Volume 8, Issue 3 (Summer 2020)

PCP 2020, 8(3): 163-174 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sudmand N, Movallali G, Abedi A, Dadkhah A, Rostami M, Reza Soltan P. Improving the Self-Esteem and Aggression Control of Deaf Adolescent Girls: The Effectiveness of Life Skills Training. PCP 2020; 8 (3) :163-174

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-391-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-391-en.html

Nasrin Sudmand1

, Guita Movallali *2

, Guita Movallali *2

, Arezoo Abedi1

, Arezoo Abedi1

, Asghar Dadkhah1

, Asghar Dadkhah1

, Mohammad Rostami3

, Mohammad Rostami3

, Pourya Reza Soltan4

, Pourya Reza Soltan4

, Guita Movallali *2

, Guita Movallali *2

, Arezoo Abedi1

, Arezoo Abedi1

, Asghar Dadkhah1

, Asghar Dadkhah1

, Mohammad Rostami3

, Mohammad Rostami3

, Pourya Reza Soltan4

, Pourya Reza Soltan4

1- Department of Rehabilitation Counselling, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Sciences,Tehran, Iran. ,drmovallali@gmail.com

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Kurdistan, Sanandaj, Iran.

4- Department of Statistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Sciences,Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Kurdistan, Sanandaj, Iran.

4- Department of Statistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 754 kb]

(2442 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3647 Views)

Full-Text: (2906 Views)

1. Introduction

Deafness is a relatively common problem with severe effects on all aspects of the general health of deaf adolescents that also creates high levels of stress for the families (Yang, Wei, Chai, Li & Wu, 2013). Almost 1-3 children out of 1000 are born with bilateral hearing loss worldwide and in Iran (Lotfi & Movallali, 2007). Also, 15%-26% of the world population has some types of hearing loss (Movallali, Torabi & Tavakoli, 2014), and this percentage is higher in less-developed countries (Agrawal, Platz & Niparko, 2008; Béria et al., 2007). More than 90% of deaf children are born in families with no history of hearing loss (Rostami, Younesi, Movallali, Farhood & Biglarian, 2014). Hearing loss can have important effects on the physical, psychological, and social health of adolescents, and may lead to low self-esteem, irritability, isolation, depression, and anxiety (Kushalnagar et al., 2007).

Examination of the psychological and social status of deaf adolescents and young adults has shown that low self-confidence, a sense of social insecurity, isolation, generalized anxiety, low motivation, depression, and situational and selective (toward those who are close to the person) aggression, are among the salient behavioral and personality characteristics of deaf individuals (Theunissen et al., 2011). Deaf adolescents are specially characterized by low self-esteem. According to a definition by Lawernce (2006), self-esteem is a person’s evaluation of his/her self-worth and refers to a person’s attitude toward himself/herself. People make these judgments based on an evaluation of their behavior, according to their standards and values, and by comparing their own performance with that of others.

Many deaf individuals, compared with their hearing peers, have lower levels of social interaction and self-assertiveness, which also affects their self-evaluation and self-esteem. Deaf individuals with higher self-esteem, learn more effectively, engage in more constructive relationships, make better use of opportunities, and are productive and self-sufficient (Goldestein & Morgan, 2002). Previous examinations have shown that low self-esteem is associated with mental health problems (Baumeister, Heatherton & Tice, 1993; Mousavi, Movallali & Mousavi Nare, 2017). In addition, longitudinal studies have shown that low self-esteem in adolescents, can solely predict their depression (Orth, Robins & Roberts, 2008) and anxiety (Trzesniewski et al., 2006). Previous studies on deaf children and adolescents have indicated that there is a negative relationship between general self-esteem and mental health problems (Mejstad, Heiling & Svedin, 2009; Hindley, Hill, McGuigan & Kitson, 1994).

Behavioral problems, especially aggression, are also common in deaf adolescents. Most studies have shown that aggression, compared with conduct problems, is less common in deaf children and adolescents (van Eldik, Treffers, Veerman & Verhulst, 2004). Deaf children and adolescents are significantly less likely than their peers to hide their aggression (Movallali & Imani, 2015). Due to their impairments in cognitive, social, and emotional skills, these adolescents tend to show more aggression than other students (Smith, 2010). Most of these individuals have many problems in social information processing and often upset their friends and acquaintances, due to their unawareness, selecting incorrect strategies, and being unable to do simple tasks, such as asking, discussing, and having a constructive conversation (Hallahan & Kuffman, 1994).

Deaf adolescents may misinterpret other people’s guidance, and attribute hostile intentions to others, especially in high-stress situations. Social skills problems in these adolescents often lead to poor impulse control and low frustration tolerance (Hintermair, 2006). On the other hand, some parents who have a child with hearing loss show negative reactions, such as hopelessness and depression (Aslani, Azkhosh, Movallali, Younesi & Salehy, 2014). These negative reactions raise the possibility that parents may neglect their child, which can lead to behavioral problems in the child (Damhari, Movallali & Ahmadi, 2015).

In recent decades, many studies have investigated aggression in children and adolescents. Some studies have indicated that some behavioral problems in deaf individuals may result from accompanying impairments, such as brain damage that leads to impulsive behaviors, aggression, and inability to establish successful relationships (O’Rourke & Reed, 2007). On the other hand, according to a study by Kentish (2007), many behavioral problems of deaf individuals are due to their problems in terms of Theory of Mind, i.e. the ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others. The inability to understand the feelings and thoughts of others can lead to aggressive and impulsive behaviors.

Mental health is an essential factor in the development of deaf adolescents in the face of future problems (World Health Organization, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation & University of Melbourne, 2005). Therefore, acquisition of age-appropriate skills and competencies, not only is important for a successful adaptation in the current stage of development of a child or adolescent but also can be a basis for the future improvement of necessary individual and social capabilities (Reinecke, Dattilio & Freeman, 2000). Life skills are among these necessary skills. It seems that life skills training is a useful technique in creating and enhancing capabilities, such as decision-making, self-motivation, responsibility, having successful relationships with others, creating positive self-esteem, and problem-solving (Srikala & Kishore Kumar, 2010).

Although few studies have directly explored self-esteem and aggression in deaf adolescents, some recent studies have shown the effectiveness of life skills training in this group. For example, Vatankhah, Daryabari, Ghadami & Khanjan Shoeibi (2014) showed the effectiveness of life skills training on the self-esteem and happiness of female students. In their study on aggression, Baghaei-Moghadam, Malekpour, Amiri & Mowlavi (2011) found the positive and significant effect of life skills training on a decrease in anxiety and an increase in happiness and anger management in this group of adolescents. In another study by Herman & Mcwhirter (2003), titled “The Effectiveness of Anger Management Training among Adolescents”, it was found that the training interventions significantly improved the ability of adolescents to control their anger. Rose, Loftus, Flint & Carey (2005), also examined the effectiveness of group intervention on anger management in adolescents with intellectual disabilities and found a reduction in aggressive behavior.

Therefore, given the debilitating nature of hearing loss and the mental health problems of deaf individuals who have a hidden disability, and also due to a lack of studies on self-esteem and aggression in the deaf population, it is necessary to take some measures to provide them with appropriate care and reduce their difficulties and mental health problems. Also, due to lower mental health in deaf adolescents and the lack of interventional studies on self- esteem and anger control of deaf adolescents and life skills training programs we conducted this study to examine the effectiveness of a life skills training program on improvement of the self-esteem and aggression control of deaf adolescent girls.

2. Methods

This research was a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test, post-test design and a control group.

Samples and sampling method

The statistical population included all the students of high schools for female students with hearing loss, in the west of Tehran, during the academic year 2014-2015. The study sample consisted of 34 female students with hearing loss (17 students in each group) who were selected using a purposive, convenience sampling method.

Instruments

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (AQ): This is a 29-item questionnaire developed by Buss and Perry (1992), assessing 4 aspects of aggression: physical aggression (2, 5, 8, 11, 13, 16, 22, 25, and 29), verbal aggression (4, 6, 14, 21, & 27), anger (1, 9, 12, 18, 19, 23, and 28), and hostility (3, 7, 10, 15, 17, 20, 24, and 26). The minimum and maximum scores on the AQ are 29 and 145, respectively. The total score for aggression is the sum of scores on subscales. Subscales represent different types of aggression. This questionnaire has high internal consistency. Buss and Perry (1992) found the internal consistency of the AQ to be .89. They also reported test-retest reliability of .80 for the AQ. In a study on 400 immigrant and nonimmigrant students, Langari (2008), also reported the construct validity of.45 (P<0.01) for AQ. Hoseinkhazadeh, et al. (2018), reported the reliability of.89 and .90 using the Cronbach’s alpha and the split-half method, respectively, which indicate good reliability of the questionnaire.

The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI): Coopersmith (1967) developed this inventory based on a revision of a scale designed by Rogers and Dymond (1954). The SEI has 58 items, including 8 lie detector items (6, 13, 20, 27, 34, 41, 48, and 55). It also has four subscales as follows: overall self-esteem (1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, 24, 29, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38, 43, 44, 45, 50, 51, 52, 57, and 58), social self-esteem (4, 11, 18, 25, 32, 39, 46, 53), academic self-esteem (7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56), and family self-esteem (5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40, 47, and 54). Items 2, 4, 5, 10, 14, 18, 19, 21, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 45, 47, and 57, are scored one for yes and zero for no. The remaining items are reversely scored.

The minimum and maximum scores on the SEI are 0 and 50, respectively. A score above 4 on the 8 lie detector items indicates the unreliability of the results and suggest a self-serving bias. The SEI was translated into Persian by Neisi and Yamini (2009). who also calculated its reliability and validity in the Iranian population. Based on the correlations between the scores on the SEI and the mean scores of 23 female and male students on the high school final exam, Moradi Shahrebabak et al. (2011) found the validity of the SEI to be .096 and .071 for boys and girls, respectively. They also found the test-retest reliability of the SEI to be 0.090 and 0.092, for boys and girls, respectively.

Procedure

This study was conducted on deaf adolescent girls, from a high school in the west of Tehran. We had a limitation to enter more high schools; thus, we randomly select one. First, the necessary permissions were obtained, and then a high school for female students was selected from the high schools located in the west of Tehran that had enough students for our study (maximum 50 students). For assessing self-esteem and anger, the SEI and the AQ were administered, respectively. Those who scored ≤26 on the SEI (indicating low self-esteem), ≥87 on the AQ, and had the following criteria were included in the study: deaf adolescent girls with profound hearing loss (based on their medical records in the school), the age of 15 to 18 years, no history of psychiatric disorders (based on the school counselor records), no history of drug abuse (based on the school records), willingness to participate in the study (based on the results of an interview with them), and written permission of parents and students for participation in the study.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: being absent for more than one session, unwillingness to continue the study process, and refusing to attend the training sessions. Ethical considerations were as follows: 1. voluntary participation of participants in the sessions of the group counseling program; 2. A clear explanation of the study objectives to participants; 3. assuring participants that they can leave the study at any time; 4. Making sure that participants complete the questionnaires willingly; 5. Appropriate planning for counseling sessions (so that it does not interfere with teacher activities and school programs); 6. Ensuring the confidentiality of the study data; 7. Arranging sessions for participants in the control group, after the end of the study (in two sessions, life skills are provided for the students, and they are informed about the whole study process; 8. Making sure that participants are informed about the study process (unless they give up their right to know about the process); 9. Making sure that the research procedure does not violate the religious and cultural values of participants and the society; 10. It is the researcher’s responsibility to provide the necessary information for participants (if someone else provides this information, it does not remove this responsibility); 11. Giving the study results to institutions and groups, with participants’ permission.

In the next step, the selected participants (n=34) were divided into two groups of 17 individuals (experimental and control). In the next step, an 8-session intervention was provided for the experimental group by the first author of this paper (a rehabilitation counselor). All the sessions were done using PowerPoints and visual resources (Table 1). We used many pictures in our PowerPoints plus explaining all of them with sign language (the school interpreter). We used the necessary role modelings and showed everything visually for them to ensure nothing is misunderstood. The control group received the typical education of high schools. Forty-eight hours after the end of the sessions, the study questionnaires were again administered to both groups. The study data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, and inferential statistics, including Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA). Before using the ANCOVA, the assumptions of this method, including the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (for assessing the normality of data) and the Levene’s test (for equality of variances) were examined.

3. Results

A total of 34 deaf adolescent girls participated in this study. The average age of participants was 15 years, with frequency rates of 41.2 for the experimental group, and 35.3 for the control group. In addition, the significance level calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test was above .05; therefore, there was no significant difference regarding age between the experimental and control groups.

Deafness is a relatively common problem with severe effects on all aspects of the general health of deaf adolescents that also creates high levels of stress for the families (Yang, Wei, Chai, Li & Wu, 2013). Almost 1-3 children out of 1000 are born with bilateral hearing loss worldwide and in Iran (Lotfi & Movallali, 2007). Also, 15%-26% of the world population has some types of hearing loss (Movallali, Torabi & Tavakoli, 2014), and this percentage is higher in less-developed countries (Agrawal, Platz & Niparko, 2008; Béria et al., 2007). More than 90% of deaf children are born in families with no history of hearing loss (Rostami, Younesi, Movallali, Farhood & Biglarian, 2014). Hearing loss can have important effects on the physical, psychological, and social health of adolescents, and may lead to low self-esteem, irritability, isolation, depression, and anxiety (Kushalnagar et al., 2007).

Examination of the psychological and social status of deaf adolescents and young adults has shown that low self-confidence, a sense of social insecurity, isolation, generalized anxiety, low motivation, depression, and situational and selective (toward those who are close to the person) aggression, are among the salient behavioral and personality characteristics of deaf individuals (Theunissen et al., 2011). Deaf adolescents are specially characterized by low self-esteem. According to a definition by Lawernce (2006), self-esteem is a person’s evaluation of his/her self-worth and refers to a person’s attitude toward himself/herself. People make these judgments based on an evaluation of their behavior, according to their standards and values, and by comparing their own performance with that of others.

Many deaf individuals, compared with their hearing peers, have lower levels of social interaction and self-assertiveness, which also affects their self-evaluation and self-esteem. Deaf individuals with higher self-esteem, learn more effectively, engage in more constructive relationships, make better use of opportunities, and are productive and self-sufficient (Goldestein & Morgan, 2002). Previous examinations have shown that low self-esteem is associated with mental health problems (Baumeister, Heatherton & Tice, 1993; Mousavi, Movallali & Mousavi Nare, 2017). In addition, longitudinal studies have shown that low self-esteem in adolescents, can solely predict their depression (Orth, Robins & Roberts, 2008) and anxiety (Trzesniewski et al., 2006). Previous studies on deaf children and adolescents have indicated that there is a negative relationship between general self-esteem and mental health problems (Mejstad, Heiling & Svedin, 2009; Hindley, Hill, McGuigan & Kitson, 1994).

Behavioral problems, especially aggression, are also common in deaf adolescents. Most studies have shown that aggression, compared with conduct problems, is less common in deaf children and adolescents (van Eldik, Treffers, Veerman & Verhulst, 2004). Deaf children and adolescents are significantly less likely than their peers to hide their aggression (Movallali & Imani, 2015). Due to their impairments in cognitive, social, and emotional skills, these adolescents tend to show more aggression than other students (Smith, 2010). Most of these individuals have many problems in social information processing and often upset their friends and acquaintances, due to their unawareness, selecting incorrect strategies, and being unable to do simple tasks, such as asking, discussing, and having a constructive conversation (Hallahan & Kuffman, 1994).

Deaf adolescents may misinterpret other people’s guidance, and attribute hostile intentions to others, especially in high-stress situations. Social skills problems in these adolescents often lead to poor impulse control and low frustration tolerance (Hintermair, 2006). On the other hand, some parents who have a child with hearing loss show negative reactions, such as hopelessness and depression (Aslani, Azkhosh, Movallali, Younesi & Salehy, 2014). These negative reactions raise the possibility that parents may neglect their child, which can lead to behavioral problems in the child (Damhari, Movallali & Ahmadi, 2015).

In recent decades, many studies have investigated aggression in children and adolescents. Some studies have indicated that some behavioral problems in deaf individuals may result from accompanying impairments, such as brain damage that leads to impulsive behaviors, aggression, and inability to establish successful relationships (O’Rourke & Reed, 2007). On the other hand, according to a study by Kentish (2007), many behavioral problems of deaf individuals are due to their problems in terms of Theory of Mind, i.e. the ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others. The inability to understand the feelings and thoughts of others can lead to aggressive and impulsive behaviors.

Mental health is an essential factor in the development of deaf adolescents in the face of future problems (World Health Organization, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation & University of Melbourne, 2005). Therefore, acquisition of age-appropriate skills and competencies, not only is important for a successful adaptation in the current stage of development of a child or adolescent but also can be a basis for the future improvement of necessary individual and social capabilities (Reinecke, Dattilio & Freeman, 2000). Life skills are among these necessary skills. It seems that life skills training is a useful technique in creating and enhancing capabilities, such as decision-making, self-motivation, responsibility, having successful relationships with others, creating positive self-esteem, and problem-solving (Srikala & Kishore Kumar, 2010).

Although few studies have directly explored self-esteem and aggression in deaf adolescents, some recent studies have shown the effectiveness of life skills training in this group. For example, Vatankhah, Daryabari, Ghadami & Khanjan Shoeibi (2014) showed the effectiveness of life skills training on the self-esteem and happiness of female students. In their study on aggression, Baghaei-Moghadam, Malekpour, Amiri & Mowlavi (2011) found the positive and significant effect of life skills training on a decrease in anxiety and an increase in happiness and anger management in this group of adolescents. In another study by Herman & Mcwhirter (2003), titled “The Effectiveness of Anger Management Training among Adolescents”, it was found that the training interventions significantly improved the ability of adolescents to control their anger. Rose, Loftus, Flint & Carey (2005), also examined the effectiveness of group intervention on anger management in adolescents with intellectual disabilities and found a reduction in aggressive behavior.

Therefore, given the debilitating nature of hearing loss and the mental health problems of deaf individuals who have a hidden disability, and also due to a lack of studies on self-esteem and aggression in the deaf population, it is necessary to take some measures to provide them with appropriate care and reduce their difficulties and mental health problems. Also, due to lower mental health in deaf adolescents and the lack of interventional studies on self- esteem and anger control of deaf adolescents and life skills training programs we conducted this study to examine the effectiveness of a life skills training program on improvement of the self-esteem and aggression control of deaf adolescent girls.

2. Methods

This research was a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test, post-test design and a control group.

Samples and sampling method

The statistical population included all the students of high schools for female students with hearing loss, in the west of Tehran, during the academic year 2014-2015. The study sample consisted of 34 female students with hearing loss (17 students in each group) who were selected using a purposive, convenience sampling method.

Instruments

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (AQ): This is a 29-item questionnaire developed by Buss and Perry (1992), assessing 4 aspects of aggression: physical aggression (2, 5, 8, 11, 13, 16, 22, 25, and 29), verbal aggression (4, 6, 14, 21, & 27), anger (1, 9, 12, 18, 19, 23, and 28), and hostility (3, 7, 10, 15, 17, 20, 24, and 26). The minimum and maximum scores on the AQ are 29 and 145, respectively. The total score for aggression is the sum of scores on subscales. Subscales represent different types of aggression. This questionnaire has high internal consistency. Buss and Perry (1992) found the internal consistency of the AQ to be .89. They also reported test-retest reliability of .80 for the AQ. In a study on 400 immigrant and nonimmigrant students, Langari (2008), also reported the construct validity of.45 (P<0.01) for AQ. Hoseinkhazadeh, et al. (2018), reported the reliability of.89 and .90 using the Cronbach’s alpha and the split-half method, respectively, which indicate good reliability of the questionnaire.

The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI): Coopersmith (1967) developed this inventory based on a revision of a scale designed by Rogers and Dymond (1954). The SEI has 58 items, including 8 lie detector items (6, 13, 20, 27, 34, 41, 48, and 55). It also has four subscales as follows: overall self-esteem (1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, 24, 29, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38, 43, 44, 45, 50, 51, 52, 57, and 58), social self-esteem (4, 11, 18, 25, 32, 39, 46, 53), academic self-esteem (7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56), and family self-esteem (5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40, 47, and 54). Items 2, 4, 5, 10, 14, 18, 19, 21, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 45, 47, and 57, are scored one for yes and zero for no. The remaining items are reversely scored.

The minimum and maximum scores on the SEI are 0 and 50, respectively. A score above 4 on the 8 lie detector items indicates the unreliability of the results and suggest a self-serving bias. The SEI was translated into Persian by Neisi and Yamini (2009). who also calculated its reliability and validity in the Iranian population. Based on the correlations between the scores on the SEI and the mean scores of 23 female and male students on the high school final exam, Moradi Shahrebabak et al. (2011) found the validity of the SEI to be .096 and .071 for boys and girls, respectively. They also found the test-retest reliability of the SEI to be 0.090 and 0.092, for boys and girls, respectively.

Procedure

This study was conducted on deaf adolescent girls, from a high school in the west of Tehran. We had a limitation to enter more high schools; thus, we randomly select one. First, the necessary permissions were obtained, and then a high school for female students was selected from the high schools located in the west of Tehran that had enough students for our study (maximum 50 students). For assessing self-esteem and anger, the SEI and the AQ were administered, respectively. Those who scored ≤26 on the SEI (indicating low self-esteem), ≥87 on the AQ, and had the following criteria were included in the study: deaf adolescent girls with profound hearing loss (based on their medical records in the school), the age of 15 to 18 years, no history of psychiatric disorders (based on the school counselor records), no history of drug abuse (based on the school records), willingness to participate in the study (based on the results of an interview with them), and written permission of parents and students for participation in the study.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: being absent for more than one session, unwillingness to continue the study process, and refusing to attend the training sessions. Ethical considerations were as follows: 1. voluntary participation of participants in the sessions of the group counseling program; 2. A clear explanation of the study objectives to participants; 3. assuring participants that they can leave the study at any time; 4. Making sure that participants complete the questionnaires willingly; 5. Appropriate planning for counseling sessions (so that it does not interfere with teacher activities and school programs); 6. Ensuring the confidentiality of the study data; 7. Arranging sessions for participants in the control group, after the end of the study (in two sessions, life skills are provided for the students, and they are informed about the whole study process; 8. Making sure that participants are informed about the study process (unless they give up their right to know about the process); 9. Making sure that the research procedure does not violate the religious and cultural values of participants and the society; 10. It is the researcher’s responsibility to provide the necessary information for participants (if someone else provides this information, it does not remove this responsibility); 11. Giving the study results to institutions and groups, with participants’ permission.

In the next step, the selected participants (n=34) were divided into two groups of 17 individuals (experimental and control). In the next step, an 8-session intervention was provided for the experimental group by the first author of this paper (a rehabilitation counselor). All the sessions were done using PowerPoints and visual resources (Table 1). We used many pictures in our PowerPoints plus explaining all of them with sign language (the school interpreter). We used the necessary role modelings and showed everything visually for them to ensure nothing is misunderstood. The control group received the typical education of high schools. Forty-eight hours after the end of the sessions, the study questionnaires were again administered to both groups. The study data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, and inferential statistics, including Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA). Before using the ANCOVA, the assumptions of this method, including the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (for assessing the normality of data) and the Levene’s test (for equality of variances) were examined.

3. Results

A total of 34 deaf adolescent girls participated in this study. The average age of participants was 15 years, with frequency rates of 41.2 for the experimental group, and 35.3 for the control group. In addition, the significance level calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test was above .05; therefore, there was no significant difference regarding age between the experimental and control groups.

Descriptive findings

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation of self-esteem and aggression in Pre-test and Post-test for both experimental and control groups. A comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem for the experimental group showed an increase in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem for both experimental and control groups indicated that the mean score of self-esteem was higher in the post-test and in the experimental group than the control group. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores of aggression for the experimental group indicated a decrease in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of aggression for both experimental and control groups indicated that the mean score of aggression was lower in the pre-test; however, it was still higher in the experimental group than the control group.

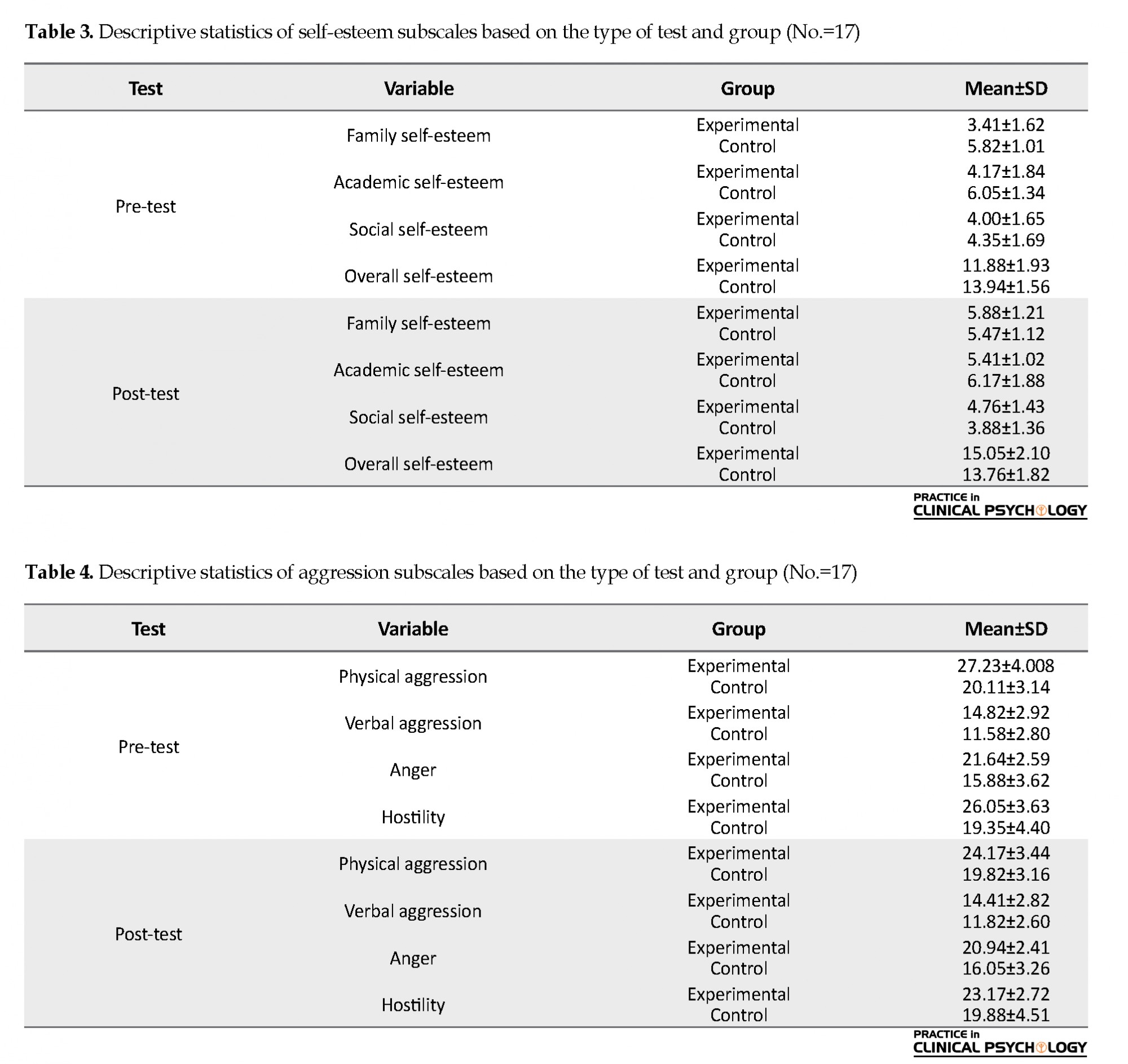

Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation of self-esteem subscales in pre-test and post-test for both experimental and control groups. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores of self-esteem showed an increase in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem subscales for both experimental and control groups, indicating that the mean scores on self-esteem subscales were higher in the post-test, and in the experimental group than the control group.

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation of self-esteem and aggression in Pre-test and Post-test for both experimental and control groups. A comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem for the experimental group showed an increase in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem for both experimental and control groups indicated that the mean score of self-esteem was higher in the post-test and in the experimental group than the control group. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores of aggression for the experimental group indicated a decrease in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of aggression for both experimental and control groups indicated that the mean score of aggression was lower in the pre-test; however, it was still higher in the experimental group than the control group.

Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation of self-esteem subscales in pre-test and post-test for both experimental and control groups. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores of self-esteem showed an increase in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of the Pre-test and Post-test mean scores of self-esteem subscales for both experimental and control groups, indicating that the mean scores on self-esteem subscales were higher in the post-test, and in the experimental group than the control group.

Table 4 shows the mean and standard deviation of aggression subscales in pre-test and post-test, for both experimental and control groups. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores of aggression for the experimental group indicated a decrease in Post-test scores. In other words, comparison of pre-test and Post-test mean scores of aggression subscales for both experimental and control groups indicated that the mean score of aggression subscales was lower in the Post-test; however, it was still higher in the experimental group than the control group.

Hypothesis 1

Life skills training can increase self-esteem in deaf adolescent girls.

Hypothesis 2

Life skills training can increase anger management in deaf adolescent girls.

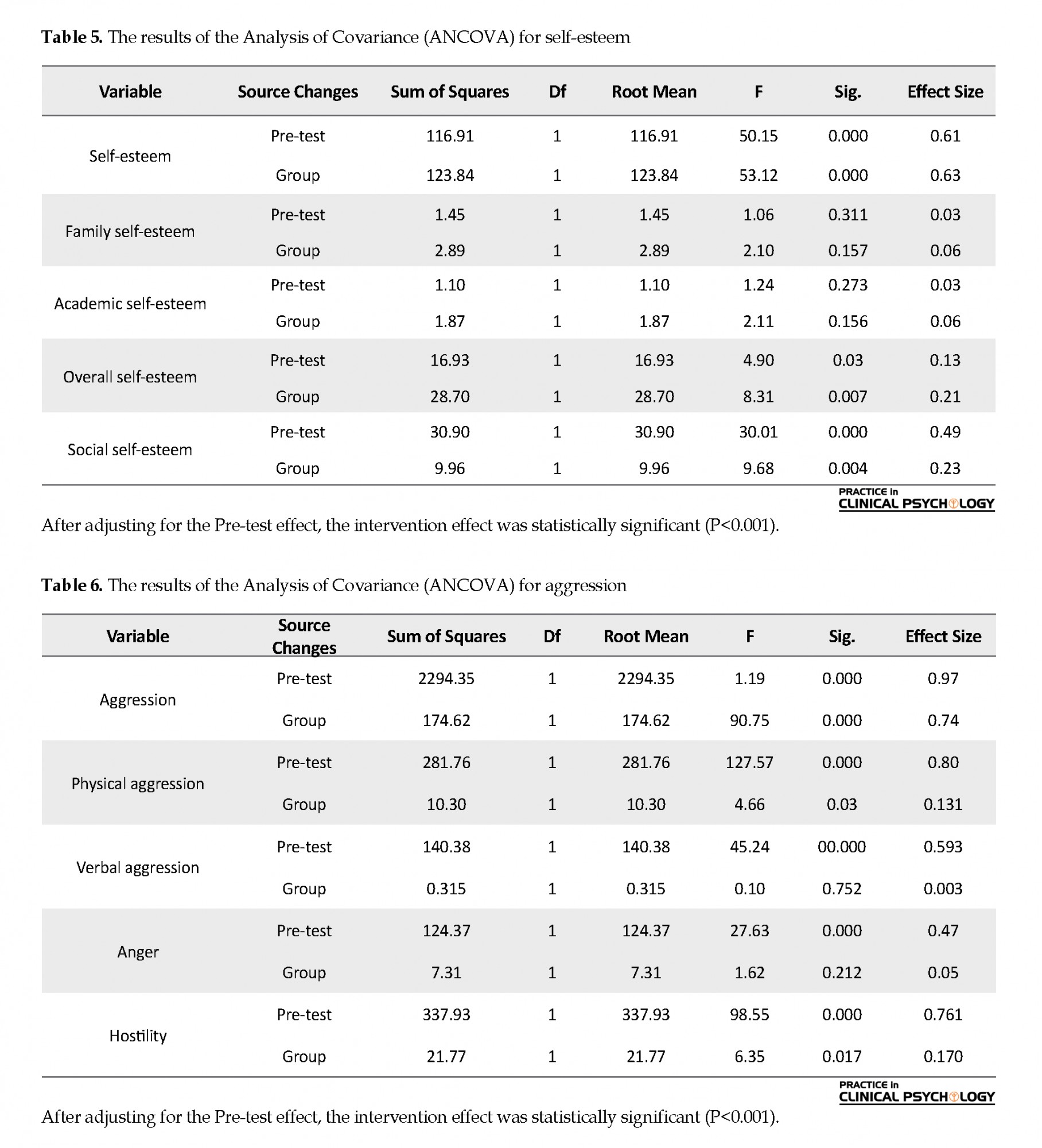

The ANCOVA was used to examine this hypothesis and self-esteem subscales. The results of the ANCOVA for aggression subscales are provided in Tables 5 and 6.

Hypothesis 1

Life skills training can increase self-esteem in deaf adolescent girls.

Hypothesis 2

Life skills training can increase anger management in deaf adolescent girls.

The ANCOVA was used to examine this hypothesis and self-esteem subscales. The results of the ANCOVA for aggression subscales are provided in Tables 5 and 6.

4. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of life skills training on the improvement of the self-esteem and anger management of deaf adolescent girls. Following a life skills training provided to deaf adolescent girls in eight sessions, we found an increase in the self-esteem scores and a decrease in the aggression scores in the participants. Given that the effect of self-esteem in the Pre-test was removed, we can argue that this difference can result from the intervention. In other words, because the life skills program was implemented to the experimental group, and the control group did not receive any training, we can conclude that this increase was due to the training program. Our findings regarding self-esteem are consistent with the results of some previous relevant studies. For example, regarding life skills training to students, Srikala & Kishore Kumar (2010) found an increase in positive social behavior, self-esteem, adjustment, and appropriate coping in school, especially in interaction with teachers. In a study on students with dyslexia, Kazemi, Momeni & Abolghasemi (2014) found the significant effect of life skills training on the enhancement of self-esteem and the general health of students. Ashoori, Jalilabkenar, Hasanzadeh, Tajrishi & Pourmohamadreza Tajrishi, (2012) showed that life skills training can improve the mental health of deaf students.

Our findings are also in line with some other studies, including a study by Sobhi-Gharamaleki & Rajabi (2010), showing the effectiveness of life skills training on the improvement of self-esteem and mental health of students, and another study by Mahvashe Vernosfaderani & Movallali (2013), reporting an increase in social skills due to life skills training. To explain these observations, it can be stated that by implementing life skills training through teaching clients about how to be satisfied with their lives, a significant increase is observed in their self-esteem. This means that it is possible to improve the self-esteem of clients, by helping them act according to their own behavioral standards in the important aspects of their lives. It seems that the most important factor affecting the self-esteem of individuals with hearing loss is relationship skills.

Relationship skills training not only empowers people in the present but also improves their abilities in the future. In the early stages of their social lives, if adolescents and young people are trained about relationship skills, this will be beneficial to families and society. This is due to the fact that these skills can improve the social and mental capabilities of individuals, and make them ready for an effective and productive life. Life skills training improves relationship skills; therefore, it can help individuals develop the ‘I am good, you are good’ attitude, and using this attitude, they can achieve high levels of life skills and self-worth (Prochasska & Norcross, 2008). In addition, group training can lead to positive feedback from peers and reinforcement of the right behavior (Kellner & Tutin, 1995).

We found a significant decrease in the aggression level of deaf adolescent girls after receiving relationship skills training. This finding is consistent with some previous studies. For example, in a previous study investigating the effect of life skills training on reducing the health-threatening symptoms, such as anxiety and depression in adolescents, Steger (2009) found that life skills training significantly reduced these symptoms. Baghaei-Moghadam et al. (2011) showed the effectiveness of life skills training on anxiety, happiness, and anger management of adolescents with sensory-motor disabilities. This study showed the significant effect of life skills training on a reduction in anxiety, and an increase in happiness and anger management of adolescents. In another study by Hoseinkhazadeh, et al. (2018) on the effectiveness of life skills training on the anxiety and aggression of students of the Islamic Azad University of Ilam, it was found that life skills training could significantly decrease anxiety and aggression. Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, Geravand & Arzi (2009) also showed that life skills training is effective in reducing anxiety and aggression in wives of martyrs.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that life skills training can teach a person about the concept and methods of anger management, self-assertiveness, and active listening, by which it can improve the hearing and useful social behaviors in them, help them know about the best ways to cope with stress, and enable them to control their aggression in their daily interactions. Life skills training includes teaching the most appropriate ways to manage emotions, develop interpersonal skills, and learn the problem-solving technique; this can also be effective in reducing aggressive behavior and improving adaptation (Carr, 2004). These skills can help students deal with problems more effectively and more logically, and use more effective ways for anger management.

The present study had some limitations, and the most important one was that the study sample included only female students; this was because of gender segregation in Iranian schools. It is recommended that future studies examine the effectiveness of life skills training for deaf individuals in other areas, including prevention and treatment of depression, test anxiety, mental health improvement, adjustment, academic progress, and coping with tension. In addition, because the study was conducted on a limited population (deaf adolescent girls), it is suggested that future studies focus on the effectiveness of life skills training on other disorders and in other populations in order to get more robust results in terms of the effects of life skills training on mental health and its treatment effects on other variables and mental disorders. It is also suggested that future studies compare life skills training with other treatment approaches. Given that the effect of social skills on self-esteem and anger management has been confirmed, it is suggested that educational packets and workshops focusing on life skills training should be designed for psychologists and social workers who work with deaf individuals, in order to take purposeful and positive steps toward serving people with disabilities.

5. Conclusion

According to the study results, life skills training can increase self-esteem and decrease the aggression of deaf adolescent girls. Therefore, the method used in the present study can be useful in designing psychological, educational, counseling, and treatment interventions for deaf adolescent girls, and it can be used in psychological and counseling clinics to prevent depression, and improve self-esteem and even academic progress of adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences approved th study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Department of Conselling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and methodology: All authors; Data collection and aata analysis: Pourya Reza Soltani, Arezoo Abedi, and Nasrin Sudmand; Writing – review & editing, and Writing – original draft: Guita Movallali, Mohammad Rostami and Asghar Dadkhah.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

Agrawal, Y., Platz, E. A., & Niparko, J. K. (2008). Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(14), 1522-30. [DOI:10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522] [PMID]

Ashoori, M., Jalilabkenar, S., Hasanzadeh, S., Tajrishi, M., & Pourmohamadreza Tajrishi, M. (2012). [The effectiveness of life skills training on the mental health of deaf students in inclusive schools (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation, 13(4), 48-57. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1226-fa.html

Aslani, L., Azkhosh, M., Movallali, G., Younesi, S. J., & Salehy, Z. (2014). The effectiveness of resiliency training program on the components of quality of life in mothers with hearing-impaired children. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4(3), 62-6. [DOI:10.9790/7388-04336266]

Baghaei-Moghadam, G., Malekpour, M., Amiri, S., & Mowlavi, H. (2011). [The effectiveness of life skills training on anxiety, happiness and anger control of adolescents with physical-motor disability (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 5(4), 305-10. http://www.behavsci.ir/article_67747.html

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1993). When ego threats lead to self regulation failure: Negative consequences of high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(1), 141-56. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.64.1.141] [PMID]

Béria, J. U., Raymann, B. C. W., Gigante, L. P., Figueiredo, A. C. L., Jotz, G., & Roithman, R., et al. (2007). Hearing impairment and socioeconomic factors: a population-based survey of an urban locality in southern Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública , 21(6), 381-7. [DOI:10.1590/S1020-49892007000500006] [PMID]

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452-9. [DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452]

Carr, A. (2004). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. 1st Ed. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203506035]

Coopersmith, S. The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, 1967. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10015560574/

Damhari, F., Movallali, G., & Ahmadi, V. (2015). [Examination of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas, self-concept, and behavioral problems among deaf adolescents and adolescents with visual impairment in Yazd city (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences, 23(4), 191-201. http://sjimu.medilam.ac.ir/article-1-2084-en.html

Goldestein, H., & Morgan, L. (2002). Social interaction and models of friendship development. In H. Goldstein, L. A. Kaczmarek, & K. M. English (Eds.), Communication and language intervention series; Vol. 10. Promoting social communication: Children with developmental disabilities from birth to adolescence (pp. 5-25). Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-18856-001

Hallahan, D. P., & Kuffman, J. M. (1994). Exceptional children: Introduction to special education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. https://books.google.com/books?id=5VQUDQEACAAJ&dq

Herman, D. S., & Mcwhirter, J. J. (2003). Anger and aggression management in young adolescents: An experimental validation of the SCARE program. Education and Treatment of Children, 26(3), 273-302. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42899754?seq=1

Hindley, P. A., Hill, P. D., McGuigan, S., & Kitson, N. (1994). Psychiatric disorder in deaf and hearing impaired children and young people: A prevalence study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(5), 917-34. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02302.x] [PMID]

Hintermair, M. (2006). Parental resources, parental stress, and socioemotional development of deaf and hard of hearing children. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(4), 493-513. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl005

Hoseinkhazadeh, A., Amoseni, D., Asghari, F., & Mohammadi, H. (2018). [Effectiveness of Teaching Self-Control Abilities on Reducing Aggression in Students with Aggressive Behaviors (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 7(4), 107-36. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-279-fa.html

Kazemi, R., Momeni, S., & Abolghasemi, A. (2014). The effectiveness of life skill training on self-esteem and communication skills of students with dyscalculia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 863-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.798]

Kellner, M. H., & Tutin, J. (1995). A school-based anger management program for developmentally and emotionally disabled high school students. Adolescence, 30(120), 813-25. [PMID]

Kentish, R. (2007). Challenging behavior in the young deaf child. In S. Austen, & D. Jeffery, (Eds.), Deafness and challenging behavior: The 360° perspective (pp. 75-88). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://books.google.com/books?id=k_eW7_MBDY0C&dq

Kushalnagar, P., Krull, K., Hannay, J., Metha, P., Caudle, S., & Oghalai, J. (2007). Intelligence, parental depression, and behavior adaptability in deaf children being considered for cochlear implantation. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 12(3), 335-49. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enm006] [PMID]

Lawrence, D. (2006). Enhancing self-esteem in the classroom. Newbury Park: Pine Forge Press. https://books.google.nl/books?id=ovCaRs1hHOEC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Enhancing+Self-esteem+in+the+Classroom&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjIiO2Pyp3tAhUP-aQKHUpAAvAQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=Enhancing%20Self-esteem%20in%20the%20Classroom&f=false

Langari M. [Comparison of aggression of immigrant and non-immigrant male students in the first year of high school in Bojnourd academic year 1998-1998 (Persian)]. [MA. thesis].Tehran: Tehran Teacher Training University; 2008. https://elmnet.ir/article/10070128-22113/1378-1377

Lotfi, Y., & Movallali, G. (2007). A universal newborn hearing screening in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 5(1), 8-11. http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-14-en.html

Neisi, S., Yamini, M. (2009). "The relationship between self-esteem and motivation for success and anxiety in foreign language classes with students' performance in English lessons". Journal of Psychological Achievements, 16(2),153-66. https://psychac.scu.ac.ir/article_11602.html?lang=en

Mahvashe Vernosfaderani, A., & Movallali, G. (2013). The effectiveness of life skills training in hearing impaired students for the reduction of social phobia. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 1(2), 105-10. http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-44-en.html

Mejstad, L., Heiling, K., & Svedin, C. G. (2009). Mental health and self-image among deaf and hard of hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf, 153(5), 504-15. [DOI:10.1353/aad.0.0069] [PMID]

Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., Geravand, L., & Arzi, S. (2009). [The effect of life skills training on the anxiety and aggression of martyrs wives (Persian)]. Woman and Culture, 1(1), 3-16. http://jwc.iauahvaz.ac.ir/article_522974.html

Moradei Shahrebabak, F., Ghanbari Hashemabad, B. A., & Aghamohmmdeian Sherbaf, H.R. (2011). [The survey of Effectiveness of the treatment Reality Therapy in group way to increase students' self-esteem, Ferdosei University of Mashhad (Persian)]. Studies in Education and Psychology, 11 (2), 227-38. https://www.magiran.com/paper/835607

Movallali, G., & Imani, M. (2015). [Emotional development in deaf children: Facial expression, emotional understanding, display rules, mixed emotions, and theory of mind (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(6), 1-16. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=5106&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Movallali, G., Torabi, F., & Tavakoli, E. (2014). [Behavioral problems in deaf individuals: A literature review (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(5), 14-26. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/article-1-5101-en.html

Mousavi, S. Z., Movallali, G., & Mousavi Nare, N. (2017). Adolescents with deafness: A review of self-esteem and its components. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 26(3), 125-37. https://avr.tums.ac.ir/index.php/avr/article/view/193

O’Rourke, S., & Reed, R. (2007). Deaf people and the criminal justice system. In S. Austen, & D. Jeffery, (Eds.), Deafness and challenging behavior: The 360° perspective (pp. 257-274). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://books.google.com/books?id=k_eW7_MBDY0C&dq

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Roberts, B. W. (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 695-708. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695] [PMID]

Prochasska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2008). Systems of psychotherapy : A transtheoretical analysis [Y. Seyed Mohammadi, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Ravan. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/1514628

Rostami, M., Younesi, S. J., Movallali, G., Farhood, D., & Biglarian, A. (2014). [The effectiveness of mental rehabilitation based on positive thinking skills training on increasing happiness in hearing impaired adolescents (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(3), 39-45. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/article-1-5043-en.html

Reinecke, M. A., Dattilio, F. M., & Freeman, A. M. (2000). Cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: A casebook for clinical practice [J. Alaghband Rad, H. Farahi, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Boghe. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/607237

Rogers, C. R., & Dymond, R. F. (1954). Psychotherapy and personality change. University of Chicago Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1955-04163-000

Rose, J., Loftus, M., Flint, B., & Carey, L. (2005). Factors associated with the efficacy of a group intervention for anger in people with intellectual disabilities. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 3), 305-17. [DOI:10.1348/014466505X29972] [PMID]

Smith, C. M. (2010). An analysis of the assessment and treatment of problematic and offending behaviors in the deaf population [PhD. dissertation]. Birmingham: University of Birmingham. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/1132/1/Smith10ForenPsyD.pdf

Srikala, B., & Kishore Kumar, K. V. (2010). Empowering adolescents with life skills education in schools-school mental health program: Does it work?. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 344-9. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.74310] [PMID] [PMCID]

Steger, M. F. (2009). Meaning in life. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. Oxford handbook of positive psychology (p. 679–687). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-05143-064

Sobhi-Gharamaleki, N., & Rajabi, S. (2010). Efficacy of life skills training on increase of mental health and self esteem of the students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1818-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.370]

Theunissen, S. C. P. M., Rieffe, C., Kouwenberg, M., Soede, W., Briaire, J. J., & Frijns, J. H. M. (2011). Depression in hearing- impaired children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 75(10), 1313-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.07.023] [PMID]

Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., Moffitt, T. E., Robins, R. W., Poulton, R., & Caspi, A. (2006). Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 381-90. [DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381] [PMID]

Vatankhah, H., Daryabari, D., Ghadami, V., & Khanjan Shoeibi, E. (2014). Teaching how life skills (anger control) affect the happiness and self-esteem of Tonekabon female students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 123-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.178]

van Eldik, T., Treffers, P. D. A., Veerman, J. W., & Verhulst, F.C. (2004). Mental health problems of deaf Dutch children as indicated by parents’ responses to the child behavior checklist. American Annals of the Deaf, 148(5), 390-5. [DOI:10.1353/aad.2004.0002] [PMID]

World Health Organization, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, University of Melbourne. (2005). Promoting mental health; concepts, emerging evidence and practice. Retrievedfrom https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/promoting_mh_2005/en/

Yang, T., Wei, X., Chai, Y., Li, L., & Wu, H. (2013). Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 8, 85. [DOI:10.1186/1750-1172-8-85] [PMID] [PMCID]

The goal of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of life skills training on the improvement of the self-esteem and anger management of deaf adolescent girls. Following a life skills training provided to deaf adolescent girls in eight sessions, we found an increase in the self-esteem scores and a decrease in the aggression scores in the participants. Given that the effect of self-esteem in the Pre-test was removed, we can argue that this difference can result from the intervention. In other words, because the life skills program was implemented to the experimental group, and the control group did not receive any training, we can conclude that this increase was due to the training program. Our findings regarding self-esteem are consistent with the results of some previous relevant studies. For example, regarding life skills training to students, Srikala & Kishore Kumar (2010) found an increase in positive social behavior, self-esteem, adjustment, and appropriate coping in school, especially in interaction with teachers. In a study on students with dyslexia, Kazemi, Momeni & Abolghasemi (2014) found the significant effect of life skills training on the enhancement of self-esteem and the general health of students. Ashoori, Jalilabkenar, Hasanzadeh, Tajrishi & Pourmohamadreza Tajrishi, (2012) showed that life skills training can improve the mental health of deaf students.

Our findings are also in line with some other studies, including a study by Sobhi-Gharamaleki & Rajabi (2010), showing the effectiveness of life skills training on the improvement of self-esteem and mental health of students, and another study by Mahvashe Vernosfaderani & Movallali (2013), reporting an increase in social skills due to life skills training. To explain these observations, it can be stated that by implementing life skills training through teaching clients about how to be satisfied with their lives, a significant increase is observed in their self-esteem. This means that it is possible to improve the self-esteem of clients, by helping them act according to their own behavioral standards in the important aspects of their lives. It seems that the most important factor affecting the self-esteem of individuals with hearing loss is relationship skills.

Relationship skills training not only empowers people in the present but also improves their abilities in the future. In the early stages of their social lives, if adolescents and young people are trained about relationship skills, this will be beneficial to families and society. This is due to the fact that these skills can improve the social and mental capabilities of individuals, and make them ready for an effective and productive life. Life skills training improves relationship skills; therefore, it can help individuals develop the ‘I am good, you are good’ attitude, and using this attitude, they can achieve high levels of life skills and self-worth (Prochasska & Norcross, 2008). In addition, group training can lead to positive feedback from peers and reinforcement of the right behavior (Kellner & Tutin, 1995).

We found a significant decrease in the aggression level of deaf adolescent girls after receiving relationship skills training. This finding is consistent with some previous studies. For example, in a previous study investigating the effect of life skills training on reducing the health-threatening symptoms, such as anxiety and depression in adolescents, Steger (2009) found that life skills training significantly reduced these symptoms. Baghaei-Moghadam et al. (2011) showed the effectiveness of life skills training on anxiety, happiness, and anger management of adolescents with sensory-motor disabilities. This study showed the significant effect of life skills training on a reduction in anxiety, and an increase in happiness and anger management of adolescents. In another study by Hoseinkhazadeh, et al. (2018) on the effectiveness of life skills training on the anxiety and aggression of students of the Islamic Azad University of Ilam, it was found that life skills training could significantly decrease anxiety and aggression. Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, Geravand & Arzi (2009) also showed that life skills training is effective in reducing anxiety and aggression in wives of martyrs.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that life skills training can teach a person about the concept and methods of anger management, self-assertiveness, and active listening, by which it can improve the hearing and useful social behaviors in them, help them know about the best ways to cope with stress, and enable them to control their aggression in their daily interactions. Life skills training includes teaching the most appropriate ways to manage emotions, develop interpersonal skills, and learn the problem-solving technique; this can also be effective in reducing aggressive behavior and improving adaptation (Carr, 2004). These skills can help students deal with problems more effectively and more logically, and use more effective ways for anger management.

The present study had some limitations, and the most important one was that the study sample included only female students; this was because of gender segregation in Iranian schools. It is recommended that future studies examine the effectiveness of life skills training for deaf individuals in other areas, including prevention and treatment of depression, test anxiety, mental health improvement, adjustment, academic progress, and coping with tension. In addition, because the study was conducted on a limited population (deaf adolescent girls), it is suggested that future studies focus on the effectiveness of life skills training on other disorders and in other populations in order to get more robust results in terms of the effects of life skills training on mental health and its treatment effects on other variables and mental disorders. It is also suggested that future studies compare life skills training with other treatment approaches. Given that the effect of social skills on self-esteem and anger management has been confirmed, it is suggested that educational packets and workshops focusing on life skills training should be designed for psychologists and social workers who work with deaf individuals, in order to take purposeful and positive steps toward serving people with disabilities.

5. Conclusion

According to the study results, life skills training can increase self-esteem and decrease the aggression of deaf adolescent girls. Therefore, the method used in the present study can be useful in designing psychological, educational, counseling, and treatment interventions for deaf adolescent girls, and it can be used in psychological and counseling clinics to prevent depression, and improve self-esteem and even academic progress of adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences approved th study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Department of Conselling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and methodology: All authors; Data collection and aata analysis: Pourya Reza Soltani, Arezoo Abedi, and Nasrin Sudmand; Writing – review & editing, and Writing – original draft: Guita Movallali, Mohammad Rostami and Asghar Dadkhah.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

Agrawal, Y., Platz, E. A., & Niparko, J. K. (2008). Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(14), 1522-30. [DOI:10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522] [PMID]

Ashoori, M., Jalilabkenar, S., Hasanzadeh, S., Tajrishi, M., & Pourmohamadreza Tajrishi, M. (2012). [The effectiveness of life skills training on the mental health of deaf students in inclusive schools (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation, 13(4), 48-57. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1226-fa.html

Aslani, L., Azkhosh, M., Movallali, G., Younesi, S. J., & Salehy, Z. (2014). The effectiveness of resiliency training program on the components of quality of life in mothers with hearing-impaired children. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4(3), 62-6. [DOI:10.9790/7388-04336266]

Baghaei-Moghadam, G., Malekpour, M., Amiri, S., & Mowlavi, H. (2011). [The effectiveness of life skills training on anxiety, happiness and anger control of adolescents with physical-motor disability (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 5(4), 305-10. http://www.behavsci.ir/article_67747.html

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1993). When ego threats lead to self regulation failure: Negative consequences of high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(1), 141-56. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.64.1.141] [PMID]

Béria, J. U., Raymann, B. C. W., Gigante, L. P., Figueiredo, A. C. L., Jotz, G., & Roithman, R., et al. (2007). Hearing impairment and socioeconomic factors: a population-based survey of an urban locality in southern Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública , 21(6), 381-7. [DOI:10.1590/S1020-49892007000500006] [PMID]

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452-9. [DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452]

Carr, A. (2004). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. 1st Ed. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203506035]

Coopersmith, S. The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, 1967. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10015560574/

Damhari, F., Movallali, G., & Ahmadi, V. (2015). [Examination of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas, self-concept, and behavioral problems among deaf adolescents and adolescents with visual impairment in Yazd city (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences, 23(4), 191-201. http://sjimu.medilam.ac.ir/article-1-2084-en.html

Goldestein, H., & Morgan, L. (2002). Social interaction and models of friendship development. In H. Goldstein, L. A. Kaczmarek, & K. M. English (Eds.), Communication and language intervention series; Vol. 10. Promoting social communication: Children with developmental disabilities from birth to adolescence (pp. 5-25). Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-18856-001

Hallahan, D. P., & Kuffman, J. M. (1994). Exceptional children: Introduction to special education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. https://books.google.com/books?id=5VQUDQEACAAJ&dq

Herman, D. S., & Mcwhirter, J. J. (2003). Anger and aggression management in young adolescents: An experimental validation of the SCARE program. Education and Treatment of Children, 26(3), 273-302. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42899754?seq=1

Hindley, P. A., Hill, P. D., McGuigan, S., & Kitson, N. (1994). Psychiatric disorder in deaf and hearing impaired children and young people: A prevalence study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(5), 917-34. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02302.x] [PMID]

Hintermair, M. (2006). Parental resources, parental stress, and socioemotional development of deaf and hard of hearing children. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(4), 493-513. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl005

Hoseinkhazadeh, A., Amoseni, D., Asghari, F., & Mohammadi, H. (2018). [Effectiveness of Teaching Self-Control Abilities on Reducing Aggression in Students with Aggressive Behaviors (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 7(4), 107-36. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-279-fa.html

Kazemi, R., Momeni, S., & Abolghasemi, A. (2014). The effectiveness of life skill training on self-esteem and communication skills of students with dyscalculia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 863-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.798]

Kellner, M. H., & Tutin, J. (1995). A school-based anger management program for developmentally and emotionally disabled high school students. Adolescence, 30(120), 813-25. [PMID]

Kentish, R. (2007). Challenging behavior in the young deaf child. In S. Austen, & D. Jeffery, (Eds.), Deafness and challenging behavior: The 360° perspective (pp. 75-88). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://books.google.com/books?id=k_eW7_MBDY0C&dq

Kushalnagar, P., Krull, K., Hannay, J., Metha, P., Caudle, S., & Oghalai, J. (2007). Intelligence, parental depression, and behavior adaptability in deaf children being considered for cochlear implantation. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 12(3), 335-49. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enm006] [PMID]

Lawrence, D. (2006). Enhancing self-esteem in the classroom. Newbury Park: Pine Forge Press. https://books.google.nl/books?id=ovCaRs1hHOEC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Enhancing+Self-esteem+in+the+Classroom&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjIiO2Pyp3tAhUP-aQKHUpAAvAQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=Enhancing%20Self-esteem%20in%20the%20Classroom&f=false

Langari M. [Comparison of aggression of immigrant and non-immigrant male students in the first year of high school in Bojnourd academic year 1998-1998 (Persian)]. [MA. thesis].Tehran: Tehran Teacher Training University; 2008. https://elmnet.ir/article/10070128-22113/1378-1377

Lotfi, Y., & Movallali, G. (2007). A universal newborn hearing screening in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 5(1), 8-11. http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-14-en.html

Neisi, S., Yamini, M. (2009). "The relationship between self-esteem and motivation for success and anxiety in foreign language classes with students' performance in English lessons". Journal of Psychological Achievements, 16(2),153-66. https://psychac.scu.ac.ir/article_11602.html?lang=en

Mahvashe Vernosfaderani, A., & Movallali, G. (2013). The effectiveness of life skills training in hearing impaired students for the reduction of social phobia. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 1(2), 105-10. http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-44-en.html

Mejstad, L., Heiling, K., & Svedin, C. G. (2009). Mental health and self-image among deaf and hard of hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf, 153(5), 504-15. [DOI:10.1353/aad.0.0069] [PMID]

Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., Geravand, L., & Arzi, S. (2009). [The effect of life skills training on the anxiety and aggression of martyrs wives (Persian)]. Woman and Culture, 1(1), 3-16. http://jwc.iauahvaz.ac.ir/article_522974.html

Moradei Shahrebabak, F., Ghanbari Hashemabad, B. A., & Aghamohmmdeian Sherbaf, H.R. (2011). [The survey of Effectiveness of the treatment Reality Therapy in group way to increase students' self-esteem, Ferdosei University of Mashhad (Persian)]. Studies in Education and Psychology, 11 (2), 227-38. https://www.magiran.com/paper/835607

Movallali, G., & Imani, M. (2015). [Emotional development in deaf children: Facial expression, emotional understanding, display rules, mixed emotions, and theory of mind (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(6), 1-16. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=5106&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Movallali, G., Torabi, F., & Tavakoli, E. (2014). [Behavioral problems in deaf individuals: A literature review (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(5), 14-26. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/article-1-5101-en.html

Mousavi, S. Z., Movallali, G., & Mousavi Nare, N. (2017). Adolescents with deafness: A review of self-esteem and its components. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 26(3), 125-37. https://avr.tums.ac.ir/index.php/avr/article/view/193

O’Rourke, S., & Reed, R. (2007). Deaf people and the criminal justice system. In S. Austen, & D. Jeffery, (Eds.), Deafness and challenging behavior: The 360° perspective (pp. 257-274). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://books.google.com/books?id=k_eW7_MBDY0C&dq

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Roberts, B. W. (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 695-708. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695] [PMID]

Prochasska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2008). Systems of psychotherapy : A transtheoretical analysis [Y. Seyed Mohammadi, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Ravan. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/1514628

Rostami, M., Younesi, S. J., Movallali, G., Farhood, D., & Biglarian, A. (2014). [The effectiveness of mental rehabilitation based on positive thinking skills training on increasing happiness in hearing impaired adolescents (Persian)]. Audiology, 23(3), 39-45. https://aud.tums.ac.ir/article-1-5043-en.html

Reinecke, M. A., Dattilio, F. M., & Freeman, A. M. (2000). Cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: A casebook for clinical practice [J. Alaghband Rad, H. Farahi, Persian Trans]. Tehran: Boghe. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/607237

Rogers, C. R., & Dymond, R. F. (1954). Psychotherapy and personality change. University of Chicago Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1955-04163-000

Rose, J., Loftus, M., Flint, B., & Carey, L. (2005). Factors associated with the efficacy of a group intervention for anger in people with intellectual disabilities. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 3), 305-17. [DOI:10.1348/014466505X29972] [PMID]

Smith, C. M. (2010). An analysis of the assessment and treatment of problematic and offending behaviors in the deaf population [PhD. dissertation]. Birmingham: University of Birmingham. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/1132/1/Smith10ForenPsyD.pdf

Srikala, B., & Kishore Kumar, K. V. (2010). Empowering adolescents with life skills education in schools-school mental health program: Does it work?. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 344-9. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.74310] [PMID] [PMCID]

Steger, M. F. (2009). Meaning in life. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. Oxford handbook of positive psychology (p. 679–687). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-05143-064

Sobhi-Gharamaleki, N., & Rajabi, S. (2010). Efficacy of life skills training on increase of mental health and self esteem of the students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1818-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.370]

Theunissen, S. C. P. M., Rieffe, C., Kouwenberg, M., Soede, W., Briaire, J. J., & Frijns, J. H. M. (2011). Depression in hearing- impaired children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 75(10), 1313-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.07.023] [PMID]

Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., Moffitt, T. E., Robins, R. W., Poulton, R., & Caspi, A. (2006). Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 381-90. [DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381] [PMID]

Vatankhah, H., Daryabari, D., Ghadami, V., & Khanjan Shoeibi, E. (2014). Teaching how life skills (anger control) affect the happiness and self-esteem of Tonekabon female students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 123-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.178]

van Eldik, T., Treffers, P. D. A., Veerman, J. W., & Verhulst, F.C. (2004). Mental health problems of deaf Dutch children as indicated by parents’ responses to the child behavior checklist. American Annals of the Deaf, 148(5), 390-5. [DOI:10.1353/aad.2004.0002] [PMID]

World Health Organization, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, University of Melbourne. (2005). Promoting mental health; concepts, emerging evidence and practice. Retrievedfrom https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/promoting_mh_2005/en/

Yang, T., Wei, X., Chai, Y., Li, L., & Wu, H. (2013). Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 8, 85. [DOI:10.1186/1750-1172-8-85] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Rehabilitation

Received: 2019/07/20 | Accepted: 2020/07/4 | Published: 2020/07/1

Received: 2019/07/20 | Accepted: 2020/07/4 | Published: 2020/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |