Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 83-92 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amiri N, Hafezi F, Sharifi Fard A, Asgari P. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Transdiagnostic Integrated Therapy on Emotional Expressivity in Women With Social Anxiety Disorder. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :83-92

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1053-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1053-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,dr.fariba.hafezi@iau.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychology, Ramh.C., Islamic Azad University, Ramhormoz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Ramh.C., Islamic Azad University, Ramhormoz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 806 kb]

(488 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (738 Views)

Full-Text: (280 Views)

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a prevalent mental health condition marked by an intense, persistent fear of social or performance situations, often leading to significant distress and impaired social functioning (Alomari et al., 2022). Individuals with SAD experience profound concerns about negative evaluation, judgment, or humiliation, which can result in avoidance of social interactions, diminished quality of life, and disruptions in career, education, and relationships (Penninx et al., 2021). Unlike typical shyness, SAD involves disproportionate anxiety that interferes with daily life, driven by cognitive processes such as hypervigilance for social threats, negative self-appraisals, and misinterpretation of ambiguous social cues as hostile (Sadrzadeh et al., 2024). Women are disproportionately affected by SAD, facing unique sociocultural pressures, particularly in contexts like Iran, where gender norms may exacerbate emotional suppression and social avoidance (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). This gender-specific burden highlights the need for targeted interventions to address emotional expression deficits in women with SAD, a population often underrepresented in comparative treatment research. Effective interventions are essential to help these individuals navigate social environments with greater confidence and authenticity.

Emotional expressivity, the outward display of internal emotional states through verbal and non-verbal cues like facial expressions and tone of voice, is a cornerstone of social communication but is frequently impaired in SAD (Naziri & Hooman, 2025). Fear of negative evaluation often leads individuals to suppress emotions, resulting in a restricted range of expression that others may misinterpret as aloofness, further isolating them (Xie & Wang, 2024). The emotional expressivity scale (EES) assesses this construct through subscales: Positive expressivity (e.g. joy, affection), negative expressivity (e.g. anger, sadness), and impulsivity, which measures uncontrolled emotional expression (Moghadam et al., 2025). Individuals with SAD often inhibit positive emotions, fearing they appear insincere, and suppress negative emotions to avoid seeming weak, leading to internal distress (Xu et al., 2025). Impulsivity is also restricted due to an intense need for control in social settings (Sağlam Topal & Yavuz Sever, 2024). This interplay between SAD and emotional expressivity underscores a critical gap in the literature: The lack of studies comparing therapeutic interventions that specifically target emotional expression deficits in women with SAD.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapy, promotes psychological flexibility by encouraging acceptance of internal experiences without judgment and commitment to value-driven actions (Mostafazadeh et al., 2024; Soltani et al., 2023). By reducing emotional avoidance, ACT may foster authentic emotional expression, crucial for social interactions (Caletti et al., 2022). Its efficacy in treating anxiety-related conditions suggests potential for addressing SAD’s emotional dysregulation (Khoramnia et al., 2020). Similarly, the unified protocol (UP) for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders targets shared emotional processes across disorders like anxiety and depression, using components like emotion psychoeducation, cognitive reappraisal, and emotion-driven action skills to enhance emotional competence (Barlow et al., 2017; Sakiris & Berle, 2019). UP’s focus on emotional regulation makes it particularly relevant for SAD, with evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing anxiety symptoms (Ghaderi et al., 2023; Rapee et al., 2023).

Despite the established efficacy of ACT and UP in reducing anxiety symptoms, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding their comparative effects on emotional expressivity in women with SAD. While both therapies address emotional dysregulation, no study has directly compared their impact on the EES subscales (positive, negative, and intimacy expressivity) in this population. This study addresses this gap through a novel, head-to-head comparison of ACT and UP, focusing on their ability to enhance emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The exclusive focus on women accounts for their higher SAD prevalence and the unique sociocultural factors, such as Iranian gender norms, that influence emotional expression (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). By examining whether these interventions yield sustained improvements in emotional expressivity, this research aims to inform clinical practice, offering evidence for tailored treatment strategies that enhance social functioning in this underserved population.

Materials and Methods

Participants and design

This study utilized a clinical trial with a pre-test-post-test with a 3-month follow-up design and one control group. The statistical population comprised all women diagnosed with SAD who sought treatment at counseling and psychology clinics in Ahvaz, Iran, in 2024. A convenience sample of 45 participants was selected, with the sample size determined using G*Power software to achieve 80% power for detecting a medium effect size (0.25) in repeated measures ANOVA, assuming α=0.05 and a correlation of 0.5 among repeated measures. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Being a woman between the ages of 20 and 40, having a diagnosis of SAD based on the structured clinical interview for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) (SCID-5), conducted by trained clinical psychologists, and a score above the clinical cutoff on the social phobia inventory (SPIN). The exclusion criteria included having a comorbid severe mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), receiving concurrent psychological treatment, a history of substance abuse, or missing more than two treatment sessions. The selected participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: The ACT group, the UP group, and a waiting-list control group, with 15 participants in each group.

Study procedure

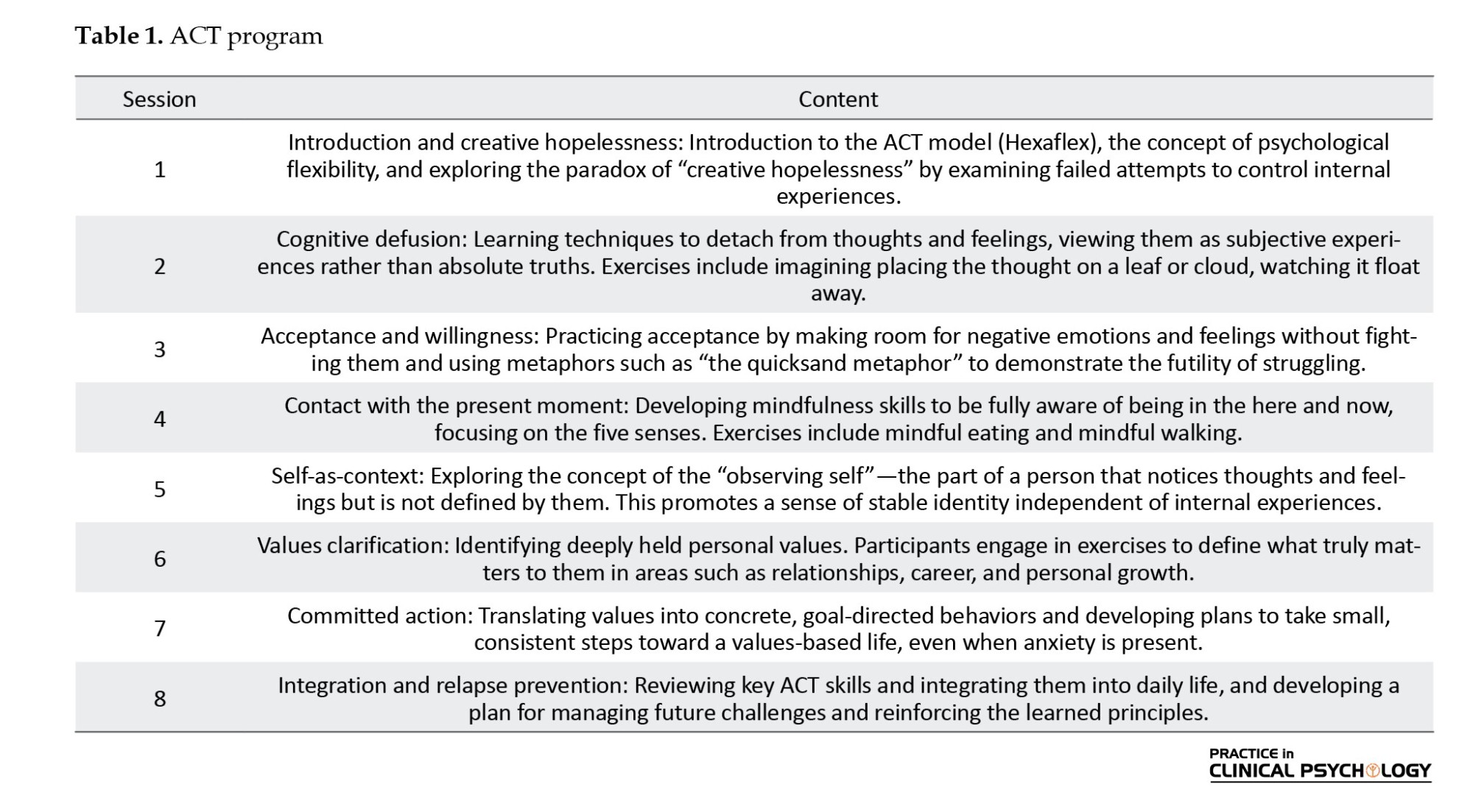

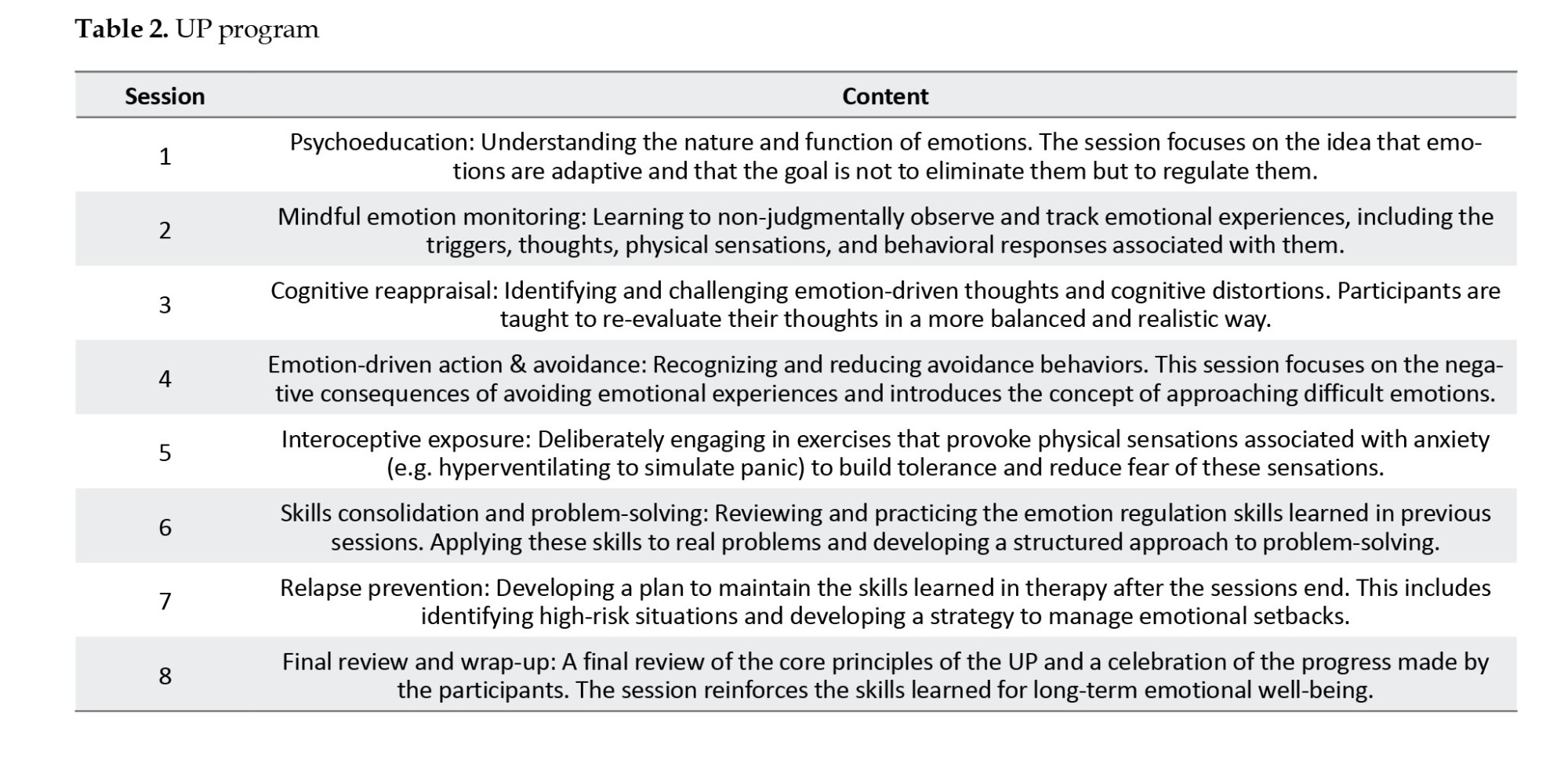

Before the intervention, all participants completed the EES. The experimental groups then participated in eight weekly 90-minute group therapy sessions. The ACT group received therapy based on the ACT manual, while the UP group received therapy based on the UP for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders manual. Detailed session content for both interventions is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The control group did not receive any intervention during this period and was placed on a waiting list. At the conclusion of the therapy sessions (post-test), all participants again completed the EES. A final assessment was conducted three months after the post-test (follow-up) for all groups to evaluate the long-term effects of the interventions.

Research tools

EES

EES is a 16-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure an individual’s outward expression of emotion. It assesses three subscales: Positive expressivity (7 items), intimacy expressivity (5 items), and negative expressivity (4 items). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (not at all true of me) to 7 (very true of me). Higher scores indicate greater emotional expressivity. The items related to the negative expressivity subscale are scored in reverse (King & Emmons, 1990). In Persian studies, the EES has demonstrated good reliability and validity, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.75 to 0.89 (Kargar et al., 2023). In the present study, the Cronbach α for the total EES was 0.87, with subscale alphas of 0.82 for positive expressivity, 0.8 for intimacy expressivity, and 0.79 for negative expressivity, indicating high internal consistency across all subscales.

Intervention program

The ACT intervention consisted of 8 weekly group sessions, each lasting 90 minutes. The sessions were based on the ACT hexaflex model, focusing on key psychological flexibility processes (McHugh, 2011). The UP intervention also comprised eight weekly group sessions, each lasting 90 minutes. The sessions focused on five core emotional competencies, as outlined in the UP manual (Barlow et al., 2017). A summary of the ACT and UP intervention sessions is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sample characteristics. To test the hypotheses, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine the effectiveness of the interventions and their long-term effects on the EES scores. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

The study included 45 women diagnosed with SAD, randomly assigned to three groups: ACT, UP, and one control group, each comprising 15 participants. The mean age was 31.60±6.35 years for the ACT group, 32.02±5.91 years for the UP group, and 31.79±5.34 years for the control group, indicating comparable age distributions. Marital status across groups showed the ACT group had 7 single (46.7%) and 8 married (53.3%) participants, the UP group had 7 single (46.7%) and 8 married (53.3%) participants, and the control group had 9 single (60%) and 6 married (40%) participants. Regarding education, the ACT group included 10 participants with high school education (66.7%) and 5 with university education (33.3%), the UP group had 9 with high school education (60%) and 6 with university education (40%), and the control group had 10 with high school education (66.7%) and 5 with university education (33.3%).

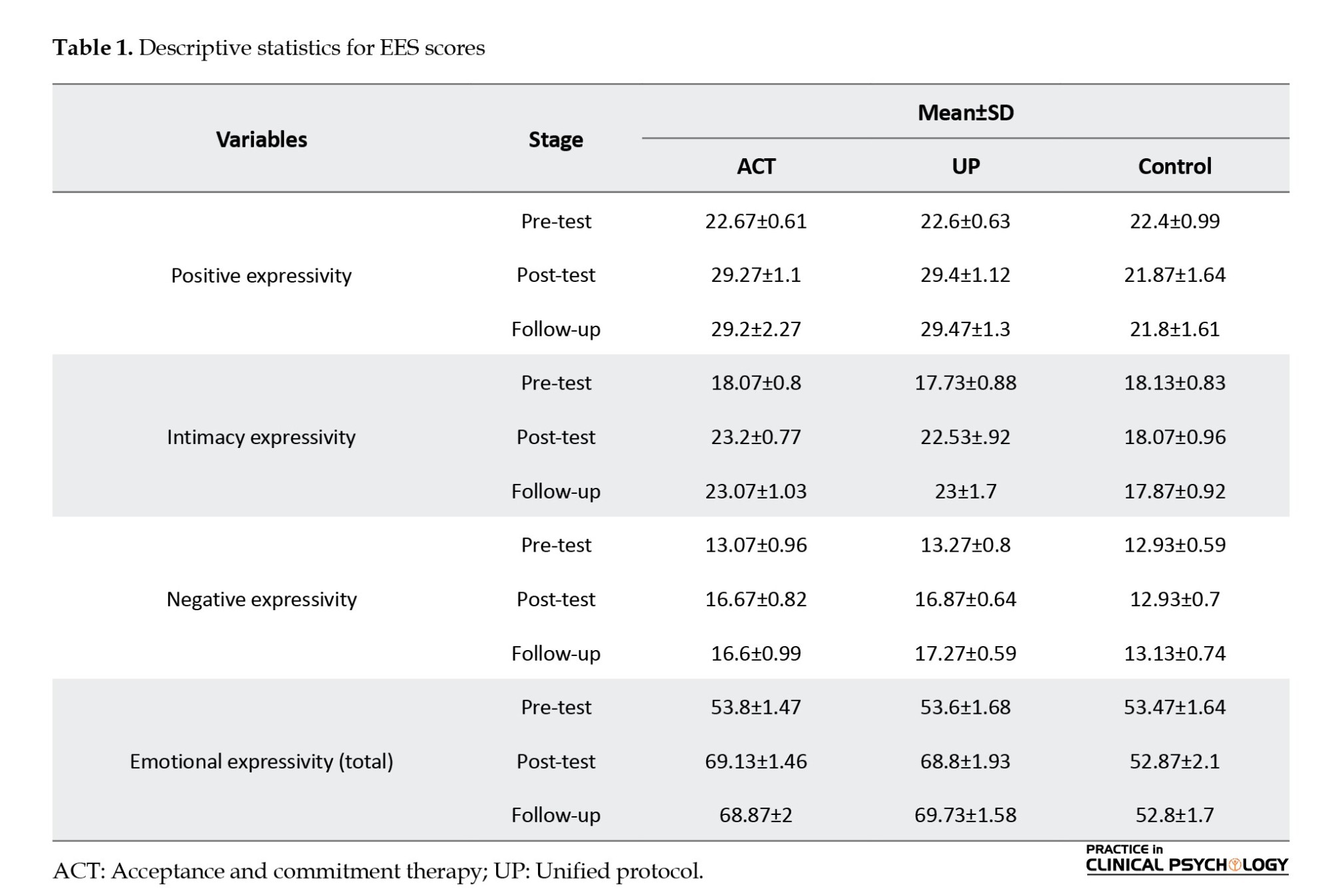

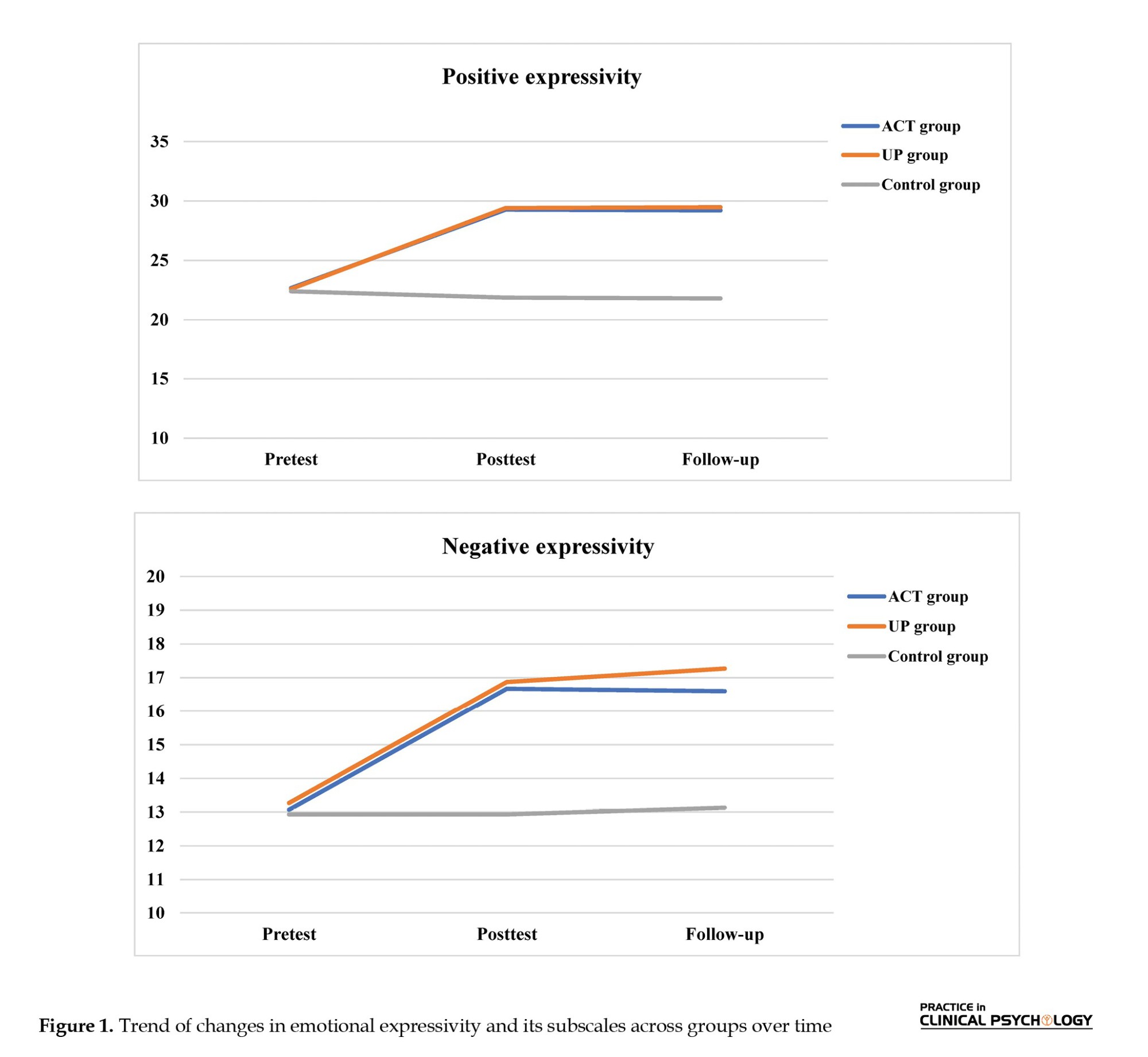

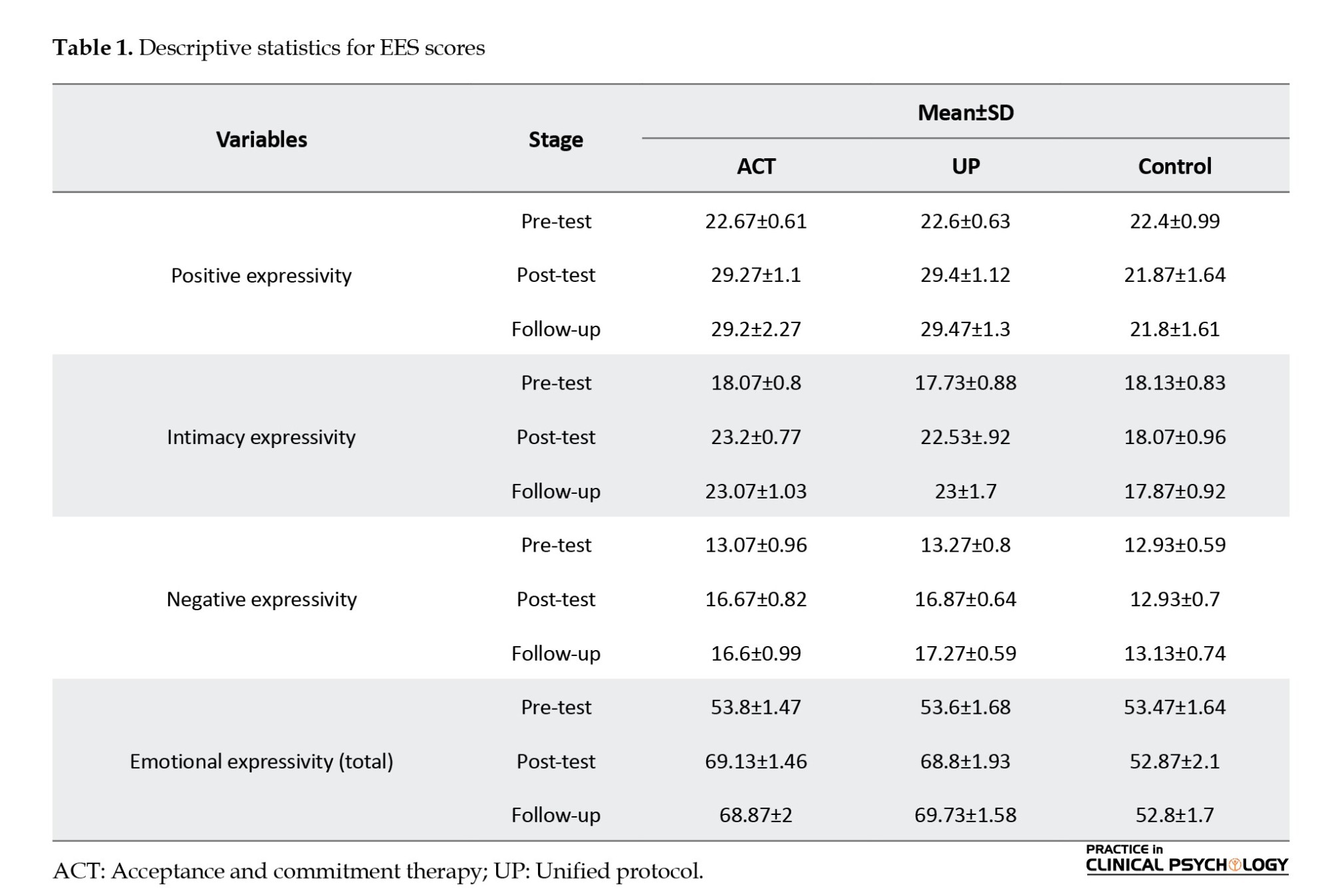

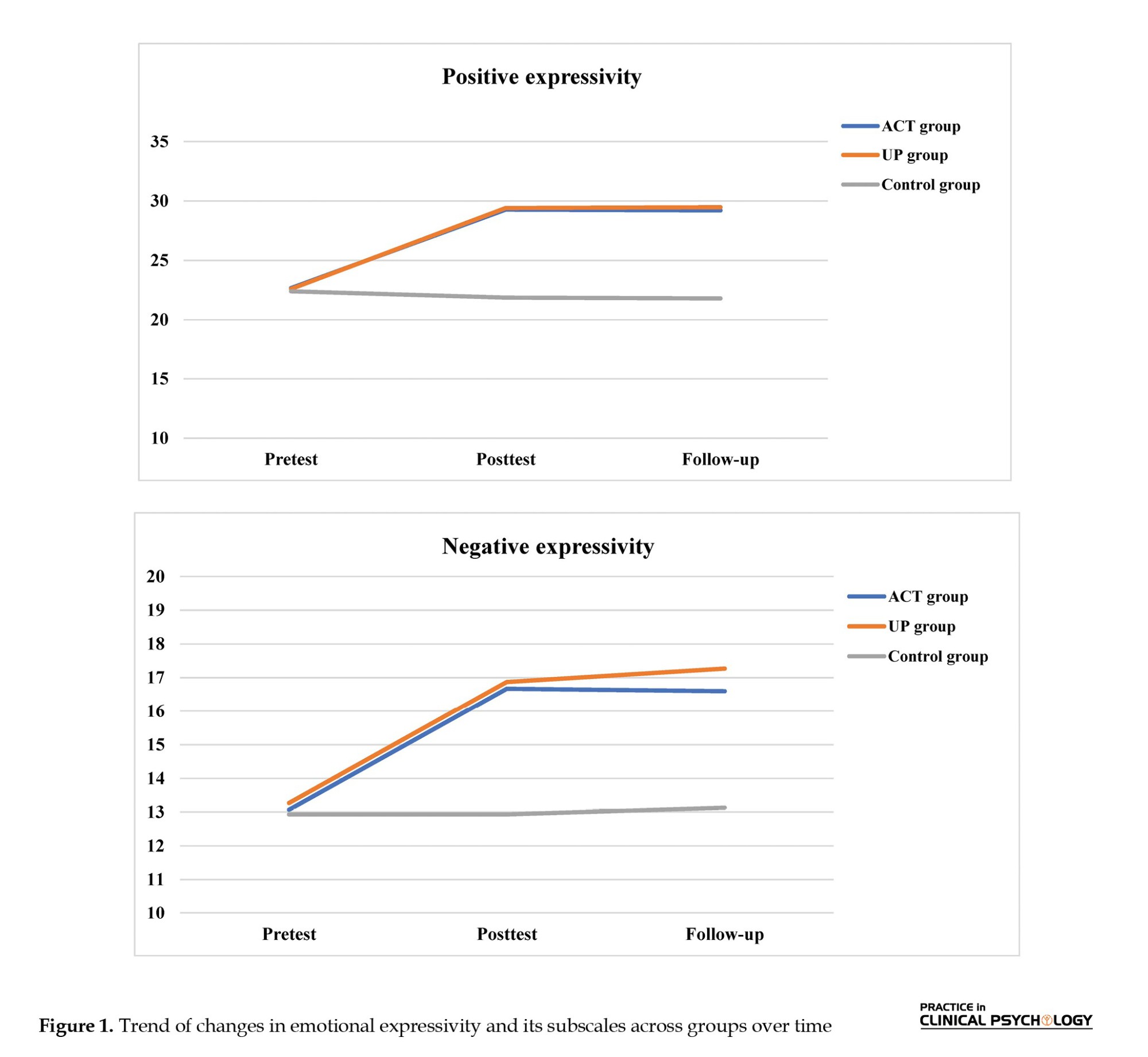

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of the EES scores and their subscales (positive, intimacy, and negative expressivity, and total emotional expressivity) across pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up for the ACT, UP, and control groups. At pre-test, all groups had comparable EES scores, indicating no baseline differences. Both ACT and UP groups showed substantial improvements in all EES subscales and total scores at post-test compared to the control group, which remained largely unchanged. These improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up, suggesting sustained therapeutic effects (Figure 1).

Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which indicated that EES scores and subscales were normally distributed across all groups and time points. The Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variances across groups, ensuring the appropriateness of parametric tests. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted for repeated measures ANOVA, and where the sphericity assumption was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied to ensure accurate interpretation of the results.

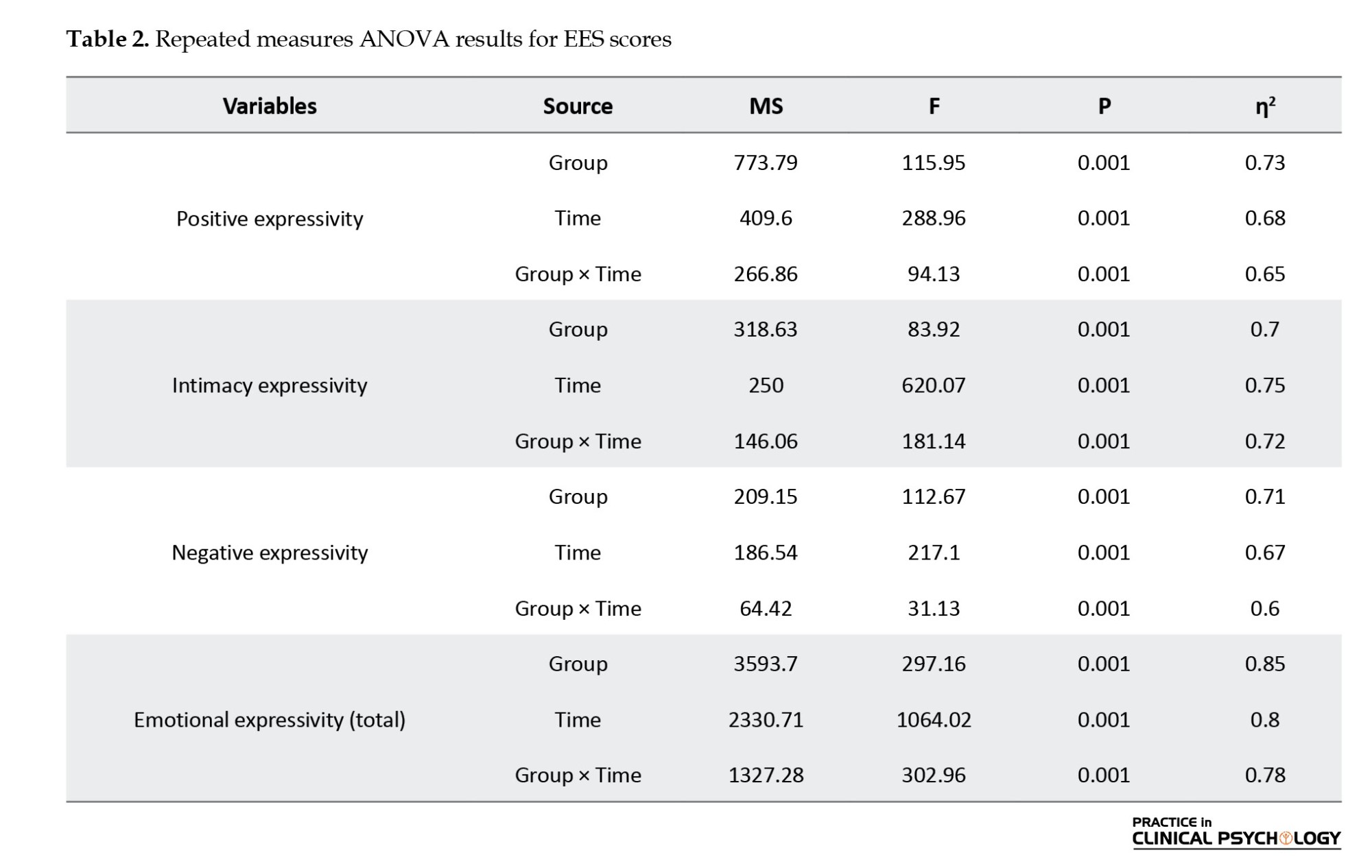

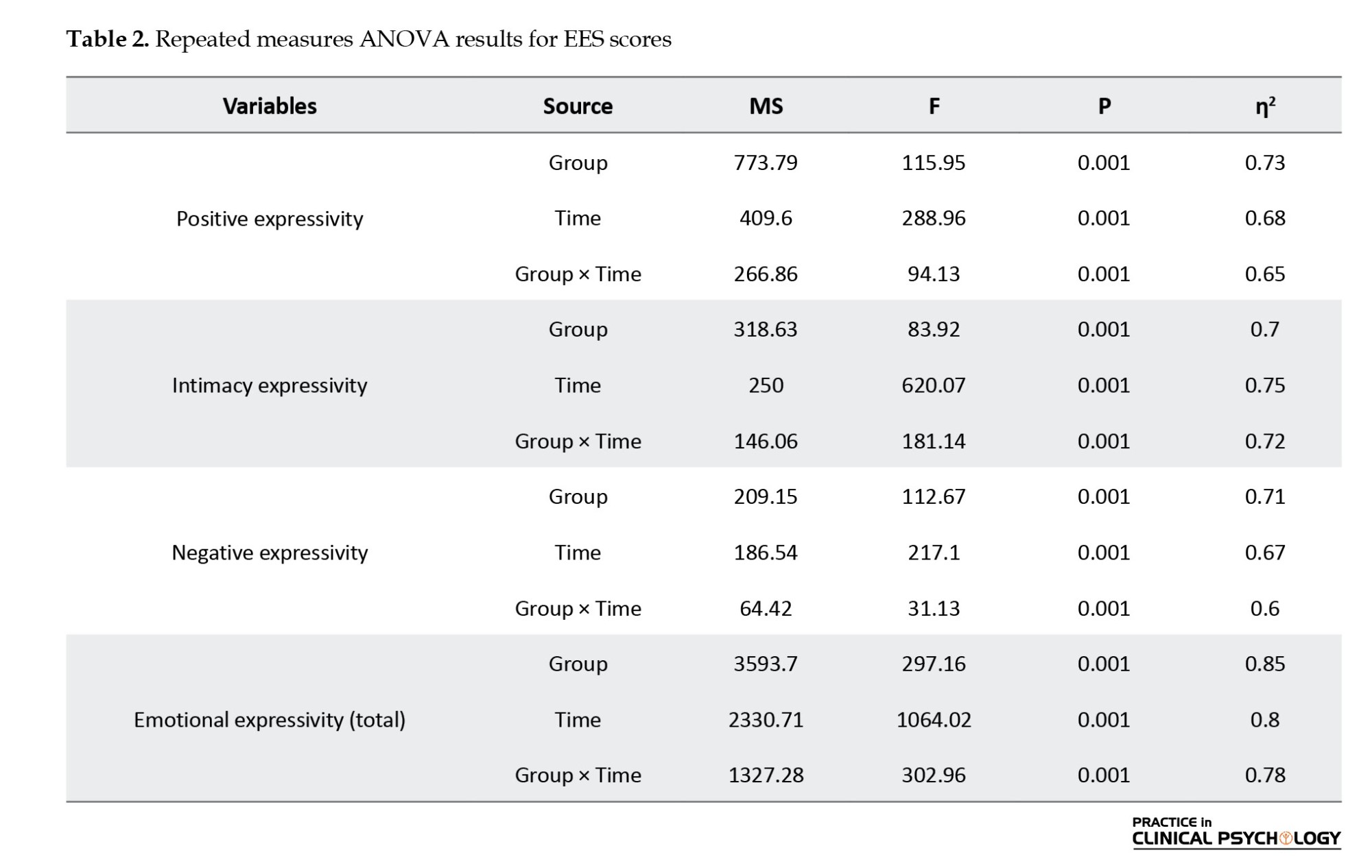

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group and time, as well as significant group × time interactions, for total emotional expressivity and all subscales. Specifically, for total emotional expressivity, significant effects were found for group (F=297.16, P<0.001, η²=0.85), time (F=1064.02, P<0.001, η²=0.8), and their interaction (F=302.96, P<0.001, η²=0.78). For positive expressivity, effects were significant for group (F=115.95, P<0.001, η²=0.73), time (F=288.96, P<0.001, η²=0.68), and interaction (F=94.13, P<0.001, η²=0.65). Intimacy expressivity showed significant effects for group (F=83.92, P<0.001, η²=0.70), time (F=620.07, P<0.001, η²=0.75), and interaction (F=181.14, P<0.001, η²=0.72). Negative expressivity had significant effects for group (F=112.67, P<0.001, η²=0.71), time (F=217.10, P<0.001, η²=0.67), and interaction (F=31.13, P<0.001, η²=0.60) (Table 2). These results indicate that both ACT and UP significantly enhanced emotional expressivity compared to the control group, with effects sustained over time.

Post-hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni test showed that both ACT and UP groups significantly outperformed the control group at post-test and follow-up across all EES subscales and total scores (P<0.001). Specifically, for positive expressivity, the ACT group showed a mean difference of 7.4 (SE=0.47) and the UP group a mean difference of 7.53 (SE=0.47) compared to the control group. For intimacy expressivity, both ACT and UP groups had a mean difference of 5.13 (SE=0.32) versus the control group. For negative expressivity, the ACT group showed a mean difference of 3.73 (SE=0.26) and the UP group 3.93 (SE=0.26) compared to the control group. For total emotional expressivity, the ACT group had a mean difference of 16.26 (SE=0.67) and the UP group 15.93 (SE=0.67) compared to the control group. No significant differences were found between ACT and UP for any subscale or total score, indicating comparable efficacy of the two interventions.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate and compare the effectiveness of ACT and the UP on emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The findings indicate that both interventions significantly enhanced emotional expressivity across all subscales (positive, intimacy, and negative) compared to the control group, with these improvements sustained at the 3-month follow-up. Importantly, no significant differences were observed between ACT and UP, suggesting both therapies are equally effective in improving emotional expression in this population. These results align with previous research demonstrating the efficacy of ACT and UP in addressing emotional dysregulation in anxiety disorders, though few studies have specifically focused on emotional expressivity. For instance, Khoramnia et al. (2020) found ACT effective in reducing SAD symptoms, while Alavi et al. (2020) reported similar benefits for UP in improving emotion regulation. Unlike these studies, which primarily targeted symptom reduction, our research uniquely examines emotional expressivity, a critical aspect of social functioning, thus extending the literature by highlighting the broader impact of these therapies.

The effectiveness of ACT in enhancing emotional expressivity aligns with its core principles. Social anxiety often leads to emotional avoidance and suppression, as individuals fear that their expressed emotions, whether positive or negative, will be judged negatively (Ebrahimi et al., 2024). ACT, through its emphasis on psychological flexibility, directly addresses this core pathology. Cognitive defusion skills teach individuals to observe their anxious thoughts without fusing with them, while acceptance allows them to make room for difficult emotions rather than fighting or suppressing them (Caletti et al., 2022). By fostering a non-judgmental stance toward internal experiences, ACT enables women with SAD to express emotions more authentically, which is essential for building meaningful social connections. This finding aligns with Mostafazadeh et al. (2024), who found that ACT improves psychological well-being in anxiety disorders; our study specifically demonstrates its impact on measurable emotional expression outcomes.

Similarly, the significant improvement in emotional expressivity following the UP intervention can be attributed to its focus on emotional regulation. The UP operates on the transdiagnostic assumption that emotional disorders share common underlying mechanisms, such as a tendency to avoid or suppress emotional experiences (Sakiris & Berle, 2019). UP teaches a structured set of skills designed to increase emotional awareness, provide tools for cognitive reappraisal, and encourage a direct, non-avoidant approach to emotion-driven actions (Nikdanesh et al., 2025). For women with SAD, these skills counteract the fear-driven suppression of emotions, enabling freer expression of both positive and negative emotions. This finding is consistent with Kargar et al. (2023), who found UP enhanced emotional expression in infertile women. However, our study extends these findings to SAD, highlighting UP’s applicability to anxiety-related emotional deficits.

The absence of significant differences between ACT and UP in enhancing emotional expressivity supports the process-based therapy framework, which emphasizes shared therapeutic mechanisms over specific treatment labels (Hayes & Hofmann, 2021). Both ACT and UP incorporate mindfulness, acceptance, and exposure-based strategies, which likely target the same underlying processes of emotional avoidance and dysregulation in SAD. This finding aligns with comparative studies showing equivalent outcomes across third-wave therapies when targeting transdiagnostic processes like emotion regulation (Hayes & Hofmann, 2021). Our study contributes to this literature by demonstrating that these shared processes are effective specifically for emotional expressivity, a key functional outcome in SAD.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant. Both ACT and UP offer robust tools for clinicians to address emotional expressivity deficits in women with SAD, improving their ability to engage in social interactions. These interventions can enhance social functioning by enabling patients to express emotions more openly, reducing the risk of social isolation. Clinicians can choose between ACT and UP based on patient preferences, therapist training, and clinical context. For example, patients valuing mindfulness and values-driven action may prefer ACT, while those needing structured emotion regulation skills may benefit more from UP. Therapists trained in either approach can confidently apply these interventions, knowing they yield comparable, sustained benefits.

This study has limitations that warrant consideration. The convenience sample of 45 women from Ahvaz, Iran, limits generalizability, particularly given the cultural context where gender norms may uniquely influence emotional expression (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). The small sample size per group, while sufficient for statistical power, may restrict the detection of subtle differences between interventions. The exclusive focus on women, while justified by their higher SAD prevalence and unique sociocultural challenges, limits applicability to men or mixed-gender groups. Future research should include larger, more diverse samples across different cultural contexts and genders to enhance generalizability. Additionally, exploring the specific mechanisms (e.g. mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal) driving changes in emotional expressivity could further refine these interventions.

Practical recommendations for clinicians include integrating ACT or UP into treatment plans for women with SAD, tailoring the choice to patient needs and therapist expertise. Training programs should emphasize both therapies’ shared processes, such as mindfulness and exposure, to equip clinicians with flexible tools. Group-based delivery, as used in this study, may enhance accessibility and foster peer support, further amplifying therapeutic benefits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides strong evidence that both ACT and the UP are highly effective interventions for enhancing emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The significant improvements observed in the ACT and UP groups compared to the control group, across all subscales of the EES, underscore the clinical utility of these modern, process-based therapies. Moreover, the sustained effects at the three-month follow-up suggest that the skills learned lead to lasting therapeutic benefits. The finding that the two interventions produced comparable results indicates that both approaches can serve as valuable tools for clinicians working with this population, offering flexibility in treatment choice based on therapist expertise and patient preference.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.410). This study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20250310065014N1) All participants provided written informed consent before the study began.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results, and manuscript drafting. Each author approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a prevalent mental health condition marked by an intense, persistent fear of social or performance situations, often leading to significant distress and impaired social functioning (Alomari et al., 2022). Individuals with SAD experience profound concerns about negative evaluation, judgment, or humiliation, which can result in avoidance of social interactions, diminished quality of life, and disruptions in career, education, and relationships (Penninx et al., 2021). Unlike typical shyness, SAD involves disproportionate anxiety that interferes with daily life, driven by cognitive processes such as hypervigilance for social threats, negative self-appraisals, and misinterpretation of ambiguous social cues as hostile (Sadrzadeh et al., 2024). Women are disproportionately affected by SAD, facing unique sociocultural pressures, particularly in contexts like Iran, where gender norms may exacerbate emotional suppression and social avoidance (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). This gender-specific burden highlights the need for targeted interventions to address emotional expression deficits in women with SAD, a population often underrepresented in comparative treatment research. Effective interventions are essential to help these individuals navigate social environments with greater confidence and authenticity.

Emotional expressivity, the outward display of internal emotional states through verbal and non-verbal cues like facial expressions and tone of voice, is a cornerstone of social communication but is frequently impaired in SAD (Naziri & Hooman, 2025). Fear of negative evaluation often leads individuals to suppress emotions, resulting in a restricted range of expression that others may misinterpret as aloofness, further isolating them (Xie & Wang, 2024). The emotional expressivity scale (EES) assesses this construct through subscales: Positive expressivity (e.g. joy, affection), negative expressivity (e.g. anger, sadness), and impulsivity, which measures uncontrolled emotional expression (Moghadam et al., 2025). Individuals with SAD often inhibit positive emotions, fearing they appear insincere, and suppress negative emotions to avoid seeming weak, leading to internal distress (Xu et al., 2025). Impulsivity is also restricted due to an intense need for control in social settings (Sağlam Topal & Yavuz Sever, 2024). This interplay between SAD and emotional expressivity underscores a critical gap in the literature: The lack of studies comparing therapeutic interventions that specifically target emotional expression deficits in women with SAD.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapy, promotes psychological flexibility by encouraging acceptance of internal experiences without judgment and commitment to value-driven actions (Mostafazadeh et al., 2024; Soltani et al., 2023). By reducing emotional avoidance, ACT may foster authentic emotional expression, crucial for social interactions (Caletti et al., 2022). Its efficacy in treating anxiety-related conditions suggests potential for addressing SAD’s emotional dysregulation (Khoramnia et al., 2020). Similarly, the unified protocol (UP) for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders targets shared emotional processes across disorders like anxiety and depression, using components like emotion psychoeducation, cognitive reappraisal, and emotion-driven action skills to enhance emotional competence (Barlow et al., 2017; Sakiris & Berle, 2019). UP’s focus on emotional regulation makes it particularly relevant for SAD, with evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing anxiety symptoms (Ghaderi et al., 2023; Rapee et al., 2023).

Despite the established efficacy of ACT and UP in reducing anxiety symptoms, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding their comparative effects on emotional expressivity in women with SAD. While both therapies address emotional dysregulation, no study has directly compared their impact on the EES subscales (positive, negative, and intimacy expressivity) in this population. This study addresses this gap through a novel, head-to-head comparison of ACT and UP, focusing on their ability to enhance emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The exclusive focus on women accounts for their higher SAD prevalence and the unique sociocultural factors, such as Iranian gender norms, that influence emotional expression (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). By examining whether these interventions yield sustained improvements in emotional expressivity, this research aims to inform clinical practice, offering evidence for tailored treatment strategies that enhance social functioning in this underserved population.

Materials and Methods

Participants and design

This study utilized a clinical trial with a pre-test-post-test with a 3-month follow-up design and one control group. The statistical population comprised all women diagnosed with SAD who sought treatment at counseling and psychology clinics in Ahvaz, Iran, in 2024. A convenience sample of 45 participants was selected, with the sample size determined using G*Power software to achieve 80% power for detecting a medium effect size (0.25) in repeated measures ANOVA, assuming α=0.05 and a correlation of 0.5 among repeated measures. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Being a woman between the ages of 20 and 40, having a diagnosis of SAD based on the structured clinical interview for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) (SCID-5), conducted by trained clinical psychologists, and a score above the clinical cutoff on the social phobia inventory (SPIN). The exclusion criteria included having a comorbid severe mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), receiving concurrent psychological treatment, a history of substance abuse, or missing more than two treatment sessions. The selected participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: The ACT group, the UP group, and a waiting-list control group, with 15 participants in each group.

Study procedure

Before the intervention, all participants completed the EES. The experimental groups then participated in eight weekly 90-minute group therapy sessions. The ACT group received therapy based on the ACT manual, while the UP group received therapy based on the UP for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders manual. Detailed session content for both interventions is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The control group did not receive any intervention during this period and was placed on a waiting list. At the conclusion of the therapy sessions (post-test), all participants again completed the EES. A final assessment was conducted three months after the post-test (follow-up) for all groups to evaluate the long-term effects of the interventions.

Research tools

EES

EES is a 16-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure an individual’s outward expression of emotion. It assesses three subscales: Positive expressivity (7 items), intimacy expressivity (5 items), and negative expressivity (4 items). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (not at all true of me) to 7 (very true of me). Higher scores indicate greater emotional expressivity. The items related to the negative expressivity subscale are scored in reverse (King & Emmons, 1990). In Persian studies, the EES has demonstrated good reliability and validity, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.75 to 0.89 (Kargar et al., 2023). In the present study, the Cronbach α for the total EES was 0.87, with subscale alphas of 0.82 for positive expressivity, 0.8 for intimacy expressivity, and 0.79 for negative expressivity, indicating high internal consistency across all subscales.

Intervention program

The ACT intervention consisted of 8 weekly group sessions, each lasting 90 minutes. The sessions were based on the ACT hexaflex model, focusing on key psychological flexibility processes (McHugh, 2011). The UP intervention also comprised eight weekly group sessions, each lasting 90 minutes. The sessions focused on five core emotional competencies, as outlined in the UP manual (Barlow et al., 2017). A summary of the ACT and UP intervention sessions is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sample characteristics. To test the hypotheses, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine the effectiveness of the interventions and their long-term effects on the EES scores. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

The study included 45 women diagnosed with SAD, randomly assigned to three groups: ACT, UP, and one control group, each comprising 15 participants. The mean age was 31.60±6.35 years for the ACT group, 32.02±5.91 years for the UP group, and 31.79±5.34 years for the control group, indicating comparable age distributions. Marital status across groups showed the ACT group had 7 single (46.7%) and 8 married (53.3%) participants, the UP group had 7 single (46.7%) and 8 married (53.3%) participants, and the control group had 9 single (60%) and 6 married (40%) participants. Regarding education, the ACT group included 10 participants with high school education (66.7%) and 5 with university education (33.3%), the UP group had 9 with high school education (60%) and 6 with university education (40%), and the control group had 10 with high school education (66.7%) and 5 with university education (33.3%).

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of the EES scores and their subscales (positive, intimacy, and negative expressivity, and total emotional expressivity) across pre-test, post-test, and 3-month follow-up for the ACT, UP, and control groups. At pre-test, all groups had comparable EES scores, indicating no baseline differences. Both ACT and UP groups showed substantial improvements in all EES subscales and total scores at post-test compared to the control group, which remained largely unchanged. These improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up, suggesting sustained therapeutic effects (Figure 1).

Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which indicated that EES scores and subscales were normally distributed across all groups and time points. The Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variances across groups, ensuring the appropriateness of parametric tests. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted for repeated measures ANOVA, and where the sphericity assumption was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied to ensure accurate interpretation of the results.

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group and time, as well as significant group × time interactions, for total emotional expressivity and all subscales. Specifically, for total emotional expressivity, significant effects were found for group (F=297.16, P<0.001, η²=0.85), time (F=1064.02, P<0.001, η²=0.8), and their interaction (F=302.96, P<0.001, η²=0.78). For positive expressivity, effects were significant for group (F=115.95, P<0.001, η²=0.73), time (F=288.96, P<0.001, η²=0.68), and interaction (F=94.13, P<0.001, η²=0.65). Intimacy expressivity showed significant effects for group (F=83.92, P<0.001, η²=0.70), time (F=620.07, P<0.001, η²=0.75), and interaction (F=181.14, P<0.001, η²=0.72). Negative expressivity had significant effects for group (F=112.67, P<0.001, η²=0.71), time (F=217.10, P<0.001, η²=0.67), and interaction (F=31.13, P<0.001, η²=0.60) (Table 2). These results indicate that both ACT and UP significantly enhanced emotional expressivity compared to the control group, with effects sustained over time.

Post-hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni test showed that both ACT and UP groups significantly outperformed the control group at post-test and follow-up across all EES subscales and total scores (P<0.001). Specifically, for positive expressivity, the ACT group showed a mean difference of 7.4 (SE=0.47) and the UP group a mean difference of 7.53 (SE=0.47) compared to the control group. For intimacy expressivity, both ACT and UP groups had a mean difference of 5.13 (SE=0.32) versus the control group. For negative expressivity, the ACT group showed a mean difference of 3.73 (SE=0.26) and the UP group 3.93 (SE=0.26) compared to the control group. For total emotional expressivity, the ACT group had a mean difference of 16.26 (SE=0.67) and the UP group 15.93 (SE=0.67) compared to the control group. No significant differences were found between ACT and UP for any subscale or total score, indicating comparable efficacy of the two interventions.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate and compare the effectiveness of ACT and the UP on emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The findings indicate that both interventions significantly enhanced emotional expressivity across all subscales (positive, intimacy, and negative) compared to the control group, with these improvements sustained at the 3-month follow-up. Importantly, no significant differences were observed between ACT and UP, suggesting both therapies are equally effective in improving emotional expression in this population. These results align with previous research demonstrating the efficacy of ACT and UP in addressing emotional dysregulation in anxiety disorders, though few studies have specifically focused on emotional expressivity. For instance, Khoramnia et al. (2020) found ACT effective in reducing SAD symptoms, while Alavi et al. (2020) reported similar benefits for UP in improving emotion regulation. Unlike these studies, which primarily targeted symptom reduction, our research uniquely examines emotional expressivity, a critical aspect of social functioning, thus extending the literature by highlighting the broader impact of these therapies.

The effectiveness of ACT in enhancing emotional expressivity aligns with its core principles. Social anxiety often leads to emotional avoidance and suppression, as individuals fear that their expressed emotions, whether positive or negative, will be judged negatively (Ebrahimi et al., 2024). ACT, through its emphasis on psychological flexibility, directly addresses this core pathology. Cognitive defusion skills teach individuals to observe their anxious thoughts without fusing with them, while acceptance allows them to make room for difficult emotions rather than fighting or suppressing them (Caletti et al., 2022). By fostering a non-judgmental stance toward internal experiences, ACT enables women with SAD to express emotions more authentically, which is essential for building meaningful social connections. This finding aligns with Mostafazadeh et al. (2024), who found that ACT improves psychological well-being in anxiety disorders; our study specifically demonstrates its impact on measurable emotional expression outcomes.

Similarly, the significant improvement in emotional expressivity following the UP intervention can be attributed to its focus on emotional regulation. The UP operates on the transdiagnostic assumption that emotional disorders share common underlying mechanisms, such as a tendency to avoid or suppress emotional experiences (Sakiris & Berle, 2019). UP teaches a structured set of skills designed to increase emotional awareness, provide tools for cognitive reappraisal, and encourage a direct, non-avoidant approach to emotion-driven actions (Nikdanesh et al., 2025). For women with SAD, these skills counteract the fear-driven suppression of emotions, enabling freer expression of both positive and negative emotions. This finding is consistent with Kargar et al. (2023), who found UP enhanced emotional expression in infertile women. However, our study extends these findings to SAD, highlighting UP’s applicability to anxiety-related emotional deficits.

The absence of significant differences between ACT and UP in enhancing emotional expressivity supports the process-based therapy framework, which emphasizes shared therapeutic mechanisms over specific treatment labels (Hayes & Hofmann, 2021). Both ACT and UP incorporate mindfulness, acceptance, and exposure-based strategies, which likely target the same underlying processes of emotional avoidance and dysregulation in SAD. This finding aligns with comparative studies showing equivalent outcomes across third-wave therapies when targeting transdiagnostic processes like emotion regulation (Hayes & Hofmann, 2021). Our study contributes to this literature by demonstrating that these shared processes are effective specifically for emotional expressivity, a key functional outcome in SAD.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant. Both ACT and UP offer robust tools for clinicians to address emotional expressivity deficits in women with SAD, improving their ability to engage in social interactions. These interventions can enhance social functioning by enabling patients to express emotions more openly, reducing the risk of social isolation. Clinicians can choose between ACT and UP based on patient preferences, therapist training, and clinical context. For example, patients valuing mindfulness and values-driven action may prefer ACT, while those needing structured emotion regulation skills may benefit more from UP. Therapists trained in either approach can confidently apply these interventions, knowing they yield comparable, sustained benefits.

This study has limitations that warrant consideration. The convenience sample of 45 women from Ahvaz, Iran, limits generalizability, particularly given the cultural context where gender norms may uniquely influence emotional expression (Sepahvand & Karami, 2020). The small sample size per group, while sufficient for statistical power, may restrict the detection of subtle differences between interventions. The exclusive focus on women, while justified by their higher SAD prevalence and unique sociocultural challenges, limits applicability to men or mixed-gender groups. Future research should include larger, more diverse samples across different cultural contexts and genders to enhance generalizability. Additionally, exploring the specific mechanisms (e.g. mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal) driving changes in emotional expressivity could further refine these interventions.

Practical recommendations for clinicians include integrating ACT or UP into treatment plans for women with SAD, tailoring the choice to patient needs and therapist expertise. Training programs should emphasize both therapies’ shared processes, such as mindfulness and exposure, to equip clinicians with flexible tools. Group-based delivery, as used in this study, may enhance accessibility and foster peer support, further amplifying therapeutic benefits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides strong evidence that both ACT and the UP are highly effective interventions for enhancing emotional expressivity in women with SAD. The significant improvements observed in the ACT and UP groups compared to the control group, across all subscales of the EES, underscore the clinical utility of these modern, process-based therapies. Moreover, the sustained effects at the three-month follow-up suggest that the skills learned lead to lasting therapeutic benefits. The finding that the two interventions produced comparable results indicates that both approaches can serve as valuable tools for clinicians working with this population, offering flexibility in treatment choice based on therapist expertise and patient preference.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.410). This study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20250310065014N1) All participants provided written informed consent before the study began.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results, and manuscript drafting. Each author approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Alavi, S. M., Rafieinia, P., Makvand Hosseini, S., & Sabahi, P. (2020). The effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic treatment on social anxiety symptoms and difficulty in emotion regulation: Single-subject design. Journal of Psychological Studies, 16(2), 7-24. [DOI:10.22051/psy.2020.23008.1774]

Alomari, N. A., Bedaiwi, S. K., Ghasib, A. M., Kabbarah, A. J., Alnefaie, S. A., & Hariri, N., et al. (2022). Social anxiety disorder: Associated conditions and therapeutic approaches. Cureus, 14(12), e32687. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.32687]

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Bullis, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., Murray-Latin, H., & Sauer-Zavala, S., et al. (2017). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875-884. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164] [PMID]

Caletti, E., Massimo, C., Magliocca, S., Moltrasio, C., Brambilla, P., & Delvecchio, G. (2022). The role of the acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of social anxiety: An updated scoping review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 310, 174-182. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.008] [PMID]

Ebrahimi, S., Moheb, N., & Alivani Vafa, M. (2024). Comparison of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy on cognitive distortions and rumination in adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 81-94. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.1.922.1]

Ghaderi, F., Akrami, N., Namdari, K., & Abedi, A. (2023). Investigating the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on maladaptive personality traits and mentalized affectivity of patients with generalized anxiety disorder comorbid with depression: A case study. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 11(2), 117. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.2.862.1]

Ghiyasi Noei, A., Sabahi, P., & Rafieinia, P. (2021). Effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic therapy on cognitive emotion regulation, experimental avoidance and post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health, 13(3), 221. [Link]

Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2021). “Third-wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies and the emergence of a process-based approach to intervention in psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 20(3), 363-375. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20884] [PMID]

Kargar, K., Vaziri, S., Lotfi Kashani, F., Nasri, M., & Shahabizadeh, F. (2023). [Efficacy of unified trans-diagnostic treatment on the emotional expression and sexual function in infertile women (Persian)]. Health Psychology, 12(46), 23-40. [DOI:10.30473/hpj.2023.64543.5580]

Khoramnia, S., Bavafa, A., Jaberghaderi, N., Parvizifard, A., Foroughi, A., & Ahmadi, M., et al. (2020). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42(1), 30-38. [DOI:10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0003] [PMID]

King, L. A., & Emmons, R. A. (1990). Conflict over emotional expression: Psychological and physical correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 864-877. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.864] [PMID]

McHugh, L. (2011). A new approach in psychotherapy: ACT (acceptance and commitment therapy). The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 12(Suppl. 1), 76-79. [DOI:10.3109/15622975.2011.603225] [PMID]

Moghadam, F. D., Rahami, Z., Ahmadi, S. A., Reisi, S., & Ahmadi, S. M. (2025). Predicting quality of life and self-care behaviors in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy based on psychological factors. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 6431. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-91254-y] [PMID]

Mostafazadeh, P., Sotoudehasl, N., & Ghorbani, R. (2024). Comparing the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and metacognitive therapy on psychological well-being in women with generalized anxiety disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 12(2), 153. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.2.929.1]

Naziri, A., & Hooman, F. (2025). The role of family functioning and emotional expressiveness in predicting anxiety in adolescent girls. Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 15(1), 33. [DOI:10.61882/pcnm.15.1.33]

Nikdanesh, M., Ashuri, A., Gharraee, B., & Farahani, H. (2025). Investigating the pattern of transdiagnostic related to emotion regulation of adolescents with high-risk behavior and effectiveness of integrated transdiagnostic protocol on reduction of their anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 14, 83. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_203_24] [PMID]

Penninx, B. W., Pine, D. S., Holmes, E. A., & Reif, A. (2021). Anxiety disorders. The Lancet, 397(10277), 914-927. [DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00359-7] [PMID]

Rapee, R. M., McLellan, L. F., Carl, T., Trompeter, N., Hudson, J. L., & Jones, M. P., et al. (2023). Comparison of transdiagnostic treatment and specialized social anxiety treatment for children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(6), 646-655. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2022.08.003] [PMID]

Sadrzadeh, F., Borjali, A., & Rafezi, Z. (2024). Self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms: Fear of negative evaluation and shame as mediators. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 12(4), 371. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.4.967.1]

Sağlam Topal, B., & Yavuz Sever, A. E. (2024). I love you but I can’t say: Adaptation of the Measure of Verbally Expressed Emotion (MoVEE) to Turkish and investigation of psychometric properties. Current Psychology, 43(24), 20881-20890. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-024-05861-5]

Sakiris, N., & Berle, D. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the unified protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101751. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101751] [PMID]

Sepahvand, T., & Karami, K. (2020). Explaining anger in atypical social anxiety disorder based on impulsivity and risk perception. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 8(4), 297. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.8.4.693.1]

Soltani, E., Bahrainian, S. A., Farhoudian, A., Masjedi Arani, A., & Gachkar, L. (2023). Effectiveness of acceptance commitment therapy in social anxiety disorder: Application of a longitudinal method to evaluate the mediating role of acceptance, cognitive fusion, and values. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 14(4), 479-490. [DOI:10.32598/bcn.2021.2785.1] [PMID]

Xie, Z., & Wang, Z. (2024). Longitudinal examination of the relationship between virtual companionship and social anxiety: Emotional expression as a mediator and mindfulness as a moderator. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 765-782. [DOI:10.2147/prbm.S447487] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/08/6 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2026/12/28

Received: 2025/08/6 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2026/12/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |