Volume 6, Issue 4 (Autumn 2018)

PCP 2018, 6(4): 231-238 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Asadpour E, Sadat Hosseini M. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Group Therapy on Self-efficacy and Depression Among Divorced Women. PCP 2018; 6 (4) :231-238

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-535-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-535-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. , dr.iasadpour@yahoo.com

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 652 kb]

(3257 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8137 Views)

Full-Text: (3782 Views)

1. Introduction

Couples’ relationship dissolution is one of the most common family-related damages. Approximately half of all marriages end in divorce. About 65% of women and 70% of men are likely to remarry after divorce, but about 50% of their second marriages also end in divorce (Ricca et al., 2010). Goldberg believes that divorce is the most important predicting factor for pressure and mental disorders in individuals, followed by the loss of family members (Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2012). Although both spouses suffer from the negative consequences of divorce, post-divorce vulnerability is higher in women (Gähler, 2006).

Mental health and quality of life decline after divorce. The major negative consequences of divorce can be psychological disorders, especially stress, leading to depression and reduced self-efficiency, and declined trust in divorced individual’s abilities to achieve their goals (Brown, Sanchez, Nock, & Wright, 2006). Lavelle and Smock (2012) studies showed that divorced women undergo a high level of depression. They also, found that women’s quality of life declines more than men after divorce (Bourassa, Sbarra, & Whisman, 2015).

Most of the time, divorce leads to a decrease in women’s social relations. Reduced mental and physical health diminishes individual’s ability to exercise and perform physical activities, which in return, affects their self-efficacy (Wu, Tang, & Kwok, 2004). Self-efficacy refers to individuals’ judgment about their abilities of performing tasks successfully. Self-efficacy beliefs determine how ready people are to put efforts in reaching their goals and how resistant they are in facing adversity and obstacles (Riso, du Toit, Stein, & Young, 2007).

Considering the above-mentioned points, divorced women undergo a lot of mental stress. As a result, their socio-psychological adaptation is highly dependent on their self-concept. A positive self-concept (an important factor in self-efficacy) in women, leads to confidence and a sense of security, while a negative and unstable self-esteem develops senses of insecurity and unworthiness and disrupts women’s individual and social adaptation (Perry, 2014).

The use of effective techniques with empirical support is required to achieve this goal. This study applied cognitive group therapy methods to reduce depression and enhance self-efficacy among divorced females. In this approach, cognitive techniques aim to identify and challenge irrational thoughts and find alternative methods to replace those with realistic thinking (Hamid, Boshlideh, Eidibeigi, & Dehghanizadeh, 2012). In order to substitute realistic thinking with defined cognitions, the negative thoughts and cognitions are identified, the link between cognition, emotion and behavior is determined and the counter-evidence of automatic thoughts are examined (Nazari & Asadi, 2011).

Cognitive group therapy model is based on a theory that focuses on interactions between thoughts, feelings and behaviors. The most direct method to change ineffective emotions and behaviors is to rectify the wrong and inefficient thinking. To change our feelings about events, we need to change our thinking (Corey, 1995).

The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy and cognitive-behavioral group therapy has been shown in different studies examining depression treatments (Okumura & Chicora, 2014; Taheri & Jamshidifar, 2007; Nazari & Asadi, 2011; McEvoy, Nathan, Rupee, & Campbell 2012; Aghaei, Samkhaniyan, Mahdavi, Faraji, & Roshandel, 2012; Taylor & Montgomery, 2015; Henkel et al., 2010; Vázquez et al., 2012).

According to studies, awareness-based cognitive therapy significantly reduces depression in divorced women (Pajares & Valiante, 2002). Researchers also found that religious cognitive behavioral therapy affects depression in divorced women. Employing metaphors in cognitive behavioral therapy positively affects depression and resistance among divorced females (Hamid et al., 2012; Schatz, Madhavan, & Williams, 2011). The results indicate that cognitive-behavioral approach training also reduces stress and improves mental health of divorced females (Ghamari Kivi, Rezaii Sharif, & Esmaeli Ghazi Valoii, 2016). Considering the importance and necessity of research in divorced women and the limited research available in this area, this research aimed to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on self-efficacy and depression in divorced women.

2. Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with pretest-posttest and control group design. The statistical population included all divorced women supported by Hazrat Zeinab Charity in Varamin City, Iran, in 2016. Thirty women with severe depression and low self-efficacy were randomly selected and assigned into experimental and control groups (15 subjects in each group). Furthermore, none of the subjects were divorced for more than 5 years. A 12-sesion weekly cognitive group therapy was provided for the experimental group, but the control group was placed on the waiting list. The obtained data were analyzed by Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). The measurement tools included:

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was developed by Beck and colleagues in 1961. It is a 21-item self-rating scale, rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not) to 3 (severe). BDI is a relevant psychometric instrument, showing high reliability, capacity to discriminate between depressed and non-depressed subjects, and improved concurrent, content, and construct validity. Studies on BDI reported an average alpha coefficient around 0.9, ranging from 0.83 to 0.96 (Beck, Steer, Ball & Ranieri, 1996).

The internal consistency of this inventory was around 0.9 and the retest reliability ranged from 0.73 to 0.96. The convergent validity between the BDI and other related scales was significant, with a wide range of correlation coefficients (0.37 to 0.83; rough estimate of 0.50) (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). Concerning discriminant validity, studies have indicated low correlation (r<0.4) with other related instruments (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). The internal consistency coefficient and the reliability coefficient of this measurement were reported by Pourshahbaz as 0.85 and 0.81, respectively, in the Iranian population (Pourshahbaz, 1994). The reliability of BDI, based on Cronbach’s alpha calculation, was 0.90 in the present study.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) has 17 items and was designed by Sheer and colleagues to measure general self-efficacy and is rated on a 5-point scale. Total scores are ranged between 17 and 85 (Sherer et al., 1982). Sheer et al. reported its reliability coefficient as 0.86. But the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of GSE was reported 0.84. In a research by Nilsson, Hagell and Iwarsson (2015), the internal consistency (coefficient alpha) was calculated as 0.95. Also, analyses of test-retest reliability yielded (ICC) values from 0.69 to 0.80.

Berati (1997) calculated the reliability of this scale as 0.76 in Iran, and its correlation with Sheer’s self-esteem scale (1982) was reported as 0.61. Keramati (2001) and Majidian (2005) reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.85, 0.86 and 0.78, respectively. In this study Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83. This validity has been calculated based on student samples. Treatment plan: Session instructions were designed on the basis of Michael Fee’s cognitive group therapy, Albert Ellis’s rational-emotional and behavioral theory, and Aaron T Beck’s viewpoints and Young’s schema therapy. A summary of The 12-session intervention is presented in Table 1.

3. Results

The results presented in Table 1 suggest that the data are properly distributed and pretest and posttest scores of the control group are different. In order to ensure conformity with covariance analysis assumptions, Box’s M test, Pillai’s Trace test and Levene’s test, were conducted. These tests showed that the observed covariance matrices of the dependent variables are equal across the groups (P>0.05), therefore the homogeneity of variance/covariance matrices assumption, as well as the variance equation condition were all met.

Couples’ relationship dissolution is one of the most common family-related damages. Approximately half of all marriages end in divorce. About 65% of women and 70% of men are likely to remarry after divorce, but about 50% of their second marriages also end in divorce (Ricca et al., 2010). Goldberg believes that divorce is the most important predicting factor for pressure and mental disorders in individuals, followed by the loss of family members (Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2012). Although both spouses suffer from the negative consequences of divorce, post-divorce vulnerability is higher in women (Gähler, 2006).

Mental health and quality of life decline after divorce. The major negative consequences of divorce can be psychological disorders, especially stress, leading to depression and reduced self-efficiency, and declined trust in divorced individual’s abilities to achieve their goals (Brown, Sanchez, Nock, & Wright, 2006). Lavelle and Smock (2012) studies showed that divorced women undergo a high level of depression. They also, found that women’s quality of life declines more than men after divorce (Bourassa, Sbarra, & Whisman, 2015).

Most of the time, divorce leads to a decrease in women’s social relations. Reduced mental and physical health diminishes individual’s ability to exercise and perform physical activities, which in return, affects their self-efficacy (Wu, Tang, & Kwok, 2004). Self-efficacy refers to individuals’ judgment about their abilities of performing tasks successfully. Self-efficacy beliefs determine how ready people are to put efforts in reaching their goals and how resistant they are in facing adversity and obstacles (Riso, du Toit, Stein, & Young, 2007).

Considering the above-mentioned points, divorced women undergo a lot of mental stress. As a result, their socio-psychological adaptation is highly dependent on their self-concept. A positive self-concept (an important factor in self-efficacy) in women, leads to confidence and a sense of security, while a negative and unstable self-esteem develops senses of insecurity and unworthiness and disrupts women’s individual and social adaptation (Perry, 2014).

The use of effective techniques with empirical support is required to achieve this goal. This study applied cognitive group therapy methods to reduce depression and enhance self-efficacy among divorced females. In this approach, cognitive techniques aim to identify and challenge irrational thoughts and find alternative methods to replace those with realistic thinking (Hamid, Boshlideh, Eidibeigi, & Dehghanizadeh, 2012). In order to substitute realistic thinking with defined cognitions, the negative thoughts and cognitions are identified, the link between cognition, emotion and behavior is determined and the counter-evidence of automatic thoughts are examined (Nazari & Asadi, 2011).

Cognitive group therapy model is based on a theory that focuses on interactions between thoughts, feelings and behaviors. The most direct method to change ineffective emotions and behaviors is to rectify the wrong and inefficient thinking. To change our feelings about events, we need to change our thinking (Corey, 1995).

The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy and cognitive-behavioral group therapy has been shown in different studies examining depression treatments (Okumura & Chicora, 2014; Taheri & Jamshidifar, 2007; Nazari & Asadi, 2011; McEvoy, Nathan, Rupee, & Campbell 2012; Aghaei, Samkhaniyan, Mahdavi, Faraji, & Roshandel, 2012; Taylor & Montgomery, 2015; Henkel et al., 2010; Vázquez et al., 2012).

According to studies, awareness-based cognitive therapy significantly reduces depression in divorced women (Pajares & Valiante, 2002). Researchers also found that religious cognitive behavioral therapy affects depression in divorced women. Employing metaphors in cognitive behavioral therapy positively affects depression and resistance among divorced females (Hamid et al., 2012; Schatz, Madhavan, & Williams, 2011). The results indicate that cognitive-behavioral approach training also reduces stress and improves mental health of divorced females (Ghamari Kivi, Rezaii Sharif, & Esmaeli Ghazi Valoii, 2016). Considering the importance and necessity of research in divorced women and the limited research available in this area, this research aimed to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on self-efficacy and depression in divorced women.

2. Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with pretest-posttest and control group design. The statistical population included all divorced women supported by Hazrat Zeinab Charity in Varamin City, Iran, in 2016. Thirty women with severe depression and low self-efficacy were randomly selected and assigned into experimental and control groups (15 subjects in each group). Furthermore, none of the subjects were divorced for more than 5 years. A 12-sesion weekly cognitive group therapy was provided for the experimental group, but the control group was placed on the waiting list. The obtained data were analyzed by Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA). The measurement tools included:

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was developed by Beck and colleagues in 1961. It is a 21-item self-rating scale, rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not) to 3 (severe). BDI is a relevant psychometric instrument, showing high reliability, capacity to discriminate between depressed and non-depressed subjects, and improved concurrent, content, and construct validity. Studies on BDI reported an average alpha coefficient around 0.9, ranging from 0.83 to 0.96 (Beck, Steer, Ball & Ranieri, 1996).

The internal consistency of this inventory was around 0.9 and the retest reliability ranged from 0.73 to 0.96. The convergent validity between the BDI and other related scales was significant, with a wide range of correlation coefficients (0.37 to 0.83; rough estimate of 0.50) (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). Concerning discriminant validity, studies have indicated low correlation (r<0.4) with other related instruments (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). The internal consistency coefficient and the reliability coefficient of this measurement were reported by Pourshahbaz as 0.85 and 0.81, respectively, in the Iranian population (Pourshahbaz, 1994). The reliability of BDI, based on Cronbach’s alpha calculation, was 0.90 in the present study.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) has 17 items and was designed by Sheer and colleagues to measure general self-efficacy and is rated on a 5-point scale. Total scores are ranged between 17 and 85 (Sherer et al., 1982). Sheer et al. reported its reliability coefficient as 0.86. But the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of GSE was reported 0.84. In a research by Nilsson, Hagell and Iwarsson (2015), the internal consistency (coefficient alpha) was calculated as 0.95. Also, analyses of test-retest reliability yielded (ICC) values from 0.69 to 0.80.

Berati (1997) calculated the reliability of this scale as 0.76 in Iran, and its correlation with Sheer’s self-esteem scale (1982) was reported as 0.61. Keramati (2001) and Majidian (2005) reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.85, 0.86 and 0.78, respectively. In this study Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83. This validity has been calculated based on student samples. Treatment plan: Session instructions were designed on the basis of Michael Fee’s cognitive group therapy, Albert Ellis’s rational-emotional and behavioral theory, and Aaron T Beck’s viewpoints and Young’s schema therapy. A summary of The 12-session intervention is presented in Table 1.

3. Results

The results presented in Table 1 suggest that the data are properly distributed and pretest and posttest scores of the control group are different. In order to ensure conformity with covariance analysis assumptions, Box’s M test, Pillai’s Trace test and Levene’s test, were conducted. These tests showed that the observed covariance matrices of the dependent variables are equal across the groups (P>0.05), therefore the homogeneity of variance/covariance matrices assumption, as well as the variance equation condition were all met.

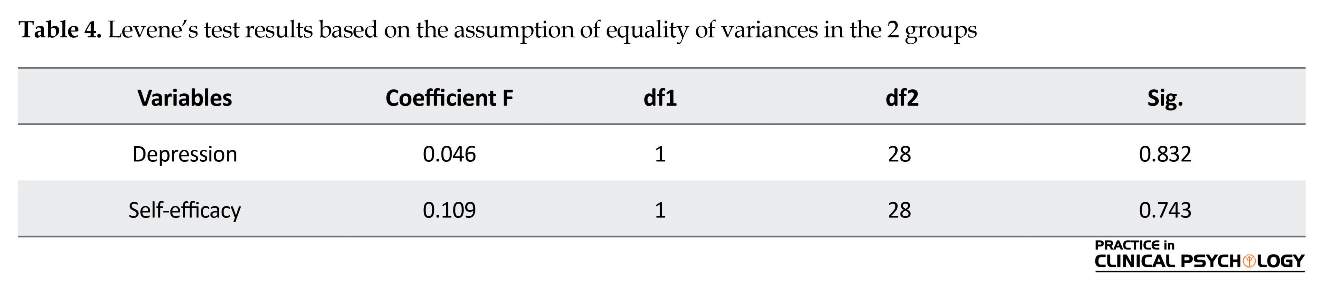

The Levene’s test was used to check the homogeneity of error or homogeneity of variance covariance matrices. Table 2 shows that the variation error of variables in the studied groups is homogeneous, because the calculated F is not significant at P<0.05 level. Bonferroni test was used to compare the mean of depression and self-efficacy scales. The results showed that cognitive group therapy (intervention) significantly improved depression and self-efficacy among divorced women. Depression and self-efficacy were significantly different with the mean difference of 3.28 and 3.19 respectively at the significant level of P<0.01. Cognitive group therapy affect the depression of divorced women supported by Hazrat Zaynab Charity in Varamin City, Iran.

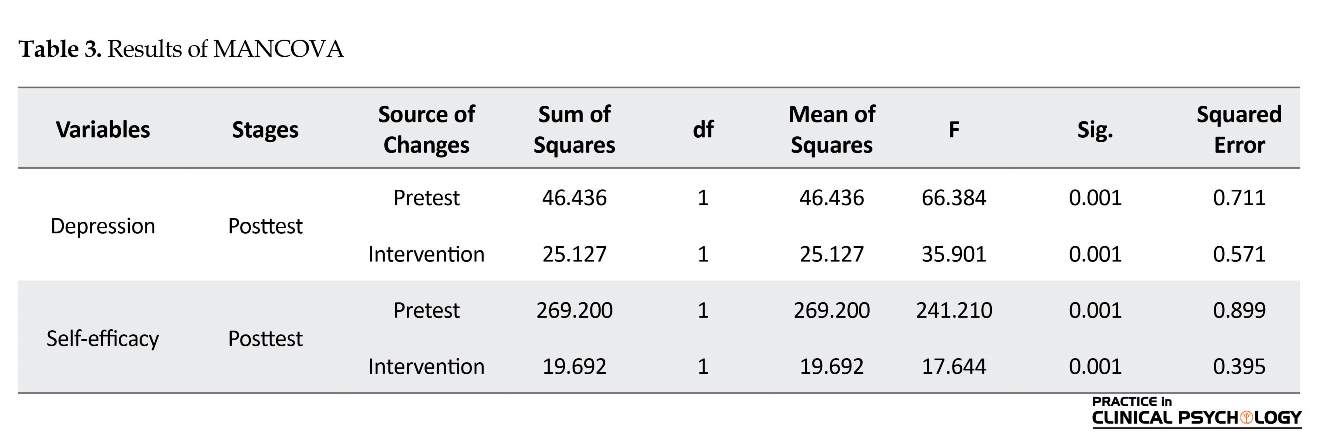

Table 3 indicates that after modifying the pretest scores in the variable of depression, the difference between the control and experimental groups was significant at the significant level of P<0.001. Therefore, cognitive group therapy decreases depression in the experimental group

Table 3 indicates that after modifying the pretest scores in the variable of depression, the difference between the control and experimental groups was significant at the significant level of P<0.001. Therefore, cognitive group therapy decreases depression in the experimental group

compared to the control group. In other words, 57% of the variance of total remaining scores is due to the effect of the treatment. On the other hand, after modifying the self-efficacy pretest scores , the difference between the control and experimental groups was significant at P<0.001 level. In other words, cognitive group therapy improves self-efficacy in the experimental group compared to the control group in the posttest. In particular, 39% of the variance of total remaining scores is due to the effect of the intervention.

4. Discussion

Divorce is one of the causes of families falling apart, which has many undesired social consequences. The present study explored socio-psychological issues among divorced females. However, few interventions and research studies in our country have addressed psychological improvement and reconstruction of divorced women. This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on improving depression and self-efficacy of divorced women in Varamin City, Iran.

According to Table 2, cognitive group therapy has significantly reduced depression in the experimental group. The results of this study are in line with the findings of previous research (Hall, Kellett, Berrios, Balls, & Scott, 2011; Gilliam et al., 2011; O’Mahen et al., 2012; Pajares & Valiante, 2002; Ghamari et al., 2016), which have addressed the effectiveness of cognitive therapy on the reduction of depression in divorced women.

Cognitive therapy positively changes people’s interpretation of life events. Thus, divorced women who encounter multiple negative aftermath and experiences of their lives can benefit from the effects of cognitive therapy and achieve great results. Cognitive group therapy suggests that the formation of feelings such as depression, anxiety, and distress are a result of their attitude towards themselves, others, and the life. Group members will find that changing their attitudes can change their feelings. The experimental group members realized that they were able to disentangle themselves from depression by examining their illogical thinking and attitudes and change them to realistic beliefs and insights (Stack & Scourfield, 2015).

Table 4 indicates that group cognitive therapy has improved self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to women’s confidence in their own competencies. Effective people certainly face their problems with more logical and realistic solutions and set goals compatible with their abilities and opportunities. Research suggests that cognitive-behavioral group therapy increased self-esteem in women with addicted spouses (Salehzadeh, Kalantari, & Molavi, 2011). Also, cognitive group therapy has reduced the level of depression and enhanced self-efficacy in women supported by the Welfare Ministry.

Cognitive group therapy also helped group members to gain a realistic attitude toward themselves and their own abilities and capacities. They also realize that divorce is not the end, but rather an event interpreted by one’s attitude. Different challenges and techniques of cognitive therapy helped the group members, consider their worth and self-esteem to change their irrational attitudes and focus on solutions, instead of “adversities”, if they want to strengthen themselves and their self-efficacy.

The present research also demonstrated that in this approach, the group members (divorced women) are taught an appraisal process to recognize their distorted and ineffective cognitions which give rise to the formation of psychological disorders like depression. The leader of the group helps members formulate their hypotheses and test their assumptions. Through collaborative effort, members of the group are trained to distinguish between their thoughts and events that are actually happening. In the context of group cognitive counseling, members are also taught to identify, observe, and monitor their thoughts and assumptions, and especially their negative thinkings (Zaire & Nazari, 2014).

Considering the religious cultural context of this small city, cognitive group therapy approach could be very useful for the female divorcees. That is because cultural sensitivity is highly emphasized in this approach and individual’s belief system is used as part of the self-challenging method. Cognitive group therapy further observes the beliefs and values of religious references that exist in the cultural context of the society. These important issues were not ignored by the researcher.

Using the principles and techniques of rational, emotional and behavioral group therapy, the group members were also trained to discriminate between their rational and efficient beliefs and their irrational and inefficient ones, regarding divorce. In this approach, group members are taught to explore the root of their self-debilitating emotional disorders, such as depression, shame, embarrassment, and so on in their system of irrational beliefs e.g., absolutism, dictates, imperatives, etc. Albert Ellis believes that we have the potential to change our cognition, emotions and behaviors. The members of the group evaluate, challenge, reformulate, and change their irrational beliefs about divorce (Graff, Whitehead, & LeCompte, 1986).

The scarcity of research literature in the field of cognitive interventions restricted the possibility of further comparisons, especially with regard to self-efficacy. Therefore, it is suggested that future researchers explore the effectiveness of cognitive approach on self-efficacy in various groups. Because the post-divorce psychological problems of women is very important in our country, it is hoped that specialists and researchers in psychology and counseling examine the problems of these groups from different dimensions and take effective measures in this regard.

According to the results, cognitive group therapy has deceased depression and increased self-efficiency in divorced women. In general, cognitive group therapy can use effective, flexible and culturally-based techniques to offer effective interventions for divorced women who are highly vulnerable in our society. Also, cognitive group therapy further observes the beliefs and values of religious references that exist in the cultural context of the society. These important issues were considered by the researcher.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The participants were informed that their participation would be voluntarily and assured that their identity and responses would be kept confidential. Their informed consent was obtained prior to the administration of the questionnaires and intervention.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants.

References

4. Discussion

Divorce is one of the causes of families falling apart, which has many undesired social consequences. The present study explored socio-psychological issues among divorced females. However, few interventions and research studies in our country have addressed psychological improvement and reconstruction of divorced women. This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on improving depression and self-efficacy of divorced women in Varamin City, Iran.

According to Table 2, cognitive group therapy has significantly reduced depression in the experimental group. The results of this study are in line with the findings of previous research (Hall, Kellett, Berrios, Balls, & Scott, 2011; Gilliam et al., 2011; O’Mahen et al., 2012; Pajares & Valiante, 2002; Ghamari et al., 2016), which have addressed the effectiveness of cognitive therapy on the reduction of depression in divorced women.

Cognitive therapy positively changes people’s interpretation of life events. Thus, divorced women who encounter multiple negative aftermath and experiences of their lives can benefit from the effects of cognitive therapy and achieve great results. Cognitive group therapy suggests that the formation of feelings such as depression, anxiety, and distress are a result of their attitude towards themselves, others, and the life. Group members will find that changing their attitudes can change their feelings. The experimental group members realized that they were able to disentangle themselves from depression by examining their illogical thinking and attitudes and change them to realistic beliefs and insights (Stack & Scourfield, 2015).

Table 4 indicates that group cognitive therapy has improved self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to women’s confidence in their own competencies. Effective people certainly face their problems with more logical and realistic solutions and set goals compatible with their abilities and opportunities. Research suggests that cognitive-behavioral group therapy increased self-esteem in women with addicted spouses (Salehzadeh, Kalantari, & Molavi, 2011). Also, cognitive group therapy has reduced the level of depression and enhanced self-efficacy in women supported by the Welfare Ministry.

Cognitive group therapy also helped group members to gain a realistic attitude toward themselves and their own abilities and capacities. They also realize that divorce is not the end, but rather an event interpreted by one’s attitude. Different challenges and techniques of cognitive therapy helped the group members, consider their worth and self-esteem to change their irrational attitudes and focus on solutions, instead of “adversities”, if they want to strengthen themselves and their self-efficacy.

The present research also demonstrated that in this approach, the group members (divorced women) are taught an appraisal process to recognize their distorted and ineffective cognitions which give rise to the formation of psychological disorders like depression. The leader of the group helps members formulate their hypotheses and test their assumptions. Through collaborative effort, members of the group are trained to distinguish between their thoughts and events that are actually happening. In the context of group cognitive counseling, members are also taught to identify, observe, and monitor their thoughts and assumptions, and especially their negative thinkings (Zaire & Nazari, 2014).

Considering the religious cultural context of this small city, cognitive group therapy approach could be very useful for the female divorcees. That is because cultural sensitivity is highly emphasized in this approach and individual’s belief system is used as part of the self-challenging method. Cognitive group therapy further observes the beliefs and values of religious references that exist in the cultural context of the society. These important issues were not ignored by the researcher.

Using the principles and techniques of rational, emotional and behavioral group therapy, the group members were also trained to discriminate between their rational and efficient beliefs and their irrational and inefficient ones, regarding divorce. In this approach, group members are taught to explore the root of their self-debilitating emotional disorders, such as depression, shame, embarrassment, and so on in their system of irrational beliefs e.g., absolutism, dictates, imperatives, etc. Albert Ellis believes that we have the potential to change our cognition, emotions and behaviors. The members of the group evaluate, challenge, reformulate, and change their irrational beliefs about divorce (Graff, Whitehead, & LeCompte, 1986).

The scarcity of research literature in the field of cognitive interventions restricted the possibility of further comparisons, especially with regard to self-efficacy. Therefore, it is suggested that future researchers explore the effectiveness of cognitive approach on self-efficacy in various groups. Because the post-divorce psychological problems of women is very important in our country, it is hoped that specialists and researchers in psychology and counseling examine the problems of these groups from different dimensions and take effective measures in this regard.

According to the results, cognitive group therapy has deceased depression and increased self-efficiency in divorced women. In general, cognitive group therapy can use effective, flexible and culturally-based techniques to offer effective interventions for divorced women who are highly vulnerable in our society. Also, cognitive group therapy further observes the beliefs and values of religious references that exist in the cultural context of the society. These important issues were considered by the researcher.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The participants were informed that their participation would be voluntarily and assured that their identity and responses would be kept confidential. Their informed consent was obtained prior to the administration of the questionnaires and intervention.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants.

References

- Aghaei, M., Samkhaniyan, E., Mahdavi, A., Faraji, J., & Roshandel, Z. (2015). Effectiveness of behavioral_cognitive group therapy on depression, anxiety and stress of patients with coronary heart disease. Journal of Medicine and Living, 8(4), 252-7. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Barati, S. (1997). [The relationship between self-efficacy, self-esteem and autocracy among high school students (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Ahvaz: Shahid Chamran University.

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. F. (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67(3), 588-97. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13]

- Bourassa, K. J., Sbarra, D. A., & Whisman, M. A. (2015). Women in very low quality marriages gain life satisfaction following divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(3), 490-9. [DOI:10.1037/fam0000075]

- Brown, S. L., Sanchez, L. A., Nock, S. L., & Wright, J. D. (2006). Links between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital quality, stability, and divorce: A comparison of covenant versus standard marriages. Social Science Research, 35(2), 454-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.03.001]

- Corey, G. (1995). Theory and practice of group counseling [K. Zahrakar, F. Mohsenzadeh, A. Heidarnia, A. Boostanipour, A. Sami, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Virayesh.

- Gähler, M. (2006). “To Divorce Is to Die a Bit...”: A longitudinal study of marital disruption and psychological distress among Swedish women and men. The Family Journal, 14(4), 372-82. [DOI:10.1177/1066480706290145]

- Ghamari Kivi, H., Rezaii Sharif, A., & Esmaeli Ghazi Valoii, F. (2016). [The effectiveness of metaphorical cognitive and behavioral therapy on depression and resilience in divorced women (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Social Work, 5(1), 5-12.

- Gilliam, C. M., Norberg, M. M., Villavicencio, A., Morrison, S., Hannan, S. E., & Tolin, D. F. (2011). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: An open trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(11), 802-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.008]

- Goldenberg, H., & Goldenberg, I. (2012). Family therapy: An overview. Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning.

- Graff, R. W., Whitehead, G. I., & LeCompte, M. (1986). Group treatment with divorced women using cognitive-behavioral and supportive-insight methods. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(3), 276-81. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.33.3.276]

- Hall, J., Kellett, S., Berrios, R., Balls, M. K., & Scott, S. (2016). Efficacy of cognitve Behavioral therapy for Generalized anxiety Disorder in older Adults: Systematic review meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(11), 1063-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.06.006.] [PMID]

- Hamid, N., Boshlideh, K., Eidibeigi, M., & Dehghanizadeh, Z. (2012). [Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy based on religious oriented in divorced women for depression (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 1(1), 54-64.

- Henkel, V., Mergl, R., Allgaier, A. K., Hautzinger, M., Kohnen, R., Coyne, J. C., et al. (2010). Treatment of atypical depression: Post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled study testing the efficacy of sertraline and cognitive behavioural therapy in mildly depressed outpatients. European Psychiatry, 25(8), 491-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.010]

- Keramati, H. (2001). [The relationship between perceived self-efficacy and attitude toward math with mathematical progress among high school students (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Moallem University.

- Lavelle, B., & Smock, P. J. (2012). Divorce and women’s risk of health insurance loss. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 413-31. [DOI:10.1177/0022146512465758]

- Majidian, F. (2005). [The relationship between self-efficacy and Resilience with job stress among senior secondary school managers in Sanandaj (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabataba’i University.

- Mami, S., Narengi, f., & Malk Zadeh, F. (2014). The effectiveness of cognitive – behavioral training on depression and psychological wellbeing of the divorced women. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 4(Special Issue), 43-9.

- McEvoy, P. M., Nathan, P., Rapee, R. M., & Campbell, B. N. (2012). Cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia: Evidence of transportability to community clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(4), 258-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009]

- Nazari, A., & Asadi, M. (2011). [The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on decreasing depression among high school students (Persian)]. Journal of Knowledge & Health, 6(1):44-48.

- Nilsson, M. H., Hagell, P., & Iwarsson, S. (2015). Psychometric properties of the General Self‐Efficacy Scale in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 132(2), 89-96. [DOI:10.1111/ane.12368]

- Okumura, Y., & Ichikura, K. (2014). Efficacy and acceptability of group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 164, 155-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.023]

- O’Mahen, H., Fedock, G., Henshaw, E., Himle, J. A., Forman, J., & Flynn, H. A. (2012). Modifying CBT for perinatal depression: What do women want? A qualitative study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 359-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.05.005]

- Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (2002). Students’ self-efficacy in their self-regulated learning strategies: A developmental perspective. Psychologia, 45(4), 211-21. [DOI:10.2117/psysoc.2002.211]

- Perry, B. L. (2014). Symptoms, stigma, or secondary social disruption: Three mechanisms of network dynamics in severe mental illness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(1), 32-53. [DOI: 10.1177/0265407513484632]

- Pourshabaz, A. (1994). [The relationship between the assessment of the amount of stress of life events and Personality type in cancer patients (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tehran Institute of Psychiatry.

- Ricca, V., Castellini, G., Mannucci, E., Sauro, C. L., Ravaldi, C., Rotella, C. M., et al. (2010). Comparison of individual and group cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder: A randomized, three-year follow-up study. Appetite, 55(3), 656-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.019]

- Riso, L. P., du Toit, P. L., Stein, D. J., & Young, J. E. (2007). Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: A scientist-practitioner guide. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association.

- Salehzadeh, M., Kalantari, M., Molavi, H. N. (2011). [The effectiveness of cognitive–behavioral group therapy on depression in intractable epileptic patients (Persian)]. Advances in Cognitive Science, 12(2), 59-68.

- Schatz, E., Madhavan, S., & Williams, J. (2011). Female-headed households contending with AIDS-related hardship in rural South Africa. Health & place, 17(2), 598-605. [DOI:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.017]

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663-671. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663]

- Stack, S., & Scourfield, J. (2015). Recency of divorce, depression, and suicide risk. Journal of Family Issues, 36(6), 695-715. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X13494824]

- Taheri, A., & Jamshidifar, Z. (2007). [The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on decreasing the symptoms of depression (Persian)]. Applied Psychology, 1(3), 51-61.

- Taylor, T. L., & Montgomery, P. (2007). Can cognitive-behavioral therapy increase self-esteem among depressed adolescents? A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(7), 823-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.010]

- Vázquez, F. L., Torres, A., Blanco, V., Díaz, O., Otero, P., & Hermida, E. (2012). Comparison of relaxation training with a cognitive-behavioural intervention for indicated prevention of depression in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(11), 1456-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.007]

- Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35(4), 416-31. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048]

- Wu, A. M. S., Tang, C. K. K., & Kwok, T. C. Y. (2004). Self-efficacy, health locus of control, and psychological distress in elderly Chinese women with chronic illnesses. Aging & Mental Health, 8(1), 21-8. [DOI:10.1080/13607860310001613293]

- Zare, B., Nazari, T. (2014). [The effectiveness of group cognitive therapy on self efficacy and depression in women who head families (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 14(4), 83-97.

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2018/03/12 | Accepted: 2018/07/5 | Published: 2018/10/1

Received: 2018/03/12 | Accepted: 2018/07/5 | Published: 2018/10/1

References

1. Aghaei, M., Samkhaniyan, E., Mahdavi, A., Faraji, J., & Roshandel, Z. (2015). Effectiveness of behavioral_cognitive group therapy on depression, anxiety and stress of patients with coronary heart disease. Journal of Medicine and Living, 8(4), 252-7. [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Barati, S. (1997). [The relationship between self-efficacy, self-esteem and autocracy among high school students (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Ahvaz: Shahid Chamran University.

3. Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. F. (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67(3), 588-97. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13] [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13]

4. Bourassa, K. J., Sbarra, D. A., & Whisman, M. A. (2015). Women in very low quality marriages gain life satisfaction following divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(3), 490-9. [DOI:10.1037/fam0000075] [DOI:10.1037/fam0000075]

5. Brown, S. L., Sanchez, L. A., Nock, S. L., & Wright, J. D. (2006). Links between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital quality, stability, and divorce: A comparison of covenant versus standard marriages. Social Science Research, 35(2), 454-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.03.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.03.001]

6. Corey, G. (1995). Theory and practice of group counseling [K. Zahrakar, F. Mohsenzadeh, A. Heidarnia, A. Boostanipour, A. Sami, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Virayesh.

7. Gähler, M. (2006). "To Divorce Is to Die a Bit...": A longitudinal study of marital disruption and psychological distress among Swedish women and men. The Family Journal, 14(4), 372-82. [DOI:10.1177/1066480706290145] [DOI:10.1177/1066480706290145]

8. Ghamari Kivi, H., Rezaii Sharif, A., & Esmaeli Ghazi Valoii, F. (2016). [The effectiveness of metaphorical cognitive and behavioral therapy on depression and resilience in divorced women (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Social Work, 5(1), 5-12.

9. Gilliam, C. M., Norberg, M. M., Villavicencio, A., Morrison, S., Hannan, S. E., & Tolin, D. F. (2011). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: An open trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(11), 802-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.008] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.008]

10. Goldenberg, H., & Goldenberg, I. (2012). Family therapy: An overview. Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning.

11. Graff, R. W., Whitehead, G. I., & LeCompte, M. (1986). Group treatment with divorced women using cognitive-behavioral and supportive-insight methods. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(3), 276-81. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.33.3.276] [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.33.3.276]

12. Hall, J., Kellett, S., Berrios, R., Balls, M. K., & Scott, S. (2016). Efficacy of cognitve Behavioral therapy for Generalized anxiety Disorder in older Adults: Systematic review meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(11), 1063-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.06.006.] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.06.006]

13. Hamid, N., Boshlideh, K., Eidibeigi, M., & Dehghanizadeh, Z. (2012). [Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy based on religious oriented in divorced women for depression (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 1(1), 54-64.

14. Henkel, V., Mergl, R., Allgaier, A. K., Hautzinger, M., Kohnen, R., Coyne, J. C., et al. (2010). Treatment of atypical depression: Post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled study testing the efficacy of sertraline and cognitive behavioural therapy in mildly depressed outpatients. European Psychiatry, 25(8), 491-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.010] [DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.010]

15. Keramati, H. (2001). [The relationship between perceived self-efficacy and attitude toward math with mathematical progress among high school students (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Moallem University.

16. Lavelle, B., & Smock, P. J. (2012). Divorce and women's risk of health insurance loss. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 413-31. [DOI:10.1177/0022146512465758] [DOI:10.1177/0022146512465758]

17. Majidian, F. (2005). [The relationship between self-efficacy and Resilience with job stress among senior secondary school managers in Sanandaj (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Allameh Tabataba'i University.

18. Mami, S., Narengi, f., & Malk Zadeh, F. (2014). The effectiveness of cognitive – behavioral training on depression and psychological wellbeing of the divorced women. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 4(Special Issue), 43-9.

19. McEvoy, P. M., Nathan, P., Rapee, R. M., & Campbell, B. N. (2012). Cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia: Evidence of transportability to community clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(4), 258-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009]

20. Nazari, A., & Asadi, M. (2011). [The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on decreasing depression among high school students (Persian)]. Journal of Knowledge & Health, 6(1):44-48.

21. Nilsson, M. H., Hagell, P., & Iwarsson, S. (2015). Psychometric properties of the General Self‐Efficacy Scale in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 132(2), 89-96. [DOI:10.1111/ane.12368] [DOI:10.1111/ane.12368]

22. Okumura, Y., & Ichikura, K. (2014). Efficacy and acceptability of group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 164, 155-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.023] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.023]

23. O'Mahen, H., Fedock, G., Henshaw, E., Himle, J. A., Forman, J., & Flynn, H. A. (2012). Modifying CBT for perinatal depression: What do women want? A qualitative study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 359-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.05.005] [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.05.005]

24. Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (2002). Students' self-efficacy in their self-regulated learning strategies: A developmental perspective. Psychologia, 45(4), 211-21. [DOI:10.2117/psysoc.2002.211] [DOI:10.2117/psysoc.2002.211]

25. Perry, B. L. (2014). Symptoms, stigma, or secondary social disruption: Three mechanisms of network dynamics in severe mental illness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(1), 32-53. [DOI: 10.1177/0265407513484632] [DOI:10.1177/0265407513484632]

26. Pourshabaz, A. (1994). [The relationship between the assessment of the amount of stress of life events and Personality type in cancer patients (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tehran Institute of Psychiatry.

27. Ricca, V., Castellini, G., Mannucci, E., Sauro, C. L., Ravaldi, C., Rotella, C. M., et al. (2010). Comparison of individual and group cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder: A randomized, three-year follow-up study. Appetite, 55(3), 656-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.019] [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.019]

28. Riso, L. P., du Toit, P. L., Stein, D. J., & Young, J. E. (2007). Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: A scientist-practitioner guide. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association. [DOI:10.1037/11561-000]

29. Salehzadeh, M., Kalantari, M., Molavi, H. N. (2011). [The effectiveness of cognitive–behavioral group therapy on depression in intractable epileptic patients (Persian)]. Advances in Cognitive Science, 12(2), 59-68.

30. Schatz, E., Madhavan, S., & Williams, J. (2011). Female-headed households contending with AIDS-related hardship in rural South Africa. Health & place, 17(2), 598-605. [DOI:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.017] [DOI:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.017]

31. Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663-671. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663] [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663]

32. Stack, S., & Scourfield, J. (2015). Recency of divorce, depression, and suicide risk. Journal of Family Issues, 36(6), 695-715. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X13494824] [DOI:10.1177/0192513X13494824]

33. Taheri, A., & Jamshidifar, Z. (2007). [The effectiveness of cognitive group therapy on decreasing the symptoms of depression (Persian)]. Applied Psychology, 1(3), 51-61.

34. Taylor, T. L., & Montgomery, P. (2007). Can cognitive-behavioral therapy increase self-esteem among depressed adolescents? A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(7), 823-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.010] [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.010]

35. Vázquez, F. L., Torres, A., Blanco, V., Díaz, O., Otero, P., & Hermida, E. (2012). Comparison of relaxation training with a cognitive-behavioural intervention for indicated prevention of depression in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(11), 1456-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.007] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.007]

36. Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35(4), 416-31. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048] [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048]

37. Wu, A. M. S., Tang, C. K. K., & Kwok, T. C. Y. (2004). Self-efficacy, health locus of control, and psychological distress in elderly Chinese women with chronic illnesses. Aging & Mental Health, 8(1), 21-8. [DOI:10.1080/13607860310001613293] [DOI:10.1080/13607860310001613293]

38. Zare, B., Nazari, T. (2014). [The effectiveness of group cognitive therapy on self efficacy and depression in women who head families (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 14(4), 83-97.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |