Volume 12, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

PCP 2024, 12(4): 371-382 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadrzadeh F, Borjali A, Rafezi Z. Self-compassion and Social Anxiety Symptoms: Fear of Negative Evaluation and Shame as Mediators. PCP 2024; 12 (4) :371-382

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-940-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-940-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. ,borjali@atu.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 745 kb]

(2273 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3093 Views)

Full-Text: (1791 Views)

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), with a global prevalence rate of 36% in young people (Jefferies & Ungar, 2020), is among the most common anxiety disorders (Bornstein, 2018). Social anxiety involves an excessive concern about potential judgment in social situations and avoidance of them (APA, 2022). Typically, SAD has an onset in early adolescence (Bornstein, 2018), follows a chronic course if untreated (APA, 2022), and shows a high association with other mental health conditions (Koyuncu et al., 2019). It significantly impacts various aspects of life, including occupational, educational, and social functioning (Aderka et al., 2012). Given its pervasive negative consequences, understanding both maintaining and potential protective factors against social anxiety is crucial.

Fear of negative evaluation (FNE) is one of these maintaining factors suggested by cognitive behavioral models (Leigh & Clark, 2018). FNE refers to the concern about being judged or disapproved by others during or in anticipation of social interactions (Kizilcik et al., 2016). For individuals with SAD, this fear results in the employment of avoidance behaviors to minimize the possibility of negative judgment. However, these strategies, while aimed at reducing immediate anxiety, can inadvertently result in the maintenance of the disorder over time (Heimberg et al., 2014).

Longitudinal research supports the role of FNE as a risk factor for increased SAD symptoms (Fredrick & Luebbe, 2024; Zhang et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2020). Furthermore, Tedadi et al. (2022) showed that FNE is a specific vulnerability factor for SAD. Additionally, Swee et al. (2021) stated that individuals concerned about being evaluated in social interactions may be more prone to experience shame as well. Shame, in turn, may be another factor contributing to the persistence of SAD.

Shame is defined as a self-conscious emotion triggered by negative self-evaluation (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). It consists of cognitive (such as believing oneself to be inadequate), behavioral (such as avoiding others), and physiological (such as feeling discomfort in the stomach) patterns (Swee et al., 2021). Frequent, intense experiences of shame become internalized, leading to a global negative self-view and feeling of being flawed (Harper, 2011). Studies demonstrate that higher proneness to experience shame, also known as trait shame (Sedighimornani, 2018), is linked to the development and perpetuation of various psychopathologies (Azevedo et al., 2022; Cândea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2018a), including SAD (Swee et al., 2021).

In this regard, research suggests that more pronounced feelings of shame are reported by individuals with SAD compared to those without the disorder. Additionally, shame contributes to the persistence and exacerbation of SAD symptoms (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024). Moreover, trait shame is associated with more interpersonal problems and elevated symptoms of SAD (Schuster et al., 2021). Likewise, individuals with elevated social anxiety experience more shame proneness and feelings of inadequacy in their daily lives (Lazarus & Shahar, 2018). Additionally, individuals with high levels of shame struggle to show compassion towards themselves, suggesting that a likely helpful approach to counteract shame is self-compassion (Gilbert & Procter, 2006).

Self-compassion was introduced by (Neff, 2003a) based on the Buddhist perspective. It reflects how individuals respond to themselves during life challenges, sufferings, failures, and feelings of inadequacy (Neff, 2003a) and include recognizing internal suffering while being present and open to it (Germer & Neff, 2019). According to Neff, self-compassion comprises three main facets, self-kindness, involving being supportive and empathetic toward one’s suffering rather than adopting a critical and self-judgmental attitude, common humanity, which involves recognizing the universality of human suffering, failures, and feelings of inadequacy as part of the shared human experience, rather than feeling isolated by them, and mindfulness, which entails staying aware and open to the present experience, without ignoring, avoiding or overidentifying with difficult thoughts and emotions.

Research has identified self-compassion as a significant construct in mental well-being (Neff et al., 2018). Consistent with research suggesting the protective benefits of self-compassion against various psychopathologies (Lee et al., 2021; Athanasakou et al., 2020), some research has shown its effectiveness in alleviating social anxiety symptoms (Slivjak et al., 2022; Blackie & Kocovski, 2019). Individuals with SAD typically exhibit negative self-view and engage in harsh self-criticism (Iancu et al., 2015). Self-compassionate perspective represents the opposite stance to these negative cognitions, emphasizing acceptance and kindness toward oneself when facing these challenges (Neff, 2023). This perspective indicates that self-compassion may offer benefits to individuals dealing with social anxiety. However, the mechanisms by which it may alleviate social anxiety need further research. Self-compassion, in altering an individual’s relationship with themselves, likely helps reduce SAD directly and indirectly by lowering FNE and shame, two factors perpetuating the disorder.

Supporting evidence indicates that individuals who adopt a compassionate attitude toward themselves tend to experience diminished levels of evaluation anxiety (Huang & Wang, 2024; Long & Neff, 2018). Furthermore, those who exhibit enhanced self-compassion may be better equipped to manage socio-evaluative stressors, experiencing diminished perceived stress and also reduced feelings of shame (Ewert et al., 2018). Additionally, on the relationship between self-compassion and shame, Cȃndea and Szentágotai-Tătar (2018b) demonstrated that self-compassion training effectively alleviates feelings of shame and reduces symptoms of social anxiety. Similarly, Ross et al. (2019), showed that increased self-compassion, through the reduction of shame, can be indirectly associated with a decrease in depression symptoms, a process that can also be true for social anxiety.

It is worth noting that studies investigating the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in Iran are limited. Given that cultural factors can impact self-compassion (Montero-Marin et al., 2018), it is essential to study this relationship within the context of Iranian culture. Additionally, one group particularly susceptible to performance dysfunction due to social anxiety is students. This is because educational environments involve social evaluation, and those with high FNE may be less inclined to engage in class activities (Long & Neff, 2018) and may even experience a decline in educational functioning (Vilaplana-Pérez et al., 2021). This highlights the necessity of addressing social anxiety among students.

Therefore, this research was conducted to explore the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in a university student population, with a specific focus on exploring the potential mediating roles of FNE and shame.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive-correlational research design was adopted by employing structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess the structural relationships between variables. The statistical population included undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students enrolled in public universities across Tehran City in 2021-2022. The inclusion criteria included willingness to participate with informed consent, and being a current student. The exclusion criteria included completing the questionnaires in less than 6 minutes, which was considered insufficient time for accurate completion.

According to Kline (2023), a minimum sample size of 10-20 times the estimated parameters is recommended for SEM studies. Therefore, based on the 14 parameters estimated in the present study, the minimum sample size can be considered 140. To enhance external validity, 263 participants were selected via a convenience sampling method. A total of 21 participants who completed the questionnaires in a short period were excluded from further consideration, leading to a final sample of 242 for analysis.

Data were collected online by sharing questionnaires in student social media groups on Telegram and WhatsApp. To comply with ethical considerations, the questionnaire’s description stated that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were assured that their personal information would be kept confidential and informed of their option to withdraw from the research at any point.

Instruments

Social phobia inventory (SPIN) (Connor et al., 2000)

This 17-item self-report measure was used to assess social anxiety symptoms. Fear, avoidance behaviors, and physiological symptoms are the three subscales assessed by this tool. A 5-point Likert scale is used to rate the items (0=“not at all”, 4=“extremely”). The total score ranges between 0 to 68. In previous research, Cronbach’s α was reported from 0.82 to 0.94 among social phobia subjects, and from 0.82 to 0.9 in control groups (Connor et al., 2000). In Iran, in a study conducted by Hassanvand Amouzadeh (2016) among students experiencing social anxiety, Cronbach’s α was reported as 0.97, Spearman-Brown as 0.97, and test re-test as 0.82, and the validity of the scale was favorable. In the present research, the overall scale of Cronbach’s α was 0.953. Regarding subscales, 0.876 was obtained for the fear component, 0.903 for avoidance, and 0.843 for physiological symptoms.

Brief FNE scale (BFNE) (Leary, 1983)

This 12-item questionnaire was employed to measure FNE. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“not at all”, 5=“completely”). After reversing items 2, 4, 7, and 10, the total score is determined by summing all the items, ranging from 12 to 60. According to Leary (1983), the original scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.9. In subsequent research on a non-clinical sample of Iranian students, Cronbach’s α was 0.84 for the overall scale, 0.87 for the direct items, and 0.47 for the reverse items (Shokri et al., 2008). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.871

Test of self-conscious affect (TOSCA-3) (Tangney et al., 2000)

The inclination toward experiencing shame was assessed by this tool. It consists of 16 self-report scenario-based items that assess five self-conscious emotions. For the current research, only the shame-proneness subscale was utilized, focusing on measuring the tendency for negative self-evaluation. The likelihood of each reaction to the described scenario is rated using a 5-point Likert scale (1=“not likely”, 5=“very likely”). All responses are scored directly. The minimum score on the shame subscale is 16, and the maximum is 80. In a study involving three groups of college students, Tangney & Dearing, (2002) reported Cronbach’s α for the shame subscale, ranging from 0.76 to 0.88. In the research conducted by Roshan Chesli et al. (2007), Cronbach’s α of shame proneness was 0.78. The present study yielded a Cronbach’s α of 0.868.

Self-compassion scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003b)

Trait self-compassion was assessed with this 26-item self-report questionnaire. Responses are evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“rarely”, 5=“always”). This tool assesses three bipolar aspects of self-compassion and contains six subscales, self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Items with negative wording are reverse-scored, and the total score is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The minimum score of this measure is 26, and the maximum is 130. Neff, (2003b) reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.92 for the total score and alphas ranging from 0.75 to 0.81 for the subscales. In the research conducted by Khosravi et al. (2013) Cronbach's α was 0.76 for the total score and ranged from 0.79 to 0.85 for the subscales. The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.932.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 22 for descriptive statistics and AMOS software, version 22 to perform SEM.

Results

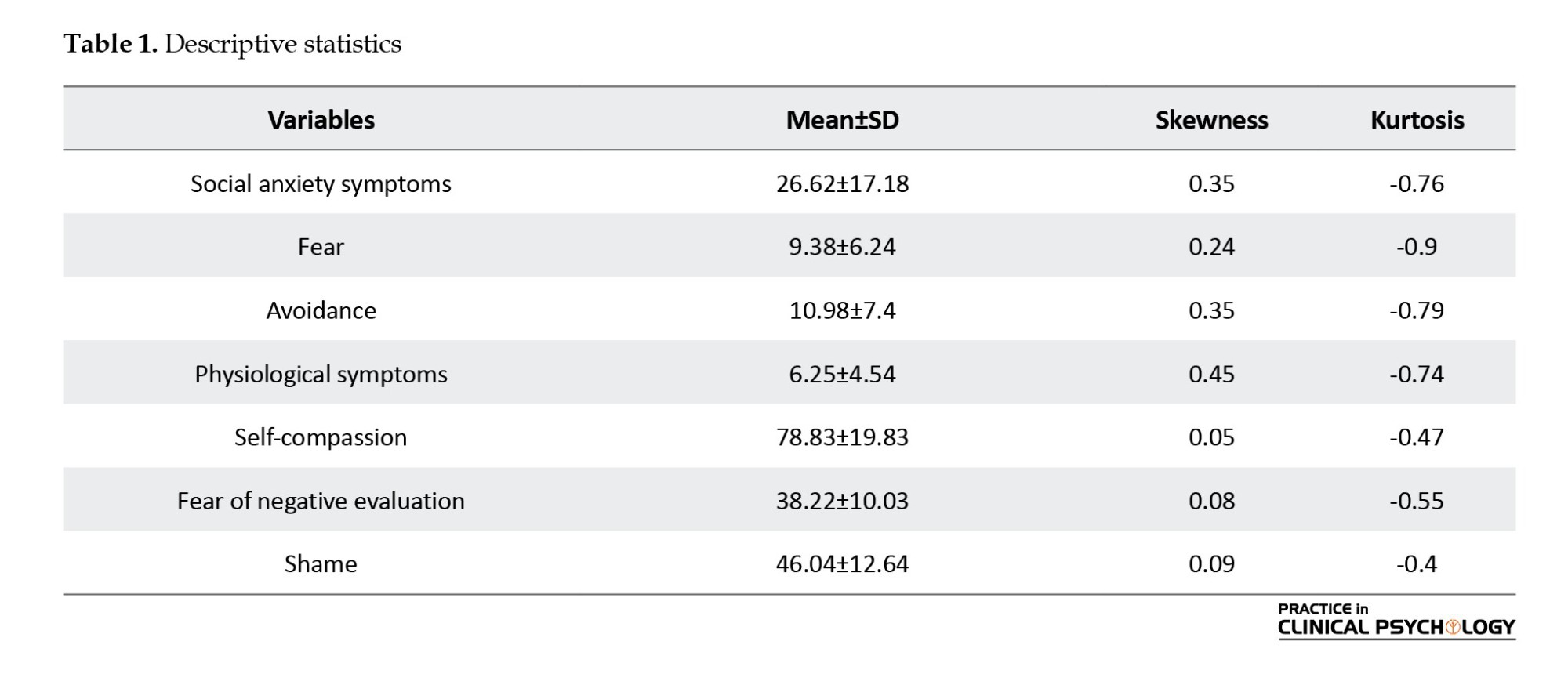

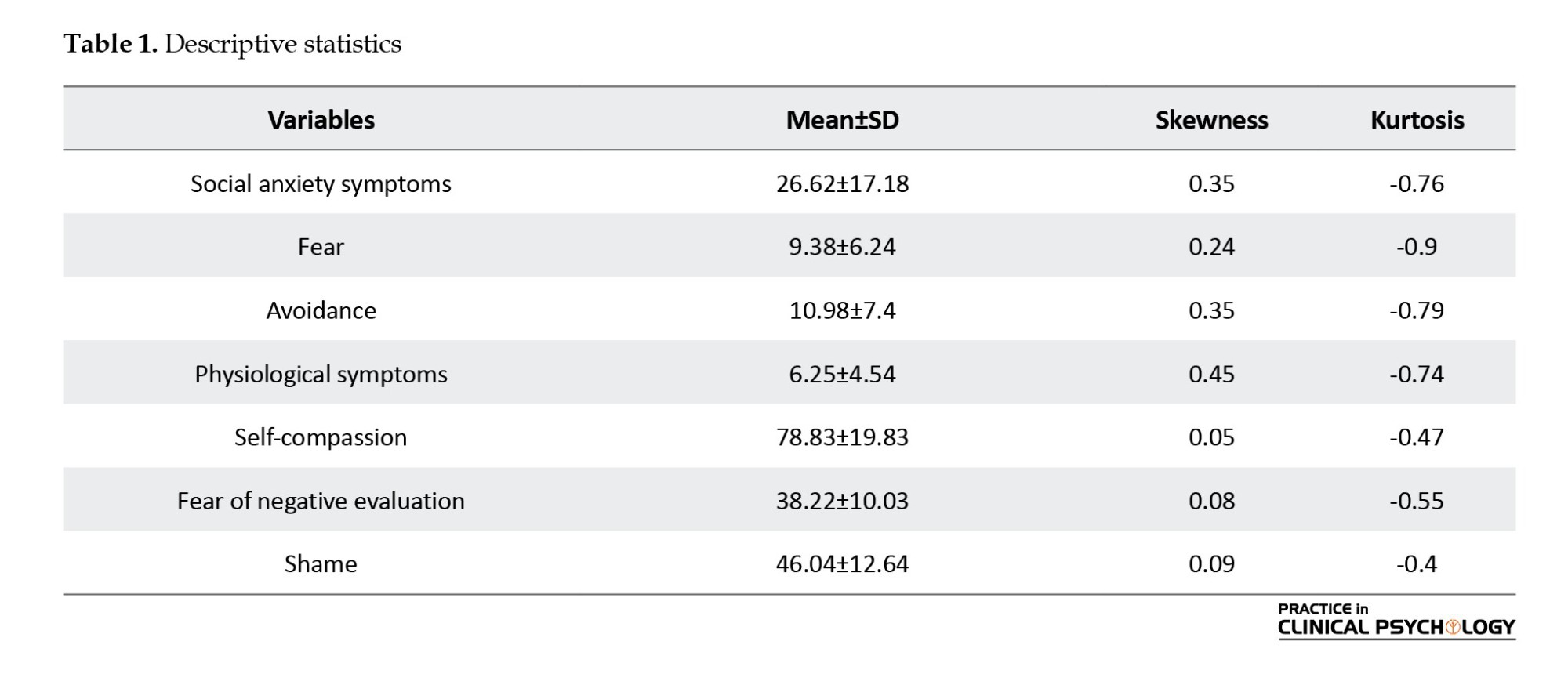

The present study was conducted on 242 individuals, including 156 women (65.5%) and 86 men (35.5%). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years, with a Mean±SD of 25.07±5.88. Regarding marital status, 206 participants (85.1%) were single, and 26(14.9%) were married. Also, in terms of educational level, 130 participants (53.7%) were undergraduate students, 98(40.5%) were pursuing a master’s degree, and 14(5.8%) were at the doctoral level. Table 1 presents the descriptive indices of the research variables. As shown in Table 1, the values for kurtosis and skewness of all variables were in the acceptable range (±3), suggesting a normal data distribution.

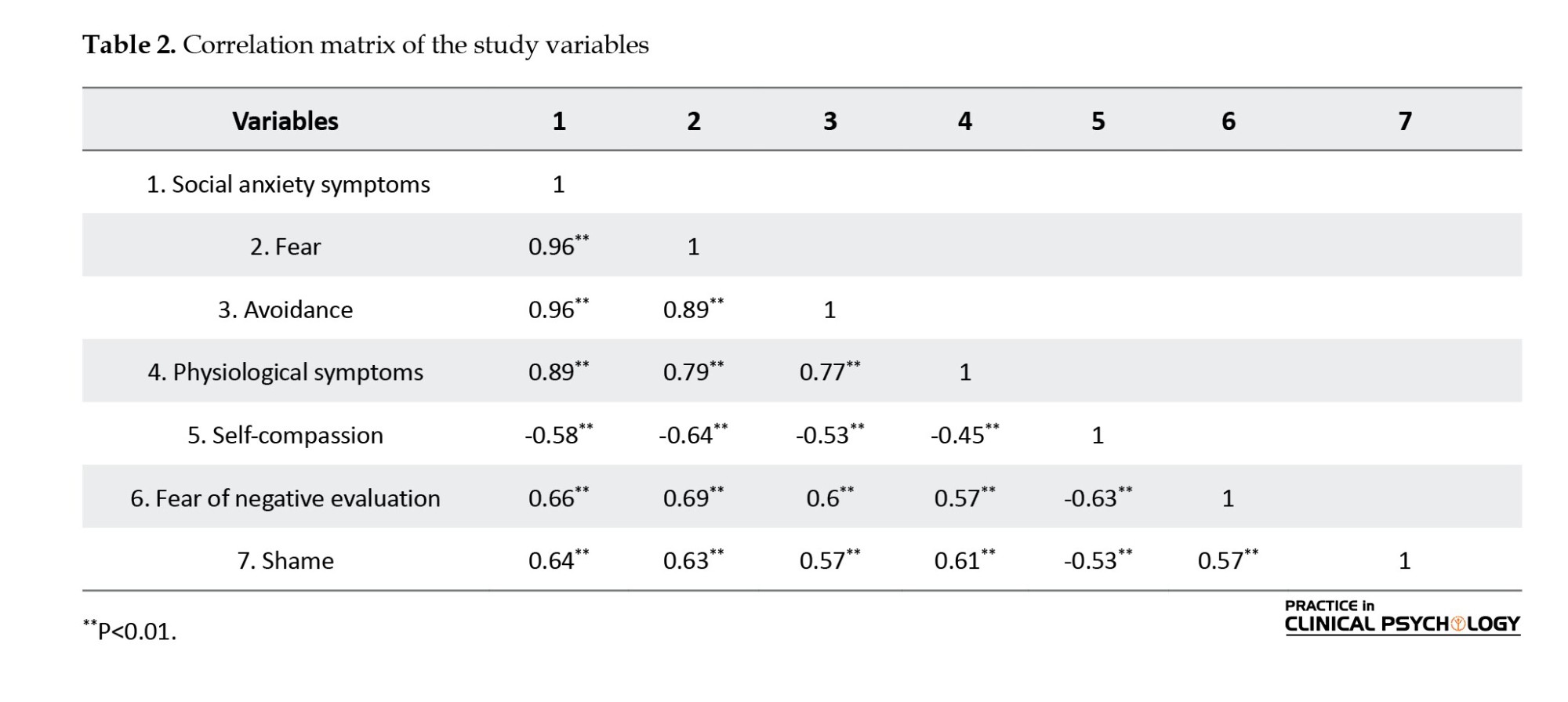

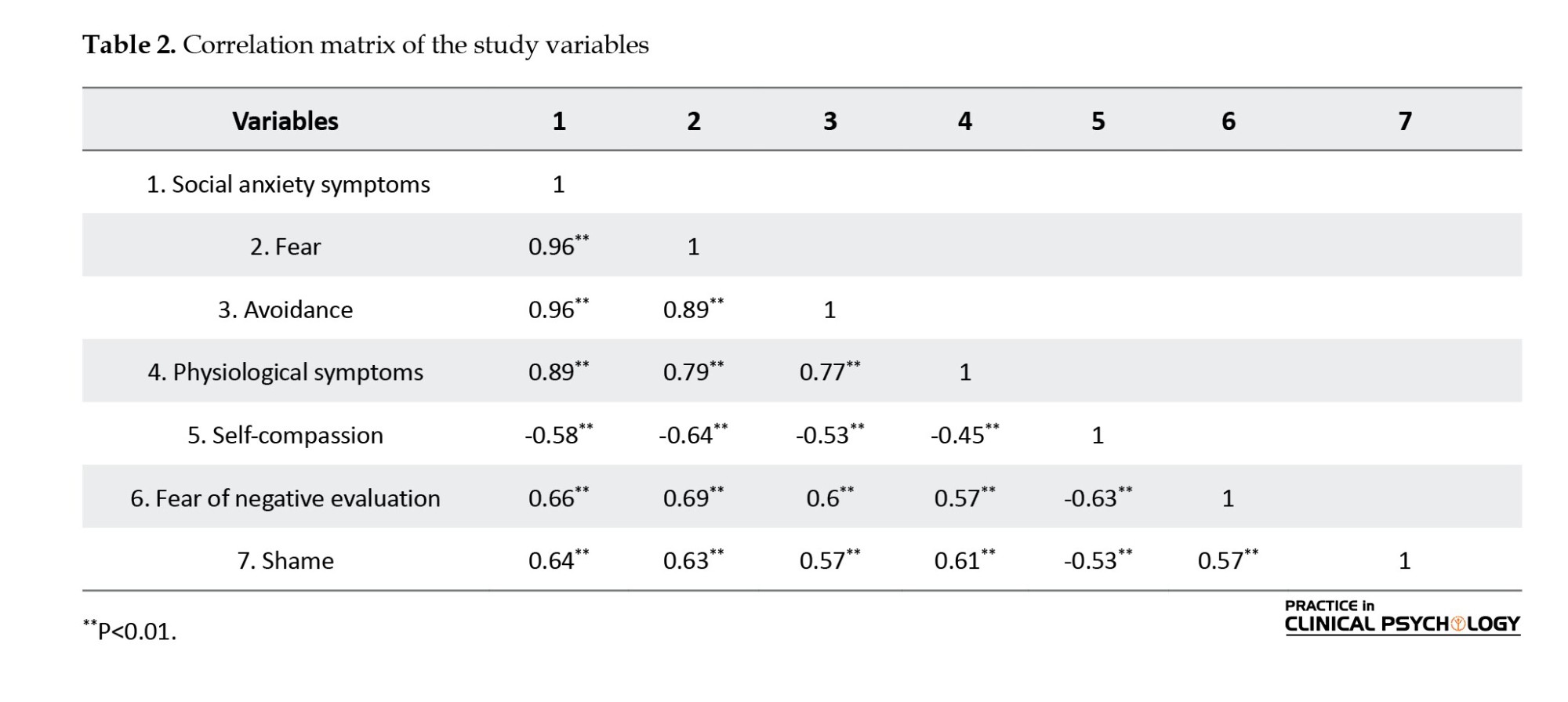

Before examining the structural model, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between each of the variables. Table 2 presents the correlation matrix. Significant relationships were observed among all the variables (P<0.01), justifying the subsequent application of SEM to further explore the underlying structural relationships.

Before model analysis, assumptions of SEM were assessed. Univariate normality of variables was checked using kurtosis and skewness statistics. As shown in Table 1, all variables exhibited kurtosis and skewness values within the range of -3 to +3, suggesting adherence to univariate normality. Multivariate normality was evaluated using Mardia’s normalized multivariate kurtosis value, calculated as 3.531 in the present study. According to Bentler (2005), values above 5 can be considered as a departure from multivariate normality. Therefore, multivariate normality is also established.

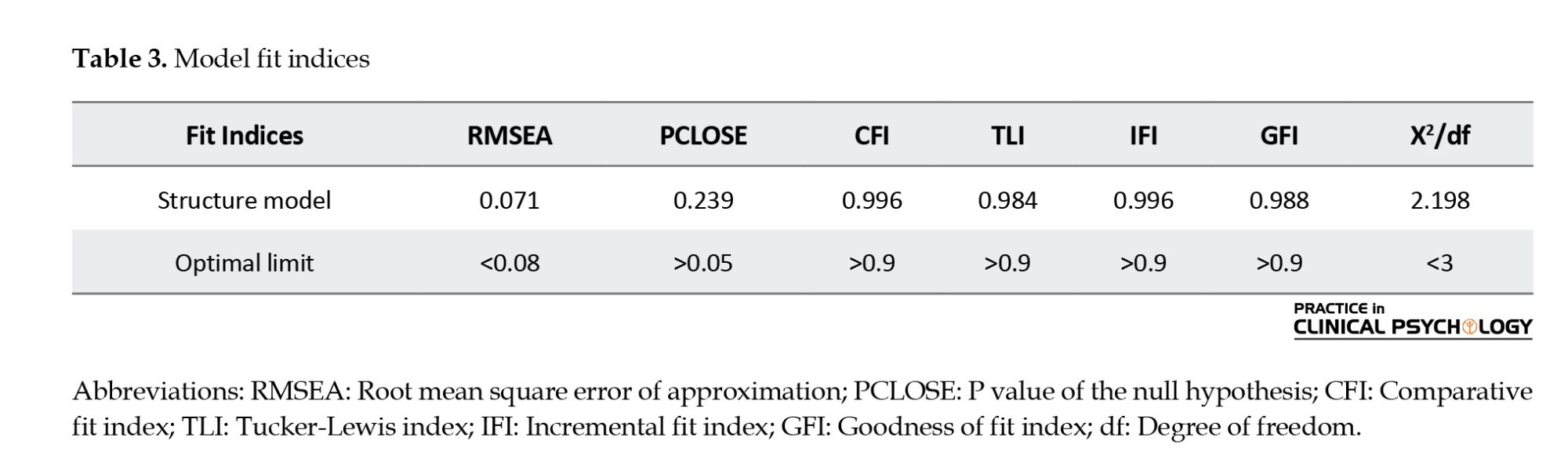

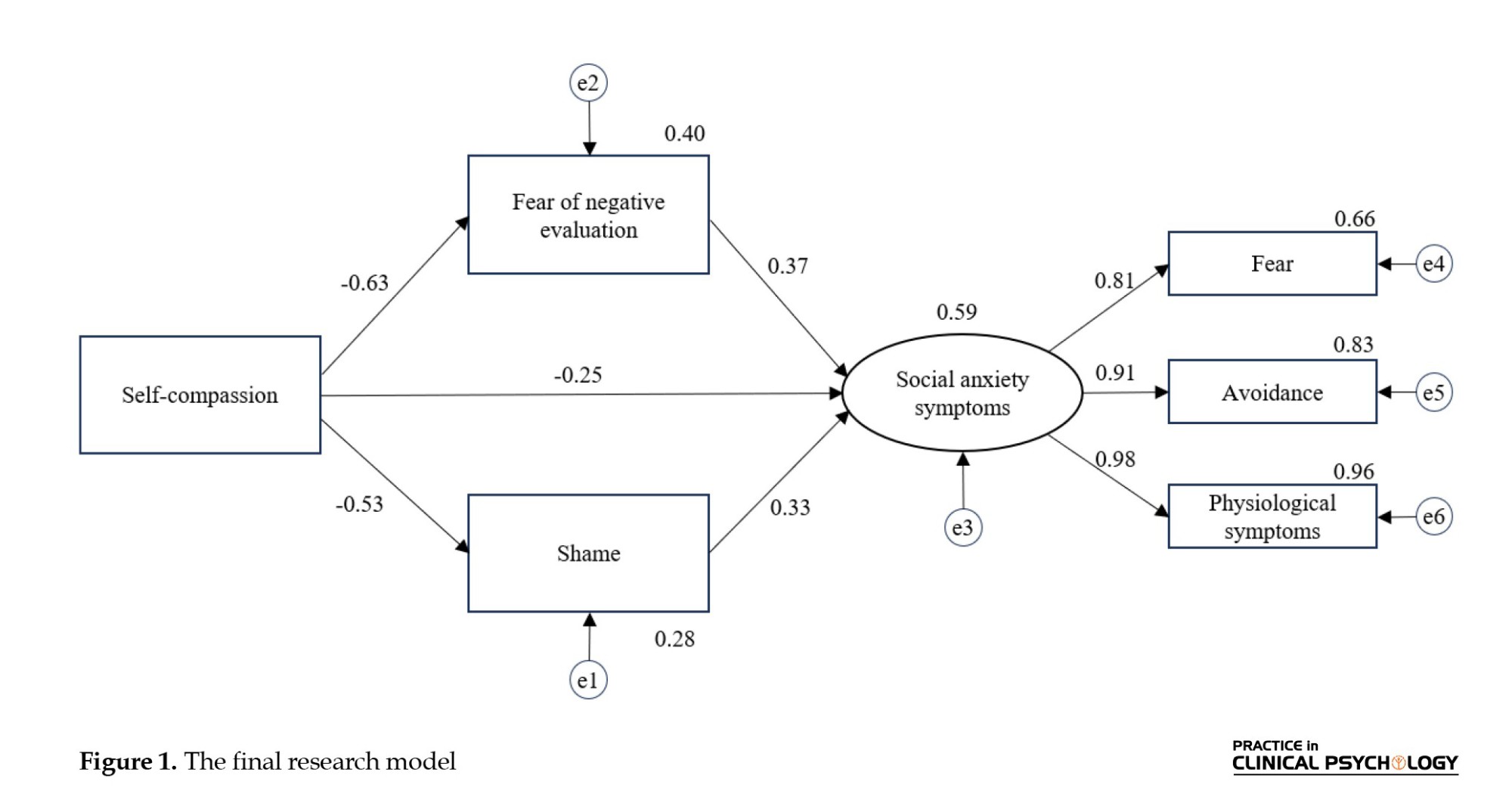

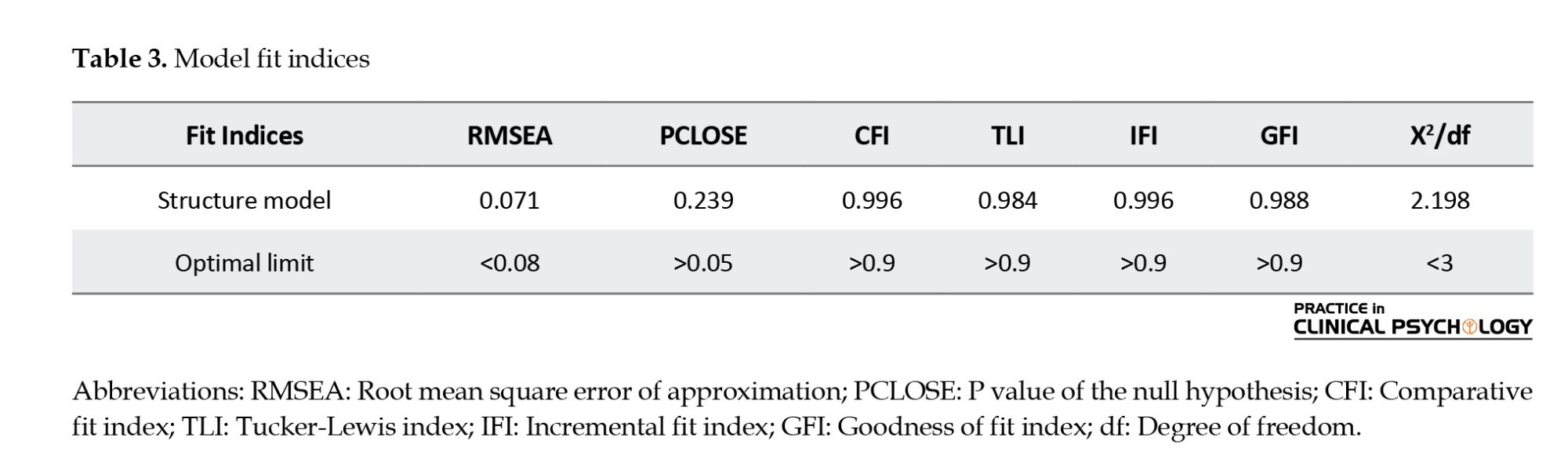

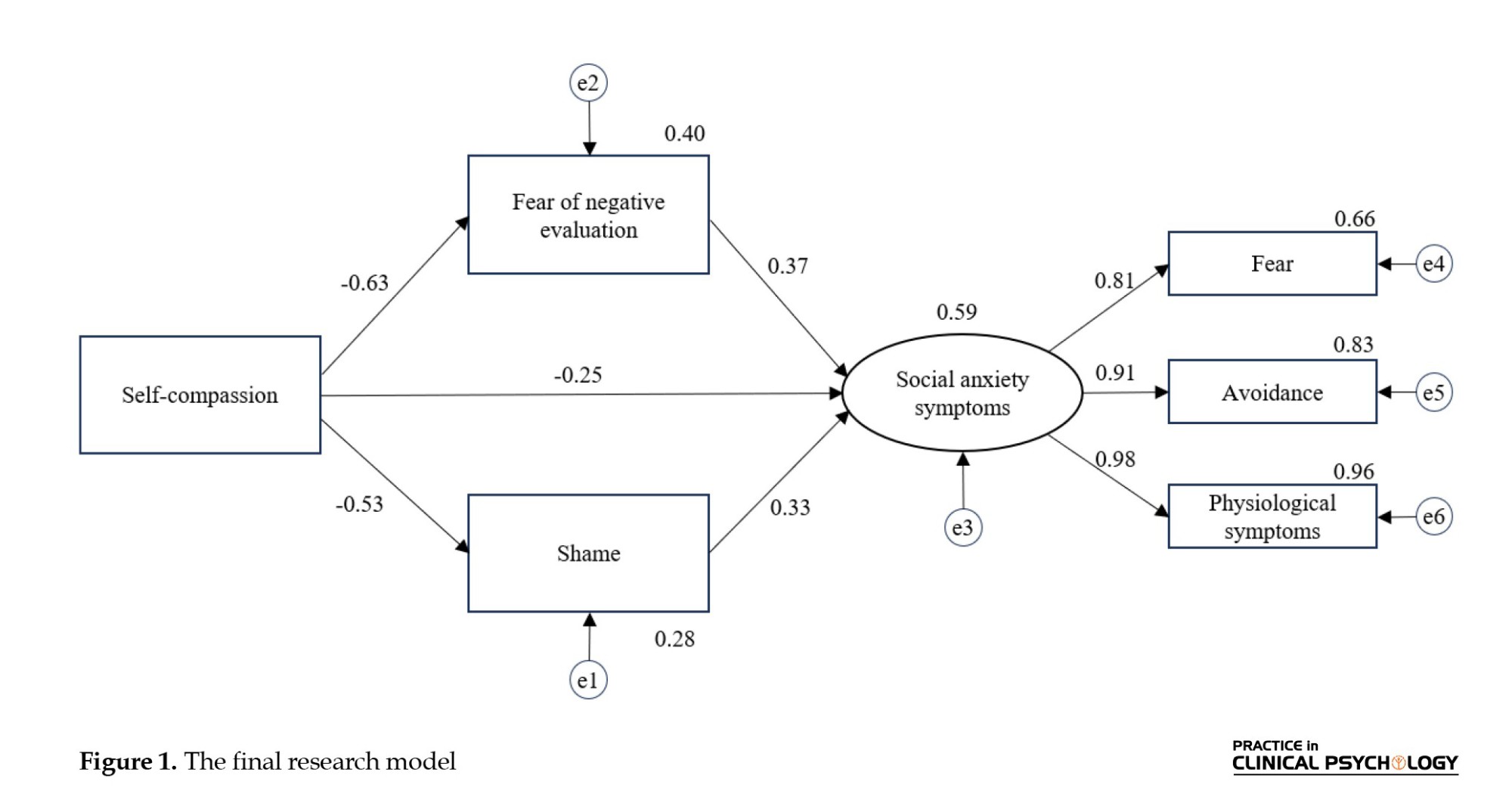

Table 3 presents the fit indices, and Figure 1 shows the final model. All fit indices in Table 3 fall within acceptable ranges, indicating a good model fit. The final model accounted for 59% of the variance in social anxiety symptoms.

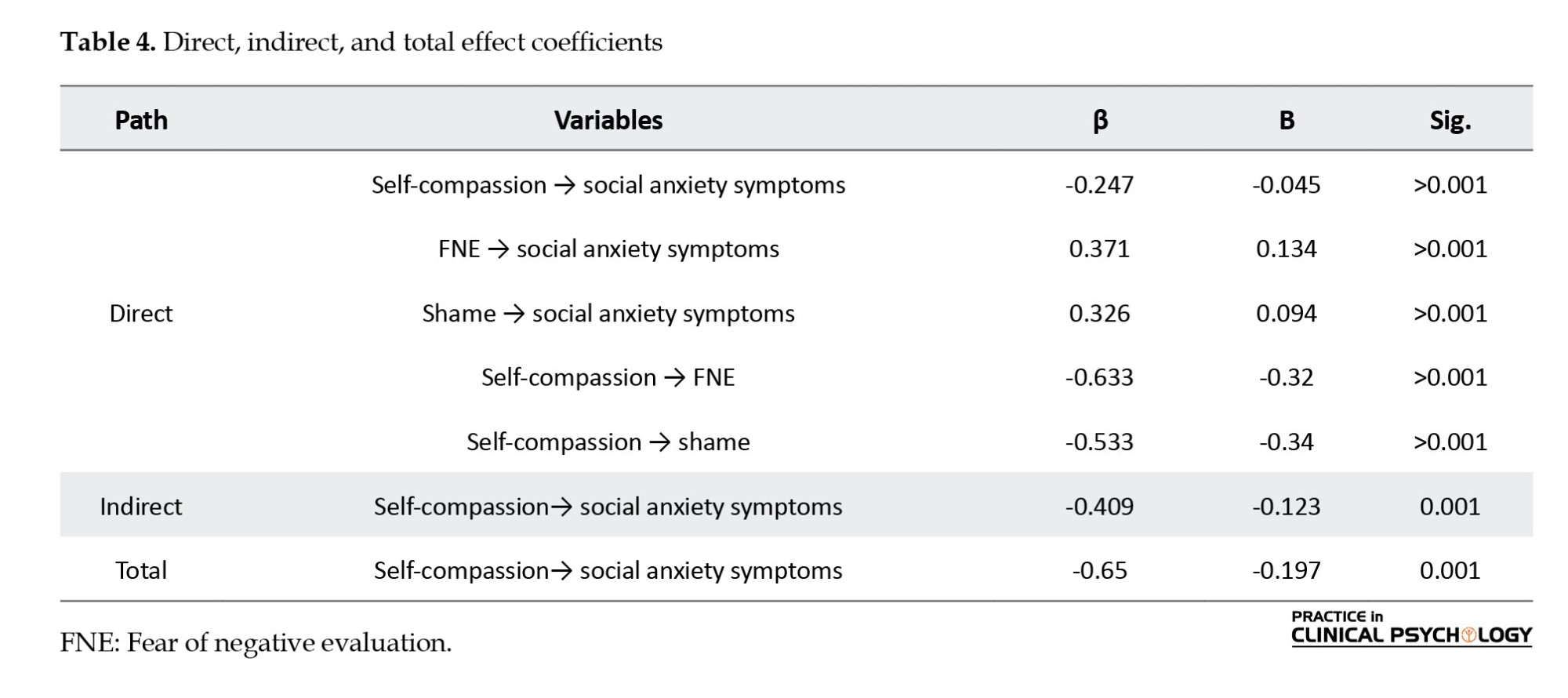

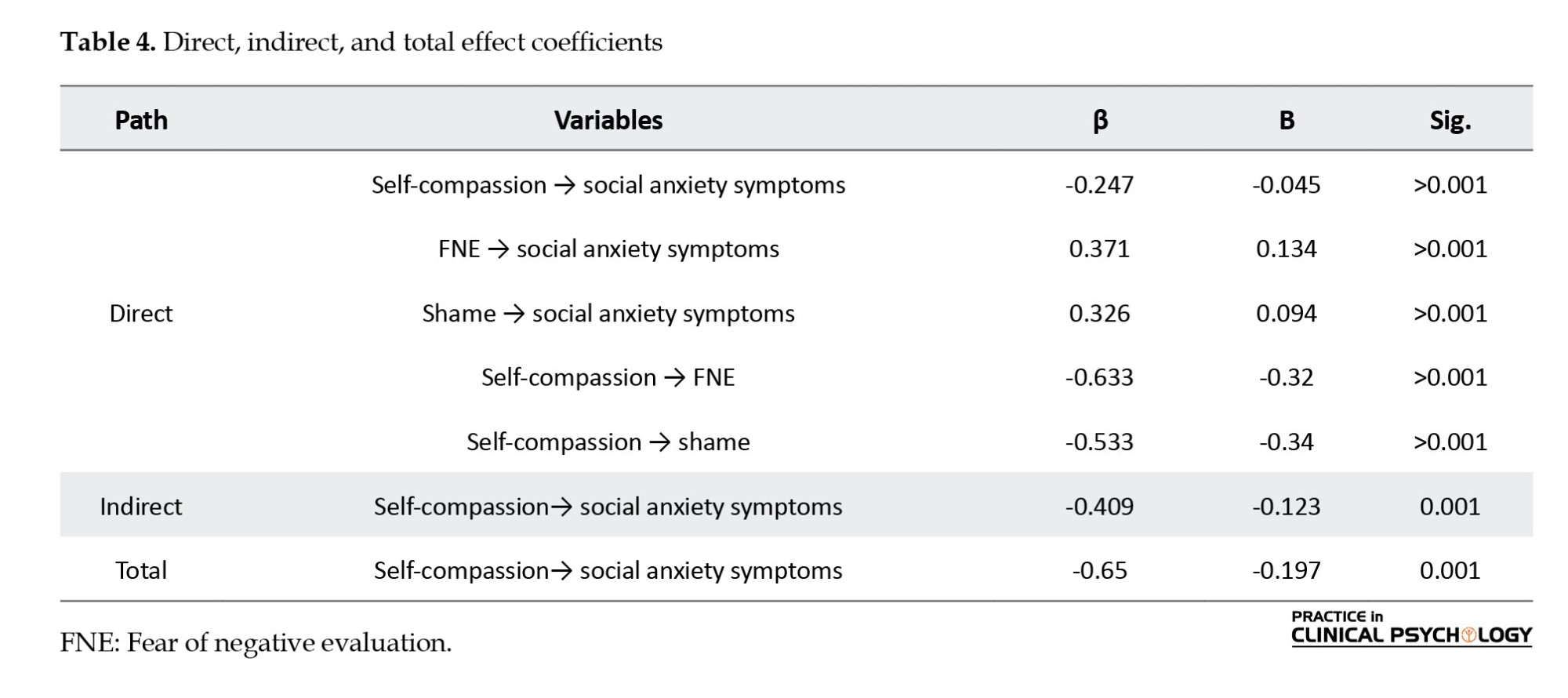

Table 4 presents the results regarding the direct coefficients between the variables. The analysis revealed that he standardized path coefficient of self-compassion to social anxiety, FNE, and shame were -0.247, -0.633, and -0.533, respectively, and for FNE to social anxiety and shame to social anxiety were 0.371 and 0.326, respectively (P<0.01). Furthermore, the indirect effect of self-compassion on social anxiety symptoms, mediated by FNE and shame, was assessed using the Bootstrap test. The standardized coefficient value obtained was -0.409 (P<0.01), as outlined in Table 4.

Discussion

This study was conducted to explore the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms, with a focus on the mediating roles of FNE and shame. The analysis revealed a well-fitting final model.

The results regarding direct effects indicated a significant direct negative effect of self-compassion on social anxiety symptoms. This result is consistent with the previous research by McBride et al. (2022) and Holas et al. (2021) The contrasting characteristics of self-compassion and SAD can be used to elucidate this result. Social anxiety involves self-criticism, avoidance, and catastrophizing (Hofmann, 2007; Heimberg et al., 2014). Conversely, self-compassion promotes acceptance of the self, self-kindness, a balanced self-view, and acknowledging flaws as part of being human. The theory of emotion regulation systems proposed by Gilbert (2014) can also provide another explanation for this observed relationship. Based on this model, individuals with SAD perceive social interactions as inherently competitive and potentially threatening, which can be associated with the risk of rejection. In this case, over-estimating environmental threats and high self-criticism lead to constant activation of the sympathetic nervous system (Gilbert, 2014). Therefore, the heightened activity of the threat system in these individuals tends to dominate over the activity of the safety system. Self-compassion, by establishing an accepting relationship with oneself and providing self-soothing capacity, can be linked to decreased activation of the sympathetic nervous system, accompanied by a concurrent increase in parasympathetic nervous system activity (Kirschner et al., 2019). The shift in the balance between these two systems can contribute to decreased threat responses and reduced anxiety.

Moreover, the results indicated a direct effect of FNE on social anxiety. This study is consistent with studies by Fredrick & Luebbe (2024), Zhang et al., (2023), and Johnson et al. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral perspectives suggest that shaped by past experiences, individuals with SAD tend to form key assumptions that lead them to set unrealistically high standards for social performance, maintain rigid negative self-perceptions, such as believing they are unlikeable or incompetent, and make negative predictions about the consequences of social behaviors, like expecting to be rejected if they make a mistake (Clark, 2005). These assumptions may lead individuals to overestimate the demands of social interactions while underestimating their social abilities to meet these expectations. As a result, they perceive social situations as overly threatening and overestimate the potential cost of adverse social events. Consequently, they experience excessive fear of being negatively evaluated, leading to heightened anxiety in social settings (Heimberg et al., 2014; Clark, 2005).

The study results also demonstrated a direct effect of shame on social anxiety. This result is consistent with the research conducted by Schuster et al. (2021) and Makadi and Koszycki. (2020). Germer & Neff (2019) posit that shame underlies many difficult emotions and makes them persistent. Anxiety is one such emotion that can arise from shame. Shame stems from the fundamental human need to belong and be accepted by others. It emerges when individuals perceive themselves as so flawed that they cannot be accepted. Negative self-evaluations related to shame, likely rooted in adverse early life experiences (Swee et al., 2021), may underlie the negative self-referential cognitions of social anxiety (Moscovitch, 2009). These negative self-perceptions can further lead to feelings of inferiority, social avoidance behaviors, and a fear of losing social status, all of which are characteristics of social anxiety (Gilbert & Miles, 2000).

Furthermore, the results revealed that self-compassion has a direct negative effect on FNE. This result is consistent with previous studies by Huang & Wang, (2024), and Long and Neff (2018). FNE reflects an excessive concern with one’s public image or social self (Dickerson et al., 2004). Individuals with high FNE often exhibit a deficit in self-affirmation, looking for signs of devaluation and rejection and demonstrating excessive reliance on external evaluative feedback (Heimberg et al., 2014). However, self-compassion can provide a stable source of self-worth and belonging as a human being, irrespective of external judgments (Long & Neff, 2018). As demonstrated by Leary et al., (2007) individuals with greater self-compassion are less influenced by external evaluations and tend to maintain a more realistic view of themselves.

Additionally, the study results revealed that self-compassion has a direct negative effect on shame, replicating previous studies by Etemadi Shamsababdi and Dehshiri (2024) and Ross et al. (2019). Germer & Neff (2019) describe self-compassion as “an antidote to shame”, highlighting the contrasting qualities of the two concepts. Shame is characterized by self-criticism, isolation, and a tendency to view oneself as flawed. In contrast, self-compassion involves accepting oneself as a human being and a sense of belonging to the human race. It also helps individuals understand events as a result of various factors rather than solely personal failings. As Inwood and Ferrari (2018) demonstrated, self-compassion may be an effective strategy as a means of regulating emotions and mitigating feelings of shame.

Investigating indirect effects demonstrated that FNE mediates the link between self-compassion and social anxiety. It is consistent with the results of studies by Liu et al. (2020) and Gill et al. (2018) on adolescents. As mentioned, socially anxious individuals experience heightened FNE due to feelings of inadequacy, perceived inability to meet social standards, and catastrophizing negative evaluation (Clark, 2005). Self-compassion helps individuals accept their imperfections and view social evaluations as less threatening (Breines & Chen, 2012; Ewert et al., 2018), leading to lower FNE and reduced social anxiety. Furthermore, when individuals feel less vulnerable to external judgment, they are less likely to hide their true selves (Long & Neff, 2018). This is crucial because FNE often leads to avoidance behaviors, which can perpetuate the anxiety itself (Heimberg et al., 2014). Conversely, self-compassion can be related to a reduced reliance on avoidant coping strategies (Allen & Leary, 2010). Since exposure is a core component in anxiety reduction a supportive environment (Gilbert & Simos, 2022), self-compassion may provide this internal support, facilitating exposure and ultimately reducing social anxiety. This is particularly relevant in social settings like classrooms, where students constantly face evaluation and interaction.

The results also indicated that shame mediates the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety. This result is consistent with the research of Cȃndea and Szentágotai-Tătar (2018b), which indicated that self-compassion interventions effectively reduce shame and social anxiety symptoms. One possible explanation for this result lies in how shame is processed. While high shame proneness is linked to various psychological problems, Schoenleber and Berenbaum (2012) argue that considering shame in isolation as a risk factor for psychological distress is insufficient. A key factor influencing the transformation of shame into psychopathology is the extent to which individuals perceive shame as undesirable and painful. Intense aversion to shame can lead to using self-protective strategies against shame, such as avoidance, withdrawal, and escaping. For socially anxious individuals, shame is particularly unpleasant and threatening (Lazarus & Shahar, 2018). Consequently, they may avoid social situations to escape experiencing shame.

Self-compassion offers an alternative approach. It encourages individuals to acknowledge their emotional experiences and soothe themselves while experiencing difficult emotions. Therefore, instead of viewing shame as an unpleasant experience to be avoided, self-compassion helps individuals to acknowledge and validate shame as a normal human experience. By facilitating this process, self-compassion empowers individuals to manage shame more effectively, potentially buffering its negative impact on social anxiety.

Conclusion

The current study provides additional support for the negative relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in university students. Furthermore, it extended existing literature by elucidating how self-compassion can mitigate social anxiety symptoms, specifically by reducing FNE and shame, which are key factors maintaining social anxiety. It can also be concluded that interventions designed to enhance self-compassion can be especially advantageous for socially anxious individuals, especially those experiencing significant levels of FNE and shame.

Limitation and future studies

A few limitations should be considered. First, the sample included volunteer students at public universities in Tehran City, limiting generalizability to other populations. It is necessary to conduct similar studies on clinical and general populations. Second, most women (64%) highlight the need for future research with more diverse samples. Third, the use of a correlational design imposes limitations on the ability to establish causal relationships. In the future, experimental designs are needed to verify the causal hypothesis in this study. Fourth, depression, a common comorbid disorder with SAD, was not assessed, potentially affecting the observed relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms. Future research can include assessments of depression and examine additional mediating variables, such as cognitive and behavioral avoidance, self-criticism, and post-event processing, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of these interactions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Allameh Tabataba’i University (Code: IR.ATU.REC.1401.023).

Funding

This article was extracted from the master's thesis of Fatemeh Sadrzadeh, approved by the Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, review and editing: All authors; Investigation, formal analysis, data curation, original draft preparation: Fatemeh Sadrzadeh; Supervision: Ahmad Borjali and Zohreh Rafezi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for their involvement in this research.

References

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), with a global prevalence rate of 36% in young people (Jefferies & Ungar, 2020), is among the most common anxiety disorders (Bornstein, 2018). Social anxiety involves an excessive concern about potential judgment in social situations and avoidance of them (APA, 2022). Typically, SAD has an onset in early adolescence (Bornstein, 2018), follows a chronic course if untreated (APA, 2022), and shows a high association with other mental health conditions (Koyuncu et al., 2019). It significantly impacts various aspects of life, including occupational, educational, and social functioning (Aderka et al., 2012). Given its pervasive negative consequences, understanding both maintaining and potential protective factors against social anxiety is crucial.

Fear of negative evaluation (FNE) is one of these maintaining factors suggested by cognitive behavioral models (Leigh & Clark, 2018). FNE refers to the concern about being judged or disapproved by others during or in anticipation of social interactions (Kizilcik et al., 2016). For individuals with SAD, this fear results in the employment of avoidance behaviors to minimize the possibility of negative judgment. However, these strategies, while aimed at reducing immediate anxiety, can inadvertently result in the maintenance of the disorder over time (Heimberg et al., 2014).

Longitudinal research supports the role of FNE as a risk factor for increased SAD symptoms (Fredrick & Luebbe, 2024; Zhang et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2020). Furthermore, Tedadi et al. (2022) showed that FNE is a specific vulnerability factor for SAD. Additionally, Swee et al. (2021) stated that individuals concerned about being evaluated in social interactions may be more prone to experience shame as well. Shame, in turn, may be another factor contributing to the persistence of SAD.

Shame is defined as a self-conscious emotion triggered by negative self-evaluation (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). It consists of cognitive (such as believing oneself to be inadequate), behavioral (such as avoiding others), and physiological (such as feeling discomfort in the stomach) patterns (Swee et al., 2021). Frequent, intense experiences of shame become internalized, leading to a global negative self-view and feeling of being flawed (Harper, 2011). Studies demonstrate that higher proneness to experience shame, also known as trait shame (Sedighimornani, 2018), is linked to the development and perpetuation of various psychopathologies (Azevedo et al., 2022; Cândea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2018a), including SAD (Swee et al., 2021).

In this regard, research suggests that more pronounced feelings of shame are reported by individuals with SAD compared to those without the disorder. Additionally, shame contributes to the persistence and exacerbation of SAD symptoms (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024). Moreover, trait shame is associated with more interpersonal problems and elevated symptoms of SAD (Schuster et al., 2021). Likewise, individuals with elevated social anxiety experience more shame proneness and feelings of inadequacy in their daily lives (Lazarus & Shahar, 2018). Additionally, individuals with high levels of shame struggle to show compassion towards themselves, suggesting that a likely helpful approach to counteract shame is self-compassion (Gilbert & Procter, 2006).

Self-compassion was introduced by (Neff, 2003a) based on the Buddhist perspective. It reflects how individuals respond to themselves during life challenges, sufferings, failures, and feelings of inadequacy (Neff, 2003a) and include recognizing internal suffering while being present and open to it (Germer & Neff, 2019). According to Neff, self-compassion comprises three main facets, self-kindness, involving being supportive and empathetic toward one’s suffering rather than adopting a critical and self-judgmental attitude, common humanity, which involves recognizing the universality of human suffering, failures, and feelings of inadequacy as part of the shared human experience, rather than feeling isolated by them, and mindfulness, which entails staying aware and open to the present experience, without ignoring, avoiding or overidentifying with difficult thoughts and emotions.

Research has identified self-compassion as a significant construct in mental well-being (Neff et al., 2018). Consistent with research suggesting the protective benefits of self-compassion against various psychopathologies (Lee et al., 2021; Athanasakou et al., 2020), some research has shown its effectiveness in alleviating social anxiety symptoms (Slivjak et al., 2022; Blackie & Kocovski, 2019). Individuals with SAD typically exhibit negative self-view and engage in harsh self-criticism (Iancu et al., 2015). Self-compassionate perspective represents the opposite stance to these negative cognitions, emphasizing acceptance and kindness toward oneself when facing these challenges (Neff, 2023). This perspective indicates that self-compassion may offer benefits to individuals dealing with social anxiety. However, the mechanisms by which it may alleviate social anxiety need further research. Self-compassion, in altering an individual’s relationship with themselves, likely helps reduce SAD directly and indirectly by lowering FNE and shame, two factors perpetuating the disorder.

Supporting evidence indicates that individuals who adopt a compassionate attitude toward themselves tend to experience diminished levels of evaluation anxiety (Huang & Wang, 2024; Long & Neff, 2018). Furthermore, those who exhibit enhanced self-compassion may be better equipped to manage socio-evaluative stressors, experiencing diminished perceived stress and also reduced feelings of shame (Ewert et al., 2018). Additionally, on the relationship between self-compassion and shame, Cȃndea and Szentágotai-Tătar (2018b) demonstrated that self-compassion training effectively alleviates feelings of shame and reduces symptoms of social anxiety. Similarly, Ross et al. (2019), showed that increased self-compassion, through the reduction of shame, can be indirectly associated with a decrease in depression symptoms, a process that can also be true for social anxiety.

It is worth noting that studies investigating the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in Iran are limited. Given that cultural factors can impact self-compassion (Montero-Marin et al., 2018), it is essential to study this relationship within the context of Iranian culture. Additionally, one group particularly susceptible to performance dysfunction due to social anxiety is students. This is because educational environments involve social evaluation, and those with high FNE may be less inclined to engage in class activities (Long & Neff, 2018) and may even experience a decline in educational functioning (Vilaplana-Pérez et al., 2021). This highlights the necessity of addressing social anxiety among students.

Therefore, this research was conducted to explore the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in a university student population, with a specific focus on exploring the potential mediating roles of FNE and shame.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive-correlational research design was adopted by employing structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess the structural relationships between variables. The statistical population included undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students enrolled in public universities across Tehran City in 2021-2022. The inclusion criteria included willingness to participate with informed consent, and being a current student. The exclusion criteria included completing the questionnaires in less than 6 minutes, which was considered insufficient time for accurate completion.

According to Kline (2023), a minimum sample size of 10-20 times the estimated parameters is recommended for SEM studies. Therefore, based on the 14 parameters estimated in the present study, the minimum sample size can be considered 140. To enhance external validity, 263 participants were selected via a convenience sampling method. A total of 21 participants who completed the questionnaires in a short period were excluded from further consideration, leading to a final sample of 242 for analysis.

Data were collected online by sharing questionnaires in student social media groups on Telegram and WhatsApp. To comply with ethical considerations, the questionnaire’s description stated that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were assured that their personal information would be kept confidential and informed of their option to withdraw from the research at any point.

Instruments

Social phobia inventory (SPIN) (Connor et al., 2000)

This 17-item self-report measure was used to assess social anxiety symptoms. Fear, avoidance behaviors, and physiological symptoms are the three subscales assessed by this tool. A 5-point Likert scale is used to rate the items (0=“not at all”, 4=“extremely”). The total score ranges between 0 to 68. In previous research, Cronbach’s α was reported from 0.82 to 0.94 among social phobia subjects, and from 0.82 to 0.9 in control groups (Connor et al., 2000). In Iran, in a study conducted by Hassanvand Amouzadeh (2016) among students experiencing social anxiety, Cronbach’s α was reported as 0.97, Spearman-Brown as 0.97, and test re-test as 0.82, and the validity of the scale was favorable. In the present research, the overall scale of Cronbach’s α was 0.953. Regarding subscales, 0.876 was obtained for the fear component, 0.903 for avoidance, and 0.843 for physiological symptoms.

Brief FNE scale (BFNE) (Leary, 1983)

This 12-item questionnaire was employed to measure FNE. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“not at all”, 5=“completely”). After reversing items 2, 4, 7, and 10, the total score is determined by summing all the items, ranging from 12 to 60. According to Leary (1983), the original scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.9. In subsequent research on a non-clinical sample of Iranian students, Cronbach’s α was 0.84 for the overall scale, 0.87 for the direct items, and 0.47 for the reverse items (Shokri et al., 2008). In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.871

Test of self-conscious affect (TOSCA-3) (Tangney et al., 2000)

The inclination toward experiencing shame was assessed by this tool. It consists of 16 self-report scenario-based items that assess five self-conscious emotions. For the current research, only the shame-proneness subscale was utilized, focusing on measuring the tendency for negative self-evaluation. The likelihood of each reaction to the described scenario is rated using a 5-point Likert scale (1=“not likely”, 5=“very likely”). All responses are scored directly. The minimum score on the shame subscale is 16, and the maximum is 80. In a study involving three groups of college students, Tangney & Dearing, (2002) reported Cronbach’s α for the shame subscale, ranging from 0.76 to 0.88. In the research conducted by Roshan Chesli et al. (2007), Cronbach’s α of shame proneness was 0.78. The present study yielded a Cronbach’s α of 0.868.

Self-compassion scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003b)

Trait self-compassion was assessed with this 26-item self-report questionnaire. Responses are evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“rarely”, 5=“always”). This tool assesses three bipolar aspects of self-compassion and contains six subscales, self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Items with negative wording are reverse-scored, and the total score is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The minimum score of this measure is 26, and the maximum is 130. Neff, (2003b) reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.92 for the total score and alphas ranging from 0.75 to 0.81 for the subscales. In the research conducted by Khosravi et al. (2013) Cronbach's α was 0.76 for the total score and ranged from 0.79 to 0.85 for the subscales. The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.932.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 22 for descriptive statistics and AMOS software, version 22 to perform SEM.

Results

The present study was conducted on 242 individuals, including 156 women (65.5%) and 86 men (35.5%). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years, with a Mean±SD of 25.07±5.88. Regarding marital status, 206 participants (85.1%) were single, and 26(14.9%) were married. Also, in terms of educational level, 130 participants (53.7%) were undergraduate students, 98(40.5%) were pursuing a master’s degree, and 14(5.8%) were at the doctoral level. Table 1 presents the descriptive indices of the research variables. As shown in Table 1, the values for kurtosis and skewness of all variables were in the acceptable range (±3), suggesting a normal data distribution.

Before examining the structural model, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between each of the variables. Table 2 presents the correlation matrix. Significant relationships were observed among all the variables (P<0.01), justifying the subsequent application of SEM to further explore the underlying structural relationships.

Before model analysis, assumptions of SEM were assessed. Univariate normality of variables was checked using kurtosis and skewness statistics. As shown in Table 1, all variables exhibited kurtosis and skewness values within the range of -3 to +3, suggesting adherence to univariate normality. Multivariate normality was evaluated using Mardia’s normalized multivariate kurtosis value, calculated as 3.531 in the present study. According to Bentler (2005), values above 5 can be considered as a departure from multivariate normality. Therefore, multivariate normality is also established.

Table 3 presents the fit indices, and Figure 1 shows the final model. All fit indices in Table 3 fall within acceptable ranges, indicating a good model fit. The final model accounted for 59% of the variance in social anxiety symptoms.

Table 4 presents the results regarding the direct coefficients between the variables. The analysis revealed that he standardized path coefficient of self-compassion to social anxiety, FNE, and shame were -0.247, -0.633, and -0.533, respectively, and for FNE to social anxiety and shame to social anxiety were 0.371 and 0.326, respectively (P<0.01). Furthermore, the indirect effect of self-compassion on social anxiety symptoms, mediated by FNE and shame, was assessed using the Bootstrap test. The standardized coefficient value obtained was -0.409 (P<0.01), as outlined in Table 4.

Discussion

This study was conducted to explore the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms, with a focus on the mediating roles of FNE and shame. The analysis revealed a well-fitting final model.

The results regarding direct effects indicated a significant direct negative effect of self-compassion on social anxiety symptoms. This result is consistent with the previous research by McBride et al. (2022) and Holas et al. (2021) The contrasting characteristics of self-compassion and SAD can be used to elucidate this result. Social anxiety involves self-criticism, avoidance, and catastrophizing (Hofmann, 2007; Heimberg et al., 2014). Conversely, self-compassion promotes acceptance of the self, self-kindness, a balanced self-view, and acknowledging flaws as part of being human. The theory of emotion regulation systems proposed by Gilbert (2014) can also provide another explanation for this observed relationship. Based on this model, individuals with SAD perceive social interactions as inherently competitive and potentially threatening, which can be associated with the risk of rejection. In this case, over-estimating environmental threats and high self-criticism lead to constant activation of the sympathetic nervous system (Gilbert, 2014). Therefore, the heightened activity of the threat system in these individuals tends to dominate over the activity of the safety system. Self-compassion, by establishing an accepting relationship with oneself and providing self-soothing capacity, can be linked to decreased activation of the sympathetic nervous system, accompanied by a concurrent increase in parasympathetic nervous system activity (Kirschner et al., 2019). The shift in the balance between these two systems can contribute to decreased threat responses and reduced anxiety.

Moreover, the results indicated a direct effect of FNE on social anxiety. This study is consistent with studies by Fredrick & Luebbe (2024), Zhang et al., (2023), and Johnson et al. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral perspectives suggest that shaped by past experiences, individuals with SAD tend to form key assumptions that lead them to set unrealistically high standards for social performance, maintain rigid negative self-perceptions, such as believing they are unlikeable or incompetent, and make negative predictions about the consequences of social behaviors, like expecting to be rejected if they make a mistake (Clark, 2005). These assumptions may lead individuals to overestimate the demands of social interactions while underestimating their social abilities to meet these expectations. As a result, they perceive social situations as overly threatening and overestimate the potential cost of adverse social events. Consequently, they experience excessive fear of being negatively evaluated, leading to heightened anxiety in social settings (Heimberg et al., 2014; Clark, 2005).

The study results also demonstrated a direct effect of shame on social anxiety. This result is consistent with the research conducted by Schuster et al. (2021) and Makadi and Koszycki. (2020). Germer & Neff (2019) posit that shame underlies many difficult emotions and makes them persistent. Anxiety is one such emotion that can arise from shame. Shame stems from the fundamental human need to belong and be accepted by others. It emerges when individuals perceive themselves as so flawed that they cannot be accepted. Negative self-evaluations related to shame, likely rooted in adverse early life experiences (Swee et al., 2021), may underlie the negative self-referential cognitions of social anxiety (Moscovitch, 2009). These negative self-perceptions can further lead to feelings of inferiority, social avoidance behaviors, and a fear of losing social status, all of which are characteristics of social anxiety (Gilbert & Miles, 2000).

Furthermore, the results revealed that self-compassion has a direct negative effect on FNE. This result is consistent with previous studies by Huang & Wang, (2024), and Long and Neff (2018). FNE reflects an excessive concern with one’s public image or social self (Dickerson et al., 2004). Individuals with high FNE often exhibit a deficit in self-affirmation, looking for signs of devaluation and rejection and demonstrating excessive reliance on external evaluative feedback (Heimberg et al., 2014). However, self-compassion can provide a stable source of self-worth and belonging as a human being, irrespective of external judgments (Long & Neff, 2018). As demonstrated by Leary et al., (2007) individuals with greater self-compassion are less influenced by external evaluations and tend to maintain a more realistic view of themselves.

Additionally, the study results revealed that self-compassion has a direct negative effect on shame, replicating previous studies by Etemadi Shamsababdi and Dehshiri (2024) and Ross et al. (2019). Germer & Neff (2019) describe self-compassion as “an antidote to shame”, highlighting the contrasting qualities of the two concepts. Shame is characterized by self-criticism, isolation, and a tendency to view oneself as flawed. In contrast, self-compassion involves accepting oneself as a human being and a sense of belonging to the human race. It also helps individuals understand events as a result of various factors rather than solely personal failings. As Inwood and Ferrari (2018) demonstrated, self-compassion may be an effective strategy as a means of regulating emotions and mitigating feelings of shame.

Investigating indirect effects demonstrated that FNE mediates the link between self-compassion and social anxiety. It is consistent with the results of studies by Liu et al. (2020) and Gill et al. (2018) on adolescents. As mentioned, socially anxious individuals experience heightened FNE due to feelings of inadequacy, perceived inability to meet social standards, and catastrophizing negative evaluation (Clark, 2005). Self-compassion helps individuals accept their imperfections and view social evaluations as less threatening (Breines & Chen, 2012; Ewert et al., 2018), leading to lower FNE and reduced social anxiety. Furthermore, when individuals feel less vulnerable to external judgment, they are less likely to hide their true selves (Long & Neff, 2018). This is crucial because FNE often leads to avoidance behaviors, which can perpetuate the anxiety itself (Heimberg et al., 2014). Conversely, self-compassion can be related to a reduced reliance on avoidant coping strategies (Allen & Leary, 2010). Since exposure is a core component in anxiety reduction a supportive environment (Gilbert & Simos, 2022), self-compassion may provide this internal support, facilitating exposure and ultimately reducing social anxiety. This is particularly relevant in social settings like classrooms, where students constantly face evaluation and interaction.

The results also indicated that shame mediates the relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety. This result is consistent with the research of Cȃndea and Szentágotai-Tătar (2018b), which indicated that self-compassion interventions effectively reduce shame and social anxiety symptoms. One possible explanation for this result lies in how shame is processed. While high shame proneness is linked to various psychological problems, Schoenleber and Berenbaum (2012) argue that considering shame in isolation as a risk factor for psychological distress is insufficient. A key factor influencing the transformation of shame into psychopathology is the extent to which individuals perceive shame as undesirable and painful. Intense aversion to shame can lead to using self-protective strategies against shame, such as avoidance, withdrawal, and escaping. For socially anxious individuals, shame is particularly unpleasant and threatening (Lazarus & Shahar, 2018). Consequently, they may avoid social situations to escape experiencing shame.

Self-compassion offers an alternative approach. It encourages individuals to acknowledge their emotional experiences and soothe themselves while experiencing difficult emotions. Therefore, instead of viewing shame as an unpleasant experience to be avoided, self-compassion helps individuals to acknowledge and validate shame as a normal human experience. By facilitating this process, self-compassion empowers individuals to manage shame more effectively, potentially buffering its negative impact on social anxiety.

Conclusion

The current study provides additional support for the negative relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms in university students. Furthermore, it extended existing literature by elucidating how self-compassion can mitigate social anxiety symptoms, specifically by reducing FNE and shame, which are key factors maintaining social anxiety. It can also be concluded that interventions designed to enhance self-compassion can be especially advantageous for socially anxious individuals, especially those experiencing significant levels of FNE and shame.

Limitation and future studies

A few limitations should be considered. First, the sample included volunteer students at public universities in Tehran City, limiting generalizability to other populations. It is necessary to conduct similar studies on clinical and general populations. Second, most women (64%) highlight the need for future research with more diverse samples. Third, the use of a correlational design imposes limitations on the ability to establish causal relationships. In the future, experimental designs are needed to verify the causal hypothesis in this study. Fourth, depression, a common comorbid disorder with SAD, was not assessed, potentially affecting the observed relationship between self-compassion and social anxiety symptoms. Future research can include assessments of depression and examine additional mediating variables, such as cognitive and behavioral avoidance, self-criticism, and post-event processing, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of these interactions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Allameh Tabataba’i University (Code: IR.ATU.REC.1401.023).

Funding

This article was extracted from the master's thesis of Fatemeh Sadrzadeh, approved by the Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, review and editing: All authors; Investigation, formal analysis, data curation, original draft preparation: Fatemeh Sadrzadeh; Supervision: Ahmad Borjali and Zohreh Rafezi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for their involvement in this research.

References

Aderka, I. M., Hofmann, S. G., Nickerson, A., Hermesh, H., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., & Marom, S. (2012). Functional impairment in social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3), 393-400. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.003] [PMID]

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(2), 107-118. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x] [PMID]

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TRTM). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787]

Athanasakou, D., Karakasidou, E., Pezirkianidis, C., Lakioti, A., & Stalikas, A. (2020). Self-compassion in clinical samples: A systematic literature review. Psychology, 11, 217-244. [DOI:10.4236/psych.2020.112015]

Azevedo, F., André, R., Quintão, A., Jeremias, D., & Almeida, C. (2022). Shame and psychopathology. Its role in the genesis and perpetuation of different disorders. European Psychiatry, 65(S1), S703-S703. [DOI:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1811]

Bentler, P. M. (2005). EQS 6 Structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software Inc. [Link]

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2019). Trait self-compassion as a buffer against post-event processing following performance feedback. Mindfulness, 10(5), 923-932. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-018-1052-7]

Bornstein, M. H. (Ed.). (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of lifespan human development. California: SAGE Publications. [DOI:10.4135/9781506307633]

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133-1143. [DOI:10.1177/0146167212445599] [PMID]

Cândea, D. M., & Szentagotai-Tătar, A. (2018). Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58, 78-106. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.07.005] [PMID]

Cȃndea, D. M., & Szentágotai-Tătar, A. (2018). The impact of self-compassion on shame-proneness in social anxiety. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1816-1824. [Link]

Clark, D. M. (2005). A cognitive perspective on social phobia. In W. R. Crozier & L. E. Alden (Eds.), The essential handbook of social anxiety for clinicians (pp. 193-218). New Jersey: Wiley. [Link]

Connor, K. M., Davidson, J. R., Churchill, L. E., Sherwood, A., Foa, E., & Weisler, R. H. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). New self-rating scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 176, 379-386. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.176.4.379] [PMID]

Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 355–391. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355] [PMID]

Etemadi Shamsababdi, P., & Dehshiri, G. R. (2024). Self-compassion, anxiety and depression symptoms; the mediation of shame and guilt. Psychological Reports.[DOI:10.1177/00332941241227525]

Ewert, C., Gaube, B., & Geisler, F. C. M. (2018). Dispositional self-compassion impacts immediate and delayed reactions to social evaluation. Personality and Individual Differences, 125, 91-96. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.037]

Fredrick, J. W., & Luebbe, A. M. (2024). Prospective associations between fears of negative evaluation, fears of positive evaluation, and social anxiety symptoms in adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 55(1), 195-205. [DOI:10.1007/s10578-022-01396-7] [PMID]

Germer, C., & Neff, K. (2019). Teaching the mindful self-compassion program: A guide for professionals. New York: Guilford Publications. [Link]

Gilbert, P. (2014). Evolutionary models: Practical and conceptual utility for the treatment and study of social anxiety disorder. In J. W. Weeks (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of social anxiety disorder (pp. 24-52). New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell. [DOI:10.1002/9781118653920.ch2]

Gilbert, P., & Miles, J. N. V. (2000). Sensitivity to social put-down: Its relationship to perceptions of social rank, shame, social anxiety, depression, anger and self-other blame. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(4), 757-774. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00230-5]

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353-379. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.507]

Gilbert, P., & Simos, G. (Eds.). (2022). Compassion focused therapy: Clinical practice and applications. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9781003035879]

Gill, C., Watson, L., Williams, C., & Chan, S. W. (2018). Social anxiety and self-compassion in adolescents. Journal of adolescence, 69, 163-174. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.004] [PMID]

Harper, J. M. (2011). Regulating and coping with shame. In: R. Trnka, K. Balcar, & M. Kuska(Eds.), Re-constructing emotional spaces: From experience to regulation(pp. 189-206). Prague: Prague University Psychosocial Studies Press. [Link]

Hassanvand Amouzadeh, M. (2016). [Validity and reliability of social phobia inventory in students with social anxiety (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, 26(139), 166-177. [Link]

Heimberg, R. C., Brozovich, F. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2014). A cognitive-behavioral model of social anxiety disorder. In S. G. Hofmann, & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (pp. 705-728). Massachusetts: Elsevier Academic Press. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-394427-6.00024-8]

Hofmann S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 193–209. [DOI:10.1080/16506070701421313] [PMID]

Holas, P., Kowalczyk, M., Krejtz, I., Wisiecka, K., & Jankowski, T. (2021). The relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion in socially anxious. Current Psychology, 42, 10271–10276. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-02305-2]

Huang, T., & Wang, W. (2024). Relationship between fear of evaluation, ambivalence over emotional expression, and self-compassion among university students. BMC Psychology, 12, 128. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-024-01629-5]

Iancu, I., Bodner, E., & Ben-Zion, I. Z. (2015). Self esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 165-171. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.018]

Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 215-235. [DOI:10.1111/aphw.12127]

Jefferies, P., & Ungar, M. (2020). Social anxiety in young people: a prevalence study in seven countries. PloS One, 15(9), e0239133. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0239133] [PMID]

Johnson, A. R., Bank, S. R., Summers, M., Hyett, M. P., Erceg-Hurn, D. M., & Kyron, M. J., et al. (2020). A longitudinal assessment of the bivalent fear of evaluation model with social interaction anxiety in social anxiety disorder. Depression and anxiety, 37(12), 1253-1260. [DOI:10.1002/da.23099] [PMID]

Khosravi, S., Sadeghi, M., & Yabandeh, M. (2013). [Psychometric Properties of Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) (Persian)]. Psychological Models and Methods, 4(13), 47-59. [Link]

Kirschner, H., Kuyken, W., Wright, K., Roberts, H., Brejcha, C., & Karl, A. (2019). Soothing your heart and feeling connected: A new experimental paradigm to study the benefits of self-compassion. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(3), 545-565. [DOI:10.1177/2167702618812438]

Kizilcik, I. N., Gregory, B., Baillie, A. J., & Crome, E. (2016). An empirical analysis of Moscovitch’s reconceptualised model of social anxiety: How is it different from fear of negative evaluation? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 64-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.11.005]

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications. [Link]

Koyuncu, A., İnce, E., Ertekin, E., & Tükel, R. (2019). Comorbidity in social anxiety disorder: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Drugs in Context, 8, 212573. [DOI:10.7573/dic.212573]

Lazarus, G., & Shahar, B. (2018). The role of shame and self-criticism in social anxiety: A daily-diary study in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(2), 107-127. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2018.37.2.107]

Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371-375. [DOI:10.1177/0146167283093007]

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887-904. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887]

Lee, E. E., Govind, T., Ramsey, M., Wu, T. C., Daly, R., & Liu, J., et al. (2021). Compassion toward others and self-compassion predict mental and physical well-being: A 5-year longitudinal study of 1090 community-dwelling adults across the lifespan. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 397. [DOI:10.1038/s41398-021-01491-8] [PMID]

Leigh, E., & Clark, D. M. (2018). Understanding social anxiety disorder in adolescents and improving treatment outcomes: Applying the cognitive Model of Clark and Wells (1995). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 388-414. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-018-0258-5] [PMID]

Liu, X., Yang, Y., Wu, H., Kong, X., & Cui, L. (2020). The roles of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness: A serial mediation model. Current Psychology, 41, 5249–5257. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-020-01001-x]

Long, P., & Neff, K. D. (2018). Self-compassion is associated with reduced self-presentation concerns and increased student communication behavior. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 223-231. [DOI:10.1016/j.lindif.2018.09.003]

Makadi, E., & Koszycki, D. (2020). Exploring connections between self-compassion, mindfulness, and social anxiety. Mindfulness, 11(2), 480-492. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-019-01270-z]

McBride, N. L., Bates, G. W., Elphinstone, B., & Whitehead, R. (2022). Self-compassion and social anxiety: The mediating effect of emotion regulation strategies and the influence of depressed mood. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 95(4), 1036-1055. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12417]

Montero-Marin, J., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Gu, J., Baer, R., & Al-Awamleh, A. A., et al. (2018). Self-compassion and cultural values: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Compassion Using a Multitrait-Multimethod (MTMM) Analytical Procedure. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2638. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02638]

Moscovitch, D. A. (2009). What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(2), 123-134. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.04.002]

Neff, K. (2003). Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85-101. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309032]

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223-250. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309027]

Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-Compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 193-218. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047]

Neff, K. D., Long, P., Knox, M. C., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., & Costigan, A., et al. (2018). The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity, 17(6), 627-645. [DOI:10.1080/15298868.2018.1436587]

Oren-Yagoda, R., Rosenblum, M., & Aderka, I. M. (2024). Gender differences in shame among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 48, 720–729. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-023-10461-x]

Roshan Chasli, R., Atrifard, M., & Noori Moghaddam, S. (2007). [An Investigation of reliability and validity of the third version of (Persian)]. Journal of Daneshvar Behavior, 5(2), 31-46. [Link]

Ross, N. D., Kaminski, P. L., & Herrington, R. (2019). From childhood emotional maltreatment to depressive symptoms in adulthood: The roles of self-compassion and shame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 32-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.016] [PMID]

Schoenleber, M., & Berenbaum, H. (2012). Shame regulation in personality pathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(2), 433-446. [DOI:10.1037/a0025281] [PMID]

Schuster, P., Beutel, M. E., Hoyer, J., Leibing, E., Nolting, B., & Salzer, S., et al. (2021). The role of shame and guilt in social anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 6, 100208. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100208]

Sedighimornani, N. (2018). Shame and its features: Understanding of shame. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 3(3). [Link]

Shokri, O., Geravand, F., Naghsh, Z., Ali Tarkhan, R., & Paeezi, M. (2008). [The psychometric properties of the brief fear of negative evaluation scale (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 14(3), 316-325. [Link]

Slivjak, E. T., Pedersen, E. J., & Arch, J. J. (2022). Evaluating the efficacy of common humanity-enhanced exposure for socially anxious young adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 87, 102542. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102542]

Swee, M. B., Hudson, C. C., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Examining the relationship between shame and social anxiety disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 90, 102088. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102088]

Tangney, J. P., Dearing, R. L., Wagner, E E., & Gramzow, R. (2000). Test of Self- Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3). Fairfax: George Mason University. [DOI:10.1037/t06464-000]

Tedadi, Y., Rahiminezhad, A., & Karsazi, H. (2022). [The General and Specific vulnerability factors of anxiety disorders: Evaluation of a structural model (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 14(4), 27-37. [DOI:10.22075/jcp.2022.26830.2431]

Vilaplana-Pérez, A., Pérez-Vigil, A., Sidorchuk, A., Brander, G., Isomura, K., & Hesselmark, E., et al. (2021). Much more than just shyness: the impact of social anxiety disorder on educational performance across the lifespan. Psychological Medicine, 51(5), 861-869. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291719003908]

Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Gao, W., Chen, W., Xiao, Z., & Qi, Y., et al. (2023). From fears of evaluation to social anxiety: The longitudinal relationships and neural basis in healthy young adults. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology: IJCHP, 23(2), 100345. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100345]

Type of Study: Original Research Article |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2024/05/28 | Accepted: 2024/07/29 | Published: 2024/10/2

Received: 2024/05/28 | Accepted: 2024/07/29 | Published: 2024/10/2

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |