Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 11-20 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rahmati Shahreza S, Rezapour-Mirsaleh Y, Choobfroushzadeh A. Family Support and Post-gender Reassignment in Transgender Individuals: A Phenomenological Study. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :11-20

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1048-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1048-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran. ,y.rezapour@ardakan.ac.ir

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 547 kb]

(297 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (724 Views)

Appendix A: Sample interview questions

1. Family support experiences

Can you describe how your family reacted when you first disclosed your transsexual identity?

What specific actions or behaviors from your family felt most supportive during or after your gender reassignment process?

Were there moments when you felt your family’s support was lacking? How did this affect you?

2. Psychological and emotional impact

How did your family’s support (or lack thereof) influence your mental health before and after surgery?

Can you share an example of how family support helped you cope with challenges related to your transition?

3. Social and functional outcomes

How did your family’s attitude affect your ability to engage socially (e.g. friendships, work, education) post-surgery?

Did your family advocate for you in social settings (e.g. correcting pronouns, defending your identity)? If so, how did this impact you?

4. Family dynamics

How have your relationships with family members changed since your surgery?

What do you wish your family had understood earlier about your experience as a transsexual individual?

5. Post-surgery reflections

Looking back, what role do you feel family support played in your overall satisfaction with your gender reassignment journey?

If you could advise other families of transsexual individuals, what would you emphasize about providing support?

Full-Text: (175 Views)

Introduction

Human sexual differentiation begins at conception, with the 23rd pair of chromosomes (XX or XY) determining biological sex (Rice, 2001; Garrett, 2003). However, gender—the psychological and social construct encompassing roles, behaviors, and identities—develops over time, influenced by familial, cultural, and environmental factors (Vasegh Rahimpour et al., 2013). While most individuals experience congruence between their biological sex and gender identity, others face profound dissonance, historically termed gender identity disorder (Halgin & Whitbourne, 2014; Yazdanpanah & Samadian, 2011). Transsexual individuals, classified as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM), often experience this dissonance as a visceral misalignment between their physical bodies and internal selves, leading many to pursue gender reassignment interventions (Nagoshi & Brzuzy, 2010; Abbassian, 2019).

The familial and social challenges of transsexuality

Disclosing a transsexual identity can disrupt family systems, provoking stress, confusion, or rejection (Sieverts, 2018). Societal and familial pressures to conform to birth-assigned gender roles frequently exacerbate psychological distress, contributing to social isolation, academic disengagement, and heightened vulnerability among trans individuals (Zucker & Bradiey, 2005). Conversely, familial acceptance is a critical protective factor, buffering against mental health risks and fostering resilience (McCormick & Baldridge, 2019). Supportive families not only mitigate internalized stigma but also facilitate broader social integration, reducing barriers to well-being (Mirzaei, 2019).

Research gap and study aims

Despite growing recognition of transsexual identities, the transformative role of family support—particularly in the context of gender reassignment surgery—remains understudied, especially in non-Western settings like Iran. Prior research highlights familial acceptance as a predictor of life satisfaction (Rule, 2018), yet few studies explore its lived consequences post-surgery. This study addresses this gap by investigating the relevant factors. By employing a phenomenological approach, we center the voices of transsexual individuals to elucidate the mechanisms through which familial acceptance influences psychological health, social participation, and family dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study employed a descriptive phenomenological approach to explore the lived experiences of transsexual individuals following gender reassignment surgery, with a focus on the role of family support. Phenomenology is uniquely suited to uncover the “essence” of participants’ shared experiences through in-depth engagement with their narratives (Creswell, 2007).

Participants and sampling

The study population included 12 transsexual individuals (5 FTM, 7 MTF) residing in Isfahan City, Iran, all of whom had undergone gender reassignment surgery and reported receiving familial support. Support was operationally defined as verbal affirmation, financial or logistical assistance during transition, or advocacy within social networks, as confirmed through dual interviews with participants and their family members.

Participants were selected via snowball sampling, a non-probability method effective for recruiting marginalized populations (Jalali, 2012). Sampling continued until theoretical saturation was achieved (i.e. no new themes emerged in three consecutive interviews) (Saunders et al., 2018). The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of gender identity disorder by a licensed clinical psychologist (consistent with diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition [DSM-5] criteria at the time of data collection), completion of gender reassignment surgery ≥6 months before the study, and self-reported family support post-surgery. The exclusion criteria were active family conflict (e.g. estrangement, ongoing rejection), comorbid psychological (e.g. untreated psychosis) or physical conditions impairing participation.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews (average duration: 60–90 minutes) were conducted in Persian by Sarina Rahmati Shahreza, using an interview guide developed through expert consultation (see Appendix A for sample questions). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English for analysis. To enhance trustworthiness, member checking was employed: Participants reviewed transcripts and preliminary themes for accuracy (Birt et al., 2016).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s (1978) 7-step phenomenological method.

Transcription: Repeated listening and verbatim transcription.

Significant statements: Extraction of phrases directly related to family support.

Formulated meanings: Interpretation of statements’ underlying meanings.

Theme development: Clustering meanings into thematic groups.

Exhaustive description: Integration of themes into a unified narrative.

Essential structure: Synthesis of the phenomenon’s core structure.

Validation: Participant feedback on findings to ensure accuracy (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

To minimize bias, two independent coders analyzed a subset of interviews, achieving 85% inter-coder agreement (Krippendorff’s α=0.82). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Results

This phenomenological study examined the lived experiences of 12 transsexual individuals (5 FTM, 7 MTF) in Isfahan, Iran, who underwent gender reassignment surgery and received family support. Through in-depth analysis, four central themes emerged, each comprising multiple interrelated categories that collectively illustrate the transformative impact of familial acceptance. Participant quotes are anonymized as P1-P12.

Theme 1: Hope for life

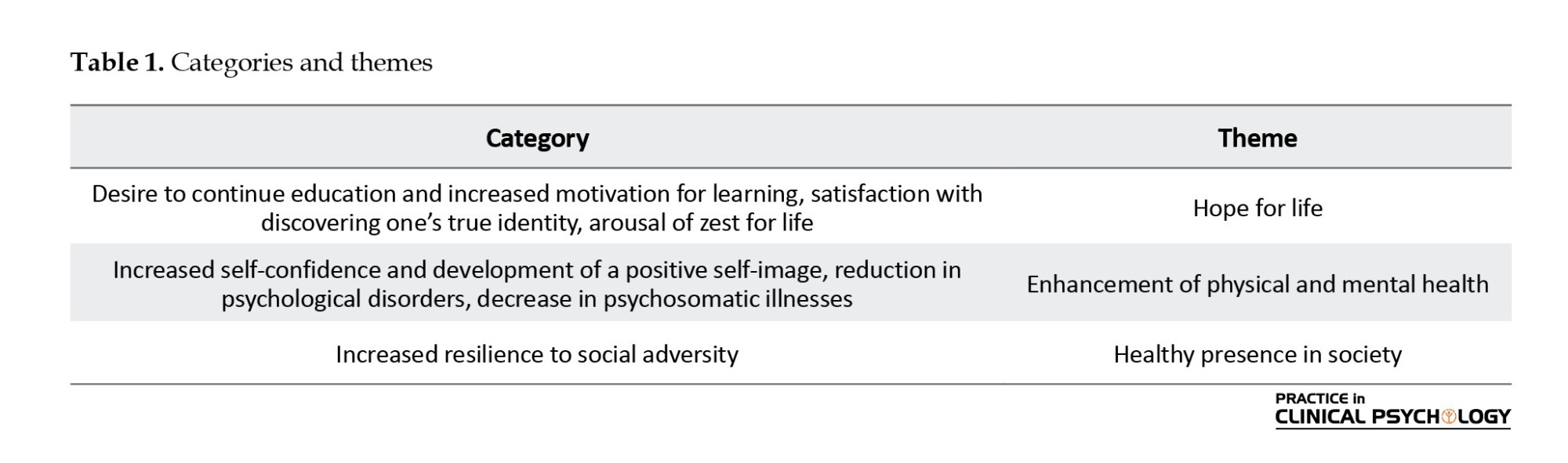

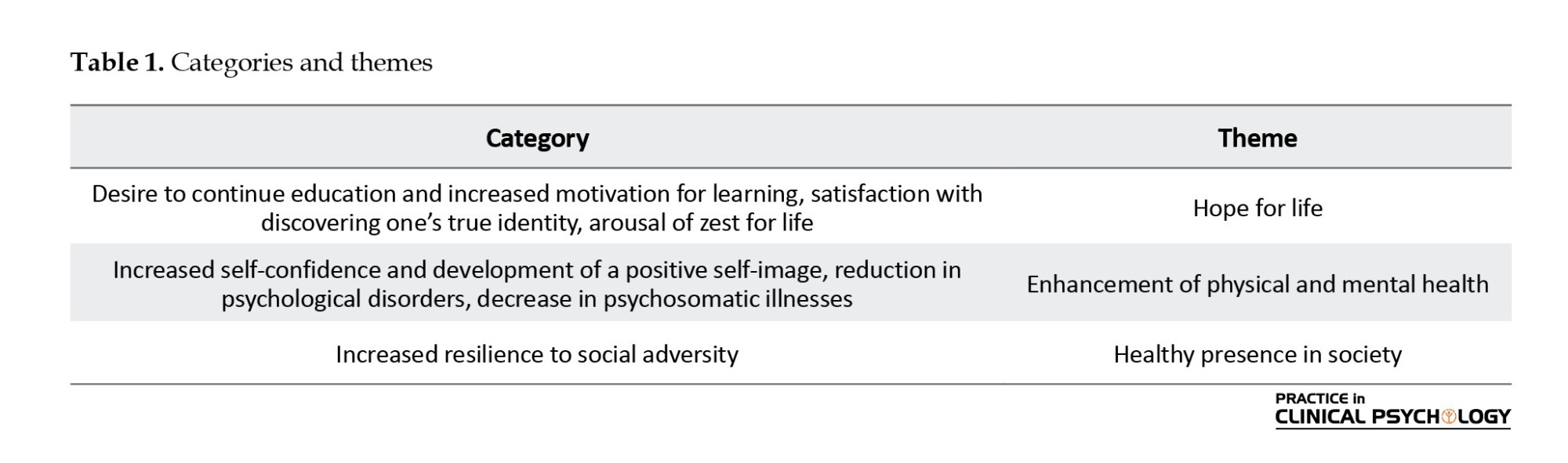

This theme captures participants’ reinvigorated sense of purpose and future orientation following gender affirmation and family support. Three key dimensions emerged (Table 1):

Desire to continue education and increased motivation for learning

Four participants who had previously abandoned education due to gender-related distress reported renewed academic engagement post-transition. Their narratives revealed how family support created psychological safety for learning:

“After my gender reassignment surgery, everything in my life fell into place. I was able to continue my studies, get my degree, and find a job” (Participants No. 4 [P4], FTM).

This aligns with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs - once basic identity acceptance was achieved, self-actualization through education became possible.

Satisfaction with discovering one’s true identity

All participants emphasized this as the most profound outcome, describing it as “finally being whole.” Even those with initial family resistance reported this satisfaction:

“I went through a very difficult journey to become who I am now. I’m happy to have left that body behind and embraced my true identity---as a boy” (P7, FTM).

This echoes Erikson’s theory of identity cohesion as fundamental to psychological well-being.

Arousal of zest for life

Five participants described a dramatic shift from survival mode to active life participation:

“Being satisfied with life is so important. I know I can have a good life. I’ve got the strength, and I strive with all my being to live my days in the best way possible” (P12, MTF).

This transformation suggests family support facilitates the transition from mere coping to thriving.

Theme 2: Enhancement of physical and mental health

Participants reported comprehensive health improvements reflecting the mind-body connection:

Increased self-confidence and positive self-image

Six participants described moving from self-loathing to self-acceptance:

“I feel great about myself. I value who I am and love myself deeply. I’m proud of myself” (P3, MTF).

This feeling mirrors body positivity research, which shows that congruence between physical form and identity boosts self-worth.

Reduction in psychological disorders

Five participants reported clinically significant decreases in anxiety and depression symptoms:

“I deal with a lot of anxiety and stress. Before the surgery, I was very anxious and depressed. I felt awful, but now, thank God, I feel better” (P9, FTM).

This supports minority stress model predictions about reduced internalized stigma.

Decrease in psychosomatic illnesses

Three participants resolved chronic conditions:

“The migraines that plagued me since adolescence disappeared after hormones and family acceptance…. I no longer suffer from those horrible stomach pains caused by stress. They’re gone” (P5, MTF).

This notion corroborates psychoneuroimmunology findings linking social acceptance to physiological regulation.

Theme 3: Healthy presence in society

Family support served as a buffer against societal stigma in two key ways:

Expansion of social relationships

Five participants described moving from isolation to community integration:

“After my surgery and my family’s acceptance, my relationships with them improved a lot. I made some great friends along the way…, including relatives and others. People no longer stare at me at gatherings like they used to” (P2, MTF).

This condition demonstrates the “ripple effect” of family validation on broader social networks.

Increased resilience to social adversity

Four participants developed coping strategies for discrimination:

“My parents’ support made the recovery process much easier. Before the surgery, some of the things people said really hurt. Even now, I still hear comments, but I’m not as sensitive anymore---I try to understand where they’re coming from” (P11, FTM).

This reflects the “social shield” hypothesis, where family support builds emotional armor.

Theme 4: Improvement in family relationships

The transition process paradoxically strengthened familial bonds through three mechanisms:

Increased family satisfaction

Four families exhibited “post-traumatic growth”:

“My mom was very opposed to the surgery. But afterward, she became even more proud of me than when I was her ‘son.’ Wherever she goes, she proudly says, ‘This is my son, my eldest child” (P8, MTF).

This challenges assumptions that gender transition necessarily fractures families.

Increased mutual respect

Three participants described reciprocal understanding:

“I had picked a new name for my ID, but my father preferred a different name. Because he supported me so beautifully, I respected his wish and chose the name he suggested” (P1, FTM).

Illustrates how cultural values can be preserved while affirming identity.

Reduction in family tensions

Six families reported decreased conflict:

“They used to constantly criticize me for how I dressed or acted ‘like a boy,’ saying I lacked grace and domestic skills. I’d either ignore them or act out even more. Now that the surgery is done, we all feel at peace” (P6, MTF).

Supports family systems theory’s emphasis on congruence, which reduces system stress.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored how family support influences transsexual individuals’ experiences during and after gender reassignment. Our findings reveal four fundamental ways family acceptance creates positive change: Fostering hope, improving health, enabling social participation, and strengthening family bonds.

The most profound outcome was participants’ experience of finally living as their true selves. With family support, they described moving from constant inner conflict to peace and self-acceptance. This finding aligns with Ryan et al.’s (2010) findings that family acceptance helps LGBTQ youth develop healthier self-concepts. Participants who had struggled with education due to gender-related stress returned to school after transitioning, showing how family support enables personal growth. Furthermore, a global study by Tan et al. (2020) found that gender congruence—the alignment between one’s internal identity and external presentation—was the single strongest predictor of psychological well-being in transgender populations, underscoring the universal importance of this finding. This finding resonates with research by Glynn et al. (2016), which demonstrated that family rejection is a significant barrier to academic achievement for transgender youth, whereas support facilitates engagement and success.

Interpersonal acceptance–rejection (IPAR) theory suggests that perceptions of acceptance or rejection from close family members have substantial, pancultural effects on psychological adjustment, which may help explain why family support is especially salient in our sample (Rohner & Lansford, 2017). Family systems theory also offers a useful lens: it emphasizes that individuals cannot be understood outside of their relational networks, and that changes in one member (e.g. a gender transition) affect dynamics, roles, and communication patterns throughout the family, which resonates with participants’ reports of shifting family acceptance (Bowen, 1978).

Health improvements were equally significant. Many reported reduced anxiety, depression, and even physical symptoms like stomach pain after gaining family acceptance. These findings support Fuller’s (2017) work showing parental acceptance protects against psychological distress. The mind-body connection was clear, as participants felt emotionally supported, their physical health often improved, too. The link between minority stress, family support, and physiological outcomes is supported by international research (Puckett et al., 2020). For instance, Lefevor et al. (2019) found that transgender individuals with high social support exhibited lower allostatic load (a measure of chronic stress) compared to those with low support.

The minority stress model posits that distal stressors (such as societal stigma and discrimination) and proximal stressors (such as internalized transphobia or expectation of rejection) exert a cumulative burden on minority individuals’ mental health (Meyer, 2003), which aligns with our findings about identity distress and the role interpersonal trust plays in mitigating the effects of social rejection (Smith, 2020).

Socially, family support served as a protective shield. Participants reported being better equipped to handle discrimination and form meaningful relationships when their families supported them. This finding mirrors Rule’s (2018) findings about how family support promotes social well-being in transgender individuals. Even initially hesitant families often became advocates over time, helping their loved ones navigate social challenges. This buffering effect is a consistent theme in global literature. For example, the U.S. trans survey (James et al., 2016) consistently shows that family support is correlated with drastically lower rates of suicide attempts and higher overall life satisfaction among transgender adults.

Within families themselves, relationships are frequently transformed. As participants transitioned, previous tensions eased. Many families grew closer through the process, developing deeper mutual understanding. These observations support Fuller and Rutter’s (2018) description of supportive LGBTQ family relationships as affectionate and secure. This potential for post-traumatic growth and strengthened bonds following a child’s transition has been observed in other cultural contexts, such as in qualitative work by Katz-Wise et al. (2018), who documented a process of “family identity transformation” toward greater resilience and advocacy.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that family support is crucial for transsexual individuals’ well-being during and after transition. When families provide acceptance, their loved ones experience better mental and physical health, stronger social connections, and improved family relationships. These findings highlight the need for programs that educate families about supporting transsexual members. While more research is needed, especially regarding long-term outcomes and different cultural contexts, the message is clear: Family acceptance can be life-changing for transsexual individuals.

However, these findings should also be understood within the Iranian sociocultural and religious context, where prevailing cultural norms and religious beliefs shape family attitudes toward gender transition. In this setting, family support may play an even more decisive role in the well-being of transgender individuals compared to societies with different cultural or legal frameworks. Therefore, the transferability of our results to other contexts is limited, and future research should compare experiences across diverse cultural and religious settings to determine which aspects of family support are culturally specific and which may be universal.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The study focused on Iranian participants so that the findings may differ in other cultural contexts. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling, which may have biased the sample toward individuals with stronger social and family connections, thereby limiting diversity in experiences; Therefore, findings may not fully represent the experiences of less connected or unsupported transgender individuals. Future studies should purposively include transgender individuals without family support to capture a broader range of experiences and provide a more balanced comparison. Furthermore, the small sample size, while sufficient for a phenomenological study, limits the transferability of the findings. The reliance on self-reported data is also a limitation, and participants may have been subject to social desirability bias when describing family support. COVID-19 pandemic restrictions made participant recruitment challenging.

Additionally, there’s limited prior research on transsexual individuals’ family experiences in Iran for comparison. Future research should explore topics like marriage experiences among transsexual individuals and long-term satisfaction with gender reassignment surgery. By better understanding these experiences, we can continue improving support systems for transsexual individuals and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yazd University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Code: IR.YAZD.REC.1400.042). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The research objectives were explained to the participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information. Participants provided written informed consent, with assurances of confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from the participants in a consent form to publish their identifiable data in an open-access online journal.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Interviews and data analysis: Sarina Rahmati Shahrez; Study design: Yasser Rezapour-Mirsaleh; Writing the original draft: Sarina Rahmati Shahreza and Yasser Rezapour-Mirsaleh; Review and editing: Azadeh Choobfroushzadeh; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who participated in this study.

References

Human sexual differentiation begins at conception, with the 23rd pair of chromosomes (XX or XY) determining biological sex (Rice, 2001; Garrett, 2003). However, gender—the psychological and social construct encompassing roles, behaviors, and identities—develops over time, influenced by familial, cultural, and environmental factors (Vasegh Rahimpour et al., 2013). While most individuals experience congruence between their biological sex and gender identity, others face profound dissonance, historically termed gender identity disorder (Halgin & Whitbourne, 2014; Yazdanpanah & Samadian, 2011). Transsexual individuals, classified as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM), often experience this dissonance as a visceral misalignment between their physical bodies and internal selves, leading many to pursue gender reassignment interventions (Nagoshi & Brzuzy, 2010; Abbassian, 2019).

The familial and social challenges of transsexuality

Disclosing a transsexual identity can disrupt family systems, provoking stress, confusion, or rejection (Sieverts, 2018). Societal and familial pressures to conform to birth-assigned gender roles frequently exacerbate psychological distress, contributing to social isolation, academic disengagement, and heightened vulnerability among trans individuals (Zucker & Bradiey, 2005). Conversely, familial acceptance is a critical protective factor, buffering against mental health risks and fostering resilience (McCormick & Baldridge, 2019). Supportive families not only mitigate internalized stigma but also facilitate broader social integration, reducing barriers to well-being (Mirzaei, 2019).

Research gap and study aims

Despite growing recognition of transsexual identities, the transformative role of family support—particularly in the context of gender reassignment surgery—remains understudied, especially in non-Western settings like Iran. Prior research highlights familial acceptance as a predictor of life satisfaction (Rule, 2018), yet few studies explore its lived consequences post-surgery. This study addresses this gap by investigating the relevant factors. By employing a phenomenological approach, we center the voices of transsexual individuals to elucidate the mechanisms through which familial acceptance influences psychological health, social participation, and family dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study employed a descriptive phenomenological approach to explore the lived experiences of transsexual individuals following gender reassignment surgery, with a focus on the role of family support. Phenomenology is uniquely suited to uncover the “essence” of participants’ shared experiences through in-depth engagement with their narratives (Creswell, 2007).

Participants and sampling

The study population included 12 transsexual individuals (5 FTM, 7 MTF) residing in Isfahan City, Iran, all of whom had undergone gender reassignment surgery and reported receiving familial support. Support was operationally defined as verbal affirmation, financial or logistical assistance during transition, or advocacy within social networks, as confirmed through dual interviews with participants and their family members.

Participants were selected via snowball sampling, a non-probability method effective for recruiting marginalized populations (Jalali, 2012). Sampling continued until theoretical saturation was achieved (i.e. no new themes emerged in three consecutive interviews) (Saunders et al., 2018). The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of gender identity disorder by a licensed clinical psychologist (consistent with diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition [DSM-5] criteria at the time of data collection), completion of gender reassignment surgery ≥6 months before the study, and self-reported family support post-surgery. The exclusion criteria were active family conflict (e.g. estrangement, ongoing rejection), comorbid psychological (e.g. untreated psychosis) or physical conditions impairing participation.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews (average duration: 60–90 minutes) were conducted in Persian by Sarina Rahmati Shahreza, using an interview guide developed through expert consultation (see Appendix A for sample questions). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English for analysis. To enhance trustworthiness, member checking was employed: Participants reviewed transcripts and preliminary themes for accuracy (Birt et al., 2016).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s (1978) 7-step phenomenological method.

Transcription: Repeated listening and verbatim transcription.

Significant statements: Extraction of phrases directly related to family support.

Formulated meanings: Interpretation of statements’ underlying meanings.

Theme development: Clustering meanings into thematic groups.

Exhaustive description: Integration of themes into a unified narrative.

Essential structure: Synthesis of the phenomenon’s core structure.

Validation: Participant feedback on findings to ensure accuracy (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

To minimize bias, two independent coders analyzed a subset of interviews, achieving 85% inter-coder agreement (Krippendorff’s α=0.82). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Results

This phenomenological study examined the lived experiences of 12 transsexual individuals (5 FTM, 7 MTF) in Isfahan, Iran, who underwent gender reassignment surgery and received family support. Through in-depth analysis, four central themes emerged, each comprising multiple interrelated categories that collectively illustrate the transformative impact of familial acceptance. Participant quotes are anonymized as P1-P12.

Theme 1: Hope for life

This theme captures participants’ reinvigorated sense of purpose and future orientation following gender affirmation and family support. Three key dimensions emerged (Table 1):

Desire to continue education and increased motivation for learning

Four participants who had previously abandoned education due to gender-related distress reported renewed academic engagement post-transition. Their narratives revealed how family support created psychological safety for learning:

“After my gender reassignment surgery, everything in my life fell into place. I was able to continue my studies, get my degree, and find a job” (Participants No. 4 [P4], FTM).

This aligns with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs - once basic identity acceptance was achieved, self-actualization through education became possible.

Satisfaction with discovering one’s true identity

All participants emphasized this as the most profound outcome, describing it as “finally being whole.” Even those with initial family resistance reported this satisfaction:

“I went through a very difficult journey to become who I am now. I’m happy to have left that body behind and embraced my true identity---as a boy” (P7, FTM).

This echoes Erikson’s theory of identity cohesion as fundamental to psychological well-being.

Arousal of zest for life

Five participants described a dramatic shift from survival mode to active life participation:

“Being satisfied with life is so important. I know I can have a good life. I’ve got the strength, and I strive with all my being to live my days in the best way possible” (P12, MTF).

This transformation suggests family support facilitates the transition from mere coping to thriving.

Theme 2: Enhancement of physical and mental health

Participants reported comprehensive health improvements reflecting the mind-body connection:

Increased self-confidence and positive self-image

Six participants described moving from self-loathing to self-acceptance:

“I feel great about myself. I value who I am and love myself deeply. I’m proud of myself” (P3, MTF).

This feeling mirrors body positivity research, which shows that congruence between physical form and identity boosts self-worth.

Reduction in psychological disorders

Five participants reported clinically significant decreases in anxiety and depression symptoms:

“I deal with a lot of anxiety and stress. Before the surgery, I was very anxious and depressed. I felt awful, but now, thank God, I feel better” (P9, FTM).

This supports minority stress model predictions about reduced internalized stigma.

Decrease in psychosomatic illnesses

Three participants resolved chronic conditions:

“The migraines that plagued me since adolescence disappeared after hormones and family acceptance…. I no longer suffer from those horrible stomach pains caused by stress. They’re gone” (P5, MTF).

This notion corroborates psychoneuroimmunology findings linking social acceptance to physiological regulation.

Theme 3: Healthy presence in society

Family support served as a buffer against societal stigma in two key ways:

Expansion of social relationships

Five participants described moving from isolation to community integration:

“After my surgery and my family’s acceptance, my relationships with them improved a lot. I made some great friends along the way…, including relatives and others. People no longer stare at me at gatherings like they used to” (P2, MTF).

This condition demonstrates the “ripple effect” of family validation on broader social networks.

Increased resilience to social adversity

Four participants developed coping strategies for discrimination:

“My parents’ support made the recovery process much easier. Before the surgery, some of the things people said really hurt. Even now, I still hear comments, but I’m not as sensitive anymore---I try to understand where they’re coming from” (P11, FTM).

This reflects the “social shield” hypothesis, where family support builds emotional armor.

Theme 4: Improvement in family relationships

The transition process paradoxically strengthened familial bonds through three mechanisms:

Increased family satisfaction

Four families exhibited “post-traumatic growth”:

“My mom was very opposed to the surgery. But afterward, she became even more proud of me than when I was her ‘son.’ Wherever she goes, she proudly says, ‘This is my son, my eldest child” (P8, MTF).

This challenges assumptions that gender transition necessarily fractures families.

Increased mutual respect

Three participants described reciprocal understanding:

“I had picked a new name for my ID, but my father preferred a different name. Because he supported me so beautifully, I respected his wish and chose the name he suggested” (P1, FTM).

Illustrates how cultural values can be preserved while affirming identity.

Reduction in family tensions

Six families reported decreased conflict:

“They used to constantly criticize me for how I dressed or acted ‘like a boy,’ saying I lacked grace and domestic skills. I’d either ignore them or act out even more. Now that the surgery is done, we all feel at peace” (P6, MTF).

Supports family systems theory’s emphasis on congruence, which reduces system stress.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored how family support influences transsexual individuals’ experiences during and after gender reassignment. Our findings reveal four fundamental ways family acceptance creates positive change: Fostering hope, improving health, enabling social participation, and strengthening family bonds.

The most profound outcome was participants’ experience of finally living as their true selves. With family support, they described moving from constant inner conflict to peace and self-acceptance. This finding aligns with Ryan et al.’s (2010) findings that family acceptance helps LGBTQ youth develop healthier self-concepts. Participants who had struggled with education due to gender-related stress returned to school after transitioning, showing how family support enables personal growth. Furthermore, a global study by Tan et al. (2020) found that gender congruence—the alignment between one’s internal identity and external presentation—was the single strongest predictor of psychological well-being in transgender populations, underscoring the universal importance of this finding. This finding resonates with research by Glynn et al. (2016), which demonstrated that family rejection is a significant barrier to academic achievement for transgender youth, whereas support facilitates engagement and success.

Interpersonal acceptance–rejection (IPAR) theory suggests that perceptions of acceptance or rejection from close family members have substantial, pancultural effects on psychological adjustment, which may help explain why family support is especially salient in our sample (Rohner & Lansford, 2017). Family systems theory also offers a useful lens: it emphasizes that individuals cannot be understood outside of their relational networks, and that changes in one member (e.g. a gender transition) affect dynamics, roles, and communication patterns throughout the family, which resonates with participants’ reports of shifting family acceptance (Bowen, 1978).

Health improvements were equally significant. Many reported reduced anxiety, depression, and even physical symptoms like stomach pain after gaining family acceptance. These findings support Fuller’s (2017) work showing parental acceptance protects against psychological distress. The mind-body connection was clear, as participants felt emotionally supported, their physical health often improved, too. The link between minority stress, family support, and physiological outcomes is supported by international research (Puckett et al., 2020). For instance, Lefevor et al. (2019) found that transgender individuals with high social support exhibited lower allostatic load (a measure of chronic stress) compared to those with low support.

The minority stress model posits that distal stressors (such as societal stigma and discrimination) and proximal stressors (such as internalized transphobia or expectation of rejection) exert a cumulative burden on minority individuals’ mental health (Meyer, 2003), which aligns with our findings about identity distress and the role interpersonal trust plays in mitigating the effects of social rejection (Smith, 2020).

Socially, family support served as a protective shield. Participants reported being better equipped to handle discrimination and form meaningful relationships when their families supported them. This finding mirrors Rule’s (2018) findings about how family support promotes social well-being in transgender individuals. Even initially hesitant families often became advocates over time, helping their loved ones navigate social challenges. This buffering effect is a consistent theme in global literature. For example, the U.S. trans survey (James et al., 2016) consistently shows that family support is correlated with drastically lower rates of suicide attempts and higher overall life satisfaction among transgender adults.

Within families themselves, relationships are frequently transformed. As participants transitioned, previous tensions eased. Many families grew closer through the process, developing deeper mutual understanding. These observations support Fuller and Rutter’s (2018) description of supportive LGBTQ family relationships as affectionate and secure. This potential for post-traumatic growth and strengthened bonds following a child’s transition has been observed in other cultural contexts, such as in qualitative work by Katz-Wise et al. (2018), who documented a process of “family identity transformation” toward greater resilience and advocacy.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that family support is crucial for transsexual individuals’ well-being during and after transition. When families provide acceptance, their loved ones experience better mental and physical health, stronger social connections, and improved family relationships. These findings highlight the need for programs that educate families about supporting transsexual members. While more research is needed, especially regarding long-term outcomes and different cultural contexts, the message is clear: Family acceptance can be life-changing for transsexual individuals.

However, these findings should also be understood within the Iranian sociocultural and religious context, where prevailing cultural norms and religious beliefs shape family attitudes toward gender transition. In this setting, family support may play an even more decisive role in the well-being of transgender individuals compared to societies with different cultural or legal frameworks. Therefore, the transferability of our results to other contexts is limited, and future research should compare experiences across diverse cultural and religious settings to determine which aspects of family support are culturally specific and which may be universal.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The study focused on Iranian participants so that the findings may differ in other cultural contexts. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling, which may have biased the sample toward individuals with stronger social and family connections, thereby limiting diversity in experiences; Therefore, findings may not fully represent the experiences of less connected or unsupported transgender individuals. Future studies should purposively include transgender individuals without family support to capture a broader range of experiences and provide a more balanced comparison. Furthermore, the small sample size, while sufficient for a phenomenological study, limits the transferability of the findings. The reliance on self-reported data is also a limitation, and participants may have been subject to social desirability bias when describing family support. COVID-19 pandemic restrictions made participant recruitment challenging.

Additionally, there’s limited prior research on transsexual individuals’ family experiences in Iran for comparison. Future research should explore topics like marriage experiences among transsexual individuals and long-term satisfaction with gender reassignment surgery. By better understanding these experiences, we can continue improving support systems for transsexual individuals and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yazd University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Code: IR.YAZD.REC.1400.042). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The research objectives were explained to the participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information. Participants provided written informed consent, with assurances of confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from the participants in a consent form to publish their identifiable data in an open-access online journal.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Interviews and data analysis: Sarina Rahmati Shahrez; Study design: Yasser Rezapour-Mirsaleh; Writing the original draft: Sarina Rahmati Shahreza and Yasser Rezapour-Mirsaleh; Review and editing: Azadeh Choobfroushzadeh; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who participated in this study.

References

Abbassian, P. (2019). [The rights of TS (transsexual) patients after gender reassignment in Iranian law (Persian)]. Journal of Humanities and Islamic Knowledge, 1(1), 35-50. [Link]

Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation?. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. [DOI:10.1177/1049732316654870] [PMID]

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. New Jersey: Jason Aronson. [Link]

Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In R. Valle & M. King (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp. 48-71). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Link]

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. [Link]

Fuller, K. A. (2017). Interpersonal acceptance-rejection theory: Application to lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(4), 507-520. [DOI:10.1111/jftr.12219]

Fuller, K. A., & Rutter, P. A. (2018). Perceptions of parental acceptance or rejection: How does it impact LGB adult relationship quality and satisfaction? Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14(4), 317-336. [DOI:10.1080/1550428X.2017.1347077]

Garrett, S. (2003). Sociology of gender (K. Baghaei, Persian trans). Tehran: Digareh Publications. [Link]

Glynn, T. R., Gamarel, K. E., Kahler, C. W., Iwamoto, M., Operario, D., & Nemoto, T. (2016). The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 336-344. [DOI:10.1037/sgd0000171] [PMID]

Halgin, R. P., & Whitbourne, S. K. (2018). Psychopathology [Y. Seyed Mohammadi, Persian trans]. Tehran: Ravan Publications. [Link]

Jalali, R. (2012). [Sampling in qualitative research (Persian)]. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences, 1(4), 310-320. [Link]

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Link]

Katz-Wise, S. L., Budge, S. L., Orovecz, J. J., Nguyen, B., Nava-Coulter, B., & Thomson, K. (2017). Imagining the future: Perspectives among youth and caregivers in the trans youth family study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 26–40. [PMID]

Lefevor, G. T., Smack, A. C. P., Golightly, R. T., & Stone, E. A. (2019). The relationship between religiousness and health among transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(4), 425-435. [DOI:10.1037/bul0000321] [PMID]

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [DOI:10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8]

McCormick, A., Schmidt, K., & Terrazas, S. R. (2016). Foster family acceptance: Understanding the role of foster family acceptance in the lives of LGBTQ youth. In A. McCormick (Ed.). LGBTQ youth in foster care: Empowering approaches for an inclusive system of care. New York: Routledge. [Link]

Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. [DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674]

Mirzaei, H. R. (2019). [Hidden Me: Let's get to know transgender people better (Persian)] Tehran: Andisheh Ehsan Publications. [Link]

Nagoshi, J. L., & Brzuzy, S. I. (2010). Transgender theory: Embodying research and practice. Affilia, 25(4), 431-443. [DOI:10.1177/0886109910384068]

Puckett, J. A., Maroney, M. R., Wadsworth, L. P., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2020). Coping with discrimination: The insidious effects of gender minority stigma on depression and anxiety in transgender individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 176-194. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22865] [PMID]

Rice, F. P. (2001). Human development: A lifespan approach (4th ed.) [M. Foroughan, Persian trans]. Tehran: Arjmand Publications. [Link]

Rohner, R. P., & Lansford, J. E. (2017). Deep structure of the human affectional system: Introduction to interpersonal acceptance-rejection theory. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(4), 426-440. [DOI:10.1111/jftr.12219]

Rule, M. E. (2018). Parents’ emotional experiences of their transgender children coming out [doctoral dissertation]. Minneapolis: Walden University. [Link]

Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205-213. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x] [PMID]

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893-1907. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8] [PMID]

Sieverts, J. E. (2018). The lived experience of Christian parents of transgender children: An exploration of faith and parenting through the framework of family systems theory [doctoral dissertation]. Aston: Neumann University. [Link]

Smith, S. K. (2020). Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Persons’ Health and Well-Being: Reducing Minority Stress to Improve Well-Being. Creative Nursing, 26(2), 88-95. [DOI:10.1891/CRNR-D-19-00083] [PMID]

Tan, K. K. H., Ellis, S. J., Schmidt, J. M., & Byrne, J. L. (2020). Mental health inequities among transgender people in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the counting ourselves survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2862. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17082862] [PMID]

Vaseq Rahimpour, S. F., Mousavi, M. S., Raeisi, F., Khodabandeh, F., & Bahrani, N. (2013). [Comparing quality of life in patients with gender identity disorder after gender reassignment surgery with normal women in Tehran in 2012 (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 16(74), 10-19. [DOI:10.22038/ijogi.2013.1977]

Yazdanpanah, L., & Samadian, F. (2011). [A study of gender identity disorder with emphasis on the role of the family: A comparative study of clients referred to the Welfare Organization of Kerman Province (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Social Studies, 5(1), 176-208. [Link]

Zucker, K. J., & Bradiey, S. J. (2005). Gender identity and psychosexual disorder. FOCUS, 3: 593-617. [DOI: 10.1176/foc.3.4.598]

Appendix A: Sample interview questions

1. Family support experiences

Can you describe how your family reacted when you first disclosed your transsexual identity?

What specific actions or behaviors from your family felt most supportive during or after your gender reassignment process?

Were there moments when you felt your family’s support was lacking? How did this affect you?

2. Psychological and emotional impact

How did your family’s support (or lack thereof) influence your mental health before and after surgery?

Can you share an example of how family support helped you cope with challenges related to your transition?

3. Social and functional outcomes

How did your family’s attitude affect your ability to engage socially (e.g. friendships, work, education) post-surgery?

Did your family advocate for you in social settings (e.g. correcting pronouns, defending your identity)? If so, how did this impact you?

4. Family dynamics

How have your relationships with family members changed since your surgery?

What do you wish your family had understood earlier about your experience as a transsexual individual?

5. Post-surgery reflections

Looking back, what role do you feel family support played in your overall satisfaction with your gender reassignment journey?

If you could advise other families of transsexual individuals, what would you emphasize about providing support?

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/08/29 | Accepted: 2025/09/29 | Published: 2026/12/28

Received: 2025/08/29 | Accepted: 2025/09/29 | Published: 2026/12/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |