Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 57-82 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yazdanian H, Rekhne Z B, Soltani A, Vakili A, Reza M, Zareii S, et al . Virtual Reality to Improve Joint Attention Skills in Children With Autism: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :57-82

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1047-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1047-en.html

Hassan Yazdanian1

, Zohre Bagheri Rekhne2

, Zohre Bagheri Rekhne2

, Ariana Soltani3

, Ariana Soltani3

, AmirMohammad Vakili3

, AmirMohammad Vakili3

, Mohammad Reza3

, Mohammad Reza3

, Sajjad Zareii3

, Sajjad Zareii3

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Talieh Zarifian *5

, Talieh Zarifian *5

, Zohre Bagheri Rekhne2

, Zohre Bagheri Rekhne2

, Ariana Soltani3

, Ariana Soltani3

, AmirMohammad Vakili3

, AmirMohammad Vakili3

, Mohammad Reza3

, Mohammad Reza3

, Sajjad Zareii3

, Sajjad Zareii3

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Talieh Zarifian *5

, Talieh Zarifian *5

1- Research Unit of Mathematical Sciences, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Tose’e Darman Sarv Inc., Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,t.zarifian@yahoo.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Tose’e Darman Sarv Inc., Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Joint attention (JA), Initiating joint attention, Responding to joint attention, Social communication skills, Virtual reality (VR)

Full-Text [PDF 734 kb]

(436 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (868 Views)

2. Material

Informed consent materials

Consent to participate in the project

Comparative study on the effectiveness of JA interventions: Virtual reality tasks versus conventional treatments in enhancing social-communication skills of school-aged children with autism

Dear Madam/Sir

You are hereby invited to participate in the research mentioned above. The information related to this research is presented in this service sheet, and you are free to participate or not participate in the research.

You need not make an immediate decision, and you are welcome to direct your inquiries to the research team and seek counsel from anyone you deem appropriate. Before endorsing this consent form, kindly ensure that you have comprehended all the details and that all your inquiries have been addressed to your satisfaction.

The executive officer of this project is Zohra Bagheri Rekhne. Talieh Zarifian and Hassan Yazdanian supervise and manage the project scientifically and operationally.

Research Executive Officer

Zohre Bagheri Rekhne

1. I am cognizant that the primary objective of this research is to compare the efficacy of JA interventions employing virtual reality games against conventional interventions in enhancing the social-communication proficiencies of children with autism. This endeavor aims to contribute to the advancement of rehabilitation approaches for children with autism in subsequent times.

2. I am aware that my involvement in this research is entirely voluntary, and I am under no compulsion to partake in this study.

3. I comprehend that even after providing my consent for participation, I retain the prerogative to withdraw from the research at any juncture, with the condition of informing the moderator about my decision.

4. I acknowledge that video recording of my child will transpire during the assessment session within this research, facilitating the evaluation of JA and social-communication skills. I am informed that the recorded video of my child will be securely stored in an encoded format under the supervision of the senior researcher of the research team. I concur that the use of this data for research and clinical purposes related to the theme of this research is unrestricted, in my view.

5. The involvement of my child in this research will encompass the following steps:

Upon your participation, a form will be furnished to gather your child’s familial and medical history. Initial pre-tests will ensue to assess eligibility for research entry and your child’s capacity to engage with a virtual reality headset. Subsequently, you will receive questionnaires to evaluate your child’s JA and social-communication skills.

The ensuing phase involves a test that gauges your child’s proficiency in JA. It is noteworthy that this test necessitates the scrutiny of two independent experts, thereby mandating the recording and encoding of the test session video.

Following this, your child will be acquainted with the functioning of the virtual reality system through two instructional games. Before embarking on therapy sessions, a distinct evaluation of your child’s JA will transpire using a virtual reality game.

Upon the culmination of these preliminary stages, the intervention sessions will commence, hosted within one of the designated treatment rooms at your child’s school. Initially, the therapist will engage in conversation and interaction with your child. The children will be randomly assigned to two groups: The experimental and the control.

For the experimental group, a set of 5 therapeutic scenarios has been devised to be dispensed across 15 sessions. Conversely, the control group will be exposed to an autism-specific animation. Over 5 weeks, three sessions will convene each week, with each lasting approximately 15 minutes. The conduct and oversight of each session will fall under the purview of a proficient therapist, who will accompany the child throughout.

Each session will introduce a treatment scenario, and the maximum duration will be around 15 minutes. As the sessions conclude, reassessment tests will be administered to evaluate the intervention’s efficacy. Furthermore, one month after the intervention’s conclusion, a follow-up evaluation will be conducted to assess the durability of the intervention’s impact.

6. The prospective advantages stemming from your child’s participation in this study encompass:

- All administered tests, which are considered a form of developmental observation and assessment of JA and social-communication skills, will be provided at no cost.

- A comprehensive evaluation of your child will be conducted, encompassing sensory profiling, speech and language health assessment, and evaluation of JA and social-communication skills. If any form of disorder is identified, you will receive a complimentary consultation.

- Should the identified issue be mild, a free treatment session will be offered. Conversely, for more substantial concerns, you will be introduced to suitable service provider centers.

7. Potential risks and complications associated with participation in this study are as follows:

This research is designed to ensure the absence of harm or complications for your child. The sole conceivable side effect could be nausea, which may occur in a minority of individuals due to the utilization of virtual reality headsets, akin to motion sickness. Should your child experience such discomfort during the initial assessment session, they will be excluded from further participation in the study.

8. I am cognizant that all individuals involved in this research endeavor are bound to maintain the confidentiality of all information pertinent to me. They are exclusively authorized to publish general and aggregated outcomes derived from this research, refraining from any mention of my identity or specific particulars.

9. I am aware that the research ethics committee holds the capacity to access my information for the sole purpose of overseeing the adherence to my rights.

10. I comprehend that I shall not incur any charges for the administration of any of the conducted tests.

11. Zohra Bagheri was introduced to me to answer my possible questions, and I was told to share with her and ask for guidance whenever there is a problem or question related to participating in the mentioned research.

His address and cell phone numbers were presented to me as follows:

● Address: Evin. Daneshjou Blvd. Koudakyar dead end. University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Speech Therapy Department.

● Mobile phone: 00989379585753

12. I understand that if, during and after the research, any problem, both physical and mental, occurs to me due to participating in this research, the treatment of complications, their costs, and the related compensation will be the responsibility of the administrator.

13. I know that if I have problems or objections to the participants or the research process, I can contact the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences at the address: Evin. Daneshjou Blvd. Koudakyar dead end. Call and present your problem verbally or in writing.

14. This information and informed consent form are prepared in two copies, and after signing, one copy will be at my disposal, and the other copy will be at the administrator’s disposal.

Having perused and comprehended the aforementioned content, and drawing from this understanding, I hereby affirm my informed consent to engage in this research.

Signature of the participant

I, Zohra Bagheri, acknowledge my responsibility to uphold the duties associated with the role of moderator as stipulated in the above provisions. I commit to making every effort to safeguard the rights and well-being of the participants involved in this research.

Consent form

I, undersigned on behalf of [participant’s name], having comprehensively understood the aforementioned, hereby provide my consent for [participant’s name], who is partaking as a subject in the research study titled “comparison of the effectiveness of using virtual reality games and conventional therapy on improving social communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder at school age.”

I am aware that all data collected from the participant and me, including names, will be maintained in strict confidentiality. The research outcomes will be disseminated broadly, reflecting the collective findings of the study group. If necessary, individual results will be presented without divulging identities or personal attributes.

I declare that I absolve the designated doctor(s) overseeing this project from any actions detailed in the information sheet, unless their actions are proven to be negligent.

This agreement signifies my commitment to refrain from pursuing legal actions against [researcher’s name] in cases where actions are taken in accordance with established rules and regulations.

I understand that my consent is voluntary and that I retain the liberty to withdraw from the research at any time, provided I notify the administrator. My decision to withdraw will not hinder my access to routine medical services.

Signature and fingerprints of the guardian

Surname and signature of the witness

Signature of the researcher

3. Material

Scenarios

The VR treatment program consists of tutorial scenarios, treatment scenarios (Mina’s farm), and evaluation scenarios (Sina’s home). In the protocol manuscript, the evaluation scenarios are called “assessment” game or “AG.”

Tutorial scenarios

One objective of the tutorial scenarios is to introduce the child to the VR environment and to allow them to explore the farm setting.

In the first tutorial scenario, the child will search for and learn about large targets such as a house, a car, and a tree. By staring at the target for at least 200 ms, the child will receive rewards in the form of audio and visual effects. In addition to being larger, the target items in this scenario will be highlighted and activated by several colored arrows. The therapist will activate the target character through a panel and instruct the child on which item to find. The tutorial scenario does not include scoring or varying degrees of difficulty.

The second tutorial scenario builds on the skills learned in the first, teaching the child to navigate the virtual reality environment and locate smaller targets, such as a chicken, a rabbit, and a goat. The child may also need to follow the path of these targets. Similar to the first tutorial scenario, the therapist will activate the target item through a panel and instruct the child on which item to find.

Treatment scenarios

The first three treatment scenarios involve responding to JA. The first focuses on sound localization (orienting attention), the second on following hand gestures and head movements (orienting attention and shifting attention), and the third on visual pursuit (orienting attention, sustaining attention, and shifting attention). The fourth and fifth scenarios focus on initiating JA by drawing the avatar’s (Mina’s) attention. These scenarios are implemented independently of each other, meaning that failure in responding to JA scenarios does not prevent the administration of JA initiation scenarios.

During each session, which typically lasts less than 20 min, one or two scenarios will be performed. Each scenario is designed to be completed in no more than 5 minutes. After each scenario, there will be a break of approximately three minutes. The same scenario will then be repeated either with the previous settings or with new settings, as explained in each scenario.

The default plan is to practice each scenario for three sessions, but this can be adjusted based on the child’s progress. The child needs to master each step before moving on to the next. If the child is unable to reach the desired level after three failed sessions, she/he will return to the previous level or tutorial scenarios.

The VR environment for treatment scenarios is set on a farm and features a virtual character along with four characters: a horse, a cow, a cat, and a dog.

0. Explore Mina’s farm

In the first therapy session, the child will be introduced to Mina (virtual avatar) and her farm environment. This scenario is designed to familiarize the child with the farm and its various interactive elements. Mina will introduce herself and encourage the child to explore the farm and interact with the different characters and objects. This session serves as an introduction to the VR environment and sets the stage for subsequent scenarios.

1. Find the sound source (responding to JA)

In this scenario, the child will be tasked with identifying the direction of each animal’s sound, recognizing its source using auditory clues, and focusing on the target item. Once the child has located the target character (e.g. a cat) and gazed at it for at least 200 ms, a visual reward will be presented to the character, and an auditory reward (sound effect) will be played. This scenario is designed to improve the child’s auditory and visual processing skills, as well as their ability to focus on a specific target item.

The therapist can choose the scenario through dedicated software running on a laptop, hereafter called the therapist panel. The panel allows the therapist to control the virtual reality environment. When a scenario is chosen, the scene will be displayed on both the VR headset and the therapist’s panel. Through the panel, the therapist can choose which character to produce a sound for and direct the child to find that character.

If the child fails to locate a particular item, it cannot be presented again immediately. Instead, the therapist will present the child with another item to find. This issue helps to prevent frustration and encourages the child to continue exploring the virtual environment.

In this scenario, there are four interactive characters - a dog, horse, cow, and cat - and the child will have three chances to find each character. If the child fails to locate each of the elements, they will return to the tutorial scenarios. To complete the scenario, the child must obtain a score of 70% or higher. This score threshold was chosen based on previous research in technology-assisted education. For example, if the total number of points available in the scenario is 12, the child must collect 8 or more points to complete it successfully. If the child obtains fewer than 8 points, the scenario will be repeated.

Both the software and the therapist record the child’s performance score. For each correct answer, the child will receive a score of one. If an item cannot be located, the child will receive a score of zero. The final score will be the total points the child earns throughout the scenario.

2. Follow Mina’s pointing (responding to JA)

In this particular situation, the child is required to demonstrate an understanding of the directional cues from Mina’s hand and/or head. The child should locate the target item (cat, dog, cow, or horse) by following the clues presented by Mina and fixating on it.

The cue level (referred to as “CL” or “Cue Level”) is a crucial factor to consider in this scenario. Initially, in high CL, Mina utilizes hand and head movements to show the interactive target character. Consequently, the child is required to follow Mina’s hand direction. As CL decreases, in low-CL conditions, Mina relies solely on head movements to direct the child’s attention toward the interactive target character. The child is then required to follow Mina’s head direction. Once the child successfully directs their attention to the target character, a visual reward is presented on the character, accompanied by an auditory reward.

If the child initially fails to pay attention to Mina, the character employs gestures, such as waving its hand, and vocal expressions, such as “Baby” and “I’m here!” “Hey!” or “Look at me!” to capture the child’s attention. The therapist can configure and control the CL of the scenario utilizing the therapist panel, allowing for customization and adjustment as needed. The scoring method employed in this scenario remains similar to the one used in the first scenario.

3. Pursuit Mina’s animals (responding to JA)

Within this scenario, the child is tasked with visually tracking the path of interactive characters. The scenario comprises two distinct modes. In the first mode, known as “mode 1,” the sound associated with the target character is played, prompting the child to fixate on the character upon hearing it. Subsequently, once the gaze fixation is complete, the interactive target character initiates to move. The child’s objective is to track the character’s trajectory subsequently. It should be noted that the start and the end points of the character’s path are clearly defined.

The second mode, referred to as “mode 2,” involves Mina capturing the child’s attention by waving her hand and calling out “Baby!” “I’m here!” “Hey!” or “Look at me!” Once the child directs their gaze toward Mina, she indicates one of the target characters by pointing to it. The child’s task is to locate the designated interactive character and maintain visual fixation on it by interpreting Mina’s hand and head direction. Upon successful fixation, the target character begins its movement, requiring the child to track its path subsequently.

The overall scoring system for this scenario remains similar to that of the first, with two main differences. Firstly, for the child to receive a reward and be considered to have performed appropriately, they must track at least 70% of the desired character’s path (not necessarily continuously). The therapist’s panel can assess this criterion. In such instances, the score for that specific character will be recorded for the child.

The second difference concerns how failures are handled in the scenario, which varies depending on the mode. If the child fails to adhere to any element in mode 1, they are directed back to the first scenario. Conversely, if the child fails to follow any of the elements in mode 2, they are redirected back to the second scenario. Therefore, unlike the first and second scenarios, the child does not directly return to the educational scenario but rather to the mode they failed in.

4. Show Mina what happened (initiating JA)

In this scenario, the child is required to capture Mina’s attention by drawing it towards an intriguing situation that has happened. Only one interactive character is present in this scenario, positioned alongside Mina. The target appears on the left or right side of Mina, based on the therapist panel configuration. The interesting situation entails the interactive character spinning around, in contrast to previous scenarios. Upon the child fixing their gaze on the character, the character suddenly performs a peculiar movement (e.g. a cat jump). After that, Mina says, “What happened?” The child is then expected to shift their gaze towards Mina and maintain a visual fixation on her. During this time, Mina, with its head held high and its hands raised, asks, “What’s wrong?” before proceeding towards the target character. The child is once again required to fixate their gaze on the target character. After that, the peculiar movement recurs. Mina then responds excitedly, saying, “Wow, very interesting...!” Following this, a visual reward is provided to the character and accompanied by an auditory reward.

Through the panel, the therapist can start the session with the older animals, and after the children are successful, choose the smaller animals. This distinction in character sizes is intended for varying difficulty levels. This act allows for customization and adjustment based on the child’s abilities and progress.

The scoring method used in this scenario is similar to that in the first scenario. A score of above 70% is considered successful, indicating that the child has effectively completed the task. Scores below 70% but above zero indicate a need for repetition, while a score of zero indicates that the child should return to the training scenario for further practice.

5. Draw Mina’s attention (initiating JA)

This scenario is similar to “Show Mina what happened,” albeit with a notable distinction. In this case, when an appealing situation captures the child’s attention, there is no verbal cue from Mina. Instead, the child is required to gaze at Mina. Subsequently, Mina elevates its head from the phone and directs its gaze toward the child while uttering the phrase “What happened?” The subsequent session of events remains consistent with the previous scenario. The scoring mechanism employed is akin to that of the previous scenario.

If desired, the therapist retains the right to modify the sequence of presentation and the placement of the target character using the therapist panel.

Assessment scenarios

The objective of these scenarios is to develop a cross-validation tool for assessing JA in a virtual reality setting. The tool comprises 6 distinct scenarios, each lasting approximately 10 to 15 min. Adequate breaks can be provided to the child between each scenario, as required. Notably, this assessment scenario occurs within a spatial setting distinct from the treatment virtual environment. In the protocol manuscript, the evaluation scenarios are called “Assessment” Game or “AG.”

The assessment is executed within a virtual environment of a residential setting, featuring an avatar named “Sina”, as well as target characters including an alarm clock, television, cat, and a disco light. The description of the scenario and how to score are as follows:

1. Finding the alarm clock (responding to JA)

In this scenario, the child’s task is to locate the alarm clock upon hearing its sound. The child is required to focus their attention on the alarm clock for a minimum duration of 200 ms. The child is provided with three opportunities to accomplish the task. In the first instance, the target character (alarm clock) is presented without any additional cues. If the child fails to identify the alarm clock, a cue is provided in the form of a clock vibration. If the child still struggles to locate the alarm clock, another cue is introduced, this time highlighting the clock. The cue levels are configured through the therapist panel. After completing the task, the child receives visual and auditory rewards.

Scoring for this scenario is as follows: If the child successfully identifies the alarm clock without any cues, they receive three points. If they require one cue to identify, they earn two points. If two cues are needed to locate the alarm clock, the child receives one point. If the child fails to identify the alarm clock even with the provided cues, they receive 0 points.

2. Attention to Sina’s pointing (responding to JA)

In this scenario, the child’s task is to observe and attend to Sina’s pointing. Sina is sitting on a sofa and captures the child’s attention by uttering “Baby!” “I’m here”… and other relevant cues. Once the child’s attention is obtained, Sina initiates the task by directing the child’s head toward the TV on a nearby table. If the child fails to track Sina’s pointing, Sina points to the TV with its hand while simultaneously adjusting its head orientation. If the child still struggles to identify the TV, another cue is introduced by highlighting it. Following the virtual character’s gaze toward the TV, the screen turns on, displaying an image of SpongeBob. The cue levels are configured through the therapist panel. After completing the task, the child receives visual and auditory rewards. Scoring for this scenario is as follows: If the child successfully follows Sina’s head movement, they receive 3 points. If the child tracks both the head and hand movements, they earn two points. If the child successfully follows the head and hand movements while using the provided visual cue, they receive one point. If the child fails to complete the task, they receive 0 points.

3. Tracking cat’s path (responding to JA)

In this scenario, the child’s visual tracking is assessed using a virtual cat. The session begins with the cat emitting a call, prompting the child to locate the cat within the virtual reality home. Once the child finds the cat and directs their focus to it, the cat moves towards its designated mattress. The child’s task is to follow the cat’s path until it reaches its mattress.

As long as the child does not look at the cat, the cat does not move. If the child has difficulty tracking the cat’s path, a series of arrows is introduced to guide it. If the child continues to struggle, the path is not only highlighted but also illuminated and highlighted by the cat. The cue levels are configured through the therapist panel. After completing the task, the child receives visual and auditory rewards.

Scoring for this part is as follows: If the child successfully follows the cat’s path without guidance, they receive 3 points. If the child requires the path to be highlighted to follow it, they earn two points. If the path and the target character are highlighted and the child follows the path, they receive one point. If the child fails to follow the path adequately, the child receives 0 points.

4. Requesting (initiating JA)

In this scenario, the focus is on the child’s ability to initiate JA through requesting. In the virtual house setting, there are two disco lights on either side of Sina. The assessment begins with Sina capturing the child’s attention through verbal cues such as “Baby!” “Hey, I’m here,” and others. Once the child’s attention is obtained, Sina proceeds by counting “one, two, three,” at which point one of the disco lights on either side of Sina is randomly illuminated. The child is then required to gaze at the illuminated disco light. Once the child has fixed their gaze on the light, it turns off. To initiate the reappearance of the light dance, the child must shift their attention to Sina and request by staring at him. Upon the child’s request, Sina repeats the countdown (“one, two, three”) and the disco light turns on again. If the child continues to gaze at the disco light, the scenario is completed, and reward effects are played.

The therapist can conduct this evaluation scenario up to three times. Scoring for this part is as follows: If the child successfully initiates JA on the first attempt, they receive 3 points. If they succeed on the second attempt, they earn 2 points. If the child completes the task on the third attempt, they receive 1 point. If the child fails to initiate JA, they receive 0 points.

5. Show Sina disco light is on (initiating JA)

This scenario focuses on the child’s ability to initiate JA straightforwardly. Similar to the previous scenario, there are two disco lights on each side of Sina. One of the disco lights illuminates randomly. Once the child’s attention is directed to the illuminated disco light, they must gaze at it. Subsequently, Sina asks, “What happened?” At this moment, the child shifts their attention toward Sina and maintains eye contact. Finally, the child attempts to direct Sina’s attention to the disco light by once again looking at the light. After gazing at the disco light, Sina responds excitedly, “Wow, very interesting...!” By completing the task, the auditory reward will be played.

The evaluation scenario can be conducted by the therapist up to three times. Scoring is as follows: If the child accomplishes the task on the first attempt, they receive three points. If they succeed on the second attempt, they earn two points. If the child completes the task on the third attempt, they receive 1 point. If the child fails to initiate JA, they receive 0 points.

6. Draw Sina’s attention (initiating JA)

This assessment scenario builds upon the previous one, focusing on the child’s ability to initiate JA in a more challenging context. Similar to the previous scenario, two disco lights remain around Sina, but in this case, Sina’s attention is not initially directed toward the child. The child’s task is to spontaneously capture Sina’s attention by gazing at Sina after focusing on the dancing light. Subsequently, the child must once again shift their attention towards the disco light, attempting to draw Sina’s attention to the illuminated position. After gazing at the disco light, Sina responds excitedly, “Wow, very interesting...!” Upon completing the task, the auditory reward will be played.

The therapist can conduct this evaluation scenario up to three times. Scoring for this part is as follows: If the child successfully initiates JA on the first attempt, they receive three points. If they succeed on the second attempt, they earn two points. If the child completes the task on the third attempt, they receive 1 point. If the child fails to initiate JA, they receive 0 points.

Total points for the entire assessment: 18 points.

Examples of the items suggested by the expert panel to improve the face and content validity of the scenarios:

- Changing the avatar of Sina and Mina,

- Improving Sina’s voice in the assessment scenario,

- Adding clapping animation for Mina and Sina during rewards,

- Adding different types of expressions for drawing the user’s attention, like “baby,” “look at me,” “I’m here,” etc. as well as hand-waving animation for avatars,

- Adding verbal cues such as “What’s that sound?” or “Where does it go?” to scenarios,

- Adding the explore Mina’s farm scenario and adding words for Mina in the scenario: I’m Mina, this is my farm. Let’s see what’s going on,

- Adding “Wow, very interesting...!” to scenarios five and six in the treatment scenarios,

- Improving the sound and appearance of animals,

- Considering a clear beginning and end for the “Pursuit Mina’s animals” and “Tracking Cat’s path” scenarios, for example, consider a food dish for a cat and a hut for a dog.

- Making the eyes of avatars and animals bigger and clearer,

- Changing some unfamiliar items for students in the virtual environment, such as replacing a tractor with a van,

- Replacing the photo frame with the TV in the assessment scenario,

- Considering different animations and cheering sounds for each scenario,

- Making avatars more interactive by adding head movement to them to stare and follow the target item in all scenarios,

- Changing the placement of animals in the “Pursuit Mina’s animals” scenario to avoid confusion,

- Replacing the pigeon with the chicken in the tutorial scenarios,

- Adding the requesting section to the assessment scenario,

- Changing the idea of IJA scenarios in treatment and assessment scenarios,

- Adding the possibility to activate some cues to the scenarios, for example, the possibility to turn on the path in the “Pursuit Mina’s animals” scenario,

- Add a stop option to all scenarios,

- Improving user interface,

- Changing the name of the assessment scenario’s avatar from Nima to Sina.

These suggestions were implemented in the virtual scenarios.

Material 4. Instructions for behavioral sampling to assess JA skills

This measure was designed to gather participants’ behavioral samples to evaluate their JA skills. The inspiration for this measure came from the measure created by Ravindran et al. (2019) and the CSBS (Wetherby & Prizant, 2002).

1. Implementation instructions

The evaluation period using this tool is set at 20 min. Within this timeframe, the child will engage in a structured 20-min session with the evaluator, including 2-10 min of warm-up and 2-10 min of communication temptations. The introduced toys, deemed “communicative temptations,” are carefully chosen to suit the age group of school children.

The designated toys include:

A. two mechanical wind-up toys (preferably animal-shaped), B. a toy with light and sound (e.g. spinning top toy with LED light and music), C. a transforming helicopter, D. three books, and E. two-color posters.

Preparation toys

The aim is to evaluate nonverbal, vocal, and gestural interaction skills (both with and without eye contact) under the most favorable conditions. As a result, the time spent playing with each toy may fluctuate depending on the participant’s level of interest and participation.

The child’s caregiver may choose to be present or absent during the session. If they are present, they are encouraged to respond naturally to the child’s communicative behavior without guiding the child’s actions.

Throughout the sampling session, the evaluator is advised to verbally respond to the child’s communicative behavior, speaking only after the child has focused attention on a topic or initiated a communication act. The use of questions is discouraged unless necessary. It is vital for both the assessor and the caregiver to maintain a balanced, natural level of communication.

2. Features of the assessment room

The evaluation session takes place in a treatment room free of distractions, such as additional toys and noise. A small room (3×4) with visually stimulating elements, such as pictures and colorful wall hangings, is preferred to promote gesturing. All objects, except those being used, should be kept out of the child’s sight and reach during the sampling.

The room is furnished with a table and chair for the child, and two chairs for the therapist and parent. The assessments are carried out during the day, ensuring sufficient lighting and proper ventilation.

3. Sitting position

During the warm-up or preparation phase, the child may sit on the floor, on the caregiver’s lap, or at the table. However, when it comes to communication temptations, the child should be seated on a chair, with a table in front of them serving as a boundary. The evaluator should position themselves opposite the child, leaning in slightly to enhance the interactive appearance during the recording. The camera is set up behind the table to capture the child’s and evaluator’s facial expressions and body movements.

All items and toys not currently in use should be kept out of sight and reach. They must be stored in a kit or box for easy access during sampling.

4. Warm-up or preparation

The caregiver may attend the preparation meeting, but attendance is not required. This period allows the child to explore the room and become comfortable with the environment. The evaluator should understand the significance of an extensive warm-up, lasting 2-10 min, during which the child is subjected to minimal demands and pressure.

At the outset, the evaluator may engage in casual conversation with the caregiver to foster a relaxed atmosphere. After a few minutes, the evaluator is encouraged to establish an emotional connection with the child, for example, by smiling and adopting a melodious tone of voice.

The section on communication temptations commences when the child appears comfortable, as evidenced by smiles or laughter, or after the ten-minute preparation period has elapsed.

5. Behavioral sampling method of communication temptations

Before starting, the caregiver is provided with the following instructions by the evaluator

● We want to obtain examples of how your child communicates through words, sounds, and gestures.

● We present some situations encouraging communication.

● Please try to minimize commenting and questioning and maintain natural communication.

Also, the evaluator should naturally respond to the child’s communicative intent during temptations. Specific communication temptations should be introduced sequentially, with a 1-2 min allocated duration for each.

Opportunity number one: Mechanical windup toys (horse)

Activate and deactivate the toy, waiting for the child’s reaction. If there is no response after about 10 seconds, place it in front of the child and wait. Reactivate the toy after the child’s first communication signal and, after the second signal, say, “Bye-bye, horse!”

Opportunity number two: Mechanical windup toys (mouse)

Same as the opportunity number one.

Opportunity number three: Spinning top toys (with light and sound)

Activate the toy and wait for the child’s reaction. If the toy becomes deactivated and there is no response, put it closer to the child and wait for 10 seconds. Reactivate the toy after the child’s first communication signal and, after the second signal, say, “The spinning top is gone!”

Opportunity number four: Transforming helicopter

Activate and wait for the child’s reaction. If there is no response, place it in front of the child and wait. Reactivate after the first communication signal and, after the second signal, say, “Bye-bye, helicopter!”

Opportunity number five: posters

Call the child’s name and direct their attention to the pictures on the wall. Present the second poster after the book opportunity with a gap between them.

Opportunity number six: Books

Use three books, encouraging the child to choose one. After the child looks at a book, take it off the table.

Note: unused items should be kept out of the child’s sight and reach.

6. Scoring

The sessions will be video recorded and coded by Simple Video Coder (SVC) (Barto et al., 2017) for 15 distinct conditions, as follows:

1. Responding, request with eye contact (Response_request_ec)

2. Responding, request without eye contact (Response_request_wec)

3. Responding, request with pointing (Response_request_pointing)

4. Responding, other than requesting eye contact (Response_without_request_ec)

5. Responding, other than request without eye contact (Response_without_request_wec)

6. Responding, other than request with pointing (Response_without_request_pointing)

7. Initiating, request with eye contact (Initiation_request_ec)

8. Initiating a request without eye contact (Initiation_request_wec)

9. Initiating a request with pointing (Initiation_request_pointing)

10. Initiating, other than request with eye contact (Initiation_without_request_ec)

11. Initiating, other than request without eye contact (Initiation_without_request_wec)

12. Initiating, other than request with pointing (Initiation_without_request_pointing)

13. Typical eye contact

14. Atypical eye contact

15. Following

The frequency of each condition will be measured along with the overall number of interactions.

Full-Text: (412 Views)

Introduction

Joint attention (JA), also known as shared attention, is a fundamental social communication skill that emerges early in life. This skill involves one individual guiding another’s attention towards a specific object or event using various cues such as eye-gazing or pointing (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984). The ability to engage in JA typically develops in most children by the age of 18 months (Baron-Cohen et al., 1992). However, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often exhibit significant deficiencies in JA skills (Curcio, 1978; Dawson et al., 2004; Mundy et al., 1986; Sigman et al., 1999). ASD is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social communication and interaction, along with the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (APA, 2013).

Deficiencies in JA are among the earliest hallmarks of ASD and are a primary focus of early intervention programs. Children with ASD may show limited JA skills, such as poor eye contact, failure to orient to relevant stimuli, or difficulty following gestures and prompts from others. The absence of JA not only increases the likelihood of ASD (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997; Mundy, 2016; Swettenham et al., 1998) but also serves as an important early diagnostic marker (Baron-Cohen et al., 1992; Osterling & Dawson, 1994).

JA skills can be categorized into two primary types: (a) responding to JA (RJA) and (b) initiating JA (IJA) (Bruinsma et al., 2004; Meindl & Cannella-Malone, 2011; Mundy & Newell, 2007). RJA involves an individual’s response to a directional cue provided by another person towards a stimulus (Bruinsma et al., 2004). Conversely, IJA occurs when an individual gives a directional cue to guide another person’s attention towards a stimulus (Bruinsma et al., 2004). Furthermore, JA encompasses three attention components: orienting, sustaining, and shifting attention (Patten & Watson, 2011).

Research gap

Research has demonstrated a significant correlation between the absence of JA skills in early childhood and subsequent language limitations in children with ASD (Charman et al., 2003; Loveland & Landry, 1986). It is also believed that the lack of JA in response to social stimuli may contribute to the social communication challenges that are characteristic of ASD (Ebrahim, 2019; Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Kasari et al., 2006). As a result, various conventional intervention techniques have been proposed to address these deficits in JA skills (Ebrahim, 2019; Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Kasari et al., 2006). However, these interventions come with several limitations, including high costs, the requirement for lengthy and intensive therapy sessions with trained therapists, subjectivity, and limited adaptability to new settings (Chasson et al., 2007; Murza et al., 2016). In recent years, there has been a growing interest in technology-based interventions for individuals with ASD. While these interventions are not intended to replace conventional interventions, they can serve as valuable supplements and support systems.

Virtual reality (VR) is a promising technology-based intervention aimed at enhancing JA skills in ASD (Amaral et al., 2018; Amat et al., 2021; Cheng & Huang, 2012). VR offers sensory experiences within artificial environments created by computers (Savickaite et al., 2022). Its flexibility, controllability, replicability, and adjustable sensory stimulation make it particularly beneficial for ASD research (Strickland et al., 1996). Furthermore, VR allows for the individualization of intervention approaches and reinforcement strategies (Strickland et al., 1996). VR scenarios can be readily modified to depict a variety of scenes, overcoming the spatial and resource limitations often encountered in traditional therapeutic settings. Despite preliminary results indicating the potential of VR in developing JA skills in individuals with ASD, there is insufficient evidence regarding the effectiveness of VR applications (Amaral et al., 2018; Amat et al., 2021; Cheng & Huang, 2012; Yazdanian et al., 2023). Consequently, a VR platform featuring diverse scenarios has been designed and developed to provide JA skills training for school-aged children with autism (Yazdanian et al., 2023). This platform is intended for use by children under the supervision of therapists or parents, in conjunction with conventional treatments. A randomized clinical trial (RCT) is necessary to evaluate the potential of this VR platform in improving JA skills in natural environments.

Objectives

We hypothesize that children receiving the VR-based intervention will show improvements in JA and social communication behaviors, including eye contact, social response, and directed vocalization. The trial aims to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of the VR platform, alongside conventional interventions, on both RJA and IJA skills; (2) assess its impact on broader social-communication behaviors; and (3) compare outcomes between verbal and non-verbal participants.

Materials and Methods

Trial design

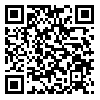

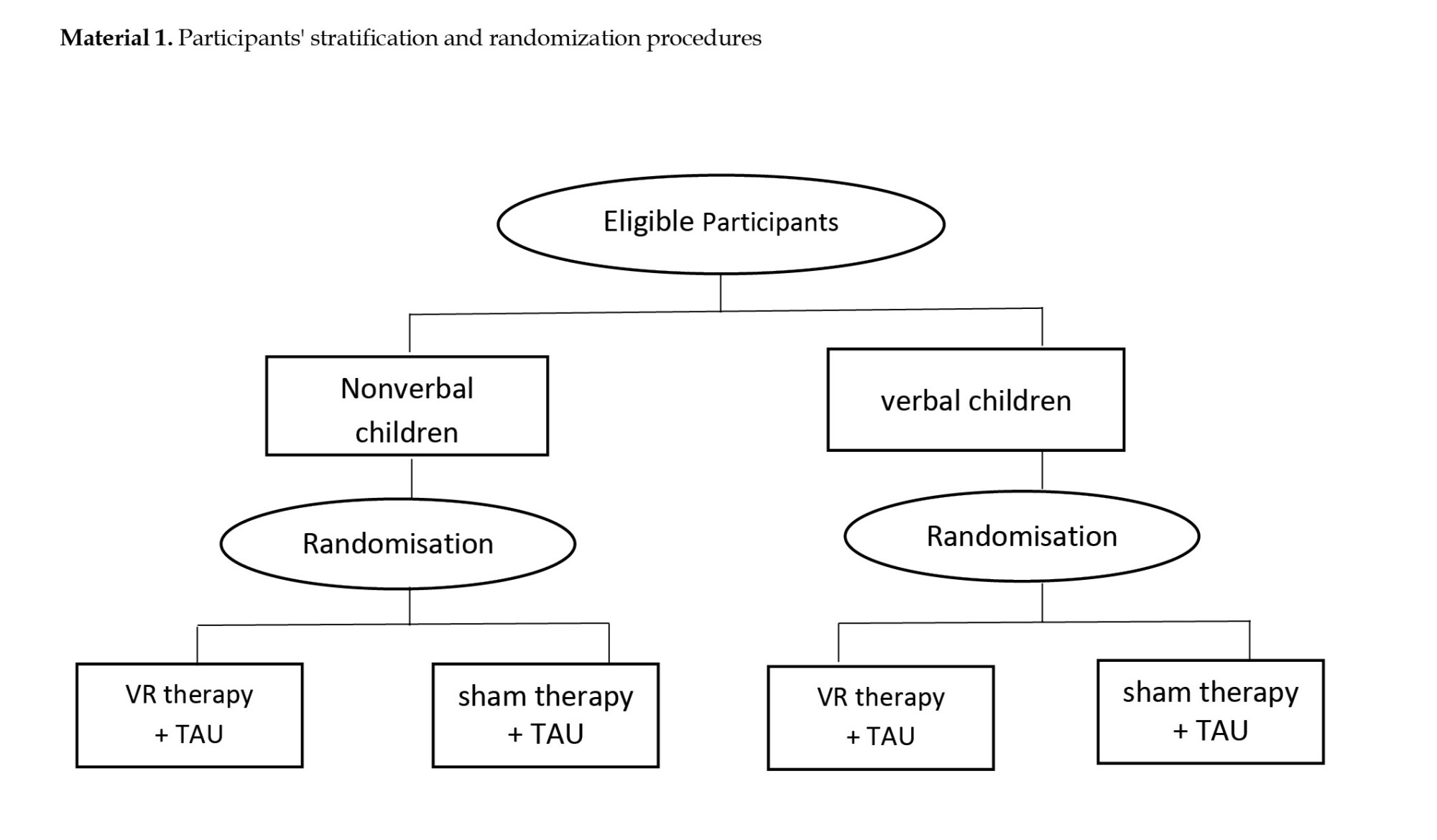

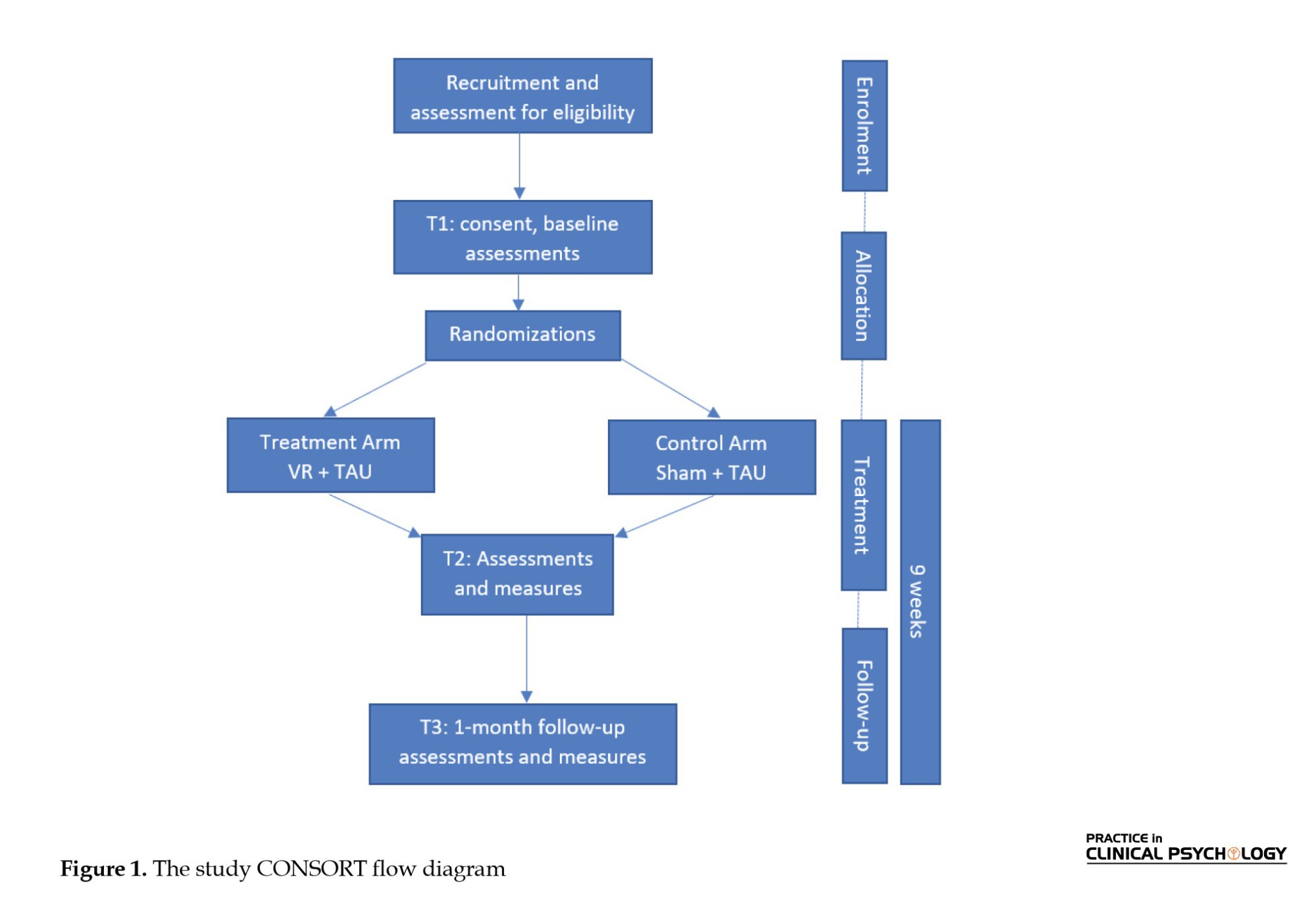

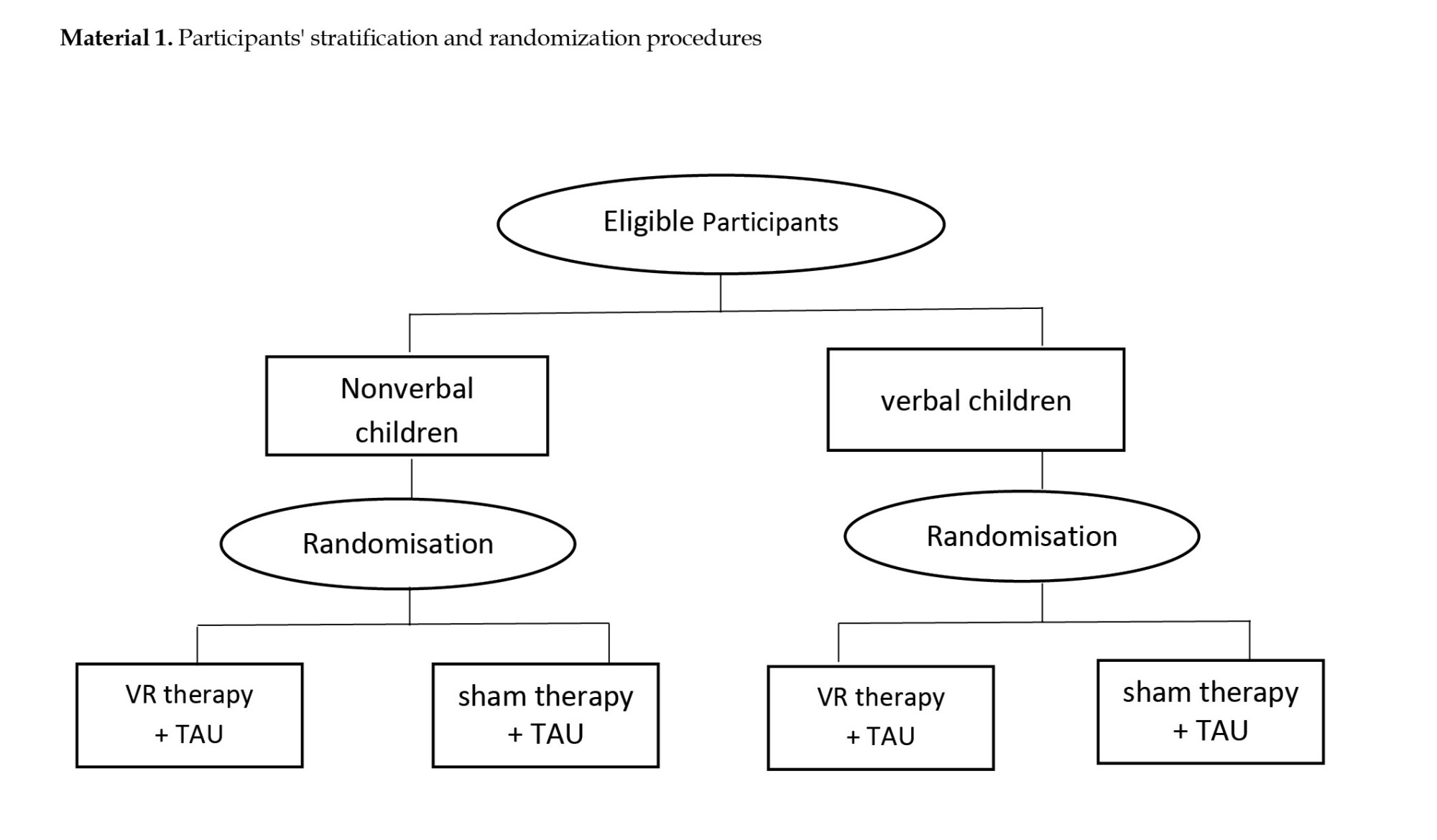

This study employs a 2 (training: VR therapy vs sham) × 2 (group: Verbal vs non-verbal) × 3 (time: Baseline, post-intervention, follow-up) mixed factorial design. The within-subject factor is time (three levels: T1 = baseline, T2 = post-intervention, T3 = one-month follow-up). The between-subject factors are training (two levels) and group (two levels). Accordingly, the study follows a two-arm, parallel-group, randomized, sham-controlled, single-blind trial with blinded outcome assessors. Participants are stratified by communication type (verbal vs non-verbal) in a 1:1 allocation ratio (Supplementary Material 1). The CONSORT (consolidated standards of reporting trials) flow diagram is provided in Figure 1, and the protocol adheres to the SPIRIT (standard protocol items: Recommendations for interventional trials) 2013 guidelines (Butcher et al., (2022).

Study setting

This multi-site trial will be conducted in special education and autism schools in Tehran City, Iran, enrolling children aged 6–12 years. This range was selected because the available participants are primary school students (preschool to seventh grade) attending autism-specific schools. Conducting the trial in schools enhances social validity (Reichow, 2011) and ensures that schedules are not disrupted. Children younger than 6 are excluded because of limited comprehension of instructions, while those older than twelve are excluded since JA skills are typically established by that age (Wetherby & Prizant, 2002). Conducting the study in schools also simplifies recruitment by enabling access to larger samples in one location and reducing logistical challenges for families.

Participants in both groups will receive the intervention in the speech and language therapy rooms of their schools. These rooms should be equipped with a table and an adjustable rotary office chair for the students’ use. The room’s temperature and ventilation should be appropriate, and any distracting elements should be removed from the student’s field of vision to create an optimal learning environment. Conducting the study in schools, where children are accustomed to learning new skills, enhances the intervention’s ecological validity. Furthermore, any information that teachers can share with the researcher regarding the participants’ communication system, abilities, special needs, sensory and time management difficulties, interests, and preferences will be invaluable for the success of the study.

Eligibility criteria

This study will include young children with ASD who will be recruited through the Exceptional Education Organization of Tehran, Iran. The eligibility criteria for the trial will consist of:

● Monolingual in Persian,

● Aged between 6 years, 0 months, to 11 years, 11 months at the start of the study,

● Clinically diagnosed with ASD, and

● Signed parents’ informed consent form (Supplementary Material 2) for inclusion in the study.

Being monolingual in Persian is important because the treatment is provided in Persian, and the VR scenarios’ language is also Persian. Although the child’s bilingualism, when she/he mastered the Persian language, did not cause a problem in the treatment process, this criterion is considered to ensure the understanding of the clinician’s and VR tasks’ instructions.

We include participants diagnosed with ASD based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) (APA, 2013), and the approval of the pediatrician’s psychiatrist. We chose people with autism because the JA problem is common among them, and it is one of the important criteria in diagnosing this disorder (Charman et al., 2003; Ebrahim, 2019; Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Kasari et al., 2006; Loveland & Landry, 1986). We aim to encompass all severity levels and consider comorbid conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or specific learning disorders.

It is worth noting that the evaluation of the cognitive abilities of autistic individuals seems to be challenging. The DSM-5 notes that intelligence quotient (IQ) tests may be unreliable in this group, as autism symptoms themselves can complicate assessment (APA, 2013). The manual also notes that IQ scores in individuals with ASD may be unstable, particularly in early childhood, meaning that a child’s score may vary widely over time (APA, 2013). However, to maintain homogeneity among participants, they are recruited from special schools for autism without limitations based on cognitive ability. Furthermore, participants can learn to interact with the VR system.

Finally, students who attend greater than 80% of the sessions will be included in the analyses.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

History of problems with VR games, history of seizures, epilepsy, migraines, vertigo, psychosis, or photophobia, obvious vision or hearing problem, severe stereotyped behaviors and hyperactivity, severe sensory or balance impairments, inability to understand and follow simple instructions, lack of proper psychomotor development, and Have received new medications like risperidone in the previous 6 months.

Children included in this study must exhibit a minimum language comprehension level at 24 months. The Newsha (Jafari & Asad-Malayeri, 2012) growth assessment questionnaire is employed for checking the level of language comprehension. Based on the expressive language level, participants can be classified into verbal (who use words for intentional communication) and nonverbal (who don’t use words for intentional communication). We incorporate inputs from parents or caregivers regarding the children’s use of words for communication, using the autism classification system of functioning: Social communication (ACSF: SC) tool (Mazahery et al., 2022). This procedure will provide a more thorough assessment of expressive language abilities.

An experienced specialist in pediatric speech therapy, with over 10 years of experience in the field of autism, will check the students’ eligibility criteria. She will also serve as a blind assessor in this study. Additionally, she will train a member of the research team for a minimum of three weeks to function as the second blind assessor.

Two teams, each consisting of an autism instructor and a research team member, will conduct the sessions in parallel. The autism instructors are required to have at least a master’s degree in a related field and a minimum of 2 years of experience in the domain of children’s autism.

Study interventions

Students in the treatment group will receive five weeks of JA interventions via VR tasks using a headset. In contrast, students in the control group at the same time will use the headset solely to watch a simple animation. Additionally, both groups will receive treatment as usual, consisting largely of one-to-one support in schools, including specialist units and integrated mainstream classes; some students receive low levels of speech and occupational therapy.

In this study, we will utilize a supervised VR system (Yazdanian et al., 2023). This system comprises two main components. The first component includes Shinecon VR 3D glasses and a compatible smartphone, which the students will wear. The second component is a supervisory panel that operates on a PC. This panel allows the therapist to control and monitor the VR sessions.

Before starting the intervention, both groups will undergo training to work with the system through two specially designed tutorial VR scenarios (Supplementary Material 3). These scenarios will also assess the student’s ability to interact with the system. All VR scenarios were reviewed and approved by a panel of nine ASD experts, including pediatric speech and occupational therapists with at least seven years of experience in autism (Yazdanian et al., 2023).

Before each session, instructors are required to complete a checklist of the instructions for the session. Additionally, instructors will fill out a questionnaire inquiring about the participant’s tolerance of the VR headset, their enjoyment of the VR session, any signs of adverse side effects, and their perceived value of the VR sessions.

Treatment group: VR therapy + treatment as usual (TAU)

This group of participants will receive treatment in the form of VR tasks designed to improve JA through VR headsets provided at the school. The sessions will take place three times a week, each lasting approximately 15 minutes, over a span of 5 weeks, totaling 15 sessions. Each session will encompass one VR scenario with a duration of roughly five minutes. If a participant shows interest, the instructor has the option to repeat the same scenario after a break of three to five minutes. A minimum interval of 48 hours is maintained between sessions; furthermore, the group receives TAU during the experiment.

Five VR scenarios have been meticulously designed to target the three primary components of JA: Orienting attention, sustaining attention, and shifting attention (Supplementary Material 3). These scenarios unfold on ‘Mina’s Farm,’ a virtual farm inhabited by four animals: A cat, a dog, a cow, and a horse. These animals are incorporated into the scenarios to engage the students’ attention as needed.

In the first scenario, the objective is to orient attention. In this scenario, the child’s task is to identify the direction of the sound produced by each animal. By using auditory cues, they should recognize the source of the sound and focus on the target item. The second scenario, which is a response to the JA scenario, aims to target both orienting and shifting attention. Here, the child must demonstrate an understanding of Mina’s hand and or head cues. Their objective is to locate the target item (which could be a cat, dog, cow, or horse) by following the cues provided by Mina and fixating their gaze on the item. In the third scenario, the focus shifts to sustaining attention. The child’s task is to track the path of interactive characters visually. The fourth and fifth scenarios aim to initiate JA and target all components. In these scenarios, the child needs to capture Mina’s attention by drawing her toward an intriguing situation. This situation involves the interactive character spinning around, which contrasts with previous scenarios. Once the child fixes their gaze on the character, it suddenly performs a peculiar movement (for example, a cat jump). In the fourth scenario, Mina says, ‘What happened?’, while in the fifth scenario, she remains silent. The child is expected to shift their gaze toward Mina and maintain a visual fixation on her to capture her attention regarding the situation.

The expert panel thoroughly evaluated the face and content validity of these developed scenarios (Yazdanian et al., 2023). The scenarios successfully met the standards set by this panel. There is a list of changes in the scenarios based on the panel comments at the end of Supplementary Material 3.

Scenarios are executed sequentially every week. If participants are unable to complete the first scenario by the end of week 1, they will revert to the tutorial scenarios. Similarly, if they fail to complete the second scenario by the end of week 2, they will be directed back to the first scenario, and this process will continue until week 5.

Control group: Sham therapy + TAU

Participants in this group are invited to watch a simple animation in a virtual cinema setting at school, using a VR headset. In this setting, the animation is projected onto a virtual screen, and participants can explore different parts of the virtual theater by moving their heads, allowing them to observe the seats and surroundings. This design is intended to evoke a sense of presence, a fundamental element of VR technology, thereby ensuring a comparable immersive experience between the two groups. While the control group’s VR exposure lacked interactivity, it still provided sensorimotor engagement similar to the intervention group’s VR experience.

Similar to the treatment group, sessions will be held three times a week over 5 weeks, amounting to a total of 15 sessions. A minimum gap of 48 hours will be ensured between each session. In addition to this, the group will continue to receive treatment as usual. The selected animation for viewing is episodes from the 2D animation series ‘Pablo’ (Morris et al., 2020), with each episode lasting less than five minutes. This animation is not associated with the aims of the intervention software (i.e. JA and social communication skills). It is selected to blind the study for participants and their families and to control for the amount of time spent using VR headsets during the study, as well as social interactions with the experimenters. The chosen animation does not relate to JA or social-communication skills. It was selected to preserve participant blinding and to control for headset exposure time and interaction with experimenters.

Assessment tools and outcomes

A demographic questionnaire will be used to collect basic data such as age, gender, and parents’ educational background. This information will be supplemented with related information from student health records, including a history of drug usage and level of autism. The questionnaire will also gather information about students’ favorite games, their interest in computer games, and their experience with VR. Furthermore, it will be administered to determine whether the child uses intentional language for communication (classified as the verbal group) or not (classified as the nonverbal group).

The Newsha growth assessment questionnaire is employed at the baseline to ensure the child’s understanding of basic commands. This tool specifically evaluates language comprehension, aiming for a minimum developmental level equivalent to 24 months.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this study will be the assessment of JA skills, specifically RJA and IJA. Regrettably, previous studies on the enhancement of JA skills using VR-based intervention have not reached a consensus on the use of JA measures (Yazdanian et al., 2023). In this study, we will compile a behavioral sample of participants, drawing inspiration from the measure prepared by Ravindran et al. (2019). This measure, designed based on the communication and symbolic behavior scale (CSBS) (Wetherby & Prizant, 2002), aims to assess JA skills within a broader framework of social interaction. The goal is to evaluate gestural interaction skills (including the presence or absence of eye contact and pointing) under optimal conditions. This behavioral sample emphasizes key behaviors in JA skills, such as responding to interactions (with or without eye contact, with pointing) and initiating interactions (with or without eye contact, with pointing). These interactions could be intended for making requests or for other purposes. The measure can be administered swiftly, incorporates play-based activities suitable for school-aged children, and focuses on the key JA behaviors targeted in our study. Detailed information about the measure can be found in Butcher et al's study (Butcher et al., 2022).

Furthermore, the childhood JA rating scale (C-JARS) (Birkeneder et al., 2023) will be employed to evaluate the JA skills of participants. This scale is in the form of a parent questionnaire and measures three types of behaviors associated with JA and the spontaneous sharing of experience. The first measure involves observing non-verbal behaviors such as following and directing gaze, which are fundamental to preschool children and are key indicators of JA during childhood. The second measure pertains to the spontaneous expressions of children, where they share or reveal their positive experiences with others, enhancing the sense of connection between social partners. The third measure evaluates the inclination of children to participate in joint action, including collaborative and cooperative activities. This evaluation is crucial as JA and joint action share similar mental and social bonding mechanisms. The parents will implement the C-JARS under the guidance of a member of the research team.

In addition to the two measures previously mentioned, we have designed and developed a cross-validation tool within a virtual environment (Supplementary Material 3). This tool comprises 6 VR tasks, collectively referred to as JA assessment tasks (JAST). These tasks take place in a virtual living room and involve interaction with a boy avatar named Sina. It is important to note that these scenarios are entirely distinct from the VR scenarios used for treatment. To ensure consistency in evaluating JA skills, all 6 assessment scenarios are used at each evaluation phase (T1, T2, and T3). Both groups, including the control group, utilize the VR assessment tool to ensure consistency in measuring JA skills across participants. The primary objective of JAST is to evaluate the JA skills targeted in our intervention, both before and after the experiment. We have also thoroughly assessed the face and content validity of JAST, which successfully passed an expert panel review.

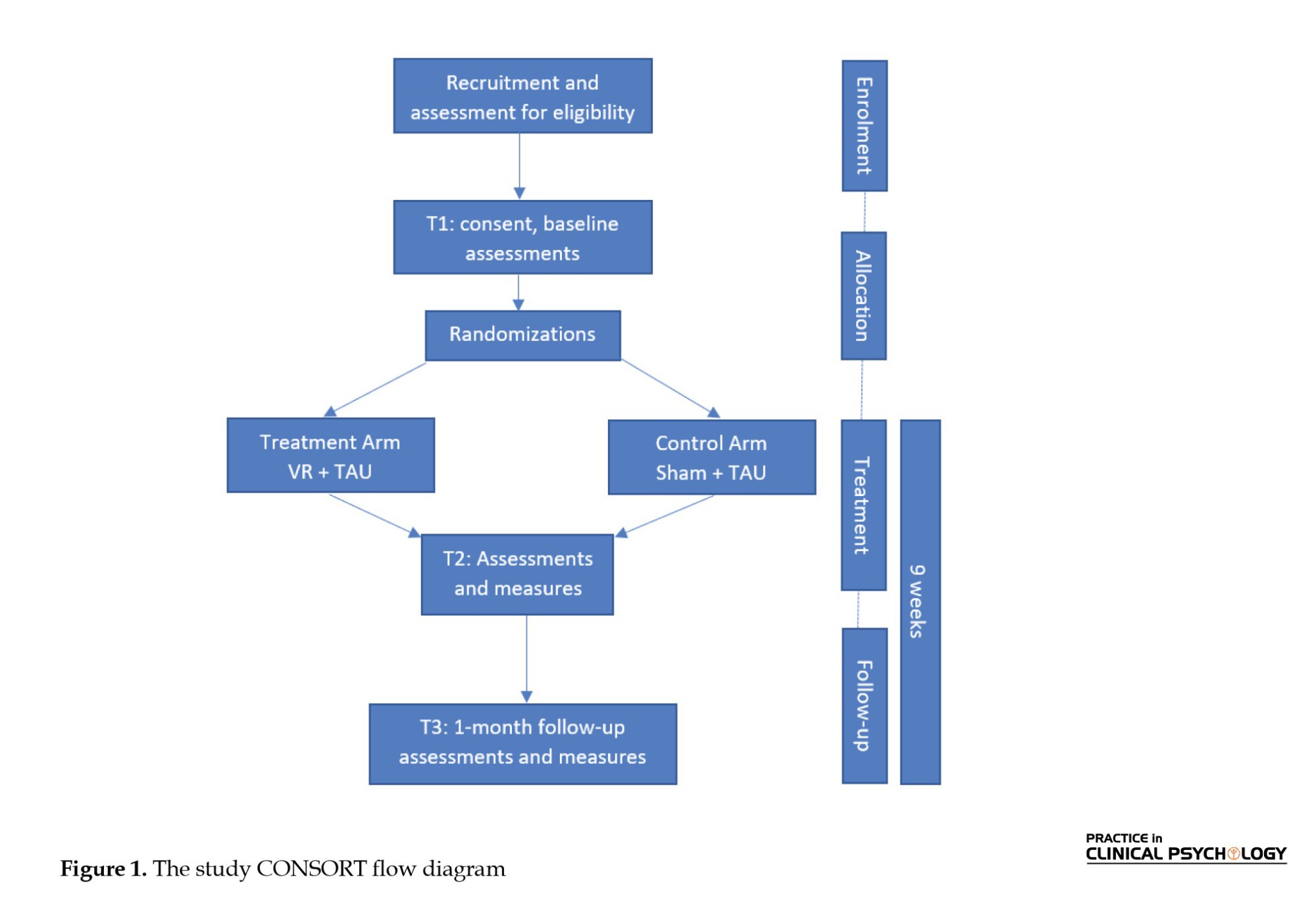

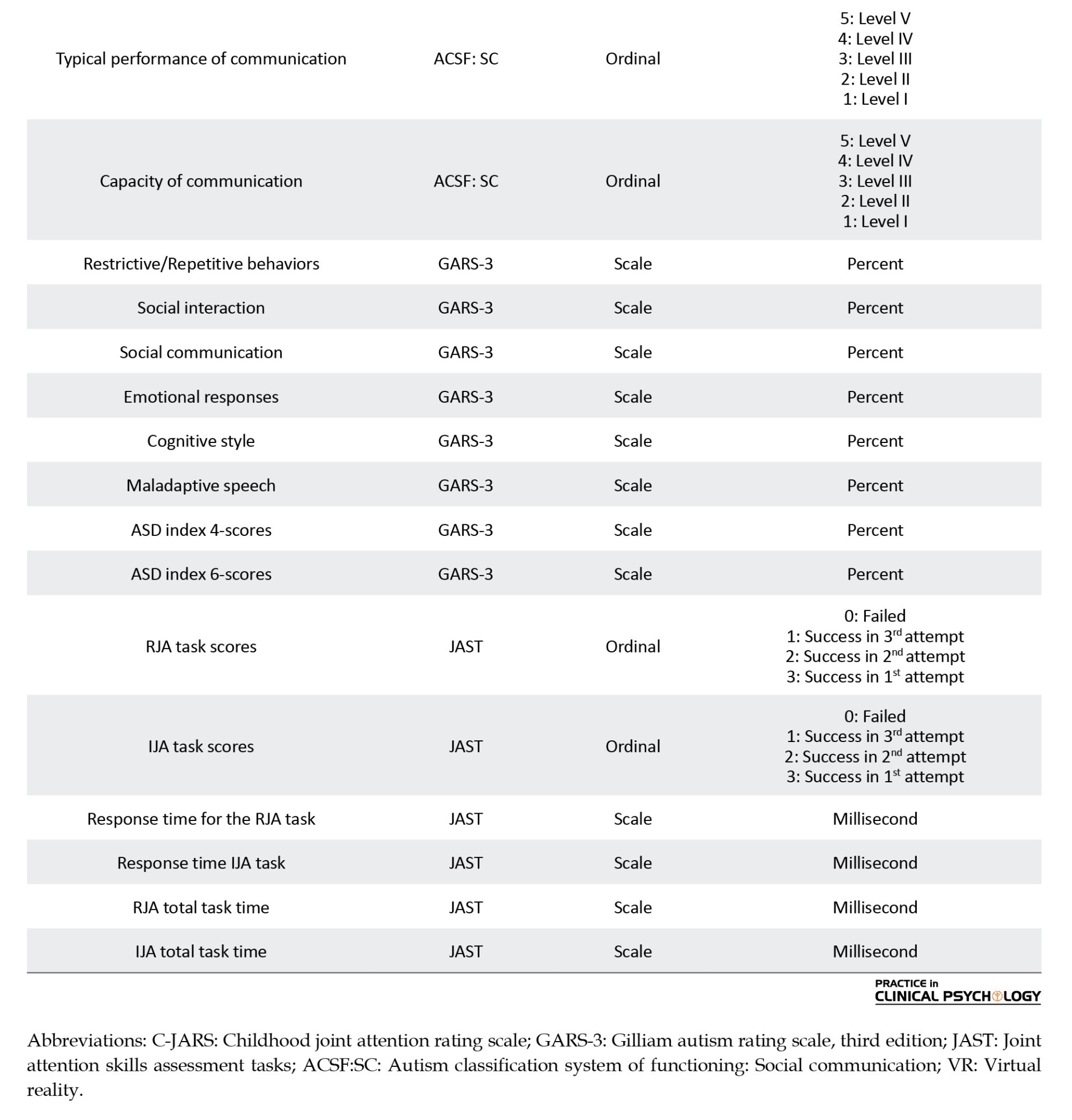

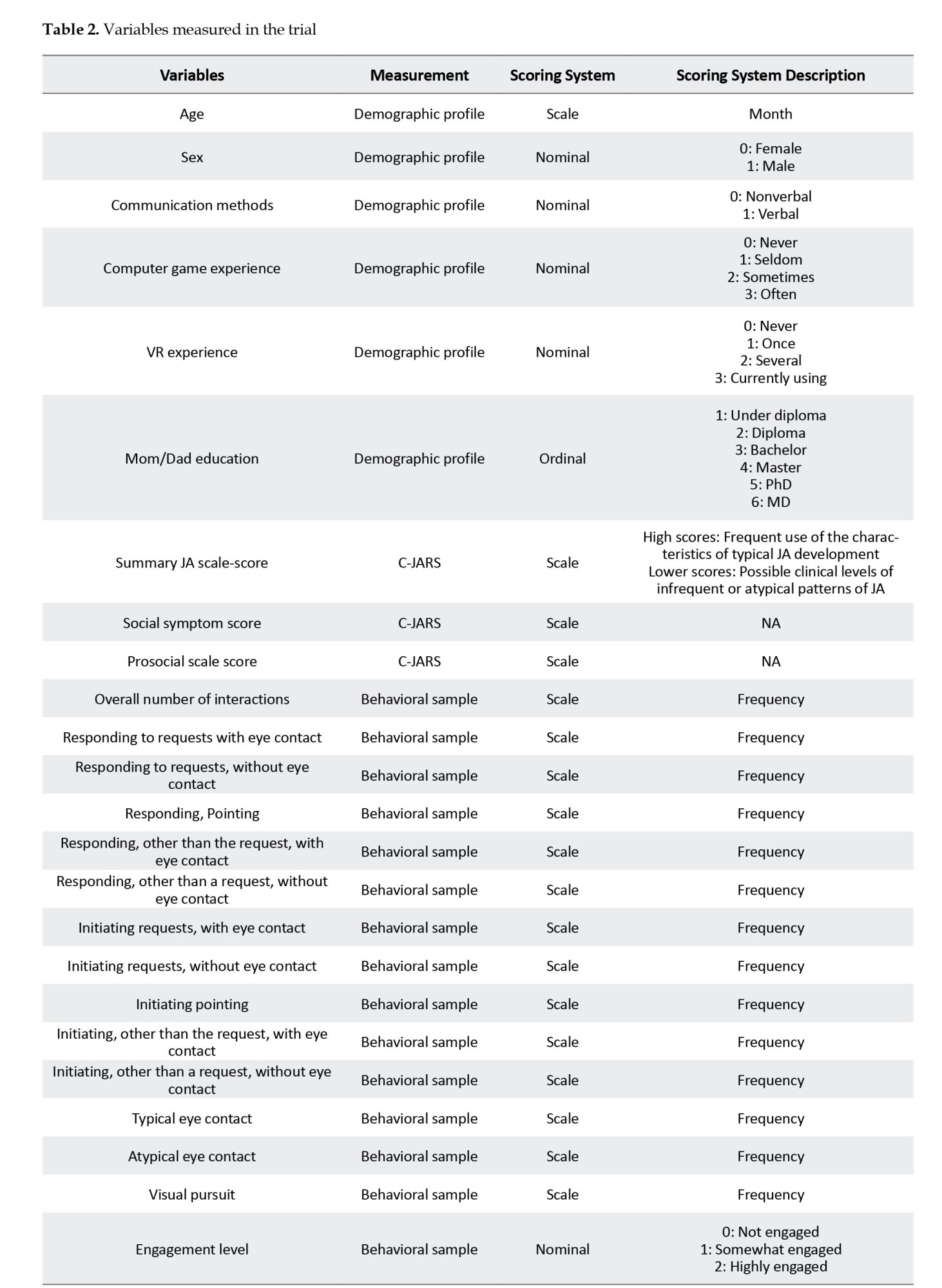

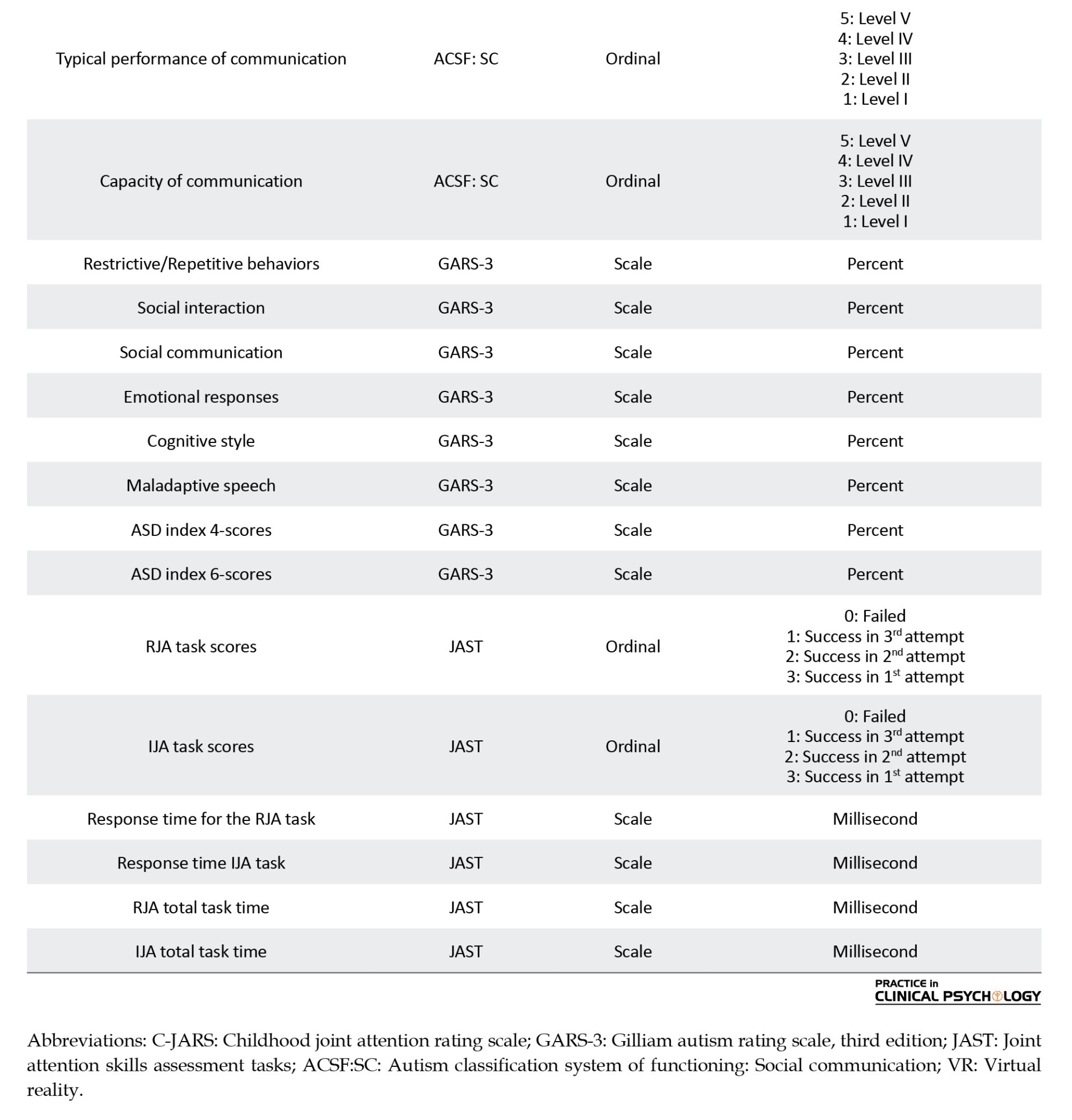

For C-JARS, we follow the standardized administration procedures outlined in its manual, as provided to us by Birkeneder et al. (2023). The detailed procedure for behavioral sampling is included in Supplementary Material 4, while the VR-based assessment (JAST) is described in Table 2. Additionally, Table 1 illustrates the timing of assessments across different study phases. JA skills are evaluated using these tools at three time points: baseline (T1, before the intervention), post-intervention (T2, at the conclusion of the study), and follow-up (T3, one month after study completion).

Secondary outcome

Social communication skills serve as the secondary outcome of our study. To facilitate this, we have selected the ACSF: SC (Mazahery et al., 2022) to categorize participants at various stages of the study. The ACSF: SC evaluates the typical performance and communication capacity of individuals with autism. This descriptive system classifies social communication skills into five levels, with a child at level V possessing the least skill and a child at level I exhibiting the highest skill. It is important to note that the ACSF: SC is not a diagnostic tool, test, or checklist. Instead, it provides a framework for those familiar with a child to discuss their social communication skills, focusing on their best performance (capacity) and their regular behavior (typical performance). By defining and categorizing social communication skills, the ACSF: SC facilitates a common language for parents and experts interacting with both verbal and nonverbal children with ASD (Di Rezze et al., 2016; Mazahery et al., 2022). For this study, we will be utilizing the Persian version of this questionnaire (Mazahery et al., 2022).

Participants’ severity of autism will be evaluated using the Gilliam autism rating scale, third edition (GARS-3) (Gilliam, 2014), which is comprised of 56 distinct items that describe the typical behaviors of individuals with autism. These items are categorized into six subscales: Restrictive/repetitive behaviors, social interaction, social communication, emotional responses, cognitive style, and maladaptive speech (the last two subscales are for the verbal group only). While all subscales will be assessed, our primary focus will be on the subscales of social interaction and social communication.

For GARS-3 and ACSF: SC, we follow the standardized administration procedures outlined in their respective manuals (Gilliam, 2014; Mazahery et al., 2022). Parents, assisted by a research team member, will complete these measures at three time points: Baseline (T1), post-intervention (T2), and one-month follow-up (T3) (Table 1).

.jpg)

Variables

Table 2 shows a list of variables that will be measured i the trial.

Participant timeline

Table 1 shows the schematic diagram for the schedule of enrolment, interventions, assessments, and visits for participants.

Sample size

The sample size for this study is determined based on an effect size of 0.6, which reflects a moderate effect size likely to be of clinical relevance for interventions aimed at improving JA skills in children with ASD. This effect size is chosen based on its meaningful implications for the quality of social communication skills, as observed in clinical practice. Assuming a two-tailed test with α=0.05 and a power of 0.8, a sample size of 17 participants per group is required for statistical significance. Accounting for a 20% attrition rate, we propose enrolling a total of 40 participants, with 20 in each group. These calculations were performed using the G*Power software, version 3.1.

Recruitment

To ensure sufficient enrolment of participants, three members of the research team will visit special education and autism schools. There are eleven such schools in Tehran. The recruitment of participants is scheduled to begin in December 2023. The team will continue to visit schools until the target sample size is reached, at which point no further schools will be visited.

Allocation: Sequence generation, allocation concealment mechanism, and implementation

The blocked randomization method is utilized to divide participants into distinct groups (Friedman et al., 2015). This allocation procedure encompasses several stages. Initially, a random sequence with blocks of four is generated using an online software application (Sealed_Envelope Ltd, 2024). The sequence is then stratified based on the participants’ communication method, whether verbal or nonverbal. To maintain the secrecy of the random allocation, we use sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes in a random sequence. In line with the sample size, we prepare 40 envelopes, each containing aluminum foil to prevent “hot lighting.” Each element in the random sequence is recorded on a card and placed inside a corresponding numbered envelope. Following this, the envelopes are sealed and stored in boxes. As participants register, an envelope is opened in the sequence of eligible participant entries, revealing the group assignment for each participant. In this approach, the expert verifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria operates independently from the individual conducting the allocation process. This condition ensures an unbiased and transparent process.

Blinding

This study will be conducted in a single-blind manner. Participants and their families remain unaware of group allocation post-randomization, and all outcome assessors and the statistician are blinded during baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up assessments. Autism instructors delivering the intervention cannot be blinded, as they must administer either the VR-based therapy or the sham condition. The primary researcher is responsible for securing permissions, recruitment, training therapists, and overseeing intervention procedures, while research assistants support randomization and maintain assessor blinding.

Data collection methods

As noted earlier, the behavioral sample, C-JARS, JAST, ACSF:SC, and GARS-3 will be administered at three points: Baseline (T1), post-intervention (T2), and one-month follow-up (T3). To ensure participant retention, we will meticulously plan our data collection schedule to accommodate the schools’ convenience as much as possible.

Before each VR session, participants are required to fill out a questionnaire that includes both written and visual components. This questionnaire seeks information about the participant’s general health status, balance, sleep patterns, and interest in participating in the sessions. Following each session, participants will again complete a similar questionnaire that probes their level of alertness, any discomfort in the eyes, clarity of vision, presence of headaches or stomach aches, balance, and their enjoyment of using the VR glasses. In addition, before initiating each session, the therapist will complete a checklist pertaining to the instructions for starting VR sessions. This procedure is done to ensure that all steps are accurately implemented. The therapist will also fill out a questionnaire regarding the participant’s tolerance of the headset, perceived enjoyment of the VR session, any observed negative side effects, and perceived value of the VR sessions for the participant. The questions addressing tolerance, enjoyment, negative side effects, and value of the VR experience will offer “Yes” and “No” as answer choices. The final question on the therapist survey solicits qualitative feedback on the participant’s experience and any additional information related to the VR session.

The VR platform records the scores of the participants in each session. The data gathered throughout the study will be subjected to daily review by the study staff to investigate the safety and acceptance of the headset and VR experience among the study participants.

Data management

The trial will follow the CONSORT guidelines. Missing data will be imputed based on its cause, such as absenteeism. Raw data will be recorded in Excel using coded identifiers, with separate spreadsheets for the two groups. Research assistants will cross-verify and recheck entries, and any discrepancies will be reviewed and corrected. We assessed the fidelity of the intervention, which means how well it followed the protocol, twice during the study using a checklist. As per the guidelines for good practice in the conduct of clinical trials with human participants in South Africa, the data are retained for 15 years following the formal discontinuation of the trial (Department of Health, 2006). The principal investigator will oversee the secure storage and eventual disposal of the data.

Statistical methods

The analysis will adhere to the intention-to-treat principle and be reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines (Schulz et al., 2010). All statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS software, version 25. Quantitative data will be presented using Mean±SD, while qualitative data will be described using frequencies and percentiles. We will assess the homogeneity of treatment and control groups on demographic characteristics. For quantitative data, we will use independent-sample t-tests when distributions are normal and Mann-Whitney U tests when they are not. The Pearson chi-squared test will be employed for qualitative data. Baseline variables will be summarized appropriately for each group. Any imbalances between groups for key baseline variables will necessitate further adjusted analyses. For the primary outcome of JA, scores will be compared between the two groups using an independent samples t-test if they are normally distributed or a Mann-Whitney U test if they are skewed. The Sidak correction procedure will be applied to reduce the probability of a Type I error. The Shapiro-Wilk test will be used to verify normality. The results will be reported as an estimate of the difference between groups, a 95% confidence interval, and an associated P. All P will be reported to two decimal places, with those less than 0.05 reported as P<0.05. A similar analysis will be conducted to address the secondary outcome objective. The study will be performed by our team’s statistics specialist (Mohsen Vahedid).

Patient and public involvement

Participants and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Data monitoring and auditing

The data will be meticulously collected, scrutinized, tracked, and safeguarded by a dedicated team of research assistants, working in collaboration with a statistician. This collective will constitute the Data Monitoring Committee. It is important to note that the research assistants and the statistician involved in this process have declared no competing interests.

Harms

No acute side effects were observed in previous VR studies. A recent review (Kaimara et al., 2022) suggests that VR interventions could impact children’s physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development. In terms of physical effects, concerns have been raised about short-term issues such as cybersickness, the prevalence of visual symptoms, sleep disorders, obesity, or poor nutritional habits, which typically result from excessive use of screens and head-mounted devices (HMDs). As for cognitive development, only positive or neutral effects have been noted. The most significant concern lies within the psychosocial domain (Kaimara et al., 2022). However, the adverse effects of VR on children are primarily associated with unrestricted and unsupervised use. To address these concerns, we plan to implement restricted (approximately 5 minutes per session) and supervised use of the VR headset. Furthermore, an expert panel has endorsed the suitability of VE scenarios for children with autism.

Participants will be monitored before, during, and after each VR session for any signs of discomfort (e.g. visual fatigue, headache, nausea). The therapist will document all adverse events. “If a serious adverse event (SAE) is suspected, the session will be stopped immediately and the child referred for medical evaluation. The event will then be reported to the Ethics Commission within 24 hours, in accordance with institutional guidelines. An independent monitoring committee will oversee all reports to ensure participant safety.

One potential harm to this study is that the control group does not receive any instructional assistance in addition to the treatment-as-usual. To mitigate this issue, all participants have been informed that, upon successful results, they will have the opportunity to benefit from free-of-charge VR therapy sessions after the intervention concludes.

Research assistant teams will systematically collect data during each session, and any observed side effects will be documented by the therapist post-session.

Consent or assent

Before participation, a research assistant will provide parents or guardians with a comprehensive explanation of the study’s objectives and procedures, both verbally and in written form via an introductory booklet for VR. The principles of confidentiality, voluntariness, and the freedom to withdraw from the study at any stage will be clearly communicated. Informed consent will be obtained from parents or guardians by a research assistant, and assent will be sought from the children.

Confidentiality

The confidentiality of study participants’ names and personal information will be stringently upheld. All study records, including case report forms, safety reports, and correspondence, will identify the patient solely by their initials and the assigned study identification number. The investigator will maintain a confidential patient identification list throughout the study. Access to confidential information, such as source documents and patient records, is strictly limited to those involved in direct patient management and those monitoring the conduct of the study. The patient’s name will not appear in any public report related to the study.

Access to data

Access to the data will be exclusively limited to the immediate research team. All samples and questionnaire data will undergo a process of de-identification and coding before analysis.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Dissemination policy

The findings of the study will be disseminated to the scientific community through research articles and conference presentations. Additionally, a summary of the key results will be made accessible to study participants and the general public via newspaper articles.

Results

In October 2023, the recruitment process commenced, and data were collected from 18 participants by December 2023. Data collection is expected to conclude in September 2024, unless additional data is needed and recruitment resumes. The analysis phase is projected to be completed by December 2024. The study results will be published in international and national journals and presented at conferences no earlier than early 2026.