Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 47-56 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Loveimi K, Bavi S, Fard R J. AI-assisted Intervention and ACT-based Intervention: Boosting Self-efficacy and Self-regulation in Bilingual Students. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :47-56

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1033-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1033-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,sassanbavi@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), Artificial intelligence (AI), Emotional regulation, Self-efficacy, Students

Full-Text [PDF 574 kb]

(279 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (757 Views)

Full-Text: (153 Views)

Introduction

Bilingual students constitute a significant and expanding demographic within global educational systems. However, they frequently navigate a unique landscape of academic challenges that can profoundly influence their learning trajectories (Gao & Yang, 2023). Beyond the inherent complexities of mastering multiple languages, these students often contend with issues such as increased cognitive load, cultural identity conflicts, and disparities in pedagogical expectations across linguistic contexts (Ulum, 2024). These multifaceted challenges can manifest as difficulties in academic comprehension, effective communication, and the crucial development of adaptive learning strategies. As a result, bilingual learners may experience elevated academic stress and lessened self-perceptions of their capabilities; they struggle in independently managing their learning processes (Moradpour & Bavi, 2025). Moreover, students in suburban areas, such as those in Ahvaz City, Iran may face additional barriers due to limited access to educational resources, potentially exacerbating challenges in developing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, which are critical for academic success. Addressing these distinct vulnerabilities is imperative to ensure their successful integration and optimal academic progression within diverse educational environments.

Academic self-efficacy, a pivotal construct within Bandura’s (1996) social cognitive theory, denotes an individual’s conviction in their capability to execute academic tasks successfully. This belief extends beyond mere skill possession to encompass confidence in one’s capacity to deploy those skills to attain specific learning outcomes effectively (Cabras et al., 2024). Elevated academic self-efficacy promotes enhanced persistence amidst academic challenges, boosts motivation to engage with difficult content, and facilitates more profound cognitive processing (Bagheri Sheykhangafshe et al., 2024). Students possessing robust self-efficacy are prone to establish more ambitious academic objectives, rebound swiftly from adversities, and judiciously apply efficacious learning strategies, all of which serve as crucial indicators of academic success and holistic well-being (Nielsen et al., 2018).

Complementary to academic self-efficacy, academic self-regulation refers to students’ proactive efforts to manage their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions effectively in pursuit of academic goals. This multifaceted process encompasses various dimensions, including cognitive strategies (e.g. elaboration, organization of information), metacognitive strategies (e.g. planning, monitoring one’s understanding, evaluating learning outcomes), motivational beliefs (e.g. perceiving task value, maintaining positive outcome expectations), and behavioral management (e.g. efficient time allocation, seeking appropriate help) (Nooripour et al., 2022). Highly self-regulated learners demonstrate proficiency in establishing attainable objectives, flexibly adjusting their learning approaches, and sustaining perseverance even when encountering challenges (Jafari et al., 2024). This inherent capacity for self-directed learning is increasingly acknowledged as foundational for successfully navigating complex academic demands and cultivating lifelong learning habits, thereby positioning it as a pivotal focus for contemporary educational interventions (Morosanova et al., 2022).

The swift evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) has notably expanded the landscape of educational support, offering the promise of highly personalized and adaptive learning experiences (Adewale et al., 2024; Dehghani et al., 2025). AI assistants proficiently leverage sophisticated algorithms to deliver immediate feedback, precisely tailor content to individual learning paces, and provide intelligent tutoring capable of adapting to a student’s unique strengths and weaknesses (Looi & Jia, 2025). In this study, the “Monica” AI platform was selected for its evidence-based design, incorporating validated adaptive learning algorithms and immediate feedback mechanisms, which have been shown to enhance engagement and academic outcomes in diverse student populations, including those navigating linguistic challenges (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). Moreover, these platforms can analyze extensive datasets to discern intricate learning patterns, forecast areas of potential difficulty, and recommend highly customized resources, thereby optimizing the overall learning trajectory (Bali et al., 2024). Beyond mere content dissemination, AI tools possess the capacity to significantly augment student engagement through interactive exercises and gamified learning, cultivating a dynamic and nurturing educational environment that addresses individual needs with greater efficacy than conventional methodologies (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024).

Parallel to technological advancements, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy, emphasizes enhancing psychological flexibility via core processes such as acceptance, mindfulness, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, values clarification, and committed action (Akbari et al., 2022). Within academic settings, ACT aims to empower students to respond more effectively to internal experiences (e.g. anxiety, self-doubt) that might impede learning, rather than attempting to eradicate them (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Ebrahimi et al., 2024). By encouraging students to embrace challenging thoughts and feelings, align their behaviors with their fundamental values (e.g. striving for knowledge, personal growth), and engage in purposeful actions, ACT can cultivate heightened resilience, sustained persistence, and sharpened focus (Knight & Samuel, 2022). Specifically, studies like Katajavuori et al. (2023) have demonstrated ACT’s efficacy in promoting university students’ well-being and academic engagement by fostering psychological flexibility, which is particularly relevant for bilingual students facing unique stressors. This therapeutic approach provides students with a robust framework for skillfully navigating academic pressures and steadfastly pursuing meaningful educational goals despite their unique internal struggles (Zarei et al., 2024).

Despite the widely acknowledged importance of academic self-efficacy and self-regulation for all students, there remains a notable paucity of research on effective strategies specifically tailored for bilingual learners, a group confronting distinct challenges. The rationale for this study stems from the need to address the unique academic and psychological challenges faced by bilingual students, particularly in developing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, which are critical for their academic success. Both AI-assisted interventions, such as the “Monica” platform, and ACT-based interventions target these constructs. Still, through distinct mechanisms, AI provides real-time, adaptive academic support to enhance skill mastery and confidence, while ACT fosters psychological flexibility to manage emotional and cognitive barriers to learning. Comparing these approaches is essential to determine which intervention—or combination thereof—best supports bilingual students in overcoming their specific challenges, such as linguistic complexity and cultural adaptation, thereby filling a critical gap in the literature (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). While both AI-powered educational tools and ACT have shown considerable promise in enhancing various psychological and academic outcomes across general populations, their comparative efficacy within a bilingual context, particularly regarding these pivotal academic skills, is not yet well-established. This study addresses this gap by directly comparing the “Monica” AI-assisted intervention with an ACT-based intervention, as both approaches target adaptive learning behaviors and psychological resilience, which are crucial for bilingual students navigating linguistic and cultural complexities. Consequently, a discernible research gap exists concerning which intervention modality offers superior benefits or how these approaches might synergistically address the unique requirements of this student demographic.

Additionally, the role of attention, as a component of engagement, was considered in the design of both interventions, with AI providing interactive feedback to sustain focus and ACT emphasizing mindfulness to enhance students’ attentional control and motivation. Therefore, this study meticulously aimed to directly compare the effectiveness of an AI-assisted intervention and an ACT-based intervention in enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among Persian-Arabic seventh-grade bilingual male students. Through this investigation, the research sought to provide robust empirical evidence to guide the development of more effective and precisely targeted educational interventions for linguistically diverse learners.

Materials and Methods

This study adopted an experimental research design, featuring pre-test, post-test, and a one-month follow-up assessment, in conjunction with a non-equivalent control group. The investigation took place during the academic year 2023-2024. The target population consisted of Persian-Arabic seventh-grade bilingual male students enrolled in public schools across Ahvaz suburban areas, Iran. The selection of suburban schools was intentional, as these areas often have limited access to advanced educational resources, which may contribute to lower academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among students, thus highlighting the need for targeted interventions to support this population’s academic development. Employing a multi-stage cluster sampling method, 105 eligible students were systematically selected and subsequently randomized into three distinct groups: two experimental groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention) and one control group, each comprising 35 participants. Eligibility for participation was contingent upon: enrollment as a seventh-grade male student, self-identification as Persian-Arabic bilingual, submission of informed parental consent and student assent, and no history of formal psychological intervention for academic self-efficacy or self-regulation difficulties. Conversely, students diagnosed with severe learning disabilities or psychiatric disorders, or those missing more than two intervention sessions, were excluded from the study.

Study procedure

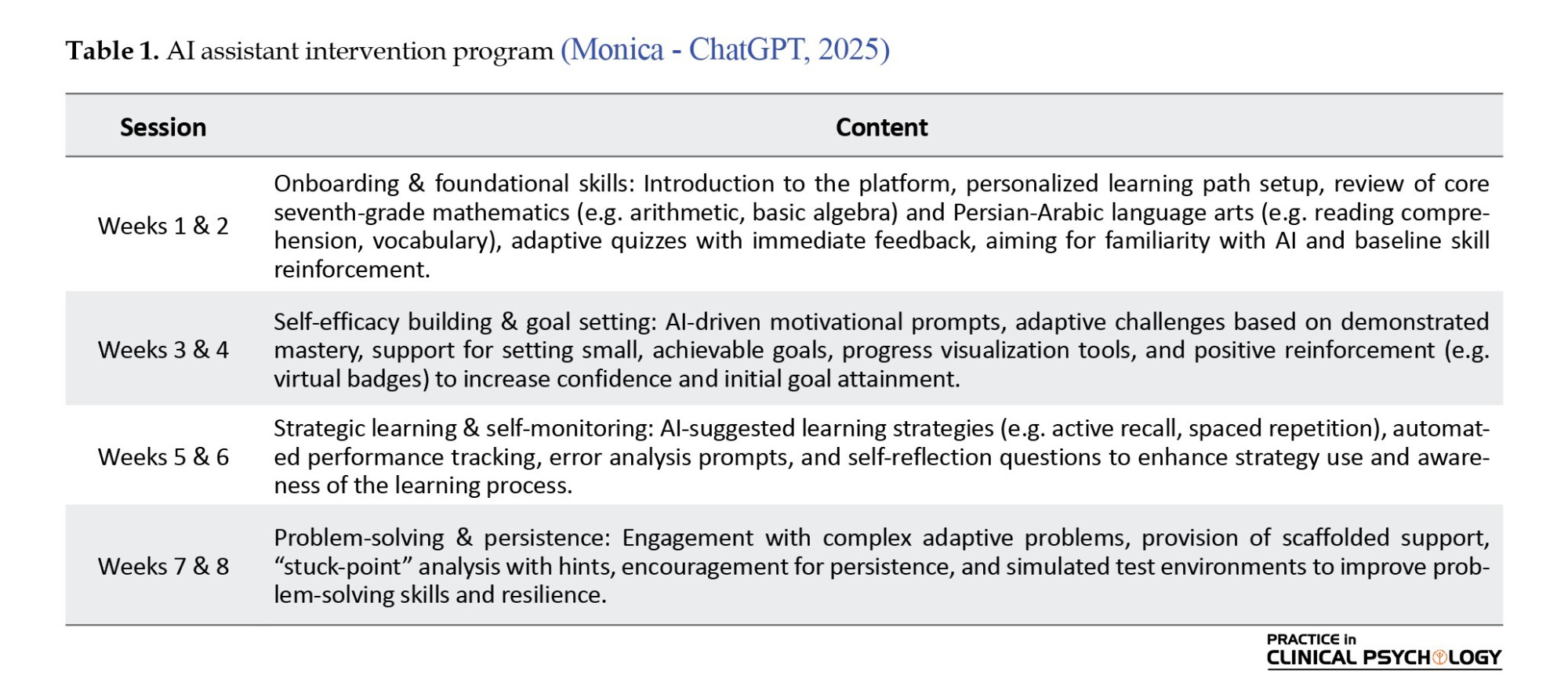

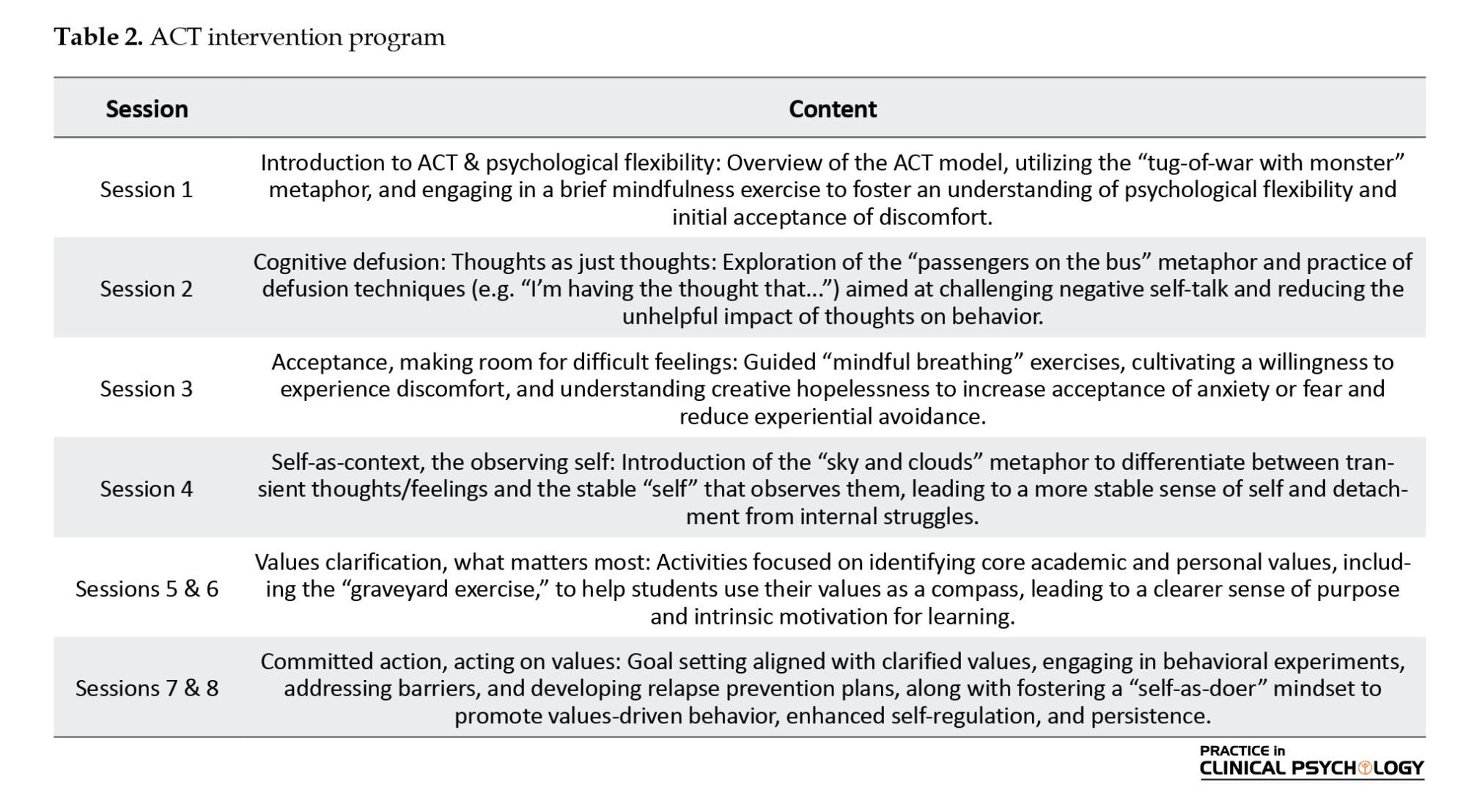

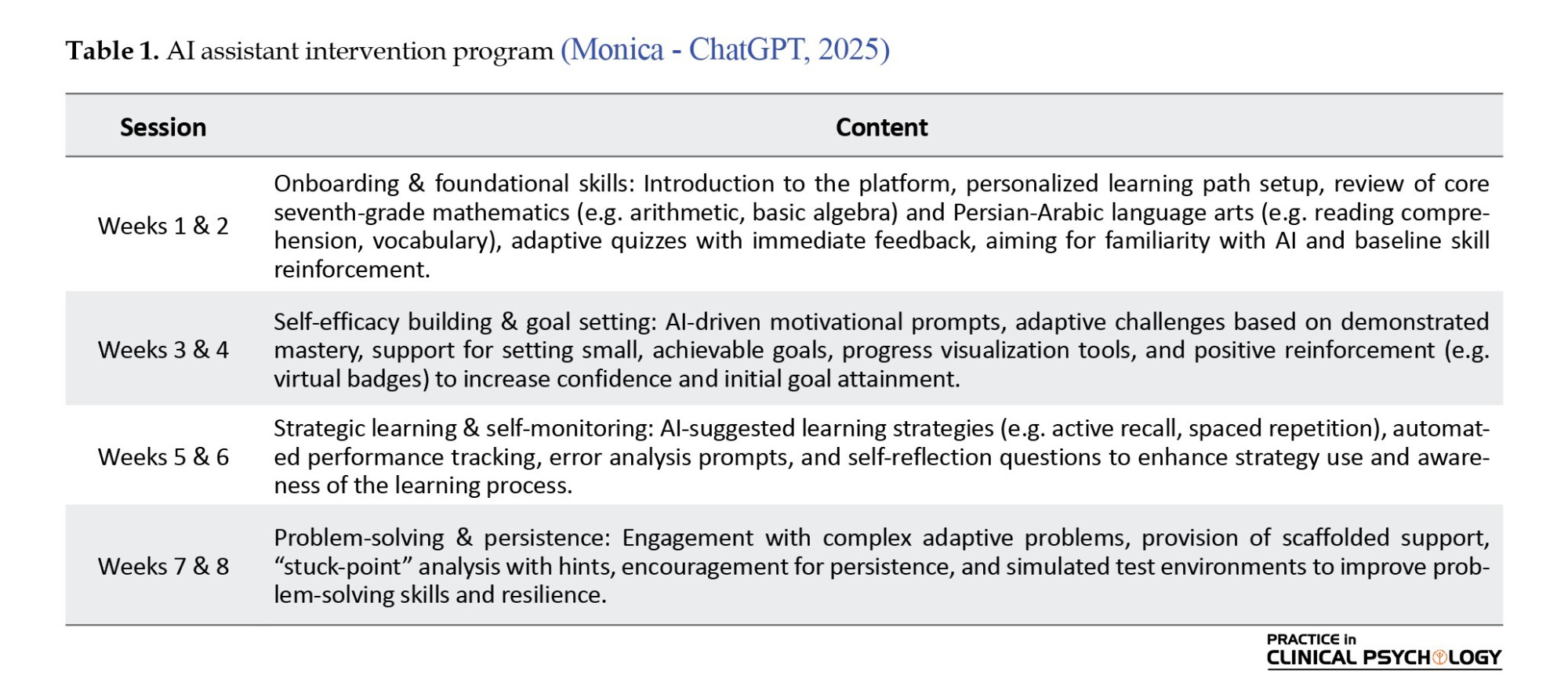

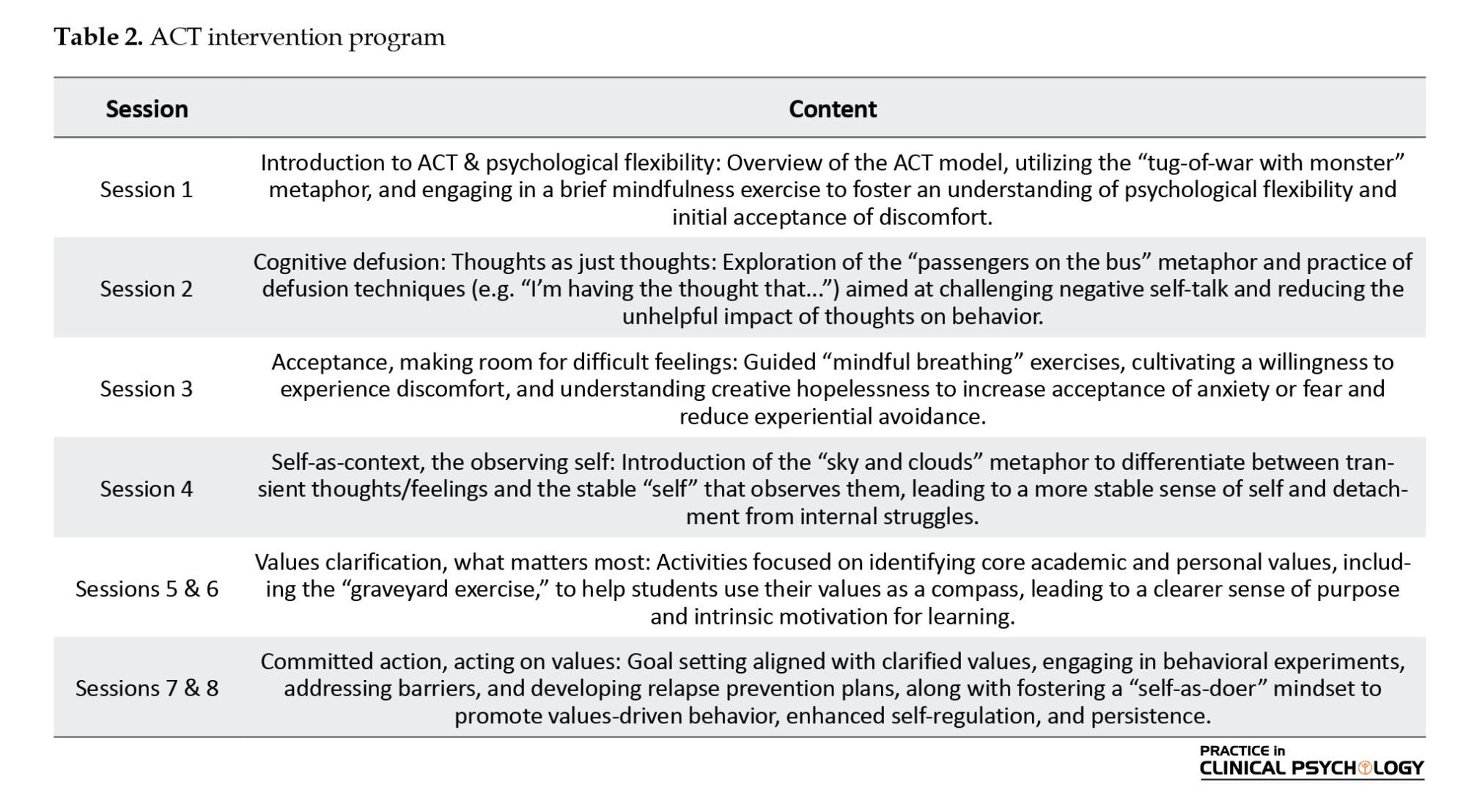

Following ethical approval and requisite permissions from the Ahvaz Education and selected schools, study objectives were delineated to administrators and teachers. Comprehensive information sheets were then provided to prospective participants and their parents, meticulously securing informed parental consent and student assent from all 105 eligible students. All participants completed the initial pre-test battery on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation. After the pre-test, participants were randomly allocated to three groups: Two experimental (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention) and one control. The AI-assisted intervention was designed by a team of educational psychologists and computer scientists at Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, in collaboration with the developers of the “Monica” AI platform to ensure alignment with the academic needs of bilingual students. The experimental groups commenced an 8-week intervention: The AI group engaged with the “Monica” AI platform (45-60 min, 3x/wk), which delivered tailored academic content in mathematics and Persian-Arabic language arts, including interactive lessons, adaptive quizzes, and personalized feedback based on real-time performance analytics to enhance engagement and address individual learning gaps; the ACT group participated in 8 weekly 90-minute sessions facilitated by a trained clinical psychologist (summarized in Tables 1 and 2).

The ACT-based intervention was developed by clinical psychologists specializing in educational applications of ACT, ensuring fidelity to its core principles while tailoring content to the cultural and linguistic context of Persian-Arabic bilingual students. The control group received the standard curriculum—immediately post-intervention, all completed post-tests, followed by a one-month follow-up to assess sustained effects. The “Monica” AI platform’s effectiveness stems from its ability to adapt content delivery to students’ cognitive and emotional needs through machine learning algorithms. These algorithms analyze performance data to provide scaffolded support and motivational prompts, addressing human aspects such as motivation and self-doubt. However, it lacks the empathetic depth of human interaction provided by ACT (Looi & Jia, 2025).

Study instruments

The general academic self-efficacy scale (GASE)

The GASE (Nielsen et al., 2018) is a concise 5-item instrument designed to assess students’ overall perceived confidence in their academic capabilities. Responses are typically rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting greater academic self-efficacy. Despite its brevity, this scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties in various educational contexts. Prior research on similar brief self-efficacy scales has reported acceptable to strong internal consistency, with Cronbach α generally above 0.70 (Farnia et al., 2020). For the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the GASE was found to be 0.89, indicating strong reliability within this sample.

The academic self-regulation scale (ASRS)

The ASRS, developed by Bouffard et al. (1995), was employed to measure academic self-regulation in this study. This 14-item instrument utilizes a 5-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (“does not match me at all”) to 5 (“matches me completely”). The ASRS is structured around three distinct subscales: cognition, metacognition, and motivation. Total scores on the scale can range from 14 to 70, with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of academic self-regulation. Regarding its psychometric properties, Sajjad Bakhtiary et al. (2021) previously reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.90 for the ASRS, indicating good internal consistency reliability. In the present study, the internal consistency reliability was similarly assessed, yielding a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.87, which further affirms its strong reliability within this sample.

Data analysis

Using SPSS software, version 28.0, statistical analyses employed repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess intervention effectiveness on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across time points (pre-test, post-test, follow-up). Also, assumptions were examined. Significant effects were explored via Bonferroni post-hoc tests for pairwise comparisons.

Results

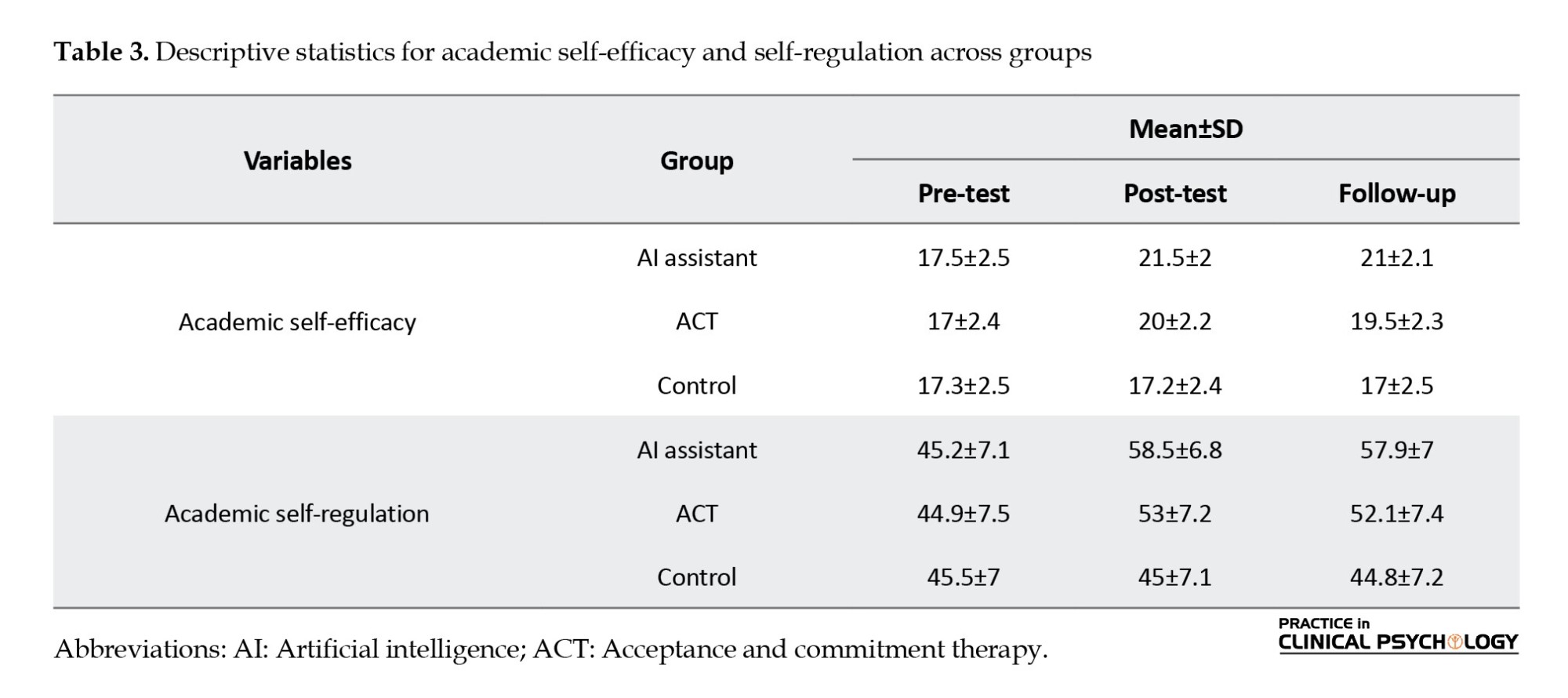

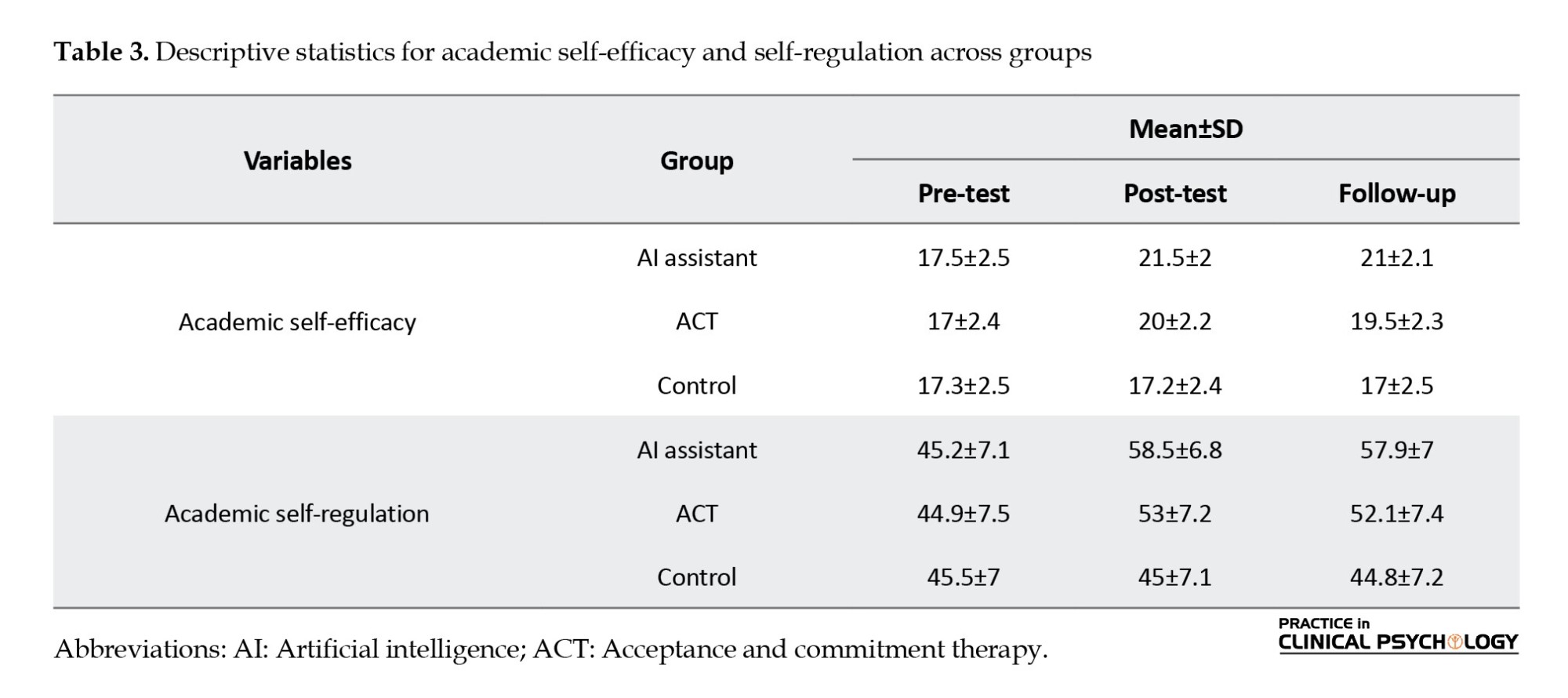

A total of 105 seventh-grade male students Mean±SD 12.8±0.65 years of age formed a demographically homogeneous sample. To confirm baseline equivalence, one-way ANOVA was conducted on pre-test scores for academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across the three groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention, control). For academic self-efficacy, no significant differences were found between groups (F=0.14, P=0.873), with Mean±SD of 17.5±2.5 for AI, 17±2.4 for ACT, and 17.3±2.5 for control. Similarly, for academic self-regulation, no significant differences were observed (F=0.09, P=0.910), with means of 45.2±7.1 for AI, 44.9±7.7 for ACT, and 45.5±7 for control. These results confirm that the groups were comparable at baseline, supporting the validity of subsequent intervention comparisons. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention, control) at pre-test, post-test, and 1-month follow-up. Consistent with randomization, pre-test means were comparable. Post-intervention, experimental groups showed significant increases in scores, largely sustained at follow-up, contrasting with the control group’s lack of substantial change.

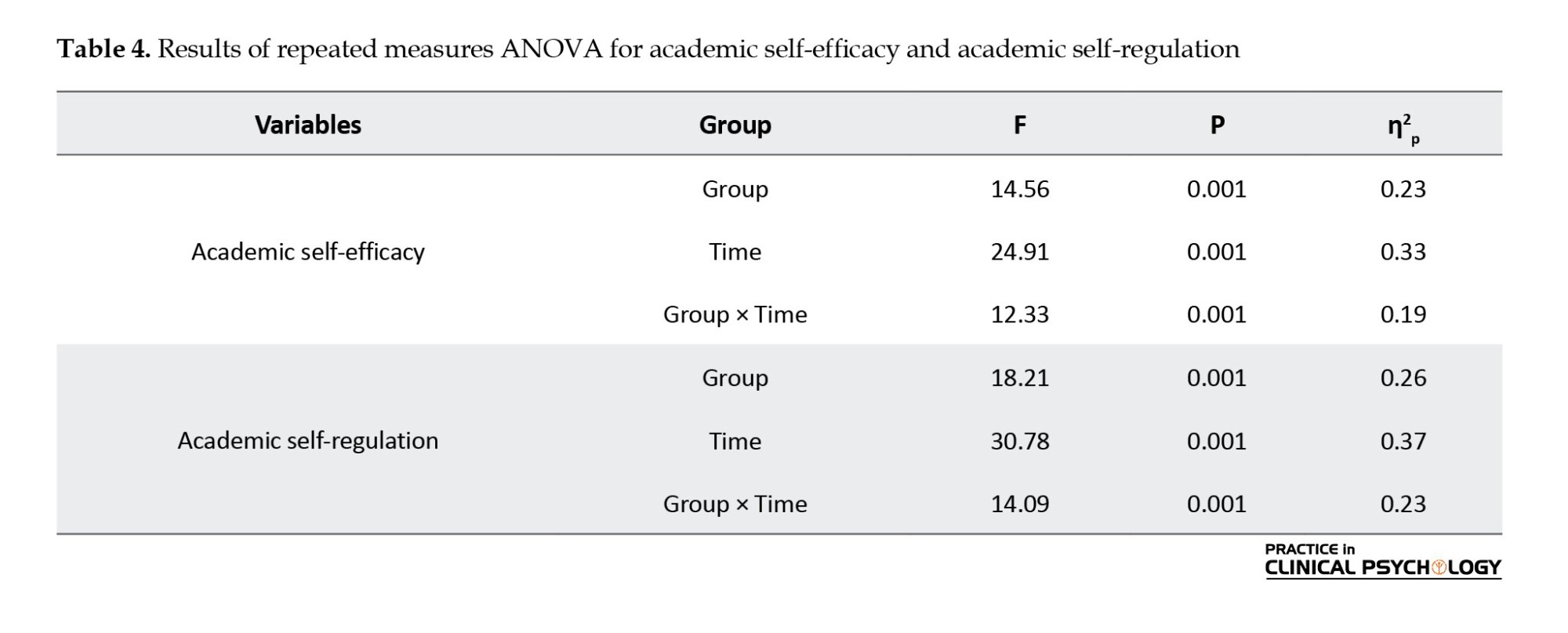

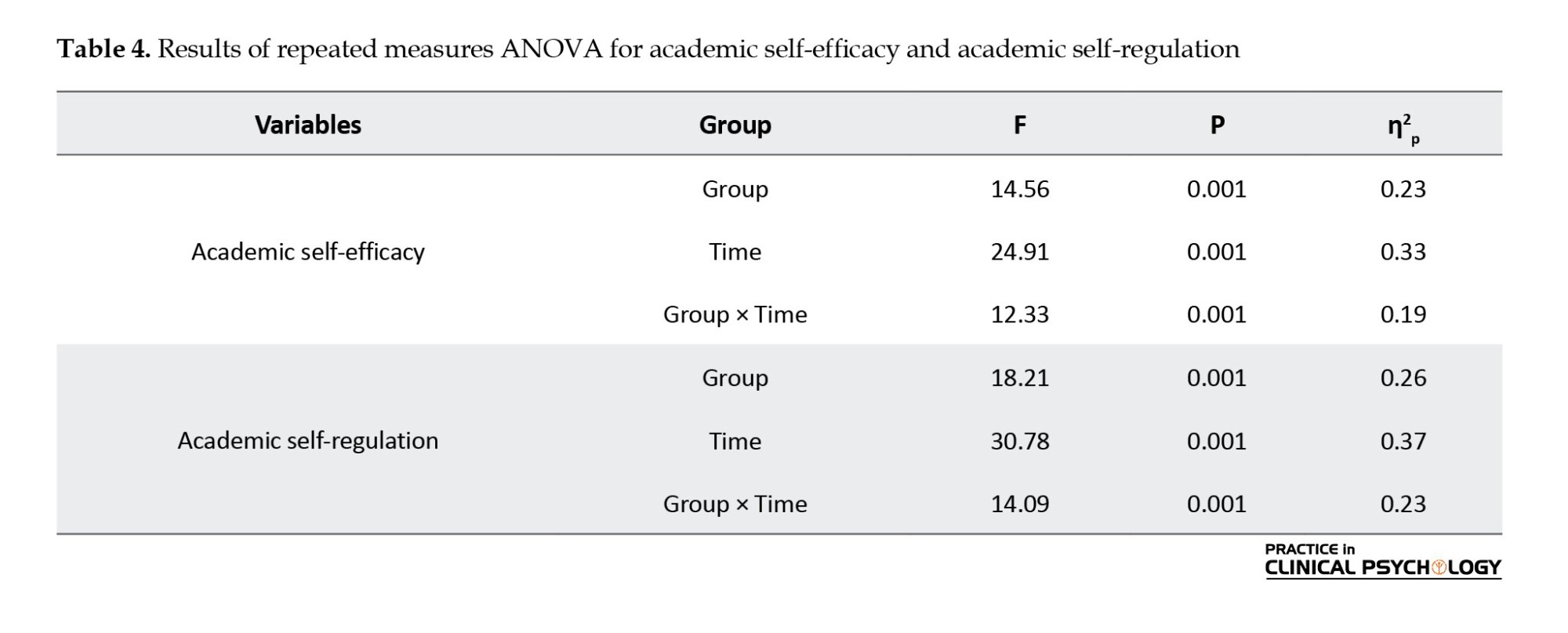

Before repeated measures ANOVA, assumptions were rigorously examined. Normality of academic self-efficacy and self-regulation data (all time points/groups) was assessed via the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and skewness/kurtosis values (±2). These confirmed data approximated a normal distribution, satisfying this crucial statistical assumption. Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of intervention group and time on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation. Mauchly’s test indicated sphericity was met for academic self-efficacy (P>0.05) but violated for self-regulation (P<0.05), for which Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. As detailed in Table 4, significant main effects were found for group (academic self-efficacy: F=12.56, P<0.0001; academic self-regulation: F=18.21, P<0.001) and time (academic self-efficacy: F=28.91, P<0.001; academic self-regulation: F=35.78, P<0.001). Crucially, a statistically significant group × time interaction emerged for both academic self-efficacy (F=10.33, P<0.001) and academic self-regulation (F=14.89, P<0.001), indicating differential changes in these variables across groups over time, necessitating further post-hoc investigation.

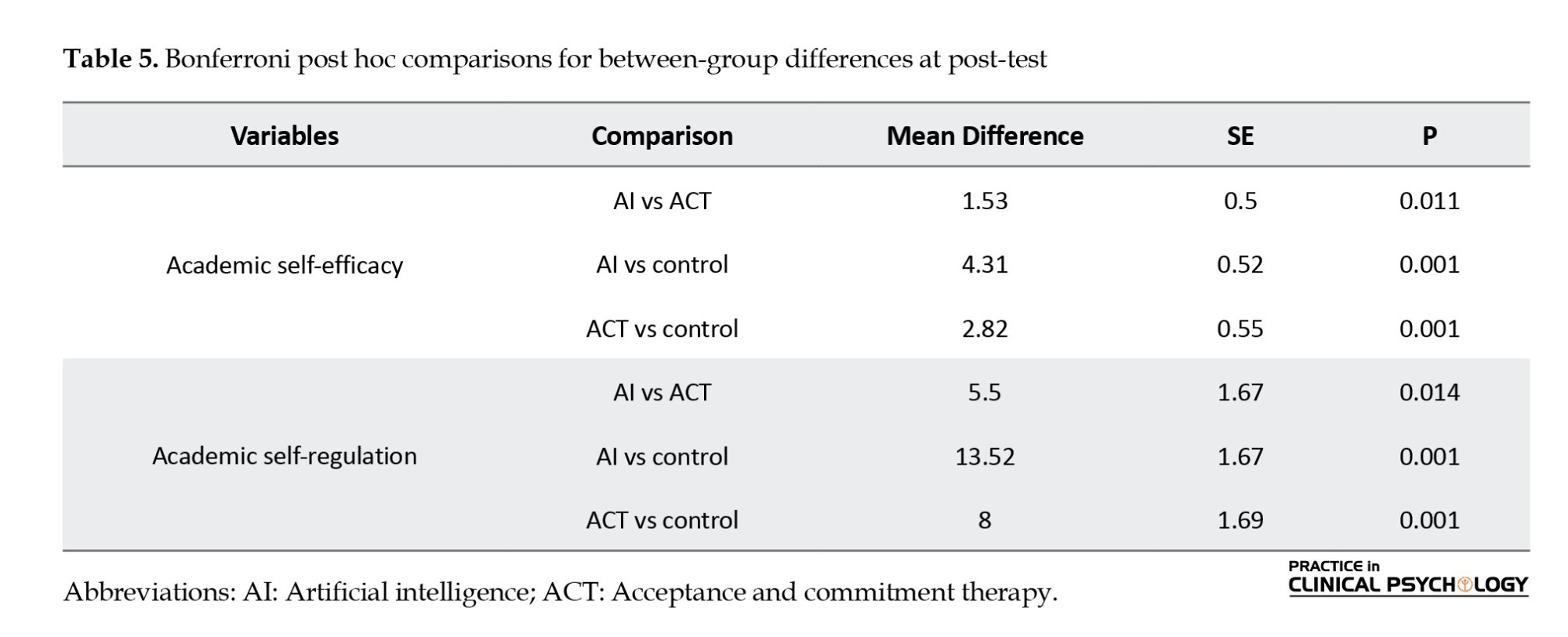

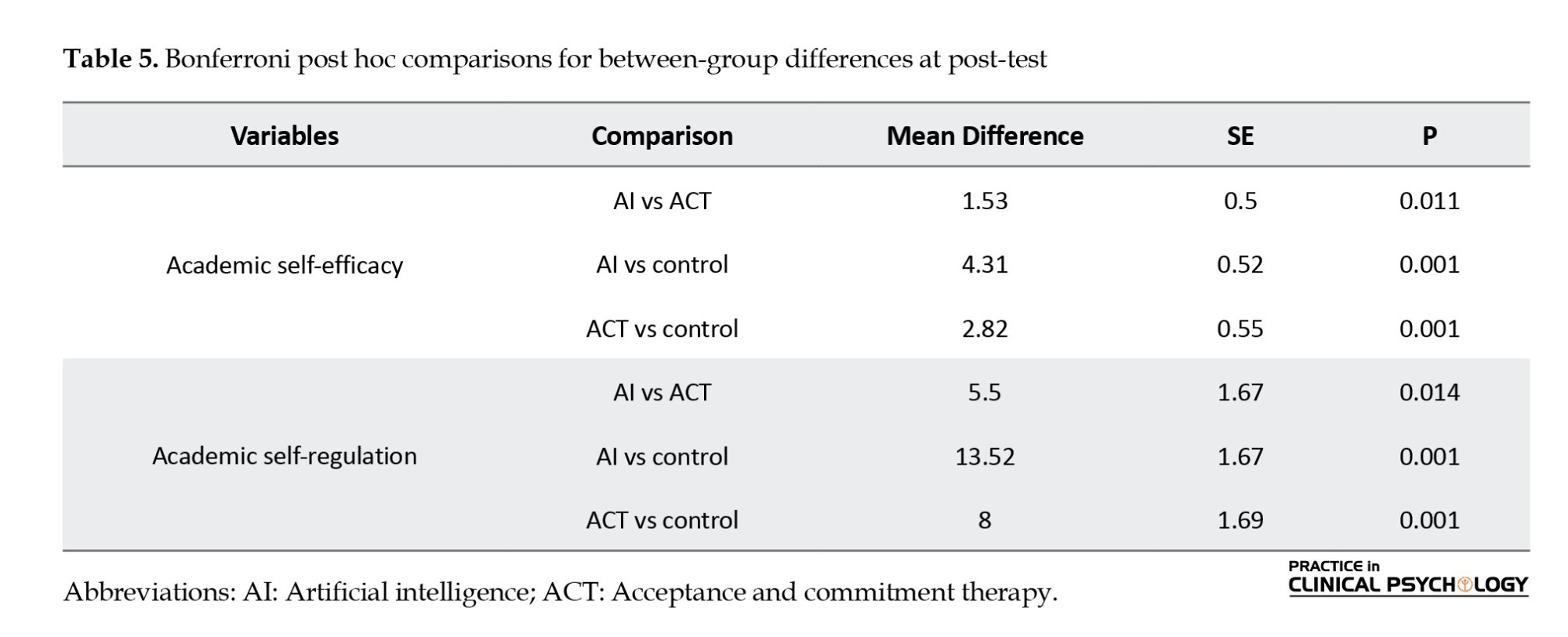

Table 5, detailing Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons at post-test, revealed significant between-group differences in academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among students. For self-efficacy, the AI assistant group significantly surpassed both ACT (mean difference=1.53, P<0.011) and control (mean difference=4.31, P<0.001) groups, with ACT also outperforming control (mean difference=2.82, P<0.001). In self-regulation, the AI Assistant showed a significant improvement over ACT (mean difference=5.50, P<0.014) and control (mean difference=13.52, P<0.001), while ACT surpassed control (mean difference=8.00, P<0.001). These results indicate both interventions were superior to control, with the AI Assistant showing stronger immediate effects than ACT alone.

Discussion

The present study investigated the comparative effectiveness of an AI-assisted intervention and an ACT-based intervention in enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among seventh-grade bilingual male students. Findings unequivocally demonstrated that both interventions significantly enhanced these competencies from pre-test to post-test, with substantial gains largely sustained at a 1-month follow-up—a trajectory distinctly absent in the control group. Notably, the AI-assisted intervention consistently yielded superior outcomes compared to the ACT-based intervention, and both interventions significantly surpassed the conventional schooling received by the control group. The efficacy of the AI-assisted intervention, utilizing the “Monica” platform, is grounded in its sophisticated machine learning algorithms that deliver highly personalized and adaptive learning experiences tailored to individual student needs (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). Specifically, the platform employs real-time performance analytics to provide immediate feedback, adaptive quizzes, and motivational prompts, which are designed to enhance academic self-efficacy by reinforcing mastery experiences and fostering a sense of accomplishment (Bandura et al., 1996). For self-regulation, the AI’s features, such as progress visualization tools and error analysis prompts, support metacognitive strategies like self-monitoring and goal-setting, enabling students to adjust their learning approaches strategically (Tanveer et al., 2024). However, while the AI excels in providing structured, data-driven support, its capacity to address the nuanced emotional and psychological dimensions of human learners, such as empathy or deep emotional understanding, is inherently limited compared to human-led interventions like ACT. This limitation may explain why, despite its superior outcomes, the AI intervention may not fully capture the emotional complexities of bilingual students navigating linguistic and cultural challenges (Looi & Jia, 2025). These mechanisms likely facilitated sustained engagement and skill development beyond what typical traditional classroom settings can offer.

Concurrently, the significant improvements in academic self-efficacy and self-regulation observed within the ACT-based intervention group are highly consistent with the established application of third-wave behavioral therapies in educational contexts (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Knight & Samuel, 2022; Zarei et al., 2024). ACT’s core processes, encompassing psychological flexibility, mindfulness, and value-driven action, equip students with potent internal tools to effectively navigate the inherent challenges of academic life. By fostering the acceptance of difficult internal experiences—such as self-doubt or anxiety—rather than promoting struggle or avoidance, ACT can notably attenuate their disruptive impact on cognitive functioning and performance, thereby indirectly bolstering self-efficacy. Furthermore, teaching cognitive defusion from unhelpful thoughts and encouraging committed action aligned with personal academic values directly cultivates a more adaptive and resilient approach to self-regulated learning (Knight & Samuel, 2022). For instance, Knight and Samuel (2022) found that ACT interventions in secondary schools improved students’ academic engagement and well-being by fostering psychological flexibility, a finding mirrored in our study’s outcomes for bilingual students. Similarly, Katajavuori et al. (2023) demonstrated that ACT-based interventions enhanced university students’ self-regulation and academic motivation, supporting the applicability of ACT in addressing academic challenges in diverse educational settings. The structured yet experiential nature of the ACT-based intervention likely provided a supportive environment for students to internalize and practice these novel psychological skills, contributing substantially to their improved academic outcomes.

The finding that the AI-assisted intervention yielded stronger outcomes than the ACT-based intervention, with both proving superior to the control condition, offers compelling insights for educational practice. The AI-assisted intervention’s direct, highly interactive, and immediately responsive design likely provided more explicit and consistent opportunities for the acquisition and reinforcement of specific academic skills (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2025). In contrast, the ACT-based intervention empowers students with broader psychological capacities to manage their learning process. Meanwhile, the AI’s real-time, data-driven approach directly targets skill development and confidence-building in academic tasks, which may be particularly effective for bilingual students requiring structured support to navigate linguistic complexities. This finding suggests a valuable distinction: AI may offer a more direct pathway for immediate behavioral and belief shifts, whereas ACT cultivates a more foundational psychological resilience crucial for sustained well-being. Collectively, these findings underscore the critical need for targeted, evidence-based interventions to foster academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, especially for populations like bilingual students who may navigate additional linguistic and cultural complexities in their educational journey.

These results significantly advance theoretical understandings of self-regulated learning, underscoring that both external, adaptive instructional support and internal psychological flexibility are crucial for comprehensive student development. Consequently, future theoretical models ought to explicitly consider the dynamic interplay between these two distinct pathways. Despite these contributions, the present study is subject to several limitations. The relatively short 1-month follow-up, while indicative, restricts definitive conclusions regarding the long-term sustainability of the observed effects. Furthermore, the sample’s specificity, comprising exclusively seventh-grade bilingual male students from a particular region, inherently limits the generalizability of these findings to other age groups, genders, or diverse linguistic and cultural contexts. Reliance on self-report measures, though a common practice, may also introduce inherent response biases. Therefore, future research should endeavor to explore long-term effects through extended follow-up periods. Investigating the nuanced mechanisms of change via qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide deeper insights into students’ subjective experiences. Expanding studies to explore how AI interventions can be enhanced to better address the emotional and psychological nuances of human learners, possibly by integrating elements of psychological interventions like ACT, represents a promising direction for advancing research in this critical area.

Conclusion

This study conclusively demonstrates the efficacy of both AI assistant intervention and ACT in significantly enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among seventh-grade bilingual male students. While both interventional approaches yielded sustained positive improvements compared to conventional schooling, the AI assistant consistently proved to be the more effective intervention. These findings collectively underscore the critical importance of targeted, evidence-based educational supports. The findings suggest that technology-enhanced adaptive learning, alongside training in psychological flexibility, offers promising avenues for fostering essential academic competencies, particularly within populations like bilingual students, thereby contributing valuable insights to both current educational practice and future intervention design.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.397).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing the original draft: Khaled Loveimi; Methodology: Khaled Loveimi and Sasan Bavi; Review and editing: Investigation and data curation: Reza Johari Fard; Supervision: Sasan Bavi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students, parents, and school administrators of the Ahvaz public schools for their cooperation and participation.

References

Bilingual students constitute a significant and expanding demographic within global educational systems. However, they frequently navigate a unique landscape of academic challenges that can profoundly influence their learning trajectories (Gao & Yang, 2023). Beyond the inherent complexities of mastering multiple languages, these students often contend with issues such as increased cognitive load, cultural identity conflicts, and disparities in pedagogical expectations across linguistic contexts (Ulum, 2024). These multifaceted challenges can manifest as difficulties in academic comprehension, effective communication, and the crucial development of adaptive learning strategies. As a result, bilingual learners may experience elevated academic stress and lessened self-perceptions of their capabilities; they struggle in independently managing their learning processes (Moradpour & Bavi, 2025). Moreover, students in suburban areas, such as those in Ahvaz City, Iran may face additional barriers due to limited access to educational resources, potentially exacerbating challenges in developing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, which are critical for academic success. Addressing these distinct vulnerabilities is imperative to ensure their successful integration and optimal academic progression within diverse educational environments.

Academic self-efficacy, a pivotal construct within Bandura’s (1996) social cognitive theory, denotes an individual’s conviction in their capability to execute academic tasks successfully. This belief extends beyond mere skill possession to encompass confidence in one’s capacity to deploy those skills to attain specific learning outcomes effectively (Cabras et al., 2024). Elevated academic self-efficacy promotes enhanced persistence amidst academic challenges, boosts motivation to engage with difficult content, and facilitates more profound cognitive processing (Bagheri Sheykhangafshe et al., 2024). Students possessing robust self-efficacy are prone to establish more ambitious academic objectives, rebound swiftly from adversities, and judiciously apply efficacious learning strategies, all of which serve as crucial indicators of academic success and holistic well-being (Nielsen et al., 2018).

Complementary to academic self-efficacy, academic self-regulation refers to students’ proactive efforts to manage their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions effectively in pursuit of academic goals. This multifaceted process encompasses various dimensions, including cognitive strategies (e.g. elaboration, organization of information), metacognitive strategies (e.g. planning, monitoring one’s understanding, evaluating learning outcomes), motivational beliefs (e.g. perceiving task value, maintaining positive outcome expectations), and behavioral management (e.g. efficient time allocation, seeking appropriate help) (Nooripour et al., 2022). Highly self-regulated learners demonstrate proficiency in establishing attainable objectives, flexibly adjusting their learning approaches, and sustaining perseverance even when encountering challenges (Jafari et al., 2024). This inherent capacity for self-directed learning is increasingly acknowledged as foundational for successfully navigating complex academic demands and cultivating lifelong learning habits, thereby positioning it as a pivotal focus for contemporary educational interventions (Morosanova et al., 2022).

The swift evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) has notably expanded the landscape of educational support, offering the promise of highly personalized and adaptive learning experiences (Adewale et al., 2024; Dehghani et al., 2025). AI assistants proficiently leverage sophisticated algorithms to deliver immediate feedback, precisely tailor content to individual learning paces, and provide intelligent tutoring capable of adapting to a student’s unique strengths and weaknesses (Looi & Jia, 2025). In this study, the “Monica” AI platform was selected for its evidence-based design, incorporating validated adaptive learning algorithms and immediate feedback mechanisms, which have been shown to enhance engagement and academic outcomes in diverse student populations, including those navigating linguistic challenges (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). Moreover, these platforms can analyze extensive datasets to discern intricate learning patterns, forecast areas of potential difficulty, and recommend highly customized resources, thereby optimizing the overall learning trajectory (Bali et al., 2024). Beyond mere content dissemination, AI tools possess the capacity to significantly augment student engagement through interactive exercises and gamified learning, cultivating a dynamic and nurturing educational environment that addresses individual needs with greater efficacy than conventional methodologies (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024).

Parallel to technological advancements, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy, emphasizes enhancing psychological flexibility via core processes such as acceptance, mindfulness, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, values clarification, and committed action (Akbari et al., 2022). Within academic settings, ACT aims to empower students to respond more effectively to internal experiences (e.g. anxiety, self-doubt) that might impede learning, rather than attempting to eradicate them (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Ebrahimi et al., 2024). By encouraging students to embrace challenging thoughts and feelings, align their behaviors with their fundamental values (e.g. striving for knowledge, personal growth), and engage in purposeful actions, ACT can cultivate heightened resilience, sustained persistence, and sharpened focus (Knight & Samuel, 2022). Specifically, studies like Katajavuori et al. (2023) have demonstrated ACT’s efficacy in promoting university students’ well-being and academic engagement by fostering psychological flexibility, which is particularly relevant for bilingual students facing unique stressors. This therapeutic approach provides students with a robust framework for skillfully navigating academic pressures and steadfastly pursuing meaningful educational goals despite their unique internal struggles (Zarei et al., 2024).

Despite the widely acknowledged importance of academic self-efficacy and self-regulation for all students, there remains a notable paucity of research on effective strategies specifically tailored for bilingual learners, a group confronting distinct challenges. The rationale for this study stems from the need to address the unique academic and psychological challenges faced by bilingual students, particularly in developing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, which are critical for their academic success. Both AI-assisted interventions, such as the “Monica” platform, and ACT-based interventions target these constructs. Still, through distinct mechanisms, AI provides real-time, adaptive academic support to enhance skill mastery and confidence, while ACT fosters psychological flexibility to manage emotional and cognitive barriers to learning. Comparing these approaches is essential to determine which intervention—or combination thereof—best supports bilingual students in overcoming their specific challenges, such as linguistic complexity and cultural adaptation, thereby filling a critical gap in the literature (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). While both AI-powered educational tools and ACT have shown considerable promise in enhancing various psychological and academic outcomes across general populations, their comparative efficacy within a bilingual context, particularly regarding these pivotal academic skills, is not yet well-established. This study addresses this gap by directly comparing the “Monica” AI-assisted intervention with an ACT-based intervention, as both approaches target adaptive learning behaviors and psychological resilience, which are crucial for bilingual students navigating linguistic and cultural complexities. Consequently, a discernible research gap exists concerning which intervention modality offers superior benefits or how these approaches might synergistically address the unique requirements of this student demographic.

Additionally, the role of attention, as a component of engagement, was considered in the design of both interventions, with AI providing interactive feedback to sustain focus and ACT emphasizing mindfulness to enhance students’ attentional control and motivation. Therefore, this study meticulously aimed to directly compare the effectiveness of an AI-assisted intervention and an ACT-based intervention in enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among Persian-Arabic seventh-grade bilingual male students. Through this investigation, the research sought to provide robust empirical evidence to guide the development of more effective and precisely targeted educational interventions for linguistically diverse learners.

Materials and Methods

This study adopted an experimental research design, featuring pre-test, post-test, and a one-month follow-up assessment, in conjunction with a non-equivalent control group. The investigation took place during the academic year 2023-2024. The target population consisted of Persian-Arabic seventh-grade bilingual male students enrolled in public schools across Ahvaz suburban areas, Iran. The selection of suburban schools was intentional, as these areas often have limited access to advanced educational resources, which may contribute to lower academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among students, thus highlighting the need for targeted interventions to support this population’s academic development. Employing a multi-stage cluster sampling method, 105 eligible students were systematically selected and subsequently randomized into three distinct groups: two experimental groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention) and one control group, each comprising 35 participants. Eligibility for participation was contingent upon: enrollment as a seventh-grade male student, self-identification as Persian-Arabic bilingual, submission of informed parental consent and student assent, and no history of formal psychological intervention for academic self-efficacy or self-regulation difficulties. Conversely, students diagnosed with severe learning disabilities or psychiatric disorders, or those missing more than two intervention sessions, were excluded from the study.

Study procedure

Following ethical approval and requisite permissions from the Ahvaz Education and selected schools, study objectives were delineated to administrators and teachers. Comprehensive information sheets were then provided to prospective participants and their parents, meticulously securing informed parental consent and student assent from all 105 eligible students. All participants completed the initial pre-test battery on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation. After the pre-test, participants were randomly allocated to three groups: Two experimental (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention) and one control. The AI-assisted intervention was designed by a team of educational psychologists and computer scientists at Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, in collaboration with the developers of the “Monica” AI platform to ensure alignment with the academic needs of bilingual students. The experimental groups commenced an 8-week intervention: The AI group engaged with the “Monica” AI platform (45-60 min, 3x/wk), which delivered tailored academic content in mathematics and Persian-Arabic language arts, including interactive lessons, adaptive quizzes, and personalized feedback based on real-time performance analytics to enhance engagement and address individual learning gaps; the ACT group participated in 8 weekly 90-minute sessions facilitated by a trained clinical psychologist (summarized in Tables 1 and 2).

The ACT-based intervention was developed by clinical psychologists specializing in educational applications of ACT, ensuring fidelity to its core principles while tailoring content to the cultural and linguistic context of Persian-Arabic bilingual students. The control group received the standard curriculum—immediately post-intervention, all completed post-tests, followed by a one-month follow-up to assess sustained effects. The “Monica” AI platform’s effectiveness stems from its ability to adapt content delivery to students’ cognitive and emotional needs through machine learning algorithms. These algorithms analyze performance data to provide scaffolded support and motivational prompts, addressing human aspects such as motivation and self-doubt. However, it lacks the empathetic depth of human interaction provided by ACT (Looi & Jia, 2025).

Study instruments

The general academic self-efficacy scale (GASE)

The GASE (Nielsen et al., 2018) is a concise 5-item instrument designed to assess students’ overall perceived confidence in their academic capabilities. Responses are typically rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting greater academic self-efficacy. Despite its brevity, this scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties in various educational contexts. Prior research on similar brief self-efficacy scales has reported acceptable to strong internal consistency, with Cronbach α generally above 0.70 (Farnia et al., 2020). For the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the GASE was found to be 0.89, indicating strong reliability within this sample.

The academic self-regulation scale (ASRS)

The ASRS, developed by Bouffard et al. (1995), was employed to measure academic self-regulation in this study. This 14-item instrument utilizes a 5-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (“does not match me at all”) to 5 (“matches me completely”). The ASRS is structured around three distinct subscales: cognition, metacognition, and motivation. Total scores on the scale can range from 14 to 70, with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of academic self-regulation. Regarding its psychometric properties, Sajjad Bakhtiary et al. (2021) previously reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.90 for the ASRS, indicating good internal consistency reliability. In the present study, the internal consistency reliability was similarly assessed, yielding a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.87, which further affirms its strong reliability within this sample.

Data analysis

Using SPSS software, version 28.0, statistical analyses employed repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess intervention effectiveness on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across time points (pre-test, post-test, follow-up). Also, assumptions were examined. Significant effects were explored via Bonferroni post-hoc tests for pairwise comparisons.

Results

A total of 105 seventh-grade male students Mean±SD 12.8±0.65 years of age formed a demographically homogeneous sample. To confirm baseline equivalence, one-way ANOVA was conducted on pre-test scores for academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across the three groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention, control). For academic self-efficacy, no significant differences were found between groups (F=0.14, P=0.873), with Mean±SD of 17.5±2.5 for AI, 17±2.4 for ACT, and 17.3±2.5 for control. Similarly, for academic self-regulation, no significant differences were observed (F=0.09, P=0.910), with means of 45.2±7.1 for AI, 44.9±7.7 for ACT, and 45.5±7 for control. These results confirm that the groups were comparable at baseline, supporting the validity of subsequent intervention comparisons. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for academic self-efficacy and self-regulation across groups (AI-assisted intervention, ACT-based intervention, control) at pre-test, post-test, and 1-month follow-up. Consistent with randomization, pre-test means were comparable. Post-intervention, experimental groups showed significant increases in scores, largely sustained at follow-up, contrasting with the control group’s lack of substantial change.

Before repeated measures ANOVA, assumptions were rigorously examined. Normality of academic self-efficacy and self-regulation data (all time points/groups) was assessed via the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and skewness/kurtosis values (±2). These confirmed data approximated a normal distribution, satisfying this crucial statistical assumption. Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of intervention group and time on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation. Mauchly’s test indicated sphericity was met for academic self-efficacy (P>0.05) but violated for self-regulation (P<0.05), for which Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. As detailed in Table 4, significant main effects were found for group (academic self-efficacy: F=12.56, P<0.0001; academic self-regulation: F=18.21, P<0.001) and time (academic self-efficacy: F=28.91, P<0.001; academic self-regulation: F=35.78, P<0.001). Crucially, a statistically significant group × time interaction emerged for both academic self-efficacy (F=10.33, P<0.001) and academic self-regulation (F=14.89, P<0.001), indicating differential changes in these variables across groups over time, necessitating further post-hoc investigation.

Table 5, detailing Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons at post-test, revealed significant between-group differences in academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among students. For self-efficacy, the AI assistant group significantly surpassed both ACT (mean difference=1.53, P<0.011) and control (mean difference=4.31, P<0.001) groups, with ACT also outperforming control (mean difference=2.82, P<0.001). In self-regulation, the AI Assistant showed a significant improvement over ACT (mean difference=5.50, P<0.014) and control (mean difference=13.52, P<0.001), while ACT surpassed control (mean difference=8.00, P<0.001). These results indicate both interventions were superior to control, with the AI Assistant showing stronger immediate effects than ACT alone.

Discussion

The present study investigated the comparative effectiveness of an AI-assisted intervention and an ACT-based intervention in enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among seventh-grade bilingual male students. Findings unequivocally demonstrated that both interventions significantly enhanced these competencies from pre-test to post-test, with substantial gains largely sustained at a 1-month follow-up—a trajectory distinctly absent in the control group. Notably, the AI-assisted intervention consistently yielded superior outcomes compared to the ACT-based intervention, and both interventions significantly surpassed the conventional schooling received by the control group. The efficacy of the AI-assisted intervention, utilizing the “Monica” platform, is grounded in its sophisticated machine learning algorithms that deliver highly personalized and adaptive learning experiences tailored to individual student needs (Rahiman & Kodikal, 2024). Specifically, the platform employs real-time performance analytics to provide immediate feedback, adaptive quizzes, and motivational prompts, which are designed to enhance academic self-efficacy by reinforcing mastery experiences and fostering a sense of accomplishment (Bandura et al., 1996). For self-regulation, the AI’s features, such as progress visualization tools and error analysis prompts, support metacognitive strategies like self-monitoring and goal-setting, enabling students to adjust their learning approaches strategically (Tanveer et al., 2024). However, while the AI excels in providing structured, data-driven support, its capacity to address the nuanced emotional and psychological dimensions of human learners, such as empathy or deep emotional understanding, is inherently limited compared to human-led interventions like ACT. This limitation may explain why, despite its superior outcomes, the AI intervention may not fully capture the emotional complexities of bilingual students navigating linguistic and cultural challenges (Looi & Jia, 2025). These mechanisms likely facilitated sustained engagement and skill development beyond what typical traditional classroom settings can offer.

Concurrently, the significant improvements in academic self-efficacy and self-regulation observed within the ACT-based intervention group are highly consistent with the established application of third-wave behavioral therapies in educational contexts (Katajavuori et al., 2023; Knight & Samuel, 2022; Zarei et al., 2024). ACT’s core processes, encompassing psychological flexibility, mindfulness, and value-driven action, equip students with potent internal tools to effectively navigate the inherent challenges of academic life. By fostering the acceptance of difficult internal experiences—such as self-doubt or anxiety—rather than promoting struggle or avoidance, ACT can notably attenuate their disruptive impact on cognitive functioning and performance, thereby indirectly bolstering self-efficacy. Furthermore, teaching cognitive defusion from unhelpful thoughts and encouraging committed action aligned with personal academic values directly cultivates a more adaptive and resilient approach to self-regulated learning (Knight & Samuel, 2022). For instance, Knight and Samuel (2022) found that ACT interventions in secondary schools improved students’ academic engagement and well-being by fostering psychological flexibility, a finding mirrored in our study’s outcomes for bilingual students. Similarly, Katajavuori et al. (2023) demonstrated that ACT-based interventions enhanced university students’ self-regulation and academic motivation, supporting the applicability of ACT in addressing academic challenges in diverse educational settings. The structured yet experiential nature of the ACT-based intervention likely provided a supportive environment for students to internalize and practice these novel psychological skills, contributing substantially to their improved academic outcomes.

The finding that the AI-assisted intervention yielded stronger outcomes than the ACT-based intervention, with both proving superior to the control condition, offers compelling insights for educational practice. The AI-assisted intervention’s direct, highly interactive, and immediately responsive design likely provided more explicit and consistent opportunities for the acquisition and reinforcement of specific academic skills (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2025). In contrast, the ACT-based intervention empowers students with broader psychological capacities to manage their learning process. Meanwhile, the AI’s real-time, data-driven approach directly targets skill development and confidence-building in academic tasks, which may be particularly effective for bilingual students requiring structured support to navigate linguistic complexities. This finding suggests a valuable distinction: AI may offer a more direct pathway for immediate behavioral and belief shifts, whereas ACT cultivates a more foundational psychological resilience crucial for sustained well-being. Collectively, these findings underscore the critical need for targeted, evidence-based interventions to foster academic self-efficacy and self-regulation, especially for populations like bilingual students who may navigate additional linguistic and cultural complexities in their educational journey.

These results significantly advance theoretical understandings of self-regulated learning, underscoring that both external, adaptive instructional support and internal psychological flexibility are crucial for comprehensive student development. Consequently, future theoretical models ought to explicitly consider the dynamic interplay between these two distinct pathways. Despite these contributions, the present study is subject to several limitations. The relatively short 1-month follow-up, while indicative, restricts definitive conclusions regarding the long-term sustainability of the observed effects. Furthermore, the sample’s specificity, comprising exclusively seventh-grade bilingual male students from a particular region, inherently limits the generalizability of these findings to other age groups, genders, or diverse linguistic and cultural contexts. Reliance on self-report measures, though a common practice, may also introduce inherent response biases. Therefore, future research should endeavor to explore long-term effects through extended follow-up periods. Investigating the nuanced mechanisms of change via qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide deeper insights into students’ subjective experiences. Expanding studies to explore how AI interventions can be enhanced to better address the emotional and psychological nuances of human learners, possibly by integrating elements of psychological interventions like ACT, represents a promising direction for advancing research in this critical area.

Conclusion

This study conclusively demonstrates the efficacy of both AI assistant intervention and ACT in significantly enhancing academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among seventh-grade bilingual male students. While both interventional approaches yielded sustained positive improvements compared to conventional schooling, the AI assistant consistently proved to be the more effective intervention. These findings collectively underscore the critical importance of targeted, evidence-based educational supports. The findings suggest that technology-enhanced adaptive learning, alongside training in psychological flexibility, offers promising avenues for fostering essential academic competencies, particularly within populations like bilingual students, thereby contributing valuable insights to both current educational practice and future intervention design.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.397).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing the original draft: Khaled Loveimi; Methodology: Khaled Loveimi and Sasan Bavi; Review and editing: Investigation and data curation: Reza Johari Fard; Supervision: Sasan Bavi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students, parents, and school administrators of the Ahvaz public schools for their cooperation and participation.

References

Acosta-Enriquez, B. G., Arbulu Ballesteros, M., Vilcapoma Pérez, C. R., Huamaní Jordan, O., Martin Vergara, J. A., Martel Acosta, R., et al. (2025). AI in academia: How do social influence, self-efficacy, and integrity influence researchers’ use of AI models? Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101274. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101274]

Adewale, M. D., Azeta, A., Abayomi-Alli, A., & Sambo-Magaji, A. (2024). Impact of artificial intelligence adoption on students’ academic performance in open and distance learning: A systematic literature review. Heliyon, 10(22), e40025. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40025] [PMID]

Akbari, M., Seydavi, M., Davis, C. H., Levin, M. E., Twohig, M. P., & Zamani, E. (2022). The current status of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in Iran: A systematic narrative review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 26, 85-96. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2022.08.007]

Bagheri Sheykhangafshe, F., Nouri, E., Savabi Niri, V., Choubtashani, M., & Farahani, H. (2024). [The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy on mental health, self-esteem and emotion regulation of medical students with imposter syndrome (Persian)]. Educational Research in Medical Sciences, 13(1), e147868. [DOI:10.5812/ermsj-147868]

Bali, B., Garba, E. J., Ahmadu, A. S., Takwate, K. T., & Malgwi, Y. M. (2024). Analysis of emerging trends in artificial intelligence for education in Nigeria. Discover Artificial Intelligence, 4(1), 110. [DOI:10.1007/s44163-024-00163-y]

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67(3), 1206-1222. [DOI:10.2307/1131888] [PMID]

Bouffard, T., Boisvert, J., Vezeau, C., & Larouche, C. (1995). The impact of goal orientation on self-regulation and performance among college students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(3), 317-329. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8279.1995.tb01152.x]

Cabras, E., Pozo, P., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., Caprara, M., & Contreras, A. (2024). Stress and academic achievement among distance university students in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: age, perceived study time, and the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(4), 4275-4295. [DOI:10.1007/s10212-024-00871-0]

Dehghani, M., Pourasad, M. H., & Khezri, H. (2025). Challenges in implementing artificial intelligence for nursing education: A systematic review. Educational Research in Medical Sciences, 14(1), e162371. [DOI:10.5812/ermsj-162371]

Ebrahimi, S., Moheb, N., & Alivani Vafa, M. (2024). Comparison of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy on cognitive distortions and rumination in adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 81. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.1.922.1]

Farnia, V., Asadi, R., Abdoli, N., Radmehr, F., Alikhani, M., Khodamoradi, M., et al. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Persian version of general self-efficacy scale (GSES) among substance abusers the year 2019-2020 in Kermanshah city. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(3), 949-953. [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.03.002]

Gao, X., & Yang, W. (2023). Multilingualism and language teacher education. System, 118, 103127. [DOI:10.1016/j.system.2023.103127]

Jafari, S. G., Sharifi, T., Chorami, M., & Ahmadi, R. (2024). The role of academic motivation in self-regulation, goal orientation, and passion among medical students with self-handicapping behaviors. Educational Research in Medical Sciences, 13(1), e151408. [DOI:10.5812/ermsj-151408]

Katajavuori, N., Vehkalahti, K., & Asikainen, H. (2023). Promoting university students’ well-being and studying with an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)-based intervention. Current Psychology, 42, 4900-4912. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-01837-x]

Knight, L., & Samuel, V. (2022). Acceptance and commitment therapy interventions in secondary schools and their impact on students’ mental health and well-being: A systematic review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 25, 90-105. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2022.06.006]

Looi, C.-K., & Jia, F. (2025). Personalization capabilities of current technology chatbots in a learning environment: An analysis of student-tutor bot interactions. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 14165–14195. [DOI:10.1007/s10639-025-13369-z]

Monica - ChatGPT. (2025). AI assistant intervention program. Retrieved from: [Link]

Moradpour, A., & Bavi, S. (2025). The effectiveness of emotional schema therapy on academic self-efficacy, test anxiety, distress tolerance, and academic resilience in students with test anxiety. Educational Research in Medical Sciences, 14(1), e160978. [DOI:10.5812/ermsj-160978]

Morosanova, V. I., Bondarenko, I. N., & Fomina, T. G. (2022). Conscious self-regulation, motivational factors, and personality traits as predictors of students’ academic performance: A linear empirical model. Psychology in Russia, 15(4), 170-187. [DOI:10.11621/pir.2022.0411] [PMID]

Nielsen, T., J. D., L. V. M., & Makransky, G. (2018). Gender fairness in self-efficacy? A rasch-based validity study of the general academic self-efficacy scale (GASE). Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 664-681. [DOI:10.1080/00313831.2017.1306796]

Nooripour, R., Hosseinian, S., Sobhaninia, M., Ghanbari, N., Hassanvandi, S., & Ilanloo, H., et al. (2022). Predicting fear of COVID-19 based on spiritual well-being and self-efficacy in Iranian university students by emphasizing the mediating role of mindfulness. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 1. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.10.1.288.6]

Rahiman, H. U., & Kodikal, R. (2024). Revolutionizing education: Artificial intelligence empowered learning in higher education. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2293431. [DOI:10.1080/2331186X.2023.2293431]

Sajjad Bakhtiary, J., Sadegh Bakhtiary, J., & Hane Mafakheri, B. (2021). The examination of the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the self-regulation questionnaire among Iranian students. Frontiers in Biomedical Technologies, 8(1), 3-8. [DOI:10.18502/fbt.v8i1.5850]

Tanveer, I., Iqbal, S., & Hussain, A. (2024). Examining the impact of ai based chatbots on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation among university students. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 5(2), 468-477. [DOI:10.47205/jdss.2024(5-II-S)45]

Ulum, Ö. G. (2024). Empowering voices: A deep dive into translanguaging perceptions among Turkish high school and university language learners. Heliyon, 10(20), e39557. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39557] [PMID]

Zarei, A., Saadipour, I., Dortaj, A., & Asadzadeh, H. (2024). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment based therapy on students’ self-efficacy beliefs and academic vitality. Journal of Psychological Science, 23(134), 37. [DOI:10.52547/JPS.23.134.287]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Family and group therapy

Received: 2025/06/29 | Accepted: 2025/09/7 | Published: 2026/12/28

Received: 2025/06/29 | Accepted: 2025/09/7 | Published: 2026/12/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |