Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 93-102 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aghabaki S, Shahbazi M, Mohebi Nouredinvand M H, Alavi S Z. Effectiveness of CBT and SFBT on Cognitive Avoidance and Perceived Stress in Adolescent Girls From Divorced Families in Izeh, Iran. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :93-102

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1055-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1055-en.html

Soraya Aghabaki1

, Masoud Shahbazi *2

, Masoud Shahbazi *2

, Mohammad Hossein Mohebi Nouredinvand3

, Mohammad Hossein Mohebi Nouredinvand3

, Seyedeh Zahra Alavi1

, Seyedeh Zahra Alavi1

, Masoud Shahbazi *2

, Masoud Shahbazi *2

, Mohammad Hossein Mohebi Nouredinvand3

, Mohammad Hossein Mohebi Nouredinvand3

, Seyedeh Zahra Alavi1

, Seyedeh Zahra Alavi1

1- Department of Counseling, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, MaS.C., Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran. ,masoudshahbazi166@gmail.com

3- Department of Psychology, Mas.C., Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, MaS.C., Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Mas.C., Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), Cognitive avoidance, Stress, Adolescents, Divorce

Full-Text [PDF 680 kb]

(570 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (776 Views)

Full-Text: (190 Views)

Introduction

Divorce, as an increasingly prevalent global phenomenon, fundamentally alters the family’s core structure and significantly impacts its members. While adults navigate the complex dissolution of a marital bond, children, particularly adolescents, often disproportionately bear the psychological and social ramifications (Mentser & Sagiv, 2025). Adolescence itself is a pivotal developmental stage marked by profound physical, emotional, and cognitive transformations, rendering this demographic inherently susceptible to stressors that might be more readily managed by adults (Tullius et al., 2022). When the stability of the family unit, a primary crucible for psychological and social development, is disrupted by divorce, adolescents face an elevated risk for a myriad of maladjustment issues (Cao et al., 2022). Adolescent girls were selected as the focus of this study due to evidence indicating their heightened emotional vulnerability to parental divorce compared to boys. Research suggests that girls tend to internalize emotional distress more frequently, manifesting in higher rates of anxiety, depression, and cognitive avoidance, potentially due to gender-specific socialization patterns that emphasize emotional expressiveness and relational sensitivity (Rejaan et al., 2024; Amato & Keith, 1991). These internalizing behaviors necessitate targeted interventions tailored to their unique psychological needs, justifying the focus on this demographic to address their specific challenges effectively.

One prominent psychological consequence frequently observed in children of divorce is cognitive avoidance. This construct refers to a diverse suite of mental strategies employed to evade confronting undesirable thoughts, feelings, or memories (Godor et al., 2023). While ostensibly offering immediate relief from anxiety and distress, cognitive avoidance, in the long term, paradoxically perpetuates a vicious cycle of intensifying psychological problems (Eftekari & Bakhtiari, 2022). For adolescents grappling with the aftermath of divorce, cognitive avoidance plays a crucial, albeit often maladaptive, role in emotion regulation and psychological adaptation, frequently culminating in significant difficulties across social interactions and academic performance (Shipp et al., 2025). This avoidance can manifest in various forms, including thought suppression, distraction, or the reframing of negative cognitions to escape emotional discomfort. However, by consistently evading direct engagement with their emotional landscape, adolescents may hinder their capacity to process traumatic experiences, develop effective coping mechanisms, and ultimately attain psychological well-being (Songco et al., 2020). The persistent reliance on cognitive avoidance thus poses a considerable barrier to healthy development and adjustment within a post-divorce environment.

Beyond cognitive avoidance, perceived stress constitutes another significant and often pervasive outcome of divorce. Perceived stress is not merely the objective presence of stressors but rather an individual’s subjective appraisal of their ability to cope with demanding life situations and challenges (Naeimijoo et al., 2021). For children of divorce, particularly adolescent girls, heightened levels of perceived stress can manifest as a range of distressing symptoms, including anxiety, depressive symptomatology, and sleep disturbances (Karhina et al., 2023). When individuals perceive their available resources as insufficient to meet the demands of stressful situations, this perceived stress is amplified, creating a detrimental feedback loop that further compromises their emotional and physical health (Thorsén et al., 2022). The inherent instability, pervasive uncertainty, and numerous changes associated with family restructuring post-divorce can create a fertile ground for elevated perceived stress, thereby necessitating effective strategies to bolster adolescents’ resilience and coping capabilities (Lengua et al., 1999). Addressing perceived stress is, therefore, paramount for fostering emotional regulation and promoting overall psychological health in this vulnerable group.

In light of the significant psychological challenges confronting adolescents from divorced families, the exploration of effective therapeutic interventions becomes critically important. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) stands out as a highly efficacious and empirically supported therapeutic approach, widely recognized for its effectiveness across a broad spectrum of psychological disorders (Farimanian & Bayazi, 2024). At its core, CBT operates on the fundamental premise that dysfunctional thoughts and maladaptive behaviors contribute significantly to emotional distress. This approach actively engages individuals in identifying and challenging negative thought patterns, developing more adaptive cognitive schemas, and acquiring practical coping skills to manage challenging emotions and situations (Halder & Mahato, 2019). CBT was selected for this study because its structured approach directly targets cognitive avoidance by promoting cognitive restructuring, which helps adolescents confront and reframe maladaptive thoughts related to divorce, thereby reducing avoidance behaviors. Additionally, CBT’s focus on developing coping skills is hypothesized to mitigate perceived stress by equipping adolescents with tools to manage stressors more effectively, enhancing their emotional regulation and resilience (Stiede et al., 2023).

Another promising intervention, solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), offers a distinct yet equally valuable approach to addressing psychological distress. Unlike traditional problem-focused therapies, SFBT is a short-term, goal-oriented modality that emphasizes the identification and amplification of clients’ existing strengths, resources, and successful past experiences (Reddy et al., 2015). Rather than dwelling on the origins of problems, SFBT encourages individuals to envision a desired future state and to identify concrete, achievable steps towards realizing their goals (Chen et al., 2023). Through innovative techniques such as the “miracle question” and “scaling questions,” SFBT helps adolescents construct alternative, more positive narratives, enhance their sense of self-efficacy, and cultivate hope for the future (Karababa, 2023). SFBT was chosen for comparison due to its strengths-based approach, which is hypothesized to reduce cognitive avoidance by fostering a forward-looking perspective that encourages adolescents to focus on solutions rather than suppressing distressing thoughts. By amplifying self-efficacy and leveraging existing coping resources, SFBT is expected to lower perceived stress by empowering adolescents to feel more in control of their emotional responses and future outcomes, particularly in the context of divorce-related challenges (Żak & Pękala, 2024).

Given the documented adverse impacts of cognitive avoidance and perceived stress on the mental health of adolescent girls affected by parental divorce, there is a clear and urgent need for empirically validated therapeutic interventions. The comparison of CBT and SFBT is particularly relevant because their distinct mechanisms—CBT’s focus on restructuring maladaptive cognitions and behaviors versus SFBT’s emphasis on solution-building and strengths—offer complementary approaches to addressing the same psychological outcomes. Understanding their relative efficacy can elucidate whether a problem-focused or solution-focused approach is better suited to this population’s needs, informing tailored clinical interventions. While both CBT and SFBT have demonstrated considerable effectiveness in various clinical contexts (Stiede et al., 2023; Żak & Pękala, 2024), a direct comparative study within this specific population and explicitly examining these particular outcomes remains essential. Understanding the relative efficacy and potential differential benefits of these two distinct therapeutic approaches can critically inform clinical practice, optimize resource allocation within mental health services, and facilitate the development of more precisely tailored treatment programs for this highly vulnerable demographic.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sampling

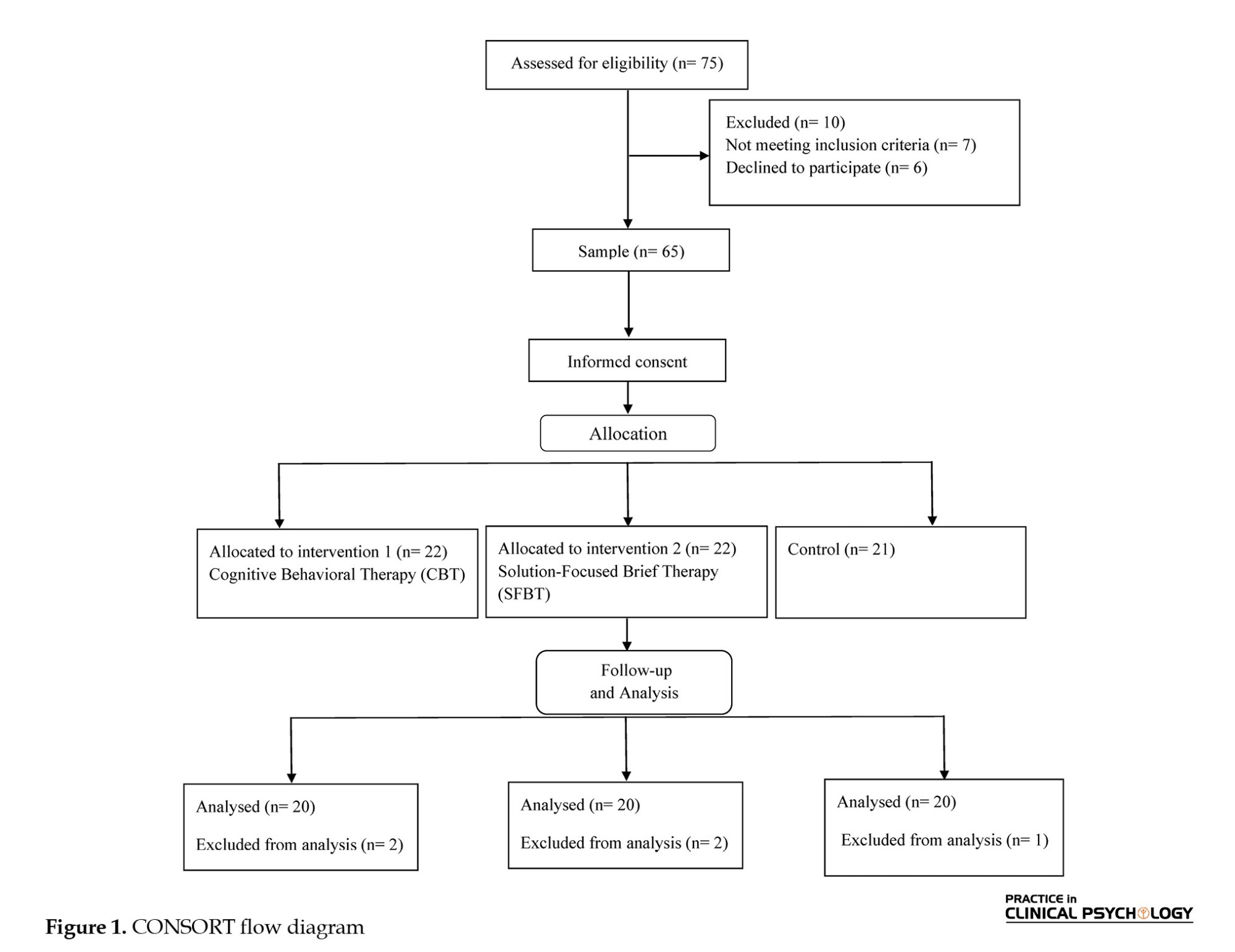

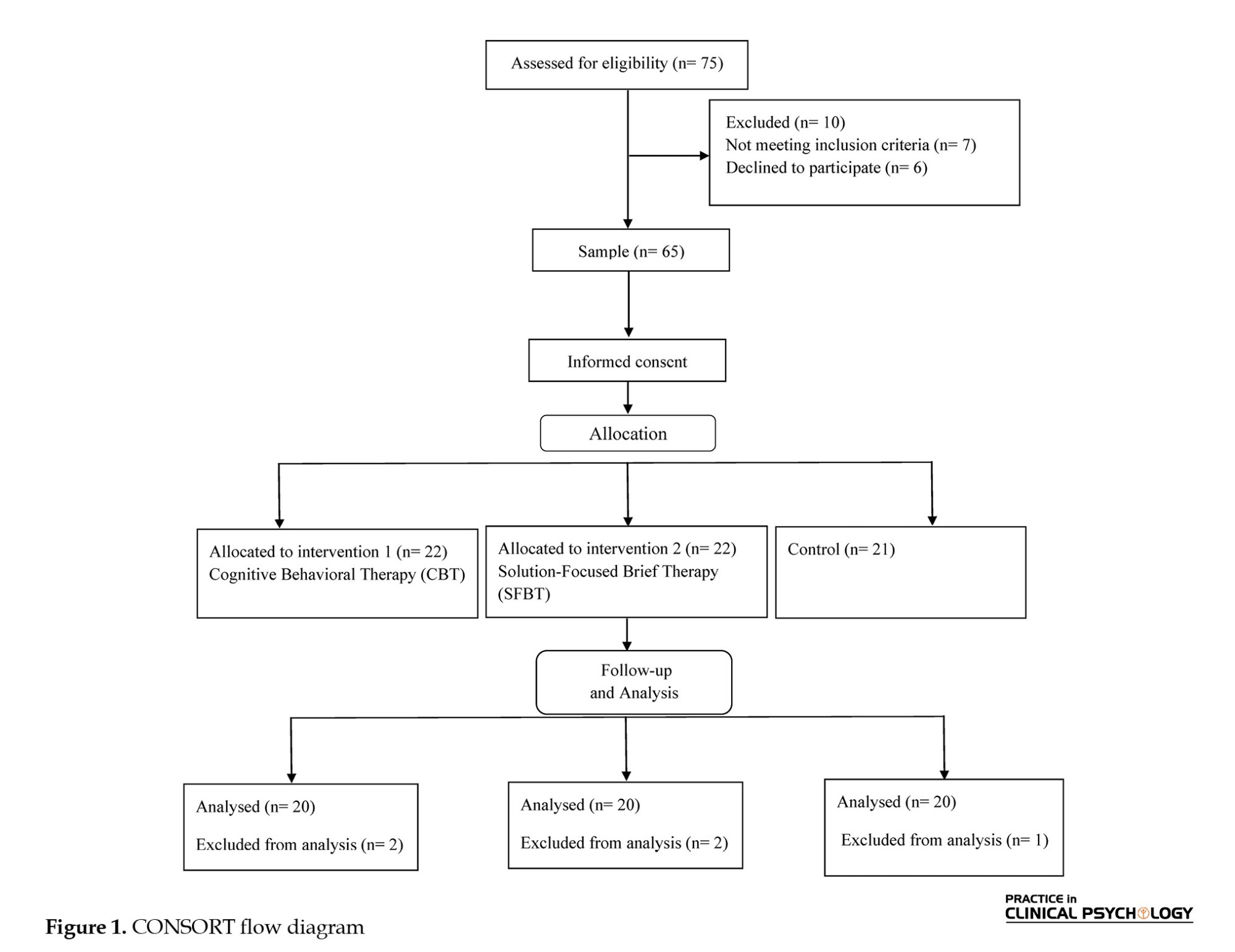

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design with pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up assessments, including a non-intervention control group. The target population comprised adolescent girls aged 12–16 years from divorced families living in Izeh City, Iran, during the 2023–2024 academic year. Sixty participants were purposively recruited through announcements at local schools and community centers, targeting girls whose parents had been divorced for at least one year. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to three groups (n=20 each: CBT, SFBT, and control) using a computer-generated random number sequence. Allocation concealment was achieved using sealed, opaque envelopes prepared by an independent researcher. The sample size (n=60) was calculated to achieve 80% power to detect a moderate effect size (f=0.25) at α=0.05, based on prior studies of CBT and SFBT (Karababa, 2023). The inclusion criteria included female gender, aged 12–16 years, parental divorce for at least one year, willingness to participate, and ability to complete questionnaires. The exclusion criteria included severe psychiatric diagnoses (assessed via clinical interview using diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria), concurrent psychological interventions, significant cognitive impairment, or missing more than two therapy sessions—a clinical psychologist screened for severe diagnoses during recruitment. A CONSORT-style flow diagram (Figure 1) details participant flow: 75 girls were assessed for eligibility, 10 were excluded (5 for severe diagnoses, 5 declined participation), 5 dropped out post-randomization (2 CBT, 2 SFBT, 1 control), and 55 were analyzed (intention-to-treat). Missing data were handled using the last observation carried forward. The control group received regular check-ins and psychoeducational materials on stress management, with a post-study workshop offered.

Study instruments

The cognitive avoidance questionnaire (CAQ; Sexton & Dugas, 2008) is a 25-item measure assessing cognitive avoidance across five subscales (anxious rumination, situational avoidance, imagery-to-verbal transformation, positive thought substitution, distractibility). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1= “completely incorrect” to 5= “completely correct”; range: 25–125, higher scores indicate greater avoidance). A validated Persian version was used, with translation and back-translation following standard procedures (Mohammadian et al., 2021). In this sample, the Cronbach α equals 0.81.

The perceived stress scale (PSS-10; Cohen et al., 1983) is a 10-item measure of subjective stress appraisal, scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0= “never” to 4= “very often”; range: 0–40, higher scores indicate greater stress). Four items are reverse-scored. A validated Persian version was used (Khalili et al., 2017), with Cronbach α=0.74 in this sample.

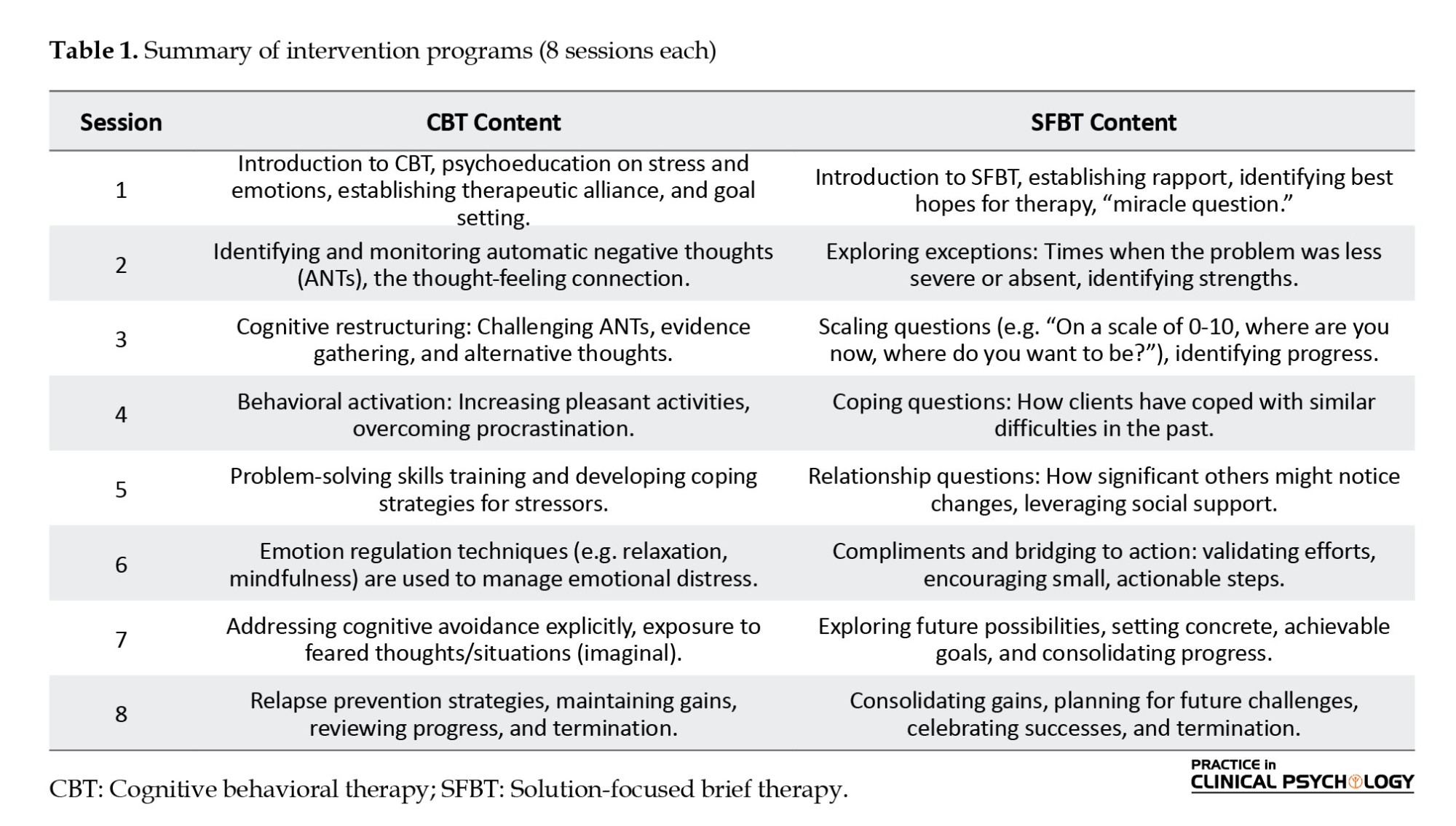

Intervention programs

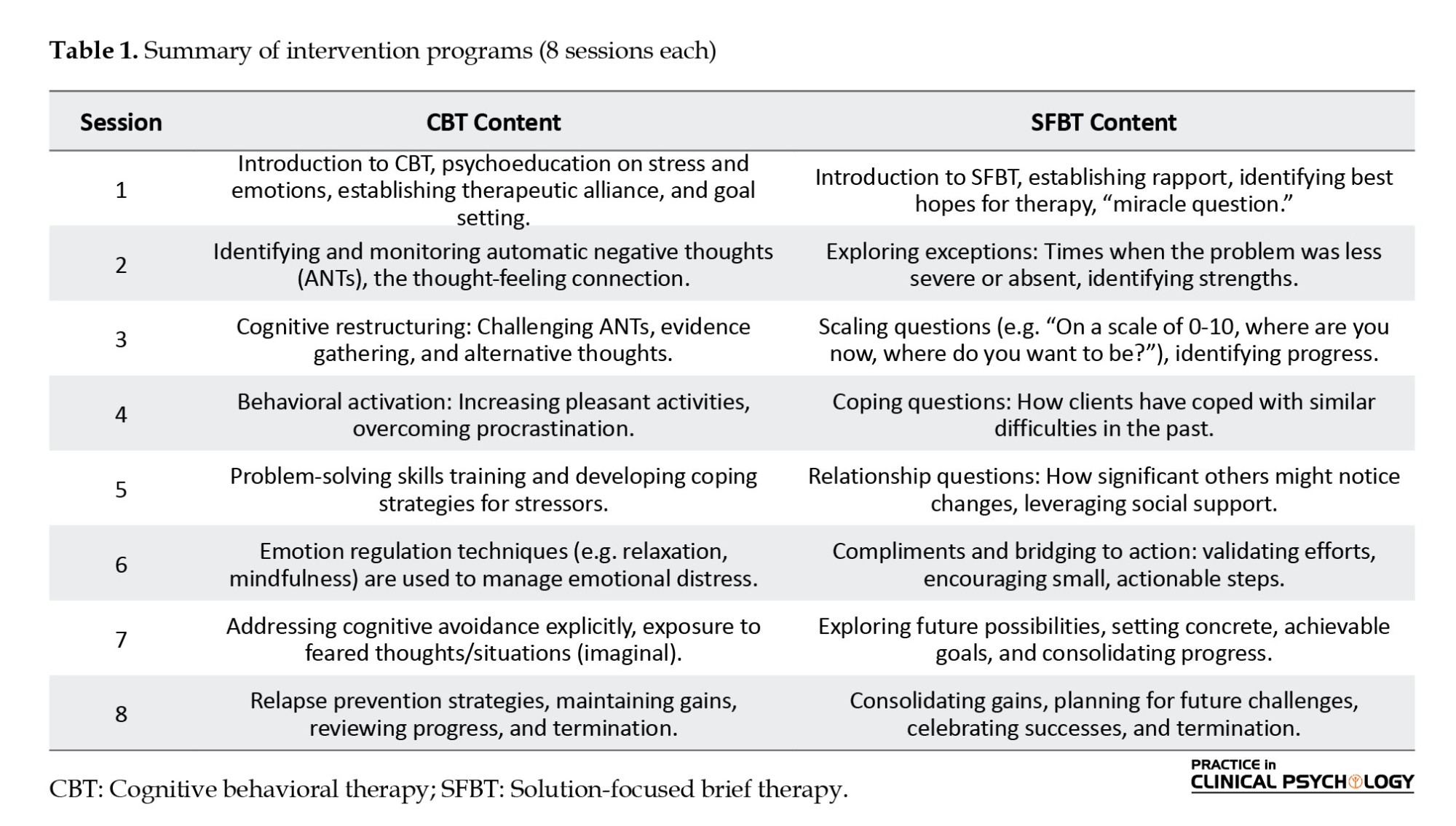

The CBT intervention followed a manualized protocol (Halder & Mahato, 2019), delivered over eight 90-minute sessions by a licensed clinical psychologist (PhD, trained in CBT and SFBT) with weekly supervision. The SFBT intervention adhered to a manualized protocol (Reddy et al., 2015), also delivered over eight 90-minute sessions by the same psychologist (Table 1). Session length was chosen to allow sufficient time for skill-building and discussion, with attendance encouraged through reminders and rapport-building. Treatment fidelity was ensured by recording sessions, with 20% randomly reviewed using adherence checklists. The control group received no intervention during the study but had access to standard school counseling services. A post-study psychoeducational workshop was provided to controls.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 26—descriptive statistics summarized sample characteristics. Baseline equivalence was assessed using ANOVA and chi-square tests. Repeated measures ANOVA evaluated intervention effects, with Mauchly’s test assessing sphericity (P>0.05, no Greenhouse-Geisser correction needed). Degrees of freedom, F statistics, exact P, and ηp2 effect sizes (small=0.01, medium=0.06, large=0.14) were reported. Post hoc Bonferroni tests included mean differences, standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals, and Cohen’s d effect sizes (small=0.2, medium=0.5, large=0.8). Significance was set at P<0.05. Analyses were intention-to-treat, with missing data handled via last observation carried forward.

Results

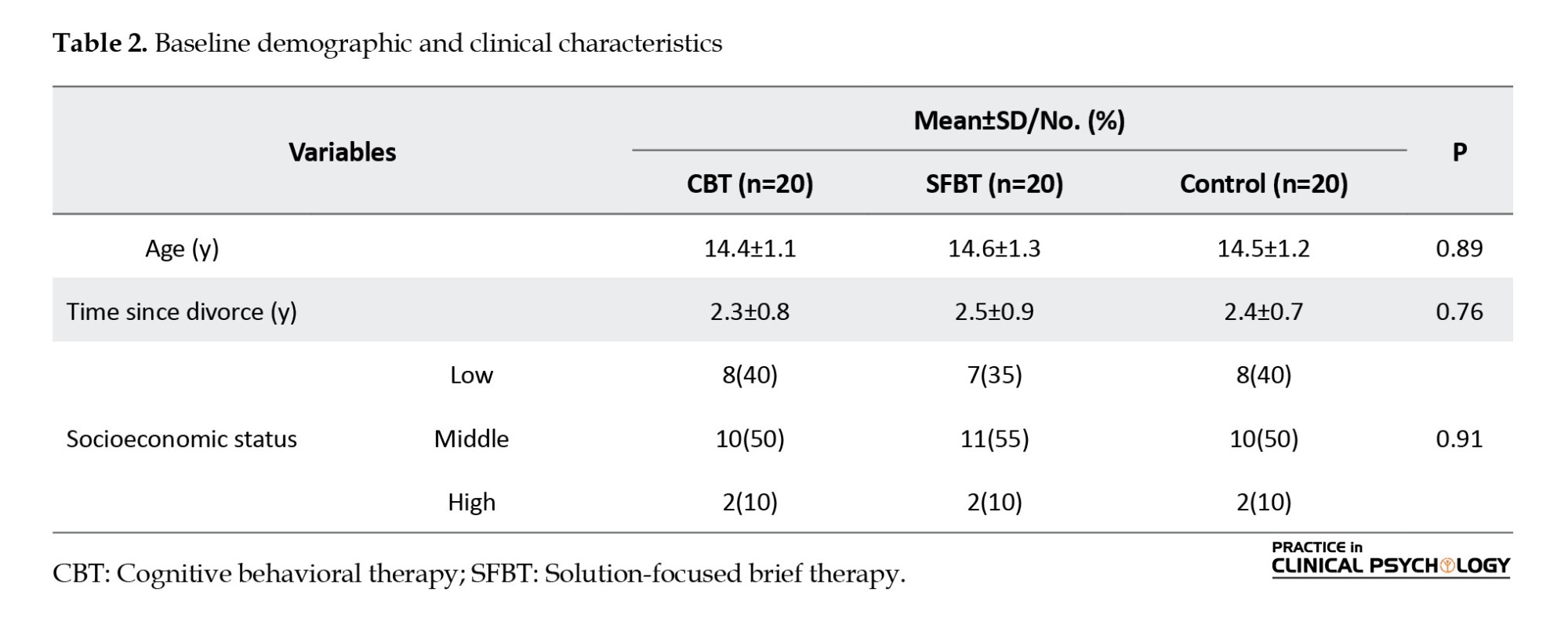

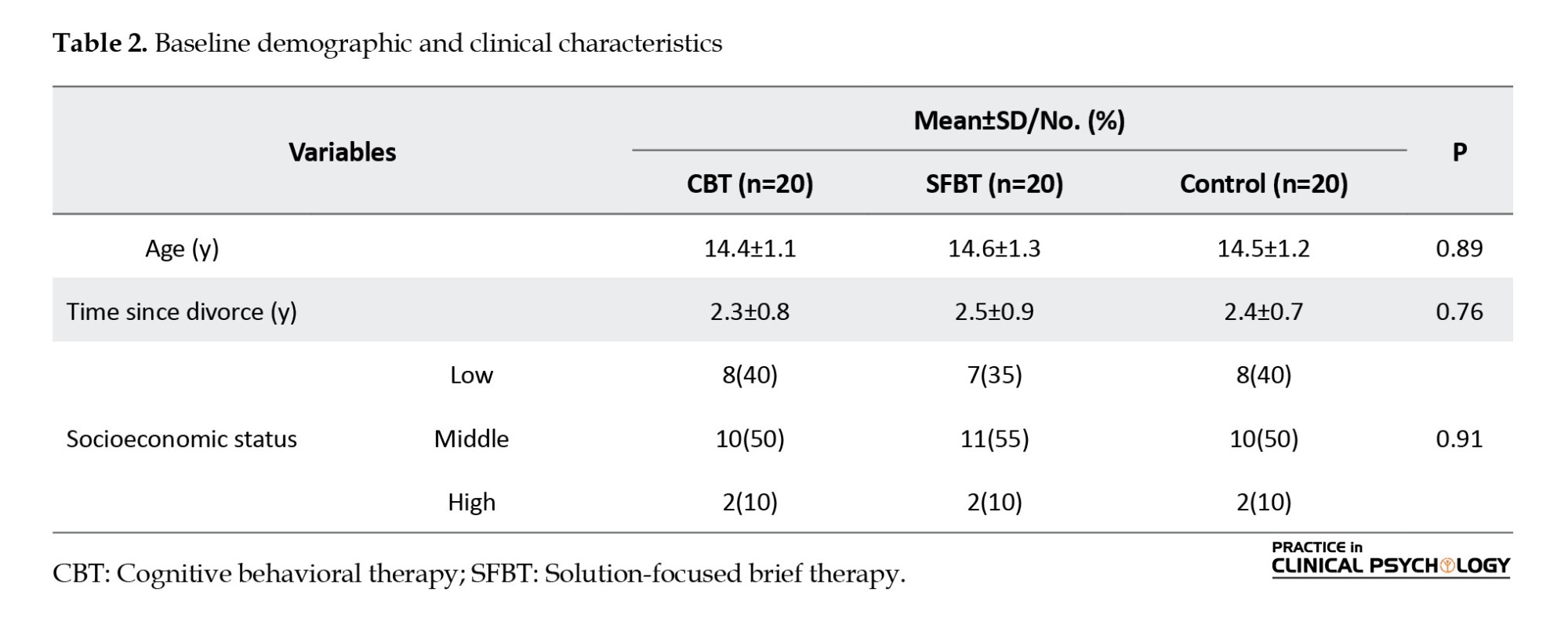

Table 2 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, confirming group equivalence (all P>0.05). The study included 60 adolescent girls (mean age=14.5±1.2 years).

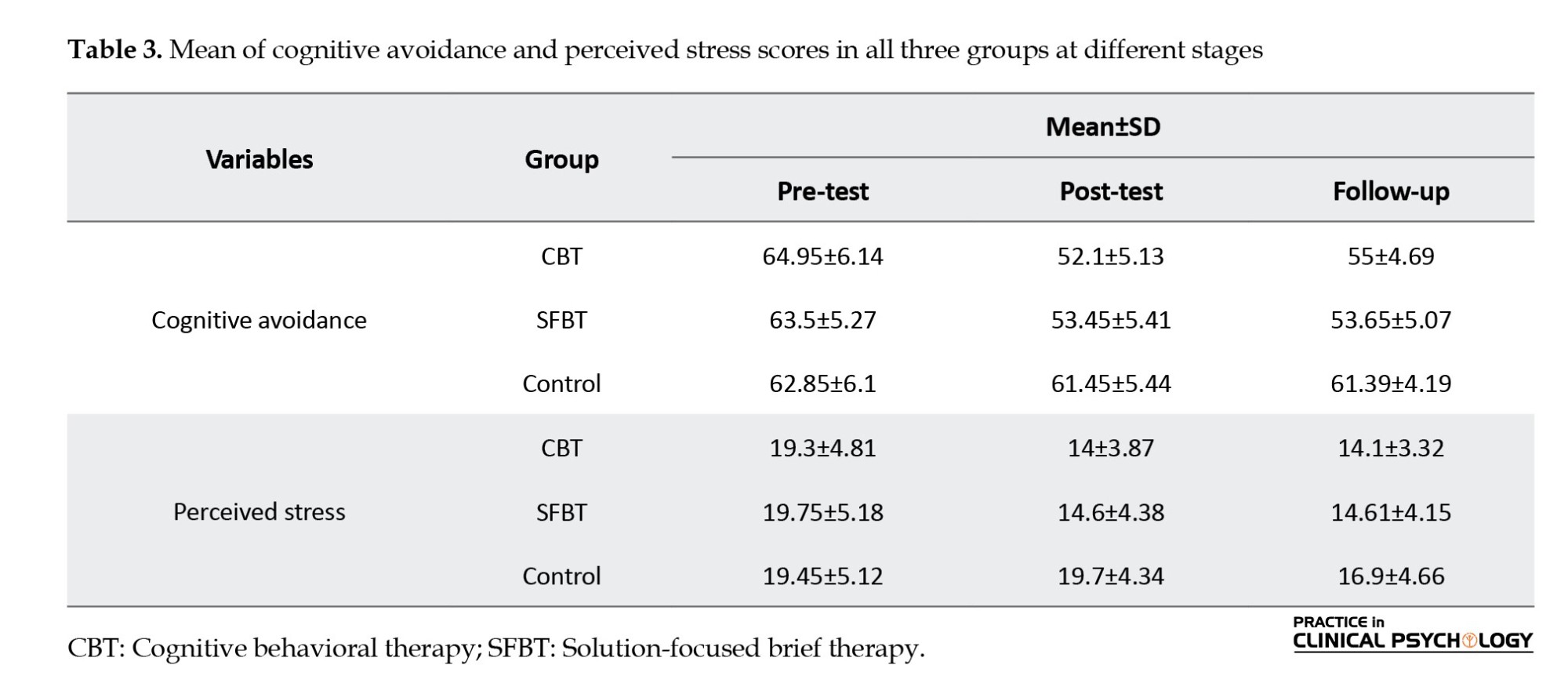

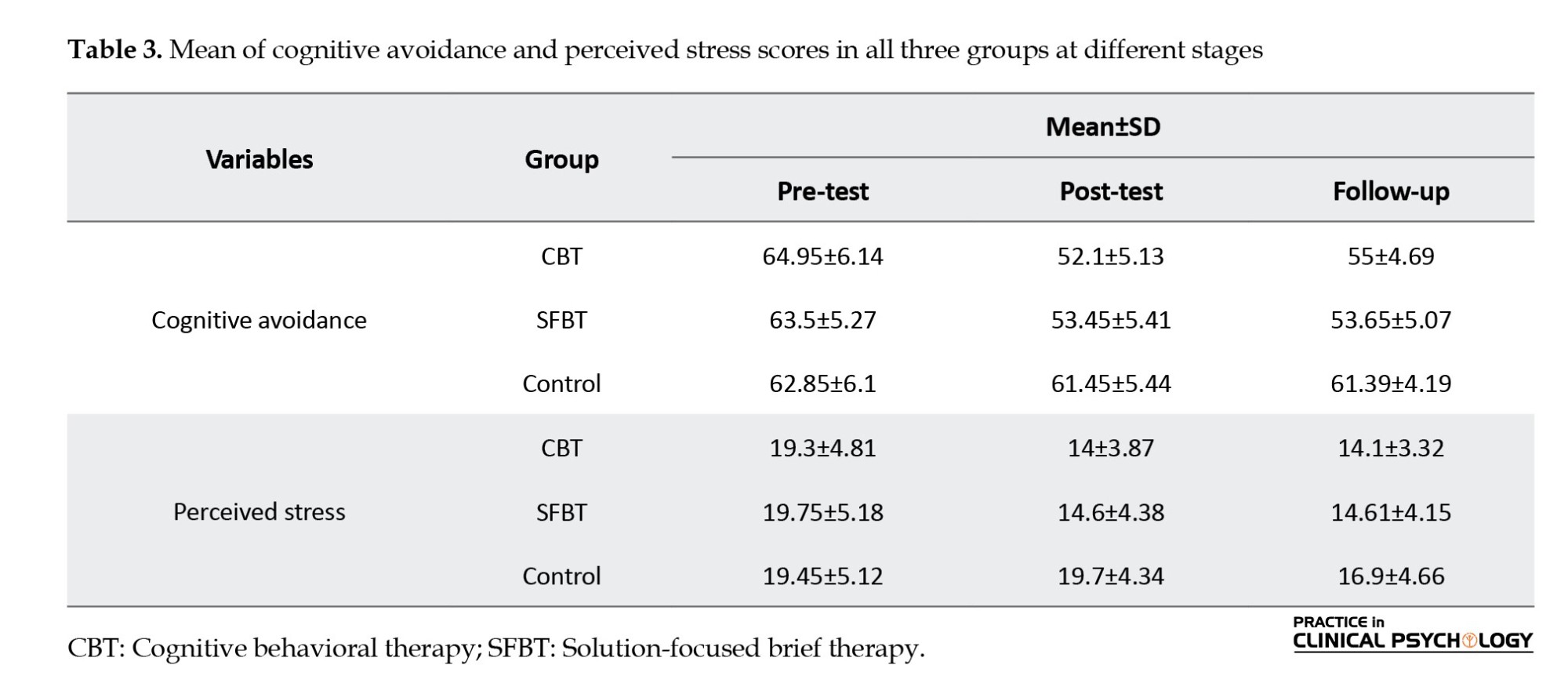

Table 3 shows Mean±SD for cognitive avoidance and perceived stress across groups at pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up (CBT: n=20, SFBT: n=20, Control: n=20 at all time points, with 5 dropouts imputed). Both CBT and SFBT groups showed significant reductions in cognitive avoidance and perceived stress from pre-test to post-test, sustained at follow-up. The control group showed a modest decrease in perceived stress at follow-up (16.90 vs 19.45), but this was not statistically significant (P=0.12).

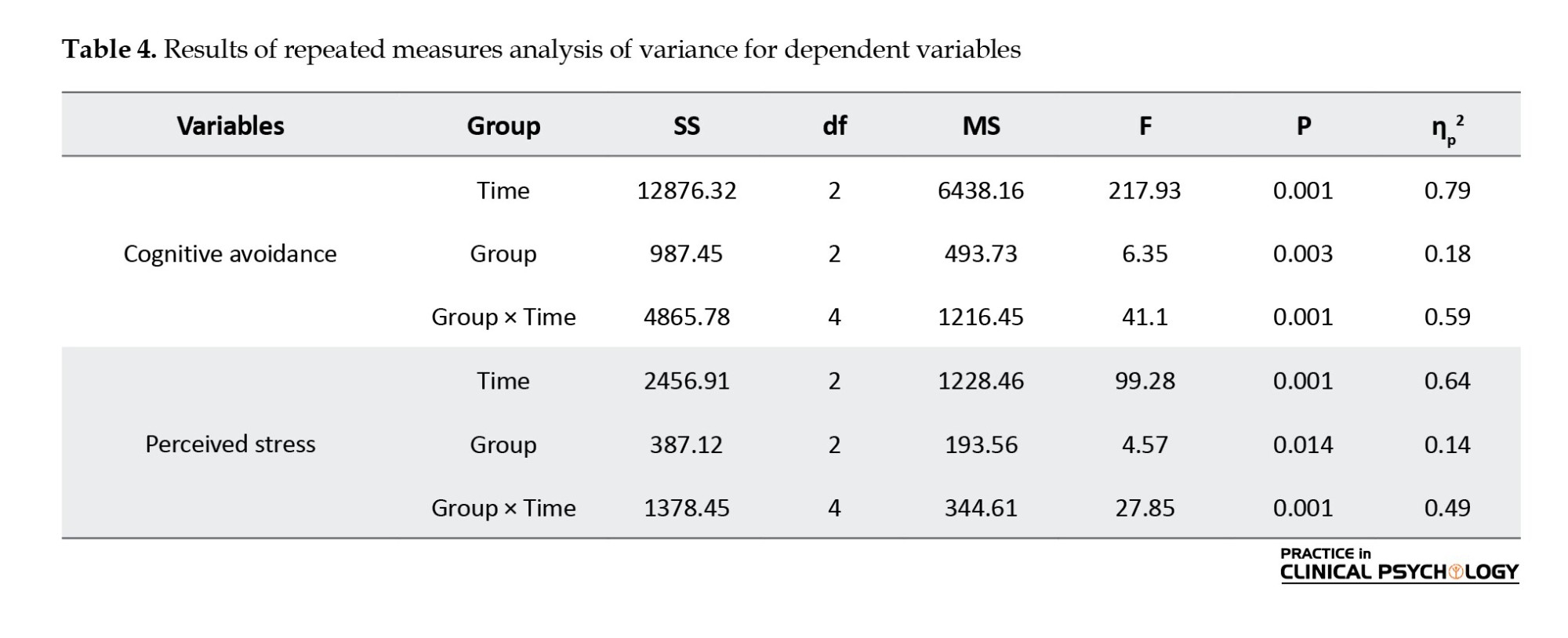

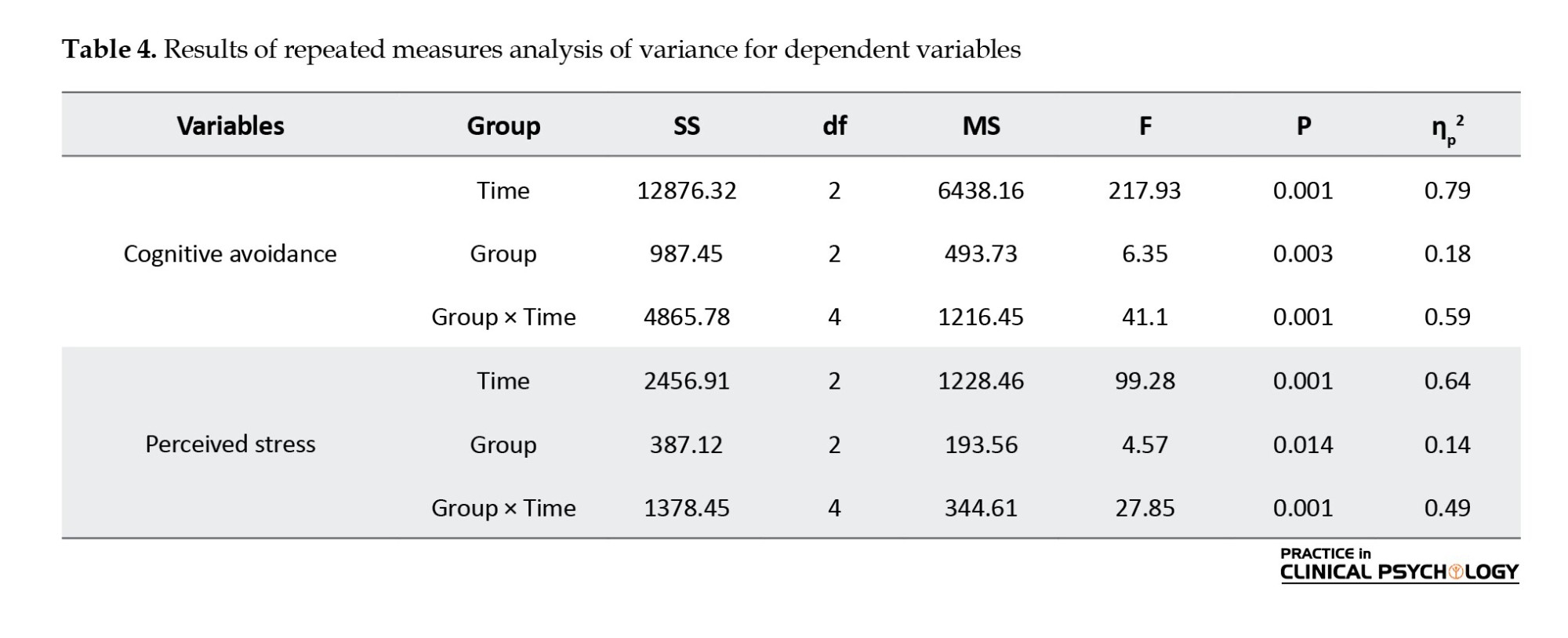

Assumptions of normality (the Shapiro-Wilk test, P>0.05), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P>0.05), and sphericity (Mauchly’s, P>0.05) were met. Repeated measures ANOVA for cognitive avoidance showed significant effects for time (F=217.93, P<0.001, ηp2=0.79, large), group (F=6.35, P=0.003, ηp2=0.18, large), and time × group interaction (F=41.10, P<0.001, partial η²=0.59, large). For perceived stress, significant effects were found for time (F=99.28, P<0.001, ηp2=0.64, large), group (F=4.57, P=0.014, ηp2=0.14, large), and time × group interaction (F=27.85, P<0.001, ηp2 =0.49, large) (Table 4).

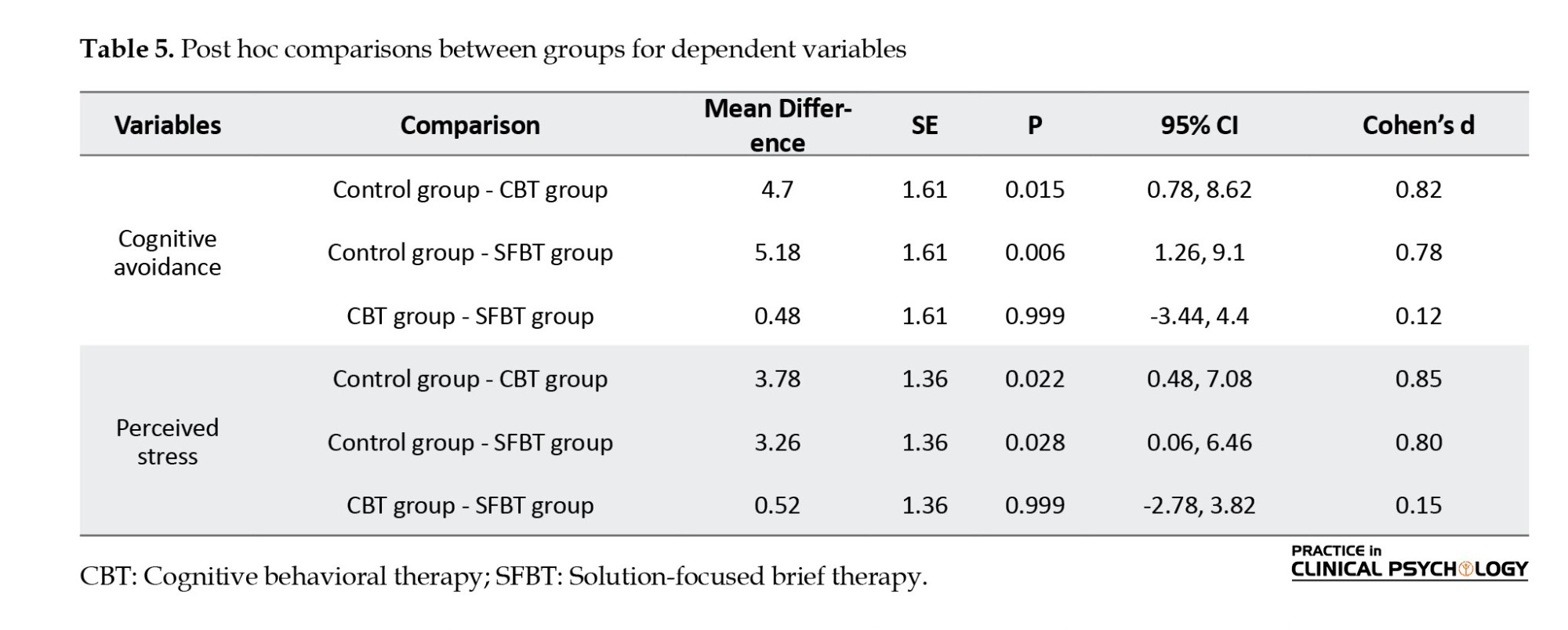

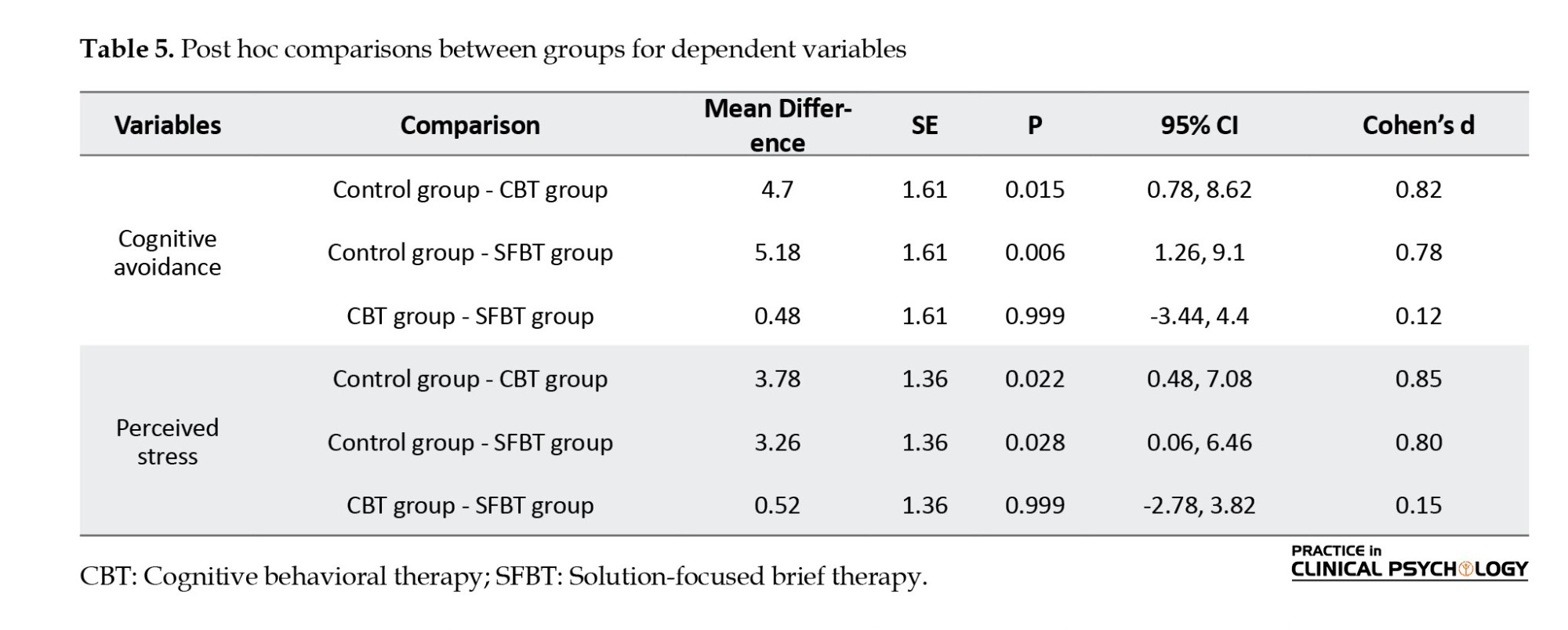

Bonferroni post hoc tests (Table 5) showed that for cognitive avoidance, CBT (Mean±SE 9.35±1.61; P=0.015; 95% CI, 0.78%, 8.62%; Cohen’s d=0.82; large) and SFBT (Mean±SE 8±1.61; P=0.006; 95% CI, 1.26%, 9.10%; Cohen’s d=0.78; large) outperformed the control group (control minus intervention). No significant difference was found between CBT and SFBT (Mean±SE 1.35±1.61; P=1.00; 95% CI, -3.44%, 4.4%]; Cohen’s d=0.12; small). For perceived stress, CBT (Mean±SE 5.7±1.36; P=0.022; 95% CI, 0.48%, 7.08%]; Cohen’s d=0.85; large) and SFBT (Mean±SE 5.1±1.36; P=0.028; 95% CI, 0.06%, 6.46%]; Cohen’s d=0.80; large) outperformed the control group. No significant difference was found between CBT and SFBT (Mean±SE 0.60±1.36; P=1.00; 95% CI, -2.78%, 3.82%; Cohen’s d=0.15; small).

Discussion

This study rigorously investigated the comparative efficacy of CBT and SFBT in ameliorating cognitive avoidance and perceived stress among adolescent girls navigating the complexities of parental divorce. The findings suggest that both therapeutic approaches significantly reduced cognitive avoidance and perceived stress, with these beneficial effects sustained at the three-month follow-up assessment. Importantly, these beneficial effects were largely sustained at the 3-month follow-up assessment. A critical observation was that while both interventions consistently outperformed the control group, no statistically significant difference in their respective efficacies was discernible between CBT and SFBT.

The observed effectiveness of CBT aligns seamlessly with its well-established theoretical underpinnings, which posit that psychological distress often arises from maladaptive thought patterns and acquired unhelpful behaviors (Ryum & Nikolaos, 2024). Adolescents contending with parental divorce frequently develop distorted cognitions concerning family transitions, harbor self-blame, or engage in catastrophic interpretations of future adversities, alongside employing maladaptive coping mechanisms such as cognitive avoidance (Cao et al., 2022). CBT directly addresses these challenges by empowering participants to identify, scrutinize, and ultimately restructure their negative automatic thoughts. By facilitating the development of more adaptive cognitive schemas and introducing practical behavioral strategies for emotional regulation and problem-solving, CBT equips adolescents with tangible tools to manage their internal experiences and external stressors proactively. The documented reduction in cognitive avoidance likely signifies an enhanced willingness and capacity to process difficult emotions and thoughts, rather than suppress them, thereby leading to a concurrent decrease in perceived stress as their coping repertoire is expanded (Stiede et al., 2023).

In a parallel vein, the significant positive outcomes associated with SFBT underscore the profound influence of its distinctive, strength-based paradigm. Diverging from traditional problem-focused approaches, SFBT intentionally redirects the therapeutic focus towards recognizing and amplifying clients’ existing resources, prior successes, and desired future states (Reddy et al., 2015). For adolescents grappling with the often overwhelming and disempowering repercussions of divorce, SFBT’s emphasis on solution-construction, rather than problem-deconstruction, can be profoundly empowering. Techniques such as the “miracle question” and “scaling questions” actively cultivate a future-oriented perspective, ignite hope, and foster a heightened sense of personal agency by highlighting incremental, achievable steps toward preferred outcomes (Żak & Pękala, 2024). This deliberate focus on internal capabilities and leveraging external supports likely fortified the adolescents’ sense of self-efficacy and resilience, consequently diminishing their reliance on cognitive avoidance and mitigating their overall experience of stress.

The finding that both CBT and SFBT yielded statistically comparable and significant reductions in cognitive avoidance and perceived stress is particularly noteworthy within the broader landscape of psychotherapy outcome research. This equipotentiality may be attributed to several factors, including shared therapeutic elements and contextual influences. Both CBT and SFBT foster a strong therapeutic alliance, instill hope, and promote expectations of positive change, which are well-documented common factors contributing to therapeutic success across modalities (Farimanian & Bayazi, 2024). Additionally, the short duration of both interventions (8 sessions) may have equalized their impact, as brief therapies often yield rapid improvements in symptom-focused outcomes like cognitive avoidance and perceived stress, particularly in motivated populations such as adolescents seeking support post-divorce (Karababa, 2023). Cultural factors specific to Izeh, Iran, such as collectivist values emphasizing family and community support, may have enhanced the effectiveness of SFBT’s strengths-based approach, which leverages existing social resources. At the same time, CBT’s structured problem-solving resonated with participants’ desire for clear coping strategies in a high-stress context (Mohammadian et al., 2021). Furthermore, SFBT’s brevity and focus on immediate, actionable goals may enhance its scalability in resource-constrained settings, such as community mental health programs in Iran, where fewer sessions and less intensive training requirements could make it more feasible for widespread implementation compared to CBT, which often requires more extensive therapist training and session time (Reddy et al., 2015).

These findings make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge concerning effective therapeutic interventions for adolescents impacted by parental divorce. They unequivocally reaffirm the critical necessity for comprehensive mental health support during this sensitive developmental juncture and specifically delineate cognitive avoidance and perceived stress as pivotal targets for therapeutic intervention. From a theoretical standpoint, the results lend support to both cognitive and solution-focused models of psychological change, suggesting that multiple, distinct pathways can converge to yield improved mental health outcomes. Furthermore, the demonstrated sustained effects at the three-month follow-up underscore the enduring nature of the coping strategies acquired and emphasize the paramount importance of empowering adolescents with practical tools that can be independently utilized beyond the confines of the therapeutic setting.

This study, despite its strengths, has limitations impacting generalizability. The sample was restricted to adolescent girls aged 12-16 years from Izeh, Iran, limiting applicability to other demographics or cultural contexts. Reliance on self-report measures for cognitive avoidance and perceived stress introduces potential response bias. Additional limitations include the small sample size from a single site, which may not capture regional or cultural variations, and the exclusive focus on female participants, which precludes insights into the experiences of male or non-binary adolescents. The absence of blinded assessment may have introduced bias in outcome measurement, and the three-month follow-up period is relatively short, limiting conclusions about long-term efficacy. Future research should address these limitations by employing larger, multi-site randomized controlled trials that include male and older adolescents to enhance generalizability. Incorporating objective outcome measures, such as behavioral observations or physiological stress indicators, could reduce reliance on self-reports. Longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods (e.g. 12–24 months) are needed to assess the durability of intervention effects. Additionally, mediator and moderator analyses could elucidate specific mechanisms of change (e.g. therapeutic alliance, cognitive restructuring) and identify which adolescents benefit most from each intervention.

From a clinical perspective, these findings support the integration of both CBT and SFBT into mental health services for adolescent girls from divorced families. CBT could be implemented in settings with access to trained psychologists, leveraging its structured approach to teach cognitive and behavioral skills in school-based or clinical counseling programs. SFBT, given its brevity and lower training demands, may be particularly suitable for community-based interventions or settings with limited resources, such as rural areas like Izeh, where access to specialized mental health professionals is often restricted. To adopt these interventions, mental health services could train school counselors in SFBT protocols to deliver brief, solution-focused sessions. At the same time, CBT could be prioritized in clinical settings with more resources for intensive therapy. Resource considerations include the need for ongoing supervision for therapists, particularly for CBT, and the potential for group-based delivery of both interventions to enhance cost-effectiveness and reach. These practical steps could ensure that adolescent girls receive timely, effective support to navigate the psychological challenges of parental divorce.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that both CBT and SFBT effectively reduce cognitive avoidance and perceived stress in adolescent girls from divorced families in Izeh, Iran, with sustained benefits at three months. The lack of significant differences between CBT and SFBT suggests both are viable options, though further research is needed to confirm their efficacy across diverse populations and longer timeframes. These findings advocate for the integration of CBT and SFBT into clinical practice to promote adaptive coping and psychological well-being in this vulnerable group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.409). Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians through signed consent forms after a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks. Adolescent participants provided assent via verbal agreement and signed forms, ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results, and manuscript drafting. Each author approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Divorce, as an increasingly prevalent global phenomenon, fundamentally alters the family’s core structure and significantly impacts its members. While adults navigate the complex dissolution of a marital bond, children, particularly adolescents, often disproportionately bear the psychological and social ramifications (Mentser & Sagiv, 2025). Adolescence itself is a pivotal developmental stage marked by profound physical, emotional, and cognitive transformations, rendering this demographic inherently susceptible to stressors that might be more readily managed by adults (Tullius et al., 2022). When the stability of the family unit, a primary crucible for psychological and social development, is disrupted by divorce, adolescents face an elevated risk for a myriad of maladjustment issues (Cao et al., 2022). Adolescent girls were selected as the focus of this study due to evidence indicating their heightened emotional vulnerability to parental divorce compared to boys. Research suggests that girls tend to internalize emotional distress more frequently, manifesting in higher rates of anxiety, depression, and cognitive avoidance, potentially due to gender-specific socialization patterns that emphasize emotional expressiveness and relational sensitivity (Rejaan et al., 2024; Amato & Keith, 1991). These internalizing behaviors necessitate targeted interventions tailored to their unique psychological needs, justifying the focus on this demographic to address their specific challenges effectively.

One prominent psychological consequence frequently observed in children of divorce is cognitive avoidance. This construct refers to a diverse suite of mental strategies employed to evade confronting undesirable thoughts, feelings, or memories (Godor et al., 2023). While ostensibly offering immediate relief from anxiety and distress, cognitive avoidance, in the long term, paradoxically perpetuates a vicious cycle of intensifying psychological problems (Eftekari & Bakhtiari, 2022). For adolescents grappling with the aftermath of divorce, cognitive avoidance plays a crucial, albeit often maladaptive, role in emotion regulation and psychological adaptation, frequently culminating in significant difficulties across social interactions and academic performance (Shipp et al., 2025). This avoidance can manifest in various forms, including thought suppression, distraction, or the reframing of negative cognitions to escape emotional discomfort. However, by consistently evading direct engagement with their emotional landscape, adolescents may hinder their capacity to process traumatic experiences, develop effective coping mechanisms, and ultimately attain psychological well-being (Songco et al., 2020). The persistent reliance on cognitive avoidance thus poses a considerable barrier to healthy development and adjustment within a post-divorce environment.

Beyond cognitive avoidance, perceived stress constitutes another significant and often pervasive outcome of divorce. Perceived stress is not merely the objective presence of stressors but rather an individual’s subjective appraisal of their ability to cope with demanding life situations and challenges (Naeimijoo et al., 2021). For children of divorce, particularly adolescent girls, heightened levels of perceived stress can manifest as a range of distressing symptoms, including anxiety, depressive symptomatology, and sleep disturbances (Karhina et al., 2023). When individuals perceive their available resources as insufficient to meet the demands of stressful situations, this perceived stress is amplified, creating a detrimental feedback loop that further compromises their emotional and physical health (Thorsén et al., 2022). The inherent instability, pervasive uncertainty, and numerous changes associated with family restructuring post-divorce can create a fertile ground for elevated perceived stress, thereby necessitating effective strategies to bolster adolescents’ resilience and coping capabilities (Lengua et al., 1999). Addressing perceived stress is, therefore, paramount for fostering emotional regulation and promoting overall psychological health in this vulnerable group.

In light of the significant psychological challenges confronting adolescents from divorced families, the exploration of effective therapeutic interventions becomes critically important. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) stands out as a highly efficacious and empirically supported therapeutic approach, widely recognized for its effectiveness across a broad spectrum of psychological disorders (Farimanian & Bayazi, 2024). At its core, CBT operates on the fundamental premise that dysfunctional thoughts and maladaptive behaviors contribute significantly to emotional distress. This approach actively engages individuals in identifying and challenging negative thought patterns, developing more adaptive cognitive schemas, and acquiring practical coping skills to manage challenging emotions and situations (Halder & Mahato, 2019). CBT was selected for this study because its structured approach directly targets cognitive avoidance by promoting cognitive restructuring, which helps adolescents confront and reframe maladaptive thoughts related to divorce, thereby reducing avoidance behaviors. Additionally, CBT’s focus on developing coping skills is hypothesized to mitigate perceived stress by equipping adolescents with tools to manage stressors more effectively, enhancing their emotional regulation and resilience (Stiede et al., 2023).

Another promising intervention, solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), offers a distinct yet equally valuable approach to addressing psychological distress. Unlike traditional problem-focused therapies, SFBT is a short-term, goal-oriented modality that emphasizes the identification and amplification of clients’ existing strengths, resources, and successful past experiences (Reddy et al., 2015). Rather than dwelling on the origins of problems, SFBT encourages individuals to envision a desired future state and to identify concrete, achievable steps towards realizing their goals (Chen et al., 2023). Through innovative techniques such as the “miracle question” and “scaling questions,” SFBT helps adolescents construct alternative, more positive narratives, enhance their sense of self-efficacy, and cultivate hope for the future (Karababa, 2023). SFBT was chosen for comparison due to its strengths-based approach, which is hypothesized to reduce cognitive avoidance by fostering a forward-looking perspective that encourages adolescents to focus on solutions rather than suppressing distressing thoughts. By amplifying self-efficacy and leveraging existing coping resources, SFBT is expected to lower perceived stress by empowering adolescents to feel more in control of their emotional responses and future outcomes, particularly in the context of divorce-related challenges (Żak & Pękala, 2024).

Given the documented adverse impacts of cognitive avoidance and perceived stress on the mental health of adolescent girls affected by parental divorce, there is a clear and urgent need for empirically validated therapeutic interventions. The comparison of CBT and SFBT is particularly relevant because their distinct mechanisms—CBT’s focus on restructuring maladaptive cognitions and behaviors versus SFBT’s emphasis on solution-building and strengths—offer complementary approaches to addressing the same psychological outcomes. Understanding their relative efficacy can elucidate whether a problem-focused or solution-focused approach is better suited to this population’s needs, informing tailored clinical interventions. While both CBT and SFBT have demonstrated considerable effectiveness in various clinical contexts (Stiede et al., 2023; Żak & Pękala, 2024), a direct comparative study within this specific population and explicitly examining these particular outcomes remains essential. Understanding the relative efficacy and potential differential benefits of these two distinct therapeutic approaches can critically inform clinical practice, optimize resource allocation within mental health services, and facilitate the development of more precisely tailored treatment programs for this highly vulnerable demographic.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sampling

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design with pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up assessments, including a non-intervention control group. The target population comprised adolescent girls aged 12–16 years from divorced families living in Izeh City, Iran, during the 2023–2024 academic year. Sixty participants were purposively recruited through announcements at local schools and community centers, targeting girls whose parents had been divorced for at least one year. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to three groups (n=20 each: CBT, SFBT, and control) using a computer-generated random number sequence. Allocation concealment was achieved using sealed, opaque envelopes prepared by an independent researcher. The sample size (n=60) was calculated to achieve 80% power to detect a moderate effect size (f=0.25) at α=0.05, based on prior studies of CBT and SFBT (Karababa, 2023). The inclusion criteria included female gender, aged 12–16 years, parental divorce for at least one year, willingness to participate, and ability to complete questionnaires. The exclusion criteria included severe psychiatric diagnoses (assessed via clinical interview using diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria), concurrent psychological interventions, significant cognitive impairment, or missing more than two therapy sessions—a clinical psychologist screened for severe diagnoses during recruitment. A CONSORT-style flow diagram (Figure 1) details participant flow: 75 girls were assessed for eligibility, 10 were excluded (5 for severe diagnoses, 5 declined participation), 5 dropped out post-randomization (2 CBT, 2 SFBT, 1 control), and 55 were analyzed (intention-to-treat). Missing data were handled using the last observation carried forward. The control group received regular check-ins and psychoeducational materials on stress management, with a post-study workshop offered.

Study instruments

The cognitive avoidance questionnaire (CAQ; Sexton & Dugas, 2008) is a 25-item measure assessing cognitive avoidance across five subscales (anxious rumination, situational avoidance, imagery-to-verbal transformation, positive thought substitution, distractibility). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1= “completely incorrect” to 5= “completely correct”; range: 25–125, higher scores indicate greater avoidance). A validated Persian version was used, with translation and back-translation following standard procedures (Mohammadian et al., 2021). In this sample, the Cronbach α equals 0.81.

The perceived stress scale (PSS-10; Cohen et al., 1983) is a 10-item measure of subjective stress appraisal, scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0= “never” to 4= “very often”; range: 0–40, higher scores indicate greater stress). Four items are reverse-scored. A validated Persian version was used (Khalili et al., 2017), with Cronbach α=0.74 in this sample.

Intervention programs

The CBT intervention followed a manualized protocol (Halder & Mahato, 2019), delivered over eight 90-minute sessions by a licensed clinical psychologist (PhD, trained in CBT and SFBT) with weekly supervision. The SFBT intervention adhered to a manualized protocol (Reddy et al., 2015), also delivered over eight 90-minute sessions by the same psychologist (Table 1). Session length was chosen to allow sufficient time for skill-building and discussion, with attendance encouraged through reminders and rapport-building. Treatment fidelity was ensured by recording sessions, with 20% randomly reviewed using adherence checklists. The control group received no intervention during the study but had access to standard school counseling services. A post-study psychoeducational workshop was provided to controls.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 26—descriptive statistics summarized sample characteristics. Baseline equivalence was assessed using ANOVA and chi-square tests. Repeated measures ANOVA evaluated intervention effects, with Mauchly’s test assessing sphericity (P>0.05, no Greenhouse-Geisser correction needed). Degrees of freedom, F statistics, exact P, and ηp2 effect sizes (small=0.01, medium=0.06, large=0.14) were reported. Post hoc Bonferroni tests included mean differences, standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals, and Cohen’s d effect sizes (small=0.2, medium=0.5, large=0.8). Significance was set at P<0.05. Analyses were intention-to-treat, with missing data handled via last observation carried forward.

Results

Table 2 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, confirming group equivalence (all P>0.05). The study included 60 adolescent girls (mean age=14.5±1.2 years).

Table 3 shows Mean±SD for cognitive avoidance and perceived stress across groups at pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up (CBT: n=20, SFBT: n=20, Control: n=20 at all time points, with 5 dropouts imputed). Both CBT and SFBT groups showed significant reductions in cognitive avoidance and perceived stress from pre-test to post-test, sustained at follow-up. The control group showed a modest decrease in perceived stress at follow-up (16.90 vs 19.45), but this was not statistically significant (P=0.12).

Assumptions of normality (the Shapiro-Wilk test, P>0.05), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P>0.05), and sphericity (Mauchly’s, P>0.05) were met. Repeated measures ANOVA for cognitive avoidance showed significant effects for time (F=217.93, P<0.001, ηp2=0.79, large), group (F=6.35, P=0.003, ηp2=0.18, large), and time × group interaction (F=41.10, P<0.001, partial η²=0.59, large). For perceived stress, significant effects were found for time (F=99.28, P<0.001, ηp2=0.64, large), group (F=4.57, P=0.014, ηp2=0.14, large), and time × group interaction (F=27.85, P<0.001, ηp2 =0.49, large) (Table 4).

Bonferroni post hoc tests (Table 5) showed that for cognitive avoidance, CBT (Mean±SE 9.35±1.61; P=0.015; 95% CI, 0.78%, 8.62%; Cohen’s d=0.82; large) and SFBT (Mean±SE 8±1.61; P=0.006; 95% CI, 1.26%, 9.10%; Cohen’s d=0.78; large) outperformed the control group (control minus intervention). No significant difference was found between CBT and SFBT (Mean±SE 1.35±1.61; P=1.00; 95% CI, -3.44%, 4.4%]; Cohen’s d=0.12; small). For perceived stress, CBT (Mean±SE 5.7±1.36; P=0.022; 95% CI, 0.48%, 7.08%]; Cohen’s d=0.85; large) and SFBT (Mean±SE 5.1±1.36; P=0.028; 95% CI, 0.06%, 6.46%]; Cohen’s d=0.80; large) outperformed the control group. No significant difference was found between CBT and SFBT (Mean±SE 0.60±1.36; P=1.00; 95% CI, -2.78%, 3.82%; Cohen’s d=0.15; small).

Discussion

This study rigorously investigated the comparative efficacy of CBT and SFBT in ameliorating cognitive avoidance and perceived stress among adolescent girls navigating the complexities of parental divorce. The findings suggest that both therapeutic approaches significantly reduced cognitive avoidance and perceived stress, with these beneficial effects sustained at the three-month follow-up assessment. Importantly, these beneficial effects were largely sustained at the 3-month follow-up assessment. A critical observation was that while both interventions consistently outperformed the control group, no statistically significant difference in their respective efficacies was discernible between CBT and SFBT.

The observed effectiveness of CBT aligns seamlessly with its well-established theoretical underpinnings, which posit that psychological distress often arises from maladaptive thought patterns and acquired unhelpful behaviors (Ryum & Nikolaos, 2024). Adolescents contending with parental divorce frequently develop distorted cognitions concerning family transitions, harbor self-blame, or engage in catastrophic interpretations of future adversities, alongside employing maladaptive coping mechanisms such as cognitive avoidance (Cao et al., 2022). CBT directly addresses these challenges by empowering participants to identify, scrutinize, and ultimately restructure their negative automatic thoughts. By facilitating the development of more adaptive cognitive schemas and introducing practical behavioral strategies for emotional regulation and problem-solving, CBT equips adolescents with tangible tools to manage their internal experiences and external stressors proactively. The documented reduction in cognitive avoidance likely signifies an enhanced willingness and capacity to process difficult emotions and thoughts, rather than suppress them, thereby leading to a concurrent decrease in perceived stress as their coping repertoire is expanded (Stiede et al., 2023).

In a parallel vein, the significant positive outcomes associated with SFBT underscore the profound influence of its distinctive, strength-based paradigm. Diverging from traditional problem-focused approaches, SFBT intentionally redirects the therapeutic focus towards recognizing and amplifying clients’ existing resources, prior successes, and desired future states (Reddy et al., 2015). For adolescents grappling with the often overwhelming and disempowering repercussions of divorce, SFBT’s emphasis on solution-construction, rather than problem-deconstruction, can be profoundly empowering. Techniques such as the “miracle question” and “scaling questions” actively cultivate a future-oriented perspective, ignite hope, and foster a heightened sense of personal agency by highlighting incremental, achievable steps toward preferred outcomes (Żak & Pękala, 2024). This deliberate focus on internal capabilities and leveraging external supports likely fortified the adolescents’ sense of self-efficacy and resilience, consequently diminishing their reliance on cognitive avoidance and mitigating their overall experience of stress.

The finding that both CBT and SFBT yielded statistically comparable and significant reductions in cognitive avoidance and perceived stress is particularly noteworthy within the broader landscape of psychotherapy outcome research. This equipotentiality may be attributed to several factors, including shared therapeutic elements and contextual influences. Both CBT and SFBT foster a strong therapeutic alliance, instill hope, and promote expectations of positive change, which are well-documented common factors contributing to therapeutic success across modalities (Farimanian & Bayazi, 2024). Additionally, the short duration of both interventions (8 sessions) may have equalized their impact, as brief therapies often yield rapid improvements in symptom-focused outcomes like cognitive avoidance and perceived stress, particularly in motivated populations such as adolescents seeking support post-divorce (Karababa, 2023). Cultural factors specific to Izeh, Iran, such as collectivist values emphasizing family and community support, may have enhanced the effectiveness of SFBT’s strengths-based approach, which leverages existing social resources. At the same time, CBT’s structured problem-solving resonated with participants’ desire for clear coping strategies in a high-stress context (Mohammadian et al., 2021). Furthermore, SFBT’s brevity and focus on immediate, actionable goals may enhance its scalability in resource-constrained settings, such as community mental health programs in Iran, where fewer sessions and less intensive training requirements could make it more feasible for widespread implementation compared to CBT, which often requires more extensive therapist training and session time (Reddy et al., 2015).

These findings make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge concerning effective therapeutic interventions for adolescents impacted by parental divorce. They unequivocally reaffirm the critical necessity for comprehensive mental health support during this sensitive developmental juncture and specifically delineate cognitive avoidance and perceived stress as pivotal targets for therapeutic intervention. From a theoretical standpoint, the results lend support to both cognitive and solution-focused models of psychological change, suggesting that multiple, distinct pathways can converge to yield improved mental health outcomes. Furthermore, the demonstrated sustained effects at the three-month follow-up underscore the enduring nature of the coping strategies acquired and emphasize the paramount importance of empowering adolescents with practical tools that can be independently utilized beyond the confines of the therapeutic setting.

This study, despite its strengths, has limitations impacting generalizability. The sample was restricted to adolescent girls aged 12-16 years from Izeh, Iran, limiting applicability to other demographics or cultural contexts. Reliance on self-report measures for cognitive avoidance and perceived stress introduces potential response bias. Additional limitations include the small sample size from a single site, which may not capture regional or cultural variations, and the exclusive focus on female participants, which precludes insights into the experiences of male or non-binary adolescents. The absence of blinded assessment may have introduced bias in outcome measurement, and the three-month follow-up period is relatively short, limiting conclusions about long-term efficacy. Future research should address these limitations by employing larger, multi-site randomized controlled trials that include male and older adolescents to enhance generalizability. Incorporating objective outcome measures, such as behavioral observations or physiological stress indicators, could reduce reliance on self-reports. Longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods (e.g. 12–24 months) are needed to assess the durability of intervention effects. Additionally, mediator and moderator analyses could elucidate specific mechanisms of change (e.g. therapeutic alliance, cognitive restructuring) and identify which adolescents benefit most from each intervention.

From a clinical perspective, these findings support the integration of both CBT and SFBT into mental health services for adolescent girls from divorced families. CBT could be implemented in settings with access to trained psychologists, leveraging its structured approach to teach cognitive and behavioral skills in school-based or clinical counseling programs. SFBT, given its brevity and lower training demands, may be particularly suitable for community-based interventions or settings with limited resources, such as rural areas like Izeh, where access to specialized mental health professionals is often restricted. To adopt these interventions, mental health services could train school counselors in SFBT protocols to deliver brief, solution-focused sessions. At the same time, CBT could be prioritized in clinical settings with more resources for intensive therapy. Resource considerations include the need for ongoing supervision for therapists, particularly for CBT, and the potential for group-based delivery of both interventions to enhance cost-effectiveness and reach. These practical steps could ensure that adolescent girls receive timely, effective support to navigate the psychological challenges of parental divorce.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that both CBT and SFBT effectively reduce cognitive avoidance and perceived stress in adolescent girls from divorced families in Izeh, Iran, with sustained benefits at three months. The lack of significant differences between CBT and SFBT suggests both are viable options, though further research is needed to confirm their efficacy across diverse populations and longer timeframes. These findings advocate for the integration of CBT and SFBT into clinical practice to promote adaptive coping and psychological well-being in this vulnerable group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.409). Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians through signed consent forms after a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks. Adolescent participants provided assent via verbal agreement and signed forms, ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results, and manuscript drafting. Each author approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 26–46. [DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26]

Cao, H., Fine, M. A., & Zhou, N. (2022). The divorce process and child adaptation trajectory typology (DPCATT) model: The shaping role of predivorce and postdivorce interparental conflict. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25(3), 500-528. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-022-00379-3] [PMID]

Chen, S., Zhang, Y., Qu, D., He, J., Yuan, Q., & Wang, Y., ET AL. (2023). An online solution-focused brief therapy for adolescent anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 86, 103660. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103660] [PMID]

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385-396. [DOI:10.2307/2136404] [PMID]

Eftekari, A., & Bakhtiari, M. (2022). Comparing the effectiveness of schema therapy with acceptance and commitment therapy on cognitive avoidance in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 11. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.10.1.593.1]

Farimanian, S., & Bayazi, M. H. (2024). Effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral therapy on the psychological security of patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 12(4), 345. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.4.931.1]

Godor, B. P., van der Horst, F. C. P., & Van der Hallen, R. (2023). Unravelling the roots of emotional development: Examining the relationships between attachment, resilience and coping in young adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 44(4), 429-457. [DOI:10.1177/02724316231181876]

Halder, S., & Mahato, A. K. (2019). Cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: Challenges and gaps in practice. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 41(3), 279-283. [DOI:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_470_18] [PMID]

Karababa, A. (2023). A meta-analysis of solution-focused brief therapy for school-related problems in adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice, 34(2), 169-181. [DOI:10.1177/10497315231170865]

Karhina, K., Bøe, T., Hysing, M., & Nilsen, S. A. (2023). Parental separation, negative life events and mental health problems in adolescence. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2364. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-023-17307-x] [PMID]

Khalili, R., Sirati Nir, M., Ebadi, A., Tavallai, A., & Habibi, M. (2017). Validity and reliability of the Cohen 10-item Perceived Stress Scale in patients with chronic headache: Persian version. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 26, 136-140. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.01.010] [PMID]

Lengua, L. J., Sandler, I. N., West, S. G., Wolchik, S. A., & Curran, P. J. (1999). Emotionality and self-regulation, threat appraisal, and coping in children of divorce. Development and Psychopathology, 11(1), 15-37. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579499001935] [PMID]

Mentser, S., & Sagiv, L. (2025). Cultural and personal values interact to predict divorce. Communications Psychology, 3(1), 12. [DOI:10.1038/s44271-025-00185-x] [PMID]

Mohammadian, S., Asgari, P., Makvandi, B., & Naderi, F. (2021). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on anxiety, cognitive avoidance, and empathy of couples visiting counseling centers in Ahvaz City, Iran. Journal of Research & Health, 11(6), 393-402. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.11.6.1889.1]

Naeimijoo, P., Masjedi Arani, A., Bakhtiari, M., Mohammadi Farsani, G., & Yousefi, A. (2021). The relationship between covid-related psychological distress and perceived stress with emotional eating in Iranian adolescents: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 329. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.4.803.1]

Reddy, P. D., Thirumoorthy, A., Vijayalakshmi, P., & Hamza, M. A. (2015). Effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy for an adolescent girl with moderate depression. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 87-89. [DOI:10.4103/0253-7176.150849] [PMID]

Rejaan, Z., van der Valk, I., Schrama, W., & Branje, S. (2024). Parenting, coparenting, and adolescents’ sense of autonomy and belonging after divorce. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(6), 1454-1468. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-024-01963-2] [PMID]

Ryum, T., & Nikolaos, K. (2024). Elucidating the process-based emphasis in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 33, 100819. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2024.100819]

Sexton, K. A., & Dugas, M. J. (2008). The cognitive avoidance questionnaire: Validation of the English translation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(3), 355-370. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.005] [PMID]

Shipp, L., Leigh, E., Laverton, A., Percy, R., & Waite, P. (2025). Cognitive aspects of generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents: exploring intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive avoidance, and positive beliefs about worry. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 10.1007/s10578-025-01809-3. [DOI:10.1007/s10578-025-01809-3] [PMID]

Songco, A., Hudson, J. L., & Fox, E. (2020). A cognitive model of pathological worry in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(2), 229-249. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-020-00311-7] [PMID]

Stiede, J. T., Trent, E. S., Viana, A. G., Guzick, A. G., Storch, E. A., & Hershfield, J. (2023). Cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 543-558. [DOI:10.1016/j.chc.2022.12.001] [PMID]

Thorsén, F., Antonson, C., Palmér, K., Berg, R., Sundquist, J., & Sundquist, K. (2022). Associations between perceived stress and health outcomes in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(1), 75. [DOI:10.1186/s13034-022-00510-w] [PMID]

Tullius, J. M., De Kroon, M. L. A., Almansa, J., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2022). Adolescents’ mental health problems increase after parental divorce, not before, and persist until adulthood: A longitudinal TRAILS study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6), 969-978. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-020-01715-0] [PMID]

Żak, A. M., & Pękala, K. (2025). Effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychotherapy Research, 35(7), 1043-105. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2024.2406540] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/09/3 | Accepted: 2025/10/6 | Published: 2026/12/28

Received: 2025/09/3 | Accepted: 2025/10/6 | Published: 2026/12/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |