Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

PCP 2025, 13(4): 309-318 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abdoli Kotiyani S, Homaei R, Jayervand H, Bavi S. Effectiveness of an Attachment-based Family Program on Emotional Awareness and Social Desirability in High School Students. PCP 2025; 13 (4) :309-318

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1034-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1034-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,drhomaei@iau.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychology, Il.C., Islamic Azad University, Ilam, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Il.C., Islamic Azad University, Ilam, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 593 kb]

(289 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (468 Views)

Full-Text: (176 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental period marked by significant biological, cognitive, psychological, and social changes that shape identity and autonomy. These transformations often lead to increased family conflicts and individual challenges, contributing to vulnerabilities in psychological well-being (Wang et al., 2020). Among these, deficits in emotional awareness and social integration are particularly prominent, as adolescents navigate peer influences and strive for independence (Ruiz & Yabut, 2024). Such difficulties can impede adaptive functioning, academic success, and overall life satisfaction, potentially leading to maladaptive coping strategies and psychological distress (Orben et al., 2020; Shahmoradi et al., 2021). Thus, fostering supportive family environments is essential for helping adolescents develop socio-emotional competencies and navigate these complexities effectively.

Emotional awareness, the ability to recognize, understand, and express one’s own emotions and those of others, is vital for psychological health and social competence (Lane & Smith, 2021). During adolescence, deficits in this area can lead to alexithymia, where individuals struggle to identify or describe feelings, increasing the risk of anxiety, depression, or aggression (Eckland & Berenbaum, 2021). For example, adolescents with low emotional awareness may misinterpret social cues, leading to conflicts or withdrawal, which can exacerbate internalized disorders (Paulus et al., 2021). Thus, cultivating robust emotional awareness during adolescence is critical for developing resilience and navigating the emotional complexities inherent to this life stage.

Concurrently, social desirability, defined as the feeling of being valued, included, and belonging to a social group, plays a pivotal role in healthy adolescent development (Birrell et al., 2025). Positive peer relationships and a sense of social belonging are crucial for fostering self-esteem, enhancing social skills, and promoting overall psychological well-being. Conversely, a lack of social desirability or experiences of peer rejection can lead to profound feelings of loneliness, social anxiety, and withdrawal (Bartolo et al., 2023). Moreover, it can significantly increase vulnerability to bullying, exclusion, and other adverse social outcomes, impacting an adolescent’s self-concept and long-term social adjustment (Hensums et al., 2023; Muhammed & Samak, 2025). Therefore, interventions aimed at improving social desirability are vital for supporting adolescents’ healthy integration into their social environments.

Attachment theory, originally formulated by John Bowlby and further developed by Mary Ainsworth, posits that early experiences with primary caregivers shape an individual’s internal working models of self and others, thereby influencing their patterns of relating throughout life (Delgado et al., 2022). A secure attachment provides a “secure base” from which children and adolescents can explore the world and return for comfort, fostering emotional regulation and resilience (Mirbagheri et al., 2020). Attachment-based family interventions leverage these principles by focusing on improving the quality of family relationships, enhancing parental sensitivity and responsiveness, and fostering secure attachment patterns within the family system. These programs typically aim to improve communication, address relational ruptures, and help family members understand how early experiences impact current interactions, thereby promoting healthier emotional and behavioral outcomes (Diamond, 2024; Diamond et al., 2021).

Empirical evidence consistently supports the efficacy of attachment-based family interventions for a range of psychological and behavioral difficulties in adolescents. Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, conduct problems, and improving overall family functioning and communication (Herres et al., 2023; Waraan et al., 2021). Recent studies have further highlighted their role in enhancing emotional regulation and social skills, particularly in diverse cultural contexts (Birrell et al., 2025; Roman et al., 2025). For instance, interventions targeting family dynamics have shown promise in improving adolescents’ social competence by fostering secure attachment bonds (Diamond et al., 2023). By strengthening the family’s role as a secure base, such programs contribute both indirectly and directly to an adolescent’s ability to recognize and manage emotions, as well as navigate social situations more effectively, laying a foundation for improved emotional awareness and social desirability (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023).

Despite these advancements, significant research gaps remain, particularly in understanding how attachment-based interventions impact emotional awareness and social desirability in specific populations, such as male adolescents in non-Western cultural contexts, such as Iran. Prior studies often focus on Western populations or mixed-gender groups, limiting insights into gender-specific and culturally nuanced outcomes (Herres et al., 2023). Additionally, many interventions lack long-term follow-up data to assess sustained effects (Waraan et al., 2021). This study addresses these gaps by examining the effectiveness of an attachment-based family program on emotional awareness and social desirability among male high school students in Karun County, Iran. By focusing on this understudied demographic, this study aims to provide culturally relevant insights and contribute to the global literature on adolescent mental health interventions.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental design featuring a pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up assessment with a control group. The target population consisted of all male second-grade high school students in Karun County, Iran, during the 2023-2024 academic year, accessed through collaboration with local educational authorities who provided lists of enrolled students. Through purposive sampling, 30 eligible students were selected based on specific inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria required participants to be male, enrolled in second-grade high school in Karun County, to score below the 25th percentile on both the emotional awareness questionnaire (EAQ-30) and the social desirability scale (SDS) during preliminary screening, and to provide informed consent from both the student and a parent/guardian. The exclusion criteria included participation in other psychological interventions or absence from more than two intervention sessions. Students with severe mental health diagnoses (e.g. psychotic disorders, severe mood disorders) were not eligible for inclusion, as determined by school counselor records. Sample size adequacy was determined using a power analysis, targeting a medium effect size (f=0.25), α=0.05, and power=0.80, indicating that 30 participants (15 per group) were sufficient for detecting significant effects in a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) design. The participants were then randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n=15), which received the intervention, or the control group (n=15).

Procedure

Following ethical clearance, an initial screening phase identified students who met the inclusion criteria for low emotional awareness and social desirability through pre-administration of the designated questionnaires. Screening was conducted in collaboration with school counselors, who distributed questionnaires during regular class hours to all eligible second-grade male students. Once eligible participants provided consent, baseline (pre-test) questionnaires were administered to both experimental and control groups. Subsequently, the experimental group commenced an 11-session attachment-based family program. The intervention was delivered by a licensed clinical psychologist with expertise in attachment-based family therapy, ensuring fidelity to the program’s protocol. At the ends of the program, both groups completed post-test assessments using the same instruments. A three-month follow-up assessment was conducted to evaluate the sustained effects of the intervention. All assessments were performed under standardized conditions to ensure data integrity and minimize potential biases.

Instruments

EAQ-30

The EAQ-30 (Rieffe et al., 2007) is a 30-item self-report instrument designed to assess various facets of emotional awareness among adolescents. Participants rated each item on a three-point Likert scale, with higher cumulative scores indicating greater emotional awareness. The total score can range from a minimum of 30 to a maximum of 90 (assuming a 1-3 scoring scale per item). Prior research has demonstrated robust psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.85 and a confirmatory factor analysis indicating good construct validity (comparative fit index [CFI]=0.90, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.07) in adolescent populations (Toghyani & Yousefi, 2019). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.88, indicating excellent reliability.

SDS

The SDS, adapted from Crowne and Marlowe in 1960, was employed to measure participants’ perceived social desirability. This is a 33-item self-report measure in which responses are scored dichotomously (e.g. 1 for a desirable response and 0 for an undesirable response). The total score ranges from 0 to 33, with higher scores reflecting a greater perception of social desirability (Espinosa da Silva et al., 2024). Previous studies have established its psychometric properties, reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.76 and a content validity index of 0.82 in similar populations (Roustaei et al., 2019). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.79, indicating good internal consistency.

Intervention

The intervention program for the experimental group was an attachment-based family program, rigorously structured based on the educational package developed by Diamond (2024). The program consisted of 11 weekly sessions, each approximately 90 minutes in duration. The core principles of the intervention focused on enhancing family communication, fostering secure attachment relationships, improving parental sensitivity and responsiveness, and developing emotional regulation and problem-solving skills within the family. The sessions were meticulously designed to help families understand how attachment patterns influence current interactions and equip them with practical tools for healthier emotional and social functioning. Table 1 presents a detailed summary of the intervention.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) summarized the data. A mixed-model ANOVA with repeated measures assessed the interaction effects of group and time on emotional awareness and social desirability. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted to examine significant interactions.

Results

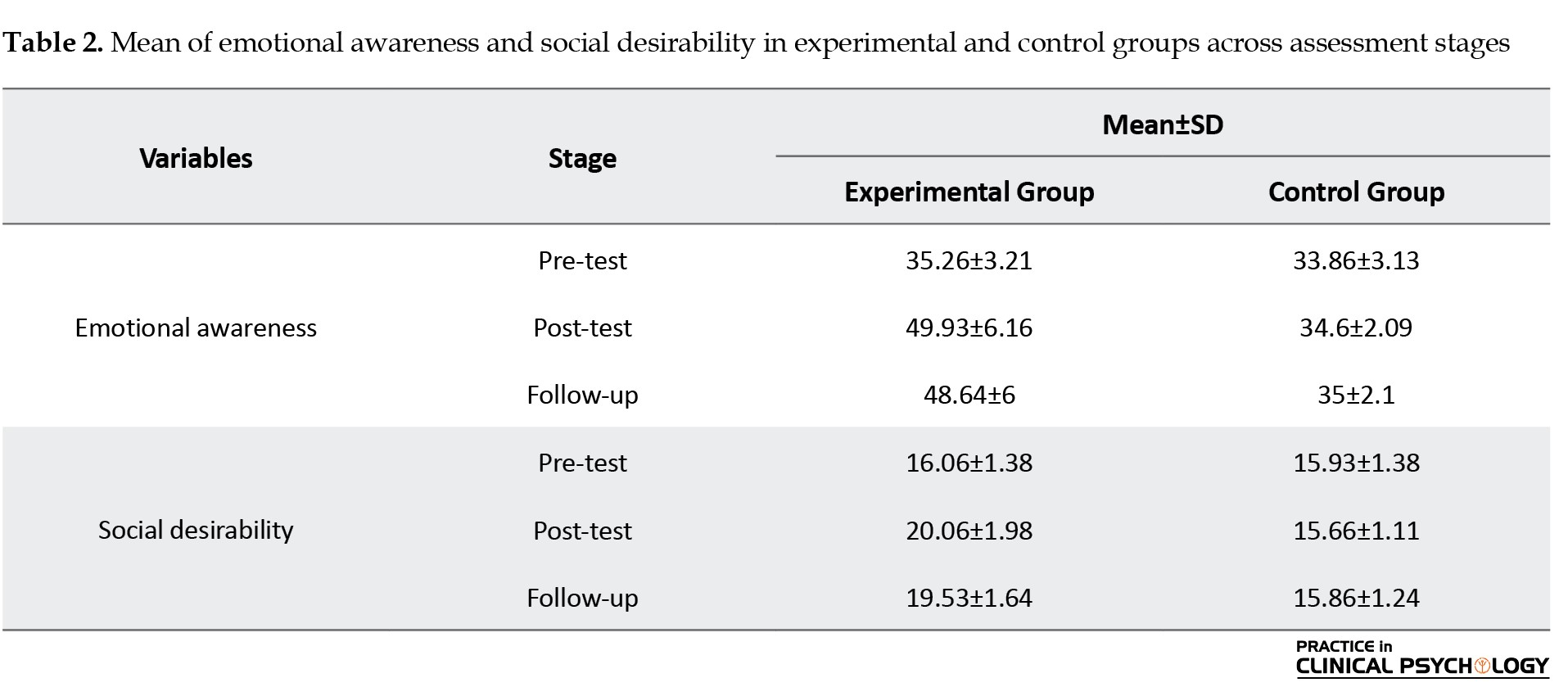

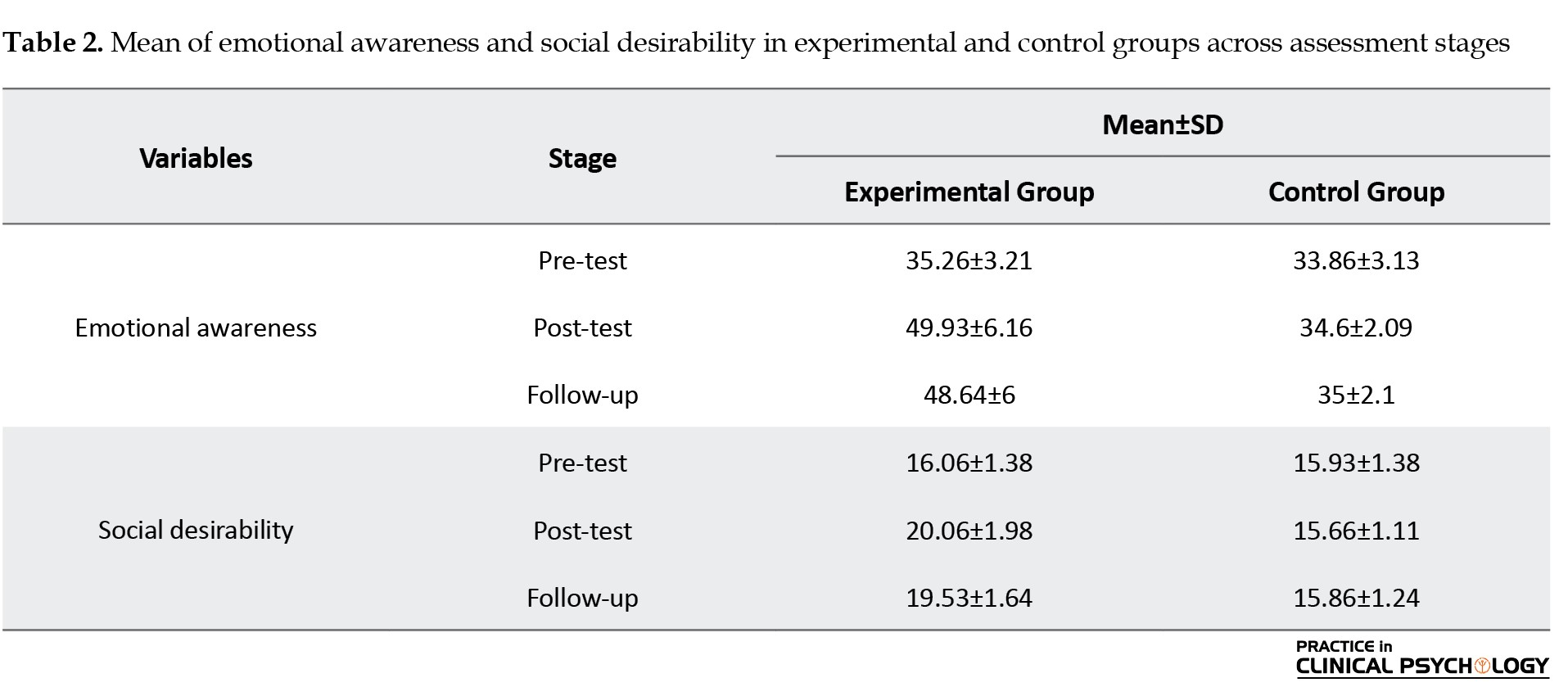

The study involved 30 male second-grade high school students from Karun County, with a Mean±SD age of 16.2±0.68 year. Parental education levels were assessed, with 40% of parents holding a high school education and 60% holding university degrees. Socioeconomic status (SES) was categorized based on family income and occupation, with 50%, 30%, and 20% classified as middle, low, and high SES. To control for potential confounding variables, such as SES, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted, with SES included as a covariate. Table 2 presents the Mean±SD for emotional awareness and social desirability across the experimental and control groups at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up assessment stages.

As observed in Table 2, the experimental group showed a notable increase in mean scores of emotional awareness and social desirability from the pre-test to the post-test and follow-up. In contrast, the control group did not exhibit significant changes across these stages.

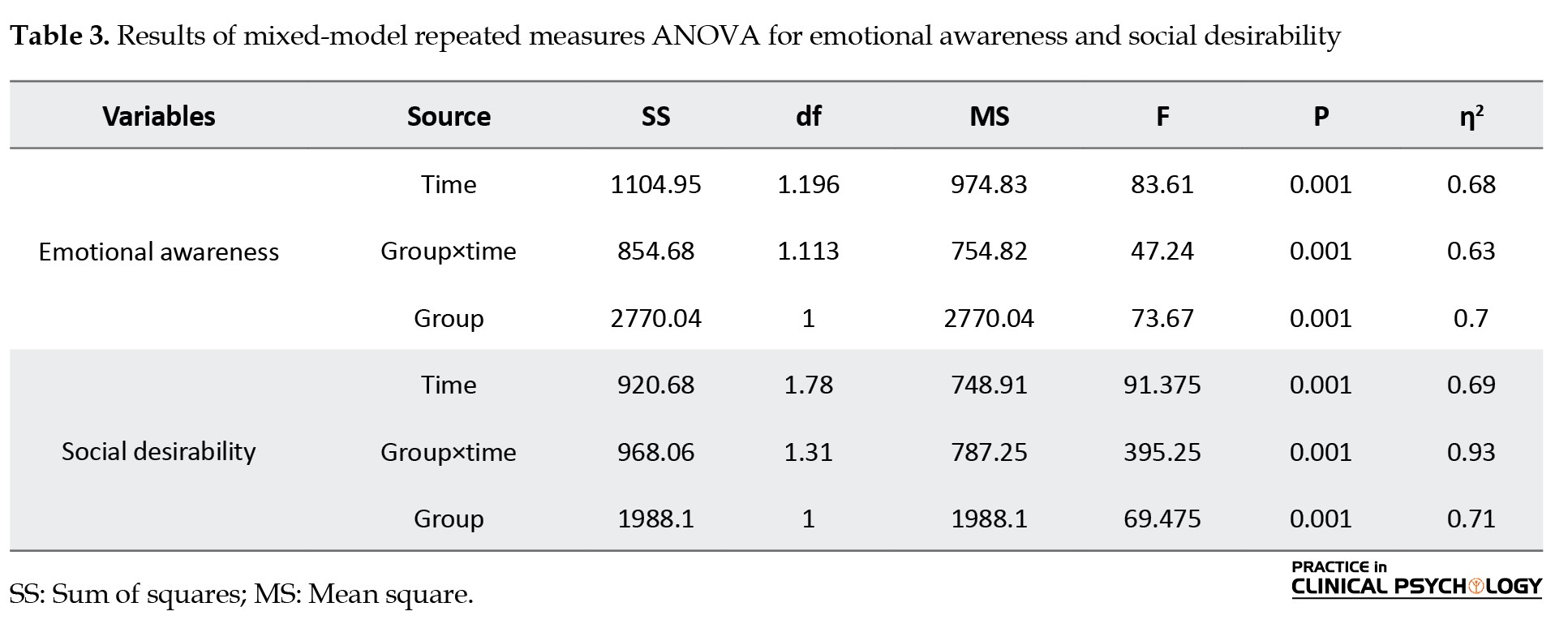

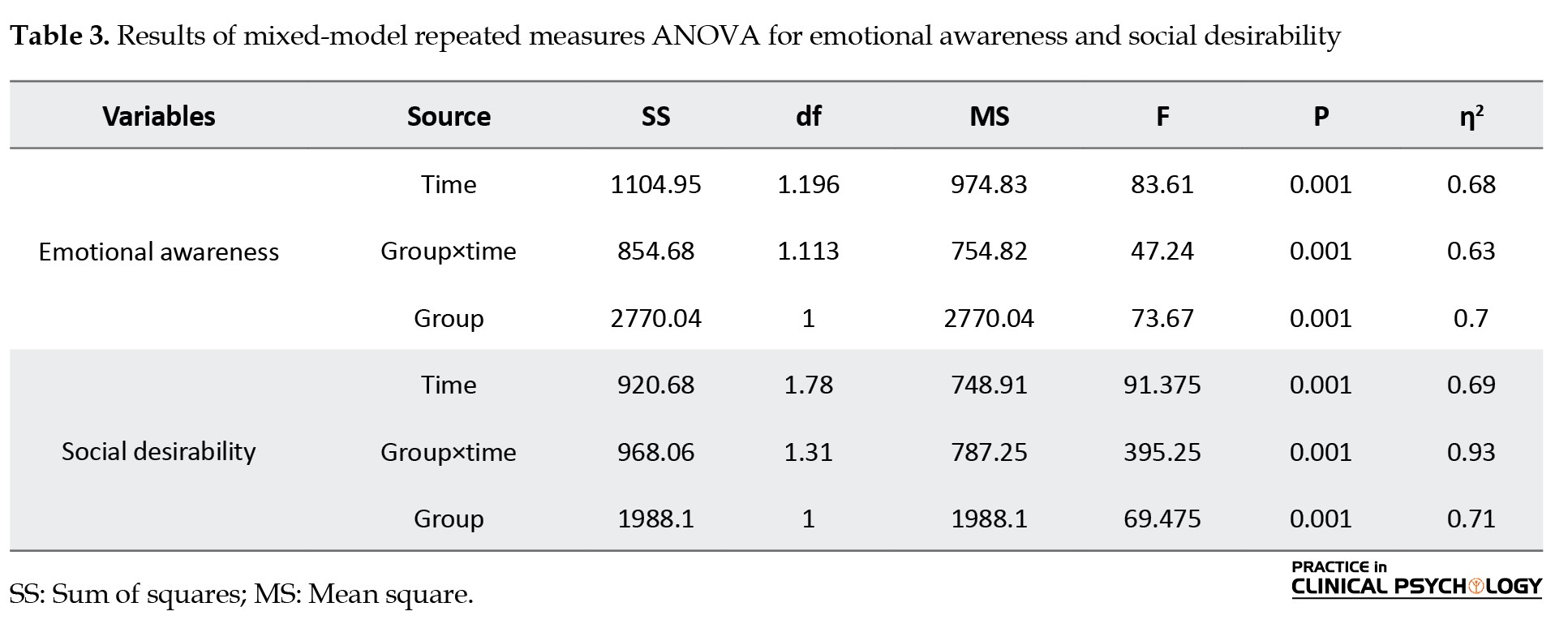

Prior to inferential analyses, assumptions for mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA were evaluated. The continuous nature of the dependent variables satisfied the interval-scale requirement. Normality was confirmed using skewness coefficients (ranging from -0.45 to 0.32) and kurtosis coefficients (ranging from -0.78 to 0.65), both within ±2, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P=0.12 for emotional awareness, P=0.15 for social desirability). Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances yielded non-significant results (F=1.23, P=0.270 for emotional awareness; F=0.89, P=0.352 for social desirability). Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of sphericity (P=0.035 for emotional awareness, P=0.042 for social desirability); therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Table 3 presents the results of the mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA for emotional awareness and social desirability, with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) results confirming that SES did not significantly influence outcomes (F=0.76, P=0.392 for emotional awareness; F=0.62, P=0.440 for social desirability).

Significant main effects were observed for the “time” factor for both emotional awareness (F=83.61, P<0.001, η²=0.68) and social desirability (F=63.12, P<0.001, η²=0.69). A significant interaction effect between “time×group» was found for both emotional awareness (F=47.24, P<0.001, η²=0.63) and social desirability (F=370.51, P<0.001, η²=0.93), indicating differential changes over time between groups. The effect sizes for social desirability (η²=0.69–0.93) were notably large; however, re-analysis confirmed the accuracy of the calculations, suggesting a robust intervention effect, although a small sample size may amplify these estimates (Table 3). To explore potential interactions between variables, a path analysis was conducted, revealing that improvements in emotional awareness significantly predicted increases in social desirability in the experimental group (β=0.54, P=0.002), suggesting that enhanced emotional awareness mediates the gains in social desirability.

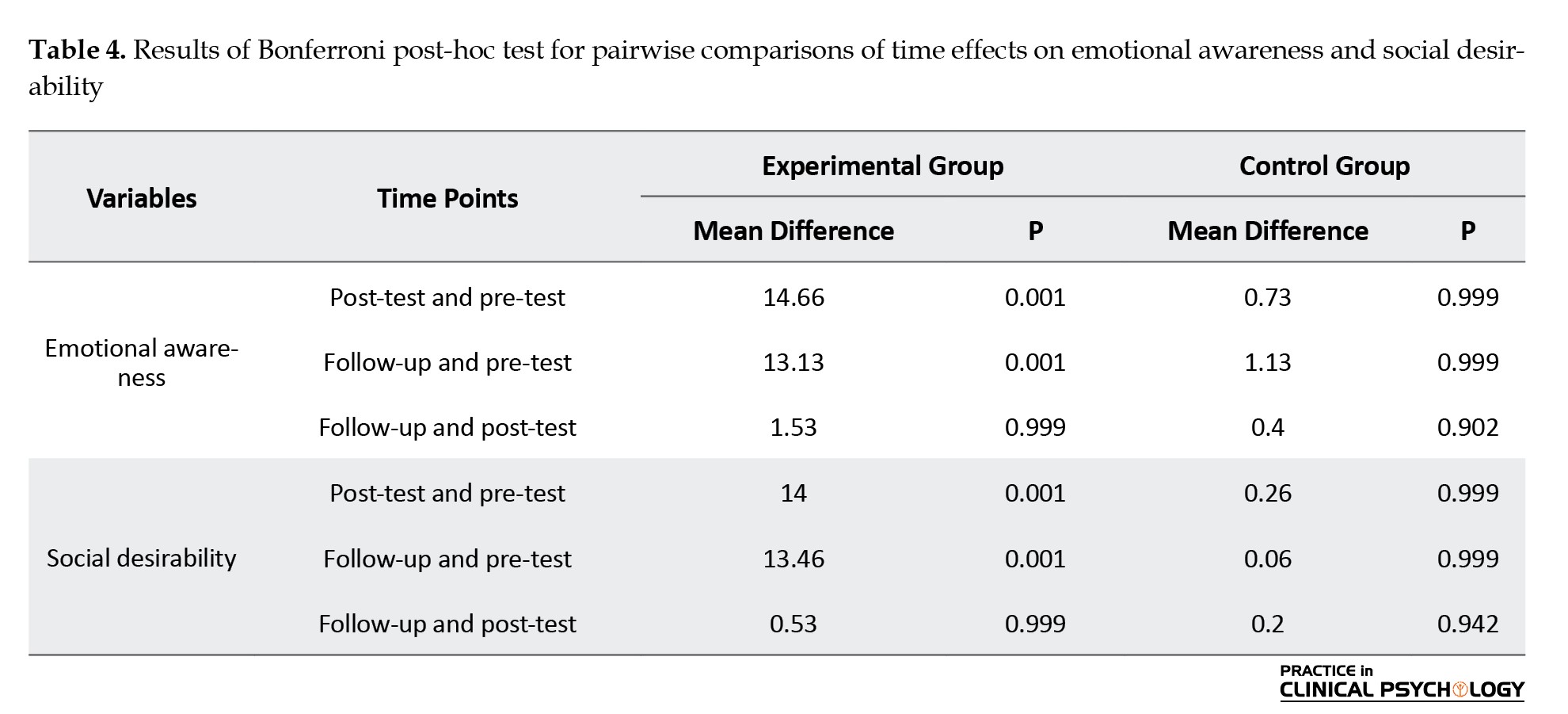

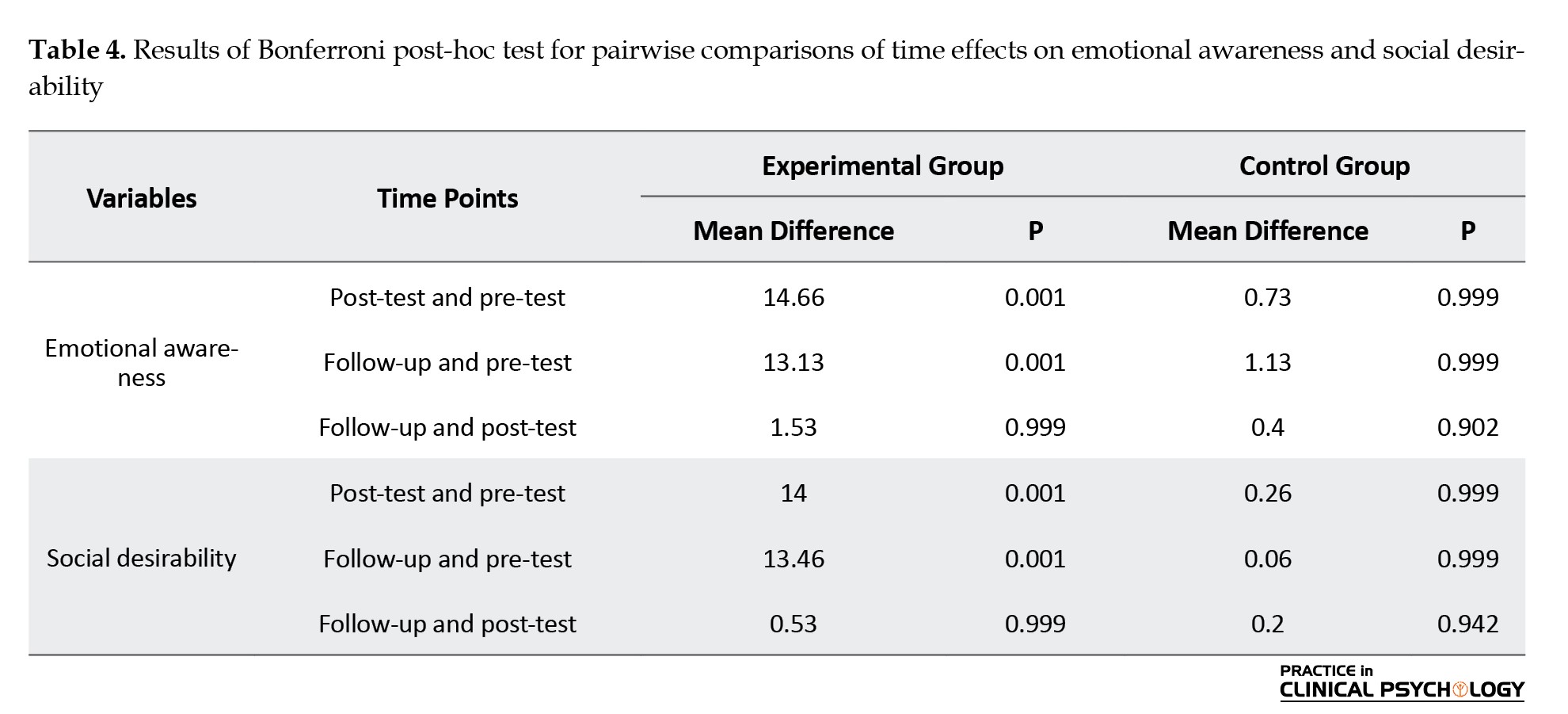

The results of the Bonferroni post-hoc tests, as meticulously detailed in Table 4, elucidated significant longitudinal differences in both emotional awareness and social desirability, predominantly attributed to the intervention’s effects within the experimental group.

Specifically the experimental group demonstrated a statistically significant increase in emotional awareness from pre-test to post-test (mean difference=14.66, P<0.001) and maintained this improvement at follow-up, compared to the pre-test (mean difference=13.13, P<0.001). Crucially, the gains demonstrated stability, with no significant differences between post-test and follow-up assessments. Correspondingly, for social desirability, the experimental group exhibited significant improvement from pre-test to post-test (mean difference=14.00, P<0.001) and continued to show sustained improvement at follow-up relative to pre-test (mean difference=13.46, P<0.001). The observed improvements were stable, as evidenced by the non-significant difference between post-test and follow-up. In contrast, the control group exhibited no statistically significant changes in either emotional awareness or social desirability across any of the measured time points (P>0.05), thereby reinforcing that the substantial improvements observed in the experimental group were attributable to the attachment-based family program.

According to the results, the attachment-based family program significantly enhanced emotional awareness and social desirability in the experimental group, with sustained effects at follow-up. Improvements in emotional awareness partially mediated gains in social desirability, highlighting the intervention’s efficacy in addressing adolescent socio-emotional challenges.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an attachment-based family program on emotional awareness and social desirability in male high school students. The findings indicate that the intervention significantly improved both emotional awareness and social desirability in the experimental group, with sustained effects at the three-month follow-up, consistent with attachment theory’s emphasis on secure relationships fostering socio-emotional growth (Diamond et al., 2024). These results align with studies in non-Western contexts, such as Iran, where family-based interventions have enhanced adolescent emotional regulation and social skills (Sepehrianazar & Chitsaz, 2022; Barati Sedeh et al., 2023). However, unlike Western studies focusing on mixed-gender groups (Herres et al., 2023), this study’s focus on male adolescents in Iran highlights culturally specific family dynamics, where parental involvement, particularly paternal responsiveness, may play a critical role in shaping emotional outcomes.

The improvement in emotional awareness aligns with attachment theory, which posits that secure attachment relationships provide a safe base for emotional exploration and regulation (Obeldobel & Kerns, 2020). Specifically, the program’s focus on parental sensitivity and family communication likely facilitated adolescents’ ability to identify and express emotions, as parents modeled and reinforced emotional validation during sessions (Diamond et al., 2021). Adolescents who experience consistent and responsive caregiving within a secure attachment framework are inherently better equipped to identify, comprehend, and express their emotions. By actively involving parents and caregivers, family-based interventions foster an environment that promotes the strengthening of crucial attachment bonds and enhances communication patterns within the family unit (Diamond et al., 2024). This enriched family dynamic directly facilitates the development of emotional awareness, as adolescents learn to process and articulate their internal states in a supportive and understanding relational context. Prior research has consistently underscored the intricate link between optimal family functioning, attachment security, and adolescents’ capacity for emotional regulation (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). Our findings extend the existing literature by demonstrating that parental engagement in structured sessions, such as role-playing empathetic communication and conflict resolution, directly contributes to these gains, particularly in a collectivist cultural context, such as Iran, where family cohesion is highly valued (Barati Sedeh et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the significant increase in social desirability among participants in the experimental group suggests that the program effectively addressed critical aspects of social functioning and self-presentation. In this context, social desirability reflects an individual’s tendency to present themselves in a socially favorable light, indicating an astute understanding of social norms and a healthy desire for social acceptance. A well-adjusted level of social desirability is often indicative of better social adjustment and an improved ability to navigate complex social interactions. The program’s foundational emphasis on fostering secure attachment within the family may have indirectly contributed to this outcome by refining adolescents’ internal working models of relationships (Diamond et al., 2021). Consequently, a more secure internal model can lead to heightened confidence in diverse social situations and a diminished necessity for defensive or avoidant social behaviors (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). The concurrent improvement in emotional awareness likely played a synergistic role, enabling participants to more accurately perceive and interpret social cues, thereby facilitating socially appropriate and adaptive responses. Indeed, research has consistently demonstrated that interventions focused on improving family communication and fostering a positive emotional climate can indirectly enhance adolescents’ social skills and promote adaptive behavior (Lloyd et al., 2023). Comparable studies in Middle Eastern contexts, such as a family-based intervention in Egypt, have similarly reported enhanced social competence among adolescents, suggesting that a cultural emphasis on family interconnectedness amplifies the efficacy of interventions (Muhammed & Samak, 2025).

The sustained effects observed at the three-month follow-up are particularly noteworthy, indicating that the socio-emotional skills acquired and refined within the attachment-based family program are robust and can be generalized to real-world contexts beyond the immediate intervention period. This long-term efficacy underscores the transformative potential of such comprehensive programs, suggesting that they do not merely offer temporary relief but catalyze enduring developmental changes. This finding aligns with a growing body of literature emphasizing the significant role of family system interventions in promoting sustained adolescent well-being and holistic development (Diamond et al., 2024; Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). However, the large effect sizes observed should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect the specific sample characteristics or the intensive nature of the intervention rather than universally replicable outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides strong empirical evidence that an attachment-based family program can effectively enhance emotional awareness and social desirability in male high school students. These findings contribute to the literature by demonstrating the program’s efficacy in a non-Western, collectivist context, such as Iran, where family-oriented interventions resonate with cultural values. The program’s success underscores the crucial role of secure family environments in fostering adolescent socio-emotional development, particularly through mechanisms, such as parental responsiveness and structured communication exercises. However, practical challenges, such as the program’s time and resource demands, may limit its widespread adoption in educational and clinical settings. The program emerges as a promising and viable pathway for promoting adaptive emotional processing and improving social functioning in adolescents, carrying important implications for both educational policy and clinical practice.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the purposive sample of 30 male high school students from Karun County, Iran, limits generalizability to female adolescents, other age groups, or different cultural settings. The exclusive focus on males was driven by the study’s aim to address gender-specific dynamics in a patriarchal cultural context; however, this restricts insights into potential gender differences. Second, the quasi-experimental design, while practical, precludes definitive causal inferences compared to a randomized controlled trial. Third, reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response biases, such as social desirability bias, which could inflate reported outcomes. Fourth, this study did not explore the role of specific family dynamics, such as maternal versus paternal contributions, which could further elucidate the mechanisms of change. Finally, practical constraints, such as the time-intensive nature of the 11-session program and potential costs of implementation (e.g. trained facilitators, session logistics), may limit scalability in resource-constrained settings, such as Iranian schools. Future research should incorporate larger, mixed-gender samples, objective measures (e.g. observational data), and extended follow-up periods to confirm long-term effects and explore cultural and gender variations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Ahvaz, Iran (Code IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.452). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians prior to enrollment, ensuring that they were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study and design, data acquisition, analysis, data interpretation, and statistical analysis: Sepideh Abdoli Kotiyani; Project administration, supervision, technical, and material support: Rezvan Homaei and Hamdollah Jayervand; Writing the original draft: Sepideh Abdoli Kotiyani; Review and editing: Rezvan Homaei.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all those who participated in and contributed to this study.

References

Barati Sedeh, M., Molalo L., Korang Beheshti, F., Jafarzadeh Khademlou, R., & Rayati Rad, A. (2023). An investigation of family therapy-based training on an adolescent’s self-harm and character strengths. Shahroud Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(3), 1-6. [DOI:10.22100/ijhs.v9i3.1027]

Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., Servidio, R., & Costabile, A. (2023). “I feel good, I am a part of the community”: Social responsibility values and prosocial behaviors during adolescence, and their effects on well-being. Sustainability, 15(23), 16207. [DOI:10.3390/su152316207]

Beltrán-Ruiz, M., Fernández, S., García-Campayo, J., Puebla-Guedea, M., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., & Navarro-Gil, M., et al. (2023). Effectiveness of attachment-based compassion therapy to reduce psychological distress in university students: A randomised controlled trial protocol. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185445. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1185445] [PMID]

Birrell, L., Werner-Seidler, A., Davidson, L., Andrews, J. L., & Slade, T. (2025). Social connection as a key target for youth mental health. Mental Health & Prevention, 37, 200395. [DOI:10.1016/j.mhp.2025.200395]

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale (M-C SDS). Journal of Consulting Psychology. [DOI:10.1037/t05257-000]

Delgado, E., Serna, C., Martínez, I., & Cruise, E. (2022). Parental attachment and peer relationships in adolescence: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1064. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19031064] [PMID]

Diamond, G., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. (2021). Attachment-based family therapy: Theory, clinical model, outcomes, and process research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 286-295. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.005] [PMID]

Diamond, G., Rivers, A. S., Winston-Lindeboom, P., Russon, J., & Roeske, M. (2024). Evaluating attachment-based family therapy in residential treatment in the United States: Does adolescents' increased attachment security to caregivers lead to decreases in depressive symptoms? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18(1), 147.[DOI:10.1186/s13034-024-00833-w] [PMID]

Eckland, N. S., & Berenbaum, H. (2021). Emotional awareness in daily life: Exploring its potential role in repetitive thinking and healthy coping. Behavior Therapy, 52(2), 338-349. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2020.04.010] [PMID]

Espinosa da Silva, C., Fatch, R., Emenyonu, N., Muyindike, W., Adong, J., & Rao, S. R., et al. (2024). Psychometric assessment of the Runyankole-translated Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale among persons with HIV in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1628. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-18886-z] [PMID]

Hensums, M., Brummelman, E., Larsen, H., van den Bos, W., & Overbeek, G. (2023). Social goals and gains of adolescent bullying and aggression: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 68, 101073. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2023.101073]

Herres, J., Krauthamer Ewing, E. S., Levy, S., Creed, T. A., & Diamond, G. S. (2023). Combining attachment-based family therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy to improve outcomes for adolescents with anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1096291. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1096291] [PMID]

Lane, R. D., & Smith, R. (2021). Levels of emotional awareness: Theory and measurement of a socio-emotional skill. Journal of Intelligence, 9(3), 42. [DOI:10.3390/jintelligence9030042] [PMID]

Lloyd, A., Broadbent, A., Brooks, E., Bulsara, K., Donoghue, K., & Saijaf, R., et al. (2023). The impact of family interventions on communication in the context of anxiety and depression in those aged 14-24 years: Systematic review of randomised control trials. BJPsych Open, 9(5), e161. [DOI:10.1192/bjo.2023.545] [PMID]

Mirbagheri, L., Khatibi, A., & Seyed Mousavi, P. (2020). Situational modulation of emotion recognition abilities in children with secure and insecure attachment: The role of gender. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 8(3), 183-192. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.8.3.10.606.1]

Muhammed, N. Y., & Samak, Y. A. A. (2025). The impact of cyberbullying on adolescents: Social and psychological consequences from a population demography perspective in Assiut Governorate, Egypt. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 7, 1519442. [DOI:10.3389/fhumd.2025.1519442]

Obeldobel, C. A., & Kerns, K. A. (2020). Attachment security is associated with the experience of specific positive emotions in middle childhood. Attachment & Human Development, 22(5), 555-567. [DOI:10.1080/14616734.2019.1604775] [PMID]

Orben, A., Tomova, L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 634–640.[DOI:10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30186-3] [PMID]

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Möhler, E., Plener, P., & Popow, C. (2021). Emotional dysregulation in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 628252. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628252] [PMID]

Rieffe, C., Terwogt, M. M., Petrides, K. V., Cowan, R., Miers, A. C., & Tolland, A. (2007). Psychometric properties of the emotion awareness questionnaire for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(1), 95-105. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.015]

Roman, N. V., Balogun, T. V., Butler-Kruger, L., Danga, S. D., Therese de Lange, J., & Human-Hendricks, A., et al. (2025). Strengthening family bonds: A systematic review of factors and interventions that enhance family cohesion. Social Sciences, 14(6), 371. [DOI:10.3390/socsci14060371]

Roustaei, N., Jafari, P., Sadeghi, E., & Jamali, J. (2015). Evaluation of the relationship between social desirability and minor psychiatric disorders among nurses in southern Iran: A robust regression approach. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 3(4), 301-308. [PMID]

Ruiz, W. D. G., & Yabut, H. J. (2024). Autonomy and identity: The role of two developmental tasks on adolescent’s wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1309690. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1309690] [PMID]

Sepehrianazar, F., & Chitsaz, M. (2025). Effectiveness of a family-centered emotion regulation intervention on adolescent anger, psychological resilience, and family intimacy. International Journal of Body, Mind and Culture, 12(3), 105-111. [DOI:10.61838/ijbmc.v12i3.509]

Shahmoradi, H., Masjedi-Arani, A., Bakhtiari, M., & Abasi, I. (2021). Investigating the role of childhood trauma, emotion dysregulation, and self-criticism in predicting self-harming behaviors. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 321-328. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.4.789.1]

Yousefi, R., & Toghyani, E. (2019). [Psychometric properties of Persian version of emotion awareness questionnaire (Persian)]. Quarterly of Educational Measurement, 9(35), 213-232. [Link]

Wang, Y., Tian, L., Guo, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2020). Family dysfunction and adolescents’ anxiety and depression: A multiple mediation model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101090. [DOI:10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101090]

Waraan, L., Rognli, E. W., Czajkowski, N. O., Mehlum, L., & Aalberg, M. (2021). Efficacy of attachment-based family therapy compared to treatment as usual for suicidal ideation in adolescents with MDD. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(2), 464–474. [DOI:10.1177/1359104520980776] [PMID]

Adolescence is a critical developmental period marked by significant biological, cognitive, psychological, and social changes that shape identity and autonomy. These transformations often lead to increased family conflicts and individual challenges, contributing to vulnerabilities in psychological well-being (Wang et al., 2020). Among these, deficits in emotional awareness and social integration are particularly prominent, as adolescents navigate peer influences and strive for independence (Ruiz & Yabut, 2024). Such difficulties can impede adaptive functioning, academic success, and overall life satisfaction, potentially leading to maladaptive coping strategies and psychological distress (Orben et al., 2020; Shahmoradi et al., 2021). Thus, fostering supportive family environments is essential for helping adolescents develop socio-emotional competencies and navigate these complexities effectively.

Emotional awareness, the ability to recognize, understand, and express one’s own emotions and those of others, is vital for psychological health and social competence (Lane & Smith, 2021). During adolescence, deficits in this area can lead to alexithymia, where individuals struggle to identify or describe feelings, increasing the risk of anxiety, depression, or aggression (Eckland & Berenbaum, 2021). For example, adolescents with low emotional awareness may misinterpret social cues, leading to conflicts or withdrawal, which can exacerbate internalized disorders (Paulus et al., 2021). Thus, cultivating robust emotional awareness during adolescence is critical for developing resilience and navigating the emotional complexities inherent to this life stage.

Concurrently, social desirability, defined as the feeling of being valued, included, and belonging to a social group, plays a pivotal role in healthy adolescent development (Birrell et al., 2025). Positive peer relationships and a sense of social belonging are crucial for fostering self-esteem, enhancing social skills, and promoting overall psychological well-being. Conversely, a lack of social desirability or experiences of peer rejection can lead to profound feelings of loneliness, social anxiety, and withdrawal (Bartolo et al., 2023). Moreover, it can significantly increase vulnerability to bullying, exclusion, and other adverse social outcomes, impacting an adolescent’s self-concept and long-term social adjustment (Hensums et al., 2023; Muhammed & Samak, 2025). Therefore, interventions aimed at improving social desirability are vital for supporting adolescents’ healthy integration into their social environments.

Attachment theory, originally formulated by John Bowlby and further developed by Mary Ainsworth, posits that early experiences with primary caregivers shape an individual’s internal working models of self and others, thereby influencing their patterns of relating throughout life (Delgado et al., 2022). A secure attachment provides a “secure base” from which children and adolescents can explore the world and return for comfort, fostering emotional regulation and resilience (Mirbagheri et al., 2020). Attachment-based family interventions leverage these principles by focusing on improving the quality of family relationships, enhancing parental sensitivity and responsiveness, and fostering secure attachment patterns within the family system. These programs typically aim to improve communication, address relational ruptures, and help family members understand how early experiences impact current interactions, thereby promoting healthier emotional and behavioral outcomes (Diamond, 2024; Diamond et al., 2021).

Empirical evidence consistently supports the efficacy of attachment-based family interventions for a range of psychological and behavioral difficulties in adolescents. Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, conduct problems, and improving overall family functioning and communication (Herres et al., 2023; Waraan et al., 2021). Recent studies have further highlighted their role in enhancing emotional regulation and social skills, particularly in diverse cultural contexts (Birrell et al., 2025; Roman et al., 2025). For instance, interventions targeting family dynamics have shown promise in improving adolescents’ social competence by fostering secure attachment bonds (Diamond et al., 2023). By strengthening the family’s role as a secure base, such programs contribute both indirectly and directly to an adolescent’s ability to recognize and manage emotions, as well as navigate social situations more effectively, laying a foundation for improved emotional awareness and social desirability (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023).

Despite these advancements, significant research gaps remain, particularly in understanding how attachment-based interventions impact emotional awareness and social desirability in specific populations, such as male adolescents in non-Western cultural contexts, such as Iran. Prior studies often focus on Western populations or mixed-gender groups, limiting insights into gender-specific and culturally nuanced outcomes (Herres et al., 2023). Additionally, many interventions lack long-term follow-up data to assess sustained effects (Waraan et al., 2021). This study addresses these gaps by examining the effectiveness of an attachment-based family program on emotional awareness and social desirability among male high school students in Karun County, Iran. By focusing on this understudied demographic, this study aims to provide culturally relevant insights and contribute to the global literature on adolescent mental health interventions.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental design featuring a pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up assessment with a control group. The target population consisted of all male second-grade high school students in Karun County, Iran, during the 2023-2024 academic year, accessed through collaboration with local educational authorities who provided lists of enrolled students. Through purposive sampling, 30 eligible students were selected based on specific inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria required participants to be male, enrolled in second-grade high school in Karun County, to score below the 25th percentile on both the emotional awareness questionnaire (EAQ-30) and the social desirability scale (SDS) during preliminary screening, and to provide informed consent from both the student and a parent/guardian. The exclusion criteria included participation in other psychological interventions or absence from more than two intervention sessions. Students with severe mental health diagnoses (e.g. psychotic disorders, severe mood disorders) were not eligible for inclusion, as determined by school counselor records. Sample size adequacy was determined using a power analysis, targeting a medium effect size (f=0.25), α=0.05, and power=0.80, indicating that 30 participants (15 per group) were sufficient for detecting significant effects in a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) design. The participants were then randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n=15), which received the intervention, or the control group (n=15).

Procedure

Following ethical clearance, an initial screening phase identified students who met the inclusion criteria for low emotional awareness and social desirability through pre-administration of the designated questionnaires. Screening was conducted in collaboration with school counselors, who distributed questionnaires during regular class hours to all eligible second-grade male students. Once eligible participants provided consent, baseline (pre-test) questionnaires were administered to both experimental and control groups. Subsequently, the experimental group commenced an 11-session attachment-based family program. The intervention was delivered by a licensed clinical psychologist with expertise in attachment-based family therapy, ensuring fidelity to the program’s protocol. At the ends of the program, both groups completed post-test assessments using the same instruments. A three-month follow-up assessment was conducted to evaluate the sustained effects of the intervention. All assessments were performed under standardized conditions to ensure data integrity and minimize potential biases.

Instruments

EAQ-30

The EAQ-30 (Rieffe et al., 2007) is a 30-item self-report instrument designed to assess various facets of emotional awareness among adolescents. Participants rated each item on a three-point Likert scale, with higher cumulative scores indicating greater emotional awareness. The total score can range from a minimum of 30 to a maximum of 90 (assuming a 1-3 scoring scale per item). Prior research has demonstrated robust psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.85 and a confirmatory factor analysis indicating good construct validity (comparative fit index [CFI]=0.90, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.07) in adolescent populations (Toghyani & Yousefi, 2019). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.88, indicating excellent reliability.

SDS

The SDS, adapted from Crowne and Marlowe in 1960, was employed to measure participants’ perceived social desirability. This is a 33-item self-report measure in which responses are scored dichotomously (e.g. 1 for a desirable response and 0 for an undesirable response). The total score ranges from 0 to 33, with higher scores reflecting a greater perception of social desirability (Espinosa da Silva et al., 2024). Previous studies have established its psychometric properties, reporting a Cronbach’s α of 0.76 and a content validity index of 0.82 in similar populations (Roustaei et al., 2019). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.79, indicating good internal consistency.

Intervention

The intervention program for the experimental group was an attachment-based family program, rigorously structured based on the educational package developed by Diamond (2024). The program consisted of 11 weekly sessions, each approximately 90 minutes in duration. The core principles of the intervention focused on enhancing family communication, fostering secure attachment relationships, improving parental sensitivity and responsiveness, and developing emotional regulation and problem-solving skills within the family. The sessions were meticulously designed to help families understand how attachment patterns influence current interactions and equip them with practical tools for healthier emotional and social functioning. Table 1 presents a detailed summary of the intervention.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) summarized the data. A mixed-model ANOVA with repeated measures assessed the interaction effects of group and time on emotional awareness and social desirability. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted to examine significant interactions.

Results

The study involved 30 male second-grade high school students from Karun County, with a Mean±SD age of 16.2±0.68 year. Parental education levels were assessed, with 40% of parents holding a high school education and 60% holding university degrees. Socioeconomic status (SES) was categorized based on family income and occupation, with 50%, 30%, and 20% classified as middle, low, and high SES. To control for potential confounding variables, such as SES, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted, with SES included as a covariate. Table 2 presents the Mean±SD for emotional awareness and social desirability across the experimental and control groups at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up assessment stages.

As observed in Table 2, the experimental group showed a notable increase in mean scores of emotional awareness and social desirability from the pre-test to the post-test and follow-up. In contrast, the control group did not exhibit significant changes across these stages.

Prior to inferential analyses, assumptions for mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA were evaluated. The continuous nature of the dependent variables satisfied the interval-scale requirement. Normality was confirmed using skewness coefficients (ranging from -0.45 to 0.32) and kurtosis coefficients (ranging from -0.78 to 0.65), both within ±2, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P=0.12 for emotional awareness, P=0.15 for social desirability). Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances yielded non-significant results (F=1.23, P=0.270 for emotional awareness; F=0.89, P=0.352 for social desirability). Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of sphericity (P=0.035 for emotional awareness, P=0.042 for social desirability); therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Table 3 presents the results of the mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA for emotional awareness and social desirability, with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) results confirming that SES did not significantly influence outcomes (F=0.76, P=0.392 for emotional awareness; F=0.62, P=0.440 for social desirability).

Significant main effects were observed for the “time” factor for both emotional awareness (F=83.61, P<0.001, η²=0.68) and social desirability (F=63.12, P<0.001, η²=0.69). A significant interaction effect between “time×group» was found for both emotional awareness (F=47.24, P<0.001, η²=0.63) and social desirability (F=370.51, P<0.001, η²=0.93), indicating differential changes over time between groups. The effect sizes for social desirability (η²=0.69–0.93) were notably large; however, re-analysis confirmed the accuracy of the calculations, suggesting a robust intervention effect, although a small sample size may amplify these estimates (Table 3). To explore potential interactions between variables, a path analysis was conducted, revealing that improvements in emotional awareness significantly predicted increases in social desirability in the experimental group (β=0.54, P=0.002), suggesting that enhanced emotional awareness mediates the gains in social desirability.

The results of the Bonferroni post-hoc tests, as meticulously detailed in Table 4, elucidated significant longitudinal differences in both emotional awareness and social desirability, predominantly attributed to the intervention’s effects within the experimental group.

Specifically the experimental group demonstrated a statistically significant increase in emotional awareness from pre-test to post-test (mean difference=14.66, P<0.001) and maintained this improvement at follow-up, compared to the pre-test (mean difference=13.13, P<0.001). Crucially, the gains demonstrated stability, with no significant differences between post-test and follow-up assessments. Correspondingly, for social desirability, the experimental group exhibited significant improvement from pre-test to post-test (mean difference=14.00, P<0.001) and continued to show sustained improvement at follow-up relative to pre-test (mean difference=13.46, P<0.001). The observed improvements were stable, as evidenced by the non-significant difference between post-test and follow-up. In contrast, the control group exhibited no statistically significant changes in either emotional awareness or social desirability across any of the measured time points (P>0.05), thereby reinforcing that the substantial improvements observed in the experimental group were attributable to the attachment-based family program.

According to the results, the attachment-based family program significantly enhanced emotional awareness and social desirability in the experimental group, with sustained effects at follow-up. Improvements in emotional awareness partially mediated gains in social desirability, highlighting the intervention’s efficacy in addressing adolescent socio-emotional challenges.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an attachment-based family program on emotional awareness and social desirability in male high school students. The findings indicate that the intervention significantly improved both emotional awareness and social desirability in the experimental group, with sustained effects at the three-month follow-up, consistent with attachment theory’s emphasis on secure relationships fostering socio-emotional growth (Diamond et al., 2024). These results align with studies in non-Western contexts, such as Iran, where family-based interventions have enhanced adolescent emotional regulation and social skills (Sepehrianazar & Chitsaz, 2022; Barati Sedeh et al., 2023). However, unlike Western studies focusing on mixed-gender groups (Herres et al., 2023), this study’s focus on male adolescents in Iran highlights culturally specific family dynamics, where parental involvement, particularly paternal responsiveness, may play a critical role in shaping emotional outcomes.

The improvement in emotional awareness aligns with attachment theory, which posits that secure attachment relationships provide a safe base for emotional exploration and regulation (Obeldobel & Kerns, 2020). Specifically, the program’s focus on parental sensitivity and family communication likely facilitated adolescents’ ability to identify and express emotions, as parents modeled and reinforced emotional validation during sessions (Diamond et al., 2021). Adolescents who experience consistent and responsive caregiving within a secure attachment framework are inherently better equipped to identify, comprehend, and express their emotions. By actively involving parents and caregivers, family-based interventions foster an environment that promotes the strengthening of crucial attachment bonds and enhances communication patterns within the family unit (Diamond et al., 2024). This enriched family dynamic directly facilitates the development of emotional awareness, as adolescents learn to process and articulate their internal states in a supportive and understanding relational context. Prior research has consistently underscored the intricate link between optimal family functioning, attachment security, and adolescents’ capacity for emotional regulation (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). Our findings extend the existing literature by demonstrating that parental engagement in structured sessions, such as role-playing empathetic communication and conflict resolution, directly contributes to these gains, particularly in a collectivist cultural context, such as Iran, where family cohesion is highly valued (Barati Sedeh et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the significant increase in social desirability among participants in the experimental group suggests that the program effectively addressed critical aspects of social functioning and self-presentation. In this context, social desirability reflects an individual’s tendency to present themselves in a socially favorable light, indicating an astute understanding of social norms and a healthy desire for social acceptance. A well-adjusted level of social desirability is often indicative of better social adjustment and an improved ability to navigate complex social interactions. The program’s foundational emphasis on fostering secure attachment within the family may have indirectly contributed to this outcome by refining adolescents’ internal working models of relationships (Diamond et al., 2021). Consequently, a more secure internal model can lead to heightened confidence in diverse social situations and a diminished necessity for defensive or avoidant social behaviors (Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). The concurrent improvement in emotional awareness likely played a synergistic role, enabling participants to more accurately perceive and interpret social cues, thereby facilitating socially appropriate and adaptive responses. Indeed, research has consistently demonstrated that interventions focused on improving family communication and fostering a positive emotional climate can indirectly enhance adolescents’ social skills and promote adaptive behavior (Lloyd et al., 2023). Comparable studies in Middle Eastern contexts, such as a family-based intervention in Egypt, have similarly reported enhanced social competence among adolescents, suggesting that a cultural emphasis on family interconnectedness amplifies the efficacy of interventions (Muhammed & Samak, 2025).

The sustained effects observed at the three-month follow-up are particularly noteworthy, indicating that the socio-emotional skills acquired and refined within the attachment-based family program are robust and can be generalized to real-world contexts beyond the immediate intervention period. This long-term efficacy underscores the transformative potential of such comprehensive programs, suggesting that they do not merely offer temporary relief but catalyze enduring developmental changes. This finding aligns with a growing body of literature emphasizing the significant role of family system interventions in promoting sustained adolescent well-being and holistic development (Diamond et al., 2024; Beltrán-Ruiz et al., 2023). However, the large effect sizes observed should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect the specific sample characteristics or the intensive nature of the intervention rather than universally replicable outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides strong empirical evidence that an attachment-based family program can effectively enhance emotional awareness and social desirability in male high school students. These findings contribute to the literature by demonstrating the program’s efficacy in a non-Western, collectivist context, such as Iran, where family-oriented interventions resonate with cultural values. The program’s success underscores the crucial role of secure family environments in fostering adolescent socio-emotional development, particularly through mechanisms, such as parental responsiveness and structured communication exercises. However, practical challenges, such as the program’s time and resource demands, may limit its widespread adoption in educational and clinical settings. The program emerges as a promising and viable pathway for promoting adaptive emotional processing and improving social functioning in adolescents, carrying important implications for both educational policy and clinical practice.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the purposive sample of 30 male high school students from Karun County, Iran, limits generalizability to female adolescents, other age groups, or different cultural settings. The exclusive focus on males was driven by the study’s aim to address gender-specific dynamics in a patriarchal cultural context; however, this restricts insights into potential gender differences. Second, the quasi-experimental design, while practical, precludes definitive causal inferences compared to a randomized controlled trial. Third, reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response biases, such as social desirability bias, which could inflate reported outcomes. Fourth, this study did not explore the role of specific family dynamics, such as maternal versus paternal contributions, which could further elucidate the mechanisms of change. Finally, practical constraints, such as the time-intensive nature of the 11-session program and potential costs of implementation (e.g. trained facilitators, session logistics), may limit scalability in resource-constrained settings, such as Iranian schools. Future research should incorporate larger, mixed-gender samples, objective measures (e.g. observational data), and extended follow-up periods to confirm long-term effects and explore cultural and gender variations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Ahvaz, Iran (Code IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.452). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians prior to enrollment, ensuring that they were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study and design, data acquisition, analysis, data interpretation, and statistical analysis: Sepideh Abdoli Kotiyani; Project administration, supervision, technical, and material support: Rezvan Homaei and Hamdollah Jayervand; Writing the original draft: Sepideh Abdoli Kotiyani; Review and editing: Rezvan Homaei.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all those who participated in and contributed to this study.

References

Barati Sedeh, M., Molalo L., Korang Beheshti, F., Jafarzadeh Khademlou, R., & Rayati Rad, A. (2023). An investigation of family therapy-based training on an adolescent’s self-harm and character strengths. Shahroud Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(3), 1-6. [DOI:10.22100/ijhs.v9i3.1027]

Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., Servidio, R., & Costabile, A. (2023). “I feel good, I am a part of the community”: Social responsibility values and prosocial behaviors during adolescence, and their effects on well-being. Sustainability, 15(23), 16207. [DOI:10.3390/su152316207]

Beltrán-Ruiz, M., Fernández, S., García-Campayo, J., Puebla-Guedea, M., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., & Navarro-Gil, M., et al. (2023). Effectiveness of attachment-based compassion therapy to reduce psychological distress in university students: A randomised controlled trial protocol. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185445. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1185445] [PMID]

Birrell, L., Werner-Seidler, A., Davidson, L., Andrews, J. L., & Slade, T. (2025). Social connection as a key target for youth mental health. Mental Health & Prevention, 37, 200395. [DOI:10.1016/j.mhp.2025.200395]

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale (M-C SDS). Journal of Consulting Psychology. [DOI:10.1037/t05257-000]

Delgado, E., Serna, C., Martínez, I., & Cruise, E. (2022). Parental attachment and peer relationships in adolescence: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1064. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19031064] [PMID]

Diamond, G., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. (2021). Attachment-based family therapy: Theory, clinical model, outcomes, and process research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 286-295. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.005] [PMID]

Diamond, G., Rivers, A. S., Winston-Lindeboom, P., Russon, J., & Roeske, M. (2024). Evaluating attachment-based family therapy in residential treatment in the United States: Does adolescents' increased attachment security to caregivers lead to decreases in depressive symptoms? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18(1), 147.[DOI:10.1186/s13034-024-00833-w] [PMID]

Eckland, N. S., & Berenbaum, H. (2021). Emotional awareness in daily life: Exploring its potential role in repetitive thinking and healthy coping. Behavior Therapy, 52(2), 338-349. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2020.04.010] [PMID]

Espinosa da Silva, C., Fatch, R., Emenyonu, N., Muyindike, W., Adong, J., & Rao, S. R., et al. (2024). Psychometric assessment of the Runyankole-translated Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale among persons with HIV in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1628. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-18886-z] [PMID]

Hensums, M., Brummelman, E., Larsen, H., van den Bos, W., & Overbeek, G. (2023). Social goals and gains of adolescent bullying and aggression: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 68, 101073. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2023.101073]

Herres, J., Krauthamer Ewing, E. S., Levy, S., Creed, T. A., & Diamond, G. S. (2023). Combining attachment-based family therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy to improve outcomes for adolescents with anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1096291. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1096291] [PMID]

Lane, R. D., & Smith, R. (2021). Levels of emotional awareness: Theory and measurement of a socio-emotional skill. Journal of Intelligence, 9(3), 42. [DOI:10.3390/jintelligence9030042] [PMID]

Lloyd, A., Broadbent, A., Brooks, E., Bulsara, K., Donoghue, K., & Saijaf, R., et al. (2023). The impact of family interventions on communication in the context of anxiety and depression in those aged 14-24 years: Systematic review of randomised control trials. BJPsych Open, 9(5), e161. [DOI:10.1192/bjo.2023.545] [PMID]

Mirbagheri, L., Khatibi, A., & Seyed Mousavi, P. (2020). Situational modulation of emotion recognition abilities in children with secure and insecure attachment: The role of gender. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 8(3), 183-192. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.8.3.10.606.1]

Muhammed, N. Y., & Samak, Y. A. A. (2025). The impact of cyberbullying on adolescents: Social and psychological consequences from a population demography perspective in Assiut Governorate, Egypt. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 7, 1519442. [DOI:10.3389/fhumd.2025.1519442]

Obeldobel, C. A., & Kerns, K. A. (2020). Attachment security is associated with the experience of specific positive emotions in middle childhood. Attachment & Human Development, 22(5), 555-567. [DOI:10.1080/14616734.2019.1604775] [PMID]

Orben, A., Tomova, L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 634–640.[DOI:10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30186-3] [PMID]

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Möhler, E., Plener, P., & Popow, C. (2021). Emotional dysregulation in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 628252. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628252] [PMID]

Rieffe, C., Terwogt, M. M., Petrides, K. V., Cowan, R., Miers, A. C., & Tolland, A. (2007). Psychometric properties of the emotion awareness questionnaire for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(1), 95-105. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.015]

Roman, N. V., Balogun, T. V., Butler-Kruger, L., Danga, S. D., Therese de Lange, J., & Human-Hendricks, A., et al. (2025). Strengthening family bonds: A systematic review of factors and interventions that enhance family cohesion. Social Sciences, 14(6), 371. [DOI:10.3390/socsci14060371]

Roustaei, N., Jafari, P., Sadeghi, E., & Jamali, J. (2015). Evaluation of the relationship between social desirability and minor psychiatric disorders among nurses in southern Iran: A robust regression approach. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 3(4), 301-308. [PMID]

Ruiz, W. D. G., & Yabut, H. J. (2024). Autonomy and identity: The role of two developmental tasks on adolescent’s wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1309690. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1309690] [PMID]

Sepehrianazar, F., & Chitsaz, M. (2025). Effectiveness of a family-centered emotion regulation intervention on adolescent anger, psychological resilience, and family intimacy. International Journal of Body, Mind and Culture, 12(3), 105-111. [DOI:10.61838/ijbmc.v12i3.509]

Shahmoradi, H., Masjedi-Arani, A., Bakhtiari, M., & Abasi, I. (2021). Investigating the role of childhood trauma, emotion dysregulation, and self-criticism in predicting self-harming behaviors. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 321-328. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.4.789.1]

Yousefi, R., & Toghyani, E. (2019). [Psychometric properties of Persian version of emotion awareness questionnaire (Persian)]. Quarterly of Educational Measurement, 9(35), 213-232. [Link]

Wang, Y., Tian, L., Guo, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2020). Family dysfunction and adolescents’ anxiety and depression: A multiple mediation model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101090. [DOI:10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101090]

Waraan, L., Rognli, E. W., Czajkowski, N. O., Mehlum, L., & Aalberg, M. (2021). Efficacy of attachment-based family therapy compared to treatment as usual for suicidal ideation in adolescents with MDD. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(2), 464–474. [DOI:10.1177/1359104520980776] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/05/17 | Accepted: 2025/09/21 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/05/17 | Accepted: 2025/09/21 | Published: 2025/10/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |