Volume 7, Issue 1 (Winter 2019)

PCP 2019, 7(1): 43-52 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Omidian M, Rahimian Boogar I, Talepasand S, Najafi M, Kaveh M. The Cultural Tailoring and Effectiveness of Couples Coping Enhancement Training on Marital Adjustment of Wives. PCP 2019; 7 (1) :43-52

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-547-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-547-en.html

1- Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran. ,i_rahimian@semnan.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

4- Department of Counseling and Psychology, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

4- Department of Counseling and Psychology, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 698 kb]

(3182 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (7114 Views)

In these studies, CCET or CCET-related interventions resulted in a better marital adjustment of couples, increased their quality of marital relationships and empowered marital coping strategies. In addition, these findings are consistent with the results of the study by Schaer, Bodenmann, and Klink (2008). Self-report data in pre-test, post-test (2 weeks after intervention) and follow-up (6 months after training) showed that CCET enhanced marital adjustment of the couples, empowered them in effective negotiation and increased compromise with the wives. Moreover, the results of this research are consistent with the study results of Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) and Ying et al. (2017) whose findings indicated that marital satisfaction and effective communication skills increased with implementing CCET.

There are many reasons that group method intervention is beneficial in a special way to improve marital adjustment of wives at this study. In group CCET, partner’s learning from each other about adaptive interaction and joined compromise is an effective strategy to control stress symptoms and improve marital adjustment. Improving marital adjustment of wives is affected by the group compressed intervention sessions because of different couple education and reciprocal interactions in educational sessions. This intervention, as a valuable method for stress management, is a great way to improve marital adjustment. Compromising skills in wives provide an opportunity to decrease stress and increase corrective marital communication in the long term. Also, couples in this study received eight intervention sessions. We can infer that there may be a stronger link among couples and the trainer to facilitate the effectiveness and permanent outcomes of the intervention.

According to the observed effect of culturally tailored CCET in the marital adjustment of wives, this intervention has higher and longer effects compared with the similar studies on interventions in marital adjustment. To explain this result, it can be said that education and enriched marital adjustment in CCET is based on stress management as stress is a main negative factor in marital discord. In addition, as Bodenmann (2005) previously argued, we can say that stress in one of the main sources of marital conflict of couples. Landis, Peter-Wight, Martin nad Bodenman (2013) argued that enrichment and skill training for stress management resulted in the higher quality of couples’ coping with stress, decreased negative effects of stress on marital interactions and marital adjustment of wives.

However, with regard to the small sample and quasi-experimental design of this study, we cannot generalize the results of this intervention to other samples and statistical populations. It is suggested that in future studies researchers use additional sessions or more CCET training to extend intervention or the period of treatment and follow-up sessions for testing results generalizability.

Our results indicate that CCET based on cultural tailoring can improve the marital adjustment of wives in a sample of troubled couples referring to Judiciary Office of Shahr-e Kord City, Iran in 6 months period. This research has some limitations, too. Its convenience sampling method, restricted research population, self-report instrument, and lack of qualitative assessments are the most important limitations of this study. So, it is recommended that this intervention in quantitative and qualitative research designs be conducted in other communities with random sampling method and more sample size. In addition, it can be suggested that the effect of this intervention be compared with other couple therapy interventions to determine how effective CCET based on cultural tailoring is. The results of this study have implications for marriage counseling and treatment centers, family counselors and psychotherapists, and divorce prevention and reduction centers. Providing educational brochures, booklets, books and educational videos based on CCET therapeutic approach is suggested, too.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

The present paper was extracted from the PhD. dissertation of the Mahdi Omidian in Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Methodology: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Investigation: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Manijeh Kaveh; Writing-original draft: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar; Writing-review & editing: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Funding acquisition: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar; Resources: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; and Supervision: Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Semnan University Graduate Education.

References

Full-Text: (2800 Views)

1. Introduction

Reported by the Iranian Civil Registration Organization, the divorce rate is growing exponentially so that the ratio of divorce in Iran ranged from 4.4 in 2006 to 28.8 in 2014, and in 2015 it reached the 4 to 1 ratio (marriage to divorce ratio), that is, the growth of approximately 24% divorce in Iran (Heshmati, Gharedaghi, Jafari, & Qolizadegan, 2017). On the other hand, let alone marriages ending up in official divorce, many unsatisfied couples decide to keep on their marital life for a variety of reasons, such as financial problems or individual and cultural perspectives about divorce (Sudani, Dastan, Khojastemehr, & Rajabi, 2015).

Marital adjustment of wives, as an important variable in marriage, is a situation where wife and husband feel satisfaction from marriage, relating with each other in a respectful and reciprocal manner, and have collaborative decision-making, effective familial performance, and sexual adjustment (Peterson-Post, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2014; Li, Robustelli, & Whisman, 2016; Salimi, Mohsenzadeh, & Nazari, 2016). Marital adjustment of wives has a special role in the family and marital relationship (Rostami, Abolghasemi, & Narimani, 2016). It is a process in which each member of a couple modifies his or her behavior patterns individually or jointly to achieve maximum marital satisfaction at their relationship. And this entails adapting of their tastes, knowing of personal traits, creating behavioral rules, and formation of relationship patterns (Bali, Dhingra & Baru, 2010).

Marital adjustment of wives includes mutual agreement and satisfaction, and affective expression (Sudani et al., 2015). Mutual agreement refers to how much couples agree on important topics like financial affairs management and making important decisions. Mutual correlation refers to how often both couples are involved in common activities. Affective expression refers to how often couples express love and affection to each other. Finally, mutual satisfaction relates to the amount of happiness in relationships and frequency of conflicts experienced in a relationship (Sanai Zaker, 2009). Moreover, marital adjustment of wives is a systematic approach to the concept of adaptation in the couple’s relationships.

Accordingly, the husband expresses his stress in verbal or non-verbal ways, and his wife responds in three ways: 1. Gets affected (i.e. stress transition occurs); 2. Completely ignores stressor and does not react; and 3. Acts based on one of two positive and negative adaptive behaviors. A stress transfer process involves the adjustment responses of both spouses. Good adjustment is defined as returning to performance before the stressor or optimal marital adjustment is defined as a return to the functions before the stressor (Falconier, Nussbeck, Bodenmann, Schneider, & Bradbury, 2015).

In recent years, according to Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) approach, one of the training programs that has drawn special attention to improve marital adjustment of wives and finally prevention of divorce is the Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) that has been designed based on dyadic coping enrichment model (Bodenmann, 1997) and emphasizes on importance of dyadic coping skills in improving satisfaction with the relationship. It helps couples identify, express, and manage stressful situations, especially situations outside the marital relationship. The interventional techniques in CCET include completing the stress questionnaire, time management training, progressive muscle relaxation, and role-play exercises (Davis & Davis, 2014).

Although, relationship skills and problem solving are repeatedly proposed as the main predictor of marriage quality and sustainability in the common couples’ education (For example, prevention and relationship enhancement program), individual and couple adjustment skills also play an important role in marital quality and sustainability (Bodenmann, Pihet, Shantinath, Cina, & Widmer, 2006). In addition, studies by Bodenmann (2005) and Bodenmann, Ledermann and Bradbury (2007) suggest that a greater number of couples show pre-existing flaws in relationship skills and miss it in stressful situations. Stress can reduce the time of being together, the opportunity to gain common experience, mutual emotional self-disclosure, kindness, sexual relationship satisfaction, and marital quality relationship (Bodenmann, 2005).

In stressful conditions, positive behaviors, including active listening, expressing interest, and empathy between couples decrease and negative behaviors that are high-risk factors for divorce such as criticizing, humiliation, disrespect, hostility, and withdrawal noticeably increases (Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004). A great number of marital relationships will be hurt without the skill of appropriate adjustment with stress. Lack of appropriate adjustment with stress in couples is one of the important causes of high divorce rate (Falconier et al., 2015; Davis & Davis, 2014; Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004). The most damaging variables for adjustment are external mild chronic stressors that spread to sincere relationships. These stressors are the reason of tension, conflict, and alienation between spouses and increase the possibility of divorce (Bodenmann, Meuwly, Bradbury, Gmelch, & Ledermann, 2010).

The couples enrichment Program is associated with the high satisfaction of couples (Bodenmann and Shantinath, 2004). CCET affects individual and dyadic adjustment, couples coping, marital satisfaction, marital quality, conflict resolution styles, effective conversation, and sincere security in couples (Bodenmann, 2000; Bodenmann, & Charvoz, Cina, & Widmer, 2001; Cina, Widmer & Bodenmann, 2002; Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004; Ledermann, Bodenmann & Cina, 2007; Schaer, Bodenmann & Klink, 2008; Ozouni-Davaji, Dadkhah, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, & Dolatshahi, 2012; Marshall, Jones, & Feinberg, 2011; Falconier et al., 2015). Although the effectiveness of the CCET is well supported, most studies in this topic have been conducted in different cultural societies from Iranian culture and are based on different definitions of marital adjustment and family pillars. In addition, these studies have often examined the effectiveness of the CCET on marital relationships. In this study, the cultural tailoring/adaptation of this intervention was performed, and the study focused on marital adjustment and the couple’s compatibility.

Although numerous psychological interventions have been already performed on psycho-social dimensions of marriage health in Iran, no research has been ever done in the field of interventional couples coping enrichment in improving marital adjustment of wives in Iranian samples. The distinguishing feature of CCET is its focus on stress and coping theory in marital relationships. In addition to educating communication skills and problem solving, CCET focuses on the individual and dyadic coping of couples to improve marital satisfaction and reduce emotional distress. This intervention is also suitable for couples with long-lasting maladaptive relationships as well as an appropriate model for avoiding divorce (Bodenmann & Shantiath, 2004; Bodenmann et al., 2006). Another limitation is the lack of cultural tailoring in CCET according to the needs of different populations because interventions will be more effective when reflecting cultural norms, values, and beliefs (Archibald, 2011).

Cultural tailoring or adaptation has been defined as the systematic modification of a treatment or intervention protocol to consider culture, language, and context so that it fits with the cultural patterns, values, and meanings for the target people (Bernal, Jimenez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009). The CCET is a tailored intervention to prevent marital distress or marital maladjustment based on stress and coping in various cultures (Ledermann, et al., 2007). For example, excitement is a prestigious cultural component, but in an Asian culture society with a focus on collectivism, there is a different meaning for excitement than individualist societies. This lack of access and limited emotional expression, in turn, is an important factor in reducing the marital adjustment of wives (Batool & Khalid, 2009). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to study the cultural tailoring and the effectiveness of CCET to improve marital adjustment of wives and answer the fundamental question that is whether CCET based on cultural tailoring is effective on improving marital adjustment of wives in this study.

2. Methods

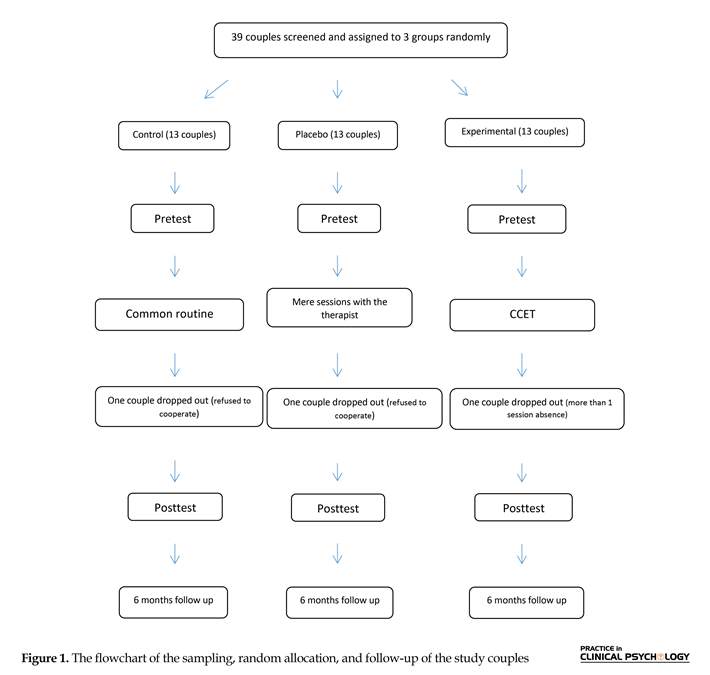

This is a quasi-experimental study with pre-test, post-test and six months follow-up with the experimental, placebo and control groups. The statistical population included all couples attending the court of Shahr-e Kord City, Iran due to marital problems and referred to the counseling centers to reconcile in the spring of 2017. Thirty-nine couples were selected by convenience sampling method and randomly assigned to either the experimental group (13 couples), placebo group (13 couples) or control group (13 couples). Before the study ended, 2 couples due to discontinuation of the research and one couple because of more than one session absence from the training, were excluded from the study. The final analysis was performed on 36 couples.

The couples’ inclusion criteria were the age ranging from 20 to 50 years, having at least a diploma, passing at least one year of married life, working of at least one of them, living together and concurrent attending in counseling sessions, having no addiction or alcoholic spouse, lacking any serious illness or a chronic mental disorder or family acute crisis. The exclusion criteria included disinterest in continuing research, more than one session absence in training, participation in other psychotherapy and concurrent psychological training within the period between the pre-test and six months follow up.

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) was prepared by Spanier (1976) to assess the adjustment between partners or any two people who live together. It has 32 items with two objectives. First, to obtain a total score to reflect overall satisfaction in an intimate relationship which ranges between 0 and 151, and the second to measure the four dimensions of the relationship, including satisfaction, mutual correlation, mutual agreement, and expressing kindness. Scoring is based on the Likert-type scale and higher scores represent a better and more consistent relationship. Reliability of the scale calculated with the Cronbach α was obtained 0.96 which represents a good internal consistency.

The internal consistency of subscales range from good to excellent; 0.94 for satisfaction, 0.81 for mutual correlation, 0.90 for mutual agreement, and 0.73 for expressing feelings. In the case of validity, this scale was also checked with logical content validity. Dyadic adjustment scale distinguish between satisfied couples and divorced couples each item has shown its validity for well-known groups. This scale has a concurrent validity and correlates with the Locke-Wallace marital satisfaction scale (Hazrati et al., 2017). In Iran, Hosseinnejad (1995) standardized it using the test-retest interval of 10 days on a sample of 120 couples (60 males and 60 females). Also, the Pearson method was used for calculating the correlation. The correlation coefficients between the scores of couples over twice performance were obtained for overall scale as 0.86, marital satisfaction as 0.68, mutual correlation as 0.75, mutual agreement as .0.71 and scale expressions of feelings as 0.61 (Sanai Zaker, 2009).

Study Intervention for the experimental group was CCET and for the placebo group was only a session with the therapist. In the placebo group, in a group meeting, the couple in the presence of the therapist spoke about the causes of marital problems and the reasons for applying divorce, and during the sessions, no training was given by the therapist. CCET (Bodenmann and Shantiath, 2004) was firstly proposed by Bodenmann (1997), and then was regularly used in prevention programs, including six sectors that the sectors 1 to 4 were the new sectors (stress recognition, individual adjustment improvement, couples’ adjustment improvement and exchange and fairness at relationship), and sections 5 and 6 (relationship and problem solving). It was designed to be similar to other popular programs (for example, prevention programs and strengthening the relationship). According to Bodenmann and Randall (2012), stress and its transfer to marital relationships is a destructive factor in adjustment with a spouse, so both partners must be encouraged to help each other to cope with tensions and engage in a fair attempt to deal with any stressors in marital relations.

In this study, at first, the “Couple Coping With Stress” book by Bodenmann (2005) and also articles and dissertations in Persian and English related to the CCET were studied to devise a therapeutic plan. Then, a graceful form of CCET sessions with cultural norms, values, and Islamic-Iranian beliefs was prepared and formulated, then it was approved by seven experts in psychology and family counseling. The training was carried out by two specialists familiar with the intervention in clinical psychology during 18 hours as nine 2-hour weekly sessions held by lectures, role-playing, and practical activities. The content of the sessions are summarized and presented as follows:

First session: Familiarity of the group members with each other and with the researcher, explanation of purpose, rules, group framework, and general expectations.

Reported by the Iranian Civil Registration Organization, the divorce rate is growing exponentially so that the ratio of divorce in Iran ranged from 4.4 in 2006 to 28.8 in 2014, and in 2015 it reached the 4 to 1 ratio (marriage to divorce ratio), that is, the growth of approximately 24% divorce in Iran (Heshmati, Gharedaghi, Jafari, & Qolizadegan, 2017). On the other hand, let alone marriages ending up in official divorce, many unsatisfied couples decide to keep on their marital life for a variety of reasons, such as financial problems or individual and cultural perspectives about divorce (Sudani, Dastan, Khojastemehr, & Rajabi, 2015).

Marital adjustment of wives, as an important variable in marriage, is a situation where wife and husband feel satisfaction from marriage, relating with each other in a respectful and reciprocal manner, and have collaborative decision-making, effective familial performance, and sexual adjustment (Peterson-Post, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2014; Li, Robustelli, & Whisman, 2016; Salimi, Mohsenzadeh, & Nazari, 2016). Marital adjustment of wives has a special role in the family and marital relationship (Rostami, Abolghasemi, & Narimani, 2016). It is a process in which each member of a couple modifies his or her behavior patterns individually or jointly to achieve maximum marital satisfaction at their relationship. And this entails adapting of their tastes, knowing of personal traits, creating behavioral rules, and formation of relationship patterns (Bali, Dhingra & Baru, 2010).

Marital adjustment of wives includes mutual agreement and satisfaction, and affective expression (Sudani et al., 2015). Mutual agreement refers to how much couples agree on important topics like financial affairs management and making important decisions. Mutual correlation refers to how often both couples are involved in common activities. Affective expression refers to how often couples express love and affection to each other. Finally, mutual satisfaction relates to the amount of happiness in relationships and frequency of conflicts experienced in a relationship (Sanai Zaker, 2009). Moreover, marital adjustment of wives is a systematic approach to the concept of adaptation in the couple’s relationships.

Accordingly, the husband expresses his stress in verbal or non-verbal ways, and his wife responds in three ways: 1. Gets affected (i.e. stress transition occurs); 2. Completely ignores stressor and does not react; and 3. Acts based on one of two positive and negative adaptive behaviors. A stress transfer process involves the adjustment responses of both spouses. Good adjustment is defined as returning to performance before the stressor or optimal marital adjustment is defined as a return to the functions before the stressor (Falconier, Nussbeck, Bodenmann, Schneider, & Bradbury, 2015).

In recent years, according to Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) approach, one of the training programs that has drawn special attention to improve marital adjustment of wives and finally prevention of divorce is the Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) that has been designed based on dyadic coping enrichment model (Bodenmann, 1997) and emphasizes on importance of dyadic coping skills in improving satisfaction with the relationship. It helps couples identify, express, and manage stressful situations, especially situations outside the marital relationship. The interventional techniques in CCET include completing the stress questionnaire, time management training, progressive muscle relaxation, and role-play exercises (Davis & Davis, 2014).

Although, relationship skills and problem solving are repeatedly proposed as the main predictor of marriage quality and sustainability in the common couples’ education (For example, prevention and relationship enhancement program), individual and couple adjustment skills also play an important role in marital quality and sustainability (Bodenmann, Pihet, Shantinath, Cina, & Widmer, 2006). In addition, studies by Bodenmann (2005) and Bodenmann, Ledermann and Bradbury (2007) suggest that a greater number of couples show pre-existing flaws in relationship skills and miss it in stressful situations. Stress can reduce the time of being together, the opportunity to gain common experience, mutual emotional self-disclosure, kindness, sexual relationship satisfaction, and marital quality relationship (Bodenmann, 2005).

In stressful conditions, positive behaviors, including active listening, expressing interest, and empathy between couples decrease and negative behaviors that are high-risk factors for divorce such as criticizing, humiliation, disrespect, hostility, and withdrawal noticeably increases (Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004). A great number of marital relationships will be hurt without the skill of appropriate adjustment with stress. Lack of appropriate adjustment with stress in couples is one of the important causes of high divorce rate (Falconier et al., 2015; Davis & Davis, 2014; Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004). The most damaging variables for adjustment are external mild chronic stressors that spread to sincere relationships. These stressors are the reason of tension, conflict, and alienation between spouses and increase the possibility of divorce (Bodenmann, Meuwly, Bradbury, Gmelch, & Ledermann, 2010).

The couples enrichment Program is associated with the high satisfaction of couples (Bodenmann and Shantinath, 2004). CCET affects individual and dyadic adjustment, couples coping, marital satisfaction, marital quality, conflict resolution styles, effective conversation, and sincere security in couples (Bodenmann, 2000; Bodenmann, & Charvoz, Cina, & Widmer, 2001; Cina, Widmer & Bodenmann, 2002; Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004; Ledermann, Bodenmann & Cina, 2007; Schaer, Bodenmann & Klink, 2008; Ozouni-Davaji, Dadkhah, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, & Dolatshahi, 2012; Marshall, Jones, & Feinberg, 2011; Falconier et al., 2015). Although the effectiveness of the CCET is well supported, most studies in this topic have been conducted in different cultural societies from Iranian culture and are based on different definitions of marital adjustment and family pillars. In addition, these studies have often examined the effectiveness of the CCET on marital relationships. In this study, the cultural tailoring/adaptation of this intervention was performed, and the study focused on marital adjustment and the couple’s compatibility.

Although numerous psychological interventions have been already performed on psycho-social dimensions of marriage health in Iran, no research has been ever done in the field of interventional couples coping enrichment in improving marital adjustment of wives in Iranian samples. The distinguishing feature of CCET is its focus on stress and coping theory in marital relationships. In addition to educating communication skills and problem solving, CCET focuses on the individual and dyadic coping of couples to improve marital satisfaction and reduce emotional distress. This intervention is also suitable for couples with long-lasting maladaptive relationships as well as an appropriate model for avoiding divorce (Bodenmann & Shantiath, 2004; Bodenmann et al., 2006). Another limitation is the lack of cultural tailoring in CCET according to the needs of different populations because interventions will be more effective when reflecting cultural norms, values, and beliefs (Archibald, 2011).

Cultural tailoring or adaptation has been defined as the systematic modification of a treatment or intervention protocol to consider culture, language, and context so that it fits with the cultural patterns, values, and meanings for the target people (Bernal, Jimenez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009). The CCET is a tailored intervention to prevent marital distress or marital maladjustment based on stress and coping in various cultures (Ledermann, et al., 2007). For example, excitement is a prestigious cultural component, but in an Asian culture society with a focus on collectivism, there is a different meaning for excitement than individualist societies. This lack of access and limited emotional expression, in turn, is an important factor in reducing the marital adjustment of wives (Batool & Khalid, 2009). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to study the cultural tailoring and the effectiveness of CCET to improve marital adjustment of wives and answer the fundamental question that is whether CCET based on cultural tailoring is effective on improving marital adjustment of wives in this study.

2. Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with pre-test, post-test and six months follow-up with the experimental, placebo and control groups. The statistical population included all couples attending the court of Shahr-e Kord City, Iran due to marital problems and referred to the counseling centers to reconcile in the spring of 2017. Thirty-nine couples were selected by convenience sampling method and randomly assigned to either the experimental group (13 couples), placebo group (13 couples) or control group (13 couples). Before the study ended, 2 couples due to discontinuation of the research and one couple because of more than one session absence from the training, were excluded from the study. The final analysis was performed on 36 couples.

The couples’ inclusion criteria were the age ranging from 20 to 50 years, having at least a diploma, passing at least one year of married life, working of at least one of them, living together and concurrent attending in counseling sessions, having no addiction or alcoholic spouse, lacking any serious illness or a chronic mental disorder or family acute crisis. The exclusion criteria included disinterest in continuing research, more than one session absence in training, participation in other psychotherapy and concurrent psychological training within the period between the pre-test and six months follow up.

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) was prepared by Spanier (1976) to assess the adjustment between partners or any two people who live together. It has 32 items with two objectives. First, to obtain a total score to reflect overall satisfaction in an intimate relationship which ranges between 0 and 151, and the second to measure the four dimensions of the relationship, including satisfaction, mutual correlation, mutual agreement, and expressing kindness. Scoring is based on the Likert-type scale and higher scores represent a better and more consistent relationship. Reliability of the scale calculated with the Cronbach α was obtained 0.96 which represents a good internal consistency.

The internal consistency of subscales range from good to excellent; 0.94 for satisfaction, 0.81 for mutual correlation, 0.90 for mutual agreement, and 0.73 for expressing feelings. In the case of validity, this scale was also checked with logical content validity. Dyadic adjustment scale distinguish between satisfied couples and divorced couples each item has shown its validity for well-known groups. This scale has a concurrent validity and correlates with the Locke-Wallace marital satisfaction scale (Hazrati et al., 2017). In Iran, Hosseinnejad (1995) standardized it using the test-retest interval of 10 days on a sample of 120 couples (60 males and 60 females). Also, the Pearson method was used for calculating the correlation. The correlation coefficients between the scores of couples over twice performance were obtained for overall scale as 0.86, marital satisfaction as 0.68, mutual correlation as 0.75, mutual agreement as .0.71 and scale expressions of feelings as 0.61 (Sanai Zaker, 2009).

Study Intervention for the experimental group was CCET and for the placebo group was only a session with the therapist. In the placebo group, in a group meeting, the couple in the presence of the therapist spoke about the causes of marital problems and the reasons for applying divorce, and during the sessions, no training was given by the therapist. CCET (Bodenmann and Shantiath, 2004) was firstly proposed by Bodenmann (1997), and then was regularly used in prevention programs, including six sectors that the sectors 1 to 4 were the new sectors (stress recognition, individual adjustment improvement, couples’ adjustment improvement and exchange and fairness at relationship), and sections 5 and 6 (relationship and problem solving). It was designed to be similar to other popular programs (for example, prevention programs and strengthening the relationship). According to Bodenmann and Randall (2012), stress and its transfer to marital relationships is a destructive factor in adjustment with a spouse, so both partners must be encouraged to help each other to cope with tensions and engage in a fair attempt to deal with any stressors in marital relations.

In this study, at first, the “Couple Coping With Stress” book by Bodenmann (2005) and also articles and dissertations in Persian and English related to the CCET were studied to devise a therapeutic plan. Then, a graceful form of CCET sessions with cultural norms, values, and Islamic-Iranian beliefs was prepared and formulated, then it was approved by seven experts in psychology and family counseling. The training was carried out by two specialists familiar with the intervention in clinical psychology during 18 hours as nine 2-hour weekly sessions held by lectures, role-playing, and practical activities. The content of the sessions are summarized and presented as follows:

First session: Familiarity of the group members with each other and with the researcher, explanation of purpose, rules, group framework, and general expectations.

Then, the pre-test and intervention start for the test and placebo groups.

Second session: Enriching the couples’ knowledge about the stress, differentiating between various types of tension, and knowing that stress is the result of the cognitive assessment and the emotional impact of this assessment, and finally the presentation of the task.

Third session: Review the previous session of the task and give feedback, the definition of self-adjustment, types of individual adjustment, the role of planning, organizing activities, predicting situation to prevent stress, presentation of the assignment.

Fourth session: Review of the previous task and give feedback, creating treasury locations, the method of adjustment to non-avoiding stresses, relaxation training, and presentation of the task.

Fifth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, define couples coping, types and methods to identify them, the importance of couple adjustment at marital relationships, the cycle of the stress transfer of couples to each other, providing a task.

Sixth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, training skill couple coping, funnel method at couples coping, a three-level method in couple adjustment, providing an assignment.

Seventh session: Review of the previous task and give feedback, exchange and fairness definition at marital relationships/borders, and borders problems at marital relationships, intimacy, and proximity at marital relationships, presenting assignment.

Eighth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, the importance of marital relationship skills, styles of positive relationship at marital relationship, the skill of being a good speaker-listener, providing a task.

Ninth session: Overview of previous session task and give feedback, improve problem-solving skills: non-avoidance of the problems in marital relationships, the importance of appropriate problem solving, problem-solving steps training, presenting an assignment.

One week after the end of the sessions, the post-test was performed on experimental, placebo and control groups. Six months later, a follow-up assessment was performed for the three groups. In this study, the CCET was initially provided based on theoretical foundations and cultural evidence on marital problems in Iran. Then, the CCET was revised and verified by seven family and couples therapists for Iranian couples. This intervention is suitable for use in Iranian samples because it is an evidence-based model of Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) CCET, reliable, and adapted to our cultural values of marital life, and language.

Administration: Firstly, researchers attend the counseling centers of the Shahr-e Kord Judiciary. In this study, the samples were first selected by convenience sampling method and then they were randomly assigned to three groups. After consulting with the superintendent about the training, it was stipulated that the couples in each group should be selected from a separate counseling center and sessions should be held in the same place to prevent the interference of learning effects among the couples in the three groups.

After sampling, the informed written consent form was completed by the participants and the study was performed based upon research ethical criteria, including confidentiality, protection of participants’ rights, providing comfort at study and possibility of leaving the study in all study stages from any group. The participants at first passed the pre-test and completed the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) and then the intervention was administered to the experimental and placebo groups. The members of the control group continued their normal routine. After the intervention, the post-test and six months later the follow-up test were carried out. The way to run the study is presented in the following flowchart (Figure 1).

Finally, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation), and inferential statistics (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test, Mauchly’s Test of sphericity, and repeated measures analysis of Variance) in SPSS V. 21.

3. Results

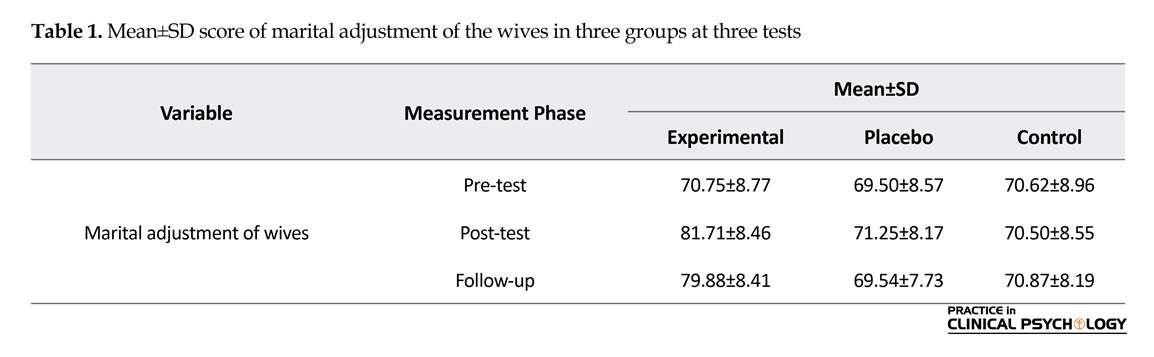

The participants were 20 to 50 years old with a Mean age of 30.78 years (SD=5.20) and Mean marriage duration of 7.3 years (SD=5.42). Regarding the educational status, 51 (70%) subjects had a diploma, 7 (10%) an associate’s degree and 14 (20%) a bachelor’s degree. In terms of occupation, 32 (44%) participants were unemployed and housewives, 34 (48%) were self-employed and 6 (8%) had a governmental job. In terms of within-group factors, there were pre-test, post-test and six months follow-up scores, and in terms of between-group factors, there were three groups of experimental, placebo and control with 12 couples in each (Table 1).

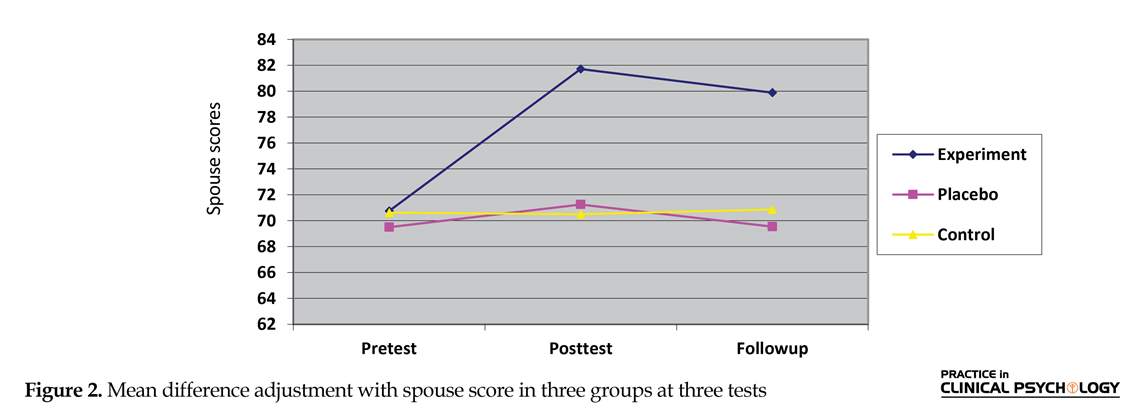

Table 1 shows that mean scores in adjustment with the wives has a significant change at the experimental group in the post-test (81.71) and follow-up (79.88) compared to the pre-test (70.75), while the mean scores of placebo and control groups at three stages have no significant differences. In addition, Figure 2 indicates mean difference in adjustment with the wives in three groups on pre-test, post-test and follows up.

Second session: Enriching the couples’ knowledge about the stress, differentiating between various types of tension, and knowing that stress is the result of the cognitive assessment and the emotional impact of this assessment, and finally the presentation of the task.

Third session: Review the previous session of the task and give feedback, the definition of self-adjustment, types of individual adjustment, the role of planning, organizing activities, predicting situation to prevent stress, presentation of the assignment.

Fourth session: Review of the previous task and give feedback, creating treasury locations, the method of adjustment to non-avoiding stresses, relaxation training, and presentation of the task.

Fifth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, define couples coping, types and methods to identify them, the importance of couple adjustment at marital relationships, the cycle of the stress transfer of couples to each other, providing a task.

Sixth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, training skill couple coping, funnel method at couples coping, a three-level method in couple adjustment, providing an assignment.

Seventh session: Review of the previous task and give feedback, exchange and fairness definition at marital relationships/borders, and borders problems at marital relationships, intimacy, and proximity at marital relationships, presenting assignment.

Eighth session: Review of the previous session of the task and give feedback, the importance of marital relationship skills, styles of positive relationship at marital relationship, the skill of being a good speaker-listener, providing a task.

Ninth session: Overview of previous session task and give feedback, improve problem-solving skills: non-avoidance of the problems in marital relationships, the importance of appropriate problem solving, problem-solving steps training, presenting an assignment.

One week after the end of the sessions, the post-test was performed on experimental, placebo and control groups. Six months later, a follow-up assessment was performed for the three groups. In this study, the CCET was initially provided based on theoretical foundations and cultural evidence on marital problems in Iran. Then, the CCET was revised and verified by seven family and couples therapists for Iranian couples. This intervention is suitable for use in Iranian samples because it is an evidence-based model of Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) CCET, reliable, and adapted to our cultural values of marital life, and language.

Administration: Firstly, researchers attend the counseling centers of the Shahr-e Kord Judiciary. In this study, the samples were first selected by convenience sampling method and then they were randomly assigned to three groups. After consulting with the superintendent about the training, it was stipulated that the couples in each group should be selected from a separate counseling center and sessions should be held in the same place to prevent the interference of learning effects among the couples in the three groups.

After sampling, the informed written consent form was completed by the participants and the study was performed based upon research ethical criteria, including confidentiality, protection of participants’ rights, providing comfort at study and possibility of leaving the study in all study stages from any group. The participants at first passed the pre-test and completed the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) and then the intervention was administered to the experimental and placebo groups. The members of the control group continued their normal routine. After the intervention, the post-test and six months later the follow-up test were carried out. The way to run the study is presented in the following flowchart (Figure 1).

Finally, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation), and inferential statistics (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test, Mauchly’s Test of sphericity, and repeated measures analysis of Variance) in SPSS V. 21.

3. Results

The participants were 20 to 50 years old with a Mean age of 30.78 years (SD=5.20) and Mean marriage duration of 7.3 years (SD=5.42). Regarding the educational status, 51 (70%) subjects had a diploma, 7 (10%) an associate’s degree and 14 (20%) a bachelor’s degree. In terms of occupation, 32 (44%) participants were unemployed and housewives, 34 (48%) were self-employed and 6 (8%) had a governmental job. In terms of within-group factors, there were pre-test, post-test and six months follow-up scores, and in terms of between-group factors, there were three groups of experimental, placebo and control with 12 couples in each (Table 1).

Table 1 shows that mean scores in adjustment with the wives has a significant change at the experimental group in the post-test (81.71) and follow-up (79.88) compared to the pre-test (70.75), while the mean scores of placebo and control groups at three stages have no significant differences. In addition, Figure 2 indicates mean difference in adjustment with the wives in three groups on pre-test, post-test and follows up.

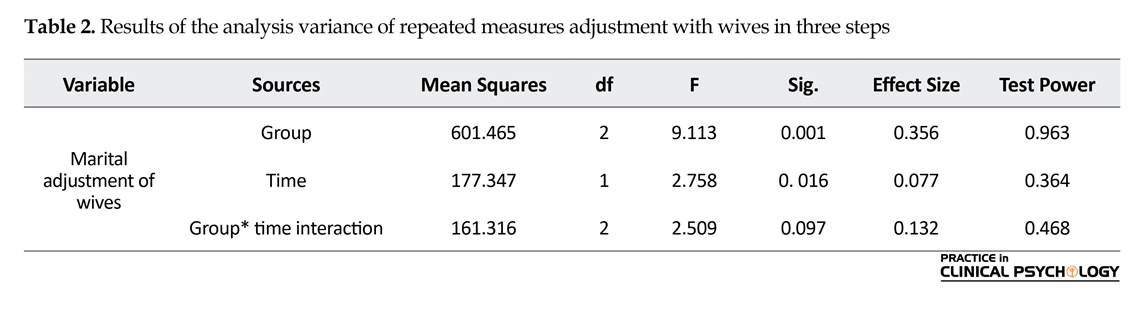

To determine the meaningful difference between the groups in terms of the study variables, the repeated measures ANOVA was used based on the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test and Mauchly’s Test of sphericity. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test results confirmed the normal distribution of the dependent variables at pre-test (0.107), post-test (0.105) and follow-up (0.076). Also, the results of Mauchly’s test of sphericity (0.962) assumes the variance/covariance form of the dependent variable (P=0.540). The results of the Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that the spheroid assumption was established.

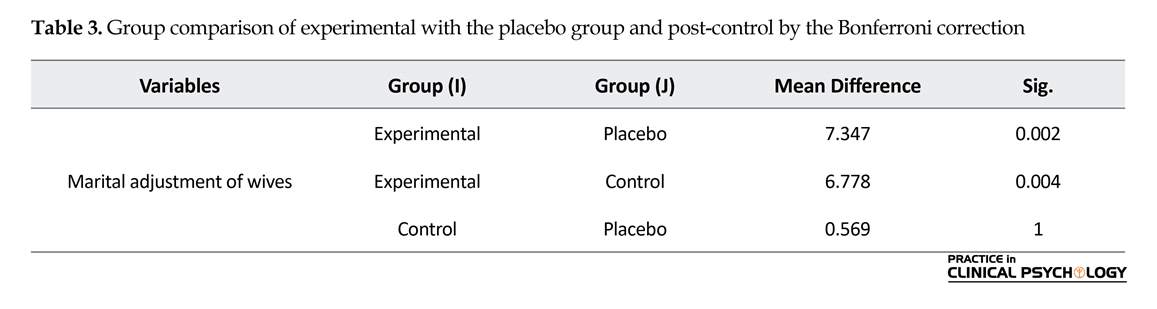

According to Table 2 results, the effects of the group (F=9.113, P<0.001) and time (F=2.758, P<0.016) and group*time interaction (F=2.509, P<0.097) are effective in improving coping with wives. In addition, the effect size observed in the Table 2 shows how the changes occurred at the end of training related to the effectiveness of the couple’s compatibility enrichment and power of statistical test indicates the significance of these effects. Furthermore, paired comparison results of experimental group with placebo group and control after the Bonferroni correction (Table 3) showed a significant difference between the mean scores of the experiment group compared to the placebo and control groups (P<0.002 and P<0.004, respectively). Meanwhile, the average scores of adjustment with the wives of the under-training group have significantly improved with CCET based on cultural tailoring.

4. Discussion

According to our study findings, CCET significantly increased the mean scores of DAS in post-test and six months follow-up in the experiment group. These findings are consistent with previous research findings and confirm the study hypothesis and indicate that CCET can be an effective and sustainable intervention to reduce marital problems. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Falconier et al. (2015), Marshall et al. (2011), as well as Ozouni-Davaji, Dadkhah, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee and Dolatshahi, (2012).

According to Table 2 results, the effects of the group (F=9.113, P<0.001) and time (F=2.758, P<0.016) and group*time interaction (F=2.509, P<0.097) are effective in improving coping with wives. In addition, the effect size observed in the Table 2 shows how the changes occurred at the end of training related to the effectiveness of the couple’s compatibility enrichment and power of statistical test indicates the significance of these effects. Furthermore, paired comparison results of experimental group with placebo group and control after the Bonferroni correction (Table 3) showed a significant difference between the mean scores of the experiment group compared to the placebo and control groups (P<0.002 and P<0.004, respectively). Meanwhile, the average scores of adjustment with the wives of the under-training group have significantly improved with CCET based on cultural tailoring.

4. Discussion

According to our study findings, CCET significantly increased the mean scores of DAS in post-test and six months follow-up in the experiment group. These findings are consistent with previous research findings and confirm the study hypothesis and indicate that CCET can be an effective and sustainable intervention to reduce marital problems. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Falconier et al. (2015), Marshall et al. (2011), as well as Ozouni-Davaji, Dadkhah, Khodabakhshi-Kolaee and Dolatshahi, (2012).

In these studies, CCET or CCET-related interventions resulted in a better marital adjustment of couples, increased their quality of marital relationships and empowered marital coping strategies. In addition, these findings are consistent with the results of the study by Schaer, Bodenmann, and Klink (2008). Self-report data in pre-test, post-test (2 weeks after intervention) and follow-up (6 months after training) showed that CCET enhanced marital adjustment of the couples, empowered them in effective negotiation and increased compromise with the wives. Moreover, the results of this research are consistent with the study results of Bodenmann and Shantinath (2004) and Ying et al. (2017) whose findings indicated that marital satisfaction and effective communication skills increased with implementing CCET.

There are many reasons that group method intervention is beneficial in a special way to improve marital adjustment of wives at this study. In group CCET, partner’s learning from each other about adaptive interaction and joined compromise is an effective strategy to control stress symptoms and improve marital adjustment. Improving marital adjustment of wives is affected by the group compressed intervention sessions because of different couple education and reciprocal interactions in educational sessions. This intervention, as a valuable method for stress management, is a great way to improve marital adjustment. Compromising skills in wives provide an opportunity to decrease stress and increase corrective marital communication in the long term. Also, couples in this study received eight intervention sessions. We can infer that there may be a stronger link among couples and the trainer to facilitate the effectiveness and permanent outcomes of the intervention.

According to the observed effect of culturally tailored CCET in the marital adjustment of wives, this intervention has higher and longer effects compared with the similar studies on interventions in marital adjustment. To explain this result, it can be said that education and enriched marital adjustment in CCET is based on stress management as stress is a main negative factor in marital discord. In addition, as Bodenmann (2005) previously argued, we can say that stress in one of the main sources of marital conflict of couples. Landis, Peter-Wight, Martin nad Bodenman (2013) argued that enrichment and skill training for stress management resulted in the higher quality of couples’ coping with stress, decreased negative effects of stress on marital interactions and marital adjustment of wives.

However, with regard to the small sample and quasi-experimental design of this study, we cannot generalize the results of this intervention to other samples and statistical populations. It is suggested that in future studies researchers use additional sessions or more CCET training to extend intervention or the period of treatment and follow-up sessions for testing results generalizability.

Our results indicate that CCET based on cultural tailoring can improve the marital adjustment of wives in a sample of troubled couples referring to Judiciary Office of Shahr-e Kord City, Iran in 6 months period. This research has some limitations, too. Its convenience sampling method, restricted research population, self-report instrument, and lack of qualitative assessments are the most important limitations of this study. So, it is recommended that this intervention in quantitative and qualitative research designs be conducted in other communities with random sampling method and more sample size. In addition, it can be suggested that the effect of this intervention be compared with other couple therapy interventions to determine how effective CCET based on cultural tailoring is. The results of this study have implications for marriage counseling and treatment centers, family counselors and psychotherapists, and divorce prevention and reduction centers. Providing educational brochures, booklets, books and educational videos based on CCET therapeutic approach is suggested, too.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

The present paper was extracted from the PhD. dissertation of the Mahdi Omidian in Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Methodology: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Investigation: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Manijeh Kaveh; Writing-original draft: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar; Writing-review & editing: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; Funding acquisition: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar; Resources: Mahdi Omidian, Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh; and Supervision: Isaac Rahimian Boogar, Siavash Talepasand, Mahmoud Najafi, Manijeh Kaveh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Semnan University Graduate Education.

References

- Archibald, C. (2011). Cultural Tailoring for an afro-caribbean community: A naturalistic approach. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 18(4), 114-9. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bali, A., Dhingra, R., & Baru, A. (2010). Marital adjustment of childless couples. Journal of Social Science, 24(1), 73-6. [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892839]

- Batool, S. S., & Khalid, R. (2009). Role of emotional intelligence in marital relationship. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 24(1), 43-62.

- Bernal, G., Jimenez-Chafey, M. I., Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361-8. [DOI:10.1037/a0016401]

- Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping - a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée, 47(2), 137-40.

- Bodenmann, G. (2000b). [The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevent marital distress based upon stress and coping (German)]. Family Relations, 53(5), 477-84. [PMID]

- Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Decade of Behavior. Couples Coping With Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping (pp. 33-49). Washington: American Psychological Association. [DOI:10.1037/11031-002] [PMID]

- Bodenmann, G., & Randall, A. K. (2012). Common factors in the enhancement of dyadic coping. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 88-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.003]

- Bodenmann, G., & Shantinath, S. D. (2004). The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations, 53(5), 477-84. [DOI:10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00056.x]

- Bodenmann, G., Charvoz, L., Cina, A., & Widmer, K. (2001). Prevention of marital distress by enhancing the coping skills of couples: 1-year follow-up-study. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 60(1), 3-10. [DOI:10.1024//1421-0185.60.1.3]

- Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., & Bradbury T. N. (2007). Stress, sex and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships, 14(4), 551-60. [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x]

- Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Bradbury, T. N., Gmelch, S., & Ledermann, T. (2010). Stress and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: Moderating effects of trait anger and dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 408-24. [DOI:10.1177/0265407510361616]

- Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., Shantinath, S. D., Cina, A., & Widmer K. (2006). Improving dyadic coping in couples with a stress-oriented approach: A 2-year longitudinal study. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 571-97. [DOI:10.1177/0145445504269902] [PMID]

- Cina, A., Widmer, K., & Bodenmann, G. (2002). [The effectiveness of the Couples' Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A comparison of two training versions (German)]. Verhaltenstherapie, 12(1), 36-45. [DOI:10.1159/000056691]

- Davis, K. R., & Davis, J. R. (2014). Enhancing relationships through coping skills and sleep health education: literature review and research proposal. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 4(2), 24-33.

- Falconier, M. K., Nussbeck, F., Bodenmann, G., Schneider, H., & Bradbury, T. (2015). Stress from daily hassles in couples: Its effects on intradyadic stress, relationship satisfaction, and physical and psychological well-being. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(2), 221-35. [DOI:10.1111/jmft.12073]

- Hazrati, M., Hamid, T. A., Ibrahim, R., Hassan, S. A., Sharif, F., & Bagheri, Z. (2017). The effect of emotional focused intervention on spousal emotional abuse and marital satisfaction among elderly married couples: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 5(4), 329-34. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heshmati, R., Gharadaghi, A., Jafari, E., & Gholizadehgan, M. (2017). [Prediction of marital burnout in couples seeking divorce with knowledge of demographic characteristics, mindfulness, and emotional resilience (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 7(1), 1-22.

- Hoseinnejad, M. (1995). [Study of rate of incompatibility among parents with mentally retarded children (Persian)] [MA. thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabatabaee University.

- Landis, M., Peter-Wight, M., Martin, M., & Bodenman, G. (2013). Dyadic coping and marital satisfaction of older spouses in long-term marriage. The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry , 26(1), 39-47. [DOI:10.1024/1662-9647/a000077]

- Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., & Cina, A. (2007). The efficacy of the Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) in improving relationship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(8),940-59. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.8.940]

- Li, A., Robustelli, B. L., & Whisman, M. A. (2016). Marital adjustment and psychological distress in Japan. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(7), 855-66. [DOI:10.1177/0265407515599678] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Marshall, A. D., Jones, D. E., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: an integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 709-18. [DOI:10.1037/a0025279]

- Ozouni-Davaji, R. B., Dadkhah, A., Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, A., & Dolatshahi, B. (2012). [The effectiveness of group training of couples coping skills enhancement on marital relationships quality in distressed couples (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 25-30.

- Peterson-Post, K. M., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2014). Perceived criticism and marital adjustment predict depressive symptoms in a community sample. Behavior Therapy, 45(4), 564-75. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rostami, M., Abolqasemi, A., & Narimani, M. (2016). [The effectiveness of treatment based on quality improvement Life on the psychological well-being of couples (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 3(1), 105-23.

- Salimi, H., Mohsenzadeh, F., & Nazari, A. M. (2016). [Prediction of marital adjustment based on family solidarity, time for togetherness and financial sources in female teachers (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Woman & Society, 7(27), 175-92.

- Sanai Zaker, B. (2009). [Family and Marriage Measurement Scales (Persian)]. Tehran: Be'sat Publication.

- Schaer, M., Bodenmann, G., & Klink, T. (2008). Balancing work and relationship: Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) in the workplace. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 71-89. [DOI:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00355.x]

- Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15-28. [DOI:10.2307/350547]

- Sudani, M., Dastan, N., Khojastemehr, R., & Rajabi, R. (2015). [Comparing the effectiveness of narrative couple therapy and integrative behavior couple therapy on conflict solv-ing tactics of female victims of violence (Persian)]. Journal of Women and society, 6(3), 1-12.

- Ying, L., Chen, X., Wu, L. H., Shu, J., Wu, X., & Loke, A. Y. (2017). The partnership and coping enhancement programme for couples undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment: the development of a complex intervention in China. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 34(1), 99-108. [DOI:10.1007/s10815-016-0817-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2018/05/25 | Accepted: 2018/11/14 | Published: 2019/01/1

Received: 2018/05/25 | Accepted: 2018/11/14 | Published: 2019/01/1

References

1. Archibald, C. (2011). Cultural Tailoring for an afro-caribbean community: A naturalistic approach. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 18(4), 114-9. [PMID] [PMCID] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Bali, A., Dhingra, R., & Baru, A. (2010). Marital adjustment of childless couples. Journal of Social Science, 24(1), 73-6. [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892839] [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892839]

3. Batool, S. S., & Khalid, R. (2009). Role of emotional intelligence in marital relationship. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 24(1), 43-62.

4. Bernal, G., Jimenez-Chafey, M. I., Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361-8. [DOI:10.1037/a0016401] [DOI:10.1037/a0016401]

5. Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping - a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée, 47(2), 137-40.

6. Bodenmann, G. (2000b). [The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevent marital distress based upon stress and coping (German)]. Family Relations, 53(5), 477-84. [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00056.x]

7. Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Decade of Behavior. Couples Coping With Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping (pp. 33-49). Washington: American Psychological Association. [DOI:10.1037/11031-002] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/11031-002]

8. Bodenmann, G., & Randall, A. K. (2012). Common factors in the enhancement of dyadic coping. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 88-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.003] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.003]

9. Bodenmann, G., & Shantinath, S. D. (2004). The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations, 53(5), 477-84. [DOI:10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00056.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00056.x]

10. Bodenmann, G., Charvoz, L., Cina, A., & Widmer, K. (2001). Prevention of marital distress by enhancing the coping skills of couples: 1-year follow-up-study. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 60(1), 3-10. [DOI:10.1024//1421-0185.60.1.3] [DOI:10.1024//1421-0185.60.1.3]

11. Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., & Bradbury T. N. (2007). Stress, sex and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships, 14(4), 551-60. [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x]

12. Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Bradbury, T. N., Gmelch, S., & Ledermann, T. (2010). Stress and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: Moderating effects of trait anger and dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 408-24. [DOI:10.1177/0265407510361616] [DOI:10.1177/0265407510361616]

13. Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., Shantinath, S. D., Cina, A., & Widmer K. (2006). Improving dyadic coping in couples with a stress-oriented approach: A 2-year longitudinal study. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 571-97. [DOI:10.1177/0145445504269902] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/0145445504269902]

14. Cina, A., Widmer, K., & Bodenmann, G. (2002). [The effectiveness of the Couples' Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A comparison of two training versions (German)]. Verhaltenstherapie, 12(1), 36-45. [DOI:10.1159/000056691] [DOI:10.1159/000056691]

15. Davis, K. R., & Davis, J. R. (2014). Enhancing relationships through coping skills and sleep health education: literature review and research proposal. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 4(2), 24-33.

16. Falconier, M. K., Nussbeck, F., Bodenmann, G., Schneider, H., & Bradbury, T. (2015). Stress from daily hassles in couples: Its effects on intradyadic stress, relationship satisfaction, and physical and psychological well-being. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(2), 221-35. [DOI:10.1111/jmft.12073] [DOI:10.1111/jmft.12073]

17. Hazrati, M., Hamid, T. A., Ibrahim, R., Hassan, S. A., Sharif, F., & Bagheri, Z. (2017). The effect of emotional focused intervention on spousal emotional abuse and marital satisfaction among elderly married couples: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 5(4), 329-34. [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Heshmati, R., Gharadaghi, A., Jafari, E., & Gholizadehgan, M. (2017). [Prediction of marital burnout in couples seeking divorce with knowledge of demographic characteristics, mindfulness, and emotional resilience (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 7(1), 1-22.

19. Hoseinnejad, M. (1995). [Study of rate of incompatibility among parents with mentally retarded children (Persian)] [MA. thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabatabaee University.

20. Landis, M., Peter-Wight, M., Martin, M., & Bodenman, G. (2013). Dyadic coping and marital satisfaction of older spouses in long-term marriage. The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry , 26(1), 39-47. [DOI:10.1024/1662-9647/a000077] [DOI:10.1024/1662-9647/a000077]

21. Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., & Cina, A. (2007). The efficacy of the Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) in improving relationship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(8),940-59. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.8.940] [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.8.940]

22. Li, A., Robustelli, B. L., & Whisman, M. A. (2016). Marital adjustment and psychological distress in Japan. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(7), 855-66. [DOI:10.1177/0265407515599678] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1177/0265407515599678]

23. Marshall, A. D., Jones, D. E., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: an integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 709-18. [DOI:10.1037/a0025279] [DOI:10.1037/a0025279]

24. Ozouni-Davaji, R. B., Dadkhah, A., Khodabakhshi-Kolaee, A., & Dolatshahi, B. (2012). [The effectiveness of group training of couples coping skills enhancement on marital relationships quality in distressed couples (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 25-30.

25. Peterson-Post, K. M., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2014). Perceived criticism and marital adjustment predict depressive symptoms in a community sample. Behavior Therapy, 45(4), 564-75. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.002] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.002]

26. Rostami, M., Abolqasemi, A., & Narimani, M. (2016). [The effectiveness of treatment based on quality improvement Life on the psychological well-being of couples (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 3(1), 105-23.

27. Salimi, H., Mohsenzadeh, F., & Nazari, A. M. (2016). [Prediction of marital adjustment based on family solidarity, time for togetherness and financial sources in female teachers (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Woman & Society, 7(27), 175-92.

28. Sanai Zaker, B. (2009). [Family and Marriage Measurement Scales (Persian)]. Tehran: Be'sat Publication.

29. Schaer, M., Bodenmann, G., & Klink, T. (2008). Balancing work and relationship: Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) in the workplace. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 71-89. [DOI:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00355.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00355.x]

30. Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15-28. [DOI:10.2307/350547] [DOI:10.2307/350547]

31. Sudani, M., Dastan, N., Khojastemehr, R., & Rajabi, R. (2015). [Comparing the effectiveness of narrative couple therapy and integrative behavior couple therapy on conflict solv-ing tactics of female victims of violence (Persian)]. Journal of Women and society, 6(3), 1-12.

32. Ying, L., Chen, X., Wu, L. H., Shu, J., Wu, X., & Loke, A. Y. (2017). The partnership and coping enhancement programme for couples undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment: the development of a complex intervention in China. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 34(1), 99-108. [DOI:10.1007/s10815-016-0817-y] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s10815-016-0817-y]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |