Volume 11, Issue 4 (Autumn 2023)

PCP 2023, 11(4): 329-340 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zohrabiy S, Abolghasemi A, Kafi Masoole M, Khosrojavid M. Comparing the Effectiveness of Emotion-focused Therapy and the Unified Trans-diagnostic Treatment on Fear of Negative and Positive Evaluation of Patients With Social Anxiety Disorder. PCP 2023; 11 (4) :329-340

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-896-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-896-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran. , Shima.zohrabi@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

Keywords: Emotion-focused therapy, Unified trans-diagnostic treatment, Fear of negative and positive evaluation, Social anxiety disorder.

Full-Text [PDF 648 kb]

(238 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1019 Views)

Full-Text: (155 Views)

1. Introduction

Anxiety means being scared or worried about what may happen in the future (Hamm, 2020). Research studies have found that anxiety disorders are very common and can significantly impact a person’s ability to function normally. They are the most common mental disorders in our society (Martin, 2003). According to large population-based surveys, up to 33.7% of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime (Bandelow & Michaelis, 2022). The disorder begins at an early stage of development and often precedes the onset of other conditions, such as anxiety disorders, alcohol misuse, and major depression (Goldin et al., 2016). Social anxiety has a great impact on diminishing performance in several areas of life and reducing happiness and health (Goodman et al., 2021). Individuals with social anxiety are more at risk of being bullied and have a higher chance of leaving school early with insufficient accomplishments (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020). Having this condition regularly leads to a decreased number of acquaintances, a decreased likelihood of getting married, an increased chance of divorce, and a reduced probability of becoming a parent. According to reports, individuals experience more days absent from work and decreased performance at work (Jefferies & Ungar, 2020).

As Pittelkow et al. stated, the persistent symptoms of this disorder often become chronic and show no signs of improvement without proper treatment (Pitelkow et al., 2021). According to the research conducted by Butler et al., individuals facing this condition undergo significant disruptions in their personal, professional, educational, and emotional bonds, along with a decline in their standard of living (Butler et al., 2018). Anxiety disorder in social situations is commonly diagnosed via the primary symptom of the fear of negative evaluations, which is widely accepted in the theoretical models of this condition (Reichenberger et al., 2019). Lee and Kwon describe the fear of negative evaluation as a complex construct that involves not only apprehension and concern over how others will judge us but also the anxiety caused by such assessments and the belief that others will only perceive us in a negative light (Lee & Kwon, 2013). According to Okawa et al. (2012) when individuals receive negative criticism, they may develop the impression that others have a negative view of them, which can cause rejection.

Weeks et al., (2008) introduced the two-way paradigm of anxiety regarding evaluation to illustrate the relationship between apprehension toward receiving positive feedback and uncertainty in social environments. The proposed theory suggests that individuals with social anxiety are highly receptive to both negative and positive feedback from their peers, which they perceive as potential social risks (Yap et al., 2016). The fear of positive evaluation is the fear associated with positive judgment and compared to others, which can lead to exposure and vulnerability. This fear is often experienced by individuals with a social anxiety disorder who worry that positive evaluations of future social standards that they will fail to meet will increase, ultimately strengthening their fear of negative evaluation (Reichenberger et al., 2019).

Due to the wide prevalence and early manifestation of this condition, along with the limited likelihood of spontaneous improvement without psychological intervention, prompt identification and implementation of effective treatment are crucial. The emotion-focused treatment model states that individuals with social anxiety disorder experience anxiety due to feeling ashamed. This anxiety is a secondary emotional reaction. The theory proposes that people who have endured challenges in childhood, such as harsh criticism or bullying, develop a mental pattern rooted in shame. This issue can cause a perpetual sense of incompleteness and fragility, as well as an aversion to being judged negatively or rejected by society. The individual may be especially sensitive to feelings of shame in social interactions (Elliott & Shahar, 2017). Numerous studies have found strong evidence that people who are bullied online have a lot of anxiety in social situations (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020; Jefferies & Ungar, 2020). Expecting to experience shame can cause people to feel anxious and avoid social gatherings. As a result, they may struggle to address the root of their shame and unintentionally amplify their anxiety levels (Hedman et al., 2013). Elliott and Shahar presented the emotion-focused therapy (EFT) theory of social anxiety and described its developmental origins in the experience of social deterioration, leading to underlying emotional processes being organized around a self that feels flawed and consumed by shame. These create secondary reactive anxiety that others will see the person’s flaws, organized around the coach/critic/guardian aspect of the self, when trying to protect the person from exposure, unintentionally creating the emotional dysregulation characteristic of social anxiety (Elliott & Shahar, 2017). According to Haberman et al., people witness therapeutic change when faced with shame rather than avoidance. Shame can be altered or changed by activating beneficial emotions, such as strong and courageous anger, as well as sadness linked to a need for deeper relationships and self-compassion, which had been suppressed (Haberman et al., 2019).

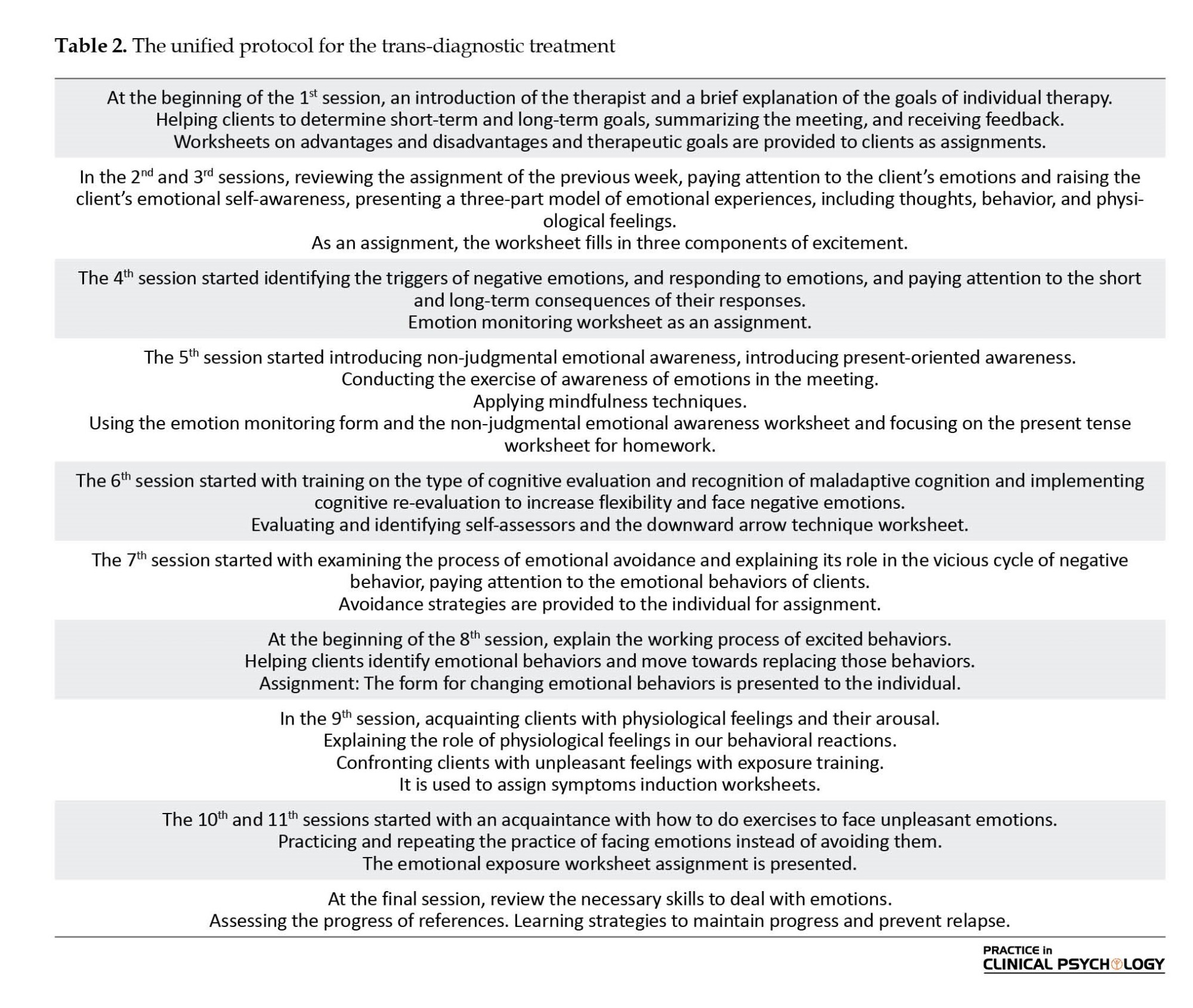

Moreover, a novel treatment is available that addresses the primary ailment along with any concurrent anxiety or depression disorders by simultaneously managing common symptoms and fundamental psychological procedures. This approach is called the unified trans-diagnostic treatment (Deer et al., 2016). The unified protocol for the trans-diagnostic treatment is an emotion-based cognitive-behavioral intervention that comprises five fundamental components that target identity characteristics, particularly neuroticism, and as a result, superstructure emotional dysregulation of all anxiety disorders, depression, and related disorders. By tending to the usual mechanisms related to neuroticism, particularly negative appraisal, and avoidance of emotional experience, this approach can rearrange instructive endeavors and address concerns related to its generalizability to usual care sets for comorbid emotional disorders (Barlow et al., 2017). Transdiagnostic treatment helps students feel less anxious, worried, and depressed. It also reduces anxiety and panic. Additionally, it helps increase positive feelings for students experiencing social anxiety symptoms (Laposa et al., 2017; García-Escalera et al., 2017; Arshadi et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2023; Ghaderi et al., 2023).

Limited research has targeted emotion regulation as a central component in the treatment of this disorder. Furthermore, as social creatures, humankind must possess adaptable skills in society to ensure their survival. Psychologists have constantly sought methods to enhance human social interactions. Social anxiety disorder can disturb an individual’s connections with others and suggest a threat to their routine existence. Thus, employing therapies that focus on pinpointing the particular contributing factors of this condition and subsequently aiming to develop meaningful intervention approaches can enhance the social engagement of individuals affected by it. From previous remarks, the techniques emphasizing emotion regulation may be useful in lessening symptoms associated with social anxiety. Novel research exploring the efficacy of trans-diagnostic therapy as an alternative treatment method to manage emotional regulation has not been independently conducted in individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder in international studies.

In this context, it should be mentioned that most studies on anxiety disorder and the trans-diagnostic approach, whether in the population or clinical sub-samples, have been conducted in very few numbers with the Iranian population. Given the significance of recent research regarding emotion regulation as a crucial factor in this disorder, this study is the first to examine and contrast the efficacy of two treatments targeted at promoting emotion regulation among affected individuals. The study was conducted to compare the efficacy of EFT and the unified trans-diagnostic treatment for individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder.

2. Materials and Methods

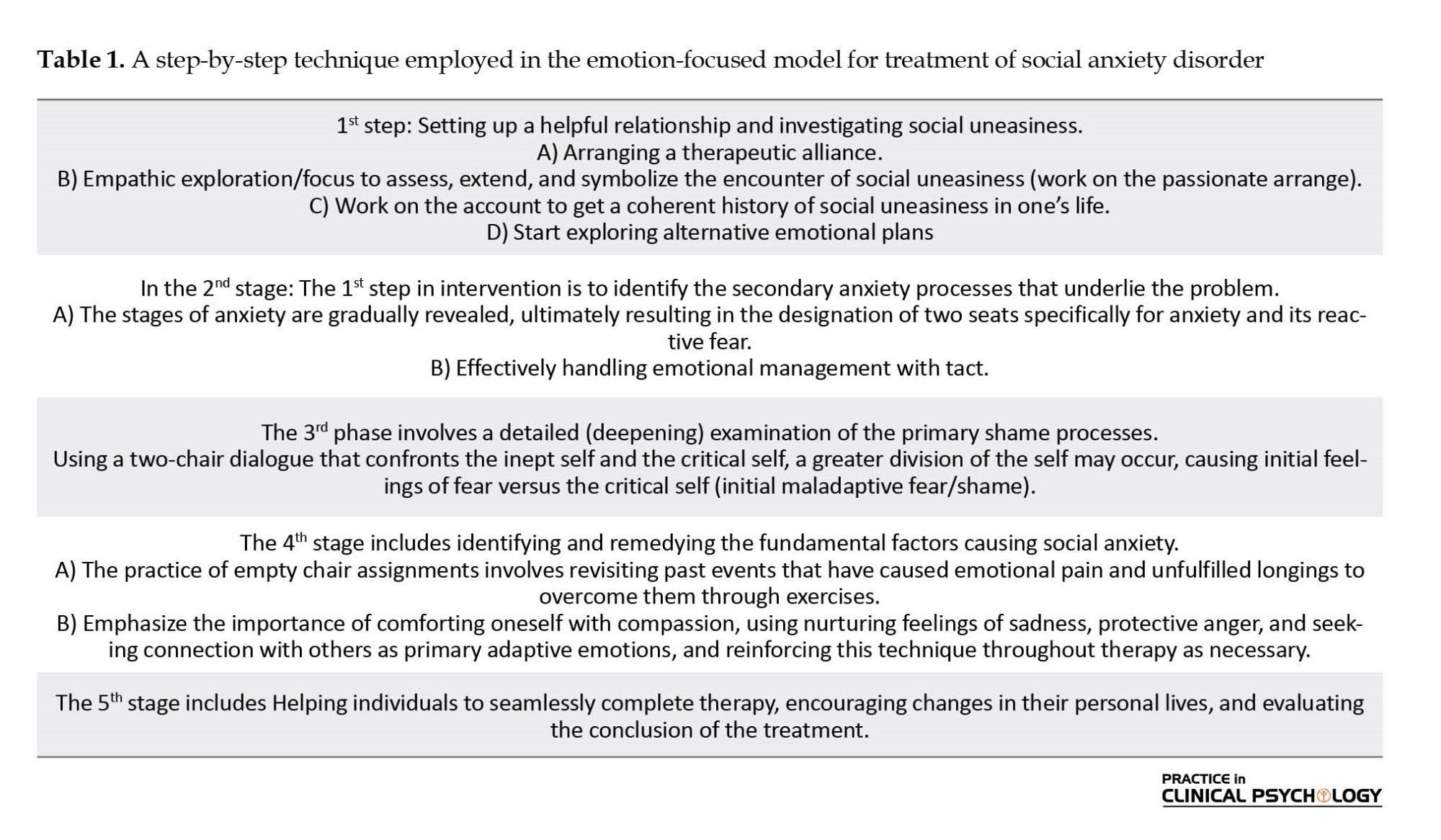

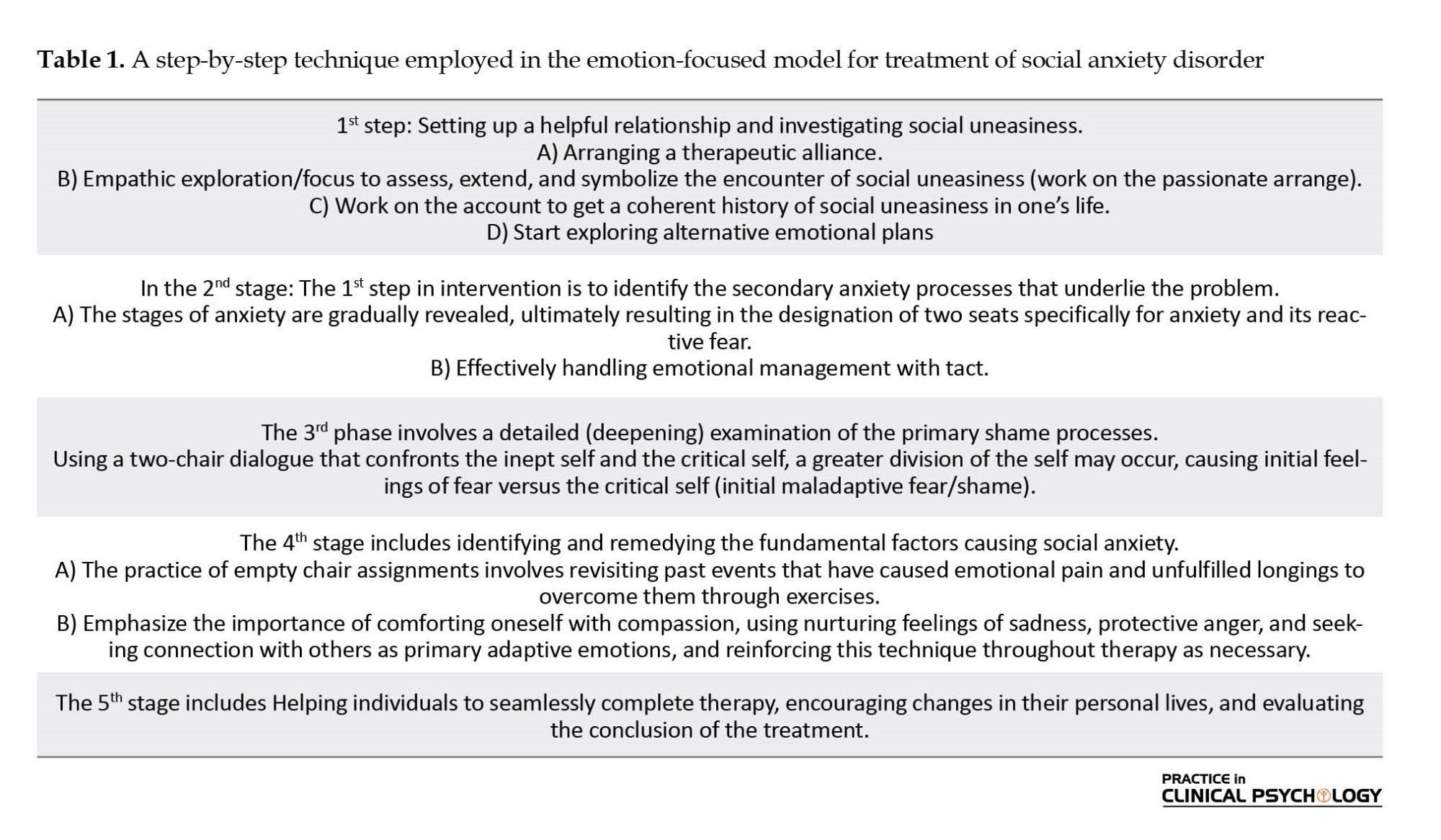

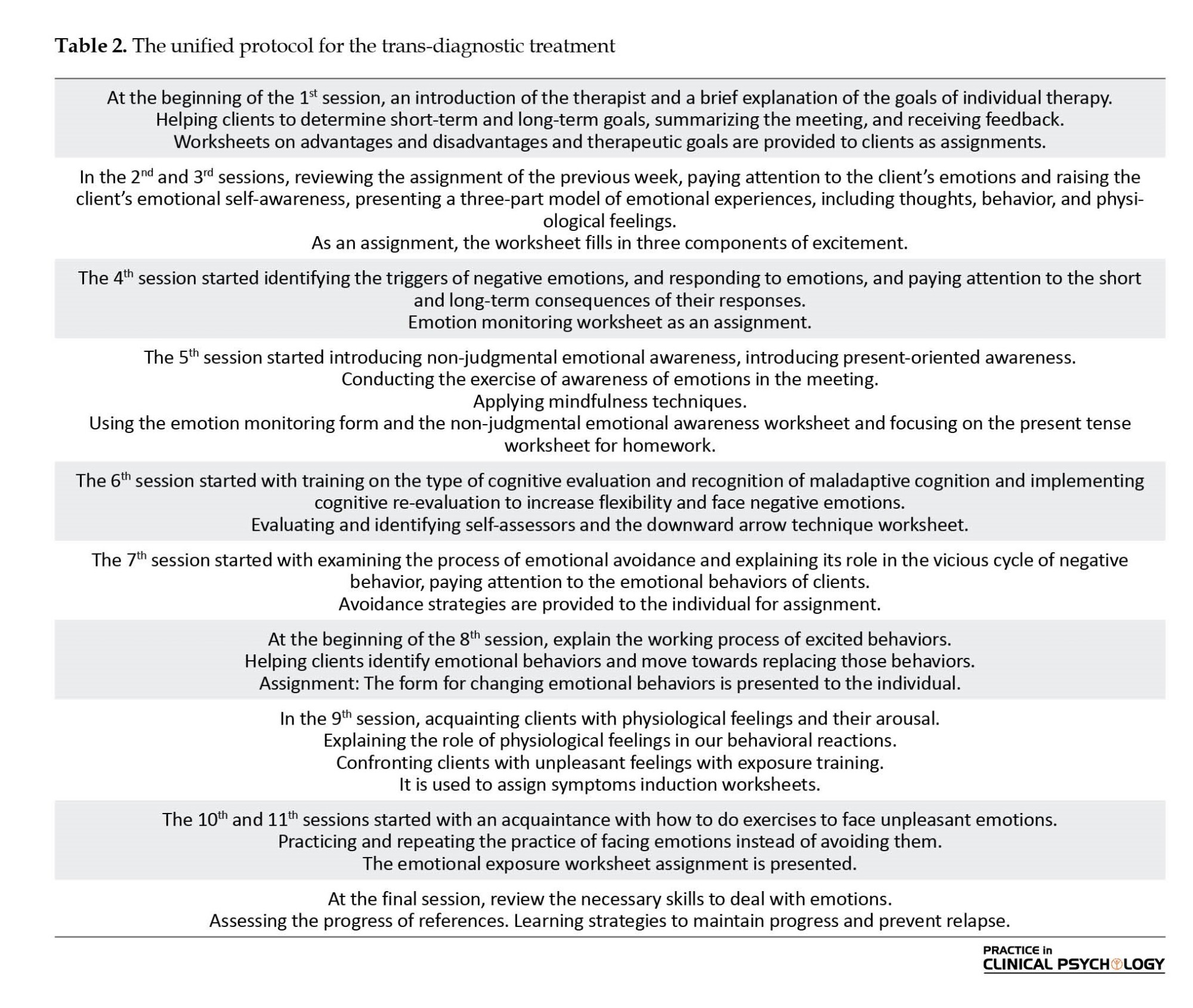

This research was a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test-post-test control group design and a three-month follow-up. The statistical population of the study included all people aged 18-40 years who were referred to the Vian Clinic and all the people who were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder through the calls announced in the virtual space from September to March 2021 in Tehran City. A total of 21 patients were selected using purposive sampling and assigned to three groups (two experimental groups and one control group (7 patients in each group). The authors randomly selected people from each group by flipping a coin. To make a random decision, people usually throw a coin into the air and see which side lands facing up. We selected the experimental group by flipping a coin for each person. The people who landed on heads were chosen into the control group (Table 1 and Table 2). The participants were selected via purposive sampling considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research.

Inclusion criteria

Obtaining a cut-off score in the social phobia questionnaire and confirming the diagnosis of the disorder based on the diagnostic clinical interview according to the structured clinical interview for DSM-5® disorders-clinician version (SCID-5-CV), and at least having diploma education.

Exclusion criteria

The participant was affected by other psychotherapy and counseling programs related to the same or other psychological problems, taking psychoactive drugs or addictive substances, having personality disorders, psychosis, and bipolar disorder based on structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-V), and not attending over 3 treatment sessions.

Study procedure

After obtaining permission from the university and visiting the Vian Clinic and all the people who were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder through the calls announced in the virtual space from September to March 2021 in Tehran City (based on the research criteria), the people who were willing to participate in the research were referred to one of the psychology clinics (Vian Clinic) in Tehran City. After the people with social anxiety disorder went to Vian’s Clinical Psychology Center, they were accepted by the researcher (with a candidate PhD degree in psychology). At this stage, the participants were introduced to the aims, process, and consequences of the research. Then, after obtaining written consent from the individuals, a pre-test of psychological distress was performed among them.

The experimental groups 1 and 2 received EFT (Elliott & Shahar, 2017) in twenty 120-minute sessions (one session every week) and the unified trans-diagnostic treatment (Barlow et al., 2017) in twelve 120-minute sessions (one session every week), respectively, while the control group was placed on the treatment waiting list. After completing the training sessions, the experimental and control groups were tested in the same conditions, and three months later, the subjects were evaluated in the follow-up phase. All participants were evaluated at the pre-test and post-test stages using the research instruments.

After collecting a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), pre-test, post-test, and follow-up data were analyzed. One of the principles of ethical compliance is informed consent and non-violation of the rights of the participants in the research observance of human rights and confidentiality of their research results. Furthermore, after completing the training sessions on the educational groups and performing post-test and follow-up, the treatment sessions were administered intensively to observe the ethical principles of the control group. The following instruments were used to collect data:

The brief fear of negative evaluation scale (BFNE): The BFNE is a method to measure the anxiety level of a person feels when they think they are being judged or evaluated negatively. This scale has 12 questions that ask about thoughts that make you scared or worried. The person answering the questions rates how much each item represents them using a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Out of the twelve elements, eight of them are about being scared or worried, and the other four are about not being scared or worried. It was also clear that the fear of negative evaluation questionnaire has very reliable results (Cronbach’s α=0.9). The re-test method was used to check reliability for four weeks. It showed a correlation of 0.75. How the factors are organized is not clear. Some people think there is only one factor, while others, using a group of people with clinical conditions, have found that there are two factors. These factors consist of statements that are either positive or negative. In simple words, this means that when comparing this scale to other questionnaires about social phobia and social interaction anxiety in Iranian society, the results showed that the scale was reliable and accurate. The convergent validity for the social phobia questionnaire was 0.43, and for the social interaction anxiety scale, it was 0.54.

The fear of positive evaluation scale (FPES)

The FPES is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess this construct (Weeks et al., 2008). The FPES consists of 10 statements that are graded on a scale from zero (not true at all) to 9 (completely true). In their study on a sample of 1 711 undergraduate students, Weeks et al. reported a Mean±SD total score of 2.36±13.07 for this version. Also, the internal consistency with Cronbach’s α method is 0.80 and the five-week re-test reliability is 0.70. In Iranian society, the reliability coefficient was calculated as 0.67 by the two-half method and Cronbach’s α as 0.75 for the whole test.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24 using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of the data. Using Leven’s test, researchers sought to ascertain if the variances showed homogeneity. In this study, repeated measures ANOVA was used.

3. Results

The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate no significant variations between the three groups in terms of demographic variables, including age (ANOVA), and marital status (chi-square test). The three groups can be considered homogeneous due to the presence of the desired variables

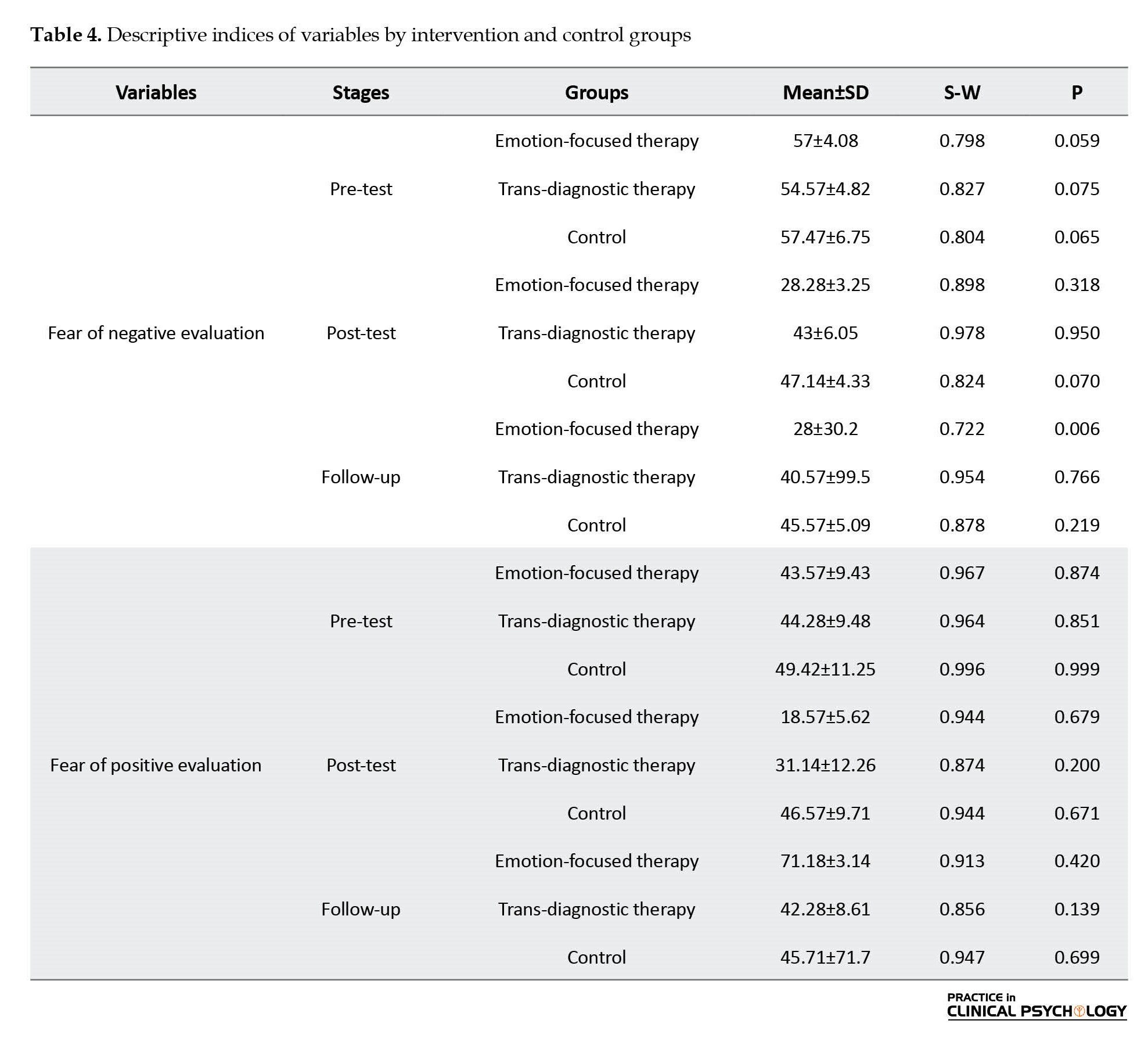

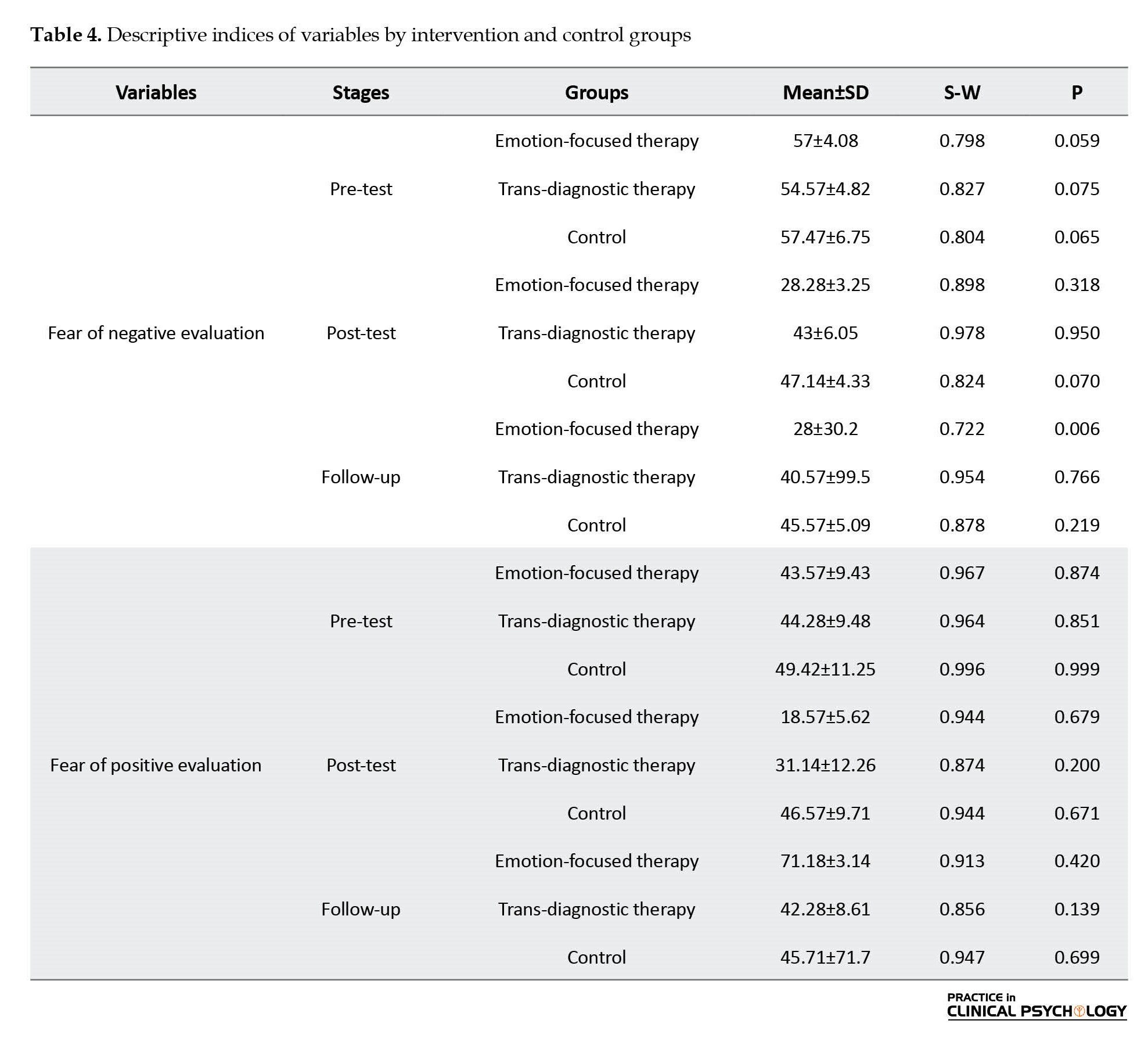

To meet the statistical assumption of normality, the results of the Shapiro-wilk test were non-significance (P>0.05). In other words, the assumption of normality was confirmed. Also, the results in Table 4 showed that the normal of the three groups (two test groups and one control group) have differences within the pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up.

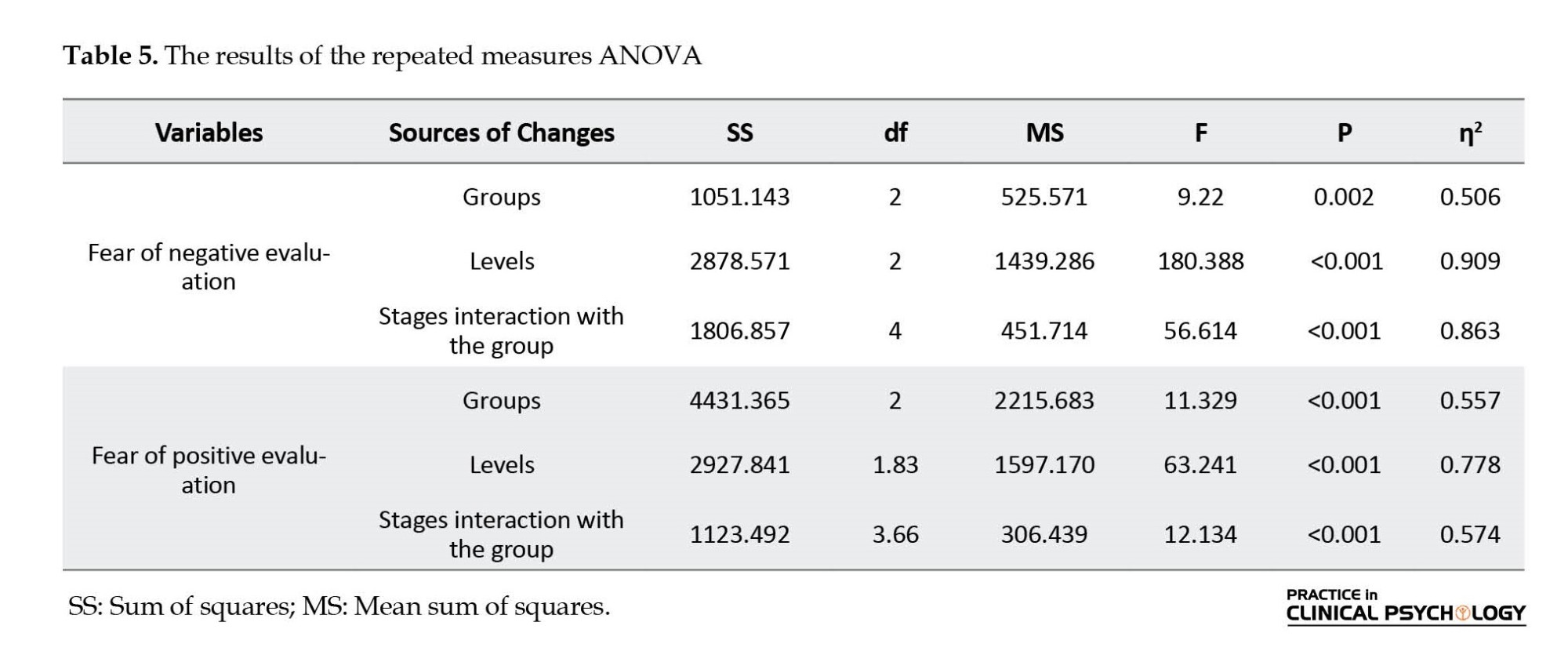

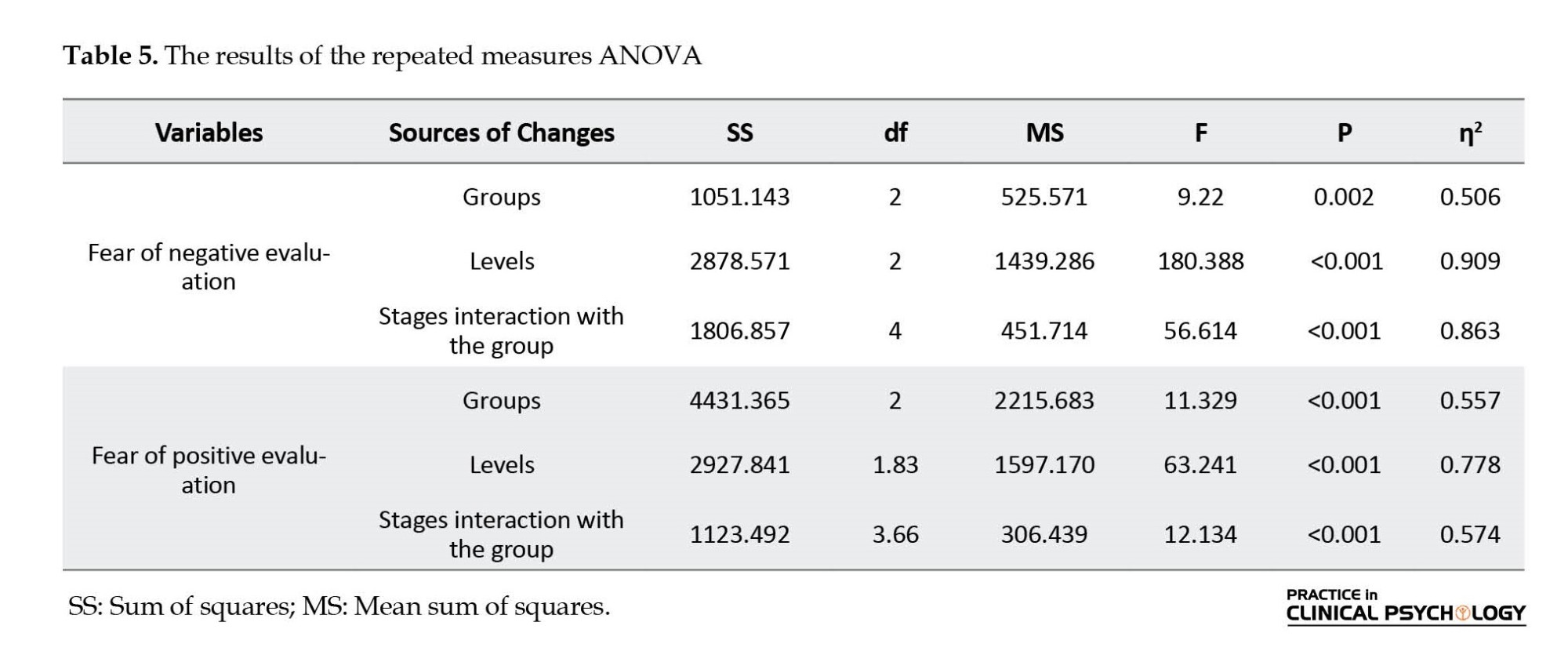

As Table 5, the relationship between different stages and groups affecting fear of negative evaluation is significant (η2=0.909, F=56.614, P<0.05). This means that a significant difference is observed between the group that did the experiment and the group that did not experiment in terms the fear of negative judgment, in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05).

Also, the results of a simple mixed ANOVA test showed that the main effect of the within-group factor on fear of negative evaluation (η2=0.381, F=180.388) is significant (P<0.05). Regardless of the group they belong to, the results indicated that everyone’s apprehension improved negative evaluation.

In the continuation of the results, the main effect of the between-group factor on the fear of negative evaluation (η2=0.506, F=9.22) is significant (P<0.05). Consequently, the results indicated that different groups show varying degrees of fear towards negative judgments. (P<0.05).

As the results in Table 5 show, the interaction effect of steps and group on the fear of positive evaluation (η2=0.574, F=12.134) is significant (P<0.05). This shows that the experimental group and control group had different levels of fear of positive evaluation during the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05).

The results of the simple mixed ANOVA test also indicated that the main effect of the within-group factor on academic performance (η2=0.778, F=63.241) is significant (P<0.05). Over time, this study discovered that people’s fear of praise or positive evaluation fluctuated up and down, independent of the group.

The results of the main effect of the between-group factor on the fear of positive evaluation (η2=0.557, F=11.329) are significant (P<0.05). Therefore, the results showed a difference between the studied groups in terms of fear of positive evaluation (P<0.05).

The results in Table 6 showed a significant difference between the post-test and follow-up periods in terms of people’s fear of negative evaluation; thus, the mean level of fear of negative evaluation scores in the post-test phase compared to the pre-test phase was significantly reduced, and this decrease continued until the next phase. The results in Table 6 showed a significant difference in people’s mean scores between the post-test and follow-up periods due to fear of positive evaluation; therefore, the mean fear of positive evaluation score at the post-test decreased significantly compared to the pre-test, and this decrease continued until the follow-up period.

The results in Table 7 showed that the mean difference between the two groups of EFT and unified trans-diagnostic treatment was significantly different. However, the mean difference between the control treatment group and the trans-diagnostic treatment group was not significant. Thus, metabolic diagnostic treatments were unsuccessful in reducing the fear of negative evaluation of the target sample. Furthermore, the results in Table 7 showed the significant effectiveness of both treatments in reducing fear of positive evaluation scores in the sample group. Furthermore, the results showed no significant difference between the effectiveness of EFT and the unified protocol for cross-cutting diagnostic treatment in reducing fear scores on positive evaluation.

4. Discussion

The study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of EFT and trans-diagnostic treatment in reducing the fear of negative and positive evaluations in people with a social anxiety disorder. According to the study, EFT had a significant impact on lowering the fear of negative evaluation in the experimental group compared to the control group. In contrast, trans-diagnostic treatment was not effective in curbing this fear in the experimental group. The current study’s results are consistent with Shahar et al.’s research on the effectiveness of EFT in decreasing the fear of negative evaluation. Individuals with social anxiety disorder experience feelings of fear and tend to switch their attention to their internal state and their anxious reactions when they are exposed to frightening social situations. Due to increased self-awareness and critical insight, individuals form a distorted impression of themselves and further believe that others perceive them similarly, ultimately resulting in a negative self-evaluation (Lee & Kwon, 2013).

As mentioned earlier, self-criticism is a common trait among people with social anxiety. Additionally, Heinonen and Pos showed that all pre-treatment interpersonal problems were clearly associated with patients’ negative self-evaluations during therapy (Heinonen & Pos, 2020). According to the complex model, the personal experience of revenge was more associated with the emotional expressions of anger denial during the session and the personal experience of social inhibition to express fear and shame. In minimizing long-term interpersonal problems, reaching a state of emotional distress and grief in particular appears to benefit patients who consider themselves socially inhibited, indecisive, self-sacrificing, or accommodating. The study conducted by Salarrad et al. showed significant differences in anxiety levels and quality of life among the participants. These differences were observed both within individuals and between different subjects. EFT helped reduce anxiety and improve the quality of life in the people who received treatment, compared to the people who did not receive treatment (Salarrad et al., 2022). Additionally, the levels of anxiety and quality of life after the test and during the follow-up were different compared to the levels before the test, but they were not different from each other. In emotion-oriented therapy, self-critical processes happen when a part of you, called the critical self, judges and blames another part of you, called the experience. This issue can include judging your behavior, how you look, your personality traits, and the things you’ve gone through. This process involves a stronger part taking control over a weaker part to reach a specific goal, like avoiding errors or becoming perfect, and reducing harm to one’s reputation (Gilbert et al., 2004).

People with social anxiety have a voice inside their heads that makes them think things are going wrong in social situations. They fear being rejected or having their weaknesses exposed. During the therapy and the two-chair dialogue process, this catastrophizing voice turns into a critical or shaming voice that makes one feel worthless and ashamed. Once shame is called up, through exposure to new information that integrates with autobiographical memory, it is reorganized or transformed into adaptive emotions, such as protective anger, developmental sadness, or self-pity (Shahar, 2014). Study results of Haberman et al., 2019, showed a significant decrease in shame levels and a slight increase in asserted anger levels during treatment. Adaptive sadness/grief during a given session predicted less fear of negative evaluation in the following week. Shame during a given session predicted higher levels of self-inadequacy in the following week. Finally, shame and, to a lesser extent, expressed anger, during a given session predicted self-comfort during the following week. Neither anger nor adaptive sadness/grief in a given session was demonstrated to predict levels of self-criticism in the following week (Haberman et al., 2019).

According to the results, the unified trans-diagnostic treatment was successful in decreasing the anxiety of positive assessment in the intervention group; though, it had no significant impact on reducing the fear of negative appraisal in this group. No research is available to investigate how effective the unified trans-diagnostic treatment is in addressing the levels of both fear of positive evaluation and fear of negative evaluation. Therefore, this result is consistent with previous studies, for example, de Ornelas Maia et al. (2015), Klemanski et al. (2017), and Roushani et al. (2016). In the study conducted by Roushani et al. (2016) it was found that a unified trans-diagnostic treatment approach reduced social anxiety and negative affect. Furthermore, the study results of de Ornelas Maia et al. (2015) indicated that compared to pharmacotherapy, trans-diagnostic treatment is more effective in treating anxiety and depressive disorders. Bullis et al. (2014) examined the durability of the effects of trans-diagnostic intervention on emotional disorders. Based on the logic of trans-diagnostic treatment of emotional disorders, they are disorders characterized by intense and repeated negative emotions, very strong reactions to emotions (Bullis et al. 2014), low distress tolerance, high negative affect, high emotional avoidance (Sherman & Ehrenreich-May, 2020). Especially in people with social anxiety disorder, impaired emotional understanding, higher emotional suppression, difficulty in managing negative emotions, and less self-confidence in the ability to manage emotions are observed (Sackl-Pammer et al., 2019). Contemporary models of social anxiety disorder assume that people use repetitive negative cognitive processes, such as rumination and anticipatory worry, to repeat safety behaviors and increase the feeling of readiness to face situations (Klemanski et al., 2017).

Therefore, it is debatable whether to decrease the fear score of positive evaluation in people in the trans-diagnostic treatment group due to the reduction of worry and negative rumination, which are significant meta-diagnostic components of social anxiety and mechanisms of emotional avoidance in these people. Therefore, people gained more ability to experience their negative emotions (Klemanski et al., 2017). One limitation of this research is the limited number of people in each group, which makes it difficult to generalize the results. Also, another limitation of this research is the use of measurements based on self-report scales, treatment implementation, and evaluations related to the intervention by the therapist. Further investigation and empirical research aimed at surmounting the specified limitations may unveil novel insights and consequently establish a more robust foundation for the mentioned therapeutic interventions among the Iranian populace.

5. Conclusion

According to the results, incorporating trans-diagnostic therapy was not successful in diminishing individuals’ anxiety toward negative evaluations. It may be inferred that the core element of this disorder is possibly the fear of unfavorable judgment, rooted in an underlying sense of shame. One way to enhance the efficacy of meta-diagnostic therapy is to prioritize and tackle the fear of negative evaluation, which is a key element.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Committee of Gilan University approved the research venture (Code: IR.GUILAN.REC.1401.012).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The participants of this study are greatly appreciated for their valuable contributions.

References

Arshadi, N., Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., & Fakhri, A. (2018). The effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic treatment on brain-behavioral systems and anxiety sensitivity in female students with social anxiety symptoms. International Journal of Psychology (IPA), 12(2), 46-72. [Link]

Bandelow, B. (2020). Current and novel psychopharmacological drugs for anxiety disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1191, 347–365. [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Bullis, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., Murray-Latin, H., & Sauer-Zavala, S., et al. (2017). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875-884. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164] [PMID] [PMCID]

Bullis, J. R., Fortune, M. R., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). A preliminary investigation of the long-term outcome of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(8), 1920-1927. [PMID]

Butler, R. M., Boden, M. T., Olino, T. M., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J., et al. (2018). Emotional clarity and attention to emotions in cognitive behavioral group therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 31-38. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

Deer, T., Pope, J., Benyamin, R., Vallejo, R., Friedman, A., & Caraway, D., et al. (2016). Prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, partial crossover study to assess the safety and efficacy of the novel neuromodulation system in the treatment of patients with chronic pain of peripheral nerve origin. Neuromodulation: Journal of The International Neuromodulation Society, 19(1), 91–100. [PMID]

de Ornelas Maia, A. C., Nardi, A. E., & Cardoso, A. (2015). The utilization of unified protocols in behavioral cognitive therapy in transdiagnostic group subjects: A clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 179-183. [PMID]

Elliott, R., & Shahar, B. (2017). Emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety (EFT-SA). Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 16(2), 140-158. [Link]

García-Escalera, J., Valiente, R. M., Chorot, P., Ehrenreich-May, J., Kennedy, S. M., & Sandín, B. (2017). The Spanish version of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents (UP-A) adapted as a school-based anxiety and depression prevention program: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 6(8), e149. [PMID]

Ghaderi, F., Akrami, N., Namdari, K., & Abedi, A. (2023). Investigating the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on maladaptive personality traits and mentalized affectivity of patients with generalized anxiety disorder comorbid with depression: A case study. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 11(2), 117-130. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.2.862.1]

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(Pt 1), 31–50. [DOI:10.1348/014466504772812959] [PMID]

Goldin, P. R., Morrison, A., Jazaieri, H., Brozovich, F., Heimberg, R., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 427-437. [DOI:10.1037/ccp0000092] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goodman, F. R., Kelso, K. C., Wiernik, B. M., & Kashdan, T. B. (2021). Social comparisons and social anxiety in daily life: An experience-sampling approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(5), 468-489. [DOI:10.1037/abn0000671] [PMID] [PMCID]

Haberman, A., Shahar, B., Bar-Kalifa, E., Zilcha-Mano, S., & Diamond, G. M. (2019). Exploring the process of change in emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 908–918. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2018.1426896]

Hedman, E., Ström, P., Stünkel, A., & Mörtberg, E. (2013). Shame and guilt in social anxiety disorder: Effects of cognitive behavior therapy and association with social anxiety and depressive symptoms. PloS One, 8(4), e61713. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0061713] [PMID] [PMCID]

Heinonen, E. & Pos, A. E. (2020) The role of pre-treatment interpersonal problems for in-session emotional processing and long-term outcome in emotion-focused psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. [DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2019.163077]

Jefferies, P., & Ungar, M. (2020). Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PloS One, 15(9), e0239133. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0239133] [PMID] [PMCID]

Klemanski, D. H., Curtiss, J., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2017). Emotion regulation and the transdiagnostic role of repetitive negative thinking in adolescents with social anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 206–219. [PMID]

Laposa, J. M., Mancuso, E., Abraham, G., & Loli-Dano, L. (2017). Unified protocol transdiagnostic treatment in group format. Behavior Modification, 41(2), 253-268. [DOI:10.1177/0145445516667664] [PMID]

Lee, S. W., & Kwon, J. H. (2013). The efficacy of imagery rescripting (IR) for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(4), 351-360. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.03.001] [PMID]

Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., Delgado, B., Inglés, C. J., & Escortell, R. (2020). Cyberbullying and social anxiety: A latent class analysis among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 406. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17020406] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martin P. (2003). The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: A review. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 5(3), 281–298. [PMID]

Newman, M. G., Rackoff, G. N., Zhu, Y., & Kim, H. (2023). A transdiagnostic evaluation of contrast avoidance across generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102662. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102662] [PMID]

Okawa, S., Arai, H., Sasagawa, S., Ishikawa, S. I., Norberg, M. M., & Schmidt, N. B., et al. (2021). A cross-cultural comparison of the bivalent fear of evaluation model for social anxiety. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 31(3), 205-213. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbct.2021.01.003]

Pittelkow, M. M., Aan Het Rot, M., Seidel, L. J., Feyel, N., & Roest, A. M. (2021). Social Anxiety and Empathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102357. [10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102357] [PMID]

Reichenberger, J., Wiggert, N., Wilhelm, F. H., Liedlgruber, M., Voderholzer, U., & Hillert, A., et al. (2019). Fear of negative and positive evaluation and reactivity to social-evaluative videos in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 140-148. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.009] [PMID]

Roushani, K., Nejad, S. B., Arshadi, N., Honarmand, M. M., & Fakhri, A. (2016). Examining the efficacy of the unified transdiagnostic treatment on social anxiety and positive and negative affect in students. Razavi International Journal of Medicine, 4(4), e41233. [Link]

Sackl-Pammer, P., Jahn, R., Özlü-Erkilic, Z., Pollak, E., Ohmann, S., & Schwarzenberg, J., et al. (2019). Social anxiety disorder and emotion regulation problems in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13, 37. [PMID]

Shahar, B. (2014). Emotion-focused therapy for the treatment of social anxiety: An overview of the model and a case description. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(6), 536-547. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.1853] [PMID]

Salarrad, Z., Leilabadi, L., Nafissi, N., & Kraskian Mujembari, A. (2022). [Effectiveness of emotion-focused therapy on anxiety and quality of life in women with breast cancer (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Health Psychology, 5(3), 35-46. [DOI:10.30473/ijohp.2022.60436.1205]

Sherman, J. A., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2020). Changes in risk factors during the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 51(6), 869-881. [PMID]

Yap, K., Gibbs, A. L., Francis, A. J., & Schuster, S. E. (2016). Testing the bivalent fear of evaluation model of social anxiety: The relationship between fear of positive evaluation, social anxiety, and perfectionism. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(2), 136-149. [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2015.1125941] [PMID]

Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2008). The Fear of Positive Evaluation Scale: Assessing a proposed cognitive component of social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(1), 44–55. [PMID]

Anxiety means being scared or worried about what may happen in the future (Hamm, 2020). Research studies have found that anxiety disorders are very common and can significantly impact a person’s ability to function normally. They are the most common mental disorders in our society (Martin, 2003). According to large population-based surveys, up to 33.7% of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime (Bandelow & Michaelis, 2022). The disorder begins at an early stage of development and often precedes the onset of other conditions, such as anxiety disorders, alcohol misuse, and major depression (Goldin et al., 2016). Social anxiety has a great impact on diminishing performance in several areas of life and reducing happiness and health (Goodman et al., 2021). Individuals with social anxiety are more at risk of being bullied and have a higher chance of leaving school early with insufficient accomplishments (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020). Having this condition regularly leads to a decreased number of acquaintances, a decreased likelihood of getting married, an increased chance of divorce, and a reduced probability of becoming a parent. According to reports, individuals experience more days absent from work and decreased performance at work (Jefferies & Ungar, 2020).

As Pittelkow et al. stated, the persistent symptoms of this disorder often become chronic and show no signs of improvement without proper treatment (Pitelkow et al., 2021). According to the research conducted by Butler et al., individuals facing this condition undergo significant disruptions in their personal, professional, educational, and emotional bonds, along with a decline in their standard of living (Butler et al., 2018). Anxiety disorder in social situations is commonly diagnosed via the primary symptom of the fear of negative evaluations, which is widely accepted in the theoretical models of this condition (Reichenberger et al., 2019). Lee and Kwon describe the fear of negative evaluation as a complex construct that involves not only apprehension and concern over how others will judge us but also the anxiety caused by such assessments and the belief that others will only perceive us in a negative light (Lee & Kwon, 2013). According to Okawa et al. (2012) when individuals receive negative criticism, they may develop the impression that others have a negative view of them, which can cause rejection.

Weeks et al., (2008) introduced the two-way paradigm of anxiety regarding evaluation to illustrate the relationship between apprehension toward receiving positive feedback and uncertainty in social environments. The proposed theory suggests that individuals with social anxiety are highly receptive to both negative and positive feedback from their peers, which they perceive as potential social risks (Yap et al., 2016). The fear of positive evaluation is the fear associated with positive judgment and compared to others, which can lead to exposure and vulnerability. This fear is often experienced by individuals with a social anxiety disorder who worry that positive evaluations of future social standards that they will fail to meet will increase, ultimately strengthening their fear of negative evaluation (Reichenberger et al., 2019).

Due to the wide prevalence and early manifestation of this condition, along with the limited likelihood of spontaneous improvement without psychological intervention, prompt identification and implementation of effective treatment are crucial. The emotion-focused treatment model states that individuals with social anxiety disorder experience anxiety due to feeling ashamed. This anxiety is a secondary emotional reaction. The theory proposes that people who have endured challenges in childhood, such as harsh criticism or bullying, develop a mental pattern rooted in shame. This issue can cause a perpetual sense of incompleteness and fragility, as well as an aversion to being judged negatively or rejected by society. The individual may be especially sensitive to feelings of shame in social interactions (Elliott & Shahar, 2017). Numerous studies have found strong evidence that people who are bullied online have a lot of anxiety in social situations (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020; Jefferies & Ungar, 2020). Expecting to experience shame can cause people to feel anxious and avoid social gatherings. As a result, they may struggle to address the root of their shame and unintentionally amplify their anxiety levels (Hedman et al., 2013). Elliott and Shahar presented the emotion-focused therapy (EFT) theory of social anxiety and described its developmental origins in the experience of social deterioration, leading to underlying emotional processes being organized around a self that feels flawed and consumed by shame. These create secondary reactive anxiety that others will see the person’s flaws, organized around the coach/critic/guardian aspect of the self, when trying to protect the person from exposure, unintentionally creating the emotional dysregulation characteristic of social anxiety (Elliott & Shahar, 2017). According to Haberman et al., people witness therapeutic change when faced with shame rather than avoidance. Shame can be altered or changed by activating beneficial emotions, such as strong and courageous anger, as well as sadness linked to a need for deeper relationships and self-compassion, which had been suppressed (Haberman et al., 2019).

Moreover, a novel treatment is available that addresses the primary ailment along with any concurrent anxiety or depression disorders by simultaneously managing common symptoms and fundamental psychological procedures. This approach is called the unified trans-diagnostic treatment (Deer et al., 2016). The unified protocol for the trans-diagnostic treatment is an emotion-based cognitive-behavioral intervention that comprises five fundamental components that target identity characteristics, particularly neuroticism, and as a result, superstructure emotional dysregulation of all anxiety disorders, depression, and related disorders. By tending to the usual mechanisms related to neuroticism, particularly negative appraisal, and avoidance of emotional experience, this approach can rearrange instructive endeavors and address concerns related to its generalizability to usual care sets for comorbid emotional disorders (Barlow et al., 2017). Transdiagnostic treatment helps students feel less anxious, worried, and depressed. It also reduces anxiety and panic. Additionally, it helps increase positive feelings for students experiencing social anxiety symptoms (Laposa et al., 2017; García-Escalera et al., 2017; Arshadi et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2023; Ghaderi et al., 2023).

Limited research has targeted emotion regulation as a central component in the treatment of this disorder. Furthermore, as social creatures, humankind must possess adaptable skills in society to ensure their survival. Psychologists have constantly sought methods to enhance human social interactions. Social anxiety disorder can disturb an individual’s connections with others and suggest a threat to their routine existence. Thus, employing therapies that focus on pinpointing the particular contributing factors of this condition and subsequently aiming to develop meaningful intervention approaches can enhance the social engagement of individuals affected by it. From previous remarks, the techniques emphasizing emotion regulation may be useful in lessening symptoms associated with social anxiety. Novel research exploring the efficacy of trans-diagnostic therapy as an alternative treatment method to manage emotional regulation has not been independently conducted in individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder in international studies.

In this context, it should be mentioned that most studies on anxiety disorder and the trans-diagnostic approach, whether in the population or clinical sub-samples, have been conducted in very few numbers with the Iranian population. Given the significance of recent research regarding emotion regulation as a crucial factor in this disorder, this study is the first to examine and contrast the efficacy of two treatments targeted at promoting emotion regulation among affected individuals. The study was conducted to compare the efficacy of EFT and the unified trans-diagnostic treatment for individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test-post-test control group design and a three-month follow-up. The statistical population of the study included all people aged 18-40 years who were referred to the Vian Clinic and all the people who were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder through the calls announced in the virtual space from September to March 2021 in Tehran City. A total of 21 patients were selected using purposive sampling and assigned to three groups (two experimental groups and one control group (7 patients in each group). The authors randomly selected people from each group by flipping a coin. To make a random decision, people usually throw a coin into the air and see which side lands facing up. We selected the experimental group by flipping a coin for each person. The people who landed on heads were chosen into the control group (Table 1 and Table 2). The participants were selected via purposive sampling considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research.

Inclusion criteria

Obtaining a cut-off score in the social phobia questionnaire and confirming the diagnosis of the disorder based on the diagnostic clinical interview according to the structured clinical interview for DSM-5® disorders-clinician version (SCID-5-CV), and at least having diploma education.

Exclusion criteria

The participant was affected by other psychotherapy and counseling programs related to the same or other psychological problems, taking psychoactive drugs or addictive substances, having personality disorders, psychosis, and bipolar disorder based on structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-V), and not attending over 3 treatment sessions.

Study procedure

After obtaining permission from the university and visiting the Vian Clinic and all the people who were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder through the calls announced in the virtual space from September to March 2021 in Tehran City (based on the research criteria), the people who were willing to participate in the research were referred to one of the psychology clinics (Vian Clinic) in Tehran City. After the people with social anxiety disorder went to Vian’s Clinical Psychology Center, they were accepted by the researcher (with a candidate PhD degree in psychology). At this stage, the participants were introduced to the aims, process, and consequences of the research. Then, after obtaining written consent from the individuals, a pre-test of psychological distress was performed among them.

The experimental groups 1 and 2 received EFT (Elliott & Shahar, 2017) in twenty 120-minute sessions (one session every week) and the unified trans-diagnostic treatment (Barlow et al., 2017) in twelve 120-minute sessions (one session every week), respectively, while the control group was placed on the treatment waiting list. After completing the training sessions, the experimental and control groups were tested in the same conditions, and three months later, the subjects were evaluated in the follow-up phase. All participants were evaluated at the pre-test and post-test stages using the research instruments.

After collecting a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), pre-test, post-test, and follow-up data were analyzed. One of the principles of ethical compliance is informed consent and non-violation of the rights of the participants in the research observance of human rights and confidentiality of their research results. Furthermore, after completing the training sessions on the educational groups and performing post-test and follow-up, the treatment sessions were administered intensively to observe the ethical principles of the control group. The following instruments were used to collect data:

The brief fear of negative evaluation scale (BFNE): The BFNE is a method to measure the anxiety level of a person feels when they think they are being judged or evaluated negatively. This scale has 12 questions that ask about thoughts that make you scared or worried. The person answering the questions rates how much each item represents them using a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Out of the twelve elements, eight of them are about being scared or worried, and the other four are about not being scared or worried. It was also clear that the fear of negative evaluation questionnaire has very reliable results (Cronbach’s α=0.9). The re-test method was used to check reliability for four weeks. It showed a correlation of 0.75. How the factors are organized is not clear. Some people think there is only one factor, while others, using a group of people with clinical conditions, have found that there are two factors. These factors consist of statements that are either positive or negative. In simple words, this means that when comparing this scale to other questionnaires about social phobia and social interaction anxiety in Iranian society, the results showed that the scale was reliable and accurate. The convergent validity for the social phobia questionnaire was 0.43, and for the social interaction anxiety scale, it was 0.54.

The fear of positive evaluation scale (FPES)

The FPES is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess this construct (Weeks et al., 2008). The FPES consists of 10 statements that are graded on a scale from zero (not true at all) to 9 (completely true). In their study on a sample of 1 711 undergraduate students, Weeks et al. reported a Mean±SD total score of 2.36±13.07 for this version. Also, the internal consistency with Cronbach’s α method is 0.80 and the five-week re-test reliability is 0.70. In Iranian society, the reliability coefficient was calculated as 0.67 by the two-half method and Cronbach’s α as 0.75 for the whole test.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24 using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of the data. Using Leven’s test, researchers sought to ascertain if the variances showed homogeneity. In this study, repeated measures ANOVA was used.

3. Results

The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate no significant variations between the three groups in terms of demographic variables, including age (ANOVA), and marital status (chi-square test). The three groups can be considered homogeneous due to the presence of the desired variables

To meet the statistical assumption of normality, the results of the Shapiro-wilk test were non-significance (P>0.05). In other words, the assumption of normality was confirmed. Also, the results in Table 4 showed that the normal of the three groups (two test groups and one control group) have differences within the pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up.

As Table 5, the relationship between different stages and groups affecting fear of negative evaluation is significant (η2=0.909, F=56.614, P<0.05). This means that a significant difference is observed between the group that did the experiment and the group that did not experiment in terms the fear of negative judgment, in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05).

Also, the results of a simple mixed ANOVA test showed that the main effect of the within-group factor on fear of negative evaluation (η2=0.381, F=180.388) is significant (P<0.05). Regardless of the group they belong to, the results indicated that everyone’s apprehension improved negative evaluation.

In the continuation of the results, the main effect of the between-group factor on the fear of negative evaluation (η2=0.506, F=9.22) is significant (P<0.05). Consequently, the results indicated that different groups show varying degrees of fear towards negative judgments. (P<0.05).

As the results in Table 5 show, the interaction effect of steps and group on the fear of positive evaluation (η2=0.574, F=12.134) is significant (P<0.05). This shows that the experimental group and control group had different levels of fear of positive evaluation during the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05).

The results of the simple mixed ANOVA test also indicated that the main effect of the within-group factor on academic performance (η2=0.778, F=63.241) is significant (P<0.05). Over time, this study discovered that people’s fear of praise or positive evaluation fluctuated up and down, independent of the group.

The results of the main effect of the between-group factor on the fear of positive evaluation (η2=0.557, F=11.329) are significant (P<0.05). Therefore, the results showed a difference between the studied groups in terms of fear of positive evaluation (P<0.05).

The results in Table 6 showed a significant difference between the post-test and follow-up periods in terms of people’s fear of negative evaluation; thus, the mean level of fear of negative evaluation scores in the post-test phase compared to the pre-test phase was significantly reduced, and this decrease continued until the next phase. The results in Table 6 showed a significant difference in people’s mean scores between the post-test and follow-up periods due to fear of positive evaluation; therefore, the mean fear of positive evaluation score at the post-test decreased significantly compared to the pre-test, and this decrease continued until the follow-up period.

The results in Table 7 showed that the mean difference between the two groups of EFT and unified trans-diagnostic treatment was significantly different. However, the mean difference between the control treatment group and the trans-diagnostic treatment group was not significant. Thus, metabolic diagnostic treatments were unsuccessful in reducing the fear of negative evaluation of the target sample. Furthermore, the results in Table 7 showed the significant effectiveness of both treatments in reducing fear of positive evaluation scores in the sample group. Furthermore, the results showed no significant difference between the effectiveness of EFT and the unified protocol for cross-cutting diagnostic treatment in reducing fear scores on positive evaluation.

4. Discussion

The study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of EFT and trans-diagnostic treatment in reducing the fear of negative and positive evaluations in people with a social anxiety disorder. According to the study, EFT had a significant impact on lowering the fear of negative evaluation in the experimental group compared to the control group. In contrast, trans-diagnostic treatment was not effective in curbing this fear in the experimental group. The current study’s results are consistent with Shahar et al.’s research on the effectiveness of EFT in decreasing the fear of negative evaluation. Individuals with social anxiety disorder experience feelings of fear and tend to switch their attention to their internal state and their anxious reactions when they are exposed to frightening social situations. Due to increased self-awareness and critical insight, individuals form a distorted impression of themselves and further believe that others perceive them similarly, ultimately resulting in a negative self-evaluation (Lee & Kwon, 2013).

As mentioned earlier, self-criticism is a common trait among people with social anxiety. Additionally, Heinonen and Pos showed that all pre-treatment interpersonal problems were clearly associated with patients’ negative self-evaluations during therapy (Heinonen & Pos, 2020). According to the complex model, the personal experience of revenge was more associated with the emotional expressions of anger denial during the session and the personal experience of social inhibition to express fear and shame. In minimizing long-term interpersonal problems, reaching a state of emotional distress and grief in particular appears to benefit patients who consider themselves socially inhibited, indecisive, self-sacrificing, or accommodating. The study conducted by Salarrad et al. showed significant differences in anxiety levels and quality of life among the participants. These differences were observed both within individuals and between different subjects. EFT helped reduce anxiety and improve the quality of life in the people who received treatment, compared to the people who did not receive treatment (Salarrad et al., 2022). Additionally, the levels of anxiety and quality of life after the test and during the follow-up were different compared to the levels before the test, but they were not different from each other. In emotion-oriented therapy, self-critical processes happen when a part of you, called the critical self, judges and blames another part of you, called the experience. This issue can include judging your behavior, how you look, your personality traits, and the things you’ve gone through. This process involves a stronger part taking control over a weaker part to reach a specific goal, like avoiding errors or becoming perfect, and reducing harm to one’s reputation (Gilbert et al., 2004).

People with social anxiety have a voice inside their heads that makes them think things are going wrong in social situations. They fear being rejected or having their weaknesses exposed. During the therapy and the two-chair dialogue process, this catastrophizing voice turns into a critical or shaming voice that makes one feel worthless and ashamed. Once shame is called up, through exposure to new information that integrates with autobiographical memory, it is reorganized or transformed into adaptive emotions, such as protective anger, developmental sadness, or self-pity (Shahar, 2014). Study results of Haberman et al., 2019, showed a significant decrease in shame levels and a slight increase in asserted anger levels during treatment. Adaptive sadness/grief during a given session predicted less fear of negative evaluation in the following week. Shame during a given session predicted higher levels of self-inadequacy in the following week. Finally, shame and, to a lesser extent, expressed anger, during a given session predicted self-comfort during the following week. Neither anger nor adaptive sadness/grief in a given session was demonstrated to predict levels of self-criticism in the following week (Haberman et al., 2019).

According to the results, the unified trans-diagnostic treatment was successful in decreasing the anxiety of positive assessment in the intervention group; though, it had no significant impact on reducing the fear of negative appraisal in this group. No research is available to investigate how effective the unified trans-diagnostic treatment is in addressing the levels of both fear of positive evaluation and fear of negative evaluation. Therefore, this result is consistent with previous studies, for example, de Ornelas Maia et al. (2015), Klemanski et al. (2017), and Roushani et al. (2016). In the study conducted by Roushani et al. (2016) it was found that a unified trans-diagnostic treatment approach reduced social anxiety and negative affect. Furthermore, the study results of de Ornelas Maia et al. (2015) indicated that compared to pharmacotherapy, trans-diagnostic treatment is more effective in treating anxiety and depressive disorders. Bullis et al. (2014) examined the durability of the effects of trans-diagnostic intervention on emotional disorders. Based on the logic of trans-diagnostic treatment of emotional disorders, they are disorders characterized by intense and repeated negative emotions, very strong reactions to emotions (Bullis et al. 2014), low distress tolerance, high negative affect, high emotional avoidance (Sherman & Ehrenreich-May, 2020). Especially in people with social anxiety disorder, impaired emotional understanding, higher emotional suppression, difficulty in managing negative emotions, and less self-confidence in the ability to manage emotions are observed (Sackl-Pammer et al., 2019). Contemporary models of social anxiety disorder assume that people use repetitive negative cognitive processes, such as rumination and anticipatory worry, to repeat safety behaviors and increase the feeling of readiness to face situations (Klemanski et al., 2017).

Therefore, it is debatable whether to decrease the fear score of positive evaluation in people in the trans-diagnostic treatment group due to the reduction of worry and negative rumination, which are significant meta-diagnostic components of social anxiety and mechanisms of emotional avoidance in these people. Therefore, people gained more ability to experience their negative emotions (Klemanski et al., 2017). One limitation of this research is the limited number of people in each group, which makes it difficult to generalize the results. Also, another limitation of this research is the use of measurements based on self-report scales, treatment implementation, and evaluations related to the intervention by the therapist. Further investigation and empirical research aimed at surmounting the specified limitations may unveil novel insights and consequently establish a more robust foundation for the mentioned therapeutic interventions among the Iranian populace.

5. Conclusion

According to the results, incorporating trans-diagnostic therapy was not successful in diminishing individuals’ anxiety toward negative evaluations. It may be inferred that the core element of this disorder is possibly the fear of unfavorable judgment, rooted in an underlying sense of shame. One way to enhance the efficacy of meta-diagnostic therapy is to prioritize and tackle the fear of negative evaluation, which is a key element.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Committee of Gilan University approved the research venture (Code: IR.GUILAN.REC.1401.012).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The participants of this study are greatly appreciated for their valuable contributions.

References

Arshadi, N., Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M., & Fakhri, A. (2018). The effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic treatment on brain-behavioral systems and anxiety sensitivity in female students with social anxiety symptoms. International Journal of Psychology (IPA), 12(2), 46-72. [Link]

Bandelow, B. (2020). Current and novel psychopharmacological drugs for anxiety disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1191, 347–365. [PMID]

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Bullis, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., Murray-Latin, H., & Sauer-Zavala, S., et al. (2017). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875-884. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164] [PMID] [PMCID]

Bullis, J. R., Fortune, M. R., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). A preliminary investigation of the long-term outcome of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(8), 1920-1927. [PMID]

Butler, R. M., Boden, M. T., Olino, T. M., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J., et al. (2018). Emotional clarity and attention to emotions in cognitive behavioral group therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 31-38. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

Deer, T., Pope, J., Benyamin, R., Vallejo, R., Friedman, A., & Caraway, D., et al. (2016). Prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, partial crossover study to assess the safety and efficacy of the novel neuromodulation system in the treatment of patients with chronic pain of peripheral nerve origin. Neuromodulation: Journal of The International Neuromodulation Society, 19(1), 91–100. [PMID]

de Ornelas Maia, A. C., Nardi, A. E., & Cardoso, A. (2015). The utilization of unified protocols in behavioral cognitive therapy in transdiagnostic group subjects: A clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 179-183. [PMID]

Elliott, R., & Shahar, B. (2017). Emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety (EFT-SA). Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 16(2), 140-158. [Link]

García-Escalera, J., Valiente, R. M., Chorot, P., Ehrenreich-May, J., Kennedy, S. M., & Sandín, B. (2017). The Spanish version of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents (UP-A) adapted as a school-based anxiety and depression prevention program: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 6(8), e149. [PMID]

Ghaderi, F., Akrami, N., Namdari, K., & Abedi, A. (2023). Investigating the effectiveness of transdiagnostic treatment on maladaptive personality traits and mentalized affectivity of patients with generalized anxiety disorder comorbid with depression: A case study. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 11(2), 117-130. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.2.862.1]

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(Pt 1), 31–50. [DOI:10.1348/014466504772812959] [PMID]

Goldin, P. R., Morrison, A., Jazaieri, H., Brozovich, F., Heimberg, R., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 427-437. [DOI:10.1037/ccp0000092] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goodman, F. R., Kelso, K. C., Wiernik, B. M., & Kashdan, T. B. (2021). Social comparisons and social anxiety in daily life: An experience-sampling approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(5), 468-489. [DOI:10.1037/abn0000671] [PMID] [PMCID]

Haberman, A., Shahar, B., Bar-Kalifa, E., Zilcha-Mano, S., & Diamond, G. M. (2019). Exploring the process of change in emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 908–918. [DOI:10.1080/10503307.2018.1426896]

Hedman, E., Ström, P., Stünkel, A., & Mörtberg, E. (2013). Shame and guilt in social anxiety disorder: Effects of cognitive behavior therapy and association with social anxiety and depressive symptoms. PloS One, 8(4), e61713. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0061713] [PMID] [PMCID]

Heinonen, E. & Pos, A. E. (2020) The role of pre-treatment interpersonal problems for in-session emotional processing and long-term outcome in emotion-focused psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. [DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2019.163077]

Jefferies, P., & Ungar, M. (2020). Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PloS One, 15(9), e0239133. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0239133] [PMID] [PMCID]

Klemanski, D. H., Curtiss, J., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2017). Emotion regulation and the transdiagnostic role of repetitive negative thinking in adolescents with social anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 206–219. [PMID]

Laposa, J. M., Mancuso, E., Abraham, G., & Loli-Dano, L. (2017). Unified protocol transdiagnostic treatment in group format. Behavior Modification, 41(2), 253-268. [DOI:10.1177/0145445516667664] [PMID]

Lee, S. W., & Kwon, J. H. (2013). The efficacy of imagery rescripting (IR) for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(4), 351-360. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.03.001] [PMID]

Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., Delgado, B., Inglés, C. J., & Escortell, R. (2020). Cyberbullying and social anxiety: A latent class analysis among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 406. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17020406] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martin P. (2003). The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: A review. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 5(3), 281–298. [PMID]

Newman, M. G., Rackoff, G. N., Zhu, Y., & Kim, H. (2023). A transdiagnostic evaluation of contrast avoidance across generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102662. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102662] [PMID]

Okawa, S., Arai, H., Sasagawa, S., Ishikawa, S. I., Norberg, M. M., & Schmidt, N. B., et al. (2021). A cross-cultural comparison of the bivalent fear of evaluation model for social anxiety. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 31(3), 205-213. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbct.2021.01.003]

Pittelkow, M. M., Aan Het Rot, M., Seidel, L. J., Feyel, N., & Roest, A. M. (2021). Social Anxiety and Empathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102357. [10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102357] [PMID]

Reichenberger, J., Wiggert, N., Wilhelm, F. H., Liedlgruber, M., Voderholzer, U., & Hillert, A., et al. (2019). Fear of negative and positive evaluation and reactivity to social-evaluative videos in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 140-148. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.009] [PMID]

Roushani, K., Nejad, S. B., Arshadi, N., Honarmand, M. M., & Fakhri, A. (2016). Examining the efficacy of the unified transdiagnostic treatment on social anxiety and positive and negative affect in students. Razavi International Journal of Medicine, 4(4), e41233. [Link]

Sackl-Pammer, P., Jahn, R., Özlü-Erkilic, Z., Pollak, E., Ohmann, S., & Schwarzenberg, J., et al. (2019). Social anxiety disorder and emotion regulation problems in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13, 37. [PMID]

Shahar, B. (2014). Emotion-focused therapy for the treatment of social anxiety: An overview of the model and a case description. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(6), 536-547. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.1853] [PMID]

Salarrad, Z., Leilabadi, L., Nafissi, N., & Kraskian Mujembari, A. (2022). [Effectiveness of emotion-focused therapy on anxiety and quality of life in women with breast cancer (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Health Psychology, 5(3), 35-46. [DOI:10.30473/ijohp.2022.60436.1205]

Sherman, J. A., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2020). Changes in risk factors during the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 51(6), 869-881. [PMID]

Yap, K., Gibbs, A. L., Francis, A. J., & Schuster, S. E. (2016). Testing the bivalent fear of evaluation model of social anxiety: The relationship between fear of positive evaluation, social anxiety, and perfectionism. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(2), 136-149. [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2015.1125941] [PMID]

Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2008). The Fear of Positive Evaluation Scale: Assessing a proposed cognitive component of social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(1), 44–55. [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Cognitive behavioral

Received: 2023/06/5 | Accepted: 2023/07/18 | Published: 2023/10/28

Received: 2023/06/5 | Accepted: 2023/07/18 | Published: 2023/10/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |