Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

PCP 2025, 13(4): 347-354 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghafari Z, Hoseinzadeh M, Hashemipour M. Compassion-focused Therapy Effectively Reduces Self-criticism, Negative Thoughts, and Enhances Forgiveness in Women Post-marital infidelity. PCP 2025; 13 (4) :347-354

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1043-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1043-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,hoseinzadehmd@gmail.com

3- Department of Psychology, And.C., Islamic Azad University, Andimeshk, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, And.C., Islamic Azad University, Andimeshk, Iran.

Keywords: Compassion-focused therapy (CFT), Forgiveness, Self-criticism, Negative thoughts, Marital infidelity

Full-Text [PDF 595 kb]

(857 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (667 Views)

Full-Text: (371 Views)

Introduction

Marital infidelity is a profoundly damaging experience, often described as a betrayal of trust and significant life trauma (Rokach & Chan, 2023). For women, the discovery of a partner’s infidelity can lead to a cascade of debilitating psychological consequences that severely compromise their mental and emotional well-being (Karimi et al., 2023). Research indicates that the betrayed partner frequently experiences symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, emotional dysregulation, and hypervigilance (Lonergan et al., 2021; Jules et al., 2023). Beyond the immediate shock, women in this situation are highly susceptible to chronic stress, anxiety, and depression, which can persist for years (Axinn et al., 2020). This emotional turmoil is often compounded by a dramatic loss of self-esteem, as they may internalize the betrayal and engage in self-blame, leading them to question their worthiness and adequacy. The rupture of a foundational relationship can also cause lasting trust issues and difficulty forming new attachments, underscoring the deep and long-term impact of this specific form of relational trauma (Atapour et al., 2021).

The psychological impact of infidelity is intricately tied to forgiveness, self-criticism, and repetitive negative thoughts, which interact to exacerbate distress. Forgiveness involves a deliberate process of releasing resentment and fostering emotional peace, often hindered by self-critical thoughts and rumination that perpetuate feelings of inadequacy (Pandey et al., 2023). Self-criticism, characterized by harsh self-judgment, amplifies negative emotions, while repetitive negative thoughts, or rumination, trap individuals in cycles of distress, reinforcing helplessness (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2019; Shrout & Weigel, 2020). Self-compassion, as a mediator, can mitigate these effects by fostering self-kindness and reducing self-blame, thereby facilitating forgiveness and emotional recovery (Pandey et al., 2021).

Given the intense self-criticism and shame often experienced by women after infidelity, compassion-focused therapy (CFT) has emerged as a highly relevant and promising intervention (Karami et al., 2024). Developed by Paul Gilbert, CFT is a therapeutic approach that helps individuals regulate their emotions by cultivating self-compassion and kindness (Gilbert, 2009). It operates on the principle that many psychological difficulties, particularly those rooted in shame and self-criticism, stem from an overactive “threat” emotional system and an underdeveloped “soothing” system (Mousavi et al., 2023a). CFT aims to activate the soothing system, through techniques, such as compassionate imagery, soothing rhythm breathing, and compassionate letter writing, fostering a sense of emotional safety and self-acceptance (Gilbert, 2014; Irons & Beaumont, 2017). This approach has demonstrated efficacy across diverse populations, including those with trauma-related distress, suggesting its applicability to emotional challenges related to infidelity (Leaviss & Uttley, 2015).

Previous studies have predominantly explored interventions, such as emotionally focused therapy (EFT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for couples navigating infidelity (Asvadi et al., 2022; Bodenmann et al., 2020). Although these approaches have proven effective in enhancing forgiveness and closeness, there is a significant lack of research on the use of CFT to address the individual trauma experienced by the betrayed partner. CFT’s focus on self-compassion and shame reduction addresses a critical gap in individual-focused interventions for infidelity-related distress, particularly in fostering forgiveness through self-kindness and reducing rumination (Craig et al., 2020; Pandey et al., 2021). This study aimed to examine the efficacy of CFT in improving forgiveness and reducing self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts among women affected by marital infidelity in a culturally specific context.

Materials and Methods

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design, incorporating pre-test and post-test assessments with a control group, to evaluate the efficacy of CFT. The study population included all married women who faced marital infidelity and sought counseling services in Ahvaz City, Iran, between January and March 2025. A sample of 30 eligible women was selected using convenience sampling, and the sample size was determined using G*Power software. The inclusion criteria required participants to be women aged 25–45, currently married, with a history of marital infidelity within the past six months, and willing to provide informed consent. The exclusion criteria encompassed severe psychiatric conditions (e.g. psychosis), substance abuse, and participation in other concurrent psychological treatments. Thirty participants were randomly and evenly divided into an experimental (n=15) and a control group (n=15). This study adhered to the university’s ethical guidelines, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Procedure

Following participant selection and group allocation, both the experimental and control groups completed pre-test assessments using the forgiveness scale (FS), the self-criticism levels scale, and the repetitive thoughts questionnaire (RTQ). The experimental group participated in eight 90-minute CFT sessions held twice a week. The control group was placed on a waiting list and did not receive any intervention during the study period. After the intervention, both groups completed the same questionnaires as post-tests. The pre-test and post-test data were collected and prepared for statistical analysis.

Instruments

FS: The FS, developed by Rye et al. (2001), is a self-report tool designed to assess an individual’s inclination to forgive others. It comprises 15 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 15 to 105. Higher scores reflect a greater propensity for forgiveness. The FS has shown good internal consistency, with Rezaei et al. (2020) reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.74. In this study, the scale exhibited excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.89.

Levels of self-criticism scale (LSCS): The levels of LSCS, developed by Thompson and Zuroff (2004), is a 22-item self-report measure that evaluates two aspects of self-criticism: self-rejection and fear of rejection by others. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (very true for me), with total scores ranging from 22 to 110. Higher scores indicate increased self-criticism. The LSCS has demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Khanjani et al. (2025) reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.87. In the current study, the scale showed high reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.92.

RTQ: The RTQ, developed by Mahoney et al. (2012), is a 10-item tool designed to measure the frequency of repetitive negative thoughts. Responses are provided on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 4 (almost always), with total scores ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores signify a greater tendency to ruminate. The RTQ has demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 reported by Hasani et al. (2022). In this study, the RTQ demonstrated robust internal reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.85.

Intervention

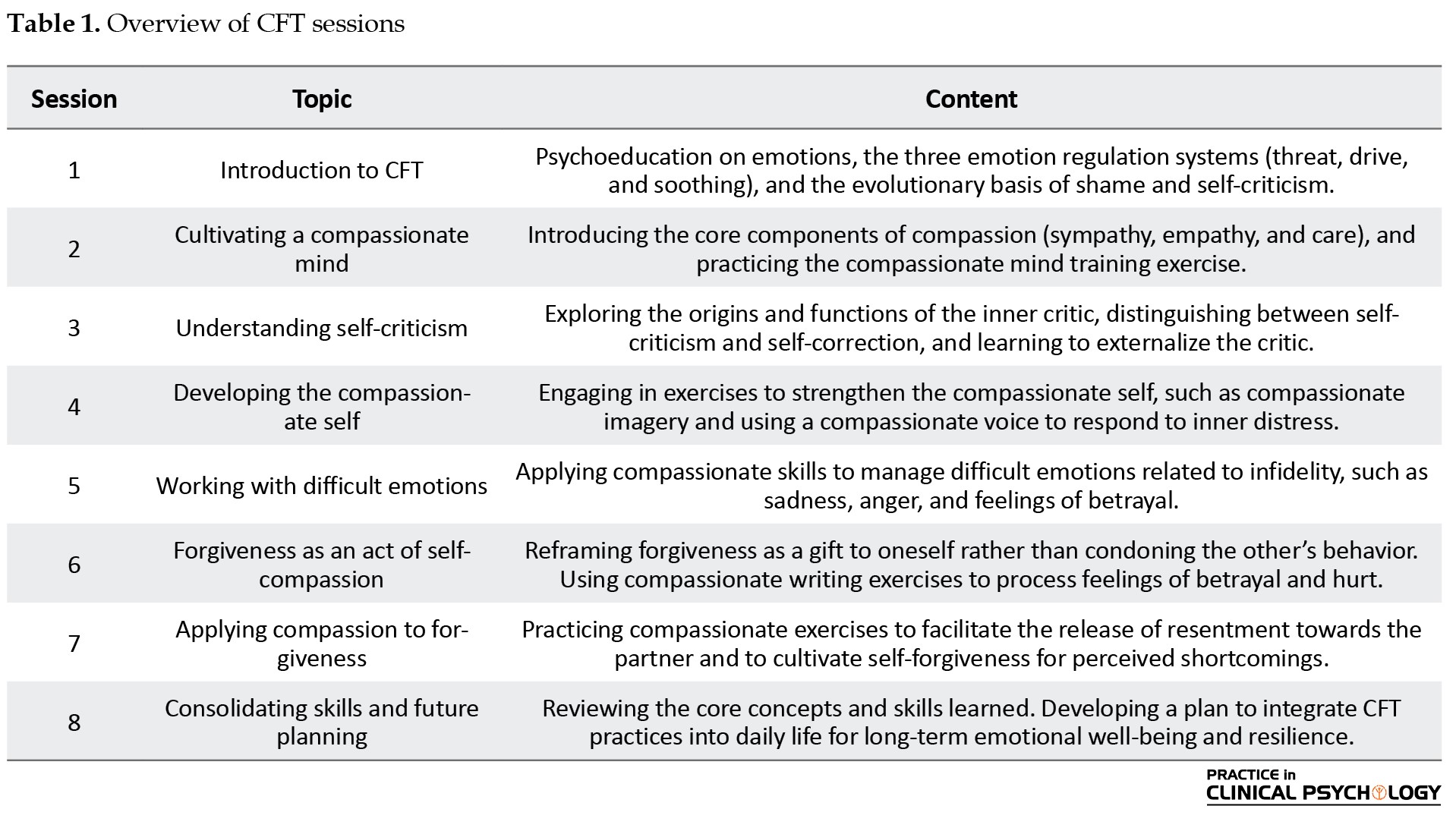

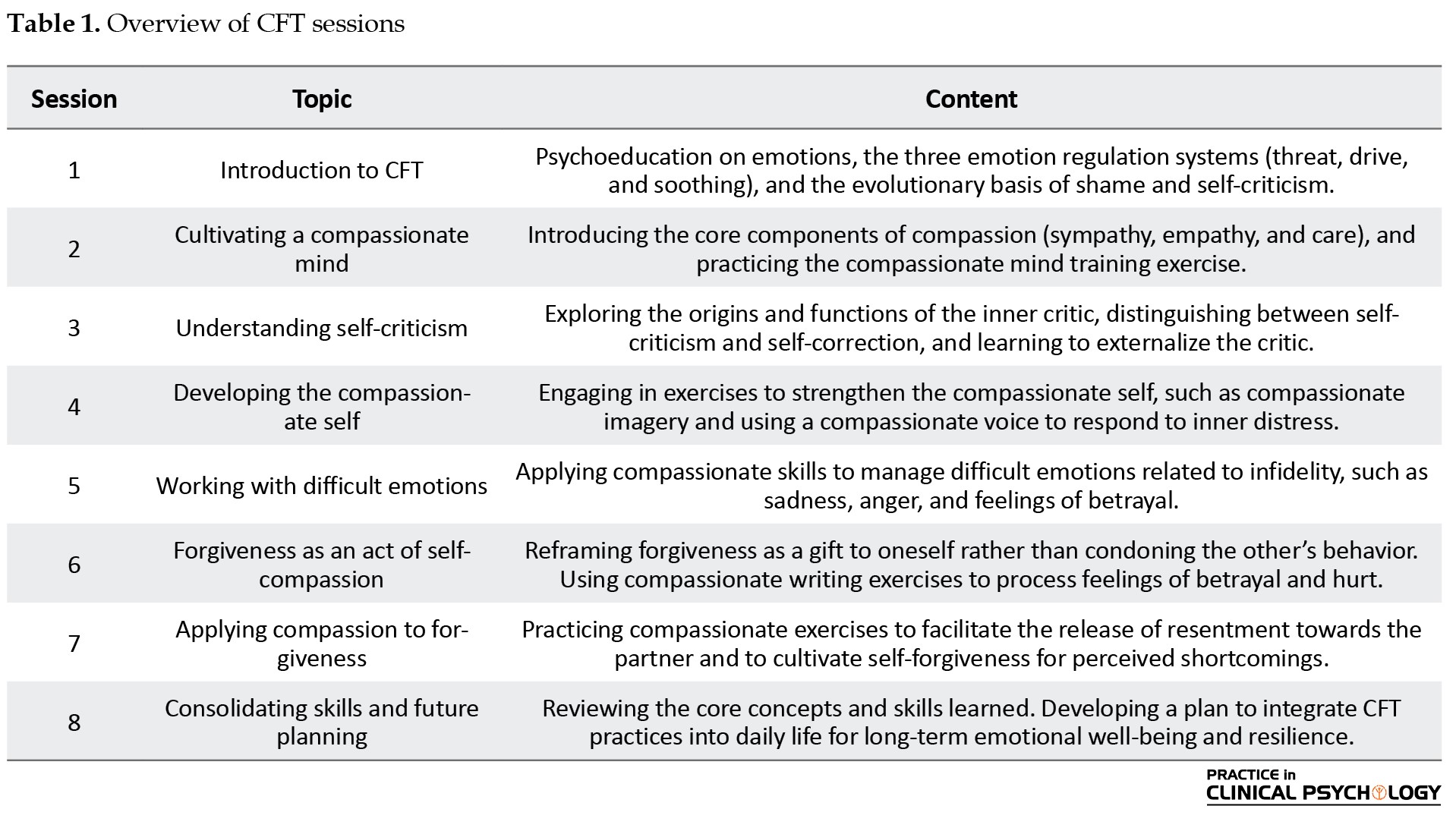

The CFT intervention for the experimental group was delivered over eight 90-minute sessions. The program was structured to guide participants through the core principles of CFT, including psychoeducation on the three emotion regulation systems, cultivating a compassionate mind, and applying compassionate exercises to reduce self-criticism and promote self-forgiveness. Table 1 presents the session-by-session content.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were computed for all variables. To assess the intervention’s effectiveness, a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed. ANCOVA assumptions, including normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P>0.05), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P>0.05), and homogeneity of regression slopes (P>0.05 for interaction between covariate and group), were met. A significance threshold of P<0.05 was established for all statistical analyses.

Results

The study included 30 women impacted by marital infidelity, evenly divided into an experimental group (n=15) and a control group (n=15). The experimental group had a Mean±SD age of 36.58±4.22 years, while the control group’s Mean±SD age was 35.83±3.95 years. The Mean±SD marriage duration was 11.24±2.86 years for the experimental group and 10.95±3.16 years for the control group.

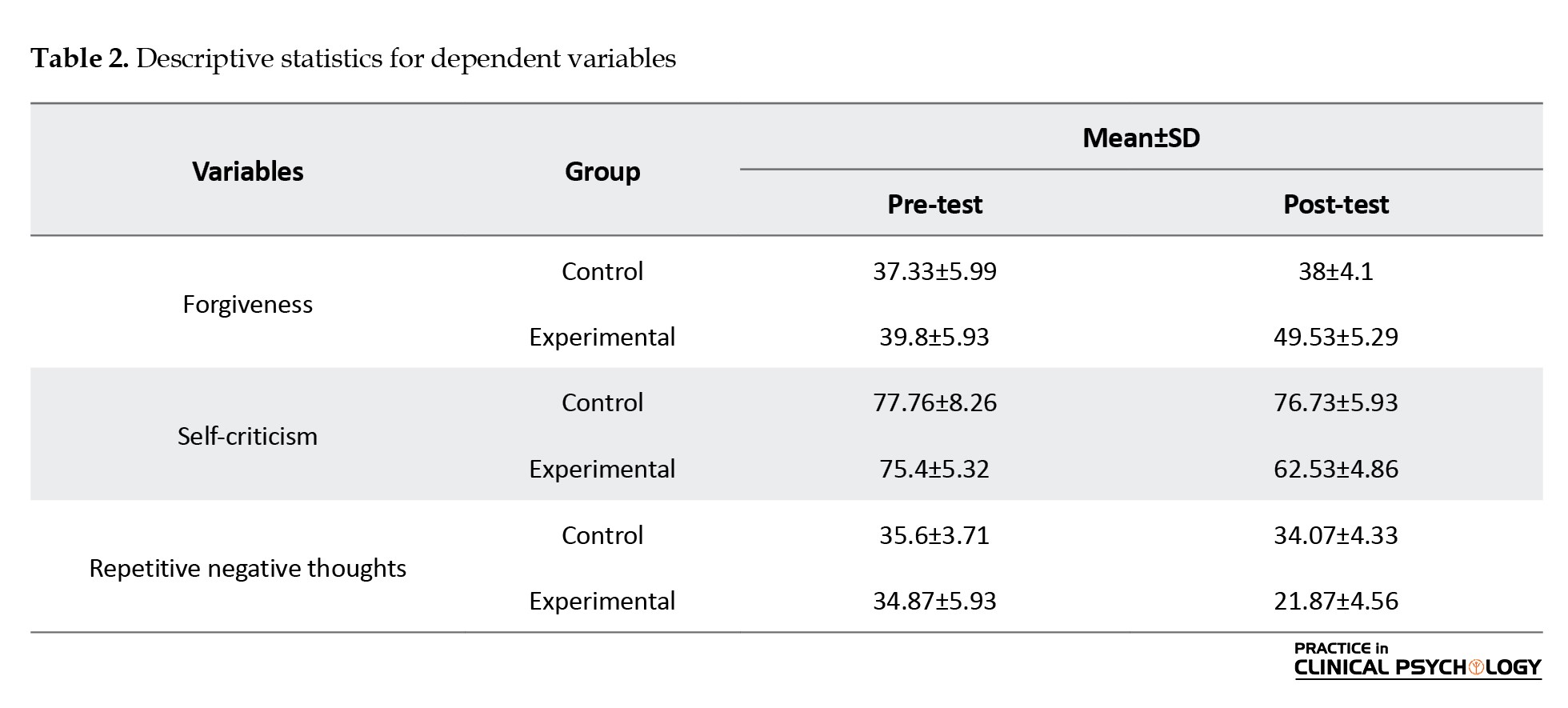

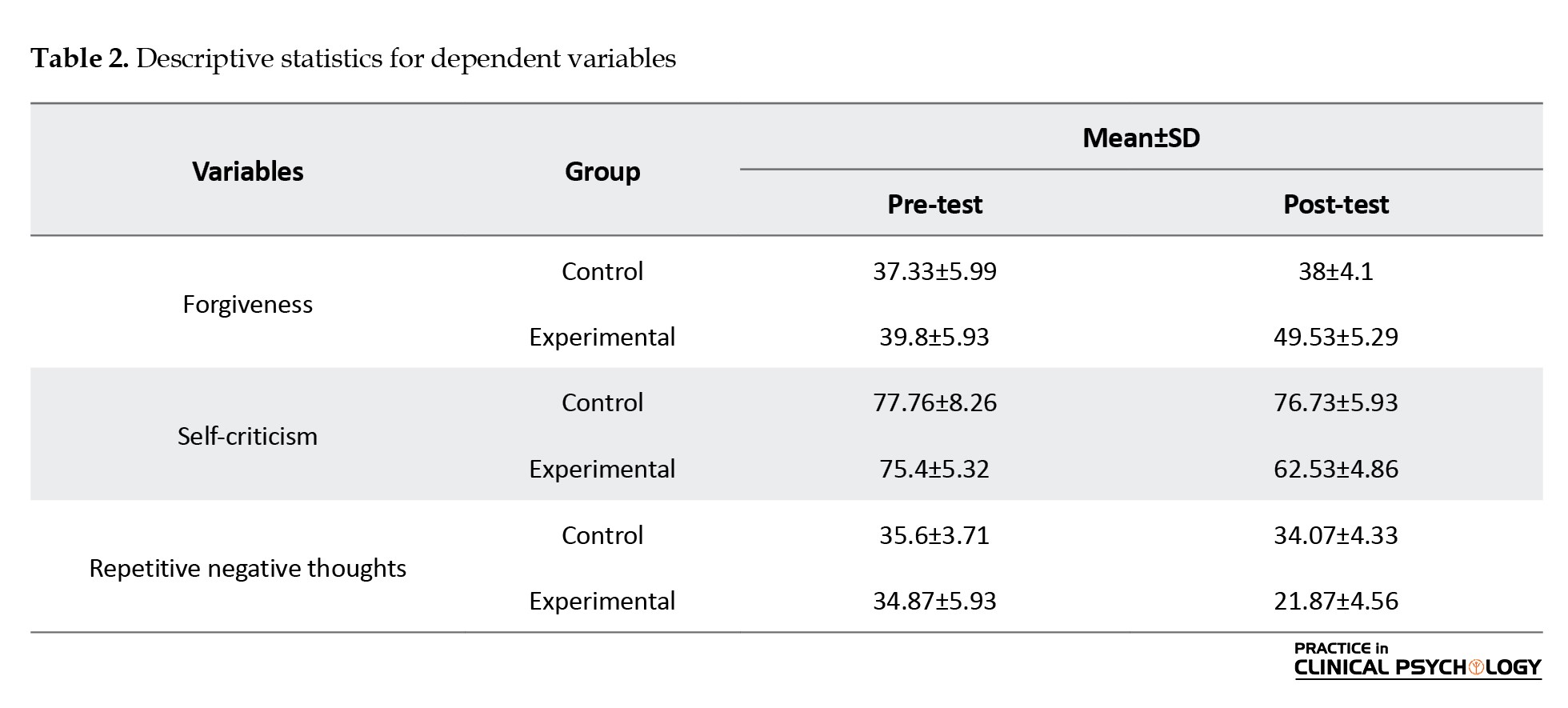

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables—forgiveness, self-criticism, and repetitive negative thoughts—across the experimental and control groups at pre-test and post-test stages.

The pre-test scores were comparable between the groups, but notable differences appeared in the post-test. The experimental group showed a significant increase in forgiveness scores and substantial reductions in self-criticism and repetitive negative thought scores compared to the control group.

Before performing ANCOVA, the test’s assumptions were evaluated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data distribution for all dependent variables, confirming normal distribution (P>0.05). Additionally, Levene’s test was applied to assess the homogeneity of variances, which showed that variances were consistent across groups for each variable (P>0.05). These results indicate that the data satisfied the assumptions required to conduct ANCOVA.

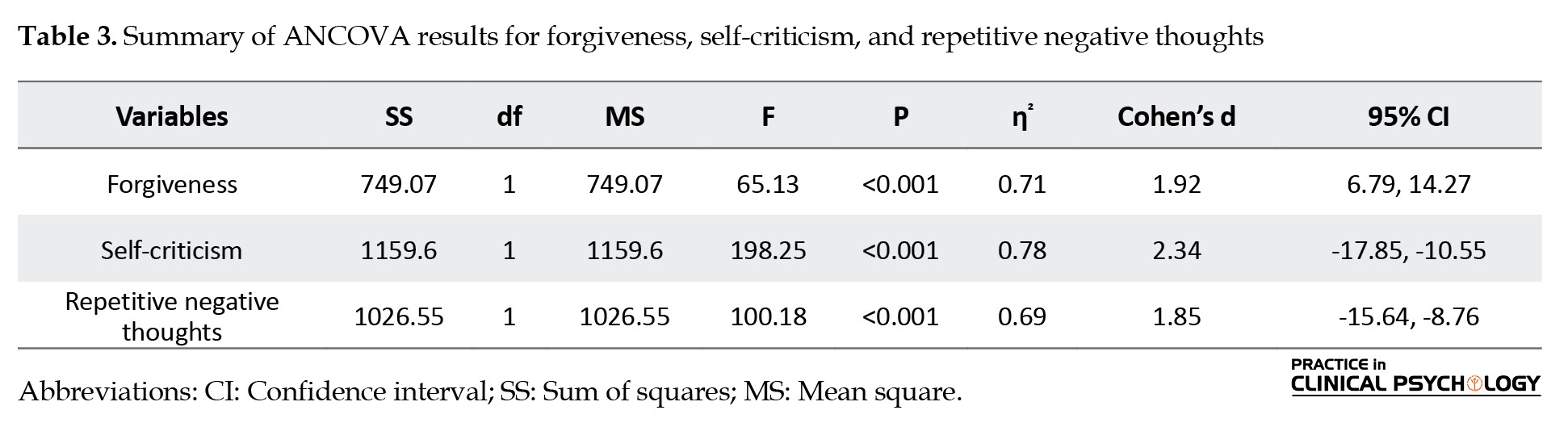

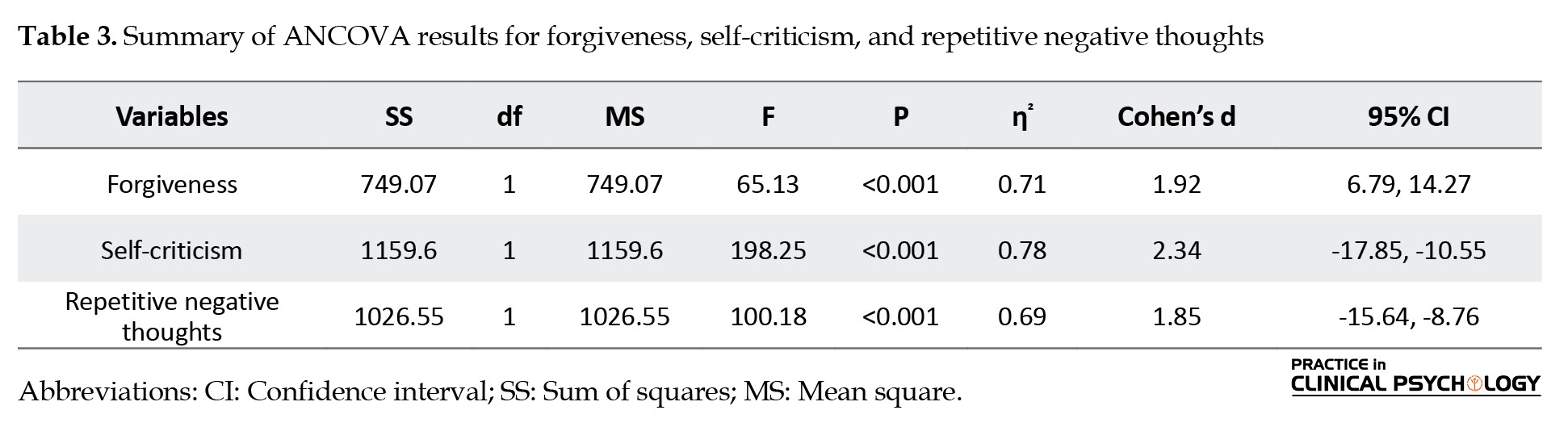

An ANCOVA was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of CFT on the dependent variables, using pre-test scores as a covariate. The findings, which revealed a statistically significant impact of the intervention on all three variables, are summarized in Table 3.

The ANCOVA results confirmed the study’s hypotheses, demonstrating that CFT significantly enhanced forgiveness (F=65.13, P<0.001, ηp2=0.71, Cohen’s d=1.92, 95% CI, 6.79%, 14.27%) and reduced self-criticism (F=198.25, P<0.001, ηp2=0.78, Cohen’s d=2.34, 95% CI, -17.85%, -10.55%) and repetitive negative thoughts (F=100.18, P<0.001, ηp2=0.69, Cohen’s d=1.85, 95% CI %, -15.64%, -8.76%) in the experimental group compared to the control group. These findings directly address the research objective of evaluating CFT’s efficacy in improving forgiveness and mitigating negative cognitive patterns, though the large effect sizes may reflect the specific sample and require cautious interpretation.

Discussion

The results of this study clearly indicate that CFT is a highly effective therapeutic intervention for women grappling with the psychological aftermath of marital infidelity. These findings not only confirm the study’s hypotheses but also provide strong empirical evidence addressing a notable gap in the research literature, which has predominantly focused on couple-based interventions. The efficacy of CFT in enhancing forgiveness and reducing self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts highlights the empowering and targeted nature of this approach.

The significant increase in forgiveness within the experimental group aligns with CFT’s theoretical model and prior research. Forgiveness in the context of marital infidelity is a complex process requiring the release of resentment to achieve emotional peace (Chi et al., 2019). CFT facilitates this by activating the soothing system and reducing threat-based emotions, such as anger and shame through self-compassion, which fosters self-forgiveness and interpersonal forgiveness (Parihar et al., 2020; Tiwari et al., 2020). This mechanism likely underpins the observed increase in forgiveness, as self-compassion mitigates self-blame, enabling women to reframe betrayal as a shared human experience rather than a personal failing. Studies, such as Rahmani Shams et al. (2022) and Kirby et al. (2017), further support CFT’s role in fostering forgiveness in high-shame contexts. However, reliance on positive findings may overlook potential challenges, such as individual variability in forgiveness readiness, warranting further exploration.

The dramatic reduction in self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts in the experimental group is consistent with the mechanisms of CFT. Infidelity often triggers harsh inner criticism, amplifying shame and inadequacy (Atapour et al., 2021). CFT techniques, such as compassionate imagery, rewire this threat-based response by fostering a compassionate self, reducing rumination, and promoting emotional regulation (Tiwari et al., 2020). This aligns with findings that self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-criticism and well-being, buffering negative cognitive cycles (Pandey et al., 2021). International studies, such as Matos et al. (2017), reinforce CFT’s efficacy in reducing rumination in trauma-related distress. However, the generalizability of these findings may be limited by cultural factors, as collectivist societies like Iran may emphasize relational harmony, which could potentially influence the impact of CFT (Parihar et al., 2020).

This study addresses a critical gap by investigating CFT as an individual intervention for infidelity-related trauma, unlike couple-based therapies, such as EFT and CBT (Asvadi et al., 2022; Bodenmann et al., 2020). CFT’s focus on self-compassion makes it particularly potent for addressing individual shame and self-criticism (Gilbert, 2009). The clinical implications of this study are substantial for real-world counseling centers. CFT can be integrated into existing therapeutic frameworks due to its structured, session-based approach, making it feasible for community counseling centers, private practices, and group therapy settings. However, its application in diverse cultural contexts requires tailoring to address cultural attitudes toward infidelity and forgiveness, particularly in collectivist societies where social stigma may exacerbate distress (Parihar et al., 2020). Training counselors in CFT can enhance its accessibility; however, implementation must consider resource constraints and cultural nuances to ensure effectiveness.

This study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. The small sample size limits the statistical power and generalizability, potentially inflating the effect sizes due to the homogeneity of the sample. Convenience sampling, used to recruit participants from counseling centers in Ahvaz, may introduce selection bias, as it may not fully represent the broader population of women affected by marital infidelity. Additionally, reliance on self-report measures, such as the FS, self-criticism levels scale, and RTQ, increases the risk of response bias, as participants’ responses may be influenced by social desirability or subjective interpretation. The absence of follow-up assessments further restricts insights into the long-term efficacy of CFT, necessitating caution in applying these findings to broader populations.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to assess the durability of CFT’s effects, as the current study lacks follow-up data. Larger, more diverse samples obtained through probability sampling could enhance generalizability, addressing the limitations of small sample sizes and convenience sampling, which may introduce selection bias and reduce external validity. Additionally, incorporating objective measures alongside self-reports may mitigate response bias. Exploring CFT’s efficacy across diverse cultural and demographic groups, beyond the Iranian context, would further elucidate its transdiagnostic potential for shame-based disorders. In summary, this study demonstrates the value of CFT in improving mental well-being but it calls for deeper critical reflection and broader research to solidify its applicability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides robust empirical evidence that CFT is a highly effective intervention for addressing the psychological distress experienced by women following marital infidelity. The findings confirm that CFT significantly enhances forgiveness while concurrently reducing debilitating self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts. By fostering a compassionate inner voice and activating the soothing emotional system, CFT empowers individuals to process their trauma and move toward emotional healing. This research highlights the unique value of CFT as a targeted, individual-focused therapeutic approach that can serve as a powerful tool for clinicians assisting women in their recovery from relational betrayal.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1404.012).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the participants for their time and commitment to this study.

References

Asvadi, M., Bakhshipoor, A., & Razavi Tabadeghan, B. Z. (2022). Comparing the effectiveness of emotionally focused couple therapy and cognitive-behavioral couple therapy on forgiveness and marital intimacy of women affected by infidelity in Mashhad. Journal of Community Health Research, 11(4), 277-285. [DOI:10.18502/jchr.v11i4.11644]

Atapour, N., Falsafinejad, M. R., Ahmadi, K., & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. (2021). A study of the processes and contextual factors of marital infidelity. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(3), 211-220. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.3.758.2]

Axinn, W. G., Zhang, Y., Ghimire, D. J., Chardoul, S. A., Scott, K. M., & Bruffaerts, R. (2020). The association between marital transitions and the onset of major depressive disorder in a south Asian general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 266, 165–172. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.069] [PMID]

Beltrán-Morillas, A. M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Unforgiveness Motivations in Romantic Relationships Experiencing Infidelity: Negative affect and anxious attachment to the partner as predictors. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 434. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00434] [PMID]

Bodenmann, G., Kessler, M., Kuhn, R., Hocker, L., & Randall, A. K. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral and emotion-focused couple therapy: Similarities and differences. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 2(3), e2741. [DOI:10.32872/cpe.v2i3.2741] [PMID]

Chi, P., Tang, Y., Worthington, E. L., Chan, C. L. W., Lam, D. O. B., & Lin, X. (2019). Intrapersonal and interpersonal facilitators of forgiveness following spousal infidelity: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(10), 1896–1915. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22825] [PMID]

Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. [DOI:10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184] [PMID]

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199-208. [DOI:10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264]

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12043] [PMID]

Hasani, M., Ahmadi, R., & Saed, O. (2022). Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire: Persian versions of the RTQ-31 and RTQ-10. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 44, e20200058.[DOI:10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0058] [PMID]

Irons, C., & Beaumont, E. (2017). The compassionate mind workbook: A step-by-step guide to developing your compassionate self Chris Irons and Elaine Beaumont. California: Robinson. [Link]

Jules, B. N., O’Connor, V. L., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2023). Judgments of event centrality as predictors of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress after infidelity: The moderating effect of relationship form. Trauma Care, 3(4), 237-250. [DOI:10.3390/traumacare3040021]

Karami, P., Ghanifar, M. H., & Ahi, G. (2024). Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and compassion-focused therapy in improving distress tolerance and self-compassion in women with experiences of marital infidelity. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling, 6(2), 27-35. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jarac.6.2.4]

Karimi, S., Doostdari, F., Bahadoriyan Lotfabadi, N., Yosefi, R., Soleymani, M., & Kianimoghadam, A. S., et al. (2023). The role of early maladaptive schemas in predicting legitimacy, seduction, normalization, sexuality, social background, and sensation seeking in marital infidelity. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 11(3), 249-258. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.3.848.2]

Khanjani, S., Foroughi, A. A., Parvizifard, A. A., Soleymani Moghadam, M., Rajabi, M., & Mojtahedzadeh, P., et al. (2025). Evaluation of psychometric properties of Persian version of Body Compassion Scale: Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: The Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 30, 12. [DOI:10.4103/jrms.jrms_520_23] [PMID]

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003] [PMID]

Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927-945. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291714002141] [PMID]

Lonergan, M., Brunet, A., Rivest-Beauregard, M., & Groleau, D. (2021). Is romantic partner betrayal a form of traumatic experience? A qualitative study. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 37(1), 19–31.[DOI:10.1002/smi.2968] [PMID]

Mahoney, A. E., McEvoy, P. M., & Moulds, M. L. (2012). Psychometric properties of the repetitive thinking questionnaire in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(2), 359-367. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.003] [PMID]

Matos, M., Duarte, J., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2017). The origins of fears of compassion: Shame and lack of safeness memories in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(6), 1207-1217. [DOI:10.1080/00223980.2017.1393380]

Mousavi, S., Mousavi, S., & Shahsavari, M. (2023). Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. Journal of Clinical Research in Paramedical Sciences, 12(2), e139058. [DOI:10.5812/jcrps-139058]

Pandey, R., Tiwari, G. K., Parihar, P., & Rai, P. K. (2021). Positive, not negative, self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and well-being. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 94(1), 1–15. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12259] [PMID]

Pandey, R., Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Mandal, S. P., Mudgal, S., & Parihar, P., et al. (2023). The relationship between self-esteem and self-forgiveness: Understanding the mediating role of positive and negative self-compassion. Psychological Thought, 16(2), 230-260. [DOI:10.37708/psyct.v16i2.571]

Parihar, P., Tiwari, G. K., & Rai, P. K. (2020). Understanding the relationship between self-compassion and interdependent happiness of the married Hindu couples. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 260-272. [Link]

Rezaei, S., Arfa, M., & Rezaei, K. (2020). Validation and norms of Rye forgiveness scale among Iranian university students. Current Psychology, 39(6), 1921-1931. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-019-00196-y]

Rokach, A., & Chan, S. H. (2023). Love and infidelity: Causes and consequences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3904. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20053904] [PMID]

Rye, M. S., Loiacono, D. M., Folck, C. D., Olszewski, B. T., Heim, T. A., & Madia, B. P. (2001). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of two forgiveness scales. Current Psychology, 20(3), 260-277. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-001-1011-6]

Shrout, M. R., & Weigel, D. J. (2020). Coping with infidelity: The moderating role of self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109631. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109631]

Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). The Levels of Self-Criticism Scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419-430. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5]

Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Rai, P. K., Pandey, R., Verma, Y., & Parihar, P., et al. (2020). Self-compassion as an intrapersonal resource of perceived positive mental health outcomes: A thematic analysis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(7), 550-569. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2020.1774524]

Zaccari, V., Fazi, M., Scarci, F., Correr, V., Trani, L., & Filomena, M. G., et al. (2024). Understanding self-criticism: A systematic review of qualitative approaches. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 21(6), 455-476. [DOI:10.36131/cnfioritieditore20240602]

Rahmani Shams, H., Nejat, H., Toozandehjan, H., Zendeh-del, A., & Bagherzadeh Golmakanih, Z. (2022). Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on metacognitive beliefs, forgiveness, and psychological well-being of women applying for divorce. Avicenna Journal of Neuropsychophysiology, 9(1), 17. [DOI:10.32592/ajnpp.2022.9.1.103]

Marital infidelity is a profoundly damaging experience, often described as a betrayal of trust and significant life trauma (Rokach & Chan, 2023). For women, the discovery of a partner’s infidelity can lead to a cascade of debilitating psychological consequences that severely compromise their mental and emotional well-being (Karimi et al., 2023). Research indicates that the betrayed partner frequently experiences symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, emotional dysregulation, and hypervigilance (Lonergan et al., 2021; Jules et al., 2023). Beyond the immediate shock, women in this situation are highly susceptible to chronic stress, anxiety, and depression, which can persist for years (Axinn et al., 2020). This emotional turmoil is often compounded by a dramatic loss of self-esteem, as they may internalize the betrayal and engage in self-blame, leading them to question their worthiness and adequacy. The rupture of a foundational relationship can also cause lasting trust issues and difficulty forming new attachments, underscoring the deep and long-term impact of this specific form of relational trauma (Atapour et al., 2021).

The psychological impact of infidelity is intricately tied to forgiveness, self-criticism, and repetitive negative thoughts, which interact to exacerbate distress. Forgiveness involves a deliberate process of releasing resentment and fostering emotional peace, often hindered by self-critical thoughts and rumination that perpetuate feelings of inadequacy (Pandey et al., 2023). Self-criticism, characterized by harsh self-judgment, amplifies negative emotions, while repetitive negative thoughts, or rumination, trap individuals in cycles of distress, reinforcing helplessness (Beltrán-Morillas et al., 2019; Shrout & Weigel, 2020). Self-compassion, as a mediator, can mitigate these effects by fostering self-kindness and reducing self-blame, thereby facilitating forgiveness and emotional recovery (Pandey et al., 2021).

Given the intense self-criticism and shame often experienced by women after infidelity, compassion-focused therapy (CFT) has emerged as a highly relevant and promising intervention (Karami et al., 2024). Developed by Paul Gilbert, CFT is a therapeutic approach that helps individuals regulate their emotions by cultivating self-compassion and kindness (Gilbert, 2009). It operates on the principle that many psychological difficulties, particularly those rooted in shame and self-criticism, stem from an overactive “threat” emotional system and an underdeveloped “soothing” system (Mousavi et al., 2023a). CFT aims to activate the soothing system, through techniques, such as compassionate imagery, soothing rhythm breathing, and compassionate letter writing, fostering a sense of emotional safety and self-acceptance (Gilbert, 2014; Irons & Beaumont, 2017). This approach has demonstrated efficacy across diverse populations, including those with trauma-related distress, suggesting its applicability to emotional challenges related to infidelity (Leaviss & Uttley, 2015).

Previous studies have predominantly explored interventions, such as emotionally focused therapy (EFT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for couples navigating infidelity (Asvadi et al., 2022; Bodenmann et al., 2020). Although these approaches have proven effective in enhancing forgiveness and closeness, there is a significant lack of research on the use of CFT to address the individual trauma experienced by the betrayed partner. CFT’s focus on self-compassion and shame reduction addresses a critical gap in individual-focused interventions for infidelity-related distress, particularly in fostering forgiveness through self-kindness and reducing rumination (Craig et al., 2020; Pandey et al., 2021). This study aimed to examine the efficacy of CFT in improving forgiveness and reducing self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts among women affected by marital infidelity in a culturally specific context.

Materials and Methods

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design, incorporating pre-test and post-test assessments with a control group, to evaluate the efficacy of CFT. The study population included all married women who faced marital infidelity and sought counseling services in Ahvaz City, Iran, between January and March 2025. A sample of 30 eligible women was selected using convenience sampling, and the sample size was determined using G*Power software. The inclusion criteria required participants to be women aged 25–45, currently married, with a history of marital infidelity within the past six months, and willing to provide informed consent. The exclusion criteria encompassed severe psychiatric conditions (e.g. psychosis), substance abuse, and participation in other concurrent psychological treatments. Thirty participants were randomly and evenly divided into an experimental (n=15) and a control group (n=15). This study adhered to the university’s ethical guidelines, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Procedure

Following participant selection and group allocation, both the experimental and control groups completed pre-test assessments using the forgiveness scale (FS), the self-criticism levels scale, and the repetitive thoughts questionnaire (RTQ). The experimental group participated in eight 90-minute CFT sessions held twice a week. The control group was placed on a waiting list and did not receive any intervention during the study period. After the intervention, both groups completed the same questionnaires as post-tests. The pre-test and post-test data were collected and prepared for statistical analysis.

Instruments

FS: The FS, developed by Rye et al. (2001), is a self-report tool designed to assess an individual’s inclination to forgive others. It comprises 15 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 15 to 105. Higher scores reflect a greater propensity for forgiveness. The FS has shown good internal consistency, with Rezaei et al. (2020) reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.74. In this study, the scale exhibited excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.89.

Levels of self-criticism scale (LSCS): The levels of LSCS, developed by Thompson and Zuroff (2004), is a 22-item self-report measure that evaluates two aspects of self-criticism: self-rejection and fear of rejection by others. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (very true for me), with total scores ranging from 22 to 110. Higher scores indicate increased self-criticism. The LSCS has demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Khanjani et al. (2025) reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.87. In the current study, the scale showed high reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.92.

RTQ: The RTQ, developed by Mahoney et al. (2012), is a 10-item tool designed to measure the frequency of repetitive negative thoughts. Responses are provided on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 4 (almost always), with total scores ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores signify a greater tendency to ruminate. The RTQ has demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 reported by Hasani et al. (2022). In this study, the RTQ demonstrated robust internal reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.85.

Intervention

The CFT intervention for the experimental group was delivered over eight 90-minute sessions. The program was structured to guide participants through the core principles of CFT, including psychoeducation on the three emotion regulation systems, cultivating a compassionate mind, and applying compassionate exercises to reduce self-criticism and promote self-forgiveness. Table 1 presents the session-by-session content.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were computed for all variables. To assess the intervention’s effectiveness, a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed. ANCOVA assumptions, including normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P>0.05), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P>0.05), and homogeneity of regression slopes (P>0.05 for interaction between covariate and group), were met. A significance threshold of P<0.05 was established for all statistical analyses.

Results

The study included 30 women impacted by marital infidelity, evenly divided into an experimental group (n=15) and a control group (n=15). The experimental group had a Mean±SD age of 36.58±4.22 years, while the control group’s Mean±SD age was 35.83±3.95 years. The Mean±SD marriage duration was 11.24±2.86 years for the experimental group and 10.95±3.16 years for the control group.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables—forgiveness, self-criticism, and repetitive negative thoughts—across the experimental and control groups at pre-test and post-test stages.

The pre-test scores were comparable between the groups, but notable differences appeared in the post-test. The experimental group showed a significant increase in forgiveness scores and substantial reductions in self-criticism and repetitive negative thought scores compared to the control group.

Before performing ANCOVA, the test’s assumptions were evaluated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data distribution for all dependent variables, confirming normal distribution (P>0.05). Additionally, Levene’s test was applied to assess the homogeneity of variances, which showed that variances were consistent across groups for each variable (P>0.05). These results indicate that the data satisfied the assumptions required to conduct ANCOVA.

An ANCOVA was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of CFT on the dependent variables, using pre-test scores as a covariate. The findings, which revealed a statistically significant impact of the intervention on all three variables, are summarized in Table 3.

The ANCOVA results confirmed the study’s hypotheses, demonstrating that CFT significantly enhanced forgiveness (F=65.13, P<0.001, ηp2=0.71, Cohen’s d=1.92, 95% CI, 6.79%, 14.27%) and reduced self-criticism (F=198.25, P<0.001, ηp2=0.78, Cohen’s d=2.34, 95% CI, -17.85%, -10.55%) and repetitive negative thoughts (F=100.18, P<0.001, ηp2=0.69, Cohen’s d=1.85, 95% CI %, -15.64%, -8.76%) in the experimental group compared to the control group. These findings directly address the research objective of evaluating CFT’s efficacy in improving forgiveness and mitigating negative cognitive patterns, though the large effect sizes may reflect the specific sample and require cautious interpretation.

Discussion

The results of this study clearly indicate that CFT is a highly effective therapeutic intervention for women grappling with the psychological aftermath of marital infidelity. These findings not only confirm the study’s hypotheses but also provide strong empirical evidence addressing a notable gap in the research literature, which has predominantly focused on couple-based interventions. The efficacy of CFT in enhancing forgiveness and reducing self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts highlights the empowering and targeted nature of this approach.

The significant increase in forgiveness within the experimental group aligns with CFT’s theoretical model and prior research. Forgiveness in the context of marital infidelity is a complex process requiring the release of resentment to achieve emotional peace (Chi et al., 2019). CFT facilitates this by activating the soothing system and reducing threat-based emotions, such as anger and shame through self-compassion, which fosters self-forgiveness and interpersonal forgiveness (Parihar et al., 2020; Tiwari et al., 2020). This mechanism likely underpins the observed increase in forgiveness, as self-compassion mitigates self-blame, enabling women to reframe betrayal as a shared human experience rather than a personal failing. Studies, such as Rahmani Shams et al. (2022) and Kirby et al. (2017), further support CFT’s role in fostering forgiveness in high-shame contexts. However, reliance on positive findings may overlook potential challenges, such as individual variability in forgiveness readiness, warranting further exploration.

The dramatic reduction in self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts in the experimental group is consistent with the mechanisms of CFT. Infidelity often triggers harsh inner criticism, amplifying shame and inadequacy (Atapour et al., 2021). CFT techniques, such as compassionate imagery, rewire this threat-based response by fostering a compassionate self, reducing rumination, and promoting emotional regulation (Tiwari et al., 2020). This aligns with findings that self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-criticism and well-being, buffering negative cognitive cycles (Pandey et al., 2021). International studies, such as Matos et al. (2017), reinforce CFT’s efficacy in reducing rumination in trauma-related distress. However, the generalizability of these findings may be limited by cultural factors, as collectivist societies like Iran may emphasize relational harmony, which could potentially influence the impact of CFT (Parihar et al., 2020).

This study addresses a critical gap by investigating CFT as an individual intervention for infidelity-related trauma, unlike couple-based therapies, such as EFT and CBT (Asvadi et al., 2022; Bodenmann et al., 2020). CFT’s focus on self-compassion makes it particularly potent for addressing individual shame and self-criticism (Gilbert, 2009). The clinical implications of this study are substantial for real-world counseling centers. CFT can be integrated into existing therapeutic frameworks due to its structured, session-based approach, making it feasible for community counseling centers, private practices, and group therapy settings. However, its application in diverse cultural contexts requires tailoring to address cultural attitudes toward infidelity and forgiveness, particularly in collectivist societies where social stigma may exacerbate distress (Parihar et al., 2020). Training counselors in CFT can enhance its accessibility; however, implementation must consider resource constraints and cultural nuances to ensure effectiveness.

This study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. The small sample size limits the statistical power and generalizability, potentially inflating the effect sizes due to the homogeneity of the sample. Convenience sampling, used to recruit participants from counseling centers in Ahvaz, may introduce selection bias, as it may not fully represent the broader population of women affected by marital infidelity. Additionally, reliance on self-report measures, such as the FS, self-criticism levels scale, and RTQ, increases the risk of response bias, as participants’ responses may be influenced by social desirability or subjective interpretation. The absence of follow-up assessments further restricts insights into the long-term efficacy of CFT, necessitating caution in applying these findings to broader populations.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to assess the durability of CFT’s effects, as the current study lacks follow-up data. Larger, more diverse samples obtained through probability sampling could enhance generalizability, addressing the limitations of small sample sizes and convenience sampling, which may introduce selection bias and reduce external validity. Additionally, incorporating objective measures alongside self-reports may mitigate response bias. Exploring CFT’s efficacy across diverse cultural and demographic groups, beyond the Iranian context, would further elucidate its transdiagnostic potential for shame-based disorders. In summary, this study demonstrates the value of CFT in improving mental well-being but it calls for deeper critical reflection and broader research to solidify its applicability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides robust empirical evidence that CFT is a highly effective intervention for addressing the psychological distress experienced by women following marital infidelity. The findings confirm that CFT significantly enhances forgiveness while concurrently reducing debilitating self-criticism and repetitive negative thoughts. By fostering a compassionate inner voice and activating the soothing emotional system, CFT empowers individuals to process their trauma and move toward emotional healing. This research highlights the unique value of CFT as a targeted, individual-focused therapeutic approach that can serve as a powerful tool for clinicians assisting women in their recovery from relational betrayal.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1404.012).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the participants for their time and commitment to this study.

References

Asvadi, M., Bakhshipoor, A., & Razavi Tabadeghan, B. Z. (2022). Comparing the effectiveness of emotionally focused couple therapy and cognitive-behavioral couple therapy on forgiveness and marital intimacy of women affected by infidelity in Mashhad. Journal of Community Health Research, 11(4), 277-285. [DOI:10.18502/jchr.v11i4.11644]

Atapour, N., Falsafinejad, M. R., Ahmadi, K., & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. (2021). A study of the processes and contextual factors of marital infidelity. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(3), 211-220. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.3.758.2]

Axinn, W. G., Zhang, Y., Ghimire, D. J., Chardoul, S. A., Scott, K. M., & Bruffaerts, R. (2020). The association between marital transitions and the onset of major depressive disorder in a south Asian general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 266, 165–172. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.069] [PMID]

Beltrán-Morillas, A. M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Unforgiveness Motivations in Romantic Relationships Experiencing Infidelity: Negative affect and anxious attachment to the partner as predictors. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 434. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00434] [PMID]

Bodenmann, G., Kessler, M., Kuhn, R., Hocker, L., & Randall, A. K. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral and emotion-focused couple therapy: Similarities and differences. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 2(3), e2741. [DOI:10.32872/cpe.v2i3.2741] [PMID]

Chi, P., Tang, Y., Worthington, E. L., Chan, C. L. W., Lam, D. O. B., & Lin, X. (2019). Intrapersonal and interpersonal facilitators of forgiveness following spousal infidelity: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(10), 1896–1915. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22825] [PMID]

Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. [DOI:10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184] [PMID]

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199-208. [DOI:10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264]

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12043] [PMID]

Hasani, M., Ahmadi, R., & Saed, O. (2022). Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire: Persian versions of the RTQ-31 and RTQ-10. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 44, e20200058.[DOI:10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0058] [PMID]

Irons, C., & Beaumont, E. (2017). The compassionate mind workbook: A step-by-step guide to developing your compassionate self Chris Irons and Elaine Beaumont. California: Robinson. [Link]

Jules, B. N., O’Connor, V. L., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2023). Judgments of event centrality as predictors of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress after infidelity: The moderating effect of relationship form. Trauma Care, 3(4), 237-250. [DOI:10.3390/traumacare3040021]

Karami, P., Ghanifar, M. H., & Ahi, G. (2024). Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and compassion-focused therapy in improving distress tolerance and self-compassion in women with experiences of marital infidelity. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling, 6(2), 27-35. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jarac.6.2.4]

Karimi, S., Doostdari, F., Bahadoriyan Lotfabadi, N., Yosefi, R., Soleymani, M., & Kianimoghadam, A. S., et al. (2023). The role of early maladaptive schemas in predicting legitimacy, seduction, normalization, sexuality, social background, and sensation seeking in marital infidelity. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 11(3), 249-258. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.3.848.2]

Khanjani, S., Foroughi, A. A., Parvizifard, A. A., Soleymani Moghadam, M., Rajabi, M., & Mojtahedzadeh, P., et al. (2025). Evaluation of psychometric properties of Persian version of Body Compassion Scale: Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: The Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 30, 12. [DOI:10.4103/jrms.jrms_520_23] [PMID]

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003] [PMID]

Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927-945. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291714002141] [PMID]

Lonergan, M., Brunet, A., Rivest-Beauregard, M., & Groleau, D. (2021). Is romantic partner betrayal a form of traumatic experience? A qualitative study. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 37(1), 19–31.[DOI:10.1002/smi.2968] [PMID]

Mahoney, A. E., McEvoy, P. M., & Moulds, M. L. (2012). Psychometric properties of the repetitive thinking questionnaire in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(2), 359-367. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.003] [PMID]

Matos, M., Duarte, J., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2017). The origins of fears of compassion: Shame and lack of safeness memories in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(6), 1207-1217. [DOI:10.1080/00223980.2017.1393380]

Mousavi, S., Mousavi, S., & Shahsavari, M. (2023). Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. Journal of Clinical Research in Paramedical Sciences, 12(2), e139058. [DOI:10.5812/jcrps-139058]

Pandey, R., Tiwari, G. K., Parihar, P., & Rai, P. K. (2021). Positive, not negative, self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and well-being. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 94(1), 1–15. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12259] [PMID]

Pandey, R., Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Mandal, S. P., Mudgal, S., & Parihar, P., et al. (2023). The relationship between self-esteem and self-forgiveness: Understanding the mediating role of positive and negative self-compassion. Psychological Thought, 16(2), 230-260. [DOI:10.37708/psyct.v16i2.571]

Parihar, P., Tiwari, G. K., & Rai, P. K. (2020). Understanding the relationship between self-compassion and interdependent happiness of the married Hindu couples. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 260-272. [Link]

Rezaei, S., Arfa, M., & Rezaei, K. (2020). Validation and norms of Rye forgiveness scale among Iranian university students. Current Psychology, 39(6), 1921-1931. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-019-00196-y]

Rokach, A., & Chan, S. H. (2023). Love and infidelity: Causes and consequences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3904. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20053904] [PMID]

Rye, M. S., Loiacono, D. M., Folck, C. D., Olszewski, B. T., Heim, T. A., & Madia, B. P. (2001). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of two forgiveness scales. Current Psychology, 20(3), 260-277. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-001-1011-6]

Shrout, M. R., & Weigel, D. J. (2020). Coping with infidelity: The moderating role of self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109631. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109631]

Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). The Levels of Self-Criticism Scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419-430. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5]

Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Rai, P. K., Pandey, R., Verma, Y., & Parihar, P., et al. (2020). Self-compassion as an intrapersonal resource of perceived positive mental health outcomes: A thematic analysis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(7), 550-569. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2020.1774524]

Zaccari, V., Fazi, M., Scarci, F., Correr, V., Trani, L., & Filomena, M. G., et al. (2024). Understanding self-criticism: A systematic review of qualitative approaches. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 21(6), 455-476. [DOI:10.36131/cnfioritieditore20240602]

Rahmani Shams, H., Nejat, H., Toozandehjan, H., Zendeh-del, A., & Bagherzadeh Golmakanih, Z. (2022). Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on metacognitive beliefs, forgiveness, and psychological well-being of women applying for divorce. Avicenna Journal of Neuropsychophysiology, 9(1), 17. [DOI:10.32592/ajnpp.2022.9.1.103]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/01/13 | Accepted: 2025/03/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/01/13 | Accepted: 2025/03/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |