Volume 7, Issue 1 (Winter 2019)

PCP 2019, 7(1): 21-32 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khazaeili M, Zargham Hajebi M, Mohamadkhani P, Mirzahoseini H. The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Anxiety, Depression and Burden of Caregivers of Multiple Sclerosis Patients Through Web Conferencing. PCP 2019; 7 (1) :21-32

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-591-en.html

URL: http://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-591-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Qom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Burden, Mindfulness-based intervention, Multiple Sclerosis, Caregivers, Anxiety, Depression

Full-Text [PDF 615 kb]

(2334 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (9747 Views)

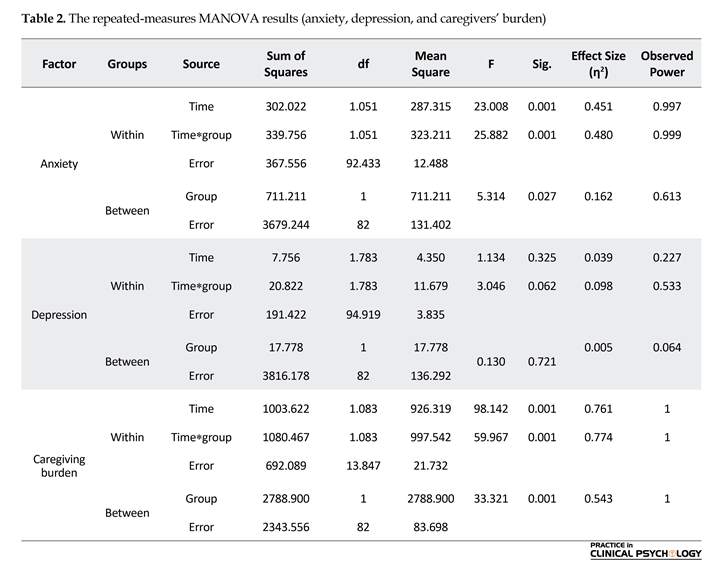

The results related to the depression variable in Table 2 indicate that the effect of test time on depression scores is not significant (F=1.134; Sig.=0.325; η2=0.039). In other words, there is no significant difference between the mean scores of depression in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. Also, the effect of group was not significant (F=0.130; Sig.=0.721; η2=0.005). As a result, there is no significant difference between the mean scores of depression in both groups. Moreover, the effect of interaction between the group and the test time was also not significant (F=3.046; Sig.=0.062; η2=0.098). So, there is no significant difference between the mean depression of caregivers in both groups in the pre-test, post-test and follow-up stages.

The results of the caregiving burden reveals that the effect of test time on caregiving scores is significant (F=89.142; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.761). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of the caregiving burden in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. Also, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of caregiving burden in the test and control groups regardless of the test time (F=33.321; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.543). Moreover, based on the interaction between the group and the measurement time, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of caregiving burden in the test and control groups in the pre-test, post-test and follow-up stages (F=95.967; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.774).

According to Bonferroni post hoc test results, the difference of the pre-test scores with post-test and follow-up scores was significant at P<0.001 level which indicates the effect of the remote mindfulness training on the reduction of anxiety, depression, and caregivers’ burden. A little difference was observed between post-test and follow-up scores indicating that the effect of MBI was sustainable and did not diminish.

4. Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated a significant difference in the post-test scores of anxiety and caregiving burden between the test and control groups. Therefore, MBI through web conferencing has reduced the anxiety and burden of the caregivers of MS patients. According to the findings, there was a significant difference between the test and control groups after the intervention in terms of anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies, such as Cavalera et al. (2016), Pagnini (2016), Bijker et al. (2016), Opara & Brola (2017), Marziniak et al. (2018), Dent et al. (2018), Wilz et al. (2017), Moss-Morris et al. (2012), Salehi Nejad et al. (2017), and Goodarzian (2016) who reported that anxiety, depression and burden of the caregivers of MS patients reduced by means of Internet-based MBI. They concluded that telemedicine and online mindfulness training, as a mediating factor, played an important role in reducing the symptoms and led to positive outcomes when used by the patients.

The mean scores of depression decreased in the post-test but the difference was not significant. This finding can be explained by the low depression score of caregivers in the pre-test in the test and control groups. It means that they did not obtain high depression scores in BDI at pre-test. However, in the MBI (test) group, the mean scores decreased, though this decrease was not significant.

To explain the reduction of depression after MBI, it can be said that the mindfulness through emotional regulation reduces the rumination of depression. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy provides a different way of dealing with emotions and distress. Ignoring negative thoughts, a person does not engage in mental ruminations (Kahrizi, Taghavi, Ghasemi, & Goodarzi, 2017). After mindfulness training, people realize the connection between thoughts, feelings, and body sensations at any time (Mohamadkhani & Tamanayifar, 2005).

Based on this awareness, thoughts and depressive states are detected and by accepting these thoughts, depression gradually decreases. Effective mechanisms of mindfulness such as exposure, cognitive change, self-management, relaxation, and acceptance also reduce symptoms of depression (Omidi & Mohamadkhani, 2008). In other words, people learn to be aware of their physical states, feelings, and thoughts at the moment. During the training, the physical and mental defects are identified; the person learns to be aware of these thoughts and feelings, and instead of their rejection or control, accept them and keep in the present moment.

This acceptance reduces the negative burden of these states and prevents the development of symptoms and, subsequently, anxiety and depression. Because of the exercises of mindfulness and being in the moment and awareness of bodily sensations and psychological feelings, the subjects notice their heart rate and respiration rate changes when they feel anxiety. As a result, they focus more on the body which increases the awareness of the body, feelings, and thoughts associated with the anxiety. This awareness increases the sense of control over symptoms and subsequently leads to anxiety reduction.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and being in the moment is an effective way to reduce the anxiety and depression of caregivers. They learn to recognize physical states, especially their respiratory status, and if they feel breathless due to psychological factors such as anxiety and depression, they can control it by meditation such as a 3-minute breathing space and other breathing-focused exercises. The results of this study showed decreased anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden after 8 sessions of MBI which is in agreement with these findings.

Considering the previous efforts where new telecommunication technologies were applied to support psychological interventions (Omidi & Mohamadkhani, 2008; Eichenberg & Ott, 2012), in this study, MBI was provided for caregivers of patients with MS remotely via an online application which could create the possibility of meditation at home to improve their anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden. Review of the literature can find studies which indicate that meditation improves the mental well-being of MS patients and their caregivers (Grossman et al., 2010); however, meditation cannot always be possible due to practical reasons (e.g. occupational activities) or physical constraints.

The caregivers of MS patients often suffer from mental illness. Few studies have examined the impact of psychological interventions on them. This study allows us to examine whether this treatment method can improve their quality of life. This intervention provides the ability to easily access to online resources which can be an evidence-based approach to improve the quality of life of MS patients and their caregivers. This protocol describes the development of a mindfulness-based intervention and its feasibility using a randomized controlled design.

The first limitation of this research was related to its virtual nature. Using online platforms in Iran is new and users (the caregivers of MS patients) may not be familiar with using it, and they have to be trained before the program starts. Another limitation was the lack of a follow-up period of more than one month because of time constraints. It is suggested that a longer follow-up period be used to evaluate the continuation of treatment outcomes in future studies. the villages and deprived areas should be equipped with high-speed Internet.

In this regard, medical teams, medical centers or universities should be ready to coordinate and provide systematic online services. Because of the importance of privacy and confidentiality, a special online security system should be designed for people using online communication methods with proper ethical protocols to protect them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This article was extracted from a PhD. thesis of Mahnaz Khazaeili in Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Qom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (1984 Views)

1. Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is one of the common diseases of the autoimmune system. According to studies, MS patients and their families suffer from a wide range of mental problems such as stress, anxiety, depression, and mood disorders. The inadequate training and support of the caregivers of MS patients is an important factor in creating stress and anxiety among these caregivers. Caring chronic patients creates psychological, physical and social stresses for the caregivers and eventually will end in burn out, anxiety, and depression (Pahlavanzadeh, Dalvi-Isfahani, Alimohammadi, & Chitsaz, 2015).

Families of the patients with MS, because of the long-term care of their patients and bearing a lot of psychological pressure, are vulnerable and need special attention. Owning to the unpredictable nature of MS, the age of onset, and its progressive course, caregivers often feel a lot of stress and discomfort. Caring for these patients can have a negative impact on many aspects of caregivers such as physical and mental health, professional life, financial situation, social communication, relationships between individuals and marital life. According to the studies examining psychological aspects, caregivers experience a higher degree of anxiety and depression compared to normal people (Opara & Brola, 2017).

E-health technology helps improve the quality of care services. Since the Internet is available everywhere via smartphones and other devices, most people can use it at hand. The digital applications and telecommunication technology for MS patients and their caregivers have advanced so much in recent years. These applications aim at assisting conventional paraclinical methods and can have significant benefits for patients, their caregivers, and healthcare providers. These benefits are important because MS requires ongoing treatment and monitoring (Marziniak et al., 2018).

Distance learning can be considered as a systematic process for providing training to learners in their workplaces or houses at any time and place, by using various media. Information and communication technology have undoubtedly led to widespread developments in all social and economic aspects of humanity. Moreover, its vast application and influence in various aspects of today and future life of human societies have become one of the most important issues of the world (Gharabaghi & Talaei Mashoof, 2009).

Remote therapy, telemental health applications, or internet-based psychotherapy, is a form of psychotherapy or psychological-related practice in which a trained psychotherapist contacts with a client or patient via telephone, cell phone, the Internet, or other electronic media in addition to conventional face-to-face psychotherapy. Remote therapy can overcome some of the barriers to psychological treatment. Telephone interventions have some benefits as they are accessible to everyone and easy to work with. This creates an opportunity for people who may not have access to personal care (Hailey, Ohinmaa, Roine, & Bulger, 2008).

Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) is a stress-relief technique that reduces the cognitive function, the burden of symptoms, and improves the quality of life for both MS patients and their relatives. Non-attendant treatments are beneficial because face-to-face treatments may be associated with some problems such as long distances, and patients’ physical and motor problems that make it hard to attend all treatment sessions. Remote intervention is for preventing commuting problems, providing better accessing, and reducing treatment costs (Frontario, Feld, Sherman, Krupp, & Charvet, 2016).

MBI by using web-based applications can reduce anxiety and stress, and improve health. According to studies, MBI can improve the psychological health of MS patients and their caregivers, and reduce their psychological pains. Telemedicine MBI by using electronic applications like web conferencing can decrease the caregivers’ burden (Cavalera, Pagnini, Rovaris, & Mendozzi, 2016). According to the literature, some studies have already been conducted on telemedicine via communication technology (Shirazi, Hakim Shooshtari, Shalbafan, Hadi, & Bidaki, 2017; Esmaeilzadeh, 2016; Hosseini, Moghaddasi, Asadi, & Karimi; 2012; Ahmadi, 2018) and face to face mindfulness-based interventions (Farhadi & Pasandideh, 2018; Izadi, & Neamat Tavousi, 2017; Ahmadi-shooli, Feily, & Behzadipour, 2016) in Iran. However, lack of studies on internet-based mindfulness interventions for MS patients and their caregivers is noticeable.

According to Kabat-Zinn (1990), mindfulness means “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally”. Segal, Teasdale, and Williams (2002) used mindfulness-based therapy in an 8-session program to bolster recovery from depression and prevent its relapse. They reported that higher mindfulness was associated with a variety of health outcomes such as pain relief, as well as less anxiety, depression, pathological eating, and stress. It can help people stop obsessive thoughts, habits and unhealthy behavioral patterns, and thus play an important role in regulating behavior. Many psychopathology and psychotherapy theories have discussed the importance of awareness, presence, and observation in mental health.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy presented by Segal et al. (2002), is a combination of meditation, yoga, and cognitive therapy to help people gain awareness of mild states of sadness and prevent them from spiraling out of control. It is based on meditation exercises for the presence of the mind. This indicates that patients with MS, in addition to treatments that target primary symptoms, need to deal with other problems that require stronger mental health (Aghabagheri, Mohammadkhani, Omrani, & Farahmand, 2012).

In traditional cognitive therapy, the content of irrational thoughts is explored to change them. When trying to change the content of thoughts, the relationship of individuals with their thoughts may also be affected. Overall, recognizing negative thoughts help people to change their view of negative thoughts and feelings. Various studies have supported the efficacy of MBI. For example, in a randomized controlled trial study in Italy (Cavalera, Rovaris, & Mendozzi, 2017), the researchers investigated the impact of an MS-specific telemedicine meditation intervention on the quality of life of people with MS and their caregivers. This trial recruited 120 patients with relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive MS and their caregivers to participate in a 2-month intervention. The patients underwent assessments of quality of life, anxiety, depression, quality of sleep, mindfulness and fatigue levels conducted at baseline, at week 8 (conclusion of the intervention) and at week 27 (6 months follow-up).

The caregivers completed assessments conducted at the same time points for the same areas, plus caregivers’ burden. The intervention condition consisted of 2 h/wk of online meditation in a group setting led by a trainer, plus 1 h/wk of individual exercises. The control condition incorporated a psycho-education online program and required the same contact time commitment as the intervention condition. The results included improved quality of life, a decrease of anxiety and depression, attaining mindfulness level, a decrease of sleep disturbance and fatigue in patients with MS and their caregivers and decrease of caregivers’ burden.

In another similar study, the impact of a telemedicine MBI on the quality of life of people with MS was investigated. The results showed a reduction in sleep disturbances and a better quality of life both in the patients with MS and their caregivers (Pagnin, 2016). Moss-Morris et al. (2012) in their Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) reported that cognitive behavior therapy was an effective treatment for MS fatigue. An Internet-based version of this intervention, MS Invigor8, was developed for the current study using agile design and input from MS patients. MS Invigor8 includes eight tailored, interactive sessions. The aim was to test the feasibility, potential efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of the program in a pilot RCT. A total of 40 patients were randomized to MS Invigor8 (n=23) group or standard care (n=17) group.

The MS Invigor8 group accessed sessions over 8-10 weeks and received up to three 30-60 min telephone support sessions. The participants completed online standardized questionnaires assessing fatigue, mood, quality of life and service use at baseline and 10 weeks follow-up. A large difference was found between group treatment effects for the primary outcomes of fatigue severity (d=1.19) and impact (d=1.02). The MS Invigor 8 group also reported significantly greater improvements in anxiety, depression, and quality-adjusted life years. These results suggest that Internet-based CBT may be a clinically and cost-effective treatment for MS fatigue. A larger RCT with longer-term follow-up is warranted.

Salehi Nejad, Azami, Motamedi, Sedighi, and Shahesmaili (2017) reported that because of the relatively high rate of psychological problems among caregivers of patients with dementia, they need necessary information about this disease and the methods of caregiving. Their study aimed to improve caregivers’ awareness of this disease in order to improve their performance, the quality of patients’ care, and to reduce their stress through the provision of web-based health information. This clinical trial used intervention and control groups.

The sample size was calculated as 25 in each group (total=50). First, the subjects were selected through purposive sampling method and were randomly assigned into the test and control groups. Then, a pre-test was carried out using knowledge and care scale questionnaires. In the next step, through a website designed for this purpose, the health information related to the disease was provided to caregivers in 12 sessions within two months. At the end of the intervention, a post-test was given to both groups and the results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. According to the obtained results, the mean score of caregivers’ burden showed no significant change in the control group and, even, showed a little increase (0.53). While, in the test group, it decreased by 13.58 points. Thus, the provision of web-based health information was effective in reducing the burden of caregivers of patients with dementia.

Ershad Sarabi et al. (2018) reported that mobile technology provided new opportunities for health care systems. Improvement of health services outcomes in different patient groups is one of the benefits of using this tool. Although the use of mobile in Iran is expanding, there is no evidence of using this technology in Iran health system. The aim of their study was to review the published research on the application of mHealth in the health system of Iran. In order to carry out a review study, PubMed database was searched by the keyword “Mobile Health” and its equivalents which have derived from the “Medical Subject Headings”. Iranian databases, including IranMedex, Magiran and Scientific Information Database (SID) were also searched for Persian and English terms of mobile health. Retrieval citations from information databases were fed to the EndNote and evaluated based on the study criteria.

The research sample consisted of 26 articles that met the inclusion criteria. In most studies, text messaging was the main intervention tool for mHealth. The results indicated a significant effect of mobile health in improving the patients’ care. In Iran, mobile health can be effectively used in the health system due to its popularity and geographic spread. According to the results of this study, the use of mobile health, especially in educating patients for self-care and preventing the spread of diseases, can be very effective.

Internet-based mindfulness-training and cognitive-behavior training with telephone support hold promising in improving the mental health among college students and young working adults (Mak, Chio, Chan, Lui, & Wu, 2017). In a study in the Netherlands, an online intervention for nonprofessional caregivers of patients with depression was performed (called E-care 4 caregivers) (Bijker, Kleiboer, Riper, Cuijpers, & Donker, 2016). It was a cost-effective intervention, and relatively easy to implement in general health care to reduce costs and increase availability (Dent et al., 2018). It presented a TeleHealth solution that included proactive and targeted patient identification, engagement, and nationwide delivery of a technology-enabled, standardized, and evidence-based behavioral health program delivered via phone or video. Before and after the evaluation of the program, it showed national reach, high patients’ satisfaction, and significant reductions in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. A telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia increased their mental and physical health as well as coping abilities (Wilz, Reder, Meichsner, & Soellner, 2017).

Marziniak et al. (2018) argued that digital applications and remote communication technology for patients with MS increased rapidly in recent years for reasons such as mobility restrictions, travel costs, consultation and treatment time constraints, and a lack of locally available MS expert services. Mahmoodi, Mohammad Khani, Ghobari Banab, and Bagheri (2016) reported that group cognitive-behavioral therapy could increase the use of compatible strategies for coping with stress and decrease the use of incompatible strategies. They recommended using group cognitive behavioral therapy as a low-cost treatment for the family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease or other chronic diseases.

Jahanbakhshian and Zahrakar (2018) examined the effect of participation of caregivers of MS patients in group supportive-training therapy on the improvement of patients’ mental health (decrease of depression and anxiety, and increase of positive feelings). Their results showed that the supportive-training intervention for caregivers of MS patients was dramatically effective on the patients’ mental health. Firoozy and Ramezani Piyani (2018) reported that positive psychological interventions based on virtual social networks were effective on the anxiety and depression reduction in patients with spinal cord injury. In another study, the effectiveness of remote nursing through telephone consultation on the rate of depression and anxiety in the family caregivers of patients with stroke was investigated (Goodarzian, 2016). The caregivers receiving telephone counseling demonstrated lower levels of anxiety.

Given that the problems of MS patients significantly affect the mental health of them and their caregivers, and considering difficulties in using face-to-face treatments and availability of communication technology, especially Internet in the field of psychology and psychotherapy, these interventions can be conducted remotely using the Internet-based applications. So far, psychological interventions have not been conducted with the help of the Internet for MS patients and their caregivers in Iran. In this regard, this study aimed to investigate the effect of the Internet-based mindfulness training on anxiety, depression, and burden of caregivers of patients with MS.

2. Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with pre-test-post-test and a control group. The independent variable was remote MBI, and dependent variables were anxiety, depression, and burden of caregivers. The study population consisted of caregivers of female patients with Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) who were covered by the Iranian MS Society in Tehran and Qom cities, Iran in 2017. Of them, 30 were selected using purposeful sampling method. For sampling, first, the documents and an introduction letter were presented to the director and research department of the MS Society in Tehran and Qom. Then, the researchers participated in one of the patients’ rounds and a form containing questions about demographic information, anxiety and depression records, and study inclusion criteria were given to them to complete. Since the ideal sample size in a study with experimental design is 15 (Biyabangard, 2011), 15 eligible patients were selected from Tehran and 15 from Qom (total sample size=30).

They were randomly assigned to test and control groups. The inclusion criteria for the caregivers were living with the patient, having ability to communicate and understand tasks, having relatively high-speed Internet access with a personal computer or mobile phone; having enough literacy, and being 20-70 years old. Moreover, the exclusion criteria were having severe physical problems such as heart disease, having mental illness and addiction, failure to communicate and understand the tasks, lacking access to the Internet, computer, tablet or mobile phone; and unwilling to participate in the sessions.

The caregivers of the patients in the test group were invited to attend a meeting at the MS Society in Tehran and Qom. In this meeting, after getting acquainted and giving informed consent and being assured of study confidentiality, they were informed about the process and objectives of an 8-week mindfulness-based program. They were told that they would be added to a group in the Telegram application in order to receive educational notes and audio files. In the pre-test phase, the questionnaires were sent via Telegram to the caregivers of patients in both groups at the same time, and they were sent them back after completion. The caregivers of the patients in the control group received no intervention. Both groups filled out the questionnaires at the same time one week after the end of the intervention (post-test phase). A follow-up study was conducted one month after the implementation of the post-test.

The independent variable was remote MBI, and dependent variables were anxiety, depression, and burden of the caregivers. For gathering data from the literature, library method was used and data from the participants gathered online via Telegram. Adobe Connect V. 9.6 was the used web conferencing application with its many advantages. It can simultaneously connect up to 30 users, and establish hours of video and audio communications without being disconnected. Many universities in Iran use this application. The caregivers of the patients in the control group received no intervention. Again, all groups filled out the questionnaires at the same time one week after the end of the intervention (post-test phase). A follow-up study was conducted one month after the implementation of the post-test.

Beck Anxiety Inventory, Second Edition (BAI-II) has 21 items exploring common symptoms of anxiety (mental, physical and panic-related) based on a 4-point Likert-type scale rated from 0 to 3 (0=not at all, 1=mildly, 2=moderately, 3=severely). The total score for all items can range between 0 and 63 points. A total score of 0-7 is interpreted as a “Minimal” level of anxiety; 8 -15 as “Mild”; 16-25 as “Moderate”, and; 26-63 as “Severe”.

According to studies, this questionnaire has high reliability and validity. Its internal consistency coefficient has been reported as 0.92, and its test-retest reliability with a one-week interval was 0.75, and the correlation of its items varied from 0.30 to 0.70. Five types of content validity, concurrent validity, construct validity, diagnostic validity, and Beck anxiety scale factor have supported the effectiveness of this tool for the Iranian population. Kaviani and Mousavi reported its internal consistency coefficient as 0.72; test-retest reliability with a one-month interval as 0.83, and a Cronbach α of 0.92. The reliability of this tool has been reported from 0.80 to 0.92. In a study on Iranian students, the reliability of this questionnaire was reported as 0.92 using the Cronbach α (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988; Beck & Steer, 1990; Karamoozian, Askarizadeh, & Darekordi, 2017)

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II) is a 21-item self-report inventory for measuring the severity of depression. It is based on a 4-point Likert-type scale rated from 0 to 3 (0=not at all, 1=mildly, 2=moderately, 3= severely). The total score ranges between 0 and 63 points; the highest score indicates a severe level of depression. Its reliability and validity have been confirmed in several studies. Beck et al. reported its internal consistency from 0.73 to 0.92 based on the Cronbach α, and the coefficients of its test-retest reliability were from 0.48 to 0.68. The correlation coefficient of BDI with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is 0.73.

The results of a meta-analysis on the BDI show that its internal consistency coefficient ranges from 0.73 to 0.93 with an average of 0.86. Ghassemzadeh, Mojtabai, Karamghadiri, and Ebrahimkhani (2005) reported that the Cronbach α coefficient of BDI for normal subjects ranged from 0.85 to 0.92, and for a sample of patients was from 0.83 to 0.91 indicating good internal consistency. The correlation coefficients between the scores of normal and patient subjects for measuring test-retest reliability were obtained as 0.81 and 0.79, respectively. The recommended cutoff point in this test for minimal depression is 0 to 13; for mild depression as 14 to 19; for moderate depression as 20 to 28; and for severe depression as 29 to 63 (Fathi Ashtiani, 2011).

The Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) designed by Novak and Guest (1988), consists of 24 items based on 5-point Likert-type scale for evaluating the caregivers’ burden. It measures five subscales: 1. Time dependence (the burden on caregiver due to restriction on the caregivers’ time); 2. Developmental (the caregivers’ feeling of being left behind, incapable of enjoying the same expectations and opportunities as their peers); 3. Physical burden (feelings of chronic fatigue and physical health problems); 4. Social burden (describe caregivers’ sense of perceived conflict of roles); and 5. Emotional burden (caregivers’ negative feelings toward their patient, which can be induced by the patient’s bizarre and unpredictable behavior). Subscales number 1, 2, 4, and 5 have five items, while subscale 3 has four items (Fleisher et al., 2016).

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) is a 39-item inventory designed by Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, and Toney (2006). measuring tendency to be mindful in daily life. It is based on exploratory factor analysis of items from five independently developed self-report mindfulness scales: 1. Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003); 2. Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmüller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006); 3. Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale (Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007); 4. Mindfulness Questionnaire (Chadwick, Taylor, & Abba, 2005); and 5. Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (Baer et al., 2008). It consists of five related dimensions: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience. Observing refers to attending or noticing internal and external experiences (e.g. sounds, emotions, thoughts, bodily sensations, smells).

Describing includes the ability to express experiences in one’s words. Acting with awareness involves attending to one’s present moment activity, rather than being on “autopilot”, or behaving automatically, while attention is focused elsewhere. Non-judging of inner experience involves accepting and not evaluating thoughts and emotions. Finally, non-reactivity to inner experience refers to the ability to detach from thoughts and emotions, allowing them to come and go without getting involved or be carried away by them (Brown, Kasser, Linley, & Ryan, 2009). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true).

The internal consistency of the factors has been reported as appropriate. The α value ranges from 0.75 (for non-reactivity factor) to 0.91 (for describing factor). The correlation between the factors is moderate, and for all items, it has been reported as significant in a range between 0.15 and 0.34. In a study conducted on the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Iran, the test-retest correlation coefficients of the questionnaire for the Iranian samples were reported between 0.57 (for non-judging dimension) and 0.84 (for observational factor). The α coefficients were also found to be within the acceptable range (between 0.55 for non-reactivity and 0.83 for describing factors). By summing up the scores for each factor, a total score is obtained where higher scores indicate a higher tendency to be mindful in life.

Web Conferencing Software: nowadays, because of significant advances in the field of information technology in the world and the Internet infrastructure improvements in Iran, we can participate in seminars, events, conferences and scientific meetings while spending less time and money and without suffering traffic or geographical constraints. In other words, we can get benefit from the knowledge of these events with the lowest cost and highest effectiveness. There are many online tools for hosting classes, seminars, and events. One of these tools is a web-based video conference, or the so-called “webinar”, through which we can participate live in various seminars and events from home.

No matter where you are, you only need to have access to the Internet. Webinar or web-based seminar is a seminar that is transmitted over the web where a lot of people, by the webinar host’s invitation, (online users) can simultaneously enter the webinar environment online and start the discussion, share slides, ask questions (in text, audio or video format) and promptly receive their answers from the host. In general, the webinar includes anything you expect to see in classrooms, seminars or other business or educational events remotely over the Internet with high speed.

The Package of Mindfulness Intervention (MBI) included an 8-session (2 hours per session) program (a combination of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction) provided remotely via web conferencing. The MBI program included these sessions: 1. Identification of autopilot and breaking out of it, mindfulness of daily activities, and body scan; 2. Dealing with barriers, reaction to daily events, preparing a list of enjoyable activities, and a 10-min sitting meditation; 3. Awareness of thought, gathering attention, 40-min breathing-focused or body-focused sitting meditation, and unpleasant body feelings; 4. Staying at present, attachment, and aversion; 5. Acceptance of individual experiences; 6. Thoughts are not facts; 7. How we can care for ourselves, preparing a list of enjoyable and skillful activities, a list of signs and symptoms of depression, providing an activity plan for coping with depression, practicing how to say goodbye; and 8. Applying what we learned to deal with people in future (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Segal et al., 2002; cited in Mohamadkhani & Khanipore, 2016).

SPSS V. 23 was used to analyze the collected data by performing descriptive statistics such as Mean and SD. Since there were three study dependent variables, for testing research hypotheses and significance of the difference between mean scores, repeated-measures Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used.

3. Results

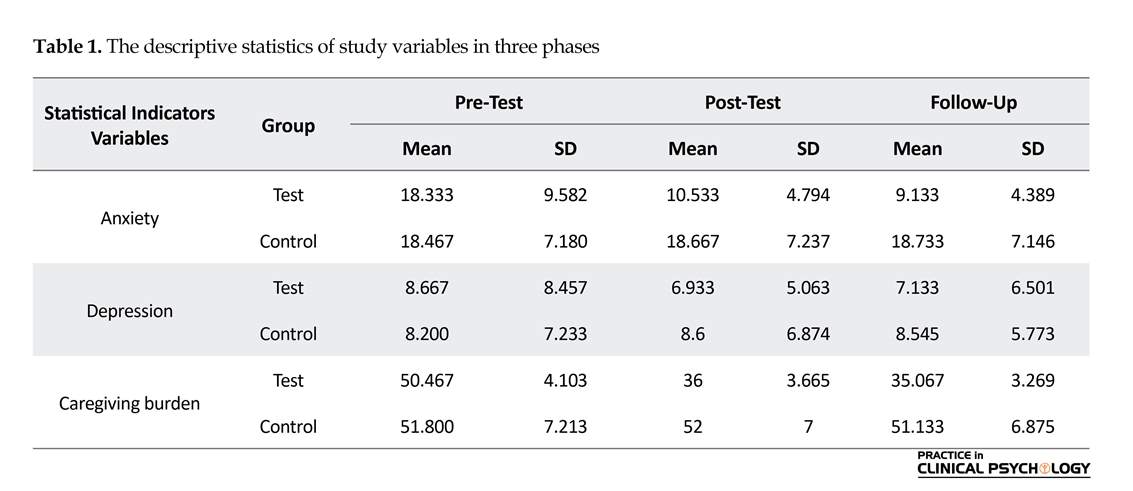

In this section, first, we present descriptive statistics of study variables, and then the inferential statistics. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for anxiety, depression, and caregivers’ burden in three phases of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up. It can be seen that the pre-test mean scores of these variables in the control and test groups were close to each other, indicating the homogeneity of these two groups. It is also observed that the mean scores of all three variables were similar in the control group in all three stages and did not change considerably.

On the contrary, the mean scores in the test group decreased over the study period. The results of the repeated-measures MANOVA test are presented in Table 2. Before the test, the normal distribution assumption was investigated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity by using Levene’s test whose results were confirmatory. Also, the results of Mauchly’s test for testing the assumption of sphericity (equality of the variances of the difference between subjects) showed significant inequality between the variances of the differences; hence, sphericity cannot be assumed. In this regard, for performing repeated-measures MANOVA test, the degree of freedom correction was done and, as the amount of Mauchly’s test statistic was less than 0.751, the Huynh-Feldt adjustment was used.

The results of Table 2 indicate that the effect of test time on anxiety is significant (F=23.008; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.451). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of anxiety over three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. The group influence is also significant (F=5.413; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.162). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean anxiety scores in the test and control groups, irrespective of the test time. Furthermore, the effect of interaction between the group and the test time was significant (F=25.882; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.480). Therefore, there is a significant difference between the mean anxiety of caregivers in both groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is one of the common diseases of the autoimmune system. According to studies, MS patients and their families suffer from a wide range of mental problems such as stress, anxiety, depression, and mood disorders. The inadequate training and support of the caregivers of MS patients is an important factor in creating stress and anxiety among these caregivers. Caring chronic patients creates psychological, physical and social stresses for the caregivers and eventually will end in burn out, anxiety, and depression (Pahlavanzadeh, Dalvi-Isfahani, Alimohammadi, & Chitsaz, 2015).

Families of the patients with MS, because of the long-term care of their patients and bearing a lot of psychological pressure, are vulnerable and need special attention. Owning to the unpredictable nature of MS, the age of onset, and its progressive course, caregivers often feel a lot of stress and discomfort. Caring for these patients can have a negative impact on many aspects of caregivers such as physical and mental health, professional life, financial situation, social communication, relationships between individuals and marital life. According to the studies examining psychological aspects, caregivers experience a higher degree of anxiety and depression compared to normal people (Opara & Brola, 2017).

E-health technology helps improve the quality of care services. Since the Internet is available everywhere via smartphones and other devices, most people can use it at hand. The digital applications and telecommunication technology for MS patients and their caregivers have advanced so much in recent years. These applications aim at assisting conventional paraclinical methods and can have significant benefits for patients, their caregivers, and healthcare providers. These benefits are important because MS requires ongoing treatment and monitoring (Marziniak et al., 2018).

Distance learning can be considered as a systematic process for providing training to learners in their workplaces or houses at any time and place, by using various media. Information and communication technology have undoubtedly led to widespread developments in all social and economic aspects of humanity. Moreover, its vast application and influence in various aspects of today and future life of human societies have become one of the most important issues of the world (Gharabaghi & Talaei Mashoof, 2009).

Remote therapy, telemental health applications, or internet-based psychotherapy, is a form of psychotherapy or psychological-related practice in which a trained psychotherapist contacts with a client or patient via telephone, cell phone, the Internet, or other electronic media in addition to conventional face-to-face psychotherapy. Remote therapy can overcome some of the barriers to psychological treatment. Telephone interventions have some benefits as they are accessible to everyone and easy to work with. This creates an opportunity for people who may not have access to personal care (Hailey, Ohinmaa, Roine, & Bulger, 2008).

Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) is a stress-relief technique that reduces the cognitive function, the burden of symptoms, and improves the quality of life for both MS patients and their relatives. Non-attendant treatments are beneficial because face-to-face treatments may be associated with some problems such as long distances, and patients’ physical and motor problems that make it hard to attend all treatment sessions. Remote intervention is for preventing commuting problems, providing better accessing, and reducing treatment costs (Frontario, Feld, Sherman, Krupp, & Charvet, 2016).

MBI by using web-based applications can reduce anxiety and stress, and improve health. According to studies, MBI can improve the psychological health of MS patients and their caregivers, and reduce their psychological pains. Telemedicine MBI by using electronic applications like web conferencing can decrease the caregivers’ burden (Cavalera, Pagnini, Rovaris, & Mendozzi, 2016). According to the literature, some studies have already been conducted on telemedicine via communication technology (Shirazi, Hakim Shooshtari, Shalbafan, Hadi, & Bidaki, 2017; Esmaeilzadeh, 2016; Hosseini, Moghaddasi, Asadi, & Karimi; 2012; Ahmadi, 2018) and face to face mindfulness-based interventions (Farhadi & Pasandideh, 2018; Izadi, & Neamat Tavousi, 2017; Ahmadi-shooli, Feily, & Behzadipour, 2016) in Iran. However, lack of studies on internet-based mindfulness interventions for MS patients and their caregivers is noticeable.

According to Kabat-Zinn (1990), mindfulness means “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally”. Segal, Teasdale, and Williams (2002) used mindfulness-based therapy in an 8-session program to bolster recovery from depression and prevent its relapse. They reported that higher mindfulness was associated with a variety of health outcomes such as pain relief, as well as less anxiety, depression, pathological eating, and stress. It can help people stop obsessive thoughts, habits and unhealthy behavioral patterns, and thus play an important role in regulating behavior. Many psychopathology and psychotherapy theories have discussed the importance of awareness, presence, and observation in mental health.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy presented by Segal et al. (2002), is a combination of meditation, yoga, and cognitive therapy to help people gain awareness of mild states of sadness and prevent them from spiraling out of control. It is based on meditation exercises for the presence of the mind. This indicates that patients with MS, in addition to treatments that target primary symptoms, need to deal with other problems that require stronger mental health (Aghabagheri, Mohammadkhani, Omrani, & Farahmand, 2012).

In traditional cognitive therapy, the content of irrational thoughts is explored to change them. When trying to change the content of thoughts, the relationship of individuals with their thoughts may also be affected. Overall, recognizing negative thoughts help people to change their view of negative thoughts and feelings. Various studies have supported the efficacy of MBI. For example, in a randomized controlled trial study in Italy (Cavalera, Rovaris, & Mendozzi, 2017), the researchers investigated the impact of an MS-specific telemedicine meditation intervention on the quality of life of people with MS and their caregivers. This trial recruited 120 patients with relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive MS and their caregivers to participate in a 2-month intervention. The patients underwent assessments of quality of life, anxiety, depression, quality of sleep, mindfulness and fatigue levels conducted at baseline, at week 8 (conclusion of the intervention) and at week 27 (6 months follow-up).

The caregivers completed assessments conducted at the same time points for the same areas, plus caregivers’ burden. The intervention condition consisted of 2 h/wk of online meditation in a group setting led by a trainer, plus 1 h/wk of individual exercises. The control condition incorporated a psycho-education online program and required the same contact time commitment as the intervention condition. The results included improved quality of life, a decrease of anxiety and depression, attaining mindfulness level, a decrease of sleep disturbance and fatigue in patients with MS and their caregivers and decrease of caregivers’ burden.

In another similar study, the impact of a telemedicine MBI on the quality of life of people with MS was investigated. The results showed a reduction in sleep disturbances and a better quality of life both in the patients with MS and their caregivers (Pagnin, 2016). Moss-Morris et al. (2012) in their Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) reported that cognitive behavior therapy was an effective treatment for MS fatigue. An Internet-based version of this intervention, MS Invigor8, was developed for the current study using agile design and input from MS patients. MS Invigor8 includes eight tailored, interactive sessions. The aim was to test the feasibility, potential efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of the program in a pilot RCT. A total of 40 patients were randomized to MS Invigor8 (n=23) group or standard care (n=17) group.

The MS Invigor8 group accessed sessions over 8-10 weeks and received up to three 30-60 min telephone support sessions. The participants completed online standardized questionnaires assessing fatigue, mood, quality of life and service use at baseline and 10 weeks follow-up. A large difference was found between group treatment effects for the primary outcomes of fatigue severity (d=1.19) and impact (d=1.02). The MS Invigor 8 group also reported significantly greater improvements in anxiety, depression, and quality-adjusted life years. These results suggest that Internet-based CBT may be a clinically and cost-effective treatment for MS fatigue. A larger RCT with longer-term follow-up is warranted.

Salehi Nejad, Azami, Motamedi, Sedighi, and Shahesmaili (2017) reported that because of the relatively high rate of psychological problems among caregivers of patients with dementia, they need necessary information about this disease and the methods of caregiving. Their study aimed to improve caregivers’ awareness of this disease in order to improve their performance, the quality of patients’ care, and to reduce their stress through the provision of web-based health information. This clinical trial used intervention and control groups.

The sample size was calculated as 25 in each group (total=50). First, the subjects were selected through purposive sampling method and were randomly assigned into the test and control groups. Then, a pre-test was carried out using knowledge and care scale questionnaires. In the next step, through a website designed for this purpose, the health information related to the disease was provided to caregivers in 12 sessions within two months. At the end of the intervention, a post-test was given to both groups and the results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. According to the obtained results, the mean score of caregivers’ burden showed no significant change in the control group and, even, showed a little increase (0.53). While, in the test group, it decreased by 13.58 points. Thus, the provision of web-based health information was effective in reducing the burden of caregivers of patients with dementia.

Ershad Sarabi et al. (2018) reported that mobile technology provided new opportunities for health care systems. Improvement of health services outcomes in different patient groups is one of the benefits of using this tool. Although the use of mobile in Iran is expanding, there is no evidence of using this technology in Iran health system. The aim of their study was to review the published research on the application of mHealth in the health system of Iran. In order to carry out a review study, PubMed database was searched by the keyword “Mobile Health” and its equivalents which have derived from the “Medical Subject Headings”. Iranian databases, including IranMedex, Magiran and Scientific Information Database (SID) were also searched for Persian and English terms of mobile health. Retrieval citations from information databases were fed to the EndNote and evaluated based on the study criteria.

The research sample consisted of 26 articles that met the inclusion criteria. In most studies, text messaging was the main intervention tool for mHealth. The results indicated a significant effect of mobile health in improving the patients’ care. In Iran, mobile health can be effectively used in the health system due to its popularity and geographic spread. According to the results of this study, the use of mobile health, especially in educating patients for self-care and preventing the spread of diseases, can be very effective.

Internet-based mindfulness-training and cognitive-behavior training with telephone support hold promising in improving the mental health among college students and young working adults (Mak, Chio, Chan, Lui, & Wu, 2017). In a study in the Netherlands, an online intervention for nonprofessional caregivers of patients with depression was performed (called E-care 4 caregivers) (Bijker, Kleiboer, Riper, Cuijpers, & Donker, 2016). It was a cost-effective intervention, and relatively easy to implement in general health care to reduce costs and increase availability (Dent et al., 2018). It presented a TeleHealth solution that included proactive and targeted patient identification, engagement, and nationwide delivery of a technology-enabled, standardized, and evidence-based behavioral health program delivered via phone or video. Before and after the evaluation of the program, it showed national reach, high patients’ satisfaction, and significant reductions in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. A telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia increased their mental and physical health as well as coping abilities (Wilz, Reder, Meichsner, & Soellner, 2017).

Marziniak et al. (2018) argued that digital applications and remote communication technology for patients with MS increased rapidly in recent years for reasons such as mobility restrictions, travel costs, consultation and treatment time constraints, and a lack of locally available MS expert services. Mahmoodi, Mohammad Khani, Ghobari Banab, and Bagheri (2016) reported that group cognitive-behavioral therapy could increase the use of compatible strategies for coping with stress and decrease the use of incompatible strategies. They recommended using group cognitive behavioral therapy as a low-cost treatment for the family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease or other chronic diseases.

Jahanbakhshian and Zahrakar (2018) examined the effect of participation of caregivers of MS patients in group supportive-training therapy on the improvement of patients’ mental health (decrease of depression and anxiety, and increase of positive feelings). Their results showed that the supportive-training intervention for caregivers of MS patients was dramatically effective on the patients’ mental health. Firoozy and Ramezani Piyani (2018) reported that positive psychological interventions based on virtual social networks were effective on the anxiety and depression reduction in patients with spinal cord injury. In another study, the effectiveness of remote nursing through telephone consultation on the rate of depression and anxiety in the family caregivers of patients with stroke was investigated (Goodarzian, 2016). The caregivers receiving telephone counseling demonstrated lower levels of anxiety.

Given that the problems of MS patients significantly affect the mental health of them and their caregivers, and considering difficulties in using face-to-face treatments and availability of communication technology, especially Internet in the field of psychology and psychotherapy, these interventions can be conducted remotely using the Internet-based applications. So far, psychological interventions have not been conducted with the help of the Internet for MS patients and their caregivers in Iran. In this regard, this study aimed to investigate the effect of the Internet-based mindfulness training on anxiety, depression, and burden of caregivers of patients with MS.

2. Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with pre-test-post-test and a control group. The independent variable was remote MBI, and dependent variables were anxiety, depression, and burden of caregivers. The study population consisted of caregivers of female patients with Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) who were covered by the Iranian MS Society in Tehran and Qom cities, Iran in 2017. Of them, 30 were selected using purposeful sampling method. For sampling, first, the documents and an introduction letter were presented to the director and research department of the MS Society in Tehran and Qom. Then, the researchers participated in one of the patients’ rounds and a form containing questions about demographic information, anxiety and depression records, and study inclusion criteria were given to them to complete. Since the ideal sample size in a study with experimental design is 15 (Biyabangard, 2011), 15 eligible patients were selected from Tehran and 15 from Qom (total sample size=30).

They were randomly assigned to test and control groups. The inclusion criteria for the caregivers were living with the patient, having ability to communicate and understand tasks, having relatively high-speed Internet access with a personal computer or mobile phone; having enough literacy, and being 20-70 years old. Moreover, the exclusion criteria were having severe physical problems such as heart disease, having mental illness and addiction, failure to communicate and understand the tasks, lacking access to the Internet, computer, tablet or mobile phone; and unwilling to participate in the sessions.

The caregivers of the patients in the test group were invited to attend a meeting at the MS Society in Tehran and Qom. In this meeting, after getting acquainted and giving informed consent and being assured of study confidentiality, they were informed about the process and objectives of an 8-week mindfulness-based program. They were told that they would be added to a group in the Telegram application in order to receive educational notes and audio files. In the pre-test phase, the questionnaires were sent via Telegram to the caregivers of patients in both groups at the same time, and they were sent them back after completion. The caregivers of the patients in the control group received no intervention. Both groups filled out the questionnaires at the same time one week after the end of the intervention (post-test phase). A follow-up study was conducted one month after the implementation of the post-test.

The independent variable was remote MBI, and dependent variables were anxiety, depression, and burden of the caregivers. For gathering data from the literature, library method was used and data from the participants gathered online via Telegram. Adobe Connect V. 9.6 was the used web conferencing application with its many advantages. It can simultaneously connect up to 30 users, and establish hours of video and audio communications without being disconnected. Many universities in Iran use this application. The caregivers of the patients in the control group received no intervention. Again, all groups filled out the questionnaires at the same time one week after the end of the intervention (post-test phase). A follow-up study was conducted one month after the implementation of the post-test.

Beck Anxiety Inventory, Second Edition (BAI-II) has 21 items exploring common symptoms of anxiety (mental, physical and panic-related) based on a 4-point Likert-type scale rated from 0 to 3 (0=not at all, 1=mildly, 2=moderately, 3=severely). The total score for all items can range between 0 and 63 points. A total score of 0-7 is interpreted as a “Minimal” level of anxiety; 8 -15 as “Mild”; 16-25 as “Moderate”, and; 26-63 as “Severe”.

According to studies, this questionnaire has high reliability and validity. Its internal consistency coefficient has been reported as 0.92, and its test-retest reliability with a one-week interval was 0.75, and the correlation of its items varied from 0.30 to 0.70. Five types of content validity, concurrent validity, construct validity, diagnostic validity, and Beck anxiety scale factor have supported the effectiveness of this tool for the Iranian population. Kaviani and Mousavi reported its internal consistency coefficient as 0.72; test-retest reliability with a one-month interval as 0.83, and a Cronbach α of 0.92. The reliability of this tool has been reported from 0.80 to 0.92. In a study on Iranian students, the reliability of this questionnaire was reported as 0.92 using the Cronbach α (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988; Beck & Steer, 1990; Karamoozian, Askarizadeh, & Darekordi, 2017)

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II) is a 21-item self-report inventory for measuring the severity of depression. It is based on a 4-point Likert-type scale rated from 0 to 3 (0=not at all, 1=mildly, 2=moderately, 3= severely). The total score ranges between 0 and 63 points; the highest score indicates a severe level of depression. Its reliability and validity have been confirmed in several studies. Beck et al. reported its internal consistency from 0.73 to 0.92 based on the Cronbach α, and the coefficients of its test-retest reliability were from 0.48 to 0.68. The correlation coefficient of BDI with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is 0.73.

The results of a meta-analysis on the BDI show that its internal consistency coefficient ranges from 0.73 to 0.93 with an average of 0.86. Ghassemzadeh, Mojtabai, Karamghadiri, and Ebrahimkhani (2005) reported that the Cronbach α coefficient of BDI for normal subjects ranged from 0.85 to 0.92, and for a sample of patients was from 0.83 to 0.91 indicating good internal consistency. The correlation coefficients between the scores of normal and patient subjects for measuring test-retest reliability were obtained as 0.81 and 0.79, respectively. The recommended cutoff point in this test for minimal depression is 0 to 13; for mild depression as 14 to 19; for moderate depression as 20 to 28; and for severe depression as 29 to 63 (Fathi Ashtiani, 2011).

The Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) designed by Novak and Guest (1988), consists of 24 items based on 5-point Likert-type scale for evaluating the caregivers’ burden. It measures five subscales: 1. Time dependence (the burden on caregiver due to restriction on the caregivers’ time); 2. Developmental (the caregivers’ feeling of being left behind, incapable of enjoying the same expectations and opportunities as their peers); 3. Physical burden (feelings of chronic fatigue and physical health problems); 4. Social burden (describe caregivers’ sense of perceived conflict of roles); and 5. Emotional burden (caregivers’ negative feelings toward their patient, which can be induced by the patient’s bizarre and unpredictable behavior). Subscales number 1, 2, 4, and 5 have five items, while subscale 3 has four items (Fleisher et al., 2016).

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) is a 39-item inventory designed by Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, and Toney (2006). measuring tendency to be mindful in daily life. It is based on exploratory factor analysis of items from five independently developed self-report mindfulness scales: 1. Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003); 2. Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmüller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006); 3. Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale (Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007); 4. Mindfulness Questionnaire (Chadwick, Taylor, & Abba, 2005); and 5. Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (Baer et al., 2008). It consists of five related dimensions: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience. Observing refers to attending or noticing internal and external experiences (e.g. sounds, emotions, thoughts, bodily sensations, smells).

Describing includes the ability to express experiences in one’s words. Acting with awareness involves attending to one’s present moment activity, rather than being on “autopilot”, or behaving automatically, while attention is focused elsewhere. Non-judging of inner experience involves accepting and not evaluating thoughts and emotions. Finally, non-reactivity to inner experience refers to the ability to detach from thoughts and emotions, allowing them to come and go without getting involved or be carried away by them (Brown, Kasser, Linley, & Ryan, 2009). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true).

The internal consistency of the factors has been reported as appropriate. The α value ranges from 0.75 (for non-reactivity factor) to 0.91 (for describing factor). The correlation between the factors is moderate, and for all items, it has been reported as significant in a range between 0.15 and 0.34. In a study conducted on the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Iran, the test-retest correlation coefficients of the questionnaire for the Iranian samples were reported between 0.57 (for non-judging dimension) and 0.84 (for observational factor). The α coefficients were also found to be within the acceptable range (between 0.55 for non-reactivity and 0.83 for describing factors). By summing up the scores for each factor, a total score is obtained where higher scores indicate a higher tendency to be mindful in life.

Web Conferencing Software: nowadays, because of significant advances in the field of information technology in the world and the Internet infrastructure improvements in Iran, we can participate in seminars, events, conferences and scientific meetings while spending less time and money and without suffering traffic or geographical constraints. In other words, we can get benefit from the knowledge of these events with the lowest cost and highest effectiveness. There are many online tools for hosting classes, seminars, and events. One of these tools is a web-based video conference, or the so-called “webinar”, through which we can participate live in various seminars and events from home.

No matter where you are, you only need to have access to the Internet. Webinar or web-based seminar is a seminar that is transmitted over the web where a lot of people, by the webinar host’s invitation, (online users) can simultaneously enter the webinar environment online and start the discussion, share slides, ask questions (in text, audio or video format) and promptly receive their answers from the host. In general, the webinar includes anything you expect to see in classrooms, seminars or other business or educational events remotely over the Internet with high speed.

The Package of Mindfulness Intervention (MBI) included an 8-session (2 hours per session) program (a combination of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction) provided remotely via web conferencing. The MBI program included these sessions: 1. Identification of autopilot and breaking out of it, mindfulness of daily activities, and body scan; 2. Dealing with barriers, reaction to daily events, preparing a list of enjoyable activities, and a 10-min sitting meditation; 3. Awareness of thought, gathering attention, 40-min breathing-focused or body-focused sitting meditation, and unpleasant body feelings; 4. Staying at present, attachment, and aversion; 5. Acceptance of individual experiences; 6. Thoughts are not facts; 7. How we can care for ourselves, preparing a list of enjoyable and skillful activities, a list of signs and symptoms of depression, providing an activity plan for coping with depression, practicing how to say goodbye; and 8. Applying what we learned to deal with people in future (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Segal et al., 2002; cited in Mohamadkhani & Khanipore, 2016).

SPSS V. 23 was used to analyze the collected data by performing descriptive statistics such as Mean and SD. Since there were three study dependent variables, for testing research hypotheses and significance of the difference between mean scores, repeated-measures Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used.

3. Results

In this section, first, we present descriptive statistics of study variables, and then the inferential statistics. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for anxiety, depression, and caregivers’ burden in three phases of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up. It can be seen that the pre-test mean scores of these variables in the control and test groups were close to each other, indicating the homogeneity of these two groups. It is also observed that the mean scores of all three variables were similar in the control group in all three stages and did not change considerably.

On the contrary, the mean scores in the test group decreased over the study period. The results of the repeated-measures MANOVA test are presented in Table 2. Before the test, the normal distribution assumption was investigated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity by using Levene’s test whose results were confirmatory. Also, the results of Mauchly’s test for testing the assumption of sphericity (equality of the variances of the difference between subjects) showed significant inequality between the variances of the differences; hence, sphericity cannot be assumed. In this regard, for performing repeated-measures MANOVA test, the degree of freedom correction was done and, as the amount of Mauchly’s test statistic was less than 0.751, the Huynh-Feldt adjustment was used.

The results of Table 2 indicate that the effect of test time on anxiety is significant (F=23.008; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.451). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of anxiety over three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. The group influence is also significant (F=5.413; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.162). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean anxiety scores in the test and control groups, irrespective of the test time. Furthermore, the effect of interaction between the group and the test time was significant (F=25.882; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.480). Therefore, there is a significant difference between the mean anxiety of caregivers in both groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases.

The results related to the depression variable in Table 2 indicate that the effect of test time on depression scores is not significant (F=1.134; Sig.=0.325; η2=0.039). In other words, there is no significant difference between the mean scores of depression in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. Also, the effect of group was not significant (F=0.130; Sig.=0.721; η2=0.005). As a result, there is no significant difference between the mean scores of depression in both groups. Moreover, the effect of interaction between the group and the test time was also not significant (F=3.046; Sig.=0.062; η2=0.098). So, there is no significant difference between the mean depression of caregivers in both groups in the pre-test, post-test and follow-up stages.

The results of the caregiving burden reveals that the effect of test time on caregiving scores is significant (F=89.142; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.761). In other words, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of the caregiving burden in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up regardless of the group factor. Also, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of caregiving burden in the test and control groups regardless of the test time (F=33.321; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.543). Moreover, based on the interaction between the group and the measurement time, there is a significant difference between the mean scores of caregiving burden in the test and control groups in the pre-test, post-test and follow-up stages (F=95.967; Sig.=0.001; η2=0.774).

According to Bonferroni post hoc test results, the difference of the pre-test scores with post-test and follow-up scores was significant at P<0.001 level which indicates the effect of the remote mindfulness training on the reduction of anxiety, depression, and caregivers’ burden. A little difference was observed between post-test and follow-up scores indicating that the effect of MBI was sustainable and did not diminish.

4. Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated a significant difference in the post-test scores of anxiety and caregiving burden between the test and control groups. Therefore, MBI through web conferencing has reduced the anxiety and burden of the caregivers of MS patients. According to the findings, there was a significant difference between the test and control groups after the intervention in terms of anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies, such as Cavalera et al. (2016), Pagnini (2016), Bijker et al. (2016), Opara & Brola (2017), Marziniak et al. (2018), Dent et al. (2018), Wilz et al. (2017), Moss-Morris et al. (2012), Salehi Nejad et al. (2017), and Goodarzian (2016) who reported that anxiety, depression and burden of the caregivers of MS patients reduced by means of Internet-based MBI. They concluded that telemedicine and online mindfulness training, as a mediating factor, played an important role in reducing the symptoms and led to positive outcomes when used by the patients.

The mean scores of depression decreased in the post-test but the difference was not significant. This finding can be explained by the low depression score of caregivers in the pre-test in the test and control groups. It means that they did not obtain high depression scores in BDI at pre-test. However, in the MBI (test) group, the mean scores decreased, though this decrease was not significant.

To explain the reduction of depression after MBI, it can be said that the mindfulness through emotional regulation reduces the rumination of depression. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy provides a different way of dealing with emotions and distress. Ignoring negative thoughts, a person does not engage in mental ruminations (Kahrizi, Taghavi, Ghasemi, & Goodarzi, 2017). After mindfulness training, people realize the connection between thoughts, feelings, and body sensations at any time (Mohamadkhani & Tamanayifar, 2005).

Based on this awareness, thoughts and depressive states are detected and by accepting these thoughts, depression gradually decreases. Effective mechanisms of mindfulness such as exposure, cognitive change, self-management, relaxation, and acceptance also reduce symptoms of depression (Omidi & Mohamadkhani, 2008). In other words, people learn to be aware of their physical states, feelings, and thoughts at the moment. During the training, the physical and mental defects are identified; the person learns to be aware of these thoughts and feelings, and instead of their rejection or control, accept them and keep in the present moment.

This acceptance reduces the negative burden of these states and prevents the development of symptoms and, subsequently, anxiety and depression. Because of the exercises of mindfulness and being in the moment and awareness of bodily sensations and psychological feelings, the subjects notice their heart rate and respiration rate changes when they feel anxiety. As a result, they focus more on the body which increases the awareness of the body, feelings, and thoughts associated with the anxiety. This awareness increases the sense of control over symptoms and subsequently leads to anxiety reduction.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and being in the moment is an effective way to reduce the anxiety and depression of caregivers. They learn to recognize physical states, especially their respiratory status, and if they feel breathless due to psychological factors such as anxiety and depression, they can control it by meditation such as a 3-minute breathing space and other breathing-focused exercises. The results of this study showed decreased anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden after 8 sessions of MBI which is in agreement with these findings.

Considering the previous efforts where new telecommunication technologies were applied to support psychological interventions (Omidi & Mohamadkhani, 2008; Eichenberg & Ott, 2012), in this study, MBI was provided for caregivers of patients with MS remotely via an online application which could create the possibility of meditation at home to improve their anxiety, depression, and caregiving burden. Review of the literature can find studies which indicate that meditation improves the mental well-being of MS patients and their caregivers (Grossman et al., 2010); however, meditation cannot always be possible due to practical reasons (e.g. occupational activities) or physical constraints.

The caregivers of MS patients often suffer from mental illness. Few studies have examined the impact of psychological interventions on them. This study allows us to examine whether this treatment method can improve their quality of life. This intervention provides the ability to easily access to online resources which can be an evidence-based approach to improve the quality of life of MS patients and their caregivers. This protocol describes the development of a mindfulness-based intervention and its feasibility using a randomized controlled design.

The first limitation of this research was related to its virtual nature. Using online platforms in Iran is new and users (the caregivers of MS patients) may not be familiar with using it, and they have to be trained before the program starts. Another limitation was the lack of a follow-up period of more than one month because of time constraints. It is suggested that a longer follow-up period be used to evaluate the continuation of treatment outcomes in future studies. the villages and deprived areas should be equipped with high-speed Internet.

In this regard, medical teams, medical centers or universities should be ready to coordinate and provide systematic online services. Because of the importance of privacy and confidentiality, a special online security system should be designed for people using online communication methods with proper ethical protocols to protect them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This article was extracted from a PhD. thesis of Mahnaz Khazaeili in Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Qom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aghabagheri, H., Mohammadkhani, P., Omrani, S., & Farahmand, V. (2012). The efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy group on the increase of subjective well-being and hope in patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 23-31.

- Ahmadi-shooli, P., Feily, A. R., & Behzadipour, S. (2016). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the mental health of female patients suffering from Multiple Sclerosis. Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, 23(10), 989-1000.

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27-45.[DOI:10.1177/1073191105283504] [PMID]

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329-42. [PubMed] [DOI:10.1177/1073191107313003]