Volume 14, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PCP 2026, 14(1): 35-46 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bana E, Taghvaei D, Jahangiri M M. Resilience’s Mediating Role Linking Coping Strategies and Meaning in Life to Elderly Death Anxiety. PCP 2026; 14 (1) :35-46

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1019-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1019-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ar.C., Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ar.C., Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran. ,d_taghvaei@iau-arak.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Ar.C., Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 711 kb]

(266 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (790 Views)

Full-Text: (163 Views)

Introduction

Aging is one of the most challenging stages of life, characterized by a complex set of physical, psychological, and social changes that older adults encounter (Bahar et al., 2021). These challenges place a heavy burden on their psychosocial functioning and mental health. Anxiety is one of the most common psychological problems during this stage, as feelings of deficiency and helplessness often accompany it. Research indicates that due to decreased self-confidence, reduced activity and mobility, the loss of friends and relatives, declining material and physical independence, and the onset of chronic illnesses, older people are at greater risk of experiencing anxiety. Among different types of anxiety, death anxiety appears to be the most prevalent (Jangi Jahantigh et al., 2022).

Death anxiety refers to feelings of dread, anxiety, or fear when thinking about death or anything related to dying. In other words, it is described as a negative emotional reaction triggered by anticipating a situation in which the individual ceases to exist, and feelings of fear and panic often accompany it. It can be defined as an abnormal and heightened fear of death that arises when an individual contemplates the process of dying or events following death (Mohammadpour, et al., 2018). This condition is experienced exclusively by living human beings and can affect existential well-being, particularly mental health functioning (Hoelterhoff, 2010). Death anxiety has the potential to intensify negative attitudes toward aging and may further increase fear and anxiety. Therefore, understanding death anxiety in the lives of the elderly is both necessary (Poordad et al., 2019). Previous studies have reported a prevalence of stress and anxiety disorders among older adults at approximately 17.1% (Kirmizioglu et al., 2009) and 25%, respectively (Yohannes et al., 2008).

The way individuals perceive stressful situations plays a crucial role in shaping the quality of their coping responses. When faced with stressors, individuals must draw upon their coping resources and select specific coping responses. Older people, who face a wide variety of stressors during aging, attempt to address their problems purposefully; however, they do not necessarily select the most effective strategies (Bitarafan et al., 2016). To manage age-related stressors, such as health challenges, illness, and the search for quality of life (QoL) and well-being, they rely on coping strategies (Peters et al., 2013). Coping strategies are cognitive-behavioral approaches employed to reduce or manage stress (Baqutayan, 2015). Previous research has shown that the use of effective coping strategies is linked with better outcomes: Problem-focused coping is associated with greater health and well-being, whereas emotion-focused coping tends to increase physical symptoms, anxiety, social dysfunction, and depression (Livarjani et al., 2016).

Given the growing elderly population worldwide (Hashemi Razini et al., 2017), the importance of studying resilience in this group and its role in successful aging has become increasingly evident. Previous studies have found that resilience is as influential as physical health in determining successful aging (McLeod et al., 2016). Findings from research in Iran also highlight resilience as a psychological variable capable of predicting life satisfaction in older adults (Livarjani et al., 2015). In other words, the greater the ability of older adults to tolerate adversity and life’s challenges, the higher their level of life satisfaction (Azami et al., 2012).

Based on these considerations, the present study seeks to answer the following question: Does resilience play a mediating role in explaining the causal relationships between coping strategies and meaning in life with death anxiety among older adults, and does the proposed model demonstrate a good fit with the collected data?

Materials and Methods

The study was applied in the purpose and employed a descriptive-correlational design. The research framework was based on a causal model using structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population consisted of all older men and women residing in Tehran City, Iran, in 2024.

Given the large size of the population, a multistage cluster sampling method was used. The procedure was conducted through convenience sampling. For this purpose, one park from each of the northern, eastern, northeastern, and southeastern regions of Tehran was selected, based on municipal data identifying public spaces where older adults commonly gather.

Study instruments

Templer death anxiety scale

The Templer death anxiety scale (1970) consists of 15 items that measure participants’ attitudes toward death. Responses are given in a dichotomous format (Yes/No) (Templer, 1970). Scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of death anxiety. Studies have confirmed the validity and reliability of this instrument. In the original version, the test re-test reliability coefficient was reported as 0.83, and concurrent validity coefficients were reported as 0.27 with the manifest anxiety scale and 0.40 with the depression scale. In Iran, Rajabii and Bahrani (2001) reported an internal consistency coefficient of 0.73 and a correlation of 0.34 with the Manifest Anxiety Scale, supporting its convergent validity.

Endler and Parker’s coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS)

The CISS, developed by Endler and Parker (1990) and later translated into Persian, consists of 48 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). It assesses three primary coping dimensions: (1) problem-focused coping (16 items), (2) emotion-focused coping (16 items), and (3) avoidance-oriented coping (16 items), the latter including two subcomponents—distraction and social diversion. Each item is scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater use of that coping strategy. Endler and Parker (1990) reported Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 0.92 for problem-focused coping, 0.82 to 0.85 for emotion-focused coping, and 0.82 to 0.85 for avoidance-oriented coping. Subsequent studies in Iran confirmed its high reliability (α=0.81) and demonstrated acceptable convergent and construct validity (Ghoreyshi Rad, 2010).

Meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

The meaning in life questionnaire, developed by Steger et al. (2006), consists of 10 items divided into two subscales: (1) presence of meaning (e.g. “I understand my life’s meaning,” “I have a satisfying purpose in life”), and (2) search for meaning (e.g. “I am always searching for something that makes my life feel meaningful,” “I am seeking a purpose or mission for my life”). Each subscale contains five items, and responses are rated on a Likert scale. Scores are calculated separately for the two dimensions, with higher scores indicating a stronger presence of or search for meaning. Research has reported reliability coefficients of 0.82 for the overall scale, 0.87 for the search subscale, and 0.7 for the presence subscale. Test re-test reliability in Iran yielded coefficients of 0.84 for the presence of meaning and 0.74 for the search for meaning, confirming its stability and validity (Masraabadi et al., 2013).

Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

The CD-RISC (2003) is a 25-item instrument designed to assess an individual’s ability to cope with stress and adversity. It includes 5 subscales: Personal competence (8 items), tolerance of negative affect and stress resistance (7 items), positive acceptance of change (5 items), self-control (3 items), and spiritual influences (2 items). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. Total scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Original studies reported strong psychometric properties, including a test re-test reliability coefficient of 0.87 and good construct validity. Research conducted in Iran further supported its reliability (Cronbach α=0.93) and validity through factor analysis, with additional studies reporting coefficients between 0.82 and 0.89 across different populations (Ahangarzadeh et al., 2015).

Results

In this study, 384 older adults (183 women and 201 men) participated. Regarding age distribution, 138 participants (36.9%) were younger than 70 years, 154 participants (40.1%) were between 71 and 75 years, and 92 participants (24%) were older than 75 years. In terms of educational level, 114 participants (29.7%) had basic literacy, 108 participants (28.1%) had a middle school diploma, 95 participants (24.7%) held a high school diploma, and 67 participants (17.5%) had education above a diploma. With respect to marital status, 285 participants (67.2%) were married, 39 participants (10.1%) were divorced, and 87 participants (22.7%) were widowed.

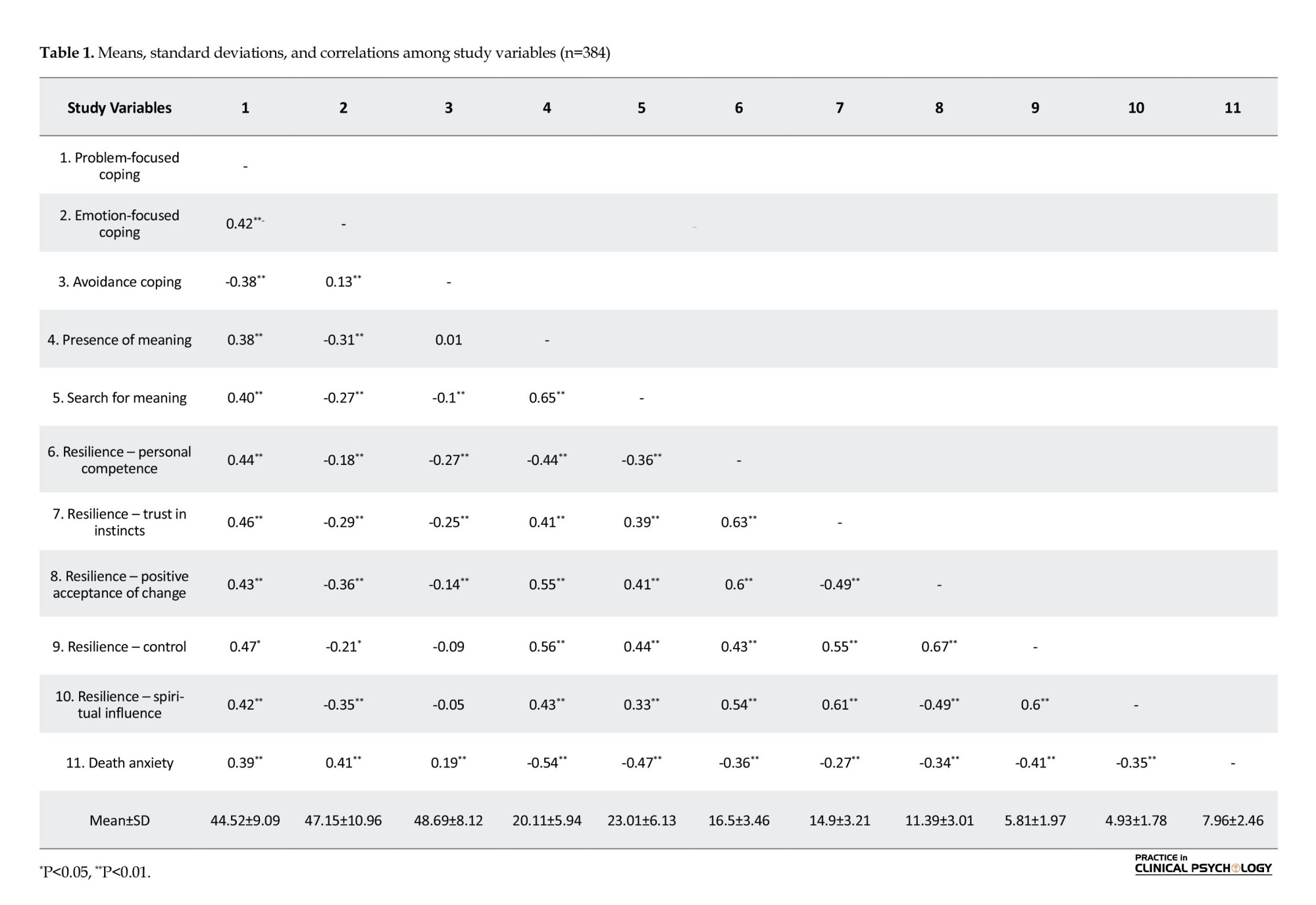

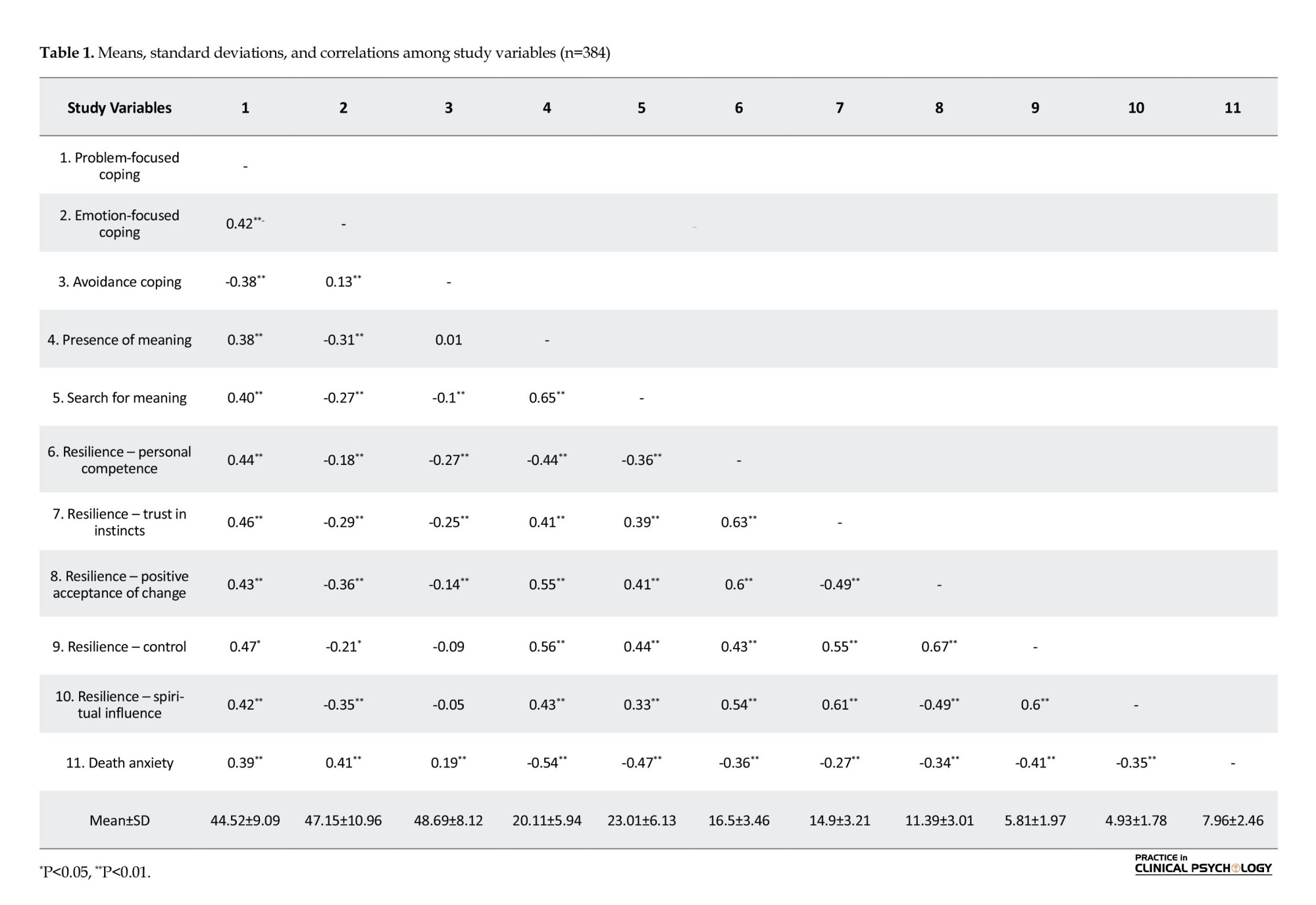

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD, and correlation coefficients of the study variables (death anxiety, coping strategies, resilience, and meaning in life). The correlation results indicated a significant negative association between death anxiety and resilience, coping strategies, and meaning in life. Furthermore, the SEM showed a good fit to the data, and both direct and indirect paths were supported in line with the study hypotheses.

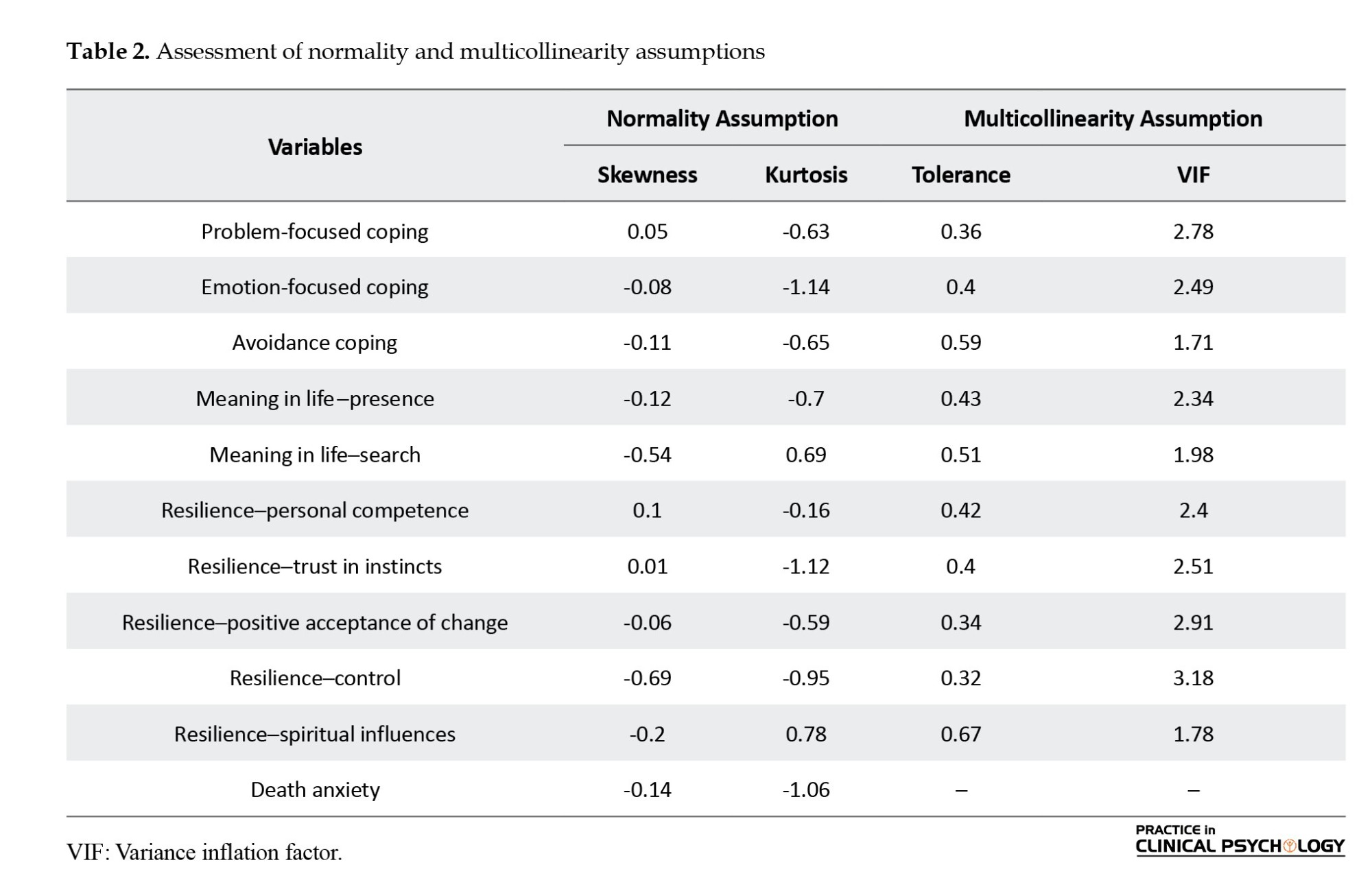

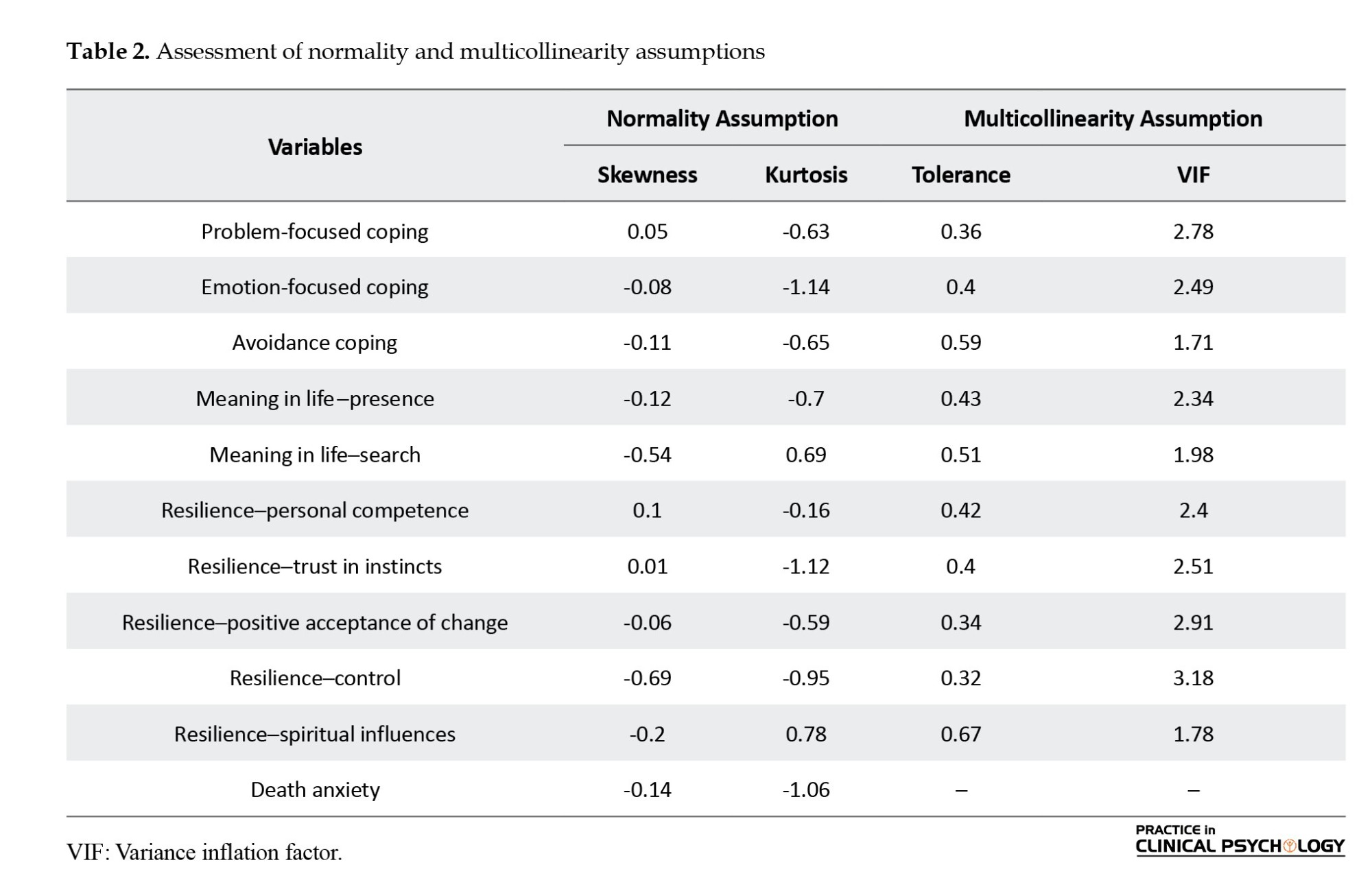

Based on the results presented in Table 1, the correlation coefficients among the variables were in the expected direction and consistent with the theoretical framework of the study. To assess the assumption of univariate normality, the skewness and kurtosis values of each variable were examined. Furthermore, to evaluate the assumption of multicollinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficients were assessed, the results of which are presented in Table 2.

According to the findings of Table 2, the skewness and kurtosis values of all variables were within the ±2 range. This finding indicates that the assumption of univariate normality was met. Table 2 further shows that the assumption of non-collinearity was also established in the present study, as the tolerance values of the predictor variables were greater than 0.10 and their VIF values were less than 10. According to the view of Myers et al. (2012), a tolerance value less than 0.10 and a VIF greater than 10 indicate a violation of the non-collinearity assumption.

In this study, to assess the assumption of multivariate normality, the Mahalanobis distance values were examined. The skewness and kurtosis values for Mahalanobis distance were 1.09 and 0.46, respectively, showing that the data followed a multivariate normal distribution. Finally, to evaluate the assumption of homogeneity of variances, the scatterplot of standardized error variances was analyzed, and the results confirmed that the assumption was satisfied.

Model analysis

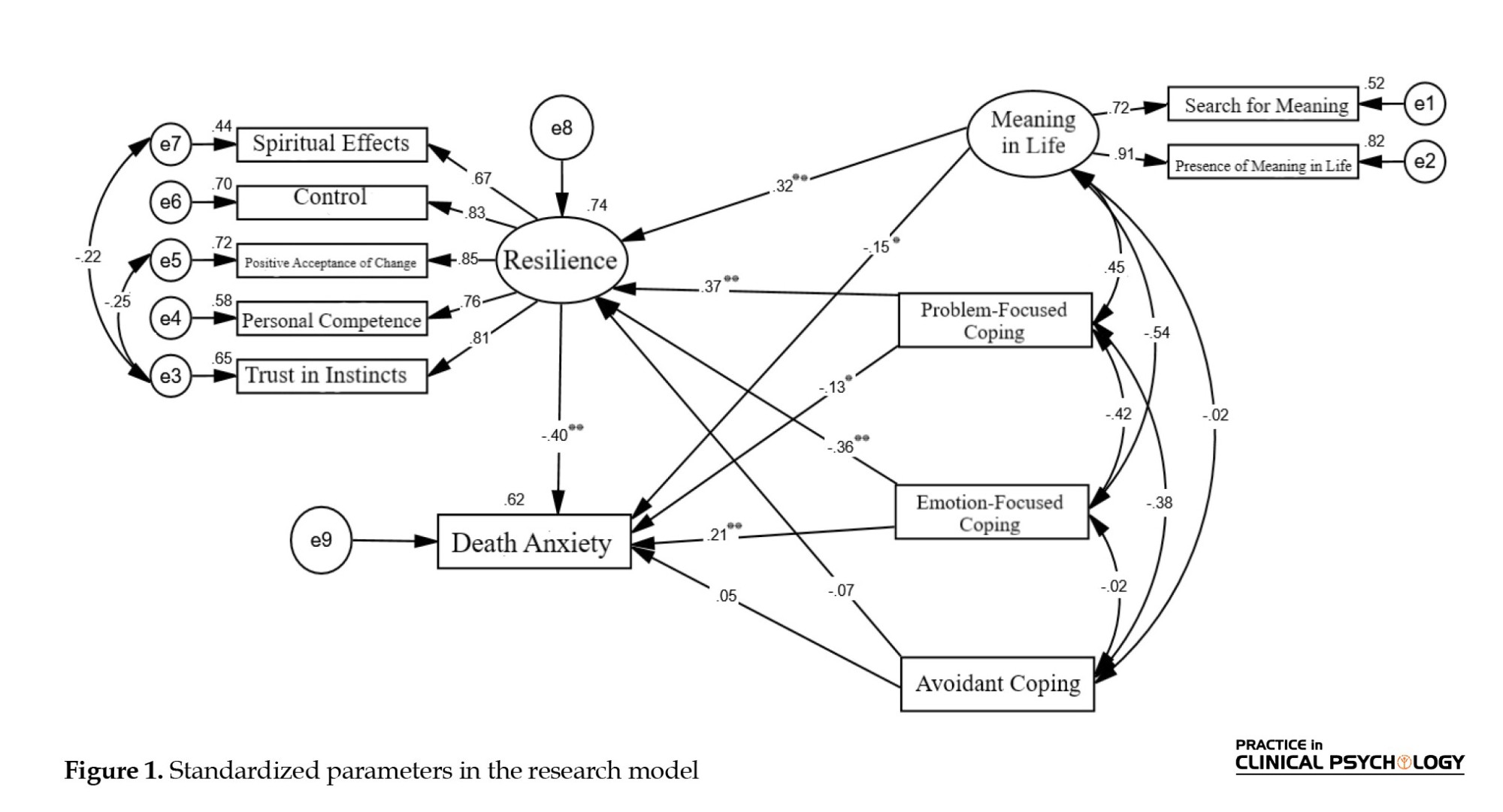

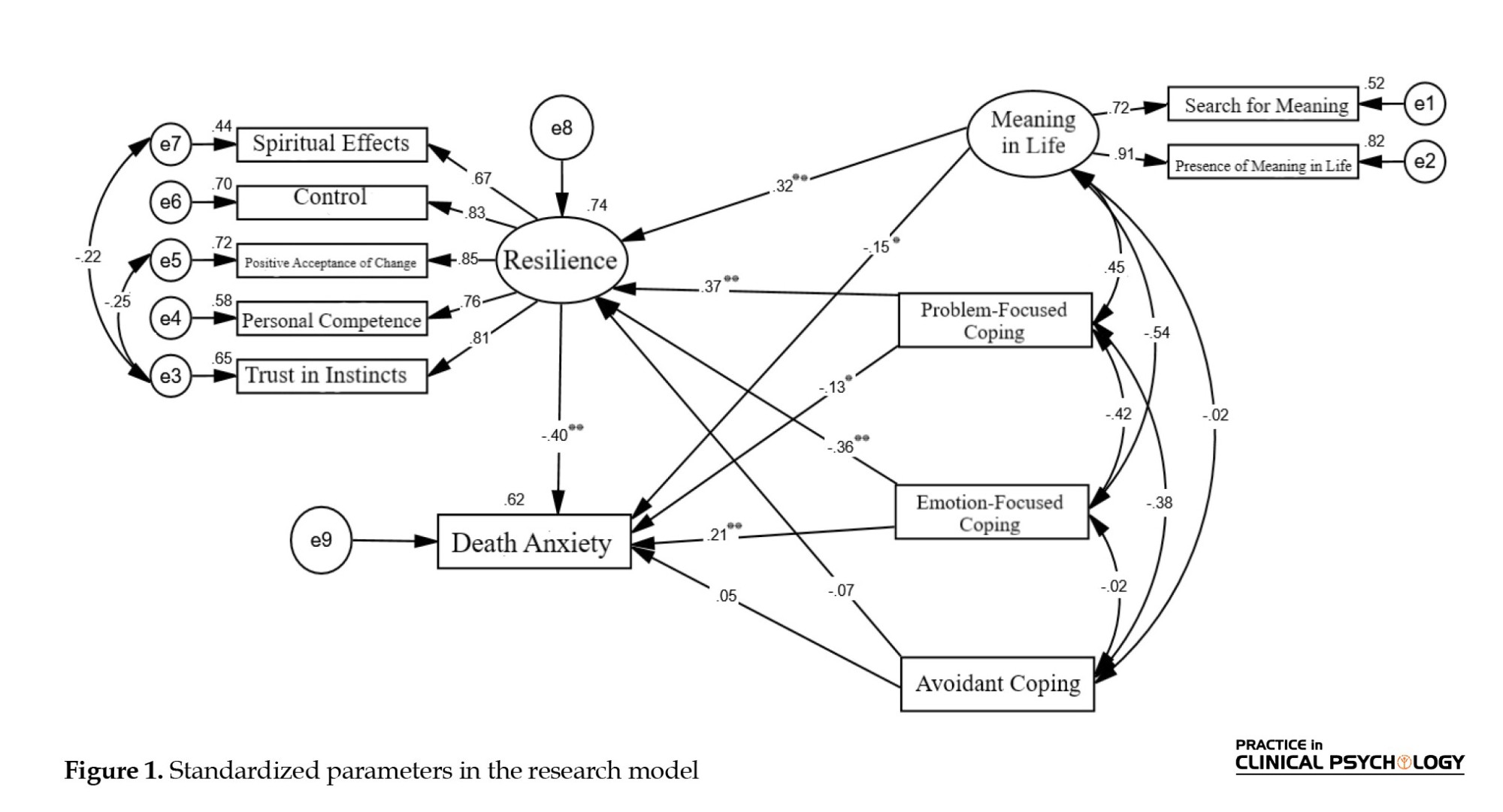

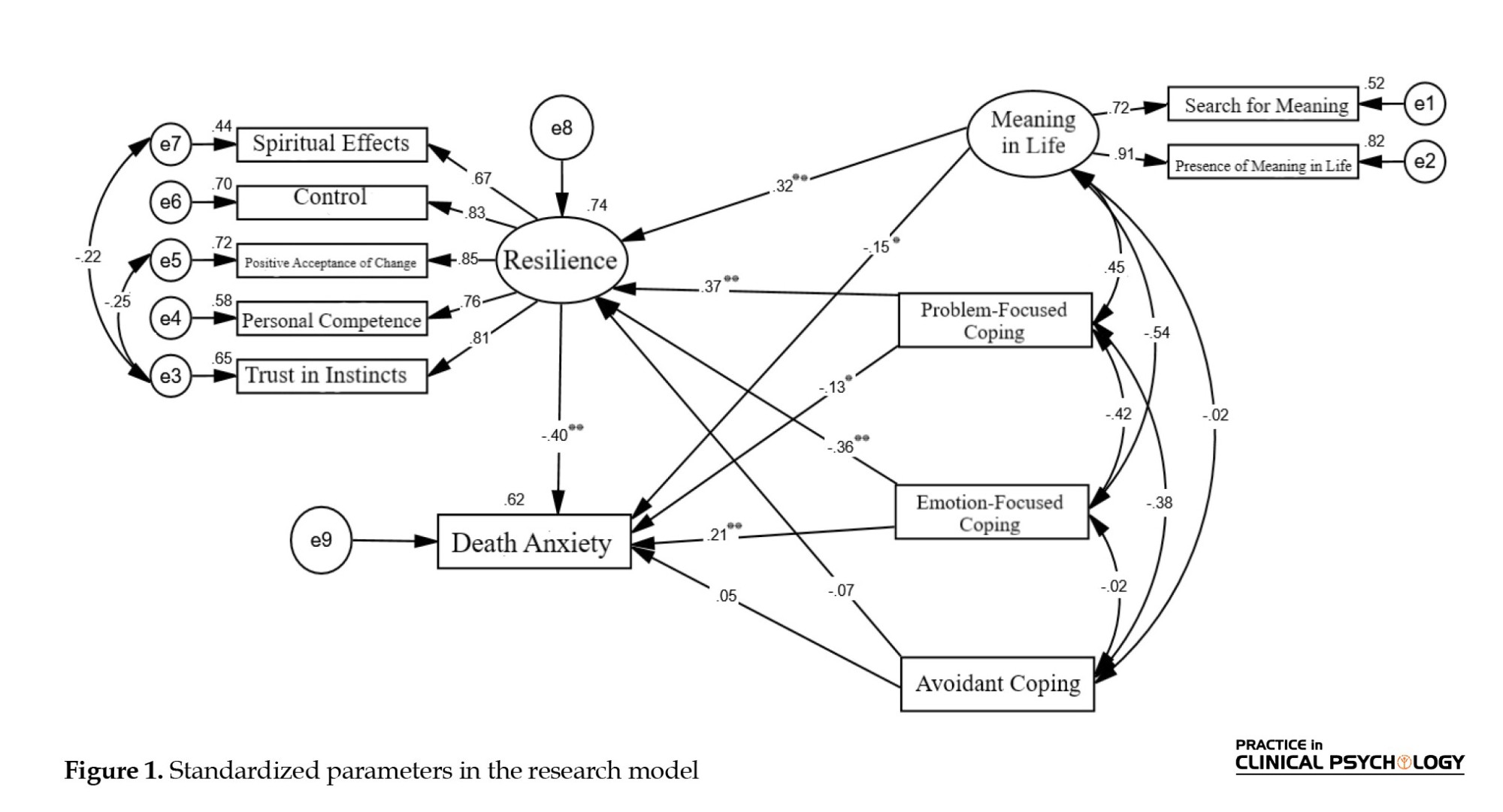

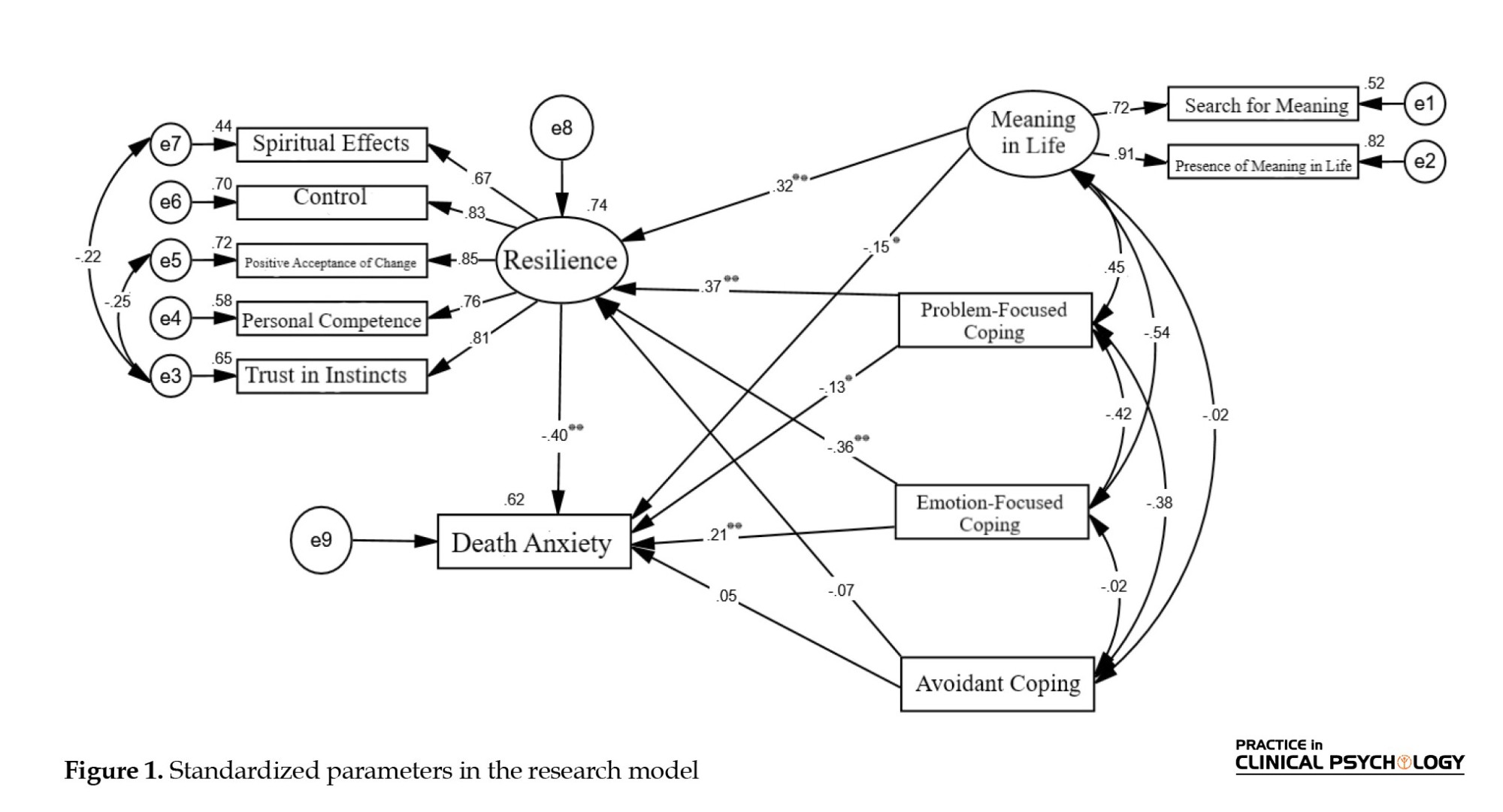

As shown in Figure 1, the research model hypothesized that coping styles and meaning in life are related to death anxiety in the elderly, both directly and indirectly through the mediation of resilience.

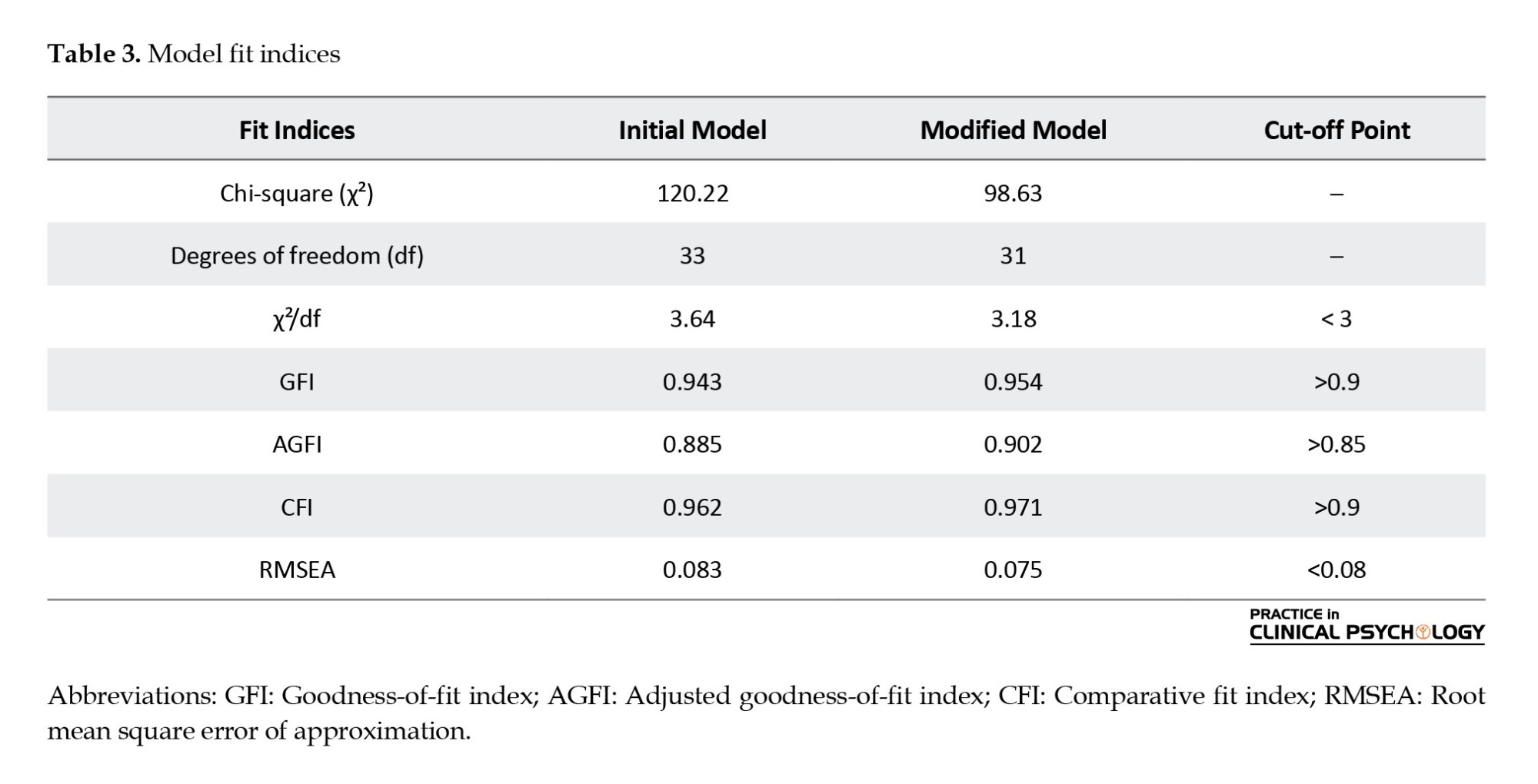

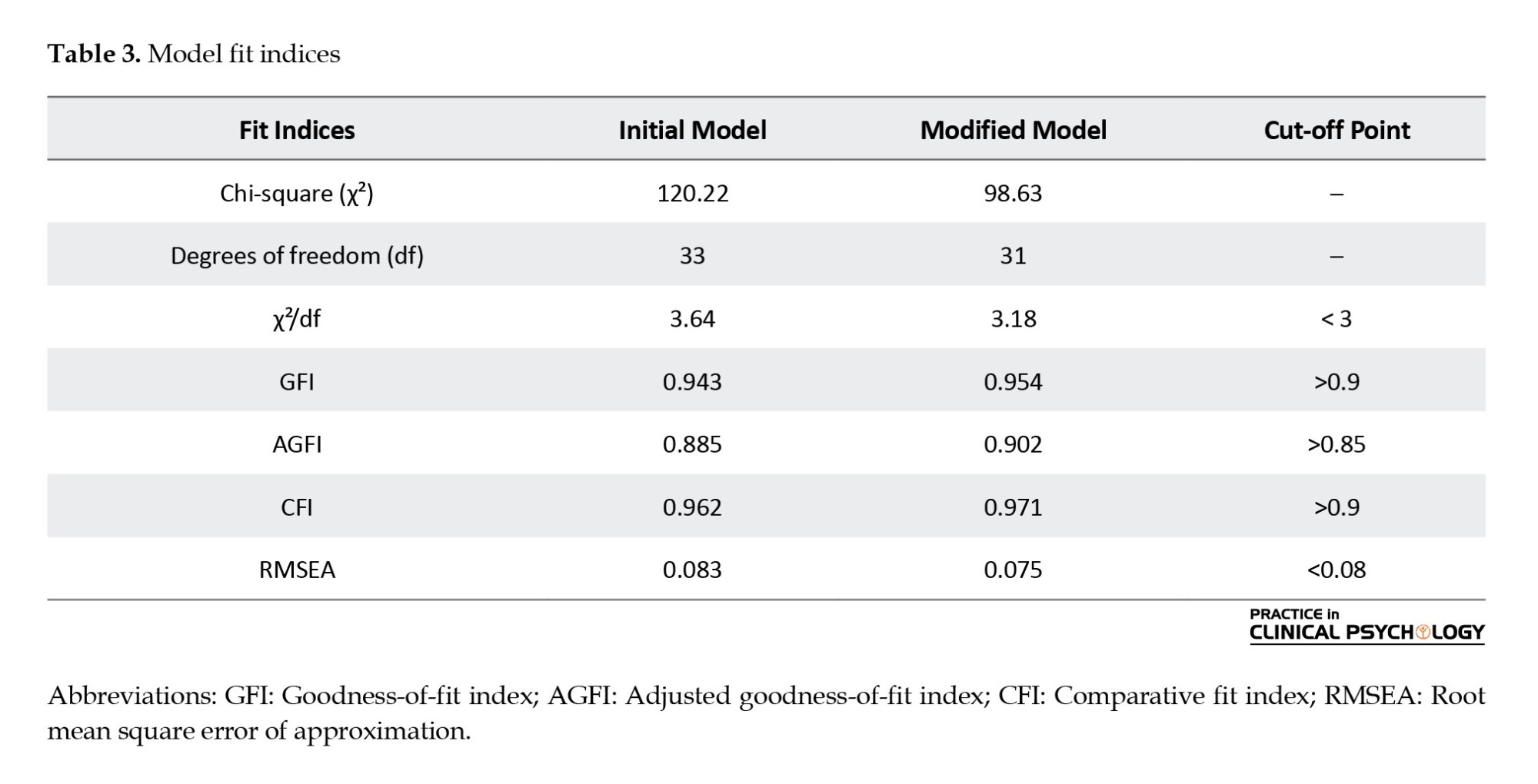

Meaning in life and resilience were considered latent variables and were assumed to be measured by their respective indicators. Model fit was evaluated using SEM with AMOS software, version 24.0 software and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Table 3 presents the fit indices of the research model.

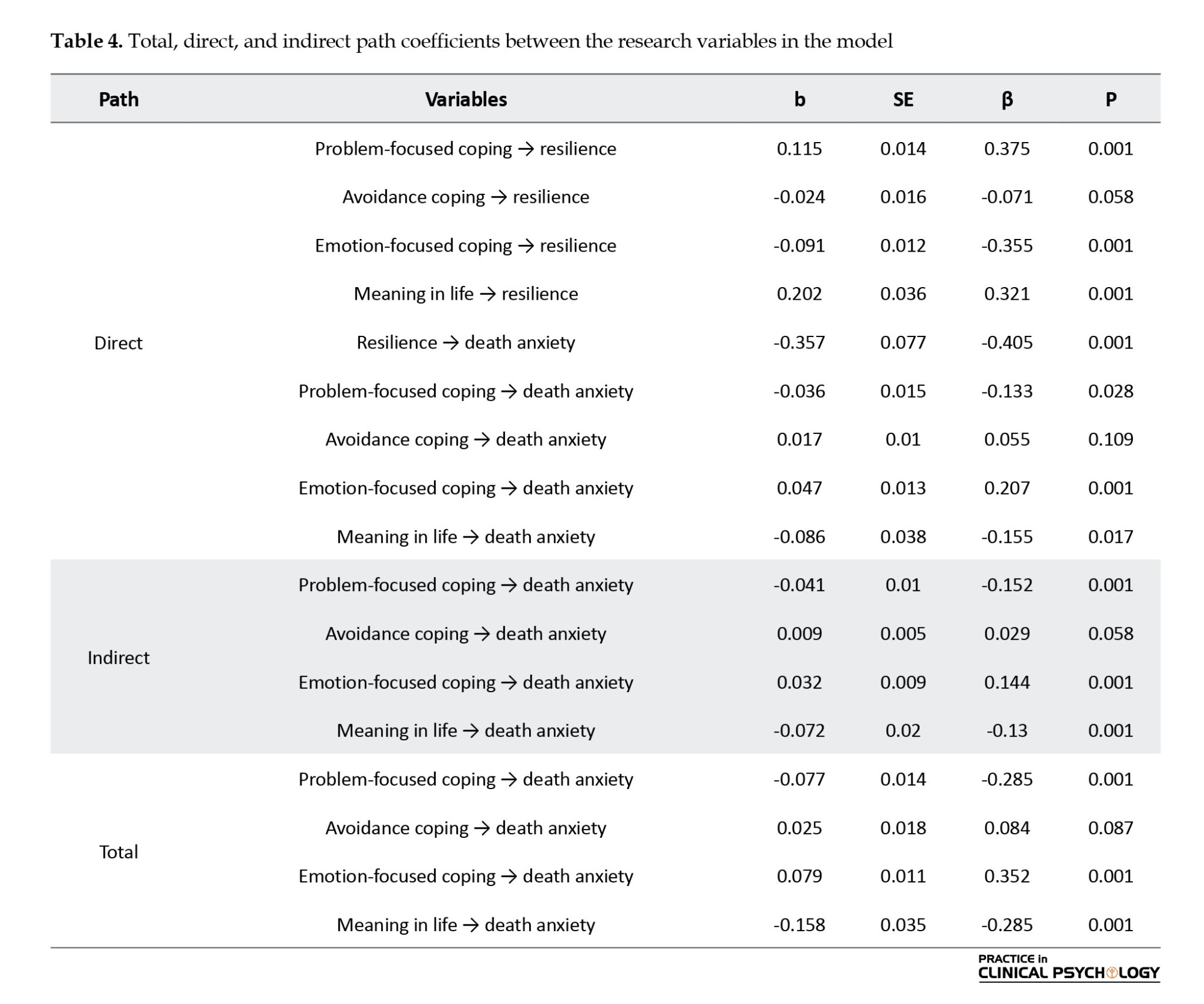

Table 3 shows that, except for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) fit index, the other fit indices obtained from the analysis support an acceptable model fit with the collected data. Given the importance of the RMSEA index in assessing model fit, modification indices were evaluated, and based on them, covariances were created between the error terms of the indicators of personal competence and positive acceptance of change on the one hand, and personal competence and spiritual influences on the other. Following these modifications, the RMSEA index also supported an acceptable model fit with the data. Subsequently, Table 4 presents the path coefficients in the model.

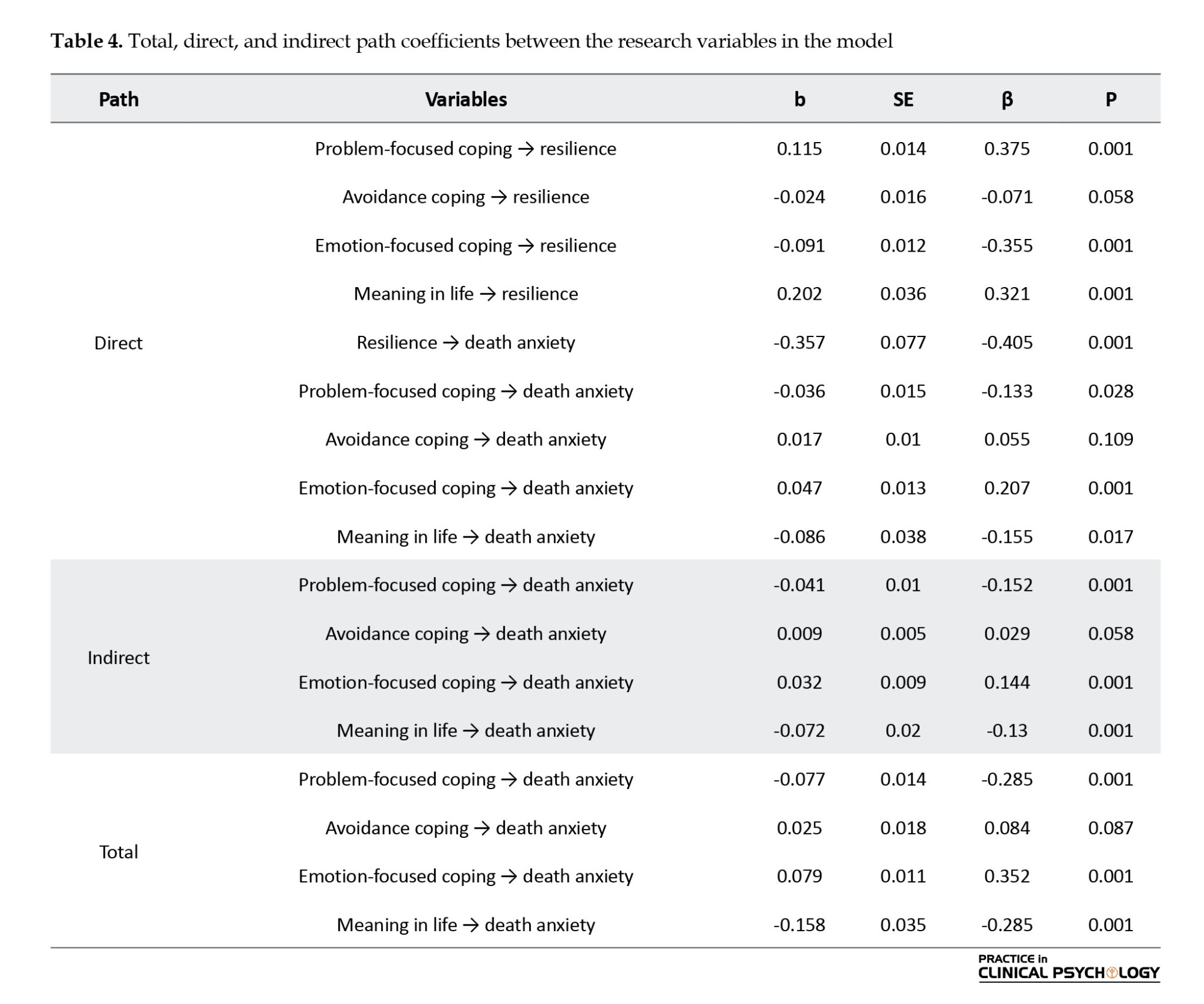

Table 4 shows that the total path coefficient between problem-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=-0.285, P=0.001) was negative. In contrast, the total path coefficient between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=0.352, P=0.001) was positive and significant. The total path coefficient between meaning in life and death anxiety (β=-0.285, P=0.001), as well as the path coefficient between resilience and death anxiety (β=-0.405, P=0.001), were both negative and significant. According to the results of Table 4, the indirect path coefficient between problem-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=-0.152, P=0.001) was negative. In contrast, the indirect path coefficient between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=0.144, P=0.001) was positive and significant. Furthermore, the indirect path coefficient between meaning in life and death anxiety (β=-0.130, P=0.001) was also negative and significant.

Accordingly, it was concluded that resilience mediates the relationship between problem-focused coping style and meaning in life with death anxiety among older adults in a negative direction. In contrast, it mediates the relationship between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety in a positive and significant manner.

Based on Figure 1, the coefficient of multiple determination (R²) for death anxiety was 0.62, indicating that coping styles, meaning in life, and resilience together explain 62% of the variance in death anxiety among older adults.

Discussion

Hypothesis 1

Hypothesis 1 states that coping strategies are related to death anxiety in older adults. The findings of the present study indicated a significant negative relationship between coping strategies and death anxiety in older adults. In other words, older adults who employ adaptive coping strategies, such as problem-solving, acceptance, cognitive restructuring, and seeking social support, experience lower levels of death anxiety compared to those who rely on avoidance or maladaptive coping strategies, such as denial, withdrawal, or passivity. These results align well with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theoretical framework, which emphasizes that coping styles can determine an individual’s response to psychological and existential stressors.

Coping strategies serve not only as methods for handling daily stress but also play a key role in confronting more fundamental challenges, such as death. Since death is an inevitable aspect of life, the ability to cope with death-related anxiety is particularly important. Older adults who actively and realistically confront thoughts of death and employ strategies such as problem-solving, meaning-seeking, acceptance, and cognitive reframing can perceive the threat of death as a natural part of life, without experiencing chronic anxiety or feelings of helplessness.

In a study by Ahmadi et al. (2017) on 180 older adults in Isfahan, problem-focused coping strategies were found to be inversely related to death anxiety. In contrast, emotion-focused strategies (such as denial or passivity) were positively associated with death anxiety. This finding is consistent with the study by Johnson et al. (2023), which demonstrated that active coping styles, by enhancing a sense of control and predictability, reduce existential anxiety.

Moreover, cognitive-behavioral theories emphasize that how individuals perceive and evaluate death plays a crucial role in the intensity of their anxiety. Older adults who view death as an ultimate threat and the absolute end of everything experience higher anxiety. In contrast, those who use strategies such as cognitive reframing to perceive death as a natural stage of life and a part of human meaning and development experience lower levels of death anxiety.

On the other hand, avoidance strategies, such as evading thoughts of death, excessive distraction, or denial, may temporarily reduce anxiety but exacerbate it in the long term. These coping styles disrupt the psychological adaptation process and prevent conscious engagement with the reality of death.

From a clinical perspective, enhancing effective coping strategies in older adults is considered a necessary intervention. Training these strategies through group counseling, psychological programs in elderly care centers, and educational media can reduce death anxiety while increasing life satisfaction, hopefulness, and psychological well-being. Strengthening these strategies, particularly for individuals who previously relied on maladaptive coping, can significantly improve their QoL.

Ultimately, the results of this hypothesis underscore the importance of focusing on coping styles in older adults. Since coping strategies can be learned and improved through practice and therapeutic interventions, enhancing these strategies can be expected to reduce death anxiety in the elderly population meaningfully—a need that becomes increasingly critical with the growing number of older adults in society.

Hypothesis 2

Hypothesis 2 states that resilience mediates the relationship between coping strategies and death anxiety in older adults. The path analysis results in this study indicated that resilience plays a significant mediating role between coping strategies and death anxiety. In other words, coping strategies have a direct effect on death anxiety, but much of this effect is explained through their influence on the level of resilience. This mediating model is particularly important in older adults, as effective coping during this stage of life, in interaction with resilience, plays a crucial role in emotion regulation and the reduction of existential anxiety.

Theoretically, Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model defines coping strategies as cognitive and behavioral responses to stressful situations. Strategies such as problem-solving, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring can enhance perceived control and meaning in life, thereby strengthening resilience and reducing death anxiety. Conversely, avoidance strategies, such as denial or evasion, weaken resilience and exacerbate feelings of helplessness, increasing death anxiety.

Goldstein et al. (2013) demonstrated that resilient individuals are not only more successful in selecting effective coping strategies but also experience fewer negative effects from stressful conditions. Older adults who employ active coping strategies generally have a more realistic perception of death, viewing it as a natural part of life rather than a threatening event.

A domestic study by Jeste et al. (2014) also showed that the relationship between coping styles and mental health is stable and positive only when individuals possess a high level of resilience. Essentially, resilience functions as a “psychological moderator” that enhances or diminishes the effectiveness of coping strategies. Without sufficient resilience, even adaptive strategies may become ineffective.

Additionally, in older adulthood, which is often accompanied by increased physical and social limitations, resilience can mediate the positive effects of active coping and mitigate the negative effects of avoidance coping. For example, an older adult using an “acceptance” strategy who also has a high level of resilience is better able to cope with the concept of death and experiences lower anxiety.

From a practical standpoint, these findings emphasize the need for integrated interventions. Without enhancing resilience, programs that focus solely on teaching coping strategies are unlikely to produce lasting reductions in death anxiety. In contrast, psychological interventions that simultaneously target effective coping and resilience enhancement (e.g. acceptance and commitment therapy or meaning-centered therapy) can have a deeper impact on older adults’ mental health.

In summary, these findings support a complex yet effective causal model in gerontological psychology: older adults’ coping strategies can effectively reduce death anxiety, provided they are accompanied by sufficient resilience. This model should be considered in the design of mental health programs for older adults.

Hypothesis 3

Hypothesis 3 states that resilience mediates the relationship between meaning in life and death anxiety in older adults. The path analysis results of the present study showed that resilience plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between meaning in life and death anxiety. In other words, older adults who perceive meaning, purpose, and value in their lives experience lower death anxiety through enhanced resilience. This finding is not only statistically significant but also strongly supported by theoretical and empirical evidence.

From the perspective of Frankl’s (1963) logotherapy, humans can interpret negative experiences positively, even under the most challenging life conditions, by finding meaning. This meaningful interpretation of life is a key factor in enhancing resilience. Older adults who experience purpose and value in life possess greater psychological flexibility, enabling them to accept challenges such as aging, illness, and death as natural parts of life.

Wong (2008), in his positive psychology of death theory, posits that “healthy mortality” is made possible through a meaningful life. He argues that resilient individuals draw on life’s meaningful resources, allowing them to respond to death with acceptance, calmness, and even a sense of liberation, rather than anxiety.

Practically, research shows that interventions aimed at helping older adults discover or reconstruct meaning in life can effectively enhance resilience. Ahmadi et al. (2017), using group meaning-centered therapy with older adults, found that this intervention not only reduced death anxiety but also significantly increased psychological resilience.

In conclusion, integrating meaning in life with strategies to strengthen resilience provides a comprehensive framework for effective psychological interventions in older adults. Activities such as life review, participation in volunteer or spiritual activities, and role redefinition can help older adults cultivate both meaning and resilience simultaneously, thereby alleviating death anxiety.

Conclusion

The present study highlights the critical roles of coping strategies, meaning in life, and resilience in shaping death anxiety among older adults. Problem-focused coping and a strong sense of life meaning are associated with lower death anxiety, while emotion-focused coping can increase it, particularly when resilience is low. Resilience functions as a key mediator, explaining how coping strategies and meaning in life influence the experience of death anxiety. Overall, coping strategies, meaning in life, and resilience together account for 62% of the variance in death anxiety among the elderly, emphasizing their practical importance in psychological interventions.

These findings underscore the need for interventions targeting both enhancement of adaptive coping strategies and resilience-building programs, along with activities that promote meaningful engagement in life. Such combined approaches can significantly reduce death anxiety and improve psychological well-being, offering actionable insights for clinicians, caregivers, and policymakers working with aging populations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethcis Committee of Arak Branch, Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.ARAK.REC.1403.114).

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD Dissertation of Esmaeil Bana, approved by the Faculty of Islamic Education, Arak Branch, Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Aging is one of the most challenging stages of life, characterized by a complex set of physical, psychological, and social changes that older adults encounter (Bahar et al., 2021). These challenges place a heavy burden on their psychosocial functioning and mental health. Anxiety is one of the most common psychological problems during this stage, as feelings of deficiency and helplessness often accompany it. Research indicates that due to decreased self-confidence, reduced activity and mobility, the loss of friends and relatives, declining material and physical independence, and the onset of chronic illnesses, older people are at greater risk of experiencing anxiety. Among different types of anxiety, death anxiety appears to be the most prevalent (Jangi Jahantigh et al., 2022).

Death anxiety refers to feelings of dread, anxiety, or fear when thinking about death or anything related to dying. In other words, it is described as a negative emotional reaction triggered by anticipating a situation in which the individual ceases to exist, and feelings of fear and panic often accompany it. It can be defined as an abnormal and heightened fear of death that arises when an individual contemplates the process of dying or events following death (Mohammadpour, et al., 2018). This condition is experienced exclusively by living human beings and can affect existential well-being, particularly mental health functioning (Hoelterhoff, 2010). Death anxiety has the potential to intensify negative attitudes toward aging and may further increase fear and anxiety. Therefore, understanding death anxiety in the lives of the elderly is both necessary (Poordad et al., 2019). Previous studies have reported a prevalence of stress and anxiety disorders among older adults at approximately 17.1% (Kirmizioglu et al., 2009) and 25%, respectively (Yohannes et al., 2008).

The way individuals perceive stressful situations plays a crucial role in shaping the quality of their coping responses. When faced with stressors, individuals must draw upon their coping resources and select specific coping responses. Older people, who face a wide variety of stressors during aging, attempt to address their problems purposefully; however, they do not necessarily select the most effective strategies (Bitarafan et al., 2016). To manage age-related stressors, such as health challenges, illness, and the search for quality of life (QoL) and well-being, they rely on coping strategies (Peters et al., 2013). Coping strategies are cognitive-behavioral approaches employed to reduce or manage stress (Baqutayan, 2015). Previous research has shown that the use of effective coping strategies is linked with better outcomes: Problem-focused coping is associated with greater health and well-being, whereas emotion-focused coping tends to increase physical symptoms, anxiety, social dysfunction, and depression (Livarjani et al., 2016).

Given the growing elderly population worldwide (Hashemi Razini et al., 2017), the importance of studying resilience in this group and its role in successful aging has become increasingly evident. Previous studies have found that resilience is as influential as physical health in determining successful aging (McLeod et al., 2016). Findings from research in Iran also highlight resilience as a psychological variable capable of predicting life satisfaction in older adults (Livarjani et al., 2015). In other words, the greater the ability of older adults to tolerate adversity and life’s challenges, the higher their level of life satisfaction (Azami et al., 2012).

Based on these considerations, the present study seeks to answer the following question: Does resilience play a mediating role in explaining the causal relationships between coping strategies and meaning in life with death anxiety among older adults, and does the proposed model demonstrate a good fit with the collected data?

Materials and Methods

The study was applied in the purpose and employed a descriptive-correlational design. The research framework was based on a causal model using structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population consisted of all older men and women residing in Tehran City, Iran, in 2024.

Given the large size of the population, a multistage cluster sampling method was used. The procedure was conducted through convenience sampling. For this purpose, one park from each of the northern, eastern, northeastern, and southeastern regions of Tehran was selected, based on municipal data identifying public spaces where older adults commonly gather.

Study instruments

Templer death anxiety scale

The Templer death anxiety scale (1970) consists of 15 items that measure participants’ attitudes toward death. Responses are given in a dichotomous format (Yes/No) (Templer, 1970). Scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of death anxiety. Studies have confirmed the validity and reliability of this instrument. In the original version, the test re-test reliability coefficient was reported as 0.83, and concurrent validity coefficients were reported as 0.27 with the manifest anxiety scale and 0.40 with the depression scale. In Iran, Rajabii and Bahrani (2001) reported an internal consistency coefficient of 0.73 and a correlation of 0.34 with the Manifest Anxiety Scale, supporting its convergent validity.

Endler and Parker’s coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS)

The CISS, developed by Endler and Parker (1990) and later translated into Persian, consists of 48 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). It assesses three primary coping dimensions: (1) problem-focused coping (16 items), (2) emotion-focused coping (16 items), and (3) avoidance-oriented coping (16 items), the latter including two subcomponents—distraction and social diversion. Each item is scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater use of that coping strategy. Endler and Parker (1990) reported Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 0.92 for problem-focused coping, 0.82 to 0.85 for emotion-focused coping, and 0.82 to 0.85 for avoidance-oriented coping. Subsequent studies in Iran confirmed its high reliability (α=0.81) and demonstrated acceptable convergent and construct validity (Ghoreyshi Rad, 2010).

Meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

The meaning in life questionnaire, developed by Steger et al. (2006), consists of 10 items divided into two subscales: (1) presence of meaning (e.g. “I understand my life’s meaning,” “I have a satisfying purpose in life”), and (2) search for meaning (e.g. “I am always searching for something that makes my life feel meaningful,” “I am seeking a purpose or mission for my life”). Each subscale contains five items, and responses are rated on a Likert scale. Scores are calculated separately for the two dimensions, with higher scores indicating a stronger presence of or search for meaning. Research has reported reliability coefficients of 0.82 for the overall scale, 0.87 for the search subscale, and 0.7 for the presence subscale. Test re-test reliability in Iran yielded coefficients of 0.84 for the presence of meaning and 0.74 for the search for meaning, confirming its stability and validity (Masraabadi et al., 2013).

Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

The CD-RISC (2003) is a 25-item instrument designed to assess an individual’s ability to cope with stress and adversity. It includes 5 subscales: Personal competence (8 items), tolerance of negative affect and stress resistance (7 items), positive acceptance of change (5 items), self-control (3 items), and spiritual influences (2 items). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. Total scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Original studies reported strong psychometric properties, including a test re-test reliability coefficient of 0.87 and good construct validity. Research conducted in Iran further supported its reliability (Cronbach α=0.93) and validity through factor analysis, with additional studies reporting coefficients between 0.82 and 0.89 across different populations (Ahangarzadeh et al., 2015).

Results

In this study, 384 older adults (183 women and 201 men) participated. Regarding age distribution, 138 participants (36.9%) were younger than 70 years, 154 participants (40.1%) were between 71 and 75 years, and 92 participants (24%) were older than 75 years. In terms of educational level, 114 participants (29.7%) had basic literacy, 108 participants (28.1%) had a middle school diploma, 95 participants (24.7%) held a high school diploma, and 67 participants (17.5%) had education above a diploma. With respect to marital status, 285 participants (67.2%) were married, 39 participants (10.1%) were divorced, and 87 participants (22.7%) were widowed.

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD, and correlation coefficients of the study variables (death anxiety, coping strategies, resilience, and meaning in life). The correlation results indicated a significant negative association between death anxiety and resilience, coping strategies, and meaning in life. Furthermore, the SEM showed a good fit to the data, and both direct and indirect paths were supported in line with the study hypotheses.

Based on the results presented in Table 1, the correlation coefficients among the variables were in the expected direction and consistent with the theoretical framework of the study. To assess the assumption of univariate normality, the skewness and kurtosis values of each variable were examined. Furthermore, to evaluate the assumption of multicollinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficients were assessed, the results of which are presented in Table 2.

According to the findings of Table 2, the skewness and kurtosis values of all variables were within the ±2 range. This finding indicates that the assumption of univariate normality was met. Table 2 further shows that the assumption of non-collinearity was also established in the present study, as the tolerance values of the predictor variables were greater than 0.10 and their VIF values were less than 10. According to the view of Myers et al. (2012), a tolerance value less than 0.10 and a VIF greater than 10 indicate a violation of the non-collinearity assumption.

In this study, to assess the assumption of multivariate normality, the Mahalanobis distance values were examined. The skewness and kurtosis values for Mahalanobis distance were 1.09 and 0.46, respectively, showing that the data followed a multivariate normal distribution. Finally, to evaluate the assumption of homogeneity of variances, the scatterplot of standardized error variances was analyzed, and the results confirmed that the assumption was satisfied.

Model analysis

As shown in Figure 1, the research model hypothesized that coping styles and meaning in life are related to death anxiety in the elderly, both directly and indirectly through the mediation of resilience.

Meaning in life and resilience were considered latent variables and were assumed to be measured by their respective indicators. Model fit was evaluated using SEM with AMOS software, version 24.0 software and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Table 3 presents the fit indices of the research model.

Table 3 shows that, except for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) fit index, the other fit indices obtained from the analysis support an acceptable model fit with the collected data. Given the importance of the RMSEA index in assessing model fit, modification indices were evaluated, and based on them, covariances were created between the error terms of the indicators of personal competence and positive acceptance of change on the one hand, and personal competence and spiritual influences on the other. Following these modifications, the RMSEA index also supported an acceptable model fit with the data. Subsequently, Table 4 presents the path coefficients in the model.

Table 4 shows that the total path coefficient between problem-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=-0.285, P=0.001) was negative. In contrast, the total path coefficient between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=0.352, P=0.001) was positive and significant. The total path coefficient between meaning in life and death anxiety (β=-0.285, P=0.001), as well as the path coefficient between resilience and death anxiety (β=-0.405, P=0.001), were both negative and significant. According to the results of Table 4, the indirect path coefficient between problem-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=-0.152, P=0.001) was negative. In contrast, the indirect path coefficient between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety (β=0.144, P=0.001) was positive and significant. Furthermore, the indirect path coefficient between meaning in life and death anxiety (β=-0.130, P=0.001) was also negative and significant.

Accordingly, it was concluded that resilience mediates the relationship between problem-focused coping style and meaning in life with death anxiety among older adults in a negative direction. In contrast, it mediates the relationship between emotion-focused coping style and death anxiety in a positive and significant manner.

Based on Figure 1, the coefficient of multiple determination (R²) for death anxiety was 0.62, indicating that coping styles, meaning in life, and resilience together explain 62% of the variance in death anxiety among older adults.

Discussion

Hypothesis 1

Hypothesis 1 states that coping strategies are related to death anxiety in older adults. The findings of the present study indicated a significant negative relationship between coping strategies and death anxiety in older adults. In other words, older adults who employ adaptive coping strategies, such as problem-solving, acceptance, cognitive restructuring, and seeking social support, experience lower levels of death anxiety compared to those who rely on avoidance or maladaptive coping strategies, such as denial, withdrawal, or passivity. These results align well with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theoretical framework, which emphasizes that coping styles can determine an individual’s response to psychological and existential stressors.

Coping strategies serve not only as methods for handling daily stress but also play a key role in confronting more fundamental challenges, such as death. Since death is an inevitable aspect of life, the ability to cope with death-related anxiety is particularly important. Older adults who actively and realistically confront thoughts of death and employ strategies such as problem-solving, meaning-seeking, acceptance, and cognitive reframing can perceive the threat of death as a natural part of life, without experiencing chronic anxiety or feelings of helplessness.

In a study by Ahmadi et al. (2017) on 180 older adults in Isfahan, problem-focused coping strategies were found to be inversely related to death anxiety. In contrast, emotion-focused strategies (such as denial or passivity) were positively associated with death anxiety. This finding is consistent with the study by Johnson et al. (2023), which demonstrated that active coping styles, by enhancing a sense of control and predictability, reduce existential anxiety.

Moreover, cognitive-behavioral theories emphasize that how individuals perceive and evaluate death plays a crucial role in the intensity of their anxiety. Older adults who view death as an ultimate threat and the absolute end of everything experience higher anxiety. In contrast, those who use strategies such as cognitive reframing to perceive death as a natural stage of life and a part of human meaning and development experience lower levels of death anxiety.

On the other hand, avoidance strategies, such as evading thoughts of death, excessive distraction, or denial, may temporarily reduce anxiety but exacerbate it in the long term. These coping styles disrupt the psychological adaptation process and prevent conscious engagement with the reality of death.

From a clinical perspective, enhancing effective coping strategies in older adults is considered a necessary intervention. Training these strategies through group counseling, psychological programs in elderly care centers, and educational media can reduce death anxiety while increasing life satisfaction, hopefulness, and psychological well-being. Strengthening these strategies, particularly for individuals who previously relied on maladaptive coping, can significantly improve their QoL.

Ultimately, the results of this hypothesis underscore the importance of focusing on coping styles in older adults. Since coping strategies can be learned and improved through practice and therapeutic interventions, enhancing these strategies can be expected to reduce death anxiety in the elderly population meaningfully—a need that becomes increasingly critical with the growing number of older adults in society.

Hypothesis 2

Hypothesis 2 states that resilience mediates the relationship between coping strategies and death anxiety in older adults. The path analysis results in this study indicated that resilience plays a significant mediating role between coping strategies and death anxiety. In other words, coping strategies have a direct effect on death anxiety, but much of this effect is explained through their influence on the level of resilience. This mediating model is particularly important in older adults, as effective coping during this stage of life, in interaction with resilience, plays a crucial role in emotion regulation and the reduction of existential anxiety.

Theoretically, Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model defines coping strategies as cognitive and behavioral responses to stressful situations. Strategies such as problem-solving, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring can enhance perceived control and meaning in life, thereby strengthening resilience and reducing death anxiety. Conversely, avoidance strategies, such as denial or evasion, weaken resilience and exacerbate feelings of helplessness, increasing death anxiety.

Goldstein et al. (2013) demonstrated that resilient individuals are not only more successful in selecting effective coping strategies but also experience fewer negative effects from stressful conditions. Older adults who employ active coping strategies generally have a more realistic perception of death, viewing it as a natural part of life rather than a threatening event.

A domestic study by Jeste et al. (2014) also showed that the relationship between coping styles and mental health is stable and positive only when individuals possess a high level of resilience. Essentially, resilience functions as a “psychological moderator” that enhances or diminishes the effectiveness of coping strategies. Without sufficient resilience, even adaptive strategies may become ineffective.

Additionally, in older adulthood, which is often accompanied by increased physical and social limitations, resilience can mediate the positive effects of active coping and mitigate the negative effects of avoidance coping. For example, an older adult using an “acceptance” strategy who also has a high level of resilience is better able to cope with the concept of death and experiences lower anxiety.

From a practical standpoint, these findings emphasize the need for integrated interventions. Without enhancing resilience, programs that focus solely on teaching coping strategies are unlikely to produce lasting reductions in death anxiety. In contrast, psychological interventions that simultaneously target effective coping and resilience enhancement (e.g. acceptance and commitment therapy or meaning-centered therapy) can have a deeper impact on older adults’ mental health.

In summary, these findings support a complex yet effective causal model in gerontological psychology: older adults’ coping strategies can effectively reduce death anxiety, provided they are accompanied by sufficient resilience. This model should be considered in the design of mental health programs for older adults.

Hypothesis 3

Hypothesis 3 states that resilience mediates the relationship between meaning in life and death anxiety in older adults. The path analysis results of the present study showed that resilience plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between meaning in life and death anxiety. In other words, older adults who perceive meaning, purpose, and value in their lives experience lower death anxiety through enhanced resilience. This finding is not only statistically significant but also strongly supported by theoretical and empirical evidence.

From the perspective of Frankl’s (1963) logotherapy, humans can interpret negative experiences positively, even under the most challenging life conditions, by finding meaning. This meaningful interpretation of life is a key factor in enhancing resilience. Older adults who experience purpose and value in life possess greater psychological flexibility, enabling them to accept challenges such as aging, illness, and death as natural parts of life.

Wong (2008), in his positive psychology of death theory, posits that “healthy mortality” is made possible through a meaningful life. He argues that resilient individuals draw on life’s meaningful resources, allowing them to respond to death with acceptance, calmness, and even a sense of liberation, rather than anxiety.

Practically, research shows that interventions aimed at helping older adults discover or reconstruct meaning in life can effectively enhance resilience. Ahmadi et al. (2017), using group meaning-centered therapy with older adults, found that this intervention not only reduced death anxiety but also significantly increased psychological resilience.

In conclusion, integrating meaning in life with strategies to strengthen resilience provides a comprehensive framework for effective psychological interventions in older adults. Activities such as life review, participation in volunteer or spiritual activities, and role redefinition can help older adults cultivate both meaning and resilience simultaneously, thereby alleviating death anxiety.

Conclusion

The present study highlights the critical roles of coping strategies, meaning in life, and resilience in shaping death anxiety among older adults. Problem-focused coping and a strong sense of life meaning are associated with lower death anxiety, while emotion-focused coping can increase it, particularly when resilience is low. Resilience functions as a key mediator, explaining how coping strategies and meaning in life influence the experience of death anxiety. Overall, coping strategies, meaning in life, and resilience together account for 62% of the variance in death anxiety among the elderly, emphasizing their practical importance in psychological interventions.

These findings underscore the need for interventions targeting both enhancement of adaptive coping strategies and resilience-building programs, along with activities that promote meaningful engagement in life. Such combined approaches can significantly reduce death anxiety and improve psychological well-being, offering actionable insights for clinicians, caregivers, and policymakers working with aging populations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethcis Committee of Arak Branch, Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.ARAK.REC.1403.114).

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD Dissertation of Esmaeil Bana, approved by the Faculty of Islamic Education, Arak Branch, Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Ahangarzadeh, R. S., & Rasoli, M. (2015). [Psychometric properties of the persian version of "conner-davidson resilience scale" in adolescents with cancer (Persian)]. Nursing And Midwifery Journal, 13(9), 739-747. [Link]

Ahmadi, S., Bagheriyan, F., Heidari, M., & Kashfi, A. (2017). [Elderly and meaning in life: Field study of sources and dimensions of meaning in old women and men (Persian)]. Psychological Achievements, 23(1), 1-22. [Link]

Anderson, J. R. (2020). Cognitive psychology and its implications. New York: Worth Publishers. [Link]

Averill, J. R. (1980). A constructivist view of emotion. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (pp. 305-339). Cambridge: Academic Press. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-558701-3.50018-1]

A'zami, Y., Mo'tamedi, A., Doostian, U., Jalalvand, M., & Farzanwgan, M. (2012). PThe role of resiliency, spirituality, and religiosity in predicting satisfaction with life in the elderly (Persian)]. Counseling Culture and Psycotherapy, 3(12), 1-20. [DOI:10.22054/qccpc.2011.5906]

Bahar, A., Shahriary, M., & Fazlali, M. (2021). Effectiveness of logotherapy on death anxiety, hope, depression, and proper use of glucose control drugs in diabetic patients with depression. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 12, 6. [DOI:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_553_18] [PMID]

Bakhshi, P., Pashang, J., & Jafari, G. S. (2020). A model of psychological well-being in the elderly based on hope for life with the mediation of death anxiety (Persian)]. Iranian Quarterly of Health Education and Promotion, 8(3), 283-293. [DOI:10.29252/ijhehp.8.3.283]

Baqutayan, S. M. S. (2015). Stress and coping mechanisms: A historical overview. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 479-488. [Link]

Bitarafan, L., Kazemi, M., & Yousefi Afrashte, M. (2018). [Relationship between styles of attachment to god and death anxiety resilience in the elderly (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing, 12(4), 446-457. [DOI:10.21859/sija.12.4.446]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Link]

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: Science and practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The connor‐davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82. [DOI:10.1002/da.10113] [PMID]

Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. (1990). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 844–854. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844]

Frankl, V. E. (1963). Man’s search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press. [Link]

Ghoreyshi Rad, F. (2010). [Validation of Endler & Parker coping scale of stressful situations (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 4(1), 1-7. [Link]

Goldstein, A. L., Faulkner, B., & Wekerle, C. (2013). The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 22–32. [DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007] [PMID]

Hashemi Razini, H., Baheshmat Juybari, S., & Ramshini M. (2017). [Relationship Between Coping Strategies and Locus of Control With the Anxiety of Death in Old People (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing, 12 (2), 232-241. [DOI:10.21859/sija-1202232]

Hoelterhoff, M. (2010). Resilience against death anxiety in relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric co-morbidity[PhD dissertation]. Plymouth: University of Plymouth. [Link]

Jangi Jahantigh, L., Latifi, Z., & Soltani-Zadeh, M. (2022). [Effectiveness of self-healing training on death anxiety and sleep quality in elderly women residing in a nursing home in Isfahan (Persian)]. Salmand, 17(3), 380-397. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2022.3319.1]

Jeste, D. V., Savla, G. N., Thompson, W. K., Vahia, I. V., Glorioso, D. K., Martin, A. V. S., et al. (2013). Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 188-196. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386] [PMID]

Johnson, K. M., Smith, L., & Brown, T. (2023). Social support seeking as a learned coping skill: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 123–140.

Kirmizioglu Y, Doğan O, Kuğu N, Akyüz G. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among elderly people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009; 24(9), 1026-1033. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2215] [PMID]

Livarjani, S., Najjarpour, O. S., Zafaranchi, M., & Asamkhani, A. H. (2015). [The study of relationship between general health, coping strategies and identity styles (Persian)]. Woman & Study of Family, 7(28), 93-113. [Link]

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Press. [Link]

MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Hawkins, K., Alsgaard, K., & Wicker, E. R. (2016). The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), 266–272. [DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014] [PMID]

Mahmoudi-Mahan, D., & Dasht Bozorgi, D. (2022). [The mediating role of quality of life in the relationship between life meaning and sense of coherence with death anxiety in the elderly of Ahvaz (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Health Psychology and Social Behavior, 1(2), 73-86. [Link]

Masraabadi, J., Ostovar, N., & Jafarian, S. (2013). [Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 83-90. [Link]

Mohammadpour, A., Sadeghmoghadam, L., Shareinia, H., Jahani, S., & Amiri, F. (2018). Investigating the role of perception of aging and associated factors in death anxiety among the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 405-410. [Link]

Myers, R. H., Montgomery, D. C., Vining, G. G., & Robinson, T. J. (2012). Generalized linear models: With applications in engineering and the sciences. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Link]

Peters, L., Cant, R., Payne, S., O'Connor, M., McDermott, F., & Hood, K., et al. (2013). How death anxiety impacts nurses' caring for patients at the end of life: A review of literature. The Open Nursing Journal, 7, 14–21. [DOI:10.2174/1874434601307010014] [PMID]

Pourdad, S., Momeni, K., & Karami, J. (2019). [Death anxiety and its relationship with social support and gratitude in older adults (Persian)]. Salmand, 14(1), 26-39. [DOI:10.32598/sija.13.10.320]

Rajabi, Gh., & Bahrani, M. (2002). [ITEM Factor Analysis Of The Death Anxiety Scale (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology, 5(4), 331-344. [Link]

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The mean- ing in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80- 93. [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80]

Templer, D. I. (1970). The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. Journal of General Psychology, 82(2), 165-177. [PMID]

Vaziri-Tabar, H., Ahadi, M., & Ahadi, H. (2022). [Meta-analysis of spiritual factors related to death anxiety in the elderly in Iranian studies (Persian)]. Research in Religion and Health, 8(4), 129-143. [DOI:10.22037/jrrh.v8i4.35742]

Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes (pp. 65-87). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Link]

Yohannes, A. M., Baldwin, R. C., & Connolly, M. J.(2008). Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in elderly patients admit-ted in post-acute intermediate care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(11), 1141-7. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2041]

Zyga, S., Mitrousi, S., Alikari, V., Sachlas, A., Stathoulis, J., & Fradelos, E., et al. (2016). Assessing factors that affect coping strategies among nursing personnel. Materia Socio-Medica, 28(2), 146-150. [DOI:10.5455/msm.2016.28.146-150] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Rehabilitation

Received: 2025/04/13 | Accepted: 2025/09/15 | Published: 2026/12/28

Received: 2025/04/13 | Accepted: 2025/09/15 | Published: 2026/12/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |