Volume 10, Issue 2 (Spring 2022)

PCP 2022, 10(2): 91-110 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghamari Kivi H, Jamshiddoust Miyanroudi F. Tracking Sequences of Patient-Therapist Dialogues by Coding Responses During Integrative Psychotherapy. PCP 2022; 10 (2) :91-110

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-798-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-798-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. , h_ghamari@uma.ac.ir

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 690 kb]

(783 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3113 Views)

Full-Text: (689 Views)

1. Introduction

Psychotherapy is two-way communication between the therapist and the client; hence, every analysis must include responses from both sides. This is consistent with Stiles (1980) viewpoint that “to influence psychotherapeutic practice, the outcome research must address itself to the level at which therapeutic decisions are made—the moment-by-moment interchange between the client and the therapist.” However, current models investigate the responses of the therapist and the client differently and separately. There are at least five methods for analyzing the client’s behavior change stages based on different theoretical backgrounds. Assimilation of problematic experiences scale (APES) tracks problematic experiences across therapy sessions and describes a sequence of eight stages or levels of APES, from being dissociated or unwanted to being understood and integrated (Stiles, et al., 1992; Stiles et al., 1991; Stiles et al., 1990). The innovative moments coding system (IMCS) was introduced by Goncalves, Matos, and Santos (2009). This system includes five stages from action to performing the change. The narrative processes coding system has three distinct modes of inquiry, namely external, internal, and reflexive narrative modes (Angus, Levit and Hardtke, 1999). Ribeiro et al. (2013) introduced the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) which is based on Vygotsky (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). ZPD includes both the therapist’s intervention and the client’s responses (in five subgroups for the client) and exchange or two peaking turns.

Another comprehensive model for understanding the change process has emerged from the work of Prochaska, DiClemente, and their associates (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982, 1984, 2005; Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992). They derived an understanding of how people change (i.e., the processes) via the development of a transtheoretical model called the “Stages Of Change” (SOC) which outlines the five stages of change (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation for action, action, and maintenance). The SOC model suggests that people are not uniform in their understanding of problematic behaviors, their need for change, or their motivation to make a change.

The assimilation model offers an approach for customizing the therapeutic relationship through responsiveness (Stiles et al., 1990). This model conceptualizes the psychotherapy outcome as a change concerning particular problematic experiences, memories, wishes, feelings, attitudes, or behaviors that are threatening or painful or come from destructive relationships and traumatic incidents, rather than a change in the person as a whole. It suggests that in successful psychotherapy, clients follow a regular developmental sequence of recognizing, reformulating, understanding, and eventually resolving the problematic experiences that have brought them to treatment. Stiles et al. (1990) believed that a problematic experience is assimilated into a schema, a way of thinking, and acting that is developed or modified within the therapeutic relationship (accommodation) to assimilate the problematic experience. The assimilation model was adapted to a dialogical view by its introducers (such as Stiles, 1998). Meanwhile, the process of assimilation was described using the metaphor of voice (Honos-Webb & Stiles, 1998). This metaphor expresses the theoretical tenet that the traces of past experiences are active agents within people and are capable of communication. These traces can act and speak. Dissociated (unassimilated) voices tend to be problematic, whereas assimilated voices can act as resources. During a psychotherapy session with a client named John Jones, Stiles et al. (1992) found the assimilation model a useful rubric for conceptualizing John Jones’s evident progress in psychotherapy. In a case study, Meystre et al. (2014) showed how specific interventions by the therapist may facilitate assimilation. They also underlined the dialogical dimension of the therapy process. Caro Gabalda, Stiles, and Ruiz (2015) examined the therapist’s activities immediately preceding assimilation setbacks (a setback was defined as a decrease of one or more APES stages from one passage to the next, dealing with the same theme; for instance, from APES 4 to APES 3). Results showed that preceding setbacks to earlier assimilation stages where the problem was unformulated, the therapist was more often actively listening. Also, the setbacks were more often attributable to pushing a theme beyond the client’s working zone. Preceding setbacks to later assimilation stages where the problem was at least formulated, the therapist was more likely to be directing the client to consider alternatives, following the language therapy of the evaluation agenda. Meanwhile, the setbacks were more often attributable to the client following such directives, shifting attention to less assimilated (nevertheless formulated) aspects of the problem. As a result, the setbacks followed systematically different therapists’ activities depending on the problem stage of the assimilation.

Basto et al., (2016) showed changes in symptom intensity and emotion valence during the process of assimilation of a problematic experience. Ribeiro et al. (2016) revealed the APES and the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) drawn from a clinical trial of 16 sessions of Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT) for depression in two cases. This study supports the theoretical expectation that EFT therapists work mainly within their client’s Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development (TZPD). Therapeutic exchanges involving challenging interventions may foster client change if they occur in an overall climate of safety.

In one research, APES and the Innovative Moments (IMs) method were compared. Gonçalves et al. (2014) applied the methods to the transcripts of a successful case of linguistic therapy of evaluation independently in different research groups. The assimilation theory and the research suggested that higher APES scores reflect therapeutic gains with an approximate level of 4.0, separating the good from the poor outcome cases. The IMs model suggests that IMs classified as reconceptualization and performing change occur mainly in good outcome cases. This is while action, reflection, and protest occur in both good and poor outcome cases. Passages coded as reconceptualization and performing change were rare in this case; however, all were rated at or above APES 4.0. By contrast, 63% of the passages coded as action, reflection, or protest were rated below APES 4.0.

On the other side of the therapist-client communication analysis, there are the therapist’s responses. Unfortunately, little attention has been devoted to conceptualizing the therapist’s responses in the change process and few models describe and explain the background of change from this point of view. It is noteworthy that in analyzing the client’s behavior, William B. Stiles is the pioneer in classification and forming models of the therapist’s responses, although Verbal Response Modes (VRMs) entail both members of a dyad communication. Stiles (1992) wrote “both members of a dyad (e.g., the client as well as the therapist) can be the speakers in turn, and the taxonomy applies equally to both (Adopted from Stiles. 1992).

Ribeiro et al. (2013) presented another model for analyzing therapist-client communication. They revealed that the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) investigates each speaker’s turn and assesses whether and how therapists work within the client’s TZPD, defined as the space between the client’s actual therapeutic developmental level and their potential developmental level that could be reached in collaboration with the therapist.

There is a body of research in the realm of psychotherapy that has been directed only to the client’s responses and few have concentrated on the therapist’s responses. Indeed, the behavior changes that coincide between the client and the therapist or the sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses have been less analyzed. On the other hand, there are no studies regarding the implications of sequences within conversations. It seems that without analyzing the therapist’s responses within the conversational process of psychotherapy, understanding the concept of therapeutic change will be difficult. For example, Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) hypothesized that a patient is better able to reach a higher assimilation level if the therapist’s intervention is appropriate to the patient’s ongoing level.

Currently, there is no serious coding system for the therapist’s responses in the realm of psychotherapy. Hence, PFCA which has been reported by the first author of this article (2019 in Persian) as a coding system can be useful in clarifying the therapist’s responses. PFCA delineates the therapist’s understanding of the client and their efforts to open the conversational spaces to encourage a movement in the client’s constructions.

In this study, researchers have concentrated on coincident changes in responses of both the therapist and the client during psychotherapy to answer the following questions: which therapeutic intervention is optimally responsive at each APES level? And, how can the researcher delineate the responses of the therapist and the client on the change equation? In this study, researchers have combined APES (as a coding system of the client’s responses) and PFCA (as a coding system of the therapist’s responses) to clarify the sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses during psychotherapy. As a result, in PFCA the question is, under which therapist responses do higher levels of APES occur? Thus, as the main goal of the present research, the APES for coding the client’s responses and the PFCA for coding the therapist’s responses were applied to the transcripts of a successful case of integrative psychotherapy of depression to coincide with sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses.

2. Materials and Methods

The case of Mahnaz (a pseudonym)

The method for this research is a case study. The client was referred to Sepand Counseling Center in Ardabil City, Iran. The case was selected by an accessible method and entered into the research. Existence of a disorder, non-use of medication, and voluntary acceptance of counseling were the inclusion criteria of the study, and unwillingness to continue the counseling was one of the exclusion criteria. For following the ethical considerations, the authorities were assured that her name and initial details would be deleted and they would be confidential if the report was submitted and printed. Meanwhile, as the meetings were recorded, the authorities were assured that the voices would not be heard by anyone under any circumstances.

Mahnaz was a 55-year-old homemaker with a high school diploma. She showed symptoms of sadness, crying, poor attention, and sluggishness. She also manifested a lack of enjoyment of life, feelings of guilt, self-blame, and blaming others. Mahnaz had three daughters and her husband was a 65-year-old teacher. Her children were all married and had completed their higher education; one in Ardabil, one in Tehran, and one in the US. Mahnaz had 5 individual sessions from June to September 2019 and 4 sessions accompanied by her husband. The 5 individual sessions were recorded and the contents (150 dialogues between the therapist and the client) were transcribed by the researchers.

Instruments

Therapist

The therapy was conducted in Iran. The therapist (first author of this article) is a psychotherapist and a member of the Psychology and Counseling Organization of Iran; an academician with more than 30 years of experience as a therapist and supervisor.

Treatment

The therapist’s approach was integrative. This approach is influenced by and related to the intervention interview of Tomm, K. (1987). According to PFCA, in psychotherapy, change is a function of a series of linear and nonlinear questions, as well as several circular, reflective, and strategic questions, along with counseling skills such as paraphrasing or reframing and one or more theory-based techniques such as flooding (extracted from behavior therapy) and empty chair (extracted from Gestalt therapy). These are consistent with the opinions of Trijsburg et al. (2002) that clinical practice may be more eclectic or integrative than psychotherapeutic schools may presume. On the other hand, Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) revealed that therapeutic responsiveness can occur on time scales that range from months to milliseconds, from treatment assignment to subtle mid-intervention shifts.

The assimilation model provides a way to understand and track emerging client requirements which may then be used to suggest appropriate treatments, strategies, tactics, and intervention implementations. Therefore, an integrative approach in psychotherapy and counseling is one in which the therapist, with their immediacy and free-floating attention, can better pursue an appropriate therapeutic response as one that meets the client’s requirements at a given stage of assimilation and helps to shift the client’s assimilation of a given problematic experience from one stage to the next. To do so, the therapist has to follow an eclectic/integrative approach to work at its best.

Outcome measures

Four-dimensional Symptom Questionnaire

The Four-dimensional symptom questionnaire (4DSQ) is a self-report questionnaire that measures distress (16 items), depression (6 items), anxiety (12 items), and somatization (16 items) with separate scales (24). The items are answered on a 5-point frequency scale from “No” to “Very Often or Constantly”. To calculate the sum of scores, responses are coded on a 3-point scale: “No” (0 points); “Sometimes” (1 point); “Regularly”, “Often”, and “Very often or Constantly” (2 points). Reliability coefficients in the Cronbach’s α method for distress, depression, anxiety, and somatization subscales are 0.926, 0.909, 0.879, and 0.845, respectively. In the present study, the client completed 4DSQ in the pretest and posttest phases. Results of the 4DSQ in pretest and posttest phases are provided in Table 2. Table 2 demonstrates Mahnaz’s Pretest-posttest Scores on 4DSQ. This table indicates that scores in the posttest phase have changed after the treatment sessions.

.jpg)

Process measures

Assimilation of Problematic Experiences Scale

The APES scale was used to assess the levels of APES (Table 3).

.jpg)

APES (Stiles et al., 1991) includes eight stages, numbered from 0 to 7: 0) warded off/dissociated; 1) unwanted thoughts/active avoidance; 2) vague awareness/emergence; 3) problem statement/clarification; 4) understanding/insight; 5) application/working through; 6) resourcefulness/problem solution; 7) integration/mastery. The ratings of APES in the present study were based on Table 3.

Process focused conversation analysis

According to PFCA, if we accept the regression line as a basic model in predicting effective factors in a criterion variable, the equation of change, only based on the therapist’s verbal responses in psychotherapy sessions, is equal to:

Client change=some questions+some skills+some techniques

Thus, change in psychotherapy is a function of a series of linear and non-linear questions, as well as several circulars, reflective and strategic questions, and one or more counseling skills, for example, empathy or reframing, along with one or more theory-based techniques. Then, after transcribing the recorded contents, the therapist’s responses in one or more sessions such as questions, skills, and techniques, can be counted as the units of the study and entered into the table. Finally, specialists will write the change equation of each case in simple words or codes. Therefore, PFCA can be conceptualized as a method during psychotherapy for perceiving the therapist’s responses. In fact, this equation of change is highly consistent with the four hierarchical categories including treatment assignment, treatment strategies, treatment tactics, and moment-to-moment responsiveness that have been proposed by Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) on the therapist’s responses. Some questions and basic skills that are applied during PFCA are provided in Table 4 and Table 5, respectively.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Procedure

Phase 1: therapeutic sessions

As described earlier, Mahnaz participated in 5 individual therapeutic sessions and 4 sessions accompanied by her husband. Each session lasted for 45 minutes. The therapeutic approach was integrative and not only did the therapist not have any pre-planned approach, but they also had the client focused on therapeutic interview approaches which delineate the client’s changing requirements throughout psychotherapy.

Phase 2: Raters and judges

Raters were two counseling graduates who were trained by researchers during 5 two-hour sessions to code the client’s responses based on APES (Table 3). Furthermore, they were trained during 3 two-hour sessions to code the therapist’s responses based on the instructions in PFCA that are provided in Table 5 and Table 6.

.jpg)

Two judges, each with a PhD in clinical psychology independently justified the transcribed coding by the two counseling graduates. The minimum of Cohen’s kappa values was 70 and 72 in the coding of the client’s responses and the therapist’s responses, respectively.

Phase 3

In phase 3, the difference between pretest and posttest in 4DSQ was delineated.

Phase 4: Data analysis

Researchers combined the final coding sheets of the client’s responses in APES levels and coding sheets of the therapist’s responses in PFCA.

3. Results

After 5 sessions of psychotherapy in the case of Mahnaz, the recorded sessions were transcribed and the therapist’s responses were coded into three categories of questions, skills, and techniques. The frequency of each code for the client is provided in Table 7.

.jpg)

During the psychotherapy sessions, it was revealed that Mahnaz’s depression is secondary to two traumatizing events (problematic experiences): authoritarian parenting, and forced marriage. Thus, two central topics needed to be followed up by some questions, using some skills, and one or several techniques.

Session 1 (topic: authoritarian parenting)

There are some excerpts related to an authoritarian father in the following:

(Note: inside the parenthesis, there are the APES levels after the client’s response (C) and PFCA codes after the therapist’s response (T).)

C: I want to get better and lift my spirits and enjoy life. (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: OK. Well, let me ask you a few questions so that I can get an idea about your mental state. When did these problems start? (Linear question)

C: Maybe about twenty years ago, maybe even more. (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: Did it start after the event? (Linear question)

C: Yes. My father (40 seconds of crying). (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: Maybe what happened was so big and overwhelming that it really bothered you. (Empathy)

C: Doctor, it was much bigger than you know and more intense (pause for 1 minute). (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: I’d love to hear. (Facilitation)

C: When I was in high school, I was extremely clever. I was very good at my school lessons and in general, I was very studious. I always imagined myself studying an important and prestigious major at a university. I was so happy and engrossed in my dreams. But in my father’s eyes, it was all nonsense. By the way, I was the same teenager when I got married and my father accepted. When I heard it, it felt like I was falling from a high place. All my dreams were shattered. I decided to run away, but I didn’t know where to run and how to run. I said no. But no one was willing to listen to me. (Problem statement/clarification or level 3)

T: What was your mother’s opinion? (Linear question)

C: She had no influence and was just a person at home who just worked and listened. (Problem statement/clarification or level 3)

T: That means everything was in your father’s hands and he expected everyone to obey him. Do you mean like a dictator? (Interpretation)

C: Yes, a bad dictator. He never showed us any love and was so rigid. He was selfish and didn’t care for anyone. And I was imprisoned amidst my desires, hatred, fear, and this imposed life, and no one listened to my cry for help (1 minute). (Problem statement/clarification or level 3)

T: Let me conclude. I’ve realized that because of a premature and forced marriage you lost all your desire to continue your education, and because you had no other way to escape being captivated by family traditions, you accepted this imposed marriage. And during that time, you were unhappy with your situation and this was fueled by anger and hatred of your father and dissatisfaction with life in general. (Summarizing)

C: Yes, absolutely (crying for 2 minutes). (Problem statement/clarification or level 3)

T: I know it’s very hard to endure a life that has been imposed on you. And, you’ve been suffering for the last thirty years. (Empathy)

C: That’s right. (Problem statement/clarification or level 3)

T: My name for your current problem is depression. I think I can use the eye movement desensitization and reprocessing technique or EMDR on you. You can find information about it on the internet too. it is used for bad memories. I can use it on you. You write down your bad memories from the past up to the present; some of those that come to your mind and disturb you. In each session, I will use eye movement therapy on you. Every time that you describe a scene that reminds you of something, I will use eye movement therapy on you. The information has been stored in your mind, without being reviewed and processed to be reminded with a little cue as if it will happen now. If you, now, define every memory and I use the eye movement therapy to help you, the memory goes through the process again and the pressure and discomfort are lifted. You have to keep track of my finger movements in the same way without moving your head (role-playing consultant). What did you learn from this session? (Formulation/EMDR technique)

C: My past is full of events that have had a bad effect on me, and they are stored in my memory and the eye movement technique can eliminate those memories. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

Based on PFCA, the change equation of the above topic is provided below:

(Note: the number inside the parenthesis is representative of the client’s level of response based on APES)

Change equation=(2)+(Linear question)+(2)+(Linear question)+(2)+(Empathy)+(2)+(Facilitation)+(3)+(Linear question)+(3)+(Interpretation)+(3)+(Summarizing)+(3)+(Empathy)+(3)+(Formulation/EMDR technique)+(4)

At the starting point of the above excerpt, Mahnaz had a vague awareness/emergence level of APES (level 2). Then the process was followed by one linear question from the therapist and the sequences of dialogues continued.

This is the simplest form of demonstrating a patient-therapist dialogue sequence. At the starting point of the above excerpt, the level of the client was vague awareness/emergence (APES level 2); however, after two linear questions, one expression of empathy, and one facilitation by the therapist the level was raised to problem statement/clarification (APES level 3). Then, through linear questioning, summarizing, interpretation, empathy, formulation, and EMDR technique, it improved to understanding/insight (APES level 4). Although the client may temporarily experience stagnation within or between one or several sessions, it is a chain of questions, skills, and techniques based on the therapist’s responses that heal and help the client to move to a higher level of assimilation in the process of psychotherapy. Overall, whenever one topic, such as the authoritarian father, was resolved for Mahnaz, she was prepared to move toward other basic topics.

Session 3 (topic: forced marriage)

There are some excerpts related to forced marriage in the following sections:

T: What were your unfulfilled wishes? Ones that you struggled to accept? (Linear question)

C: Continuing my education, a stronger and smarter husband than myself, and talents that never blossomed. (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: I know it’s hard and difficult to remember these things. Your tears reflect this. (Empathy)

C: (Crying for 1:30 minutes). (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: But, were you able to handle it? (Circular question)

C: Very hard (crying for 30 seconds). (Vague awareness/emergence or level 2)

T: So, you have to work well so that you don’t have to put too much pressure on yourself. Can you tell me what you have achieved in these 37 years of living together? (Linear question)

C: My husband loves me, he liked me from the beginning, but there were so many downsides in my life. For example, the kids always bothered me, and my husband was not involved in school affairs, and ng clothes, and, so on. Even in things like banking and so on. The everyday house chores were always left to me. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

T: Did you accept them? Did you get on with them or were they imposed on you? (Clarification)

C: They were imposed on me because my husband was not interested in doing them. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

T: And you did, and that was your choice. May I say that you didn’t insist enough and your husband’s negligence was enough to make you get up and do the job yourself? (Interpretation)

C: Yes, it’s true. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

T: And so, you agreed in a way to become so versatile. Might I say that your husband was a bit lazy, and you made things worse by becoming overactive and carrying out some of his duties? (Circular question)

C: To a large extent, yes. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

T: Suppose you are telling him these things. Say them to that empty chair where your husband is sitting; tell him directly. (Empty chair technique)

C: (During the husband’s embodiment in the chair) you shunned your responsibility and I had to make up for that. I don’t mean you cheated on me but you were very careless and I shouldered the heavy burden of a man (crying for 30 seconds). (Understanding/insight or level 4)

T: Yeah, the housework and other chores and errands are different and hard. Have you ever said that to your husband? (Strategic question)

C: Yes. And he regrets it. He just loves to help now, but in my opinion, there’s no point to it now. (Understanding/insight or level 4)

Change equation=(Linear question)+(2)+(Empathy)+(2)+(Circular question)+(2)+(Linear question)+(4)+(Clarification)+(4)+(Interpretation)+(4)+(Circular question)+(4)+(Empty chair technique)+(4)+(Strategic question)+(4)

Consistent with the change equation and its codes at the starting point of the above excerpt, Mahnaz was in level 2 in APES. To continue, the therapist applied some skills and questions; as a result, Mahnaz went to level 4 which included other skills, questions, and the empty chair technique. Thus, another topic demonstrated that the patient had to be placed in the lowest level of APES insofar, and the therapist’s responses moved it.

At the starting point of the above excerpt, the client is forced to get married, and again the client is at a low level of APES. Mahnaz experiences stagnation in vague awareness/emergence (level 2) and after employing linear questioning, empathy, circular question, and linear questions by the therapist, Mahnaz improves and moves to level 3 (understanding/insight). Then again, the client experiences stagnation in level 3. The important fact is that the client moves on the APES continuum which continues with the therapist’s clarification, interpretation, circular question, the empty chair technique, and strategic question. Setbacks and stagnation in client’s responses on the APES levels are quite normal in topic change processes during client-therapist dual communications.

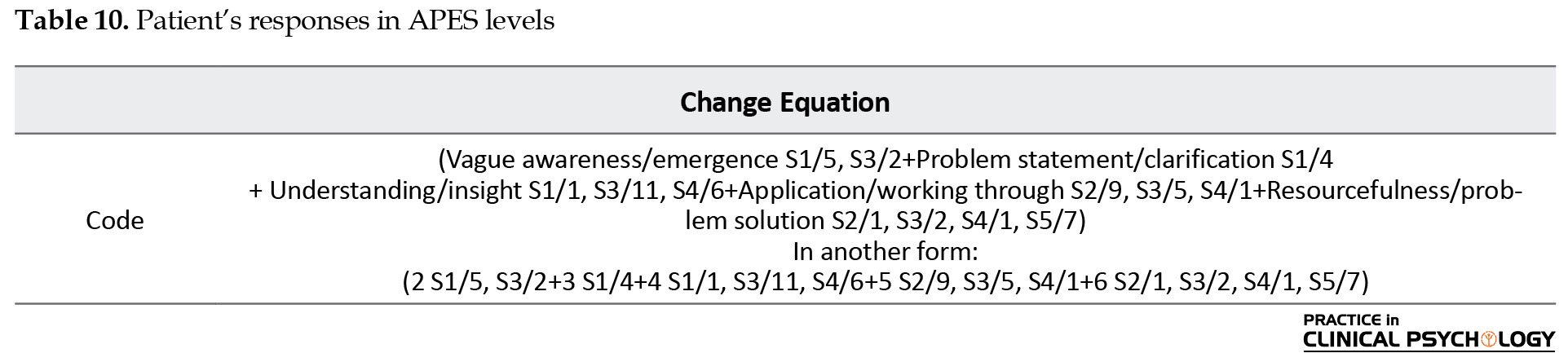

The client’s responses were discriminated in APES levels during 5 psychotherapy sessions. The client’s responses in APES levels are provided in Table 6.

Table 6 illustrates that the two first levels of APES do not have indexes in this case during psychotherapy and the appearance of one level such as vague awareness/emergence is not followed by all or none of the principles as they appear in understanding/insight and application/working through levels. This means that the distribution of APES levels is not session-specific; however, much higher levels of APES occur in the following sessions rather than in the preceding sessions. In addition, researchers did not find any index of integration/mastery within the client’s responses. However, the high levels of APES such as resourcefulness/problem solution were concentrated in the fifth session and when the case’s response demonstrates a high level in the APES continuum, regression to previous levels is rare. When one level is common in the first session, it decreases in the third session and does not appear in the fifth session. There is the level of application/working in the fifth session and the resourcefulness/problem solution level also occurred in the fifth session. Thus, the lowest level of the APES continuum may not illustrate an intake session at all. Also, the highest level of the APES continuum (integration/mastery) may not be observed in the middle sessions or the last ones.

The therapist’s responses were discriminated during the 5 psychotherapy sessions. The therapist’s responses are provided in Table 7.

Table 7 reveals that there is a moderate change in the use of skills such as linear questioning during psychotherapy sessions. While there are 7 linear questions in the first session, there are only 2 linear questions in the fifth session. In the first session, there are 3 empathy; however, there is 1 empathy in the third session and none in the fifth session. While the skills in starting sessions concentrate on discovery and fact finding, in later sessions they are centralized on the justification of change in feelings, beliefs, and behaviors of the client. Accumulation of linear questions and interpretation or clarification in the last sessions and the presence of encouragement and strategic and circular questions in the following sessions may confirm this inference.

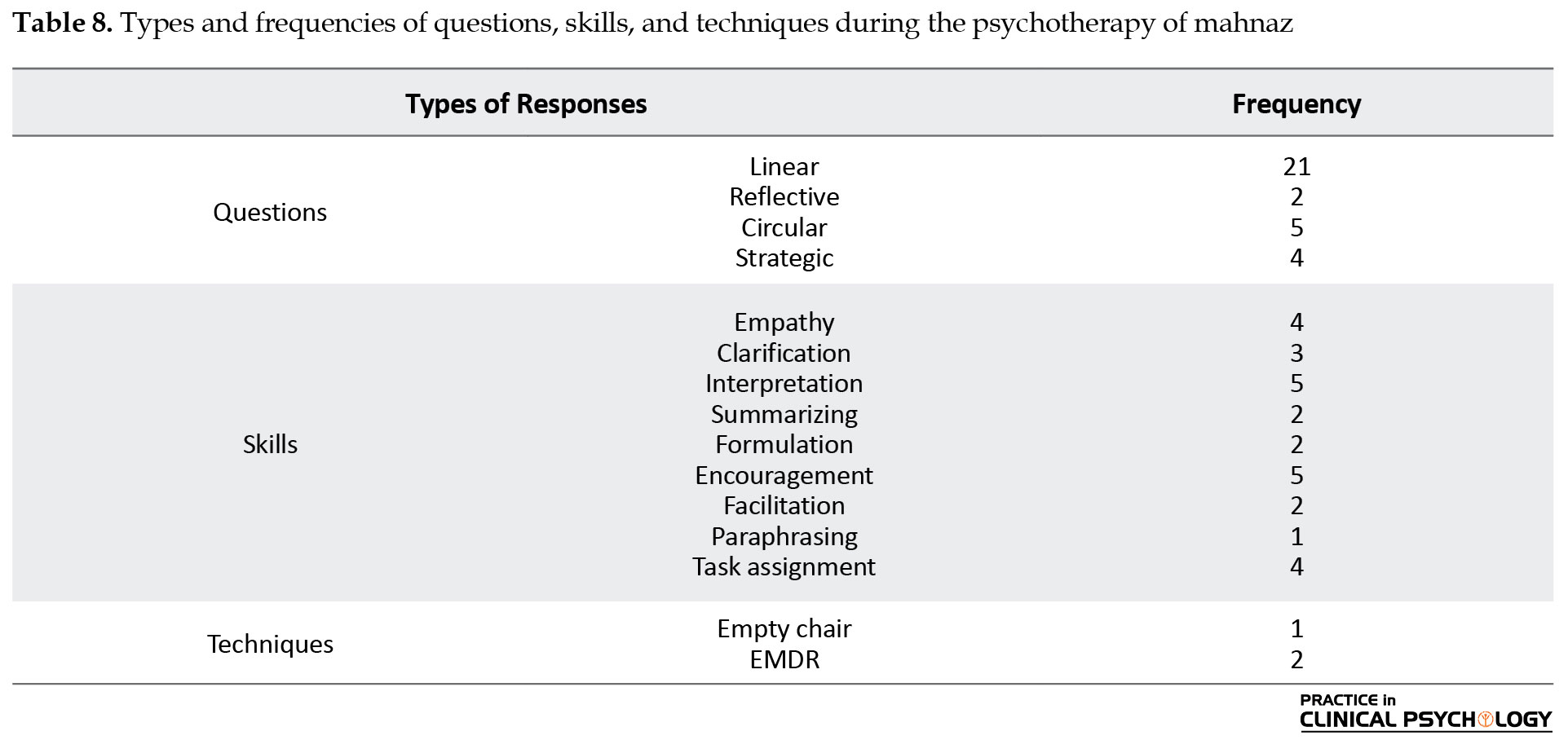

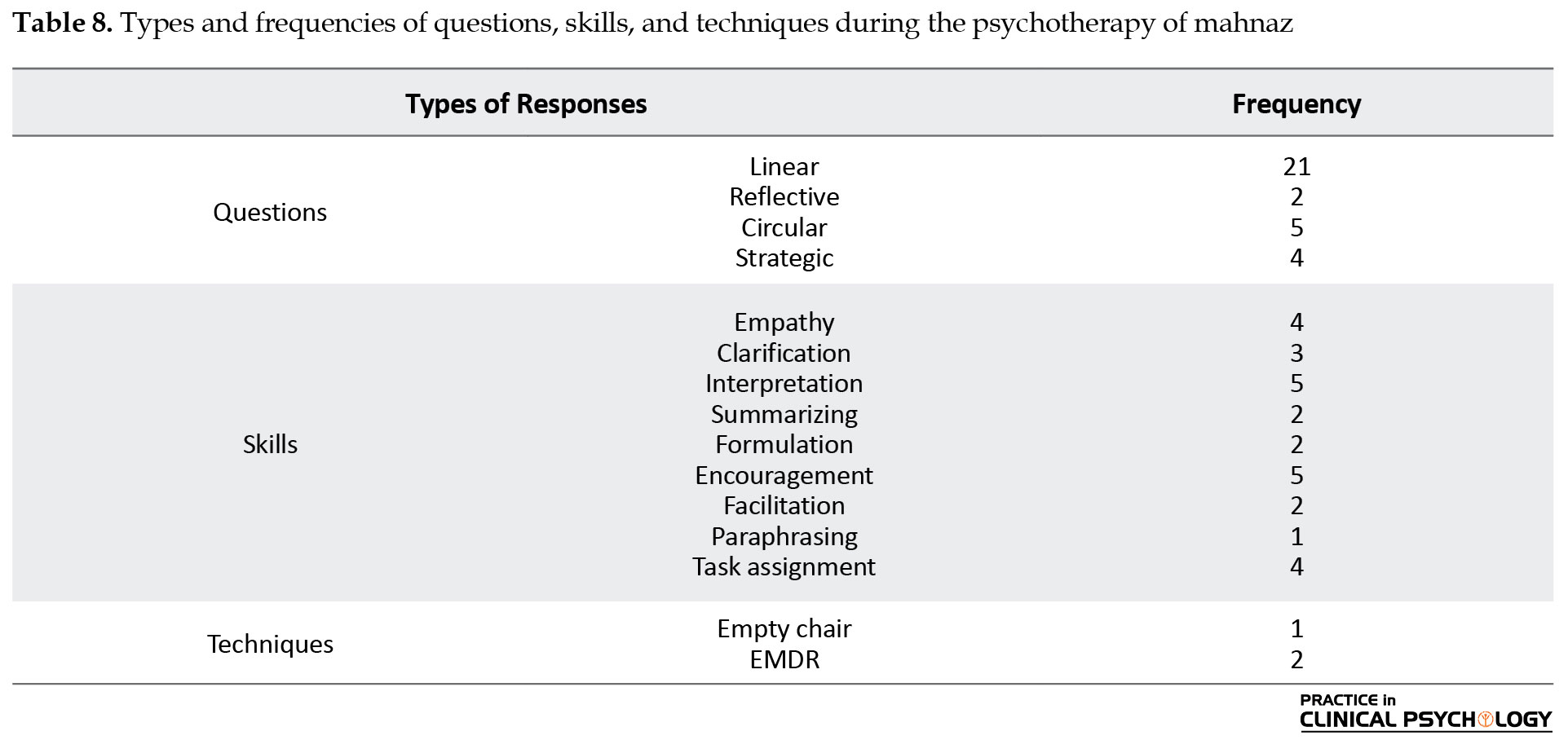

Types and frequencies of questions, skills, and techniques during psychotherapy of Mahnaz are provided in Table 8.

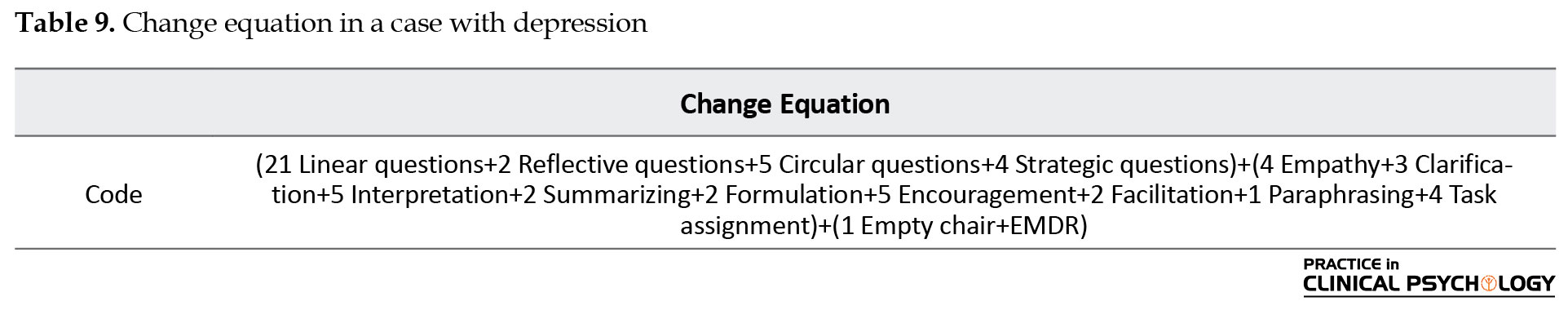

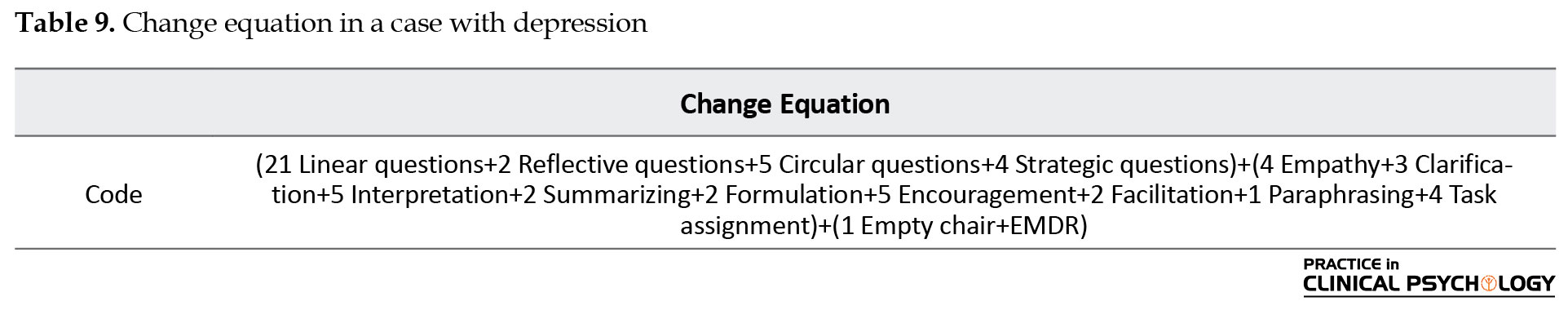

In the PFCA, the change equation based on the therapist’s responses and the frequencies are written by declarative sentences, and then they are followed by a symbolic system. Table 9 demonstrates the change equation only by declarative sentences.

Table 9 presents the change equation based on the therapist’s responses only. Table 9 is different from Table 10 in their data sources (the therapist’s or the client’s responses).

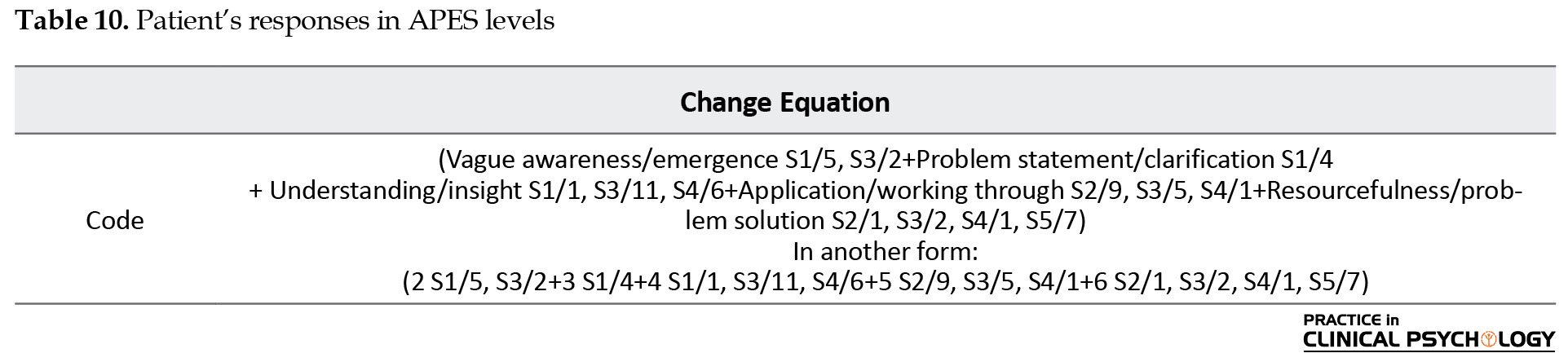

The Patient’s responses in APES levels are provided in Table 10. The data is extracted from Table 6.

In the above table, “S” is the abbreviation of the session; thus, “S1” means session 1 and the number after “/” is the response frequency; accordingly, S1/5, S3/2 means that vague awareness/emergence in session 1 has occurred 5 times and in session 3 has occurred 2 times; in another form, the number of levels is replaced with the name of the level.

In Table 10, there are all the case responses based on APES levels. Furthermore, the abbreviation form of these levels is a new way of presenting APES.

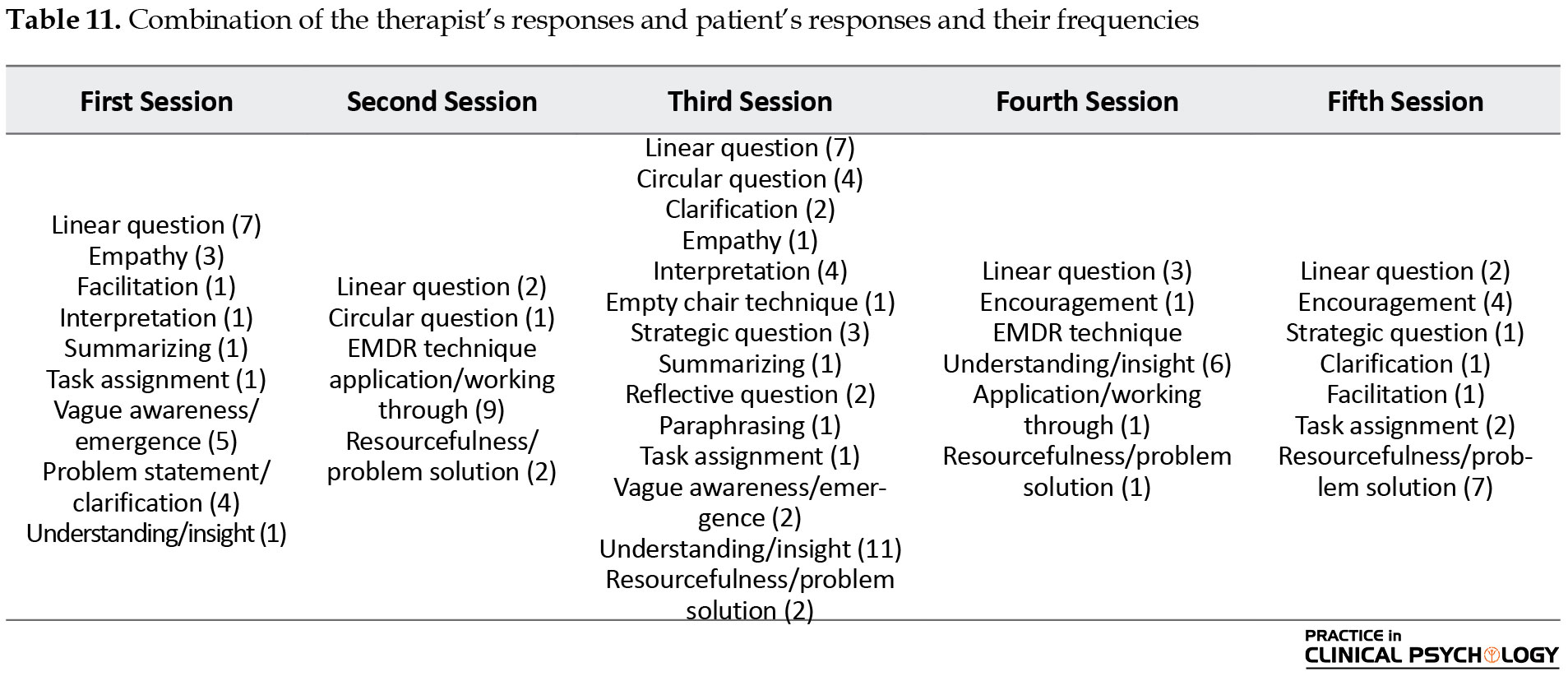

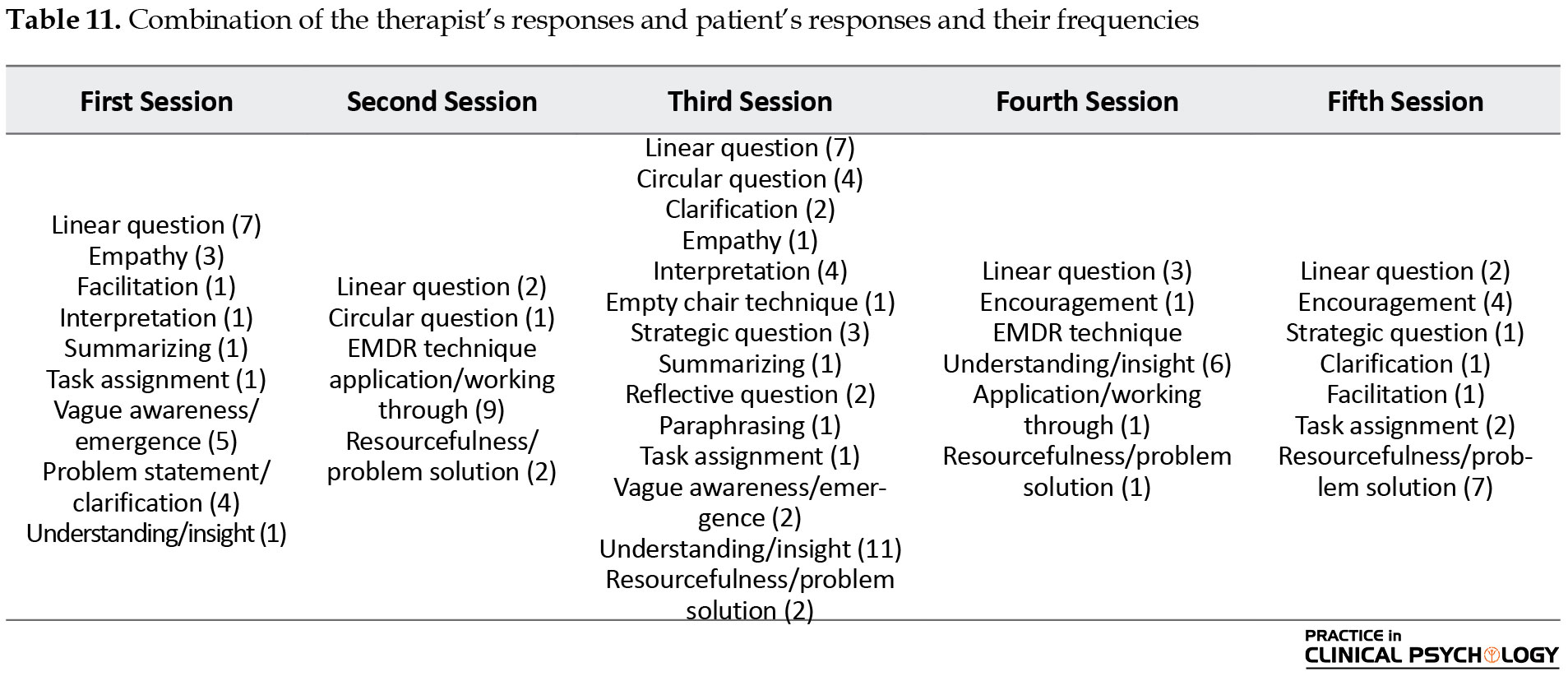

The combination of the therapist’s responses and the patient’s responses based on APES and PFCA during all sessions is provided in Table 11.

Fundamentally, the data in Table 11 shows how a therapist can prepare the circumstances for the emergence of a high APES level or an alternative voice. The therapist’s responsiveness and the client’s level of APES are clear in every column. It should be noted that if a therapist accepts the level of understanding/insight as a middle therapeutic point, we realize that session 3 is then the critical point. In other words, at this point, we are confronted with the most frequency of level 4 in the APES continuum. After this point, the client’s movement toward high levels of APES is accelerated and rapid changes through level 6 are considerable. By session 3, a great number of questions, skills, and techniques have been applied by the therapist and this leads to the client experiencing high levels of APES. This inference is consistent with the change equation in the second topic in session3:

Change equation=(Linear question)+(2)+(Empathy)+(2)+(Circular question)+2+(Linear question)+(4)+(Clarification)+(4)+(Interpretation)+(4)+(Circular question)+(4)+(Empty chair technique)+(4)+(Strategic question)+(4)

After some precise questioning and clarification or interpretation that is followed by one appropriate technique, such as the empty chair, the improvement of a client’s response is inevitable.

The change equation in the case of Mahnaz, based on both the therapist’s and the client’s responses is provided in Table 12.

The questions, skills, and techniques that have been practiced by the therapist are within the first bracket, and codes of the patient’s responses in APES levels are within the second bracket.

Table 12 indicates the change equation based on all the responses by the therapist and the client during the fifth session of psychotherapy. This equation can provide enormous data such as the therapist’s therapeutic orientation to their abilities or mistakes. For example, in this equation, there is no formulation as an important response of the therapist which is a mistake in the psychotherapy process.

The PFCA pyramid of change is created by a series or a sum of triangles, and each triangle represents one of the therapist’s responses, such as one linear question, or one of the client’s responses such as the vague awareness/emergence level. Furthermore, there is the patient’s response to the therapist’s response or vice versa. This series of responses is continued as shown in Figure 1.

.jpg)

Each triangle is representative of one of the responses by the therapist that is consistent with the client’s circumstances on one side and one triangle that is representative of one of the responses by the client on the other side. Each central topic in a therapeutic session includes a series of triangles and the pyramid of change consisted of several series of triangles. Each series of triangles includes some conversations between the client and the therapist that is called the Khayyami circle; it is named after the services of Omar Khayyam, the famous Iranian poet. Khayyami circle is about the concept of the spinning wheels and the philosophy of life. This is an important concept and this is where the change from a low level of client’s response to a higher level of responses occurs. Thus, the length of the therapy sessions is the function of the quantity of the central topics that are identified by dialogues.

The pyramid of change or the pyramid of therapeutic change is hypothesized and made by the sum of triangles that are in series. Accordingly, in the pyramid, questions are placed at the base, skills are at the center, and techniques are placed above them. The patient’s answers are at the top of the pyramid. The pyramid of therapeutic change is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 summarizes all the verbal responses by the therapist and the client during psychotherapy. The type of therapist’s responses can be seen by one glance at the pyramid; in addition, the therapeutic orientation of the practitioner is discovered.

4. Discussion

Consistent with the assimilation model’s expectations, good-outcome cases achieve significantly higher mean levels of assimilation compared to poor outcome cases. Specifically, good-outcome cases are more likely to attain APES Level 4 (understanding/insight). These results were consistent with other studies regarding APES. That is, the process of change resembled progress in assimilation and is observed in other similar studies. Along with the assimilation model expectations, the good outcome cases experience high levels of APES, such as understanding/insight. This expectation was met in the case of Mahnaz. Mahnaz changed her responses, particularly after session 3. This inference is consistent with Gonçalves et al. (2016), Basto, et al. (2016), Stiles, et al. (1992), and Stiles et al. (1991). Along with the results of these studies, case improvement is demonstrated with high levels of APES; meanwhile, APES level 4 is the important level in this subject (Caro Gabalda 2006; Basto, et al., 2016; Honos-Webb & Stiles, 1998). Notwithstanding, following the results of the present research, progression in APES levels during psychotherapy was not regular; in fact, the progression was irregular. Progression measured by APES is typically irregular. Setbacks in the assimilation process, defined as movement from a higher APES level to a lower one in successive passages, are common in all therapies that have been studied (Caro Gabalda and Stiles 2013, stiles et al. 2006). Caro Gabalda and Stiles (2013) proposed nine reasons for such setbacks: 1) multiple strands of a problem; 2) multiple internal perspectives on a problem; 3) interference from progress on other problems; 4) interference from life events; 5) exceeding the therapeutic ZPD; 6) the balance metaphor; 7) memory failure; 8) imprecision or inaccuracy of the measurements; 9) limitations of the theory. Among the reasons, at least reasons 1 (multiple strands of a problem) and 2 (multiple internal perspectives on a problem) existed in Mahnaz’s setbacks in the current research. While setbacks and stagnation within psychotherapy are normal, the change in the responses during treatment sessions in a good outcome client is altogether forward. Setbacks and stagnation in the client’s responses on APES levels are particularly normal events in the topic change process during client-therapist dual communications. It seems that setbacks, especially in topic changes processed between the client-therapist relations, are a current phenomenon because the client may state points that have to be clarified and facilitated by the therapist. Thus, setbacks and stagnation are normal events as long as one topic, cognitive and emotional reprocessing, is completed by the client-therapist dialogues.

According to the PFCA equation of change, only based on the therapist, verbal responses in psychotherapy sessions are a function of some questions, skills, and techniques. Following the coding of the therapist’s responses during the psychotherapy of Mahnaz by the training raters, it was revealed that PFCA has enough interrater reliability and content validity. When the therapist’s responses were coded on the basis of PFCA, and the client’s responses were coded by the APES levels in Mahnaz’s case, it appeared that the change equation during psychotherapy was completed. Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) offered guidelines and case illustrations of integration at 4 separate timeframes of intervention: treatment assignment, treatment strategies, treatment tactics, and moment-to-moment responsiveness within an intervention. In fact, the client’s requirements necessitate that the therapist utilizes an integrative approach to psychotherapy. The integrative approach to psychotherapy adapts to the specific needs and problems of patients. This conclusion is consistent with Trijsburg et al. (2002). Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) conclude that insofar as elements of the APES sequence are recognizable within many therapeutic approaches, many therapeutic approaches can assimilate the assimilation model’s description of developmental processes in therapy and its approach to integrating techniques that foster movement from one stage to the next. The fact that PFCA proposes an equation of change that emphasizes eclectic or integrative approaches in psychotherapy is fundamental. If we accept (consistent with Trijsburg at el. 2002) that in most psychotherapies, interventions from other orientations were also present to some degree, and the viewpoint of Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) of integration at 4 separate timeframes of intervention, namely treatment assignment, treatment strategies, treatment tactics, and moment-to-moment responsiveness within an intervention, then the utilization of the PFCA will be a suitable method to code the therapist’s responses.

The results of the present study show that changes in the client’s responses occur proportionally to changes in the therapist’s responses. This conclusion is consistent with the results of many studies such as Ribeiro, et al. (2016), Caro Gabalda and Stiles (2013), Caro Gabalda (2006), and Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998). Although the therapist organizes the therapeutic sessions, we cannot claim that changes in the client are only a function of changes in the therapist’s responses. However, we know that both responses are necessary to move toward change. On the other hand, the results of the present study show that the change in the client’s responses is consistent with the developmental levels of the assimilation model, but one should not conclude that the therapist’s responses are the cause of the client’s responses. In fact, in the case of Mahnaz, there are various factors, such as different questions, skills, and techniques, in the therapeutic changes as well as in setbacks and stagnation. Therefore, replying to this question as to which therapeutic interventions are optimally responsive at each APES level is very difficult or maybe impossible. Some researchers, for example, Ribeiro et al. (2013), operationalized responses to the above question and believed that there are two subgroups of therapist’s intervention, namely supporting sub-categories and challenging markers sub-categories, but the main condition that delineates valid intervention from invalid intervention depends on the relation of the intervention to the client’s ongoing TZPD. Ribeiro et al. (2013) accept that therapists do not have prior knowledge about the client’s potential level, but following an implicit principle of “push where it moves,” they can adjust when and what they support (e.g., work at or near the client’s ongoing assimilation level) or challenge (e.g., work slightly beyond the client’s ongoing assimilation level) to help clients advance along the developmental continuum. Thus, efficient interventions have to be delineated at the moment and situation in which the client is.

In another viewpoint, Leiman (2012) in his article titled “Dialogical Sequence Analysis (DSA)” argues that in a patient-therapist relation, it is necessary to analyze both the patient’s and the therapist’s speech (affected by Freud and Bakhtin). In fact, the core of DSA is the claim that every utterance expresses the speaker’s position, and simultaneously, to the referential object of the speech and the addressee, i.e., to whom the utterance is meant. The idea of double positioning forms the fundamental rule of the DSA in studying the client’s utterances. Therefore, in psychotherapy, the client’s responses are affected by the therapist’s responses and vice versa. Thus, it is the presence of the client, the therapist, and their interactions that is the healer. In truth, treatment occurs in the patient-therapist-patient sequences or the patient-therapist-patient trial space; that is, the dialogical essence of psychotherapy is the healer. In the therapeutic field, dialogical perspectives explore how their principles can be applied to the understanding of psychopathology and psychotherapy (Lysaker and Lysaker 2006, Osatuke and Stiles 2006, Hermans and Dimaggio 2004). Because of the dialogical nature of its existence (Salgado, & Gonc¸alves, 2007; Goncalves and Guilfoyle, 2006; Valsiner, 2004; Bakhtin, 2000; Fogel, 1993), psychotherapy is converted into a reprocessing field or making meaning bridges (Salgadoand Gonc¸alves, 2007; Goncsalves and Guilfoyle, 2006; Valsiner, 2004; Bakhtin, 2000; Fogel, 1993). After all, according to Ribeiro et al. (2013), Leiman (2012), Salgado and Goncalves (2007), and Hermans and Dimaggio (2004), the delineation of optimally therapeutic responses at each APES level depends on the client’s frame of reference and the kinds of therapist’s responses at the moment. Thus, only after therapeutic sessions, determination of the treatment assignment, treatment strategies, treatment tactics, and moment-to-moment responsiveness (as distinguished by Honos-Webb and Stiles, 1998) and some questions, some skills, and some techniques will be possible. In the case of Mahnaz, it was pinpointed that the sequence of several questions, skills, and one or two techniques are effective at the client’s APES level.

On the other hand, using PFCA along with an assimilation model is a successful framework for simply introducing the events in the course of psychotherapy and hypothesis testing. Writing the change equation and drawing the change pyramid are two different styles to follow the therapist’s and the client’s responses altogether after therapeutic sessions. The therapist can consider which question had more frequency and where it was within the psychotherapy process; this is the same concerning skills and techniques. Because writing the therapist’s and the client’s responses in the change equation is done session by session, it is possible to compare the fitness or unfitness in every one of the therapist’s and the client’s responses. Identifying the series of triangles or the Khayyami wheel is very important. The khayymi circle is where the change from a low level of the client’s response to a higher level of response occurs, thus creating a Khayyami circle. But the important function of the Khayyami circle is to show the path of change in the client’s responses. Linear question plus circular question plus interpretation in the example of conversations in Mahnaz’s case shows the process of change in the client’s responses. The claim that the change experienced by the client is because of the Khayyami circle is a superficial inference. However, we cannot select one rule of change and generalize it to other situations. We still do not know which specific response of the therapist in a specific client triggers which type of change. The therapist is constantly one step behind the client because they have to wait to see the effects of their response. Early judgment, in this case, diverts the therapist from a systemic and postmodernist point of view. Presently, we know about the sources of change in the clients that being in a therapist situation causes the monologue in the clients to become a process of dialogue. This causes the emergence of three positions: speaker, audience, and referral content (client, therapist, and subject). At these moments, the meaning can be rotated within these positions. Meaning rotates within a circular space and the subject becomes boundless (Khayymi circle). The subject in space and time rotates in a circular motion. Counseling sessions provide a new opportunity for the client to create new moments and a reprocessing space for meaning through expression and collaborative style of relations. In this case, is it the type of therapist’s responses that causes the change? Or, what is the share of the client’s response in this case? These questions are not easy to answer. To determine the share for each of the effective factors in change, a need for studies arising from a precise methodology exists; however, the effective factors in this change include the following items: 1) sequences of conversation between the client and the therapist; 2) preparative responses by the counselor (questions, skills, and techniques) that are consistent with the subject and the content of the discussion; 3) preparedness and expectation of change in the client.

Observation and inquiry of development, stagnation, and setbacks of APES levels become simplified and the therapist focuses better on evaluating the quality of responses. In the pyramid of change, questions such as linear and circular questions, are located at the base, skills are located in the center, and techniques are located at superior and higher APES levels at the peak of the pyramid. This placing of questions, skills, techniques and higher APES levels in the change pyramid is because of their different roles during psychotherapy sessions. The accumulation of different kinds of questions in intake sessions is common and different kinds of skills and techniques are more frequent in middle sessions. Higher APES levels are the end product of treatment; therefore, they are placed at top of the change pyramid. These conclusions about the status of different kinds of questions, skills, and techniques within therapeutic sessions are consistent with Geldard and Geldard (2012), Bartesaghi (2009), Bavelas et al. (2000), and Tomm (1987). It is particularly noteworthy that the change equation of each person is unique. Hence, every client has their own specific change pyramid because each person has specific topics related only to them in their own life history as with the case of Mahnaz (an authoritarian father and forced marriage). Furthermore, the pyramid of therapeutic change and a series of triangles were introduced in this article, presenting one graphic design that showed all the exchanged responses and dialogues between the patient and the therapist in a very simple and clear way.

In the present study, the research method was a case study; therefore, all of these explanations have to be considered based on the limitations of this method. In addition, researchers had to translate the utterances of the client and the therapist into three languages (Turkish to Persian and Persian to English); therefore, it was necessary to pay extra attention to these translations. Furthermore, both APES and PFCA coding systems concentrate only on the verbal responses of the therapist and the client and ignore the emotional state and all that it entails.

The conclusions are comparable with the results of previous studies. Case improvement was demonstrated at high levels of APES, and APES level 4 is the important level. As the results of the present research showed, progression measured by the APES was typically irregular. Setbacks and stagnation are common within psychotherapy which is similar to many therapies that have been studied. The case of Mahnaz showed that the two first levels of APES did not have indexes during psychotherapy; thus, it is necessary to review the validity of these levels or their definitions. According to PFCA, the equation of change based only on the therapist’s verbal responses during a psychotherapy session is the function of several questions, skills, and techniques. This is consistent with treatment assignment, treatment strategies, treatment tactics, and moment-to-moment responsiveness. The combination of PFCA and APES revealed a suitable method for the realization of dual dialogues during psychotherapy. This helps to complete the change pyramid and calculate the case improvement indexes. Using PFCA together with an assimilation model is a suitable method to demonstrate the uniqueness of a person’s change equation.

5. Conclusion

It seems that using PFCA along with an assimilation model is a successful framework for simply introducing events in the course of psychotherapy and hypothesis testing. Writing the change equation and drawing the change pyramid are two different styles to follow the therapist’s and the client’s responses altogether after therapeutic sessions. The therapist can consider which question had more frequency and where it was within the psychotherapy process and this is the same concerning skills and techniques. Because writing the therapist’s and the client’s responses in a change equation is done session by session, it is possible to compare the fitness or unfitness in every one of the therapist’s and the client’s responses. Observation and inquiry of development, stagnation, and setbacks of APES levels become simplified and the therapist focuses better on evaluating the quality of responses. In the pyramid of change, questions such as linear and circular questions, are located at the base, skills are located in the center, and techniques are located at superior and higher APES levels at the peak of the pyramid. This placing of questions, skills, techniques and higher APES levels in the change pyramid is because of their different roles during psychotherapy sessions.

The practical benefits of this research are that if the results are repeated, the practitioner can find rules for faster change in the patient’s symptoms and problems. Meanwhile, the course of counseling and psychotherapy becomes more objective and also shows the differences and similarities of different counseling methods; thus, psychotherapy would become easier. Appointment of sequences implications in psychotherapy sessions or Khayyami circle is a very important task of the therapist that can increase their ability in the client’s responses during change.

One of the main limitations of this type of research is recording the sessions, which most clients oppose. Training the coders is another limitation and should be done as carefully as possible. It is suggested that such studies be conducted as a case study on other people in the same order to examine the Khayyami circle in them during the change of the client’s responses. This is used alongside process-focused conversation analysis. Another suggestion is to use quantitative research methods, such as control groups and experiments to increase the generalizability of the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has received ethics code from Ardabil Medical Science University. This code is observable in http://ethics.research.ac.ir/IR.ARUMS.REC.1398.409 (the website of the National Ethics Committee in Biomedical Researches) (Code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1398.409).

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (Grant Number: 2195)

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, writing - review and editing and supervision: Hossein Ghamari Kivi; Writing - original draft preparation: Hossein Ghamari Kivi, Ahmad Reza Kiani; Funding acquisition and Resources: Ahmad Reza Kiani;

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Research Department of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili. We would like to thank the deputy of the Research Department and the directors and experts of that department.

Consent for Publication

Authors and the vice-chancellor of research at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabil subscribe to publish this article.

References

Angus, L., Levitt, H., & Hardtke, K. (1999). The narrative processes coding system: Research applications and implications for psychotherapy practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(10), 1255 1270. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)10974679(199910)55:103 0.CO;2-F]

Bakhtin, M. M. (2010). The dialogical imagination: Four essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Link]

Bartesaghi, M. (2009). Conversation and psychotherapy: How questioning reveal institutional answers. Discourse Studies, 11(2), 153-177. [DOI:10.1177/1461445608100942]

Basto, I., Pinheiro, P., Stiles, W. B., Rijo, D., & Salgado, J. (2017). Changes in symptom intensity and emotion valence during the process of assimilation of a problematic experience: A quantitative study of a good outcome case of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of The Society for Psychotherapy Research, 27(4), 437-449. [PMID]

Bavelas, J. B., McGee, D., Phillips, B., & Routledge, R. (2000). Microanalysis of communication in psychotherapy. Human Systems, 11(1), 3-22. [Link]

Gabalda, I. C., Stiles, W. B., & Pérez Ruiz, S. (2016). Therapist activities preceding setbacks in the assimilation process. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of The Society for Psychotherapy Research, 26(6), 653–664. [PMID]

Caro Gabalda, I., & Stiles, W. B. (2013). Irregular assimilation progress: Reasons for setbacks in the context of linguistic therapy of evaluation. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 23(1), 35–53. [PMID]

Gabalda, I. C. (2006). The assimilation of problematic experiences in linguistic therapy of evaluation: How did María assimilate the experience of dizziness? Psychotherapy Research, 16(4), 422-435. [DOI:10.1080/10503300600756436]

Goncalves, M. M., & Guilfoyle, M. (2006). Therapy as a monological activity: Beliefs from therapists and their clients. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19, 251-271. [Link]

Ghamari Kivi, H.(2019). [Process-focused conversation analysis: Proposing an approach for intervention and assessment the field of counseling and psychotherapy with people suffering from depression (Persian)]. Journal of Counseling Research, 18(69), 4-30. [DOI:10.29252/jcr.18.69.4]

Goncalves, M. M., Ribeiro, A. P., Silva, J. R., Mendes, I., & Sousa, I. (2016). Narrative innovations predict symptom improvement: Studying innovative moments in narrative therapy of depression. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of The Society for Psychotherapy Research, 26(4), 425–435. [PMID]

Gonçalves, M. M., Gabalda, I. C., Ribeiro, A. P., Pinheiro, P., Borges, R., & Sousa, I., et al. (2014). The innovative moments coding system and the assimilation of problematic experiences scale: A case study comparing two methods to track change in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of The Society for Psychotherapy Research, 24(4), 442–455. [PMID]

Goncalves, M. M., Matos, M., & Santos, A. (2009). Narrative therapy and the nature of “innovative moments” in the construction of change. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 22(1), 1-23. [DOI:10.1080/10720530802500748]

Hermans, H. J., & Dimaggio, G. (2004). The dialogical self in psychotherapy. In H. Hermans, & G. Dimaggio (Eds.), The dialogical self in psychotherapy (pp. 17-26). New York: Routledge. [Link]

Honos-Webb, L., & Stiles, W. B. (1998). Reformulation of assimilation analysis in terms of voices. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 35(1), 23-33. [DOI:10.1037/h0087682]

Honos-Webb, L., Stiles, W. B., Greenberg, L. S., & Goldman, R. (1998). Assimilation analysis of process-experiential psychotherapy: A comparison of two cases. Psychotherapy Research, 8(3), 264-286. [DOI:10.1093/ptr/8.3.264]

Leiman, M. (2012). Dialogical sequence analysis in studying psychotherapeutic discourse. International Journal for Dialogical Science, 6(1), 123-147. [Link]

Lysaker, P. H., & Lysaker J. T. (2006). A typology of narrative impoverishment in schizophrenia: Implications for understanding the process of establishing and sustaining dialogue in individual psychotherapy. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 19(1), 57-68. [DOI:10.1080/09515070600673703]

Meystre, C., Kramer, U., Roten, Y. D., Despland, J. N., & Stiles, W. B. (2014) How psychotherapeutic exchanges become responsive: A theory-building case study in the framework of the Assimilation Model. Counselling and Psychotherapy Researc, 14(1), 29-41. [DOI:10.1080/14733145.2013.782056]

Osatuke, K., & Stiles, W. B. (2006). Problematic internal voices in clients with borderline features: An elaboration of the assimilation model. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(4), 287-319. [DOI:10.1080/10720530600691699]

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19(3), 276-288. [DOI:10.1037/h0088437]

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. [Link]

Prochaska, J. O. & DiClemente, C. C. (2005). The Transtheoretical Approach. In J. C. Norcross, & M. R. Goldfried, (Eds.). Handbook of psychotherapy integration (2 ed.) (pp. 147-171). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [DOI:10.1093/med:psych/9780195165791.003.0007]

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114. [PMID]

Ribeiro, E., Cunha, C., Teixeira, A. S., Stiles, W. B., Pires, N., & Santos, B., et al. (2016). Therapeutic collaboration and the assimilation of problematic experiences in emotion-focused therapy for depression: Comparison of two cases. Psychotherapy research: Journal of The Society for Psychotherapy Research, 26(6), 665-680. [PMID]

Ribeiro, E., Ribeiro, A. P., Gonçalves, M. M., Horvath, A. O., & Stiles, W. B. (2013). How collaboration in therapy becomes therapeutic: The therapeutic collaboration coding system. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 86(3), 294-314. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8341.2012.02066.x] [PMID]

Salgado, J., & Gonc¸alves, M. (2007). The dialogical self: Social, personal, and (un)conscious. In J. Valsiner , & A. Rosa (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Link]

Stiles, W. B. (1980). Measurement of the impact of psychotherapy sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48(2), 176-185. [DOI:10.1037/0022-006X.48.2.176] [PMID]

Stiles, W., Meshot, C., Anderson, T., & Sloan, W. (1992). Assimilation of problematic experiences: The case of John Jones. Psychotherapy Research, 2(2), 81-101. [DOI:10.1080/10503309212331332874]

Stiles, W. B., Morrison, L. A., Haw, S. K., Harper, H., Shapiro, D. A., & Firth-Cozens, J. (1991). Longitudinal study of assimilation in exploratory psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 28(2), 195-206. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.28.2.195]

Stiles, W. B., Elliott, R., Llewelyn, S. P., Firth-Cozens, J. A., Margison, F. R., & Shapiro, D. A., et al. (1990). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(3), 411-420. [DOI:10.1037/0033-3204.27.3.411]

SStiles, W. B., Leiman, M., Shapiro, D. A., Hardy, G. E., Barkham, M., & Detert, N. B., et al. (2006). What does the first exchange tell? Dialogical sequence analysis and assimilation in very brief therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 16(4), 408-421. [DOI:10.1080/10503300500288829]

Trijsburg, R. W., Frederiks, G. C. F. J., Gorlee, M., Klouwer, E., Hollander, A. D., & Duivenvoorden, H. J. (2002). Development of the comprehensive psychotherapeutic interventions rating scale (CPIRS). Psychotherapy Research, 12(3), 287_317. [DOI:10.1093/ptr/12.3.287]

Tomm, K. (1987). Interventive interviewing: Part II. Reflexive questioning as a means to enable self-healing. Family Process, 26(2), 167-183. [PMID]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. [Link]

Psychotherapy is two-way communication between the therapist and the client; hence, every analysis must include responses from both sides. This is consistent with Stiles (1980) viewpoint that “to influence psychotherapeutic practice, the outcome research must address itself to the level at which therapeutic decisions are made—the moment-by-moment interchange between the client and the therapist.” However, current models investigate the responses of the therapist and the client differently and separately. There are at least five methods for analyzing the client’s behavior change stages based on different theoretical backgrounds. Assimilation of problematic experiences scale (APES) tracks problematic experiences across therapy sessions and describes a sequence of eight stages or levels of APES, from being dissociated or unwanted to being understood and integrated (Stiles, et al., 1992; Stiles et al., 1991; Stiles et al., 1990). The innovative moments coding system (IMCS) was introduced by Goncalves, Matos, and Santos (2009). This system includes five stages from action to performing the change. The narrative processes coding system has three distinct modes of inquiry, namely external, internal, and reflexive narrative modes (Angus, Levit and Hardtke, 1999). Ribeiro et al. (2013) introduced the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) which is based on Vygotsky (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). ZPD includes both the therapist’s intervention and the client’s responses (in five subgroups for the client) and exchange or two peaking turns.

Another comprehensive model for understanding the change process has emerged from the work of Prochaska, DiClemente, and their associates (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982, 1984, 2005; Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992). They derived an understanding of how people change (i.e., the processes) via the development of a transtheoretical model called the “Stages Of Change” (SOC) which outlines the five stages of change (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation for action, action, and maintenance). The SOC model suggests that people are not uniform in their understanding of problematic behaviors, their need for change, or their motivation to make a change.

The assimilation model offers an approach for customizing the therapeutic relationship through responsiveness (Stiles et al., 1990). This model conceptualizes the psychotherapy outcome as a change concerning particular problematic experiences, memories, wishes, feelings, attitudes, or behaviors that are threatening or painful or come from destructive relationships and traumatic incidents, rather than a change in the person as a whole. It suggests that in successful psychotherapy, clients follow a regular developmental sequence of recognizing, reformulating, understanding, and eventually resolving the problematic experiences that have brought them to treatment. Stiles et al. (1990) believed that a problematic experience is assimilated into a schema, a way of thinking, and acting that is developed or modified within the therapeutic relationship (accommodation) to assimilate the problematic experience. The assimilation model was adapted to a dialogical view by its introducers (such as Stiles, 1998). Meanwhile, the process of assimilation was described using the metaphor of voice (Honos-Webb & Stiles, 1998). This metaphor expresses the theoretical tenet that the traces of past experiences are active agents within people and are capable of communication. These traces can act and speak. Dissociated (unassimilated) voices tend to be problematic, whereas assimilated voices can act as resources. During a psychotherapy session with a client named John Jones, Stiles et al. (1992) found the assimilation model a useful rubric for conceptualizing John Jones’s evident progress in psychotherapy. In a case study, Meystre et al. (2014) showed how specific interventions by the therapist may facilitate assimilation. They also underlined the dialogical dimension of the therapy process. Caro Gabalda, Stiles, and Ruiz (2015) examined the therapist’s activities immediately preceding assimilation setbacks (a setback was defined as a decrease of one or more APES stages from one passage to the next, dealing with the same theme; for instance, from APES 4 to APES 3). Results showed that preceding setbacks to earlier assimilation stages where the problem was unformulated, the therapist was more often actively listening. Also, the setbacks were more often attributable to pushing a theme beyond the client’s working zone. Preceding setbacks to later assimilation stages where the problem was at least formulated, the therapist was more likely to be directing the client to consider alternatives, following the language therapy of the evaluation agenda. Meanwhile, the setbacks were more often attributable to the client following such directives, shifting attention to less assimilated (nevertheless formulated) aspects of the problem. As a result, the setbacks followed systematically different therapists’ activities depending on the problem stage of the assimilation.

Basto et al., (2016) showed changes in symptom intensity and emotion valence during the process of assimilation of a problematic experience. Ribeiro et al. (2016) revealed the APES and the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) drawn from a clinical trial of 16 sessions of Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT) for depression in two cases. This study supports the theoretical expectation that EFT therapists work mainly within their client’s Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development (TZPD). Therapeutic exchanges involving challenging interventions may foster client change if they occur in an overall climate of safety.

In one research, APES and the Innovative Moments (IMs) method were compared. Gonçalves et al. (2014) applied the methods to the transcripts of a successful case of linguistic therapy of evaluation independently in different research groups. The assimilation theory and the research suggested that higher APES scores reflect therapeutic gains with an approximate level of 4.0, separating the good from the poor outcome cases. The IMs model suggests that IMs classified as reconceptualization and performing change occur mainly in good outcome cases. This is while action, reflection, and protest occur in both good and poor outcome cases. Passages coded as reconceptualization and performing change were rare in this case; however, all were rated at or above APES 4.0. By contrast, 63% of the passages coded as action, reflection, or protest were rated below APES 4.0.

On the other side of the therapist-client communication analysis, there are the therapist’s responses. Unfortunately, little attention has been devoted to conceptualizing the therapist’s responses in the change process and few models describe and explain the background of change from this point of view. It is noteworthy that in analyzing the client’s behavior, William B. Stiles is the pioneer in classification and forming models of the therapist’s responses, although Verbal Response Modes (VRMs) entail both members of a dyad communication. Stiles (1992) wrote “both members of a dyad (e.g., the client as well as the therapist) can be the speakers in turn, and the taxonomy applies equally to both (Adopted from Stiles. 1992).

Ribeiro et al. (2013) presented another model for analyzing therapist-client communication. They revealed that the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS) investigates each speaker’s turn and assesses whether and how therapists work within the client’s TZPD, defined as the space between the client’s actual therapeutic developmental level and their potential developmental level that could be reached in collaboration with the therapist.

There is a body of research in the realm of psychotherapy that has been directed only to the client’s responses and few have concentrated on the therapist’s responses. Indeed, the behavior changes that coincide between the client and the therapist or the sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses have been less analyzed. On the other hand, there are no studies regarding the implications of sequences within conversations. It seems that without analyzing the therapist’s responses within the conversational process of psychotherapy, understanding the concept of therapeutic change will be difficult. For example, Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) hypothesized that a patient is better able to reach a higher assimilation level if the therapist’s intervention is appropriate to the patient’s ongoing level.

Currently, there is no serious coding system for the therapist’s responses in the realm of psychotherapy. Hence, PFCA which has been reported by the first author of this article (2019 in Persian) as a coding system can be useful in clarifying the therapist’s responses. PFCA delineates the therapist’s understanding of the client and their efforts to open the conversational spaces to encourage a movement in the client’s constructions.

In this study, researchers have concentrated on coincident changes in responses of both the therapist and the client during psychotherapy to answer the following questions: which therapeutic intervention is optimally responsive at each APES level? And, how can the researcher delineate the responses of the therapist and the client on the change equation? In this study, researchers have combined APES (as a coding system of the client’s responses) and PFCA (as a coding system of the therapist’s responses) to clarify the sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses during psychotherapy. As a result, in PFCA the question is, under which therapist responses do higher levels of APES occur? Thus, as the main goal of the present research, the APES for coding the client’s responses and the PFCA for coding the therapist’s responses were applied to the transcripts of a successful case of integrative psychotherapy of depression to coincide with sequences of patient-therapist-patient responses.

2. Materials and Methods

The case of Mahnaz (a pseudonym)

The method for this research is a case study. The client was referred to Sepand Counseling Center in Ardabil City, Iran. The case was selected by an accessible method and entered into the research. Existence of a disorder, non-use of medication, and voluntary acceptance of counseling were the inclusion criteria of the study, and unwillingness to continue the counseling was one of the exclusion criteria. For following the ethical considerations, the authorities were assured that her name and initial details would be deleted and they would be confidential if the report was submitted and printed. Meanwhile, as the meetings were recorded, the authorities were assured that the voices would not be heard by anyone under any circumstances.

Mahnaz was a 55-year-old homemaker with a high school diploma. She showed symptoms of sadness, crying, poor attention, and sluggishness. She also manifested a lack of enjoyment of life, feelings of guilt, self-blame, and blaming others. Mahnaz had three daughters and her husband was a 65-year-old teacher. Her children were all married and had completed their higher education; one in Ardabil, one in Tehran, and one in the US. Mahnaz had 5 individual sessions from June to September 2019 and 4 sessions accompanied by her husband. The 5 individual sessions were recorded and the contents (150 dialogues between the therapist and the client) were transcribed by the researchers.

Instruments

Therapist

The therapy was conducted in Iran. The therapist (first author of this article) is a psychotherapist and a member of the Psychology and Counseling Organization of Iran; an academician with more than 30 years of experience as a therapist and supervisor.

Treatment

The therapist’s approach was integrative. This approach is influenced by and related to the intervention interview of Tomm, K. (1987). According to PFCA, in psychotherapy, change is a function of a series of linear and nonlinear questions, as well as several circular, reflective, and strategic questions, along with counseling skills such as paraphrasing or reframing and one or more theory-based techniques such as flooding (extracted from behavior therapy) and empty chair (extracted from Gestalt therapy). These are consistent with the opinions of Trijsburg et al. (2002) that clinical practice may be more eclectic or integrative than psychotherapeutic schools may presume. On the other hand, Honos-Webb and Stiles (1998) revealed that therapeutic responsiveness can occur on time scales that range from months to milliseconds, from treatment assignment to subtle mid-intervention shifts.

The assimilation model provides a way to understand and track emerging client requirements which may then be used to suggest appropriate treatments, strategies, tactics, and intervention implementations. Therefore, an integrative approach in psychotherapy and counseling is one in which the therapist, with their immediacy and free-floating attention, can better pursue an appropriate therapeutic response as one that meets the client’s requirements at a given stage of assimilation and helps to shift the client’s assimilation of a given problematic experience from one stage to the next. To do so, the therapist has to follow an eclectic/integrative approach to work at its best.

Outcome measures

Four-dimensional Symptom Questionnaire

The Four-dimensional symptom questionnaire (4DSQ) is a self-report questionnaire that measures distress (16 items), depression (6 items), anxiety (12 items), and somatization (16 items) with separate scales (24). The items are answered on a 5-point frequency scale from “No” to “Very Often or Constantly”. To calculate the sum of scores, responses are coded on a 3-point scale: “No” (0 points); “Sometimes” (1 point); “Regularly”, “Often”, and “Very often or Constantly” (2 points). Reliability coefficients in the Cronbach’s α method for distress, depression, anxiety, and somatization subscales are 0.926, 0.909, 0.879, and 0.845, respectively. In the present study, the client completed 4DSQ in the pretest and posttest phases. Results of the 4DSQ in pretest and posttest phases are provided in Table 2. Table 2 demonstrates Mahnaz’s Pretest-posttest Scores on 4DSQ. This table indicates that scores in the posttest phase have changed after the treatment sessions.

.jpg)

Process measures

Assimilation of Problematic Experiences Scale

The APES scale was used to assess the levels of APES (Table 3).

.jpg)