Volume 6, Issue 1 (Winter 2018- 2018)

PCP 2018, 6(1): 21-28 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ansari N, Shakiba S, Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi M, Mohammadkhani P, Aminoroaya S, Sabzainpoor N. Role of Emotional Dysregulation and Childhood Trauma in Emotional Eating Behavior. PCP 2018; 6 (1) :21-28

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-482-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-482-en.html

Negin Ansari *1

, Shima Shakiba2

, Shima Shakiba2

, Mohammad Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi2

, Mohammad Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi2

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani2

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani2

, Sarah Aminoroaya2

, Sarah Aminoroaya2

, Naser Sabzainpoor3

, Naser Sabzainpoor3

, Shima Shakiba2

, Shima Shakiba2

, Mohammad Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi2

, Mohammad Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi2

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani2

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani2

, Sarah Aminoroaya2

, Sarah Aminoroaya2

, Naser Sabzainpoor3

, Naser Sabzainpoor3

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. , negin_ansari@ymail.com

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Behavioral Science, University Of Alameh, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Behavioral Science, University Of Alameh, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 521 kb]

(3497 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (11070 Views)

Full-Text: (4312 Views)

1. Introduction

Emotional eating is defined as “the tendency to overeat in response to negative emotions such as anxiety or irritability” (van Strien, Konttinen, Homberg, Engels, & Winkens, 2016). It implies eating beyond the satiation point or eating in the absence of physiological hunger. Emotional eating is characterized by eating unhealthy food such as sugary desserts and fast food, which are highly detrimental to human health (Carnell, Gibson, Benson, Ochner, & Geliebter, 2012). Thus, emotional eating might contribute to an unhealthy lifestyle and cause severe weight problems like being overweight or obese over time (e.g. Braet et al.,2008; Bryant, King, & Blundell, 2008). In addition, the longitudinal study of Stice et al. (2002) illustrated that emotional eating is an important predictor of binge eating.

Binge eating is defined as eating large amounts of food in short periods of time while experiencing loss of control over eating. Binge eating is a major sign of the Binge Eating Disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In fact, emotional eating behavior is considered as a way to cope with negative emotions and experiences and is different from eating in the state of physical hunger (Doğan, Tekin, & Katrancıoğlu, 2011). Although emotional eating behavior helps the person to overcome negative thoughts and feelings, it is not much effective in solving problems and leads to an increase in weight, obesity, and general health problems, such as hypertension and diabetes (Doğan et al., 2011).

One of the important factors in emotional eating behavior is emotional dysregulation, which is defined as a difficulty in the regulation of affective states and self-control in emotion-related behaviors (Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005). This variable consists of several components, including emotional awareness, understanding of other’s emotions, ability to accept emotional distress, and ability to involve in purposeful activities when experiencing emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Difficulty in emotion regulation has roots in different factors, including genetic factors and childhood traumas, especially emotional abuse during childhood. People with emotion regulation problems tend to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as substance and alcohol abuse and dissociative experiences. Emotional eating, in fact, is attributed to maladaptive emotion regulation strategies in which effective emotion regulation is affected by eating behavior (Zysberg & Rubanov, 2010).

The multidimensional model of emotion regulation, proposed by Gratz and Roemer (2004), was selected as the theoretical framework of the present study. This model emphasizes adaptive response to emotional distress in contrast to rigid control or suppression of emotional arousal. Impairment in one or several aspects of this model may reflect emotion dysregulation.

Child maltreatment is a general term used to describe all forms of child abuse, neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, disregard, emotional abuse, and recently, family violence (Bücker et al., 2012). Exposure to childhood trauma is largely associated with a group of developmental and psychological outcomes in adulthood (Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar, & Toth, 2010; Heim & Nemeroff, 2001), such as eating disorders and addiction (Burns, Fischer, Jackson, & Harding, 2012). Children who are mistreated are at a greater risk of depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse rather than other children. In addition, depression, PTSD, and substance abuse have higher comorbidity with obesity (De Wit et al., 2010; Hemmingsson, Johansson, & Reynisdottir, 2014; Pagoto et al., 2012), which may result from an increase in emotional eating (Talbot, Maguen, Epel, Metzler, & Neylan, 2013). People who have experienced maltreatment in their childhood are at a higher risk for using maladaptive coping strategies, including stress-induced emotional eating (Evers, Stok, & de Ridder, 2010).

Individuals exposed to interpersonal trauma during childhood face greater difficulties in emotion regulation (Cloitre, Miranda, Stovall-McClough, & Han, 2005; Van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005). Secure attachment appears to be crucial for the development of adaptive emotion regulation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008). In contrast, insecure attachment has been found to be positively associated with disordered eating (Ward, Ramsay, & Treasure, 2000), and emotion dysregulation has been reported to mediate this relationship (Ty & Francis, 2013). It has been suggested that eating disorder, including binge eating, vomiting, and restriction behavior, may alleviate negative emotion (Cooper, Wells, & Todd, 2004; Corstorphine, Waller, Lawson, & Ganis, 2007).

Despite the presence of studies that link trauma with emotional maladaptation and psychopathology, the relationship between these potential factors has not yet been adequately proven in the literature. Therefore, more research is needed on the relationship between these factors, especially in both sexes. So, the aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship among emotion dysregulation, childhood trauma, and emotional eating behavior and identify the role of these variables in emotional eating behavior.

2. Methods

This is a descriptive-cross sectional study conducted on 700 male and female adults, aged 18 to 50 years, who were recruited from parks, cultural centers, and public libraries in Tehran using the purposeful sampling method. The following measures were used in the present paper:

The questionnaire for assessing demographic variables assessed demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, education level, weight, height, and history of psychiatric disorders.

The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) is a 33-item self-report scale that consisted of three subscales; each item was answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘never‘) to 5 (‘very often‘). It evaluated the presence of three types of disturbed eating behavior: restrained eating, external eating, and emotional eating. The DEBQ has a good reliability in both clinical and non-clinical obese samples (van Strien et al., 1986). In this study, Cronbach’s α of the DEBQ was=0.95.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a 36-item self-report scale that consisted of six subscales. Its items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicated more difficulty in regulating emotions. The DERS has a high internal consistency (0.93), and all its subscales have Cronbach’s alphas greater than 0.80. In the present study, the internal Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was developed by (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997), and its final 34-item version was developed in 1998. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale that assessed five subscales, i.e., physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse. The CTQ has relatively high validity and reliability. Using test-retest and Cronbach’s alpha methods, (Bernstein et al., 1997), reported the reliability of different factors of the CTQ to be from 0.79 to 0.94 (Bernstein et al., 1997). Ebrahimi et al. (2013) found the reliability of the total scale and its subscales to be from 0.81 to 0.97; these values indicate a high relia-bility of the CTQ. In the present study, the internal Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Similar forms of questionnaires were randomly classified and distributed among the participants. The participants first received a brief explanation of the study and its objectives. Those who showed their willingness to participate in the study were given consent forms, and those who returned their informed consents were given the questionnaires to complete. Moreover, before completing the questionnaires, the participants received instructions on how to complete them. Study data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and multiple regression analysis. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software V. 20.

3. Results

A total of 700 adults (51.7% women; 48.6% men) completed the questionnaires. According to Table 1, 58.8% of the participants described their marital status as single, 38.4% as married, and 2.8% as divorced. Demographic information of participants, such as gender, age, marital status, weight, and height are presented in the Tables 1 and 2.

Emotional eating is defined as “the tendency to overeat in response to negative emotions such as anxiety or irritability” (van Strien, Konttinen, Homberg, Engels, & Winkens, 2016). It implies eating beyond the satiation point or eating in the absence of physiological hunger. Emotional eating is characterized by eating unhealthy food such as sugary desserts and fast food, which are highly detrimental to human health (Carnell, Gibson, Benson, Ochner, & Geliebter, 2012). Thus, emotional eating might contribute to an unhealthy lifestyle and cause severe weight problems like being overweight or obese over time (e.g. Braet et al.,2008; Bryant, King, & Blundell, 2008). In addition, the longitudinal study of Stice et al. (2002) illustrated that emotional eating is an important predictor of binge eating.

Binge eating is defined as eating large amounts of food in short periods of time while experiencing loss of control over eating. Binge eating is a major sign of the Binge Eating Disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In fact, emotional eating behavior is considered as a way to cope with negative emotions and experiences and is different from eating in the state of physical hunger (Doğan, Tekin, & Katrancıoğlu, 2011). Although emotional eating behavior helps the person to overcome negative thoughts and feelings, it is not much effective in solving problems and leads to an increase in weight, obesity, and general health problems, such as hypertension and diabetes (Doğan et al., 2011).

One of the important factors in emotional eating behavior is emotional dysregulation, which is defined as a difficulty in the regulation of affective states and self-control in emotion-related behaviors (Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005). This variable consists of several components, including emotional awareness, understanding of other’s emotions, ability to accept emotional distress, and ability to involve in purposeful activities when experiencing emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Difficulty in emotion regulation has roots in different factors, including genetic factors and childhood traumas, especially emotional abuse during childhood. People with emotion regulation problems tend to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as substance and alcohol abuse and dissociative experiences. Emotional eating, in fact, is attributed to maladaptive emotion regulation strategies in which effective emotion regulation is affected by eating behavior (Zysberg & Rubanov, 2010).

The multidimensional model of emotion regulation, proposed by Gratz and Roemer (2004), was selected as the theoretical framework of the present study. This model emphasizes adaptive response to emotional distress in contrast to rigid control or suppression of emotional arousal. Impairment in one or several aspects of this model may reflect emotion dysregulation.

Child maltreatment is a general term used to describe all forms of child abuse, neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, disregard, emotional abuse, and recently, family violence (Bücker et al., 2012). Exposure to childhood trauma is largely associated with a group of developmental and psychological outcomes in adulthood (Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar, & Toth, 2010; Heim & Nemeroff, 2001), such as eating disorders and addiction (Burns, Fischer, Jackson, & Harding, 2012). Children who are mistreated are at a greater risk of depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse rather than other children. In addition, depression, PTSD, and substance abuse have higher comorbidity with obesity (De Wit et al., 2010; Hemmingsson, Johansson, & Reynisdottir, 2014; Pagoto et al., 2012), which may result from an increase in emotional eating (Talbot, Maguen, Epel, Metzler, & Neylan, 2013). People who have experienced maltreatment in their childhood are at a higher risk for using maladaptive coping strategies, including stress-induced emotional eating (Evers, Stok, & de Ridder, 2010).

Individuals exposed to interpersonal trauma during childhood face greater difficulties in emotion regulation (Cloitre, Miranda, Stovall-McClough, & Han, 2005; Van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005). Secure attachment appears to be crucial for the development of adaptive emotion regulation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008). In contrast, insecure attachment has been found to be positively associated with disordered eating (Ward, Ramsay, & Treasure, 2000), and emotion dysregulation has been reported to mediate this relationship (Ty & Francis, 2013). It has been suggested that eating disorder, including binge eating, vomiting, and restriction behavior, may alleviate negative emotion (Cooper, Wells, & Todd, 2004; Corstorphine, Waller, Lawson, & Ganis, 2007).

Despite the presence of studies that link trauma with emotional maladaptation and psychopathology, the relationship between these potential factors has not yet been adequately proven in the literature. Therefore, more research is needed on the relationship between these factors, especially in both sexes. So, the aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship among emotion dysregulation, childhood trauma, and emotional eating behavior and identify the role of these variables in emotional eating behavior.

2. Methods

This is a descriptive-cross sectional study conducted on 700 male and female adults, aged 18 to 50 years, who were recruited from parks, cultural centers, and public libraries in Tehran using the purposeful sampling method. The following measures were used in the present paper:

The questionnaire for assessing demographic variables assessed demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, education level, weight, height, and history of psychiatric disorders.

The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) is a 33-item self-report scale that consisted of three subscales; each item was answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘never‘) to 5 (‘very often‘). It evaluated the presence of three types of disturbed eating behavior: restrained eating, external eating, and emotional eating. The DEBQ has a good reliability in both clinical and non-clinical obese samples (van Strien et al., 1986). In this study, Cronbach’s α of the DEBQ was=0.95.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a 36-item self-report scale that consisted of six subscales. Its items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicated more difficulty in regulating emotions. The DERS has a high internal consistency (0.93), and all its subscales have Cronbach’s alphas greater than 0.80. In the present study, the internal Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was developed by (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997), and its final 34-item version was developed in 1998. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale that assessed five subscales, i.e., physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse. The CTQ has relatively high validity and reliability. Using test-retest and Cronbach’s alpha methods, (Bernstein et al., 1997), reported the reliability of different factors of the CTQ to be from 0.79 to 0.94 (Bernstein et al., 1997). Ebrahimi et al. (2013) found the reliability of the total scale and its subscales to be from 0.81 to 0.97; these values indicate a high relia-bility of the CTQ. In the present study, the internal Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Similar forms of questionnaires were randomly classified and distributed among the participants. The participants first received a brief explanation of the study and its objectives. Those who showed their willingness to participate in the study were given consent forms, and those who returned their informed consents were given the questionnaires to complete. Moreover, before completing the questionnaires, the participants received instructions on how to complete them. Study data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and multiple regression analysis. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software V. 20.

3. Results

A total of 700 adults (51.7% women; 48.6% men) completed the questionnaires. According to Table 1, 58.8% of the participants described their marital status as single, 38.4% as married, and 2.8% as divorced. Demographic information of participants, such as gender, age, marital status, weight, and height are presented in the Tables 1 and 2.

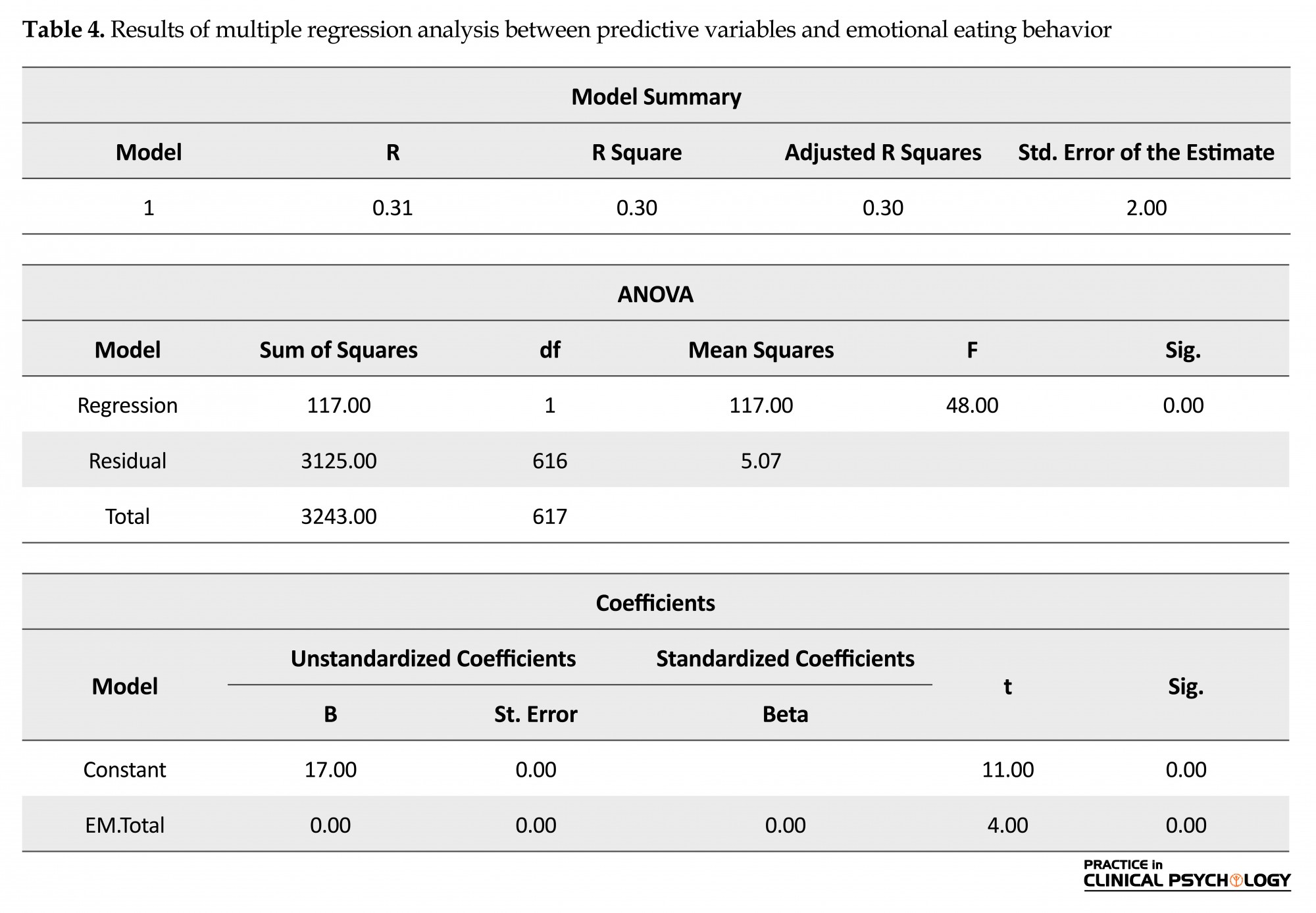

The results of Pearson correlation coefficient indicate a significant and positive correlation between emotion dysregulation and emotional eating (r=0.30; P<0.001). This means that as the emotion dysregulation increases, the emotional eating behavior also increases. The results also indicate a significant and positive correlation between childhood trauma and emotional eating behavior (r=0.19; P<0.001). This finding indicates that as the childhood trauma increases, the emotional eating behavior also increases (Table 3). A multivariate regression analysis was calculated to predict emotional eating behavior based on emotion dysregulation and childhood trauma. A significant regression equation was found (F(1, 616)=48.00, P<0.00), with an R2 of 0.30 (Table 4).

Furthermore, the comparison of the zero-order correlation values between the two variables showed that emotion dysregulation had a stronger role in emotional eating. This is because the zero-order correlation for emotion dysregulation and emotional eating behavior is equal to 0.30.

4. Discussion

The results of Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a significant and positive correlation between emotion dysregulation and emotional eating (r=0.30; P<0.001). This finding is fully supported by Gratz and Roemer’s model (2004), who also showed that maladaptive strategies of emotion regulation were significant predictors of bulimic episodes. Moreover, another study reported that exposure to acute and chronic stressors may accelerate emotional eating behavior (Adam & Epel, 2007; Michopoulos, Toufexis, & Wilson, 2012).

In our study, childhood trauma exposure had a significant positive relationship with emotional eating behavior (r=0.19; P<0.001) in adulthood. This finding is supported by previous studies that indicated different types of childhood trauma are significantly related to eating psychopathology (Burns et al., 2012; Michopoulos et al., 2015; Moulton, Newman, Power, Swanson, & Day, 2015). This finding is also consistent with Cloitre, Cohen, & Koenen (2006) model in which the caregivers’ inappropriate response to the child’s emotional experience may confuse the child regarding the emotional state and may negatively impact the individual’s ability to tolerate and regulate their emotions. Thus, emotional eating may serve to aide distraction, avoidance, or dampening down the experience of negative emotions for individuals who have experienced childhood trauma. Importantly, our findings are consistent with previous findings that indicate childhood trauma make children vulnerable to both emotion dysregulation and developing psychopathology in adulthood (Moulton et al., 2015). Therefore, according to data, emotional eating in individuals who have been exposed to childhood trauma is primarily due to difficulties in emotion regulation.

Therefore, based on the results of previous studies, including the findings of Corstorphine, Waller, Lawson, and Ganis (2007), we can conclude that when children experience trauma, they will find difficulties in emotion regulation and use of proper strategies. Therefore, these individuals tend to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, including emotional eating, substance abuse, self-harm, and dissociation in their adulthood (Corstorphine et al., 2007).

The results of regression analysis also showed that emotion dysregulation had a stronger role in emotional eating. It indicates that emotion dysregulation should be considered in the psychopathology and treatment of individuals suffering from psychologically eating problems.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that preventive interventions such as increasing adaptive emotion regulation strategies among child maltreatment survivors could decrease emotional eating symptoms in adulthood. However, there is a need to enhance our understanding of the development of emotional eating in an effort to use more practical interventions in the area of eating psychopathology.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted cautiously because of the following limitations. First, the present study was conducted on a non-clinical population; therefore, the findings must be generalized cautiously. Second, the study data were also obtained using self-report instruments that are highly vulnerable to certain biases; this may have also affected the validity of the results. Finally, the high number of items of the study questionnaires, and tiresome and distraction may have affected the answers of participants. The present study can be replicated in clinical populations. We also suggest future studies to examine other eating behavior styles such as restrictive and external eating behavior. Other researchers and clinicians are also suggested to write therapeutic protocols based on the findings of the present study and examine their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449-458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Massachusetts: American Psychiatric Association.

Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., & Handelsman, L. (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 340-348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

Bücker, J., Kapczinski, F., Post, R., Ceresér, K. M., Szobot, C., Yatham, L. N., et al (2012). Cognitive impairment in school-aged children with early trauma. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(6), 758-764. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.006

Burns, E. E., Fischer, S., Jackson, J. L., & Harding, H. G. (2012). Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005

Braet, C., Claus, L., Goossens, L., Moens, E., Van Vlierberghe, L., & Soetens, B. (2008). Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(6), 733-743. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093850

Bryant, E. J., King, N. A., & Blundell, J. E. (2008). Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obesity Reviews, 9(5), 409-419. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2007.00426.x

Bruch, H. (1973). Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. New York: Basic Books.

Carnell, S., Gibson, C., Benson, L., Ochner, C. N., & Geliebter, A. (2012). Neuroimaging and obesity: Current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Reviews, 13(1), 43-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2011.00927.x

Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., Gunnar, M. R., & Toth, S. L. (2010). The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school‐aged children. Child Development, 81(1), 252-269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x

Cloitre, M., Miranda, R., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Han, H. (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119-24.

Cloitre, M., Cohen, L., & Koenen, K. (2006). Treating the trauma of childhood abuse: Therapy for the interrupted life. New York: Guilford.

Cooper, M. J., Wells, A., & Todd, G. (2004). A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 1-16. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812931

Corstorphine, E., Waller, G., Lawson, R., & Ganis, C. (2007). Trauma and multi-impulsivity in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 8(1), 23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.009

De Wit, L., Luppino, F., Van Straten, A., Penninx, B., Zitman, F., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Research, 178(2), 230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015

Doğan, T., Tekin, E. G., & Katrancıoğlu, A. (2011). Feeding your feelings: A self-report measure of emotional eating. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2074-77. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.056

Ebrahimi, H., Dejkam, M., & Seghatoleslam, T. (2014). [Childhood traumas and suicide attempt in adulthood (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 275-282.

Evers, C., Marijn Stok, F., & de Ridder, D. T. D. (2010). Feeding Your Feelings: Emotion Regulation Strategies and Emotional Eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 792–804. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371383

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54. doi: 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94

Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001). The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x

Hemmingsson, E., Johansson, K., & Reynisdottir, S. (2014). Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15(11), 882-893. doi: 10.1111/obr.12216

Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., Turk, C. L., & Fresco, D. M. (2005). Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(10), 1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008

Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Moore, C., Villarreal, S., Ressler, K. J., & Bradley, B. (2015). The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite, 91, 129-136. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.036

Michopoulos, V., Toufexis, D., & Wilson, M. E. (2012). Social stress interacts with diet history to promote emotional feeding in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(9), 1479-90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.002

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2008). Adult attachment and affect regulation. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (pp. 503-531). New York: Guilford Press.

Moulton, S. J., Newman, E., Power, K., Swanson, V., & Day, K. (2015). Childhood trauma and eating psychopathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion dysregulation? Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003

Pagoto, S. L., Schneider, K. L., Bodenlos, J. S., Appelhans, B. M., Whited, M. C., Ma, Y., et al. (2012). Association of post‐traumatic Stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity, 20(1), 200-205. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.318

Ty, M., & Francis, A. J. (2013). Insecure attachment and disordered eating in women: The mediating processes of social comparison and emotion dysregulation. Eating Disorders, 21(2), 154-174. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2013.761089

Stice, E., & Whitenton, K. (2002). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 669-78. PMID: 12220046

Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Epel, E. S., Metzler, T. J., & Neylan, T. C. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with emotional eating. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 521-525. doi: /10.1002/jts.21824

Van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389-399. doi: 10.1002/jts.20047

Van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E., Bergers, G., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(2), 295-315. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T

Van Strien, T., Konttinen, H., Homberg, J. R., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Winkens, L. H. H. (2016). Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite, 100, 216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034

Ward, A., Ramsay, R., Turnbull, S., Benedettini, M., & Treasure, J. (2000). Attachment patterns in eating disorders: Past in the present. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(4), 370-376. PMID: 11054783

Zysberg, L., & Rubanov, A. (2010). Emotional intelligence and emotional eating patterns: a new insight into the antecedents of eating disorders? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(5), 345-348. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.009

4. Discussion

The results of Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a significant and positive correlation between emotion dysregulation and emotional eating (r=0.30; P<0.001). This finding is fully supported by Gratz and Roemer’s model (2004), who also showed that maladaptive strategies of emotion regulation were significant predictors of bulimic episodes. Moreover, another study reported that exposure to acute and chronic stressors may accelerate emotional eating behavior (Adam & Epel, 2007; Michopoulos, Toufexis, & Wilson, 2012).

In our study, childhood trauma exposure had a significant positive relationship with emotional eating behavior (r=0.19; P<0.001) in adulthood. This finding is supported by previous studies that indicated different types of childhood trauma are significantly related to eating psychopathology (Burns et al., 2012; Michopoulos et al., 2015; Moulton, Newman, Power, Swanson, & Day, 2015). This finding is also consistent with Cloitre, Cohen, & Koenen (2006) model in which the caregivers’ inappropriate response to the child’s emotional experience may confuse the child regarding the emotional state and may negatively impact the individual’s ability to tolerate and regulate their emotions. Thus, emotional eating may serve to aide distraction, avoidance, or dampening down the experience of negative emotions for individuals who have experienced childhood trauma. Importantly, our findings are consistent with previous findings that indicate childhood trauma make children vulnerable to both emotion dysregulation and developing psychopathology in adulthood (Moulton et al., 2015). Therefore, according to data, emotional eating in individuals who have been exposed to childhood trauma is primarily due to difficulties in emotion regulation.

Therefore, based on the results of previous studies, including the findings of Corstorphine, Waller, Lawson, and Ganis (2007), we can conclude that when children experience trauma, they will find difficulties in emotion regulation and use of proper strategies. Therefore, these individuals tend to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, including emotional eating, substance abuse, self-harm, and dissociation in their adulthood (Corstorphine et al., 2007).

The results of regression analysis also showed that emotion dysregulation had a stronger role in emotional eating. It indicates that emotion dysregulation should be considered in the psychopathology and treatment of individuals suffering from psychologically eating problems.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that preventive interventions such as increasing adaptive emotion regulation strategies among child maltreatment survivors could decrease emotional eating symptoms in adulthood. However, there is a need to enhance our understanding of the development of emotional eating in an effort to use more practical interventions in the area of eating psychopathology.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted cautiously because of the following limitations. First, the present study was conducted on a non-clinical population; therefore, the findings must be generalized cautiously. Second, the study data were also obtained using self-report instruments that are highly vulnerable to certain biases; this may have also affected the validity of the results. Finally, the high number of items of the study questionnaires, and tiresome and distraction may have affected the answers of participants. The present study can be replicated in clinical populations. We also suggest future studies to examine other eating behavior styles such as restrictive and external eating behavior. Other researchers and clinicians are also suggested to write therapeutic protocols based on the findings of the present study and examine their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449-458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Massachusetts: American Psychiatric Association.

Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., & Handelsman, L. (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 340-348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

Bücker, J., Kapczinski, F., Post, R., Ceresér, K. M., Szobot, C., Yatham, L. N., et al (2012). Cognitive impairment in school-aged children with early trauma. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(6), 758-764. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.006

Burns, E. E., Fischer, S., Jackson, J. L., & Harding, H. G. (2012). Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005

Braet, C., Claus, L., Goossens, L., Moens, E., Van Vlierberghe, L., & Soetens, B. (2008). Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(6), 733-743. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093850

Bryant, E. J., King, N. A., & Blundell, J. E. (2008). Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obesity Reviews, 9(5), 409-419. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2007.00426.x

Bruch, H. (1973). Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. New York: Basic Books.

Carnell, S., Gibson, C., Benson, L., Ochner, C. N., & Geliebter, A. (2012). Neuroimaging and obesity: Current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Reviews, 13(1), 43-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2011.00927.x

Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., Gunnar, M. R., & Toth, S. L. (2010). The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school‐aged children. Child Development, 81(1), 252-269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x

Cloitre, M., Miranda, R., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Han, H. (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119-24.

Cloitre, M., Cohen, L., & Koenen, K. (2006). Treating the trauma of childhood abuse: Therapy for the interrupted life. New York: Guilford.

Cooper, M. J., Wells, A., & Todd, G. (2004). A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 1-16. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812931

Corstorphine, E., Waller, G., Lawson, R., & Ganis, C. (2007). Trauma and multi-impulsivity in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 8(1), 23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.009

De Wit, L., Luppino, F., Van Straten, A., Penninx, B., Zitman, F., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Research, 178(2), 230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015

Doğan, T., Tekin, E. G., & Katrancıoğlu, A. (2011). Feeding your feelings: A self-report measure of emotional eating. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2074-77. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.056

Ebrahimi, H., Dejkam, M., & Seghatoleslam, T. (2014). [Childhood traumas and suicide attempt in adulthood (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 275-282.

Evers, C., Marijn Stok, F., & de Ridder, D. T. D. (2010). Feeding Your Feelings: Emotion Regulation Strategies and Emotional Eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 792–804. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371383

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54. doi: 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94

Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001). The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x

Hemmingsson, E., Johansson, K., & Reynisdottir, S. (2014). Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15(11), 882-893. doi: 10.1111/obr.12216

Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., Turk, C. L., & Fresco, D. M. (2005). Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(10), 1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008

Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Moore, C., Villarreal, S., Ressler, K. J., & Bradley, B. (2015). The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite, 91, 129-136. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.036

Michopoulos, V., Toufexis, D., & Wilson, M. E. (2012). Social stress interacts with diet history to promote emotional feeding in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(9), 1479-90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.002

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2008). Adult attachment and affect regulation. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (pp. 503-531). New York: Guilford Press.

Moulton, S. J., Newman, E., Power, K., Swanson, V., & Day, K. (2015). Childhood trauma and eating psychopathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion dysregulation? Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003

Pagoto, S. L., Schneider, K. L., Bodenlos, J. S., Appelhans, B. M., Whited, M. C., Ma, Y., et al. (2012). Association of post‐traumatic Stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity, 20(1), 200-205. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.318

Ty, M., & Francis, A. J. (2013). Insecure attachment and disordered eating in women: The mediating processes of social comparison and emotion dysregulation. Eating Disorders, 21(2), 154-174. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2013.761089

Stice, E., & Whitenton, K. (2002). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 669-78. PMID: 12220046

Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Epel, E. S., Metzler, T. J., & Neylan, T. C. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with emotional eating. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 521-525. doi: /10.1002/jts.21824

Van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389-399. doi: 10.1002/jts.20047

Van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E., Bergers, G., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(2), 295-315. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T

Van Strien, T., Konttinen, H., Homberg, J. R., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Winkens, L. H. H. (2016). Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite, 100, 216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034

Ward, A., Ramsay, R., Turnbull, S., Benedettini, M., & Treasure, J. (2000). Attachment patterns in eating disorders: Past in the present. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(4), 370-376. PMID: 11054783

Zysberg, L., & Rubanov, A. (2010). Emotional intelligence and emotional eating patterns: a new insight into the antecedents of eating disorders? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(5), 345-348. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.009

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Psychiatry

Received: 2017/05/11 | Accepted: 2017/09/19 | Published: 2018/01/1

Received: 2017/05/11 | Accepted: 2017/09/19 | Published: 2018/01/1

References

1. Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449-458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011 [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011]

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Massa-chusetts: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

3. Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., & Handelsman, L. (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Ques-tionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychia-try, 36(3), 340-348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012 [DOI:10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012]

4. Bücker, J., Kapczinski, F., Post, R., Ceresér, K. M., Szobot, C., Yatham, L. N., et al (2012). Cognitive impairment in school-aged children with early trauma. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(6), 758-764. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.006]

5. Burns, E. E., Fischer, S., Jackson, J. L., & Harding, H. G. (2012). Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the rela-tionship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005 [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005]

6. Braet, C., Claus, L., Goossens, L., Moens, E., Van Vlierberghe, L., & Soetens, B. (2008). Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(6), 733-743. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093850 [DOI:10.1177/1359105308093850]

7. Bryant, E. J., King, N. A., & Blundell, J. E. (2008). Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obesity Reviews, 9(5), 409-419. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2007.00426.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00426.x]

8. Bruch, H. (1973). Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. New York: Basic Books.

9. Carnell, S., Gibson, C., Benson, L., Ochner, C. N., & Geliebter, A. (2012). Neuroimaging and obesity: Current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Reviews, 13(1), 43-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2011.00927.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00927.x]

10. Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., Gunnar, M. R., & Toth, S. L. (2010). The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school‐aged children. Child Development, 81(1), 252-269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x]

11. Cloitre, M., Miranda, R., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Han, H. (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and in-terpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119-24. [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80060-7]

12. Cloitre, M., Cohen, L., & Koenen, K. (2006). Treating the trauma of childhood abuse: Therapy for the interrupted life. New York: Guilford.

13. Cooper, M. J., Wells, A., & Todd, G. (2004). A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psy-chology, 43(1), 1-16. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812931 [DOI:10.1348/014466504772812931]

14. Corstorphine, E., Waller, G., Lawson, R., & Ganis, C. (2007). Trauma and multi-impulsivity in the eating disor-ders. Eating Behaviors, 8(1), 23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.009 [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.009]

15. De Wit, L., Luppino, F., Van Straten, A., Penninx, B., Zitman, F., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Research, 178(2), 230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015 [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015]

16. Doğan, T., Tekin, E. G., & Katrancıoğlu, A. (2011). Feeding your feelings: A self-report measure of emotional eating. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2074-77. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.056 [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.056]

17. Ebrahimi, H., Dejkam, M., & Seghatoleslam, T. (2014). [Childhood traumas and suicide attempt in adulthood (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 275-282.

18. Evers, C., Marijn Stok, F., & de Ridder, D. T. D. (2010). Feeding Your Feelings: Emotion Regulation Strategies and Emotional Eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 792–804. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371383 [DOI:10.1177/0146167210371383]

19. Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: De-velopment, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psy-chopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54. doi: 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94]

20. Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001). The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety dis-orders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x [DOI:10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01157-X]

21. Hemmingsson, E., Johansson, K., & Reynisdottir, S. (2014). Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a sys-tematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15(11), 882-893. doi: 10.1111/obr.12216 [DOI:10.1111/obr.12216]

22. Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., Turk, C. L., & Fresco, D. M. (2005). Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysreg-ulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(10), 1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008 [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008]

23. Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Moore, C., Villarreal, S., Ressler, K. J., & Bradley, B. (2015). The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite, 91, 129-136. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.036 [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.036]

24. Michopoulos, V., Toufexis, D., & Wilson, M. E. (2012). Social stress interacts with diet history to promote emo-tional feeding in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(9), 1479-90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.002 [DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.002]

25. Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2008). Adult attachment and affect regulation. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (pp. 503-531). New York: Guilford Press.

26. Moulton, S. J., Newman, E., Power, K., Swanson, V., & Day, K. (2015). Childhood trauma and eating psycho-pathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion dysregulation? Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003 [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003]

27. Pagoto, S. L., Schneider, K. L., Bodenlos, J. S., Appelhans, B. M., Whited, M. C., Ma, Y., et al. (2012). Associa-tion of post‐traumatic Stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity, 20(1), 200-205. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.318 [DOI:10.1038/oby.2011.318]

28. Ty, M., & Francis, A. J. (2013). Insecure attachment and disordered eating in women: The mediating processes of social comparison and emotion dysregulation. Eating Disorders, 21(2), 154-174. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2013.761089 [DOI:10.1080/10640266.2013.761089]

29. Stice, E., & Whitenton, K. (2002). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investi-gation. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 669-78. PMID: 12220046 [DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.669] [PMID]

30. Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Epel, E. S., Metzler, T. J., & Neylan, T. C. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder is as-sociated with emotional eating. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 521-525. doi: /10.1002/jts.21824 [DOI:10.1002/jts.21824] [PMID]

31. Van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389-399. doi: 10.1002/jts.20047 [DOI:10.1002/jts.20047]

32. Van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E., Bergers, G., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Dis-orders, 5(2), 295-315. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T

https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T [DOI:10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:23.0.CO;2-T]

33. Van Strien, T., Konttinen, H., Homberg, J. R., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Winkens, L. H. H. (2016). Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite, 100, 216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034 [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034]

34. Ward, A., Ramsay, R., Turnbull, S., Benedettini, M., & Treasure, J. (2000). Attachment patterns in eating disor-ders: Past in the present. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(4), 370-376. PMID: 11054783

https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200012)28:4<370::AID-EAT4>3.0.CO;2-P [DOI:10.1002/1098-108X(200012)28:43.0.CO;2-P]

35. Zysberg, L., & Rubanov, A. (2010). Emotional intelligence and emotional eating patterns: a new insight into the antecedents of eating disorders? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(5), 345-348. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.009 [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.009]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |