Volume 5, Issue 4 (Autumn 2017-- 2017)

PCP 2017, 5(4): 251-262 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hossein Khanzadeh A A, Imankhah F. The Effect of Music Therapy Along With Play Therapy on Social Behaviors and Stereotyped Behaviors of Children With Autism. PCP 2017; 5 (4) :251-262

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-355-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-355-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran. , abbaskhanzade@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Rasht Branch, Islamic Azad University, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Rasht Branch, Islamic Azad University, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 571 kb]

(6779 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (15845 Views)

Full-Text: (11749 Views)

1. Introduction

Autism is a complex neurobehavioral condition, which could be mild to severe, and generally has many associated symptoms. These symptoms are categorized into three classes: A. Abnormal social interaction; B. Abnormal verbal and nonverbal communication; and C. Stereotyped and rigid patterns of behavior and interests (Staal, 2015).

Excessive concern over various parts of the body (Rodrigues, Goncalves, Costa, & Soares, 2013), damaging qualitative experience in communication and social interaction (America Psychiatric Association, 2013; Gilley & Ringdahl, 2014), and poor academic achievement and job performance are other features of children with autism (Nader Grosbois & Day, 2011).

Difficulties and delay in social interaction are often the earliest features in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but they can be subtle and easily missed. In contrast to those with specific language disorders, children with ASD often fail to use gestures or mime to compensate. An individual with ASD often struggles to engage in social chat and build on conversation about someone else’s hobby or interest (Yates, & Le Couteur, 2016). Due to the nature of these impairments, students with autism exhibit significant challenges that require intensive support from both school and home. ASD can cause unique series of stressors including social isolation and stigma, difficulties in obtaining treatment, comorbid medical conditions, problems in sustaining employment, financial burden, and an unclear prognosis for family (Hillman, 2007).

Worldwide the prevalence of ASD is increasing. In some recent studies, the rate of ASD exceeds 1% the latest report made by the US CDC; ASD has been diagnosed in approximately 1 out of 88 children (Huang et al., 2014). In 2012, the prevalence of ASD in Iran was estimated at around 6.6 in 10,000 children (Samadi, Mahmoodizadeh, & McConkey, 2011). Children with autism experience fear of performing activities with friends, which is another limitation that these children need to correct (Sanrattana, Maneerat, & Srevisate, 2014). It does not necessarily mean that children with autism do not have a friendly interaction with others. In fact, most of them have a strong attachment to family members and friends; however, they are unable to establish a bilateral relationship with their peers and parents (Yacos, 2014).

In other words, social skills including complex cognitive and behavioral interactions such as identifying and interpreting social accuracy and considering the context and assessment of others’ behavior by paying attention to the responses of others are associated with many limitations in these children (O’Reilly et al., 2014). This reduction in establishing social communication of children with autism stems from the disorder of the theory of mind or understanding mental states of our social situations and others’ mental life (Hoogenhout & Malcolm-Smith, 2014).

Children with autism show less flexibility than their growing peers in response to “Penny-Hiding Games” (Murray & Healy, 2015) and pay less attention to and behave more stereotypically than the children of same age while playing games (America Psychological Association, 2013; Lang, Regester, Rispoli, Pimentel, & Camargo, 2010). The type, frequency, and intensity of stereotyped behaviors of children with ASD are widely different, but mostly they remain over the course of the time and will be the strongest predictor of early diagnosis of ASD, and if these behaviors are prevented, anxiety, protest, aggression, and self injury will occur (King et al., 2009).

To help children with autism, on-time and appropriate therapy are strongly recommended after the diagnosis of ASD. Art therapy develops a flexible attitude in children with autism and solves problems in the two areas of social–communicational and restricted–stereotyped behaviors (Schweizer, Knorth, & Spreen, 2014). Research has shown that MT facilitates the skill in areas that affect ASD and increases social interaction and communication skills (Geretsegger, Holck, & Gold, 2012) and facilitating speech development such as the ability to establish and maintain relationships in short periods of time (Groß, Linden, & Ostermann, 2010).

In addition, music has a positive therapeutic effect on communication development, personal and interpersonal responsibility, and playing skills (Schwartzberg & Silverman, 2013; Simpson & Keen, 2011; Whipple, 2012). Since stereotyped behaviors appear in the absence of social consequences, using auditory–vocal stimuli especially music is effective as an automatic reinforcement for these children (Saylor, Sidener, Reeve, Fetherston, & Progar, 2012). The use of music and music-based games improve, delay, and restrict non-musical background of children with autism (Reschke-Hernandez, 2011). Lanovaz, Sladeczek, and Rapp (2011), Lanovaz, Rap, and Ferguson (2012), and Saylor, et al. (2012) examined the impact of music on vocal stereotyped behaviors of children with autism and found that non-random access to auditory stimulation (e.g. music and audio produced using toys) immediately decreases vocal stereotyped behaviors in these children.

In addition, James et al. (2015) and Simpson, Keen, and Lamb (2013) in their research on the effect of MT on people with autism found that MT effectively decreased undesirable behaviors, promoted social interactions, and increased communication. In addition to the aforementioned strategy, compared to using only one method of treatment, the application of a mixture of music and play that includes playing, movement, and singing with music along with using a playing equipment increases eye contact and social interaction and decreases isolation, gaze aversion, and avoidance behaviors in children with ASD (Whipple, 2012). Furthermore, playing games with children with autism decreases their stereotyped behaviors and other behavioral problems (Koegel, Firestone, Kramme, & Dunlap, 1974; Lang et al., 2014).

Because flexible, social, and imaginative qualities are underdeveloped in children with autism, PT can change their playing methods and provide an opportunity to interact with others (Lu, Petersen, Lacroix, & Rousseau, 2010). Playing, by providing response interruption and redirection, causes displacement and reduction of stereotyped behaviors (Martinez & Betz, 2013). Koegel, Singh, and Koegel (2010) found that there is an inverse relationship between self-stimulation and appropriate game. In fact, using children’s favorite objects is one of the methods to deal with self-stimulation. Lang et al., (2014) and Lu et al. (2010) found that playing with toys during behavioral intervention decreased stereotyped behaviors and that children with autism acted better and happier after behavioral interventions. Furthermore, PT leads to an increase in verbal expression, engagement, and sustained social interaction.

Considering the potentiality of MT and PT in sensory excitement and inciting child’s senses and the role of these two approaches in improving communication, lack of sufficient knowledge in this area, and the fact that previous studies focused individually on these two approaches, in this study, we investigated the effects of MT and PT simultaneously. Therefore, keeping in mind treatment priorities in children with autism, in this study, we focused on to increase SBs and decrease stereotyped behaviors by applying MT and PT. Today, PT and MT are optional methods of therapy and have priority over other therapeutic approaches. Previous studies have recommended that integrating these two approaches can effectively increase SB and decease stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to find out whether training children with autism by using PT with MT leads to increase in appropriate SBs and decrease inappropriate stereotyped behaviors.

2. Methods

In this experimental study, a pre-test–post-test control group design was used. The statistical population of this study consisted of children with autism between the ages of 6 to 12 years living in Rasht, Iran during the 2014–15 educational year.

A total of 30 children qualified for the study were selected using convenient sampling procedure and were assigned to control and experimental groups randomly. The participants of this study were selected based on some criteria. Participants in both groups had no experience in participating in MT along with PT interventions. To ensure that participants had IQ between 50 and 70, IQ test was administered. Before conducting the research, diagnosis of autism was conducted according to the diagnostic criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) (5th edition).

Considering the standardization that was conducted in the Gilliam’s diagnostic exam of autism guide (Ahmadi, Safari, Hemmatiyan, & Kalili, 2011), the grades of standard subexams of around 6 or 7 indicated stereotyped behavior at a normal level. The grades less than 5 in the Social Behavior (SB) index of teachers’ form were considered to have low social interaction. After completing the autism assessment questionnaire by their teachers, the children with autism who had low scores in SB (less than 5) and high levels of stereotyped behaviors (around 6 or 7) were selected. The final 30 children with autism were randomly assigned to experimental and control group, 15 children in each group. Based on the criteria to determine the number of sample size according to valid statistic sources (Delavar, 2016), the sample size in experimental studies for each group was proven to be at least 15 children.

The experimental group underwent totally 15 sessions of training MT along with PT for a period of 7 weeks: two sessions every week except the last session in which three sessions were run. This study was conducted in one of the children’s classrooms. Exclusion criteria were missed sessions (three) during the intervention process and additional disabilities. The instruments used in the present study were Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), Teacher Assessment of Social Behavior Questionnaire, and Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS).

AQ scale is also called as “Cambridge University Behavior and Personality Questionnaire for Children (AQ-Child)” and was developed by Auyeung et al. (2008) at Autism Research Center in Cambridge. It consists of 50 statements. There are four options for each statement which should be completed by children’s parent or guardian. The total score is calculated based on the points in front of each statement in the answer sheet. The score ranges from 0 to 150. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated and for the measure as a whole; the alpha coefficient was high (a=0.97). The internal validity of the five AQ-Child subscales were also satisfactory (social skills=0.93; attention to detail=0.83; attention switching=0.89; communication=0.92; and imagination=0.88) (Auyeung et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency of all the items with each other and with the total score in Iranian society was proved to be 76% and 79%, respectively (Nejatisafa, Kazemi, & Alaghbandrad, 2003).

The Teacher Assessment of Social Behavior questionnaire was developed by Asher and Cassidy in 1992. It measures four areas: pro-social (items 1, 5, 9), aggressive (items 2, 6, 10), shyness/withdrawn (items 3, 7, 1), and disruptive behaviors (items 4, 8, 12) (Cassidy & Asher, 1992). The results are estimated by Cronbach’s alpha (aggressive, 0.79; disruptive behaviors, 0.77; pro-social, 0.76; and shyness/withdrawn, 0.59). Following values for Pearson correlation coefficient were obtained: aggressive, 0.42; disruptive behaviors, 0.35; pro-social, 0.15; and shyness/withdrawal, 0.80 was also estimated (Pavlidou, Arvanitidou, & Chatzigeorgiadou, 2011).

The following pre-test values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire were obtained: pro-social, 71%; aggressive, 76%; shyness/withdrawn, 73%; and disruptive behaviors, 79% components. The following post-test alpha coefficient values were found: pro-social, 75%; aggressive, 77%; shyness/withdrawn, 76%; and disruptive behaviors, 0.80 was also estimated. Ostavi et al. (2015) in Iranian sample indicated alpha coefficient of 0.78 for subscale social cooperation, 0.76 for aggression, 0.80 for shyness/withdrawn, and 0.81 for disruptive behaviors. In their study, the internal validity of this test was found to be 0.97.

GARS was developed as a valid test by Gilliam in 1994. It includes four subscales: stereotyped behaviors, communication, social interaction, and developmental disorders. Each subscale consists of 14 items. Previous studies indicated alpha coefficient of 90% for stereotyped behaviors, 89% for communication, 93% for social interaction, 88% for developmental disorders, and 96% for autism typology. The internal validity of this test was found to be 99% and 100%, respectively .(Gilliam, 1995). Ahmadi et al. (2011) in Iranian sample indicated alpha coefficient of 0.90 for stereotyped behaviors, 0.89 for communication, 0.93 for social interactions, 0.88 for developmental issues. This study indicated alpha coefficient of 74% for stereotyped behaviors, 92% for communication, 73% for social interactions, and 80% for developmental issues.

The purpose of MT in this study is improvising, playing different instruments with desired rhythm and intensity, playing instruments rhythmically, as well as singing childish songs that require children to cooperate with a group or in a pair and teach them the discipline and how to take turns while playing and reading. First, in order to develop desire, MT techniques were used. The therapist accompanied sounds, words, and syllables with the children’s favorite, appealing music. After the children began to consider and develop communicative responses along with accompanying music, some play toys were gradually used. In sum, all the sessions in the treatment process started with music and proceeded and ended with music along with play.

Playing, singing, and listening to childish music that follows one of the methods of MT called Orff-Schulwerk, which improves interpersonal cooperations. In this study, MT activities include passive (e.g. listening) and active (e.g. playing, singing, and rhythmic motions) forms. PT is implemented using techniques of PT which inform children of all types of communication. For the children with autism, games that improve the process of adaptation to the community and society such as throwing the ball into the air, standing in a circle and passing the ball to each other, walking around the chair and sitting when the music stops, picking up the ball and stopping once the music stops, duplicating models of bricks for hand–eye coordination and strengthening the muscles of hand, and playing exhibition games based on the improvization of theatrical scenes in a given subject.

The training program has been selected from among accredited domestic and foreign MT along with PT. Intervention process for all the subjects took 15 sessions of MT along with PT. Each session was conducted for a period of 60 minutes for 7 weeks. In all sessions, a tape recorder for playing the music, two kinds of musical instruments (belz and flute recorder), a ball, and a number of therapeutic toys for children with autism were used. The number of present kids in each session was 15. In order to guide the sessions, two instructors performed the activities of controlling the children, and an instructor/the researcher along with one expert colleague provided intervention to the children. The instructors were graduates of psychology and underwent MT and PT instruction courses as part of their educational courses. It should be mentioned that all educational sessions were held in a group in one class.

The structure of sessions of training MT along with PT is as follows:

First session was undertaken by using pictures for communication, eye contact, and simple friendly concepts such as collaboration, singing familiar songs with music for children with autism, and singing songs and discussing music. The second session was undertaken by making sounds, and syllables through the active participation of children, implementing actively engaging games, various programs of group and solo recitals, and music therapist accompaniment by playing songs for the participants. The third session was undertaken by implementing games which are based on physical activity, active games, and rhythmic games.

The fourth session was undertaken by role-playing; inclusion of poetry in the form of needed medical, social, and psychological concepts; implementing actively engaging games; singing to enhance the sense of cooperation in children with autism. The fifth session was undertaken by presenting goal-oriented and well-planned games which include elements of movement, thought, and competition. The sixth session was undertaken by collective and cooperative games, performing theater, and rhythmic movements. Children with autism adjust their movements with the rhythm they hear or a favorite rhythm of theirs based on specific feeling. Meanwhile, MT tries to coordinate patient’s weakest innovative movements with the rhythm in different sessions, develop them, and extend his feelings. These movements are interrupted with rhythmic body movements.

The seventh session was undertaken by reviewing the previous sessions as much as possible, improvising, or composing music. The eighth session was undertaken by performing skill-related physical games, listening to music, dancing with music. The ninth session: role-playing, music, and relaxation. The music therapist performs a few pieces while children with autism are listening to him in a calm state of mind and body in order to improve intellectual imagination for self-awareness. These imaginations awaken the emotional and psychological aspects of the children, and they cause the child to understand and express them with the help of the music therapist.

The 10th session was undertaken by implementing fun and energetic games in order to make behaviors efficient and increase attention. The 11th session was undertaken by developing children’s skill in playing different roles and increasing their attention and concentration by playing their favorite music in order to decrease challenging behaviors. The 12th session was undertaken by singing childish songs with music and simultaneous rhythmic movements. The 13th session was undertaken by reviewing previous sessions as much as possible. Children’s favorite music is played while they were performing the intended actions. After practicing for a while, the child himself can do the intended action without being told to do that once the music is played. The 14th session was undertaken by using the tempo skillfully to develop listening skills and to increase the precision and communication. The 15th session was undertaken by concluding the sessions and collecting participants’ feedback, discussion, listening, and singing.

After obtaining the permission from the Ministry of Education and ensuring for ASD using Auyeung et al., (2008) questionnaire of autism assessment in two special schools for males, the parents were asked to provide their consent. Then, exclusion criteria were applied to ensure that all participants in the research satisfied the intended criteria (three children with autism were excluded because of their additional disabilities). Next, children were randomly assigned to either experimental or control group; finally, 15 children were included in each group.

One session at the beginning was dedicated to introducing the procedure and another at the end for concluding and gathering feedback from participants and playing music that the children desired and playing a favorite game. Then, the post-test estimations were performed to both groups. To analyze the collected data, descriptive statistical methods such as mean and standard deviation (SD) and inferential statistical methods such as analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were used.

3. Results

Mean and SD of pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental and control group are presented in Table 1. It also shows the results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (K-S Z) to ensure normality of the distribution of variables between the two groups. According to Table 2, Z statistics of Kolmogorov–Smirnov is not significant for any variable. Therefore, it can be concluded that the distribution of these variables is normal.

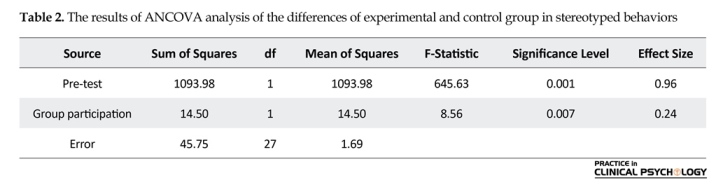

One-way analysis of covariance was used to examine the effect of training using MT along with PT on stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. The results of homogeneity of regression of pre-test–post-test for stereotyped behaviors in experimental and control group showed that the regression was equal (F1,26=0.21, P>0.05). The results of Levine’s test regarding the dependent variable in both groups showed that the variances of stereotyped behaviors are equal (F1,28=3.14, P>0.05). F-statistic of the linear relationship between pre-test of stereotyped behaviors with post-test of the same variable (414.69) was calculated to be significant at the level of 0.001. F-statistic of the deviation of linear relationship between pre-test and post-test of the variable of stereotyped behaviors was calculated to be insignificant (0.72). Considering these findings, it can be said that there is a

Autism is a complex neurobehavioral condition, which could be mild to severe, and generally has many associated symptoms. These symptoms are categorized into three classes: A. Abnormal social interaction; B. Abnormal verbal and nonverbal communication; and C. Stereotyped and rigid patterns of behavior and interests (Staal, 2015).

Excessive concern over various parts of the body (Rodrigues, Goncalves, Costa, & Soares, 2013), damaging qualitative experience in communication and social interaction (America Psychiatric Association, 2013; Gilley & Ringdahl, 2014), and poor academic achievement and job performance are other features of children with autism (Nader Grosbois & Day, 2011).

Difficulties and delay in social interaction are often the earliest features in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but they can be subtle and easily missed. In contrast to those with specific language disorders, children with ASD often fail to use gestures or mime to compensate. An individual with ASD often struggles to engage in social chat and build on conversation about someone else’s hobby or interest (Yates, & Le Couteur, 2016). Due to the nature of these impairments, students with autism exhibit significant challenges that require intensive support from both school and home. ASD can cause unique series of stressors including social isolation and stigma, difficulties in obtaining treatment, comorbid medical conditions, problems in sustaining employment, financial burden, and an unclear prognosis for family (Hillman, 2007).

Worldwide the prevalence of ASD is increasing. In some recent studies, the rate of ASD exceeds 1% the latest report made by the US CDC; ASD has been diagnosed in approximately 1 out of 88 children (Huang et al., 2014). In 2012, the prevalence of ASD in Iran was estimated at around 6.6 in 10,000 children (Samadi, Mahmoodizadeh, & McConkey, 2011). Children with autism experience fear of performing activities with friends, which is another limitation that these children need to correct (Sanrattana, Maneerat, & Srevisate, 2014). It does not necessarily mean that children with autism do not have a friendly interaction with others. In fact, most of them have a strong attachment to family members and friends; however, they are unable to establish a bilateral relationship with their peers and parents (Yacos, 2014).

In other words, social skills including complex cognitive and behavioral interactions such as identifying and interpreting social accuracy and considering the context and assessment of others’ behavior by paying attention to the responses of others are associated with many limitations in these children (O’Reilly et al., 2014). This reduction in establishing social communication of children with autism stems from the disorder of the theory of mind or understanding mental states of our social situations and others’ mental life (Hoogenhout & Malcolm-Smith, 2014).

Children with autism show less flexibility than their growing peers in response to “Penny-Hiding Games” (Murray & Healy, 2015) and pay less attention to and behave more stereotypically than the children of same age while playing games (America Psychological Association, 2013; Lang, Regester, Rispoli, Pimentel, & Camargo, 2010). The type, frequency, and intensity of stereotyped behaviors of children with ASD are widely different, but mostly they remain over the course of the time and will be the strongest predictor of early diagnosis of ASD, and if these behaviors are prevented, anxiety, protest, aggression, and self injury will occur (King et al., 2009).

To help children with autism, on-time and appropriate therapy are strongly recommended after the diagnosis of ASD. Art therapy develops a flexible attitude in children with autism and solves problems in the two areas of social–communicational and restricted–stereotyped behaviors (Schweizer, Knorth, & Spreen, 2014). Research has shown that MT facilitates the skill in areas that affect ASD and increases social interaction and communication skills (Geretsegger, Holck, & Gold, 2012) and facilitating speech development such as the ability to establish and maintain relationships in short periods of time (Groß, Linden, & Ostermann, 2010).

In addition, music has a positive therapeutic effect on communication development, personal and interpersonal responsibility, and playing skills (Schwartzberg & Silverman, 2013; Simpson & Keen, 2011; Whipple, 2012). Since stereotyped behaviors appear in the absence of social consequences, using auditory–vocal stimuli especially music is effective as an automatic reinforcement for these children (Saylor, Sidener, Reeve, Fetherston, & Progar, 2012). The use of music and music-based games improve, delay, and restrict non-musical background of children with autism (Reschke-Hernandez, 2011). Lanovaz, Sladeczek, and Rapp (2011), Lanovaz, Rap, and Ferguson (2012), and Saylor, et al. (2012) examined the impact of music on vocal stereotyped behaviors of children with autism and found that non-random access to auditory stimulation (e.g. music and audio produced using toys) immediately decreases vocal stereotyped behaviors in these children.

In addition, James et al. (2015) and Simpson, Keen, and Lamb (2013) in their research on the effect of MT on people with autism found that MT effectively decreased undesirable behaviors, promoted social interactions, and increased communication. In addition to the aforementioned strategy, compared to using only one method of treatment, the application of a mixture of music and play that includes playing, movement, and singing with music along with using a playing equipment increases eye contact and social interaction and decreases isolation, gaze aversion, and avoidance behaviors in children with ASD (Whipple, 2012). Furthermore, playing games with children with autism decreases their stereotyped behaviors and other behavioral problems (Koegel, Firestone, Kramme, & Dunlap, 1974; Lang et al., 2014).

Because flexible, social, and imaginative qualities are underdeveloped in children with autism, PT can change their playing methods and provide an opportunity to interact with others (Lu, Petersen, Lacroix, & Rousseau, 2010). Playing, by providing response interruption and redirection, causes displacement and reduction of stereotyped behaviors (Martinez & Betz, 2013). Koegel, Singh, and Koegel (2010) found that there is an inverse relationship between self-stimulation and appropriate game. In fact, using children’s favorite objects is one of the methods to deal with self-stimulation. Lang et al., (2014) and Lu et al. (2010) found that playing with toys during behavioral intervention decreased stereotyped behaviors and that children with autism acted better and happier after behavioral interventions. Furthermore, PT leads to an increase in verbal expression, engagement, and sustained social interaction.

Considering the potentiality of MT and PT in sensory excitement and inciting child’s senses and the role of these two approaches in improving communication, lack of sufficient knowledge in this area, and the fact that previous studies focused individually on these two approaches, in this study, we investigated the effects of MT and PT simultaneously. Therefore, keeping in mind treatment priorities in children with autism, in this study, we focused on to increase SBs and decrease stereotyped behaviors by applying MT and PT. Today, PT and MT are optional methods of therapy and have priority over other therapeutic approaches. Previous studies have recommended that integrating these two approaches can effectively increase SB and decease stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to find out whether training children with autism by using PT with MT leads to increase in appropriate SBs and decrease inappropriate stereotyped behaviors.

2. Methods

In this experimental study, a pre-test–post-test control group design was used. The statistical population of this study consisted of children with autism between the ages of 6 to 12 years living in Rasht, Iran during the 2014–15 educational year.

A total of 30 children qualified for the study were selected using convenient sampling procedure and were assigned to control and experimental groups randomly. The participants of this study were selected based on some criteria. Participants in both groups had no experience in participating in MT along with PT interventions. To ensure that participants had IQ between 50 and 70, IQ test was administered. Before conducting the research, diagnosis of autism was conducted according to the diagnostic criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) (5th edition).

Considering the standardization that was conducted in the Gilliam’s diagnostic exam of autism guide (Ahmadi, Safari, Hemmatiyan, & Kalili, 2011), the grades of standard subexams of around 6 or 7 indicated stereotyped behavior at a normal level. The grades less than 5 in the Social Behavior (SB) index of teachers’ form were considered to have low social interaction. After completing the autism assessment questionnaire by their teachers, the children with autism who had low scores in SB (less than 5) and high levels of stereotyped behaviors (around 6 or 7) were selected. The final 30 children with autism were randomly assigned to experimental and control group, 15 children in each group. Based on the criteria to determine the number of sample size according to valid statistic sources (Delavar, 2016), the sample size in experimental studies for each group was proven to be at least 15 children.

The experimental group underwent totally 15 sessions of training MT along with PT for a period of 7 weeks: two sessions every week except the last session in which three sessions were run. This study was conducted in one of the children’s classrooms. Exclusion criteria were missed sessions (three) during the intervention process and additional disabilities. The instruments used in the present study were Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), Teacher Assessment of Social Behavior Questionnaire, and Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS).

AQ scale is also called as “Cambridge University Behavior and Personality Questionnaire for Children (AQ-Child)” and was developed by Auyeung et al. (2008) at Autism Research Center in Cambridge. It consists of 50 statements. There are four options for each statement which should be completed by children’s parent or guardian. The total score is calculated based on the points in front of each statement in the answer sheet. The score ranges from 0 to 150. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated and for the measure as a whole; the alpha coefficient was high (a=0.97). The internal validity of the five AQ-Child subscales were also satisfactory (social skills=0.93; attention to detail=0.83; attention switching=0.89; communication=0.92; and imagination=0.88) (Auyeung et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency of all the items with each other and with the total score in Iranian society was proved to be 76% and 79%, respectively (Nejatisafa, Kazemi, & Alaghbandrad, 2003).

The Teacher Assessment of Social Behavior questionnaire was developed by Asher and Cassidy in 1992. It measures four areas: pro-social (items 1, 5, 9), aggressive (items 2, 6, 10), shyness/withdrawn (items 3, 7, 1), and disruptive behaviors (items 4, 8, 12) (Cassidy & Asher, 1992). The results are estimated by Cronbach’s alpha (aggressive, 0.79; disruptive behaviors, 0.77; pro-social, 0.76; and shyness/withdrawn, 0.59). Following values for Pearson correlation coefficient were obtained: aggressive, 0.42; disruptive behaviors, 0.35; pro-social, 0.15; and shyness/withdrawal, 0.80 was also estimated (Pavlidou, Arvanitidou, & Chatzigeorgiadou, 2011).

The following pre-test values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire were obtained: pro-social, 71%; aggressive, 76%; shyness/withdrawn, 73%; and disruptive behaviors, 79% components. The following post-test alpha coefficient values were found: pro-social, 75%; aggressive, 77%; shyness/withdrawn, 76%; and disruptive behaviors, 0.80 was also estimated. Ostavi et al. (2015) in Iranian sample indicated alpha coefficient of 0.78 for subscale social cooperation, 0.76 for aggression, 0.80 for shyness/withdrawn, and 0.81 for disruptive behaviors. In their study, the internal validity of this test was found to be 0.97.

GARS was developed as a valid test by Gilliam in 1994. It includes four subscales: stereotyped behaviors, communication, social interaction, and developmental disorders. Each subscale consists of 14 items. Previous studies indicated alpha coefficient of 90% for stereotyped behaviors, 89% for communication, 93% for social interaction, 88% for developmental disorders, and 96% for autism typology. The internal validity of this test was found to be 99% and 100%, respectively .(Gilliam, 1995). Ahmadi et al. (2011) in Iranian sample indicated alpha coefficient of 0.90 for stereotyped behaviors, 0.89 for communication, 0.93 for social interactions, 0.88 for developmental issues. This study indicated alpha coefficient of 74% for stereotyped behaviors, 92% for communication, 73% for social interactions, and 80% for developmental issues.

The purpose of MT in this study is improvising, playing different instruments with desired rhythm and intensity, playing instruments rhythmically, as well as singing childish songs that require children to cooperate with a group or in a pair and teach them the discipline and how to take turns while playing and reading. First, in order to develop desire, MT techniques were used. The therapist accompanied sounds, words, and syllables with the children’s favorite, appealing music. After the children began to consider and develop communicative responses along with accompanying music, some play toys were gradually used. In sum, all the sessions in the treatment process started with music and proceeded and ended with music along with play.

Playing, singing, and listening to childish music that follows one of the methods of MT called Orff-Schulwerk, which improves interpersonal cooperations. In this study, MT activities include passive (e.g. listening) and active (e.g. playing, singing, and rhythmic motions) forms. PT is implemented using techniques of PT which inform children of all types of communication. For the children with autism, games that improve the process of adaptation to the community and society such as throwing the ball into the air, standing in a circle and passing the ball to each other, walking around the chair and sitting when the music stops, picking up the ball and stopping once the music stops, duplicating models of bricks for hand–eye coordination and strengthening the muscles of hand, and playing exhibition games based on the improvization of theatrical scenes in a given subject.

The training program has been selected from among accredited domestic and foreign MT along with PT. Intervention process for all the subjects took 15 sessions of MT along with PT. Each session was conducted for a period of 60 minutes for 7 weeks. In all sessions, a tape recorder for playing the music, two kinds of musical instruments (belz and flute recorder), a ball, and a number of therapeutic toys for children with autism were used. The number of present kids in each session was 15. In order to guide the sessions, two instructors performed the activities of controlling the children, and an instructor/the researcher along with one expert colleague provided intervention to the children. The instructors were graduates of psychology and underwent MT and PT instruction courses as part of their educational courses. It should be mentioned that all educational sessions were held in a group in one class.

The structure of sessions of training MT along with PT is as follows:

First session was undertaken by using pictures for communication, eye contact, and simple friendly concepts such as collaboration, singing familiar songs with music for children with autism, and singing songs and discussing music. The second session was undertaken by making sounds, and syllables through the active participation of children, implementing actively engaging games, various programs of group and solo recitals, and music therapist accompaniment by playing songs for the participants. The third session was undertaken by implementing games which are based on physical activity, active games, and rhythmic games.

The fourth session was undertaken by role-playing; inclusion of poetry in the form of needed medical, social, and psychological concepts; implementing actively engaging games; singing to enhance the sense of cooperation in children with autism. The fifth session was undertaken by presenting goal-oriented and well-planned games which include elements of movement, thought, and competition. The sixth session was undertaken by collective and cooperative games, performing theater, and rhythmic movements. Children with autism adjust their movements with the rhythm they hear or a favorite rhythm of theirs based on specific feeling. Meanwhile, MT tries to coordinate patient’s weakest innovative movements with the rhythm in different sessions, develop them, and extend his feelings. These movements are interrupted with rhythmic body movements.

The seventh session was undertaken by reviewing the previous sessions as much as possible, improvising, or composing music. The eighth session was undertaken by performing skill-related physical games, listening to music, dancing with music. The ninth session: role-playing, music, and relaxation. The music therapist performs a few pieces while children with autism are listening to him in a calm state of mind and body in order to improve intellectual imagination for self-awareness. These imaginations awaken the emotional and psychological aspects of the children, and they cause the child to understand and express them with the help of the music therapist.

The 10th session was undertaken by implementing fun and energetic games in order to make behaviors efficient and increase attention. The 11th session was undertaken by developing children’s skill in playing different roles and increasing their attention and concentration by playing their favorite music in order to decrease challenging behaviors. The 12th session was undertaken by singing childish songs with music and simultaneous rhythmic movements. The 13th session was undertaken by reviewing previous sessions as much as possible. Children’s favorite music is played while they were performing the intended actions. After practicing for a while, the child himself can do the intended action without being told to do that once the music is played. The 14th session was undertaken by using the tempo skillfully to develop listening skills and to increase the precision and communication. The 15th session was undertaken by concluding the sessions and collecting participants’ feedback, discussion, listening, and singing.

After obtaining the permission from the Ministry of Education and ensuring for ASD using Auyeung et al., (2008) questionnaire of autism assessment in two special schools for males, the parents were asked to provide their consent. Then, exclusion criteria were applied to ensure that all participants in the research satisfied the intended criteria (three children with autism were excluded because of their additional disabilities). Next, children were randomly assigned to either experimental or control group; finally, 15 children were included in each group.

One session at the beginning was dedicated to introducing the procedure and another at the end for concluding and gathering feedback from participants and playing music that the children desired and playing a favorite game. Then, the post-test estimations were performed to both groups. To analyze the collected data, descriptive statistical methods such as mean and standard deviation (SD) and inferential statistical methods such as analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were used.

3. Results

Mean and SD of pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental and control group are presented in Table 1. It also shows the results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (K-S Z) to ensure normality of the distribution of variables between the two groups. According to Table 2, Z statistics of Kolmogorov–Smirnov is not significant for any variable. Therefore, it can be concluded that the distribution of these variables is normal.

One-way analysis of covariance was used to examine the effect of training using MT along with PT on stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. The results of homogeneity of regression of pre-test–post-test for stereotyped behaviors in experimental and control group showed that the regression was equal (F1,26=0.21, P>0.05). The results of Levine’s test regarding the dependent variable in both groups showed that the variances of stereotyped behaviors are equal (F1,28=3.14, P>0.05). F-statistic of the linear relationship between pre-test of stereotyped behaviors with post-test of the same variable (414.69) was calculated to be significant at the level of 0.001. F-statistic of the deviation of linear relationship between pre-test and post-test of the variable of stereotyped behaviors was calculated to be insignificant (0.72). Considering these findings, it can be said that there is a

linear relationship between the pre-test and post-test of the variable of stereotyped behaviors.

F-statistic of stereotyped behaviors in the post-test was found to be 8.56 (P=0.01); this shows that the difference between the two groups in stereotyped behaviors is significant. The effect size (0.24) shows that this difference is significant. Results of covariance analysis showed that the corrected mean of the experimental group in stereotyped behaviors (23.53) is less than that of the control group (24.93). The mean difference between these two groups was found to be −1.39, which is significant according to F-statistics (P=0.01). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that training using MT along with PT is effective in decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism.

Multivariate analysis of covariance was used to examine the effect of training using MT along with PT on the components of SB (i.e. pro-social, aggressive, shy/withdrawn, and disruptive behaviors). The results of homogeneity test for regression of pre-test–post-test of experimental and control groups considering the components of SB showed that the regressions of both groups are equal (F4,17=0.84, P>0.05). The results of Levene’s test for examining the homogeneity of variance of dependent variables showed that the variance in components of pro-social (F1,28=0.56, P>0.05), aggressive (F1,28=0.28, P>0.05), shyness/withdrawn (F1,28=3.10, P>0.05), and disruptive behaviors (F1,28=0.97, P>0.05) is equal in both groups. The results of Box’s test for examining the equality of covariance matrices of dependent variables between the experimental and control group showed that the covariance matrices of the dependent variables between the two groups are equal (Box M=16.07, F=1.35, P>0.05).

F-statistic of stereotyped behaviors in the post-test was found to be 8.56 (P=0.01); this shows that the difference between the two groups in stereotyped behaviors is significant. The effect size (0.24) shows that this difference is significant. Results of covariance analysis showed that the corrected mean of the experimental group in stereotyped behaviors (23.53) is less than that of the control group (24.93). The mean difference between these two groups was found to be −1.39, which is significant according to F-statistics (P=0.01). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that training using MT along with PT is effective in decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism.

Multivariate analysis of covariance was used to examine the effect of training using MT along with PT on the components of SB (i.e. pro-social, aggressive, shy/withdrawn, and disruptive behaviors). The results of homogeneity test for regression of pre-test–post-test of experimental and control groups considering the components of SB showed that the regressions of both groups are equal (F4,17=0.84, P>0.05). The results of Levene’s test for examining the homogeneity of variance of dependent variables showed that the variance in components of pro-social (F1,28=0.56, P>0.05), aggressive (F1,28=0.28, P>0.05), shyness/withdrawn (F1,28=3.10, P>0.05), and disruptive behaviors (F1,28=0.97, P>0.05) is equal in both groups. The results of Box’s test for examining the equality of covariance matrices of dependent variables between the experimental and control group showed that the covariance matrices of the dependent variables between the two groups are equal (Box M=16.07, F=1.35, P>0.05).

The results of Bartlett’s chi-square test for examining the significant relationship between the components of SB showed that the relationship between these components is significant (X2=146.31, df=9, P<0.001). After examining multivariate analysis of variance assumptions, test results showed that there is a significant difference between the two groups in the components of SB (Wilk’s Lambda=0.22, F4,21=18.56, P<0.001). The results of multivariate analysis of covariance for examining the difference in experimental and control groups in components of SB in the pre-test-post-test are reported in Table 3. Univariate Analysis of Variance is reported in Table 4 in order to examine which components of SB differ in experimental and control group.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of training using MT along with PT on increasing SB and decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. The results of covariance analysis showed that SB of children who were trained using PT along with MT was significantly more than children who did not receive such treatment. Reports indicated that the MT by taking advantage of musical experiences and their relationships develops

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of training using MT along with PT on increasing SB and decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. The results of covariance analysis showed that SB of children who were trained using PT along with MT was significantly more than children who did not receive such treatment. Reports indicated that the MT by taking advantage of musical experiences and their relationships develops

and improves communication and social interaction, initiating behavior, socio-emotional reciprocity, non-verbal communication skills, and adaptation skills in children with autism (Geretsegger et al., 2014).

This finding is consistent with research conducted by Simpson and Keen (2011), James et al. (2015), Geretsegger et al. (2014), Gooding (2011), Mateos Moreno and Atencia Dona (2013), and Schwartzberg and Silverman (2013). They showed that activities related to MT facilitate social communication and dynamic, common, and active interaction in children with autism. Our results with training using PT was found to be consistent with the research conducted by Solomon et al. (2014); Gutman et al. (2012); and Rodrigues, Sei, and Arruda (2013). They showed that playing intervention programs increases interaction and language development in children with autism.

In explaining present results, it can be said that MT increases the precision of auditory information processing in children with autism. Music is one of the reasons for the effect of music on these children’s skills (Pasiali, LaGasse, & Penn, 2014). People with autism are not cable enough to respond appropriately to stimuli; therefore, most researchers believe that their feelings should be strengthened through music. Positive and effective reactions of these patients encouraged them to participate in goal-oriented perceptual-motor and language-related and social activities (Nelson, Anderson, & Gonzales, 1984). Studies indicated that principles of pattern perception and production of functional speech organize perception of important language information embedded in musical stimuli (Lim, 2010).

In addition, it can be said that PT has positive effects on SB in children with autism, integration of PT with MT can be an effective method to improve these children’s behaviors. Since a significant reduction was found in SB of children with autism, PT can encourage their participation in a series of motor behaviors, and it, in turn, can promote SB of these children. Therefore, playing activities help these children practice, understand, and utilize social environment (Rogers, Cook, & Merry, 2005; Szabo, 2014).

It can be concluded that training using MT along with PT has a positive effect on increasing SB and decreasing shyness/withdrawal in children with autism. Diverse rhythms and non-verbal rhythmic connection of music help children with autism communicate with therapist and peers well. When the music is accompanied by meaningful and conceptual games, children with autism are able to understand and interpret the symbols and the voices of others and share their interests with others. Then gradually children develop their relationship with the environment and non-musical places.

As mentioned earlier, one part of the hypothesis under investigation in this study was rejected, the part which is related to the effect of training using MT along with PT on decreasing aggression and disruptive behaviors. This finding is inconsistent with the results of research studies conducted by James et al. (2015) and Choi, Lee, and Lee (2010). Lack of effectiveness of the two subskills, aggression and disruptive behaviors, can also be interpreted by the difficult nature of these subskills. However, since interpersonal differences of the individuals with autism are very high, the findings are not generalizable to the whole population.

While one child may respond positively to certain techniques, another child may react negatively. Since children with autism suffer from various sensory disorders, the sound creates different responses in these children depending on the volume, resonance, intensity, and duration. Therefore, observing children’s responses to sound and music is often difficult, and it is also more difficult to interpret their reactions. As aggression and disruptive behaviors depend on various environments both at home and at school, effective implementation of this training also needs parents and mentors help explore the underlying causes of aggression and disruptive behaviors of the children.

The findings of this study also indicated that stereotyped behaviors of children who underwent training using PT along with MT were significantly less than children who did not receive such training. The finding is consistent with research conducted by Lanovaz et al. (2009), Lanovaz et al., (2012), Saylor et al. (2012), and Rapp (2007). They found that MT decreases stereotyped behaviors in children with autism and presenting non-random access to musical stimuli normally decreases reinforced behavior more than other conventional stimuli. Thus, with this method, stereotyped behavior is shorter and decreases with sensory extinction (Saylor et al., 2012). This result is consistent with the research conducted by Lang et al. (2010), Petrus et al. (2008), and Lang et al. (2009) They examined the effectiveness of game intervention in children with autism, and the results showed positive effects in decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism.

Therefore, it can be said that distraction, focus, support, and expression are four functions of music which promote emotional regulation. These patterns may help regulate the emotions of children by using the four music functions during stressful moments and thus decrease the stereotyped behaviors (Prizant, 2006; Walworth, 2010). In addition, it is commonly believed that playing skill acquisition in early childhood can lead to maintaining automatic reinforcement and reduction in stereotyped behaviors (Lang et al., 2014). In addition, improving the frequency, quality, or variety of games decreases stereotyped behaviors (Koegel et al., 1974; Lang et al., 2009; Lang et al., 2010).

Therefore, the results of this study showed that training using MT along with PT has a positive effect on decreasing stereotyped behaviors of children with autism. Using passive and active techniques helped researchers to recognize factors that cause anxiety in the children or move them into their own world. Passive techniques (e.g. listening to music) engage subconscious level, and children apparently do not resist them, but they are so pervasive that can change the stereotyped behaviors and remove barriers for children. Active techniques (e.g. playing game and music) cause a sense of power in children. In addition, providing a variety of favorite and exciting musical stimuli which were organized, accurate, and scientific prevented stereotyped behaviors in these children. Thus, training using PT with MT techniques can help these children overcome the stereotyped behaviors.

Due to executive and administrative limitations of the Children Rehabilitation Center of Rasht, implementing the follow-up study was impossible. Further research studies are suggested to be conducted by a larger sample and implementing the follow-up study. And since children with autism suffer from various sensory disorders and music evokes different responses in these children, it is recommended that further studies should separate hypersense and hyposense children based on the type of assessment before implementing the intervention. It is recommended that further studies examine other types of music such as improvising, playing more complicated instruments, and group playing along with PT and its possible effects on other functioning areas of children with autism in different age ranges.

Acknowledgements

This article was part of the second author's MA thesis in the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, which was financially supported by the Islamic Azad University of Rasht.

Conflict of Interest

All authors certify that this manuscript has neither been published in whole nor in part nor being considered for publication elsewhere. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Ahmadi, J., Safari, T., Hemmatiyan, M., & Kalili, Z. (2011). [Psychometric properties of the diagnostic test of autism (Persian)]. Isfahan: Jahad-e Daneshgahi.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington: American Psychiatric Pub.

Auyeung, B., Baron Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., & Allison, C. (2008). The autism spectrum quotient: Children’s version (AQ-Child). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1230-40. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0504-z

Cassidy, J., & Asher, S. R. (1992). Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Development, 63(2), 350-65. doi: 10.2307/1131484

Cervantes, P. E., Matson, J. L., Williams, L. W., & Jang, J. (2014). The effect of cognitive skills and autism spectrum disorder on stereotyped behaviors in infants and toddlers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(5), 502-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.01.008

Chevallier, C., Kohls, G., Troiani, V., Brodkin, E. S., & Schultz, R. T. (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 231-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007

Choi, A. N., Lee, M. S., & Lee, J. S. (2010). Group music intervention reduces aggression and improves self esteem in children with highly aggressive behavior: A pilot controlled trial. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 7(2), 213-17. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem182

Delavar, A. (2016). [Theoretical and practical research in the humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd Pub.

Geretsegger, M., Elefant, C., Mössler, K. A., & Gold, C. (2014). Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004381.pub3

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., & Gold, C. (2012). Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy's effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): Study protocol. BMC Pediatrics, 12(1), 2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-2

Gilley, C., & Ringdahl, J. E. (2014). The effects of item preference and token reinforcement on sharing behavior exhibited by children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(11), 1425–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.07.010

Gilliam, J. E. (1995). Gilliam autism rating scale: Examiner's manual. Austin, Texas: Proed.

Gooding, L. F. (2011). The effect of a music therapy social skills training program on improving social competence in children and adolescents with social skills deficits. Journal of Music Therapy, 48(4), 440-62. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.4.440

Groß, W., Linden, U., & Ostermann, T. (2010). Effects of music therapy in the treatment of children with delayed speech development results of a pilot study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 10(1), 39. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-39

Guillon, Q., Hadjikhani, N., Baduel, S., & Rogé, B. (2014). Visual social attention in autism spectrum disorder: Insights from eye tracking studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 42, 279-97. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.013

Gutman, S. A., Raphael Greenfield, E. I., Carlson, N., Friedman, R., & Iger, A. (2012). Enhancing social skills in adolescents with high functioning autism using motor based role play intervention. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1(1), 4. doi: 10.15453/2168-6408.1019

Hillman, J. (2007). Grandparents of children with autism: A review with recommendations for education, practice, and policy. Educational Gerontology, 33(6), 513–27. doi:10.1080/03601270701328425

Hoogenhout, M., & Malcolm Smith, S. (2014). Theory of mind in autism spectrum disorder: does DSM classification predict development. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(6), 597-607. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.02.005

Huang, J. P., Cui, S. S., Yu, H. A. N., Hertz-Picciotto, I. R. V. A., Qi, L. H., & Zhang, X. (2014). Prevalence and early signs of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) among 18–36 month old children in Tianjin of China. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 27(6), 453-461.

James, R., Sigafoos, J., Green, V. A., Lancioni, G. E., O’Reilly, M. F., Lang, R., et al. (2015). Music therapy for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(1), 39-54. doi: 10.1007/s40489-014-0035-4

King, B. H., Hollander, E., Sikich, L., McCracken, J. T., Scahill, L., Bregman, J. D., et al. (2009). Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: Citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(6), 583-90. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.30

Koegel, L. K., Singh, A. K., & Koegel, R. L. (2010). Improving motivation for academics in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(9), 1057-66. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0962-6

Koegel, R. L., Dyer, K., & Bell, L. K. (1987). The influence of child preferred activities on autistic children's social behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20(3), 243-52. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-243

Koegel, R. L., Firestone, P. B., Kramme, K. W., & Dunlap, G. (1974). Increasing spontaneous play by suppressing self stimulation in autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7(4), 521-8. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1974.7-521

Lang, R., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G., et al. (2014). Play skills taught via behavioral intervention generalize, maintain, and persist in the absence of socially mediated reinforcement in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(7), 860-72. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.04.007

Lang, R., O'Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. E., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., et al. (2009). Enhancing the effectiveness of a play intervention by abolishing the reinforcing value of stereotypy: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(4), 889-94. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-889

Lang, R., O'Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., Lancioni, G. E., et al. (2010). The effects of an abolishing operation intervention component on play skills, challenging behavior, and stereotypy. Behavior Modification, 34(4), 267-89. doi: 10.1177/0145445510370713

Lang, R., Regester, A., Rispoli, M., Pimentel, S., & Camargo, H. (2010). Rehabilitation issues in autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(3), 153–5. doi: 10.3109/17518421003607597

Lanovaz, M. J., Fletcher, S. E., & Rapp, J. T. (2009). Identifying stimuli that alter immediate and subsequent levels of vocal stereotypy: A further analysis of functionally matched stimulation. Behavior Modification, 33(5), 682-704. doi: 10.1177/0145445509344972

Lanovaz, M. J., Rapp, J. T., & Ferguson, S. (2012). The utility of assessing musical preference before implementation of noncontingent music to reduce vocal stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(4), 845-51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-845

Lanovaz, M. J., Sladeczek, I. E., & Rapp, J. T. (2011). Effects of music on vocal stereotypy in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(3), 647-51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-647

Lim, H. A. (2010). Effect of developmental speech and language training through music on speech production in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 47(1), 2–26. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.1.2

Lima, D., & Castro, T. (2012). Music spectrum: A music immersion virtual environment for children with autism. Procedia Computer Science, 14, 111-18. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2012.10.013

Lu, L., Petersen, F., Lacroix, L., & Rousseau, C. (2010). Stimulating creative play in children with autism through sandplay. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(1), 56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.09.003

Lundqvist, L. O., Andersson, G., & Viding, J. (2009). Effects of vibroacoustic music on challenging behaviors in individuals with autism and developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(2), 390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.08.005

Martinez, C. K., & Betz, A. M. (2013). Response interruption and redirection: Current research trends and clinical application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(2), 549–54. doi: 10.1002/jaba.38

Mateos Moreno, D., & Atencia Doña, L. (2013). Effect of a combined dance/movement and music therapy on young adults diagnosed with severe autism. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(5), 465–72. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.09.004

Matson, J. L., Kiely, S. L., & Bamburg, J. W. (1997). The effect of stereotypies on adaptive skills as assessed with the DASH-II and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 18(6), 471–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(97)00023-1

Moy, S. S., Riddick, N. V., Nikolova, V. D., Teng, B. L., Agster, K. L., Nonneman, R. J., et al. (2014). Repetitive behavior profile and supersensitivity to amphetamine in the C58/J mouse model of autism. Behavioural Brain Research, 259, 200–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.10.052

Muehlmann, A. M., Bliznyuk, N., Duerr, I., & Lewis, M. H. (2015). Repetitive motor behavior: Further characterization of development and temporal dynamics. Developmental Psychobiology, 57(2), 201–11. doi: 10.1002/dev.21279

Murray, C., & Healy, O. (2015). An examination of response variability in children with autism and the relationship to restricted repetitive behavior subtypes. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 11, 13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.11.012

Nader Grosbois, N., & Day, J. M. (2011). Emotional cognition: Theory of mind and face recognition. In J. L. Matson, & P. Sturmey (Eds.), International Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (pp. 127–57). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8065-6_9

Nejatisafa, A,. Kazemi, M., & Alaghbandrad , J. (2003). [Autistic traits in the adult population: Evidence for autism continuum hypothesis (Persian)]. Advances in Cognitive Science, 5, 34-9.

Nelson, D. L., Anderson, V. G., & Gonzales, A. D. (1984). Music activities as therapy for children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 21(3), 100–16. doi: 10.1093/jmt/21.3.100

O’Reilly, M. F., Sorrells, A., Gainey, S., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. E., Lang, R., et al. (2014). Naturalistic approaches to social skills training and development. In J. K. Luisell (Ed.), Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (pp. 90–100). New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199941575.003.0006

Ostavi, E., Hossein Khanzadeh, A., Khosrojavid, M., & Mousavi, V. A. (2015). [Effect of befriending skills training on increasing social behaviors in children with autism (Persian)]. Middle Eastern Journal of Disability Studies, 5 :298-306

Pasiali, V., La Gasse, A. B., & Penn, S. L. (2014). The effect of musical attention control training (MACT) on attention skills of adolescents with neurodevelopmental delays: A pilot study. Journal of Music Therapy, 51(4), 333–54. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thu030

Pavlidou, E., Arvanitidou, V., & Chatzigeorgiadou, S. (2012). The effectiveness of a pilot intervention program of physical education in multicultural preschool education. ΜΕΝΟΝ: Journal of Educational Research, 1, 53-66.

Petrus, C., Adamson, S. R., Block, L., Einarson, S. J., Sharifnejad, M., & Harris, S. R. (2008). Effects of exercise interventions on stereotypic behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiotherapy Canada, 60(2), 134–45. doi: 10.3138/physio.60.2.134

Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., Laurent, A. C., & Rydell, P. J. (2006). The SCERTS model: Volume I: Assessment; Volume II: Program planning and intervention. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes Publishing Company.

Rapp, J. T. (2007). Further evaluation of methods to identify matched stimulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(1), 73–88. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.142-05

Reschke Hernandez, A. E. (2011). History of music therapy treatment interventions for children with autism. Journal of Music Therapy, 48(2), 169–207. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.2.169

Rodrigues, F. P. H., Sei, M. B., & Arruda, S. L. S. (2013). [Play therapy with a child with Asperger Syndrome: A case study (French)]. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 23(54), 121–7. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272354201314

Rodrigues, J. L., Gonçalves, N., Costa, S., & Soares, F. (2013). Stereotyped movement recognition in children with ASD. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 202, 162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2013.04.019

Rogers, S, J., Cook, I., & Merry, A. (2005). Imitation and play with autism. In F. R. Volkmar., R. Paul., A. Klin, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 382–405). Hoboken: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9780470939345.ch14

Samadi, S. A., Mahmoodizadeh, A., & McConkey, R. (2011). A national study of the prevalence of autism among five-year-old children in Iran. Autism, 16(1), 5–14. doi:10.1177/1362361311407091

Sanrattana, U., Maneerat, T., & Srevisate, K. (2014). Social skills deficits of students with autism in inclusive schools. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 509–12. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.249

Saylor, S., Sidener, T. M., Reeve, S. A., Fetherston, A., & Progar, P. R., (2012). Effects of three types of noncontingent auditory stimulation on vocal stereotypy in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(1), 185–90. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-185

Schwartzberg, E. T., & Silverman, M. J. (2013). Effects of music based social stories on comprehension and generalization of social skills in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized effectiveness study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(3), 331–37. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.06.001

Schweizer, C., Knorth, E. J., & Spreen, M. (2014). Art therapy with children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A review of clinical case descriptions on “what works.” The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 577–93. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.009

See, C. M. (2012). The use of music and movement therapy to modify behaviour of children with autism. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 20(4), 1103–4.

Shuvarikov, A., Campbell, I. M., Dittwald, P., Neill, N. J., Bialer, M. G., Moore, C., et al. (2013). Recurrent HERVH mediated 3q13.2-q13.31 deletions cause a syndrome of hypotonia and motor, language, and cognitive delays. Human Mutation, 34(10), 1415–23. doi: 10.1002/humu.22384

Simpson, K., & Keen, D. (2011). Music interventions for children with autism: Narrative review of the literature. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(11), 1507-14. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1172-y

Simpson, K., Keen, D., & Lamb, J. (2013). The use of music to engage children with autism in a receptive labelling task. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(12), 1489-96. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.08.013

Solomon, R., Van Egeren, L. A., Mahoney, G., Huber, M. S. Q., & Zimmerman, P. (2014). Play project home consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(8), 475-85. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000096

Staal, W. G. (2015). Autism, DRD3 and repetitive and stereotyped behavior, an overview of the current knowledge. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(9), 1421-6. doi: 0.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.011

Szabó, M. K. (2014). Patterns of play activities in autism and typical development: A case study. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.483

Thompson, G. A., McFerran, K. S., & Gold, C. (2013). Family centred music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40(6), 840–52. doi: 10.1111/cch.12121

Tullis, C. A., Cannella Malone, H. I., & Payne, D. O. (2014). Literature review of Interventions for between task transitioning for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities including autism spectrum disorders. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(1), 91–102. doi: 10.1007/s40489-014-0039-0

Urbano, M., Okwara, L., Manser, P., Hartmann, K., Herndon, A., & Deutsch, S. I. (2014). A trial of D-cycloserine to treat stereotypies in older adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 37(3), 69–72. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0000000000000033

Walworth, D. D. (2010). Effect of live music therapy for patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Music Therapy, 47(4), 335-350. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.4.335

Wang, C., Shang, S., & Wei, X. (2010). Clinical observation electroacupuncture in combination with behavior therapy on child autism. Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science, 8, 230–2.

Whipple, J. (2012). Music therapy as an effective treatment with Autism Spectrum Disorders in early childhood: A metaanalysis. In P. Kern, & M. Humpale (Eds.), Early Childhood Music Therapy and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Developing Potential in Young Children and Their Families (pp. 59-76). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Wieder, S. (2012). Foreword. In L., Gallo Lopez, & L. C., Rubin (Eds.), Play based interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (pp. xi-xiv). London: Routledge.

Wiśniowiecka Kowalnik, B., Kastory Bronowska, M., Bartnik, M., Derwińska, K., Dymczak Domini, W., Szumbarska, D., et al. (2012). Application of custom designed oligonucleotide array CGH in 145 patients with autistic spectrum disorders. European Journal of Human Genetics, 21(6), 620–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.219

Xu, X. J., Zhang, H. F., Shou, X. J., Li, J., Jing, W. L., Zhou, Y., et al. (2015). Prenatal hyperandrogenic environment induced autistic like behavior in rat offspring. Physiology & Behavior, 138, 13-20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.09.014

Yakos, J. (2014). Social. In D. Granpeesheh, J. Tarbox, A. Najdowski, & J. Kornak (Eds.), Evidence Based Treatment for Children with Autism (pp. 287-315). United States: Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-411603-0.00016-1

Yates, K., & Le Couteur, A. (2016). Diagnosing autism/autism spectrum disorders. Paediatrics and Child Health, 26(12), 513–518. doi:10.1016/j.paed.2016.08.004

This finding is consistent with research conducted by Simpson and Keen (2011), James et al. (2015), Geretsegger et al. (2014), Gooding (2011), Mateos Moreno and Atencia Dona (2013), and Schwartzberg and Silverman (2013). They showed that activities related to MT facilitate social communication and dynamic, common, and active interaction in children with autism. Our results with training using PT was found to be consistent with the research conducted by Solomon et al. (2014); Gutman et al. (2012); and Rodrigues, Sei, and Arruda (2013). They showed that playing intervention programs increases interaction and language development in children with autism.

In explaining present results, it can be said that MT increases the precision of auditory information processing in children with autism. Music is one of the reasons for the effect of music on these children’s skills (Pasiali, LaGasse, & Penn, 2014). People with autism are not cable enough to respond appropriately to stimuli; therefore, most researchers believe that their feelings should be strengthened through music. Positive and effective reactions of these patients encouraged them to participate in goal-oriented perceptual-motor and language-related and social activities (Nelson, Anderson, & Gonzales, 1984). Studies indicated that principles of pattern perception and production of functional speech organize perception of important language information embedded in musical stimuli (Lim, 2010).

In addition, it can be said that PT has positive effects on SB in children with autism, integration of PT with MT can be an effective method to improve these children’s behaviors. Since a significant reduction was found in SB of children with autism, PT can encourage their participation in a series of motor behaviors, and it, in turn, can promote SB of these children. Therefore, playing activities help these children practice, understand, and utilize social environment (Rogers, Cook, & Merry, 2005; Szabo, 2014).

It can be concluded that training using MT along with PT has a positive effect on increasing SB and decreasing shyness/withdrawal in children with autism. Diverse rhythms and non-verbal rhythmic connection of music help children with autism communicate with therapist and peers well. When the music is accompanied by meaningful and conceptual games, children with autism are able to understand and interpret the symbols and the voices of others and share their interests with others. Then gradually children develop their relationship with the environment and non-musical places.

As mentioned earlier, one part of the hypothesis under investigation in this study was rejected, the part which is related to the effect of training using MT along with PT on decreasing aggression and disruptive behaviors. This finding is inconsistent with the results of research studies conducted by James et al. (2015) and Choi, Lee, and Lee (2010). Lack of effectiveness of the two subskills, aggression and disruptive behaviors, can also be interpreted by the difficult nature of these subskills. However, since interpersonal differences of the individuals with autism are very high, the findings are not generalizable to the whole population.