Volume 12, Issue 2 (Spring 2024)

PCP 2024, 12(2): 189-200 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Seifi H, Tabrizi M, Asadzade H. Teaching Cognitive Behavioral Techniques on Attachment Styles, Mental health, and Optimism in Medical Students at Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran. PCP 2024; 12 (2) :189-200

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-914-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-914-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabatabai University, Tehran, Iran. , hajar.seifi38@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 618 kb]

(2034 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2457 Views)

Full-Text: (625 Views)

Introduction

The rigorous nature of medical training leads to increased stress levels in medical students, which is normal compared to students in other fields of study and the general population (Colonnello et al., 2022). Many authors widely confirm that the medical field should be aware of the high prevalence of mental health problems, such as mood disorders, anxiety, and psychological distress in medical students (Esmat et al., 2021). Medical education involves producing competent and mentally healthy physicians to meet the physical and psychological health needs of their patients with empathy and professionalism. However, students in the early stages of their medical studies showed a decline in mental health and maintained this state throughout their studies. The reasons for the anxiety are numerous, including high academic pressure, excessive workload, financial difficulties, lack of sleep, and excessive free time (Haykal et al., 2022). A recent study conducted around the world found that more than 25% of medical students felt depressed, and 11.1% had suicidal thoughts (Rotenstein et al., 2016).

Extensive literature has shown the importance of attachment security for the psychological well-being of medical students (Calvo et al., 2022). According to the attachment theory, individual differences in activity patterns and, thus, adult attachment orientations are associated with distinct patterns of coping styles and coping strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). The study revealed that secure attachment is the dominant manner in which people establish connections with one another. Medical students could find this attachment style highly advantageous as it enables them to effectively manage stressful situations (Moghadam et al., 2016). In other words, people with different attachment styles use different strategies to regulate emotions and process information (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). The results of a study conducted by Moghadam et al., (2016) indicate a relationship between attachment style and feelings of environmental control and dominance (Moghadam et al., 2016). Zilcha-Mano also found that people with an insecure attachment style have limited interpersonal relationships due to their inability to dominate their environment and establish positive relationships (Zilcha-Mano, 2019).

Additionally, there is a high prevalence of mental health issues among medical students, which is a cause of concern for healthcare professionals and educators (Vitorino et al., 2022). The unique circumstances faced by students, such as being away from their family, being part of a large and stressful group, facing economic difficulties, and having limited income, as well as a demanding curriculum and intense competition, make them more vulnerable to mental health deterioration. As a result, it is crucial to teach coping mechanisms to address these challenges (Deng et al., 2022). Moreover, academic pressure, sleep deprivation, social and familial expectations, financial hardships, and constant exposure to patient suffering and death further contribute to the psychological distress experienced by students, leading to depressive symptoms and declining mental health (Boni et al., 2018). Previous research has found a high prevalence of psychological distress among healthcare university students in Tunisia and identified specific protective factors that can be targeted to reduce mental health problems (Krifa et al., 2022).

Krifa et al. demonstrated that optimism mediates the effects of protective factors on reducing mental health problems (Krifa et al., 2022). Optimism is considered a psychological resource and has been consistently linked with improved well-being and physical health in studies (Chu et al., 2022). It also predicts lower levels of anxiety and depression in cancer patients (Mo et al., 2022) and better sleep quality in the general population (Hernandez et al., 2020). Optimism refers to having a positive attitude and is a concept within the realm of positive psychology. It can be intrinsic to an individual’s temperament, with some naturally possessing a more positive outlook on life; on the other hand, it can also be acquired through certain experiences (Singh & Jha, 2013).

In addition, mental health issues are prevalent among medical students, which is a concern for healthcare professionals and educators (Vitorino et al., 2022). The unique circumstances that student face, such as being away from family, participating in a large and stressful group, economic problems, insufficient income, numerous courses, and intense competition, make them vulnerable to mental health deterioration. Accordingly, teaching techniques that help students cope with these conditions are vital at this stage (Deng et al., 2022). The academic pressure, sleep deprivation, social and family expectations, financial difficulties, and daily exposure to patient suffering and death also contribute to the psychological distress experienced by students, leading to depressive symptoms and deteriorating mental health (Boni et al., 2018).

Accordingly, recent experimental studies have examined interventions aimed at increasing attachment security and their positive effects on mental health and optimism (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). The six articles included in this series provide examples of how cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, primarily designed for outpatient mental health settings, can be adapted for specialized medical settings. They also discuss specific considerations and recommendations for its implementation (Magidson & Weisberg, 2014). Group CBT sessions effectively alleviate depression, anxiety, and stress, except for self-esteem. Therefore, further research could explore these findings by expanding the population to include different majors (Changklang & Ranteh, 2023). Additionally, the findings suggest that CBT for panic has implications for attachment representations (Zalaznik et al., 2019). The results indicate that CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety, hardiness, and self-efficacy. By managing anxiety, students’ levels of hardiness and self-efficacy can be increased, enabling them to better cope with the various challenges in their lives (Sahranavard et al., 2019). Furthermore, CBT techniques improve women’s optimism by focusing on communication and conflict resolution skills, leading to a positive attitude and life satisfaction (Dafei et al., 2021).

As a result, medical students must be educated on this subject to handle risky situations in their lives. Additionally, the research gap is centered on the insufficient evidence of psychological interventions to enhance the effectiveness of variables that impact the mental health of medical students. Hence, incorporating the variables mentioned above into this group is novel. The researcher determined that the use of CBT techniques could have a positive impact on the mental health of medical students by altering their attachment style within the research context mentioned above.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

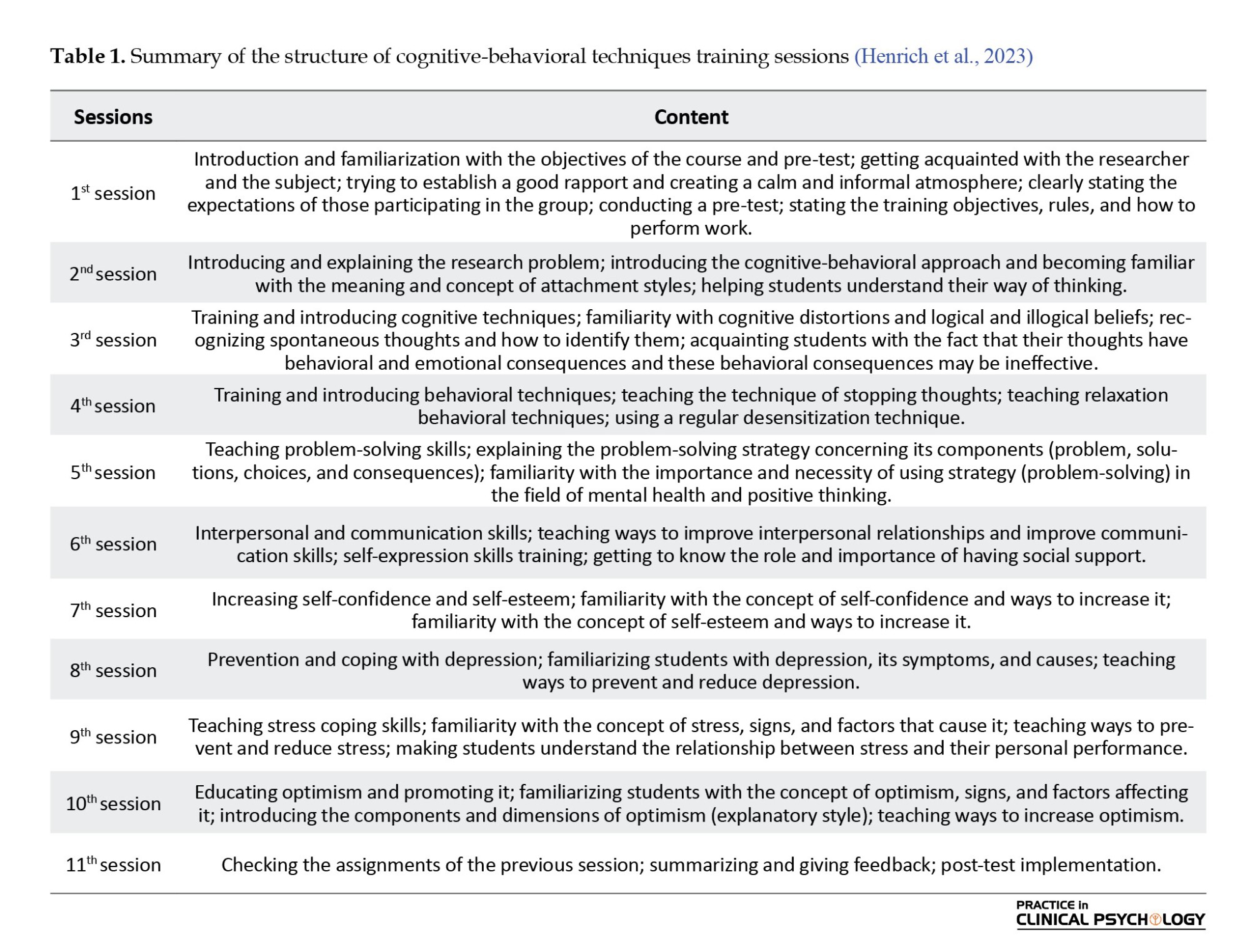

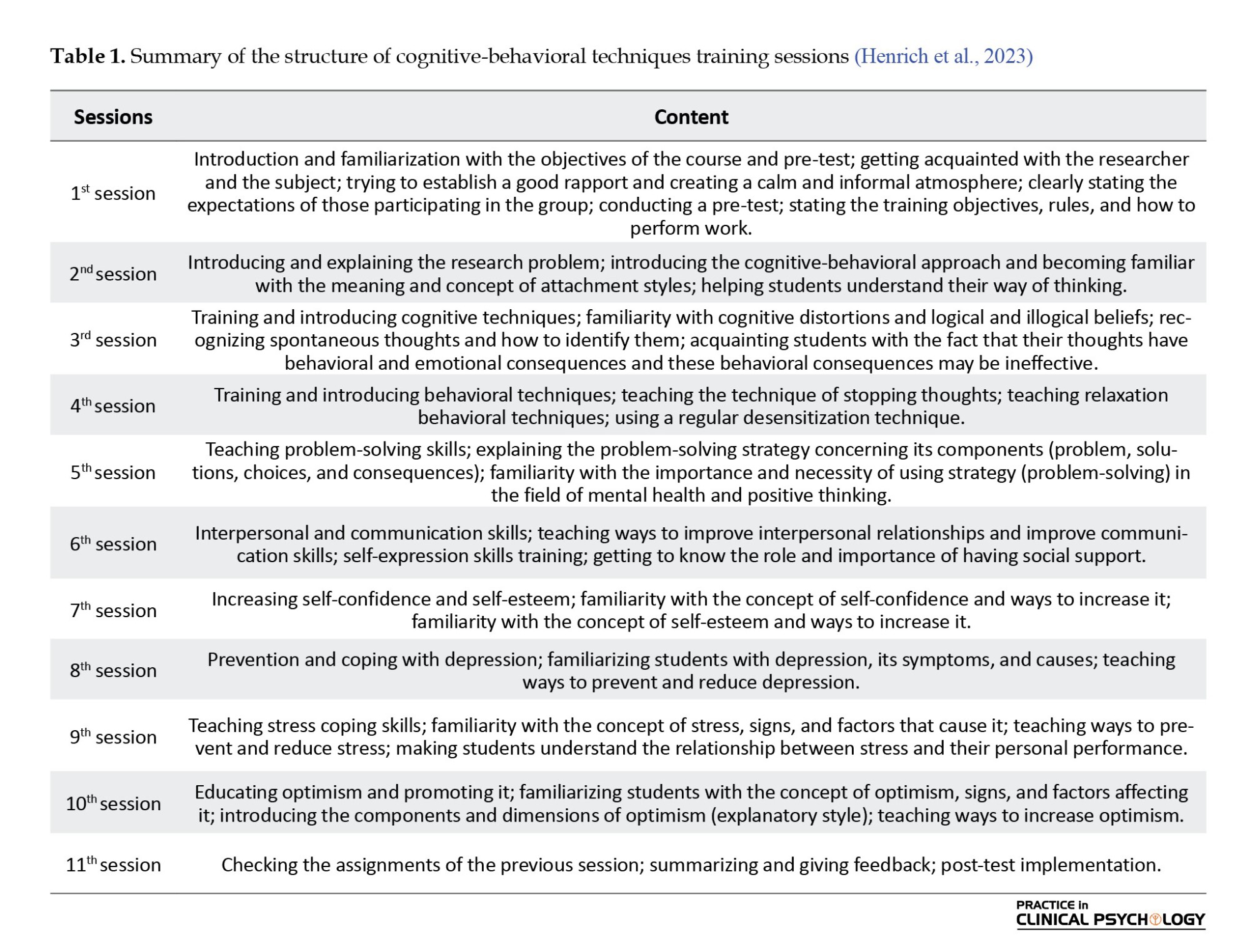

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pre-test and post-test design with a control group. The statistical population included all medical students of Islamic Azad University from 2019 to 2020 in Mashhad City, Iran. A total of 30 medical students were selected via the purposeful sampling method. Then, through a random number table, the participants were divided into two experimental groups and one control group (n=15 in each group). The required sample size was calculated based on an effect size of 0.40, a power level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. The distribution of the attachment styles questionnaire was conducted to obtain a sample from students who answered the advertised call and were willing to participate in training on CBT techniques (Table 1).

Following the researcher receiving approval to conduct research from the Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, they submitted an application to the university's Medical Sciences Faculty. Subsequently, the attachment-style questionnaire was provided to the students who agreed to participate. A total of 30 individuals with insecure attachment styles were chosen for the study after the test. Next, the envelopes were unsealed, and the study participants were divided into two groups: One control group comprising 15 individuals and an experimental group with 15 individuals to analyze the data statistically. The faculty’s education officer coordinated the CBT course and its arrangement. The department’s education manager coordinated a cognitive-behavioral engineering education course and its location. For 5 weeks, each session was held for 70 min on Tuesdays and Thursdays. During the initial meeting of the training program, it was revealed that the course was developed in conjunction with the university faculty to investigate this matter.

Medical students were asked about their willingness to participate in these meetings. Medical students expressed their willingness and desire to participate in meetings with researchers. Before implementing the independent variable, the experimental and control groups were assessed using a pre-test administered by a 28-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) and life orientation test-revised (LOT-R) as compared to their previous attempts. The experimental group was given CBT training, which was an independent variable, while the control group did not receive any training. Following the training, the experimental and control groups were re-evaluated with a post-test to assess the influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

The experimental groups were involved with researchers and students bilaterally discussing issues, followed by students completing homework and engaging in activities. The researchers also inquired about the training’s potential effects on the students. The majority of students had a positive outlook on this training. The analysis of the data was carried out using the SPSS software along with descriptive statistics (Mean±SD), independent t-test, and inferential statistics for analysis covariance. The independent t-test was used to compare the pre-test scores of both the control and experimental groups. At the same time, the analysis of the covariance method was employed to determine the effects of training in CBT techniques on attachment styles, mental health, and optimism.

Attachment style questionnaire

Shaver and Hazen (1987) developed the attachment style questionnaire (ASQ), and it was adapted for use in Iran with students from Tehran University. This survey consists of 15 items, with five items devoted to secure, avoidant, and ambivalent attachment styles. The questionnaire uses a scoring system ranging from very low (score=1) to very high (score=5), and the scores for the attachment subscales are calculated by averaging the responses to the five questions for each subscale. Five items represent each attachment style (secure, avoidant, and ambivalent). Shaver and Hazen (1987) reported a reliability coefficient of 0.8 for the entire questionnaire and a Cronbach α of 0.78. They also found proper face and content and construct validity. Rahimian Boogar et al. (2007) obtained favorable reliability coefficients for the entire questionnaire and the ambivalent, avoidant, and secure styles, with Cronbach α values of 0.75, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.77, respectively. In the present study, the Cronbach α for the entire questionnaire was 0.71.

The 28-item general health questionnaire

To evaluate the effect of the psychosocial intervention on individuals’ well-being, we chose the GHQ-28 as the leading indicator of outcomes. Our decision was influenced by the results of a previous study and the tool’s effectiveness in measuring emotional stress (Goldberg & Williams, 1988). The GHQ-28 requires participants to rate their general health over the past few weeks using behavioral items based on a 4-point scale, indicating the frequency of their experiences as follows: “Not at all,” “no more than usual,” “rather more than usual,” and “much more than usual.” The scoring system used in this study was consistent with the original Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. The minimum score on the 28-item version is 0, while the maximum score is 84. Higher scores on the GHQ-28 indicate higher levels of distress (Goldberg & Hillier, 1979). Goldberg suggests that individuals with total scores of 23 or lower may be considered non-psychiatric, while subjects with scores higher than 24 may be classified as psychiatric. However, this threshold is not an absolute cutoff, and it is recommended that researchers establish their cutoff score based on the mean of their specific sample (Goldberg et al., 1998). The Iranian version of the GHQ-28 used in this study demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach α, split-half coefficients, and test re-test reliability coefficients of 0.9, 0.89, and 0.58, respectively (Malekooti et al., 2006). In our study, the Persian version had an internal consistency of 0.78.

The life orientation test-revised questionnaire

The researchers utilized the LOT-R to assess dispositional optimism (Scheier et al., 1994). This test consists of 10 items for participants to complete, with four of the items serving as filler to conceal the test’s true purpose to some extent. Three scoring elements are created with a positive sentiment, while the remaining three are crafted with a negative viewpoint. Each item is designed to prevent suggesting any particular reason for the anticipation, regardless of whether it originates from the person, the surroundings, or mere chance and external elements. Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each item based on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4), based on their present circumstances. The total score is determined by summing the raw scores from the optimism items and the inverted raw scores from the pessimism items. Scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater optimism and lower scores denoting lower optimism, commonly referred to as pessimism. To translate the LOT-R into Norwegian for this study, multiple forward and backward translation technique was employed. The internal consistency of the Persian version used in this research yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.76.

Results

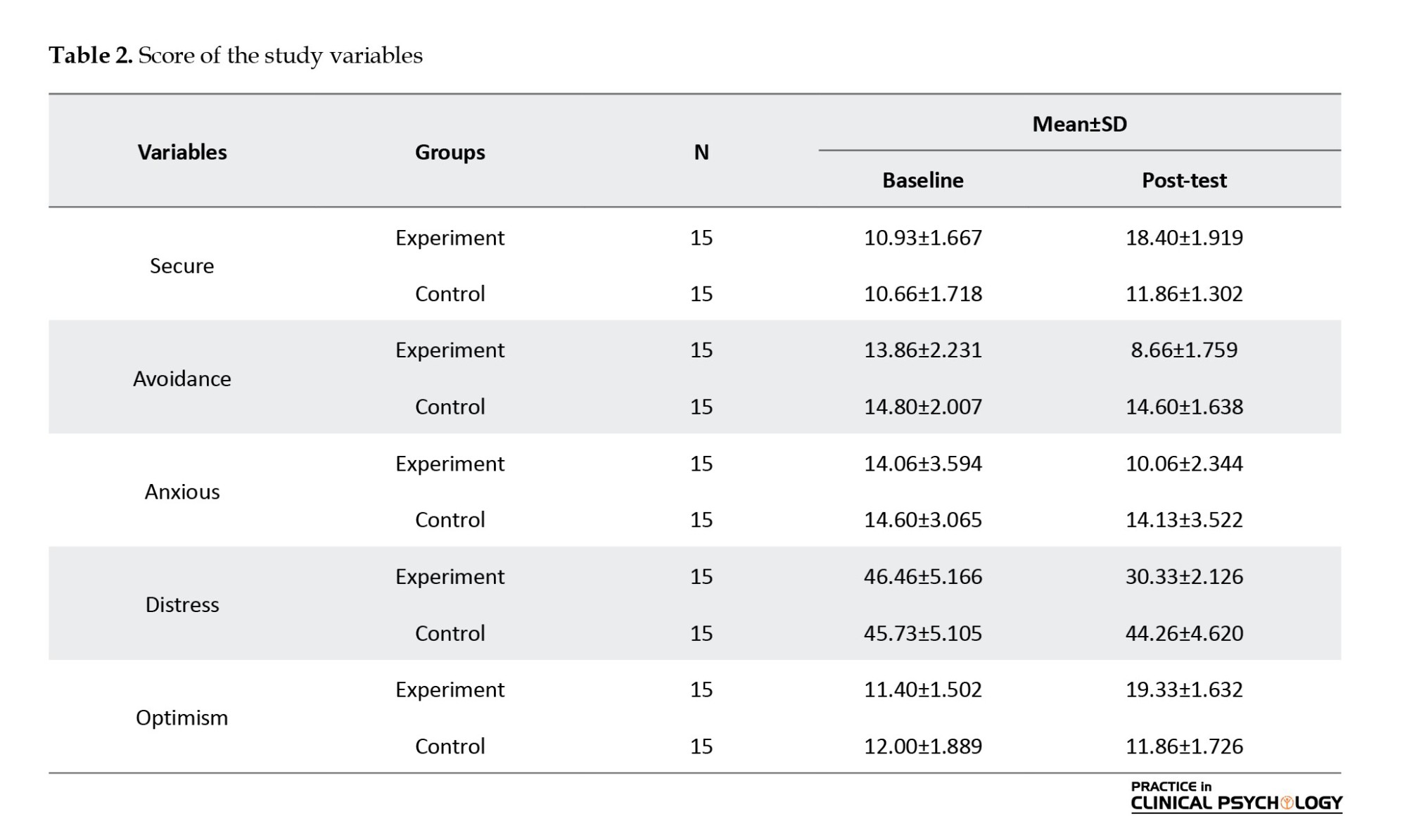

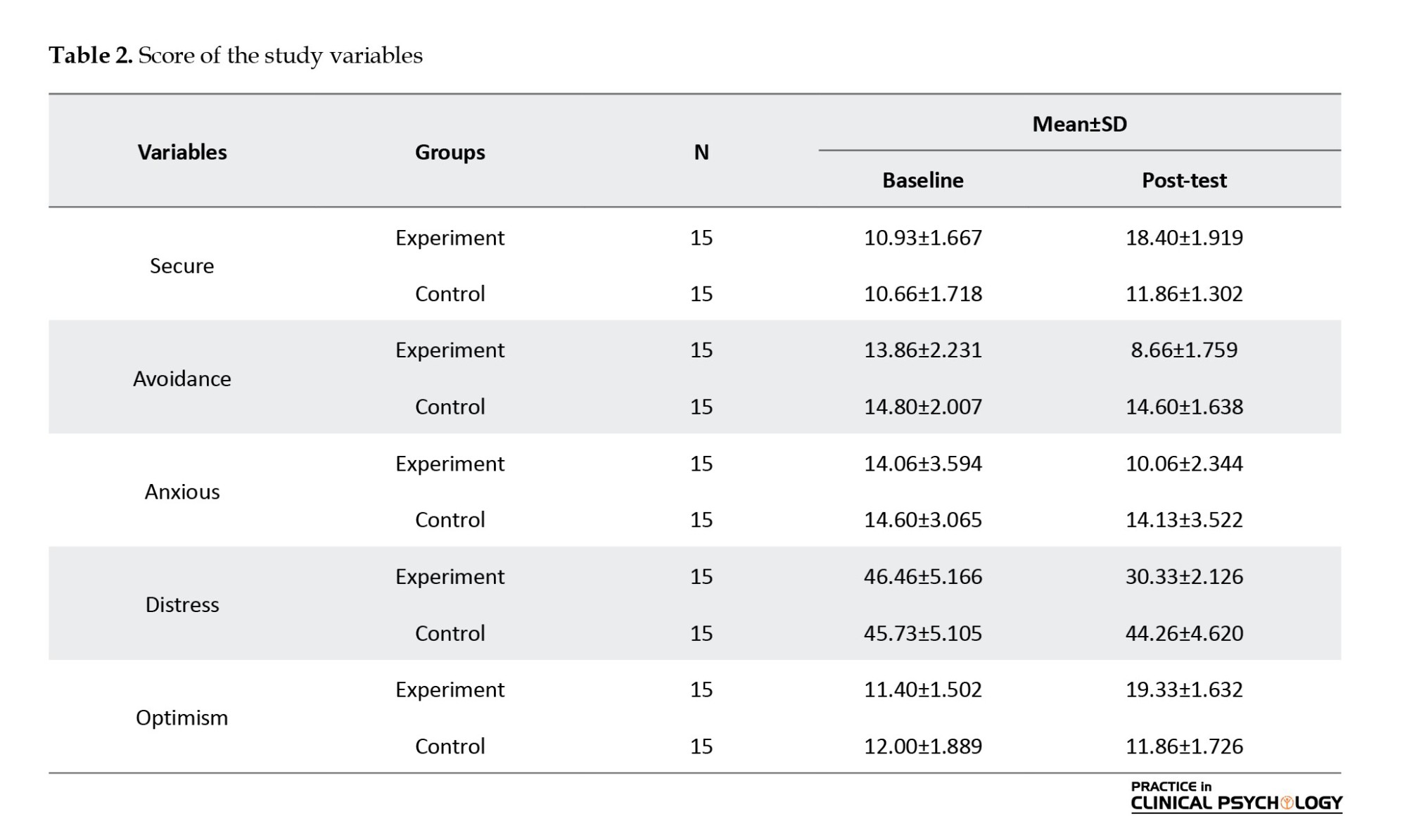

Thirty medical students with a mean age of 31.39±5.37 years participated in this study. In terms of marital status, 20% were single and 70% married. The Mean±SD of the study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 As can be seen, the mean score of the secure domain at baseline were not significantly different in between intervention and control groups. The mean score of secure increased in the post-test phase in the intervention group compared to the control group. Also, the mean scores of avoidance and anxious domains were not significantly different between intervention and control groups at baseline. However, their scores in decreased in the post-test phase in the intervention group, compared to the control group. The scores in the control group did not change significantly.

The mean scores of distress variable (GHQ-28 score) were not significantly different between the two groups at baseline either. In the post-test phase, its score in the intervention group decreased compared to the control group, indicating that the mental health level increased in the intervention group. Finally, the mean score of dispositional optimism variable (LOT-R score) in the intervention group increased in the post-test phase compared to baseline, while no change in the scores of the control group were reported.

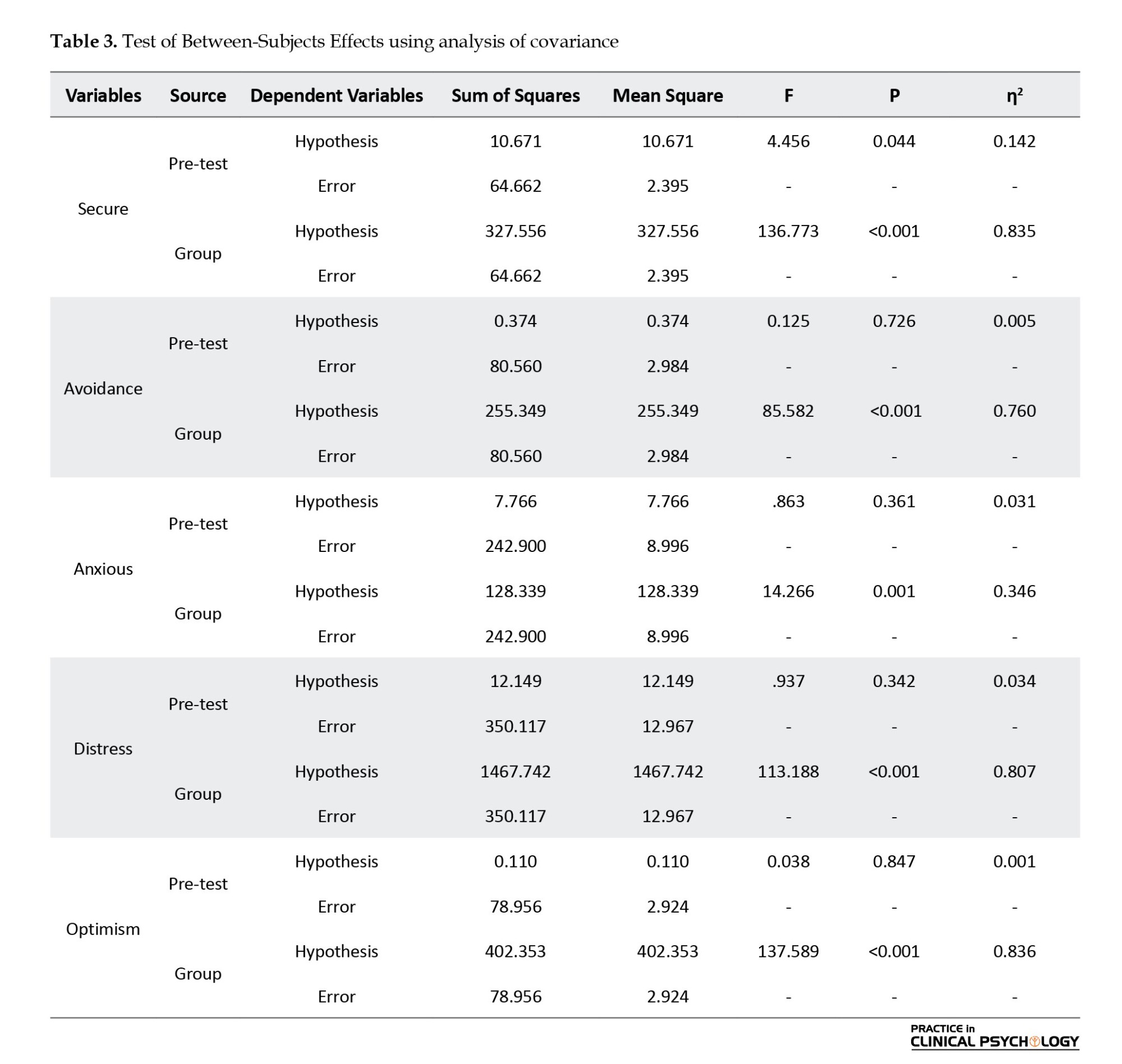

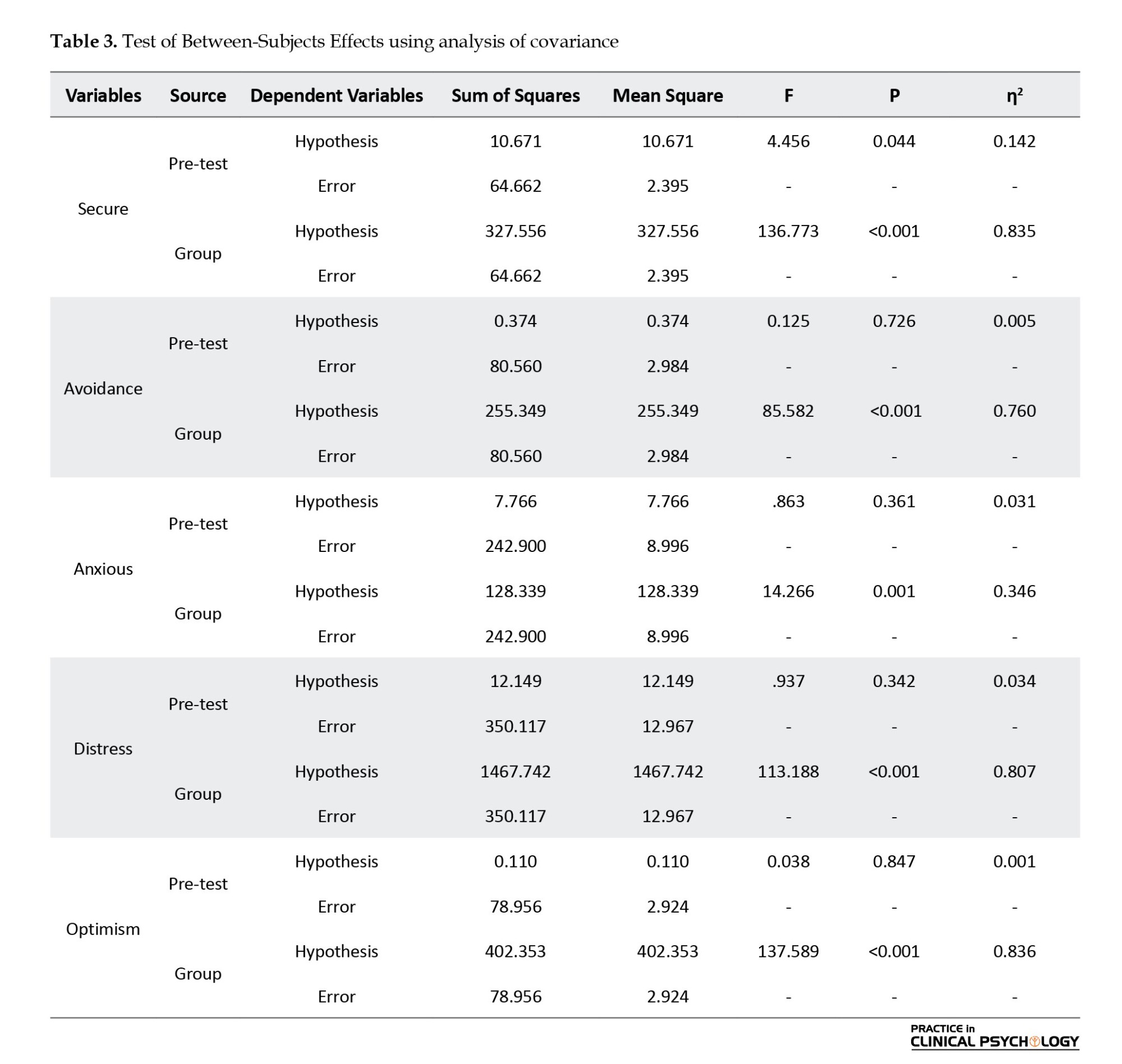

The results of the analysis of covariance are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, there was a significant difference in secure (P<0.001, η2=83.5%), avoidance (P<0.001, η2=76%), and anxious (P=0.001, η2 =34.6%) between the groups over time.

Moreover, there was a significant difference in distress (P<0.001, η2=80.7%) and dispositional optimism (P<0.001, η2=83.6%) between the groups over time. Table 4 presents the results for testing within-subjects effects. According to the results, since the P<0.05 in all study variables, it can be said that there was a significant difference between the two evaluation phases. Overall, it can be said that there was a significant difference in attachment style, mental health and optimism between the two intervention and control groups after removing the effect of the pre-test score. Therefore, the CBT caused significant changes in the levels of attachment style, mental health and optimism of medical students.

Discussion

This research assessed the efficacy of CBT in changing attachment style, enhancing mental well-being, and promoting optimism among medical university students. The findings of the study, as revealed by the multivariate analysis of covariance, indicated that the mean scores for attachment style were significantly different between the group of students who received the educational intervention and the control group. The utilization of CBT proved effective in modifying the attachment styles of the students. These results are in line with the findings of previous studies (Zalaznik et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2021; Anvari et al., 2022). Furthermore, insecure attachment predicted a negative longitudinal trajectory of eating disorder psychopathology, which indirectly contributed to increased levels of body uneasiness, as supported by mediation analyses. A study by Rossi et al. (2022) confirmed the well-established effectiveness of enhanced CBT in individuals with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

Training in CBT can impact how individuals perceive and express secure attachment in close relationships. This influence may arise due to the required energy and time commitment, which can consequently affect personal life and close relationships. These reciprocal influences align with previous understandings of attachment, which encompass both trait and state components. While attachment is considered moderately stable throughout one’s lifetime, the influence of various life circumstances on attachment has also been acknowledged (Darban et al., 2020).

Attachment theory examines how an individual’s dominant attachment style (secure or insecure) influences their ability to engage in safe and secure relationships and experience internal feelings of safety. By identifying an individual’s predominant attachment style, a person can assess how it might hinder their capacity to develop close, healthy relationships. This awareness allows them to make changes that promote greater closeness with others and cultivate a sense of security within themselves. Additionally, understanding the underlying reasons and purposes of a particular attachment style enables individuals to heal past emotional wounds and traumas (Fearon & Roisman, 2017).

Increasing attachment security yields positive effects on mental health and prosocial behavior (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Additionally, medical students with an anxious attachment style and limited access to emotion regulation strategies are impacted (Colonnello et al., 2022). Darban et al., (2020) found that attachment style predicts the quality of life among students and suggested that focusing on attachment style could serve as an intervention avenue to improve the well-being of medical students and establish a basis for long-term monitoring. To develop such interventions, the initial step is to examine the specific characteristics of healthcare students who may be experiencing psychological distress and identify potential protective factors in this population. Numerous protective factors have been identified that can enhance student well-being and mitigate the impacts of risk factors on student stress and psychological distress (Magidson & Weisberg, 2014).

In addition, the results indicated that CBT has the potential to enhance the mental well-being of medical students. Previous research findings are in line with the rephrased outcome, as stated by Magidson and Weisberg in 2014 and Sahranavard et al., 2019. Magidson & Weisberg, (2014) explained that specialty medical care utilizing CBT may directly target various psychological symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, aiming to improve overall functioning and quality of life and address cognitive and behavioral aspects relevant to managing a medical condition. Muller and Yardley (2011) conducted a comprehensive analysis and systematic review of the impact of telehealth-delivered CBT on medical populations, examining studies that assessed the effects of telehealth-delivered CBT on physical health outcomes. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that CBT yielded significant improvements in physical health outcomes, characterized by a small to medium effect size. It was particularly effective for patients with chronic conditions that were not immediately life-threatening. Furthermore, considering gender, the majority of participants who received CBT therapy were female (90.3%). This dominance aligns with the two-to-one female-to-male depression prevalence ratio (Changklang & Ranteh, 2023). When anxiety levels rise in students, their ability to manage situations, adapt, cope, and confront challenges diminishes over time, resulting in increased anxiety. Consequently, these students become less optimistic about their future and their problem-solving abilities. As a result, their academic performance and dormitory life may be disrupted. Conversely, by effectively managing anxiety and stress, students can enhance their problem-solving abilities and overall mental well-being. The findings of this study will aid students in improving their mental health through stress management techniques (Sahranavard et al., 2019).

The authors discuss how training in CBT introduces students to the concepts related to mental health. By utilizing these techniques, students learn to view the situations they encounter as problems that can be solved. The course covers various approaches to problem-solving, enabling participants to feel more in control of their environment and perceive difficult situations as less daunting. Consequently, individuals will be better equipped to effectively manage life events by acquiring the necessary coping skills, which can contribute to improved mental health. Moreover, one of the factors contributing to poor mental health is perceiving situations as threatening. By learning to identify and challenge spontaneous negative thoughts through this course, participants have the opportunity to reassess and modify these thoughts. Additionally, relaxation training assists individuals in achieving a state of relaxation by counteracting the symptoms of stress, thereby allowing them to have a greater ability to control their emotions.

The instruction of CBT can boost students’ optimism. This finding is in line with previous research conducted by Geschwind et al. (2019), Dafei et al., (2021), and Moloud et al., (2022). According to Moloud et al., optimism and self-esteem significantly increased among the CBT group following the intervention. However, these levels decreased in the long term due to the discontinuation of CBT sessions (Moloud et al., 2022). Optimism is considered an essential psychological resource and has consistently been associated with significant positive emotions and decreased negative psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression (Öcal et al., 2022; Chung et al., 2023). Optimistic individuals tend to reframe challenging situations as opportunities in disguise, leading to higher psychological and mental well-being during difficult times (Chu et al., 2022).

Managing mental stress can be achieved by practicing positive thinking and refraining from entertaining negative thoughts. Maintaining a positive mood enhances cognitive processing abilities, promotes altruism, and boosts self-esteem. Optimistic individuals tend to outperform pessimistic individuals in various areas of life, experiencing more success and enjoying greater social fulfillment. The central focus of CBT lies in understanding emotions, behavior, and cognitive representations of experiences, shaping the foundation of personality development, and addressing pathological cognitive patterns. The primary objective of cognitive-behavioral assessment is to establish a treatment plan and achieve regulation. It is worth mentioning that cognitive-behavioral techniques are typically learned through collective activities, potentially benefiting from the positive dynamics of a group and addressing general challenges associated with interpersonal relationships.

Conclusion

After analyzing the findings, it was determined that the CBT group displayed a significant improvement in their secure attachment style, mental health level, and optimism following the intervention. Consequently, it is vital to implement regular CBT sessions for medical students who have insecure attachments to address this issue effectively.

Study limitations

One limitation of this study is the researcher’s inability to control the motivation and cooperation of the subjects when answering the questionnaire, which may impact the study’s results. Additionally, demographic characteristics, including economic, social, and cultural status, are outside the researcher’s control and may influence the outcomes. Based on the findings from this study, future researchers are advised to conduct similar studies with larger sample sizes, explore different research domains, increase the number of meetings and meeting duration for more effective interventions, and examine group and individual differences that may impact the success of executive programs to cater to diverse backgrounds. To validate the intervention’s impact and its benefits on the control group, it is recommended to apply this method to the control group as well, assessing its effects on attachment style, health psychology, and optimism. Further trials should also be conducted to assess the stability of the intervention effect and confirm the training’s effectiveness.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article observed all the ethical guidelines. The individuals participating were informed of the purpose and methodology behind the research. The participants were assured that their data would be kept confidential, and they had the option to withdraw from the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Hajar Seifi, approved by the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabataba’i University.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who took part in this study.

References

The rigorous nature of medical training leads to increased stress levels in medical students, which is normal compared to students in other fields of study and the general population (Colonnello et al., 2022). Many authors widely confirm that the medical field should be aware of the high prevalence of mental health problems, such as mood disorders, anxiety, and psychological distress in medical students (Esmat et al., 2021). Medical education involves producing competent and mentally healthy physicians to meet the physical and psychological health needs of their patients with empathy and professionalism. However, students in the early stages of their medical studies showed a decline in mental health and maintained this state throughout their studies. The reasons for the anxiety are numerous, including high academic pressure, excessive workload, financial difficulties, lack of sleep, and excessive free time (Haykal et al., 2022). A recent study conducted around the world found that more than 25% of medical students felt depressed, and 11.1% had suicidal thoughts (Rotenstein et al., 2016).

Extensive literature has shown the importance of attachment security for the psychological well-being of medical students (Calvo et al., 2022). According to the attachment theory, individual differences in activity patterns and, thus, adult attachment orientations are associated with distinct patterns of coping styles and coping strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). The study revealed that secure attachment is the dominant manner in which people establish connections with one another. Medical students could find this attachment style highly advantageous as it enables them to effectively manage stressful situations (Moghadam et al., 2016). In other words, people with different attachment styles use different strategies to regulate emotions and process information (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). The results of a study conducted by Moghadam et al., (2016) indicate a relationship between attachment style and feelings of environmental control and dominance (Moghadam et al., 2016). Zilcha-Mano also found that people with an insecure attachment style have limited interpersonal relationships due to their inability to dominate their environment and establish positive relationships (Zilcha-Mano, 2019).

Additionally, there is a high prevalence of mental health issues among medical students, which is a cause of concern for healthcare professionals and educators (Vitorino et al., 2022). The unique circumstances faced by students, such as being away from their family, being part of a large and stressful group, facing economic difficulties, and having limited income, as well as a demanding curriculum and intense competition, make them more vulnerable to mental health deterioration. As a result, it is crucial to teach coping mechanisms to address these challenges (Deng et al., 2022). Moreover, academic pressure, sleep deprivation, social and familial expectations, financial hardships, and constant exposure to patient suffering and death further contribute to the psychological distress experienced by students, leading to depressive symptoms and declining mental health (Boni et al., 2018). Previous research has found a high prevalence of psychological distress among healthcare university students in Tunisia and identified specific protective factors that can be targeted to reduce mental health problems (Krifa et al., 2022).

Krifa et al. demonstrated that optimism mediates the effects of protective factors on reducing mental health problems (Krifa et al., 2022). Optimism is considered a psychological resource and has been consistently linked with improved well-being and physical health in studies (Chu et al., 2022). It also predicts lower levels of anxiety and depression in cancer patients (Mo et al., 2022) and better sleep quality in the general population (Hernandez et al., 2020). Optimism refers to having a positive attitude and is a concept within the realm of positive psychology. It can be intrinsic to an individual’s temperament, with some naturally possessing a more positive outlook on life; on the other hand, it can also be acquired through certain experiences (Singh & Jha, 2013).

In addition, mental health issues are prevalent among medical students, which is a concern for healthcare professionals and educators (Vitorino et al., 2022). The unique circumstances that student face, such as being away from family, participating in a large and stressful group, economic problems, insufficient income, numerous courses, and intense competition, make them vulnerable to mental health deterioration. Accordingly, teaching techniques that help students cope with these conditions are vital at this stage (Deng et al., 2022). The academic pressure, sleep deprivation, social and family expectations, financial difficulties, and daily exposure to patient suffering and death also contribute to the psychological distress experienced by students, leading to depressive symptoms and deteriorating mental health (Boni et al., 2018).

Accordingly, recent experimental studies have examined interventions aimed at increasing attachment security and their positive effects on mental health and optimism (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). The six articles included in this series provide examples of how cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, primarily designed for outpatient mental health settings, can be adapted for specialized medical settings. They also discuss specific considerations and recommendations for its implementation (Magidson & Weisberg, 2014). Group CBT sessions effectively alleviate depression, anxiety, and stress, except for self-esteem. Therefore, further research could explore these findings by expanding the population to include different majors (Changklang & Ranteh, 2023). Additionally, the findings suggest that CBT for panic has implications for attachment representations (Zalaznik et al., 2019). The results indicate that CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety, hardiness, and self-efficacy. By managing anxiety, students’ levels of hardiness and self-efficacy can be increased, enabling them to better cope with the various challenges in their lives (Sahranavard et al., 2019). Furthermore, CBT techniques improve women’s optimism by focusing on communication and conflict resolution skills, leading to a positive attitude and life satisfaction (Dafei et al., 2021).

As a result, medical students must be educated on this subject to handle risky situations in their lives. Additionally, the research gap is centered on the insufficient evidence of psychological interventions to enhance the effectiveness of variables that impact the mental health of medical students. Hence, incorporating the variables mentioned above into this group is novel. The researcher determined that the use of CBT techniques could have a positive impact on the mental health of medical students by altering their attachment style within the research context mentioned above.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pre-test and post-test design with a control group. The statistical population included all medical students of Islamic Azad University from 2019 to 2020 in Mashhad City, Iran. A total of 30 medical students were selected via the purposeful sampling method. Then, through a random number table, the participants were divided into two experimental groups and one control group (n=15 in each group). The required sample size was calculated based on an effect size of 0.40, a power level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. The distribution of the attachment styles questionnaire was conducted to obtain a sample from students who answered the advertised call and were willing to participate in training on CBT techniques (Table 1).

Following the researcher receiving approval to conduct research from the Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, they submitted an application to the university's Medical Sciences Faculty. Subsequently, the attachment-style questionnaire was provided to the students who agreed to participate. A total of 30 individuals with insecure attachment styles were chosen for the study after the test. Next, the envelopes were unsealed, and the study participants were divided into two groups: One control group comprising 15 individuals and an experimental group with 15 individuals to analyze the data statistically. The faculty’s education officer coordinated the CBT course and its arrangement. The department’s education manager coordinated a cognitive-behavioral engineering education course and its location. For 5 weeks, each session was held for 70 min on Tuesdays and Thursdays. During the initial meeting of the training program, it was revealed that the course was developed in conjunction with the university faculty to investigate this matter.

Medical students were asked about their willingness to participate in these meetings. Medical students expressed their willingness and desire to participate in meetings with researchers. Before implementing the independent variable, the experimental and control groups were assessed using a pre-test administered by a 28-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) and life orientation test-revised (LOT-R) as compared to their previous attempts. The experimental group was given CBT training, which was an independent variable, while the control group did not receive any training. Following the training, the experimental and control groups were re-evaluated with a post-test to assess the influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

The experimental groups were involved with researchers and students bilaterally discussing issues, followed by students completing homework and engaging in activities. The researchers also inquired about the training’s potential effects on the students. The majority of students had a positive outlook on this training. The analysis of the data was carried out using the SPSS software along with descriptive statistics (Mean±SD), independent t-test, and inferential statistics for analysis covariance. The independent t-test was used to compare the pre-test scores of both the control and experimental groups. At the same time, the analysis of the covariance method was employed to determine the effects of training in CBT techniques on attachment styles, mental health, and optimism.

Attachment style questionnaire

Shaver and Hazen (1987) developed the attachment style questionnaire (ASQ), and it was adapted for use in Iran with students from Tehran University. This survey consists of 15 items, with five items devoted to secure, avoidant, and ambivalent attachment styles. The questionnaire uses a scoring system ranging from very low (score=1) to very high (score=5), and the scores for the attachment subscales are calculated by averaging the responses to the five questions for each subscale. Five items represent each attachment style (secure, avoidant, and ambivalent). Shaver and Hazen (1987) reported a reliability coefficient of 0.8 for the entire questionnaire and a Cronbach α of 0.78. They also found proper face and content and construct validity. Rahimian Boogar et al. (2007) obtained favorable reliability coefficients for the entire questionnaire and the ambivalent, avoidant, and secure styles, with Cronbach α values of 0.75, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.77, respectively. In the present study, the Cronbach α for the entire questionnaire was 0.71.

The 28-item general health questionnaire

To evaluate the effect of the psychosocial intervention on individuals’ well-being, we chose the GHQ-28 as the leading indicator of outcomes. Our decision was influenced by the results of a previous study and the tool’s effectiveness in measuring emotional stress (Goldberg & Williams, 1988). The GHQ-28 requires participants to rate their general health over the past few weeks using behavioral items based on a 4-point scale, indicating the frequency of their experiences as follows: “Not at all,” “no more than usual,” “rather more than usual,” and “much more than usual.” The scoring system used in this study was consistent with the original Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. The minimum score on the 28-item version is 0, while the maximum score is 84. Higher scores on the GHQ-28 indicate higher levels of distress (Goldberg & Hillier, 1979). Goldberg suggests that individuals with total scores of 23 or lower may be considered non-psychiatric, while subjects with scores higher than 24 may be classified as psychiatric. However, this threshold is not an absolute cutoff, and it is recommended that researchers establish their cutoff score based on the mean of their specific sample (Goldberg et al., 1998). The Iranian version of the GHQ-28 used in this study demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach α, split-half coefficients, and test re-test reliability coefficients of 0.9, 0.89, and 0.58, respectively (Malekooti et al., 2006). In our study, the Persian version had an internal consistency of 0.78.

The life orientation test-revised questionnaire

The researchers utilized the LOT-R to assess dispositional optimism (Scheier et al., 1994). This test consists of 10 items for participants to complete, with four of the items serving as filler to conceal the test’s true purpose to some extent. Three scoring elements are created with a positive sentiment, while the remaining three are crafted with a negative viewpoint. Each item is designed to prevent suggesting any particular reason for the anticipation, regardless of whether it originates from the person, the surroundings, or mere chance and external elements. Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each item based on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4), based on their present circumstances. The total score is determined by summing the raw scores from the optimism items and the inverted raw scores from the pessimism items. Scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater optimism and lower scores denoting lower optimism, commonly referred to as pessimism. To translate the LOT-R into Norwegian for this study, multiple forward and backward translation technique was employed. The internal consistency of the Persian version used in this research yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.76.

Results

Thirty medical students with a mean age of 31.39±5.37 years participated in this study. In terms of marital status, 20% were single and 70% married. The Mean±SD of the study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 As can be seen, the mean score of the secure domain at baseline were not significantly different in between intervention and control groups. The mean score of secure increased in the post-test phase in the intervention group compared to the control group. Also, the mean scores of avoidance and anxious domains were not significantly different between intervention and control groups at baseline. However, their scores in decreased in the post-test phase in the intervention group, compared to the control group. The scores in the control group did not change significantly.

The mean scores of distress variable (GHQ-28 score) were not significantly different between the two groups at baseline either. In the post-test phase, its score in the intervention group decreased compared to the control group, indicating that the mental health level increased in the intervention group. Finally, the mean score of dispositional optimism variable (LOT-R score) in the intervention group increased in the post-test phase compared to baseline, while no change in the scores of the control group were reported.

The results of the analysis of covariance are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, there was a significant difference in secure (P<0.001, η2=83.5%), avoidance (P<0.001, η2=76%), and anxious (P=0.001, η2 =34.6%) between the groups over time.

Moreover, there was a significant difference in distress (P<0.001, η2=80.7%) and dispositional optimism (P<0.001, η2=83.6%) between the groups over time. Table 4 presents the results for testing within-subjects effects. According to the results, since the P<0.05 in all study variables, it can be said that there was a significant difference between the two evaluation phases. Overall, it can be said that there was a significant difference in attachment style, mental health and optimism between the two intervention and control groups after removing the effect of the pre-test score. Therefore, the CBT caused significant changes in the levels of attachment style, mental health and optimism of medical students.

Discussion

This research assessed the efficacy of CBT in changing attachment style, enhancing mental well-being, and promoting optimism among medical university students. The findings of the study, as revealed by the multivariate analysis of covariance, indicated that the mean scores for attachment style were significantly different between the group of students who received the educational intervention and the control group. The utilization of CBT proved effective in modifying the attachment styles of the students. These results are in line with the findings of previous studies (Zalaznik et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2021; Anvari et al., 2022). Furthermore, insecure attachment predicted a negative longitudinal trajectory of eating disorder psychopathology, which indirectly contributed to increased levels of body uneasiness, as supported by mediation analyses. A study by Rossi et al. (2022) confirmed the well-established effectiveness of enhanced CBT in individuals with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

Training in CBT can impact how individuals perceive and express secure attachment in close relationships. This influence may arise due to the required energy and time commitment, which can consequently affect personal life and close relationships. These reciprocal influences align with previous understandings of attachment, which encompass both trait and state components. While attachment is considered moderately stable throughout one’s lifetime, the influence of various life circumstances on attachment has also been acknowledged (Darban et al., 2020).

Attachment theory examines how an individual’s dominant attachment style (secure or insecure) influences their ability to engage in safe and secure relationships and experience internal feelings of safety. By identifying an individual’s predominant attachment style, a person can assess how it might hinder their capacity to develop close, healthy relationships. This awareness allows them to make changes that promote greater closeness with others and cultivate a sense of security within themselves. Additionally, understanding the underlying reasons and purposes of a particular attachment style enables individuals to heal past emotional wounds and traumas (Fearon & Roisman, 2017).

Increasing attachment security yields positive effects on mental health and prosocial behavior (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Additionally, medical students with an anxious attachment style and limited access to emotion regulation strategies are impacted (Colonnello et al., 2022). Darban et al., (2020) found that attachment style predicts the quality of life among students and suggested that focusing on attachment style could serve as an intervention avenue to improve the well-being of medical students and establish a basis for long-term monitoring. To develop such interventions, the initial step is to examine the specific characteristics of healthcare students who may be experiencing psychological distress and identify potential protective factors in this population. Numerous protective factors have been identified that can enhance student well-being and mitigate the impacts of risk factors on student stress and psychological distress (Magidson & Weisberg, 2014).

In addition, the results indicated that CBT has the potential to enhance the mental well-being of medical students. Previous research findings are in line with the rephrased outcome, as stated by Magidson and Weisberg in 2014 and Sahranavard et al., 2019. Magidson & Weisberg, (2014) explained that specialty medical care utilizing CBT may directly target various psychological symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, aiming to improve overall functioning and quality of life and address cognitive and behavioral aspects relevant to managing a medical condition. Muller and Yardley (2011) conducted a comprehensive analysis and systematic review of the impact of telehealth-delivered CBT on medical populations, examining studies that assessed the effects of telehealth-delivered CBT on physical health outcomes. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that CBT yielded significant improvements in physical health outcomes, characterized by a small to medium effect size. It was particularly effective for patients with chronic conditions that were not immediately life-threatening. Furthermore, considering gender, the majority of participants who received CBT therapy were female (90.3%). This dominance aligns with the two-to-one female-to-male depression prevalence ratio (Changklang & Ranteh, 2023). When anxiety levels rise in students, their ability to manage situations, adapt, cope, and confront challenges diminishes over time, resulting in increased anxiety. Consequently, these students become less optimistic about their future and their problem-solving abilities. As a result, their academic performance and dormitory life may be disrupted. Conversely, by effectively managing anxiety and stress, students can enhance their problem-solving abilities and overall mental well-being. The findings of this study will aid students in improving their mental health through stress management techniques (Sahranavard et al., 2019).

The authors discuss how training in CBT introduces students to the concepts related to mental health. By utilizing these techniques, students learn to view the situations they encounter as problems that can be solved. The course covers various approaches to problem-solving, enabling participants to feel more in control of their environment and perceive difficult situations as less daunting. Consequently, individuals will be better equipped to effectively manage life events by acquiring the necessary coping skills, which can contribute to improved mental health. Moreover, one of the factors contributing to poor mental health is perceiving situations as threatening. By learning to identify and challenge spontaneous negative thoughts through this course, participants have the opportunity to reassess and modify these thoughts. Additionally, relaxation training assists individuals in achieving a state of relaxation by counteracting the symptoms of stress, thereby allowing them to have a greater ability to control their emotions.

The instruction of CBT can boost students’ optimism. This finding is in line with previous research conducted by Geschwind et al. (2019), Dafei et al., (2021), and Moloud et al., (2022). According to Moloud et al., optimism and self-esteem significantly increased among the CBT group following the intervention. However, these levels decreased in the long term due to the discontinuation of CBT sessions (Moloud et al., 2022). Optimism is considered an essential psychological resource and has consistently been associated with significant positive emotions and decreased negative psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression (Öcal et al., 2022; Chung et al., 2023). Optimistic individuals tend to reframe challenging situations as opportunities in disguise, leading to higher psychological and mental well-being during difficult times (Chu et al., 2022).

Managing mental stress can be achieved by practicing positive thinking and refraining from entertaining negative thoughts. Maintaining a positive mood enhances cognitive processing abilities, promotes altruism, and boosts self-esteem. Optimistic individuals tend to outperform pessimistic individuals in various areas of life, experiencing more success and enjoying greater social fulfillment. The central focus of CBT lies in understanding emotions, behavior, and cognitive representations of experiences, shaping the foundation of personality development, and addressing pathological cognitive patterns. The primary objective of cognitive-behavioral assessment is to establish a treatment plan and achieve regulation. It is worth mentioning that cognitive-behavioral techniques are typically learned through collective activities, potentially benefiting from the positive dynamics of a group and addressing general challenges associated with interpersonal relationships.

Conclusion

After analyzing the findings, it was determined that the CBT group displayed a significant improvement in their secure attachment style, mental health level, and optimism following the intervention. Consequently, it is vital to implement regular CBT sessions for medical students who have insecure attachments to address this issue effectively.

Study limitations

One limitation of this study is the researcher’s inability to control the motivation and cooperation of the subjects when answering the questionnaire, which may impact the study’s results. Additionally, demographic characteristics, including economic, social, and cultural status, are outside the researcher’s control and may influence the outcomes. Based on the findings from this study, future researchers are advised to conduct similar studies with larger sample sizes, explore different research domains, increase the number of meetings and meeting duration for more effective interventions, and examine group and individual differences that may impact the success of executive programs to cater to diverse backgrounds. To validate the intervention’s impact and its benefits on the control group, it is recommended to apply this method to the control group as well, assessing its effects on attachment style, health psychology, and optimism. Further trials should also be conducted to assess the stability of the intervention effect and confirm the training’s effectiveness.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article observed all the ethical guidelines. The individuals participating were informed of the purpose and methodology behind the research. The participants were assured that their data would be kept confidential, and they had the option to withdraw from the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Hajar Seifi, approved by the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, AllamehTabataba’i University.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who took part in this study.

References

- Anvari, M. S., Dua, V., Lima-Rosas, J., Hill, C. E., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2022). Facilitating exploration in psychodynamic psychotherapy: Therapist skills and client attachment style. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(3), 348–360. [DOI:10.1037/cou0000582] [PMID]

- Boni, R. A. D. S., Paiva, C. E., de Oliveira, M. A., Lucchetti, G., Fregnani, J. H. T. G., & Paiva, B. S. R. (2018). Burnout among medical students during the first years of undergraduate school: Prevalence and associated factors. PloS One, 13(3), e0191746. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0191746] [PMID]

- Calvo, V., D’Aquila, C., Rocco, D., &Carraro, E. (2020). Attachment and well-being: Mediatory roles of mindfulness, psychological inflexibility, and resilience. Current Psychology, 41, 2966–2979. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-020-00820-2]

- Changklang, P., & Ranteh, O. (2023). The effects of cognitive behavioural therapy on depression, anxiety, stress, and self-esteem in public health students, Thailand. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 12, 152. [PMID]

- Chu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., & Dai, H. (2022). Resilience mediates the influence of hope, optimism, social support, and stress on anxiety severity among Chinese patients with cervical spondylosis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 997541. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.997541] [PMID]

- Chung, M. L., Miller, J. L., Lee, S. J., Son, Y. J., Cha, G., & King, R. B. (2022). Linkage of optimism with depressive symptoms among the stroke survivor and caregiver dyads at 2 years post stroke: Dyadic mediation approach. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 38(4), 352-360. [DOI:10.1097/JCN.0000000000000920] [PMID]

- Colonnello, V., Fino, E., & Russo, P. M. (2022). Attachment anxiety and depressive symptoms in undergraduate medical students: The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. Perspectives on Medical Education, 11(4), 207-212 [DOI:10.1007/S40037-022-00713-Z] [PMID]

- Dafei, M., Jahanbazi, F., Nazari, F., Dehcheshmeh, F. S., & Dehghani, A. (2021). The effect of group cognitive-behavioral counseling on optimism and self-esteem of women during the 1st month of marriage that referring to marriage counseling center. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, 209. [PMID]

- Darban, F., Safarzai, E., Koohsari, E., & Kordi, M. (2020). Does attachment style predict quality of life in youth? A cross-sectional study in Iran. Health Psychology Research, 8(2), 8796. [DOI:10.4081/hpr.2020.8796] [PMID]

- Deng, Y., Cherian, J., Khan, N. U. N., Kumari, K., Sial, M. S., & Comite, U., et al. (2022). Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 869337. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337] [PMID]

- Esmat, S., Attia, A., &Elhabashi, E. (2021). Prevalence and predictors for depression among medical students during coronavirus disease-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(E), 1454-1460. [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2021.7390]

- Fearon, R. M. P., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment theory: Progress and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 131-136. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.002] [PMID]

- Geschwind, N., Arntz, A., Bannink, F., & Peeters, F. (2019). Positive cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression: A randomized order within-subject comparison with traditional cognitive behavior therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 119-130. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.005] [PMID]

- Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139-145. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291700021644] [PMID]

- Goldberg, D. P., & Williams, P. (1988). A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. NFER-NELSON. [Link]

- Goldberg, D. P., Oldehinkel, T., & Ormel, J. (1998). Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychological Medicine, 28(4), 915-921. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291798006874] [PMID]

- Haykal, K. A., Pereira, L., Power, A., & Fournier, K. (2022). Medical student wellness assessment beyond anxiety and depression: A scoping review. Plos One, 17(10), e0276894.; [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0276894] [PMID]

- Henrich, D., Glombiewski, J. A., &Scholten, S. (2023). Systematic review of training in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Summarizing effects, costs and techniques. Clinical Psychology Review, 101, 102266. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102266] [PMID]

- Hernandez, R., Vu, T. T., Kershaw, K. N., Boehm, J. K., Kubzansky, L. D., & Carnethon, M., et al. (2020). The association of optimism with sleep duration and quality: Findings from the Coronary Artery Risk and Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Behavioral Medicine, 46(2), 100-111. [DOI:10.1080/08964289.2019.1575179] [PMID]

- Krifa, I., van Zyl, L. E., Braham, A., Ben Nasr, S., & Shankland, R. (2022). Mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of optimism and emotional regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1413. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19031413] [PMID]

- Lange, J., Goerigk, S., Nowak, K., Rosner, R., & Erhardt, A. (2021). Attachment style change and working alliance in panic disorder patients treated with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 206–218. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000365] [PMID]

- Maduakor, E. C., Chukwuorji, J. C., Amanambu, P. N., & Ifeagwazi, C. M. (2022). Adult attachment and well-being in the medical education context: Attachment style is associated with psychological well-being through self-efficacy. In: L. Schutt, T. Guse, & M. P. Wissing (Eds.), Embracing well-being in diverse African Contexts: Research perspectives (pp. 297-317). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-85924-4_13]

- Magidson, J. F., & Weisberg, R. B. (2014). Implementing cognitive behavioral therapy in specialty medical settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(4), 367-371. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.08.003] [PMID]

- Malekooti, S. K., Mirabzadeh, A., Fathollahi, P., Salavati, M., Kahali, S., & AfkhamEbrahimi, A., et al. (2006). [Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GHQ-28 in Iranian elderly (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing, 1(1), 11-21. [Link]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychological Inquiry, 18(3), 139-156. [DOI:10.1080/10478400701512646]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006] [PMID]

- Mo, Q., Tan, C., Wang, X., Soondrum, T., & Zhang, J. (2022). Optimism and symptoms of anxiety and depression among Chinese women with breast cancer: The serial mediating effect of perceived social support and benefit finding. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 635. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-022-04261-y] [PMID]

- Moghadam, M., Rezaei, F., Ghaderi, E., &Rostamian, N. (2016). Relationship between attachment styles and happiness in medical students. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(3), 593–599. [DOI:10.4103/2249-4863.197314] [PMID]

- Moloud, R., Saeed, Y., Mahmonir, H., & Rasool, G. A. (2022). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy in major depressive disorder with focus on self-esteem and optimism: An interventional study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 299. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-022-03918-y] [PMID]

- Muller, I., & Yardley, L. (2011). Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(4), 177-184. [DOI:10.1258/jtt.2010.100709] [PMID]

- Öcal, E. E., Demirtaş, Z., Atalay, B. I., Önsüz, M. F., Işıklı, B., & Metintaş, S., et al. (2022). Relationship between mental disorders and optimism in a community-based sample of adults. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 52. [DOI:10.3390/bs12020052] [PMID]

- Rahimian Boogar, E., Nouri, A., Oreizy, H., Molavi, H., & Foroughi Mobarake, A. (2007). [Relationship between adult attachment styles with job satisfaction and job stress in nurses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 13(2), 148-157. [Link]

- Rossi, E., Cassioli, E., Martelli, M., Melani, G., Hazzard, V. M., & Crosby, R. D., et al. (2022). Attachment insecurity predicts worse outcome in patients with eating disorders treated with enhanced cognitive behavior therapy: A one‐year follow‐up study. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(8), 1054–1065. [DOI:10.1002/eat.23762] [PMID]

- Rotenstein, L. S., Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J., & Guille, C., et al. (2016). Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(21), 2214–2236. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.17324] [PMID]

- Sahranavard, S., Esmaeili, A., Salehiniya, H., & Behdani, S. (2019). The effectiveness of group training of cognitive behavioral therapy-based stress management on anxiety, hardiness and self-efficacy in female medical students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(1), 49. [DOI: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_327_18"10.4103/jehp.jehp_327_18] [PMID]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063] [PMID]

- Shaver, P., & Hazan, C. (1987). Being lonely, falling in love. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 2(2), 105. [Link]

- Singh, I., & Jha, A. (2013). Anxiety, optimism and academic achievement among students of private medical and engineering colleges: A comparative study. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 3(1), 222-233. [DOI:10.5539/jedp.v3n1p222]

- Vitorino, L. M., Cazerta, M. F., Corrêa, N. R., Foresto, E. D. P., Oliveira, M. A. F., & Lucchetti, G. (2021). The influence of religiosity and spirituality on the happiness, optimism, and pessimism of Brazilian medical students. Health Education & Behavior, 49(5), 884-893. [DOI:10.1177/10901981211057535] [PMID]

- Zalaznik, D., Weiss, M., & Huppert, J. D. (2019). Improvement in adult anxious and avoidant attachment during cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 29(3), 337-353. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2017.1365183] [PMID]

- Zilcha-Mano, S. (2019). Major developments in methods addressing for whom psychotherapy may work and why. Psychotherapy Research, 29(6), 693-708. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2018.1429691] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Rehabilitation

Received: 2023/09/27 | Accepted: 2023/12/18 | Published: 2024/04/25

Received: 2023/09/27 | Accepted: 2023/12/18 | Published: 2024/04/25

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |