (Bruggink, Huisman, Vuijk, Kraaij, & Garnefski, 2016).

Another problem faced by people with SSD is alexithymia. Those suffering from SSD face numerous emotional processing problems like alexithymia (Baigan, Khoshkonesh, Habibi Askarabad, & Fallahzade, 2016). Alexithymia is a deficit in the cognitive processing of emotional experience. It entails an impaired ability to construct mental representations of the emotions. These representations are required for cognitively processing emotional experiences and communicating them to others (Ogrodniczuk, Kealy, Joyce, & Abbass, 2018). Alexithymia has both cognitive aspect (i.e. the inability to identify, understand and interpret the emotions) and emotional aspect (i.e. the failure to respond and express one’s feelings) (Loas, Baelde, & Verrier, 2015). People with alexithymia also overestimate abnormal physical agitations, misinterpret the emotional arousal, and show emotional distress through physical complaints (DiStefano, & Koven, 2012).

Women with SSD encounter many problems, so there must be effective treatment methods to improve the psychological characteristics of these patients (George, & Joseph, 2014). One effective treatment method to improve the psychological traits that has recently been of great interest to many researchers is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (George & Joseph, 2014). Unlike many other treatment methods that focus on reducing or controlling the symptoms, the ACT method focuses on

increasing the acceptance of adverse reactions (e.g. negative thoughts and emotions) when it is not possible to change them directly (Baruch, Kanker, & Basch, 2012).

The ACT proponents believed that the thoughts and emotions must be understood in the conceptual context of the event. That is why the ACT method focuses on patients’ learning to accept their thoughts and feelings, live in “here” and “now” and show more flexibility. This approach is unlike the cognitive behavioral techniques that focus on modifying the inefficient cognitions and beliefs so that the emotions and behaviors can be changed (Poddar, Sinha, & Urbi, 2015). Many therapists help clients to have a better emotional feeling at the end of the treatment period, but the ACT method explicitly focuses on a better life, regardless of whether or not this better life matches with better feelings. Sometimes, a better life practically requires feeling some pain. If the sensation of pain leads to a better life, the ACT method seeks to provide the necessary skills for pain creation (Hayes, Levin, Plumb-Vilardaga,Villatte, & Pistorello, 2013).

The group therapy method is useful in several aspects. For example, this treatment method reduces the need for long waiting lists for training, helping the therapists to make better and more efficient use of their time. Besides, the group therapy method provides many benefits for the patients, for instance, their experience of being treated identically, modeling and imitating their peers, and receiving and delivering peer support (Skewes, Samson, Simpson, & Van Vreeswijk, 2015).

Although no research has been conducted on the impact of ACT on alexithymia, several studies have been carried out on the effect of ACT on resiliency. For example, Flujas-Contreras and Gómez (2018) reported that mother and son’s acceptance and valued actions were higher at the end of the treatment and sustained at follow-up. The intervention built a flexible behavioral repertoire not only for the mother, who received the direct intervention but also for her son’s behavior. Blackledge and Hayes (2001) researched emotion regulation based on the ACT and concluded that this therapy promoted emotion regulation (George, & Joseph, 2014).

White et al. (2011) also studied the effect of ACT on the emotional dysfunction in patients with psychosis and reported that this treatment method reduced emotional dysfunction. Mohammadi, Salehzade, and Nasirian (2015) also conducted a study entitled “The efficiency of the ACT-based therapy on the resiliency of the men treated with methadone”, and reported that ACT improved the men’s resiliency. Kiani, Ghasemi, and Pourabbas (2013) also conducted a study on the effect of the therapy based on ACT and mindfulness on the resiliency and concluded that the two methods improved the indices of resiliency.

Although the impact of ACT on psychological characteristics has been proven (George & Joseph, 2014), only a few studies have examined its effect on the resiliency, and no research has investigated its effect on alexithymia. Moreover, patients with SSD have difficulty in regulating their emotions and have much experience of negative emotions such as stress, anger, frustration, and depression (Ghiasvand, & Ghorbani, 2015). Considering the high number of people suffering from SSD and the importance of group therapy, we need to improve the psychological traits of the patients with SSD using appropriate group therapy. Therefore, the primary goal of this research is to investigate the effect of the group therapy ACT on the resiliency and alexithymia in women with SSD.

2. Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study conducted with pre-test and post-test design and control group. The study population included all of the women with SSD admitted to health centers in Ahvaz City, Iran, in 2016. In this study, 30 patients were recruited for the research sample using the convenience sampling method. They were randomly divided into experimental group and control group (15 patients for each group) as the sample size must be at least 15 people for each group in the experimental or quasi-experimental studies (Delavar, 2008). The inclusion criteria included having the consent for participation in the research, being between 30 and 45 years old, having at least a high school degree, not using psychiatric drugs, not receiving other treatments methods, and not experiencing stressful events such as divorce or the death of loved ones during the past six months. The exclusion criteria included missing more than one therapy session and filling out the questionnaire incompletely.

Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) is a chronic disorder and an increasing major health problem in developing countries (Shirkavand, Gholami Heydari, Arab Salari, Ashoori, 2015). SSD is characterized by the exaggerated symptoms and signs (distressing somatic symptoms and abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to these symptoms) rather than the medical explanation for somatic symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). SSD is defined as having physical symptoms with an unknown organic cause and or a maladaptive reaction to natural physical symptoms for at least 3 months that causes patients’ loss of function (Riem, Doedée, Broekhuizen-Dijksman, & Beijer, 2018). SSD is one of the most common chronic disorders that disrupts the normal pace of life and has important psychological consequences for the patients and their families (Batais, Schantter, 2016).

The risk factors for this disorder include female gender, childhood adversity, prior infections, low education, low socioeconomic status, recent threatening life events, anxiety and depressive disorders, neuroticism, general medical disorders, and various somatic symptoms (DSM V. 2013). The rate of SSD has increased dramatically during the past two decades and exceeded 285 million people worldwide in 2010, and it is estimated that this number will exceed 438 million people by 2030 (Creed, Tomenson, Chew-Graham, Macfarlane, & McBeth, 2018; Shaw, Sicree, & Zimmet, 2010).

The World Health Organization declared that the prevalence of SSD is 9.8% in men and 11.1% in women in Iran (Grover, Sahoo, Chakrabarti, & Avasthi, 2019). This disorder is the most common cause of amputations, blindness, chronic renal failure, and one of the risk factors for heart disorders (Chang, 2010). Somatic symptoms, regardless of psychiatric characteristics, physical ailments, and lifestyles can be a predictive factor that affects the prognosis of this disorder. Somatic symptoms also have negative consequences on the course of alexithymia (Zhao et al., 2018).

The patients with SSD are sensitive to negative emotions such as stress, fear, anger, and so on. They have difficulty in regulating their emotions and have much experience with ad emotions (Ghiasvand, & Ghorbani, 2015). Emotions have been of great interest to experts of psychology due to evolutionary, social, and communicative reasons and their impact on decision-making and health (Grezellschak, Lincolversen, & Westermann, 2015). Resiliency has received much attention as an essential process in the research and treatment of psychopathology and some physical pathological states. Resiliency refers to individuals’ competency to encounter events which are catastrophic (Yousefi, Asghari, & Toghyani, 2016).

The Resiliency Model is one of the most famous models for excitation control performed by the help of cognitive strategies and processes. Cognitive processes help people regulate their emotions (Zlomke & Hahn, 2010). Valrer (2010) defined resilience as people’s positive adaptation with adverse and unfavorable conditions (Bruggink, Huisman, Vuijk, Kraaij, & Garnefski, 2016).

Another problem faced by people with SSD is alexithymia. Those suffering from SSD face numerous emotional processing problems like alexithymia (Baigan, Khoshkonesh, Habibi Askarabad, & Fallahzade, 2016). Alexithymia is a deficit in the cognitive processing of emotional experience. It entails an impaired ability to construct mental representations of the emotions. These representations are required for cognitively processing emotional experiences and communicating them to others (Ogrodniczuk, Kealy, Joyce, & Abbass, 2018). Alexithymia has both cognitive aspect (i.e. the inability to identify, understand and interpret the emotions) and emotional aspect (i.e. the failure to respond and express one’s feelings) (Loas, Baelde, & Verrier, 2015). People with alexithymia also overestimate abnormal physical agitations, misinterpret the emotional arousal, and show emotional distress through physical complaints (DiStefano, & Koven, 2012).

Women with SSD encounter many problems, so there must be effective treatment methods to improve the psychological characteristics of these patients (George, & Joseph, 2014). One effective treatment method to improve the psychological traits that has recently been of great interest to many researchers is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (George & Joseph, 2014). Unlike many other treatment methods that focus on reducing or controlling the symptoms, the ACT method focuses on

increasing the acceptance of adverse reactions (e.g. negative thoughts and emotions) when it is not possible to change them directly (Baruch, Kanker, & Basch, 2012).

The ACT proponents believed that the thoughts and emotions must be understood in the conceptual context of the event. That is why the ACT method focuses on patients’ learning to accept their thoughts and feelings, live in “here” and “now” and show more flexibility. This approach is unlike the cognitive behavioral techniques that focus on modifying the inefficient cognitions and beliefs so that the emotions and behaviors can be changed (Poddar, Sinha, & Urbi, 2015). Many therapists help clients to have a better emotional feeling at the end of the treatment period, but the ACT method explicitly focuses on a better life, regardless of whether or not this better life matches with better feelings. Sometimes, a better life practically requires feeling some pain. If the sensation of pain leads to a better life, the ACT method seeks to provide the necessary skills for pain creation (Hayes, Levin, Plumb-Vilardaga,Villatte, & Pistorello, 2013).

The group therapy method is useful in several aspects. For example, this treatment method reduces the need for long waiting lists for training, helping the therapists to make better and more efficient use of their time. Besides, the group therapy method provides many benefits for the patients, for instance, their experience of being treated identically, modeling and imitating their peers, and receiving and delivering peer support (Skewes, Samson, Simpson, & Van Vreeswijk, 2015).

Although no research has been conducted on the impact of ACT on alexithymia, several studies have been carried out on the effect of ACT on resiliency. For example, Flujas-Contreras and Gómez (2018) reported that mother and son’s acceptance and valued actions were higher at the end of the treatment and sustained at follow-up. The intervention built a flexible behavioral repertoire not only for the mother, who received the direct intervention but also for her son’s behavior. Blackledge and Hayes (2001) researched emotion regulation based on the ACT and concluded that this therapy promoted emotion regulation (George, & Joseph, 2014).

White et al. (2011) also studied the effect of ACT on the emotional dysfunction in patients with psychosis and reported that this treatment method reduced emotional dysfunction. Mohammadi, Salehzade, and Nasirian (2015) also conducted a study entitled “The efficiency of the ACT-based therapy on the resiliency of the men treated with methadone”, and reported that ACT improved the men’s resiliency. Kiani, Ghasemi, and Pourabbas (2013) also conducted a study on the effect of the therapy based on ACT and mindfulness on the resiliency and concluded that the two methods improved the indices of resiliency.

Although the impact of ACT on psychological characteristics has been proven (George & Joseph, 2014), only a few studies have examined its effect on the resiliency, and no research has investigated its effect on alexithymia. Moreover, patients with SSD have difficulty in regulating their emotions and have much experience of negative emotions such as stress, anger, frustration, and depression (Ghiasvand, & Ghorbani, 2015). Considering the high number of people suffering from SSD and the importance of group therapy, we need to improve the psychological traits of the patients with SSD using appropriate group therapy. Therefore, the primary goal of this research is to investigate the effect of the group therapy ACT on the resiliency and alexithymia in women with SSD.

2. Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study conducted with pre-test and post-test design and control group. The study population included all of the women with SSD admitted to health centers in Ahvaz City, Iran, in 2016. In this study, 30 patients were recruited for the research sample using the convenience sampling method. They were randomly divided into experimental group and control group (15 patients for each group) as the sample size must be at least 15 people for each group in the experimental or quasi-experimental studies (Delavar, 2008). The inclusion criteria included having the consent for participation in the research, being between 30 and 45 years old, having at least a high school degree, not using psychiatric drugs, not receiving other treatments methods, and not experiencing stressful events such as divorce or the death of loved ones during the past six months. The exclusion criteria included missing more than one therapy session and filling out the questionnaire incompletely.

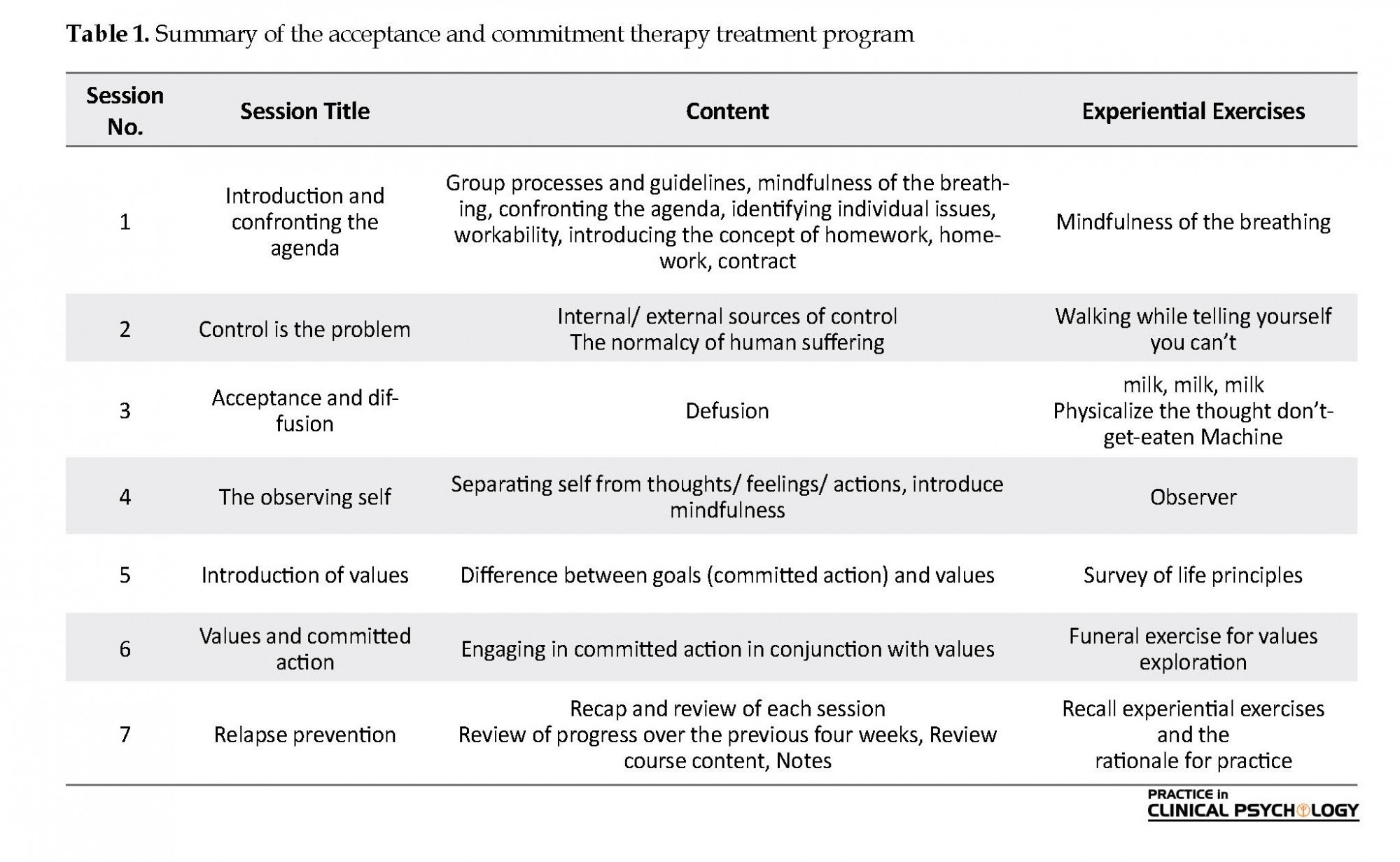

The experimental group was trained about the ACT method using group training during seven 90-minute sessions (two sessions per week), while the control group was placed in a waiting list for training. The contents of the ACT were based on Bach and Moran (2015) (Table 1). The data collection tools included Ganefeski et al. resiliency questionnaire and Bagby et al. Toronto alexithymia scale.

Resiliency was measured in this study based on Kanner et al. (2003) resiliency questionnaire. This scale has 25 5-option (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always) items. Thus the total score ranges between 25 and 100. About half of the items are scored in reverse direction, and the higher scores show greater ability and the lower scores lower strength in resiliency. Confirming the construct validity of the questionnaire, Mohammadi reported its reliability as 0.93 by calculating its Cronbach alpha.

Ghiasvand, and Ghorbani (2015) reported the questionnaire’s reliability as 0.87, and Mohammadi et al. (2015) adapted it for use in Iran. Mohammadi obtained the reliability coefficient of the scale as 0.89 and obtained the validity of the scale between 0.41 and 0.64 by correlating each item with the total score of the category. Moreover, the reliability of the resiliency sale was obtained as 0.83 and 0.77 using the Cronbach alpha and the Split-half method, respectively.

We used Bagby et al. Toronto alexithymia questionnaire to measure the alexithymia. This tool has 20 items scored based on a 5-point Likert-Type Scale (from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). Therefore, the total score ranges between 20 and 100. The higher scores mean greater alexithymia, and the lower scores indicate less alexithymia. Confirming the content validity of the questionnaire, Aydan reported its reliability as 0.82 using the Cronbach alpha (Aydan, 2015). Basharat (2007) reported its reliability as 0.85 using the Cronbach alpha, too.

The data were analyzed at the descriptive level using the central tendency and dispersion measures, and at the inferential level using the Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). All analyses were done in SPSS V. 21 at the significance level of 0.01. Ethical considerations of the research included the expression of the principle of privacy, the confidentiality of personal information, the freedom of the subjects to participate in the study, analyzing the data in general, and informing the outcome of the research to them.

3. Results

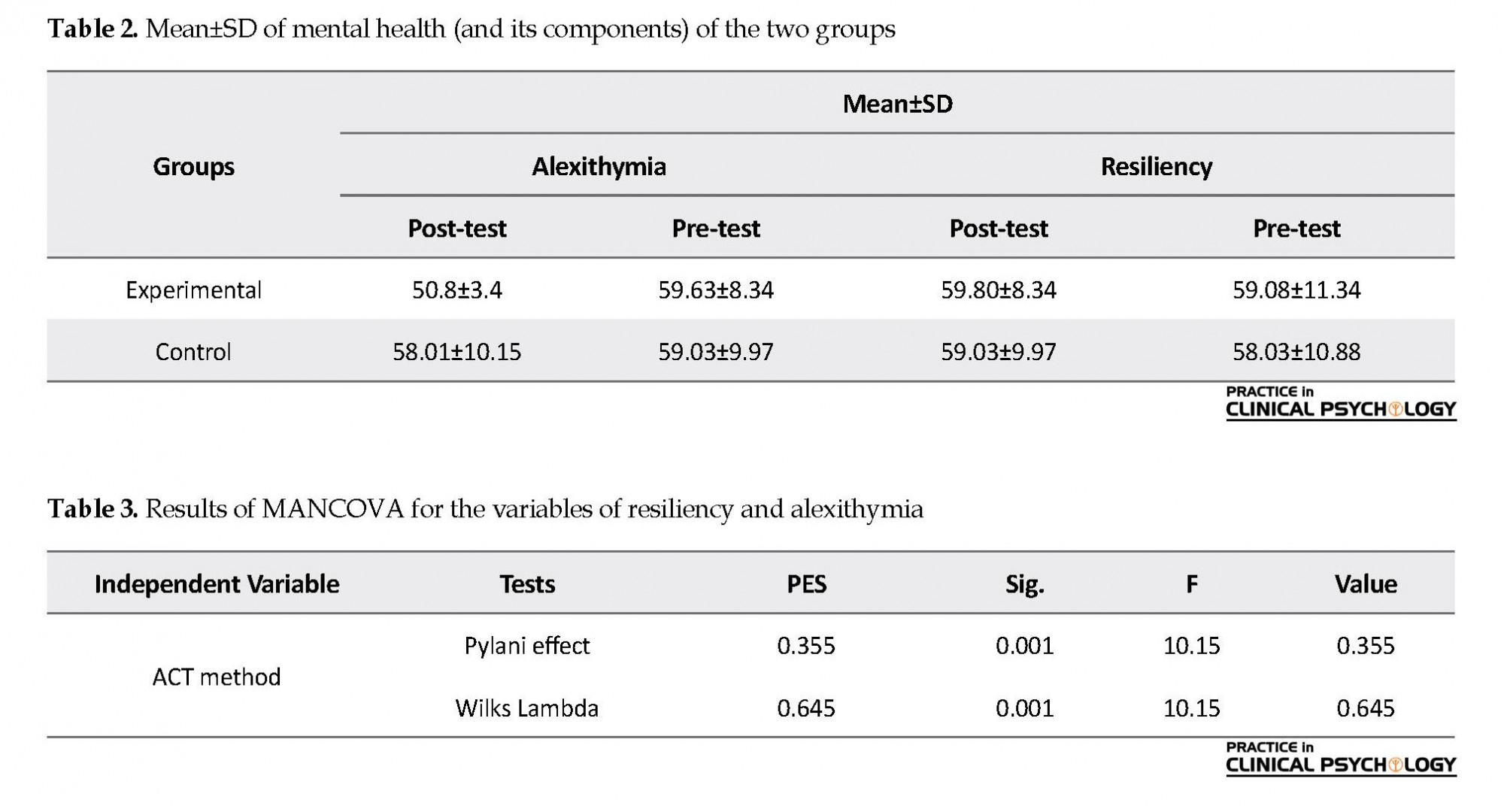

There were 8(53.33%) women and 7(46.67%) men in the experimental group, and 9(60%) women and 6(40%) men in the control group. In the experimental group, 1(6.67%) person had a high school diploma, 5(33.33%) had an associate’s degree, and 9 had bachelor’s degree, while in the control group there were 2(13.33%) women with the high school diploma, 3(20%) with the associate’s degree and 10(66.67%) with the bachelor’s degree. Before analyzing the data, we examined the assumptions of the analysis method using the Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for resiliency and alexithymia were not significant, which confirmed the normality assumption. Moreover, the results of the M-Box Test were not significant, suggested the equality of the covariance matrices. Also, the results of Levene’s Test were not significant, showed the equality of variances. Table 2 presents the mean and the standard deviation of the resiliency and alexithymia scores of the experimental and control groups in the pre-test and post-test.

Resiliency was measured in this study based on Kanner et al. (2003) resiliency questionnaire. This scale has 25 5-option (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always) items. Thus the total score ranges between 25 and 100. About half of the items are scored in reverse direction, and the higher scores show greater ability and the lower scores lower strength in resiliency. Confirming the construct validity of the questionnaire, Mohammadi reported its reliability as 0.93 by calculating its Cronbach alpha.

Ghiasvand, and Ghorbani (2015) reported the questionnaire’s reliability as 0.87, and Mohammadi et al. (2015) adapted it for use in Iran. Mohammadi obtained the reliability coefficient of the scale as 0.89 and obtained the validity of the scale between 0.41 and 0.64 by correlating each item with the total score of the category. Moreover, the reliability of the resiliency sale was obtained as 0.83 and 0.77 using the Cronbach alpha and the Split-half method, respectively.

We used Bagby et al. Toronto alexithymia questionnaire to measure the alexithymia. This tool has 20 items scored based on a 5-point Likert-Type Scale (from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). Therefore, the total score ranges between 20 and 100. The higher scores mean greater alexithymia, and the lower scores indicate less alexithymia. Confirming the content validity of the questionnaire, Aydan reported its reliability as 0.82 using the Cronbach alpha (Aydan, 2015). Basharat (2007) reported its reliability as 0.85 using the Cronbach alpha, too.

The data were analyzed at the descriptive level using the central tendency and dispersion measures, and at the inferential level using the Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). All analyses were done in SPSS V. 21 at the significance level of 0.01. Ethical considerations of the research included the expression of the principle of privacy, the confidentiality of personal information, the freedom of the subjects to participate in the study, analyzing the data in general, and informing the outcome of the research to them.

3. Results

There were 8(53.33%) women and 7(46.67%) men in the experimental group, and 9(60%) women and 6(40%) men in the control group. In the experimental group, 1(6.67%) person had a high school diploma, 5(33.33%) had an associate’s degree, and 9 had bachelor’s degree, while in the control group there were 2(13.33%) women with the high school diploma, 3(20%) with the associate’s degree and 10(66.67%) with the bachelor’s degree. Before analyzing the data, we examined the assumptions of the analysis method using the Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for resiliency and alexithymia were not significant, which confirmed the normality assumption. Moreover, the results of the M-Box Test were not significant, suggested the equality of the covariance matrices. Also, the results of Levene’s Test were not significant, showed the equality of variances. Table 2 presents the mean and the standard deviation of the resiliency and alexithymia scores of the experimental and control groups in the pre-test and post-test.

According to Table 2, the Mean±SD of resiliency and alexithymia scores in the experimental group were 59.80±8.34 and 59.63±8.34, respectively before the intervention, while they changed into 59.03±9.97 and 58.03±10.88, respectively after the intervention. However, they were respectively 58.93±10.15 and 59.03±9.97 in the control group before the intervention and changed into 58.03±10.88 and 59.03±9.97 respectively, after the intervention. Thus, the mean post-test scores of the experimental group were greater in resiliency and lower in alexithymia than those of the control group. Table 3 presents the results of the MANCOVA for the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variables.

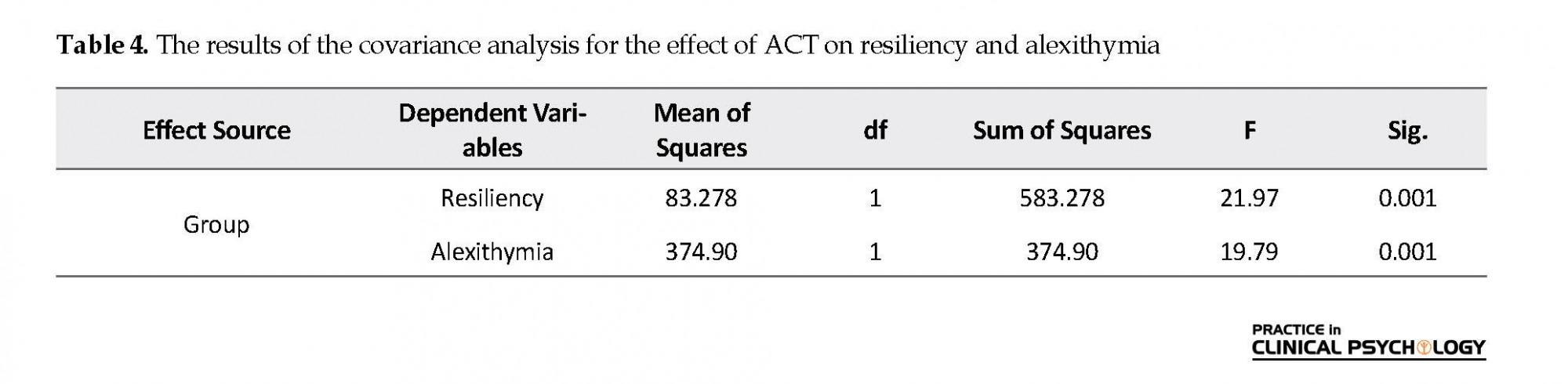

According to Table 3, the independent variable affected the dependent variables. In other words, the experimental group and the control group have a significant difference, at least in one of the two variables of resiliency and alexithymia (P≤0.001). Moreover, based on the values of the Eta square of Wilks Lambda test (0.654), we can say that the independent variable accounts for 64.5% of the total variance. Table 4 presents the results of the covariance analysis for the effect of ACT on the variables of resiliency and alexithymia. According to Table 4, ACT has a significant impact on the post-test scores and considering the Eta square, 87.9% of the changes of resiliency and 76.5% of the changes of alexithymia result from the ACT group therapy. Therefore, ACT significantly increased resiliency (P<0.001, F=21.97), and decreased alexithymia (P<0.001, F=20.492) among the women with SSD.

According to Table 3, the independent variable affected the dependent variables. In other words, the experimental group and the control group have a significant difference, at least in one of the two variables of resiliency and alexithymia (P≤0.001). Moreover, based on the values of the Eta square of Wilks Lambda test (0.654), we can say that the independent variable accounts for 64.5% of the total variance. Table 4 presents the results of the covariance analysis for the effect of ACT on the variables of resiliency and alexithymia. According to Table 4, ACT has a significant impact on the post-test scores and considering the Eta square, 87.9% of the changes of resiliency and 76.5% of the changes of alexithymia result from the ACT group therapy. Therefore, ACT significantly increased resiliency (P<0.001, F=21.97), and decreased alexithymia (P<0.001, F=20.492) among the women with SSD.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of group ACT therapy on the resiliency and alexithymia of the women with SSD. The findings indicate the effect of group therapy ACT on increasing resiliency that is consistent with the results of previous studies. For example, Blackledge and Hayes (2001) reported that ACT promoted emotion regulation (2001). Mohammadi et al. (2015) and Kiani et al. (2013), in their separate studies, concluded that the implementation of group ACT therapy improved resiliency. To explain the effect of ACT on increasing resiliency, we can say that the value-based action training along with a tendency to act as the purposeful personal goals before the elimination of unwanted experiences. In this treatment method, the patients maintain their values when expressing their thoughts and feelings in the face of problems. In this way, their possible anxiety, irritability, fear, impatience, and restlessness will reduce in this situation. Eventually, the patients maintain their health and energy and improve their performance in dealing with precarious problems, leading to resiliency.

Moreover, these strategies help patients promote their lives by increasing psychological acceptance of their inner experiences, thinking of their values and tackling the less avoidable problems instead of intellectual and practical avoidance of social thoughts and social positions. Active confrontation with emotions, a change of one’s views of oneself and the challenges, revisiting the values and life goals and finally, a committing to social goals can be considered the main elements of this approach (Abbasi, Mahmoudian, & Rezvani Far, 2014). Ultimately, the effectiveness of ACT may be attributed to the techniques used in this approach, as well as its well-expressed goals and focus on commitment-based action.

Encouraging the patients to identify and set their goals, actions, and barriers, and ultimately their commitment to do so to achieve their goals and move towards the values despite various problems help them to achieve their goals, become satisfied with their lives, and get rid of the negative thoughts and feelings. Disposing of emotions like anxiety, stress, frustration, despair, and depression, which increase the severity of the problems, eventually leads to increased resiliency (Mohammadi et al., 2015). Other findings show the impact of ACT on the reduction of alexithymia, which is consistent in part with the findings of previous studies. For example, White et al. (2015) carried out a study on the effect of ACT on emotional dysfunction in patients with psychosis and reported that this treatment method reduced emotional dysfunction.

Barzgari Dehaj (2015) conducted a study entitled «the efficiency of ACT-based therapy on the regulation of adolescents’ emotional and mental states” and concluded that ACT improved the adolescents’ mood emotional states. The impact of ACT on the reduction of alexithymia can be attributed to the fact that this method contributes to further understanding of facing the challenges of life by providing the technique of acceptance or willingness to cope with hardships or other disturbing events without taking actions to control them. Thus, the patients feel that they are capable of coping with their personal, familial, and social lives’ challenges.

Consequently, this response leads to the reduction of avoidance, distress, and fear of challenges and finally to the reduction of alexithymia. This may also be justified by the fact that the primary goal of ACT is to create and increase flexibility. That is, to create the ability to select a more relevant option from the various existing options, and this helps increase resilience, psychological well-being, and relaxation. ACT also helps people identify the stresses of their lives, which is a prerequisite for their coping with the sources of stress. Therefore, ACT reduces alexithymia by assisting people in identifying the emotional states and know how to express their excitement. The last explanation is based on the viewpoint held by Aminpour and Ghorbani (2015), saying that non-judgmental acceptance is very important. This is because a person with high acceptance can easily notice the excitations of their thoughts and feelings without trying to control, avoid, or escape from them, which has positive results.

In contrast, a person with a low level of acceptance will easily be subject to psychological excitations and strategies for transformation and overwhelming thoughts and feelings. For example, he will attempt to justify or suppress his or her ideas. Therefore, ACT reduces alexithymia by training acceptance and commitment to implement it.

The first and most important limitation of the study was the poor-prepared conditions for the follow-up implementation. Other limitations included the use of convenience sampling method, and the sample’s being confined to women with SSD in Ahvaz City, which limits the generalization of the results. Therefore, it is suggested that short- and long-term follow-ups are used in future studies so that the sustainability of the results be investigated in much greater detail. Besides, the effectiveness of ACT in comparison with other positive and negative psychological characteristics and other methods such as schema therapy, spiritual therapy, reality therapy, medication and so on are other suitable topics to investigate in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information;Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research was extracted from first author’s MSc. thesis in Faculty of Psychology, Ahvaz University (approval code of 96.20.785).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

In the end, we would like to sincerely appreciate the health centers in the city of Ahvaz and all women with SSD for their collaboration with the researchers.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

Aminpour, R., & Ghorbani, M. (2015). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on stress coping strategies in women with ulcerative colitis. Iran Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Govaresh), 20(1), 1-9.

Aydan, A. (2015). A comparison of the alexithymia, self-compassion and humour characteristics of the parents with mentally disabled and autistic children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 720-9.[DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.607]

Bach, P. A., & Moran, D. J. (2015). ACT in practice: case conceptualization in acceptance and commitment therapy [S. Kamali, N Kianrad, Persian Trans.]. Tehran: Arjmand.

Baigan, K., Khoshkonesh, A., Habibi Askarabad, M., Fallahzade, H. (2016). [Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral group therapy in alexithymia, stress, and diabetes symptoms among somatic symptom patients (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 4(2), 8-18.

Baruch, D., Kanker, J., & Busch, A. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: enhancing the relationships. Journal of Clinical Case Studies, 8(3), 241-57. [DOI:10.1177/1534650109334818]

Barzegari Dehaj, A. (2015). [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on emotion regulation and mood status in adolescents (Persian)] [MA thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabataba'i University.

Batais, M. A., & Schantter, P. (2016). Prevalence of unwillingness to use insulin therapy and its associated attitudes amongst patients with somatic symptom in Saudi Arabia. Prim Care Diabetes, 10(6), 415-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.pcd.2016.05.007] [PMID]

Besharat, M. A. (2007). Reliability and factorial validity of Farsi version of the Toronto alexithymia scale with a sample of Iranian students. Psychological Reports, 101(1), 209-20. [DOI:10.2466/PR0.101.5.209-220] [PMID]

Blackledge, J. D., & Hayes, S. C. (2001). Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 243-55. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:23.0.CO;2-X]

Bruggink A, Huisman S, Vuijk R, Kraaij V, & Garnefski N. (2016). Resiliency, anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 22(2), 34-44. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.003]

Creed, F., Tomenson, B., Chew-Graham, C., Macfarlane, G., & McBeth, J. (2018). The associated features of multiple somatic symptom complexes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 1-8.

Chang, K. (2010). Comorbidities, quality of life and patients' willingness to pay for a cure for type 2 diabetes in Taiwan. Public Health, 124(5), 284-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.019] [PMID]

Delavar, A. (2008). [Theoretical and practical research in the humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd Publisher.

Distefano, R. A., & Koven, N. S. (2012). Dysfunctional emotion processing may explain visual memory deficits in alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 611-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.007]

Flujas-Contreras, J. M., & Gómez, I. (2018). Improving flexible parenting with acceptance and commitment therapy: A case study. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 8(3), 29-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.02.006]

George, R. E., & Joseph, S. (2014). A review of newer treatment approaches for type-2 diabetes: Focusing safety and efficacy of incretin based therapy. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 22(5), 403-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2013.05.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ghiasvand, M., & Ghorbani, M. (2015). [Effectiveness of emotion regulation training in improving emotion regulation strategies and control glycemic in type 2 diabetes patients (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 17(4), 299-307.

Grezellschak, S., Lincoln, T. M., & Westermann, S. (2015). Cognitive emotion regulation in patients with schizophrenia: evidence for effective reappraisal and distraction. Psychiatry Research, 229(1-2), 434-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.103] [PMID]

Grover, S., Sahoo, S., Chakrabarti, S., & Avasthi, A. (2019). Anxiety and Somatic Symptoms among elderly patients with Depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 66-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2018.07.009] [PMID]

Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 180-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kiani, A., Ghasemi, N., & Pourabbas, A. (2013). [The comparsion of the efficacy of group psychotherapy based on acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness on craving and cognitive emotion regulation in methamphetamine addicts (Persian)]. Research on Addiction, 6(24), 27-36.

Kanner S, Hamrin V, Grey M. (2003). Depression in adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 16(1), 15–24.

Loas, G., Baelde, O., & Verrier, A. (2015). Relationship between alexithymia and dependent personality disorder: a dimensional analysis. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 484-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.062] [PMID]

Mohammadi, L., Salehzade, A. M., & Nasirian, M. (2015). [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on cognitive emotion regulation in men under methadone treatment (Persian)]. Journal of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, 23(9), 853-61.

Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Kealy, D., Joyce, A. S., & Abbass, A. A. (2018). Body talk: Sex differences in the influence of alexithymia on physical complaints among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 261, 168-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.072] [PMID]

Poddar, S., Sinha, V. K., & Urbi, M. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy on parents of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches, 1(3), 221-5. [DOI:10.4103/2395-2296.158331]

Riem, M. M., Doedée, E. N., Broekhuizen-Dijksman, S. C., & Beijer, E. (2018). Attachment and medically unexplained somatic symptoms: The role of mentalization. Psychiatry Research, 268, 108-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.056] [PMID]

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A., & Zimmet, P. Z. (2010). Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87(1), 4-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007] [PMID]

Shirkavand, N., Gholami Heydari, S., Arab Salari, Z., Ashoori, J. (2015). [The impact of life skills training on happiness and hopefulness among patients with type II diabetes (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 3(3), 8-19.

Skewes, S. A., Samson, R. A., Simpson, S. G., & van Vreeswijk, M. (2015). Short-term group schema therapy for mixed personality disorders: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1592-8. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01592] [PMID] [PMCID]

White, R., Gumley, A., McTaggart, J., Rattrie, L., McConville, D., Cleare, S., et al. (2011). A feasibility study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for emotional dysfunction following psychosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(12), 901-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.003] [PMID]

Yousefi, R., Asghari, H., Toghyani, E. (2016). [Comparison of early maladaptive schemas and resiliency in cardiac patients and normal individuals (Persian)]. Journal of Advances in Medical and Biomedical Research, 24(107), 130-43.

Zhao, D., Wu, Z., Zhang, H., Mellor, D., Ding, L., Wu, H., et al. (2018). Somatic symptoms vary in major depressive disorder in China. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 87, 32-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.08.013] [PMID]

Zlomke, K. R., & Hahn, K. S. (2010). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies: Gender differences and associations to worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(4), 408-13.[DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.007]

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of group ACT therapy on the resiliency and alexithymia of the women with SSD. The findings indicate the effect of group therapy ACT on increasing resiliency that is consistent with the results of previous studies. For example, Blackledge and Hayes (2001) reported that ACT promoted emotion regulation (2001). Mohammadi et al. (2015) and Kiani et al. (2013), in their separate studies, concluded that the implementation of group ACT therapy improved resiliency. To explain the effect of ACT on increasing resiliency, we can say that the value-based action training along with a tendency to act as the purposeful personal goals before the elimination of unwanted experiences. In this treatment method, the patients maintain their values when expressing their thoughts and feelings in the face of problems. In this way, their possible anxiety, irritability, fear, impatience, and restlessness will reduce in this situation. Eventually, the patients maintain their health and energy and improve their performance in dealing with precarious problems, leading to resiliency.

Moreover, these strategies help patients promote their lives by increasing psychological acceptance of their inner experiences, thinking of their values and tackling the less avoidable problems instead of intellectual and practical avoidance of social thoughts and social positions. Active confrontation with emotions, a change of one’s views of oneself and the challenges, revisiting the values and life goals and finally, a committing to social goals can be considered the main elements of this approach (Abbasi, Mahmoudian, & Rezvani Far, 2014). Ultimately, the effectiveness of ACT may be attributed to the techniques used in this approach, as well as its well-expressed goals and focus on commitment-based action.

Encouraging the patients to identify and set their goals, actions, and barriers, and ultimately their commitment to do so to achieve their goals and move towards the values despite various problems help them to achieve their goals, become satisfied with their lives, and get rid of the negative thoughts and feelings. Disposing of emotions like anxiety, stress, frustration, despair, and depression, which increase the severity of the problems, eventually leads to increased resiliency (Mohammadi et al., 2015). Other findings show the impact of ACT on the reduction of alexithymia, which is consistent in part with the findings of previous studies. For example, White et al. (2015) carried out a study on the effect of ACT on emotional dysfunction in patients with psychosis and reported that this treatment method reduced emotional dysfunction.

Barzgari Dehaj (2015) conducted a study entitled «the efficiency of ACT-based therapy on the regulation of adolescents’ emotional and mental states” and concluded that ACT improved the adolescents’ mood emotional states. The impact of ACT on the reduction of alexithymia can be attributed to the fact that this method contributes to further understanding of facing the challenges of life by providing the technique of acceptance or willingness to cope with hardships or other disturbing events without taking actions to control them. Thus, the patients feel that they are capable of coping with their personal, familial, and social lives’ challenges.

Consequently, this response leads to the reduction of avoidance, distress, and fear of challenges and finally to the reduction of alexithymia. This may also be justified by the fact that the primary goal of ACT is to create and increase flexibility. That is, to create the ability to select a more relevant option from the various existing options, and this helps increase resilience, psychological well-being, and relaxation. ACT also helps people identify the stresses of their lives, which is a prerequisite for their coping with the sources of stress. Therefore, ACT reduces alexithymia by assisting people in identifying the emotional states and know how to express their excitement. The last explanation is based on the viewpoint held by Aminpour and Ghorbani (2015), saying that non-judgmental acceptance is very important. This is because a person with high acceptance can easily notice the excitations of their thoughts and feelings without trying to control, avoid, or escape from them, which has positive results.

In contrast, a person with a low level of acceptance will easily be subject to psychological excitations and strategies for transformation and overwhelming thoughts and feelings. For example, he will attempt to justify or suppress his or her ideas. Therefore, ACT reduces alexithymia by training acceptance and commitment to implement it.

The first and most important limitation of the study was the poor-prepared conditions for the follow-up implementation. Other limitations included the use of convenience sampling method, and the sample’s being confined to women with SSD in Ahvaz City, which limits the generalization of the results. Therefore, it is suggested that short- and long-term follow-ups are used in future studies so that the sustainability of the results be investigated in much greater detail. Besides, the effectiveness of ACT in comparison with other positive and negative psychological characteristics and other methods such as schema therapy, spiritual therapy, reality therapy, medication and so on are other suitable topics to investigate in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information;Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research was extracted from first author’s MSc. thesis in Faculty of Psychology, Ahvaz University (approval code of 96.20.785).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

In the end, we would like to sincerely appreciate the health centers in the city of Ahvaz and all women with SSD for their collaboration with the researchers.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

Aminpour, R., & Ghorbani, M. (2015). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on stress coping strategies in women with ulcerative colitis. Iran Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Govaresh), 20(1), 1-9.

Aydan, A. (2015). A comparison of the alexithymia, self-compassion and humour characteristics of the parents with mentally disabled and autistic children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 720-9.[DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.607]

Bach, P. A., & Moran, D. J. (2015). ACT in practice: case conceptualization in acceptance and commitment therapy [S. Kamali, N Kianrad, Persian Trans.]. Tehran: Arjmand.

Baigan, K., Khoshkonesh, A., Habibi Askarabad, M., Fallahzade, H. (2016). [Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral group therapy in alexithymia, stress, and diabetes symptoms among somatic symptom patients (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 4(2), 8-18.

Baruch, D., Kanker, J., & Busch, A. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: enhancing the relationships. Journal of Clinical Case Studies, 8(3), 241-57. [DOI:10.1177/1534650109334818]

Barzegari Dehaj, A. (2015). [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on emotion regulation and mood status in adolescents (Persian)] [MA thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabataba'i University.

Batais, M. A., & Schantter, P. (2016). Prevalence of unwillingness to use insulin therapy and its associated attitudes amongst patients with somatic symptom in Saudi Arabia. Prim Care Diabetes, 10(6), 415-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.pcd.2016.05.007] [PMID]

Besharat, M. A. (2007). Reliability and factorial validity of Farsi version of the Toronto alexithymia scale with a sample of Iranian students. Psychological Reports, 101(1), 209-20. [DOI:10.2466/PR0.101.5.209-220] [PMID]

Blackledge, J. D., & Hayes, S. C. (2001). Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 243-55. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:23.0.CO;2-X]

Bruggink A, Huisman S, Vuijk R, Kraaij V, & Garnefski N. (2016). Resiliency, anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 22(2), 34-44. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.003]

Creed, F., Tomenson, B., Chew-Graham, C., Macfarlane, G., & McBeth, J. (2018). The associated features of multiple somatic symptom complexes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 1-8.

Chang, K. (2010). Comorbidities, quality of life and patients' willingness to pay for a cure for type 2 diabetes in Taiwan. Public Health, 124(5), 284-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.019] [PMID]

Delavar, A. (2008). [Theoretical and practical research in the humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd Publisher.

Distefano, R. A., & Koven, N. S. (2012). Dysfunctional emotion processing may explain visual memory deficits in alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 611-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.007]

Flujas-Contreras, J. M., & Gómez, I. (2018). Improving flexible parenting with acceptance and commitment therapy: A case study. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 8(3), 29-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.02.006]

George, R. E., & Joseph, S. (2014). A review of newer treatment approaches for type-2 diabetes: Focusing safety and efficacy of incretin based therapy. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 22(5), 403-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2013.05.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ghiasvand, M., & Ghorbani, M. (2015). [Effectiveness of emotion regulation training in improving emotion regulation strategies and control glycemic in type 2 diabetes patients (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 17(4), 299-307.

Grezellschak, S., Lincoln, T. M., & Westermann, S. (2015). Cognitive emotion regulation in patients with schizophrenia: evidence for effective reappraisal and distraction. Psychiatry Research, 229(1-2), 434-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.103] [PMID]

Grover, S., Sahoo, S., Chakrabarti, S., & Avasthi, A. (2019). Anxiety and Somatic Symptoms among elderly patients with Depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 66-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2018.07.009] [PMID]

Hayes, S. C., Levin, M. E., Plumb-Vilardaga, J., Villatte, J. L., & Pistorello, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 180-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kiani, A., Ghasemi, N., & Pourabbas, A. (2013). [The comparsion of the efficacy of group psychotherapy based on acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness on craving and cognitive emotion regulation in methamphetamine addicts (Persian)]. Research on Addiction, 6(24), 27-36.

Kanner S, Hamrin V, Grey M. (2003). Depression in adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 16(1), 15–24.

Loas, G., Baelde, O., & Verrier, A. (2015). Relationship between alexithymia and dependent personality disorder: a dimensional analysis. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 484-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.062] [PMID]

Mohammadi, L., Salehzade, A. M., & Nasirian, M. (2015). [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on cognitive emotion regulation in men under methadone treatment (Persian)]. Journal of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, 23(9), 853-61.

Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Kealy, D., Joyce, A. S., & Abbass, A. A. (2018). Body talk: Sex differences in the influence of alexithymia on physical complaints among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 261, 168-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.072] [PMID]

Poddar, S., Sinha, V. K., & Urbi, M. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy on parents of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches, 1(3), 221-5. [DOI:10.4103/2395-2296.158331]

Riem, M. M., Doedée, E. N., Broekhuizen-Dijksman, S. C., & Beijer, E. (2018). Attachment and medically unexplained somatic symptoms: The role of mentalization. Psychiatry Research, 268, 108-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.056] [PMID]

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A., & Zimmet, P. Z. (2010). Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87(1), 4-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007] [PMID]

Shirkavand, N., Gholami Heydari, S., Arab Salari, Z., Ashoori, J. (2015). [The impact of life skills training on happiness and hopefulness among patients with type II diabetes (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 3(3), 8-19.

Skewes, S. A., Samson, R. A., Simpson, S. G., & van Vreeswijk, M. (2015). Short-term group schema therapy for mixed personality disorders: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1592-8. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01592] [PMID] [PMCID]

White, R., Gumley, A., McTaggart, J., Rattrie, L., McConville, D., Cleare, S., et al. (2011). A feasibility study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for emotional dysfunction following psychosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(12), 901-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.003] [PMID]

Yousefi, R., Asghari, H., Toghyani, E. (2016). [Comparison of early maladaptive schemas and resiliency in cardiac patients and normal individuals (Persian)]. Journal of Advances in Medical and Biomedical Research, 24(107), 130-43.

Zhao, D., Wu, Z., Zhang, H., Mellor, D., Ding, L., Wu, H., et al. (2018). Somatic symptoms vary in major depressive disorder in China. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 87, 32-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.08.013] [PMID]

Zlomke, K. R., & Hahn, K. S. (2010). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies: Gender differences and associations to worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(4), 408-13.[DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.007]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Psychiatry

Received: 2018/12/7 | Accepted: 2019/02/19 | Published: 2019/04/1

Received: 2018/12/7 | Accepted: 2019/02/19 | Published: 2019/04/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |